Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To describe ethics consultations at a single institution that has a mandatory ethics consultation policy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all adult patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit at Columbia University Medical Center and had an ethics consultation between August 1, 2006, and July 31, 2007. All mandatory and nonmandatory ethics consultations were reviewed. Patient diagnosis, prognosis, presence of do-not-resuscitate order, presence of written advance directives, reason for the ethics consultation, and survival data were collected. The number of ethics consultations hospital-wide from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2007, was collected.

RESULTS: The total number of mandatory and nonmandatory ethics consultations requested was 168. Of these consultations, 108 (64%) were considered mandatory, and 60 (36%) were considered nonmandatory. Between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2007, the total number of ethics consultations increased 84%.

CONCLUSION: The increase in the total number of ethics consultations is interpreted as a positive outcome of the mandatory policy. The mandatory ethics consultation policy has possibly increased exposure to ethics consultant-physician interactions, increased learning for physicians, and raised awareness among physicians and nurses of potential ethics assistance.

This study found an increase of 84% in the total number of ethics consultations, which was interpreted as a positive outcome of the mandatory policy. The mandatory ethics consultation policy has possibly increased exposure to ethics consultant-physician interactions, increased learning for physicians, and raised awareness among physicians and nurses of potential ethics assistance.

CUMC = Columbia University Medical Center; DNR = do-not-resuscitate; ICU = intensive care unit

Ethical problems regarding application of medical care are common in the intensive care unit (ICU).1,2 Typically, these problems relate to the ethically appropriate use of sophisticated and costly technology in the treatment of severely ill patients.1,2 Patients are admitted to ICUs to receive medical treatments that are increasingly sophisticated as technology continues to advance.1-3 Such interventions are warranted only if the patient has a reasonable chance of improving as a result of these interventions.3 The provision of intensive care can be experienced as uncomfortable and undignified by both the patient and the patient's loved ones. Of importance, the patient and the patient's family must have a realistic understanding of the patient's prognosis, nature of available interventions, and likely outcome of these interventions. As Danis et al2 wrote, “physicians working in the ICU setting face the difficulty of performing two simultaneous tasks. Their first task is to provide life-sustaining therapy, as desired, with the goal of preserving life and restoring health after critical illness or injury. On a parallel track, they face the task of helping patients and their families or other intimates cope with the possibility of death.” Among the many ethical issues involved in the ICU, the most frequent discussions are about how aggressively medical care should be applied in end-of-life situations.

Many patients are admitted to the ICU with reasonable chances for survival, but their condition deteriorates to the point at which improvement or even survival is unexpected. The decision to withhold or withdraw treatment involves difficult ethical and emotional issues for the families of these patients and for the physicians and nurses in the ICU.2-4

End-of-life issues in ICUs include requests from families that represent 2 extremes and everything in between. The family can request that the physician “do everything” despite the fact that aggressive treatment will only prolong the dying process of a patient whose hope for survival is virtually zero. Or the request, which is less common, is a premature request to withhold or withdraw treatment despite the fact that physician consensus is that the patient may well survive and have a good quality of life.

Often, ICU physicians and nurses have received inadequate training to discuss end-of-life issues. As Carlet et al5 report in the article on the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care, “although it is now generally accepted that optimal care for dying patients and their families is a crucial aspect of intensive care practice, the training received by critical care clinicians is frequently inadequate.” Furthermore, often ICU physicians and nurses have no time to discuss sensitive end-of-life issues with families or patients.2,3,5 As Gavrin3 explains, “in the ideal world, these should not need mention, but medicine does not function in such a place; the acuity in the ICUs, the time pressures, and the general hustle and bustle often seem to get in the way….This could not be more true than when discussing end-of-life issues.” To fill this gap, many hospitals provide palliative care teams or ethics consultants. Carlet et al5 report that “to date, the role of ethics committees and consultants in the daily activities of ICUs has in general been limited to exceptional cases and their overall impact on the day-to-day end-of-life decision-making in the ICU has been limited.” However, at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC), each case involving withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining treatments necessitates an ethics consultation or a referral to patient services.

When CUMC and New York Hospital were merged in 1998, a single-hospital policy was mandated in cases of removal of life support. Because of New York State case law, life support cannot be removed from a patient who lacks decisional capacity unless one of the following exists: written advance directives, a legal health care proxy, or prior verbal “clear and convincing” evidence given by the patient requesting such an action.6 To ensure compliance with New York State law, after the merger of the 2 institutions, policy of the newly created New York Presbyterian Hospital required either a medical ethics consultation or a referral to patient services for all requests for removal of life support. To our knowledge, this is the first published report of a mandatory ethics consultation policy at a hospital.

The Medical Ethics Committee at CUMC currently consists of 21 members: physicians representing medical specialties, as well as representatives from nursing, social work, patient services, the legal department, the Center for Bioethics, pastoral care, and a representative from the community. The committee meets monthly to discuss ethics case consultations, to develop hospital policies related to issues of clinical ethics, and to initiate and implement educational programs for the hospital and university community at large.

An ethics consultation can be requested by the patient, the patient's family, or anyone involved in the care of the patient. All adult ethics consultation requests are referred either directly to the physician who is the director of clinical ethics or to an ethics committee member covering in his or her absence. After receiving the consult information, the ethics consultant may resolve straightforward issues by discussing with the referring physician, or, in more complex cases, seeing the patient and holding family meetings with all those involved in the care of the patient. In such cases, the consultant will write a note in the patient's medical chart. In the more straightforward cases, the physician will document in the patient's chart that an ethics consultation was requested. By having the physician write his or her own note in the chart, the mandatory ethics consultation policy achieves the goal of teaching the physician how to document ethical issues in an appropriate form in the chart.

The single consultant method has advantages, including the accumulation of experience and expertise by the consultant and flexibility in meeting with patients and families. The disadvantage is the possibility of bias. To try and minimize the disadvantages of the single consultant format, the consultant will contact members of the committee via telephone or e-mail when their expertise is needed. Infrequently, the consultant has emergency meetings with the entire ethics committee for their consideration and suggestions. Once a month, the consultant reviews with the committee members consultations that occurred during the previous month for discussion and critique.

The main aim of this retrospective study was to document the experience of mandatory and nonmandatory ethics consultations at CUMC. We limited our review of ethics consultation requests to ICUs. The director of clinical ethics has maintained a record of all adult ethics consultations at CUMC since 2000. We reviewed the medical charts of all adult patients who were admitted to the ICU at CUMC and had an ethics consultation between August 1, 2006, and July 31, 2007. All mandatory and nonmandatory ethics consultations were reviewed. We collected the number of ethics consultations hospital-wide from 2000 to 2007.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After the Columbia University Internal Review Board waived the need for informed consent, patients older than 18 years who had been admitted to an ICU and had an ethics consultation between August 1, 2006, and July 31, 2007, were entered in the study. If a consultation was repeated for a patient, this consultation was not recorded as another consultation unless it involved an ethical issue that had not been recorded in the previous consultation. In our sample, each consultation represents a patient.

The following data were obtained from admission progress, ethics, and discharge notes: date of ethics consultation; patient age, sex, and ethnicity; ICU admission; ethics note if written in the patient's chart; patient's diagnosis; patient's prognosis as recorded in the chart; presence of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order; presence of written advance directives; patient's survival; and type of ethical issue(s) presented. If the patient survived to discharge, survival information was obtained by searching the patient in the US Social Security Death Index. If a patient was diagnosed as having more than 1 disease, all diseases were recorded in the database. If the ethics consultation involved more than 1 issue, all issues were recorded in the database. The number of admissions to and discharges from the ICUs between August 1, 2006, and July 31, 2007, was collected.

The classification of the ethical issues was adapted from a previous study,7 and the type of ethical issue was defined as follows. (1) Withholding or withdrawing treatment was defined as a request by either the family or the physician to remove the patient from life support or to provide palliative care. (2) Appropriateness of treatment, goals of care, or futility was defined as any conflict or dilemma concerning the type of treatment the patient was receiving. (3) Resuscitation issues were defined as any conflict or question regarding DNR decisions. (4) Legal-ethics interface was defined as any question in which the legality, ethics, or interpretation of the law needed to be explained or researched by the ethics consultant. (5) Competency or decisional capacity was defined as any conflict or dilemma regarding the patient's ability to make informed medical decisions. (6) Psychiatric issues were defined as any psychiatric issue, such as depression, that could affect the patient's capacity to make medical decisions. (7) Family conflict was defined as family members in disagreement with one another regarding the patient's treatment. (8) Staff or professional conflict was defined as the staff being in disagreement. (9) Discharge disposition was defined as an ethics issue that arose concerning the patient's disposition after discharge. (10) Allocation of resources was defined as any case in which physicians thought that resources were not allocated in an ethically appropriate way. (11) Spiritual or cultural issues were defined as when religious or other cultural considerations resulted in conflicts concerning the treatment of the patient. (12) Confidentiality was defined as a question arising regarding the patient's confidentiality (eg, whether to disclose information to a health care proxy who needs to know to make an informed decision, which the patient wanted kept confidential). (13) Advance directives were defined as a question being asked that concerned the interpretation of advance directives. (14) Reproductive issues were defined as any ethical issue that dealt with reproduction. (15) Other was defined as any other ethical issue that could not be classified in the aforementioned categories.

Descriptive data were analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, 4968 patients were admitted to the adult ICUs at CUMC. Of these patients, 168 (3%) received an ethics consultation. The mean ±SD age of these 168 patients was 65±16 years (range, 24-96 years). Of the 168 patients, 80 (48%) were men, and 61 (36%) were white.

Of the 168 consultations, 108 (64%) were mandatory, and 60 (36%) were nonmandatory. Of note, some of the 108 consultations that involved request for removal of life support might have been sought without a mandatory ethics consultation policy in place.

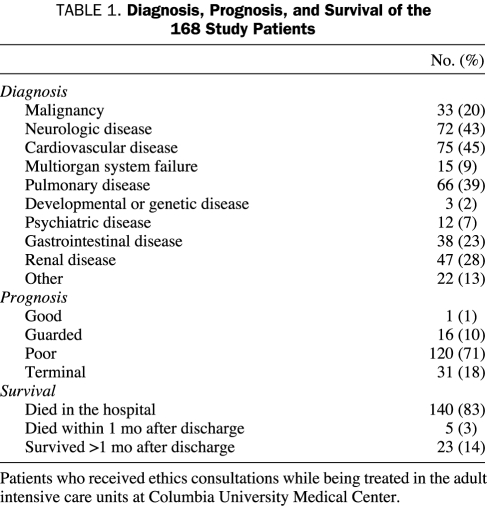

Overall, 63 consultations (38%) were in the medical ICU, 41 (24%) in the neurologic ICU, 25 (15%) in the cardiothoracic ICU, 22 (13%) in the coronary ICU, and 17 (10%) in the surgical ICU. The most common diagnosis was cardiovascular disease in 75 patients (45%), followed by neurologic disease in 72 (43%), pulmonary disease in 66 (39%), renal disease in 47 (28%), gastrointestinal disease in 38 (23%), malignancy in 33 (20%), multiorgan system failure in 15 (9%), psychiatric disease in 12 (7%), developmental or genetic disease in 3 (2%), and miscellaneous in 22 patients (13%). The prognoses were “poor” and “terminal” for 120 (71%) and 31 (18%) of the patients, respectively; the remaining were “guarded” for 16 (10%) and “good” for 1 (1%) of the patients.

Of the 168 patients, 140 (83%) died in the hospital, 5 (3%) died within a month after discharge, and 23 (14%) survived more than 1 month after discharge (Table 1). Additionally, 52 patients (31%) had an ethics consultation note in their charts, and 125 (74%) had a DNR order in their charts; 64 (38%) had written advance directives or a health care proxy.

TABLE 1.

Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Survival of the 168 Study Patients

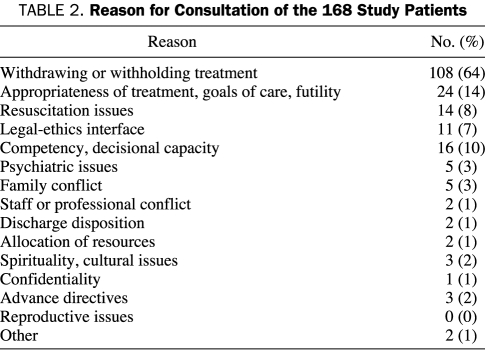

Withholding or withdrawing treatment was the most common reason that an ethics consultation was requested and represented 108 patients (64% of the sample). After withholding or withdrawing of treatment, the most common reasons for ethics consultations were futility for 24 patients (14%) and decisional capacity for 14 (8%) (Table 2). Similar results have been noted in other studies of ethics consultations.8-15

TABLE 2.

Reason for Consultation of the 168 Study Patients

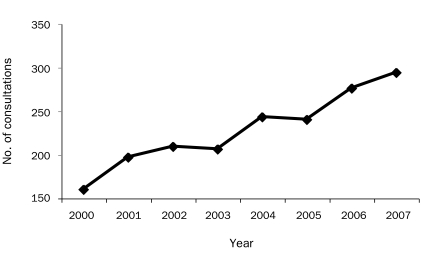

The total number of ethics consultations requested between 2000 and 2007 at CUMC was 1825. From 2000 to 2007, the total number of ethics consultations, including mandatory and nonmandatory ethics consultations requests, increased 84% (Figure).

FIGURE.

Adult ethics consultations at Columbia University Medical Center.

DISCUSSION

In other reviews of ethics consultations,16 the usefulness of such consultations varied. Reasons offered as to why physicians would refrain from asking for ethics consultations ranged from thoughts of being displaced, to the perceived uselessness of the consults, to the fear of increasing the likelihood of generating legal problems. Although we did not conduct interviews with physicians or nurses to determine the satisfaction of the ethics consultations, the number of hospital-wide consults at CUMC has almost doubled during the past 7 years and far exceeds the median number (n=15) of ethics consultations in a survey of more than 500 general hospitals.17 Reasons for the success at our institution might be that the physician conducting the consultations is the Director of Clinical Ethics, with more than 35 years of clinical experience in pulmonology, general internal medicine, and critical care. Members of the ethics committee can be consulted freely by e-mail or telephone when necessary, and fourth-year medical students perform monthly rotations with the consultant. Thus, every ethics consultation is an opportunity not only to address common ethical questions but also to educate house staff, fellows, nurses, attending physicians, and social workers.2

Data suggest that physicians have biases regarding the withdrawing of life-sustaining therapy.5,18 By mandating ethics consultations for consideration of withholding or withdrawing removal of life support, our institution minimizes any potential bias of physicians or nurses toward ethics consultations. Thus, this policy provides a standard of care for all patients and families during end-of-life discussions. Of note, 64 (38%) of our patients had written advance directives, either a written living will and/or a designated health care proxy. Of the 108 patients with treatment limitation or removal of life support, 43 (40%) had written advance directives, compared with national figures of 5% to 25% of adults with advance directives.7

The mean age of our patients, 65 years, is somewhat older than that reported in previous series.1-5,7,8 La Puma et al9 and Schneiderman et al19 reported mean ages of 68 and 67.5 years, respectively. The distribution of the diagnoses of our patients is typical for a large referral medical center, with cardiovascular, neurologic, pulmonary, and malignant diseases heading the list of diagnostic categories. Persistent sepsis was seen repeatedly in many of our ethics consultation cases. Patients were grouped on the basis of their diagnosis on admission to the ICU. Thus, if a patient with lung cancer was admitted to the ICU and developed sepsis, he or she would be listed in the series as “malignancy” rather than “sepsis.” As in a large Mayo Clinic series,7 infectious disease as the primary diagnosis was conspicuously small. As indicated by our series, most of the population in ICUs that requires ethics consultations consists of older adults with diseases associated with aging, such as cardiovascular disease.

Given the fact that the overwhelming number of consults in our series was requested because of end-of-life decisions, it is not surprising that 83% of patients with an ethics consultation died in the hospital. High mortality rates, up to 82%, have also been reported in other series1,3-5,7,10,20 of patients receiving ethics consultations. In a single-site, prospective, randomized controlled trial in which patients were randomized to either undergo an intervention (ethics consultation offered) or receive standard care, Schneiderman et al21 found no significant difference in mortality between those who had an ethics consultation and those who did not. These results were confirmed by Schneiderman et al19 in a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled intervention study.

No reason exists to think that requesting an ethics consultation per se will affect patients' mortality. Rather, it seems that in our series, the ICU team appropriately identified patients whose treatment might be prolonging the dying process. In such a situation, an ethics consultation will assist the patient, family members, and the medical team by identifying and explaining nonbeneficial treatment and unethical prolonging of death.

Of the deaths in our study, 140 (77%) occurred after the removal of life support or withholding of treatment. The timing and manner of an ICU patient's death have increasingly become an event that can be controlled by the family and the physician.4,5 Given the ever-increasing sophistication of ICU technology, it is not surprising that ethical issues weigh so heavily in this setting.

CONCLUSION

Limiting treatment of critically ill patients, including removal of life support, is the most common reason for ethics consultations in ICUs at CUMC, and the majority of consultations involve end-of-life discussions. As such, guidance from physicians and ethics consultants is critically important to the emotional well-being of families who struggle with these decisions. The hectic pace of an ICU with its chronic shortage of time for communicating with families; frequent turnover of attending physicians, fellows and residents; and the inexperience of many of the young physicians in dealing with end-of-life issues all contribute to the need for ethics consultants who have the time and experience to help physicians deal with ethically complex issues and distraught families.

As medical technology becomes ever more sophisticated and physicians become ever more specialized, the need for medical ethics consultations in the ICU will almost certainly continue to increase. Our ethics consultation service has seen an increase in requests. This increase in ethics consultant-physician interaction is interpreted as a positive outcome of the mandatory policy at CUMC. The mandatory ethics consultation policy has possibly increased exposure to ethics consultant-physician interactions, increased learning for physicians, and raised awareness among physicians and nurses of potential ethics assistance. More research in this area is needed.

Footnotes

Funding for this research was provided by the Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University, New York, NY.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duff RS. Guidelines for deciding care of critically ill or dying patients. Pediatrics 1979;64(1):17-23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danis M, Feuerman D, Fins JJ, et al. Incorporating palliative care into critical care education: principles, challenges, and opportunities. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(9):2005-2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavrin JR. Ethical considerations at the end of life in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2 suppl):S85-S94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubenfeld GD, Randall Curtis J, End-of-Life Care in the ICU Working Group End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a research agenda. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):2001-2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(5):770-784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/legislation/WestchesterCountyMed%20Center.pdf. In the Matter of Westchester County Medical Center on Behalf of Mary O'Connor, Appellant. Helen A. Hall et al., Respondents. 72 N.Y.2d517, 531 N.E.2 507, 534 N.Y.S.2d 886 (N. Y. 1988;[Oct]:14). Accessed April 23, 2009.

- 7.Swetz KM, Crowley ME, Hook C, Mueller PS. Report of 255 clinical ethics consultations and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(6):686-691 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Puma J. Consultations in clinical ethics-issues and questions in 27 cases. West J Med. 1987;146(5):633-637 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.La Puma J, Stocking CB, Silverstein MD, DiMartini A, Siegler M. An ethics consultation service in a teaching hospital: utilization and evaluation. JAMA 1988;260(6):808-811 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andereck WS. Development of a hospital ethics committee: lessons from five years of case consultations. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 1992Winter;1(1):41-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orr RD, Moon E. Effectiveness of an ethics consultation service. J Fam Pract. 1993;36(1):49-53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenkenberg T. Salt Lake City VA Medical Center's first 150 ethics committee case consultations: what we have learned (so far). HEC Forum 1997;9(2):147-158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waisel DB, Vanscoy SE, Tice LH, Bulger KL, Schmelz JO, Perucca PJ. Activities of an ethics consultation service in a tertiary military medical center. Mil Med. 2000;165(7):528-532 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forde R, Vandvik IH. Clinical ethics, information, and communication: review of 31 cases from a clinical ethics committee. J Med Ethics 2005;31(2):73-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.La Puma J, Stocking CB, Darling CM, Siegler M. Community hospital ethics consultation: evaluation and comparison with a university hospital service. Am J Med. 1992;92(4):346-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuVal G, Clarridge B, Gensler G, Danis M. A national survey of U.S. internists' experiences with ethical dilemmas and ethics consultation. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):251-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox E, Myers S, Pearlman RA. Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: a national survey. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(2):13-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christakis NA, Asch DA. Biases in how physicians choose to withdraw life-support. Lancet 1993;342(8872):642-646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel H, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290(9):1166-1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan TA. Ethics committees and decisions to limit care: the experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital. JAMA 1988;260(6):803-807 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD. Impact of ethics consultations in the intensive care setting: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3920-3924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]