Abstract

The effects of tropomyosin on muscle mechanics and kinetics were examined in skeletal myofibrils using a novel method to remove tropomyosin (Tm) and troponin (Tn) and then replace these proteins with altered versions. Extraction employed a low ionic strength rigor solution, followed by sequential reconstitution at physiological ionic strength with Tm then Tn. SDS-PAGE analysis was consistent with full reconstitution, and fluorescence imaging after reconstitution using Oregon-green-labeled Tm indicated the expected localization. Myofibrils remained mechanically viable: maximum isometric forces of myofibrils after sTm/sTn reconstitution (control) were comparable (~84%) to the forces generated by non-reconstituted preparations, and the reconstitution minimally affected the rate of isometric activation (kact), calcium sensitivity (pCa50), and cooperativity (nH). Reconstitutions using various combinations of cardiac and skeletal Tm and Tn indicated that isoforms of both Tm and Tn influence calcium sensitivity of force development in opposite directions, but the isoforms do not otherwise alter cross-bridge kinetics. Myofibrils reconstituted with Δ23Tm, a deletion mutant lacking the second and third of Tm’s seven quasi-repeats, exhibited greatly depressed maximal force, moderately slower kact rates and reduced nH. Δ23Tm similarly decreased the cooperativity of calcium binding to the troponin regulatory sites of isolated thin filaments in solution. The mechanisms behind these effects of Δ23Tm also were investigated using Pi and ADP jumps. Pi and ADP kinetics were indistinguishable in Δ23Tm myofibrils compared to controls. The results suggest that the deleted region of tropomyosin is important for cooperative thin filament activation by calcium.

Keywords: Muscle mechanics, Regulation, Skeletal muscle, Mutation, Calcium sensitivity

Introduction

The regulation of muscle contraction is a consequence of the complex relationship between troponin (Tn), tropomyosin (Tm), actin, and bound myosin cross-bridges [12]. As the sarcomeric structure of all muscle is essentially the same, the criteria of regulation must vary to meet the demands on different muscle types. For example, the cardiac isoform of Tn is more calcium sensitive than its skeletal counterpart, and this is but one adaption that allows force production within the heart to be controlled primarily at the cellular level [12]. The composition of tropomyosin isoforms varies from cardiac to skeletal muscle and from fast to slow fiber types [30]. Structural work has shown that the ratio of α to β Tm isoforms influences the preferred position at which Tm binds actin, with implications for calcium sensitivity and cooperativity [20]. To date, however, most functional studies of tropomyosin have been limited to in vitro motility and ATPase assays. This includes work on single point mutations in Tm which are linked to various myopathies. Mutations can affect the calcium sensitivity of the muscle and consequently lead to improper force production resulting in hypertrophy of the heart [15]. Several mutants of Tm have been engineered which exclude central sections of the molecule to create shortened constructs [18, 19]. Work in this area has helped to understand the role of Tm length in controlling calcium sensitivity and myosin cycling.

Of importance to the understanding of regulatory protein function, particularly for tropomyosin, is an experimental platform from which the mechanical and kinetic differences in the proteins can be assessed and compared. Clearly, this requires the structural environment of a muscle. The use of skinned fibers in such studies presents two significant problems. First, substrate gradients will develop within the fiber, and second, it is difficult to achieve a complete exchange of the regulatory proteins with confidence. Transgenic animals will produce tissue expressing the regulatory proteins of interest, but with other drawbacks, such as uncertainty over changes in the muscle biochemistry of the organism in response to stresses of the mutant proteins. In contrast, myofibrils offer a reductionist approach that, unlike single fibers, have short diffusion distances (typically <2 µm), which minimizes unwanted chemical gradients. As a consequence, rapid changes in substrate concentrations can be achieved through solution switching: e.g., calcium activation and relaxation [3, 40] and increases or decreases in phosphate concentration [39]. The small diameter makes myofibrils a good candidate for protein exchange experiments because of the rapidity of protein removal and rebinding. She et al. [35] investigated the conditions that promote whole Tn exchange in skeletal myofibrils based on a protocol developed by Brenner et al. [1]. Piroddi et al. [31] used the same technique to replace fast skeletal troponin with cardiac troponin and then examined the effects on myofibril contraction. Reliable mechanical data were obtained which could be directly related to the effects of cardiac verses skeletal troponin in regulation. In these examples, however, the native tropomyosin of the myofibrils remained bound to the thin filaments.

Replacement of endogenous tropomyosin in skeletal myofibrils, while retaining normal sarcomere structure and contractile behavior, has heretofore not been reported. A method claiming to yield enzymatically functional myofibrils [2] produces myofibrils that are very fragile and, if successfully attached to force transducers and activated, developed negligible force (Scellini and Homsher, unpublished experiments). Development of a quantitative replacement technique would enable evaluation of the effects of tropomyosin sequence perturbation mutations on mechanical activity and gain insight into the thin filament regulatory mechanism. Below, we describe the replacement of native troponin and tropomyosin while retaining mechanical behavior near to control values. The technique takes advantage of a reduced binding of troponin and tropomyosin to actin at low ionic strengths, enabling the removal of endogenous Tm and Tn [45]. Equivalent exogenous Tm and Tn proteins are then sequentially replaced at physiological ionic strength while maintaining the primary myofibril structure.

In the present study, we use this new method, supplemented by solution experiments with purified proteins, to examine the function of the N-terminal half of tropomyosin, to which Tn does not bind directly, on Ca2+-dependent regulation. Mechanically viable myofibrils were reconstituted with shortened tropomyosin, with two of the seven quasi-repeats (repeats 2 and 3) deleted. We characterize this deletion mutant’s effects, as well as the effects of a cardiomyopathy-inducing mis-sense mutation in this region. We also use the reconstitution method to separate and to identify large but selective functional effects of troponin and tropomyosin tissue isoforms (cardiac vs. skeletal) on mechanical and kinetic cross-bridge behavior.

Experimental procedures

Preparation of myofibrils Muscle bundles were harvested from white New Zealand 2–3 kg female rabbits, killed by intravenous injection of 150 mg kg−1 of sodium pentobarbital. The animals were cared for and euthanized according to protocols approved by the Chancellor’ Animal Research Committee at UCLA. The rabbit carcass was then kept on ice while muscle bundles were taken from the psoas muscle and tied to wooden sticks [41]. In several instances, white muscles of the back and upper thigh were collected (after cooling on ice for 30 min) from which contractile proteins were isolated and purified (see below). The muscle bundles were first equilibrated in a 200-mM ionic strength rigor solution at 4℃ (100 mM imidazole pH 7.1, 8 mM MgCl2, 4 mM K2EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), ionic strength made up to 200 mM with K+ propionate) containing protease inhibitors (0.4 mM phenylmehylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 20 µM leupeptin, 20 µM E64, and 10 µM pepstatin A) before being brought into a rigor solution containing 50% glycerol (with protease inhibitors) by methods described elsewhere [4]. Muscle fiber bundles were stored in a 50% glycerol/rigor solution at −20℃ for up to 4 weeks. Myofibril suspension solutions were obtained by dissecting about 200 mg of the fiber bundles in rigor solution at 5℃, followed by homogenization using a tissue tearor: two 10-s homogenizations at 12,000 rpm (Model 398, Biospec Products, Inc., OK, USA) [4]. The myofibrils were washed by centrifugation (2,000×g, for 5 min at 4℃ in a 5417R Eppendorf table top centrifuge Eppendorf, NY, USA), and then resuspended in fresh rigor solution. The wash procedure was repeated twice. The myofibril suspension protein content was determined using the Lowry method [22] with a bovine serum albumin standard and was typically 5 mg ml−1. Low adhesion centrifuge tubes were used to minimize myofibril binding and protein loss (USA Scientific, FL, USA).

Myofibril reconstitution To extract endogenous regulatory proteins the myofibril preparation (ca. 5 mg ml−1) was suspended in a low ionic strength solution (2 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0) and incubated on ice for 2 h at 0–4℃ [45]. The myofibrils were then recovered by centrifugation (as above), and the supernatant, which contained the soluble regulatory proteins, was retained for SDS-PAGE analysis. Myofibrils were washed in an intermediate 200 mM ionic strength rigor solution (2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0, ionic strength made up to 200 mM with NaCl, and protease inhibitors). The use of NaCl rather than K+ propionate was to permit SDS polyacrylamide gels to be run without the need to dialyze away potassium ions. The unregulated myofibrils were then reconstituted with exogenous Tm and Tn in two stages. First, the sample was recovered and resuspended in 200 mM ionic strength rigor solution containing 5 µM Tm and incubated on ice for 1 h. The Tm was either rabbit skeletal (sTm), sTm labeled with Oregon green (gsTm), bovine ventricular cardiac (cTm), cTm with the mis-sense mutation A63V (A63VTm), or cTm with quasi-repeats 2 and 3 deleted (Δ23Tm). Second, the myofibrils were recovered by centrifugation and resuspended in 200 mM ionic strength rigor solution containing 2 µM Tn, and incubated on ice for 1 h. The Tn was either rabbit skeletal (sTn) or bovine ventricular cardiac (cTn). The myofibrils were then washed and stored in 200 mM ionic strength rigor solution and used within 4 days. Substantial protein loss occurred at each step of the protocol, producing a final myofibril preparation with protein content of less than 1 mg ml−1. At each stage of the protocol, samples were retained for SDS-PAGE analysis.

Mechanical measurements The technique used to record force from myofibril contractions is as described in Colomo et al. [3]. Briefly, the ends of a myofibril, or small bundle of 2–3 myofibrils, were held between two glass microneedles, to which the myofibril adhered strongly. Each needle’s position was controlled by stepper motors using two XYZ axis joysticks controlling two robotic micromanipulators capable of programmed movements of ±40 nm–12.5 mm displacements (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA 94949 USA). The tip of one needle, the “pusher,” was also controlled by a piezoelectric multilayered actuator (AE0505D16F, Thorlabs, Newton, NJ, 07860, USA) powered by a single axis piezo controller (MDT694A, Thorlabs, Newton, NJ, USA). The pusher tip could be displaced up to 17 μm in ~1 ms. The tip of the second needle, the “detector” needle, was bent perpendicular to the needle’s long axis to form a lever to which one end of the myofibril was attached. The lever was painted black (oil-based ink pen, PIN-01A, Mitsubishi, Japan), and in use, it projected a shadow onto a split photodiode which monitored the lever displacement (<5 µm) during myofibrillar contraction. The lever was calibrated (microneedle compliance ranged from 4 to 12 μm μN−1) so that its deflection allowed the force and rate of contraction to be measured. Myofibrils, selected for the quality of their sarcomeres (as viewed under the microscope), ranged in length from 50 to 70 µm at a sarcomere length of 2.55–2.65 µm, and in diameter from 1 to 3 µm. The myofibril, held in a temperature-controlled (10℃) chamber filled with relaxing solution, was continuously immersed in one of two streams of solution produced by a double-barreled, theta-style perfusion pipette. The perfusion pipette was mounted on a stepper motor (Warner Instruments Corp., SF-77B perfusion fast-step, CT, USA), and myofibril activation was initiated by switching the flow solution from low (pCa 9) to high (up to pCa 4.5) calcium concentration. The total time from the start of the pipette movement to the solution change was ~35 ms. There was also a 40-ms delay between the input voltage of the controller and the start of the pipette movement. One barrel of the perfusion pipette was always connected to relaxing (pCa 9) solution while the other was fed by a manifold which could be electronically switched between two solution reservoirs (of varying pCa values). Solution switching between these reservoirs was accomplished within 10 s, while the solution reservoir was switched the myofibril was perfused with relaxing solution from the other barrel. This allowed the same myofibril to be activated at saturating and then subsaturating calcium concentrations. The amount of force developed at intermediate pCa levels was used to construct force-pCa curves to establish the calcium sensitivity of the myofibrils. Myofibrils could be maximally activated between two and six times before maximum tension dropped below 90% of the initial value. Data from contractions less than 90% of initial force were not used.

For phosphate and ADP jump experiments, both barrels of the perfusion pipette contained activating solution. For a phosphate jump, one barrel was fed with activating solution containing 1 mM added phosphate, and the other had 3 mM added phosphate. For an ADP jump, one barrel was fed with activating solution containing no added ADP, the other had 3 mM added ADP. As the system was limited to two flow solutions, the myofibril started in the relaxing solution of the bathing chamber. The perfusion pipette was manually moved into position to activate the myofibril. The base tension was recorded while the myofibril was relaxed, accounting for any effect on tension produced by the force of flowing solution, which was minimal (less than 3% P0). Concentration jumps were made by switching between the two streams using the stepper motor. This method of activation prevents kact rates from being obtained. Instead, ktr rates were measured by imposing release-stretch length steps of 10% of the myofibril length. The steps were completed in ~1 ms, and the time from the beginning of the release to the beginning of the stretch was 10 ms.

Protein isolation and purification For this work, rabbit fast skeletal Tm was extracted from rabbit fast skeletal muscle acetone powder using methods described in Smillie [36], and rabbit fast skeletal Tn was extracted using methods described in Potter [32], omitting the Cibacron Blue column purification step [14, 16]. The presence of the extracted proteins was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. The bovine ventricular cardiac Tm and Tn were extracted and purified as described by Tobacman and Adelstein [42]. The A63V mutant Tm was produced by methods described in Heller et al. [15]. The ala-ser Tm and Δ23Tm were produced by methods described in Landis et al. [18]. The regulatory proteins were stored at −80℃ in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5 containing 1 mM DTT, 5 mg L−1l-1-tosylamide 2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone, 5 mg L−1N-α-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone, and 0.3 mM PMSF. For some experiments, cTn was labeled with IAANS on TnC Cys84, as in Gong et al. [11].

Solutions For mechanical experiments, the relaxing solution (pCa 9) contained: 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.1, 5 mM Mg-ATP, 1 mM free Mg2+, 10 mM K2EGTA, 10 mM DTT with K+ propionate to adjust the ionic strength to 200 mM. The activating solution (pCa 4.5) was the same as relaxing solution except CaEGTA replaced K2EGTA. Intermediate pCa solutions (pCa > 4.5, and pCa < 9) were made by altering the ratio of K2EGTA/CaEGTA. Additionally, as a precaution, and despite the myofibril’s small diameter, the perfusion pipette solutions contained a phosphate “mop” (1 U ml−1 bacterial purine nucleoside phosphorylase, 0.5 mM 7-methylguanosine) and ATP backup system (10 mM creatine phosphate, 200 U ml−1 creatine kinase) to minimize any ADP and Pi gradients [40]. For Pi and ADP jump experiments activating solutions with added phosphate or ADP did not contain the phosphate “mop” or ATP backup system. All solutions contained the following protease inhibitors: 0.2 mM PMSF, 10 µM leupeptin, 10 µM E64, and 5 µM pepstatin A. Solution ionic composition, ionic strength, and pCa values were computed using a solution program written by E. Homsher and N. Millar (1990) based on the equations of Fabiato and Fabiato [8]. The Solution Program uses an equilibrium constant for Ca+2 binding to EGTA−4 of 1010.97 [34] as opposed the value of 1010.47 measured by Godt [10] to account for the effects of >20 mM imidazole in the solution [28]. The pCa values reported here can be converted to equivalent pCa values computed using the Godt [10] equilibrium constant by adding 0.5 pCa units to the given value.

Fluorescence labeling of proteins and fluorescent microscopy Rabbit skeletal Tm, extracted from acetone powder as described above, was dialyzed extensively first against 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM DTT to reduce the DTT level to 0.1 mM and then for 8 h against the same solution containing 4 M guanidine HCl to dissociate the tropomyosin homo- and heterodimers [13]. A 20-mM solution of Oregon green maleimide (Invitrogen, CA, USA) dissolved in dimethylformamide was added to the dialyzed solution containing 54 μM tropomyosin with stirring to bring the Oregon green maleimide concentration to 2 mM and initiate the labeling of cysteine residues in the tropomyosin. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 h in the dark at room temperature (22℃), at the end of which the labeling of tropomyosin was halted by the addition of DTT to a final concentration of 10 mM. The reaction solution (ca. 800 µl) was dialyzed against 500 ml of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.35), 1 mM NaN3, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethaol for 36 h with four solution changes to remove all but the Oregon green bound to the tropomyosin. Scans of the protein and dialysis solution at 280, 320, and 491 nm revealed that a solution of 28 μM Tm containing 3 mol of labeled cysteines per mole of tropomyosin had been obtained. The gsTm (ex. 488 nm, em. 512–530 nm) was reconstituted into myofibrils, followed by reconstitution with cTn, and finally treated with 400 nM tetramethylrhodamine-phalloidin (RPh) to label the thin filaments (ex. 540 nm, em. 560–600 nm). These labeled myofibrils (gsREC) were washed with rigor solution to remove background RPh fluorescence prior to fluorescence images being taken. Epifluoresence images were taken while myofibrils were in rigor and in the presence of a photobleaching protection system (0.1 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase, 2 mg ml−1 glucose). Images were taken at a magnification of ×60 (Plan Apo oil immersion objective, NA 1.35, Olympus, PA), using an EMCCD camera (iXon-DV897, Andor, CT, USA) with a resolution of 14 pixels µm−1.

Fluorescence studies of calcium binding to thin filaments in solution employed a bovine cardiac troponin complex reconstituted from purified TnI, TnT, and C34S TnC labeled on Cys84 with IAANS [13]. Aliquots of CaCl2 were added serially to samples containing 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.1), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM ATP, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA 1 mM DTT, 1.4 µM rabbit fast skeletal muscle F-actin, 1.4 µM phalloidin, and either 0.8 µM Δ23Tm + 0.28 µM IAANS-Tn, or 0.5 µM control full-length Tm +0.2 µM IAANS-Tn. A Fluoromax 3 spectrofluorometer excited the samples at 325 nm and recorded the signal at 450 nm.

SDS-PAGE Proteins present at different stages of the reconstitution protocol were analyzed using 12% SDS-PAGE. Gels (12% Tris-HCl ready gel, BioRad, CA, USA) were stained with Coomassie blue and then scanned using a PC scanner (Onetouch 7,600, Visioneer, CA, USA). Samples of myofibrils, and their proteins, retained during the reconstitution were recovered by centrifugation and resuspended in 100 µl of sample buffer. The supernatant retained following extraction of soluble proteins in low ionic strength was dehydrated in a spin vacuum and then resuspended in 100 µl of sample buffer. The gel image was analyzed using UN-SCAN-IT gel 6.0 software (Silk Scientific, Inc., UT, USA). To quantify the extent of the reconstitution, the intensity profile of each lane was taken and the ratio of α-Tm to myosin and actin in each lane determined.

Results

To evaluate the effectiveness of the tropomyosin and troponin reconstitution method, SDS-PAGE was used to monitor the extent of Tm and Tn removal and replacement, and the location of reconstituted tropomyosin within the sarcomere was assessed by fluorescence measurements of labeled proteins. Mechanical measurements of myofibrillar isometric force, kact, and calcium sensitivity were also used to evaluate the retention of mechanical behavior following the reconstitution, as well as to establish the effectiveness of the technique.

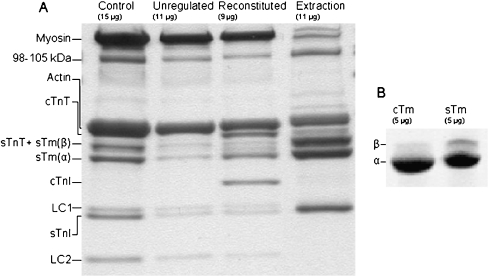

SDS-PAGE analysis of tropomyosin removal and replacement during myofibril reconstitution protocol During myofibril reconstitutions using cTn and sTm (mixREC), samples were retained at each stage of the protocol. The samples were run on a 12% gel to determine the relative presence of regulatory proteins. Figure 1a shows a gel from a mixREC preparation; the amount of protein present in each sample is approximate and different for each lane (a consequence of protein loss during the protocol). In each lane, the bands were quantified by their intensity. The degree of Tm replacement in each lane was assessed from the ratio of α-Tm band intensity to actin and myosin band intensities. Only α-Tm is used in these measurements because β-Tm, which migrates more slowly, is present within the TnT band [5]. In Fig. 1a, the α-Tm/actomyosin ratio in the unregulated lane is 0.01 compared to 0.16 in the control lane and 0.17 in the reconstituted lane, representing 94% removal and full replacement. The average level of replacement of Tm from the mixREC reconstitution protocols was 96 ± 2% SEM (n = 4). Other reconstitutions, unlike mixREC, replace sTm with cTm. Rabbit fast skeletal Tm is composed of α and β isoforms, but the α form is reported to predominate in a ratio of 4:1 to β-Tm [5, 33]. The cTm and sTm replacement proteins used in reconstitutions were run on a 4–20% gel to determine the percentage composition of the isoforms (Fig. 1b). The cTm contained less than 1% β-Tm, whereas the sTm was 15% β-Tm and 85% α-Tm.

Fig. 1.

a Myofibril reconstitution preparation where the endogenous Tm and Tn were removed and replaced with sTm and cTn. Samples retained at each stage of the reconstitution protocol were run on a 12% Tris-HCl SDS gel and stained with coomassie blue. From left, the lanes shown are: control myofibrils, myofibrils after regulatory proteins have been extracted, myofibrils following reconstitution with sTm and cTn, the supernatant from the extraction stage of the protocol. The approximate amount of protein loaded into each lane is indicated. The TnC subunits were not visible due to poor stain retention of the protein at the concentrations present on the gel. The band present at 98–105 kDa is most likely α-actinin [38]. b Comparison of isoform content of the cTm and sTm used as replacement proteins. Samples (5 μg) were run on a 4–20% Tris-HCl SDS gel. The cTm is composed of 99% α-Tm, and sTm is 85% α-Tm and 15% β-Tm

Present in the extraction lane are myosin (two ~200 kDa bands are visible, representing myosin isoforms which are indistinguishable in other lanes due to the heavy myosin presence), actin and a 98–105-kDa protein (most likely α-actinin [38]). There are two potential sources of these proteins: (1) partial extraction during the extraction step and (2) the presence of some small myofibril debris that does not pellet at the low centrifugation speeds. The latter source would also contribute to the regulatory protein content in the extraction lane. Most of the proteins visible in the extraction lane, however, are from regulatory proteins, making up 63% of the total intensity of all bands in the lane. In all lanes, two contractile proteins, myosin light chain 3 and TnC, did not retain the stain during destaining.

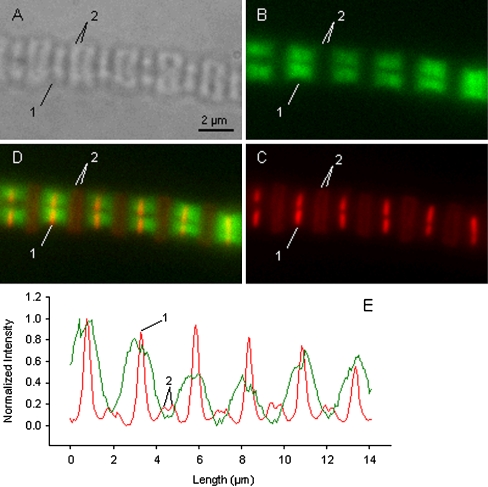

Fluorescence images of reconstituted myofibrils Myofibrils, reconstituted with gsTm and cTn, were used to determine to which sarcomeric structures exogenous tropomyosin attached. The gsREC myofibrils also underwent rhodamine phalloidin labeling of the actin filaments. Figure 2 shows images of the same gsREC myofibril (actually two myofibrils side-by-side) taken using light phase contrast (A), Oregon green fluorescence (B), RPh fluorescence (C), and a merge of images B and C (D). Image C shows that the most intense RPh labeling occurs at the Z-line. Two less intense bands can be seen between Z-lines indicating non-uniform labeling of the thin filaments by RPh. The low intensity bands mark the pointed ends of the thin filaments from opposing Z-lines within a given sarcomere. This labeling pattern confirms earlier work by Zhukarev et al. [45] who observed similar behavior and suggested the pattern was produced by nebulin in glycerinated fibers blocking uniform access of the RPh to actin monomers. The positions of a Z-line (1) and labeled tips (2) are marked in all images. Panel E shows the normalized fluorescent intensity profiles taken along the same length and in the same position of the myofibril in images B and C. The red line (image C, RPh) shows six high peaks marking the Z-lines (average SL 2.52 µm ±0.02 SEM (n = 5)), and in-between are two smaller peaks associated with actin-tip labeling. The green line (image B, Oregon green) shows high fluorescence on either side of the Z-line, but not at the thin filament tips. The width of gsTm binding, measured from the average base width of peaks, 2.10 µm ±0.24 SEM (n = 4), is approximately equal to the length of bipolar thin filaments [37]. Furthermore, image D shows that the gsTm is neatly located on either side of the Z-line and binds up to the thin filament tips. This staining pattern suggests that the gsTm has bound along the length of the thin filaments.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescent imaging of two side-by-side myofibrils following reconstitution with Oregon green-labeled Tm (ex. 488 nm, em. 512–530 nm), and labeling of the myofibril actin with rhodamine phalloidin (ex. 540 nm, em. 560–600 nm). a light image; b fluorescent image of the Oregon green label; c fluorescent image of the rhodamine phalloidin label. d merge of images b and c. e Normalized fluorescent intensity profile along the length of the myofibril in image b (green line) and image c (red line). Labeled in panels a–e are the positions of a Z-line (1) and the tips of the thin filaments (2). From panel e the average sarcomere length, measured from Z-line to Z-line, is 2.52 μm ±0.02 SEM (n = 5); and the average base width of peaks signifying Tm binding is 2.10 μm ±0.24 SEM (n = 4). In panels d and e the binding of the Tm is clearly shown to be along the thin filaments

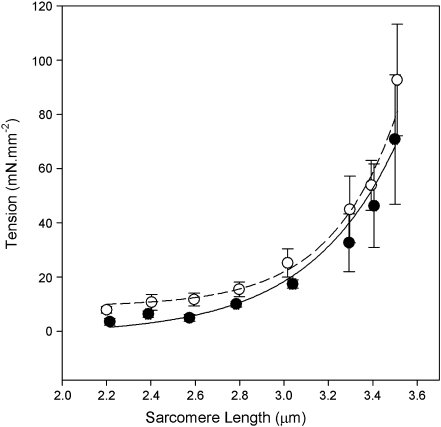

Mechanics of reconstituted myofibrils Mechanical data were collected for control myofibrils which had not undergone any reconstitution (CNTL) and myofibrils following reconstitution with various combinations of skeletal and cardiac tropomyosin and troponin: mixREC (sTm/cTn), gsREC (sgTm/cTn), cREC (cTm/cTn), and sREC (sTm/sTn). The success of the Tn and Tm extraction and replacement using exogenous proteins depends on maintenance of the muscle’s ability to be completely relaxed at high pCa values, to produce near maximal force and rate of force production upon exposure to lower pCa, and to produce similar force-pCa curves as control myofibrils. The passive length-tension curves of CNTL and sREC myofibrils were compared (Fig. 3). The passive length–tension relationship is similar to previous studies for single myofibrils [4]. An F test showed no significant difference between the two curves (P < 0.05). This suggests that the reconstituted myofibrils are as relaxed at high pCa as the control myofibrils and that virtually all regulatory protein binding sites have been occupied.

Fig. 3.

Passive length-tension curve of control and sREC single myofibrils. Data points are averages of six myofibrils, with force taken after 30 s equilibrium at each length. Control (open) and sREC (closed) data were fitted using the equation P = a + b.expc.SL. The dashed line is the control fit (a = 10 ± 10 SEE, b = 0.2 × 10−3 ± 0.5 × 10−3 SEE, c = 3.6 ± 0.7 SEE, R2 = 0.80), the solid line is the sREC fit (a = 0 ± 13 SEE, b = 6 × 10−3 ± 18 × 10−3 SEE, c = 2.6 ± 0.8 SEE, R2 = 0.80). 228 × 235 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

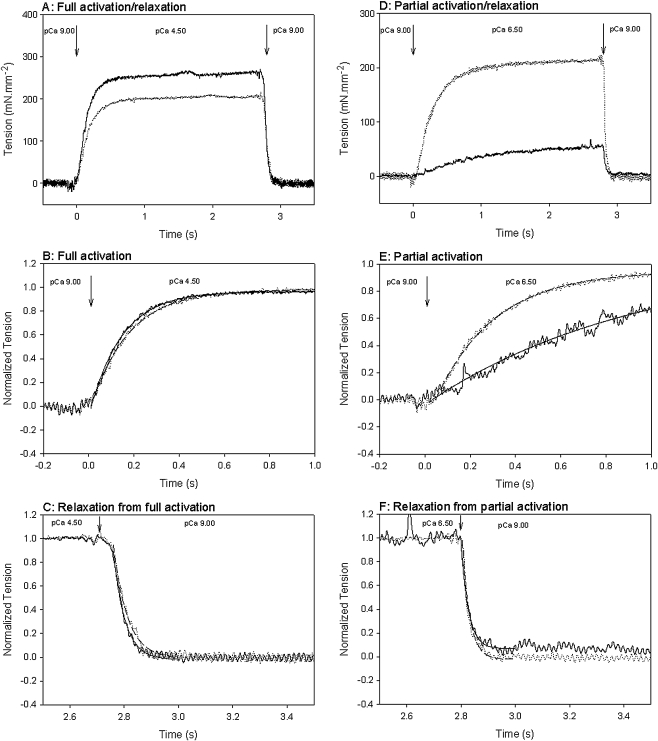

Typical force records obtained for control and sTm/cTn reconstituted myofibrils are shown in Fig. 4. Panel A compares the full activation and relaxation of a representative CNTL (fully active tension is 262 mN mm−2) and mixREC myofibril (fully active tension is 204 mN mm−2). The records in panel A have been normalized for maximum tension and the time axis expanded to better compare kact, panel B, and the fast rate of full relaxation (krel), panel C. Single exponentials fitted the data well and were used to measure the kact and krel rates. The CNTL kact was 5.6 s−1 and krel was 25 s−1; for the mixREC, kact was 4.9 s−1 and krel was 19 s−1. Table 1 shows that overall, average maximum isometric tensions of the reconstituted myofibrils (mixREC, sREC, gsREC, cREC) were significantly less than those of control myofibrils: approximately 84% of the control’s average maximal force. This result shows that following the reconstitution process, the myofibril remains mechanically viable and is capable of producing near normal forces. There was no significant difference between either the average fully active kact rates or krel rates, for any of the mixREC, sREC, gsREC, or cREC preparations and the control.

Fig. 4.

Representative tension records of fully and partially activated myofibrils at 10℃. Myofibrils were activated from pCa 9.00 to pCa 4.50 or 6.50 by switching of the flow pipette as described in text. Activation occurs at time zero. Arrows indicate the point of activation/relaxation. The tension level prior to activation was taken as the baseline. Measurements of kact and krel were made by fitting a single exponential to the tension record. Data filtered using a low pass filter (half-power point = 2, Sigma Plot 9.0). a Records shown are of a CNTL myofibril (heavy trace), and a mixREC myofibril (medium trace) fully activated at pCa 4.50. Tensions were 262 and 204 mN mm−2 respectively. b Same records as in a, but tensions have been normalized for comparison, and the time axis expanded. Exponential fits to the CNTL (solid line, R2 = 0.996) and mixREC (dashed line, R2 = 0.998) data give kact rates of 5.58 and 4.91 s−1, respectively. c Same records as in a, but tensions have been normalized for comparison, and the time axis expanded. Exponential fits to the CNTL (solid line, R2 = 1.00) and mixREC (dashed line, R2 = 0.98) data give krel rates of 23 and 19 s−1, respectively. d Records shown are of a CNTL myofibril (heavy trace), and a mixREC myofibril (medium trace), partially activated to pCa 6.50. Tensions were 51 and 210 mN mm−2, respectively. e Same records as in d, but tensions have been normalized for comparison and the time axis expanded. Exponential fits to the CNTL (solid line, R2 = 0.94) and mixREC (dashed line, R2 = 1.00) data give kact rates of 1.07 and 3.79 s−1, respectively. f Same records as in c, but tensions have been normalized for comparison and the time axis expanded. Exponential fits to the CNTL (solid line, R2 = 0.98) and mixREC (dashed line, R2 = 0.95) data give krel rates of 33 and 35 s−1, respectively; 173 × 197 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

Table 1.

Kinetic properties of control and reconstituted myofibrils at 10°C

| Myofibril preparation | Fully active tension, P0 (mN mm−2) | Rate of full tension development, kact (s−1) | Rate of full relaxation, krel (s−1) | [Ca2+] at half-maximum tension, pCa50 | Cooperativity, nH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (CNTL) | 261 ± 23 (n = 12) | 6.4 ± 1.3 (n = 12) | 29 ± 20 (n = 12) | 6.29 ± 0.01 | 2.92 ± 0.13 |

| sTm/sTn (sREC) | 211 ± 12 * (n = 6) | 5.3 ± 1.0 (n = 6) | 23 ± 3 (n = 5) | 6.38 ± 0.03 | 2.85 ± 0.27 |

| sTm/cTn (mixREC) | 228 ± 21 * (n = 5) | 5.1 ± 0.7 (n = 5) | 33 ± 11 (n = 5) | 6.92 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.09 |

| gsTm/cTn (gsREC) | 218 ± 9 * (n = 9) | 6.1 ± 0.4 (n = 9) | 39 ± 7 (n = 9) | 6.97 ± 0.01 | 1.90 ± 0.12 |

| cTm/cTn (cREC) | 220 ± 44 * (n = 9) | 5.1 ± 1.5 (n = 9) | 29 ± 14 (n = 9) | 6.68 ± 0.02 | 1.75 ± 0.17 |

| A63VTm/cTn (A63VREC) | 215 ± 41 * (n = 8) | 6.0 ± 1.1 (n = 8) | 32 ± 5 (n = 8) | 6.88 ± 0.02 | 2.01 ± 0.21 |

| Δ23Tm/cTn (Δ23REC) | 51 ± 10 * (n = 7) | 2.5 ± 0.3 * (n = 7) | 26 ± 6 (n = 7) | 6.76 ± 0.07 | 1.44 ± 0.28 |

Values for tension and rate of tension development/relaxation are mean averages ± SD. For each measured parameter (tension, kact, krel) a one-way ANOVA was used to test for differences across the myofibril preparations. Tension (F[6, 49] = 47, P < 0.001) and kact (F[6, 49] = 16, P < 0.001) values differed significantly among the preparations. Comparison of each reconstitution to the control was done using Fisher’s least significant difference (*P < 0.05, significantly different to the control). There was no significant difference in krel values among preparations (F[6, 48] = 1.4, P = 0.256). pCa50 and nH values are obtained by fitting Hill equation to data, as described in Figs. 6 and 7, ±SEE

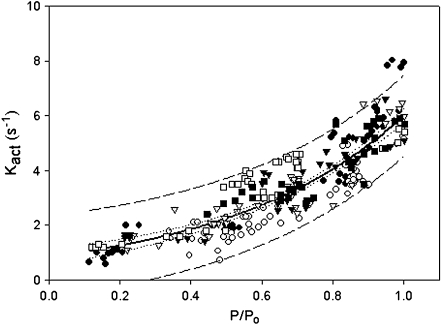

In panel D are representative records of a CNTL and mixREC myofibril submaximally activated at pCa 6.50. The CNTL develops 51 mN mm−2, whereas the mixREC tension is more than two times greater. This shows that mixREC, reconstituted with cTn, has an increased sensitivity to calcium. Panels E and F show the records in D normalized for tension. In panel E, the kact rate is slower for the CNTL—1.1 s−1 compared to 3.8 s−1 for the mixREC. Panel F compares the rates of full relaxation. Single exponentials fitted the fast rate well and were similar for the CNTL and mixREC—33 and 35 s−1, respectively. Figure 5 shows that the kact in myofibrils (mixREC, sREC, gsREC, cREC) is dependent on the fractional thin filament calcium activation, also previously shown by Colomo et al. [3] and Tesi et al. [40]. Despite the fact that myofibrils reconstituted with cTn displaying increased calcium sensitivity, plotting the kact rates against the relative tension developed were superimposable on the plots obtained from control myofibrils. Overall, the same pattern of increased kact at greater relative tension is followed.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between kact and level of calcium dependent activation (P/P0). Data from myofibril control (closed circles), mixREC (open circles), gsREC (open triangles), sREC (closed triangles), cREC (open squares), and A63VREC (closed squares) preparations are all plotted. All data are fitted using a single exponential:  . Where a = 0.01, b = 0.84, and c = 0.51. R2 = 0.96. Dashed lines are the 95% confidence intervals for the population; dotted lines are the 95% confidence intervals for the regression. 84 × 66 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

. Where a = 0.01, b = 0.84, and c = 0.51. R2 = 0.96. Dashed lines are the 95% confidence intervals for the population; dotted lines are the 95% confidence intervals for the regression. 84 × 66 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

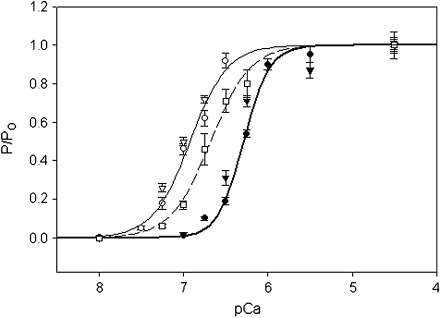

Figure 6 shows the pCa–force curves produced by CNTL, mixREC, and cREC myofibrils. Each dataset was fitted using the Hill equation to obtain the nH and pCa50 (Table 1). The nH and pCa50 variables for each regression were compared using an F test [7], allowing level of statistical difference between the reconstitutions to be identified. There was no statistically significant difference in the nH value between cREC and mixREC; both were significantly less than the CNTL and were, on average, one unit lower. This suggests that the cTn (present in cREC and mixREC) is the major cause of the reduction in cooperativity, and not the Tm. The pCa50 of cREC and mixREC were both significantly left-shifted from the CNTL. The mixREC myofibrils, which contained cTn and sTm (composed of both α- and β-Tm), caused the largest increases in calcium sensitivity, shifting the pCa50 left of the control by 0.63 units. When both the Tm and Tn are from a cardiac source (cREC), the shift in calcium sensitivity is reduced somewhat but is still 0.39 units left of the control, suggesting that the cTm (which has only α-Tm) reduces the degree of myofibrillar calcium sensitivity.

Fig. 6.

Relative force–pCa curves of myofibril reconstitutions. Control (filled circles), sREC (closed triangles), mixREC (open circles), gsREC (open triangles), and cREC (open squares) myofibril preparations at 10℃. All data points are averaged from five to 12 myofibrils, error bars are ±SEM. The heavy solid (control), light solid (mixREC), and dashed (cREC) lines are fits to the datasets using the Hill equation:  . See Table 1 for pCa50 and nH values, R2 of regressions were: control (0.99), mixREC (0.99), and cREC (0.97). The gsREC and sREC datasets were not used when fitting the Hill equations. 84 × 66 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

. See Table 1 for pCa50 and nH values, R2 of regressions were: control (0.99), mixREC (0.99), and cREC (0.97). The gsREC and sREC datasets were not used when fitting the Hill equations. 84 × 66 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

Also plotted on Fig. 6 are data points for pCa values obtained from gsREC and sREC myofibrils. The gsREC differed from mixREC by containing Oregon green labeled sTm. There was no significant change in the force-pCa characteristics of gsREC compared to mixREC, meaning the Oregon green label does not have an observable affect on myofibril function. The sREC contains the equivalent regulatory proteins of the CNTL, except the sREC myofibrils have undergone the reconstitution process. Again, there is no significant difference in the force-pCa characteristics of sREC myofibrils compared to CNTL, suggesting that the changes in nH and pCa50 are not an artifact of the reconstitution process.

Characterization of myofibrils reconstituted with A63V Tm or Δ23Tm Having established the effectiveness of the technique, myofibril reconstitutions were made using the cardiac Tm mutant with cTn (A63VREC) and the deletion mutant tropomyosin with cTn (Δ23REC). These reconstitutions are comparable to the cREC myofibrils. As shown in Table 1, the mechanical behavior of A63VREC was not significantly different from cREC. The relationship of kact to relative tension for A63VREC myofibrils followed the same pattern as for other reconstitutions (Fig. 5). Comparison of the pCa–force curves (Fig. 7; Table 1) shows no significant change in cooperativity, but the pCa50 of A63VREC was significantly shifted 0.20 units to the left of cREC, a change that must be attributed to the mutant Tm. A similar shift in pCa50 has also been seen in speed-pCa plots using A63V Tm in motility assays [15].

Fig. 7.

Relative force-pCa curves of myofibril reconstitutions. cREC (open squares), A63VREC (closed squares), and Δ23REC (open diamonds) myofibril preparations at 10℃. All data points are averaged from seven to nine myofibrils, error bars are ± SEM. The dashed (cREC), dotted (A63VREC), and heavy dashed (Δ23REC) lines are fits to the data sets using the Hill equation:  . See Table 1 for pCa50 and nH values, R2 of regressions were: cREC (0.97), A63VREC (0.97), and Δ23REC (0.99). 84 × 65 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

. See Table 1 for pCa50 and nH values, R2 of regressions were: cREC (0.97), A63VREC (0.97), and Δ23REC (0.99). 84 × 65 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

The Δ23REC myofibrils showed a large depression of maximal force (~77% lower) compared to cREC, and the activation rate was significantly slower, but there was no significant difference in krel (Table 1). Reconstitutions were also performed with an even shorter tropomyosin (Δ345Tm), but the fully relaxed myofibrils could not be activated even when the pCa was raised to 5 and no myofibrillar activity was seen (data not shown). The pCa–force curves of Δ23REC and cREC (Fig. 7) were compared for statistical difference using the same F test as previously. There was no significant difference in pCa50 between Δ23REC and cREC, but there was a significant reduction in cooperativity of Δ23REC (pCa50 and nH values are shown in Table 1).

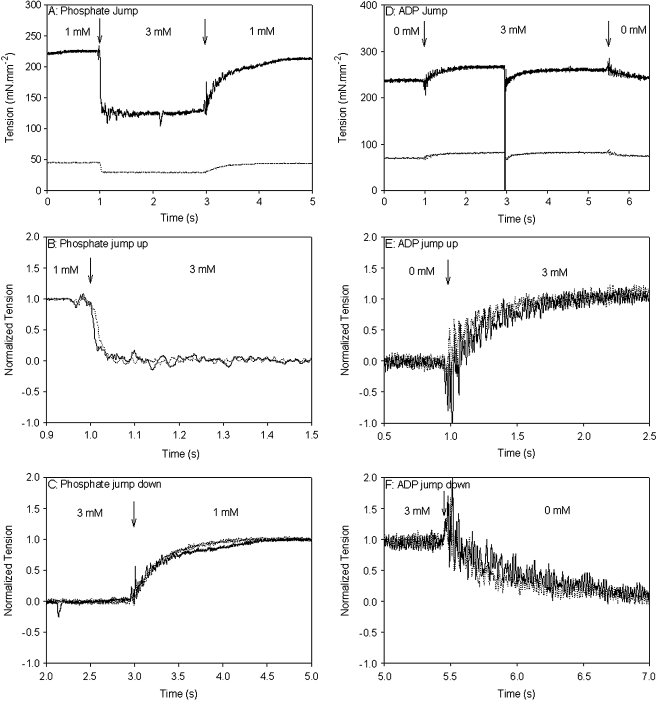

Phosphate and ADP kinetics of myofibrils reconstituted with Δ23Tm It could be that the shorter Tm alters the rates of product release/binding to actomyosin in such a way as to affect cooperativity and force production. This was investigated with phosphate jumps (from 1 to 3 mM and 3 to 1 mM) and ADP jumps (from 0 to 3 mM, and 3 to 0 mM) which were performed on control (myofibrils that had not undergone any reconstitution) and Δ23REC myofibrils. Figure 8a shows typical records for a phosphate jump experiment on control (solid line) and Δ23REC (dotted line) myofibrils. The jump up from 1 to 3 mM added phosphate occurs at 1 s resulting in a fast exponential decline in force. The records in panel A were normalized and shown on an expanded time axis in Fig. 8b to better compare the perturbation. The rapid force reduction following a rise in phosphate from 1 to 3 mM is fitted well by a single exponential (not shown in Fig. 8): the rate ( ) was 80 s−1 for the control and 62 s−1 for Δ23REC. At 3 s the phosphate was quickly reduced from 3 to 1 mM, which caused the force to return to its original level. Again, the records were normalized and shown on an expanded time axis in Fig. 8c for comparison. The tension rise was fitted with a single exponential (

) was 80 s−1 for the control and 62 s−1 for Δ23REC. At 3 s the phosphate was quickly reduced from 3 to 1 mM, which caused the force to return to its original level. Again, the records were normalized and shown on an expanded time axis in Fig. 8c for comparison. The tension rise was fitted with a single exponential ( ) and was 3.5 s−1 for the control and 3.0 s−1 for Δ23REC (fitting not shown in Fig. 8). The rates of force change following phosphate jumps, either up or down, were not significantly different between the control and Δ23REC myofibrils (Table 2), and

) and was 3.5 s−1 for the control and 3.0 s−1 for Δ23REC (fitting not shown in Fig. 8). The rates of force change following phosphate jumps, either up or down, were not significantly different between the control and Δ23REC myofibrils (Table 2), and  was 10–20 times greater than

was 10–20 times greater than  for both cREC and Δ23REC. Overall, the forces produced by Δ23REC myofibrils were ~80% less than the control (Table 2). The amount of force produced in the presence of 1-mM added phosphate, expressed as a percentage of maximum tension (no added phosphate, see forces in Table 1), was 85% and 92% in control and Δ23REC, respectively. At 3 mM added phosphate the amount of force generated was ~59% of maximum tension for both preparations.

for both cREC and Δ23REC. Overall, the forces produced by Δ23REC myofibrils were ~80% less than the control (Table 2). The amount of force produced in the presence of 1-mM added phosphate, expressed as a percentage of maximum tension (no added phosphate, see forces in Table 1), was 85% and 92% in control and Δ23REC, respectively. At 3 mM added phosphate the amount of force generated was ~59% of maximum tension for both preparations.

Fig. 8.

Typical tension records during phosphate and ADP jumps of control and Δ23REC myofibrils. Arrows indicate point of Pi/ADP jump. a Pi jump from 1 to 3 mM, and back to 1 mM for control (solid line) and Δ23REC (dotted line). b Normalized tensions from a with expanded time axis to compare the reduction in tension when phosphate is jumped from 1 to 3 mM. c normalized tensions from a with expanded time axis to compare the increase in tension when Pi is jumped from 3 to 1 mM. d ADP jump from 0 to 3 mM, and back to 0 mM for control (solid line) and Δ23REC (dotted line). At 3 s a stretch-release length step was imposed to obtain a ktr rate at 3 mM ADP (see text). e Normalized tensions from d with expanded time axis to compare the increase in tension when ADP is jumped from 0 to 3 mM. f Normalized tensions from d with expanded time axis to compare the decrease in tension when ADP is jumped from 3 to 0 mM. 173 × 202 mm (150 × 150 DPI)

Table 2.

Kinetic properties of control and Δ23REC myofibrils at 10℃ during phosphate and ADP jumps

| Control | Δ23REC | |

|---|---|---|

Jump up: 1 to 3 mM Pi,  (s−1) (s−1) |

74 ± 12 (n = 5) | 58 ± 6 (n = 5) |

Jump down: 3 to 1 mM Pi,  (s−1) (s−1) |

3.8 ± 0.8 (n = 8) | 3.5 ± 0.2 (n = 9) |

| Tension at 1 mM Pi, P1 (mN mm−2) | 222 ± 17 (n = 10) | 47 ± 4 (n = 10) * |

| Tension at 3 mM Pi, P3 (mN mm−2) | 154 ± 13 (n = 10) | 30 ± 3 (n = 10) * |

| Rate of tension redevelopment at 1 mM Pi, ktr1 (s−1) | 7.1 ± 0.4 (n = 10) | 4.3 ± 0.5 (n = 10) * |

| Rate of tension re-development at 3 mM Pi, ktr2 (s−1) | 9.7 ± 0.7 (n = 9) | 7.0 ± 0.4 (n = 8) * |

| Jump up: 0 to 3 mM ADP, k+ADP (s−1) | 4.7 ± 0.6 (n = 8) | 3.6 ± 0.2 (n = 7) |

| Jump down: 3 to 0 mM ADP, k-ADP (s-1) | 4.2 ± 0.4 (n = 8) | 4.0 ± 0.5 (n = 7) |

| Tension at 3 mM ADP, Pd (mN mm−2) | 283 ± 20 (n = 8) | 53 ± 10 (n = 8)* |

| Rate of tension redevelopment at 3 mM ADP, ktrd (s−1) | 4.2 ± 0.2 (n = 8) | 1.9 ± 0.2 (n = 6)* |

Values are mean averages ± SEM * Statistically significantly different to the control (P < 0.05, Student’s t test)

Figure 8d shows typical records for an ADP jump experiment on control (solid line) and Δ23REC (dotted line) myofibrils. The jump up to 1 mM added ADP occurs at 1 s and results in a rise in force, and the jump back down to no added ADP occurs at 5.5 s and the force returns to its original level. Figure 8e (jump up) and f (jump down) show the records in (d) normalized and on expanded time axis so that the perturbations produced in the control and Δ23REC myofibrils can be compared. Both processes can be fitted with single exponentials (not shown): k+ADP rates were 3.6 and 4.5 s−1 for control and Δ23REC myofibrils, respectively; and k−ADP rates were 4.6 and 5.0 s−1 for control and Δ23REC myofibrils, respectively. There was no significant difference in the k+ADP or k−ADP kinetics between Δ23REC and controls (Table 2). Also, the k+ADP and k−ADP rates themselves were not significantly different. The amount of force potentiation produced with 3 mM added ADP was 8% for controls and 4% for Δ23REC.

The method of activation used in these phosphate and ADP jump experiments precluded direct measurement of kact rates (cf. methods). Instead, rapid release-stretch length steps were performed to obtain ktr rates, which have been shown to be equivalent to kact [40]. Rates for ktr rates were obtained at 1 and 3 mM phosphate and 3 mM ADP for control and Δ23REC myofibrils. Overall, compared to kact rates with no added phosphate or ADP (Table 1), phosphate increased the ktr and ADP slowed the ktr for both control and Δ23REC myofibrils (Table 2).

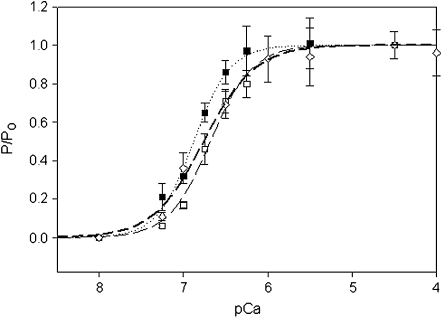

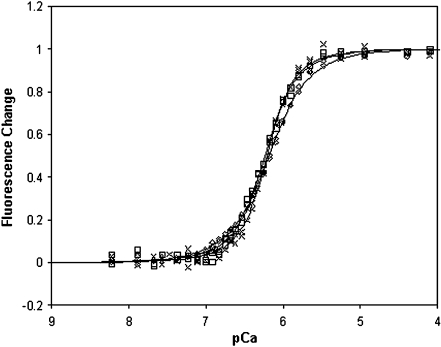

Solution properties of thin filaments containing Δ23Tm To elucidate the mechanism of the above effects of the shortened Δ23Tm, Ca2+ binding to thin filaments containing this altered Tm were examined in solution in the absence of myosin. Cardiac Tn that was fluorescently tagged on the TnC regulatory domain was added to thin filaments containing either full length Tm or Δ23Tm, in amounts sufficient to fill all Tn binding sites on the thin filaments: one Tn per 7 actins for control thin filaments, and one Tn per five actins in thin filaments containing Δ23Tm. When corrected for the troponin concentration, the fluorescence intensity in the presence of EGTA was unaffected by which Tm was present. However, when saturating Ca2+ was added, the fluorescence increased 65 ± 4% for control thin filaments and only 31 ± 5% for thin filaments containing Δ23Tm (data not shown). Interestingly, the pattern of the deletion mutant’s effects ran parallel to those observed in myofibrils. Not only did Ca2+ activation produce smaller effects in both types of experiments but also in both experiments the Ca2+-induced transitions occurred with lower cooperativity and an unaffected Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Normalized fluorescence–pCa curves for thin filaments in solution containing control Tm or Δ23Tm. The IAANS-Tn fluorescence intensity increased when Ca2+ was added to thin filaments containing Δ23Tm (diamonds and thin line), cTm (squares and solid line), or full length recombinant ala-ser Tm (multiplication symbol and bold line). For each Tm, pooled data for several titrations were globally fit to a model of cooperative binding to a linear lattice [44]. Cooperativity parameter Y is the fold-increase in Ca2+ affinity for a troponin with a nearest neighbor Tn in the Ca2+-bound state, and Y1/2 ≈ nH. Binding was less cooperative in the presence of Δ23Tm: Y = 2.77 ± 0.12 vs values for cTm and ala-ser Tm of 4.49 ± 0.32 and 5.96 ± 0.45. Corresponding Ca2+ affinities differed minimally by no more than a few percent: 1.52 ± 0.03 × 106, 1.71 ± 0.03 × 106, and 1.61 ± 0.03 × 106 M−1

Discussion

Effective Tm removal and replacement with maintenance of mechanical and regulatory properties An important aspect of the present work is the demonstration that one tropomyosin can be replaced with another in muscle preparations, using a non-genetic technique that is more reliable and more reproducible than coarser methods such as gelsolin treatment [23], which has been successfully adopted by few investigators, using only cardiac tissue, and results in variable thin filament lengths. The reconstitution method presented here had minimal impact on myofibril mechanics: on average reconstituted preparations produced 84% of the maximum force produced by nonreconstituted myofibrils. Some degree of force deterioration is seen in other experiments attempting myofilament protein exchanges [21]. Here, the SDS-PAGE analysis shows some loss of actomyosin during the extraction, which may result in tension loss. The loss of other proteins, such as light chains, may also deteriorate the maximum force, and although the gels suggest light chain loss is small, the effect could be significant. However, as shown in Fig. 3, there is no difference in the rest tension between reconstituted and nonreconstituted myofibrils, suggesting almost all regulatory binding sites have been occupied.

The SDS-PAGE analysis also demonstrated the effectiveness of the reconstitution protocol. Gels revealed that the reconstitution of α-Tm was approximately 96% complete (the β-Tm isoform was not identified as a separate band as it co-migrates with TnT).

Reconstituting myofibrils with fluorescently labeled Tm made it possible to confirm the gsTm’s location along the myofibril in areas identified as the thin filaments, and to which it was expected to bind. Mechanical experiments with gsREC myofibrils demonstrated that the gsTm was completely functional. The characteristics of gsREC myofibrils (maximum force, kact, nH, pCa50) were no different from mixREC myofibrils (equivalent to gsREC myofibrils, except none of the sTm was labeled), indicating the Oregon green label on Tm has little or no effect on the regulatory mechanism.

In these experiments, myofibrils completely relaxed to their pre-activation level. The rate of the fast phase of relaxation was fairly constant in all experiments, regardless of the type of reconstitution or level of activation; the overall rate was ~30 s−1. Preceding the fast phase a slow, linear phase occurs lasting approximately 50 ms at a rate of 1–2 s−1 (data not shown). Similar relaxation kinetics have previously been observed [40]. Relaxation is not a parameter appreciably altered by the regulatory proteins used in these experiments.

Opposite effects of cTn and cTm on pCa50 of skeletal muscle myofibrils In skeletal muscle fibers, myofibril reconstitutions using cTn produced an increased calcium sensitivity compared to preparations using sTn (CNTL, sREC). The shift can be attributed to the presence of cTn, demonstrating that it was successfully reconstituted. The ability, however, of those myofibrils to regulate provides further evidence that the Tm must have also been successfully reconstituted. The mixREC myofibrils showed a 0.54–0.63 pCa unit leftward shift compared to control reconstitutions (sREC) or untreated control myofibers (CNTL). This is a shift of similar magnitude to the 0.74 unit change seen by Piroddi et al. [31] in whole cardiac troponin exchange experiments. This large effect of cardiac troponin had not been predicted by fiber studies, although comparisons of the calcium sensitivity of muscle types are difficult because pH, sarcomere length, and various sarcomeric protein differences each have complex effects on calcium sensitivity. The present data offer a partial explanation: the effects of troponin and tropomyosin substitution are opposite, thereby diminishing the large effect of cardiac troponin on calcium sensitivity. This can be seen by comparison of fibers with cardiac troponin and either skeletal tropomyosin (pCa50 6.92) or cardiac tropomyosin (pCa50 6.68). The close homology between bovine cardiac and rabbit skeletal α-Tm suggests the decreased calcium sensitivity of cREC myofibrils is caused by the very small amount of β-Tm in cardiac tropomyosin (cREC) verses the significant amount of β-Tm (15–20%) in skeletal tropomyosin (mixREC). This is exactly the functional effect one might predict from the heretofore puzzling structural observation that, in the absence of troponin, the predominant azimuthal position of tropomyosin on actin filaments depends upon tropomyosin isoform. Skeletal Tm tends to expose a larger portion of the myosin binding site on actin [20]. The present functional data are also in agreement with near in vivo studies using whole hearts from transgenic mice over-expressing β-Tm [27]. Experiments on fiber bundles from the same hearts also showed increased calcium sensitivity in the transgenic mice [29]. One implication of these results is that the variation in α and β tropomyosin ratios in fast and slow skeletal muscle, and cardiac muscle is an adaptation which fine tunes calcium sensitivity.

The force-pCa data obtained in these experiments show a reduction in the cooperativity when cardiac Tn replaces skeletal Tn. In earlier studies of cardiac-for-skeletal Tn exchange, using either whole Tn [1, 31] or TnC only [26], the effect on the Hill coefficient is similar to the current data. It has been proposed that the reduced cooperativity of fibers containing cardiac Tn is a consequence of cardiac TnC’s single calcium binding site, compared to two in the skeletal form [25, 26, 31]. The data presented here supports the view that this factor is contributing, since it is a likely consequence of the interactions between the two EF hands in the skeletal muscle TnC regulatory domain. The present work suggests further that isoform-specific troponin–tropomyosin interactions are not likely to be a part of this because nH was indistinguishable for two groups of fibers with cardiac troponin: those with skeletal muscle and those with cardiac tropomyosin.

Effects of the A63V tropomyosin mutation The mechanical characteristics of myofibrils reconstituted with the cardiac A63V tropomyosin mutation were compared to those of the cREC myofibrils. The A63VREC myofibrils left-shifted the pCa50 by 0.2 units but caused no significant change in the cooperativity. Similar effects of the mutation have also been seen in ATPase and motility assays [15], though the motility assay did show a significant decrease in cooperativity. We now show that there is no effect on force or cross-bridge kinetics. An adenoviral trans-gene study in cardiac myocytes also showed similar steady-state effects [24]. The A63V mutation is at a position in the tropomyosin molecule which is involved in the coiled–coil interactions. Based on thermal denaturation studies [15], the mutation decreases the stability of the N-terminal of tropomyosin by 35%. The decreased stability may allow easier access of the myosin to actin binding sites, thus, increasing the myofibrils’ sensitivity to calcium compared to cREC. Greatly decreased stability might be expected to decrease cooperativity, which is not seen. However, the stability decrease is only moderate, and the notable functional effects parallel those seen in Fig. 6: the sequence difference in tropomyosin, here in the N-terminal region where Tn does not bind, affects the pCa50 and not the cooperativity of activation.

Effects of the Δ23 tropomyosin Further information on the N-terminal half of tropomyosin, and on the regulatory mechanism, has been obtained from the results using Δ23Tm. The most striking features of myofibrils reconstituted with Δ23Tm are the large reduction in tension (23% of cREC) and the slower kact (twofold difference to cREC). The lower tension must result from either fewer attached cross-bridges, less force per cross-bridge, or both. The concomitant reduction in activation rate indicates the shorter tropomyosin suppresses the kinetics of cross-bridge cycling. Steps in the cross-bridge cycle were probed by monitoring the transient kinetics in force production following rapid changes in phosphate and ADP concentration. The results from ADP jump experiments gave rates consistent with those previous reported [39]. The phosphate jumps from 1 to 3 mM produced a characteristic rapid drop in force [6]. The rate of decline in force ( ) in myofibrils is similar to values previous reported in fibers [6] and, allowing for temperature differences, in myofibrils [39]. We find the

) in myofibrils is similar to values previous reported in fibers [6] and, allowing for temperature differences, in myofibrils [39]. We find the  to be 10–20 times slower than

to be 10–20 times slower than  , and, in controls, half the rate of ktr. This is in contrast to Tesi et al. [39], where ktr and k

, and, in controls, half the rate of ktr. This is in contrast to Tesi et al. [39], where ktr and k were similar at 5℃. Ultimately, there was no significant difference in the

were similar at 5℃. Ultimately, there was no significant difference in the  ,

,  , k+ADP or k−ADP rates between Δ23REC and controls, suggesting the Δ23Tm affects neither the product release or binding steps in the cross-bridge cycle. The most likely remaining possibility is that the presence of Δ23Tm slows cross-bridge attachment, or the weak to strong AM.ADP.Pi transitions.

, k+ADP or k−ADP rates between Δ23REC and controls, suggesting the Δ23Tm affects neither the product release or binding steps in the cross-bridge cycle. The most likely remaining possibility is that the presence of Δ23Tm slows cross-bridge attachment, or the weak to strong AM.ADP.Pi transitions.

The pCa–force curves showed the Δ23Tm had no significant effect on the calcium sensitivity of the myofibril (compared to cREC), which is in agreement with the results of motility assays [23]. This suggests the Δ23Tm–troponin interactions remain intact [17]. Reconstitutions using Δ345Tm produced no tension, again in agreement with the lack of activity seen in motility and ATPase assays [18]. Published motility studies on Δ23Tm did not provide data on cooperativity [18], but our data showed a 0.31-unit reduction compared to cREC myofibrils. A similar experiment using a different technique (gelsolin digestion of thin filaments) observed the opposite: an increase in cooperativity [23]. However, we believe that the results reported here are more reliable than in the earlier study, which are additionally complicated by substrate gradients likely to exist in a preparation of that size. In combination with lower isometric tension, less cooperation is a logical outcome due to fewer (or weaker) cross-bridge attachments to help activate the thin filament.

Solution studies have shown that the equilibrium of S1-ADP binding to regulated thin filaments is minimally affected by the deletion within Δ23Tm in the presence of Ca2+ [43]. Interestingly, the same study showed that such suppression of myosin attachment does occur in the absence of Ca2+: Δ23Tm thin filaments switch with excessive cooperativity from an inhibited binding state to a state with tight S1 binding to actin. Combining these results with the present study, one concludes that deleting Tm quasi-repeats 2 and 3 suppresses strong myosin binding in EGTA and also, with more subtlety, both do (present work) and do not (prior solution data, cited above) inhibit strong binding in presence of Ca2+.

This apparent paradox is actually a reflection of the normal, regulation phenomenon, i.e., the effects of troponin–tropomyosin in the absence of Ca2+, here only imperfectly reversed by the addition of Ca2+ to thin filaments containing Δ23Tm. S1-ADP binding to Ca2+-saturated Δ23Tm thin filaments is not greatly suppressed, but neither is it profoundly impaired by removing Ca2+ from normal thin filaments in solution. Rather, the greater effect on normal thin filaments in solution, the greater consequence of the removal of Ca2+, is the profound slowing of the transition of bound S1 to states that allow product release, phosphate and then ADP [14]. The effect of Ca2+ removal on the rate of S1-ADP attachment to thin filaments is much more modest.

Similarly, but now in myofibrils saturated with Ca2+, Δ23Tm acts to reduce both the rate of weak-to-strong actomyosin transitions and the total number of strongly bound cross-bridges. This interpretation of the myofibril data meshes with the solution studies (Fig. 9). Ca2+ fails to normally activate the filaments, with a loss of myosin-independent cooperativity and a smaller fluorescence change. A cooperative Ca2+-induced change is a prerequisite, the results suggest, for the full activation of myosin function, including the weak to strong transition. The deletion of only regions 2 and 3 enable the tropomyosin to maintain its interactions with troponin [17] contributing to the negligible effect on calcium sensitivity. After cross-bridges enter the strongly bound state, their subsequent kinetic activity (phosphate and ADP release) are unaffected.

Finally, a recent structural study of the thin filament is important to note. The core domain and other parts of troponin appear to physically restrain, from both sides, the C-terminal half of tropomyosin to a position on actin that sterically interferes with myosin attachment [9]. This may leave the actins in contact with the more N-terminal portion of tropomyosin as particularly important sites for myosin attachment. The greater number of short Tm needed to bind the length of a thin filament would also suggest that more Tn is bound. This raises the possibility that the increase in the proximity of Tn binding sites may further hinder movement of Tm and reduce exposure of cross-bridge binding sites.

In summary, the protocol presented here describes a method for replacing the regulatory proteins in skeletal myofibrils. The technique almost completely replaces the endogenous Tn and Tm, and the resultant myofibrils are mechanically intact to a high degree. Replacing the Tm as well as the Tn allowed mutant Tm proteins, such as those associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, to be introduced into skeletal myofibrils, and the contractile changes produced by the mutant observed. Additionally, the protocol was used for several structure-function studies of tropomyosin, and particularly on the effects of removing the second and third quasi-repeats. This region is required for the full activating effect of Ca2+ on the thin filament, which is necessary for the initial weak-to-strong cross-bridge interactions of myosin and actin, though the precise nature of the mechanism will require further study.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to J. Tidball (Physiological Sciences Deptartment, UCLA) and T. Sakamoto (Laboratory of Molecular Physiology, NHLBI, NIH) for their assistance in obtaining fluorescent images, and also M. Regnier (Department of Bioengineering, University of Washington) and R. Petraitiene (POB, NCI, NHLBI) for tissue samples. Supported by NIH grants AR30988 (EH) and HL38834 (LST), and HL63774 (LST).

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Brenner B, Kraft T, Yu LC, Chalovich JM (1999) Thin filament activation probed by fluorescence of N-((2-(Iodoacetoxy) ethyl)-N-methyl) amino-7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1, 3-diazole-labeled troponin I incorporated into skinned fibers of rabbit psoas muscle. Biophys J 77(5):2677–2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Chang AN, Harada K, Ackerman MJ, Potter JD (2005) Functional consequences of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy-causing mutations in alpha-tropomyosin. J Biol Chem 280(40):34343–34349 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Colomo F, Nencini S, Piroddi N, Poggesi C, Tesi C (1998) Calcium dependence of the apparent rate of force generation in single striated muscle myofibrils activated by rapid solution changes. Adv Exp Med Biol 453:373–381 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Colomo F, Piroddi N, Poggesi C, Te Kronnie G, Tesi C (1997) Active and passive forces of isolated myofibrils from cardiac and fast skeletal muscle of the frog. J Physiol 500(Pt 2):535–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cummins P, Perry SV (1973) The subunits and biological activity of polymorphic forms of tropomyosin. Biochem J 133(4):765–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Dantzig JA, Goldman YE, Millar NC, Lacktis J, Homsher E (1992) Reversal of the cross-bridge force-generating transition by photogeneration of phosphate in rabbit psoas muscle fibers. J Physiol 451:247–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.DeLean A, Munson PJ, Rodbard D (1978) Simultaneous analysis of families of sigmoidal curves: application to bioassay, radioligand assay, and physiological dose-response curves. Am J Physiol 235(2):E97–E102 [On which the AllFit (1988) program was based (http://abs.cit.nih.gov/allfit/)] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Fabiato A, Fabiato F (1978) Calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned cells from adult human, dog, cat, rabbit, rat, and frog hearts and from fetal and new-born rat ventricles. Ann NY Acad Sci 307:491–522 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Galińska-Rakoczy A, Engel P, Xu C, Jung H, Craig R, Tobacman LS, Lehman W (2008) Structural basis for the regulation of muscle contraction by troponin and tropomyosin. J Mol Biol 379(5):929–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Godt RE (1974) Calcium-activated tension of skinned muscle fibers of the frog. Dependence on magnesium adenosine triphosphate concentration. J Gen Physiol 63:722–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Gong H, Hatch V, Ali L, Lehman W, Craig R, Tobacman LS (2005) Mini-thin filaments regulated by troponin-tropomyosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(3):656–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gordon AM, Regnier M, Homsher E (2001) Skeletal and cardiac muscle contractile activation: tropomyosin "rocks and rolls". News Physiol Sci 16:49–55 [PubMed]

- 13.Graceffa P (1999) Movement of smooth muscle tropomyosin by myosin heads. Biochem 38:11984–11992 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Heeley DH, Belknap B, White HD (2002) Mechanism of regulation of phosphate dissociation from actomyosin-ADP-Pi by thin filament proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99(26):16731–16736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Heller MJ, Nili M, Homsher E, Tobacman LS (2003) Cardiomyopathic tropomyosin mutations that increase thin filament Ca2+ sensitivity and tropomyosin N-domain flexibility. J Biol Chem 278(43):41742–41748 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hill LE, Mehegan JP, Butters CA, Tobacman LS (1992) Analysis of troponin-tropomyosin binding to actin. Troponin does not promote interactions between tropomyosin molecules. J Biol Chem 267(23):16106–16113 [PubMed]

- 17.Hitchcock-DeGregori SE, Varnell TA (1990) Tropomyosin has discrete actin-binding sites with sevenfold and fourteenfold periodicities. J Mol Biol 214(4):885–896 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Landis C, Back N, Homsher E, Tobacman LS (1999) Effects of tropomyosin internal deletions on thin filament function. J Biol Chem 274(44):31279–31285 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Landis CA, Bobkova A, Homsher E, Tobacman LS (1997) The active state of the thin filament is destabilized by an internal deletion in tropomyosin. J Biol Chem 272(22):14051–14056 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Lehman W, Hatch V, Korman V, Rosol M, Thomas L, Maytum R, Geeves MA, Van Eyk JE, Tobacman LS, Craig R (2000) Tropomyosin and actin isoforms modulate the localization of tropomyosin strands on actin filaments. J Mol Biol 302(3):593–606 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Ling N, Shrimpton C, Sleep J, Kendrick-Jones J, Irving M (1996) Fluorescent probes of the orientation of myosin regulatory light chains in relaxed, rigor, and contracting muscle. Biophys J 70(4):1836–1846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193(1):265–275 [PubMed]

- 23.Lu X, Tobacman LS, Kawai M (2003) Effects of tropomyosin internal deletion Delta23Tm on isometric tension and the cross-bridge kinetics in bovine myocardium. J Physiol (Lond) 553(2):457–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Michele DE, Albayya FP, Metzger JM (1999) Direct, convergent hypersensitivity of calcium-activated force generation produced by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutant alpha-tropomyosins in adult cardiac myocytes. Nat Med 5(12):1413–1417 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Morris CA, Tobacman LS, Homsher E (2003) Thin filament activation and unloaded shortening velocity of rabbit skinned muscle fibers. J Physiol 550(Pt 1):205–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Moss RL, Lauer MR, Giulian GG, Greaser ML (1986) Altered Ca2+ dependence of tension development in skinned skeletal muscle fibers following modification of troponin by partial substitution with cardiac troponin C. J Biol Chem 261(13):6096–6099 [PubMed]

- 27.Muthuchamy M, Grupp IL, Grupp G, O'Toole BA, Kier AB, Boivin GP, Neumann J, Wieczorek DF (1995) Molecular and physiological effects of overexpressing striated muscle beta-tropomyosin in the adult murine heart. J Biol Chem 270(51):30593–30603 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Ogawa Y (1968) The apparent binding constant of glycoletherdiaminetetraacetic acid for calcium at neutral pH. J Biochem (Tokyo) 64:255–257 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Palmiter KA, Kitada Y, Muthuchamy M, Wieczorek DF, Solaro RJ (1996) Exchange of beta- for alpha-tropomyosin in hearts of transgenic mice induces changes in thin filament response to Ca2+, strong cross-bridge binding, and protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 271(20):11611–11614 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Perry SV (2001) Vertebrate tropomyosin: distribution, properties and function. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 22(1):5–49 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Piroddi N, Tesi C, Pellegrino MA, Tobacman LS, Homsher E, Poggesi C (2003) Contractile effects of the exchange of cardiac troponin for fast skeletal troponin in rabbit psoas single myofibrils. J Physiol 552(Pt 3):917–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Potter JD (1982) Preparation of troponin and its subunits. Methods Enzymol 85(Pt B):241–263 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Salviati G, Betto R, Danieli Betto D (1982) Polymorphism of myofibrillar proteins of rabbit skeletal-muscle fibers. An electrophoretic study of single fibers. Biochem J 207(2):261–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Schwarzenbach G, Senn H, Anderegg G (1957) Komplexone XXIX. Ein grosser Chelateffekt besonderer Art. Helv Chim Acta 40:1886–1900 [DOI]

- 35.She M, Trimble D, Yu LC, Chalovich JM (2000) Factors contributing to troponin exchange in myofibrils and in solution. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 21(8):737–745 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Smillie LB (1982) Preparation and identification of alpha- and beta-tropomyosins. Methods Enzymol 85(Pt B):234–241 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Sosa H, Popp D, Ougyang G, Huxley HE (1994) Ultrastructure of skeletal muscle fibers studied by a plunge quick freezing method: Myofilament lengths. Biophys J 67:283–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Suzuki A, Goll DE, Singh I, Allen RE, Robson RM, Stromer MH (1976) Some properties of purified skeletal muscle alpha-actinin. J Biol Chem 251(21):6860–70 [PubMed]

- 39.Tesi C, Colomo F, Nencini S, Piroddi N, Poggesi C (2000) The effect of inorganic phosphate on force generation in single myofibrils from rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophys J 78(6):3081–3092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Tesi C, Piroddi N, Colomo F, Poggesi C (2002) Relaxation kinetics following sudden Ca(2+) reduction in single myofibrils from skeletal muscle. Biophys J 83(4):2142–2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Thirlwell H, Corrie JE, Reid GP, Trentham DR, Ferenczi MA (1994) Kinetics of relaxation from rigor of permeabilized fast-twitch skeletal fibers from the rabbit using a novel caged ATP and apyrase. Biophys J 67(6):2436–2447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Tobacman LS, Adelstein RS (1986) Mechanism of regulation of cardiac actin-myosin subfragment 1 by troponin-tropomyosin. Biochem 25:798–802 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Tobacman LS, Butters CA (2000) A new model of cooperative myosin-thin filament binding. J Biol Chem 275(36):27587–27593 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Tobacman LS, Sawyer D (1990) Calcium binds cooperatively to the regulatory sites of the cardiac thin filament. J Biol Chem 265(2):931–939 [PubMed]

- 45.Zhukarev V, Sanger JM, Sanger JW, Goldman YE, Shuman H (1997) Distribution and orientation of rhodamine-phalloidin bound to thin filaments in skeletal and cardiac myofibrils. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 37(4):363–377 [DOI] [PubMed]