Abstract

pH-Responsive block copolymers, having two segments with functionalities of differing pKa, were prepared by NMP, providing a “green” route to the assembly of core/shell functionalizable nanostructures.

Stimuli-responsive block copolymers are of significant interest due to their ability to impose morphological, charge, or structural changes of their self-assembled nanostructures in response to a specific stimulus. One of the most intriguing benefits that some of these systems exhibit is a reversible nanoassembly process. External stimuli such as pH,1 temperature,2 light,3 or a combination of these4 have been shown to afford chemically-driven structural reorganization events. For instance, Kataoka and co-workers5 reported spontaneous formation of polyion complex micelles from a series of oppositely-charged block ionomers in aqueous media, which allow for the incorporation of charged macromolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids. Armes and co-workers, employed several techniques7 to probe the pH-controlled assembly/disassembly of diblock and triblock copolymers into supramolecular micelles8 and vesicles,9 comprised of block segments having amino groups. The assembly process was triggered by deprotonation of the amines upon elevation of the pH. Dual functionalities have been employed in a few cases, to achieve protonation/deprotonation of selective domains within the nanoscale assemblies,10 including also an elegant example that employed an oligomer of poly(L-glutamic acid) and poly(L-lysine), PGA15-b-PLys15, to afford reversible inside-out vesicle reorganizations, for which vesicles existed at low (<4) and high (>10) pH values.11

Our aim is to utilize block copolymers having dual functional blocks, whose pKa values are significantly different from each other, thereby providing a wide range of solution pH values, including physiological pH, over which distinct micelles can exist. Moreover, we are interested in the pH-responsive functionalities also possessing orthogonal chemical reactivities. The examples of pH-responsive materials based upon tertiary amines do not offer rich functionalization chemistries, and the system based upon glutamic acid and lysine could experience complications from complementary reactivites for the two block segments. Herein, we report aqueous-only, pH-induced reversible assembly of micelles from poly(acrylic acid)-b-poly(p-hydroxystyrene) (PAA-b-PpHS), which reveals its amphiphilicity over a pH range of 10 to 4. At higher pH values (>10), the entire polymer is water soluble, and at lower pH values (<4), it is water insoluble. Although the core constituting segment, poly(p-hydroxystyrene), has found prolific application in photoresist technologies,12 its employment as a pH-responsive material for nanoassembly/disassembly is unique.

The diblock copolymer was prepared by controlled radical polymerization, which allowed for the convenient incorporation of protected functionalities into the block segments that would lead ultimately to the core and the shell regions of the micellar assemblies (Fig. 1). Poly(tert-butyl acrylate)131-b-poly(4-acetoxystyrene)76 (2), PtBA131-b-PAcS76, was synthesized via sequential nitroxide mediated radical polymerization (NMP) reactions.13 PtBA131 was prepared by NMP of tert-butyl acrylate, and then was followed by chain extension with 4-acetoxystyrene to yield 2. Base-promoted cleavage of the acetoxy groups and then acid-catalyzed deprotection of the tert-butyl residues afforded PAA131-b-PpHS76, 1 (Fig. 1). The pH-responsive diblock copolymer (1) was purified by dialysis against nanopure water for 3 days to remove residual trifluoroacetic acid and was then lyophilized.

Fig. 1.

Preparation of PAA131-b-PpHS76 and its pH-induced micelle assembly in aqueous solution.

With pKa values of ca. 4 and 10 for the PAA and PpHS block segments, this block copolymer was expected to assemble into micelles at pH values below 10 and to aggregate and precipitate at pH values below 4. The purified polymer was dissolved in deuterium oxide at room temperature, which immediately resulted in a solution of pH 4. At this point, the PpHS segment was protonated, while a sufficient number of the acrylic acid residues remained deprotonated to provide for solubility, effecting amphiphilicity of the diblock copolymer. Thus, the diblock copolymers had spontaneously assembled into micelles, 2. D2O-Suppressed 1H NMR spectra (Fig. 2) of the diblock copolymer were then obtained as a function of increasing pH (controlled by adding NaOD solution drop-wise to achieve the desired pH) to determine the diblock copolymer’s critical pH values. A slight upfield shift was observed for the methine resonance from 2.4 to 2.2 ppm, which occurred upon raising the pH to 6. This resonance continued to move to higher field as the pH was increased to 9, and is attributed to deprotonation of acrylic acid groups. From pH 9 to 11, as the PpHS core underwent deprotonation, the micelle disassembled into diblock copolymer chains due to conversion to entirely hydrophilic polymer chains. This process, revealed the PpHS core and caused its disassembly, which was shown by the appearance of the aromatic protons of the PpHS block (resonating at 6.4 ppm) and by their gradual approach toward full integration as the pH was raised to 14. Furthermore, the appearance of benzylic protons (b′) and their growth from pH 9 to 14 also confirmed the solubilization of the PpHS. Below a solution pH of 3, the diblock copolymer precipitated from the aqueous solution. These results (large-scale precipitated aggregates below pH 4; micellar assemblies between pH 4 and 10) were in agreement with the pKa values of AA (ca. 4) and pHS (ca. 10).

Fig. 2.

A composite of 1H NMR spectra (500 MHz) of PAA131-b-PpHS76, as amphiphilic micellar assemblies, 2, at low pH and disassembly into solvated hydrophilic polymer chains, 1, as the pH is elevated.

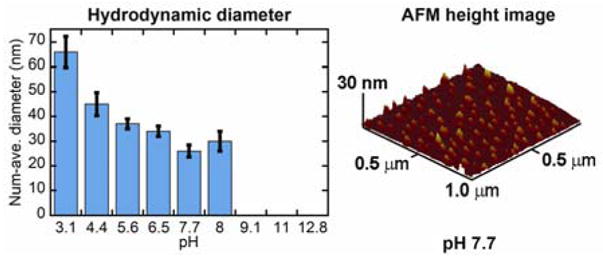

The hydrodynamic diameters (Dh) of the micelles were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) for individual samples prepared at six pH values (Fig. 3, left panel). The number-average Dh of the micelles were ca. 25 nm at pH 7.7 and increased to ca. 65 nm at pH 3. No correlation could be fit to the DLS data collected for samples at pH values above 8, due to a lack of micellar nanoassemblies and insufficient light scattering. The increase in average particle size at low pH was attributed to aggregation of the micelles, caused by reduction of electrostatic repulsions among particles as the PAA shell became protonated. Furthermore, data from 1H NMR diffusion (D) experiments gave hydrodynamic radius (Rhyd) values as a function of pH that were in good agreement with the DLS data: DpH6 of 1.60×10−6 cm2s−1, which correlated to Rhyd(pH6) of 29 nm, and DpH4 of 7.64×10−7 cm2s−1, which corresponded to Rhyd(pH4) of 62 nm.

Fig. 3.

Number-average Dh data for micelle 2 as a function of pH (left), as measured by DLS. Tapping-mode AFM image of micelle 2 (right), collected after deposition of the sample at solution pH 7.7 onto freshly-cleaved mica and allowing to dry under ambient conditions.

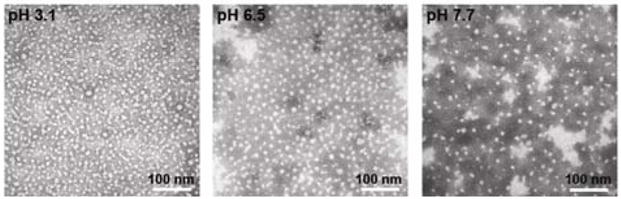

The integrity of the micellar assemblies upon deposition onto substrates and drying was also probed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). A typical micelle at pH 7 had an approximate height of ca. 5 nm, as measured by AFM (Fig. 3, right panel). The size of the core of the micelle remained ca. 16 nm in diameter from pH 3.2 to 7.1, as measured by TEM (Fig. 4), suggesting that the PpHS core retained its stability, with the increasing apparent particle size at low pH being due to particle-particle aggregation events.

Fig. 4.

TEM images of micelle 2, collected on samples deposited from solutions at pH values of 3.1, 6.5 and 7.7, onto carbon-coated copper grids, negatively-stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid.

We have demonstrated a pH-induced nanoassembly of PAA-b-PpHS, which avoids the need for organic solvents and contains functionalities that provide opportunities for further physical and chemical manipulations of the core and shell domains. Although the two components for this diblock are quite common, their combination provides a unique opportunity to tune the aqueous-based assembly/disassembly processes over a wide pH range. In addition, the phenolic groups of the core may lead to iodination or other chemistries for labeling within the nanostructure, while the acrylic acid groups of the shell can be used for attachment of various units to mediate biological interactions. Ongoing work is transforming this aqueous-based assembly/disassembly system into functional nanodevices, and also into covalent entities that will undergo reversible, pH-driven swelling/deswelling and physical reorganization.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [experimental details]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Baines FL, Billingham NC, Armes SP. Macromolecules. 1996;29:3416. [Google Scholar]; Liu S, Weaver JVM, Save M, Armes SP. Langmuir. 2002;18:8350. [Google Scholar]; Liu S, Armes SP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1413. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020415)41:8<1413::aid-anie1413>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sumerlin BS, Lowe AB, Thomas DB, McCormick CL. Macromolecules. 2003;36:5982. [Google Scholar]; Vamvakaki M, Palioura D, Spyros A, Armes SP, Anastasiadis SH. Macromolecules. 2006;39:5106. [Google Scholar]; Oishi M, Hayashi H, Itaka K, Kataoka K, Nagasaki Y. Colloid Polym Sci. 2007;285:1055. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Lokitz BS, McCormick CL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Skrabania K, Kristen J, Laschewsky A, Akdemir O, Hoth A, Lutz JF. Langmuir. 2007;23:84. doi: 10.1021/la061509w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang X, Luo S, Armes SP, Shi W, Liu S. Macromolecules. 2006;39:5987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, Shi L, Ma R, An Y, Xu Y, Wu K. Macromolecules. 2005;38:8850. [Google Scholar]; Lokitz B, York AW, Stempka JE, Treat ND, Li Y, Jarrett WL, McCormick CL. Macromolecules. 2007;40:6473. [Google Scholar]; Xu Y, Shi L, Ma R, Zhang W, An Y, Zhu XX. Polymer. 2007;48:1711. [Google Scholar]; Jiang X, Ge Z, Xu J, Liu H, Liu S. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:3184. doi: 10.1021/bm700743h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oishi M, Kataoka K, Nagasaki Y. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:677. doi: 10.1021/bc050364m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee AS, Bütün V, Vamvakaki M, Armes SP, Pople JA, Gast AP. Macromolecules. 2002;35:8540. [Google Scholar]; Zhu Z, Armes SP, Liu S. Macromolecules. 2005;38:9803. [Google Scholar]; Zhang J, Li Y, Armes SP, Liu S. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:12111. doi: 10.1021/jp075018b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rutkaite R, Swanson L, Li Y, Armes SP. Polymer. 2008;49:1800. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma Y, Tang Y, Billingham NC, Armes SP, Lewis AL, Lloyd AW, Salvage JP. Macromolecules. 2003;36:3475. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du J, Tang Y, Lewis AL, Armes SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17982. doi: 10.1021/ja056514l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu S, Weaver JVM, Tang Y, Billingham NC, Armes SP. Macromolecules. 2002;35:6121. [Google Scholar]; Liu S, Armes SP. Langmuir. 2003;19:4432. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Hernández J, Lecommandoux S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2026. doi: 10.1021/ja043920g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fréchet JMJ, Eichler E, Ito H, Willson CG. Polymer. 1983;24:995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benoit D, Chaplinski V, Braslau R, Hawker CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:3904. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.