Abstract

Objective

To assess differences between the risk of injury for motorcycle riders before and after the passing of a law allowing licenced car drivers to drive light motorcycles without having to take a special motorcycle driving test.

Methods

We carried out a quasi-experimental study involving comparison groups, and a time-series analysis from 1 January 2002 to 30 April 2008. The study group was composed of people injured while driving or riding a light motorcycle (engine capacity 51–125 cubic centimetres), while the comparison groups consisted of riders of heavy motorcycles (engine capacity > 125 cc), mopeds (engine capacity ≤ 50 cc) or cars who were injured in a collision within the city limits. The “intervention” was a law passed in October 2004 allowing car drivers to drive light motorcycles without taking a special driving test. To detect and quantify changes over time we used Poisson regression, with adjustments for trend and seasonality in road injuries and the existence of a driver’s licence penalty point system.

Findings

The risk of injury among light motorcycle riders was greater after the law than before (relative risk, RR = 1.46; 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.34–1.60). Although less markedly, after the law the risk of injury also increased among heavy motorcycle drivers (RR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.02–1.29) but remained unchanged among riders of mopeds (RR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.83–1.01) and cars (RR = 1.06; 95% CI: 0.97–1.16).

Conclusion

Allowing car drivers to drive motorcycles without passing a special test increases the number of road injuries from motorcycle accidents.

Résumé

Objectif

Evaluer les variations du risque de blessure par accident pour les conducteurs de motocycles avant et après le vote d’une loi autorisant les titulaires d’un permis auto à conduire des motocycles légers sans passer une épreuve de conduite spéciale pour les motocycles.

Méthodes

Nous avons effectué une étude quasi-expérimentale sur des groupes de comparaison et une analyse de série temporelle entre le 1er janvier 2002 et le 30 avril 2008. Le groupe étudié était composé de personnes accidentées pendant la conduite ou le transport sur un motocycle léger (cylindrée 51-125 cm³), tandis que les groupes de comparaison étaient composés d’utilisateurs de motocycles lourds (cylindrée > 125 cm³), de mobylettes (cylindrée ≤ 50 cm³) ou d’automobiles, victimes d’une collision en ville. L’«intervention» résidait dans le vote d’une loi en octobre 2004, autorisant les conducteurs automobiles à conduire des motocycles légers sans passer d’épreuve de conduite spéciale. Pour détecter et quantifier les changements au cours du temps, nous avons utilisé une régression de Poisson, en pratiquant des ajustements pour tenir compte des tendances et de la saisonnalité des accidents de la circulation, ainsi que de l’existence d’un système de permis à points.

Résultats

Le risque de blessure par accident chez les conducteurs de motocycles légers était plus élevé après le vote de la loi qu’auparavant (risque relatif, RR = 1,46 ; intervalle de confiance à 95%, IC : 1,34-1,60). Bien que de façon moins marquée, le risque d’accident avait également augmenté après ce vote chez les conducteurs de motocycles lourds (RR = 1,15 ; IC à 95% : 1,02-1,29), mais était resté inchangé chez les conducteurs de mobylettes (RR = 0,92 ; IC à 95% : 0,83-1,01) et d’automobiles (RR = 1,06 ; IC à 95% : 0,97-1,16).

Conclusion

Le fait d’autoriser les conducteurs automobiles à conduire des motocycles sans passer d’épreuve de conduite spéciale entraîne une augmentation du nombre de blessés par accident de la circulation parmi les motocyclistes.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar las diferencias en el riesgo de lesión de tráfico entre los motociclistas antes y después de la aprobación de una ley que autoriza a las personas con permiso de conducción de automóviles conducir también motocicletas ligeras sin necesidad de superar un examen especial para el uso de motocicletas.

Métodos

Llevamos a cabo un estudio cuasiexperimental con grupos de comparación y un análisis de series temporales entre el 1 de enero de 2002 y el 30 de abril de 2008. El grupo de estudio estaba compuesto por usuarios de motocicletas ligeras (cilindrada de 51-125 cc) que habían sufrido una lesión de tráfico, y los grupos de comparación consistían en usuarios de motocicletas pesadas (cilindrada > 125 cc), ciclomotores (cilindrada ≤ 50 cc) o turismos que habían sufrido una lesión de tráfico en la ciudad de Barcelona. La «intervención» fue una ley aprobada en octubre de 2004 por la que se permitía a los conductores de turismo conducir también motocicletas ligeras sin la condición de superar un examen especial. Para detectar y cuantificar los cambios ocurridos a lo largo del tiempo se utilizó la regresión de Poisson, ajustando los datos en función de la tendencia y la estacionalidad de las lesiones de tráfico y de la introducción de un permiso de conducción por puntos.

Resultados

El riesgo de lesiones entre los usuarios de motocicletas ligeras aumentó tras la aprobación de la ley (riesgo relativo, RR = 1,46; intervalo de confianza del 95%, IC95%: 1,34–1,60). Aunque de forma menos marcada, después de la ley, el riesgo de lesiones también aumentó entre los conductores de motocicletas pesadas (RR = 1,15; IC95%: 1,02–1,29), pero se mantuvo entre los usuarios de ciclomotores (RR = 0,92; IC95%: 0,83–1,01) y turismos (RR = 1,06; IC95%: 0,97–1,16).

Conclusión

Facilitar el acceso a motocicletas a los conductores de turismos sin necesidad de superar antes un examen especial aumenta el número de lesionados de tráfico que implican motocicletas.

ملخص

الهدف

تقيـيم الفروق بين عامل اختطار الإصابات لدى سائقي الدراجات النارية قبل وبعد تمرير قانون يسمح لسائقي السيارات الذين يحملون رخصاً للقيادة، بقيادة الدراجات النارية الخفيفة دون الخضوع لاختبار خاص لقيادة الدراجات النارية.

الطريقة

أجرى الباحثون دراسة شبه تجريبية شملت مجموعات للمقارنة مع تحليل بحسب التسلسل الزمني، من الأول من كانون الثاني/يناير 2002 وحتى 30 نيسان/أبريل 2008. وقد تألف فريق الدراسة من المصابين أثناء قيادتهم أو ركوبهم دراجات نارية خفيفة (سعة المحرك 51 – 125 سنتيمتر مكعب)، أما المجموعات المقارنة فتـتألف من راكبين لدراجات نارية ثقيلة (تزيد سعة المحرك فيها عن 125 سنتيمتر مكعب) وخفيفة جداً (سعة المحرك 50 سنتيمتر مكعب أو أقل) أو راكبي سيارات تعرضوا لإصابات في اصطدامات ضمن حدود المدينة، أما “التدخل” فكان تمرير قانون في تشرين الأول/أكتوبر 2004 يسمح لسائقي السيارات بقيادة الدراجات النارية الخفيفة دون خضوعهم لاختبار خاص لقيادتها. ولكشف التغيرات الكمية بمرور الوقت، استخدم الباحثون تحوف بواسون مع تعديلات للنزعات ولموسمية الإصابات على الطرق، وفي ظل وجود نظام لنقاط عقوبات يطبَّق على رخص السائقين.

النتائج

لقد كان اختطار الإصابة لدى سائقي الدراجات النارية الخفيفة، بعد تمرير القانون،أكثر منه قبل تمريره (الاختطار النسبي 1.46، فاصلة الثقة 95 وتراوحت بين 1.34 – 1.60). ورغم أن اختطار الإصابة كان أكبر بشكل ملحوظ بعد القانون لدى سائقي الدراجات النارية الثقيلة (الاختطار النسبي 1.15، بفاصلة ثقة 95% وتراوحت بين 1.02 و1.29)، إلا أنه لم يتغير بين راكبي الدراجات الخفيفة جداً (الاختطار النسبي 0.92 بفاصلة ثقة 95 تراوحت 0.83 و1.01). ولا بين راكبي السيارات (الاختطار النسبي 1.06 وبفاصلة ثقة 95% تراوحت بين 0.97 و1.16).

الاستنتاج

إن السماح لسائقي السيارات بقيادة الدراجات النارية دون اجتيازهم لاختبار خاص، يزيد من عدد الإصابات على الطرق بسبب حوادث الدراجات النارية.

Introduction

Road traffic injuries are a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with pedestrians and riders of two-wheeled motor vehicles being the most vulnerable.1 In Europe, 41 247 road traffic deaths occurred in 2005,2 and 21.1% of them were among two-wheeled motor vehicle users.3 In 2005, the number of fatalities among motorcyclists in European Union countries was 22% higher than in 1996, while deaths related to other modes of transportation declined: 37% among pedestrians; 42% among cyclists; 41% among moped riders, and 28% among car riders.4 In Spain, motorcycles represented approximately 7.2% of all motor vehicles in 2005,5 and 8.4% of all road traffic fatalities occurred among motorcyclists. Although motorcycle fatalities had decreased progressively to 7.4% of all road traffic injury cases between 19986 and 2004,7 a dramatic increase of 29.8% was reported from 2006 to 2007.8

Until September 2004, drivers of large motorcycles (engine capacity > 125 cubic centimetres) in Spain had to obtain a permit that required passing a written test on the way to drive a motorcycle and on traffic regulations, as well as a road test. In October 2004, a new national law was passed allowing car drivers in possession of a driver’s licence for at least 3 years to drive a light motorcycle (engine capacity 51−125 cc) without an additional licence or test. Similar laws had previously been passed in other European countries, but no studies of their effect have been published except for one from 1997–1999 that looked for an association between motorcycle licensing laws and mortality rates.9 The authors found that licensing requirements specifically for motorcycle drivers (such as a road test, driver education, or the use of a full helmet) were associated with lower mortality rates.

Barcelona, with 1.6 million inhabitants, is the capital of the region of Catalonia, in north-eastern Spain. Motorcycles are a very popular form of transportation in the city, perhaps because of the mild Mediterranean climate and the high traffic density. In 2005, there were 163 motorcycles per 1000 inhabitants – more than in Rome (161), Madrid (30) or London (20). Every year since 1998, more than 10 000 motor vehicles have collided within the city limits, and as a result around 13 000 people suffer injuries and 50 are killed. In 2005, 28% of those injured on the road were car riders; 27%, motorcyclists; 25%, moped users; 13%, pedestrians; 2.4%, cyclists, and 4,6%, riders of other vehicles. The injury severity score (ISS), provided by the city emergency surveillance system, was higher for motorcyclists and pedestrians than for car riders. Moderate injuries were suffered by 15.4% of motorcyclists and severe injuries, by 1.7%. By contrast, such injuries occurred in 13.7% and 1.8% of moped riders, 23.7% and 3.4% of pedestrians, and 5.8% and 0.4% of car riders, respectively.

The objective of this study was to assess the association between the number of motorcycle injuries in Barcelona and the new law requiring no special licence for drivers of light motorcycles in possession of a car driver’s licence for at least 3 years. We hypothesize that allowing car drivers to drive light motorcycles without a special licence increases the risk of injuries involving this type of vehicle.

Methods

Study design and population

The study design was quasi-experimental and consisted of a retrospective, controlled time-series analysis with Poisson regression. The study group was composed of people injured while driving or riding a light motorcycle, while the comparison group consisted of drivers or passengers of heavy motorcycles, mopeds or cars who suffered injury in a collision within the city limits. Injured pedestrians or people who suffered no injury were excluded from the analysis.

Study period

The study covers two periods of 3 years. The period before enforcement of the new law runs from 1 January 2002 to 30 September 2004, and the period following runs from 1 October 2004 to 30 April 2008. Data were obtained from the city police registry of traffic collisions. In Barcelona, the city police has a special traffic collision department that ensures comprehensive coverage of all crashes in which people are injured. Specially trained officers use a standardized form to draw up a report for all crashes involving property damage or human injury, and included is information about the vehicle driver, the individuals injured, the vehicle involved in the collision and the circumstances in which the collision occurred.

Some cases with inconsistent data were excluded from the analysis. For example, 22 161 injured individuals were reported as being motorcyclists, yet 284 of their records showed the vehicle brand and model of a moped and 76, those of a car. On the other hand, 32 992 individuals were reported as riders of vehicles other than motorcycles, yet for 1302 (3.9%) of them the vehicle brand and model listed were those of a light motorcycle, and for 63 (0.5%), those of a heavy motorcycle. These cases were included in the analysis according to vehicle brand and model because this information was more specific and thus more likely to be correct than the “type of vehicle”, for which selecting a word from a list is all that was required.

The number of newly registered motorcycles was obtained from the Institut Municipal d’Estadística (Barcelona’s municipal statistics bureau)10 for the period from 1 January 2002 to 30 September 2007.

Variables

The outcome measure was the number of people injured or killed. Deaths were not analysed separately because the figures were too low for a time-series analysis (6 in 2002, 16 in 2003, 12 in 2004, 17 in 2005, 21 in 2006 and 17 in 2007).

Motorcycles were classified by brand, model and engine capacity. Light motorcycles were defined as having an engine capacity of 51–125 cc, and heavy motorcycles as having an engine capacity > 125 cc. Due to lack of detailed information, 21.3% of the motorcycles recorded could not be classified. Mopeds were defined as having an engine capacity ≤ 50 cc.

A penalty point system for driving offences was introduced in Spain on 1 July 2006. The potential effect of this measure was controlled for in the model.

Statistical analysis

Poisson regression models were used to analyse the time series of outcomes, previously defined. Adjustments were made for trend and seasonal patterns by means of a linear combination of sine and cosine functions.11 After adjustment, an intervention analysis was carried out by fitting a dummy variable to compare the pre- and post-law periods. Thus, the model for each outcome can be summarized as follows:

| ln[E(Yt)] = b0 + [b1 × t] + [b2 × sin(2πt/T)] + [b3 × cos(2πt/T)] + [b4 × Xt] |

where Y is the observation vector; T is the number of time periods described by each sinusoidal function (e.g. for 12 months, T = 12); t is the time period (e.g. t = 1 for January, t = 2 for February, t = 3 for March, etc.); Yt is the observation for each time period t; E(Yt) is the expected value of Yt; Xt = 1 identifies the post-intervention period; Xt = 0 identifies the pre-intervention period; b0 is the intercept, and b1, b2, b3 and b4 are the model coefficients associated with the variables t, sin(2πt/T), cos(2πt/T) and Xt, respectively.

The relative risk (RR) of injury per type of vehicle in the post-law period was determined, after adjustment for time trend and seasonality, both for the period as a whole and for each year. The trend in the number of injuries from month to month before and after the law was passed was also determined, together with the difference in trend between both periods. The attributable fraction, AF – proportion of injuries attributable to the collisions – was derived with the following equation12:

| AF = (RR – 1) / RR |

The expected number of people injured had the law not been passed was calculated from the adjusted models.

The dependent variables were the numbers of those injured as riders of light motorcycles, heavy motorcycles, mopeds and motorcycles with engines of unknown cubic capacity. The trend was not statistically significant for light motorcycles, so the final model was not adjusted for it. The penalty points system was not significantly associated with any dependent variable and was therefore not included in the models either. Models were also fitted after adjustment for the number of newly registered motorcycles.

Statistical analyses were carried out with Stata statistical software, version 10.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, United States of America).

Results

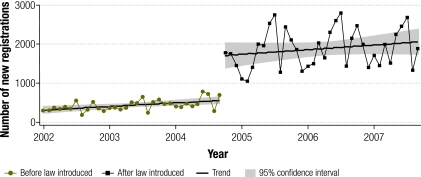

During the period before the new law went into effect, the mean number of people injured in light motorcycle collisions showed a non-significant decreasing trend, while in the period after the law a significant increasing trend was noted. Whereas before the law the mean number of injured persons per month was 104.6 on average, after the law the figure rose to 154.3 (Table 1). After October 2004, the number of newly registered light motorcycles increased dramatically (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Observed number of people injured on the road before and after law allowing experienced car drivers to drive light motorcycles, versus number expected had the law not been passed, by type of vehicle, Barcelona, Spain, 1 January 2002 to 30 April 2008.

| Period | Motorcycle |

Moped |

Car |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (EC 51–125 cc) |

Heavy (EC > 125 cc) |

(EC ≤ 50 cc) |

|||||||||

| No. | Monthly mean | No. | Monthly mean | No. | Monthly mean | No. | Monthly mean | ||||

| Pre-law | |||||||||||

| Jan.–Sep. 2002 | 956 | 106.2 | 870 | 99.7 | 1 937 | 215.2 | 3 404 | 378.2 | |||

| Oct. 2002–Sep. 2003 | 1 312 | 109.3 | 1 114 | 92.8 | 2 700 | 225.0 | 4 466 | 372.2 | |||

| Oct. 2003–Sep. 2004 | 1 183 | 98.6 | 1 146 | 95.5 | 2 413 | 201.1 | 3 933 | 327.8 | |||

| Total | 3 451 | 104.6 | 3 130 | 94.7 | 7 050 | 213.6 | 11 803 | 357.7 | |||

| Post-law | |||||||||||

| Oct. 2004–Sep. 2005 | 1 482 | 123.5 | 1 352 | 112.7 | 2 267 | 188.9 | 3 805 | 317.1 | |||

| Oct. 2005–Sep. 2006 | 1 731 | 144.3 | 1 488 | 124.0 | 2 023 | 168.6 | 3 421 | 285.1 | |||

| Oct. 2006–Sep. 2007 | 2 119 | 176.6 | 1 487 | 123.9 | 2 006 | 167 | 3 130 | 260.8 | |||

| Oct. 2006–Apr. 2008 | 1 301 | 185.9 | 902 | 128.9 | 1 221 | 174.4 | 1 592 | 227.4 | |||

| Total | 6 633 | 154.3 | 5 259 | 121.6 | 7 517 | 174.8 | 11 948 | 277.9 | |||

| Expected no. (95% CI) | 4 534 | NA | 4 038 | NA | 8 217 | NA | 11 267 | NA | |||

| (3 849–5 218) | (3 881–5 115) | (7 246–9 188) | (10 028–12 507) | ||||||||

| No. observed minus no. expected (95% CI) | 2 099 | NA | 691 | NA | –700 | NA | 681 | NA | |||

| (1 418–2 784) | (34–1 348) | (–1 261–271) | (–559–1 920) | ||||||||

CI, confidence interval; EC, engine capacity; NA, not applicable.

Fig. 1.

Number of newly-registered light motorcycles (EC 50–125 cubic centimetres) before and after law allowing experienced car drivers to drive light motorcycles, Barcelona, Spain, 1 January 2002 to 30 September 2007

CI, confidence interval; EC, engine capacity.

Injuries involving heavy motorcycles also increased over the period (monthly mean: 94.7 before the law, and 121.6 after the law). At the same time, the number of newly registered heavy motorcycles showed a steady increase for the entire period, with no change after October 2004. Conversely, the number of moped and car riders who suffered injuries decreased over time during the same periods (monthly mean: 213.6–174.8 for mopeds, 357.7–277.9 for cars) (Table 1).

After controlling for trend and seasonality by fitting Poisson regression models, the risk of being injured as a motorcyclist on a light or heavy motorcycle was significantly higher in the post-law period (RR: 1.46; 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.34–1.60 for light motorcycles; RR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.02–1.29 for heavy motorcycles) (Table 2). For light motorcycles, the RR increased progressively every year after the law was passed, whereas for heavy motorcycles, the RR remained relatively stable over the post-law period (Table 2). After the law, the number of people injured per month increased significantly by 1.6% for light motorcycles and non-significantly by 0.5% for heavy motorcycles (Table 3). CIs for the trend in the entire post-law period and for the third year after the law was passed did not overlap. The RR for motorcycles with engines of unknown cubic capacity was 1.34 (95% CI: 1.15–1.57).

Table 2. Relative risk of being injured on the road, and attributable fraction, since the passing of law allowing experienced car drivers to drive light motorcycles, by type of vehicle, Barcelona, Spain, 1 January 2002 to 30 April 2008.

| Period | Motorcycle |

Moped |

Car |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (EC 51–125 cc) |

Heavy (EC > 125 cc) |

(EC ≤ 50 cc) |

|||||||||||||

| RRa (95% CI) | AF % | No. | RRa (95% CI) | AF % | No. | RRa (95% CI) | AF % | No. | RRa (95% CI) | AF % | No. | ||||

| Entire post-law period | 1.46 (1.34–1.60) | 32 | 2 091 | 1.15 (1.02–1.29) | 13 | 682 | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) | –9 | –654 | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 6 | 676 | |||

| 1 year after law | 1.18 (1.07–1.29) | 15 | 226 | 1.19 (1.09–1.42) | 16 | 216 | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | –4 | –94 | 1.03 (0.93–1.14) | 3 | 111 | |||

| 2 years after law | 1.38 (1.26–1.50) | 28 | 477 | 1.31 (1.20–1.42) | 24 | 352 | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | –11 | –225 | 1.01 (0.88–1.15) | 1 | 34 | |||

| 3 years after law | 1.68 (1.55–1.83) | 40 | 858 | 1.31 (1.20–1.42) | 24 | 352 | 0.93 (0.78–1.12) | –8 | –151 | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | –1 | –32 | |||

| 3 years and 7 months after law | 1.77 (1.59–1.96) | 44 | 566 | 1.37 (1.23–1.52) | 27 | 244 | 1.02 (0.81–1.28) | 2 | 24 | 0.92 (0.74–1.15) | –9 | –138 | |||

AF, attributable fraction; CI, confidence interval; EC, engine capacity; RR, relative risk. a In time-series analysis with Poisson regression models.

Table 3. Trend change in risk of injury from month to month before and after law allowing experienced car drivers to drive light motorcycles, by type of vehicle, Barcelona, Spain, 1 January 2002 to 30 April 2008.

| Period | Motorcycle |

Moped |

Car |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (EC 51–125 cc) |

Heavy (EC > 125 cc) |

(EC ≤ 50 cc) |

||||||||||||||||

| %a | P-value | %a | P-value | %a | P-value | %a | P-value | |||||||||||

| Trend | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-law | –0.30 | 0.253 | –0.10 | 0.951 | –0.40 | < 0.05 | –0.70 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Post-law | 1.30 | < 0.001 | 0.40 | < 0.05 | –0.30 | 0.063 | –0.90 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Change from pre- to post-law period | 1.60 | < 0.001 | 0.50 | 0.177 | 0.10 | 0.595 | –0.20 | 0.446 | ||||||||||

EC, engine capacity. a In time-series analysis with Poisson regression models.

The risk of being injured as a moped or car rider was not statistically different between the pre- and post-law periods (RR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.83–1.01 for mopeds; RR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.97–1.16 for cars). In fact, the decreasing trend continued into the post-law period for both moped and car riders, and no significant change was noted with respect to the pre-law period (Table 2 and Table 3).

To take exposure into account, we adjusted for the number of vehicles registered by city residents. After adjustment, no significant difference was noted in the number of persons injured in any type of vehicle before and after the law was passed. The adjusted RR for light motorcycles was 1.03 (95% CI: 0.80–1.34) and for heavy motorcycles, 1.08 (95% CI: 0.98–1.12).

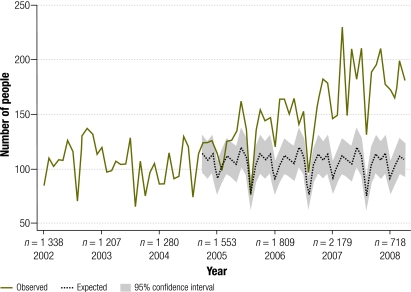

Fig. 2 shows the observed distribution of the number of people injured since 2002 as well as the expected distribution, with 95% CIs, if the motorcycle law had not been passed. For riders of light motorcycles, observed cases of injury were more numerous than expected cases, and the gap widened over time. The observed cases of injury among riders of heavy motorcycles were also more numerous than expected but stabilized during the fourth year. Over the 3-year period following the passing of the law, 2099 and 691 more riders were injured on light and heavy motorcycles, respectively, than before the law. An overlap was noted between observed and expected cases of injury among moped and car riders (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Observed and expected number of light motorcycle riders injured on the road, by month,a Barcelona, Spain, 1 January 2002 to 30 April 2008

a Time-series analysis with Poisson regression models, adjusted for trend and seasonality.

Table 4 shows the sex and age distribution of those injured, by vehicle and period (before or after the passing of the law) and includes the cases that were not entered in the models due to missing information on engine cubic capacity. These cases were similar in sex and age distribution to those injured on light motorcycles.

Table 4. Sex and age of injured motorcycle, moped and car riders before and after law allowing experienced car drivers to drive light motorcycles, Barcelona, Spain, 1 January 2002 to 30 April 2008.

| Motorcycle |

Moped |

Car |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (EC 51–125 cc) |

Heavy (EC > 125 cc) |

Unknown |

(EC ≤ 50 cc) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Prea (n = 3451) % | Postb (n = 6633) % | Prea (n = 3130) % | Postb (n = 5229) % | Prea (n = 4350) % | Postb (n = 6217) % | Prea (n = 7050) % | Postb (n = 7515) % | Pre (n = 11 803) % | Post (n = 11 948) % | |||||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 66.6 | 67.7 | 81.6 | 84.1 | 65.7 | 66.4 | 64.7 | 64.9 | 55.6 | 57.4 | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 29.1 | 32.3 | 13.9 | 15.9 | 30.0 | 33.6 | 31.4 | 35.1 | 39.9 | 42.5 | ||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 4.3 | 0 | 4.5 | 0 | 4.3 | 0 | 4.0 | 0 | 4.5 | 0.1 | ||||||||||||||

| Age, in years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–13 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 4.0 | ||||||||||||||

| 14–17 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 13.1 | 13.3 | 1.6 | 1.5 | ||||||||||||||

| 18–30 | 49.7 | 47.6 | 41.9 | 34.1 | 52.5 | 49.0 | 68.6 | 64.3 | 44.6 | 39.8 | ||||||||||||||

| 31–45 | 34.2 | 36.2 | 43.9 | 46.7 | 29.7 | 34.6 | 14.3 | 18.1 | 26.0 | 29.1 | ||||||||||||||

| 46–65 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 11.8 | 16.8 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 18.7 | 19.9 | ||||||||||||||

| > 65 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 4.4 | ||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||

EC, engine capacity. a Period before the law: 1 January 2002 to 30 September 2004. b Period after the law: 1 October 2004 to 30 April 2008.

Table 5 shows the characteristics of drivers involved in collisions in which injuries occurred. As expected, the proportion of riders of light motorcycles who had only a car driver’s licence increased dramatically during the post-law period. The age and sex of the injured on motorcycles with engines of unknown cubic capacity resembled those of injured riders of light motorcycles. However, around one-third had a moped licence, so perhaps they were riding mopeds instead of motorcycles.

Table 5. Timing of collisions and characteristics of motorcycle, moped and car drivers involved in collisions in which injuries occurred, before and after law allowing experienced car drivers to drive light motorcycles, Barcelona, Spain, 1 January 2002 to 30 April 2008.

| Motorcycle |

Moped |

Car |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (EC 51–125 cc) |

Heavy (EC > 125 cc) |

Unknown |

(EC ≤ 50 cc) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Prea (n = 3551) % | Postb (n = 6798) % | Prea (n = 3317) % | Postb (n = 5489) % | Prea (n = 4640) % | Postb (n = 6439) % | Prea (n = 6947) % | Postb (n = 7668) % | Prea (n = 35 482) % | Postb (n = 42 318) % | |||||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 69.8 | 71.3 | 87.0 | 88.9 | 69.0 | 69.6 | 69.7 | 70.6 | 69.2 | 71.6 | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 21.2 | 24.5 | 5.8 | 7.8 | 22.7 | 25.8 | 24.0 | 26.3 | 14.0 | 15.9 | ||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 9.1 | 4.2 | 7.2 | 3.3 | 8.3 | 4.6 | 6.4 | 3.1 | 16.8 | 12.5 | ||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–13 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| 14–17 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 0 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 0.1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| 18–30 | 47.0 | 45.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 48.9 | 45.8 | 66.1 | 61.5 | 31.9 | 28.8 | ||||||||||||||

| 31–45 | 34.3 | 35.7 | 37.6 | 30.9 | 30.3 | 34.2 | 15.8 | 19.4 | 28.4 | 30.5 | ||||||||||||||

| 46–65 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 45.3 | 47.2 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 21.8 | 23.2 | ||||||||||||||

| > 65 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 12.7 | 17.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 3.9 | ||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 0.1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Day of collision | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weekend | 19.5 | 18.5 | 19.5 | 18.3 | 20.8 | 20.6 | 23.6 | 23.7 | 30.0 | 27.4 | ||||||||||||||

| Time of day | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8–20 h | 73.3 | 76.0 | 75.5 | 76.0 | 75.6 | 73.9 | 70.5 | 70.5 | 67.9 | 70.2 | ||||||||||||||

| Type of driver’s licence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A (motorcycle) | 73.9 | 42.7 | 89.1 | 86.5 | 37.8 | 31.4 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| B (car) | 4.1 | 42.4 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 18.7 | 28.3 | 21.8 | 23.4 | 82.3 | 84.1 | ||||||||||||||

| L (moped) | 11.3 | 6.8 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 33.2 | 31.5 | 64.5 | 63.8 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Other | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 10.6 | 8.1 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 17.1 | 15.7 | ||||||||||||||

EC, engine capacity. a Period before the law: 1 January 2002 to 30 September 2004. b Period after the law: 1 October 2004 to 30 April 2008.

Discussion

The results of this study strongly suggest that the number of road traffic injuries increases as a result of greater exposure to motorcycles when no special licensing requirement for motorcycle drivers is in place. The observed increase parallels the number of newly registered light motorcycles, and the risk of injury on a light motorcycle did not increase after adjustment for the larger number of registered vehicles. However, other factors might also have been associated with the increased number of injuries, since the number of injured riders of heavy motorcycles increased somewhat for 2 years after the law was enacted and stabilized in the third year. The number of injured users of other vehicles, such as mopeds or cars, decreased over time, even after the law went into effect.

The study has several strengths. The first was the availability of comparable data on the number of people injured before and after the passing of the law. This made it possible to control for major confounding factors, such as regression to the mean, a change in general trend and deviation of traffic to other roadways (e.g. during some road safety interventions).13 The large number of circulating motorcycles per inhabitant gave more power to the statistical analysis, and the Poisson regression time series made it possible to work without denominators. A second strength was the use of comparison groups. Although the study was conducted in a single city, we believe it has external validity.

The results of the study confirm the hypothesis that allowing licenced car drivers to drive light motorcycles without first developing the proper skills and passing a special test increases the risk of collisions involving this type of vehicle. We also found a minor increase in the number of injuries among heavy motorcycle riders, perhaps as a result of other factors. First, the number of newly registered motorcycles of all types increased steadily before 2004 (the year the law was passed), and the trend continued unchanged in subsequent years. Second, other measures intended to reduce the use of cars in the city, such as charging high prices for parking and redesigning roadways to reduce traffic congestion, have been adopted since 2004. Over time, this could have contributed to the decreasing number of people injured in car collisions. In 2004 there were 7158 metered parking places on the street, while in 2007 there were 40 482, and from 2005 to 2007 the total number of hectares for pedestrians in the city increased by 12.8%. Population growth and a rise in housing costs drove people outside the city limits, even though they still studied or worked in the city. This may have led to increased use of private transportation, as expanded subway and local train networks take time to develop.

After the new law, the proportion of light motorcycle riders who were injured monthly rose to an average of 1.6% for more than 3 years, perhaps partially as a result of the factors explained earlier. In addition, some drivers of light motorcycles involved in crashes could have been former moped drivers, which could explain in part the decreased use of mopeds. According to Seguí-Gómez, in some cases prior educational programmes and fees appeared to act as a de facto “barrier” to obtaining a motorcycle operator’s licence14. Our data do not allow for an assessment of the extent to which the increased risk of injury is due to lack of appropriate driver training. In other studies driver inexperience with motorcycle riding has been shown to be a risk factor for motorcycle collisions.15,16 Research on licensing programmes for motorcyclists suggests that specific restrictions, such as being under adult supervision, driving only in daylight and enforcement of a zero blood-alcohol level tolerance limit, are factors associated with a reduced number of collisions.17

A direct association between motorcycle sales and mortality rates has been reported previously.18 Paulozzi reported that, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, between 1997 and 2003 mortality rates from crashes involving motorcycle riders in the United States increased from 21.0 to 38.4 per 100 million motorcycle miles travelled. At the same time, the annual domestic sale of new motorcycles increased from 247 000 in 1997 to 648 000 in 2003. Mortality rates were higher among drivers or passengers of newer motorcycles. The author suggests two possible explanations: increased exposure from more extensive use of motorcycles that are new, and inexperience with motorcycle riding.

Other studies have assessed the effect of policy legislation on collision rates, but nearly all have focussed on the use of alcohol,19 a bicycle helmet20 or a motorcycle helmet21 or, more recently, on the existence of a penalty point system.22 Only one study has assessed the association between state motorcycle licensing laws and motorcyclist mortality rates. An association has been reported between the existence of specific motorcycle driver licensing policies and lower mortality rates.9 Lower rates have been observed in states requiring any of the following before issuance of a motorcycle permit: a test of motorcycle driving skills (RR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.69–0.84); motorcycle driver training (RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.74–0.86), possession of a learner’s permit for a longer time (95–190 days, RR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.79–0.95; > 190 days, RR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.81–0.93); three or more restrictions for those on a learner’s permit, such as lower speed limits, a zero blood alcohol level or daytime driving only (RR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.73–0.84), and the use of a full helmet (RR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.71–0.81).

One limitation of our study is that good mobility denominators, such as the total kilometers travelled by motorcycles, were not available. As a proxy we used the number of newly registered motorcycles. However, the type of analysis we conducted could be performed without denominators because we adjusted for linear trend and seasonality. It was impossible to adjust for injury severity because no data were available until 2005. According to Barcelona’s emergency surveillance system, the number of injured motorcyclists who were seen at an emergency department increased by 59.6% from 2003 (4117) to 2006 (6571), and the number of motorcyclists hospitalized increased by 87.5% from 2003 (312) to 2006 (585).

Another limitation of the study is the possible misclassification of the type of motorcycle due to insufficient information. We reduced the risk of misclassification by using brand and model. On the other hand, the exclusion of 21.3% of motorcycles from the analysis may have changed the magnitude, but not the essence, of the results. When motorcyclists driving vehicles of unknown engine capacity were added to those driving light motorcycles, the risk was reduced but still significant (RR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.18–1.33). When drivers of heavy motorcycles were added as well, the risk increased again (RR: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.11–1.124).

In conclusion, a new law allowing car drivers to drive light motorcycles without previously passing a special licensing test is associated with an increased number of road injuries involving light motorcycles. Other factors, such as measures aimed at reducing the use of cars, may have also contributed to such an increase. Policy-makers and legislators should consider the implications of laws such as the one described in this paper, which generate important gains for industry by facilitating access to a dangerous vehicle at the cost of an increased risk of road traffic injuries among the population. ■

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sector de Prevenció, Mobilitat i Seguretat of the Ajuntament de Barcelona, especially Mercé Navarro, Guàrdia Urbana, Joan Mañosa and Manuel Haro, for providing data.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.World report on road traffic injury prevention Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Road Safety Observatory. Traffic safety basic facts 2007: main figures Brussels: European Commission: 2007. Available from: http://www.erso.eu/safetynet/fixed/WP1/2007/BFS2007_SN-KfV-1-3-Main%20figures.pdf [accessed on 25 February 2009].

- 3.European Road Safety Observatory. Traffic safety basic facts 2007: motorcycles and mopeds Brussels: European Commission: 2007. Available from: http://www.erso.eu/safetynet/fixed/WP1/2007/BFS2007_SN-SWOV-13-MotorcyclesMopeds.pdf [accessed on 25 February 2009].

- 4.European Road Safety Observatory. SafetyNet. Annual statistical report 2007: building the European Road Safety Observatory Brussles: European Commission; 2007. Available from: http://www.erso.eu/safetynet/fixed/WP1/2007/SN-1-3-ASR-2007.pdf) [accessed on 25 February 2009].

- 5.Anuario estadístico general 2005. Madrid: Dirección General de Tráfico, Ministerio de Interior; 2005. Available from: http://dgt.es/was6/portal/contenidos/documentos/seguridad_vial/estadistica/accidentes_30dias/anuario_estadistico/anuario_estadistico008.pdf [accessed on 25 February 2009].

- 6.Villalbí JR, Pérez C. Evaluación de políticas regulatorias: prevención de las lesiones por accidentes de tráfico. Gac Sanit. 2006;20(Suppl 1):79–87. doi: 10.1157/13086030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Las principales cifras de la seguridad vial, España 2006 Madrid: Dirección General de Tráfico, Ministerio de Interior; 2007.

- 8.Informe anual de siniestralidad año 2007, datos provisionales Madrid: Dirección General de Tráfico, Ministerio de Interior; 2007. Available from: http://www.dgt.es/was6/portal/contenidos/documentos/seguridad_vial/estadistica/accidentes_24horas/resumen_anual_siniestralidad/resumen_siniestralidad002.pdf [accessed on 25 February 2009].

- 9.McGwin G, Whatley J, Metzger J, Valent F, Barbone F, Rue LW., 3rd The effect of State motorcycle licensing laws on motorcycle driver mortality rates. J Trauma. 2004;56:415–9. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000044625.16783.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cens de vehicles de la ciutat de Barcelona,2007. Departament d’estadística. Ajuntament de Barcelona Available from: http://www.bcn.cat/estadistica/catala/dades/inf/veh/veh07/veh07.pdf [accessed on 25 February 2009].

- 11.Stolwijk AM, Straatman H, Zielhuis GA. Studying seasonality by using sine and cosine functions in regression analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:235–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.4.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miettinen OS. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol. 1974;99:325–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elvik R. The importance of confounding in observational before-and-after studies of road safety measures. Acc Ann Prev. 2002;34:631–5. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segui-Gomez M, Lopez-Valdes FJ. Recognizing the importance of injury in other policy forums: the case of motorcycle licensing policy in Spain. Inj Prev. 2007;13:429–30. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.017475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeder AI, Alsop JC, Langley JD, Wagenaar AC. An evaluation of the general effect of the New Zealand graduated driver licensing system on motorcycle traffic crash hospitalisations. Accid Anal Prev. 1999;31:651–61. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullin B, Jackson R, Langley J, Norton R. Increasing age and experience: are both protective against motorcycle injury? A case-control study. Inj Prev. 2000;6:32–5. doi: 10.1136/ip.6.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedlund J, Shults RA, Compton R. Graduated driver licensing and teenage driver research in 2006. J Safety Res. 2006;37:107–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2006.02.001. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulozzi LJ. The role of sales of new motorcycles in a recent increase in motorcycle mortality rates. J Safety Res. 2005;36:361–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMillan GP, Lapham S. Effectiveness of bans and laws in reducing traffic deaths: legalized Sunday packaged alcohol sales and alcohol-related traffic crashes and crash fatalities in New Mexico. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1944–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macpherson A, Spinks A. Bicycle helmet legislation for the uptake of helmet use and prevention of head injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005401. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005401.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coben JH, Steiner CA, Miller TR. Characteristics of motorcycle-related hospitalizations: comparing states with different laws. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39:190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farchi S, Chini F, Rossi PG, Camilloni L, Borgia P, Guasticchi G. Evaluation of the health effects of the new driving penalty point system in the Lazio Region, Italy, 2001–4. Inj Prev. 2007;13:60–4. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.012260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]