Summary

Telomere dysfunction and shortening induce chromosomal instability and tumorigenesis. In this study, we analyze the adrenocortical dysplasia (acd) mouse, harboring a mutation in Tpp1/Acd. Additional loss of p53 dramatically rescues the acd phenotype in an organ-specific manner, including skin hyperpigmentation and adrenal morphology, but not germ cell atrophy. Survival to weaning age is significantly increased in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice. On the contrary p53−/− and p53+/− mice with the Acdacd/acd genotype show a decreased tumor free survival compared to Acd+/+ mice. Tumors from Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice show a striking switch from the classical spectrum of p53−/− mice towards carcinomas. The acd mouse model provides further support for an in vivo role of telomere deprotection in tumorigenesis.

Significance

Critically shortened dysfunctional telomeres of the Terc−/− mice have been shown to impact tissue development and maintenance and lead to the occurrence of a pro-cancer genome. The present study examines the contribution of telomere shortening vs. telomere deprotection to the development of genetic instability and cancer. By studying the acd mouse, we show that telomere deprotection without significant telomere shortening is sufficient to induce tumor formation in the context of p53 absence. It also raises the possibility that telomere deprotection contributes to the high prevalence of carcinomas in humans.

Introduction

Telomere dysfunction has been shown to interfere with tissue maintenance and to induce chromosomal rearrangements which can provide the genetic basis for malignant transformation (Artandi, 2002; Blasco, 2005).

Telomeres, the outer ends of chromosomes, consist of stretches of hexameric repeats. Over multiple cell cycles telomeres are shortened due to the inability of the semi-conservative DNA replication to completely synthesize the 3′ end of linear chromosomes, which is also known as the end-replication problem. In some tissues and cancers, this problem is overcome by the activity of telomerase, a ribonucleoprotein that adds telomeric repeats to the 3′ end of the leading strand (reviewed by (Greider, 1996)).

Normal telomeres are protected through a specialized DNA structure (T-loop) and a set of protein factors, termed the shelterin complex, which prevents the chromosome ends from causing activation of the DNA damage surveillance and repair machinery, as well as regulating telomerase access (de Lange, 2005). While some parts of the shelterin complex directly bind to either double-stranded (TRF1, TRF2) or single-stranded (POT1) telomere repeats, TIN2, RAP1 and TPP1/ACD serve as critical interconnectors of the shelterin complex. TPP1/ACD (originally termed PTOP, TINT1 and PIP1) was first described as an integral part of the shelterin complex that binds to POT1 and TIN2 (Houghtaling et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2004). We and others have since shown TPP1/Acd to be necessary for the recruitment of POT1 to the telomere and moreover that it is required for the telomere protective and length regulatory function of POT1 (Hockemeyer et al., 2007; Xin et al., 2007).

Concurrent with the cloning of human TPP1/ACD, we had identified a recessive mutation (Acdacd) in the mouse ortholog of the gene encoding TPP1 as the genetic cause of the adrenocortical dysplasia (acd) phenotype, hence termed Acd (Keegan et al., 2005). The acd phenotype displays a significant overlap with late generation Terc−/− and Tert−/− mice (Lee et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2000; Rudolph et al., 1999). Both are infertile due to severely reduced spermatogenesis and have a reduced body size. In addition, the acd mouse is characterized by skin hyperpigmentation, patchy or absent fur growth, abnormal morphology of the adrenal cortex with large pleomorphic nuclei, skeletal abnormalities and hydronephrosis (Beamer et al., 1994; Keegan et al., 2005).

Most of our current knowledge about the consequences of telomere dysfunction stems from analysis of the phenotype of the Terc−/− mouse, which lacks the telomerase RNA component. The phenotype of Terc−/− mice is believed to be due to a progressive shortening of telomeres over consecutive generations of Terc−/− homozygous breedings and over the lifetime of the Terc−/− organism (Blasco et al., 1997; Chin et al., 1999; Hande et al., 1999; Rudolph et al., 1999). With continued telomere shortening, cells from Terc−/− mice exhibit cytogenetic abnormalities, including chromosomal fusions, presumably due to the ligation of unprotected telomeres by the DNA repair machinery. Similar observations have been made in cell culture models of telomere deprotection such as overexpression of a dominant negative isoform of TRF2 (van Steensel et al., 1998).

In contrast, the acd phenotype manifests within the first generation of Acdacd/acd mice generated by heterozygous matings (Beamer et al., 1994; Keegan et al., 2005). The telomere deprotection phenotype in cells lacking TPP1/Acd has been well described. The acute reduction of TPP1 levels in human cells induces telomere dysfunction-induced foci (TIFs) and telomere elongation (Guo et al., 2007; Hockemeyer et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2004). Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) from acd mice with a severe deficiency of Tpp1/Acd show a telomere deprotection phenotype and a moderate increase in genomic alterations such as chromosome fusions (Else et al., 2007; Hockemeyer et al., 2007). The acute loss of Tpp1/Acd in wt MEFs strongly induces a DNA damage response inducing senescence through a p53-sensitive pathway (Guo et al., 2007; Hockemeyer et al., 2007; Xin et al., 2007).

Telomere dysfunction of Terc−/− mice leads to the accumulation of genomic alterations and the development of tumors (Chin et al., 1999). Cells harboring critically short telomeres are usually removed from the pool of proliferating cells by p53-dependent pathways leading to apoptosis or senescence in mice and/or additional p16/Ink4a-sensitive pathways in humans (Jacobs and de Lange, 2004; Smogorzewska and de Lange, 2002). In accordance with this finding, Terc−/− p53−/− exhibit a partial reversal of their infertility due to germ cell failure at the expense of an increased tumor incidence (Artandi et al., 2000; Chin et al., 1999).

With the exception of the Pot1b−/− mouse, attempts to create deletions of components of the shelterin complex in whole murine organisms have led to phenotypes with early embryonic lethality (Celli and de Lange, 2005; Chiang et al., 2004; Hockemeyer et al., 2006; Karlseder et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006). The Acdacd/acd genotype that results in a viable mouse despite severe Tpp1/Acd deficiency presents a unique opportunity to investigate the in vivo effects of direct telomere deprotection without telomere shortening (Else et al., 2007; Hockemeyer et al., 2007). In order to study the in vivo consequences of telomere dysfunction in the absence of telomere shortening, we crossed Acdacd/acd mice to a p53−/− background and analyzed the surviving offspring for both the rescue of organ phenotypes and the emergence of cancer.

Results

Organ specific rescue of the acd phenotype by p53 ablation

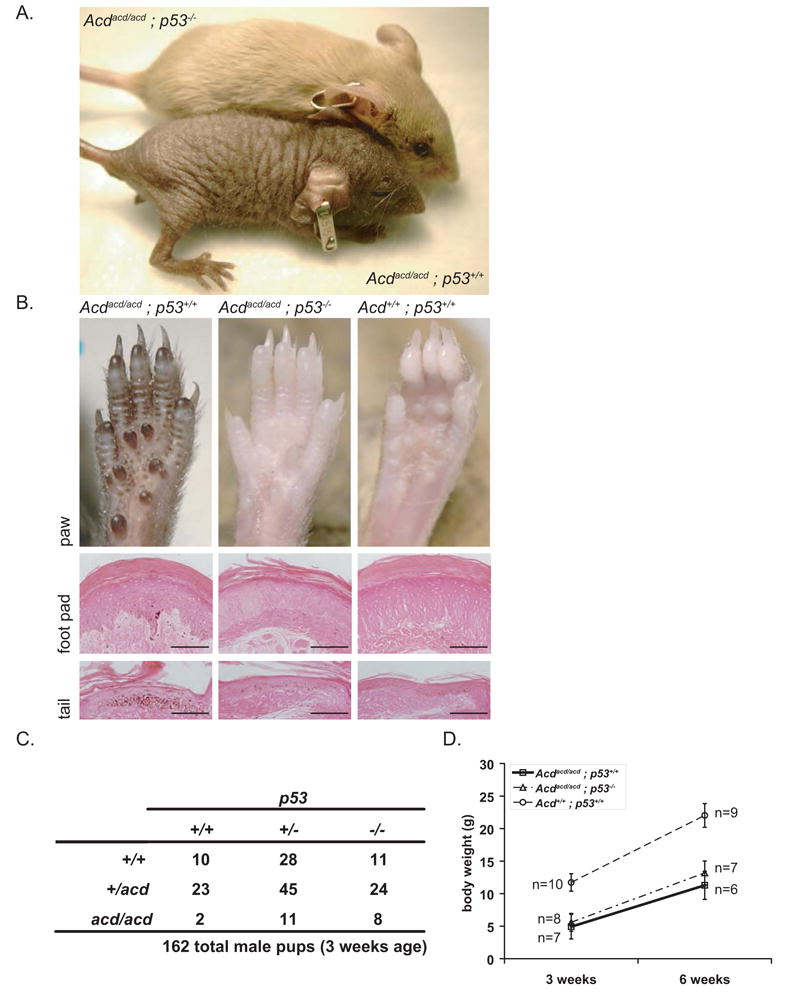

Because the acd phenotype is predicted to be induced by telomere dysfunction resulting in activation of p53-sensitive signaling pathways, we crossed Acdacd/acd mice to a p53−/− background. On macroscopic examination, a striking complete normalization of the characteristic acd phenotype of patchy or complete lack of fur and hyperpigmentation was evident in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice (Fig. 1A, Suppl. Fig. 1A). Although the fur and skin phenotype of acd mice varied significantly between individual animals, hyperpigmentation in acd mice is always present in the skin overlying the paw pads, ears, tail and the ano-genital region. In Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice, macroscopic hyperpigmentation was completely abolished and there was a dramatic reduction of pigment in epidermis and dermis (Fig. 1B, Suppl. Fig. 1B). Hyperpigmentation in acd mice not only led to a darker skin color but was also evident in skin associated lymph nodes presumably due to the uptake and lymphatic transport by macrophages (Suppl. Fig. 4). These dark lymph nodes were not present in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice (data not shown).

Figure 1. p53 ablation reverses the macroscopic appearance of adrenocortical dysplasia mice and increases perinatal survival.

(A) The macroscopic hyperpigmentation and fur phenotype of Acdacd/acd mice were completely rescued by p53 ablation. Macroscopic appearance of 6 week old mice: Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice shown on top of the picture showed normal fur growth and completely lacked hyperpigmentation. As a comparison an Acdacd/acd p53+/+ mouse is shown below.

(B) Hyperpigmentation is always present on the footpads of adrenocortical dysplasia mice. In Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice the hyperpigmentation completely disappeared at the macroscopic level. Eosin-stained sections showed a striking reduction of pigment in the epidermis and dermis of Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice. The same results are shown for tail skin sections (scale bars for foot pads 200μm, for tails 100μm).

(C) Genotype analysis of 162 male pups at weaning age shows an increased survival for Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice. Acdacd/acd mice with either the p53+/− or the p53+/+ genotype were not observed in the expected ratio (p=0.03 and p=0.03 as compared to p=0.6 for p53−/−, Chi-square test).

(D) Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice are still smaller than their Acd+/+ p53+/+ littermates (p<10−7). Body weight did not differ from Acdacd/acd p53+/+ mice (p=0.4 at 3 weeks and p=0.1 at 6 weeks, 1-way ANOVA and F-test, data shown as mean +/− SD). Post-weaning weight gain was comparable in both Acdacd/acd groups to their wt littermates..

We analyzed the genotype of 162 male pups resulting from double heterozygous matings (Acd+/acd p53+/− x Acd+/acd p53+/−) at weaning age (21 days). For p53+/+ as well as p53+/− offspring, a significantly lower number of Acdacd/acd genotypes were observed than were expected (p=0.03 and p=0.03, Chi-square test), whereas for p53−/− offspring, the Acdacd/acd genotypes were nearly in the expected Mendelian proportions (p=0.6), indicating that p53−/− increases survival of the Acdacd/acd genotype (Fig. 1C). Like Acdacd/acd p53+/+, Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice were significantly smaller than their respective Acd+/+ littermates at weaning age (3 weeks) and at 6 weeks of age (p<10−7) (Fig. 1D).

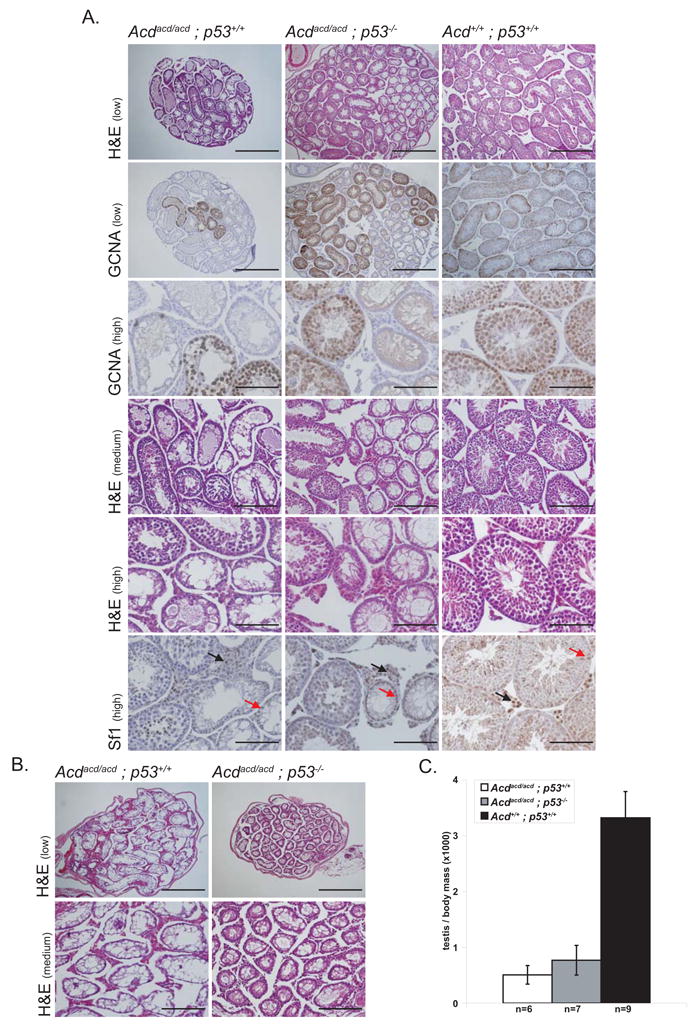

Testes of both, Acdacd/acd and late generation Terc−/− mice, show similar germ cell failure (Hemann et al., 2001; Keegan et al., 2005; Lee et al., 1998). Therefore we examined whether the observed spermatogenic defect involved p53 signaling. In contrast to the observation of a moderate genetic rescue of spermatogenesis in Terc−/− p53−/− mice and the striking rescue of the skin phenotype in Acdacd/acd p53−/−, we did not find any rescue of the testicular acd phenotype in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice (Fig. 2A) (Chin et al., 1999). Testes of Acdacd/acd mice of all p53 genotypes either completely lacked (Fig. 2B) or displayed severely reduced spermatogenesis (Fig. 2A) with testis histology reminiscent of a Sertoli cell-only syndrome (SCOS). Total absence of germ cells in tubules without spermatogenesis was confirmed by Gcna immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2A) (Enders and May, 1994). However, in some animals we observed areas of seminiferous tubules with normal spermatogenesis adjacent to empty seminiferous tubules, completely devoid of germ cells. Relative testicular weights were lower in Acdacd/acd animals regardless of their genetic p53 status when compared to their Acd+/+ littermates (Fig. 2C). Due to the infertility phenotype, male and female mice were regularly housed together and only on very rare occasions did we observe successful pregnancies. Because some components of the adult testis, specifically the Leydig cells, share a common developmental lineage and steroidogenic function with adrenocortical cells, we next examined morphology and characteristics of these interstitial testicular cells (Else and Hammer, 2005). The Leydig and Sertoli cell populations were morphologically normal as evidenced by histologic analysis and Sf1 staining, a marker specific for these cell populations in the testis (Fig. 2A) (Luo et al., 1995). The data indicate that, unlike the spermatogenic defect in Terc−/− mice, the germ cell failure of Acdacd/acd mice may not be caused by p53-mediated senescence or apoptosis and suggests that the Acdacd/acd decapping phenotype may not be identical to a short telomere phenotype or may be of a different degree of severity.

Figure 2. Loss of p53 does not rescue spermatogenesis in Acdacd/acd testes. Testes of Acdacd/acd mice display focal or complete absence of germinal epithelia reminiscent of Sertoli-cell-only syndrome regardless of their genetic p53 status.

(A) Testes of Acdacd/acd p53+/+ as well as Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice show focal spermatogenesis. Seminiferous tubules with an intact germinal cell epithelium harbored Gcna-positive germ cells. The Sf1-positive interstitial Leydig (black arrows) and Sertoli cell (red arrows) populations did not appear altered in either genotype compared to Acd+/+ p53+/+ littermates (scale bars for different levels of magnification: high 100μm, medium 200μm, low 400μm).

(B) Some Acdacd/acd p53+/+ and Acdacd/acd p53−/− testes completely lack spermatogenesis and germ cells. Only empty seminiferous tubules were present in these testes (scale bars for different levels of magnification: medium 200μm, low 400μm).

(C) Testis weight relative to body weight is severely reduced in both Acdacd/acd p53+/+ and Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice and therefore independent of their genetic p53 status (Acd+/+ p53+/+ vs. Acdacd/acd p53−/− p=1×10−11, Acd+/+ p53+/+ vs. Acdacd/acd p53+/+ p=4×10−12, Acdacd/acd p53+/+ vs. Acdacd/acd p53−/−, p=0.19, 1-way ANOVA and F-test, data shown as mean +/− SD)

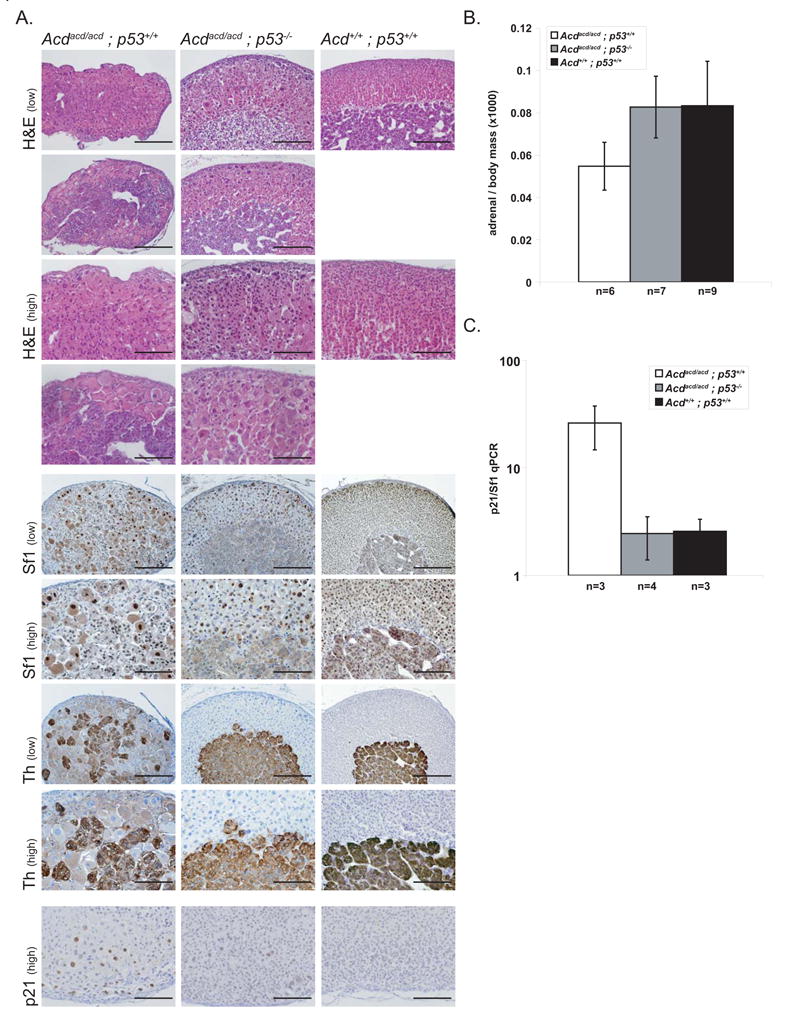

Absence of p53 partially normalizes the adrenocortical phenotype

The main feature of the acd phenotype which led to its name, is the characteristic dysmorphic small adrenal cortex (Beamer et al., 1994). In acd adrenal glands there was variable intermingling of the normally distinct adrenal cortex and adrenal medulla, and a lack of the physiological concentric zonation of the mammalian adrenal cortex. Adrenocortical cells of acd animals displayed large eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent enlarged pleomorphic nuclei sometimes harboring inclusion bodies. Remarkably, relative adrenal organ size was completely rescued in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice and an obvious albeit partial normalization of organ architecture with areas of a distinct cortical zonation was observed (Fig. 3A & 3B). Moreover, while some areas of nuclear atypia remained, Acdacd/acd p53−/− adrenal cortices exhibited a partial rescue in cellular and nuclear size as well (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Adrenocortical architecture, weight and p21 expression is normalized in adrenal cortex of Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice.

(A) The adrenal cortex of Acdacd/acd mice appears highly disorganized and consists of scattered cells with a high grade of nuclear pleomorphy. This phenotype was partially rescued in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice, where adrenal glands appeared more clearly zonated and organized, while increased nuclear size and pleomorphy partially persisted. This became obvious using differentiation markers for the adrenal cortex (Sf1, steroidogenic factor 1) and for the adrenal medulla (Th, tyrosine hydroxylase). Two examples of adrenal glands from Acdacd/acd p53+/+ and Acdacd/acd p53−/− and, as a comparison, one wt (Acd+/+ p53+/+) adrenal, are shown. Acdacd/acd p53+/+ adrenal cortices stained positive for p21, a downstream mediator of p53-mediated senescence induction (scale bars for different levels of magnification: high 100μm, low 200μm).

(B) Relative adrenal gland weight is normalized in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice. Adrenal glands from Acdacd/acd p53+/+ animals were about 66% the relative weight of Acd+/+ p53+/+ adrenal glands (Acdacd/acd p53+/+ vs. Acd+/+ p53+/+ p=0.008, Acdacd/acd p53+/+ vs. Acdacd/acd p53−/− p=0.005, Acdacd/acd p53−/− vs. Acdacd/acd p53+/+ p=0.95, 1-way ANOVA and F-test, data shown as mean +/− SD).

(C) In Acdacd/acd p53+/+ mice telomere deprotection induces p21 expression as a marker of senescence. Ablation of p53 strikingly reduced p21 expression (Acdacd/acd p53+/+ vs. Acd+/+ p53+/+ p=0.02, Acdacd/acd p53+/+ vs. Acdacd/acd p53−/− p=0.03, Acdacd/acd p53−/− vs. Acd+/+ p53+/+ p=0.99, 1-way ANOVA and F-test, data shown as mean +/− SD).

As telomere dysfunction in general and loss of Tpp1/Acd in particular is known to activate p53 signaling leading to cellular senescence, we examined whether p53-mediated cellular senescence contributed to the adrenal phenotype observed in Acdacd/acd mice. While many adrenocortical cells in Acdacd/acd p53+/+ mice stained positive for senescence associated β-galactosidase, a reduced number of stained cells was observed in Acdacd/acd p53−/− adrenal cortices (Suppl. Fig. 2). Consistent with this observation was a reduction of p21 gene expression (as determined by quantitative RT-PCR analysis) and a reduction in p21 protein (as determined by immunohistochemical analysis) in whole adrenal glands of Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice in comparison to Acdacd/acd p53+/+ mice (Fig. 3A & 3C). Caspase 3 and TUNEL staining was typically only observed in Acd+/+ p53+/+ mice at the corticomedullary boundary, where physiologic apoptosis normally occurs (data not shown). Specifically, there was no increase in cell number or intensity of cells that were positive for apoptotic markers in Acdacd/acd cortices. The changes in senescence associated β-galactosidase activity and in p21 expression levels as well as the absence of positive markers of apoptosis strongly argue for p53-dependent senescence induction as a main mechanism leading to the adrenocortical phenotype of Acdacd/acd p53+/+ mice.

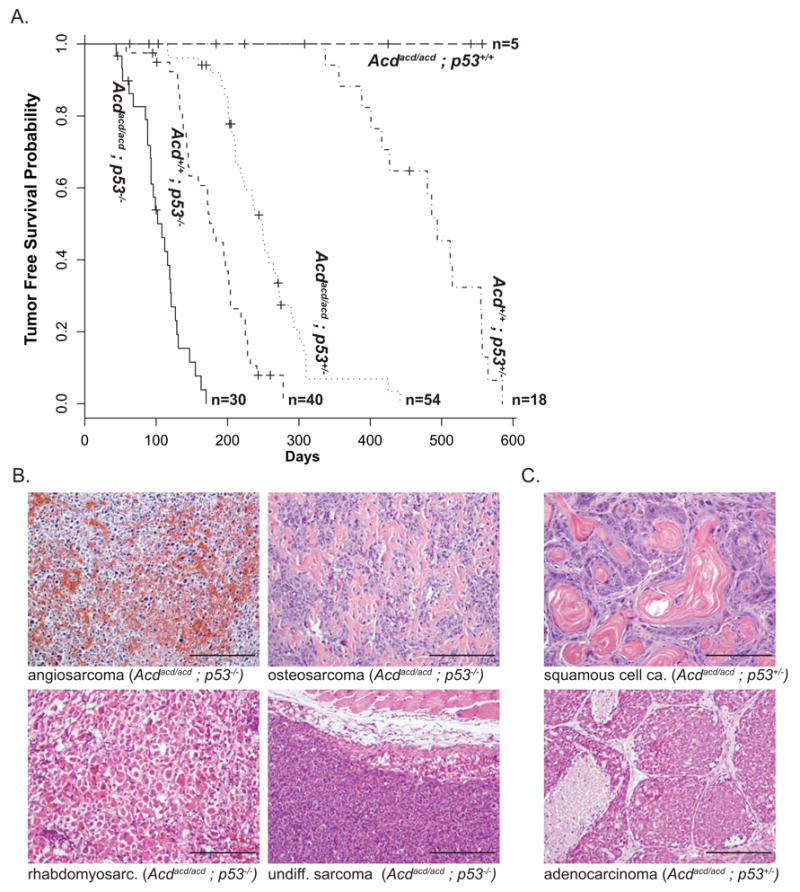

The Acdacd/acd genotype accelerates tumorigenisis in p53−/− mice

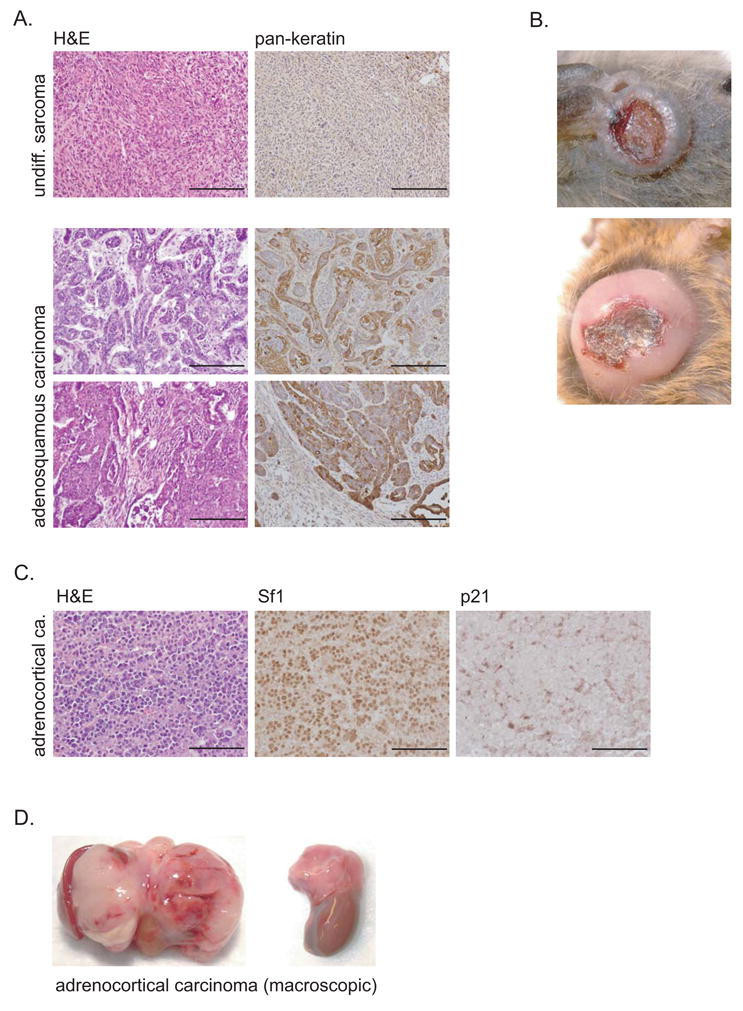

In Terc−/− mice, tumors can be observed at old age even without additional genetic challenge. Although we followed a relatively small cohort (5 animals) of Acdacd/acd p53+/+, we never observed tumors in either this specific aging cohort or in any other animal of this genotype in our colony (survival 386±78 days, average mean±SD). The cause of death could not be determined in these mice, but the majority suffered from severe uni- or bilateral hydronephrosis (Suppl. Fig. 3). Therefore, to investigate whether the accumulation of genomic alterations leads to increased tumorigenesis a set of four animal groups with the p53−/− or p53+/− genotype and either Acdacd/acd or Acd+/+ were analyzed for tumor development. Tumor free survival of Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice was approximately half of that observed in Acd+/+ p53−/− mice (p=2×10−11) (Fig. 4A). Macroscopic and histomorphological analysis of both genotypes identified a tumor spectrum comparable to previous studies of p53−/− and Terc −/− p53−/− mice. Most of the neoplastic lesions belonged to the lymphoma (46% in Acd+/+ p53−/−, 38% in Acdacd/acd p53−/−) or sarcoma (44% in Acd+/+ p53−/−, 47% in Acdacd/acd p53−/−) spectrum (Fig. 4B, Table 1, Suppl. Fig. 4) (Donehower et al., 1992; Jacks et al., 1994). A sub-analysis of tumor types of the sarcoma spectrum revealed angiosarcomas as the dominant tumor type in both groups followed by undifferentiated sarcomas and rhabdomyosarcomas in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice and fibrosarcomas in Acd+/+ p53−/− mice. Interestingly, two tumors (6%) of the carcinoma spectrum were observed in the Acdacd/acd p53−/− but none in the Acd+/+ p53−/− group (Table 1).

Figure 4. The Acdacd/acd genotype severely reduces tumor free survival in p53−/− and p53+/− mice.

(A) Tumor free survival is shown for the different genotype cohorts as a Kaplan-Meier plot. On average in both groups, p53−/− and p53+/−, mice with the Acdacd/acd genotype developed tumors in approximately half the amount of time compared to their Acd+/+ littermates (Acdacd/acd p53−/− vs. Acd+/+ p53−/− p=2×10−11 and Acdacd/acd vs. p53+/− Acd+/+ p53+/− p=2×10−9, log-rank test). In contrast none of the Acdacd/acd p53+/+ developed any tumors.

(B) The main categories of solid tumors in Acdacd/acd p53−/− and Acd+/+ p53−/− are of the sarcoma spectrum (examples of angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma are shown, scale bars 200μm)).

(C) In Acdacd/acd p53+/−, but not Acd+/+ p53+/−, mainly carcinomas arose with a varying degree of squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma differentiation (scale bars 200μm).

Table 1. Distribution of tumor types in the different genotypes.

Animals were autopsied at the time of either spontaneous death or visible tumor growth. Tumors from Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice had an overall higher occurrence of tumors of the carcinoma spectrum (p=1×10−14, 2-sided Fisher’s Exact test). Carcinomas and sarcomas are broken down in distinct tumor diagnosis. Most of the Acdacd/acd p53+/− tumors were of a squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma differentiation type. All other tumor types fell into the typical spectrum of p53−/− tumors (i.e., sarcomas and lymphomas).

| acd/acd; p53−/− | +/+; p53−/− | acd/acd; p53+/− | +/+; p53+/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sarcoma | 16 (47%) | 18 (44%) | 11 (26%) | 9 (50%) |

| angiosarcoma | 7 (21%) | 12 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 (9%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| osteosarcoma | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (10%) | 6 (33%) |

| MFH | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| fibrosarcoma | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) |

| chondrosarcoma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| undiff. sarcoma | 3 (9%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (10%) | 2 (11%) |

| carcinoma | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (64%) | 1 (6%) |

| adenocarcinoma | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (19%) | 0 (0%) |

| adenosquamous ca. | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (14%) | 0 (0%) |

| SCC | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (17%) | 1 (6%) |

| HCC | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| ACC | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| undiff. carcinoma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| lymphoma | 13 (38%) | 19 (46%) | 3 (7%) | 7 (39%) |

| Germ cell | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) |

| Brain | 1 (3%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| undiff./not class. | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 34 (100%) | 41 (100%) | 42 (100%) | 18 (100%) |

Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice predominantly develop tumors of the carcinoma spectrum

As in the p53−/− groups, tumor risk was approximately doubled in Acdacd/acd p53+/− compared to Acd+/+ p53+/− mice (p=2×10−9) (Fig. 4A). Paralleling the reports for Terc−/− mice, we observed a remarkable difference in histological tumor types between these animal groups (Artandi et al., 2000). The main tumor type observed in Acd+/+ p53+/− mice was sarcoma, with a preponderance of osteosarcomas. However the majority of neoplasms in Acdacd/acd p53+/− animals were carcinomas, varying from squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) to adenocarcinomas with a large fraction exhibiting adenosquamous differentiation (Fig. 4C, Fig. 5A, Table 1). The majority of these tumors identified by routine histological analyses also stained positive for pankeratin confirming the diagnosis of carcinoma-type tumors (Fig. 5A). Most carcinomas grew as subcutaneous lesions attached to the cutis and frequently presented with ulcerations, suggestive of an epidermal origin (Fig. 5B). While some of the SCCs appeared to directly arise from the epidermis, the adeno- and adenosquamous carcinomas may have their origin in epidermis-associated glands such as sweat or mammary glands. Most interestingly, 5% of tumors were of adrenocortical origin as proven by positive Sf1 staining (Fig. 5C, Fig. 5D, Table 1). None of these adrenocortical cancers (ACC) stained positive for p21 (Fig. 5C) as shown for the normal acd adrenal cortex (Fig. 3A). This is further evidence that these tumor cells bypassed the senescent phenotype at some point in the process of neoplastic transformation. Finally, at least 11 of 16 tumors from Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice showed apparent loss of the wt p53 allele, whereas at most 4 of 14 tumors from Acd+/+ p53+/− mice showed a similar loss (Suppl. Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice predominantly develop carcinomas.

(A) Some Acdacd/acd p53+/− carcinomas show an intermediate adenosquamous differentiation type with elements of squamous cell as well adenocarcinoma-like elements. Skin associated carcinomas stained highly positive for pankeratin (scale bars 200μm).

(B) Most carcinomas arise in the cutaneous or subcutaneous regions and typically show central necrosis.

(C) 5% of Acdacd/acd p53+/− develop adrenocortical cancers. Their origin could readily be identified by positive Sf1 staining. Adrenocortical cancers were p21 negative indicating that they evaded senescence (scale bars 100μm).

(D) Macroscopically, adrenocortical cancer expanded within the peritoneal cavity adhering to adjacent organs. Two examples of ACC from Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice are shown.

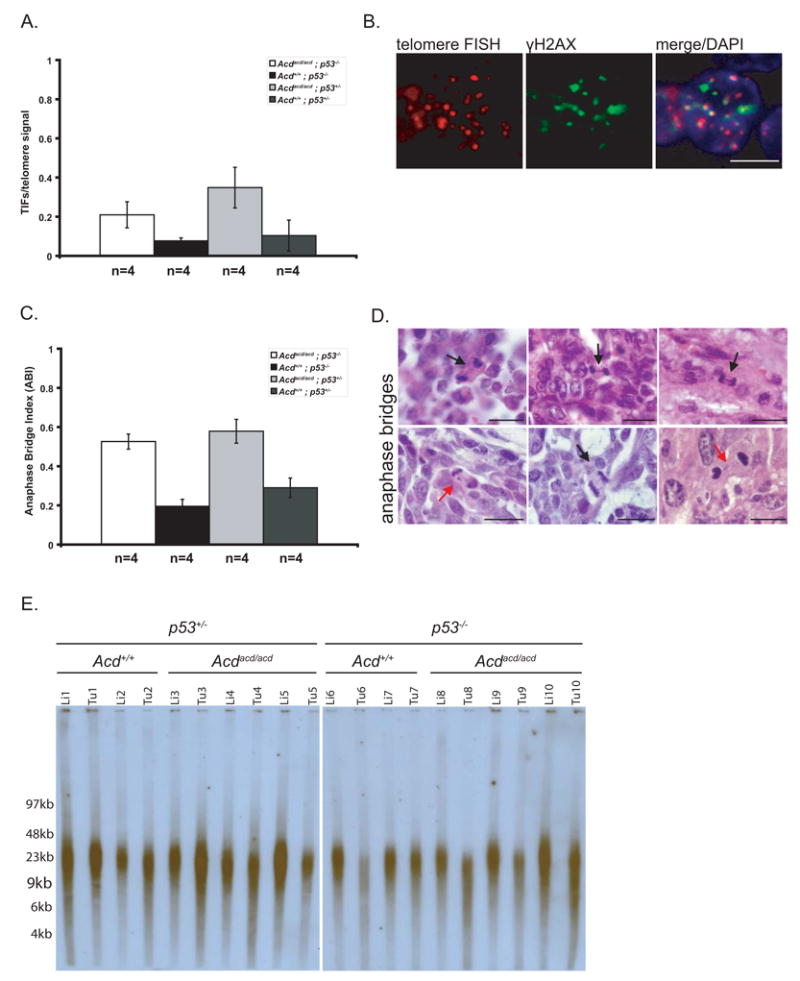

Genomic alterations underlying tumorigenesis in Acdacd/acd mice are the consequence of dysfunctional telomeres and subsequent breakage fusion bridge cycles

Cells derived from Acdacd/acd animals display deprotected telomeres and acquire genomic aberrations (Else et al., 2007; Hockemeyer et al., 2007). Tumors from Acdacd/acd p53−/− showed a significant higher number of TIFs (Fig. 6A, Fig. 6B). As further evidence for dysfunctional telomeres as the underlying mechanism of tumorigenesis, we observed a significantly higher percentage of anaphase bridges in tissue sections from tumors of Acdacd/acd animals (Fig. 6C). Some of the mitotic figures with anaphase bridges revealed multiple strings of chromatin spanning the two poles of the dividing cells and in some cases, genomic material seemed to be localized or trapped between the two dividing poles, lacking a clear connection to either side (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. Tumors from Acdacd/acd mice exhibit hallmarks of genomic instability in the absence of significant telomere shortening.

(A) Acdacd/acd tumors had significantly more telomere dysfunction induced foci (TIFs) per total telomere signals than Acd+/+ tumors indicating that telomere decapping is evident in these neoplasms (p=0.047 for Acdacd/acd p53−/− vs. Acd+/+ p53−/− tumors and p=0.002 for Acdacd/acd p53+/− vs. Acd+/+ p53+/− tumors, 1-way ANOVA and F-test, data shown as mean +/− SD).

(B) Decapped telomeres recruit factors of the DNA surveillance machinery, such as γH2ax and form TIFs. TIFs, the classical co-localization of telomere FISH signal (red) and γH2ax immunohistochemistry (green), were observed in Acdacd/acd tumors (scale bars 5μm).

(C) Tumors from Acdacd/acd mice (p53−/− or p53+/−) have a significantly increased anaphase bridge index (Acdacd/acd p53−/− vs. Acd+/+ p53−/− p=5×10−5 and Acdacd/acd vs. p53+/− Acd+/+ p53+/− p=0.001, 1-way ANOVA and F-test, data shown as mean +/− SD).

(D) Classical anaphase bridges, a morphological correlate of breakage-fusion-bridge cycles (BFBs), are present in tumors from Acdacd/acd mice (black arrows). In some instances chromosomal material (red arrows) appeared in between the two poles without a clear connection to either of the poles of the emerging daughter cells (scale bars 20μm).

(E) Telomere length as measured by TRF gel analysis. No clear differences between normal tissues (liver) of different genotypes were observed. The Acdacd/acd genotype itself did not lead to in vivo telomere length alteration in normal tissues. Some Acdacd/acd as well as Acd+/+ tumors showed a moderate shortening of telomere length.

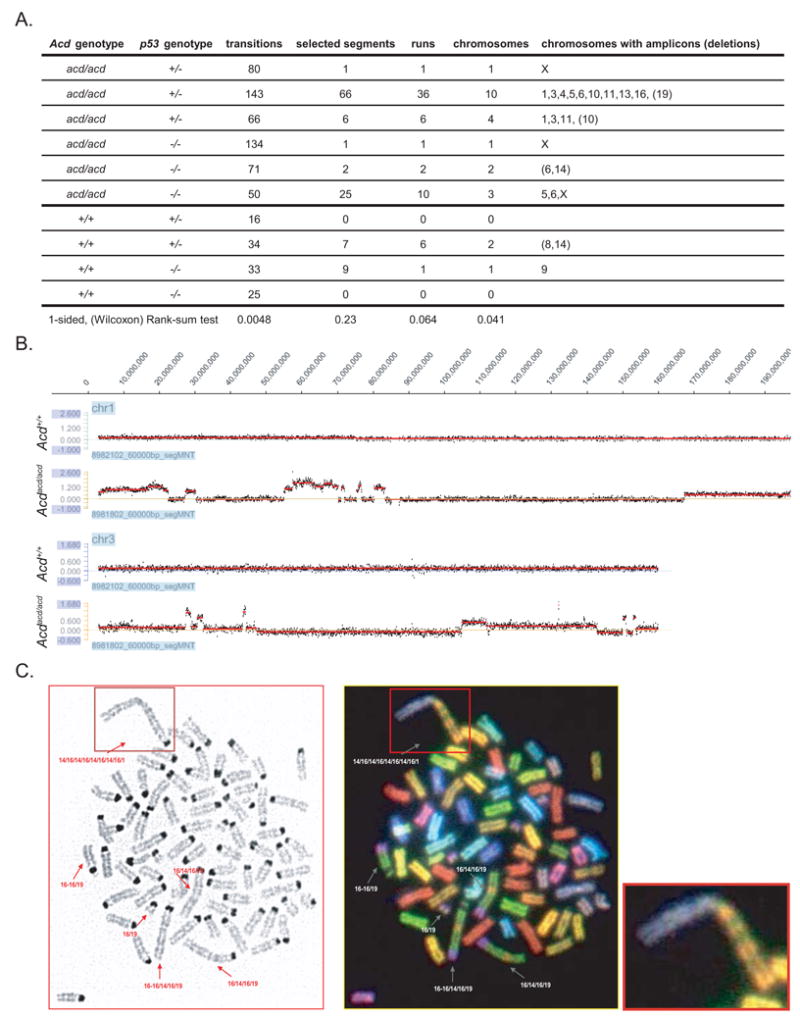

We next compared telomere length in neoplastic and non-neoplastic tissues from different genotypes. In contrast to previous cell culture experiments that reported an increase in telomere length we did not observe a significant difference between non-neoplastic tissues from Acdacd/acd and Acd+/+ animals (Fig. 6E). Some degree of telomere shortening was observed in some tumors when compared to non-neoplastic tissue regardless whether they were from Acdacd/acd or Acd+/+ animals. This is in contrast to the Terc−/− mouse model where progressive telomere shortening provides the basis for telomere dysfunction. Anaphase bridges are viewed as one morphological correlate of breakage-fusion bridge cycles (BFBs). Therefore, we analyzed tumors and a tumor cell line by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and spectral karyotyping respectively. In CGH analysis multiple amplifications as well as areas of “step-like” amplifications were present in the genome from Acdacd/acd tumors (Fig. 7A & 7B, Suppl. Fig. 6). These alterations are an expected result of recurrent BFBs. The average number of segments deviating from the normal tissue baseline was higher in Acdacd/acd than Acd+/+ tumors (90.6 +/− 38.4 transition points vs. 27 +/− 8.3 transition points, p=0.0048) (Fig. 7A). As this analysis may be influenced by simple background noise of the hybridization analysis, we next identified the number of chromosomes affected by copy number alterations. There were significantly more chromosomes with at least one copy number change in Acdacd/acd than Acd+/+ tumors. Notably, several of the observed amplifications encompass loci that may contribute to tumorigenesis. This includes amplifications of potential or proven oncogenes such as the cluster of Wnt genes on chromosome 11 and the Kras locus on chromosome 6, which has recently been shown to be amplified in tumors from Terc−/− mice. As a proof of principle, we found very specific rearrangements by spectral karyotyping analysis of an Acdacd/acd p53−/− rhabdomyosarcoma cell line, consisting of segments of two different chromosomes in an alternating pattern (Fig. 7C). These alterations are likely due to reoccurring BFBs involving two different chromosomes and represent the cytogenetic correlate of the stepwise regional amplifications found in CGH analysis.

Figure 7. Telomere deprotection in tumors from Acdacd/acd mice leads to genomic and cytogenetic alterations as a consequence of breakage fusion bridge cycles.

(A) Table summarizing characteristics of Acdacd/acd tumors as analyzed by CGH. Acdacd/acd tumors have significantly more transition points compared to Acd+/+ tumors as would be expected with repeated BFBs and significantly more chromosomes exhibited copy number alterations.

(B) CGH example of tumor DNA normalized to same animal liver DNA. Multiple amplifications sometimes presenting in a stepwise manner of increasing amplification values on the same chromosome (e.g. chr. 1 and chr. 3 of two samples) were observed in Acdacd/acd (lower panel) but not in Acd+/+ tumors (upper panel) (y-axis: log2 of tumor/liver).

(C) Spectral karyotyping of a cell line derived from a Acdacd/acd p53−/− rhabdomyosarcoma revealed genomic rearrangements in the form of hybrid chromosomes consisting of genomic stretches of original chromosome 16 and chromosome 19 (see magnification lower right)

Discussion

In this study we show that the ablation of p53 both profoundly rescues a number of characteristics of the acd phenotype and increases tumorigenesis. These results underscore the importance of p53 activation as a driving force in the development of major characteristics of the adrenocortical dysplasia phenotype. The acd mouse is the first viable animal model that permits analysis of the selective deficiency of an integral part of the shelterin complex. Moreover, acd mice allow for analysis of the contribution of telomere deprotection in the absence of telomere shortening to genetic instability and tumorigenesis. In contrast telomere dysfunction in Terc−/− mice is less defined and only observed after significant telomere shortening following breeding over successive generations. Deprotection versus shortening may underlie the distinct phenotypes of acd mice and Terc−/− mice.

Phenotypic rescue through the ablation of p53 in the Acdacd/acd mice was most profound in the skin where hyperpigmention was macroscopically completely absent in Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice. Two possible scenarios are discussed as the basis for hyperpigmentation in acd mice. Elevated ACTH and MSH levels in the setting of adrenocortical insufficiency could directly stimulate melanocytes or, alternatively, melanocytes that progressed to senescence could be more active in terms of pigment production. The first possibility seems to be unlikely because mouse models of adrenocortical insufficiency like the Mc2r−/− (ACTH receptor) mouse do not develop hyperpigmentation (personal communication D. Chida) (Chida et al., 2007). Furthermore, we were not able to detect significant differences in baseline ACTH and corticosterone levels (data not shown). Overall it seems more likely that skin hyperpigmentation is induced by telomere deprotection and direct activation of p53-sensitive pathways in melanocytes as it has been shown for other mouse models (Atoyan et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2007; Hadshiew et al., 2008; Khlgatian et al., 2002).

Male germ cells have a very high proliferative rate and therefore, seem to depend more than other tissues on telomere integrity and perhaps telomerase activity (Hemann et al., 2001; Lee et al., 1998). We did not observe any rescue of the testicular Acdacd/acd phenotype through p53 ablation in Acdacd/acd animals, which is in contrast to the moderate rescue observed in late generation Terc−/− p53−/− mice (Chin et al., 1999). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that unlike other tissues, germ cells do not completely depend on p53-sensitive pathways to induce their removal from the proliferative cell pool. It is also possible that different degrees of severity of telomere dysfunction can induce alternative pathways in an organ-dependent manner. The observation of completely empty SCOS-like tubules adjacent to seminiferous tubules with grossly normal spermatogenesis suggests a developmental defect in Acdacd/acd mice, as it seems unlikely that the complete germ cell epithelium of some tubules but not others disappears at the same time as the result of postnatal germ cell failure. For a degenerative mechanism in adult life, one would expect random losses of germ cells and an overall reduction of spermatogenesis rather than the observed “all-or-nothing” phenomenon. It is worthwhile mentioning that TPP1/ACD expression and telomerase activity are reduced in biopsies of SCOS testes (Feig et al., 2007; Schrader et al., 2002).

A main characteristic of the acd phenotype is cytomegalic adrenal hypolplasia congenita (AHC) which is not observed in late generation Terc−/− mice (data not shown) and has not been reported for any other mouse model of telomere dysfunction. In this study we show that the adrenal acd phenotype is caused by the induction of p53-dependent senescence. In the adrenal cortex of Acdacd/acd p53−/− mice we observe a normalization of organ size and architecture. In humans, cytomegalic AHC is observed in random pediatric or fetal autopsies as well as part of several syndromes. The majority of humans with cytomegalic AHC (with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) have a germ line mutation in NR0B1 (DAX1) (Achermann et al., 1999; Zanaria et al., 1994). The emerging role of NR0B1 in embryonic and tumor stem cell physiology suggests that cytomegalic adrenal failure may reflect a common morphological endpoint of stem cell failure and exhaustion of organ maintenance capacity due to a number of causes, including telomere dysfunction (Kim et al., 2008; Mendiola et al., 2006; Niakan et al., 2006).

In summary, ablation of p53 rescues the Acdacd/acd phenotype to varying degrees and in an organ-specific manner. The differences of the Acdacd/acd and the Terc−/− phenotype and their different rescue by p53 ablation can be explained by distinct molecular mechanisms induced by either short telomeres or deprotected telomeres. Alternatively, telomere dysfunction induced by deprotection in Acdacd/acd mice could be more severe than telomere dysfunction induced by telomere shortening in Terc−/− mice and therefore not as readily rescued by simple p53 ablation. Indeed, one would expect some telomere deprotection on every telomere in Acdacd/acd mice due to the severe deficiency in Tpp1/Acd as opposed to Terc−/− mice, where telomere decapping gradually develops with the loss of telomere sequences, resulting in the inability to bind shelterin components. Furthermore, it would be of interest to investigate potential roles of TPP1/Acd independent of its function in telomere protection. Such functions have been discovered for the protein component of telomerase TERT that participates in telomere-independent stem cell physiology (Choi et al., 2008; Sarin et al., 2005).

The onset of tumor development was significantly accelerated in Acdacd/acd p53−/− and Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice when compared to their Acd+/+ p53−/− and Acd+/+ p53+/− littermates, respectively. This underscores the role of telomere dysfunction in the induction of tumorigenesis as it has been described for Terc−/− mice (Artandi et al., 2000; Chin et al., 1999). For the Acdacd/acd phenotype, the sole driving force for genomic instability can be attributed to the telomere deprotection phenotype (Else et al., 2007; Hockemeyer et al., 2007). In contrast to the Terc−/− mice, no telomere shortening was necessary for tumor development. Though our experiments do not entirely exclude the possibility that a small fraction of telomeres reach a critical short length and dysfunctional state, this possibility seems to be unlikely as we did not observe any differences in telomere length comparing normal tissues from Acdacd/acd and Acd+/+ animals. Some degree of telomere shortening was inconsistently observed comparing tumor tissue and normal tissue (liver) from the same animal and was independent of the Acd genotype. Furthermore, a hallmark of telomere dysfunction in Terc−/− mice is the presence of chromosomal fusions lacking telomere signals at the fusion site (Hande et al., 1999). In contrast, we have previously shown that telomere signals are detectable at the non-homologous fusion sites in Acdacd/acd MEFs (Else et al., 2007). The lack of significant telomere length differences between Acdacd/acd and Acd+/+ animals shows that Tpp1/Acd deficiency in vivo does not lead to average telomere length differences as opposed to reports in human cells where the acute loss of TPP1/ACD, or the use of a dominant negative isoform, leads to excessive telomere lengthening (O’Connor et al., 2006; Xin et al., 2007; Ye et al., 2004).

Considering the role of telomeres and telomerase in the telomere-based two step model of carcinogenesis, the acd mouse is a useful tool to selectively investigate the in vivo consequences of telomere deprotection (Artandi and DePinho, 2000; Cosme-Blanco et al., 2007; Ju and Rudolph, 2006). Telomere dysfunction is hypothesized to lead to genomic shuffling via BFBs, which contributes to tumorigenesis. Later, the genome becomes stabilized through a telomere maintenance mechanism such as telomerase activity or alternative telomere length maintenance mechanisms (ALT) (Farazi et al., 2003; Maser and DePinho, 2002; Rudolph et al., 2001). Telomere deprotection has been recently suggested to participate in oncogenesis in a variety of human cancers (Poncet et al., 2008; Vega et al., 2008). Our studies of the Acdacd/acd p53−/− mouse model reproduce the genomic alterations proposed by the telomere-based model of carcinogenesis (Chin et al., 2004; O’Hagan et al., 2002). The multiple chromosomal amplifications and cytogenic changes observed in Acdacd/acd tumors together with an increased number of anaphase bridges support BFBs as a main mechanism of ongoing genomic alterations in tumorigenesis. Additionally, we argue that BFB-induced losses of genetic material are also responsible for the increased frequency of loss of the wt p53 allele in Acdacd/acd p53+/− vs. Acd+/+ p53+/− tumors.

The observations of marked senescence in the adrenal cortex of Acdacd/acd mice and the development of ACC in Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice, suggests that the escape from senescence may contribute to adrenocortical carcinogenesis. Although ACC is not the main neoplasia (5% of tumors in Acdacd/acd p53+/−) observed in this study, it is a finding of great importance as there is currently no mouse model that specifically develops ACCs. ACC in humans is a rare disease with a dismal prognosis. Mouse models of telomere dysfunction may be further exploited to study this rare type of cancer and may serve as a useful tool to understand the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of this disease. In humans ACC is one of the syndrome-defining pathologies in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. The specific occurrence of this tumor in Acdacd/acd p53+/− mice may further suggest a participation of telomere dysfunction in Li-Fraumeni associated carcinogenesis. Indeed it has recently been shown that telomere length correlates with age at tumor onset in patients with Li-Fraumeni (Tabori et al., 2007).

It has been assumed for a long time that telomere deprotection can provide the basis for generating a pro-cancer genome during tumorigenesis in human tissues. We believe that the acd mouse provides an excellent model for the in vivo dissection of these mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and will increase our understanding of how telomere pathophysiology impacts the origin of tumors in mammalian organisms. Lastly TPP1/ACD and other genes of the shelterin complex may facilitate both our understanding of a genetic basis in patients with dyskeratosis congenital-like heritable cancer syndromes that do not exhibit significant changes in overall telomere length.

Experimental procedures

Animal procedures

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with institutionally approved and current animal care guidelines (UCUCA-09458). Adrenocortical dysplasia (acd) mice used in this study were from a mixed DW/JxCAST/Ei background and genotyped as described previously (Keegan et al., 2005). p53−/− mice (C57BL6/J;Trp53tm1Tyj) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (JAX mice and Services, Bar Harbor, ME) and genotyped as described previously (Jacks et al., 1994). Double heterozygous animals (Acd+/acd p53+/−) were crossed to generate the genotypes used in this study. A series of animals (≥5) of each genotype were weighed at 3 weeks and 6 weeks. Initially autopsies were conducted at 6 weeks of age, when organ weights of adrenal glands and testis were recorded and tissues were either preserved for histological analysis or snap frozen for RNA preparation. For survival studies autopsy was conducted either at the time of obvious tumor growth or at spontaneous death. Some tumors samples were used to establish cell lines. Parts of the tumor were disintegrated using cell strainers, washed in PBS and grown on fibronectin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) coated plates in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and antifungal, antibacterial solution (all Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Chi-Square test was used to test the amount of observed pups with the Acdacd/acd genotype within a certain p53 genotype. Survival between groups was analyzed with log-rank tests. Animals without obvious tumor, or in which degradation precluded meaningful analysis or with a histological benign pathology were considered censored at the time of death.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

For general histological analysis tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, dehydrated and paraffin embedded. 6μm sections were used for routine hematoxylin and eosin staining or further immunohistological procedures. Immunohistochemical analyses followed standard protocols using the ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and DAB Sigma Fast (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or fluorescent secondary antibodies. Primary antibody incubation was done at 4°C overnight. Primary and secondary antibodies were used at the following concentrations: p21 (1:50, mouse monoclonal, #556430, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), GCNA (1:200, rat monoclonal IgM, obtained from G. C. Enders (Enders and May, 1994)), Sf1 (1:1000, provided by Ken-ichirou Morohashi), pan-keratin (1:100, mouse monoclonal, #MS343, Lab Vision, Fremont, CA), γH2ax (1:50, #2577 Cell Signalling, Danvers, MA), biotinylated anti-mouse (1:200, BA9200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), biotinylated anti-rabbit (1:200, BA1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), biotinylated-anti-rat (1:200, #161603, KPL, Gaithersburg, MD), Alexa-Fluor 486-coupled anti mouse IgG (1:200, #A11029, Carlsbad, CA),. Telomere FISH procedure was conducted as described previously following a protocol modified from Meeker et al. (Else et al., 2008; Meeker et al., 2002). Pictures were taken and in plane telomere signals were counted (at least 250/slide) in nuclei with positive γH2ax staining. The ratio of telomeres with to telomeres without co-localizing γH2ax staining (TIFs) was calculated for at least 4 tumors per group. Anaphase bridges and anaphase mitoses were counted in ≥4 tumors per genotype. The anaphase bridge index was calculated as the ratio of anaphase bridges per total metaphases. Pathological diagnosis was made in synopsis of macroscopic and microscopic pathologies. Images were captured with an Optiphot-2 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with a DP-70 camera and software system (Olympus, Hauppauge, NY). For comparative immunohistochemical analyses, system and software processing (Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, San Jose, CA) settings were kept constant over sample groups. For statistical analysis data were fit using a 1-way ANOVA, and pairs of groups compared using the resulting F-tests.

Reverse Transcribed Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted from adrenal glands by a standard method using TRIzol® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA was quantified and reverse transcription was carried out using the i-Script™ kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) following the manufacturers protocol. Intron spanning primers were used for Gapdh (fwd, 5′-TGT CCG TCG TGG ATC TGA C-3′; rev, 5-CCT GCT TCA CCA CCT TCT TG-3′), Sf1 (fwd, 5′-ACA AGC ATT ACA CGT GCA CC-3′; rev, 5′-TGA CTA GCA ACC ACC TTG CC-3′), p21 (Cdkn1a) (fwd 5′-TCC ACA GCG ATA TCC AGA CA-3′; rev, 5′-GGA CAT CAC CAG GAT TGG AC-3′) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For the PCR reaction 2x SYBR Green PCR master mix was used in a ABI 7300 thermocycler (both Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For statistical analysis data were fit using a 1-way ANOVA, and pairs of groups compared using F-tests.

Telomere restriction fragment (TRF) length assay

TRF analysis utilized published protocols with modifications (Else et al., 2008; Hemann and Greider, 2000). A purification kit (#13343, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to obtain high molecular weight genomic DNA. 2μg genomic DNA were digested with 60U of Dpn II for 36h and run in 1% agarose (Seakem, Lonza, Rockland, ME) using a CHEF mapper (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The automatic algorithm was set to a range of 5kb to 200kb. A PFG low molecular weight marker (NEB, Ipswich, MA) was used as a size marker. DNA-gels were further processed as described previously (Else et al., 2008).

Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH)

Isolated high molecular weight genomic DNA (#13343, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from 6 acd tumors and 4 wt tumors was run on a 1% agarose gel and spectrophotometric measurements at 230nm, 260nm and 280nm were conducted to exclude samples with significant degradation or contamination. CGH was conducted on the CGH0150-WMG platform using the NimbleGen service (NimbleGen, Madison, WI). The raw data is available in ArrayExpress (experiment E-TABM-680). The NimbleGen CGH-SegMNT algorithm was used to divide chromosomes into segments that were separated by transitions in the logarithm of test to reference sample ratios. We excluded data from the Y chromosome (which had a lower probe density) as well as small segments represented by 30 or fewer probes. The software created segments even when the change in average estimated log-ratio was very small. Consequently we selected segments as abnormal if the base-2 log-ratio was greater than 0.5 or less than −0.5, or if the log-ratio was larger than 0.3 in absolute value and the change in log-ratio from the previous segment was also greater than 0.3. The second criterion selects segments where the change in copy number was abrupt, while the first criterion selects a segment even if the estimated log-ratio rises and falls gradually. We combined neighboring selected segments that were all estimated to have copy numbers greater than 2, or all less than 2, into “runs”, and counted the number of distinct runs in each tumor. We counted the total number of chromosomes containing selected segments for each tumor, and compared these and the other metrics between Acdacd/acd and Acd+/+ tumors using one-sided Rank-Sum tests.

Karyotypic Analyses

Metaphases were generated using standard procedures. Slides were then subjected to SKY analysis using mouse SKY paint mixture from Applied Spectral Imaging (ASI, Vista, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All imaging was performed on an Olympus BX-61 microscope equipped with an interferometer driven by a desktop computer and specialized software (ASI, Vista, CA). Inverted DAPI images were generated using SKYview software (ASI, Vista, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

TE and AT were sponsored through generous scholarships by the Garry Betty Foundation. This work has been sponsored by grant NIH NIDDK DK62027 (GDH) and a grant from the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Research Foundation (DOF). The authors would like to thank the DNA sequencing core facility at the University of Michigan, Tom Giordano for his endocrine pathology expertise, Buffy Ellsworth from Sally Camper’s Lab for IHC advice and Jose Luis Garcia Perez for intellectual exchange and experimental advice, as well as Guido Bommer, Joanne Heaton, Catherine Keegan and Sonalee Shah for editorial advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature

- Achermann JC, Gu WX, Kotlar TJ, Meeks JJ, Sabacan LP, Seminara SB, Habiby RL, Hindmarsh PC, Bick DP, Sherins RJ, et al. Mutational analysis of DAX1 in patients with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or pubertal delay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4497–4500. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artandi SE. Telomere shortening and cell fates in mouse models of neoplasia. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:44–47. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artandi SE, Chang S, Lee SL, Alson S, Gottlieb GJ, Chin L, DePinho RA. Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice. Nature. 2000;406:641–645. doi: 10.1038/35020592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artandi SE, DePinho RA. A critical role for telomeres in suppressing and facilitating carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atoyan RY, Sharov AA, Eller MS, Sargsyan A, Botchkarev VA, Gilchrest BA. Oligonucleotide treatment increases eumelanogenesis, hair pigmentation and melanocortin-1 receptor expression in the hair follicle. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:671–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer WG, Sweet HO, Bronson RT, Shire JG, Orth DN, Davisson MT. Adrenocortical dysplasia: a mouse model system for adrenocortical insufficiency. J Endocrinol. 1994;141:33–43. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1410033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco MA. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrg1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco MA, Lee HW, Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp PM, DePinho RA, Greider CW. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell. 1997;91:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli GB, de Lange T. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:712–718. doi: 10.1038/ncb1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang YJ, Kim SH, Tessarollo L, Campisi J, Hodes RJ. Telomere-associated protein TIN2 is essential for early embryonic development through a telomerase-independent pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6631–6634. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6631-6634.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida D, Nakagawa S, Nagai S, Sagara H, Katsumata H, Imaki T, Suzuki H, Mitani F, Ogishima T, Shimizu C, et al. Melanocortin 2 receptor is required for adrenal gland development, steroidogenesis, and neonatal gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18205–18210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706953104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin K, de Solorzano CO, Knowles D, Jones A, Chou W, Rodriguez EG, Kuo WL, Ljung BM, Chew K, Myambo K, et al. In situ analyses of genome instability in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:984–988. doi: 10.1038/ng1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L, Artandi SE, Shen Q, Tam A, Lee SL, Gottlieb GJ, Greider CW, DePinho RA. p53 deficiency rescues the adverse effects of telomere loss and cooperates with telomere dysfunction to accelerate carcinogenesis. Cell. 1999;97:527–538. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Southworth LK, Sarin KY, Venteicher AS, Ma W, Chang W, Cheung P, Jun S, Artandi MK, Shah N, et al. TERT promotes epithelial proliferation through transcriptional control of a Myc- and Wnt-related developmental program. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosme-Blanco W, Shen MF, Lazar AJ, Pathak S, Lozano G, Multani AS, Chang S. Telomere dysfunction suppresses spontaneous tumorigenesis in vivo by initiating p53-dependent cellular senescence. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:497–503. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui R, Widlund HR, Feige E, Lin JY, Wilensky DL, Igras VE, D’Orazio J, Fung CY, Schanbacher CF, Granter SR, Fisher DE. Central role of p53 in the suntan response and pathologic hyperpigmentation. Cell. 2007;128:853–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr, Butel JS, Bradley A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else T, Giordano TJ, Hammer GD. Evaluation of telomere length maintenance mechanisms in adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1442–1449. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else T, Hammer GD. Genetic analysis of adrenal absence: agenesis and aplasia. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else T, Theisen BK, Wu Y, Hutz JE, Keegan CE, Hammer GD, Ferguson DO. Tpp1/Acd maintains genomic stability through a complex role in telomere protection. Chromosome Res. 2007;15:1001–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders GC, May JJ., 2nd Developmentally regulated expression of a mouse germ cell nuclear antigen examined from embryonic day 11 to adult in male and female mice. Dev Biol. 1994;163:331–340. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farazi PA, Glickman J, Jiang S, Yu A, Rudolph KL, DePinho RA. Differential impact of telomere dysfunction on initiation and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5021–5027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig C, Kirchhoff C, Ivell R, Naether O, Schulze W, Spiess AN. A new paradigm for profiling testicular gene expression during normal and disturbed human spermatogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:33–43. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW. Telomere length regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:337– 365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Deng Y, Lin Y, Cosme-Blanco W, Chan S, He H, Yuan G, Brown EJ, Chang S. Dysfunctional telomeres activate an ATM-ATR-dependent DNA damage response to suppress tumorigenesis. Embo J. 2007;26:4709–4719. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadshiew I, Barre K, Bodo E, Funk W, Paus R. T-oligos as differential modulators of human scalp hair growth and pigmentation: a new "time lapse system" for studying human skin and hair follicle biology in vitro? Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300:155–159. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp P, Blasco MA. Telomere length dynamics and chromosomal instability in cells derived from telomerase null mice. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:589–601. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemann MT, Greider CW. Wild-derived inbred mouse strains have short telomeres. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4474–4478. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.22.4474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemann MT, Rudolph KL, Strong MA, DePinho RA, Chin L, Greider CW. Telomere dysfunction triggers developmentally regulated germ cell apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2023–2030. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockemeyer D, Daniels JP, Takai H, de Lange T. Recent expansion of the telomeric complex in rodents: Two distinct POT1 proteins protect mouse telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockemeyer D, Palm W, Else T, Daniels JP, Takai KK, Ye JZ, Keegan CE, de Lange T, Hammer GD. Telomere protection by mammalian Pot1 requires interaction with Tpp1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:754–761. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghtaling BR, Cuttonaro L, Chang W, Smith S. A dynamic molecular link between the telomere length regulator TRF1 and the chromosome end protector TRF2. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, Weinberg RA. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JJ, de Lange T. Significant role for p16INK4a in p53- independent telomere-directed senescence. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2302–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Z, Rudolph KL. Telomeres and telomerase in cancer stem cells. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlseder J, Kachatrian L, Takai H, Mercer K, Hingorani S, Jacks T, de Lange T. Targeted deletion reveals an essential function for the telomere length regulator Trf1. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6533–6541. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6533-6541.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan CE, Hutz JE, Else T, Adamska M, Shah SP, Kent AE, Howes JM, Beamer WG, Hammer GD. Urogenital and caudal dysgenesis in adrenocortical dysplasia (acd) mice is caused by a splicing mutation in a novel telomeric regulator. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:113–123. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khlgatian MK, Hadshiew IM, Asawanonda P, Yaar M, Eller MS, Fujita M, Norris DA, Gilchrest BA. Tyrosinase gene expression is regulated by p53. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:126–132. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Chu J, Shen X, Wang J, Orkin SH. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, Horner JW, 2nd, Greider CW, DePinho RA. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392:569–574. doi: 10.1038/33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Safari A, O’Connor MS, Chan DW, Laegeler A, Qin J, Songyang Z. PTOP interacts with POT1 and regulates its localization to telomeres. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:673–680. doi: 10.1038/ncb1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Snow BE, Hande MP, Yeung D, Erdmann NJ, Wakeham A, Itie A, Siderovski DP, Lansdorp PM, Robinson MO, Harrington L. The telomerase reverse transcriptase is limiting and necessary for telomerase function in vivo. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1459–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Ikeda Y, Lala DS, Baity LA, Meade JC, Parker KL. A cell-specific nuclear receptor plays essential roles in adrenal and gonadal development. Endocr Res. 1995;21:517–524. doi: 10.3109/07435809509030469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RS, DePinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297:565–569. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5581.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker AK, Gage WR, Hicks JL, Simon I, Coffman JR, Platz EA, March GE, De Marzo AM. Telomere length assessment in human archival tissues: combined telomere fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1259–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62553-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiola M, Carrillo J, Garcia E, Lalli E, Hernandez T, de Alava E, Tirode F, Delattre O, Garcia-Miguel P, Lopez-Barea F, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor DAX1 is up-regulated by the EWS/FLI1 oncoprotein and is highly expressed in Ewing tumors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1381–1389. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niakan KK, Davis EC, Clipsham RC, Jiang M, Dehart DB, Sulik KK, McCabe ER. Novel role for the orphan nuclear receptor Dax1 in embryogenesis, different from steroidogenesis. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;88:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MS, Safari A, Xin H, Liu D, Songyang Z. A critical role for TPP1 and TIN2 interaction in high-order telomeric complex assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11874–11879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605303103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hagan RC, Chang S, Maser RS, Mohan R, Artandi SE, Chin L, DePinho RA. Telomere dysfunction provokes regional amplification and deletion in cancer genomes. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:149–155. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncet D, Belleville A, de Roodenbeke CT, de Climens AR, Simon EB, Merle-Beral H, Callet-Bauchu E, Salles G, Sabatier L, Delic J, Gilson E. Changes in the expression of telomere maintenance genes suggest global telomere dysfunction in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2388–2391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KL, Chang S, Lee HW, Blasco M, Gottlieb GJ, Greider C, DePinho RA. Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell. 1999;96:701–712. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KL, Millard M, Bosenberg MW, DePinho RA. Telomere dysfunction and evolution of intestinal carcinoma in mice and humans. Nat Genet. 2001;28:155–159. doi: 10.1038/88871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin KY, Cheung P, Gilison D, Lee E, Tennen RI, Wang E, Artandi MK, Oro AE, Artandi SE. Conditional telomerase induction causes proliferation of hair follicle stem cells. Nature. 2005;436:1048–1052. doi: 10.1038/nature03836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader M, Muller M, Schulze W, Heicappell R, Krause H, Straub B, Miller K. Quantification of telomerase activity, porphobilinogen deaminase and human telomerase reverse transcriptase mRNA in testicular tissue - new parameters for a molecular diagnostic classification of spermatogenesis disorders. Int J Androl. 2002;25:34–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. Different telomere damage signaling pathways in human and mouse cells. Embo J. 2002;21:4338–4348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabori U, Nanda S, Druker H, Lees J, Malkin D. Younger age of cancer initiation is associated with shorter telomere length in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1415–1418. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel B, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell. 1998;92:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega F, Cho-Vega JH, Lennon PA, Luthra MG, Bailey J, Breeden M, Jones D, Medeiros LJ, Luthra R. Splenic marginal zone lymphomas are characterized by loss of interstitial regions of chromosome 7q, 7q31.32 and 7q36.2 that include the protection of telomere 1 (POT1) and sonic hedgehog (SHH) genes. Br J Haematol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Multani AS, He H, Cosme-Blanco W, Deng Y, Deng JM, Bachilo O, Pathak S, Tahara H, Bailey SM, et al. Pot1 deficiency initiates DNA damage checkpoint activation and aberrant homologous recombination at telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Liu D, Wan M, Safari A, Kim H, Sun W, O’Connor MS, Songyang Z. TPP1 is a homologue of ciliate TEBP-beta and interacts with POT1 to recruit telomerase. Nature. 2007;445:559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature05469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JZ, Hockemeyer D, Krutchinsky AN, Loayza D, Hooper SM, Chait BT, de Lange T. POT1-interacting protein PIP1: a telomere length regulator that recruits POT1 to the TIN2/TRF1 complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1649–1654. doi: 10.1101/gad.1215404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanaria E, Muscatelli F, Bardoni B, Strom TM, Guioli S, Guo W, Lalli E, Moser C, Walker AP, McCabe ER, et al. An unusual member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily responsible for X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita. Nature. 1994;372:635–641. doi: 10.1038/372635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.