Abstract

Bicelles are a major medium form to produce weak alignment of soluble proteins for residual dipolar coupling (RDC) measurements. The obstacle to use the same type of bicelles for transmembrane proteins with solution-state NMR spectroscopy is the loss of signals due to the adhesion or penetration of the proteins into large bicelles, resulting in slow protein tumbling. In this study, weak alignment of the second and third transmembrane domains (TM23) of the human glycine receptor (GlyR) was achieved in low-q bicelles (q = DMPC/DHPC). Although protein-free bicelles with such low q would likely show isotropic properties, the insertion of TM23 induced weakly preferred orientations so that the RDC of the embedded protein can be measured. The extent of the alignment increases but the TM23 signal intensity decreases when q varied from 0.19 to 0.60. A q of 0.50 was found to be an optimal compromise between alignment and the signal-to-noise ratio. In each pair of NMR experiments for RDC measurements, the same sample and pulse sequence were used, with one being performed at high-resolution magic-angle spinning to obtain pure J-couplings without RDC. A meaningful structure refinement in bicelles was possible by iteratively fitting of the experimental RDCs to the back-calculated RDCs using the high-resolution NMR structure of GlyR TM23 in trifluoroethanol as the starting template. The combination of this method with the conventional high-resolution NMR in the membrane-mimicking solvent-water mixtures offers an attractive way to derive structural information for membrane proteins in their native environment.

Keywords: Glycine receptor, magic angle spinning (MAS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), bicelles, residual dipolar coupling (RDC)

Introduction

Angular dependence of anisotropic spin interactions with respect to an external magnetic field in high-resolution protein NMR spectroscopy, such as residual dipolar couplings (RDCs), can provide valuable structure information. An essential requirement for the measurements of RDCs is that the sample must be in a weakly aligned environment. Several alignment methods, each with strengths and limitations, have been developed, including organic liquid crystals1, the filamentous bacteriophage Pf12, tobacco mosaic virus3, strain-induced alignment in gels (SAG)4, and bicelles in liquid crystalline phase5,6. Bicelles are widely used for soluble proteins in solution NMR7 and have also been shown to be an excellent medium for the alignment of membrane proteins for solid-state NMR measurements8. The extent of alignment depends on the temperature, the total lipid concentration, and the ratio of the lipid constituents9. The ratio of long-chain to short-chain alkyl components, q, is a determinant of bicelle alignment after the concentration of lipids and the experimental temperature are chosen. The long-chain dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) and the short-chain detergent dihexanoylphosphatidylcholine (DHPC) are often paired for making the bicelles. Bicelles with 0.5 < q < 3.0 normally show slow anisotropic reorientation10. Due to their hydrophobic nature, membrane proteins are likely to attach to or penetrate into bicelles, and the solution-state NMR signals of these membrane proteins are usually broad because of significantly reduced reorientation diffusion of the large-size bicelles. Bicelles having q ≤ 0.5 were thought to exhibit isotropic micelle properties and not to show apparent alignment in a magnetic field8,11. However, in the presence of an embedded transmembrane protein, this may not be the case. Studies have shown that bicelles with q = 0.5 contain a true bilayer, with their morphology and bilayer organization being the same as bicelles of q > 2 and thus making them better membrane-mimetic media than detergent micelles11. It is therefore possible that bicelles with q < 1 can be anisotropic and weakly aligned in strong magnetic fields. Here we report that the insertion of transmembrane domains of the human glycine receptor (GlyR) can induce and enhance anisotropic orientation of bicelles with relatively low q ratios (q = DMPC/DHPC = 0.4 to 0.6). The extent of alignment increases but the signal intensity of the transmembrane segment decreases when the q ratio varied from 0.19 to 0.6. A compromised q value of 0.5 was found to offer the optimized sample alignment and spectral signal-to-noise ratio. In each pair of NMR experiments for RDC measurements, the same sample and NMR pulse sequence can be used, with one in the pair being performed at high-resolution magic-angle spinning (MAS) for the assessment of pure J-couplings without RDC. Important structural information on the embedded proteins can thus be obtained without the complications potentially associated with other methods where different alignment media are used to derive the RDC values.

Experimental

Sample Preparation

A segment including the second and third transmembrane domains (TM23) of the human glycine receptor α1 subunit (LPARV GLGIT TVLTL TTQSS GSRAS LPKVS YVKAI DIWLA VCLLF VFSAL LEYAA VNFVS R) was expressed using the Novagen pET-31b(+) system (Novagen, Milwaukee, WI) and uniformly labeled either with 15N or with 15N and 13C. The details of the protein expression and purification have been reported previously12. The second transmembrane (TM2) segment with selectively 15N-labeled Gly and Leu (PARVG LGITT VLTMT TQSSG SRAS) and the third transmembrane (TM3) segment with selectively 15N-labeled Ala and Leu (CVSYV KAIDI WMAVC LLFVF SALLE YAAVN FVSRQ KKKK) were obtained using solid phase peptide synthesis. The amino acids in bold represent the 15N-labeled residues. 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) and 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DHPC) in a 20 mg/mL CHCl3 solution were purchased from Avanti (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL).

The desired amount of peptides was pre-dissolved in 40 µl trifluoroethanol before mixed with appropriate amounts of DMPC and DHPC. The solution mixture was then dried to a thin film under a stream of nitrogen gas and vacuumed overnight to remove residual organic solvents. The molar ratio of peptide-to-lipid was 1:200 for TM23 and 1:250 for TM2 and TM3, respectively. The q ratio (DMPC/DHPC) of bicelle was varied from 0.19 to 2.00. The high-resolution NMR sample was prepared by re-hydrating the dried mixture of peptide/DMPC/DHPC with 10% D2O and 90% H2O (v/v) containing 0.5 mM of DSS for chemical shift reference. The final concentrations of peptides were between 1 to 1.5 mM. The sample volume used in a 5-mm Shigemi tube or a MAS rotor was ~300 µL or ~65 µL, respectively.

NMR experiments

NMR experiments were performed at 35°C on two Bruker Avance 600-MHz spectrometers with 600.03 or 600.43 MHz for 1H and 60.80 or 60.84 MHz for 15N. The spectrometers are equipped with a triple resonance cryo probe, a TXI probe, and a high-resolution MAS probe (hr-MAS). The observed 1H chemical shift was referenced to the internal DSS.

For the TXI and cryo probe, typical 90° pulses are 8, 38, and 18 µs for 1H, 15N, and 13C, respectively. For the hr-MAS probe, the typical 90° pulses are 6, 14, and 15 µs for 1H, 15N, and 13C, respectively. 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired with 1024(1H)×128(15N) or 1024(1H)×512(15N) complex points, with spectral width of 10 ppm for 1H, 24 ppm for 15N, and 16 to 64 transients for each time increment. 3D NOESY-HSQC with a mixing time of 150 ms was acquired in 1024(1H)×40(15N)×128(1H) complex points. Chemical shift assignment of TM23 in bicelles with q = 0.5 was carried out using a suite of 3D experiments, including HNCA, HNCOCA, HNCO, HNCACB, CBCACONH, HBHANH, and HBHACONH. Watergate pulse scheme was applied for the suppression of the solvent peak. States-TPPI or Echo-Antiecho methods were used for quadrature detection in the indirect dimensions. All data sets were processed using nmrPipe software13, and analyzed with Sparky14 or NMRView software15.

The extent of residual alignment for the transmembrane segments was quantified using the IPAP sequence16. 15N-1H IPAP16 spectra were acquired in 1024×1024 complex points with spectral width of 10 ppm for 1H, 24 ppm for 15N, and 64 transients for each t1 increment. The RDC values of 13Cα–1Hα and 13Cα–13C’ were acquired from 3D HNCO-IPAP experiments17,18 in 1024×40×128 complex points with spectral width of 10 ppm for 1H, 24 ppm for 15N, and 22 ppm for 13C, and 16 transients for each t1 increment. The corresponding isotropic J-couplings were obtained by re-acquiring IPAP measurements on the same sample using the high-resolution magic angle spinning. A typical sample spinning rate was 4–5 kHz. The RDC values were calculated from the paired splitting in two experiments with and without the sample spinning.

Structural refinement

Using the lowest-energy structure of TM23 in TFE (PDB: 1VRY)12 as the initial structure template, the distance constraints were generated for atoms within 5 Å from each other and given a variance of ±0.5 Å along with the dihedral angle restraints. These restraints were then combined with the experimental RDC restraints obtained in the bicelles to generate refined structures of TM23 in bicelles. The refinement was performed using the slow cooling simulated annealing protocol in the torsion angle space implemented in Xplor-NIH,19,20 with RDC restraints weighted more heavily. The bath was initially set at 3000 K and allowed to cool to 25 K with a temperature step of −12.5 K. The annealing used the torsion angle dynamics, allowing the axial (Da) and rhombic (R) components of the alignment tensor to vary, followed by the Cartesian coordinate minimization during the final step. In order to simultaneously determine the alignment tensor orientation during the simulated annealing, a pseudo molecule was introduced with four artificial atoms representing the molecule origin and each of the three principle axes of the alignment tensor, as described previously.19,21 The refinement protocol in Xplor-NIH adds two additional pseudo atoms to encode the Da and R values as a function of the axial and azimuthal angles, respectively.22 The RDC restraints are imposed by including a target function of a quadratic harmonic potential, which is proportional to the square of the difference between the calculated and observed RDC values. The RDC force constant varied from 0.05 to 5 kcal mol−1Hz−2 during the cooling and simulated annealing. The RDC with respect to an N-H bond vector is given by7:

| (1) |

where Da is the magnitude of the axial component of the molecular alignment tensor, R is the rhombicity, and (θ, ϕ) are the N-H vector orientation relative to the alignment tensor. The Da and R output from Xplor-NIH is compared to that determined using the histogram method23. A total of 100 structures were calculated by using this protocol, wherein the 20 lowest energy structures were used to generate a standardized average structure. The best-fit comparison between experimental RDC values and the initial template structure of TM23 in TFE was performed using the program PALES24.

Results and discussion

Demonstration of alignment using low-q bicelles

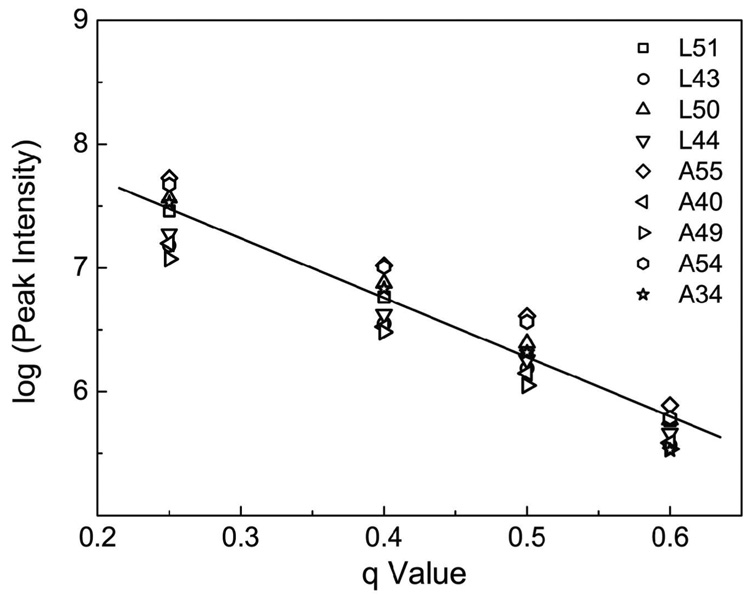

The 15N-1H HSQC peak intensities of the Ala and Leu selectively-labeled GlyR TM3 decreased gradually as the bicelle q varied from 0.25 to 0.60, as shown in Fig. 1. A further increase of the q values to 1.0 was characterized by broad signals and missing peaks. There was eventually no quantifiable signal at q = 2. These results suggest that the transmembrane segment TM3 is indeed inserted inside the bicelle membrane. An increase in the bicelle q ratio leads to the formation of larger bicelle disks that consequently decrease the reorientation of the bicelles. The proteins that attached to or penetrated in the bicelles would experience a much slower tumbling rate. More anisotropic interactions in these proteins would be expected, resulting in much broader NMR signals. The best compromise that resulted in non-zero RDC and at the same time preserved adequate NMR signals for the TM3 in bicelle was found at q = 0.50. The same q ratio was found also suitable for measuring the RDC values for TM23 (see below).

Figure 1.

Dependence of 15N-1H HSQC peak intensities of the truncated, Ala-and-Leu-labeled, third transmembrane domain (TM3) of human glycine receptor on bicelle q ratios from q = 0.25 to q = 0.60 (q is the ratio of DMPC to DHPC). The intensities decrease with increase q, confirming that TM3 is embedded in bicelles.

In contrast to the TM3, the truncated TM2 with selectively 15N-labeled Leu and Gly exhibits highly resolved 15N-1H HSQC spectra. The peaks of TM2 remain sharp even up to a bicelle q ratio of 2.0 (data not shown). This observation suggests that the isolated TM2 (i.e., not linked to TM3) is either not entirely embedded inside the bicelles or loosely associated with each other so that it undergoes isotropic motion even at a high q ratio. This might be due to the highly polar nature of TM2 (~50% polar residues) compared to the much more hydrophobic nature of TM3 (~27% polar residues). Although interaction of TM2 with bicelles was evidenced by the steady downfield shift of Leu6 resonance with increasing q values (data not shown), the truncated TM2 nevertheless showed no appreciable alignment in the presence of bicelles.

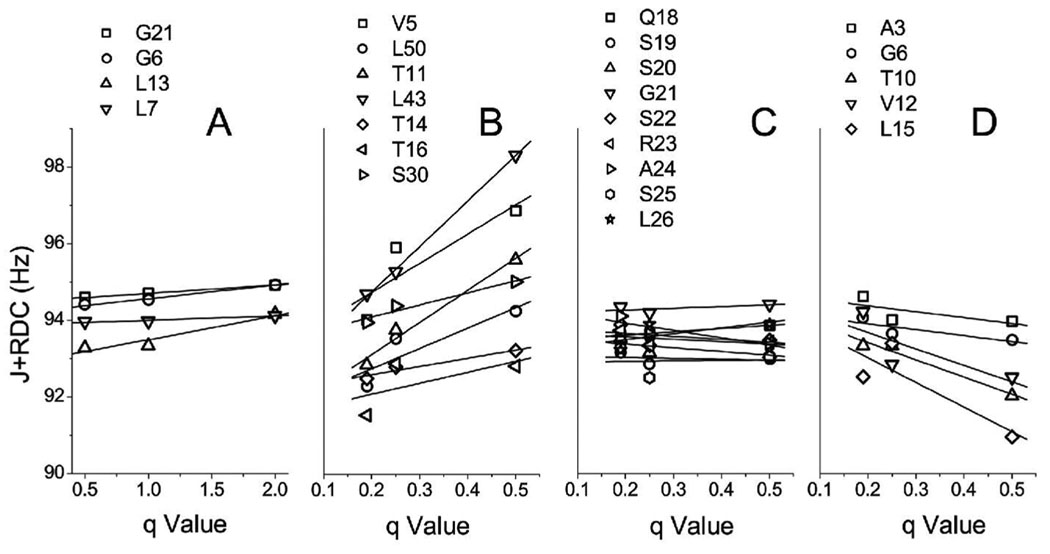

The dependence of the J+RDC splitting of TM2 and TM23 on the q ratio is presented in Fig. 2. As shown in Fig. 2A, the J+RDC splitting for the truncated TM2 is insensitive to the variation of the q values in the range of 0.5 to 2.0. The result is consistent with the observation of sharp resonance peaks of the TM2 even at q = 2.0 with no appreciable magnetic alignment at lower q ratios. A subtle increase in J+RDC splitting at q = 2.0 might result from the same type of induced alignment by steric or electrostatic forces as revealed in previous studies with globular proteins6,7,9,25.

Figure 2.

(A) Plot of RDC+J splittings of the truncated, Gly-and-Leu-labeled, second transmembrane domain (TM2) of human glycine receptor as a function of q ratios from q = 0.5 to q = 2.0. No significant changes in the splittings over a large range of q suggest that the truncated TM2 is not fully embedded in the bicelles. In contrast, the 15N uniformly-labeled TM23 shows a strong RDC+J dependence on q for residues in both the TM2 and TM3 domains (B and D), indicating a linear increase in the RDC amplitude contribution to the splittings from q = 0.25 to q = 0.50 and hence weak alignment of the imbedded protein at q > 0.2. The residues in the loop linking TM2 and TM3 are not sensitive to q (C), suggesting that these residues are highly mobile and possibly located outside the bicelle membrane.

The TM23 segment comprises two transmembrane domains, the TM2 (residues 5–22) and TM3 (residues 37–61), and a loop (residues 23–36) connecting TM2 and TM3. Figures 2B–2D show the J+RDC splitting of representative residues of uniformly 15N-labeled TM23 in bicelles with q values ranged from 0.19 to 0.50. As shown in Fig. 2B and 2D, the extent of the J+RDC splitting of residues in the two transmembrane domains increases in a linear fashion as the q ratio increases. The quantity of J+RDC splitting of the residues in the loop between TM2 and TM3, however, shows little dependence on the bicelle q values, as illustrated in Fig. 2C. The different dependencies of the transmembrane domains and the loop region to the size and shape of bicelles is a reflection of their location in bicelles. The increased J+RDC splitting at greater q value results from the contribution of RDC alone because the J-coupling is orientation independent. Strong dependence of the J+RDC splitting for the residues in the transmembrane segments of TM23 suggests that both TM2 and TM3 are embedded in bicelles, while the loop of TM23 are highly mobile and may possibly lie outside the bicelles where the RDC is more subjected to motional averaging (Figure 2C). Similarly, the different sensitivity of the TM2 residues to q values in the isolated TM2 segment and in the TM23 segment indicates that unlike an isolated TM2, the TM2 in TM23 is embedded in bicelles. In general, the size of bicelles becomes larger and their shape becomes more discoid when the q ratio increases. The morphology and the bilayer organization of low-q bicelles have been carefully studied experimentally11. In particular, bicelles with q = 0.5 were found to have the disk shape, with the disk diameter being approximately twice as large as the thickness of the bicelles. Moreover, the flat region of the disk is mostly occupied by the DMPC molecules. The sterically restricted local order of long-chain molecules such as DPMC, whose volume magnetic susceptibility anisotropy is ~0.145 JT−2m−3,26 will sum up to sizeable magnetic susceptibility anisotropy. Since the free energy of magnetic alignment is proportional to bicelle volume and the square of the magnetic field strength, it can be estimated that bicelles with q = 2 (R ~ 137 Å, r ~ 20 Å, V ~ 2.93 × 106 Å3) and q = 0.5 (R ~ 41 Å, r ~ 20 Å, V ~ 0.41 × 106 Å3) will have similar free energy of orientation and hence similar degree of residual alignment in field strengths of 5.3 T and 14.1 T, respectively (i.e., Vq=2B1 2 = Vq=0.5B2 2). The insertion of transmembrane proteins into low-q bicelles may significantly change the shape of the bicelles and add anisotropic components to the bicelles in addition to the possible reduction in the rotational diffusion rate of the bicelles, effectively increasing the q value and making the residual alignment even more profound (see Supporting Information for theoretical considerations). Therefore, the enhanced anisotropy by the insertion of transmembrane proteins made the weak alignment of small bicelles possible and made such bicelles excellent medium for the RDC measurements of the embedded proteins using solution-state NMR. It is clear from Fig. 2B–2D that q = 0.50 is a suitable choice for obtaining reliable RDC values while maintaining reasonable NMR sensitivity and resolution.

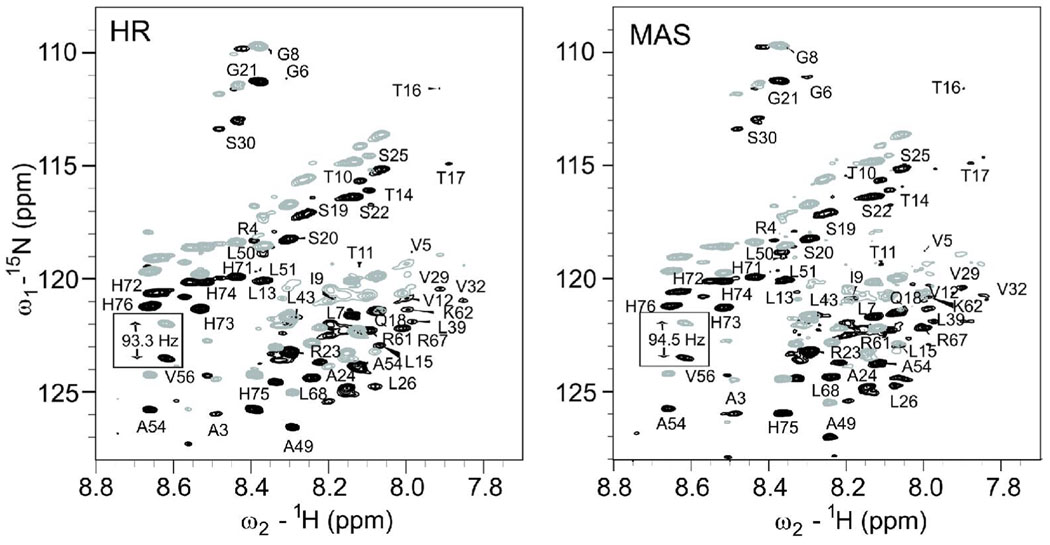

The RDC values of TM23 were determined in two ways. First, the bicelles with q = 0.19 was considered having only isotropic motion, and the frequency splitting of individual residues in IPAP experiments was believed to be purely contributed by the J-coupling only. The RDC values can thus be measured from the differences in the IPAP splitting for the same residues in the spectra with bicelles of q = 0.50 (J+RDC) and q = 0.19 (J). The disadvantage of using this method is that a few peaks changed their chemical shifts or even disappeared altogether when the lipid compositions were changed, suggesting a possible protein conformational change and therefore making the RDC measurement questionable. In the second method, RDC values were obtained from the spectra acquired on the same sample (q = 0.50) but with and without spinning at the magic angle. High resolution magic angle spinning (hr-MAS) NMR spectroscopy of TM23 in bicelles averaged out the angular terms to zero in Eq. 1, resulting in only JNH splittings in an IPAP spectrum. Fig. 3 depicts a superposition of representative up-field (peaks in grey) and down-field (peaks in black) IPAP spectra from TM23 in q = 0.50 bicelles acquired with the conventional high-resolution NMR and with hr-MAS. Both spectra show comparable quality, and the 15N-1H RDC values can be easily calculated by subtracting the splitting in hr-MAS spectrum from that in the conventional high-resolution spectrum. A clear advantage of using hr-MAS NMR is that the same sample can be used for measurements at both isotropic and weakly aligned conditions. The ambiguity that might arise from changes in the composition of lipids can be removed. A possible disadvantage of using hr-MAS NMR to obtain J values is the relatively low detection sensitivity compared to the conventional high-resolution NMR as there is currently no MAS cryo-probe available. The sample volume in MAS probes is also significantly smaller (~1/6) than in the conventional probes. The sensitivity disadvantage may become more apparent with 3D NMR experiments. For example, only a few 13Cα-1Hα and 13Cα-13C’ RDC values in the helix region could be accurately measured in the 3D HNCO-based IPAP experiments. Nevertheless, this disadvantage does not affect the usefulness of the method for the conventional RDC measurements. A good quality hr-MAS spectrum, as shown in Fig. 3B, is indeed achievable through more scans or using more concentrated samples. Taken together, the combination of hr-MAS and conventional high resolution NMR offers a unique and attractive approach to RDC measurements of transmembrane proteins in bicelles.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the 15N-1H IPAP spectra obtained from (A) conventional high-resolution NMR and (B) hr-MAS NMR of human glycine receptor TM23 in bicelles at q = 0.50. The gray and black peaks are the up-field and down-field IPAP peaks, respectively. The peaks for V56 are highlighted as an example to illustrate the differences in the IPAP splitting with and without MAS. The RDC values are readily measurable from these differences.

Data Fitting and Structural Refinement

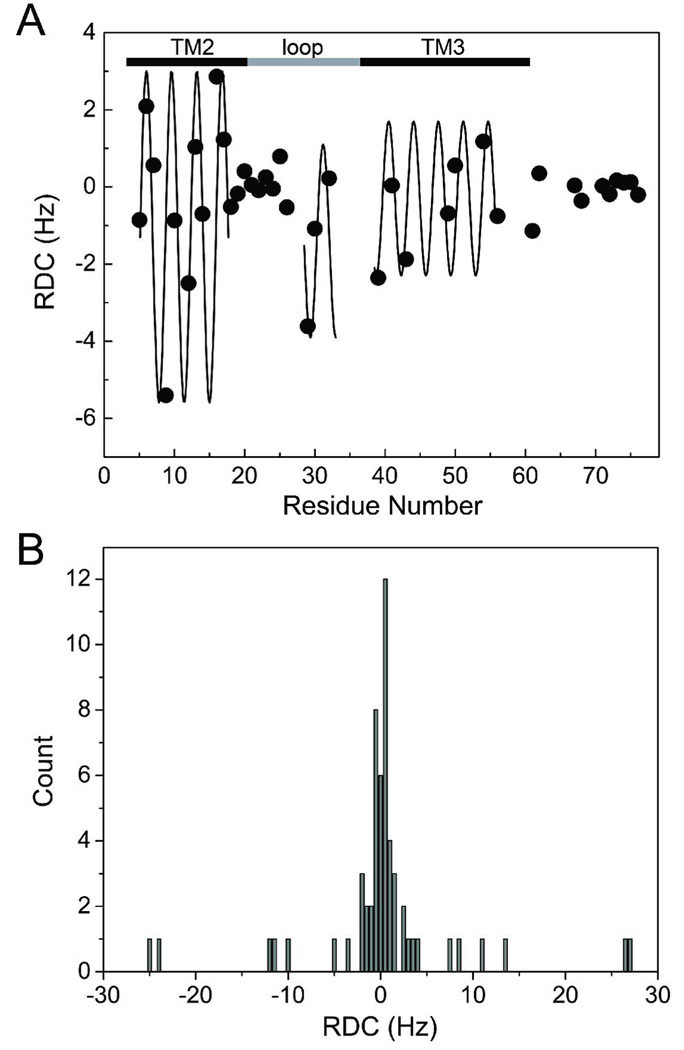

Fig. 4A summarizes the 15N-1H RDC values calculated for TM23 in bicelles of q = 0.50 using the hr-MAS method. A pattern comprised of non-zero RDC in the TM2 and TM3 regions and near-zero RDC in part of the loop region is recognizable along the sequence of TM23. The TM2 region shows a sinusoidal RDC pattern from V5 to T17. Between Q18 and L26, the RDC values become smaller, indicating that this segment of the protein, consisting of carboxyl end of the TM2 and the amino end of the loop region, is non-helical and flexible. There is apparently a helical structure in part of the loop from V29 to roughly I35. Most of the TM3 region is characterized by α-helical secondary structure from W38 to V56. The RDC amplitude varies from −5.4 to 2.9 Hz, −3.6 to 0.3 Hz, and −2.4 to 1.2 Hz in TM2, the end of the TM2-TM3 loop, and TM3, respectively. The different RDC values between transmembrane and loop regions coincide with the different physical locations of the segments in the bicelles. Moreover, the RDC values for residues in TM2 and TM3 as well as a few residues near the end of the loop can be fit reasonably well with sine functions having a periodicity of 3.6 residues per turn as shown by the solid lines in Figure 4A27,28, suggesting that these regions are of the α-helical structure. The α-helical content of TM23 is also confirmed by the Cα and Hα chemical shift index analysis (data not shown), which indicates α-helical structures between V5-L15 in the TM2 region, S30-K33 in the loop region, and L44-R61 in the TM3 region. The different amplitudes of the RDC wave in various regions are due to the difference in the angular terms in Eq. 1. To evaluate if the measured RDCs are self-consistent structurally, a theoretical fitting of the TM23 RDC wave pattern was performed to predict the helical protein fold using the equations of Mascioni and Veglia29. First, the initial values of the alignment tensor magnitude, Da, and rhombicity, R, were estimated using the histogram of both the 15N-1H and the normalized 13Cα-1Hα and 13Cα-13C’ RDC values (see Figure 4B). Since the number of RDC values from the TM23 is limited, the histogram method is not very accurate and can only serve as an initial estimate. We also used the maximum likelihood method30 to determine Da and R, yielding Da = 14.0 ± 1.8 Hz and R = 0.62 ± 0.01. As discussed below, these estimates are in agreement with the results determined by the Xplor-NIH refinement protocol, in which Da and R are determined along with the structure refinement. The maximum and minimum RDC amplitudes and periodicity of the experimental 15N-1H RDC data in both the TM2 and TM3 regions of TM23 were then analyzed with helical sinusoids using the estimated Da and R values by iteratively fitting the angles Θ, Φ, and ρ, where the angles Θ and Φ are the spherical coordinates of an ideal α-helix axis with respect to the principal axis system (PAS), and ρ is the angle between the x-axis and the projection of the NH bond vector on the x-y plane. ρ is thus also the rotation angle that sets the periodicity of the RDCs with respect to residue number. The resulting iterated angular parameters are summarized in Table 1. Plotting the corresponding helix axis vectors from the values given in Table 1 predicts the tertiary structure of TM2 relative to TM3. The theoretical fitting yielded a tilting angle of 35 ± 5° between TM2 (V5 to T17) and TM3 (L39 to V56) helix axis. This value is slightly smaller than that observed in the TM23 structures determined in TFE12. Some uncertainties are likely to be introduced due to deviations from the theoretical assumptions, such as the imperfect helices in the actual structures and the possible underestimation of the maximum RDC amplitude in the TM3 region where a significant number of the residues are not assigned. Despite this, the agreement between all the measured RDC values obtained using the low-q bicelles and the back-calculated RDCs from the lowest energy structure of TM23 in TFE is reasonable, as shown in Figure 5A with a linear correlation coefficient of r = 0.66. The imperfect linearity in Figure 5A can be accounted for by the difference in the media used in the two structure studies. Nevertheless, the data suggest that the structure of TM23 in TFE does not differ greatly from the structure in bicelles. This demonstrates that structural features of the TM23 are preserved reasonably well in various lipid-mimicking environments as revealed by the spectral characteristics of the TM23 in TFE and in dodecylphosphocholine micelles (unpublished data).

Figure 4.

(A) The experimental 15N-1H RDC values, measured for the TM23 segment of the human glycine receptor in the weakly aligned bicelles, exhibit sinusoidal patterns as a function of the residue number. Three α-helical segments, corresponding TM2, TM3, and a short helix near the carboxyl end of the loop, can be clearly identified. (B) The histogram of the 15N-1H, 13Cα-13C’ and 13Cα-1Hα RDC values, yielding estimated principal components of the alignment tensor: Axx = −0.86, Ayy = −27.14, Azz = 28.0. The magnitude of the axial component of the molecular alignment tensor and the rhombicity can be estimated to be Da = 14.0 Hz and R = 0.62.

Table 1.

Orientations of TM2 and TM3 Helix Axes Relative to PAS*

| Region | Θ(°) | Φ(°) | ρ(°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TM2: Residue Numbers 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 | 96.8 ± 1.0 | 169 ± 1.0 | 280 ± 10 |

| Loop and TM3: Residue Numbers 29, 30, 32, 39, 41, 43, 49, 50, 54, 56 | 90.0 ± 1.0 | 0.0 ± 1.0 | 110 ± 10 |

Obtained from fitting the experimental 15N-1H RDC values with the Mascioni-Veglia equations29, using Da = 14.0 Hz and R = 0.62.

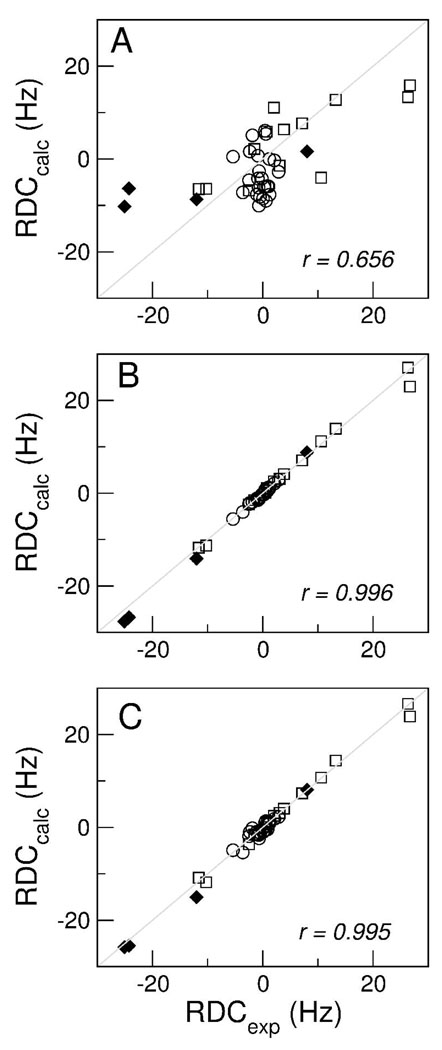

Figure 5.

(A) Correlation between the experimental RDC values from the helical regions of the human glycine receptor in bicelles and the back-calculated RDC values from the lowest energy structure of TM23 in TFE. Reasonable fitting (r = 0.66) suggests that the tertiary fold of the helices in the two media is similar. Using the TM23 structure in TFE as a template, structural refinement with the RDC constraints in bicelles yielded greatly improved correlations between the experimental and back-calculated RDC values for (B) the lowest-energy structure (r = 0.996) and (C) the averaged structure of 20 refined structures (r = 0.995). Symbols ○, □ and ◆ represent RDC values determined from the 15N-1H (24 RDCs), 13Cα-1Hα (14 RDCs) and 13Cα-13C’ (4 RDCs) vectors, respectively. Non-15N-1H RDCs are scaled relative to 15N-1H RDCs.

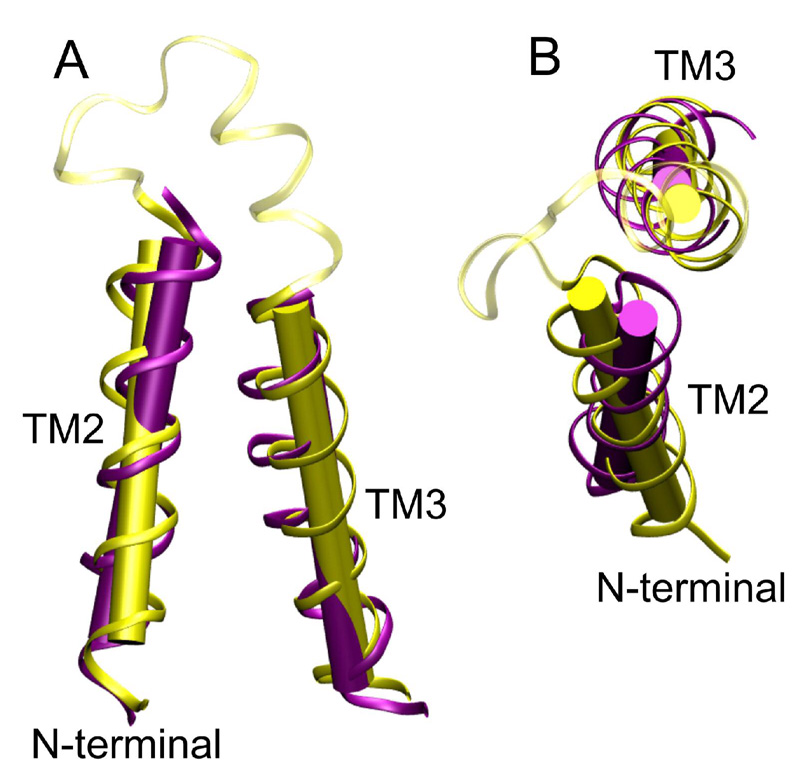

Using TM23 structure in TFE as a template, the RDC constraints can be used to “refine” the TM23 structure in the bicelles. Ideally, NOE-based structure of TM23 in bicelles with q = 0.2 would serve as a better template for RDC structural refinement. This is potentially feasible because a better sensitivity can be expected from proteins in bicelles of q = 0.2 than in bicelles of q = 0.5. For TM23, however, long-range distance constraints between different TM domains were still difficult to obtain even at q = 0.2. When the TM23 structure in TFE is used, the method is technically not the classical structural refinement calculation due to different media used in generating the angular and distance constraints. Nevertheless, the reasonable correlation coefficient shown in Figure 5A assures some degree of similarity between the two structures. Within defined variances of the distance constraints of the TFE structure, we imposed the experimental RDC constraints in bicelles to allow the overall tertiary structures to vary. After the refinement, the lowest-energy structure has greatly improved correlation coefficient between the experimental and back-calculated RDC values (Figure 5B), with r = 0.996. The average structure from 20 refined structures (out of 100) also gives an excellent correlation coefficient (r = 0.995). The output values of Da and R are similar to the values obtained using the histogram method, yielding Da = 20.6 Hz, R = 0.614 and Da = 18.5 Hz, R = 0.548 for the lowest energy structure and the average of the 20 best structures, respectively. Figure 6 shows the superposition of the averaged TM23 structure refined in bicelles and the structural template from the TM23 structure in TFE. The refinement brought about changes in the orientation of TM2 and TM3 helix axes relative to the initial structure template as a result of the imposed RDC restraints in the bicelle medium. The helical tilt angle between TM2 (V5 to T17) and TM3 (L39 to V56) of the average structure in bicelles (Figure 6) is measured to be 29.5 ± 2°, slightly smaller than that observed in TFE (43.4 ± 2°) and the predicted value based on the theoretical fitting (35 ± 5°). The relative tilting angle between the short helix at the carboxyl end of the TM2-TM3 loop (residues V29-I35) and TM2 and TM3 are about 18° and 162°, respectively, and the axes of the three helices are not in the same plane. It is important to point out that the introduction of distance restraints and additional RDC data from 13Cα −1Hα and 13Cα-13C’ couplings (to help fix the peptide plane orientation) in the structure refinement helped to alleviate the fourfold degeneracy in helix orientation. Due to unavailability of long-range distance restraints from TM23 in bicelles, the suggested structure shown in Figure 6 may not reflect the only possible structure of TM23 in bicelles. Translational aberrations and symmetric orientations distinct from that shown in Fig. 6, but indistinguishable from RDC data, are possible. However, the possibility of having distinctly different yet symmetrically equivalent orientations, such as with TM2 pointing outside the bicelle membrane, is very unlikely due to unfavorable energy required in changing the TM23 fold in TFE upon incorporation into bicelles.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the lowest energy structures of TM23 in TFE (yellow) and in bicelles (purple): (A) the side view and (B) the top view. The backbone RMSD between the two structures is 2.9 Ǻ. The helix tilt angle between TM2 and TM3 helix axis reduced from 43.4 ± 2° in TFE to 29.5 ± 2° in bicelles. The loop region between TM2 and TM3 from the TFE structure is shown in transparent yellow. The corresponding loop region from the refined structure in bicelles is not shown.

In summary, bicelles with relatively low q ratios (q = 0.5) have been shown to exhibit weak magnetic alignment for transmembrane domains of membrane proteins, such as TM3 and TM23 of the human glycine receptor, allowing for accurate measurements of the residual dipolar coupling and hence the tertiary structural refinement on the basis of the derived RDC constraints. We also showed that the combination of the low-q bicelle alignment with hr-MAS offers a unique and straightforward way to obtain structurally meaningful RDC information without potential complications due to medium environment changes as often found in other methods. Analysis of the TM23 structure in the membrane-like bicelles revealed that the second and third transmembrane domains of the human glycine receptor along with the important loop between them are composed of three α-helical regions from V5 to T17 (TM2 helix), from V29 to I35 (loop helix), and from L39 to V56 (TM3 helix). The method is readily expandable to other TM domains of the glycine receptor and other receptor proteins and, with selective isotope labeling strategies, can provide useful structural information of membrane proteins that is otherwise difficult to obtain.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information includes a discussion of the properties of low-q bicelles using an ideal bicelle model, the NMR chemical shift assignments for TM23 in q = 0.5 bicelles, a comparison between NMR chemical shifts of TM23 in bicelles and in TFE, and a table of the measured RDC values used in this study. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ms. Ling Li for expressing and purifying the proteins used in this study. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R37GM049202, R01GM056257, and R01GM069766).

References

- 1.Saupe A, Englert G. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1963;11:462–464. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen MR, Mueller L, Pardi A. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clore GM, Starich MR, Gronenborn AM. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10571–10572. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishii Y, Markus MA, Tycko R. J Biomol NMR. 2001;21:141–151. doi: 10.1023/a:1012417721455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prosser RS, Hwang JS, Vold RR. Biophys J. 1998;74:2405–2418. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77949-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders CR, 2nd, Prestegard JH. Biophys J. 1990;58:447–460. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82390-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tjandra N, Bax A. Science. 1997;278:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Opella SJ, Marassi FM. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3587–3606. doi: 10.1021/cr0304121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders CR, Hare BJ, Howard KP, Prestegard JH. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 1994;26:421–444. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Opella SJ. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;227:307–320. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-387-9:307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glover KJ, Whiles JA, Wu G, Yu N, Deems R, Struppe JO, Stark RE, Komives EA, Vold RR. Biophys J. 2001;81:2163–2171. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)75864-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma D, Liu Z, Li L, Tang P, Xu Y. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8790–8800. doi: 10.1021/bi050256n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. San Francisco: University of California; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson BA, R. A. B. J. Biomolecular NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordier F, Dingley AJ, Grzesiek S. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:175–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1008301415843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Permi P, Rosevear PR, Annila A. J Biomol NMR. 2000;17:43–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1008372624615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang D, Tolman JR, Goto NK, Kay LE. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;12:325–332. doi: 10.1023/A:1008223017233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Clore GM. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2006;48:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. J Magn Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipsitz RS, Tjandra N. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:387–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.140306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clore GM, Schwieters CD. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:2923–2938. doi: 10.1021/ja0386804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Bax A. J Magn Reson. 1998;133:216–221. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zweckstetter M, Bax A. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3791–3792. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho G, Fung BM, Reddy VB. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1537–1538. doi: 10.1021/ja005605+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scholz F, Boroske E, Helfrich W. Biophys J. 1984;45:589–592. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84196-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipsitz RS, Tjandra N. J Magn Reson. 2003;164:171–176. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesleh MF, Lee S, Veglia G, Thiriot DS, Marassi FM, Opella SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8928–8935. doi: 10.1021/ja034211q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mascioni A, Veglia G. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12520–12526. doi: 10.1021/ja0354824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren JJ, Moore PB. J Magn Reson. 2001;149:271–275. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information includes a discussion of the properties of low-q bicelles using an ideal bicelle model, the NMR chemical shift assignments for TM23 in q = 0.5 bicelles, a comparison between NMR chemical shifts of TM23 in bicelles and in TFE, and a table of the measured RDC values used in this study. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.