Abstract

The success of many gene therapy applications hinges on efficient whole body transduction. In the case of muscular dystrophies, a therapeutic vector has to reach every muscle in the body. Recent studies suggest that vectors based on adeno-associated virus (AAV) are capable of body-wide transduction in rodents. However, translating this finding to large animals remains a challenge. Here we explored systemic gene delivery with AAV serotype-9 (AAV-9) in neonatal dogs. Previous attempts to directly deliver AAV to adult canine muscle have yielded minimal transduction due to a strong cellular immune response. However, in neonatal dogs we observed robust skeletal muscle transduction throughout the body after a single intravenous injection. Importantly, systemic transduction was achieved in the absence of pharmacological intervention or immune suppression and it lasted for at least 6 months (the duration of study). We also observed several unique features not predicted by murine studies. In particular, cardiac muscle was barely transduced in dogs. Many muscular dystrophy patients can be identified by neonatal screening. The technology described here may lead to an effective early intervention in these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Gene therapy carries the hope of a cure for many human diseases. Although numerous successes have been achieved in mouse models of human diseases, few have translated in human patients. Problems associated with scaling up are important contributors to the failures in clinical trials. The size of the human body is several hundred-fold larger than that of a mouse. The differences in the anatomy and physiology present a great challenge to faithfully predict the human outcomes based on mouse studies. Large animals, such as the dog, are excellent intermediate models to bridge the size gap.

Many diseases affect tissues that are widely distributed throughout the body. One such disease is Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). DMD is the most common childhood fatal muscle disease caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene. Patients lose their ambulation at early teenage and die prematurely before 30 years of age. Since dystrophin is a structural protein, an effective DMD gene therapy will require efficient transduction of all body muscles. Body-wide muscle gene transfer has only been reported recently with the adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector in rodents.1-10 Although this exciting development raises the hope of whole body correction of DMD, it is not clear whether the differences between small and large animals will limit systemic gene delivery in large animals.

To address this issue, we tested intravenous AAV delivery in dogs. Unlike murine muscle, canine muscle is notoriously difficult to transduce with AAV vectors.11-14 Direct muscle injection of AAV-2, 6, and 8 in adult dogs yields limited transduction unless a comprehensive immune suppression scheme is applied.13,14 This is mainly due to the strong cellular immune response in dog muscle.12,14 The immune system of newborn puppies is different from that of adult dogs.15 The neonatal period may represent a unique window to minimize cytotoxic T-lymphocyte reaction and achieve sustained AAV transduction. The viral capsid is an important determinant for AAV-associated immune response.16 Experimentation with alternative AAV serotypes may represent a valid approach to reduce immune response in canine muscle.

Several AAV serotypes including AAV-6, 8, and 9 have been used for systemic gene delivery in mice.1,3,7-10 Interestingly, different serotypes show distinctive transduction profiles. In particular, AAV-9 appears to transduce the heart better.6,7,9,10 Since Duchenne patients often suffer from severe cardiomyopathy, the cardiac tropism of AAV-9 may provide a unique therapeutic advantage for DMD gene therapy.

As a proof-of-concept, here we explored local and systemic muscle transduction of AAV-9, a serotype that has not yet been studied in dog muscles. The AAV vector used in this study expresses the human placental alkaline phosphatase (AP) reporter gene under the transcriptional control of the ubiquitous Rous sarcoma virus promoter (RSV). After direct muscle injection, we observed a strong cellular immune reaction in adult but not neonatal dogs. Importantly, a single intravenous injection in newborn dogs resulted in persistent skeletal muscle transduction throughout the body. Furthermore, robust skeletal muscle transduction did not induce a cellular immune response. Surprisingly, systemic AAV-9 delivery in dogs showed a transduction profile different from what has been reported in mice. In particular, both the fiber-type preference and cardiac tropism seen in mice were lost in neonatal dogs. In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time that whole body systemic transduction is feasible in large animals. The different transduction profiles between dogs and mice further highlight the challenge in translating mouse results to larger species.

RESULTS

AAV-9 efficiently transduces neonatal canine muscle

Strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response represents a critical barrier for AAV-mediated gene transfer in canine muscle.11-14 Three serotypes, including AAV-2, 6, and 8 have been evaluated in adult dog muscle. In the absence of immune suppression, none of these serotypes results in high-level transduction. Capsid structure, the nature of the transgene, and animal age are important factors that can modulate immune responses to viral vectors. Here we tested whether switching to a different AAV serotype and/or performing neonatal gene delivery could improve AAV transduction in dog muscle. In particular, we delivered AAV-9, a serotype that has never been studied in canine muscle, to both newborn and young adult dog muscles.

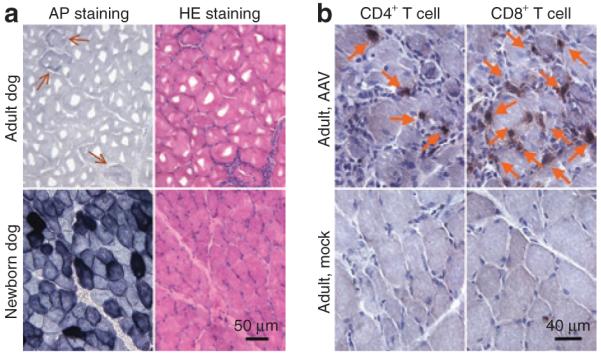

In 6- and 11-month-old dogs, we observed minimal expression after direct muscle injection (Figure 1a, top panels). Immunohistostaining with canine-specific antibodies revealed vigorous CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration in AAV-9 infected muscle but not in HEPES buffer mock-infected muscle (Figure 1b). In contrast, direct injection of the same AAV-9 virus in newborn puppy muscle resulted in robust transduction (Figure 1a, bottom panels). In summary, although switching to AAV-9 did not reduce immune rejection in young adult dog muscle, gene transfer in neonatal puppies seems to have bypassed the immune hurdle.

Figure 1. Local adeno-associated virus-9 (AAV-9) injection leads to robust transduction in neonatal, but not adult, canine muscles.

(a) Representative photomicrographs of alkaline phosphatase (AP) and hematoxylin & eosin (HE) staining after direct muscle injection in the cranial sartorius muscle. [Adult, 4 × 1011 vector genome (vg) particles, 8 weeks after injection; newborn, 1.6 × 1011 vg particles, 10 weeks after injection. N = 2 for each group]. Arrow, rare AP positive myofibers in AAV-9 infected adult dog muscle. (b) Representative photomicrographs of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell immunostaining at 8 weeks after local muscle injection in adult dogs (AAV, 4 × 1011 vg particles; mock, HEPES buffer. N = 2 for each group). Arrow, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

A single intravenous injection in neonatal puppy leads to dose-dependent transduction in skeletal muscle

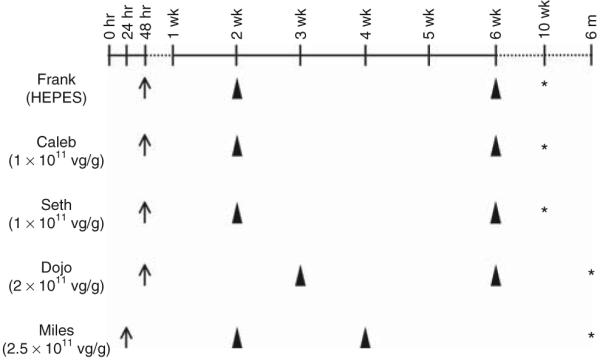

On the basis of the exciting preliminary results from local injection, we next tested whether body-wide gene delivery could be achieved in newborn dogs with AAV-9. In mice, efficient systemic AAV-9 transduction was achieved at the dose range of 0.5 × 1011 to 2 × 1011 vector genome (vg)/g body weight by different groups.6,7,9,10 We performed jugular vein AAV-9 injection in four puppies. Two puppies (Caleb and Seth) were infected at 48 hours after birth with a dose of 1 × 1011 vg/g body weight (Caleb, 425 g at the time of injection; Seth, 446 g at the time of injection). These two dogs were classified as the low-dose group in this article. A third puppy (Dojo, 520 g at the time of injection) was infected at 48 hours after birth with a dose of 2 × 1011 vg/g body weight. The last puppy (Miles, 357 g at the time of injection) was infected at 24 hours after birth with a dose of 2.5 × 1011 vg/g body weight. Dojo and Miles were classified as the high-dose group in this article (Figure 2). We also included two control puppies (both injected at 48 hours after birth). One was injected with vital dye to confirm body-wide perfusion (data not shown). The other (Frank, 387 g at the time of injection) was injected with HEPES buffer to serve as mock-infection control (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic outline of systemic AAV-9 AV.rsV.AP infection in newborn dogs.

Left column shows dog’s name and injection details [adeno-associated virus (AAV) or HEPES buffer, dosage]. Arrow, age at the time of AAV delivery; arrowhead, age at the time of biopsy; asterisk, age at the time of necropsy. vg, vector genome.

Injection in the first three puppies went smoothly without any adverse reaction. However, the puppy (Miles) that was injected at 24 hours after birth with the same batch of viral stock became lethargic and less responsive after AAV injection. After bottle-feeding and subcutaneous fluid supplementation, the condition of the puppy was stabilized. At 2 weeks of age, this puppy survived through anesthesia and surgery uneventfully during muscle biopsy.

As an indirect measure of potential toxicity from systemic AAV-9 infection, we monitored the growth curve. Body weight of AAV-9 infected dogs did not differ from the average of untreated dogs (from ≥50 dogs, J.N. Kornegay, J.R. Bogan, and D.J. Bogan, unpublished results; Supplementary Figure S1).

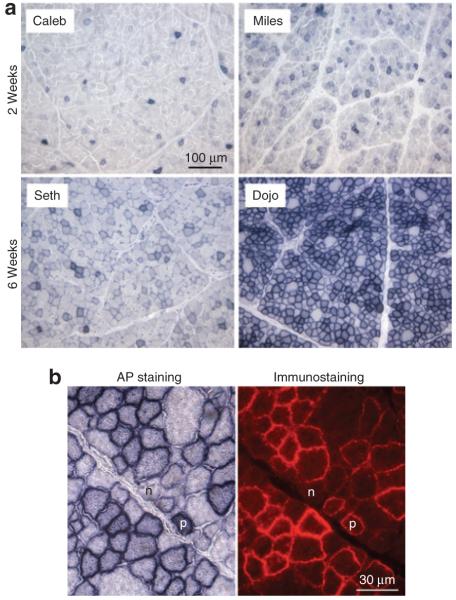

Biopsy at 2 and 6 weeks after infection seemed to show a dose response. On histochemical staining, puppies that received low-dose AAV-9 had fewer AP positive fibers than the ones that were infected with high-dose AAV-9 (Figure 3a). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the histochemical staining results (Figure 3b and data not shown).

Figure 3. Skeletal muscle transduction efficiency correlates with vector dose used in systemic delivery.

(a) Representative photomicrographs of alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining from the cranial sartorius muscles at 2 and 6 weeks after intravenous adeno-associated virus-9 (AAV-9) delivery, respectively. Dog’s name is marked for each panel. Caleb and Seth received 1 × 1011 vector genome (vg)/g body weight AAV-9 AV.RSV.AP. Miles and Dojo were injected with 2.5 × 1011 and 2 × 1011 vg/g body weight AAV-9 AV.RSV.AP, respectively. (b) Confirmation of histochemical staining with immunofluorescence staining. Serial muscle sections from Dojo’s biopsy were stained for AP expression by histochemical (left panel) and immunofluorescence staining (right panel) using a human placental AP specific antibody. p, a myofiber that was transduced by AAV-9; n, a myofiber that was not transduced by AAV-9.

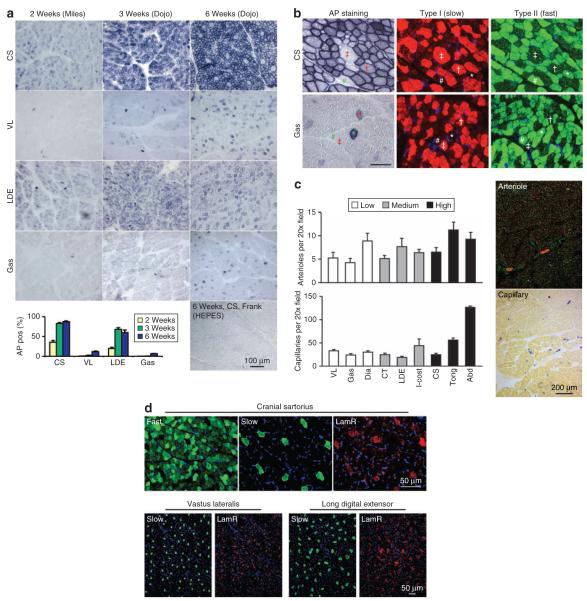

Systemic AAV-9 delivery leads to variable muscle transduction and the muscle-to-muscle difference is independent of the fiber type, microvasculature distribution or AAV-9 receptor, LamR, expression

To better evaluate transduction in different muscles, samples from four muscles were collected at biopsy including the cranial sartorius (CS) muscle, the long digital extensor (LDE) muscle, the vastus lateralis (VL) muscle, and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius (Gas) muscle.18 These include the muscles that are severely affected (CS) or moderately affected (LDE, VL, Gas) in the canine DMD model.19-21 Two muscles (CS, VL) are proximal to the stifle and two muscles (LDE and Gas) are distal to the stifle and they have different functions relative to their roles as extensors and flexors.19,20 Three muscles contain 0-45% of type I (slow-twitch) fiber (LDE, VL and Gas) whereas the CS muscle contains 46-75% type I fiber.22

The CS muscle consistently showed the highest transduction efficiency (Figure 4a). In the high-dose group, it reached 35, 82, and 87% at 2, 3, and 6 weeks after infection, respectively. The LDE muscle showed intermediate transduction efficiency reaching 19, 67, and 60% at the 2, 3, and 6 week time points, respectively. On the other hand, the VL and Gas muscles were poorly transduced (Figure 4a). In the high-dose group, transduction efficiency reached only 12% (VL) and 7% (Gas) at 6 weeks after AAV infection (Figure 4a). A similar pattern was also observed in the low-dose group (data not shown).

Figure 4. Systemic adeno-associated virus-9 (AAV-9) delivery in newborn dogs shows a fiber type, microvasculature, and receptor-independent muscle preference.

(a) Representative photomicrographs of alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining and AP positive cell quantification from the high-dose group (Dojo and Miles) biopsy at 2, 3, and 6 weeks after AAV-9 injection. Biopsy from a mock-infected dog (Frank) served as the negative control. (b) Both slow and fast twitch myofibers were equally transduced by AAV-9. Serial muscle sections were stained for AP expression and fiber type. Cross, a slow fiber transduced by AAV-9; double cross, a slow fiber not transduced by AAV-9; asterisk, a fast fiber transduced by AAV-9; pound sign, a fast fiber not transduced by AAV-9. (c) Quantification of microvasculature density in different canine muscles (left panels) and representative photomicrographs of arteriole staining (red circles in the top right panel) and capillary staining (blue dots in the bottom right panel). Low, muscles that were poorly transduced by AAV-9 at the dose of 1 × 1011 vector genome (vg)/g body weight; medium, muscles that were moderately transduced by AAV-9 at the dose of 1 × 1011 vg/g body weight; high, muscles that were efficiently transduced by AAV-9 at the dose of 1 × 1011 vg/g body weight. Abd, abdominal muscle; CS, cranial sartorius muscle; CT, cranial tibialis muscle; Dia, diaphragm; Gas, gastrocnemius muscle; I-cost, intercostal muscle; LDE, long digital extensor muscle; Tong, tongue; VL, vastus lateralis muscle. Scale bar in each panel applies to all images in the same panel. (d) Representative immunofluorescence staining of AAV-9 receptor laminin receptor (LamR) in the CS, VL, and LDE muscles. LamR is highly enriched in slow-twitch myofibers. Scale bar applies to all the images in the same row.

To understand the mechanisms underlying the diverse transduction profiles, we first examined whether transduction efficiency correlated with fiber type composition. Serial sections from the highly transduced CS muscle and the poorly transduced Gas muscle were immunostained using fiber type-specific antibodies (Figure 4b). In both cases, we observed similar distribution of slow and fast fibers that were either transduced or not transduced (Figure 4b).

Another factor that may contribute to the observed transduction difference is the muscle perfusion. Muscles with more microvasculature may likely receive more AAV vectors and hence show better transduction. We quantified the number of small arterioles and capillaries in different muscles. We did not see a correlation between microvasculature density and AAV transduction efficiency (Figure 4c).

LamR was recently identified as the AAV-9 receptor.23 To further understand the observed muscle-to-muscle differences, we performed immunofluorescence staining on LamR. Interestingly, LamR is enriched in slow-twitch fibers (Figure 4d). Additional studies are needed to fully understand the cellular factors that regulate AAV-9 transduction in dog muscles.

The lack of a cellular immune response results in persistent skeletal muscle transduction after intravenous AAV-9 injection

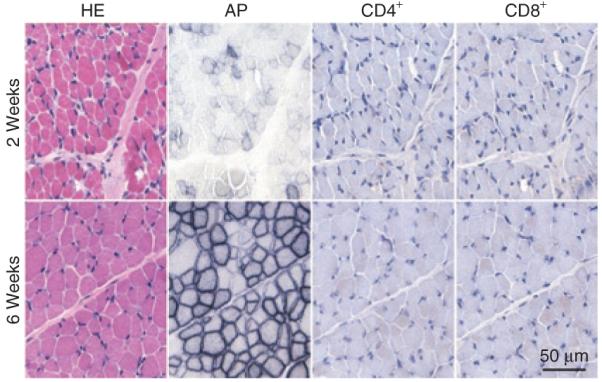

Consistent with our findings in local injection (Figure 1), we did not detect CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration after systemic AAV delivery in newborn dogs (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Systemic adeno-associated virus-9 delivery in neonatal puppies does not induce a cellular immune response.

Representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin & eosin (HE), alkaline phosphatase (AP), CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell staining from 2-week [Miles, infected at 2.5 × 1011 vector genome (vg)/g body weight; top panels] and 6-week (Dojo, infected at 2 × 1011 vg/g body weight; bottom panels) muscle biopsy. Scale bar applies to all images.

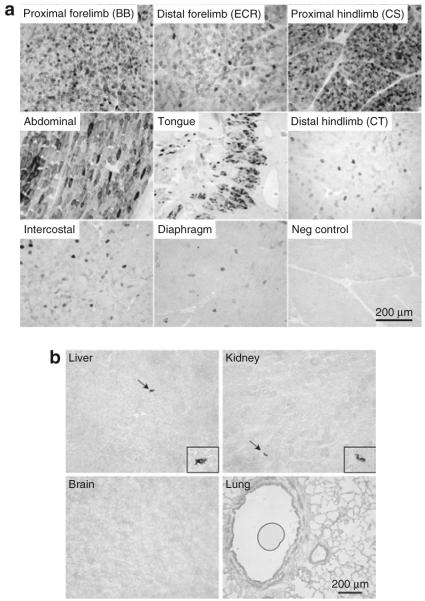

To evaluate long-term transduction efficiency, we performed necropsy at 10 weeks and 6 months after gene delivery in the low-dose and high-dose groups, respectively. At 10 weeks after intravenous AAV-9 injection, we observed highly efficient transduction in several limb muscles (including the biceps brachii muscle and the extensor carpi radialis muscle in the forelimb, and the CS muscle in the hind limb), the abdominal muscle, and the tongue (Figure 6a). In these highly transduced muscles, ≥80% myofibers showed AP expression (Figure 6a). Importantly, robust transduction was observed throughout the entire length of the muscle (proximal, middle, and distal) in the highly transduced limb muscles (Supplementary Figure S2a and b). Consistent with the early time point biopsy results (Figure 4a), some muscles showed intermediate transduction and other muscles were poorly transduced (Figure 6a, Supplementary Figure S2c). The muscles in the intermediate group include the intercostal muscle, the cranial tibialis muscle, LDE muscle, and the long head of the brachial triceps muscle. In these muscles, 20-70% myofibers showed AP expression (Figure 6a, Supplementary Figure S2c). The poorly transduced muscles included the diaphragm, the adductor muscles (Add), the accessory head of the brachial triceps muscle, the rectus femoris muscle, the Gas muscle, the biceps femoris muscle, and the VL muscle. Less than 5% myofibers were AP positive in this group of muscles (Figure 6a, Supplementary Figure S2c). Surprisingly, only a couple of positive cells were detected in the heart (Supplementary Figure S2c). Internal organs (such as the liver, kidney, lung, and brain) were also barely transduced (Figure 6b).

Figure 6. Evaluation of low-dose (1 × 1011 vector genome/g body weight) adeno-associated virus-9 transduction at 10 weeks after intravenous delivery.

(a) Representative photomicrographs of alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining of different skeletal muscles obtained at necropsy from Caleb and Seth. Negative control is from the cranial sartorius muscle of a mock-infected dog (Frank). BB, biceps brachii muscle; CS, cranial sartorius muscle; CT, cranial tibialis muscle; ECR, extensor carpi radialis muscle. (b) Representative photomicrographs of AP staining from selective internal organs. Arrow, rare occurring AP positive cells. Enlarged images are shown in the boxes affiliated with each respective panel.

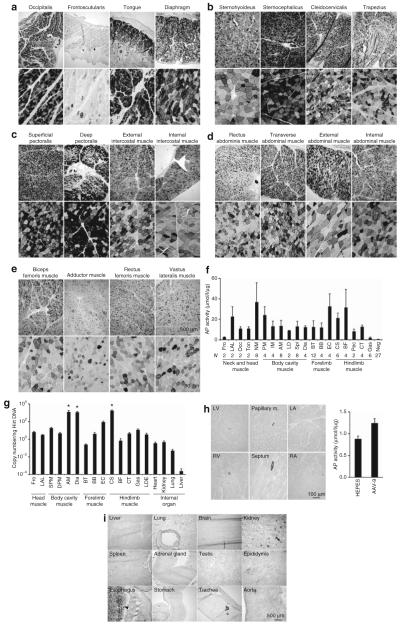

Nearly every skeletal muscle examined at the 6-month necropsy showed efficient AP expression (Figure 7). Representative AP histochemical staining from the tongue, the diaphragm, head, neck, chest, abdominal and limb muscles are shown in Figure 7a-e. In general, >50% myofibers were AP positive. AP activity assays from whole muscle lysates further confirmed histochemical staining results (Figure 7f). Only a few muscles showed relatively low expression. These muscles include the frontoscutularis muscle in the head and the Gas muscle in hind limbs (Figure 7a and f). Interestingly, many muscles that were poorly transduced by low-dose AAV now showed substantial improvement. These muscles are the diaphragm (Figure 7a versus Figure 6a), the biceps femoris, Add, rectus femoris, and VL muscles (Figure 7e versus Supplementary Figure S3c).

Figure 7. Evaluation of high-dose [2× 1011 and 2.5 × 1011 vector genome (vg)/g body weight for dojo and Miles, respectively] adeno-associated virus-9 (AAV-9) transduction at 6 months after intravenous delivery.

(a) Representative photomicrographs of alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining from two representative head muscles, the tongue, and the diaphragm. (b) Representative photomicrographs of AP staining from four representative neck muscles. (c) Representative photomicrographs of AP staining from four representative chest muscles. (d) Representative photomicrographs of AP staining from four representative abdominal muscles. (e) Representative photomicrographs of AP staining from four representative limb muscles. (f) Quantification of AP activity in muscle lysates. N, sample size for each muscle. AM, abdominal muscles (including rectus, transverse, external and internal muscles); BB, biceps brachii muscle; BF, biceps femoris muscle; BT, brachial triceps muscle; CS, cranial sartorius muscle; CT, cranial tibialis muscle; Dia, diaphragm; EC, extensor carpi muscle; Fro, frontoscutularis muscle; Gas, gastrocnemius muscle; IM, intercostal muscles (including both external and internal muscles); LAL, long auricular levator muscle; LD, latissimus dorsi muscle; Neg, 27 skeletal muscles from Frank; NM, neck muscles (including sternohyoideus muscle, sternocephalicus muscle, cleidocervicalis muscle, and trapezius muscle); Occ, occipitalis muscle; Pec, pectineus muscle; PM, pectoral muscles (including both superficial and deep pectoral muscles); Spi, spinate muscles (including both supra and infra muscles); Ton, tongue. (g) Quantification of AAV genome in selected muscles and internal organs. AM, abdominal muscles; BB, biceps brachii muscle; BF, biceps femoris muscle; BT, brachial triceps muscle; CS, cranial sartorius muscle; CT, cranial tibialis muscle; Dia, diaphragm; DPM, deep pectoral muscle; EC, extensor carpi muscle; Fro, frontoscutularis muscle; Gas, gastrocnemius muscle; LAL, long auricle levator muscle; LDE, long digital extensor muscle; SPM, superficial pectoral muscle. (h) Representative photomicrographs of AP staining and AP activity quantification from the heart. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. HEPES, heart sample from Frank (N = 5 samples from different locations of the same heart); AAV-9, heart sample from Dojo and Miles (N = 7 samples from different locations of the heart). (i) Representative photomicrographs of AP staining from some internal organs and smooth muscles. Arrow, positive AP staining in the glomerulus in the kidney; Arrow head, positive AP staining in the skeletal muscle layer of the esophagus. Scale bars in e apply to all images in the respective rows in a to e. Scale bars in g and h only apply to images in that panel.

The dog Miles was infected at 24 hours rather than 48 hours after birth and it received a slightly higher vector dose than the dog Dojo. Interestingly, we did not see an appreciable increase in AP expression from Miles (data not shown).

To determine whether AP expression levels correlate with the AAV genome copy number, we performed quantitative PCR (Figure 7g). The abdominal muscle, diaphragm, and CS muscle contained significantly higher number of the AAV genomes than those in other muscles. Surprisingly, we failed to observe a correlation between the abundance of the vector genome and the transduction level.

Despite efficient skeletal muscle transduction, the myocardium still showed poor AP expression in the high-dose group (Figure 7h, Supplementary Figure S3). In the lysate assay, the heart from AAV-9 infected dogs only had a slightly higher, but not statistically significant, AP activity. In addition, smooth muscles were also poorly transduced (Figure 7i).

Consistent with what we have seen in the low-dose group (Figure 6b), most of the internal organs were poorly transduced in the high-dose group (Figure 7i). The only noticeable difference was in the kidney. The glomeruli of the high-dose group showed strong AP expression (Figure 7i arrow). Interestingly, the detectable AAV vector genome remained low in the kidney (Figure 7g).

DISCUSSION

The demonstration of systemic gene delivery in rodents has raised the hope of whole body correction for many diseases such as DMD.1,3 However, it is also well appreciated that the dramatic body size difference between rodents and large animals is a great challenge to the translation of this technical breakthrough to human patients. To date, studies performed in large animals have been limited to local gene delivery or regional limb perfusion.11,12,24-26 These methods are either clinically not practical or are associated with severe hemodynamic consequences or other side effects. Further, these approaches cannot reach deep tissues that are critical for phenotypic improvement (for example, the diaphragm in DMD). Here, we described the first successful body-wide skeletal muscle transduction in newborn dogs. With a single intravenous AAV-9 injection at the dose equal to or higher than 2 × 1011 vg/g body weight, we observed robust and persistent expression in nearly every skeletal muscle in the dog body.

Dogs are commonly used large animal models for studying human diseases (such as hemophilia, glycogen storage diseases, and inherited blindness). Dog models are particularly attractive for developing DMD therapy. DMD is caused by dystrophin gene mutation. However, the consequence of dystrophin deficiency differs greatly among species. Dystrophin-null mice are only mildly affected and they still live a near normal life span.27 In contrast, dystrophin-deficient dogs display a whole panel of characteristic clinical features similar to human patients such as muscle wasting, growth retardation, and premature death. Therapies developed on the canine model will be much more appealing from a translational standpoint.

Despite the clinical relevance and importance, AAV gene transfer in dog muscle has been disappointing. Of three AAV serotypes that have been tested (AAV-2, 6, and 8), all have largely failed to achieve efficient transduction. Strong T cell-mediated immune reaction to either the transgene product and/or AAV capsid protein essentially eliminates transduced cells in canine muscle.11-14 The use of muscle-specific promoter and canine transgene has led to some improvement but does not solve the problem. Currently, the most effective approach is to apply transient immunosuppression.13,14 A regimen that does not require immunosuppression would be more desirable.

The age at the time of gene delivery is an important factor in vector-associated immune responses. Newborn animals may not mount a vigorous immune response because of their immature immune system. Besides the immunological reason, there is actually a clinical need for developing neonatal gene therapy to treat diseases such as DMD. Traditionally, DMD patients are diagnosed between 2 and 5 years of age when they cannot reach motor skill milestones.28 At this time, the muscle disease has already resulted in clinically evident damage. Therapies initiated after this time may have missed the best treatment window. Highly sensitive, reproducible, and affordable neonatal screening methods have been developed for neonatal DMD diagnosis.29 The possibility of identifying newborn DMD patients opens the likelihood of an early intervention.

We compared local and/or systemic AAV-9 transduction in adult and/or newborn dogs. In our vector, the ubiquitous viral promoter (RSV) was used to express an immunogenic human placental AP protein.12 AAV-9 has not been studied in canine muscle. Our results suggest that, like AAV-2, 6, and 8, AAV-9 also induces strong cellular immune response in adult dog muscle (Figure 1). However, local and systemic gene delivery in neonatal dogs resulted in robust and persistent expression up to 6 months (the duration of the study). We did not detect CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration, even at a dose that effectively transduced almost every muscle in the body (Figure 5). Furthermore, systemic AAV-9 injection did not alter normal growth (Supplementary Figure S1).

The absence of a strong cellular immune response in neonatal dogs is a quite encouraging finding. Walter et al. have previously used this approach to achieve successful re-administration of an adenovirus vector in adult mice.30 Further development of this technique may lead to a clinically applicable therapeutic modality in the future.

The only adverse reaction we encountered was in the dog Miles. This dog received the highest amount of AAV vector and the largest fluid volume. In addition, this dog was injected at the earliest time point (24 hours after birth). These manipulations did not lead to an appreciable increase in transduction efficiency (data not shown). On the contrary, we observed a seemingly toxic response to AAV administration. Although this dog eventually recovered, it does point out that one of the gene delivery parameters used for this dog (such as viral load, fluid load, and dog age) may have reached the safety threshold.

Our study also revealed several surprising findings. First, there is a dramatic muscle-to-muscle difference in transduction efficiency (Figures 4a, 6a, and 7a-f, Supplementary Figure S2). We have previously shown that AAV-9 preferentially transduces fast twitch fibers in mice.10 However, we did not see a fiber-type correlation in dog muscle despite an enriched expression of AAV-9 receptor LamR in slow-twitch fibers (Figure 4b and d). Furthermore, microvasculature quantification suggests that the difference in transduction efficiency is unlikely due to differences in muscle perfusion (Figure 4c). Further studies are needed to determine the biological nature of muscle transduction variance in dogs. Nevertheless, muscles that were poorly transduced at the low dose had better expression at the high dose (Figure 7e).

The second surprise is the extremely poor transduction of internal organs and smooth muscle. Except for the kidney, we barely detected any AP positive cells in the liver, lung, brain, spleen, adrenal gland, testis, epididymis, and smooth muscles of different organ origins (such as the stomach and aorta) (Figures 6b and 7h). This is different from what we have seen in mice. The newborn mouse lungs (especially the alveolar cells and vasculature) are highly transduced by AAV-9.9,10 Transduction in the liver and smooth muscles is not as high as in the lung but can be easily detected in mice. The glomeruli transduction is quite interesting. A kidney isoform of dystrophin (Dp140) has been shown to be primarily expressed at the glomerular basement membrane.31 It has also been suspected that DMD patients may suffer from subtle renal problems. Additional studies are needed to determine whether the unique glomeruli transduction could benefit DMD patients.

Perhaps, the most surprising observation is the extremely low transduction of the heart (Figures 6b and 7g, Supplementary Figure S3). Even at the high dose (2 × 1011 to 2.5 × 1011 vg/g body weight) and after a long incubation (6 months), we could barely find one positive cardiomyocyte in the entire section or whole mount tissue staining (Figure 7g, Supplementary Figure S3). AAV-9 has been considered as a cardiotropic vector because it can lead to extraordinarily robust expression in the hearts of mice and primates.6,7,9,10 It is quite interesting to see the other extreme in the canine heart. Future studies comparing the differences between the dog heart and the mouse heart may shed light on the cellular mechanisms of AAV-9 transduction.

One caveat of the current study is the small sample size. With only two dogs in each dose group, additional studies are apparently needed to further corroborate the exciting preliminary observations presented here. There is no doubt that a more important issue is to determine whether systemic gene delivery is achievable in dystrophic dogs.

Scaling up is a significant obstacle in translating murine gene therapy protocols to human patients. Here, we present the first evidence that a single intravenous injection of AAV-9 can efficiently transduce nearly all skeletal muscles in a large animal. Our results suggest that body size may not be a barrier for intravascular AAV gene transfer. Over the past few years, tremendous progress has been made in AAV capsid modification. The method described here can be adapted to evaluate systemic gene delivery with capsids other than AAV-9 in large animals in the future. The minimally invasive nature of the procedure and the widespread skeletal gene transfer described here should allow for immediate testing of different AAV gene therapy strategies in canine DMD models. Further development of this technology may lead to whole body correction for many diseases including DMD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Missouri and Auburn University and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide-lines. Normal beagle and golden retriever/beagle cross dogs were used in the study. Dogs were housed in kennels certified by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Neonatal puppies were produced by in-house breeding.

Recombinant AAV-9 vector

AAV-9 vectors (AV.RSV.AP) were produced using a previously reported triple plasmid transfection protocol.9,10 The cis-plasmid (pcisRSV.AP) for AAV production was published previously.32 The AAV-9 packaging plasmid pRep2/Cap9 was a gift from Dr James Wilson at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA).33,34 Recombinant viral stocks were purified through three rounds of isopycnic CsCl ultracentrifugation followed by three changes of HEPES buffer at 4 °C for 48 hours. Viral titer and quality control were performed according to our previously published protocol.35 Endotoxin contamination was examined using the limulus amebocyte lysate assay using the Endosafe limulus amebocyte lysate gel clot test kit (Charles Rivers Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). The endotoxin levels in our viral stocks were within the acceptable level recommended by the Food and Drug Administration.

Gene delivery, biopsy, and necropsy

Direct muscle injection of AAV-9 was performed in the CS muscle of neonatal (2-day-old, N = 2) and young adult (6- and 11-month-old, N = 1 for each age) dogs under isoflurane anesthesia. After muscle was exposed, AAV-9 (4 × 1011 vg particles in 0.5 ml for young adult dogs and 1.6 × 1011 vg particles in 0.1 ml for neonatal puppies) was injected into the muscle belly. Injection sites were marked with sutures. Systemic injection was performed in conscious puppies by a single bolus injection of AAV-9 through the jugular vein (details of the injection volume and amount of AAV-9 particles are described in the Results section). The same AAV vector stock was used in every dog for systemic delivery. Biopsy was performed at 8 and 10 weeks after local injection and 2, 3, 4, and 6 weeks after intravenous infection according to a previously described protocol.36 Four different muscles were sampled in dogs that received systemic gene transfer (the CS muscle, the LDE muscle, the VL muscle, and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle). Each dog was biopsied twice, with the opposite limb sampled during the second surgery. Necropsy was performed at 10 weeks or 6 months after intravenous injection (see Results section for details). Dogs were euthanized with sodium pentobarbital. Skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, smooth muscle, and internal organs were collected at necropsy. Skeletal muscles included five muscles of the head (the occipitalis, frontoscutularis, long auricular levator and temporalis muscles, and the tongue), four neck muscles (the sternohyoideus, sternocephalicus, cleidocervicalis, and trapezius muscles), four chest muscles (the superficial and deep pectoral muscles, the external and internal intercostal muscles), the diaphragm (including eight samples from peripheral and central parts on the anterior, posterior, left and right sides, respectively), two shoulder muscles (the supra and infra spinatus muscles), four abdominal muscles (the rectus, external oblique, internal oblique, and transverses muscles), the gluteus muscle, the latissimus dorsi muscle, 15 hind limb muscles (the CS, caudal sartorius, biceps femoris, VL, vastus intermediates, rectus femoris, adductor, pectineus, semi-membranous, semitendinous, gracilis, cranial tibialis, LDE, the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius muscles), 7 forelimb muscles (the long, accessory, medial and lateral heads of the triceps brachii, biceps brachii, extensor carpi radialis, and superficial digital flexor muscles). Both the left and right side muscles were collected. For each limb muscle, three samples were collected from the proximal end, middle belly, and the distal end. For the heart, we collected samples from the left and right ventricles, the left and right atria, the septum, and the papillary muscle. For smooth muscle, we collected samples from the esophagus (proximal, middle, and distal ends), stomach, aorta and vena cava. Internal organs harvested at necropsy included the liver, lung, trachea, brain, kidney, spleen, adrenal gland, testis, and epididymis.

Reporter gene evaluation

Three methods were used to determine human placental AP gene expression. Histochemical staining was performed on 8-μm cryosections and whole mount tissue samples after inactivating endogenous heat labile AP.9 Immunofluorescence staining was performed with a monoclonal antibody (clone 8B6, 1:8,000; Sigma, St Louis, MO). The enzyme activity in muscle lysate was measured using a StemTAG AP activity assay kit from Cell Biolabs (San Diego, CA).

Other morphology studies

Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used for immunohistochemical detection of the cellular immune response in tissue sections. Canine-specific anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies (both at 1:1,000 dilution) were obtained from AbD Serotec (Raleigh, NC). Small arterioles were identified by immunofluorescence staining using a monoclonal anti-smooth muscle α-actin antibody (clone 1A4, 1:2,000; Sigma, St Louis, MO). Capillaries were revealed using an AP-metanil yellow staining protocol described previously.37 The AAV-9 receptor [laminin receptor (LamR)] was detected by immunofluorescence staining using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Quantitative PCR

Low-molecular weight DNA was isolated using a modified Hirt protocol. Briefly, 100-mg tissue was minced using a razor blade and then resuspended in 100 μl Wizard resuspension buffer (Wizard Plus SV minipreps; Promega, Madison, WI). Tissue was homogenized in a buffer containing a mixture of 400 μl Hirt lysis buffer (100 mmol/l Tris pH 8.0, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 50 mol/l EDTA) and 200 μl reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Tissue lysate was then digested with proteinase K (1 μg/μl final concentration) and pronase (0.5 μg/μl final concentration) for 2 hours. After adding 80 μl 5 mol/l NaCl, tissue lysate was incubation at 4 °C for 2 hours. 250 μl Promega neutralizing solution (Wizard Plus SV minipreps; Promega) was added to each sample and mixed thoroughly by vortexing. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,700g for 35 minutes. Finally, low-molecular weight DNA was eluted using a DNA miniprep column (Wizard Plus SV minipreps; Promega).

The AAV genome copy in low-molecular weight DNA (2 μl) was determined by quantitative PCR in an ABI 7900 HT QPCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The primers were located within the RSV promoter. The forward primer is DL553, 5′-GGTTGTACGC GGTTAGGAGT-3′. The reverse primer is DL554, 5′-GGCATGTTGCT AACTCATCG-3′. PCR was performed using a SYBR green QPCR master mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) in triplicate. The threshold cycle (Ct) value was converted to copy number by measuring against the copy number standard curve of known amount of pcisRSV.AP plasmid. The copy number was normalized by DNA concentration.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes Health AR-49419 and AR-57209 (D.D., B.F.S.), NS-62934 (D.D.), and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (D.D., J.N.K., B.F.S.). D.D. and Y.Y. formulated the idea. D.D., J.N.K., and B.F.S. designed experiments. D.D. drafted the manuscript. J.N.K., B.F.S., B.B., and A.G. edited the manuscript. All authors performed experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gregorevic P, Blankinship MJ, Allen JM, Crawford RW, Meuse L, Miller DG, et al. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blankinship MJ, Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Harper SQ, Harper H, Halbert CL, et al. Efficient transduction of skeletal muscle using vectors based on adeno-associated virus serotype 6. Mol Ther. 2004;10:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, Zhu T, Qiao C, Zhou L, Wang B, Zhang J, et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nbt1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mah C, Cresawn KO, Fraites TJ, Jr., Pacak CA, Lewis MA, Zolotukhin I, et al. Sustained correction of glycogen storage disease type II using adeno-associated virus serotype 1 vectors. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1405–1409. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denti MA, Rosa A, D’Antona G, Sthandier O, De Angelis FG, Nicoletti C, et al. Body-wide gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3758–3763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508917103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inagaki K, Fuess S, Storm TA, Gibson GA, McTiernan CF, Kay MA, et al. Robust systemic transduction with AAV9 vectors in mice: efficient global cardiac gene transfer superior to that of AAV8. Mol Ther. 2006;14:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacak CA, Mah CS, Thattaliyath BD, Conlon TJ, Lewis MA, Cloutier DE, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 leads to preferential cardiac transduction in vivo. Circ Res. 2006;99:e3–e9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237661.18885.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Minami E, Blankinship MJ, Haraguchi M, Meuse L, et al. rAAV6-microdystrophin preserves muscle function and extends lifespan in severely dystrophic mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:787–789. doi: 10.1038/nm1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh A, Yue Y, Long C, Bostick B, Duan D. Efficient whole-body transduction with trans-splicing adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2007;15:750–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bostick B, Ghosh A, Yue Y, Long C, Duan D. Systemic AAV-9 transduction in mice is influenced by animal age but not by the route of administration. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1605–1609. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzog RW, Mount JD, Arruda VR, High KA, Lothrop CD., Jr. Muscle-directed gene transfer and transient immune suppression result in sustained partial correction of canine hemophilia B caused by a null mutation. Mol Ther. 2001;4:192–200. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Allen JM, Riddell SR, Gregorevic P, Storb R, Tapscott SJ, et al. Immunity to adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer in a random-bred canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:18–26. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Kuhr CS, Allen JM, Blankinship M, Gregorevic P, Chamberlain JS, et al. Sustained AAV-mediated dystrophin expression in a canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy with a brief course of immunosuppression. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1160–1166. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuasa K, Yoshimura M, Urasawa N, Ohshima S, Howell JM, Nakamura A, et al. Injection of a recombinant AAV serotype 2 into canine skeletal muscles evokes strong immune responses against transgene products. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1249–1260. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day MJ. Immune system development in the dog and cat. J Comp Pathol. 2007;137(suppl 1):S10–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mingozzi F, High KA. Immune responses to AAV in clinical trials. Curr Gene Ther. 2007;7:316–324. doi: 10.2174/156652307782151425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh A, Duan D. Expending adeno-associated viral vector capacity: a tale of two vectors. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2007;24:165–177. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2007.10648098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goody PC. Dog Anatomy: A Pictorial Approach to Canine Structure. Allen; London: 1997. p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Childers MK, Okamura CS, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Sullivan MJ, Kornegay JN. Myofiber injury and regeneration in a canine homologue of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:175–181. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornegay JN, Cundiff DD, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Okamura CS. The cranial sartorius muscle undergoes true hypertrophy in dogs with golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2003;13:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(03)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen F, Cherel Y, Guigand L, Goubault-Leroux I, Wyers M. Muscle lesions associated with dystrophin deficiency in neonatal golden retriever puppies. J Comp Pathol. 2002;126:100–108. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller ME, Evans HE. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog. 3rd edn. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1993. p. 1113. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, Yant SR, Xu H, Kay MA. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J Virol. 2006;80:9831–9836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzog RW, Yang EY, Couto LB, Hagstrom JN, Elwell D, Fields PA, et al. Long-term correction of canine hemophilia, B by gene transfer of blood coagulation factor IX mediated by adeno-associated viral vector. Nat Med. 1999;5:56–63. doi: 10.1038/4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arruda VR, Stedman HH, Nichols TC, Haskins ME, Nicholson M, Herzog RW, et al. Regional intravascular delivery of AAV-2-F.IX to skeletal muscle achieves long-term correction of hemophilia B in a large animal model. Blood. 2005;105:3458–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su LT, Gopal K, Wang Z, Yin X, Nelson A, Kozyak BW, et al. Uniform scale-independent gene transfer to striated muscle after transvenular extravasation of vector. Circulation. 2005;112:1780–1788. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.534008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamberlain JS, Metzger J, Reyes M, Townsend D, Faulkner JA. Dystrophin-deficient mdx mice display a reduced life span and are susceptible to spontaneous rhabdomyosarcoma. FASEB J. 2007;21:2195–2204. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7353com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emery AEH, Muntoni F. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. 3rd edn. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 2003. p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flanigan KM, von Niederhausern A, Dunn DM, Alder J, Mendell JR, Weiss RB. Rapid direct sequence analysis of the dystrophin gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:931–939. doi: 10.1086/374176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter J, You Q, Hagstrom JN, Sands M, High KA. Successful expression of human factor IX following repeat administration of adenoviral vector in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3056–3061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lidov HG, Kunkel LM. Dp140: alternatively spliced isoforms in brain and kidney. Genomics. 1997;45:132–139. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yue Y, Li Z, Harper SQ, Davisson RL, Chamberlain JS, Duan D. Microdystrophin gene therapy of cardiomyopathy restores dystrophin-glycoprotein complex and improves sarcolemma integrity in the mdx mouse heart. Circulation. 2003;108:1626–1632. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089371.11664.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao G, Alvira MR, Somanathan S, Lu Y, Vandenberghe LH, Rux JJ, et al. Adeno-associated viruses undergo substantial evolution in primates during natural infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6081–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937739100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, et al. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai Y, Yue Y, Liu M, Ghosh A, Engelhardt JF, Chamberlain JS, et al. Efficient in vivo gene expression by trans-splicing adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1435–1439. doi: 10.1038/nbt1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kornegay JN, Tuler SM, Miller DM, Levesque DC. Muscular dystrophy in a litter of golden retriever dogs. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:1056–1064. doi: 10.1002/mus.880111008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prior BM, Yang HT, Terjung RL. What makes vessels grow with exercise training? J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1119–1128. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00035.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.