Abstract

Background

Germline mutations in the BHD tumor suppressor are associated with an increased risk for kidney cancer among patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome. BHD encodes folliculin, a novel protein that may interact with the energy- and nutrient-sensing 5′-AMP activated protein kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin (AMPK-mTOR) signaling pathways.

Methods

We used recombineering methods to generate mice with a conditional BHD allele and introduced the cadherin 16 (KSP)-Cre transgene to target BHD inactivation to the kidney. Kidney cell proliferation was measured by BrdU incorporation and phosphohistone H3 staining. Kidney weight data were analyzed with Wilcoxon’s rank-sum, Student’s t, and Welch’s t tests. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunoblot analysis and immunohistochemistry of cell cycle and signaling proteins were performed on mouse kidney cells and tissues. BHD knockout mice and kidney cells isolated from BHD knockout and control mice were treated with rapamycin to assess effects of mTOR inhibition on mouse kidney cells and survival. Mouse survival was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

BHD-knockout mice developed enlarged polycystic kidneys and died from renal failure by 3 weeks of age. Targeted BHD-knockout led to the activation of Rafextracellular signal regulated protein kinase (Erk)1/2 and Akt-mTOR pathways in the kidneys and increased expression of cell cycle proteins and cell proliferation. Rapamycin treated BHD knockout mice had reduced kidney size (relative kidney /body weight ratios [100 X kidney weight / (body weight-kidney weight)]; buffer versus rapamycin: mean=12.2% versus 4.64%, difference=7.6%, 95% CI=5.2 to 10.0) and longer median survival time than untreated mice (41.5 versus 23 days).

Conclusions

Homozygous loss of BHD may be the initiating event for renal tumorigenesis in the mouse. The conditional BHD-knockout mouse is a useful research model for dissecting multistep kidney carcinogenesis. Rapamycin is a potential treatment for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome is an inherited kidney cancer syndrome that is characterized by benign hair follicle tumors, lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and an increased risk of renal neoplasia (1-3). We previously identified germline mutations in the BHD gene, which is located at chromosome 17p11.2, in BHD patients (4). Nearly all BHD mutations are frameshift or nonsense mutations that are predicted to prematurely truncate the BHD protein, folliculin (FLCN) (4-7). BHD patients most frequently develop bilateral multifocal chromophobe renal tumors and renal oncocytic hybrid tumors with features of chromophobe renal carcinoma and renal oncocytoma (8-10). Somatic mutations in the remaining wild-type copy of BHD and loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 17p11.2 have been identified in BHD-associated renal tumors, supporting the Knudson “two-hit” hypothesis and a tumor suppressor role for BHD (11).

Folliculin is a novel 64-kDa protein with no known functional domains (4). We recently identified FNIP1, the first folliculin-interacting protein, which also interacts with 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK (12)), an important energy sensor in cells that negatively regulates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), the master switch for cell growth and proliferation (13). We demonstrated that FLCN and FNIP1 could serve as substrates for AMPK in vitro and in vivo and that inhibition of AMPK activity resulted in reduced phosphorylation and decreased expression of these proteins. Phospho-folliculin levels were reduced by inhibition of mTOR activity. Under serum-starved conditions, the level of mTOR signaling was somewhat higher in BHD-null renal tumor cells than in BHD-restored cells (12). These results suggest that FLCN may play a role in cellular energy and nutrient sensing through interactions with the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway. Mutations in several other tumor suppressor genes, including LKB1 (14), PTEN (15), and TSC1/2 (16), have been shown to lead to dysregulation of mTOR signaling and to the development of other hamartoma syndromes. Intriguingly, recent studies in yeast have suggested that Bhd activates Tor2 in opposition to the role of Tsc1/2 , which inhibits Tor2 in this model organism (17).

Animal models of human cancer provide valuable research tools for dissecting the biochemical pathways responsible for neoplasia and for testing new therapeutic agents. Renal cystadenocarcinoma nodular dermatofibrosis (RCND) in dogs (18,19) and renal tumors in the Nihon rat (20,21) occur in animals that inherit a germline mutation in the corresponding BHD homolog. However, these naturally-occurring animal models may harbor additional genetic changes that could confound studies of the functional consequences of BHD inactivation. A genetically engineered mouse model provides a “clean” system with which to pursue FLCN functional studies.

Here we report the generation of a conditionally targeted BHD allele and kidney-directed BHD inactivation in the mouse using the cadherin16 (KSP)-Cre transgene (22). We compared BHD-knockout and control kidneys by histology, cell proliferation measurements, immunostaining to evaluate activation of Raf-Erk1/2 and Akt-mTOR pathways, and evaluated the therapeutic effects of rapamycin treatment, an inhibitor of mTOR, on the BHD-knockout kidney phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generating a BHD Conditional Targeting Vector and Kidney-Specific BHD-Targeted Mouse

The BHD targeting vector was generated by the recombineering method, which uses homologous recombination in Escherichia coli strain DY380 (23). A neomycin resistance (Neor) cassette, flanked by Frt and loxP sequences, was inserted into intron 6 of BHD for positive selection, and the thymidine kinase gene was included for negative selection. A second loxP sequence was inserted into intron 7. The targeting vector was electroporated into mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells and selected for G418 resistance and gancyclovir sensitivity. Correctly targeted ES cells were identified by Southern blot analysis and injected into blastocysts to produce chimeras. Backcrossing to C57BL/6 mice produced heterozygous F1 offspring with germline transmission of the BHD floxed (f) allele. The retained Neo cassette flanked by Frt sites was excised in vivo by crossing the heterozygous BHD floxed (BHDf/+) F1 mice with mice expressing the Flp recombinase transgene under the ubiquitous β-actin promoter to produce BHDf/+/Flp mice . Subsequently, the Flp transgene was removed from the BHDf/+/Flp mice by backcrossing to C57BL/6 mice to produce BHDf/+ mice. BHDf/f mice were generated by intercrossing BHDf/+mice. To produce the BHD deleted (d) allele, BHDf/+ mice were crossed with mice expressing the Cre recombinase transgene under the ubiquitous β-actin promoter resulting in BHDd/+/β-actin Cre mice (24). The β-actin Cre transgene was removed from the BHDd/+/β-actin Cre mice by backcrossing to C57BL/6 mice resulting in BHDd/+ mice. Deletion of exon 7 in the BHDd/+ mice resulted in a frame shift and premature termination codon in exon 8. Cadherin 16 (KSP)-Cre transgenic mice (n=4), which expressed Cre recombinase under the cadherin 16 promoter specifically in the adult renal tubules and developing genitourinary tract (22), were crossed with BHDd/+ mice(n=6) to generate BHDd/+/KSP-Cre mice (n=39). To produce mice with kidney-specific inactivation of BHD, BHDd/+/KSP-Cre male mice (n=10) were mated with BHDf/f female mice (n=13) Littermates with the BHDf/d/KSP-Cre genotype (n=89) and BHDf/+/KSP-Cre genotype (n=84) were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation or decapitation and analyzed for phenotype at day 2, 7, 14 and 21.

To verify that BHD knockout was targeted to the kidney and to visualize Cre expression, we developed BHDf/d/Rosa26lacZ/KSP-Cre mice. BHDf/f mice were crossed with Rosa26lacZ mice (obtained from Philippe Soriano, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) to produce BHDf/+/Rosa26lacZ mice (n=10). BHDf/+/Rosa26lacZ mice (n=6) were intercrossed to produce BHDf/f /Rosa26lacZ mice (n=5). BHDf/f /Rosa26lacZ female mice (n=2) were crossed with BHDd/+/KSP-Cre male mice (n=2) to generate BHDf/d/Rosa26lacZ/KSP-Cre mice. A total of 837 mice were used in these experiments and were housed in the NCI-Frederick animal facility in standard cages with food and water ad libidum, grouped by age, sex and strain according to the NCI-Frederick Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Frederick, MD). All other mouse strains were produced in-house. Animal care procedures followed NCI-Frederick Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Southern Blot Analysis of ES cells and Polymerase Chain Reaction Genotyping of BHD Knockout mice

KOD Hot DNA polymerase (Novagen, Madison, WI) was used for generating probes and routine polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping. A 5′ external probe for Southern blot analysis of targeted ES cells was generated by PCR with primers: forward, 5′ TCGACCTCGATGGAGTGATCC-3′; and reverse, 5′ -GGCAATGGCACCCATTTAAGG-3′ (GenBank NT_096135.5). A 3′ external probe was also generated by PCR with primers: forward, 5′ -CAGGCTCAAGCAGTAGTGAGACCA-3′; and reverse, 5′ -CATTCTGCTTTGGGGCATGA-3′ (GenBank NT_096135.5. ). Nonradioactive Southern blotting was performed with DIG OMNI System for PCR Probes according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). PCR genotyping was performed with three primer sets to amplify wild-type (178 bp PCR product (GenBank AL596204 ). floxed (292 bp PCR product), and deleted (392 bp PCR product) BHD alleles: P1, 5′GTTGTCTGGAGTGCTACTTAGTCAGG- 3′, which is complementary to the genomic sequence upstream of the 5′-loxP sequence; P2, 5′- CAACACCCCAGCATCCAG -3′, which is complementary to the sequence downstream of 5′-loxP; and P3, 5′CAGCTCCCTCTACCCAGACA-3′, which is complementary to the sequence downstream of 3′-loxP. For Cre genotyping, the forward (5′GCAACATTTGGGCCAGCTAAAC-3′) and reverse (5′CCGGCATCAACGTTTTCTTTTC-3′) primers (GenBank AB363405) were used for PCR amplification.

Immunoblot Analysis of Folliculin and qRT-PCR Expression Analysis of the BHD Gene

Three-week old mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation ( n=3 each genotype), their kidneys were removed, cut into small pieces, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80C for further analysis. For each mouse, one frozen kidney piece was homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, 1.0% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecylsufate [SDS], 100 nM Calyculin A, and Complete Protease Inhibitor cocktail [Roche, Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN]) with a Polytron homogenizer on ice followed by centrifugation at 16,000xg for 30 minutes. Protein concentrations of cleared supernatants were measured with BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, IL) and adjusted to 1.33 mg/mL, 4 X SDS-sample buffer was added, and samples were boiled for 5 min to produce 1 mg/mL sample lysates. A total of 20 μg of protein was loaded onto 4–20% or 4–15% SDS-PAGE gels. Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (12). Antibodies were diluted as follows: mouse monoclonal FLCN 1:1000, β- actin 1:500, Cyclin D1 1:1000, Cyclin A 1:1000, Cyclin B1 1:1000, cdc2 1:1000, CDK4 1:1000, phospho-c-Raf(Ser338) 1:1000, phospho-MEK1/2(Ser217/221) 1:1000, phospho-Erk1/2(Thr201/Tyr204) 1:1000, phosphop90RSK(Ser380) 1:1000, phospho-Akt(Thr308) 1:1000, Akt 1:1000, phosphomTOR(Ser2448) 1:1000, mTOR 1:1000, phospho-S6R(Ser240/244) 1:1000, S6R 1:1000, phospho-AMPKα 1:500. At least three independent experiments were performed with two replicates each. Secondary antibodies were diluted as follows: goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase, 1:1000; goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase, 1:1000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Antibody-protein complexes were detected using ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Total RNA was isolated from frozen kidney tissues (one sample per kidney) using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed as previously described (25). The following PCR primers to amplify β-actin and BHD exons 6 and 7 were generated by using Primer 3 software: β-actin forward: 5′-GACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGATTACTG-3′, β-actin reverse: 5′-GCTGATCCACATCTGCTGGAA-3′ (GenBank accession no. NM_007393.3 ); and BHD forward: 5′- GATGACAACTTGTGGGCGTGTC-3′, BHD reverse: 5′-CATCTGGACCAGGGTGTCCTCT -3′ (GenBank accession no. NM 146018.1). Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate using the β-actin gene as an internal control.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, goat anti-rabbit IgG, rabbit polyclonal Cyclin A, rabbit monoclonal cdc2, and rabbit polyclonal vacuolar-H+ATPase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); acetylated tubulin (Sigma, St Louis, MO); rabbit polyclonal Na-K-Cl cotransporter 2 (NKCC2) (Chemicon, Temecula, CA); rabbit polyclonal thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter (TSC, gift from Mark Knepper); lectin Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) and lectin Lotus tetragonolobus agglutinin (LTA) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); rabbit monoclonal phospho-S6R, rabbit monoclonal S6R, rabbit polyclonal phospho-AKT. rabbit polyclonal AKT; rabbit monoclonal phospho-AMPKα; rabbit polyclonal AMPKα1; rabbit monoclonal Cyclin D1; rabbit monoclonal phospho-c-Raf; rabbit polyclonal phospho-MEK1/2; rabbit polyclonal phospho-Erk1/2; rabbit polyclonal phospho-p90RSK ; rabbit polyclonal phospho-mTOR; and rabbit polyclonal mTOR (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); rabbit polyclonal actin (Biomedical Technology, Stoughton, MA); mouse monoclonal BrdU (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA); rabbit polyclonal phosphohistoneH3, (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA); rabbit polyclonal cdk4 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA); rabbit polyclonal Cyclin B1 [gift from Philipp Kaldis (26)]. FLCN-105, a rabbit polyclonal antibody against GST-folliculin and FLCN-mAb in culture medium from single clone hybridoma cell line raised against full-length GST-folliculin in the mouse were prepared as described previously (12).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Examine Kidney Function of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre Mice

Three-week-old BHDf/+/KSP-Cre and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice (n=2 for each genotype) were kept under isoflurane gas anesthesia (1–2% isoflurane in O2) at approximately 80 breaths per min in a cylindrical chamber and imaged in a clinical 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner (Philips Intera Achieva, Best, The Netherlands) using a 40-mm diameter solenoid volume receiver coil (Philips Research, Hamburg, Germany). Multislice T2-weighted Fast Spin Echo (T2W-FSE) images (TR 2823 ms [TR=timed repetition], TE 65 ms [TE=echo time], FA 90 [FA=flip angle], Matrix 352×170, FOV 60×30 mm [FOV=field of view], Slices 32, Thickness 0.5 mm, Scan Time 6:26 min) were acquired in the coronal plane with respiratory triggering to minimize motion artifacts. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced (DCE)-MRI was performed by taking a series of T1W-SPGR images (TR 20 ms, TE 3 ms, FA 24, Matrix 512×130, FOV 60×30 mm, Slices 32, Thickness 0.5 mm, Scan Time 2:43 min) in the coronal plane every 3 min for 30 min. After the first dynamic image, 50 μL of an 80 mM dilution of Gadolinium (Gd) contrast agent (Magnevist, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Wayne, NJ) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4; nominal dosage of 0.2 mmol Gd/kg mouse) along with an additional 50 μL of PBS was infused at a rate of 150 μL/min into the tail vein through a catheter using a syringe pump (BS-9000-8, Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA). Dynamic subtraction images were obtained by subtracting the pre-contrast image from each of the post-contrast image.

Phenotype Evaluation and Histopathology

BHDf/d/KSP-Cre (n=60) and control BHDf/+/KSP-Cre mice (n=70) were weighed, euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation (for P14 and P21) or decapitation (for P0, P1, and P7), and dissected. Kidneys were removed, weighed, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hrs, followed by fixation in 70% ethanol. Kidneys were then routinely processed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5-μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Stained sections were evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (DCH). To measure dried weight, dissected kidneys from BHDf/+/KSP-Cre mice (n=8) and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice (n=6) were minced into small pieces and dried by vacuum centrifugation at 50°C overnight.

Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) Analyses to Measure Kidney Function

Blood were collected into a Microvette CB300 (Sarstedt, Germany) from decapitated day 0, 2 and 7 BHDf/+/KSP-Cre and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice. Older day 14 and 21 mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and a cut was made in the right atrium. Blood was collected by pipet, transferred into a Microvette CB300 and centrifuged at 10,000xg for 5 minutes at 20 C. Serum was collected and stored at -80 for further analysis. Serum samples were placed on a Vitros BUN/Urea slide and BUN measurements were performed on a Vitros 250 instrument according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY)

Rapamycin Treatment of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre and Control BHDf/+/KSP-Cre Mice

BHDf/d/KSP-Cre and control BHDf/+/KSP-Cre mice at P7 were randomly divided into two groups for buffer(n=11) and rapamycin treatment(n=10). Rapamycin (LC Laboratories, MA) was dissolved in 100% ethanol at a stock concentration of 10 mg/mL. Rapamycin stock solution was diluted to 200 μg/mL in buffer (5%Tween-80, 5% PEG400) and injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a dose of 2 mg/kg daily. At day 21 or before if moribund ( usually day 19 or 20), mice were euthanized, kidneys were dissected, kidney/body weight ratios were measured and histopathology was performed as described above.

For survival analysis, BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice at P7 were randomly divided into two groups for buffer(n=5) and rapamycin treatment (n=4). Rapamycin (2mg/kg/day) or buffer was injected daily intraperitoneally until mice were found dead or moribund.

Renal Tubule Cell Primary Culture

One each BHDf/+/KSP-Cre and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice, euthanized at P21, were perfused with Liver Perfusion Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Liver Digest Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After perfusion, kidneys were removed using aseptic technique, minced into small pieces with razor blade, and incubated in Liver Digest Medium on a rocker at 37°C for 20–45min. Digested tissues were dissociated by gentle pipetting, washed with Hepatocyte Wash Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and incubated with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, Inc., San Diego, CA) on a rocker at 37°C for 15 min. Dissociated tissues were filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA ) twice, washed with Hepatocyte Wash Medium, resuspended in PBS/0.02% EDTA, and separated by Percol gradient centrifugation to isolate the tubule cell fraction that fractionated between the PBS and 41.9% Percoll/1X MEM layers. Isolated tubule cell fractions were washed three times with SFFD Medium [Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium:Ham’s F-12 (1:1), 10 mM Hepes, 1.1 mg/mL sodium bicarbonate, 10 nM sodium selenium] and plated on collagen-I coated dishes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA ) in 10% fetal bovin serum/SFFD medium. After 24 hr, dishes were washed twice with PBS, and medium was replaced with K1 Medium (SFFD medium with 5 μg/mL insulin, 25 ng/mL PGE1, 5 pM triiodothyronine [T3], 50 nM hydrocortisone, and 5 μg/mL apo-Transferrin). Cells were detached from culture dishes by washing with PBS/0.02% EDTA followed by incubation at 37°C for 15 min with Accutase. For cell growth assays, 1X104 cells were plated on 3.5-cm collagen-I coated dishes with K1 Medium containing 10nM rapamycin or DMSO diluent as control. Cells were detached from three dishes for each group at each time point by Accutase incubation, and subjected to counting using a hemocytometer with two replicates.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence Analysis of Cell Cycle Markers and Akt-mTOR and Erk-MEK 1/2 Pathway Signaling

Five-μm-thick sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were placed on slides for immunohistochemistry (IHC). Phospho-histone H3 staining was performed using the Ventana automated IHC system (Ventana HX system Dyscovery/20:750-DSC, Ventana Medical systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ). Antigen retrieval was performed by microwave-heated incubation in citrate buffer for 20 min, followed by incubation with rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-histone H3 (1:5000) overnight at 4°C. For immunofluorescence staining, the renal capsules were removed from the kidneys of P0, P2, and P7 mice (n=3 at each age) in ice-cold PBS, and kidneys were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1.5 hr at 4°C, followed by sucrose replacement (5–20% sucrose/0.1M sodium phosphate, pH 7.2). Kidneys were then embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound, frozen on a metal block in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C. Euthanized P14 and P21 mice (n=3 at each age) were perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Kidneys were removed and further fixed in 4% PFA for 1 hour at 4°C, followed by sucrose replacement. They were then embedded in OCT compound and frozen as above. Five-μm-thick frozen sections were prepared and mounted onto slides (n= 20 per mouse), fixed in methanol/acetone (1:1) at –20°C for 10 min, and blocked with 10% normal goat serum. They were then rinsed with PBS, quenched in 0.5M ammonium chloride/0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and incubated with the primary antibody in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20, 3% goat serum, and 0.1% (w/v) BSA at 4°C overnight. Antibody dilutions were as followed, DBA 1:400, NKCC2 1:1000, LTA 1:400, TSC 1:400, vacuolar H+-ATPase 1:200, Cyclin D1 1:50, P-Erk1/2 1:100, P-Akt 1:100, P-mTOR 1:100, P-S6R 1:100. After three 10 min washes with TBST[10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20 ][TBST=Tris buffered saline with Tween], slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500 dilution) and/or Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500 dilution) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After another three 10-min washes with TBST, slides were sealed with mounting medium containing 4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1x, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and viewed with a confocal microscope system (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Renal tumor tissue (n=16; 10 tumors from patient #1, 3 tumors from patient #2, 2 tumors from patient #3, 1 tumor from patient #4) and normal kidney parenchyma (n=4; 2 normal tissues from patient #2 and one each normal tissues from patients #3 and #4) samples from BHD patients surgically treated at the Urologic Oncology Branch, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (with patient permission under a National Institutes of Health IRB approved protocol #97-C-0147) were frozen in OCT compound without fixation. Frozen sections were fixed in methanol/acetone (1:1) at -20°C for 10 min followed by staining with phospho-mTOR antibody using the procedure above.

For cell proliferation measurements, BrdU (100 μg/g body wt) was injected i.p. into P14 BHDf/+/KSP-Cre (n=2) and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre (n=2) mice 2 hr before the mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation Kidneys were fixed with 10% formalin for 24 hrs, followed by 70% ethanol fixation. Five-μm-thick sections (n=4) were immunostained with mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody at 1:500 dilution after trypsin pretreatment for 3 hours at 37 C using the ARK kit (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) . The number of BrdU stained cells per 1000 cells in each field was counted in five randomly selected fields. βgalactosidase activity was measured in situ in frozen sections (n=2 per mouse) prepared as described above, using standard staining techniques. Tissue sections were counterstained with nuclear fast red (Sigma, St Louis, MO).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with both parametric and nonparametric methods and graphical techniques. Kidney weight data were analyzed with Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test, Student’s t test, and Welch’s t test to account for unequal within-group variances. Cell count longitudinal growth data were analyzed with regression analysis, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), following logarithmic (base 10) transformation of the data to satisfy homogeneity of variance assumptions underlying the models. Where appropriate, results are reported or plotted with 95% confidence intervals. Mouse survival time was defined as the time from birth until death or moribund. Survival data were estimated and plotted with the Kaplan-Meier method, differences between survival groups were assessed with the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed with S-Plus (version 7.0, Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA), and SAS (version 9.1, Cary, NC). All statistical tests were two-sided. Probability values (P) less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

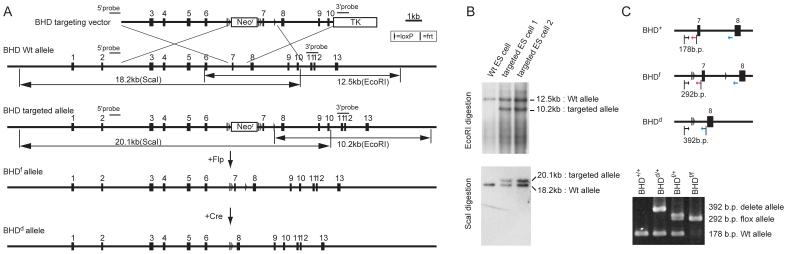

We determined that homozygous BHD deletion is embryonic lethal in the mouse, because no BHDd/d offspring were produced from intercrosses of BHDd/+ mice (data not shown). To circumvent embryonic lethality, we developed a conditional BHD-knockout mouse. The targeting vector, with loxP sites flanking exon 7 of the BHD gene, was generated by recombineering methodology ((27); Fig. 1, A). Correctly-targeted ES cell clones were selected by Southern blot screening (Fig. 1, B) and used to generate chimeric mice that were then backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for germline transmission of the BHD floxed (f) allele.

Fig. 1. Generation of conditional BHD knockout mice.

A) Targeting strategy. Birt-Hogg-Dube’gene (BHD) targeting vector was constructed by recombineering methodology using homologous recombination (27). A neomycin resistance (Neor) cassette flanked by Frt (bar) and loxP (triangle) sequences was inserted into intron 6 for positive selection, and the thymidine kinase gene was included for negative selection. A second loxP sequence was inserted into intron 7. Correctly-targeted embryonic stem (ES) cells were identified by Southern blot analysis and injected into blastocysts to produce chimeras. Backcrossing to C57BL/6 mice produced heterozygous F1 offspring with germline transmission of the BHD floxed (f)-Neo allele. The Neo cassette flanked by Frt sites was excised in vivo by crossing with mice expressing the Flp recombinase transgene under the ubiquitous β-actin promoter. To produce the BHD deleted (d) allele, BHD f/+ mice were crossed with mice expressing the Cre recombinase transgene under the ubiquitous β-actin promoter (24). Deletion of exon 7 resulted in a frame shift and premature termination codon in exon 8, which caused mRNA degradation by the nonsense-mediated decay mRNA surveillance system (43). B) The targeted ES cells were screened by Southern blotting of EcoRI and ScaI digested DNA using two different external probes located outside the targeting sequence as shown in (A). C) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based genotyping was performed using DNA extracted from mouse tails for routine monitoring of inheritance in offspring. Locations of PCR primers are indicated by arrows.

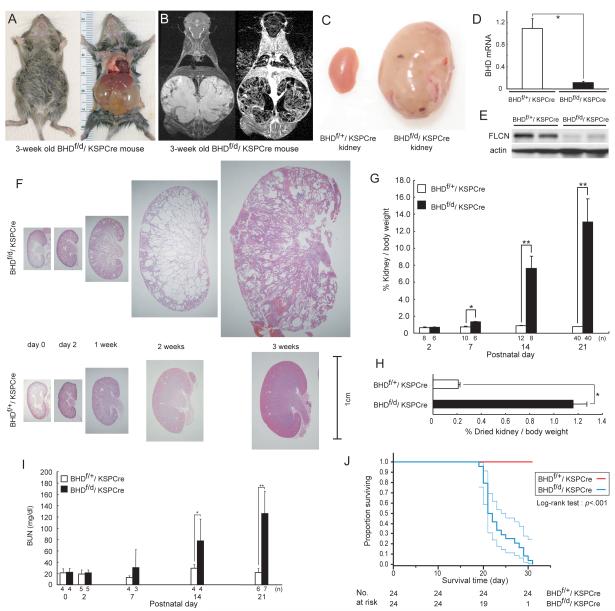

To target BHD deletion specifically in the kidney, we used Cre transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the KSP-cadherin (cadherin 16) promoter, which drives Cre expression exclusively in kidney tubule epithelial cells and the developing genitourinary tract (22). BHDd/+/KSP-Cre mice were generated by crossing BHDd/+ mice with KSP-Cre mice. Conditionally-deleted BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice and BHD f/+/KSP-Cre littermate controls were produced from BHDf/f and BHDd/+/KSP-Cre parents. Mice with kidney-specific inactivation of BHD appeared normal at birth but showed distended abdomens by 2 weeks, which were very pronounced at the time of death, at approximately 3 weeks of age. At autopsy, the enlarged kidneys were seen to completely fill the abdominal cavity, and this phenotype was 100% penetrant in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice (Fig. 2, A). Magnetic resonance imaging with Gadolinium enhancement revealed highly cystic features and a fine reticular pattern of interstitial tissue containing numerous blood vessels in the BHD-inactivated kidneys (Fig. 2, B), which were not seen in control kidneys (data not shown). BHD mRNA expression levels measured by qRT-PCR in BHD-inactivated kidneys (Fig. 2, D) were statistically significantly lower than that of control kidneys (BHDf/+/KSP-Cre versus BHDf/d/KSP-Cre: mean=1.09 versus 0.11, difference = 0.98, 95% CI=0.80 to1.16; P<.001), showing efficient Cre-mediated deletion of the floxed BHD sequences and probable nonsense-mediated decay of the mutant BHD mRNA. In support of these results, folliculin protein levels in BHD-inactivated kidneys (Fig. 2, E) were very low when compared with littermate controls.

Fig. 2. Phenotypic features of BHD-targeted deletion in the kidney.

A) Gross picture of a 3-week old BHDf/d/KSP (cadherin 16 kidney-specific promoter)-Cre mouse shows a distended abdomen (left panel). The large cystic kidneys fill the abdominal cavity (right panel) and are found in 100% of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice. B) T2 weighted coronal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image (left) and corresponding Gadolinium-enhanced T1 weighted dynamic subtraction MRI image (right) of a 3-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse show enlarged cystic kidneys with reticular interstitium and delayed excretion of contrast medium. C) Comparison of gross features of 3-week-old control BHDf/+/KSPCre and knockout BHDf/d/ KSP-Cre kidneys reveals a normal phenotype in control mice. Knockout BHDf/d/ KSP-Cre kidneys show symmetric enlargement without focal masses. One representative image of 40 mice for each genotype is shown. D) BHD mRNA expression in kidneys of 3-week-old mice was quantified by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using exon 6 and 7 amplification. Three mice of each genotype were analyzed. Data are presented as means and 95% confidence intervals from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (Welch’s t test:*P<.001). E) Folliculin (FLCN) expression in control and knockout kidneys was estimated by immunoblotting. One representative of three independent experiments performed in two mice is shown. F) Comparison of BHD control and knockout kidney histology (hematoxylin and eosin staining) at different ages shows no obvious differences at days 0 and 2. At 1 week, BHD-knockout mice have enlarged kidneys with dilated collecting ducts and a few dilated cortical tubules. By 2 weeks of age, most collecting ducts in the medulla are markedly dilated. The entire BHD-knockout kidney is diffusely filled with cystic collecting ducts and tubules at 3 weeks of age, and at this point anatomic distinction between cortex and medulla is lost. One representative of at least three mice at each age is shown. G) Relative ratio of kidney to body weight (BW;100 X kidney weight/[BW—kidney weight]) was calculated at different ages. The mean kidney weight of the BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice at 3 weeks of age was 13.1% of body weight compared with 0.77% for control mice (n=40 for each group, difference=12.3%, 95% CI=11.1% to 13.6%; Welch’s t test:P<.001). Data are represented as means and 95% confidence intervals (*P =.002, ** P <.001). H) Relative ratio of dried kidney to body weight (100 X dried kidney weight/[BW—wet kidney weight]) of 3-week-old mice was calculated. Even with loss of cystic fluid, the dry weight of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre kidneys was statistically significantly greater than control kidneys (mean=1.16%, n=8 versus mean=0.21%, n=10, difference=0.95%, 95% CI=0.84% to 1.06%; Welch’s t test: * P<.001). Data are represented as means and 95% confidence intervals. I) BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice die of renal failure. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were determined at different ages. Statistically significant elevation of BUN levels was observed at 2 weeks of age in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice compared with littermate controls (n=4 for each group, mean=77.7 mg/dL versus mean=29.2mg/dL, difference=48.5mg/dL, 95% CI=18.6 to 78.3 , Welch’s t test:*P=.03). Similar statistically significant differences were seen between 3-week old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice (n=7) and control littermates (n=6) (mean=126.1 mg/dL versus mean=21.8 mg/dL, difference=104.3 mg/dL, 95% CI=64.9 to 143.9 , Welch’s t test:**P=.0012). Data are represented as means and 95% confidence intervals. J) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis shows a statistically significant difference between control and BHD knockout mice (log-rank test, P<.001). Median survival time of BHD knockout mice is 21.5 days (n=24).

Macroscopic images of H&E stained kidneys from BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice and control BHDf/+/KSP-Cre littermates revealed no differences at birth or postnatal day (P)2. By 1 week, BHD-inactivated kidneys began to enlarge due to dilatation of collecting ducts and some cortical tubules. At 2 weeks, lumens of ducts and tubules were cystic, causing further gross enlargement of the kidneys. At 3 weeks, the kidneys were markedly cystic, the anatomic distinction between cortex and medulla was disrupted, and regions of pyramidal infarctions were observed (Fig. 2, F). We calculated the relative ratio of kidney to body weight [(BW)—kidney weight] in BHD-inactivated mice and control littermates. No statistically significant differences were seen at P2. However, the BHDf/d/KSP-Cre kidney/body weight ratio increased dramatically between P7 and P21 and was statistically significantly greater than littermate controls (P21, BHDf/+/KSP-Cre versus P21, BHDf/d/KSP-Cre: mean=0.77% versus 13.1%, difference=12.3%, 95% CI=11.1 to 13.6%; Fig. 2C, 2G). To adjust for the weight of the fluid in the dilated tubules and ducts, kidneys from 3-week-old mice were completely dehydrated and reweighed (Fig. 2, H). The dried kidney/body weight ratio was also greater in BHD knockout mice than in control littermates (BHDf/+/KSP-Cre versus BHDf/d/KSP-Cre: mean=0.21% versus 1.16%, difference=0.95%, 95% CI=0.84 to 1.06%; P<.001 ).

To evaluate renal function in BHD-inactivated kidneys, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were measured at different ages and compared with those of littermate controls (Fig. 2, I). BUN levels compared well with the kidney/body weight ratios, showing no differences at birth or P2 and only slight changes at 1 week, and statistically significant elevation at 2 weeks (P=.03) and 3 weeks (P=.0012) in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice compared with littermate controls. Renal failure in 3-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice may have resulted from the compression of glomeruli caused by the high density of markedly dilated tubules. Median survival age of the BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice was 21.5 days (n=24; Fig. 2, J), with 100% of BHDf/+/KSP-Cre littermate controls (n=24) remaining alive during this time (P<.001).

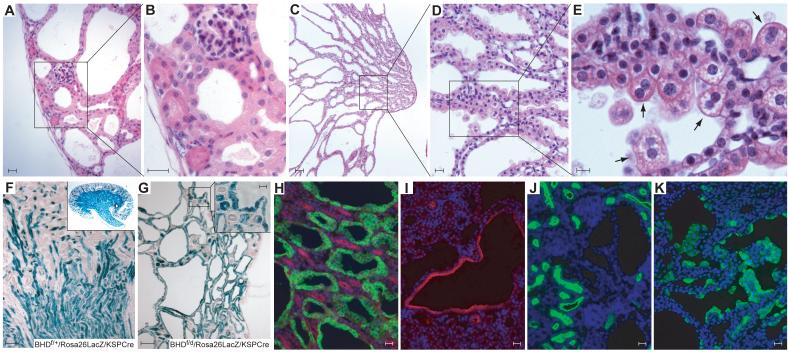

Histologic analysis of kidneys from 3-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice (Fig. 3, A—E) revealed marked enlargement due to dilated/cystic tubules and ducts extending from the renal capsule to the tip of the renal papilla, with the largest luminal diametersin the outer medulla. Most of the cells lining the dilated tubules and ducts were hypertrophic with enlarged cytoplasm and nuclei, and many hyperplastic cells were noted. The subcapsular region of the distorted cortex contained dilated distal convoluted tubules, interspersed morphologically normal proximal tubules, and mildly compressed glomeruli (Fig. 3, A and B). In the medulla and extending into the papilla, the collecting ducts were severely cystic (Fig. 3, C and D). We noted larger hypertrophic cells, particularly in the medulla, with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and well-defined cell borders that frequently protruded into the cystic lumen. The centrally located, round nuclei varied in size from normal with stippled chromatin and one or more inconspicuous nucleolus to twice-normal size with more euchromatin and a more prominent single nucleolus. An occasional binucleated cell was noted (Fig. 3, E). These “oncocytic-like” cells had some of the features of cells in regions of renal “oncocytosis” found in apparently normal renal parenchyma of BHD patients (8). Thin loops of Henle were present in the medulla and showed minimal dilatation.

Fig.3. Histology and immunostaining of kidneys of BHD knockout mice.

A–E) Histology of hematoxylin and eosin stained kidney from a 3-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse. A) The subcapsular region of the kidney shows dilated distal tubules, mildly compressed glomeruli and relatively normal proximal tubules. One representative image of ten sections is shown. B) Higher magnification of (A). Bowman’s space is minimal and glomerular tufts are mildly compressed. Morphologically normal proximal tubules are surrounded by dilated distal tubules lined by hypertrophic cells with enlarged eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and enlarged nuclei. C) Collecting ducts in the medulla are severely dilated. D-E) Higher magnification of medulla. Note hypertrophic cells with enlarged eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm that protrude into the lumen and an occasional binucleated cell (arrow). F) To confirm the Cre expression pattern in the kidney, BHDf/f/Rosa26lacZ mice were generated and crossed with BHDd/+/KSP-Cre mice. X-Gal staining of a BHDf/+/Rosa26lacZ/KSP-Cre mouse kidney at 3 weeks of age shows strong staining in the medulla and scattered staining pattern in the cortex. G) All dilated tubules of 3-week-old BHDf/d/Rosa26lacZ/KSP-Cre mouse kidneys show strong X-Gal staining. Morphologically normal proximal tubules also show mosaic staining (insert). H) Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA; green) and Na-K-Cl cotransporter 2 (NKCC2; red) staining in 1-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse kidneys. Dilated tubules are DBA (collecting duct marker) positive. Loops of Henle, which are NKCC2 positive, are morphologically normal. I) Dilated tubules in the cortex are thiazide-sensitive Na-Clcotransporter (TSC; red) positive, a marker of distal tubule. J) Lotus tetragonolobus agglutinin (LTA; green) staining of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse kidneys identifies apparently normal proximal tubules but does not stain dilated tubules. K) Markedly hypertrophic cells lining the dilated ducts of 2-week-old BHD knockout mouse kidneys are stained by the intercalated cell marker, vacuolar H+-ATPase (green). Scale bar=20 μm for A,B,D,H,I,J,K; 10 μm for E; 100 μm for C,F,G.

To determine the location of KSP-driven Cre expression, we generated BHDf/d/Rosa26lacZ/KSP-Cre indicator offspring. KSP-driven Cre expression will delete a neo expression cassette flanked by loxP sites upstream of the lacZ gene, thereby permitting β-galactosidase expression and its detection by 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl -D-galactoside (X-Gal) staining in tissue sections. X-Gal staining confirmed KSP-driven Cre expression in all cells lining the cystic tubules and ducts (Fig. 3, G). KSP-driven Cre was also expressed in some proximal tubules that were morphologically normal (inset, Fig. 3, G).

To classify cystic structures, immunohistochemical analyses were performed on sections from 1-week old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre kidney sections using Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA, collecting duct marker; (28)), Na-K-Cl cotransporter 2 (NKCC2, loop of Henle marker; (29)), Lotus tetragonolobus agglutinin (LTA, proximal tubule marker; (30)) and thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl-cotransporter (TSC, distal tubule marker; (31)) antibodies. Staining patterns in BHD-inactivated kidneys confirmed the histologic findings that the distal tubules and collecting ducts were dilated (Fig. 3, H and I), whereas proximal tubules and loops of Henle were relatively normal in appearance (Fig. 3, H and J). Chromophobe renal carcinoma, oncocytoma, and oncocytic hybrid tumors are the most common renal tumors found in BHD patients, and evidence suggests that they arise from intercalated cells (32-33). Interestingly, when immunofluorescence staining for the intercalated cell marker vacuolar-H+-ATPase (34) was performed on 3-week-old BHD-inactivated kidneys, strong staining was observed in the numerous hypertrophic cells with oncocytic-like features (8), which lined the dilated ducts (Fig. 3, K).

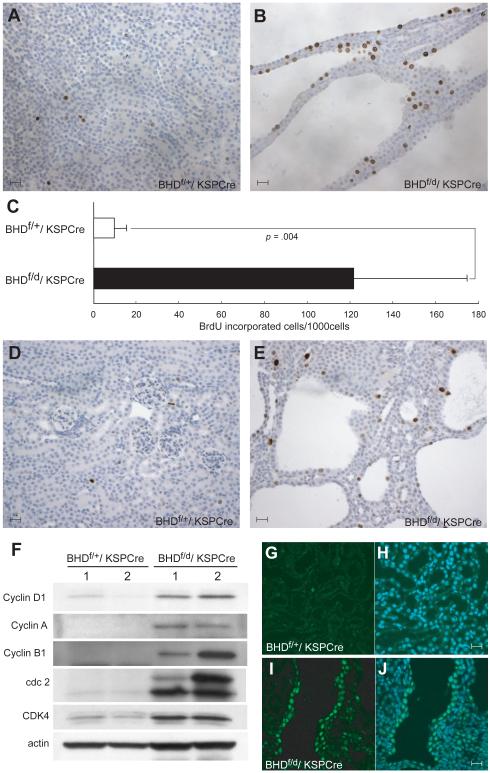

The enlarged kidneys and heavier dried weights suggested that cells in the BHD-inactivated kidneys were hyperproliferating. To evaluate cell proliferation, BrdU incorporation into mouse kidneys was measured by immunostaining. BrdU incorporation was statistically significantly greater in kidney cells from BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice than BHDf/+/KSP-Cre mice (mean=121.8 per 1000 cells versus 9.6 per 1000 cells, difference=112.2, 95% CI=59.3 to 165.0; P=.004; Fig. 4, A—C). To evaluate proliferating cells in the G2/M phase of the cell-cycle, phospho-histone H3 immunostaining was performed on kidney sections. More phospho-histone H3-stained cells were observed in BHD-inactivated kidneys than in control littermates (Fig. 4, D and E). Expression of cell cycle promoting proteins was analyzed in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre knockout and littermate control kidneys (Fig. 4, F). Expression of cyclin D1, CyclinA, CyclinB1, cdk4, and cdc2 was higher in BHD-inactivated kidneys than in control kidneys, indicating that cells were undergoing rapid proliferation. Cyclin D1 immunohistochemistry revealed strong nuclear staining in dilated tubules of BHD-inactivated kidneys (Fig. 4, I and J) but not control kidneys (Fig. 4, G and H), supporting the immunoblotting data that indicated cells lining the dilated tubules were actively proliferating.

Fig. 4. Evidence of hyperproliferating cells in the kidney of BHDf/d/ KSP-Cre mice.

5′-Bromo-2′-deoxyouridine (BrdU) (100 μg/g body wt) was injected intraperitoneally at P14 into BHDf/+/KSP-Cre and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice 2 hr before euthanization. A) BrdU staining in BHDf/+/KSP-Cre mouse kidney. B) BrdU staining in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse kidney. C) Greater than 10-fold more BrdU incorporation was seen in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse kidneys compared with BHDf/+/KSP-Cre mouse kidneys (n=5 for each group, mean=121.8 per 1000 cells versus 9.6 per 1000 cells, difference=112.2, 95% CI=59.3 to 165.0; Welch’s t test:P=.004). 1000 cells per field were counted in five randomly selected fields from two mice for each group. Data are represented as means and 95% confidence intervals. D) Phospho-histone H3 staining detects few G2/M phase cells in 3-week-old BHDf/+/KSP-Cre kidney. E) Phospho-histone H3 staining in 3-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse kidney shows more G2/M phase cells. F) Immunoblotting analysis of proteins extracted from kidneys of 3-week-old BHDf/+/KSP-Cre and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice. Cell cycle promoting proteins are highly expressed in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse kidneys. Data represent typical results for two mice of each genotype from at least three independent experiments. G) Cyclin D1 staining (green) in the kidney of a 2-week-old BHDf/+/ KSP-Cre mouse is weak. H) Merged image of Cyclin D1 with 4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear staining (blue). I) Nuclear Cyclin D1 staining (green) is seen in cells lining the dilated tubules in the kidney of a 2-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse. J) Merged image of Cyclin D1 with DAPI nuclear (blue) staining. Scale bar=20 μm.

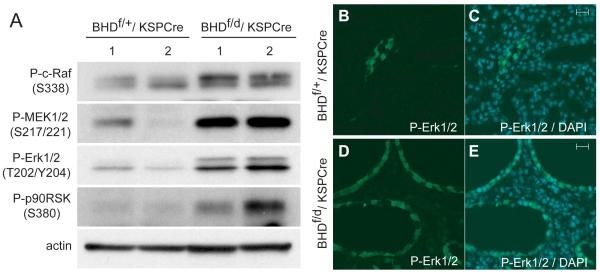

To elucidate which signaling pathways were activated by BHD inactivation, protein expression levels of several key molecules in pathways involved in cell growth and proliferation were evaluated by immunoblotting (Fig. 5, A). Phospho-c-Raf (Ser338) levels were elevated in 3-week-old BHDf/d/KSP-Cre kidney lysates compared with controls, suggesting that Raf was activated. Consistent with these data, MEK1/2 and Erk1/2, downstream effectors of Raf signaling, and p90RSK, a downstream effector of Erk1/2, were also highly phosphorylated in BHD-inactivated kidneys. Immunofluorescence staining of phospho-Erk1/2 in kidney tissue revealed strong specific staining of the dilated tubules in BHD-inactivated kidneys (Fig. 5, D and E), but minimal restricted staining in littermate control tubules (Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 5. Activation of Raf-MEK-Erk1/2 signaling pathways in kidneys of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice.

A) Immunoblotting analysis of proteins extracted from the kidneys of 2-week-old BHDf/+/KSP-Cre and BHDf/d/ KSP-Cre mice. BHD knockout kidneys show elevated levels of phospho-c-Raf (Ser338), phospho-mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (P-MEK) 1/2 (Ser217/221), and phospho- extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (P-Erk)1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), resulting in more phosphorylated p90RSK on Ser380, a downstream effector of Erk. Data represent typical results for two mice of each genotype from at least three independent experiments. B) P-Erk immunofluorescence staining of control mouse kidneys was minimal. C) Merged image of P-Erk and 4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear staining in the control kidney. D) All dilated tubules in BHD knockout kidneys show phospho-Erk staining. E) Merged image of P-Erk and DAPI nuclear staining in the kidney of a BHD knockout mouse. Scale bar=20 μm.

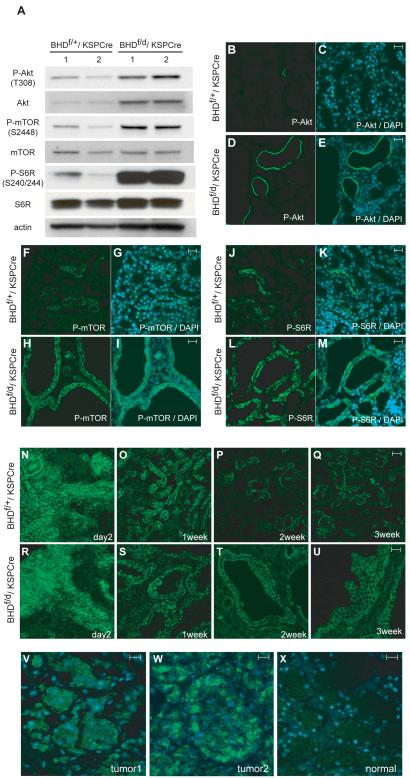

Another major pathway that is frequently activated in cancer, the PI3K-AktmTOR pathway (35-36), was evaluated by immunoblotting (Fig. 6, A). Levels of phospho-Akt on Thr308 and total Akt were elevated in BHD-inactivated kidneys compared with controls. The mTOR phosphorylation site at Ser2448 was also highly phosphorylated in BHD-inactivated kidneys, although total mTOR expression levels were the same for BHD-inactivated and control lysates, consistent with activation of mTOR signaling in BHD-inactivated kidneys. Phosphorylation of a downstream effector of mTOR, S6 ribosomal protein (S6R), on Ser240/244, was also elevated in BHD-inactivated kidneys. Phospho-Akt (Thr308) immunofluorescence staining revealed membrane staining in some dilated tubules of BHD-inactivated kidneys (Fig. 6, D and E), but only restricted staining in 2-week-old control mouse kidneys (Fig. 6, B and C). Phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) staining was seen in all the cells lining the dilated tubules (Fig. 6, H and I), whereas phospho-S6R (Ser234/235) staining was seen in some cells in the dilated tubules (Fig. 6, L and M). Restricted immunostaining of both of these proteins was detected in control kidneys (Fig. 6, F,G,J,K).

Fig. 6. Activation of Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in kidneys of BHDf/d,KSP-Cre mice.

A) Immunoblotting analysis of Akt, phosphorylated (P)-Akt, ribosomal protein S6R, P-S6R (Ser240/244), a measure of activated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), mTOR, and P-mTOR in proteins extracted from the kidneys of 3-week-old BHDf/+/KSP-Cre and BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice. Actin was used as a control for protein loading and transfer. Data represent typical results for two mice of each genotype from at least three independent experiments. B-M) Immunofluorescence staining of P-Akt (Thr308), P-mTOR, and P-6SR (235/236) in kidneys of 2-week-old BHD control and knockout mice. Phospho-Akt staining in the control kidney is very restricted (B, C). The epithelial cells lining the dilated tubules show membrane staining of P-Akt (Thr308) in BHD knockout mouse kidneys (D, E). Note that not all of the dilated tubules were stained. P-mTOR at Ser2448 is positive in a small population of tubule cells in control mouse kidneys (F, G). All dilated tubules in BHD knockout mouse kidneys show mTOR phosphorylation on Ser2448 (H, I). P-S6R (Ser235/236) staining in control mouse kidneys shows restricted staining (J, K). P-S6R (Ser235/236) staining in BHD knockout mouse kidneys indicates that mTOR is activated in dilated tubules. 4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear staining (blue) is shown (L, M). N-U) P-mTOR staining of kidneys of control and BHD knockout mice at different ages. P-mTOR (Ser 2448) staining in control (N) and BHD knockout kidneys (R) shows identical strong staining patterns in the developing cortex at P2. Fewer tubule cells in kidneys of 1-week-old control mice retain P-mTOR (Ser2448) staining (O). Tubules in BHD knockout mouse kidneys that show dilatation display P-mTOR (Ser2448) staining at 1 week (S). At 2 and 3 weeks of age, there are fewer P-mTOR–positive tubules in control mouse kidneys than in BHD knockout mouse kidneys (P, Q). All dilated tubules in kidneys of BHD knockout mice at 2 and 3 weeks of age retain P-mTOR (Ser2448) staining (T, U). V-X) Renal tumors from BHD patients (representative results from 16 immunostained BHD tumor samples) also show P-mTOR (Ser2448) staining. (V, W) P-mTOR (Ser2448) staining is seen in the cytoplasm of human BHD patient renal tumor cells. (X) Conversely, very little staining is seen in the normal kidney tissue that is adjacent to tumor 1 (representative results from four immunostained normal kidney samples). Scale bar=20 μm.

To determine the biochemical consequences of BHD inactivation on postnatal kidney development, phosphorylated mTOR was evaluated at ages from P2 to P21. The staining was identical in control and BHD-inactivated kidneys at P2 with strong staining in the developing cortex (Fig. 6, N and R). Phospho-mTOR staining in normal tubules was dramatically decreased after 1 week in control kidneys (Fig. 6, O—Q). However, phospho-mTOR staining was retained in abnormal dilated tubules from BHD-inactivated kidneys during postnatal development (Fig. 6, S—U). We next asked whether the AktmTOR pathway was activated in renal tumors from BHD patients by performing phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) immunohistochemistry. Weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining of phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) was observed in 1 chromophobe and 13 of 15 oncocytic hybrid tumors from four BHD patients with germline mutations (representative images in Fig. 6, V and W), whereas almost no signal was detected in four normal kidney samples from one non-BHD and two BHD patients (Fig. 6, X). These results are consistent with another report (37), which describes weak phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) staining in sporadic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and oncocytoma.

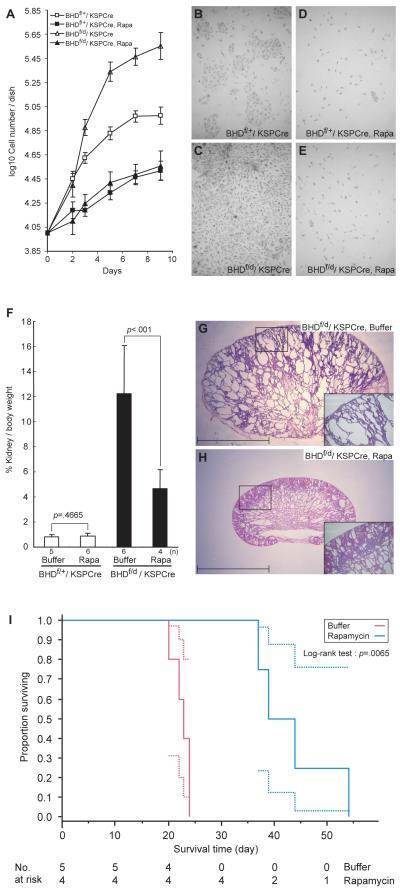

One important question that we sought to clarify was whether or not increased cell proliferation in BHD-targeted kidneys was through a cell autonomous mechanism or dependent upon environment (i.e., stroma). To address this question, we performed primary cell culture of isolated tubule cells from BHD-inactivated and control kidneys. BHD- targeted kidney cells grew faster in culture than control kidney cells (P<.001). Addition of 10 nM rapamycin to the culture medium suppressed the rapid growth of BHD-inactivated cells and control cells to the same base level (Fig. 7, A–E). The percentage reduction in the growth due to rapamycin treatment by day 9 was twice as large in the BHD-inactivated kidney cells as in the control kidney cells (17.7% versus 9.1%, difference -8.6%, 95% CI = 5.1 to 12.0; ANCOVA:P<.001.

Fig.7. Effect of rapamycin, inhibitor of mTOR signaling, on BHD knockout kidney tubule cell proliferation in vivo and in vitro and on survival of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice.

A) Tubule cells from the kidneys of 3-week-old control (n=1) and BHD-knockout (n=1) mice were isolated, cultured in the presence and absence of rapamycin (10 nM), and counted to evaluate cell proliferation. B-E) Representative images of untreated and treated cells from control mice (B and D) and those of BHD knockout mice (C and E) taken at day 9 are shown. Data are represented as means and 95% confidence intervals. F) Rapamycin (2 mg/kg/day) or buffer was injected into BHDf/d/KSP-Cre and BHDf/+/KSP-Cre mice (BHDf/+: buffer, n=5, rapamycin, n=6; BHDf/d: buffer, n=6, rapamycin, n=4). Mice were dissected at 3 weeks, and relative kidney/body weight ratios (100 X kidney weight / [body weight–kidney weight]) were calculated. Relative kidney/body weight ratios in BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice (buffer versus rapamycin: mean=12.2% versus 4.6%, difference=7.6%, 95% CI=5.2% to 10.00%, Welch’s t test:P<.001), and relative kidney/body weight ratios of BHDf/+/KSP-Cre control mice (buffer versus rapamycin: mean=0.82% versus 0.88%, difference=0.06%, 95% CI= – 0.11% to 0.24%; Student’s t test:P= .47). Data are represented as means and 95% confidence intervals. G) Buffer-treated BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mouse kidneys have numerous cystic tubules and ducts. Insert indicates higher magnification of area in the square. H) Rapamycin-treated 3-week-old BHD knockout mouse kidneys show fewer, less dilated tubules. Insert indicates higher magnification of area in the square. Scale bar=5 mm. I) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis shows a statistically significant difference between buffer- and rapamycin-treated BHD knockout mice. Median survival time of buffer-treated BHDf/d/ KSP-Cre mice is 23 days (n=5) and rapamycin-treated BHDf/d/ KSP-Cre mice is 41.5 days, (n=4). Log-rank test (two-sided), P=.0065.

We also tested whether rapamycin could reverse the cystic kidney phenotype by injecting buffer or rapamycin (2mg/kg) daily into BHDf/d/KSP-Cre and control mice beginning at P7. Mice were dissected at P21 or before P21, if moribund, and the ratio of kidney to body weight was calculated (Fig. 7, F). Rapamycin treatment did not change the kidney/body weight ratios of control littermates (buffer versus rapamycin: mean=0.82% versus 0.88%, difference=0.06%, 95% CI=–0.11 to 0.24; P=.47), but it reduced the relative kidney/body weight ratio of BHD-knockout mice at P21 (buffer versus rapamycin: mean=12.2% versus 4.64%, difference=7.6%, 95% CI=5.2 to 10.0, P<.001 ). Buffer-treated BHD-inactivated kidneys showed cystic tubules and ducts, characteristic of the BHDf/d/KSP-Cre kidney phenotype, with complete disruption of normal anatomic structures (Fig. 7, G). However, rapamycin-treated BHD-inactivated kidneys displayed only mild dilatation of tubules and ducts with retention of some cortical structure at 3 weeks of age (Fig. 7, H).

To examine the effect of rapamycin on survival, BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice were divided randomly into two groups (n = 4 and n = 5) and injected with buffer or rapamycin(2mg/kg/day) daily from P7 until mice were found moribund or died. Rapamycin treatment statistically significantly extended the survival period of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre mice (buffer versus rapamycin: median=23 days versus 41.5 days; P=.0065), although these mice eventually died from renal failure.

DISCUSSION

In this report we describe the development of the first conditional BHD-knockout mouse model in which inactivation of the BHD gene is targeted to kidney epithelial cells. Mice with kidney-specific homozygous inactivation of BHD exhibited rapid kidney cell proliferation and progressive dilatation of collecting ducts and distal tubules during the first 3 weeks of life with 100% penetrance, which led to severe kidney dysfunction and death. Increased expression of cell cycle proteins and activation of Raf-Erk1/2 and Akt-mTOR pathways was observed in the BHD-knockout kidneys. Heterozygous BHD-targeted littermates displayed a normal phenotype during the study period, suggesting that loss of both BHD alleles must occur for this dramatic phenotype to develop in the mice. We found that treatment with the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, reduced kidney size and the extent of tubule dilatation, and prolonged survival time of the BHD-knockout mice.

We have targeted BHD inactivation to the kidney, mainly in the distal nephron where cadherin 16 is highly expressed (22). However, X-gal staining of kidneys from mice with the BHDf/d/Rosa26LacZ/KSP-Cre genotype showed mosaic Cre expression in the proximal tubules as well, although proximal tubules were normal histologically. Only distal tubules and collecting ducts were dilated and cystic in the BHD-knockout mice, suggesting that BHD inactivation produces a phenotype specifically in the kidney cells that make up the distal nephron, consistent with the fact that human BHD-associated renal tumors, predominantly chromophobe renal carcinomas and renal oncocytic hybrid tumors, arise from the distal nephron (8). Furthermore, our immunofluorescence staining with vacuolar-H+-ATPase suggests that in BHD knockout mice, intercalated cells of the collecting duct may give rise to the hyperplastic cells with oncocytic-like morphology in the dilated tubules, consistent with several reports suggesting that intercalated cells may be the origin of chromophobe renal cancer and oncocytoma (32-33). However, although BHD patients have an increased risk for renal cancer, our BHD conditional knockout mouse model developed no signs of renal neoplasia before renal failure at 3 weeks, suggesting that additional genetic or epigenetic events are required for progression to neoplasia.

The Raf-MEK-Erk pathway, which is activated in many cancers and regulates cell proliferation (38), was activated in the BHD-knockout kidneys, consistent with the increased cyclin D1 expression and cell proliferation we observed. Another important regulator of cell growth and protein synthesis, the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway (13), was also activated leading us to hypothesize that a common upstream effector of Raf-MEKErk and PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathways (i.e., receptor tyrosine kinase) may be activated by loss of BHD tumor suppressor function, resulting in cell growth and proliferation within the BHD-null kidney cell. The rapid growth rate of BHDf/d/KSP-Cre tubule cells in primary culture compared with control tubule cells suggests that this cell proliferation is caused by a cell autonomous mechanism. This mechanism is supported by the fact that BHD deletion by KSP (cadherin 16)-driven Cre recombinase occurred only in kidney epithelial cells, not in stroma, as confirmed by β-galactosidase staining patterns in BHDf/d/RosaLacZ/KSP-Cre mice.

As expected in the developing neonatal kidney of control littermates, phosphomTOR (Ser2448) staining of kidney tubules was evident at birth but gradually declined during the first 3 weeks of life. However, in BHD-knockout mice, inappropriate phospho-mTOR staining was consistently seen in dilated tubules from birth until moribund at 3 weeks of age, suggesting that BHD is necessary for proper regulation of cell growth and proliferation through Akt-mTOR signaling during postnatal kidney development. Our hypothesis that inappropriate Akt-mTOR signaling may have a major role in the enlarged cystic kidney phenotype is supported by the fact that rapamycin treatment dramatically reduced the kidney size and extent of tubule/duct dilatation, caused complete loss of phospho-S6R staining in tubule cells (data not shown), and extended survival of BHD-knockout mice. In a rat model of autosomal polycystic kidney disease, rapamycin treatment reduced both the size of the polycystic kidneys and cystic volume and completely restored kidney function through decrease in tubular cell proliferation, which is thought to be the first step in cyst formation (39). Our study also supports tubule cell hyperproliferation as an initiating event of cystic change and rapamycin inhibition of uncontrolled tubule cell growth both in vitro and in vivo.

However, because rapamycin did not completely reverse the cystic kidney phenotype and the BHD-knockout mice eventually died, other signaling pathways (i.e., Raf/Erk, Akt) may contribute to the phenotype caused by loss of folliculin function. Because mTOR inhibition by rapamycin reduces negative feedback to IRS1/2 (40), resulting in Akt activation, the combined treatment of rapamycin and an Akt inhibitor might have a greater effect to suppress uncontrolled cell proliferation in BHD-knockout mice. Alternatively, kidney cells that have lost folliculin function before P7 may be irreversibly committed to proliferation before initiation of rapamycin treatment at P7.

We previously reported the identification of a novel FLCN binding partner, FNIP1, that also interacts with AMPK, and suggested that FLCN through FNIP1 might interact with the AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways (12). Although in those in vitro studies using serum-starved conditions, Akt-mTOR signaling in BHD-null tumor cells was slightly elevated relative to BHD-restored cells, no differences were seen in AktmTOR signaling between these two cell lines under normal culture conditions. In contrast, inappropriate activation of mTOR signaling was clearly observed in response to kidney-specific BHD inactivation in the mouse. The inconsistencies between the BHD-null cell culture data and the BHD-knockout mouse phenotype underscore the biologic differences between in vitro and in vivo systems and will require further experimentation for clarification.

The obvious limitation of this study is the use of mice to model human disease. Mouse models of human cancer do not always recapitulate the human cancer phenotype as is the case for the BHD-knockout mouse model. Although we have succeeded in inactivating both copies of the BHD gene in mouse kidney epithelial cells, the highly cystic kidneys did not develop frank renal neoplasms prior to renal failure and death. In human BHD patients on the other hand, inactivation of both BHD alleles in a kidney cell leads to renal tumorigenesis. Although we were encouraged by the partial response to rapamycin treatment seen in the BHD-knockout mice, we must be cautious in our interpretation of these results as indicative of a potential treatment for human BHD syndrome.

In conclusion, we have developed a kidney-specific BHD-targeted mouse model that displays a marked polycystic phenotype within the first 3 weeks of life. In this model, homozygous inactivation of BHD results in abrupt, uncontrolled cell proliferation, supporting the idea that loss of BHD tumor suppressor function may be the first event in multi-step renal carcinogenesis in the mouse (41-42). For the BHD-inactivated mouse kidney cell to progress to a neoplasm, we hypothesize that additional genetic or epigenetic events may be required to give the BHD-null cell a growth advantage and to facilitate progression to renal carcinoma. Indeed, multi-step renal cancer progression is suggested by the presence of regions of benign “oncocytosis” adjacent to oncocytic-hybrid tumors in the kidneys of BHD patients (8). Because BHD-targeted mice develop a striking kidney phenotype over a very short time, this model may be useful for the development and testing of new therapies or drugs (i.e., rapamycin) with which to treat BHD patients and BHD-associated kidney cancers, including sporadic chromophobe renal cancer.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute (NCI), Center for Cancer Research. This project was funded in part with federal funds from the NCI, NIH, under contract N01-C0-12400. NIH grants: P30DK079328 and ROI DK067565 (P.I.)

NOTES

We thank Louise Cromwell for excellent technical support with the mouse studies, Mary Ellen Palko for helpful discussions regarding recombineering methodology, and Tim Back for his technical expertise and discussions regarding mouse surgical procedures. We thank Maria Merino for informative in-depth discussions of comparative human/mouse normal and abnormal histopathology, Octavio Quinones for support in producing some descriptive statistics and graphs, and acknowledge the support provided to us (V.P. and P. I.) by the University of Texas Southwestern O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Heath and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

NCI-Frederick is accredited by Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and follows the Public Health Service Policy for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council; 1996; National Academy Press; Washington DC).

REFERENCES

- 1.Birt AR, Hogg GR, Dube WJ. Hereditary multiple fibrofolliculomas with trichodiscomas and acrochordons. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1674–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toro JR, Glenn GM, Duray PH, Darling T, Weirich G, Zbar B, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome: A Novel Marker of Kidney Neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1195–1202. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zbar B, Alvord WG, Glenn GM, Turner M, Pavlovich CP, Schmidt L, et al. Risk of renal and colonic neoplasms and spontaneous pneumothorax in the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR, Matrosova V, Glenn GM, Turner ML, et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:157–64. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoo SK, Giraud S, Kahnoski K, Chen J, Motorna O, Nickolov R, et al. Clinical and genetic studies of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Med Genet. 2002;39:906–12. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.12.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt LS, Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Glenn GM, Toro JR, Merino MJ, et al. Germline BHD-mutation spectrum and phenotype analysis of a large cohort of families with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:1023–33. doi: 10.1086/430842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leter EM, Koopmans AK, Gille JJ, van Os TA, Vittoz GG, David EF, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome: Clinical and Genetic Studies of 20 Families. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(Jul 5):1561–1828. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavlovich CP, Walther MM, Eyler RA, Hewitt SM, Zbar B, Linehan WM, et al. Renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1542–52. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200212000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavlovich CP, Grubb RL, 3rd, Hurley K, Glenn GM, Toro J, Schmidt LS, et al. Evaluation and management of renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Urol. 2005;173:1482–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154629.45832.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami T, Sano F, Huang Y, Komiya A, Baba M, Osada Y, Nagashima Y, Kondo K, Nakaigawa N, Miura T, Kubota Y, Yao M, Kishida T. Identification and characterization of Birt-Hogg-Dube associated renal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2007;211:524–31. doi: 10.1002/path.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vocke CD, Yang Y, Pavlovich CP, Schmidt LS, Nickerson ML, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. High Frequency of Somatic Frameshift BHD Gene Mutations in Birt-Hogg-Dube-Associated Renal Tumors. J Natl Cancer Ins. 2005;97:931–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baba M, Hong SB, Sharma N, Warren MB, Nickerson ML, Iwamatsu A, et al. Folliculin encoded by the BHD gene interacts with a binding protein, FNIP1, and AMPK, and is involved in AMPK and mTOR signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603781103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005;37:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corradetti MN, Inoki K, Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Guan KL. Regulation of the TSC pathway by LKB1: evidence of a molecular link between tuberous sclerosis complex and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1533–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1199104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eng C. PTEN: one gene, many syndromes. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:183–98. doi: 10.1002/humu.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwiatkowski DJ, Manning BD. Tuberous sclerosis: a GAP at the crossroads of multiple signaling pathways. Hum Mol Gen. 2005;14:R1–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Slegtenhorst M, Khabibullin D, Hartman TR, Nicolas E, Kruger WD, Henske EP. The Birt-Hogg-Dube and tuberous sclerosis complex homologs have opposing roles in amino acid homeostasis in schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24583–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lium B, Moe L. Hereditary multifocal renal cystadenocarcinomas and nodular dermatofibrosis in the German shepherd dog: macroscopic and histopathologic changes. Vet Pathol. 1985;22:447–55. doi: 10.1177/030098588502200503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lingaas F, Comstock KE, Kirkness EF, Sorensen A, Aarskaug T, Hitte C, et al. A mutation in the canine BHD gene is associated with hereditary multifocal renal cystadenocarcinoma and nodular dermatofibrosis in the German Shepherd dog. Hum Mol Gen. 2003;12:3043–53. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hino O, Okimoto K, Kouchi M, Sakurai J. A novel renal carcinoma predisposing gene of the Nihon rat maps on chromosome 10. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:1147–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb02133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okimoto K, Sakurai J, Kobayashi T, Mitani H, Hirayama Y, Nickerson ML, et al. A germ-line insertion in the Birt-Hogg-Dube (BHD) gene gives rise to the Nihon rat model of inherited renal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2023–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308071100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao X, Somilo S, Igarashi P. Epithielial-specific Cre/lox recombination in the developing kidney and genitourinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1837–46. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000016444.90348.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee EC, Yu D, de Velasco J Martinez, Tessarollo L, Swing DA, Court DL, et al. A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics. 2001;73:56–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewandoski M, Meyers EN, Martin GR. Analysis of Fgf8 gene function in vertebrate development. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1997;62:159–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong S, Furihata M, Baba M, Zbar B, Schmidt LS. Vascular defects and liver damage by the acute inactivation of the VHL gene during mouse embryogenesis. Lab Invest. 2006;86:664–75. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berthet C, Aleem E, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Kaldis P. Cdk2 knockout mice are viable. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1775–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Court DL. Recombineering:a powerful new tool for mouse functional genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:769–79. doi: 10.1038/35093556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zolotnitskaya A, Satlin LM. Developmental expression of ROMK in rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F825–836. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.6.F825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi N, Chernavvsky DR, Gomez RA, Igarashi P, Gitelman HJ, Smithies O. Uncompensated polyuria in a mouse model of Bartter’s syndrome. Proc Natl AcadSoc USA. 2000;97:5434–39. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090091297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao X, Johnson JE, Richardson JA, Hiesberger T, Igarashi P. A minimal Kspcadherin promoter linked to a green fluorescent protein reporter gene exhibits tissue-specific expression in the developing kidney and genitourinary tract. J. Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1824–36. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000016443.50138.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin F, Moran A, Igarashi P. Intrarenal cells, not bone marrow-derived cells, are the major source for regeneration in postischemic kidney. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1756–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI23015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storkel S, Pannene B, Thoenes W, Steart PV, Wagner S, Drenckhahn D. Intercalated cells as a probable source for the dvelopment of renal oncocytoma. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Mol Pathol. 1988;56:185–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02890016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storkel S, Steart PV, Drenckhahn D, Thoenes W. The human chromophobe cell renal carcinoma: its probable relation to intercalated cells of the collecting duct. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Mol Pathol. 1989;56:237–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02890022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silve RB, Breton S, Brown D. Potassium depletion increases proton pump (H(+)ATPase) activity in intercalated cells of cortical collecting duct. Am J Physio Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F195–202. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.1.F195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petroulakis E, Mamane Y, Le Bacquer O, Shahbazian D, Sonenberg N. mTOR signaling: implications for cancer and anticancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(Suppl):R11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:729–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robb VA, Karbowniczek M, Klein-Szanto AJ, Henske EP. Activation of the mTOR signaling pathway in renal clear cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177:346–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts PJ, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tao Y, Kim J, Schrier RW, Edelstein CL. Rapamycin markedly slows disease progression in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:46–51. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah OJ, Wang Z, Hunter T. Inappropriate activation of the TSC/Rheb/mTOR/S6K cassette induces IRS1/2 depletion, insulin resistance, and cell survival deficiencies. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1650–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Gatekeepers and caretakers. Nature. 1997;386:761–3. doi: 10.1038/386761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maquat LE. Nonsense mediated mTNA decay:splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nrm1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]