Abstract

Problem

Comprehensive service delivery models for providing post-rape care are largely from resource-rich countries and do not translate easily to resource-limited settings such as Kenya, despite an identified need and high rates of sexual violence and HIV.

Approach

Starting in 2002, we undertook to work through existing governmental structures to establish and sustain health sector services for survivors of sexual violence.

Local setting

In 2003 there was a lack of policy, coordination and service delivery mechanisms for post-rape care services in Kenya. Post-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection was not offered.

Relevant changes

A standard of care and a simple post-rape care systems algorithm were designed. A counselling protocol was developed. Targeted training that was knowledge-, skills- and values-based was provided to clinicians, laboratory personnel and trauma counsellors. The standard of care included clinical evaluation and documentation, clinical management, counselling and referral mechanisms. Between early 2004 and the end of 2007, a total of 784 survivors were seen in the three centres at an average cost of US$ 27, with numbers increasing each year. Almost half (43%) of these were children less than 15 years of age.

Lessons learned

This paper describes how multisectoral teams at district level in Kenya agreed that they would provide post-exposure prophylaxis, physical examination, sexually transmitted infection and pregnancy prevention services. These services were provided at casualty departments as well as through voluntary HIV counselling and testing sites. The paper outlines which considerations they took into account, who accessed the services and how the lessons learned were translated into national policy and the scale-up of post-rape care services through the key involvement of the Division of Reproductive Health.

Résumé

Problématique

La plupart des modèles pour la prestation d’une gamme complète de soins de santé après un viol ont été développés pour des pays riches et ne se transposent pas facilement aux pays à ressources limitées comme le Kenya, malgré les besoins identifiés et les taux élevés de violence sexuelle et d’incidence du VIH dans ce pays.

Démarche

Depuis 2002, nous avons entrepris, par le biais des structures publiques existantes, d’établir et de maintenir des services sectoriels de santé pour les personnes ayant survécu à des violences sexuelles.

Contexte local

En 2003, on relevait un manque de politiques, de coordination et de mécanismes de prestation de soins pour prendre en charge les victimes de viol au Kenya. La prophylaxie post-exposition au VIH n’était pas proposée.

Modifications pertinentes

Une norme de soins et un algorithme simple pour représenter les dispositifs de soins après un viol ont été conçus. Un protocole de conseil a également été mis au point. Une formation ciblée reposant sur l’acquisition de connaissances, de compétences et de valeurs a été fournie aux cliniciens, au personnel de laboratoire et aux conseillers en gestion des traumatismes. La norme de soins couvrait l’évaluation clinique et les mécanismes de documentation, de prise en charge clinique, de conseil et d’orientation vers un spécialiste. Entre début 2004 et fin 2007, 784 survivants de violences sexuelles au total ont été soignés dans les trois centres, pour un coût moyen de US $ 27, ce nombre augmentant chaque année. Près de la moitié d’entre eux (43%) étaient des enfants de moins de 15 ans.

Enseignements tirés

Le présent article décrit comment les équipes multisectorielles de district au Kenya sont convenues de fournir une prophylaxie post-exposition, un examen physique et des services de prévention des infections sexuellement transmissibles et des grossesses. Ces présentations ont été délivrées dans les services d’urgence, ainsi que dans les centres de conseil et de dépistage volontaire du VIH. L’article indique les considérations prises en compte par ces équipes, les personnes ayant accès à ces services, la façon dont les enseignements tirés ont été transposés en politiques nationales et le développement à plus grande échelle des services de soins après un viol grâce à l’implication clé de la Division de la santé génésique.

Resumen

Problema

Los modelos de prestación de servicios integrados a las víctimas recientes de una violación proceden en su mayoría de países con abundantes recursos y no pueden exportarse fácilmente a otros entornos con recursos limitados, como por ejemplo Kenya, aunque se reconozca la necesidad de tales servicios y pese a registrarse unas altas tasas de violencia sexual e infección por VIH.

Enfoque

En 2002 empezamos a trabajar a través de las estructuras públicas existentes a fin de establecer y mantener servicios de salud para las personas que habían sobrevivido a episodios de violencia sexual.

Contexto local

En 2003 se carecía de políticas y de mecanismos de coordinación y dispensación de servicios para atender a las víctimas de violación en Kenya. Por ejemplo, no se ofrecía profilaxis postexposición contra la infección por VIH.

Cambios destacables

Se diseñaron unas normas de atención y un algoritmo simple de atención posviolación, y se elaboró un protocolo de asesoramiento. Se impartió formación focalizada -basada en conocimientos, aptitudes y valores- a médicos, personal de laboratorio y consejeros para víctimas de traumas psicológicos. Las normas asistenciales comprendían la evaluación y documentación de los casos, el tratamiento médico, el apoyo psicológico y mecanismos de derivación. Entre comienzos de 2004 y el final de 2007 se atendió a 784 supervivientes en los tres centros, con un costo medio de US$ 27 y en número creciente cada año. Casi la mitad (43%) eran menores de 15 años.

Enseñanzas extraídas

El artículo describe cómo una serie de equipos multisectoriales que actuaban a nivel de distrito se pusieron de acuerdo en Kenya para ofrecer servicios de profilaxis postexposición, exploración física, atención contra las infecciones de transmisión sexual y prevención del embarazo. Esa asistencia se proporcionó en servicios de urgencias, así como a través de centros de asesoramiento y pruebas voluntarias del VIH. Se explica en el texto el tipo de consideraciones que se tuvieron en cuenta, quiénes accedieron a los servicios, y de qué manera las lecciones extraídas se reflejaron en las políticas nacionales y la expansión de los servicios de atención a las víctimas de violación gracias a la decisiva implicación de División de Salud Reproductiva.

ملخص

المشكلة

تتوافر المعلومات عن نماذج إيتاء الخدمات الشاملة تلو الاغتصاب بشكل كبير من البلدان الغنية بالموارد ولا يمكن ترجمتها بسهولة إلى المواقع المحدودة الموارد مثل كينيا، وذلك رغم تبيُّن الحاجة إلى ذلك والمعدلات المرتفعة للعنف الجنسي وللإيدز.

الأسلوب

بدأ الباحثون بالعمل منذ عام 2002 من خلال الهياكل الحكومية الموجودة لإنشاء وضمان استمرار خدمات القطاع الصحي لضحايا العنف الجنسي.

الموقع المحلي

في عام 2003 لم تكن هناك سياسات أو تنسيق أو آليات إيتاء الخدمات للرعاية تلو الاغتصاب في كينيا. ولم تكن الوقاية التالية للتعرُّض للعدوى بفيروس الإيدز تقدم آنذاك.

التغيرات ذات الصلة

تم تصميم معيارٍ للرعاية وخوارزميات للنُظم البسيطة تلو الاغتصاب، كما تم إعداد بروتوكول إرشادي، وتم تقديم التدريب الموجَّه الـمُرتكز على المعارف والمهارات والقيم للأطباء السريريـين (الإكلينيكيـين) وللعاملين في المختبرات والمشاورين حول الرضوح. وقد تضمن معيار الرعاية تقيـيماً سريرياً (إكلينيكياً)، وتوثيقاً، وإدارة سريرية وإرشاد وآليات للإحالة. وفي الفترة بين مطلع 2004 ونهاية عام 2007، تمت معالجة 784 من ضحايا العنف الجنسي في المراكز الثلاثة بتكلفة مقدراها الوسطي 27 دولاراً أمريكياً، ويزداد هذا العدد كل عام؛ وكان ما يقرب من نصف هؤلاء (43%) من الأطفال الذين تقل أعمارهم عن 15 عاماً.

الدروس المستفادة

تصف هذه الورقة فرقاً متعددة القطاعات في مستوى المقاطعات في كينيا اتفقوا على أنهم سيقدمون الوقاية التالية للتعرُّض والفحص البدني والخدمات الخاصة بالعدوى المنقولة جنسياً وباتقاء الحمل. وقد قدمت هذه الخدمات في أقسام الحوادث والإصابات ومن خلال تقديم المشورة والاختبار الطوعيين حول فيروس الإيدز. وتصف هذه الورقة الاعتبارات التي أخذت بالحسبان، ومن تتاح له هذه الخدمات، وكيف ترجمت الدروس المستفادة إلى سياسات وطنية إلى جانب النهوض بخدمات الرعاية تلو الاغتصاب من خلال الإسهام الهام لإدارة لإدارة الصحة الإنجابية.

Introduction

Sexual violence is increasingly documented in Kenya but only limited post-rape care services exist.1,2 Survivors of sexual violence experience complex needs3 and many countries have developed one-stop facilities that enable survivors to access medical, legal and social support services.4–6 These do not translate easily to the resource-poor Kenyan setting.7 This paper summarizes the context of the Kenyan health system, presents findings from a situation analysis on post-rape care conducted in 2002 and outlines the lessons learned from the subsequent implementation of services in three district hospitals in Kenya between 2003 and 2007.

Kenyan context

The Kenyan government health system operates an integrated (sometimes termed “horizontal”) approach to primary care.8 The over-arching responsibility for policy and capacity development in the delivery of post-rape care services lies centrally with the government’s Division of Reproductive Health. It functions through provincial and district systems, where the District Health Management Teams are the primary unit of planning and managing post-rape care in health facilties.9 Alongside this, programmes for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV testing are supervised and managed nationally (a “vertical” approach). If survivors of sexual violence are to access the range of basic services they require, existing links between vertical and horizontal programmes involved in post-rape care require strengthening (Table 1).10,11 Links with the judiciary in Kenya are weaker still, compounding difficulties faced by the health sector in the collection, analysis and delivery of evidence to the justice system.

Table 1. Location and service delivery module for post-rape care services in Kenya.

| Service required | Department responsible | Service delivery location in district hospitals | Predominant service delivery mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injuries management | – | Casualty | Horizontal | |||

| Legal documentation | – | Examining medical officer | Horizontal | |||

| Laboratory services (specimen analysis) | National Reference Laboratories | Local laboratory | Horizontal | |||

| HIV testing | National Laboratories/NASCOP | Local laboratory | Vertical | |||

| Emergency contraception | Division of Reproductive Health | Maternal and Child Health/Family Planning | Horizontal | |||

| Counselling services (related to HIV) | National AIDS and STI Control Programme | Voluntary counselling and testing sites | Vertical | |||

| Counselling services | Mental Health Services | Diagnostic counselling sites | Horizontal | |||

| HIV PEP | National AIDS and STI Control Programme | HIV care clinics | Vertical | |||

| STI prophylaxis | National AIDS and STI Control Programme/ Division of Reproductive Health | STI clinics | Vertical/horizontala | |||

| Data and records management | Ministry of Health Monitoring and Evaluation Unit | District Health Records Information Office | Integrated health management information system |

NASCOP, National AIDS/STI Control Programme; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection. a Since 2006 STI treatment has been conducted through a horizontal approach.

A situation analysis in 2003 revealed limited post-rape services, lack of policy and tensions between HIV and reproductive health staff at service delivery points.12 Facilities lacked protocols and confidential spaces for treatment. Beyond a requirement that examinations be undertaken by a doctor, there were no reporting requirements and an absence of monitoring and evaluation of services. Furthermore, survivors were required to pay for drugs and services in public institutions. Where HIV-test counselling existed, it was delivered in the context of voluntary counselling and testing (VCT). Formal counselling for sexual trauma, where it existed, did not give consideration to HIV testing.

System development process

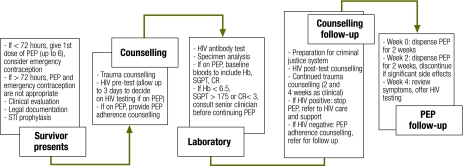

A standard of care was developed in selected districts. In collaboration with a Kenyan nongovernmental organization (Liverpool VCT, Care & Treatment ) services were established in government health facilities in three disparate districts in 2003 (Thika, Malindi and Rachuonyo) with the aim of informing national policy directly with experiences from the field. Consultation workshops were hosted with the District Health Management Teams to develop consensus and create ownership. Each team assigned the coordination of post-rape care services to an individual member, who then liaised with the local police to ensure immediate referral of survivors to health facilities. The services were advertised through existing public health systems and wider staff training. A standard of care was agreed for the selected districts and protocols for physical examination, legal documentation and clinical management were drawn from this. A simple algorithm and clearly defined client flow pathway summarized in a job aide, improved triage and facilitated access to the range of service delivery points (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Post-rape care services algorithm developed for health facilities in Kenya

CR, creatinine; Hb, haemoglobin; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; SGPT, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

The first port of call for survivors was the casualty (emergency) department, open 24 hours a day, where physical examination was conducted by a doctor, records kept and further referrals made. Emergency contraception, empirical STI treatment and starter packs of a two-drug HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) regimen13 were kept in casualty as part of essential drugs and offered routinely to survivors on presentation. To facilitate the collection of evidence, a locally assembled “post-rape” kit was supplied by the district’s sterilizing and surgical department. It included gloves, swabs and plastic bags, glass slides for preparing specimen mounts, sanitary pads and a speculum. Police signed for any specimens they removed from casualty thus initiating a chain of custody of evidence. Data was captured by registers on the history of the alleged assault, therapies provided and specimens collected. After referral from casualty, post-rape counselling services were provided in the VCT sites; laboratory staff documented the results of HIV and other testing; and HIV care clinic staff prescribed and documented on-going PEP.

Two separate peer-reviewed training programmes were piloted in the districts and are available for use in other settings.13 A core element of both was the exploration of attitudes around gender, abuse and sexuality. A 3-day training course aimed at all types of frontline clinicians involved in post-rape care included skills for clinical evaluation, risk assessment13 and legal documentation. The other longer course targeted practicing HIV counsellors from the facilities and focused on skills and observed practice for trauma counselling, HIV testing after rape, PEP adherence and legal information.

Initial challenges

All three districts experienced significant challenges in implementing the new services, many of which related to the lack of coordination between vertical and horizontal systems. For example, Thika and Rachuonyo district hospitals were unable to prescribe empirical STI treatment from existing stocks until new systems for reporting were developed that did not directly link drug supply to screening results. The majority of clinicians felt that they were not ready to deliver evidence in court and were reluctant note-takers. Poor referral mechanisms from the smaller health facilities to the three district hospitals and within the hospitals themselves were associated with losses to follow up, out-of-pocket costs to survivors and poor coordination of services.

Counsellors also experienced uncertainly around shared confidentiality: the rights of the survivor in relation to those of the counsellor to disclose results for medical reasons or when the survivor was a sexually active minor. Currently, the lack of a cadre of counsellors in the Kenyan government system has hampered post-rape care. Many health-care workers end up doing HIV testing and also trauma counselling in addition to their normal duties. This translates into provider stress, high attrition rates and inconsistent service delivery that challenge the investment in capacity building described in this paper.

Uptake and client satisfaction

By the end of 2007 a total of 784 survivors of sexual violence had been seen in the three sites, with 43% of them young people (predominantly girls) aged less than 15. Of these 84% arrived in time to be eligible for PEP. There was one known seroconversion of a previously HIV-negative girl, who had reported repeated abuse by an uncle. Client exit interviews conducted with survivors or their guardians in 2005 indicate a high level of satisfaction with the services. No information on prosecution and conviction rates of perpetrators is available but anecdotally these are very low.

Using lessons to inform policy

In mid 2004, the Kenyan Division of Reproductive Health disseminated the findings of the situation analysis12 and the interventions and challenges described above, including the high numbers of paediatric presentations. The high paediatric uptake is likely to represent a reflection of the social constructs around rape in Kenya, which may cause the blame for sexual violence to be put on the adult survivors but sees children as victims.12 A committee was constituted and national guidelines for the medical management of rape and sexual violence14 approved and disseminated in 2005, with the Division of Reproductive Health recommending user-fees be waived. A universal data form, agreed and approved by the Ministry of Health, became the first clinical form acceptable for legal presentation of sexual violence in a Kenyan court. The training curricula were peer-reviewed and approved as the national manuals in 2006. Since 2006, indicators for post-rape care, including the number of health-care workers trained, the number of health facilities offering services, percentage of police officers trained and the percentage of antiretroviral treatment sites offering post-rape care, have been incorporated in national planning. This has ensured annual reporting and appropriate assignment of resources for purchase of emergency contraception and PEP. By June 2007, there were 13 health facilities providing post-rape care services in Kenya including the national referral and teaching hospital. Between them they had delivered services to over 2000 adults and children with 96% of those eligible initiating PEP at presentation.

A formal costing of the services, undertaken between June 2005 and July 2006, revealed that laboratory tests (28%), antiretroviral drugs for PEP (25.7%), cost of staff (23%) and hepatitis B toxoid (6.9%) were the main expenditures. The cost of providing post-rape care services for females or males at the district hospital level were estimated at US$ 27 per patient, in line with other new services such as HIV counselling and testing.15

The potential to improve relationships between the health sector and justice systems has not been realized in Kenya. Specimen collection of sufficient standard to provide evidence in court was undermined by the lack of commercial specimen collection kits or availability of additional requirements such as tamper evidence seals, replacement clothing and specula suitable for children. In addition there was a lack of DNA profile testing. We were unable to determine how many of the survivors received legal support or the role played by the evidence that was collected. This remains a practical and policy gap in the provision of post-rape care.

Conclusion

Kenya has seen a rapid policy response to the documented need for post-rape care services among both adult and child survivors. Key lessons learned (Box 1) were: the importance of a participatory policy development process; the central role of political commitment in overcoming tensions between vertical and horizontal programmes; and the flexibility to develop creative solutions at local level where paediatric uptake is high. The processes described in this paper are replicable in other settings and we look forward to further sharing our experience in this neglected area. ■

Box 1. Summary of lessons learned.

The importance of a participatory policy development process

The central role of political commitment in overcoming tensions between vertical and horizontal programmes

Flexibility to develop creative solutions at local level where paediatric uptake is high

Acknowledgements

We thank all the health-care providers that participated in this intervention.

Footnotes

Funding: Liverpool VCT, Care & Treatment, Kenya, through core funding support from Trocaire and DfID, funded all aspects of the study. The researchers were independent from funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mensch BS, Hewett P, Erulkar A. The reporting of sensitive behaviour among adolescents: a methodological experiment in Kenya. Demography. 2003;40:247–68. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speight CG, Klufio A, Kilonzo SN, Mbugua C, Kuria E, Bunn JE, et al. Piloting post-exposure prophylaxis in Kenya raises specific concerns for the management of childhood rape. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidelines for medico-legal care of victims of sexual violence Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerr E, Cottee C, Chowdhury R, Jawad R, Welch J. The Haven: a pilot referral centre in London for cases of serious sexual assault. BJOG. 2003;110:267–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JC, Martin LJ, Denny L. Rape and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: addressing the dual epidemics in South Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11:101–12. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(03)02285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg AP, Duffy SJ. Medical care for the sexual assault victim. Med Health R I. 2003;86:390–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Moreno C. Dilemmas and opportunities for an appropriate health-service response to violence against women. Lancet. 2002;359:1509–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DL, Bryant JH. Building the infrastructure for primary health care: an overview of vertical and integrated approaches. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26:909–17. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90411-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyaya CO, Rifkin SB. Health sector reforms in Kenya: an examination of district level planning. Health Policy. 2003;64:113–27. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts C, Mayhew S. Reproductive health services and intimate partner violence: shaping a pragmatic response in sub-Saharan Africa. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:207–13. doi: 10.1363/3020704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira-Cruz V, Kurowski C, Mills A. Delivery of priority health services: Searching for synergies within the vertical versus horizontal debate. J Int Dev. 2003;15:67–86. doi: 10.1002/jid.966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilonzo N, Taegtmeyer M, Molyneux S, Kibaru J, Kamonji V, Theobald S. Engendering health sector responses to sexual violence and HIV in Kenya: Results of a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2008;20:188–90. doi: 10.1080/09540120701473849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia MT, Figueiredo RM, Moretti ML, Resende MR, Bedoni AJ, Papaiordanou PM. Postexposure prophylaxis after sexual assaults: a prospective cohort study. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:214–9. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000149785.48574.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health/Division of Reproductive Health. National guidelines on the medical management of rape/sexual violence Nairobi: Tonaz Agencies; 2004. Available from: http://www.drh.go.ke/html/guidelines_Gender.asp [accessed on 20 February 2009].

- 15.Forsythe S, Arthur G, Ngatia G, Mutemi R, Gilks C. Assessing the cost of voluntary counselling and testing in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17:187–95. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]