Abstract

The aim of this study was to compare the characteristics of the first demyelinating event between acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and multiple sclerosis (MS). Children with acute demyelinating disease of the central nervous system and an abnormal brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) were studied. Patients were assigned a final diagnosis after long-term follow-up. Comparisons were made between the MS and ADEM groups. Proposed definitions by the Pediatric MS Study Group were applied to our cohort in retrospect and are discussed. Fifty-two children and adolescents with a documented abnormal brain MRI were identified (24 females, 28 males; mean age 10y 11mo [SD 5y 4mo] range 1y 10mo–19y 7mo). To date, 26 children have been diagnosed with MS, and 24 with ADEM. One child has relapsing neuromyelitis optica and one child has clinically isolated optic neuritis. Follow-up duration was 6 years 8 months in monophasic patients, and 5 years 6 months in relapsing patients. None of the patients with MS had encephalopathy while encephalopathy was present in 42% of patients with ADEM. Cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands, an elevated immunoglobulin G index, and the periventricular perpendicular ovoid lesions correlated with MS outcome. Several clinical characteristics differ between ADEM and MS at first presentation; encephalopathy, when present, strongly suggests the diagnosis of ADEM.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by immune-mediated myelin loss with variable degrees of axonal injury. It is characterized by recurrent attacks of neurological dysfunction. Acute disseminated encephalitis (ADEM) is typically known as a monophasic inflammatory demyelinating disorder of the CNS usually following a viral infection. Complete recovery from ADEM is reported at 57 to 89%.1,2

The relationship between MS and ADEM is complicated and difficulties still exist in distinguishing them at the initial clinical episode, especially in young children. Making an accurate distinction is important as immunomodulating agents can reduce exacerbations, MRI activity and, to some extent, the progression of disability in MS. In the absence of biochemical markers, clinical and paraclinical data have been used to try to distinguish between the two diseases at onset. Long-term clinical follow-up of individual patients remains the best way to determine diagnosis. At this time, accumulated clinical experience has resulted in better recognition of pediatric onset MS and related conditions and recently, consensus definitions have been proposed by the Pediatric MS Study Group.3

In this study, diagnosis after a period of follow-up was used to define the most accurate final outcome. Review of the presenting clinical, spinal fluid, and radiological characteristics was performed to define better the initial diagnostic impression of MS versus ADEM.

Method

CASE IDENTIFICATION AND DATA COLLECTION

Patients with acute demyelinating disorders were identified by retrospective chart review from 1990 to the present of patients seen and followed at our tertiary referral center. Some of these patients are prospectively being followed by investigators. Ninety-eight patients were identified who had experienced acute clinical demyelinating events. Clinical features, brain and spine MRIs, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings at initial presentation and during the follow-up were reviewed and recorded.

Follow-up clinical information was obtained either from medical records or by telephone interviews by the principal investigator. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and written consent/assent was obtained from parents and patients.

CLINICAL OUTCOME, INCLUSION CRITERIA, AND STUDY DEFINITIONS

Detailed information was obtained on every patient and the diagnosis assigned after follow-up was recorded (Fig. 1). The main distinction of outcome was made between relapsing and non-relapsing patients. Relapse was defined as developing new symptoms or new MRI lesions at a different CNS site beyond 4 weeks from onset (modified from McDonald criteria4). Repeated episodes with identical symptoms to the initial presentation without new lesions on MRI were not considered a true relapse. Many of the patients who remained clinically normal did not have long-term serial MRIs after initial periods of their illness. All patients with a relapsing course had multiple MRIs obtained which documented new lesions.

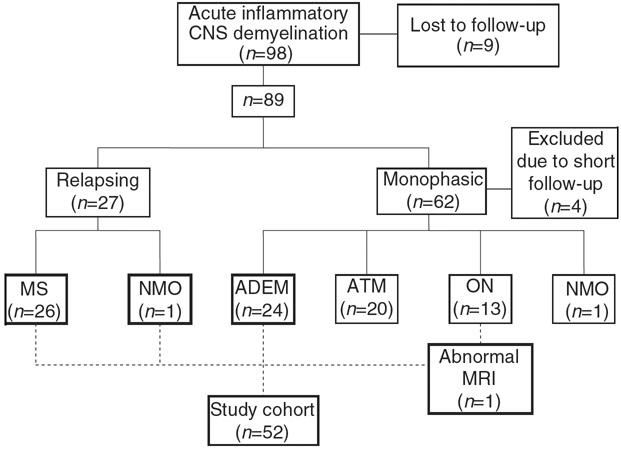

Figure 1.

Diagnostic classification of patients with acute inflammatory demyelinating disorders of central nervous system (CNS) after long-term follow-up. Study population is shown in bold boxes. MS, multiple sclerosis; NMO, neuromyelitis optica; ADEM, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (with and without encephalopathy); ATM, clinically isolated acute transverse myelitis; ON, clinically isolated optic neuritis.

This study focused on the cohort derived from the 98 patients with demyelination, which included children with an abnormal brain MRI at first presentation, or later relapses. Patients with isolated optic neuritis, isolated transverse myelitis, and neuromyelitis optica (NMO; polysymptomatic presentation localized only to spinal cord and optic nerve) who had no relapse, had normal brain MRIs at presentation, or no MRI performed at presentation and never had documented abnormal MRI later during the follow-up, were excluded. Further analysis is underway of the isolated optic neuritis and myelitis cohorts who were excluded from this report.

The diagnosis of ADEM required a polysymptomatic presentation associated with one or more brain lesions and no relapse beyond 3 months from the initial presentation. The presence of encephalopathy was assessed retrospectively instead of being a requisite criterion for ADEM.3 MS was diagnosed by McDonald criteria.4 Current definitions of ADEM and pediatric MS criteria were applied in retrospect to this cohort and are discussed.3

CHARACTERISTICS ANALYZED FOR MS OUTCOME

After determining the final diagnoses, comparison of initial characteristics was made between patients with ADEM and MS. Variables included age, sex, race, family history of MS, presenting symptoms, preceding infection or immunization; CSF oligoclonal bands, immunoglobulin G (IgG) index, leukocyte count, protein, and location of MRI lesions and presence of periventicular perpendicular ovoid lesion (PVPOL).

MRIs were performed using a 1.5T magnet with T1 and T2 in all the patients. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences (FLAIR) were available in most studies. Gadolinium enhanced studies and spine MRIs were not available in all patients. Brain MRIs were reviewed by two neurologists (GA, RH) independently but not blinded to clinical information. Available spine MRIs were reviewed but not included in the analysis. PVPOLs are described as elongated or oval appearance, ‘flame shape’ lesions; present at the ventricular edge and perpendicular to the ventricular edge.5,6

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS (version 15.0). Comparisons between ADEM and MS were performed using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests for continuous variables, χ2, or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. If there was any 0 frequency in the cell, a small sample correction by adding 0.5 to each cell was used.

Results

Of the initial 98 patients with acute demyelinating events, nine were lost to follow-up. The flow chart (Fig. 1) demonstrates the diagnostic assignment of 89 children after follow-up. Four of the non-relapsing patients with less than 1 year follow-up were excluded from the study. Fifty-two children met the inclusion criteria for this study (mean duration of follow-up 6y 1mo [SD 3y 8mo]; range 6mo–17y 3mo).

DIAGNOSES AFTER LONG-TERM FOLLOW-UP

Relapsing group

Among the 89 children, 26 were diagnosed with MS (30%) and one patient was diagnosed with relapsing NMO (1%). Mean duration of follow-up in relapsing patients was 5y 6 mo (range 6 mo–17y 3mo, SD 4y 1mo). The patient with NMO had a positive NMO–IgG antibody and met all the criteria for NMO.7 The mean latency to develop an MS defining episode was 9mo (range 2–15mo, SD 4mo). None of the relapsing patients had encephalopathy in any attacks. There were four patients with symptoms attributable to partial myelitis at presentation. Brain MRIs showed typical MS-like lesions, met Barkhof criteria8 at first episode (n=3), or later (n=1), and spinal MRIs showed less than three segments involvement in all of them. These four have been followed by adult neurology MS specialists and remain with a diagnosis of MS(Fig. 1).

Monophasic group

In the study group, 25 children experienced a monophasic course which consisted of patients with no relapse beyond 3 months. Mean follow-up duration was 6y 8mo (range 2y 5mo–13y 1mo, SD 3y 2mo). There was no child with less than 2 years follow-up; 24 had polysymptomatic presentation and were assigned the diagnosis of ADEM (24/89, 27%). Among them there was one patient who experienced a relapse at a different CNS site, which was within 10 weeks of onset and occurred 4 weeks after steroid discontinuation and exposure to another infection. He did not have encephalopathy in any attack. He has had no further relapse and is neurologically intact 11 years after onset. As he did not have relapses beyond 3 months he is assigned the diagnosis of ADEM. One patient had recurrence of the symptoms analogous to those present at the initial event at both 5 months and 1 year after onset. Repeated studies showed residual gliosis from the initial event but did not demonstrate any new lesions. He has had no further events for 12 years. He is assigned the diagnosis of ADEM as none of the events represent a true relapse. One patient in the monophasic group presented with only optic neuritis, an abnormal brain MRI, and remains relapse-free for 2 years and 5 months. She is assigned a diagnosis of clinically-isolated optic neuritis.

The diagnoses are also shown on the flow chart (Fig. 1) for the remaining monophasic patients of demyelinating cohort who were not included and analyzed in this study. This is important as the diagnoses may shift from one to another during the longitudinal follow-up due to overlap features of demyelinating diseases. Mean follow-up was 7 years (range 2y 4mo–14y 8mo, SD 3y 11mo) in the isolated optic neuritis group, and 7 years (range 2y–12y 7mo, SD 3y 7mo) in the isolated myelitis group. One patient with monophasic NMO has been followed for 4 years and 6 months.

COMPARING CHARACTERISTICS OF FIRST PRESENTATION BETWEEN ADEM AND MS

Several clinical and laboratory features differed significantly between patients with MS and those with ADEM. The mean age was 14y 10mo (range 3y 10mo–19y 7mo, SD 3y 3mo) in MS, and 7y (range 1y 10mo–16y 4mo, SD 4y) in patients with ADEM. Age at onset was significantly older in patients with MS (p<0.001). Male/female ratios, race and history of preceding infection, or immunization were not different between the two groups (p=0.98, p=1.0, and p=0.07 respectively). Family history of MS was present in six of 26 patients with MS and no patient had MS history in the ADEM group (p=0.023, OR=15.5, 95% CI 0.8–292.6).

Encephalopathy, fever, and seizure differed significantly between ADEM and MS. Encephalopathy was found in 10/24 patients with ADEM whereas no patient had encephalopathy in the MS group (p=0.001, OR=0.03, 95% CI 0.001–0.5). Five children had fever and six had seizures in the ADEM group whereas no MS patient presented with fever or seizure (p=0.02, OR=0.07, 95% CI 0.004–1.3; p=0.008, OR=0.05 0.003–1.0 respectively). The other presenting clinical features including headache, tremor/dysmetria, ataxia, weakness (mono/hemi/para/quadriparesis), paresthesia, cranial nerve findings, diplopia, unilateral vision loss, and bilateral vision loss were not found to be significantly different between the two groups. Paresthesia was the most frequent symptom in patients with MS (9/26) while weakness was most frequently noted in patients with ADEM (12/24). The mean age of patients with and without encephalopathy (p=0.93), seizure (p=0.31), and fever (p=0.68) did not differ statistically within the ADEM group.

CSF findings

CSF white cell count and protein values did not differ significantly between ADEM and MS. In the ADEM group there were two patients with tumor-like massive demyelinating lesions who had extremely high protein and white cell counts. Complete CSF studies were not available in all patients. Oligoclonal bands studies were positive in eight of 18 patients with MS whereas no ADEM (n=13) patient had oligoclonal bands (p=0.01, OR=21.9, 95% CI 1.1–423.5). The IgG index was more frequently elevated (≥0.70) in patients with MS (3/13 ADEM vs 15/18 MS, p=0.001, OR=16.7, 95% CI 2.8–99.7). An elevated IgG index was seen in three patients with ADEM, one of whom had evolution of disease for 10 weeks and two patients with massive demyelinating lesions.

Initial MRI patterns

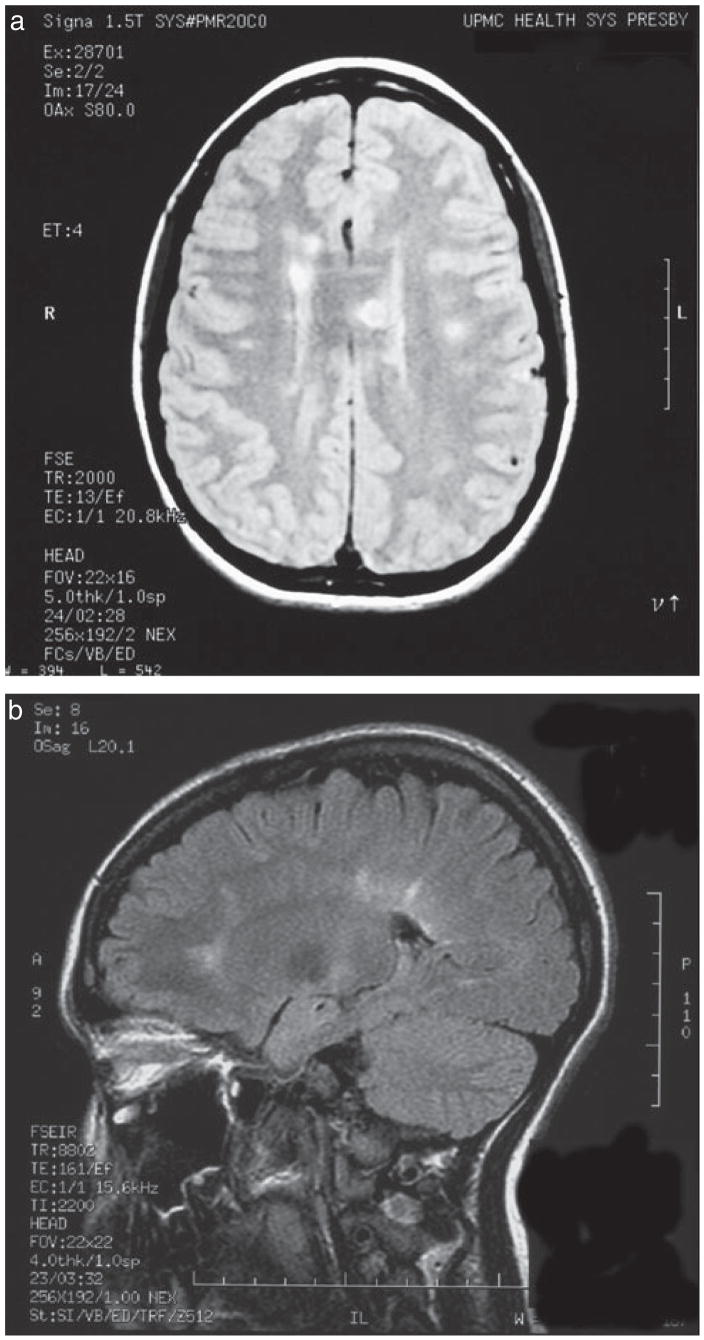

There were 50 children with abnormal brain MRI at first presentation. The patient with NMO and one of the patients with MS initially had normal brain MRIs and developed brain lesions later after clinical relapses. Periventricular white matter was the most common lesion location in the MS group (Table I) mostly characterized by PVPOLs. Hard copies of initial MRIs were not available to review in five patients with MS. Tumor-like massive demyelinating lesions causing mid-line shift were present in two patients with ADEM and they were not included in the location analysis. There were 15 patients with PVPOL and all subsequently were diagnosed with MS (Fig. 2). No patient in the ADEM group had PVPOL (p<0.001, OR=126.8, 95% CI 6.5–2463.4). In the MS group, five patients initially did not have PVPOLs and one patient presented with a normal MRI. No significant age difference was found between patients with MS with and without PVPOL (p=0.44).

Table I.

Distribution of lesions in t first brain MRI

| Location of lesion | ADEM (n=22) | MS (n=21) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Periventricular white mattera | 4 (18) | 17 (81) | <0.001 |

| Central white matter | 15 (68) | 11 (52) | 0.29 |

| Subcortical white matter | 11 (50) | 6 (29) | 0.15 |

| Juxtacortical white matter | 5 (21) | 1 (5) | 0.58 |

| Deep grey mattera | 9 (43) | 2 (10) | 0.03 |

| Brainstem | 9 (41) | 6 (29) | 0.40 |

| Corpus callosuma | 2 (9) | 9 (43) | 0.01 |

| Cerebellum | 11 (50) | 7 (33) | 0.27 |

Significant. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ADEM, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (with and without encephalopathy); MS, multiple sclerosis.

Figure 2.

Periventricular perpendicular ovoid lesions (PVP-OLs) are shown on (a) axial T2-weighted image and (b) sagittal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences (FLAIR) image at first presentation of multiple sclerosis (MS) in two patients.

PROPOSED DEFINITIONS OF PEDIATRIC MS STUDY GROUP3 AND OUR COHORT

Table II shows the applications of the study group definitions to the participants in our cohort after follow-up. Duration of follow-up was 7y 7mo (range 2y 7mo–13y 1mo, SD 3y 6mo) in the ADEM group (with encephalopathy) and 6y 1mo (range 2y 5mo–11y 11mo, SD 2y 11mo) in patients with clinically isolated syndrome without encephalopathy (p=0.37) and they all remained monophasic.

Table II.

Diagnoses in 52 children and adolescents after application of proposed definitions by Pediatric Consensus Group3

| Diagnosis by proposed definitions | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| ADEM polysymptomatic, encephalopathy present | 10 |

| CIS | 14 |

| No encephalopathy mono or multifocal | Polysymptomatic = 13 Monosymptomatic = 1 (ON with abnormal brain MRI) |

| Multiphasic ADEM encephalopathy required with each episode | 0 |

| Recurrent case(Recurrent ADEM)a (no true relapse, repeat with identical features) |

1a One patient had recurrence of the initial symptoms twice (at 5mo and 1y) but never had encephalopathy. Never developed new lesions on serial follow-up MRIs. No new attacks for 12y |

| MS | 26 |

| No encephalopathy, two or more discrete events separated in time and space | |

| NMO | 1 Multiple relapses of ON and myelitis, initial brain MRI is normal, transient involvement of hypothalamus and midbrain during the 3rd relapse, NMO–IgG antibody positive |

This patient had recurrent, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (with and without encephalopathy; ADEM) by authors’ opinion although he never had encephalopathy and, in that case, current criteria for recurrent ADEM cannot be completely met and his case remains unclassified by consensus definitions. CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; ON, clinically isolated optic neuritis; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMO, neuromyelitis optica.

In the study population, by using proposed definitions at first presentation, ADEM (with encephalopathy) was compared with clinically isolated syndrome (all cases without encephalopathy) for MS outcome, MS was diagnosed in 0/10 cases with initial encephalopathy and in 26/42 without encephalopathy. Children without encephalopathy had a significantly higher likelihood of a later MS diagnosis (p=0.001, OR=0.03, 95% CI 0.002–0.54).

Discussion

Differentiation of childhood MS from ADEM has important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Our results showed that MS is slightly more frequent than ADEM in the demyelinating cohort. While the ability to provide definitive early diagnosis may be limited, identification of high risk patients who may develop MS is crucial, and markers of such risk are needed. There have been many studies reporting the clinical and radiological features of ADEM in children.1,2,9–12 and there are few studies that directly compare the two diseases.1,9,13 The main distinguishing features were reviewed previously14,15 and consensus definitions for pediatric MS and related disorders were published which reflect the shared clinical experience and previous literature in this field.3

Our results showed that pediatric MS occurs at an older age than ADEM. In ADEM the age at onset was found to be similar to other series.1,2,10,11 Age at MS onset was found to be older than the French cohort16 which is most likely to be due to the small number of patients less than 10 years old in our cohort. Family history of MS was relatively frequent at 23% in patients subsequently developing MS. Family history of MS was reported as 21% by Duquette et al.17 and 8% in the French study.16 Family history of MS, also found to be a risk factor in the French study, should be considered as a risk factor for subsequent diagnosis of MS.18 Our results support that the presence of oligoclonal bands correlates with MS outcome.19

One of the Pediatric Study Group’s proposed criteria for ADEM is the presence of encephalopathy, as it is not typically associated with MS.3 Reports of encephalopathy in ADEM vary from 45 to 69%,1,10–12 and 58% of patients with ADEM did not have encephalopathy in this study. Therefore, the absence of encephalopathy does not rule out ADEM. While this criterion increases the specifity of the ADEM diagnostic label, absence of it does not preclude a clinical diagnosis of ADEM as patients otherwise typical for ADEM in our study behaved similarly on follow-up, whether or not they had encephalopathy. It is important to convey to the parents the likely favorable prognosis of ADEM.

In concordance with current definitions, encephalopathy was not found in patients with MS. We found that for a patient presenting with encephalopathy at the first demyelinating event, MS is less likely compared with a child without encephalopathy. The French study found an 18% second attack rate in patients diagnosed with ADEM initially which included cognitive changes by definition.18 While the presence or absence of encephalopathy would be a useful sign to suggest a patient’s risk for MS, it may not eliminate the possibility of an MS diagnosis in a subsequently relapsing patient.

We think that the 3-month cut-off time accepted by the pediatric consensus group is very useful as ADEM can evolve and show new or fluctuating symptoms shortly after presentation, which sometimes can be related to steroid withdrawal.3 This might be an arbitrary cut-off but fits our patient who had a relapse within 10 weeks of onset. This patient also met McDonald criteria, but long-term follow-up in this patient has not demonstrated any new clinical or MRI event.

One can argue that the diagnostic criteria of this study did not allow the diagnosis of multiphasic ADEM3 because all the relapsing cases, regardless of the presence of encephalopathy would be diagnosed as having MS. By pediatric consensus definitions, ADEM should be followed by new attacks involving new anatomical areas with polysymptomatic presentation, including encephalopathy, to meet the criteria for multiphasic ADEM.3 This difference in diagnostic criteria was not a factor in the current study because none of the patients with encephalopathy had relapses during the follow-up. Therefore, none of our cohort met the criteria for multiphasic ADEM (Table II). Multiphasic ADEM diagnosis still remains as the most controversial one, and distinguishing from MS can be very challenging in the absence of markers. NMO should also be considered in relapsing children with prominent myelitis and NMO–IgG antibody should be detected. We think that if multiphasic ADEM exists as a distinct phenotype, it represents a very small portion of patients with ADEM. For now, it is important to conceptualize that recurrent and multiphasic ADEM are thought of as restricted illnesses not associated with chronic relapsing demyelination.19

In this study we found that the presence of PVPOL on MRI strongly suggests the diagnosis of pediatric MS. Periventricular and pericallosal location and the characteristic ovoid features of the lesions perpendicular to ventricular edge (also called Dawson’s fingers) are recognized as one of the most significant features of MS in adult patients.5,6 Although PVP-OLs are not included in adult MS MRI criteria, it was analyzed in this study based on the authors’ hypothesis that they were not seen in patients with ADEM. No definite radiological criterion has been established for ADEM, even though there are some recognizable patterns reported.1,2,20,21 In children, absolute and relative sparing of the periventricular region in ADEM has been emphasized previously.1 Mikaeloff et al. reported that the second attack rate was higher in patients with well-defined ovoid lesions perpendicular to the corpus callosum long axis, introduced as KIDMUS criteria.22 Therefore, children with PVPOLs at first demyelinating events should be described as ‘clinically isolated syndrome suggestive of MS’ and followed as high-risk patients for the subsequent diagnosis of MS. We suggest that if PVPOLs are present, these children should not be diagnosed with ADEM – even in the presence of encephalopathy – and close clinical and MRI follow-up is recommended. Sagittal FLAIR MRI is particularly useful in imaging PVPOLs. MRI patterns are less defined in younger children (<10y) with MS22 and may not demonstrate PVPOLs. The limitation of this study is that only two children were younger than 10 years old in the MS group. Coordinated efforts to review clinical, CSF, and MRI features involving a greater number of early onset MS and ADEM cases will be needed to better determine the specificity of these variables, particularly PVPOLs.

The Pediatric Study Group acknowledges that criteria may not apply to all possible situations.3 Some illustrative cases and controversies have recently been discussed.23,24 In this study, diagnoses were not applied at the first presentation but assigned after years of follow-up in retrospect. Our cohort has one of the longest durations of follow-up, which enhances the diagnostic accuracy. As there is no biochemical marker available, the distinction between ADEM and MS was made by the presence of relapses during longitudinal follow-up. This definition cannot be applied at initial presentation but is necessary to define risk factors for this eventual outcome.

Conclusion

Distinguishing features of MS and ADEM can be recognized at initial presentation in the majority of the patients. Children presenting with a first demyelinating event should be analyzed carefully for known risk factors of MS, and if present, not be labeled with ADEM, but considered as having a clinically isolated syndrome. The first demyelinating event can be the first attack of MS, therefore, these children should be monitored closely for future relapses and early treatment may be considered for high-risk patients.

At this time it is crucial to use the standard definitions in research and publications to advance our understanding of pediatric demyelinating disease. Recent consensus definitions by the Pediatric MS Group will help to accomplish this goal by minimizing the risk of inconsistency in diagnosis and contamination of patient groups for clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under the Ruth L Kirschstein National Research Service Award NS07495 and in part by the NIH NINDS under grant K 12 NS052163. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

List of abbreviations

- ADEM

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- NMO

Neuromyelitis optica

- PVPOLs

Periventricular perpendicular ovoid lesions

Contributor Information

Gulay Alper, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Child Neurology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, PA, USA.

Rock Heyman, Department of Neurology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, PA, USA.

Li Wang, Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, PA, USA.

References

- 1.Dale RC, de Sousa C, Chong WK, Cox TC, Harding B, Neville BG. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis, and multiple sclerosis in children. Brain. 2000;123:2407–22. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenembaum S, Chamoles N, Fejerman N. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a long-term follow-up study of 84 pediatric patients. Neurology. 2002;59:1224–31. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.8.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krupp LB, Banwell B, Tenembaum S International pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Consensus definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related definitions. Neurology. 2007;68(16 Suppl 2):S7–S12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259422.44235.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, Goodkin D, Hartung HP, Lublin FD, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traboulsee AL, Li DK. The role of MRI in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Adv Neurol. 2006;98:125–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon JH. Update on multiple sclerosis. Radiol Clin N Am. 2006;44:79–100. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66:1485–89. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkhof F, Filippi M, Miller DH, et al. Comparison of MRI criteria at first presentation to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1997;120:2059–69. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.11.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikaeloff Y, Suissa S, Vallee L, et al. KIDMUS Study Group. First episode of acute CNS inflammatory demyelination in childhood: prognostic factors for multiple sclerosis and disability. J Pediatr. 2004;144:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anlar B, Basaran C, Kose G, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: outcome and prognosis. Neuropediatr. 2003;34:194–99. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynson JL, Kornberg AJ, Coleman LT, Shield L, Harvey AS, Kean MJ. Clinical and neuroradiologic features of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. Neurology. 2001;56:1308–12. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murthy SNK, Faden HS, Cohen ME, Bakshi R. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. Pediatr. 2002;110:e21. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brass SD, Caramanos Z, Santos C, Dilenge ME, Lapierre Y, Rosenblatt B. Multiple sclerosis vs acute disseminated encephalomyleitis in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rust RS. Multiple sclerosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and related conditions. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2000;7:66–90. doi: 10.1053/pb.2000.6693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dale RC, Branson JA. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis or multiple sclerosis: can the initial presentation help in establishing a correct diagnosis? Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:636–39. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.062935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Assi S, Suissa S Tardieu; on behalf of the KIDSEP Study Group. Prognostic factors for early severity in childhood multiple sclerosis cohort. Pediatr. 2006;118:1133–39. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duquette P, Murray TJ, Pleines J, Ebers GC, Sadovnick D, Weldon P, et al. Multiple sclerosis in childhood: clinical profile in 125 patients. J Pediatr. 1987;111:359–63. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Husson B, Suissa S, Tardieu Marc on behalf of the Neuropediatric KIDSEP Study Group of the French Neuropediatric Society. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis cohort study: prognostic factors for relapse. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banwell B, Ghezzi A, Bar-Or A, Mikaeloff Y, Tardieu M. Multiple sclerosis in children: clinical diagnosis, therapeutic strategies, and future directions. Lancet. 2007;6:887–902. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenembaum S, Chitnis T, Ness J, Hahn J. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurology. 2007;16(Suppl 2):S23–33. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259404.51352.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richer LP, Sinclair DB, Bhargava R. Neuroimaging features of acute disseminated encephalomyleitis in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikaeloff Y, Adamsbaum C, Husson B, et al. KIDMUS Study Group on Radiology. MRI prognostic factors for relapse after acute CNS inflammatory demyelination in childhood. Brain. 2004;127:1942–47. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale RC, Pillai SC. Early relapse risk after a first inflammatory demyelination episode: examining international consensus definitions. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:887–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young NP, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: Current understanding and controversies. Semin Neurol. 2008;28:84–94. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]