Abstract

Cytochrome bd is a terminal quinol oxidase in Escherichia coli. Mitochondrial respiration is inhibited at cytochrome bc1 (complex III) by myxothiazol. Mixing purified cytochrome bd oxidase with myxothiazol-inhibited bovine heart submitochondrial particles (SMP) restores up to 50% of the original rotenone-sensitive NADH oxidase and succinate oxidase activities in the absence of exogenous ubiquinone analogues. Complex III bypassed respiration and is saturated at amounts of added cytochrome bd similar to that of other natural respiratory components in SMP. The cytochrome bd tightly binds to the mitochondrial membrane and operates as an intrinsic component of the chimeric respiratory chain.

Keywords: Complex I, Complex II, Cytochrome bd quinol oxidase, Ubiquinone oxidoreduction, Respiratory chain, Mitochondria

1. Introduction

Membranous quinone-reactive proteins are key components of diverse respiratory and photosynthetic electron transfer chains in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. The quinone/quinol (Q) oxidoreduction at specific quinone-reactive sites (Q-sites) in several cases is coupled with the generation of proton-motive force across the coupling membrane. Extremely hydrophobic natural quinones with 6–10 isoprenoid units also function as a mobile membranous redox pool (buffer) in carrying reducing equivalents between the respiratory chain components [1]. In situ studies on enzymology of quinone oxidoreduction are greatly hampered by quantitative limitation of the endogenous substrate/product. When complete coupled or uncoupled NADH or succinate oxidase activities are measured complexes III and IV operate synchronously with the quinone reductases thus making it difficult, if not impossible to dissect catalytic activities of the individual complexes. Thus, several water-soluble synthetic quinone homologues and/or analogues are commonly used for kinetic assays of individual quinone-reactive complexes [2]. Although this approach is useful, it still suffers from a number of limitations. When low concentrations of a Q-type acceptor/donor are used an enzyme does not operate at its maximal turnover and the true initial rate is hard to detect because of accumulation of the reaction product which may act as an inhibitor. For example, this kinetic behavior has been documented for the succinate:ubiquinone reductase reaction catalyzed by complex II [3, 4]. When high concentrations of the water-soluble artificial Q-type acceptors are used as substrate the reaction with other than the natural Q-site associated redox components becomes significant, as exemplified by the loss of rotenone-sensitivity of the NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase reaction catalyzed by complex I at high concentrations of Q1 [5].

Our long-standing interest in the operation of Q-site(s) in mitochondrial membrane-bound NADH and succinate quinone reductases has prompted us to develop reliable assay procedures suitable for studies on steady-state quinone reduction free of those limitations. To achieve this goal we decided to use the purified detergent solublized cytochrome bd quinol oxidase of Escherichia coli [6] as a quinone-regenerating system in a continuous coupled NADH:quinone reductase – quinol oxidase assay. We assumed that complex I, in coupled or uncoupled submitochondrial particles and admittedly uncoupled soluble cytochrome bd quinol oxidase, will operate independently being kinetically connected by exogenously added water soluble quinone. An expected advantage of this approach is that in such a system steady-state complex I operation could be measured at any level of quinone reduction that could be reached by unrestricted variation of relative contents of SMP, quinol oxidase, and total concentration of Q1 in the assay samples. Although this coupled assay was, indeed, operative in the presence of limited amounts of Q1 and “kinetic excess” of quinol oxidase, we found, unexpectedly, that the system was also operative in the absence of any externally added quinones, thus suggesting that endogenous membrane-bound Q10 is accessible to the bacterial quinol oxidase. This report describes some properties of the chimeric respiratory chain assembled from bovine heart SMP and bacterial cytochrome bd quinol oxidase.

2. Materials and Methods

Inside-out bovine heart submitochondrial particles (SMP) were prepared [7], treated with oligomycin, and their NADH and succinate dehydrogenase were activated as described [8]. The cytochrome bd terminal quinol oxidase of E. coli (strain GO105/pTK1) was prepared as described [9]. The final preparation (2 mg/ml) was dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 5 mM EDTA and 0.05% N-lauroylsarcosine. The heme d content (~10 nmol/mg of protein) was estimated from the dithionite-reduced-minus-“air-oxidized” spectra assuming Δε628–607=10,800 M−1 cm−1. All preparations were stored in liquid nitrogen and thawed just before use. The standard reaction mixture was comprised of 0.25 M sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7), and 0.2 mM EDTA. When appropriate, NADH (0.1 mM), potassium succinate (20 mM), Q1H2, Q1 or Q2, and myxothiazol (0.5 μM) were added to the standard reaction mixture. All assays were performed at 37°C. The NADH oxidase activity was followed by the absorption decrease at 340 nm assuming ε340=6.22 mM−1 cm−1. Succinate oxidase activity was followed as an absorption increase at 278 nm (fumarate formation) assuming ε278=0.3 mM−1 cm−1; the latter value was determined by the addition of aliquots of sodium fumarate to the suspension of SMP incubated in the standard reaction mixture in the assay cuvette. The quinol oxidase activity was assayed as an absorption increase at 278 nm with 0.02 mM Q1H2 prepared as described [10] assuming ε278=10.2 mM−1 cm−1. Respiration-driven electrogenic activity was estimated as oxonol VI (1.5 μM) response [11] following the absorption change at 624 nm minus 602 nm. Other experimental details are indicated in the legends to the Figures and Table 1. We noted that the quinol oxidase activity of cytochrome bd with Q1H2 as the substrate was low if the reaction was initiated by the addition of the soluble enzyme to the assay mixture (final concentration of N-lauroylsarcosine originated from the stock solution in the assay mixture was no more than 1·10−4 %). The activity gradually increased upon incubation of the diluted protein and reached a maximum (~10 μmol of Q1H2 oxidized per min per mg of protein at 20 μM Q1H2) after about 7 min of preincubation. This activation may be related to the similar behavior of cytochrome bd from Azotobacter vinelandii observed by Jünemann and Rich [12], or more likely, due to a structural rearrangement of the protein caused by detergent dilution. This phenomenon was not further examined, and the quinol oxidase activity assays were measured after 7 min preincubation of the diluted enzyme in the standard assay mixture.

Table 1.

Effects of bd quinol oxidase on energy transduction by coupled SMP

| μmol/min per mg of SMP proteina | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NADH oxidase | − Uncoupler | + Uncouplerb | RCRc |

| 1. SMP (control) | 0.30 | 1.5 | 5.0 |

| 2. SMP + QOd | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.6 |

| 3. As before + 0.5 μM myxothiazol | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

|

| |||

| NADH:Q1-reductasee | |||

| 4. SMP | 0.4 | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| 5. SMP + QOd | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

All the activities were measured in the presence of bovine serum albumin (1 mg/ml) in the standard reaction mixture supplemented by 0.1 mM NADH.

Gramicidin D (0.2 μg/ml); respiration rate measured after addition of uncoupler to the same assay sample as depicted in previous column.

Respiratory control ratio.

The assembled system was prepared as described in Fig. 3; the content of bd quinol oxidase (QO) added to the reconstitution mixture was 0.15 nmol per mg of SMP protein.

The initial rates of 80 μM Q1 reduction were measured in the presence of 0.5 μM myxothiazol.

Protein content was determined by the biuret procedure (SMP) or by the Lowry method (quinol oxidase). All fine chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (U.S.A.).

3. Results

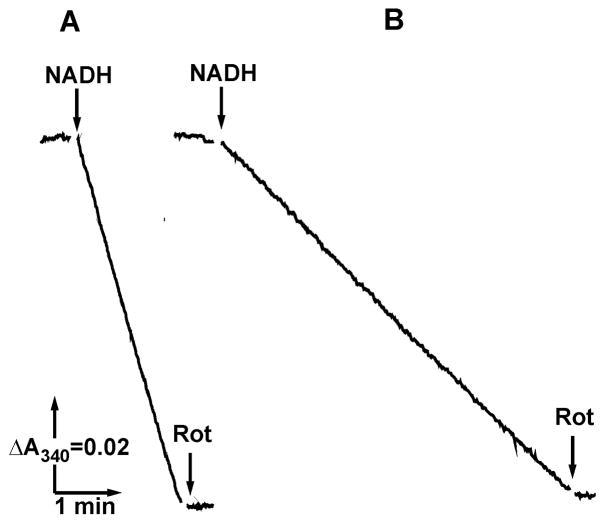

Figure 1 demonstrates the tracings of NADH oxidation by control (A) and myxothiazol-inhibited (B) SMP. When SMP were treated with excess of the complex III inhibitor myxothiazol their uncoupled NADH and succinate oxidase (not shown) activities decreased to less than 1% of the original (1.1±0.3 and 0.8±0.2 μmol per min per mg of SMP protein, at 37°C, respectively) activities. If cytochrome bd quinol oxidase and a limited amount of the water soluble ubiquinol homologue, Q1 were present in the assay mixture (Fig. 1B) the rotenone-sensitive NADH oxidation was restored, as expected.

Fig. 1.

NADH oxidation by complex III-inhibited submitochondrial particles in the presence of the bacterial quinol oxidase and water soluble quinone (Q1). The standard reaction mixture (see Materials and Methods section) was supplemented by gramicidin D (0.1 μg/ml). The SMP protein content in all assays was 5 μg/ml; the final concentrations of other addition were: NADH, 0.1 mM; rotenone (Rot), 5 μM; Q1, 3 μM. (A), control, no myxothiazol and Q1were added; (B), 0.5 μM myxothiazol, 5 μM Q1, and cytochrome bd quinol oxidase (1 μg protein/ml) preincubated in the assay mixture for 7 min were present.

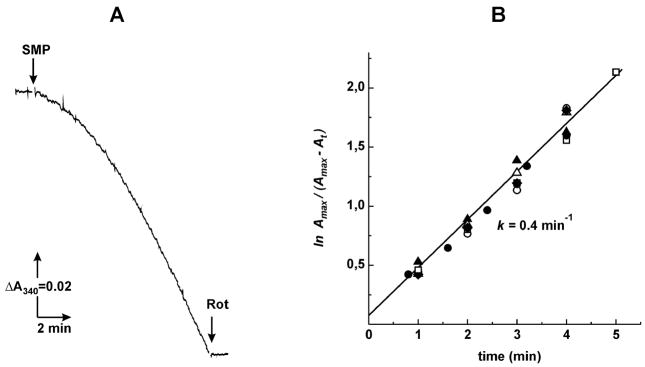

When myxothiazol-treated SMP were added to the assay mixture containing cytochrome bd quinol oxidase of E. coli and no exogenous quinone their rotenone-sensitive NADH oxidase activity gradually increased up to about 50% of the original uninhibited level (Fig. 2A). Neither thermally inactivated quinol oxidase (5 min at 100°C) nor the addition of an equivalent amount of the buffer containing detergent in which the enzyme was solubilized reactivated the myxothiazol-inhibited NADH oxidase. Qualitatively the same phenomenon as shown in Fig. 2A (lag-phase with t1/2 of about 2 min) was seen when the succinate oxidase activity was assayed (not shown). It could be suggested that the bacterial quinol oxidase interacts with the SMP reduced ubiquinol pool by simple collision and if so, the rate of NADH oxidase reactivation would be dependent on both SMP and cytochrome bd content in the assay mixture. This was not the case and the reactivation proceeded as the first-order time course with the rate constant of 0.4 min−1 that was independent of the quinol oxidase amount (Fig. 2B). This behavior is expected if cytochrome bd rapidly binds to SMP and a slow intramolecular rearrangement (conformational change) of the bound enzyme results in formation of a ubiquinol pool-reactive quinol oxidase.

Fig. 2.

The time course of bd quinol oxidase-induced myxothiazol-insensitive NADH oxidase activity of SMP in the absence of added Q1. (A) Quinol oxidase (2.5 μg/ml) was preincubated in the standard reaction mixture for 7 min, myxothiazol (0.5 μM), gramicidin D (0.1 μg/ml) and NADH (0.1 mM) were then added and the reaction was started by the addition of SMP (20 μg/ml). (B) Semilogrithmic plot for the activation process assayed as in (A) in the presence of quinol oxidase: 0.5 (●), 0.75 (○), 1.0 (■), 1.5 (□), 2.0 (▲), and 2.5 (△) μg/ml. Amax and At, the specific activities at t→∞ and particular time t, respectively. The final constant rates of NADH oxidation which were linearly dependent on the amount of quinol oxidase was taken as the specific activity at t→∞.

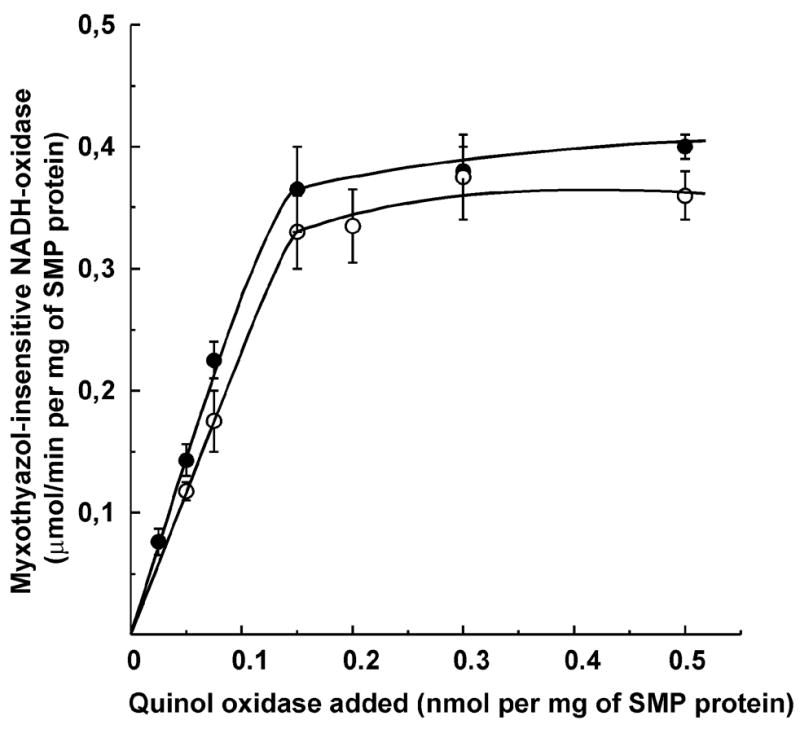

Figure 3 shows the titration of the NADH and succinate oxidase activities by the added quinol oxidase under conditions where the myxothiazol-inhibited SMP and cytochrome bd were admixed in a relatively concentrated preincubation mixture. The activities were then determined after the mixtures were diluted into the assay cuvette. The titration pattern corresponds to the formation of a tight (stoichiometric) complex between SMP and cytochrome bd where the latter serves as an alternative myxothiazol-insensitive quinol oxidase. Both myxothiazol-insensitive NADH and succinate oxidase activities were saturated at a concentration of bd cytochrome in the preincubation mixture of about 0.15 nmol/mg of SMP protein.

Fig. 3.

Myxothiazol-insensitive NADH (●) and succinate (○) oxidase of SMP as a function of quinol oxidase in the assembling mixture. SMP (2 mg/ml) and different amounts of quinol oxidase were incubated in the standard reaction mixture for 7 min at 20°C and the samples were placed in ice. The reactions were initiated by addition of proper amounts of the mixture (20 μg of SMP protein/ml) to the assay medium supplemented by gramicidin D, 0.2 μg/ml; NADH, 0.1 mM, or succinate, 20 mM; myxothiazol, 0.5 μM, and bovine serum albumin, 1 mg/ml. The specific NADH and succinate oxidase activities of SMP in the absence of myxothiazol were 1.0 and 0.9 μmol per min per mg of SMP protein, respectively. When exogenous Q1 (7 μM) or Q2 (3 μM) were added to the mixture for the assays of NADH oxidase or succinate oxidase, respectively, at saturating amount of quinol oxidase (0.3 nmol per mg of SMP protein) both NADH and succinate oxidase activities were increased up to 85 and 90% of the original (with no myxothiazol) level, respectively.

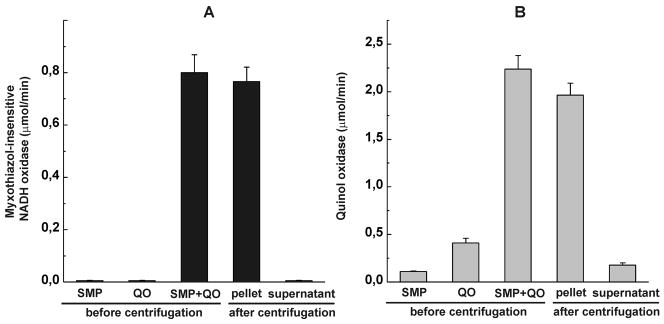

Further support for assembly of a chimeric respiratory chain was obtained when the preincubated mixture of SMP and cytochrome bd was subjected to ultracentrifugation followed by washing (Fig. 4). An increase of the NADH oxidase activity of SMP (panel A) paralleled the appearance of quinol oxidase activity in SMP and the disappearance of enzyme activity from the supernatant (panel B). Interestingly, preincubation of quinol oxidase in the presence of SMP (binding of the soluble enzyme to the mitochondrial membrane) resulted in a 10-fold increase of its Q1H2 oxidase activity (panel B, second and third bars from the left).

Fig. 4.

Binding of the bacterial quinol oxidase to SMP. SMP (2 mg/ml) and quinol oxidase (QO, 30 μg/ml) were preincubated as described in Fig. 3 in 4 ml samples. The samples were subjected to ultracentrifugation and the NADH (A) and Q1H2 (B) oxidase activities were assayed as described in Fig. 3 in the precipitated material (after washing by 8 ml of buffer) and in the supernatants (after first centrifugation). The concentration of Q1H2 in the quinol oxidase activity assays was 20 μM. The activities are expressed in μmol of the substrate oxidized per min per ml of the incubation mixture.

It seemed improbable that true transmembraneous and properly oriented incorporation of cytochrome bd quinol oxidase into inner mitochondrial membrane could be achieved by simple mixing of SMP and bacterial enzyme. Nevertheless we examined the electrogenic activity (Δϕ estimated as oxonol VI response) of cytochrome bd bound to SMP. No response, was detected when 30 μM Q1H2 and 3 mM dithiothreitol were added to oligomycin-treated SMP, whereas a clear response was seen when respiration was initiated by the addition of NADH.

Tightly coupled SMP show significant stimulation of their respiratory activities by uncouplers. It was of interest to see whether chimeric rotenone-sensitive, myxothiazol-insensitive NADH oxidase retains its energy-transducing capacity. Table 1 shows the results of representative experiments on the effects of uncoupler (gramicidin D) on the NADH oxidase and NADH:Q1-reductase activities as influenced by the presence of cytochrome bd quinol oxidase in SMP. When artificial branching pathways of ubiquinol oxidation were induced by the bacterial enzyme (uncoupled ubiquinol oxidation) the respiratory control ratio decreased from 4.9 to 2.6 (samples 1 and 2, respectively). The stimulation of NADH oxidase activity of the complex III-inhibited SMP assembled with the quinol oxidase was lost (sample 3) thus indicating that coupling sites 2 (complex III) and 3 (cytochrome c oxidase) of the mammalian respiratory chain are the major contributors to the respiratory control phenomenon during NADH oxidation. The initial rate of the external Q1 reduction (operation of complex I only) was still stimulated by uncoupler (sample 4), although to a lower degree than the complete respiratory chain activity. In the presence of the bacterial quinol oxidase the respiratory control ratio with external Q1 as the substrate was decreased (sample 5).

4. Discussion

In this manuscript we demonstrate that complex III inhibitor-insensitive NADH (and succinate) oxidase activity can be constructed by simply mixing of mammalian SMP with bacterial cytochrome bd quinol oxidase. The kinetics of the assembly process (Fig. 2) correspond to a model where soluble quinol oxidase rapidly binds to some component(s) of the inner mitochondrial membrane and a relatively slow (k=0.4 min−1) transformation (conformational change) of the bound enzyme into its endogenous Q10-reactive form then occurs resulting in catalytically active NADH (succinate) oxidase. Notably, the incorporation of the enzyme into the membrane is accompanied by large (about 10-fold) increase of its reactivity with exogenously added Q1H2 (Fig. 4).

The assembled system is resistant to strong dilution (Fig. 3) and extensive washing as evidenced by centrifugation (Fig. 4). In other words, the bound bacterial enzyme behaves as any other natural intrinsic component of the respiratory chain. The titration data (Fig. 3) show that complex III inhibitor-insensitive NADH and succinate oxidase activities are saturated at an amount of added quinol oxidase of about 0.15 nmol per mg of SMP protein. This value is very close to that reported for complex I and complex II contents in bovine heart SMP (0.1 and 0.14 nmol per mg of SMP, respectively) [13, 14]. The finding that a foreign protein can complement function of a mitochondrial respiratory chain component is not unique. It has been shown that the yeast Ndi1 enzyme can partially complement for loss of function of complex I in mammalian mitochondria [15, 16]. Recently, uncoupled NADH oxidase activity have been restored in engineered mouse mtDNA-less (ρ0) cells by transforming them with the alternative quinol oxidase (Aox) of the ascomycete Emiricella nidulans and the yeast single subunit NDi1 [17].

Two questions naturally arise: (i) what is the factor(s) that limits binding of foreign proteins to the mitochondrial membrane? and (ii) why the quinol-saturated myxothiazol-insensitive NADH and succinate oxidase activities are still significantly lower (about 50%) than those seen in the natural complex III-operative respiratory chain? Two possibilities relevant to (i) seem feasible. The simplest explanation is that there exists not enough free surface area on the inner mitochondrial membrane to accept foreign hydrophobic proteins and the apparent stoichiometry of binding is just a coincidental phenomenon. More interesting, although a highly speculative proposal is that evolutionary conserved specific protein-protein interactions between some subunits of the mammalian complex I (and/or complex II) or other mitochondrial inner membrane components are responsible for the “stoichiometric” binding of bd cytochrome. This limitation in “proper” Q10-reactive binding may also be an explanation of the lower NADH and succinate oxidase activities of the chimeric respiratory chain as compared to the natural system.

Incorporation of the bacterial enzyme into the native mammalian respiratory chain results in apparent uncoupling (a decrease of RCR, Table 1) presumably, because of at least partial abbreviation of energy transduction at Site 2. When only the alternative quinol oxidase operates in NADH oxidase (in the presence of myxothiazol, Table 1, sample 3), no stimulation by the uncoupler is seen. A plausible explanation for this lies in the limited capacity of the quinol oxidase-mediated NADH oxidation. The rate of proton leakage under these conditions may be comparable with decreased proton translocating activity of complex I. Indeed, when NADH oxidation rate was increased by the addition to the chimeric system of exogenous Q1 (Table 1, sample 5), the stimulation of NADH oxidation, although not high became evident.

The last point to be briefly discussed is the structural arrangement of the bacterial quinol oxidase bound to the mitochondrial membrane. The cytochrome bd complex is one of two terminal proton translocating quinone oxidases in the E. coli aerobic respiratory chain [6, 18]. The enzyme contains two transmembrane subunits (subunit I, 58 kDa, and subunit II, 43 kDa), and two b-type and one d-type heme [19]. Trypsin and chymotrypsin digestion experiments [20, 21], ubiquinone azido homologue photoaffinity labeling [22, 23], and site-directed mutagenesis [24] suggest that the natural Q8H2-reactive site is located near the N-terminal region of subunit I (loops VI/VII) located in the bacterial periplasm [23] and may be exposed to solvent. An amphipathic “ramp” guiding the ubiquinone head group from the membrane domain into its catalytic site located at a substantial distance from the membrane surface has been proposed for the ubiquinone–N2 iron sulfur center interaction in complex I [25]. Such a quinone guiding channel may preexist or be formed by interaction with specific proteins in the bacterial quinol oxidase bound to the mitochondrial membrane.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grants 06-04-48931 to V.G.G., 08-04-00594 to A.D.V., and 08-04-00093 to V.B.B.); NIH Research Grant 5R03 TW007825-02 funded by the Fogarty International Center (A.D.V. and G.C.) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (G.C.). We are grateful to Dr. R.B. Gennis (Urbana, USA) for the strain of E. coli GO105/pTK1.

Abbreviations

- SMP

submitochondrial particles

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kröger A. Determination of contents and redox states of ubiquinone and menaquinone. Meth Enzymol. 1978;53:579–591. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)53059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wan YP, Williams RH, Folkers K, Leung KH, Racker E. Low molecular weight analogs of coenzyme Q as hydrogen acceptors and donors in systems of the respiratory chain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;63:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(75)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grivennikova VG, Vinogradov AD. Kinetics of ubiquinone reduction by the resolved succinate: ubiquinone reductase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;682:491–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(82)90065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maklashina E, Cecchini G. Comparison of catalytic activity and inhibitors of quinone reactions of succinate dehydrogenase (Succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase) and fumarate reductase (Menaquinol-fumarate oxidoreductase) from Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;369:223–232. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinogradov AD. Catalytic properties of the mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I) and the pseudo-reversible active/inactive enzyme transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1364:169–185. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anraku Y, Gennis RB. The aerobic respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. Trends Biochem Sci. 1987;12:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotlyar AB, Vinogradov AD. Slow active/inactive transition of the mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone reductase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1019:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90137-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burbaev DSh, Moroz IA, Kotlyar AB, Sled VD, Vinogradov AD. Ubisemiquinone in the NADH-ubiquinone reductase region of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. FEBS Lett. 1989;254:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borisov VB. Interaction of bd-type quinol oxidase from Escherichia coli and carbon monoxide: Heme d binds CO with high affinity. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2008;73:14–22. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908010021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rieske JS. Preparation and properties of reduced coenzyme Q-cytochrome c reductase (complex III of the respiratory chain) Meth Enzymol. 1967;10:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waggoner AS. The use of cyanine dyes for the determination of membrane potential in cells, organelles, and vesicles. Meth Enzymol. 1979;55:689–695. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)55077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jünemann S, Rich PR. Does the cytochrome bd terminal oxidase complex have a “pulsed” form? Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:400S. doi: 10.1042/bst024400s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinogradov AD, King TE. The Keilin-Hartree heart muscle preparation. Meth Enzymol. 1979;55:118–127. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)55017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grivennikova VG, Kotlyar AB, Karliner JS, Cecchini G, Vinogradov AD. Redox-dependent change of nucleotide affinity to the active site of the mammalian complex I. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10971–10978. doi: 10.1021/bi7009822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Flotte TR, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. In vivo complementation of complex I by the yeast Ndi1 enzyme. Possible application for treatment of Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14250–14255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marella M, Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Greenamyre JT, Mastsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Protection by the NDI1 gene against neurodegeneration in a rotenone rat model of Parkinson disease. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perales-Clemente E, Bayona-Bafaluy MP, Pérez-Martos A, Barrientos A, Fernández-Silva P, Enriquez JA. Restoration of electron transport without proton pumping in mammalian mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18735–18739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810518105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borisov VB, Verkhovsky MI. Chapter 3.2.7, Oxygen as acceptor. In: Böck A, Curtiss R III, Kaper JB, Neidhardt FC, Nyström T, Rudd KE, Squires CL, editors. EcoSal–Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2009. [Online.] http://www.ecosal.org. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller MJ, Gennis RB. The purification and characterization of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of the Escherichia coli aerobic respiratory chain. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9159–9165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorence RM, Carter K, Gennis RB, Matsushita K, Kaback HR. Trypsin proteolysis of the cytochrome d complex of Escherichia coli selectively inhibits ubiquinol oxidase activity while not affecting N, N, N′, N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine oxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5271–5276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dueweke TJ, Gennis RB. Proteolysis of the cytochrome d complex with trypsin and chymotrypsin localizes a quinol oxidase domain. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3401–3406. doi: 10.1021/bi00228a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang FD, Yu L, Yu CA, Lorence RM, Gennis RB. Use of an azido-ubiquinone derivative to identify subunit I as the ubiquinol binding site of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:14987–14990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto Y, Murai M, Fujita D, Sakamoto K, Miyoshi H, Yoshida M, Mogi T. Mass spectrometric analysis of the ubiquinol-binding site in cytochrome bd from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1905–1912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mogi T, Akimoto S, Endou S, Watanabe-Nakayama T, Mizuochi-Asai E, Miyoshi H. Probing the ubiquinol-binding site in cytochrome bd by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7924–7930. doi: 10.1021/bi060192w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandt U, Kerscher S, Dröse S, Zwicker K, Zickermann V. Proton pumping by NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase. A redox driven conformational change mechanism? FEBS Lett. 2003;545:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]