Abstract

Objective

To estimate the impact of global strategies, such as pooled procurement arrangements, third-party price negotiation and differential pricing, on reducing the price of antiretrovirals (ARVs), which currently hinders universal access to HIV/AIDS treatment.

Methods

We estimated the impact of global strategies to reduce ARV prices using data on 7253 procurement transactions (July 2002–October 2007) from databases hosted by WHO and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Findings

For 19 of 24 ARV dosage forms, we detected no association between price and volume purchased. For the other five ARVs, high-volume purchases were 4–21% less expensive than medium- or low-volume purchases. Nine of 13 generic ARVs were priced 6–36% lower when purchased under the Clinton Foundation HIV/AIDS Initiative (CHAI). Fifteen of 18 branded ARVs were priced 23–498% higher for differentially priced purchases compared with non-CHAI generic purchases. However, two branded, differentially priced ARVs were priced 63% and 73% lower, respectively, than generic non-CHAI equivalents.

Conclusion

Large purchase volumes did not necessarily result in lower ARV prices. Although current plans for pooled procurement will further increase purchase volumes, savings are uncertain and should be balanced against programmatic costs. Third-party negotiation by CHAI resulted in lower generic ARV prices. Generics were less expensive than differentially priced branded ARVs, except where little generic competition exists. Alternative strategies for reducing ARV prices, such as streamlining financial management systems, improving demand forecasting and removing barriers to generics, should be explored.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer l’impact de stratégies mondiales, telles que l’organisation d’achats groupés, la négociation des prix avec l’aide d’un tiers et la tarification différentielle, en termes de baisse des prix des antirétroviraux (ARV), lesquels prix sont actuellement un obstacle à l’accès universel au traitement contre le VIH/sida.

Méthodes

Nous avons estimé l’impact des stratégies mondiales pour réduire les prix des ARV à partir des données de 7253 transactions d’achat (juillet 2002-octobre 2007), tirées de bases de données hébergées par l’OMS et le Fonds Mondial de lutte contre le sida, la tuberculose et le paludisme.

Résultats

Pour 19 des 24 formes posologiques d’antirétroviraux, nous n’avons mis en évidence aucune association entre le prix et le volume acheté. Pour les cinq autres formes posologiques, les achats de gros volumes étaient facturés 4 à 21 % moins chers que les achats de volumes faibles à moyens. Neuf des 13 ARV génériques ont été facturés 6 à 36 % de moins lorsqu’ils étaient acquis sous l’égide de l’Initiative contre le VIH/sida de la Fondation Clinton (CHAI). Quinze des 18 ARV de marque ont été facturés 23 à 498 % plus chers dans le cadre d’achats à prix différentiel que les génériques achetés sans la médiation de la CHAI. Néanmoins, deux ARV de marque, bénéficiant de la tarification différentielle, ont été facturés 63 et 73 % moins chers respectivement que des équivalents génériques acquis sans la médiation de la CHAI.

Conclusion

L’achat de gros volumes d’ARV ne s’accompagnait pas nécessairement d’une diminution du prix de ces médicaments. Même si les achats groupés actuellement prévus devraient accroître encore les volumes d’achat, les économies qui en découleront sont incertaines et doivent être mises en balance avec les coûts programmatiques. Les négociations avec la médiation de la tierce partie CHAI ont permis d’obtenir une baisse des prix pour les ARV génériques. Ces génériques étaient moins coûteux que les ARV de marque bénéficiant d’une facturation différentielle, sauf dans les cas où il existait peu de concurrence entre les génériques. Il convient d’explorer d’autres stratégies pour réduire les prix des ARV, telles que la rationalisation des systèmes de gestion financière, l’amélioration de la prévision de la demande et l’élimination des obstacles à l’utilisation des génériques.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estimar el impacto de estrategias mundiales como los arreglos de compras conjuntas, la negociación de precios a través de terceros y la fijación de precios diferenciales en lo relativo a reducir el precio de los antirretrovirales (ARV), factor que está obstaculizando el acceso universal al tratamiento de la infección por VIH/SIDA.

Métodos

Estimamos la repercusión de las estrategias mundiales tendentes a reducir el precio de los ARV a partir de los datos sobre 7253 operaciones de compra (julio de 2002 a octubre de 2007) extraídos de bases de datos de la OMS y del Fondo Mundial de Lucha contra el SIDA, la Tuberculosis y la Malaria.

Resultados

En 19 de las 24 formas farmacéuticas de ARV consideradas no detectamos ninguna relación entre el precio y la cantidad adquirida. Respecto a los otros cinco antirretrovirales, las compras de grandes cantidades fueron un 4%–21% más baratas que las compras de cantidades medias o bajas. Nueve de los 13 ARV genéricos se obtuvieron a precios entre un 6% y un 36% más bajos cuando se compraron a través de la Iniciativa VIH/SIDA de la Fundación Clinton (CHAI). Para quince de los 18 antirretrovirales de marca se fijó un precio un 23%–498% mayor en las compras con precios diferenciales que en las compras de genéricos no mediadas por la CHAI. Sin embargo, dos ARV de marca para los que se fijaron precios diferenciales se obtuvieron un 63% y un 73% más baratos que sus equivalentes genéricos no mediados por la CHAI.

Conclusión

La compra de grandes cantidades de ARV no siempre se tradujo en un abaratamiento de los mismos. Aunque los planes actuales de compras conjuntas harán que aumente el volumen de las adquisiciones, es dudoso que se consiga ahorrar dinero, y en todo caso esas economías deberían sopesarse considerando los costos programáticos. La negociación a través de terceros, por conducto de la CHAI, permitió abaratar los ARV genéricos. Los medicamentos genéricos fueron menos costosos que los ARV de marca sometidos a precios diferenciales, salvo cuando la competencia entre genéricos era escasa. Es preciso estudiar estrategias alternativas para reducir los precios de los ARV, como por ejemplo simplificar los sistemas de gestión financiera, mejorar las previsiones de la demanda y eliminar los obstáculos a la obtención de genéricos.

ملخص

الهدف

تقدير أثر الاستراتيجيات العالمية، مثل ترتيبات الشراء المجمَّع أو التفاوض على السعر مع طرف ثالث أو الأسعار التفاضلية، على خفض أسعار الأدوية المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية، التي تعيق إتاحة معالجة الإيدز في الوقت الحاضر على الصعيد العالمي.

الطريقة

قدر الباحثون أثر الاستراتيجيات العالمية لخفض أسعار الأدوية المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية باستخدام معطيات مستمدَّة من 7253 معاملة للشراء (بين تموز/يوليو 2002 وتشرين الأول/أكتوبر 2007) من قواعد المعطيات الموجودة لدى منظمة الصحة العالمية والصندوق العالمي لمكافحة الإيدز والسل والملاريا.

الموجودات

لم يجد الباحثون ارتباطاً بين السعر وبين كمية المشتريات في 19 من الاستمارات العلاجية بالأدوية المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية من بين 24 استمارة. أما بالنسبة للاستمارات الخمس المتبقية فقد كانت مشتريات الكميات الكبيرة يرافقها نقص في الثمن مقداره 4 – 21% من مشتريات الكميات المتوسطة أو القليلة. كما أن تسعة من الأدوية الجنيسة الثلاثة عشرة المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية، كانت أسعارها أقل بمقدار يتراوح بين 6 و36% من تلك الأدوية الجنيسة التي اشتريت عبر مبادرة مؤسسة كلينتون لمكافحة الإيدز. وكانت أسعار 15 من بين 18 دواء من الأدوية ذات الاسم التجاري المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية أعلى سعراً بمقدار 23 – 498% بالنسبة للمشتريات المؤمنة وفقاً لنظام الأسعار التفاضلية مقارنةً مع أسعار مشتريات أدوية جنيسة تمت خارج مبادرة مؤسسة كلينتون لمكافحة الإيدز. إلا أن دواءين يحملان اسمين تجاريين من الأدوية المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية قد تم تسعيرهما، وفقاً لنظام الأسعار التفاضلية، أقل بمقدار 63% و73% من المكافئات الجنيسة التي أمنت خارج مبادرة مؤسسة كلينتون لمكافحة الإيدز.

الاستنتاج

إن شراء كميات كبيرة لا يؤدي بالضرورة إلى خفض أسعار الأدوية المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية. ورغم أن الخطط المعمول بها حالياً للشراء المجمّع ستزيد من كميات الشراء، فإن التوفير غير مؤكَّد وينبغي أن تتم موازنتها مع تكاليف البرامج. وقد أدَّى الشراء عبر طرف ثالث هو مبادرة مؤسسة كلينتون لمكافحة الإيدز إلى خفض أسعار الأدوية الجنيسة المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية، وكانت الأدوية الجنيسة أقل ثمناً من الأدوية ذات الاسم التجاري المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية والتي تم شراؤها وفق نظام الأسعار التفاضلية إلا في الأحوال التي تكون المنافسة فيها بالنسبة للأدوية الجنيسة، قليلة. وينبغي دراسة الاستراتيجيات البديلة لخفض أسعار الأدوية المضادة للفيروسات القهقرية، مثل توحيد إدارة النظم المالية وتحسين التكهُّن بالطلب وإزالة العوائق أمام الأدوية الجنيسة.

Introduction

New goals on providing universal access to HIV/AIDS services by 2010 were announced in 2007 by WHO, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).1 The need for life-long HIV/AIDS treatment and the high cost of antiretroviral (ARV) agents present challenges to achieving and sustaining universal access targets. During the past decade, various large-scale strategies have been used to reduce ARV prices in low- and middle-income countries. This paper focuses on three price-reduction strategies: procurement arrangements designed to increase purchase volumes, third-party price negotiation for generic ARVs and differential pricing for branded ARVs.

The first strategy, procurement arrangements to increase purchase volumes, often involves pooled procurement schemes that group multiple purchasers into a single purchasing unit in the hope that economies of scale will lead to lower prices. A pooled procurement mechanism is currently being developed at the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund).2,3

The second large-scale strategy involves third-party consultation and price negotiation with generic ARV suppliers, a practice introduced by the Clinton Foundation HIV/AIDS Initiative (CHAI) in 2003.4 In practice, CHAI attempts to make ARVs more affordable by negotiating price ceilings that reflect suppliers’ costs plus reasonable and sustainable profit margins.4 Moreover, CHAI furthers this strategy by providing direct technical assistance to some suppliers to help lower their production costs.4 The resulting ceiling prices are made available to all members of the CHAI procurement consortium.4 Countries that wish to become part of the consortium sign a memorandum of understanding with CHAI and manufacturers are required to offer ARVs to these countries at prices equal to or less than CHAI-negotiated ceiling prices.4

The third strategy involves differential pricing, sometimes referred to as price discrimination or tiered pricing. In 2000, the Accelerating Access Initiative, a collaborative endeavour of multiple international agencies and pharmaceutical manufacturers, first launched such a strategy for ARVs.5 Whereas CHAI price negotiation deals exclusively with generic ARVs, differential pricing pertains to branded ARVs and was introduced at a time when generic ARVs were not yet available. Under differential-pricing schemes, each manufacturer selects certain branded ARVs to be sold to low- and middle-income countries at prices lower than those charged in high-income countries.5 Each manufacturer determines which countries are eligible to purchase ARVs under their differential-pricing scheme, with eligibility typically being based on the country’s income level and prevalence of HIV infection.

Data on transactions involving the procurement of ARVs with donor funds are made public by the Global Fund and WHO.6,7 The Global Fund and WHO databases can be used to monitor and examine the global ARV marketplace. Although some analyses of these databases have been carried out,8–11 none has examined the global impact of the various ARV price-reduction strategies mentioned above. We used the Global Fund and WHO databases to test the following hypotheses on three different ARV price-reduction strategies: prices for high-volume ARV purchases are less than for low-volume purchases; prices for generic ARVs purchased within the CHAI consortium are less than for generic ARVs purchased outside the consortium; and prices for branded ARVs purchased under differential-pricing schemes are equal to or less than those for generic ARVs.

Methods

Data sources

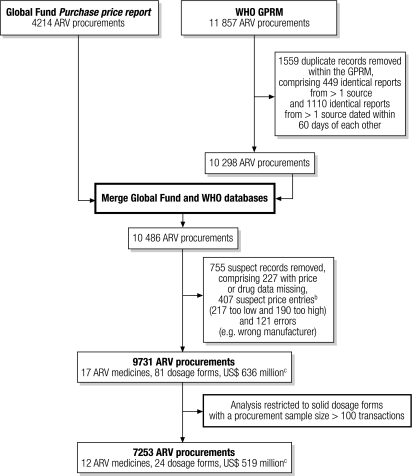

We used data on ARV procurement transactions from the Global Fund Price Reporting Mechanism and the WHO Global Price Reporting Mechanism (GPRM) for the period between July 2002 and October 2007.6,7 The Global Fund posts details of ARV procurements reported by their international aid recipients on the web-based Price Reporting Mechanism.6 In addition, procurement data from the Global Fund as well as procurement data provided by WHO country offices, international organizations, procurement agencies and others are posted by WHO on the web-based GPRM, which serves as the global repository for data on ARV procurement.7,12 As shown in Fig. 1, data from these two sources were combined in a way that allowed us to remove any overlap in procurement data either within or between data sources. We also made sure that the data concerned valid transactions by removing incomplete records, erroneous reports (e.g. the wrong manufacturer) and suspect data entries with extremely low or high prices. Suspect data entries were identified using standard box-plot equation intervals.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart illustrating the removal of duplicate, erroneous and suspect records from combined dataa on the procurement of ARVs in solid form between July 2002 and October 2007a

ARV, antiretroviral; Global Fund, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; GPRM, Global Price Reporting Mechanism; US$, United States dollar.

a Data sources were the Global Fund Purchase price report and WHO’s GPRM.

b A price was regarded as a low price outlier if it was < Q1 – 3 × IQR and as a high price outlier if it was > Q3 + 3 × IQR, where Q1 was the 25th percentile of price, Q3 was the 75th percentile of price and IQR was the width of the interquartile range.

c The value of procurements before adjustment based on the United States annual consumer price index.

For the current analysis, we restricted our data set to ARV products supplied in a solid form, such as tablets, capsules and caplets. To focus on the more commonly used ARVs and to ensure reasonable sample sizes for regression models, we chose ARVs with procurement sample sizes of 100 or more (i.e. the ARV was purchased at least 100 times between July 2002 and October 2007). As a result, the analysis included 7253 procurement transactions for 24 ARV dosage forms. These 24 dosage forms provide the basis for the regimens commonly used for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV as well as for first- and second-line treatment of HIV/AIDS. They belong to three major classes of ARV: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors. We adjusted all prices, which were reported by the Global Fund and WHO in United States dollars (US$), to the July 2006–June 2007 time period using the United States annual consumer price index.13

The public data sources provided basic transaction information; however, to examine determinants of price, we created additional independent variables, namely, differential price-eligibility, CHAI-eligibility, volume and quality. Whether or not a branded ARV purchase was eligible for differential pricing was determined using information obtained from the 2001 to 2008 editions of Untangling the web of price reductions, published by Médecins Sans Frontières.14 Whether or not a generic ARV purchase was classified as a CHAI or a non-CHAI purchase was determined from information provided by CHAI on when countries joined the consortium and from CHAI ARV price lists, which indicated the manufacturers and products subject to agreements over the previous 5 years (conversation and material provided by D Ellis, CHAI, December 2007). Relevant ARV purchases were considered eligible for CHAI or differential pricing 6 months after the announcement of new prices offered via CHAI or differential-pricing schemes. This was done to account for the likely scenario that a country may have been locked into a previously negotiated price for an annual procurement cycle and may, therefore, have been unable to access newly announced prices. Volume was categorized as low, medium or high on the basis of thirds of the specific volume distribution for each ARV dosage form. The quality variable indicated whether an ARV was approved or not by a universally accepted, stringent regulatory body. Approved ARVs were those classified as prequalified by WHO or those approved or tentatively approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).15,16 A summary of the number and total value of purchases of individual ARVs and their corresponding volume categories is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Number and total value of individual ARV purchases between July 2002 and October 2007.

| Antiretroviral | Total number of purchases | Total value of all purchases (US$)a | Volume of ARV doses purchasedb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |||||

| (lowest third) | (middle third) | (highest third) | |||||

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) | |||||||

| Abacavir 300 mg | 247 | 9 612 930 | 300–6 120 | 6 240–37 140 | 39 000–781 200 | ||

| Didanosine 100 mg | 172 | 1 854 615 | 60–3 600 | 3 720–29 880 | 30 000–324 480 | ||

| Didanosine 200 mg | 115 | 1 693 087 | 240–3 960 | 4 020–27 000 | 28 680–343 260 | ||

| Didanosine 400 mg | 126 | 4 648 567 | 90–2 310 | 2 400–15 390 | 15 540–332 340 | ||

| Lamivudine 150 mg | 580 | 15 911 293 | 120–28 080 | 28 320–179 160 | 180 000–5 904 000 | ||

| Stavudine 20 mg | 113 | 461 819 | 56–10 800 | 12 000–48 600 | 51 600–840 000 | ||

| Stavudine 30 mg | 389 | 4 018 395 | 60–11 880 | 12 000–120 000 | 121 440–5 790 000 | ||

| Stavudine 40 mg | 382 | 5 745 885 | 120–9 600 | 9 900–94 696 | 95 200–4 373 100 | ||

| Stavudine 30 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 257 | 43 916 698 | 240–6 900 | 7 200–48 000 | 51 000–401 346 960 | ||

| Stavudine 40 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 206 | 1 389 119 | 27–4 020 | 4 080–24 120 | 24 180–1 500 000 | ||

| Tenofovir 300 mg | 137 | 8 800 097 | 89–9 000 | 10 140–45 600 | 45 900–1 440 000 | ||

| Zidovudine 100 mg | 232 | 2 734 390 | 200–7 400 | 7 500–42 800 | 43 200–3 550 000 | ||

| Zidovudine 300 mg | 311 | 6 016 544 | 120–11 580 | 12 000–47 280 | 48 000–1 600 020 | ||

| Zidovudine 300 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 691 | 79 642 912 | 120–30 000 | 32 040–230 040 | 231 000–137 648 400 | ||

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) | |||||||

| Efavirenz 50 mg | 170 | 801 118 | 90–5 400 | 5 700–31 500 | 34 500–454 500 | ||

| Efavirenz 200 mg | 350 | 13 661 610 | 90–9 000 | 9 270–45 630 | 45 720–2 563 200 | ||

| Efavirenz 600 mg | 616 | 73 531 130 | 60–12 990 | 13 020–110 970 | 112 440–6 693 480 | ||

| Nevirapine 200 mg | 727 | 32 204 756 | 60–19 020 | 19 500–120 000 | 120 120–12 534 000 | ||

| Fixed-dose combination of NRTIs and an NNRTI | |||||||

| Stavudine 30 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg plus nevirapine 200 mg | 392 | 145 267 223 | 420–25 620 | 27 000–262 200 | 282 000–486 404 460 | ||

| Stavudine 40 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg plus nevirapine 200 mg | 335 | 17 617 177 | 360–18 960 | 19 080–92 520 | 92 760–3 957 093 | ||

| Protease inhibitors | |||||||

| Indinavir 400 mg | 164 | 7 573 719 | 540–27 000 | 27 900–112 680 | 115 200–1 602 000 | ||

| Lopinavir 133.3 mg plus ritonavir 33.3 mg | 217 | 18 281 938 | 138–19 440 | 21 600–88 200 | 90 000–2 640 780 | ||

| Nelfinavir 250 mg | 214 | 21 941 575 | 540–33 750 | 34 290–167 400 | 175 500–4 185 000 | ||

| Ritonavir 100 mg | 110 | 1 908 638 | 336–6 720 | 7 140–45 360 | 47 040–360 024 | ||

ARV, antiretroviral; US$, United States dollar. a Value before adjustment based on the United States annual consumer price index. b The purchase volume was categorized as low, medium or high using thirds for the specific purchase volume distribution for each ARV dosage form.

Analytic approach

We used existing and newly created variables to examine determinants of the price of ARVs. We devised separate regression models for each of the 24 ARV dosage forms by using generalized estimating equation linear regression to take account of the correlated nature of the data. Price, our dependent variable, was non-normally distributed; therefore, we adopted the natural log of the price per tablet or capsule as our outcome measure. Data were clustered by country and year of purchase to take into account potential correlations in price within these variables. Candidate predictor variables were: the International Chamber of Commerce standard trade definition (Incoterm),17 the World Bank Country Income Classification,18 eligibility for CHAI or differential pricing14 (D Ellis, CHAI, personal communication, 2007), FDA-approved or WHO-prequalified ARV,15,16 purchase volume third, and analytic year of purchase. For each predictor variable we calculated the percentage change in price for each one-unit increase in the predictor variable by exponentiating the β coefficients from the regression equations and subtracting 1. Multivariate analysis was used to determine the effect of purchase volume, eligibility for CHAI and eligibility for differential pricing on ARV price. The results of the multivariate analysis are presented as percentage price differences between categories, with a negative percentage difference indicating that the ARV price in the comparator group is less than that in the reference category and a positive percentage difference indicating the opposite. Price differences with P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant and are highlighted in boldfaced type in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2. Effect of purchase volume, divided into thirds, on the price of individual ARVs as determined by regression analysis. The median unadjusted annual price per person of individual products during July 2006–June 2007 is shown for reference.

| Antiretroviral | Median unadjusted annual price per persona |

Price difference from regression analysisb (%) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-volume purchases (US$) | Medium-volume purchases (US$) | Low-volume purchases (US$) | High-volume vs medium-volume purchases | High-volume vs low-volume purchases | |||||||

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) | |||||||||||

| Abacavir 300 mg | 438 | 453 | 540 | 3 | –1 | ||||||

| Didanosine 100 mgc | 115 | 115 | 88 | 4 | –2 | ||||||

| Didanosine 200 mg | 314 | 241 | 226 | 4 | –3 | ||||||

| Didanosine 400 mg | 303 | 434 | 288 | –12 | –4 | ||||||

| Lamivudine 150 mg | 51 | 51 | 58 | 2 | –2 | ||||||

| Stavudine 20 mgc | 15 | 15 | 33 | –2 | –2 | ||||||

| Stavudine 30 mg | 29 | 29 | 37 | 6 | –5 | ||||||

| Stavudine 40 mg | 37 | 37 | 37 | 4 | 12 | ||||||

| Stavudine 30 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 66 | 73 | 66 | 0.7 | 5 | ||||||

| Stavudine 40 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 80 | 73 | 66 | –2 | 6 | ||||||

| Tenofovir 300 mg | 208 | 208 | 226 | 7 | –7 | ||||||

| Zidovudine 100 mgc | 51 | 55 | 58 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Zidovudine 300 mg | 124 | 117 | 146 | –4 | –5 | ||||||

| Zidovudine 300 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 139 | 168 | 139 | –1 | –7 | ||||||

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) | |||||||||||

| Efavirenz 50 mgc | 161 | 161 | 161 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Efavirenz 200 mgc | 111 | 131 | 77 | –7 | –6 | ||||||

| Efavirenz 600 mg | 234 | 245 | 245 | –4 | –7 | ||||||

| Nevirapine 200 mg | 58 | 55 | 58 | –3 | –3 | ||||||

| Fixed-dose combination of NRTIs and an NNRTI | |||||||||||

| Stavudine 30 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg plus nevirapine 200 mg | 95 | 102 | 102 | –5 | –5 | ||||||

| Stavudine 40 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg plus nevirapine 200 mg | 131 | 102 | 102 | –11 | –16 | ||||||

| Protease inhibitors | |||||||||||

| Indinavir 400 mg | 394 | 511 | 496 | –6 | –7 | ||||||

| Lopinavir 133.3 mg plus ritonavir 33.3 mg | 920 | 1007 | 591 | –13 | –21 | ||||||

| Nelfinavir 250 mg | 1059 | 1113 | 1059 | –4 | 3 | ||||||

| Ritonavir 100 mg | 80 | 88 | 91 | –8 | 6 | ||||||

ARV, antiretroviral; US$, United States dollar. a Median price per person per year during July 2006–June 2007. b Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown in boldface type. c Paediatric dose for children weighing 10 kg.

Table 3. Differences between the prices of generic ARVs purchased under CHAI, generic ARVs not purchased under CHAI and differentially priced branded ARVs.

| Antiretroviral | Median unadjusted annual price per persona |

Price difference from regression analysisb (%) |

Median unadjusted annual price per persona |

Price difference from regression analysisb (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

||||

| Non-CHAI generic ARV (US$) | CHAI generic ARV (US$) | CHAI vs non‑CHAI generic ARV | Differentially priced branded ARV (US$) | Differentially priced branded product vs non‑CHAI generic product | ||||

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) | ||||||||

| Abacavir 300 mg | 515 | 358 | –15** | 635 | 60** | |||

| Didanosine 100 mgc | 293 | NA | NA | 115 | 30* | |||

| Didanosine 200 mg | 190 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Didanosine 400 mg | 176d | NA | NA | 288 | –63* | |||

| Lamivudine 150 mg | 51 | 44 | –5 | 73 | 51** | |||

| Stavudine 20 mgc | 15 | 11 | –36** | 33 | 137** | |||

| Stavudine 30 mg | 37 | 22 | –18* | 73 | 100** | |||

| Stavudine 40 mg | 37 | 22 | –9 | 73 | 98** | |||

| Stavudine 30 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 73 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Stavudine 40 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 73 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Tenofovir 300 mg | NA | NA | NA | 208 | NA | |||

| Zidovudine 100 mgc | 58 | 37 | –18* | 117 | 112** | |||

| Zidovudine 300 mg | 131 | 110 | –6* | 226 | 43** | |||

| Zidovudine 300 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg | 139 | 124 | –13** | 241 | 44** | |||

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) | ||||||||

| Efavirenz 50 mgc | 117 | NA | NA | 161 | 48** | |||

| Efavirenz 200 mgc | 77 | 77 | –3 | 131 | 47** | |||

| Efavirenz 600 mg | 245 | 150 | –27* | 296 | 23* | |||

| Nevirapine 200 mg | 66 | 44 | –9* | 438 | 498** | |||

| Fixed-dose combination of NRTIs and an NNRTI | ||||||||

| Stavudine 30 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg plus nevirapine 200 mg | 102 | 95 | –11* | NA | NA | |||

| Stavudine 40 mg plus lamivudine 150 mg plus nevirapine 200 mg | 102 | 80 | –11 | NA | NA | |||

| Protease inhibitors | ||||||||

| Indinavir 400 mg | 380 | NA | NA | 467 | 29* | |||

| Lopinavir 133.3 mg plus ritonavir 33.3 mg | 4358 | NA | NA | 591 | –73** | |||

| Nelfinavir 250 mg | 931 | NA | NA | 1095 | 44** | |||

| Ritonavir 100 mg | 102 | NA | NA | 80 | –35 | |||

*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.0001 (calculated using generalized estimating equation linear regression). ARV, antiretroviral; CHAI, Clinton Foundation HIV/AIDS Initiative; NA, not applicable; US$, United States dollar. a Median price per person per year during July 2006–June 2007. b Statistically significant differences are shown in boldface type. c Paediatric dose for children weighing 10 kg. d Adjusted median price per person per year based on price during July 2005–June 2006.

To provide a context for interpreting the findings of the regression analysis, Table 2 also lists raw, unadjusted ARV prices for July 2006–June 2007 together with the results of the regression analysis. These raw prices are described in terms of the median annual price per person of individual products (i.e. median price per tablet or capsule × daily dose × 365 days). For ARVs for adults, we used doses for individuals weighing ≥ 60 kg; for paediatric ARVs, we used doses for children weighing 10 kg, as recommended by WHO.19–21

Results

Effect of purchase volume

We detected no statistically significant association between purchase volume and price at the country level for 19 of the 24 (79%) dosage forms after adjusting for other variables in the regression model (Table 2). For two of the five dosage forms for which there was a significant association between volume and price, the prices for high-volume purchases were 7% and 21% less, respectively, than for low-volume purchases. For two other dosage forms, the prices for high-volume purchases were less than for both medium- and low-volume purchases, with differences being 4% and 5% less, respectively, for one ARV and 11% and 16% less, respectively, for the other. The other dosage form was 6% less expensive for high-volume purchases than for medium-volume purchases.

Generic prices for CHAI and non‑CHAI purchases

We identified 13 generic ARV products for which CHAI had negotiated price ceilings with manufacturers on behalf of CHAI country consortium members. We compared the actual prices paid for generic ARVs by CHAI and non-CHAI countries and found that the price of 9 of 13 (69%) dosage forms was significantly lower for CHAI purchases than non-CHAI purchases (Table 3, columns A, B and C). Overall, CHAI prices were less than non-CHAI prices by 6–36% (Table 3, column C).

Generic and differentially priced branded prices

Of the 24 (79%) solid ARV dosage forms analysed, 19 were available to some countries through differential-pricing schemes provided by the brand-name manufacturer (Table 3, column D). Of these 19 (95%) differentially priced branded products, 18 could be compared in price with non-CHAI generics (Table 3, column E). For 15 of these 18 (83%) dosage forms, purchases made under differential-pricing schemes were significantly more expensive than non-CHAI generic purchases, with price differences ranging from 23–498% (Table 3, column E). For two of the 18 (11%) ARV dosage forms, prices for differentially priced branded ARVs were 63% and 73% lower, respectively, than prices for non-CHAI generic ARVs. The price difference between the differentially priced branded product and the non-CHAI generic version was significant for all 18 ARV dosage forms, apart from ritonavir 100 mg.

Discussion

We combined data from medicine procurement databases made public by the Global Fund and WHO with information from other sources to evaluate price-reduction strategies for ARVs for the first time and found some surprising results. The most counterintuitive finding is the absence of an association between purchase volume and price at the country level for 19 of the 24 ARV dosage forms (see Table 2). Although conventional business practice suggests that making a large-volume purchase at the country level will result in a discounted price, this appears not to be the case for these medicines.

The Global Fund has recommended the facilitation of voluntary pooled procurement as a means of increasing procurement efficiency.2,3 Pooled procurement of ARVs will result in much larger purchase volumes than those explored in our study, but it remains difficult to quantify exactly how much money could be saved by pooling purchase orders. Any estimate of potential savings resulting from pooled procurement must be balanced against the programmatic costs of establishing and managing the procurement systems required. While some surveys and desk reviews have described potential pooled procurement mechanisms in developing countries,22,23 insufficient empirical research has been carried out to validate pooled procurement and identify the conditions under which it can operate most efficiently. Pooled procurement may certainly offer other potential supply chain efficiencies beyond increased purchase volumes, but it should be carefully monitored to ensure such efficiencies are achieved.

While interventions for improving procurement efficiency are certainly desirable, they should be designed to develop and increase the technical capability for managing these procurement systems in the countries concerned. New procurement arrangements, whereby donors and international organizations act on behalf of countries for selected diseases, may fail to help strengthen those countries’ health systems. Lastly, pooled purchase arrangements will reduce the number of purchasers and could, therefore, result in a dramatic restructuring of the current global ARV market. Econometric modelling should be used to predict the potential impact of pooled procurement on the global ARV market and the findings should be used to inform the design of these schemes.

Third-party price negotiation by CHAI shows promise. Overall, the price of generic ARVs was less for CHAI purchases than for non-CHAI purchases. However, price differences between CHAI and non-CHAI purchases varied widely across ARVs. While price differences were as high as 27–36% for some ARVs, for others they were less than 10%. The most dramatic price differences between CHAI and non-CHAI generic ARVs were typically observed in the 1 to 2 years immediately following negotiations with suppliers. We recommend, therefore, that additional time-series research be carried out to explore the reasons why these price differences diminish over time and their potential impact on the overall ARV market.

Traditional approaches using differential-pricing schemes have not decreased the prices of branded ARVs to levels that can make these drugs compete with generic ARVs in most scenarios, which suggests that differential pricing alone is insufficient for achieving and sustaining universal access to HIV/AIDS treatment. In this study, nearly all the branded ARVs offered under differential pricing schemes were more expensive than the equivalent generics. There were a few exceptions where generic competition was lacking and differential pricing schemes for branded ARVs offered substantial cost savings over generic ARVs. The most notable exception was for lopinavir, 133.3 mg, plus ritonavir, 33.3 mg, a branded combination purchased under a differential pricing scheme; it was 73% less expensive than its non-CHAI generic equivalent. Likewise, there may be country scenarios in which generics cannot be purchased because of patent protection or other intellectual property barriers, and differential pricing may, therefore, offer substantial cost savings. Clearly, differential pricing of ARVs coexists in an environment that now includes large-scale financing of HIV/AIDS treatment and the maturation of generic ARV markets, two forces that did not exist when the Accelerating Access Initiative began. Additional work is needed to better explain the particular role of differential pricing in providing treatment for HIV/AIDS in today’s global ARV market, with special attention paid to the impact of differential pricing on the price of first-entry generic competitors.

While this research has provided some important findings, our analysis has limitations. Because we were dealing with pre-existing data, we used a standard method to remove outliers that may have come from erroneous reports. However, we repeated our analysis with the outliers included and the results did not differ from those presented in this paper. We also repeated our regression analyses using volume fourths instead of volume thirds and found the same results. Our study examined price–volume relationships at the level of individual purchases and did not consider total volume–price relationships at the level of tender arrangements, as these data were unavailable. Indeed, countries usually tender once or twice a year for larger volumes that are delivered in the multiple smaller purchase volumes reported in the databases. Still, larger tenders are likely to involve larger individual purchase volumes, so an analysis at the tender level would probably reveal similar results. It is notable that an association between volume and price was found for 5 of the 24 ARV dosage forms. This suggests that more work is needed to better understand the exceptional conditions under which the volume purchased at the country level may determine the ARV price.

Our regression models contained many candidate variables thought to be associated with price; however, we lacked access to information on additional factors that may have an influence, such as the timeliness of payment, the lead time between when an ARV is ordered and when it is needed, the presence or absence of drug registration, and intellectual property regulation. While many pricing studies must consider purchase incentives such as bundling, rebates and discounts, we doubt that such purchase arrangements played a major role in our study of donor-funded national ARV procurements. Lastly, our study focused on ARV prices only; other programmatic costs associated with the treatment of HIV/AIDS were not considered.

The quality of medicines on the market varies within and between low-resource countries, which means that previous price research compared medicines of unequal quality. For ARVs purchased with donor funds, however, the policies of the Global Fund and the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief mandate that the purchase of ARVs is approved by the WHO Prequalification Programme, the United States FDA or other stringent regulatory authorities. The WHO Prequalification Programme in particular has increased the availability of lower-priced, high-quality generic ARVs and this has enabled us to compare the prices of ARVs of equal quality.

Alternative strategies for reducing ARV prices should be explored. For instance, financial management systems in donor and country programmes could be improved and generic competition could be promoted by removing barriers to generic entry. Improved forecasting of future demand for ARVs may result in lower prices by preventing or minimizing the need for costly emergency shipments. For ARVs such as protease inhibitors that are expensive to make and are used less often, efforts could be made to consolidate global demand by reaching a consensus on the use of one or two key compounds. Alternatively, interventions aimed at transferring technology to generic producers may result in more timely generic competition for protease inhibitors and subsequent price reductions. Lastly, existing publicly available procurement databases should be expanded and used to guide future policies aimed at increasing access to essential ARV therapies. ■

Acknowledgements

Emma Back, William Bicknell, Michael Borowitz, Mariah Boyd-Boffa, Boniface Dongmo Nguimfack, Dai Ellis, Susan Fish, Manjusha Gokhale, Bruce Larson, Libby Levison, Maureen Mackintosh, Sapna Mahajan, Audrey McIntyre, Bas Peters, Rose Radin, Michael Reich, Sydney Rosen, Dennis Ross-Degnan, Lyne Soucy, Don Thea, Anita Wagner, Saul Walker and Michael Winter.

Footnotes

Funding: United Kingdom Department for International Development through the Medicines Transparency Alliance (MeTA) Project.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector [progress report]. Geneva: WHO, UNAIDS & UNICEF; 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/universal_access_progress_report_en.pdf [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 2.Report of the thirteenth board meeting Geneva: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; 2006. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/board/14/GF-BM-14_02_Report_ThirteenthBoardMeeting.pdf [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 3.Report of the fifteenth board meeting Geneva: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; 2007. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/board/16/GF-BM16-02-Report_Fifteenth_Board_Meeting.pdf [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 4.Clinton Foundation [Internet site]. Clinton HIV/AIDS Initiative. Available from: http://www.clintonfoundation.org/explore-our-work/#/clinton-hiv-aids-initiative/ [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 5.Accelerating access initiative: widening access to care and support for people living with HIV/AIDS. Progress report Geneva: World Health Organization, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2002. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/aai/en/ [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 6.The Price Reporting Mechanism. Geneva: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; 2008. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/ [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 7.Global Price Reporting Mechanism. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/amds/gprm/en/index.html [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 8.Vasan A, Hoos D, Mukherjee JS, Farmer PE, Rosenfield AG, Perriens JH. The pricing and procurement of antiretroviral drugs: an observational study of data from the Global Fund. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:393–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.05.025684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chien CV. HIV/AIDS drugs for Sub-Saharan Africa: how do brand and generic supply compare? PLoS One. 2007;2:e278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunn AS, Fonseca EM, Bastos FI, Gruskin S, Salomon JA. Evolution of antiretroviral drug costs in Brazil in the context of free and universal access to AIDS treatment. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE. Conditional scholarships for HIV/AIDS health workers: educating and retaining the workforce to provide antiretroviral treatment in sub-Saharan Africa Mtubatuba, South Africa: University of KwaZulu–Natal; 2007. Available from: http://www.ukzn.ac.za/heard/ERG/ERGBloomPaper.pdf [accessed on 11 May 2009]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.A summary report from the Global Price Reporting Mechanism on antiretroviral drugs Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/amds/GPRMsummaryReportOct07.pdf [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 13.World Economic Outlook Database Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund; 2007. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2007/01/data/index.aspx [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 14.Untangling the web of price reductions: a pricing guide for the purchase of ARVs for developing countries [eds 1–10] Geneva: Médecins sans Frontières; 2001-2008. Available from: http://www.accessmed-msf.org/resources/key-publications/ [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 15.Approved and tentatively approved antiretrovirals in association with the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Silver Spring, MD: United States Food and Drug Administration; 2007. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/oia/pepfar.htm [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 16.World Health Organization Prequalification Programme Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://mednet3.who.int/prequal/ [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 17.Incoterms Paris: International Chamber of Commerce; 2007. Available from: http://www.iccwbo.org/incoterms/id3040/index.html [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 18.World Bank country classification Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2007. Available from: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/DATASTATISTICS/0,contentMDK:20420458~menuPK:64133156~pagePK:64133150~piPK:64133175~theSitePK:239419,00.html [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 19.Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: treatment guidelines for a public health approach [2003 revision] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/en/arvrevision2003en.pdf [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 20.Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents in resource-limited settings: towards universal access Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/artadultguidelines.pdf [accessed on 11 May 2009].

- 21.Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in infants and children: towards universal access Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/art/en/ [accessed on 11 May 2009]. [PubMed]

- 22.Center for Pharmaceutical Management. Regional pooled procurement of drugs: evaluation of programs [Submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation]. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onyango C, Aboagye-Nyame F. Readiness for regional pooled procurement of HIV/AIDS-related commodities in Sub-Saharan Africa: an assessment of 11 member countries of the Commonwealth Regional Health Community Secretariat [Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Rational Pharmaceutical Management Plus Program]. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health; 2002.