Abstract

Endothelium-derived vasodilators, i.e., nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin (PGI2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), play important roles in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis. C-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker of inflammation and cardiovascular disease, has been shown to inhibit NO-mediated vasodilation. The goal of this study was to determine whether CRP also affects endothelial arachidonic acid (AA)-prostanoid pathways for vasomotor regulation. Porcine coronary arterioles were isolated and pressurized for vasomotor study, as well as for molecular and biochemical analysis. AA elicited endothelium-dependent vasodilation and PGI2 release. PGI2 synthase (PGI2-S) inhibitor trans-2-phenyl cyclopropylamine blocked vasodilation to AA but not to serotonin (endothelium-dependent NO-mediated vasodilator). Intraluminal administration of a pathophysiological level of CRP (7 μg/mL, 60 minutes) attenuated vasodilations to serotonin and AA but not to nitroprusside, exogenous PGI2, or hydrogen peroxide (endothelium-dependent PGE2 activator). CRP also reduced basal NO production, caused tyrosine nitration of endothelial PGI2-S, and inhibited AA-stimulated PGI2 release from arterioles. Peroxynitrite scavenger urate failed to restore serotonin dilation, but preserved AA-stimulated PGI2 release/dilation and prevented PGI2-S nitration. NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME and superoxide scavenger TEMPOL also protected AA-induced vasodilation. Collectively, our results suggest that CRP stimulates superoxide production and the subsequent formation of peroxynitrite from basal released NO compromises PGI2 synthesis, and thus endothelium-dependent PGI2-mediated dilation, by inhibiting PGI2-S activity through tyrosine nitration. By impairing PGI2-S function, and thus PGI2 release, CRP could promote endothelial dysfunction and participate in the development of coronary artery disease.

Keywords: prostaglandins, microcirculation, free radicals, vasodilation

Introduction

Under physiological conditions, the endothelial cells play an important role in regulating vascular tone and in maintaining an anti-thrombogenic layer through the release of substances such as nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGI2). In this process, NO is produced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) during the enzymatic conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline [1], while PGI2 is formed from arachidonic acid (AA) through a series of enzymatic conversions mediated by cyclooxygenase (COX) and PGI2 synthase (PGI2-S) [2]. Both NO and prostacyclin can increase local tissue perfusion and maintain microvascular homeostasis by eliciting vasodilation and inhibiting platelet and inflammatory cell adherence to the vessel wall. In the coronary microvascular endothelium of the pig, PGI2 and another vasodilator prostanoid, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), have been found to be predominant products of COX metabolism [3]. Reduced bioavailability of one or all of these protective endothelial factors results in vascular dysfunction, a condition that has been documented in patients with hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and angina [4, 5]. Since inflammation is recognized as a key event in the development of these cardiovascular complications [6–8], identification of risk factors that cause vascular dysfunction associated with inflammation is of utmost importance in understanding the complex mechanisms behind the initiation and progression of vascular diseases.

Accumulating clinical evidence indicates that C-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker of inflammation and cardiovascular disease, is emerging as a novel risk factor. The atherogenic potential of CRP, in the absence of traditional risk factors, was recently suggested from results of the landmark JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) study. This randomized trial of over 17,000 apparently healthy individuals with elevated CRP (≥2 μg/mL) showed that statin therapy significantly reduced the CRP levels along with the incidence of major cardiovascular events [9]. Although this study does not provide a causal role for CRP, it is reasonable to postulate that CRP may be actively involved in promoting adverse outcomes due to its proatherogenic effects on vascular cells [10]. These properties, characterized under cell culture conditions, include reduction of endothelial NO bioavailability [11–13], upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules [14], generation of superoxide in vascular cells [15, 16], and stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration [16]. Recent studies using intact vessel and whole animal approaches from our [17, 18] and other laboratories [19–21] support the context of negative impact of CRP on eNOS/NO-mediated biological function, but its impact on COX-related vascular regulation remains undefined. Since PGI2-S has been reported to be susceptible to tyrosine nitration in inflammatory states such as atherosclerosis [22] and diabetes [23] and since peroxynitrite can be formed by the NO-superoxide reaction, in the present study we tested the hypothesis that proinflammatory CRP selectively inhibits endothelium-dependent PGI2-induced dilation but not PGE2-induced dilation of coronary arterioles through peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration of PGI2-S.

Materials and Methods

Functional Assessment of Isolated Coronary Arterioles

The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996). All animal procedures were approved by the Scott & White Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. As described previously [24], pigs (8–12 weeks old of either sex; 7–10 kg) were anesthetized with pentobarbital (15–20 mg/kg) and the heart was quickly excised. Individual subepicardial arterioles (≈1 mm in length; 40–80 μm in internal diameter in situ) were dissected out for in vitro study as described previously [24]. Vessels were cannulated and pressurized to 60 cm H2O luminal pressure. After developing basal tone, the relative contribution of NO and PGI2 to vasodilations to endothelium-dependent NOS-pathway agonist serotonin (0.1 nM to 0.1 μM) [25] and COX-pathway agonist arachidonic acid (AA, 10 μM) [26] were established in the presence of NOS inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 10 μM) and PGI2-S inhibitor trans-2-phenyl cyclopropylamine (TPC, 100 μM) [27], respectively. The role of endothelium in mediating AA-induced dilation was determined before and after endothelial removal by luminal perfusion of non-ionic detergent CHAPS (0.4%) as described previously [25, 26]. To assess the effect of CRP on NO- and prostanoid-mediated vasodilations, vasodilator responses to the aforementioned agonists and to NO donor sodium nitroprusside (0.1 nM to 100 μM), exogenous PGI2 (1 μM, Calbiochem), and endothelium-dependent PGE2 activator hydrogen peroxide (30 μM) [3] were established before and after 60-minute intraluminal incubation with CRP (7 μg/mL) [28]. The involvement of superoxide and peroxynitrite in mediating the CRP effect on AA-induced vasodilation was determined after incubation with CRP combined with superoxide scavenger 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPOL, 1 mM) [29, 30] or peroxynitrite scavenger urate (100 μM) [15, 31]. The contribution of NO to the effect of CRP on AA-induced dilation was examined with L-NAME (10 μM) treatment. Lastly, the potential role of peroxynitrite in the CRP effect on NO-mediated dilation was examined in a separate group by determining dilation to serotonin before and after co-incubation with CRP and urate (100 μM). All drugs were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise noted. The human recombinant CRP (Calbiochem) was initially dialyzed to remove sodium azide, which is present as a preservative in commercial preparations of CRP. Endotoxin, which can affect endothelial function [32], was also removed from the CRP by using Detoxi-Gel Columns (Pierce) and was found to be at the level [<0.06 EU/mL or 6 pg/mL by Limulus assay (Cambrex)] insufficient to affect vasomotor function [32].

NO Assay

Basal release of NO from isolated coronary arterioles (5–7 vessels/sample) was evaluated by measuring nitrite levels, a major breakdown product of NO, using a chemiluminescence NO analyzer (Sievers Instruments) as described previously [25, 33]. Vessels were incubated with physiological salt solution in the absence (vehicle) or presence of CRP (7 μg/mL) or CRP plus TEMPOL (1 mM) for 60 minutes and then nitrite levels were measured in the solution. Protein levels were quantified by bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce) and were used to normalize the nitrite production.

PGI2 Assay

Isolated coronary arterioles (3 vessels/tube) were incubated with vehicle, CRP (7 μg/mL), urate (100 μM), or CRP plus urate (100 μM) for 60 minutes. Halfway through the 60-minute incubation, AA (10 μM) was also added. Vehicle control studies (no AA or CRP) were run in parallel with experimental groups to determine basal PGI2 release. At the end of treatment, samples were collected for measurement of 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α (PGF1α), a stable metabolite of PGI2, using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman) as described previously [3]. Protein levels were quantified and used to normalize the PGF1α release.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

To determine cellular localization of CRP-induced tyrosine nitration of PGI2-S by peroxynitrite, isolated and pressurized coronary arterioles were incubated intraluminally with vehicle, CRP (7 μg/mL), or CRP plus urate (100 μM) for 60 minutes before embedding in OCT compound. Frozen sections (10-μm-thick) were immunolabeled with anti-PGI2-S antibody (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz) or anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (1:100, Upstate). Afterwards, the slides were incubated with FITC-labeled or Cy3-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson Laboratories) and then observed using fluorescence microscopy as described previously [25].

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

To quantify the tyrosine nitration of PGI2-S, immunoprecipitation of nitrated proteins from isolated coronary arterioles (4–5 vessels per sample) was performed following incubation with vehicle, CRP (7 μg/mL) or peroxynitrite (10 μM, positive control) for 60 minutes. Equal amounts of protein (10–20 μg) from each sample were incubated with anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (1:100 dilution, Upstate Biotechnology). Immune complexes were precipitated with 20 μl Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For Western blot analysis, total immune complexes or protein samples from total vessel lysate (5 μg) were separated by Tris-Glycine SDS-PAGE (4–15%, Bio-Rad), transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and then incubated with anti-PGI2-S antibody (1:500 dilution, Santa Cruz). Membranes containing the total vessel lysate samples were stripped and re-probed with anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1000, Santa Cruz) to confirm equal loading. After incubation with appropriate secondary antibody, membranes were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce). Densitometric analyses of immunoblots were performed by ImageJ software. Results for nitrated PGI2-S were normalized by arbitrarily setting the density of control vessels to 1.0 and total PGI2-S was normalized to total GAPDH.

Data Analysis

Diameter changes to agonists were normalized to maximum diameter changes in response to 100 μM sodium nitroprusside and expressed as a percentage of maximal dilation [33]. Statistical comparisons were performed by Student’s t test or by analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni multiple-range test, as appropriate. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Effect of CRP on PGI2-Mediated Vasodilation

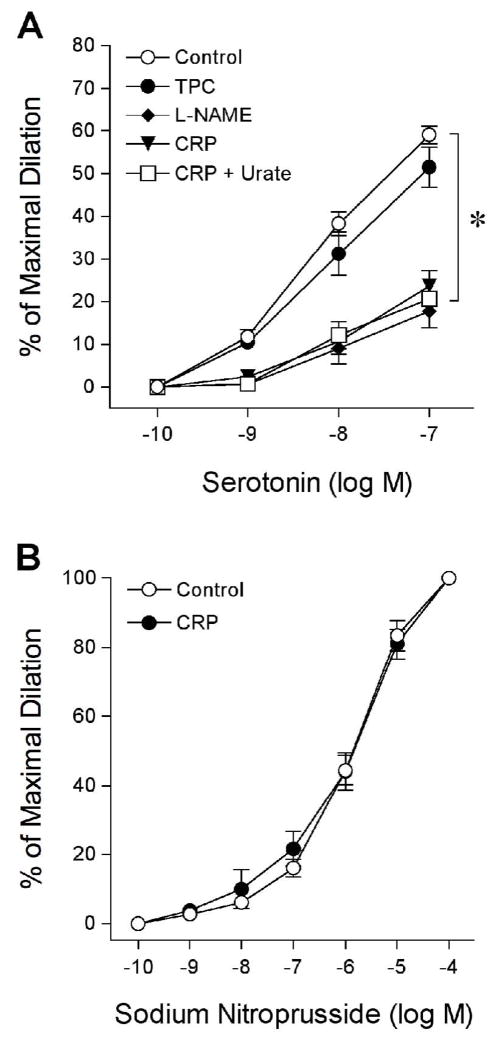

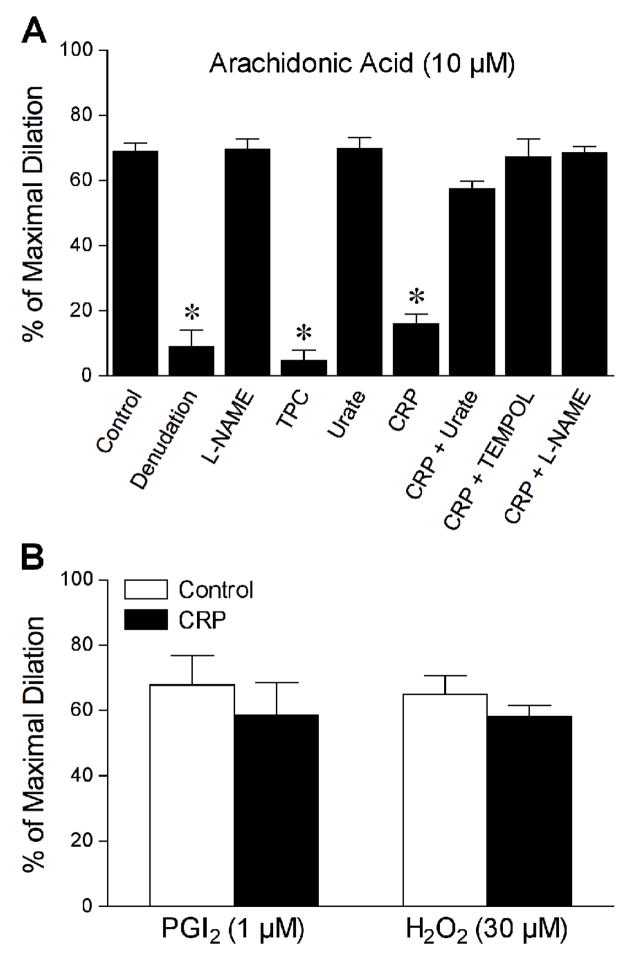

The effect of CRP on PGI2-mediated vasomotor function was directly studied in the isolated porcine coronary arterioles. All isolated arterioles developed a similar level of basal tone about 66 ± 1% of maximal diameter (91 ± 3 μm; range 68–113 μm) within 40 minutes. We have previously demonstrated that serotonin-induced dilation was reduced by NOS inhibitor L-NAME and by CRP [17]. However, it is not clear whether PGI2 is involved in vasodilation elicited by serotonin and whether peroxynitrite contributes to the CRP-induced vascular dysfunction. In the present study, treating the vessels with L-NAME, but not PGI2-S inhibitor TPC, attenuated the vascular response to serotonin (Figure 1A). Consistent with previous findings [17], CRP significantly inhibited serotonin-induced vasodilation without altering the endothelium-independent vasodilation to sodium nitroprusside; but this inhibition was not affected by peroxynitrite scavenger urate (Figure 1B). These results suggest that serotonin-induced vasodilation is not mediated by PGI2 and that peroxynitrite does not contribute to the impaired endothelium-dependent NO-mediated vasodilation. In contrast to serotonin, AA-induced vasodilation was insensitive to L-NAME but was nearly abolished by endothelial removal or by TPC (Figure 2A), indicating that the endothelial production of PGI2 via PGI2-S mediated this response. In a similar manner as TPC treatment, CRP significantly attenuated the AA-induced vasodilator response (Figure 2A). However, the inability of CRP to alter dilation of coronary arterioles to exogenous PGI2 or endothelium-dependent PGE2 activator hydrogen peroxide[3] (Figure 2B) suggests a specific inhibitory action of CRP on the bioavailability of endothelial PGI2 in response to AA stimulation.

Figure 1.

Vasomotor responses to serotonin and sodium nitroprusside. (A) Dilation of coronary arterioles to serotonin was examined before (Control, n = 16) and after treating with PGI2-S inhibitor TPC (100 μM, n = 4), NOS inhibitor L-NAME (10 μM, n = 3), or CRP (7 μg/mL) in the absence (n = 5) and presence of peroxynitrite scavenger urate (100 μM, n = 4). *P < 0.05 vs. Control. (B) Coronary arteriolar dilation to sodium nitroprusside was examined before (Control) and after incubation with CRP (7 μg/mL, n = 3). n = number of vessels (one per animal).

Figure 2.

CRP inhibits PGI2-S-mediated vasodilation. (A) Dilation of coronary arterioles to arachidonic acid (10 μM) was examined before (Control, n = 37) and after various treatments: endothelial denudation (n = 4), NOS inhibitor L-NAME (10 μM, n = 4), PGI2-S-inhibitor TPC (100 μM, n = 5), or peroxynitrite scavenger urate (100 μM, n = 4). The arachidonic-induced dilation was also examined after treating the vessels with CRP alone (7 μg/mL, n = 7) or in combination with urate (100 μM, n = 5), superoxide scavenger TEMPOL (1 mM, n = 4), or L-NAME (10 μM, n = 4). (B) Coronary arteriolar dilation to exogenous PGI2 (1 μM, n = 5) or endothelium-dependent PGE2 activator hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30 μM, n = 7) was examined before (Control) and after CRP treatment (7 μg/mL). n = number of vessels (one per animal). *P < 0.05 vs. Control.

Impact of Peroxynitrite on PGI2-S-Mediated Vasodilation

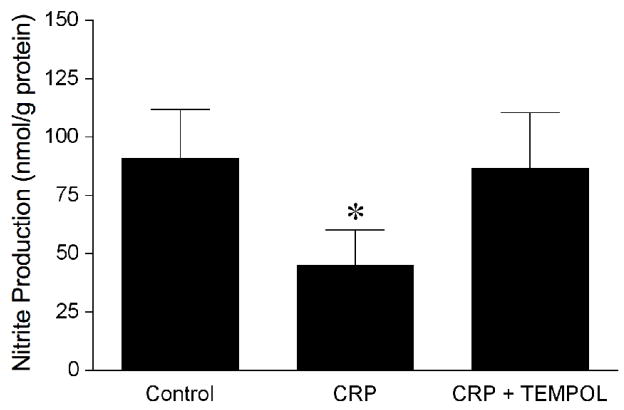

Since PGI2-S is susceptible to peroxynitrite [34, 35], we examined the influence of this reactive oxygen species on AA-induced vasodilation. The peroxynitrite scavenger urate did not alter AA-induced vasodilation but nearly abolished the inhibitory effect of CRP (Figure 2A), suggesting that the observed vascular dysfunction in response to AA is peroxynitrite-dependent. Because scavenging of NO by superoxide could result in the formation of peroxynitrite, we further examined whether superoxide and NO were contributing to the impaired vasodilation to AA. The inhibitory effect of CRP on AA-induced dilation was not observed in the presence of either superoxide scavenger TEMPOL or L-NAME (Figure 2A), suggesting the involvement of superoxide and NO in this vascular dysfunction. Because L-NAME did not affect vasodilation to AA but prevented the inhibitory effect of CRP, it is likely that the peroxynitrite is derived from the basal released NO. This idea was supported by the ability of CRP to reduce the resting level of NO (Control: 91 ± 21 nmol/g protein vs. CRP: 45 ± 15 nmol/g protein; P = 0.02; Figure 3). The reduction in basal NO by CRP had a tendency to reduce resting vascular tone, but not in a significant manner (Control: 68 ± 3 % of maximal diameter vs. CRP: 66 ± 2 % of maximal diameter; n = 7 vessels). The reduction of basal level of NO by CRP was not observed in the presence of TEMPOL (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

CRP inhibits basal release of NO. Chemiluminescence measurement of nitrite production (i.e., index of NO release) was performed in the isolated coronary arterioles treated with vehicle (Control, n=4), CRP (7 μg/mL, n=4), or the combination of CRP and TEMPOL (1 mM, n = 3). n = number of experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. Control.

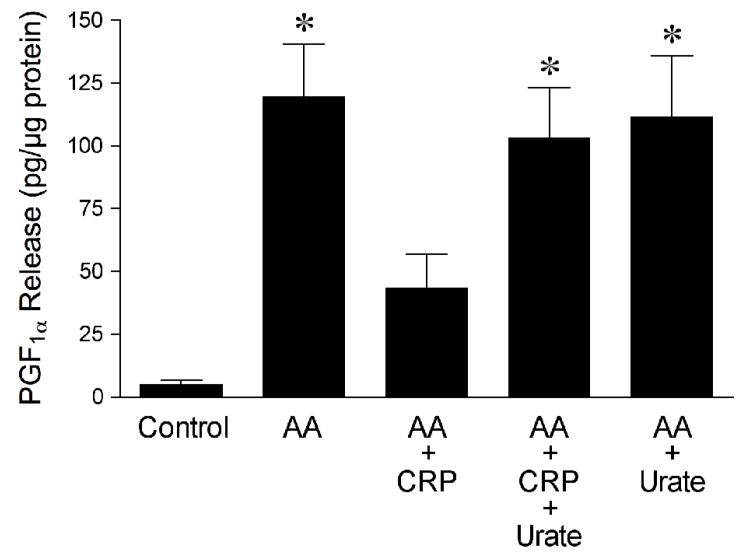

Effect of CRP on AA-Induced PGI2 Production

To support the functional study, the production of PGI2 in response to AA was determined in the coronary arterioles with and without CRP treatment. Figure 4 shows that AA (10 μM) significantly increased the production of PGF1α, a stable metabolite of PGI2; but this increase was attenuated in the vessels treated with CRP. In the presence of urate (100 μM), the inhibitory effect of CRP on PGF1α release was abolished. However, urate alone had no influence on AA-induced PGF1α production (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

CRP inhibits arachidonic acid (AA)-stimulated production of PGI2. Immunoassay measurement of PGF1α release (i.e., index of PGI2 production) was performed in isolated coronary arterioles treated with vehicle (Control, n = 5), AA (10 μM, n = 5), AA plus CRP (7 μg/mL, n = 5), AA plus CRP and urate (100 μM, n = 5), or AA plus urate alone (n = 3). n = number of experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. Control or AA + CRP.

Effect of CRP on PGI2-S Expression and Tyrosine Nitration

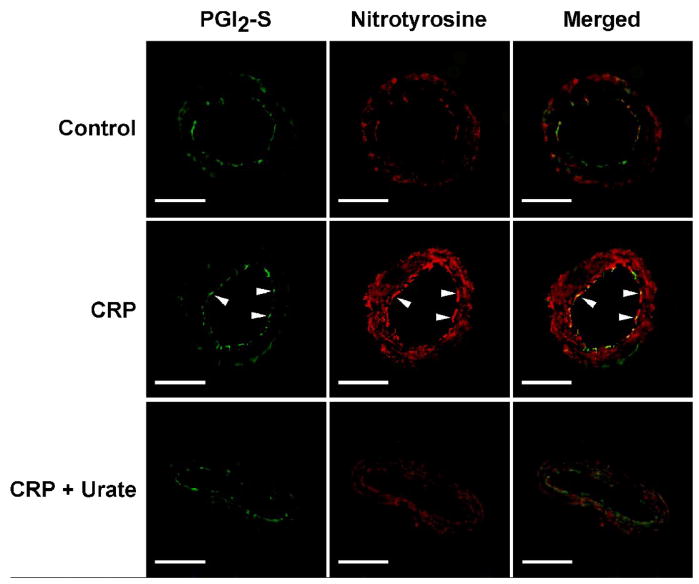

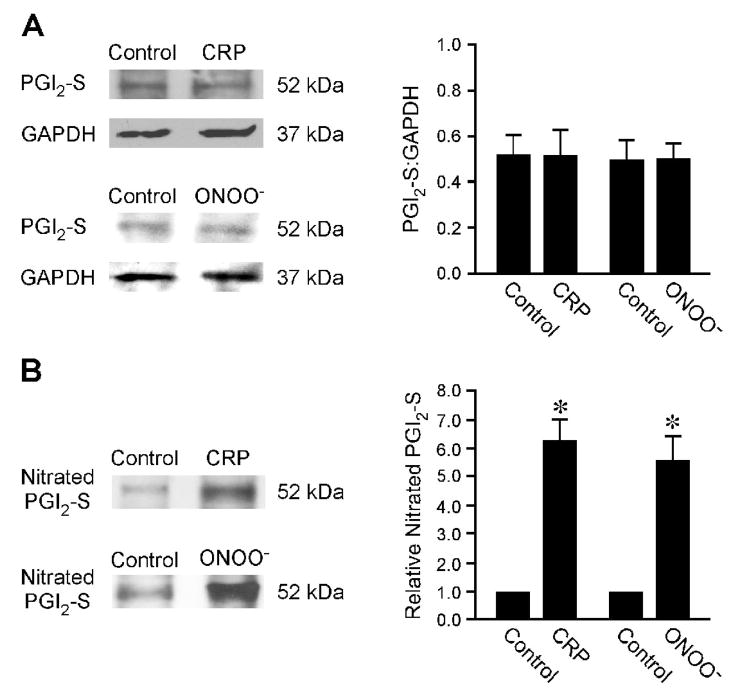

The reduction of PGI2 can be a result of downregulation of PGI2-S protein and/or inactivation of its activity by peroxynitrite via tyrosine nitration. Immunohistochemical analysis shows that PGI2-S was expressed in the arteriolar wall, especially the endothelial cells, with a relatively low level of nitrotyrosine (Figure 5). In vessels treated with CRP, there was no evident change in the PGI2-S level. However, the nitrotyrosine staining was markedly increased in both the endothelial and smooth muscle layers. Overlap of the images showed co-localization of PGI2-S and nitrotyrosine staining in the vascular endothelium, suggesting tyrosine nitration of the enzyme in the presence of CRP. The peroxynitrite scavenger urate did not alter the relative intensity of PGI2-S staining but prevented the increase of nitrotyrosine by CRP in the arteriolar wall (Figure 5). Consistent with the immunohistochemical results, quantitative protein analysis showed that CRP, as well as exogenous peroxynitrite, did not alter the expression level of PGI2-S (Figure 6A). However, both CRP and peroxynitrite significantly increased the amount of tyrosine-nitrated PGI2-S (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical detection of peroxynitrite and nitrated prostacyclin synthase (PGI2-S) in coronary arterioles. Isolated and pressurized porcine coronary arterioles were incubated with vehicle (Control), CRP (7 μg/mL), or CRP plus urate (100 μM) for 60 minutes, followed by addition of anti-PGI2-S (green) or anti-nitrotyrosine (red) antibody. The merged images show the overlap staining (yellow) of PGI2-S and nitrotyrosine corresponding to nitrated PGI2-S. Data shown are representative of three separate experiments. White arrowheads denote endothelial cells. Bar = 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Expression of prostacyclin synthase (PGI2-S) and nitrated PGI2-S in isolated coronary arterioles. (A) The left panel shows immunoblots of PGI2-S and GAPDH in vessels treated with vehicle (Control), CRP (7 μg/mL), or peroxynitrite (ONOO−, 10 μM, positive control) for 60 minutes. The right panel shows the total PGI2-S protein normalized with corresponding GAPDH protein. CRP or peroxynitrite treatments did not change the total PGI2-S expression in coronary arterioles. Data represent three independent experiments. (B) The left panel shows immunoblots of nitrated PGI2-S in nitrotyrosine immunoprecipitates from vessels treated with vehicle (Control), CRP (7 μg/mL), or peroxynitrite (ONOO−, 10 μM) for 60 minutes. The right panel shows the relative amount of nitrated PGI2-S. The amount of nitrated PGI2-S was significantly increased in CRP- and peroxynitrite-treated coronary arterioles. Data represent three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. Control.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that CRP, at a concentration (7 μg/mL) known to predict cardiovascular risk [28], inhibits endogenous PGI2-mediated but not PGE2-mediated dilation of coronary arterioles by stimulating formation of peroxynitrite, a reactive oxygen species that is generated by the reaction of basal NO and CRP-induced superoxide. By activating signaling mechanisms that lead to reactive oxygen species formation in endothelial cells, CRP appears to exert detrimental effects on the bioavailability of two important endothelium-derived factors, NO and PGI2, for vasodilation.

CRP and Coronary Circulation

Several research groups have extensively studied the proinflammatory and proatherothrombotic vascular properties of CRP in the past five years. A comprehensive review of these properties by Jialal et al points out that CRP’s cellular targets include endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and monocytes/macrophages [10]. This overwhelming evidence from in vitro studies in both human and animal tissue assigns a pathogenic role to CRP, rather than just its widely accepted property as a marker of inflammation and cardiovascular risk. The strong correlation between high CRP levels (3 to 10 μg/mL) and diminished vascular reactivity in both peripheral and coronary circulations of human patients also supports the idea of CRP as a mediator of vascular dysfunction [36–39]. In the coronary circulation of patients with normal and diseased vessels, local CRP production directly correlated with the increase in microvascular resistance [40], a finding that agrees with the results presented in the present study.

CRP and Prostanoid-Mediated Vasodilation

We, and other laboratories, have previously demonstrated that CRP, either human recombinant [17] or purified, native form from human serum [41] or ascitic/pleural fluid [42], elicits endothelial dysfunction, including scavenging of the vasodilator NO through increased superoxide production [17, 42]. The chemical reaction between superoxide and NO leads to the formation of peroxynitrite, another reactive oxygen species [23]. Peroxynitrite is a highly reactive molecule that can oxidize or nitrate many subcellular targets, resulting in significant alteration of cellular homeostasis [43, 44]. One potential outcome of intracellular peroxynitrite formation is nitration of PGI2-S, the process that has been suggested to inactivate its enzymatic activity and consequently attenuates PGI2 synthesis [34, 35]. A recent study by Venugopal et al demonstrated that CRP inhibits PGI2 release in cultured human aortic endothelial cells [15]. However, it is unclear whether this inhibitory pathway exists in the intact vascular tissue exerting functional consequences. In the present study, we examined the effect of CRP on vasodilation to endogenously released PGI2 or PGE2 during AA or hydrogen peroxide stimulation, respectively. In the endothelium, AA is metabolized by COX to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2), which can then be broken down by several prostanoid enzymes, including conversion to PGI2 by PGI2-S [2]. Our previous and present results support this signaling cascade in the coronary microcirculation since COX inhibitor indomethacin [26], endothelial removal (Figure 2) and PGI2-S inhibitor TPC (Figure 2) blocked the coronary arteriolar dilation to AA. On the other hand, hydrogen peroxide elicits indomethacin-sensitive dilation of coronary arterioles via selective activation of endothelial PGE2 production [3]. In a similar result as pharmacologic blockade of PGI2-S (by TPC), incubation of coronary arterioles with CRP caused a reduction in the vasodilation to AA without altering the response to hydrogen peroxide. Collectively, these results suggest that CRP selectively impairs PGI2 but not PGE2 production downstream from COX activation.

Peroxynitrite and CRP-induced Dysfunction

It is likely that a reduction in the endothelial production of PGI2 contributed to the vascular impairment since coronary arteriolar dilation to exogenous PGI2 was unaffected by CRP. Indeed, CRP diminished the AA-stimulated release of PGI2 from coronary arterioles in a manner sensitive to the peroxynitrite scavenger urate, suggesting a prominent role of peroxynitrite in the vascular dysfunction. It appears that peroxynitrite exerts its inhibitory action by increasing tyrosine nitration of PGI2-S in the endothelium, since immunohistochemical results showed the increased nitrotyrosine, a molecular footprint for peroxynitrite formation [43], overlapped with focal expression of PGI2-S in the endothelial cells in a urate-sensitive manner. Moreover, immunoprecipitation of nitrotyrosine-containing proteins revealed increased levels of nitrated PGI2-S in coronary arterioles treated with either CRP or peroxynitrite, whereas the PGI2-S expression remained unchanged. CRP-induced peroxynitrite did not interrupt COX function because COX/PGE2 -mediated vasodilation to hydrogen peroxide remained intact. Our result is consistent with previous evidence showing the peroxynitrite selectively inhibits PGH2 conversion to PGI2 without altering PGH2 conversion to PGE2 in bovine coronary arteries [45]. Collectively, these results suggest a reduction of PGI2-S activity by tyrosine nitration contributes to the observed reduction in PGI2 synthesis.

Since AA-induced dilation is independent of NO (Figure 2), the formation of peroxynitrite is likely associated with the NO generated at resting conditions. It appears that the interaction of basal NO with superoxide is sufficient to produce effective levels of peroxynitrite to elicit PGI2 deficiency because urate and L-NAME, as well as superoxide scavenger TEMPOL, prevented the inhibitory action of CRP on AA-induced vasodilation. In conjunction with previous reports [17], the present findings suggest that the impaired NO-mediated vasodilation by CRP is primarily due to the reduction of endothelial NO bioavailability by the scavenging effect of superoxide rather than the secondary increase in peroxynitrite since urate treatment was ineffective in preserving the vasodilator response to serotonin (Figure 1). Interestingly, superoxide production via p38-mediated NAD(P)H oxidase activation appears to be responsible for the reduced NO bioavailability in the intact coronary arterioles subjected to CRP insult [17]. In contrast, alteration in eNOS phosphorylation contributes to CRP-induced endothelial dysfunction in cultured endothelial cells [11]. Although the explanation for this discrepancy is currently unavailable, the difference in experimental settings might be a major factor. It is worth noting that our present study was performed in the absence of luminal flow. Since endothelial cells respond to flow by increasing NO release [24, 26], it is expected that the NO component via eNOS contributing to PGI2 deficiency would be more pronounced in vivo (i.e., with luminal flow). Moreover, in view of the close intracellular proximity of PGI2-S [46], eNOS [47] and NAD(P)H oxidase [48] in the plasmalemmal caveolae of endothelial cells, the profound increase in peroxynitrite by CRP could possibly eradicate the synthesis of PGI2, in combination with the reduction of NO bioavailability, to promote platelet aggregation and atherogenesis. Interestingly, the present results are consistent with the reported major contribution of basal levels of NO to peroxynitrite production in human arteries with cardiovascular disease [49].

Study Limitations

A limitation of the present study is that we only evaluated subepicardial arterioles. Notably, previous evidence from our group and other laboratories has demonstrated heterogeneity in vascular reactivity between subepicardial and subendocardial arterioles [50–54]. Since the subendocardium is more vulnerable to ischemia, future investigation of CRP and vasodilator function of subendocardial arterioles is warranted. We also studied isolated arterioles exposed to constant transmural pressure under nonpulsatile conditions without flow. Since the transmural pressure of coronary arterioles in vivo is pulsatile, which has been shown to influence vasomotor activity in vivo [54, 55] and in vitro [55], the extent of the CRP effect on vascular function under this condition may be different. In addition, we assessed the prostanoid vasodilator function following CRP exposure, but it remains unknown whether CRP affects prostanoid vasoconstrictor pathways such as thromboxane A2, PGH2 and prostaglandin F2α despite the fact that the resting coronary vasomotor tone was not altered by CRP. It should also be noted that current studies were performed using juvenile pigs, so we are uncertain whether similar results can be obtained in adult animals, although we have previously demonstrated comparable vasomotor regulation and responses in juvenile and adult healthy pigs [25, 52].

Conclusions

We have shown for the first time that CRP inhibits endothelium-dependent PGI2-mediated but not PGE2-mediated dilation of porcine coronary arterioles by increasing the generation of vascular peroxynitrite. The formation of peroxynitrite from basal released NO and CRP-induced superoxide appears to inactivate endothelial PGI2-S via tyrosine nitration. We have also demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of CRP on endothelium-dependent NO-mediated vasodilation is not altered by peroxynitrite but rather by superoxide. Taken together, our findings support a pathogenic role of CRP in vascular dysfunction related to endothelial NO and PGI2 deficiency. Although this deficit can alter vascular tone and possibly limit coronary collateral growth [56, 57], it is reasonable to speculate that patients with coronary artery disease may compensate to provide sufficient blood flow by maintaining vasodilator capacity via endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor [17] and/or undergoing outward remodeling of resistance vessels [58]. Further investigation on the integrative impact of CRP on coronary flow regulation in vivo is warranted. In light of the recent clinical benefit of lowering CRP in the JUPITER study [9] and the unfavorable qualities of CRP in both vasomotor regulation and vascular homeostasis, a better understanding of the direct influence of CRP on microvascular function could assist in targeting treatment for vascular disease in association with elevated CRP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Heart Association [0235258N to T.W.H.] and the National Institutes of Health [HL-71761 to L.K.]. We gratefully thank Dr. Xin Xu and Dr. Robert D. Shipley for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stuehr DJ. Mammalian nitric oxide synthases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1411:217–30. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith WL, Garavito RM, DeWitt DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (cyclooxygenases)-1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33157–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thengchaisri N, Kuo L. Hydrogen peroxide induces endothelium-dependent and -independent coronary arteriolar dilation: role of cyclooxygenase and potassium channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2255–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00487.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies MG, Hagen PO. The vascular endothelium. A new horizon. Ann Surg. 1993;218:593–609. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199321850-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neri Serneri G, Gensini G, Abbate R, Castellani S, Bonechi F, Carnovali M, et al. Defective coronary prostaglandin modulation in anginal patients. Am Heart J. 1990;120:12–21. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90155-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P, Ridker PM. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: role of C-reactive protein in risk assessment. Am J Med. 2004;116:9S–16S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson T, Goon PK, Lip GY. Endothelial progenitor cells, endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress in hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1079–88. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aljada A. Endothelium, inflammation, and diabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2003;1:3–21. doi: 10.1089/154041903321648225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr, Kastelein JJ, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jialal I, Devaraj S, Venugopal SK. C-reactive protein: risk marker or mediator in atherothrombosis? Hypertension. 2004;44:6–11. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000130484.20501.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mineo C, Gormley A, Yunahnn I, Osborne-Lawrence S, Gibson L, Hahner L, et al. FCγRIIB mediates C-reactive protein inhibition of endothelial NO synthase. Circ Res. 2005;97:1124–31. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194323.77203.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venugopal SK, Devaraj S, Yuhanna I, Shaul P, Jialal I. Demonstration that C-reactive protein decreases eNOS expression and bioactivity in human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:1439–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000033116.22237.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verma S, Wang CH, Li SH, Dumont AS, Fedak PW, Badiwala MV, et al. A self-fulfilling prophecy: C-reactive protein attenuates nitric oxide production and inhibits angiogenesis. Circulation. 2002;106:913–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029802.88087.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasceri V, Willerson JT, Yeh ET. Direct proinflammatory effect of C-reactive protein on human endothelial cells. Circulation. 2000;102:2165–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venugopal SK, Devaraj S, Jialal I. C-reactive protein decreases prostacyclin release from human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation. 2003;108:1676–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094736.10595.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CH, Li SH, Weisel RD, Fedak PW, Dumont AS, Szmitko P, et al. C-reactive protein upregulates angiotensin type 1 receptors in vascular smooth muscle. Circulation. 2003;107:1783–90. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000061916.95736.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qamirani E, Ren Y, Kuo L, Hein TW. C-reactive protein inhibits endothelium-dependent NO-mediated dilation in coronary arterioles by activating p38 kinase and NAD(P)H oxidase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:995–1001. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000159890.10526.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagaoka T, Kuo L, Ren Y, Yoshida A, Hein TW. C-reactive protein inhibits endothelium-dependent nitric oxide-mediated dilation of retinal arterioles via enhanced superoxide production. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2053–60. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grad E, Golomb M, Mor-Yosef I, Koroukhov N, Lotan C, Edelman ER, et al. Transgenic expression of human C-reactive protein suppresses endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and bioactivity after vascular injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H489–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01418.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz R, Osborne-Lawrence S, Hahner L, Gibson LL, Gormley AK, Vongpatanasin W, et al. C-reactive protein downregulates endothelial NO synthase and attenuates reendothelialization in vivo in mice. Circ Res. 2007;100:1452–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000267745.03488.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teoh H, Quan A, Lovren F, Wang G, Tirgari S, Szmitko PE, et al. Impaired endothelial function in C-reactive protein overexpressing mice. Atherosclerosis. 2008;201:318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou MH, Leist M, Ullrich V. Selective nitration of prostacyclin synthase and defective vasorelaxation in atherosclerotic bovine coronary arteries. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1359–65. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65390-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou MH, Cohen R, Ullrich V. Peroxynitrite and vascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Endothelium. 2004;11:89–97. doi: 10.1080/10623320490482619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo L, Chilian WM, Davis MJ. Interaction of pressure- and flow-induced responses in porcine coronary resistance vessels. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H1706–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, Hein TW, Wang W, Chang CI, Kuo L. Constitutive expression of arginase in microvascular endothelial cells counteracts nitric oxide-mediated vasodilatory function. FASEB J. 2001;15:1264–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0681fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hein TW, Liao JC, Kuo L. oxLDL specifically impairs endothelium-dependent, NO-mediated dilation of coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H175–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardy P, Abran D, Hou X, Lahaie I, Peri K, Asselin P, et al. A major role for prostacyclin in nitric oxide–induced ocular vasorelaxation in the piglet. Circ Res. 1998;83:721–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.7.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeh ET, Willerson JT. Coming of age of C-reactive protein: using inflammation markers in cardiology. Circulation. 2003;107:370–1. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000053731.05365.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C, Hein TW, Wang W, Kuo L. Divergent roles of angiotensin II AT1 and AT2 receptors in modulating coronary microvascular function. Circ Res. 2003;92:322–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000056759.53828.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnackenberg CG, Wilcox CS. Two-week administration of tempol attenuates both hypertension and renal excretion of 8-iso prostaglandin F2α. Hypertension. 1999;33:424–8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Gutterman DD, Rusch NJ, Bubolz A, Liu Y. Nitration and functional loss of voltage-gated K+ channels in rat coronary microvessels exposed to high glucose. Diabetes. 2004;53:2436–42. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo L, Chilian WM, Davis MJ, Laughlin MH. Endotoxin impairs flow-induced vasodilation of porcine coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1838–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.6.H1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hein TW, Kuo L. cAMP-independent dilation of coronary arterioles to adenosine: role of nitric oxide, G proteins, and KATP channels. Circ Res. 1999;85:634–42. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hink U, Oelze M, Kolb P, Bachschmid M, Zou MH, Daiber A, et al. Role for peroxynitrite in the inhibition of prostacyclin synthase in nitrate tolerance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1826–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou MH, Bachschmid M. Hypoxia-reoxygenation triggers coronary vasospasm in isolated bovine coronary arteries via tyrosine nitration of prostacyclin synthase. J Exp Med. 1999;190:135–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson R, Dart AM, Starr J, Shaw J, Chin-Dusting JP. Plasma C-reactive protein, but not protein S, VCAM-1, von Willebrand factor or P-selectin, is associated with endothelium dysfunction in coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2004;172:345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fichtlscherer S, Breuer S, Schachinger V, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. C-reactive protein levels determine systemic nitric oxide bioavailability in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1412–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teragawa H, Fukuda Y, Matsuda K, Ueda K, Higashi Y, Oshima T, et al. Relation between C reactive protein concentrations and coronary microvascular endothelial function. Heart. 2004;90:750–4. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.022269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomai F, Ribichini F, Ghini AS, Ferrero V, Ando G, Vassanelli C, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2099–105. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Date H, Imamura T, Sumi T, Ishikawa T, Kawagoe J, Onitsuka H, et al. Effects of interleukin-6 produced in coronary circulation on production of C-reactive protein and coronary microvascular resistance. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:849–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devaraj S, Venugopal S, Jialal I. Native pentameric C-reactive protein displays more potent pro-atherogenic activities in human aortic endothelial cells than modified C-reactive protein. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh U, Devaraj S, Vasquez-Vivar J, Jialal I. C-reactive protein decreases endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity via uncoupling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1424–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beckman JS, Chen J, Ischiropoulos H, Crow JP. Oxidative chemistry of peroxynitrite. Methods Enzymol. 1994;233:229–40. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)33026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zou M, Jendral M, Ullrich V. Prostaglandin endoperoxide-dependent vasospasm in bovine coronary arteries after nitration of prostacyclin synthase. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1283–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spisni E, Griffoni C, Santi S, Riccio M, Marulli R, Bartolini G, et al. Colocalization prostacyclin (PGI2) synthase–caveolin-1 in endothelial cells and new roles for PGI2 in angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2001;266:31–43. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaul PW, Smart EJ, Robinson EJ, German Z, Yuhanna IS, Ying Y, et al. Acylation targets endothelial nitric-oxide synthase to plasmalemmal caveolae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6518–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ushio-Fukai M. Localizing NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. Sci STKE. 2006:8. doi: 10.1126/stke.3492006re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guzik T, West N, Pillai R, Taggart D, Channon K. Nitric oxide modulates superoxide release and peroxynitrite formation in human blood vessels. Hypertension. 2002;39:1088–94. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000018041.48432.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuo L, Davis MJ, Chilian WM. Myogenic activity in isolated subepicardial and subendocardial coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H1558–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.6.H1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hein TW, Zhang C, Wang W, Kuo L. Heterogeneous β2-adrenoceptor expression and dilation in coronary arterioles across the left ventricular wall. Circulation. 2004;110:2708–12. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134962.22830.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang C, Hein TW, Kuo L. Transmural difference in coronary arteriolar dilation to adenosine: effect of luminal pressure and KATP channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2612–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sorop O, Spaan JA, VanBavel E. Pulsation-induced dilation of subendocardial and subepicardial arterioles: effect on vasodilator sensitivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H311–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merkus D, Vergroesen I, Hiramatsu O, Tachibana H, Nakamoto H, Toyota E, et al. Stenosis differentially affects subendocardial and subepicardial arterioles in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1674–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goto M, VanBavel E, Giezeman MJ, Spaan JA. Vasodilatory effect of pulsatile pressure on coronary resistance vessels. Circ Res. 1996;79:1039–45. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.5.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gulec S, Ozdemir AO, Maradit-Kremers H, Dincer I, Atmaca Y, Erol C. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein are associated with impaired coronary collateral development. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:369–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerner A, Gruberg L, Goldberg A, Roguin A, Lavie P, Lavie L, et al. Relation of C-reactive protein to coronary collaterals in patients with stable angina pectoris and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:509–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verhoeff BJ, Siebes M, Meuwissen M, Atasever B, Voskuil M, de Winter RJ, et al. Influence of percutaneous coronary intervention on coronary microvascular resistance index. Circulation. 2005;111:76–82. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151610.98409.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]