Abstract

In 2003, the Mexican Congress approved a reform establishing the Sistema de Protección Social en Salud [System of Social Protection in Health], whereby public funding for health is being increased by one percent of the 2003 gross domestic product over seven years to guarantee universal health insurance. Poor families that had been excluded from traditional social security can now enrol in a new public insurance scheme known as Seguro Popular [People’s Insurance], which assures legislated access to a comprehensive set of health-care entitlements. This paper describes the financial innovations behind the expansion of health-care coverage in Mexico to everyone and their effects. Evidence shows improvements in mobilization of additional public resources; availability of health infrastructure and drugs; service utilization; effective coverage; and financial protection. Future challenges are discussed, among them the need for additional public funding to extend access to costly interventions for non-communicable diseases not yet covered by the new insurance scheme, and to improve the technical quality of care and the responsiveness of the health system. Eventually, the progress achieved so far will have to be reflected in health outcomes, which will continue to be evaluated so that Mexico can meet the ultimate criterion of reform success: better health through equity, quality and fair financing.

Résumé

En 2003, le Congrès mexicain a approuvé une réforme instaurant le Sistema de protección social en Salud (Système de protection sociale de la santé) et conduisant à une augmentation du financement public de la santé de 1% du produit intérieur brut de 2003 sur sept ans pour assurer la mise en place de la sécurité sociale universelle. Les familles pauvres jusque là exclues de la sécurité sociale traditionnelle peuvent maintenant bénéficier d’un nouveau schéma d’assurance publique, appelé Seguro Popular (Assurance du peuple), qui garantit un accès régi par la loi à un ensemble complet deprésentations de santé. L’article présente les innovations financières qui ont permis cet élargissement à tous les Mexicains de la couverture par les soins de santé, ainsi que leurs effets. Certains éléments attestent d’améliorations en matière de mobilisation de ressources publiques supplémentaires, de disponibilité des infrastructures de santé et des médicaments, d’utilisation des services, d’efficacité de la couverture et de protection financière. L’article évoque les défis à surmonter dans l’avenir, et notamment les besoins en fonds publics supplémentaires pour élargir l’accès à des interventions coûteuses contre des maladies non transmissibles pas encore couvertes par le nouveau schéma d’assurance et pour améliorer la qualité technique des soins et la capacité de réponse du système de santé. Enfin, les progrès réalisés jusqu’à présent devront se refléter dans les résultats sanitaires, qui continueront d’être évalués de manière à ce que le Mexique puisse remplir l’ultime critère de succès de la réforme : une meilleure santé grâce à l’équité, à la qualité et à la justice dans l’affectation des fonds.

Resumen

En 2003, el Congreso de México aprobó una reforma por la que se creó el Sistema de Protección Social en Salud, en virtud del cual se aumenta la financiación pública de la salud en un uno por ciento del producto interno bruto de 2003 a lo largo de siete años a fin de implantar el seguro médico universal. Las familias pobres hasta entonces excluidas de la seguridad social tradicional pueden ahora integrarse en un nuevo sistema de seguro público conocido como Seguro Popular, que garantiza por ley el acceso a un amplio conjunto de prestaciones de salud. En este artículo se describen las innovaciones financieras que han permitido expandir la cobertura sanitaria en México a toda la población, así como sus efectos. Los datos disponibles muestran mejoras en la movilización de recursos públicos adicionales; la disponibilidad de infraestructura sanitaria y medicamentos; el uso de los servicios; la eficacia de la cobertura, y la protección financiera. Se analizan algunos retos futuros, entre ellos la necesidad de financiación pública adicional para ampliar el acceso a intervenciones costosas para enfermedades no transmisibles aún no cubiertas por el nuevo sistema de seguro, así como para mejorar la calidad técnica de la atención y la capacidad de respuesta del sistema de salud. A la larga, los progresos conseguidos hasta ahora deberán reflejarse en los resultados sanitarios, que seguirán siendo evaluados para que México pueda cumplir el criterio último de éxito de la reforma, esto es, el logro de una mejor salud mediante una mayor equidad y calidad y una financiación justa.

ملخص

في عام 2003 صادق الكونغرس المكسيكي على إصلاحات في نظام الحماية الاجتماعية للصحة، ووفقاً لذلك سيزداد تمويل القطاع العام للصحة بمقدار 1% من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي على مدى 7 سنوات لتوفير الضمان الصحي الشامل. وقد أصبح بمقدور الأسر الفقيرة التي كانت مستبعدة من الضمان الاجتماعي التقليدي أن تستفيد من الخطة الجديدة للضمان الاجتماعي والمعروفة بالضمان الشعبي؛ وهو أمر يضمن الإتاحة المشروعة لمجموعة شاملة من الاستحقاقات في الرعاية الصحية. وتصف هذه الورقة مبادرات تمويلية تدعم التوسع في الرعاية الصحية في المكسيك لتشمل الجميع، وما يؤدي إليه ذلك من تأثيرات. وقد أظهرت البيِّنات جوانب التحسين في استجلاب موارد إضافية من القطاع العام، وتوفير البنية التحتية للصحة والأدوية، والانتفاع بالخدمات، والتغطية الفعَّالة، والحماية التمويلية. وقد نوقشت التحديات المستقبلية ومن بينها الحاجة إلى تمويل إضافي من القطاع العام لتوسيع الإتاحة للتدخلات العالية التكاليف للأمراض غير السارية التي لم تتم تغطيتها بعد بالخطة الجديدة للضمان، ولتحسين الجودة التقنية للرعاية، ومدى استجابة النظام الصحي. وفي النهاية، ينبغي أن ينعكس التقدُّم الـمُحْرَز حتى الآن على الحصائل الصحية، والتي سيتواصل تقييمها حتى تتمكن المكسيك في نهاية الأمر من تحقيق المعايير القصوى لنجاح الإصلاحات: الوصول إلى رعاية صحية أفضل من حيث الجودة والعدالة والتمويل.

Introduction

Institutional arrangements for sufficient, efficient, sustainable and fair financing are a major determinant of health system performance. Because of technical complexities, political sensitivities and ethical implications, the solution to the main financing challenges faced by health sectors has been elusive. It is therefore necessary to design and implement policies based on evidence about which arrangements work best, especially in developing countries. This paper seeks to contribute to this aim by describing a recent example of successful reform.

In 2003, a large majority of the Mexican Congress approved a reform to the Mexico’s Ley General de Salud [General Health Law] establishing the Sistema de Protección Social en Salud [System of Social Protection in Health], which is increasing public funding to guarantee universal health-care coverage. Poor families formerly excluded from traditional social security can now enrol in the Seguro Popular [People’s Insurance], a new public insurance scheme that assures legislated access to comprehensive health care.

In this paper we describe the financial innovations linked with the expansion of health-care coverage in Mexico. Since previous papers have described what led to the reform and how it was implemented,1–7 we focus on its initial effects on the mobilization of additional public resources, the availability of health infrastructure and basic inputs, service utilization, effective health-care coverage and financial protection. Obstacles and future challenges surrounding the reform are also discussed.

Background

In the mid-1990s, Mexico developed a system of national health accounts. This system showed, quite surprisingly, that more than half of the total national health expenditure was out-of-pocket because approximately half of the country’s population lacked health insurance.8 By applying methods from The world health report 2000 to a series of national income and expenditure surveys, researchers were able to show that these high levels of out-of-pocket spending were exposing Mexican households to catastrophic financial events. In 2000, an estimated 3 to 4 million Mexican families incurred catastrophic or impoverishing health expenditures.9 As a result, Mexico did very poorly on the international comparative analysis of fair financing, even though it performed relatively well in other areas of health system performance designated by WHO for The world health report 2000.10

Mexico’s poor results led policy-makers from the Ministry of Health (MoH) to focus on health system financing and triggered national and sub-national analyses that showed a concentration of impoverishing health expenditures in poor and uninsured households.11 Careful analyses also identified the existence of five financial imbalances, documented later in this paper, that kept the health system from mobilizing the additional resources needed to face the epidemiological transition, with its increase in non-communicable diseases and injuries requiring costly management.12,13

The above evidence boosted the advocacy required to promote a major legislative reform establishing the Sistema de Protección Social en Salud, whereby public funding is being increased by 1% of the 2003 gross domestic product (GDP) over seven years to provide universal health insurance. Over a phase-in period of seven years, this will provide access to formal social insurance, to the 45 million Mexicans who had been excluded from it in the past. A large proportion of this population formerly received care at MoH care centres on a welfare basis and benefits varied enormously, from a relatively large package of services in the largest cities of the wealthy northern states to a basic set of preventive interventions for the poor in the rural south. The new Seguro Popular scheme guarantees access to a package of 255 health interventions targeting more than 90% of the causes leading to service demand in public outpatient units and general hospitals, and a package of 18 costly interventions. Most interventions are provided by the service networks of the state ministries of health, which have their own outpatient units and hospitals, and hire their own salaried health staff, including physicians and nurses. These same networks provide services to the uninsured population. However, for those affiliated with the Seguro Popular, services are free of charge at the time of delivery and include the drugs prescribed. By the end of 2007, 20 million people in Mexico were Seguro Popular beneficiaries.

Financial innovations

Central to the financial innovations linked to Mexico’s recent health reform is the separation of funding for personal or clinical health services and health-related public goods. Such separation is intended to protect public health interventions within a reform framework in which subsidies are granted in response to the demand for health care, to the potential neglect of public health services.

In the Sistema de Protección Social en Salud, funds are allocated into four components: (i) stewardship, information, research and development; (ii) community health services; (iii) non-catastrophic, personal health services; and (iv) high-cost personal health services. Stewardship functions, health research, the generation and dissemination of information, and human resource development are financed through the regular budget of the MoH, while the Fondo de Servicios de Salud para la Comunidad [Fund for Community Health Services] is used to finance public health services (health promotion, immunization and epidemiological surveillance and the control of diseases, including communicable ones such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria). The rationale behind such funding is the lack of spontaneous demand for public health services, known in economics as positive externalities.

In contrast, funding for personal services is based on an insurance logic, which deals with uncertainty. The Seguro Popular is the insurance instrument devised to finance these services under the reform. For financing purposes, personal health services derive from two sources: a package of essential interventions provided in outpatient settings and general hospitals and financed through a fund for personal health services, and a package of high-cost, specialized interventions financed through the Fondo de Protección contra Gastos Catastróficos [Fund for Protection against Catastrophic Expenditures, FPGC].

At present, 255 health interventions and their respective drugs are included in Mexico’s Catálogo Universal de Servicios Esenciales de Salud [Universal List of Essential Health Services], designed to cover practically all the interventions in demand in outpatient units and general hospitals of the MoH. Some may ask why a package was developed, rather than including all interventions sought in these health units. The reasons are three. First, the intervention package serves as a blueprint to estimate the resources required to strengthen health service provision through three master plans for long-term investments in infrastructure, medical equipment and health personnel. Second, the package is used as a quality assurance tool designed to ensure that all necessary services are offered in accordance with standardized protocols. Under the new Ley General de Salud, no facility providing services can participate in the insurance scheme unless it is accredited, and accreditation is given only if they have the required resources to provide the stipulated interventions. Finally, the package is used to empower people by making them aware of their entitlements. According to Brachet-Márquez, to make health care a social right, what is needed, above all, is a definition of the set of health interventions that all citizens, regardless of their occupation or socioeconomic status, should receive and can legally demand.14 The new Ley General de Salud clearly states that Seguro Popular beneficiaries will have access to all health interventions included in both packages and to the drugs required. In fact, upon becoming affiliated, families receive a Carta de Derechos y Obligaciones [Charter of Rights and Duties] that lists the health interventions to which they are entitled.

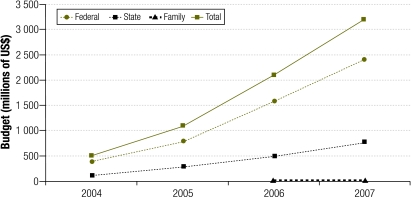

The FPGC, in turn, covers a package of services that are selected using cost, effectiveness and social acceptability criteria. To date, this fund finances 18 interventions, including neonatal intensive care and the management of paediatric cancers, cervical cancer, breast cancer and HIV/AIDS.15 The new Ley General de Salud stipulates that both packages must be progressively expanded and updated annually on the basis of changes in epidemiological profile, technological developments and resource availability. Fig. 1 describes the resources allocated to the Seguro Popular, including federal, state and family contributions.

Fig. 1.

Seguro Popular [People’s Insurance] budget by type of contribution, Mexico, 2004–2007

US$, United States dollars.

Adapted from reference 23.

The Seguro Popular will offer coverage to all Mexicans not protected by any other public insurance scheme: the self-employed, those who are out of the labour market and those in the informal sector of the economy. Since it is a public insurance scheme, differences in risk status are not considered for affiliation, so there is no danger that low-risk families will be exclusively selected (“cream skimming”). The vast aggregation of risks also eliminates the potential problem of adverse selection, which is common when risk pooling is not large enough.

Affiliation to the Seguro Popular is voluntary, yet the reform includes incentives for expanding coverage. States have an incentive to affiliate the entire population because their budget is based on an annual, per family fee. Further, families not affiliated by 2010 will still receive health care through public providers but will have to pay user fees at the point of service delivery. The voluntary nature of the affiliation process is an essential feature of the reform that helps democratize the budget by introducing an element of choice. It discourages adverse selection and provides incentives not only for universal coverage, but also for good quality and efficiency. Families will not re-affiliate unless a minimum level of quality and responsiveness is guaranteed, while wasteful care delivery would also limit the ability to provide all the benefits covered.

Seguro Popular funding follows a tripartite logic of financial responsibilities and rights, much like the funding for Mexico’s two major social security agencies: the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social [Mexican Institute for Social Security, IMSS] and the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado [Institute of Social Security for Government Employees, ISSSTE]. These agencies are financed through social contributions, based on the right of citizenship, obtained through (i) general taxes, (ii) the employer (with the government being the employer in the case of ISSSTE), and (iii) the employee (in the form of an amount tied to income).

The Seguro Popular has a similar financial structure. It is financed, first, through a social contribution from the federal government. Second, since there is no employer, financial co-responsibility is established between the federal and state governments to generate the so-called federal and state solidarity contributions. The third contribution comes from families and is tied to income, as in the case of social security institutions. Families in the two lowest tenths of the income distribution do not contribute. Annual family contributions range from 60 United States dollars (US$) for families in the lowest three-tenths of the income distribution to US$ 950 for families in the uppermost tenth.

Funding for the Seguro Popular is divided between federal and state governments. The FPGC equals 8% of the federal social contribution plus the federal and state solidarity contributions. Another fund, equivalent to 2% of the sum of the social quota and the federal and state contributions, is used to build health infrastructure in poor communities. A third reserve fund worth 1% of the total was designed to cover unexpected fluctuations in demand and temporarily overdue inter-state payments. These three funds are managed at the federal level to assure adequate risk pooling.

The remaining social contribution and the federal and state solidarity contributions are allocated to the states to fund the essential package of health services. State solidarity and family contributions are collected at the state level and remain there, and they are also used to fund the essential package.

Funding for the states is thus largely determined by the number of families affiliated with the Seguro Popular and is thus demand-driven. Formerly, federally-allocated state budgets for health were largely determined by inertia, the size of the health sector payroll and political negotiations.

Initial effects of the reform

The initial results of the reform are promising. Public resources for health have increased and are being distributed more fairly; the number of Seguro Popular beneficiaries has reached 20 million; availability of health personnel, facilities and drugs has increased; access and utilization of health-care services have expanded; and financial protection indicators have improved. Most of the data documenting this progress comes from the results of a comprehensive external evaluation that included a community trial module.16

Financial imbalances

Health expenditure in Mexico remains low when compared with the Latin American average (6.9% of the GDP) and in light of the demands generated by an epidemiological transition in which non-communicable diseases, which are more difficult and costly to treat than common infections and reproductive problems, are increasing in absolute and relative terms. Nonetheless, it has risen slowly but consistently over the last two decades. Expenditure for health increased from 4.8% of the GDP in 1990 to 5.6% in 2000 and to 6.5% in 2006.17,18 The increase generated in this last period was due mainly to the mobilization of additional public resources, mostly in connection with the reform.

The substantial increase in public funding is closing the gap between public and private financing of the national health system. Public health expenditure as a percentage of total health expenditure increased from 43.8% in 2002 to 46.4% in 2006.19 Given the anticipated increase in funding linked to the expansion of the Seguro Popular, public health expenditure is expected to continue to increase at a higher rate than private expenditure. Projections based on the annual growth in affiliation stipulated in the law and on recent trends in private expenditure suggest that public health financing will outgrow private financing and that by 2010 a much better balance between the two sources will have been attained.20

A much larger proportion of the additional public resources is currently being allocated to institutions caring for the population without access to social security (including Seguro Popular beneficiaries). The budget of the MoH increased 72.5% in real terms between 2000 and 2006, while the budget of the IMSS and ISSSTE grew 35% and 45%, respectively.19,21 This differential increase in the budgets of the major health and social security institutions is closing the gaps that existed in the allocation of public health financing for different segments of the population. The ratio of the per capita public expenditure for people covered by social security agencies to the per capita expenditure for the uninsured declined from 2.5 in 2000 to 2.0 in 2006 and will continue to fall with the legislated growth in the Seguro Popular.

Inequities in the distribution of public resources among states are also declining. Between 2000 and 2006, the difference in the per capita allocation of public resources between the state receiving the largest allocation and the state receiving the lowest decreased by five to four times.19 In the reform period, there was also less variation in the states’ contribution to health care financing, as shown by a drop in the variation coefficient from 1.14 to 1.11.19 Finally, public funding allocated to investment in health infrastructure has increased. In the MoH, the share of the budget allocated to such investment grew from 3.8% in 2000 to 9.1% in 2006.19

Insurance coverage

The mobilization of additional public resources for the Seguro Popular created the financial conditions required to expand health insurance coverage in Mexico. As a result, the population with social protection in health increased 20% between 2003 and 2007.

Because social security agencies lacked a nominal census, the size of the population with health insurance had to be estimated using several other sources, including population censuses and surveys. When this was done for the first time in 2004, the results showed that the number of beneficiaries of social security agencies (mainly the IMSS and ISSSTE, plus other smaller entities for the armed forces, oil workers and local government employees) amounted to 47.7 million, or 45.4% of the total population.22 IMSS and ISSSTE beneficiaries comprised 80% and 16.7% of this figure, respectively. During its first year of operation, the Seguro Popular had already enrolled 5.3 million people, for a total of 53 million insured individuals. If to this we add the 5 million people covered by private health insurance, many of whom were also social security beneficiaries, 45 million Mexicans still lacked health insurance in 2004.

These figures have improved. In 2006 the population with social security increased to 48.9 million and Seguro Popular beneficiaries reached 15.6 million, while the number of individuals covered by private health insurance rose to 5.3 million.18 As already mentioned, Seguro Popular beneficiaries had reached 20 million by the end of 2007, according to the most recent data from the MoH. Most of these families were previously uninsured: 96.9% belong to the two lowest tenths of the income distribution, 35.2% are rural families and close to 8.2% are families from indigenous communities.23 Interestingly, more than 23% are families headed by women. Thanks to the Seguro Popular, Mexico is on track to attain universal health insurance by 2010, as stipulated in the law that launched the current reform.

Health infrastructure and drug availability

As previously mentioned, one major objective of the reform was to increase investment in health infrastructure, which had decreased consistently over the two previous decades. The proportion of the MoH health budget devoted to investment increased from 3.8% in 2000 to 9.1% in 2006, and because of this, the MoH was able to construct 751 outpatient clinics and 104 hospitals, including high-specialty hospitals in the poorest states, between 2001 and 2006.24 In the public sector as a whole, 1054 outpatient clinics, 124 general hospitals and 10 high-specialty hospitals were built in the same period.

The availability of basic inputs in the public sector has also improved. During the reform period, regular external measurements of the availability of drugs in public institutions were carried out. In 2002, only 55% of the prescriptions issued in MoH outpatient clinics were fully filled. By 2006, this figure had increased to 79% in MoH outpatient clinics in general and to 89% in MoH outpatient clinics serving Seguro Popular beneficiaries.25 In some states, 97% of the prescriptions issued in outpatient clinics serving Seguro Popular beneficiaries were fully filled. In 2006, the percentage of prescriptions issued in social security institute outpatient clinics that were fully filled was consistently above 90, as opposed to less than 70 in 2002.

Health service utilization and effective coverage

Studies show that health service utilization patterns have also improved in Mexico after health sector reform. One study that looked at data from the 2005-2006 Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición [National Health and Nutrition Survey] showed that Seguro Popular beneficiares are more likely to use health services based on perceived need than uninsured individuals.6 This same study showed a link between affiliation and service utilization: all else being the same, a rise in affiliation to the Seguro Popular from 0% to 20% was associated with a rise in service utilization from 58% to 64%. An increase in service utilization was also noted based on MoH hospital discharge data.

According to a similar study based on data from the 2006 National Satisfaction and Responsiveness Survey implemented in 74 hospitals nationwide, Seguro Popular beneficiaries are more likely to seek hospital services for elective surgeries, diabetes and hypertension than the uninsured.26 The Seguro Popular has had an even greater effect on service utilization for the management of leukaemia in children, one of the catastrophic interventions covered by the FPGC. This effect was also found in the study mentioned in the previous paragraph.6

Actual service delivery can be measured more precisely through effective coverage, a metric that has been recently used in Mexico for key interventions.4,27 For 11 indicators (delivery of skilled birth attendance; antenatal care; bacille Calmette–Guérin, diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis and measles immunization; treatment of premature neonates, diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections; Papanicolaou screening for cervical cancer; management of hypertension and mammography) it was possible to compare measurements for 2000 and 2005–2006 using data from the National Health Survey and hospital discharge records. Results showed that national coverage has increased for most of the 11 interventions.4 Coverage for mammography, cervical cancer screening, skilled birth attendance, management of premature birth and treatment of hypertension showed important increases. Also, Seguro Popular beneficiaries were found to have significantly higher levels of coverage for mammography, cervical cancer screening and management of childhood acute respiratory infections and hypertension than the uninsured.6

Financial protection

Protecting the population against catastrophic health expenditures was one of the key goals of the reform process. Several studies show that this objective is being met. According to a study based on data from Encuestas de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares [National Household Income and Expenditure Surveys] that traced trends in catastrophic and impoverishing payments for health care from 1992 to 2005, all indicators of financial protection have improved since 2000.5

Another study based on data from the 2005-2006 Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición showed that the Seguro Popular has had a protective effect against catastrophic expenditures, both at the population level and in a subgroup of households that reported having used outpatient or inpatient services in the two weeks preceding the survey.6

Most importantly, a large community trial developed to evaluate, among other things, the effect of the Seguro Popular on financial protection showed similar results. This evaluation, developed by a group from Harvard University and Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health, showed that this insurance scheme provides protection against catastrophic and impoverishing health expenditures in communities where the Seguro Popular is being implemented.28 More specifically, the study showed an important decrease in catastrophic expenditure among households affiliated to this public insurance when two different thresholds for catastrophic expenditure were used (30% and 40% of disposable income). The same study suggested that the protective effect may be due to reduced hospitalization expenditure in these households. The study allows these changes to be reasonably attributed to the Seguro Popular, an encouraging finding in light of the short period (11 months) that transpired between baseline and follow-up measurements.

Conclusion

In Mexico, important strides have been made in increasing people’s access to comprehensive health care, thanks to a health reform that made health care a legal right, as prescribed by amendment to the Mexican Constitution in 1983. Through the new Seguro Popular, by 2010 high-quality health care will have been extended to everyone in Mexico. Thus, the democratization of health care – defined as the application of democratic norms and procedures to individuals deprived of the benefits and duties of citizenship, such as women, youngsters, ethnic minorities or workers of the informal sector of the economy29 – will have been attained.

This paper has provided evidence that the financial innovations linked to the Sistema de Protección Social en Salud are improving insurance coverage, the availability of health infrastructure and basic health inputs, health-service utilization, effective health-care coverage, and the levels of financial protection enjoyed by the Mexican population, especially among the poor. However, Mexico continues to face important challenges, mainly in connection with emerging diseases. Disease control efforts before the epidemiological transition yielded important improvements, but as immunization coverage increased and deaths from diarrhoea, acute respiratory infections and reproductive events dropped, non-communicable diseases began to take a proportionately larger toll. As a result, there is a critical need for additional public funding to extend access to costly interventions for non-communicable health conditions not yet covered by the FPGC, such as cardiovascular diseases, adult cancers and the complications of diabetes. The benefits offered by the Seguro Popular in public outpatient clinics and general hospitals are very similar to those provided by comparable services in social security agencies. However, there is still a need to extend the coverage of costly interventions, which is still higher at IMSS, ISSSTE and other social security agencies.

The quality of care is also expected to improve further, but not unless several areas are further strengthened: the technical quality of care; drug availability, especially in hospitals; prescription patterns; care availability during evenings and weekends in outpatient clinics and emergency services; and waiting times for outpatient emergency care and elective interventions.

Narrowing gaps in access to health services also remain a challenge, particularly in rural, dispersed and indigenous communities in Mexico’s southern states. A large proportion of the resources mobilized by the Seguro Popular must be directed towards these communities to strengthen health infrastructure and the availability of human resources and basic inputs. Another challenge facing the reformed system is how to achieve an adequate balance between additional investments in health promotion and disease prevention, on the one hand, and personal curative health services on the other. Finally, the Seguro Popular has also been criticized for further segmenting the health system. We would like to stress that this is a temporary situation. Given the financial restrictions the country faced in 2003, the national Congress decided to phase affiliation to the Seguro Popular over a seven-year period. However, by 2010 the health system will be, in fact, less fragmented; three public insurance schemes having a similar financial structure will provide services to the entire population.

The new Ley General de Salud also provides for the cross-utilization of services among beneficiaries of the different health agencies. In fact, the Seguro Popular is already buying services for its beneficiaries from the IMSS-Oportunidades programme and will probably do the same with IMSS and ISSSTE. In the near future, this should culminate in the financial integration of the system.

Eventually, the progress achieved so far in mobilizing additional resources, insurance coverage, service delivery and quality of care will be reflected in health outcomes. These will continue to be evaluated to ensure that Mexico meets the ultimate criterion of successful health reform: better health through equity, excellent quality and fair financing. ■

Footnotes

Competing interests: Two of the authors were directly involved in the design and implementation of the reform, which is the subject of this paper; one (Frenk) as Minister of Health of Mexico, and the other (Gómez-Dantés) as Director General for Performance Evaluation at the Ministry of Health. The third author (Knaul) also provided continuous external support to several of the reform initiatives.

References

- 1.Frenk J. Bridging the divide: global lessons from evidence-based health policy in Mexico. Lancet. 2006;368:954–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frenk J, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, Lezana MA, Knaul MF. Comprehensive reform to improve health system performance in Mexico. Lancet. 2006;368:1524–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.González-Pier E, Gutiérrez-Delgado C, Gretchens S, Barraza-Llorenz M, Porras-Condey R, Carvalho N, et al. Priority setting for health interventions in Mexico’s System for Social Protection in Health. Lancet. 2006;368:1608–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozano R, Soliz P, Gakidou E, Abbot-Klafter J, Feehan DM, Vidal C, et al. Benchmarking of performance of Mexican states with effective coverage. Lancet. 2006;368:1729–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knaul FM, Arreola-Ornelas H, Méndez-Carniado O, Bryson-Cahn C, Barofsky J, Maguire R, et al. Evidence is good for your health system: policy reform to remedy catastrophic and impoverishing health spending in Mexico. Lancet. 2006;368:1828–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gakidou E, Lozano R, González-Pier E, Abbott-Klafter J, Barofsky JT, Bryson-Cahn C, et al. Assessing the effect of the 2001-06 Mexican health reform: an interim report card. Lancet. 2006;368:1920–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sepúlveda J, Bustreo F, Tapia R, Rivera J, Lozano R, Oláiz G, et al. Improvement of child survival in Mexico: the diagonal approach. Lancet. 2006;368:2017–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frenk J, Lozano R, González-Block MA. Economía y salud: propuestas para el avance del sistema de salud en México Informe final. Mexico, DF: Fundación Mexicana para la Salud; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Programa Nacional de Salud 2001-2006. La democratización de la salud en México. Hacia un sistema universal de salud Mexico, DF: Secretaría de Salud; 2001.

- 10.The world health report 2000. Health systems: improving performance Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaul F, Arreola H, Méndez O. Protección financiera en salud: México 1992-2004. Salud Publica Mex. 2005;47:430–9. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342005000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frenk J, Knaul F, Gómez-Dantés O, González-Pier E, Hernández-Llamas H, Lezana MA, et al. Fair financing and universal protection: the structural reform of the Mexican health system Mexico, DF: Ministry of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knaul FM, Frenk J. Health insurance in Mexico: achieving universal coverage through structural reform. Health Aff. 2005;24:1467–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brachet-Márquez V. Ciudadanía para la salud: una propuesta. In: Uribe M, López-Cervantes, eds. Reflexiones acerca de la salud en México México, DF: Médica Sur, Editorial Panamericana; 2001. pp. 43-7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seguro Popular de Salud [Internet site]. Available from: www.seguro_popular.salud.gob.mx/contenidos/menu_beneficios/beneficios_inicio.html [accessed on 19 May 2009].

- 16.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de Protección Social en Salud: estrategia de evaluación Mexico, DF: Secretaría de Salud; 2006.

- 17.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD reviews of health systems: Mexico Paris: OECD; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Programa Nacional de Salud 2007–2012. Por un México sano: construyendo alianzas para una mejor salud Mexico, DF: Secretaría de Salud; 2007.

- 19.Vázquez VM, Merino MF, Lozano R. Cuentas en salud en México 2001-2005 Mexico, DF: Secretaría de Salud; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de Protección Social en Salud: evaluación financiera Mexico, DF: SS; 2006.

- 21.Gómez-Dantés O. 10 mitos sobre el Seguro Popular de Salud. Nexos 2008;362. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Salud: México, 2004 Mexico, DF: SS; 2005.

- 23.Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud. Informe de resultados, 2007 Mexico, DF: CNPSS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Presidencia de la República. Sexto informe de gobierno Mexico, DF: PR; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Evaluación del surtimiento de medicamentos a la población afiliada al Seguro Popular de Salud. In: Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de Protección Social en Salud: evaluación de procesos Mexico, DF: SS; 2006. pp. 59-78.

- 26.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Utilización de servicios y trato recibido por los afiliados al Seguro Popular de Salud. In: Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de Protección Social en Salud: evaluación de procesos Mexico, DF: Secretaría de Salud; 2006. pp. 39-57.

- 27.Mexico, Ministry of Health. Effective coverage of the health system in Mexico, 2000-2003. Mexico, DF: MOH; 2006.

- 28.Mexico, Secretaría de Salud. Evaluación de efectos. In: Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de Protección Social en Salud: evaluación de efectos Mexico, DF: Secretaría de Salud; 2007. pp. 21-68.

- 29.O’Donnell G, Schmitter P. Transiciones desde un gobierno autoritario Buenos Aires: Paidos; 1991. [Google Scholar]