Abstract

Long QT Syndrome variant 3 (LQT-3) is a channelopathy in which mutations in SCN5A, the gene coding for the primary heart Na+ channel alpha subunit, disrupt inactivation to elevate the risk of mutation carriers for arrhythmias that are thought to be calcium (Ca2+)-dependent. Spontaneous arrhythmogenic diastolic activity has been reported in myocytes isolated from mice harboring the well-characterized ΔKPQ LQT-3 mutation but the link to altered Ca2+ cycling related to mutant Na+ channel activity has not previously been demonstrated. Here we have investigated the relationship between elevated sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ load and induction of spontaneous diastolic inward current (ITI) in myocytes expressing ΔKPQ Na+ channels, and tested the sensitivity of both to the antianginal compound ranolazine. We combined whole cell patch clamp measurements, imaging of intracellular Ca2+, and measurement of SR Ca2+ content using a caffeine dump methodology. We compared the Ca2+ content of ΔKPQ+/- myocytes displaying ITI to those without spontaneous diastolic activity and found that ITI induction correlates with higher sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+. Both spontaneous diastolic ITI and underlying Ca2+ waves are inhibited by ranolazine at concentrations that preferentially target INaL during prolonged depolarization. Furthermore, ranolazine ITI inhibition is accompanied by a small but significant decrease in SR Ca2+ content. Our results provide the first direct evidence that induction of diastolic transient inward current (ITI) in ΔKPQ+/- myocytes occurs under conditions of elevated SR Ca2+ load.

Keywords: Long QT syndrome, LQT-3, ΔKPQ+/-, arrhythmia, persistent late Na+ current, INaL, transient inward current, ITI, Ca2+ overload, Ca2+ waves, SR Ca2+ content, ranolazine

Introduction

Long QT syndrome variant 3 (LQT-3) is a rare, but lethal, inherited arrhythmia syndrome caused by mutations in SCN5A, the gene coding for the alpha subunit of the primary heart voltage gated Na+ channel [1, 2]. The first reported and best-characterized LQT-3 mutation causes the deletion of three amino acids (ΔKPQ) in the channel inactivation gate [3] resulting in a defect in channel inactivation and persistent late Na+ current (INaL) during maintained ventricular depolarization that underlies the electrocardiogram QT interval [4]. Initial analysis of the functional consequences of the ΔKPQ mutation [5, 6] focused on the link between the resulting action potential (AP) prolongation and the generation of “early afterdepolarizations” (EADs) which are driven by reactivation of L-type calcium channels and occur during the initial phases of ventricular repolarization [7]. More recently, attention has focused on the link between mutation enhanced Na+ entry during depolarization to transient inward current (ITI) recorded at diastolic potentials after repolarization is complete [8]. ITI drives arrhythmogenic “delayed after depolarizations” (DADs) which occur over the diastolic voltage range under conditions favoring sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium ([Ca2+]SR) overload [9-11]. Thus the link between the ΔKPQ mutation and ITI induction suggested the possibility that arrhythmia susceptibility in LQT-3 may be due to two distinct Ca2+ dependent mechanisms: one that may occur during repolarization (EAD) and one that may occur during diastole (DAD), but direct measurement of altered SR load in latter case previously has not been reported.

Here, in myocytes isolated from ΔKPQ+/- mice, we have investigated the relationship between ITI generation and [Ca2+]SR and studied the effects of the antianginal agent ranolazine on both parameters. We chose to investigate ranolazine because it has previously been shown not only to preferentially inhibit INaL [12] but also because it is associated with improved diastolic relaxation in LQT-3 patients [13]. We find, as in the case of other perturbations that promote spontaneous diastolic arrhythmogenic activity, ITI is associated with constitutively elevated [Ca2+]SR. Ranolazine inhibits both diastolic Ca2+ transients and ITI over the same concentration range as ranolazine inhibition of INaL. Furthermore, Ranolazine inhibition of ITI in ΔKPQ+/-myocytes is accompanied by a reduction in [Ca2+]SR. Our results thus provide the first direct link between altered Na+ channel activity in ΔKPQ+/- myocytes during membrane depolarization to arrhythmogenic activity driven by elevated [Ca2+]SR over diastolic voltages: evidence for a second Ca2+ dependent arrhythmic pathway in LQT-3.

Materials and Methods

ΔKPQ Mice and Isolation of Cardiac Ventricular Myocytes

Mice heterozygous for a knock-in KPQ deletion in SCN5A [5] were genotyped by PCR analysis to confirm the expression of the SCN5A ΔKPQ Na+ channels. Ventricular myocytes from adult mice (3 to 8 months of age) were dissociated as previously described [8, 14] and used within 6 hours. The institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Columbia University approved the protocols for all animal studies.

Solutions

Membrane currents were measured using whole-cell procedures with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Capacity current and series resistance compensation were carried out according to the amplifier manufacture. Micropipette electrodes resistance was 1.5 to 2.5 MΩ. Membrane currents were low pass filtered at 2 kHz and sampled at 2 kHz. All measurements were obtained at room temperature (22°C). Na+ current was recorded using the following external solution (in mM): 130 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 5 CsCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.5 BaCl2 and 5 glucose (pH 7.4 with CsOH). Pipette filling solution was composed of (in mM): 50 aspartic acid, 60 CsCl, 5 Na2ATP, 0.05 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 0.0215 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.2, with CsOH). For imaging experiments, fluo 4 K+ salt (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) 0.05 mM replaced EGTA. Free [Ca2+] in both pipette filling solutions was buffered to 100 nM. Tetrodotoxin (TTX; Ascent Scientific, Princeton, NJ) and Ranolazine (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) solutions were prepared from 5 mM and 10 mM stock solutions respectively in H2O. Because of changes of efficacy, Ranolazine stock was prepared fresh every day.

Protocols

High concentrations of TTX (50 μM) were used to block peak Na+ channel current (INaP) and late Na+ current (INaL) and reveal background currents that were digitally subtracted offline. Both INaP and INaL were defined by the mean of 5 sweeps recorded at 1 Hz and measured as TTX-sensitive currents in response to depolarizing pulses from -75 mV to -10 mV. INaL was measured 200 ms after the voltage step. Ranolazine block of INa was achieved within 2 to 3 minutes. Data were normalized to cell capacitance and to control currents for establishing the concentration-response relationships. A 1 Hz conditioning train of voltage pulses was used to trigger ITI in ΔKPQ+/- myocytes [8]. Briefly, it consisted of 10 depolarizing steps from a holding potential of -75 mV (-10 mV, 400 ms) followed by a 1 s pause and a last depolarization (Figure 1A). ITI was recorded at -75 mV for a period of 10 s following the last depolarizing step of the conditioning train of voltage pulses.

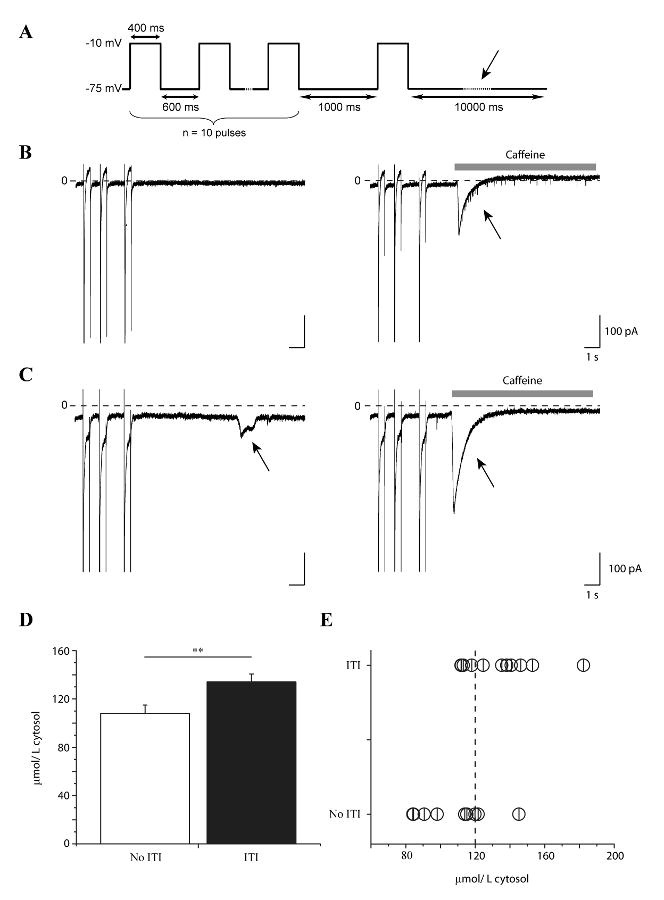

Figure 1. ITI induction in ΔKPQ+/- myocytes correlates with elevated [Ca2+]SR.

A. Schematic of conditioning voltage pulse train used to induce ITI (Methods). ITI and [Ca2+]SR were measured at the holding potential (-75 mV) as indicated by the arrow in the diagram. B,C. Shown are high gain current recordings during the 3 last pulses of the conditioning train followed by 10 s at the holding potential in a cell which lacked ITI (B, left) and a cell in which ITI was induced (C, left). In the same cells, [Ca2+]SR was estimated by applying caffeine (10 mM, grey bars) and integrating the caffeine-induced INCX (B,C right, arrows) triggered after the conditioning train of voltage pulses. D. Bar graph summarizes mean [Ca2+]SR in cells without (open, n = 9) and with (closed, n = 11) ITI (**: p < 0.05) (D). [Ca2+]SR of single experiments is plotted to reveal threshold for ITI (E). Vertical dashed line: mean [Ca2+]SR estimated by others in cells that generate ITI [18].

Data Analysis

pClamp 8.0 and 10.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), Excel (Microsoft), and Origin 7.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) were used for data acquisition and analysis. Curve fitting was carried out using programs provided in the OriginLab software package. Ranolazine IC50 was estimated by fitting concentration-response data (ITI, INaL and INaP) to a logistic function (Origin). ITI density was estimated by defining a baseline diastolic current and measuring the area under the curve for the difference between this baseline and any diastolic events. Total charges for each recording was calculated as the sum of all diastolic events occurring within 10 seconds after the conditioning train protocol and is expressed in pC/cell.

Normalization of [Ca2+]SR

[Ca2+]SR was estimated by integrating caffeine-induced NCX transient inward current (INCX). The resulting values, in pC/pF were normalized to μmol/L cytosol using the constant 121.32 derived from measurements made in 3-8 month old rats [15, 16]. Because balance between different Ca2+ transports in rat and mice is similar, we can assume that our normalization is valid [17]

Ca2+ imaging

Fluo 4 K+ salt was excited at 488 nm and fluorescent emission collected at >505 nm using laser-scanning confocal microscopy (Zeiss Live 5, Carl Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany). The linescan mode was used to record fluorescent temporal profiles. Recordings lasted 30 s and were acquired at a scan rate of 500 Hz. Resting levels of fluorescence (F0), acquired immediately before the depolarizing conditioning train of voltage pulses, were used to normalize the images. Image normalization was done using a custom made macro in imageJ (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997-2008). For comparison, diastolic Ca2+ waves and systolic Ca2+ transients profiles were integrated and normalized to control conditions.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Two-tailed Student's t test was used to compare two means; a value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The experiments in this study were designed to investigate a possible role of intracellular Ca2+ in ITI generation in myocytes expressing Na+ channels harboring the ΔKPQ mutation and thus mutation-enhanced INaL. Because of the well documented and strong correlation found between [Ca2+]SR and spontaneous Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in other models [18], we designed experiments to investigate the relationship between ITI induction and [Ca2+]SR. We used a modified previously-described conditioning train protocol [8] to induce ITI (see Methods) and application of caffeine to induce release of and hence measure [Ca2+]SR [19, 20]. The latter technique, described in Methods, is referred to as a caffeine dump protocol. First, transient inward current (ITI) was measured at -75 mV after applying conditioning trains of voltage pulses (-10 mV, 400 ms, 1 Hz). Using this protocol, ITI was induced in 76 % of ΔKPQ+/- myocytes (n = 57 vs. n = 18 without ITI), a number similar to that which was previously reported [8]. We separated the data into two groups: data from ΔKPQ+/- myocytes displaying ITI (n = 11) and from those myocytes in which ITI was not induced (n = 9) (Figure 1B and C, left). Then, in the same cells we measured [Ca2+]SR. The protocol was repeated, but within 1-2 s after the final conditioning pulse, the cell was exposed to 10 mM caffeine to trigger Ca2+ release from the SR [19, 20]. SR Ca2+ release is monitored via a transient inward Na+/Ca2+ exchanger current (INCX) (Figure 1B and C, right). Data for similar experiments carried out in myocytes isolated from WT littermate mice are summarized in supplemental data (Figure 1).

[Ca2+]SR estimated by species specific normalization of integrated INCX to cell volume (Methods), revealed that induction of ITI in these myocytes correlates with a significantly higher [Ca2+]SR compared to quiescent cells (quiescent: 108.2 ± 7 μmol/L of cytosol, n = 9, displaying ITI: 134.1 ± 7 μmol/L of cytosol, n = 11, p < 0.05) (Figure 1D). Because ITI probability depends not only on luminal SR Ca2+ [21] but also on RyR2 gating [22], we estimated the [Ca2+]SR threshold for spontaneous ITI by plotting together [Ca2+]SR values from single experiments (Figure 1E) [23]. In previous investigations, Diaz et al have reported a mean value for [Ca2+]SR of 120 μmol/L cytosol for cells exhibiting spontaneous diastolic activity [18]. ITI induction in the present experiments in ΔKPQ myocytes occurs in the same range of [Ca2+]SR as indicated by the dashed vertical line in Figure 1E). This is also the case for ITI induction in myocytes from WT littermates (Supplemental data). Thus, similar to other perturbations, induction of ITI in myocytes expressing ΔKPQ Na+ channels occurs under conditions in which Ca2+ store overload promotes spontaneous Ca2+release [18, 21].

We next tested the effects of ranolazine on ITI and spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ transients in the same cells, because ranolazine previously has been shown to have high selectivity for late (INaL) vs. peak (INaP) Na+ current (IC50 = 15 vs 135 μM) [12], and has been reported to improve diastolic function in LQT-3 patients [13]. Figure 2 illustrates these experiments. Shown in the figure are currents (upper rows), line scans (middle rows), and averaged Ca2+ signals (lower rows) recorded during the last pulse of the conditioning train along with prolonged recordings at -75 mV following the conditioning train. The protocol induced ITI (Figure 2A, arrow, upper panel), that was associated with spontaneous elevation of cytosolic [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) (i.e.: Ca2+ wave) (Figure 2A, middle panel, arrows). Exposure of the cell to ranolazine (20 μM) inhibited ITI (Figure 2B, upper panel) and the accompanying diastolic Ca2+ wave (Figure 2B, lower panel). Examination of the currents recorded during the last conditioning pulse reveals ranolazine block of INaL in the experiments.

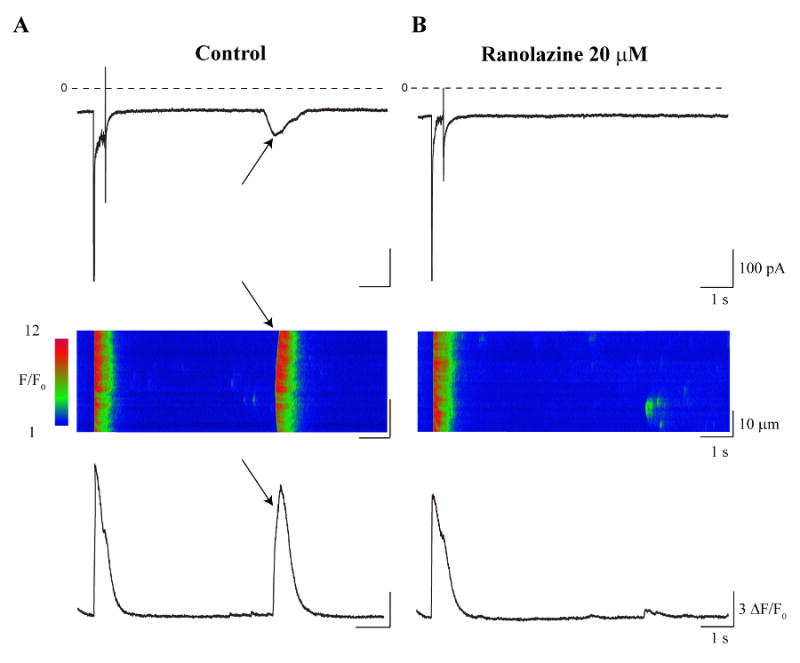

Figure 2. Ranolazine (20 μM) inhibits ITI and related diastolic Ca2+ wave.

Representative currents (upper rows), line scans (middle rows), and averaged Ca2+ signals (lower rows) recorded during the last pulse of the conditioning train protocol (Methods) and followed by 10 s at the return holding potential (-75 mV). A. Control conditions reveal ITI induction (A, upper panel, arrow) that was associated with a Ca2+ wave (A, middle and lower panels, arrows). B. Exposure to ranolazine (20 μM) inhibited ITI (B, upper panel) and the accompanying Ca2+ wave (B, middle and lower panels).

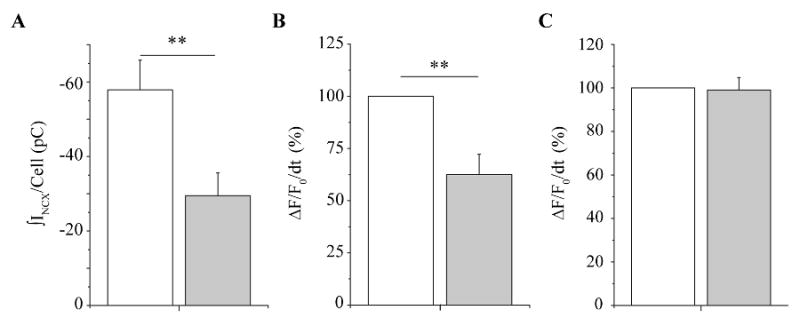

Summary data for this series of experiments are presented in Figure 3. In ΔKPQ myocytes, ranolazine (20 μM) significantly decreased mean ITI density per cell by 50 % ± 8 %, from -57.9 ± 8 pC/cell in control condition to -29.5 ± 6 pC/cell after ranolazine (n = 17, p < 0.05) (Figure 3A) and the underlying fluorescent Ca2+ wave density (reduced by 39 % ± 10 % (n = 17, p < 0.05) (Figure 3B). Data were normalized to counterbalance cell-to-cell variability associated with Ca2+ dye loading. In the same cells ranolazine had no significant effect on systolic Ca2+ transients, measured as the integral of the fluorescent signal of the last Ca2+ transient during the conditioning train in the absence and presence of ranolazine (Figure 3C; CTL: 100 %, RAN: 99.6 ± 6 %, n = 17, p > 0.05). In cells isolated from WT littermates ranolazine had no significant effect either on systolic Ca2+ or on ITI and underlying diastolic Ca2+ transients (Supplemental data, figures 2 and 3).

Figure 3. Summary data: ranolazine inhibits ITI, diastolic Ca2+ wave, but not systolic Ca2+ transient.

Both systolic and diastolic Ca2+ events were determined by integrating normalized fluo-4 transient signals as described in Methods. The bar graphs summarize (A) mean ITI density per cell (n = 18); (B) mean Ca2+ wave density (n = 18); and (C) mean systolic Ca2+ density as measured during the final pulse of the conditioning train (n = 18) in control (open) and after exposure to ranolazine (20 μM) (closed). **: p < 0.05, paired.

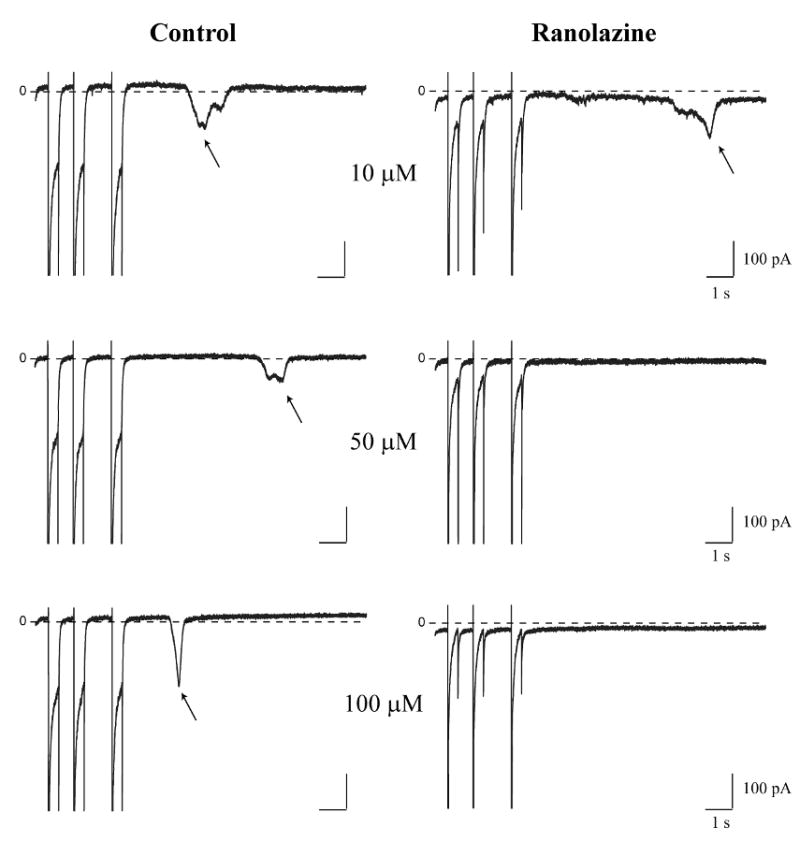

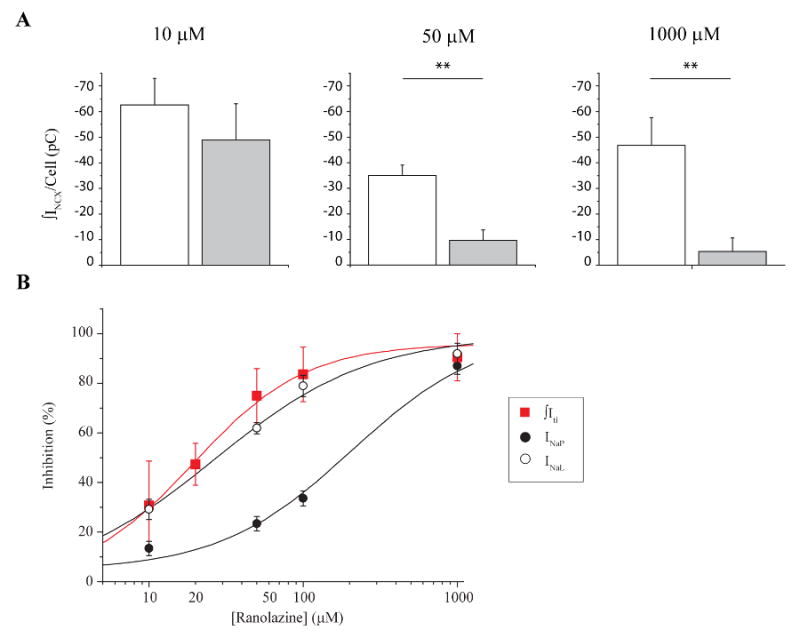

These data suggest that induction of ITI is correlated with spontaneous Ca2+ waves that occur during diastole and that ranolazine significantly decreases both spontaneous diastolic events. We observed effects of ranolazine on both to ITI current density measured and the frequency of ITI occurrence. Figures 4 and 5 summarize these effects of ranolazine on ITI over a broad concentration range. Figure 4 shows examples of ITI recorded after conditioning trains in the absence and presence of 10 μM, 50 μM, and 1000 μM ranolazine. Figure 5 reports the group data, and focuses on the effects of ranolazine on total ITI density. Diastolic ITI density was summed for each cell, and compared in both conditions: control and ranolazine. At a concentration of 10 μM ranolazine failed to prevent the generation of spontaneous diastolic ITI (CTL: -62.6 ±10 pC/cell, RAN: -48.9 ± 14 pC/cell, n = 5, p > 0.05) (Figure 5A, left). Increasing ranolazine concentration to 50 μM significantly decreased ITI from -35 ± 4 pC/cell in control conditions to -9.6 ± 4 pC/cell (n = 8, p < 0.05) (Figure 5A, center). The maximal inhibition we observed was reached with 1000 μM (CTL: -46.8 ± 11 pC/cell, RAN: -5.3 ± 5.3 pC/cell, n = 4, p < 0.05) (Figure 5A, right). Data were fit with a logistic function shown as the smooth curve in the figure (see Methods), resulting in a predicted IC50 of 19.5 ± 3 μM. Ranolazine also affects the frequency of ITI occurrence (data not shown). There was no significant effect of 10 μM ranolazine mean ITI frequency (0.88 ± 0.23 ITI per cell control vs. 1.13 +/- 0.35 ITI per cell in 10 μM ranolazine, n = 8) but 50 μM, 100 μM and 1000 μM significantly did so (1.35 ± 0.21 ITI per cell control vs. 0.6 ± 0.27 ITI per cell in 50 μM ranolazine, n = 10, p < 0.05; 0.89 ± 0.26 ITI per cell control vs. 0.13 ± 0.12 ITI per cell in 100 μM ranolazine, n = 9, p < 0.05 and 1.25 ± 0.25 ITI per cell control vs. 0.13 ± 0.11 ITI per cell in 1000 μM ranolazine, n = 4, p < 0.05).

Figure 4. Ranolazine inhibits ITI in a concentration-dependent manner.

Representative high gain recordings from three different myocytes show currents in response to the 3 last pulses of conditioning trains followed by 10 s return to the holding potential before (left) and after (right) exposure to the indicated ranolazine concentrations: 10 μM (upper row), 50 μM (middle row) and 100 μM (lower row). Arrows indicate ITI in relevant panels. Zero current is indicated (0) in each panel.

Figure 5. Ranolazine inhibition of ITI and INaL share similar concentration-dependence.

A. Bar graphs show mean ITI density per cell in control conditions (open) and after exposure to 10 μM (left; n = 5), 50 μM (middle; n = 8) and 1000 μM (right; n = 4) ranolazine (closed). **: p<0.05, paired. B. Summary plot of the concentration-dependence ranolazine inhibition of INa peak (●), INaL (○) and ITIs ( ). Smooth curves are best fits of concentration-response relationships to INaL, INaP and ITI data (see Methods).

). Smooth curves are best fits of concentration-response relationships to INaL, INaP and ITI data (see Methods).

For comparison, we also measured the effects of ranolazine on INaP and INaL in the same cells (Figure 5B). In agreement with previously published results [12], ranolazine preferentially inhibited INaL when compared to its effects on INaP. INaP was inhibited by 13.4 % ± 3 % (n = 8), 23.4 % ± 3 % (n = 12), 33.6 % ± 3 % (n = 9) and 87 % ± 3 % (n = 4) after perfusion with 10 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, and 1000 μM ranolazine respectively (Figure 5B, closed black circles). INaL was inhibited by 29.8 % ± 4 % (n = 8, ranolazine 10 μM); 62 % ± 2 % (n = 12, ranolazine 50 μM); 79 % ± 4 % (n = 9, ranolazine 100 μM); and by 92 % ± 4 % (n = 4, ranolazine 1000 μM) (Figure 5B, open black circles). INaL (open) and INaP (filled) data were fit with logistic functions (Methods). Resulting best fits are plotted as smooth curves (Figure 5B). Estimated IC50s for both sets of data, INaL and INaP (26.8 μM and 206.1 μM respectively) are in the range of previously published results [12]. The results reveal strikingly similar concentration-dependent ranolazine inhibition of INaL and ITI (19.5 μM), and clearly a distinct pharmacological profile from ranolazine inhibition of INaP.

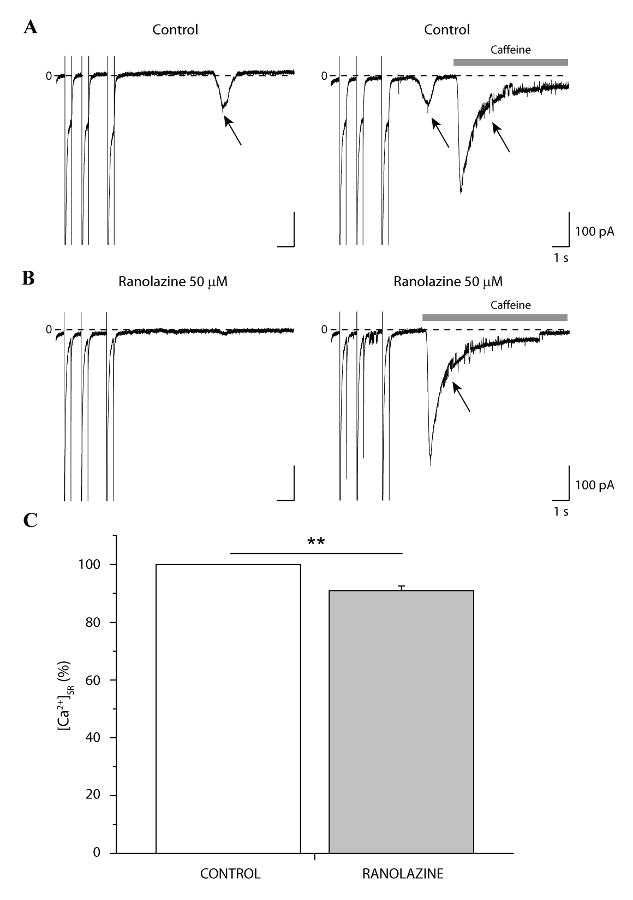

Because we find that ranolazine inhibits both ITI and underlying spontaneous diastolic SR Ca2+ events, we next investigated the impact of ranolazine on [Ca2+]SR. We simultaneously measured the impact of ranolazine (50 μM) on ITI induction and [Ca2+]SR in the same cells as illustrated and summarized in Figure 6. A conditioning train protocol (Methods) was imposed to induce ITI, and after ITI detection, the protocol was repeated and followed by caffeine 10 mM application (within 1-2 s after the last conditioning pulse) to estimate [Ca2+]SR. In cases when ITI appeared before caffeine (Figure 6A, right), ITI density was summed to the caffeine-induced INCX to correct for [Ca2+]SR loss. This procedure was carried out in the absence (Figure 6A) and then again in the presence of ranolazine (50 μM, Figure 6B). [Ca2+]SR was significantly decreased by ranolazine (by 9.1 % ± 1.6 %, n = 5, p < 0.05) (Figure 6C). That this small, but significant, decrease in [Ca2+]SR correlates with decreased ITI incidence, is consistent with the known non-linearity observed between [Na+]i and [Ca2+]SR and Ca2+ waves [18, 24, 25].

Figure 6. Ranolazine decreases [Ca2+]SR.

Representative high gain recordings during the 3 last pulses of the conditioning train and 10 s at the holding potential (-75mV) after the train in the absence (A) and presence of 50 μM ranolazine (B). Induction (A, left, arrow) and ranolazine-dependent inhibition of ITI (B, left) was verified before estimating [Ca2+]SR in both conditions using caffeine-induced INCX (A and B, right, arrows). Zero current is indicated (0) in each panel. C. Bar graph summarizes normalized mean [Ca2+]SR before and after exposure to ranolazine, n = 5, p < 0.05, paired (C).

Discussion

The results presented in this study provide the first direct evidence that an inherited LQT-3 mutation (ΔKPQ) that disrupts Na+ channel inactivation during prolonged depolarization is associated with elevated [Ca2+]SR load and consequential spontaneous electrical activity (ITI) that occur over a diastolic potential range, after the cell has repolarized. This activity may be particularly critical to the generation of pause-dependent arrhythmias in LQT-3 patients which have been reported in the clinical literature [26].

[Ca2+]SR triggers ITI in ΔKPQ+/-

Our results clearly show that ΔKPQ+/- myocytes with higher [Ca2+]SR are more prone to spontaneous diastolic activity than those with lower [Ca2+]SR, and our results are consistent with a causal role of mutation-enhanced late current (INaL) in ITI generation. We previously reported a higher incidence of ITI induction in myocytes from ΔKPQ mice compared with their WT littermates [8]. Now, our pharmacological results show that ranolazine inhibition of dysfunctional late Na+ channel current (INaL) and ITI in ΔKPQ myocytes share a common concentration dependence and is accompanied by reduction in [Ca2+]SR load. Interestingly, ITI, induced in myocytes from WT littermates, which lack mutation-enhanced INaL, is not inhibited by ranolazine, strengthening the link between ITI, spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ transients and INaL. The efficacy of the drug in suppressing spontaneous diastolic activity is likely to be due in large part to its effects both on mutation-enhanced INaL and on [Ca2+]SR load as supported by the nonlinearity between [Na+]i and [Ca2+]SR [18, 24, 25].

It is likely that ITI sensitivity of ΔKPQ myocytes is linked to changes in intracellular sodium concentration ([Na+]i) that may occur as a result of mutation-increased Na+ entry. Using Anemonia sulcata (ATX II) toxin-induced changes in Na+ entry as a pharmacological model of LQT-3, others have reported both induction of spontaneous diastolic activity and its inhibition by ranolazine [27-29] but in these models ATX II-induced Na+ entry is nearly 10 fold greater than that caused by the naturally occurring ΔKPQ mutation [30]. Thus the impact of mutation-enhanced late current on [Na]i in the present experiments is expected to be subtle. But even very small changes are expected to impact [Ca2+]i dynamics. Eisner, et al. showed that [Ca2+]i varies as a power function of [Na+]i, as assessed by tonic and twitch tension [24, 25]. Consequently even a slight increase in [Na+]i can cause a steep increase in [Ca2+]i. This would predict a small net increase in Ca2+ influx per depolarization that is augmented by mutation-altered INaL, and hence a net increased [Ca2+]SR as determined by the balance between different cellular Ca2+ transport rates [31]. Correlation between elevated [Ca2+]SR and spontaneous SR Ca2+ release has been known for many years. Diaz et al. showed that the relation between luminal SR Ca2+ content and Ca2+ stores instability is a very steep function [18]. Store instability results mostly from the sensitization of the RyR2s by luminal SR Ca2+ [21, 32, 33]. Our results indicate an approximate threshold for spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ release in ΔKPQ+/- myocytes that is the range reported by others for spontaneous diastolic activity generated by distinctly different perturbations (Figure 1, dashed vertical line) [18]. Taken together our data suggest that SR in ΔKPQ+/- myocytes have normal Ca2+ release properties, as determined by the RyR2 ability to open, but higher content than normal and that mutation-enhanced Na+ entry contributes to elevated [Ca2+]SR.

Mechanism of ITI inhibition by ranolazine

It is clear from the experiments reported in this study that ranolazine effectively and preferentially inhibits diastolic Ca2+ spontaneously released from the SR at concentrations that have no significant effect on SR Ca2+ released in response to depolarization (Figure 3). The effectiveness of ranolazine at inhibiting diastolic events is particularly interesting in view of the fact that the drug has been reported to improve diastolic relaxation in LQT-3 patients [13]. As noted above the effects of ranolazine on diastolic events share the same concentration-dependence as ranolazine inhibition of INaL, suggesting that pharmacologic inhibition of INaL should be accompanied by concomitant reduction in SR Ca2+ content. We in fact found a significant reduction [Ca2+]SR, but the magnitude of this effect was small, approximately a 9 % reduction in [Ca2+]SR (Figure 6). Nevertheless, Diaz et al reported that the relation between luminal SR Ca2+ content and Ca2+ stores instability is a very steep function, thus though small, the inhibitory effect of ranolazine on SR load is likely to be a major factor in the effects of the drug on diastolic Ca2+ transients and ITI.

Ranolazine has other effects which may also contribute to its inhibition of ITI. For example ranolazine has also been studied in a pharmacological LQT3 model [34]. Sossala et al. reported effects of ranolazine on [Ca2+]SR in isolated rabbit myocytes treated with ATX-II to increase systolic Na+ entry via severe modulation of Na+ channel inactivation. In this study ranolazine significantly inhibited ATX II-induced INaL and reduced frequency-dependent increases in diastolic tension without affecting SR Ca2+ load. Though similar to our subtle effects of ranolazine on SR load, Sossala et al suggested that a ranolazine-induced increase of NCX transport might also contribute to this action. Ranolazine is also known to affect other ion channels in the heart, including Cav1.2 channels [35], and, in addition has been shown to have important metabolic effects in heart [36, 37], although these effects are expected to be minimal at 20 μM ranolazine.

In summary we find that expression of Na+ channels harboring the ΔKPQ mutation in myocytes is associated with elevated [Ca2+]SR load, spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ release, and consequential spontaneous diastolic electrical activity (ITI). Ranolazine effectively inhibits mutation-induced INaL and ITI, and reduces [Ca2+]SR in ΔKPQ myocytes. These properties make ranolazine a strong candidate for therapeutic management of LQT-3 and other disorders such as heart failure in which enhanced late Na+ channel activity and spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ release may occur [29, 38-41].

Limitations of the study

Here we report that ITI is associated with constitutively elevated [Ca2+]SR in ΔKPQ+/- myocytes and that Ranolazine inhibits both diastolic Ca2+ transients and ITI over the same concentration range as ranolazine inhibition of INaL. This implies a critical role of mutation enhanced INaL in the generation of ITI. and spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ release as suggested in our previous report [8]. But, because Ca2+ waves are generally caused by elevated [Ca2+]SR, any mechanism affecting SR load will similarly affect the ITI probability and thus affect the results. The use of genetically engineered mice provide insight into the pathophysiology of myocytes isolated from them, but, particularly in experiments such as those described in this paper in which altered intracellular Ca2+ dynamics are studied it must be remembered that, while contraction in mice and rats primarily relies on [Ca2+]SR, in human as well as rabbits and ferrets, contraction relies more on Ca2+ entry through CaV1.2 calcium channels. Consequently the exact role of INaL on [Ca2+]SR and resulting ITI generation may vary with these species-dependent differences [15, 31].

Supplementary Material

A,B. Shown are high gain current recordings during the 3 last pulses of the conditioning train followed by 10 s at the holding potential (Methods) in a ΔKPQ-/- cell (A). In the same cell, [Ca2+]SR was estimated by applying caffeine (10 mM, grey bars) and integrating the caffeine-induced INCX (B, arrow) triggered after the conditioning train of voltage pulses. C. Bar graph summarizes mean [Ca2+]SR in cells without (open, -94.2 ± 7.6 μmol/L cytosol, n = 3) and with ITI (closed, -112.6 ± 5.5 μmol/L cytosol, n = 7, p > 0.05) (D). [Ca2+]SR of single experiments is plotted to reveal threshold for ITI (D). Mean [Ca2+]SR of spontaneously active cells as reported by the literature (120 μmol/L cytosol) is represented by the vertical dotted line for comparison with data from ΔKPQ+/- myocytes.

Representative currents (upper rows), line scans (middle rows), and averaged Ca2+ signals (lower rows) recorded during the last three pulses of the conditioning train protocol (Methods) and followed by 10 s at the return holding potential (-75 mV). A. Control conditions reveal ITI induction (A, upper panel, arrow) that was associated with a Ca2+ wave (A, middle and lower panels, arrows). B. Exposure to ranolazine (20 μM) failed to inhibit ITI (B, upper panel) and the accompanying Ca2+ wave (B, middle and lower panels).

Both systolic and diastolic Ca2+ events were determined by integrating normalized fluo-4 transient signals as described in Methods. A. The bar graph summarizes the mean ITI density per cell in control (open, -19.8 ± 5.3 pC/cell) and after exposure to ranolazine (20 μM) (closed, -15.3 ± 11.5 pC/cell, n = 3, p > 0.05, paired). ITI was induced in 3 out of 8 cells. B. Mean normalized Ca2+ wave density in absence and presence of the drug (RAN: 89 % ± 15.8 %, n = 3, p > 0.05, paired). C. Mean systolic Ca2+ density as measured during the final pulse of the conditioning train (RAN: 141.7 % ± 28.1 %, n = 8, p > 0.05, paired).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from NHLBI (P01 HL076849-07, to R.S.K., W.J.L., A.R.M.), the Swiss National Science Foundation (fellowship PBBEA-111201 to N.L.), Leducq foundation (ENAFRA to W.J.L.) and AHA (0825469E to B.M.H.).

Footnote

- LQTS

long QT syndrome

- LQT-3

The long QT syndrome variant 3

- ITI

transient inward current

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- [Ca2+]SR

SR Ca2+ content

- [Ca2+]i

cytosolic [Ca2+]

- INaL

persistent Na+current

- INaP

peak Na+ current

- EADs / DADs

early and delayed afterdepolarizations

- ΔKPQ

KPQ deletion

- TTX

Tetrodotoxin

- RyR2

ryanodine receptor

- INCX

Na+/Ca2+exchanger current

- ATX-II

sea anemone toxin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sauer AJ, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Peterson DR, Zareba W, Robinson JL, et al. Long QT syndrome in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 Jan 23;49(3):329–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zareba W, Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, Vincent GM, Robinson JL, Priori SG, et al. Influence of genotype on the clinical course of the long-QT syndrome. International Long-QT Syndrome Registry Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1998 Oct 1;339(14):960–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Shen J, Splawski I, Atkinson D, Li Z, Robinson JL, et al. SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995 Mar 10;80(5):805–11. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett PB, Yazawa K, Makita N, George AL., Jr Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995 Aug 24;376(6542):683–5. doi: 10.1038/376683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuyens D, Stengl M, Dugarmaa S, Rossenbacker T, Compernolle V, Rudy Y, et al. Abrupt rate accelerations or premature beats cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mice with long-QT3 syndrome. Nat Med. 2001 Sep;7(9):1021–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clancy CE, Rudy Y. Linking a genetic defect to its cellular phenotype in a cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1999 Aug 5;400(6744):566–9. doi: 10.1038/23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.January CT, Riddle JM. Early afterdepolarizations: mechanism of induction and block. A role for L-type Ca2+ current. Circ Res. 1989 May;64(5):977–90. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredj S, Lindegger N, Sampson KJ, Carmeliet P, Kass RS. Altered Na+ channels promote pause-induced spontaneous diastolic activity in long QT syndrome type 3 myocytes. Circ Res. 2006 Nov 24;99(11):1225–32. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251305.25604.b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrier GR, Moe GK. Effect of calcium on acetylstrophanthidin-induced transient depolarizations in canine Purkinje tissue. Circ Res. 1973 Nov;33(5):508–15. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kass RS, Lederer WJ, Tsien RW, Weingart R. Role of calcium ions in transient inward currents and aftercontractions induced by strophanthidin in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1978 Aug;281:187–208. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993 Oct 29;262(5134):740–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredj S, Sampson KJ, Liu H, Kass RS. Molecular basis of ranolazine block of LQT-3 mutant sodium channels: evidence for site of action. Br J Pharmacol. 2006 May;148(1):16–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Schwarz KQ, Rosero S, McNitt S, Robinson JL. Ranolazine Shortens Repolarization in Patients with Sustained Inward Sodium Current Due to Type-3 Long-QT Syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008 Jul 25; doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitra R, Morad M. A uniform enzymatic method for dissociation of myocytes from hearts and stomachs of vertebrates. Am J Physiol. 1985 Nov;249(5 Pt 2):H1056–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.5.H1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassani JW, Bassani RA, Bers DM. Relaxation in rabbit and rat cardiac cells: species-dependent differences in cellular mechanisms. J Physiol. 1994 Apr 15;476(2):279–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satoh H, Delbridge LM, Blatter LA, Bers DM. Surface:volume relationship in cardiac myocytes studied with confocal microscopy and membrane capacitance measurements: species-dependence and developmental effects. Biophys J. 1996 Mar;70(3):1494–504. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79711-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Chu G, Kranias EG, Bers DM. Cardiac myocyte calcium transport in phospholamban knockout mouse: relaxation and endogenous CaMKII effects. Am J Physiol. 1998 Apr;274(4 Pt 2):H1335–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.4.H1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz ME, Trafford AW, O'Neill SC, Eisner DA. Measurement of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content and sarcolemmal Ca2+ fluxes in isolated rat ventricular myocytes during spontaneous Ca2+ release. J Physiol. 1997 May 15;501(Pt 1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.003bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callewaert G, Cleemann L, Morad M. Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release activates Ca2+ extrusion via Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1989 Jul;257(1 Pt 1):C147–52. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.1.C147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varro A, Hester S, Papp JG. Caffeine-induced decreases in the inward rectifier potassium and the inward calcium currents in rat ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1993 Aug;109(4):895–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyorke I, Gyorke S. Regulation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor channel by luminal Ca2+ involves luminal Ca2+ sensing sites. Biophys J. 1998 Dec;75(6):2801–10. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77723-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehnart SE, Mongillo M, Bellinger A, Lindegger N, Chen BX, Hsueh W, et al. Leaky Ca2+ release channel/ryanodine receptor 2 causes seizures and sudden cardiac death in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008 Jun;118(6):2230–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI35346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001 Jun 8;88(11):1159–67. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisner DA, Lederer WJ, Sheu SS. The role of intracellular sodium activity in the antiarrhythmic action of local anaesthetics in sheep Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1983 Jul;340:239–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisner DA, Lederer WJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. The quantitative relationship between twitch tension and intracellular sodium activity in sheep cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1984 Oct;355:251–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan HL, Bardai A, Shimizu W, Moss AJ, Schulze-Bahr E, Noda T, et al. Genotype-specific onset of arrhythmias in congenital long-QT syndrome: possible therapy implications. Circulation. 2006 Nov 14;114(20):2096–103. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, Belardinelli L. An increase in late sodium current potentiates the proarrhythmic activities of low-risk QT-prolonging drugs in female rabbit hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006 Feb;316(2):718–26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser H, Belardinelli L, Wang L, Light PE, McVeigh JJ, Clanachan AS. Ranolazine decreases diastolic calcium accumulation caused by ATX-II or ischemia in rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006 Dec;41(6):1031–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song Y, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. An increase of late sodium current induces delayed afterdepolarizations and sustained triggered activity in atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008 May;294(5):H2031–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01357.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bankston JR, Yue M, Chung W, Spyres M, Pass RH, Silver E, et al. A Novel and Lethal De Novo LQT-3 Mutation in a Newborn with Distinct Molecular Pharmacology and Therapeutic Response. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(12):e1258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002 Jan 10;415(6868):198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kass RS, Lindegger N, Hagen B, Lederer WJ. Another calcium paradox in heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008 Jul;45(1):28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindegger N, Niggli E. Paradoxical SR Ca2+ release in guinea-pig cardiac myocytes after beta-adrenergic stimulation revealed by two-photon photolysis of caged Ca2+ J Physiol. 2005 Jun 15;565(Pt 3):801–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sossalla S, Wagner S, Rasenack EC, Ruff H, Weber SL, Schöndube FA, et al. Ranolazine improves diastolic dysfunction in isolated myocardium from failing human hearts -Role of late sodium current and intracellular ion accumulation. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Wu L, Fraser H, Zygmunt AC, Burashnikov A, et al. Electrophysiologic properties and antiarrhythmic actions of a novel antianginal agent. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2004 Sep;9 Suppl 1:S65–83. doi: 10.1177/107424840400900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson JR, Nawarskas JJ. Ranolazine. A metabolic modulator for the treatment of chronic stable angina. Cardiol Rev. 2005 Jul-Aug;13(4):202–10. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000161979.62749.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morin D, Hauet T, Spedding M, Tillement J. Mitochondria as target for antiischemic drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001 Jul 2;49(12):151–74. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Undrovinas AI, Belardinelli L, Undrovinas NA, Sabbah HN. Ranolazine improves abnormal repolarization and contraction in left ventricular myocytes of dogs with heart failure by inhibiting late sodium current. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006 May;17 Suppl 1:S169–S77. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eckhardt LL, Teelin TC, January CT. Is ranolazine an antiarrhythmic drug? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008 May;294(5):H1989–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00285.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pham DQ, Mehta M. Ranolazine: a novel agent that improves dysfunctional sodium channels. Int J Clin Pract. 2007 May;61(5):864–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Inhibition of late sodium current to reduce electrical and mechanical dysfunction of ischaemic myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2008 Mar;153(6):1128–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A,B. Shown are high gain current recordings during the 3 last pulses of the conditioning train followed by 10 s at the holding potential (Methods) in a ΔKPQ-/- cell (A). In the same cell, [Ca2+]SR was estimated by applying caffeine (10 mM, grey bars) and integrating the caffeine-induced INCX (B, arrow) triggered after the conditioning train of voltage pulses. C. Bar graph summarizes mean [Ca2+]SR in cells without (open, -94.2 ± 7.6 μmol/L cytosol, n = 3) and with ITI (closed, -112.6 ± 5.5 μmol/L cytosol, n = 7, p > 0.05) (D). [Ca2+]SR of single experiments is plotted to reveal threshold for ITI (D). Mean [Ca2+]SR of spontaneously active cells as reported by the literature (120 μmol/L cytosol) is represented by the vertical dotted line for comparison with data from ΔKPQ+/- myocytes.

Representative currents (upper rows), line scans (middle rows), and averaged Ca2+ signals (lower rows) recorded during the last three pulses of the conditioning train protocol (Methods) and followed by 10 s at the return holding potential (-75 mV). A. Control conditions reveal ITI induction (A, upper panel, arrow) that was associated with a Ca2+ wave (A, middle and lower panels, arrows). B. Exposure to ranolazine (20 μM) failed to inhibit ITI (B, upper panel) and the accompanying Ca2+ wave (B, middle and lower panels).

Both systolic and diastolic Ca2+ events were determined by integrating normalized fluo-4 transient signals as described in Methods. A. The bar graph summarizes the mean ITI density per cell in control (open, -19.8 ± 5.3 pC/cell) and after exposure to ranolazine (20 μM) (closed, -15.3 ± 11.5 pC/cell, n = 3, p > 0.05, paired). ITI was induced in 3 out of 8 cells. B. Mean normalized Ca2+ wave density in absence and presence of the drug (RAN: 89 % ± 15.8 %, n = 3, p > 0.05, paired). C. Mean systolic Ca2+ density as measured during the final pulse of the conditioning train (RAN: 141.7 % ± 28.1 %, n = 8, p > 0.05, paired).