Abstract

Oxidative stress (OS) has been implicated as one of the major underlying mechanisms behind many acute and chronic diseases. However, the measurement of free radicals or their end products is complicated. Isoprostanes, derived from the non-enzymatic peroxidation of arachidonic acid are now considered to be reliable biomarkers of oxidant stress in the human body. Isoprostanes are involved in many of the human diseases such as type 2 diabetes. In type 2 diabetes elevated levels of F2-Isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs) have been observed. The measurement of bioactive F2-IsoPs levels offers a unique noninvasive analytical tool to study the role of free radicals in physiology, oxidative stress-related diseases, and acute or chronic inflammatory conditions. Measurement of oxidative stress by various other methods lacks specificity and sensitivity. This review aims to shed light on the implemention of F2-IsoPs measurement as a gold-standard biomarker of oxidative stress in type 2 diabetics.

Keywords: oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, isoprostanes, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

“Oxidative stress (OS)” due to the imbalance between pro-oxidant/antioxidant status results in generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent modification of biomolecules such as protein, lipids and nucleic acids. Excessive generation of ROS has been implicated in a variety of pathological events such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disease [1]. Lipid peroxidation (LPO) is the main marker of oxidative stress. Oxidative damage of cellular membranes has been suggested as a common mechanism in a large number of biopathological conditions. It can be measured by either primary or secondary end products of peroxidation. Primary end products of lipid peroxidation include conjugated dienes and lipid hydroperoxides, while secondary end products include thiobarbituric reactive substances (TBARS), gaseous alkanes and a group of prostaglandin (PG) F2-like products termed F2-isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs) [2, 3].

Studies have shown that F2-isoprostanes are reliable biomarkers of lipid peroxidation [4] and could therefore, be used as potential indicators of oxidative stress in diverse conditions. Bioactive F2-isoprostanes (8-Iso-PGF2α) are regularly formed in various tissues and small amounts can be found in the unmetabolized form in plasma and higher levels in urine in normal basal conditions. Their role in the regulation of normal physiological conditions has yet to be elucidated. This paper reviews the role of F2-IsoPs as novel biomarkers of oxidative stress in relation to type 2 diabetes.

Mechanism of F2-IsoPs Formation

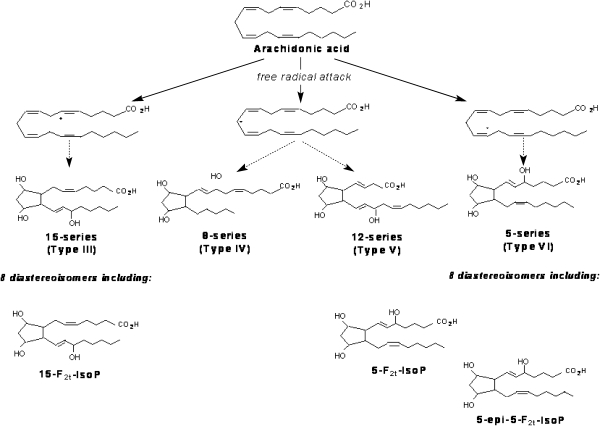

IsoPs are a family of PG-like compounds formed non-enzimatically through free radical catalysed attack on esterified arachidonate followed by enzymatic release from cellular or lipoprotein phospholipids (Fig. 1). IsoPs are formed in situ in the phospholipid domain of cell membranes and circulating lipoproteins. They are then cleaved by phospholipases, released extra-cellularly, circulate in blood and are excreted in urine. The measurement of F2-IsoPs, containing the F-type ring analogous to PGF2α, provides a reliable tool for identifying enhanced rates of lipid peroxidation.

Fig. 1.

Formation of F2-Isoprostanes from arachidonic acid, leading to four F2-Isoprostane regioisomers (Adapted from ref. 54)

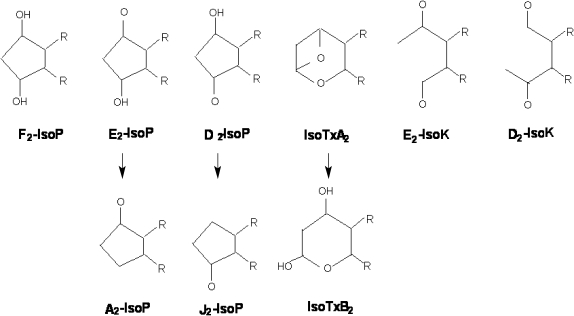

Formation of PG-like compounds during auto-oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids was first reported in the mid-1970s [5], but isoprostanes were not discovered in humans until 1990 [6]. F2-isoprostanes are a group of 64 compounds isomeric in structure to cyclooxygenase-derived PGF2α. Other products of the isoprostane pathway are also formed in vivo by rearrangement of labile PGH2-like isoprostane intermediates. These include E2- and D2-isoprostanes [7], cyclopentenone-A2- and J2-isoprostanes [8], and the highly reactive acyclic-ketoaldehydes (isoketals) [9] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Tx: thromboxane. IsoK: isoketals (Adapted from ref. 55)

Biological Effects of F2-IsoPs

The discovery of isoprostanes has important implications for medicine [7]. It has now been established that measurement of F2-isoprostanes is the most reliable approach to assess oxidative stress status in vivo, providing an important tool to explore the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of human disease. In addition, products of the isoprostane pathway have been found to exert potent biological actions and therefore may be pathophysiologic mediators of disease. IsoPs 8-iso-PGF2α and 8-iso-PGE2 possess potent biological effects in various systems and they also serve as mediators of oxidant stress through their vasoconstrictive [10] and inflammatory properties. 8-iso-PGF2α, have been well known to have vasoconstictive effects in various organs including aorta [11], brain [12], cerebral arterioles [13], kidney [6, 10], the lung [14, 15], pulmonary artery [6], retinal vessels and endothelium [16]. Administration of 8-iso-PGF2α to rabbit induces COX-mediated PGF2α formation which has shown to be related to inflammation [17, 18].

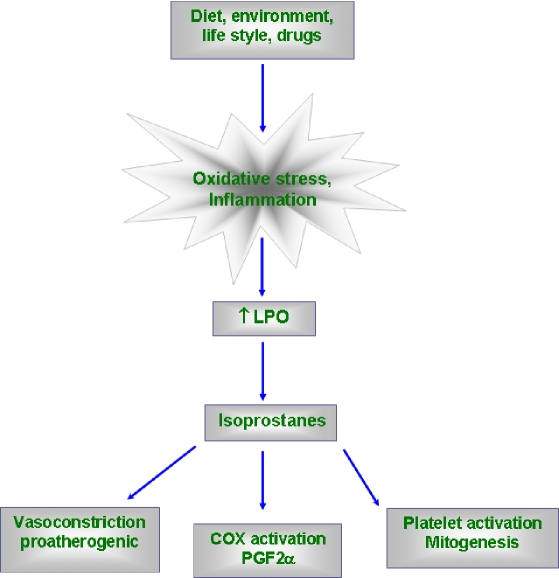

Isoprostanes induces inflammation and atherogenesis through activation of MAP kinases [19]. Isoprostanes possess important in vitro activities that could be relevant to the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. It promotes platelet activation [20] and induces mitogenesis in vascular smooth muscle cells [10], stimulates proliferative responses in fibroblasts [21], alters endothelial cell biology as indicated by proliferative effects and increased endothelin-1 expression in bovine aortic endothelial cells [22]. A simplified schematic sketch about its biological effects is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

A simplified sketch showing biological effects of F2-Isoprostanes

Mechanism of Action of F2-IsoPs

Biological effects of IsoPs are mediated by interaction with receptor. The cyclopentenone-IsoPs such as PGA2 and PGJ2 like compounds, form protein adduct by reacting with glutathione [8]. Isoketals, the byproducts of IsoPs pathway rapidly adduct to lysine residues on proteins and induce cross-linkages [9]. It’s still uncertain about the receptors involved in IsoPs actions. The vasoconstricting action is mediated through thromboxane (Tx) receptor antagonists [23]. It acts as antagonist in Tx induced platelet aggregation [24] and induces vasoconstriction in retinal and brain vasculature by endothelial Tx formation [25].

Metabolism of IsoPs

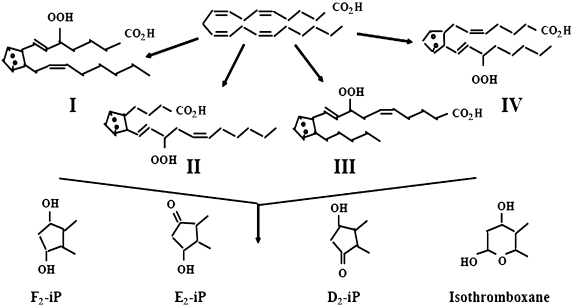

IsoPs are produced in situ in their esterified form in tissues and bioconvert first to their free acid form (Fig. 4) and are distributed in both the esterified and free acid form in tissues [26, 27]. Hydrolytic enzymes that are ubiquitous in the body are primarily responsible for the formation of free isoprostanes from their esterified moiety in the tissues and these are released into the circulation. Pharmacokinetic and metabolic studies revealed the half life of 8-iso-PGF2α to be ~16 min in humans and ~4 min in plasma. In vitro and in vivo studies showed that the metabolism of IsoPs occurs through prostaglandins [28, 29] and confirms that β-oxidation is the common degradation pathway in the later step of metabolism of IsoPs.

Fig. 4.

Formation of free F2-Isops from the esterified moiety (Adapted from ref. 56)

Biomarkers of LPO and OS

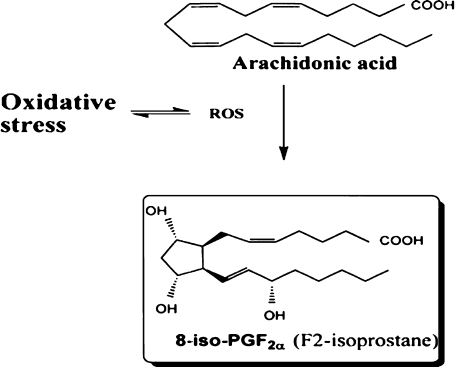

Oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) by free radicals results in excess production of toxic byproducts of peroxidation [30], which is the major underlying mechanism of development of various diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular and neurological diseases [1]. There exists a lack of reliable analytical methods for detection of peroxidation in vivo or its end products [2]. A number of studies have revealed the favorable properties of F2-IsoPs as biomarkers for peroxidation and its levels are regarded as the reliable approach for the assessment of peroxidation or OS in vivo [6, 31, 32, 33, 34]. The schematic diagram of the formation of 8-Iso-PGF2α, a major F2-IsoPs from arachidonic acid is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Biosynthesis of 8-Iso-PGF2α (F2-IsoPs) (Adapted from ref. 34)

IsoPs in Type 2 Diabetes

OS is implicated in the development of diabetic complications [35] by its association with peroxidation of membrane lipids and LDL-cholesterol. These peroxidation products can impair beta cell function and induce apoptosis [36]. Factors that promote increased oxidative stress in diabetes include antioxidant deficiencies, increased production of ROS, and the process of glycation and glyco-oxidation [35]. The most common antioxidant deficiencies reported in diabetes are lower levels of ascorbate, glutathione and superoxide dismutase [37]. Lower concentrations of reduced glutathione have been documented in diabetic neutrophils and monocytes while lower concentrations of ascorbate have been found in both diabetic plasma and mononuclear cells.

Direct evidence of increased oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in diabetes has been reported. F2-IsoPs are prostaglandin-like compounds formed in-vivo from free radical catalyzed peroxidation of arachidonic acid and have emerged as novel and direct measures of oxidative stress. IsoPs, derived from the non-enzymatic peroxidation of arachidonic acid are associated with hyperglycemia, vasoconstriction and diabetic nephropathy [38, 39]. F2-Isops, in urine or plasma, provide a highly precise and reliable approach to assess lipid peroxidation in vivo [31]. F2-IsoPs have been found to be increased in both type I and type II diabetes [40]. Increased isoprostane levels were observed in plasma and urine of type 2 diabetes (NIDDM) [40, 38]. Gopaul et al. [40] have reported that 8-iso-PGF2α (a major F2-IsoPs) was found to be threefold higher in type 2 diabetics than in healthy individuals. In addition, increased urinary excretion of 8-iso-PGF2α was statistically significant in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis [41]. There exists a significant correlation between blood glucose and urinary IsoPs levels, suggesting that peroxidation is related to glycemic control. In vascular smooth muscle cells, F2-IsoPs formation was found to be induced by in vitro by high glucose concentrations [42]. Further, the suggestion that impaired glycemic control is responsible for enhanced formation of F2-IsoPs in type II disease is also supported by the finding that intensive antidiabetic treatment resulted in reductions in blood glucose levels and in urinary IsoP levels [38]. Improved metabolic control of type 2 diabetic patients significantly reduced urinary 8-iso-PGF2α levels by 32%. Furthermore improved glycemic control by pancreatic islet transplantation reduces vascular oxidative stress and reverses antioxidant enzyme upregulation in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes are consistent with hyperglycemia as the source of oxidative stress [42].

Hyperglycemia, a major common feature of diabetes has been implicated as the source of metabolic derangement. Increase in 8-iso-PGF2α was significantly correlated with blood glucose and increased platelet activation. Activation of platelets by hyperglycemia paralleled oxidative stress [43]. These results strongly suggest that increased lipid peroxidation in diabetic patient’s leads to the formation of 8-iso-PGF2α, which, in turn, leads to platelet activation. This is of interest because F2-IsoPs are ligands for the TPx receptor [44]. In another study, levels of esterified. F2-IsoPs in plasma lipids were quantified in 61 patients who underwent coronary angiography. The extent of coronary atherosclerosis in the diabetic patients was similar to that in the 46 nondiabetic individuals. Plasma levels of F2-IsoPs measured in the diabetic patients (33.4 ± 4.8 pg/mL, mean ± SEM) were found to be significantly increased compared with levels measured in the nondiabetic patients (22.2 ± 1.9 pg/mL) (p<0.02). Plasma F2-IsoP concentrations were found to be increased by 34% in acute hyperglycemia and this is similar to other models of oxidative damage. Increased plasma esterified 8-epi-F2α-IsoPs were reported in heavy smokers by Morrow et al. [45]. 8-epi-F2α-IsoPs possess biologically important proatherogenic actions, and serves as well as a marker for free radical damage. Under in vitro condition it promotes platelet adhesion to collagen and antagonizes the action of nitric oxide.

Laight et al. [46] recently reported a 5 fold increase in plasma 8-iso-PGF2α, in the obese Zucker rat, a model of insulin resistance. Supplementation of vitamin-E reduced plasma 8-iso-PGF2α and reversed hyperinsulinemia. Alpha tocopherol therapy significantly decreased oxidative susceptibility of LDL as manifest by prolongation of the lag phase. In both diabetic groups with and without vascular complications the O2− anion release was increased and that this could be attenuated with high dosage alpha tocopherol therapy (1200 IU/RRR-AT). Furthermore, alpha tocopherol therapy resulted in a reduction in IL1-β, TNF-α, IL-6 and C-reactive protein in the diabetic group.

Hyperglycemia contributes significantly to microvascular disease. The combination of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension contributes to cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk even before glucose intolerance develops. High plasma levels of homocysteine are an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease [47]. The mechanism by which hyperhomocysteinemia induces atherosclerosis is not fully understood but promotion of LDL oxidation has been suggested. The relationship between total plasma concentrations of homocysteine and F2-IsoPs has been explored [48]. Plasma concentrations of F2-IsoPs increased linearly across quintiles of homocysteine levels. The simple correlation coefficient for association between plasma concentrations of homocysteine and F2-IsoPs was 0.40 (p<0.0001). The finding of a positive correlation between plasma concentrations of F2-IsoPs and homocysteine supports the suggestion that the underlying the link between high homocysteine levels and risk for cardiovascular disease may be enhanced lipid peroxidation.

In accordance with the LDL oxidation hypothesis of atherosclerosis, levels of F2-IsoPs should be higher in atherosclerotic plaques than in normal vascular tissue. To address this issue, levels of F2-IsoPs were measured in fresh advanced atherosclerotic plaque tissue removed during arterial thrombarterectomy (n = 10) and compared with levels measured in normal human umbilical veins removed from the placenta immediately after delivery (n = 10) [49]. Levels of esterified F2-IsoPs in vascular tissue normalized to both wet weight and dry weight were significantly higher in atherosclerotic plaques compared to normal vascular tissue. A better measure of the actual extent of oxidation, however, may be obtained by normalizing the data to the amount of arachidonic acid present in the tissue since it is the substrate for IsoP formation. When the data was normalized to arachidonic acid content, the F2-IsoP/arachidonic acid ratio was ~4-fold higher in diseased tissue than the ratio in normal vascular tissue (p = 0.009). This finding indicates that unsaturated fatty acids in atherosclerotic plaques are more extensively oxidized than lipids in normal vascular tissue. These observations are also in accord with data from FitzGerald and colleagues who have shown increased amounts of F2-IsoPs in human atherosclerotic lesions and the localization of F2-IsoPs in atherosclerotic plaque tissue to foam cells and vascular smooth muscle cells [50]. While 8-iso-PGF2α, plays a pivotal role in patients with insulin resistance and hyperglycemia its role is still unclear in subjects without evident hyperglycemia.

Comprehensive Treatment

Diabetes-related complications may be limited with much better glycemic control. Good glycemic control can reduce microvascular complications of the eyes, kidneys, and nerves. CVD is the most common and clinically important secondary complication in adults with diabetes [51]. CVD affects up to 80% of those with diabetes and accounts for approximately 70% of mortality in diabetes patients. Diabetes increases the risk of CVD 2 to 4 times [52], and the risk is greatest for women [53]. Data suggest that individuals with diabetes have a risk of CVD events that is comparable with that of individuals without diabetes who have preexisting CVD. Abnormalities in blood pressure or lipids will have a greater negative impact on diabetic patients than on those without diabetes. Type 2 diabetes should not be regarded simply as a metabolic syndrome, but as a vascular syndrome with metabolic consequences, including hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. Indeed, type 2 diabetes generally arises in the same metabolic setting as CVD. Obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance are common to both conditions. This fact and the presence of modifiable risk factors in patients with diabetes suggest that early and aggressive treatment can significantly reduce the risk of heart disease hence the requirement for good markers for this disease and its complications.

Conclusion

OS is the major pathogenic origin for acute and chronic diseases. Available biomarkers for OS are unreliable for assessing the oxidative damage in vivo which results in substandard interpretation of role of OS in various diseases. Current evidences presented above in the review unveil the possibility and reliability of IsoPs as valid biomarkers for the evaluation of OS. Being a bioactive compound it is involved in the normal physiology such as human pregnancy and in the pathology of inflammation. This should help us to explore the role of free radicals in the pathogenesis of human diseases. Further research in this area is necessary to provide insight into the role of OS in human diseases.

Abbreviations

- OS

oxidative stress

- LPO

lipid peroxidation

- IsoPs

Isoprostanes

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TBARS

thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- PG

prostaglandin

- PGF2α

prostaglandin F2α

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- Tx

thromboxane

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- NIDDM

non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus

References

- 1.Halliwell B., Gutteridge J.M.C. Free radicals in Biology and Medicine, 3rd ed. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliwell B., Grootveld M. The measurement of free radical reactions in humans. FEBS Lett. 1978;213:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrow J.D., Harris T.M., Roberts L.J. Noncyclooxygenase oxidative formation of a series of novel prostaglandins: analytical ramifications for measurement of eicosanoids. Anal. Biochem. 1990;184:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90002-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mezzetti A., Cipollone F., Cuccurullo F. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular complications in diabetes: Isoprostanes and new markers on an old paradigm. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000;47:475–488. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pryor W.A., Stanely J.P., Blair E. Autoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids; II. A suggested mechanism for the formation of TBA-reactive materials from prostaglandin-like endoperoxides. Lipids. 1976;11:370–379. doi: 10.1007/BF02532843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrow J.D., Hill K.E., Burk R.F., Nammour T.M., Badr K.F., Roberts L.J. A series of prostaglandin F2–like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:9383–9387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J. The isoprostanes: unique bioactive products of lipid peroxidation. Prog. Lipid Res. 1997;36:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(97)00001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y., Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J. II. Formation of reactive cyclopentenone compounds in vivo as products of the isoprostane pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10863–10868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brame C.J., Salomon R.G., Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J., II Identification of extremely reactive γ-ketoaldehydes (isolevuglandins) as products of the isoprostane pathway and characterization of their lysyl protein adducts. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13139–13146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi K., Nammour T.M., Fukunaga M., Ebert J., Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J.D., Hoover R.L., Badr K.F. Glomerular actions of a free radical-generated novel prostaglandin, 8-epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha, in the rat: evidence for interaction with thromboxane A2 receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90:136–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI115826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner R.S., Weare C., Jin N., Mohler E.R., Rhoades R.A. Characterization of signal transduction events stimulated by 8-epi-prostaglandin (PG) F2 alpha in rat aortic rings. Prostaglandins. 1997;54:581–599. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(97)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman S.W., Moore S., Ellis E.F. Isoprostanes: free radical-generated PGs with constrictor effects on cerebral arteries. Stroke. 1997;28:844–849. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.4.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou X., Roberts L.J. II., Taber D.F., Morrow J.D., Kanai K., Gobeil F. Jr., Beauchamp M.H., Bernier S.G., Lepage G., Varma D.R., Chemtob S. 2,3-Dinor-5,6-dihydro-15-F(2t)-isoprostane: a bioactive prostanoid metabolite. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2001:R391–R400. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.2.R391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee M., Kang K.H., Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J., Newman J.H. Effects of a novel prostaglandin, 8-epi-PGF2 alpha, in rabbit lung in situ. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:H660–H663. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.3.H660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernareggi M., Rossoni G., Berti F. Bronchopulmonary effects of 8-epi-PGF2A in anaesthetized guinea pigs. Pharmacol. Res. 1998;37:75–80. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1997.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahaie I., Hardy P., Hou X., Hassessain H., Asselin P., Lachapelle P., Almazan G., Varma D.R., Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J. 2nd., Chemtob S. A novel mechanism for vasoconstrictor action of 8-isoprostaglandin F2 alpha on retinal vessels. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:R1406–R1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.5.R1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu S. F2-Isoprostane induced prostaglandin formation in the rabbit. Free Radic. Res. 2006;40:273–280. doi: 10.1080/10715760500511492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu S. Radioimmunoassay of 15-keto-13,14-dihydro-prostaglandin F2a: an index for inflammation via cyclooxygenase catalysed lipid peroxidation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1998;58:347–352. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(98)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholz H., Yndestad A., Damås J.K., Waehre T., Tonstad S., Aukrust B., Halvorsen P. 8-isoprostane increases expression of interleukin-8 in human macrophages through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;59:945–954. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrono C., FitzGerald G.A. Isoprostanes: potential markers of oxidant stress in atherothrombotic disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;17:2309–2315. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunapuli P., Lawson J.A., Rokach J., FitzGerald G.A. Functional characterization of the ocular prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) receptor. Activation by the isoprostane, 12-iso-PGF2α. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27147–27154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yura T., Fukunaga M., Khan R., Nassar G.N., Badr K.F., Montero A. Free-radical-generated F2-isoprostane stimulates cell proliferation and endothelin-1 expression on endothelial cells. Kidney Int. 1999;56:471–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Audoly L.P., Rocca B., Fabre J.E., Koller B.H., Thomas D., Loeb A.L., Coffman T.M., FitzGerald G.A. Cardiovascular responses to the isoprostanes iPF2α-III and iPE2-III are mediated via the thromboxane A2 receptor in vivo. Circulation. 2000;101:2833–2840. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.24.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrow J.D., Minton T.S., Roberts L.J., II The F2-isoprostane, 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α, a potent agonist of the vascular thromboxane/endoperoxide receptor, is a platelet thromboxane/endoperoxide receptor antagonist. Prostaglandins. 1992;44:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(92)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou X., Gobeil F. Jr, Peri K., Speranza G., Marrache A.M., Lachapelle P., Roberts L.J. II., Varma. D.R., Chemtob S. Augmented vasoconstriction and thromboxane formation by 15-F2t-isoprostane (8-iso-PGF2α) in immature pig periventricular brain microvessels. Stroke. 2000;31:516–525. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.2.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sodergren E., Vessby B., Basu S. Radioimmunological measurement of F2-isoprostanes after hydrolysis of lipids in tissues. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2000;63:149–152. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrow J.D., Awad J.A., Boss H.J., Blair I.A., Roberts L.J. II. Non-cyclooxygenase derived prostanoids (F2-isoprostanes) are formed in situ on phospholipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10721–10725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basu S. Metabolism of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α. FEBS Lett. 1998;428:32–36. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00481-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu S. Metabolism of 8-iso-PGF2a in the rabbit. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1998;428:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halliwell B. Free radicals, antioxidants, and human disease: curiosity, cause, or consequence? Lancet. 1994;10:721–724. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts L.J. II., Morrow J.D. Measurement of F2-isoprostanes as an index of oxidative stress in vivo. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:505–513. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cracowski J.L., Durand T., Bessard G. Isoprostanes as a biomarker of lipid peroxidation in humans: physiology, pharmacology and clinical applications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002;135:360–366. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawson J.A., Rokach J., FitzGerald G.A. Isoprostanes: formation analysis and use of indicies of lipid peroxidation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;27:24441–24444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basu S. Carbon tetrachloride induced lipid peroxidation: eicosanoid formation and its regulation by antioxidants. Toxicology. 2003;189:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baynes J.W. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:405–412. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miwa I., Ichimura N., Sugiura M., Hamada Y., Taniguchi S. Inhibition of glucose-induced insulin secretion by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and other lipid peroxidation products. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2767–2772. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.8.7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oranje W.A., Wolffenbutte B.H. Lipid peroxidation and atherosclerosis in type II diabetes. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1992;134:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davì G., Ciabattoni G., Consoli A., Mezzetti A., Falco A., Santarone S., Pennese E., Vitacolonna E., Bucciarelli T., Costantini F., Capani F., Patrono C. In vivo formation of 8-iso-prostaglandin f2alpha and platelet activation in diabetes mellitus: effects of improved metabolic control and vitamin E supplementation. Circulation. 1999;99:224–229. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mezzetti A., Cipollone F., Cuccurullo F. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular complications in diabetes: isoprostanes as new markers on an old paradigm. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000;47:475–488. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gopaul N.K., Anggård E.E., Mallet A.I., Betteridge D.J., Wolff S.P., Nourooz-Zadeh J. Plasma 8-epi-PGF2 alpha levels are elevated in individuals with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:225–229. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00649-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Catella-Lawson F., Kapoor S., Pratico D., Braunstein S.N., Caraballo V., FitzGerald G.A. Oxidative stress and diabetes mellitus. J. Invest. Med. 1996;44:223A. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Natarajan R., Lanting L., Gonzales N., Nadler J. Formation of an F2-isoprostane in vascular smooth muscle cells by elevated glucose and growth factors. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H159–H165. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.1.H159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davì G., Gresele P., Violi F., Basili S., Catalano M., Giammarresi C., Volpato R., Nenci G.G., Ciabattoni G., Patrono C. Diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension but not vascular disease per se are associated with persistent platelet activation in vivo. Evidence derived from the study of peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 1997;96:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fam S.S., Morrow J.D. The isoprostanes: unique products of arachidonic acid oxidation-a review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:1723–1740. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrow J.D., Frei B., Longmire A.W., Gaziano J.M., Lynch S.M., Shyr Y., Strauss W.E., Oates J.A., Roberts L.J. 2nd. Increase in circulating products of lipid peroxidation (F2-isoprostanes) in smokers. Smoking as a cause of oxidative damage. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1198–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laight D.W., Desai K.M., Gopaul N.K., Anggård E.E., Carrier M.J. F2-isoprostane evidence of oxidant stress in the insulin resistant, obese Zucker rat: effects of vitamin E. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;377:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boushey C.J., Beresford S.A., Omenn G.S., Motulsky A.G. A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. Probable benefits of increasing folic acid intakes. JAMA. 1995;274:1049–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530130055028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voutilainen S., Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J., Alfthan G., Alho H., Nyyssonen K., Salonen J.T. Enhanced in vivo lipid peroxidation at elevated plasma total homocysteine levels. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999;19:1263–1266. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.5.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gniwotta C., Morrow J.D., Roberts L.J., Kuhn H. Prostaglandin F2-like compounds, F2-isoprostanes, are present in increased amounts in human atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;17:3236–3241. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pratico D., Iuliano L., Mauriello A., Spagnoli L., Lawson J.A., Rokach J., Maclouf J., Violi F., FitzGerald G.A. Localization of distinct F2-isoprostanes in human atherosclerotic lesions. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:2028–2034. doi: 10.1172/JCI119735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haffner S.M., Lehto S., Ronnemaa T., Pyörälä K., Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kannel W.B., McGee D.L. Diabetes and glucose tolerance as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Study. Diabetes Care. 1979;2:120–126. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sowers J.R. Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in women. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158:617–621. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marlière S., Cracowski J.L., Durand T., Chavanon O., Bessard J., Guy A., Stanke-Labesque F., Rossi J.C., Bessard G. The 5-series F(2)-isoprostanes possess no vasomotor effects in the rat thoracic aorta, the human internal mammary artery and the human saphenous vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1276–1280. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montuschi P., Barnes P.J., Roberts L.J. 2nd. Isoprostanes: markers and mediators of oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2004;18:1791–1800. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2330rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patrignani P., Tacconelli S. Isoprostanes and other markers of peroxidation in atherosclerosis. Biomarkers. 2005;10:S24–S29. doi: 10.1080/13547500500215084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]