Atherosclerotic plaque at the carotid bifurcation is the primary cause of ischemic strokes and the degree of carotid stenosis is strongly associated with stroke risk in symptomatic patients.1 Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States, constituting approximately 700,000 cases each year, of which about 500,000 are initial attacks and 200,000 are recurrent. Ischemic stroke accounts for the largest number of new strokes (88%) followed by intracerebral hemorrhage (9%) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (3%).2 Histopathologic studies of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with carotid disease have identified specific lesion characteristics associated with cerebral ischemia and the underlying mechanisms of plaque instability in the carotid share remarkably similarities with the coronary vasculature.3, 4 Apart from the degree of carotid artery stenosis, the underlying plaque morphology is an important predictor of stroke risk. Intravascular ultrasound and MRI studies have shown that echolucent and lipid-rich plaques are associated with plaque rupture.5, 6 In fact, plaque morphology is considered an additional independent predictor of cerebral infarction.

In this review, we will discuss the natural history of carotid and intracranial atherosclerosis based on our broader knowledge of coronary atherosclerosis. Early to more advanced progressive lesions of the carotid are categorized based on descriptive morphologic events as originally cited for the coronary circulation. The histologic features associated with symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid disease will also be addressed along with issues surrounding current stent based therapies for the prevention of major recurrent vascular events.

LESION DEVELOPMENT AT THE CAROTID BIFURCATION

The earliest pathologic studies in man described the predilection of atherosclerosis near branch ostia, bifurcations, and bends, suggesting that important components of flow dynamics play an important role in its initiation and development.7 Atherosclerotic plaque tends to form at regions where flow velocity and shear stress are reduced in particular at the carotid bifurcation where disturbances in blood flow deviate from a laminar unidirectional pattern. Plaque burden is greatest on the outer wall of the proximal segment and sinus of the internal carotid artery in a region of lowest wall shear stress. In marked contrast, the flow divider at the junction of the internal and external carotid artery, a region exposed to highest wall shear stress, is protected from atherosclerosis.8 Thus the unique geometry and flow properties presented by the carotid bifurcation contribute to both the degree and type of atherosclerotic plaque where the underlying morphology often outweigh the actual degree of the stenosis, as the most critical determinant of clinical events.

MORPHOLOGIC FEATURES OF CAROTID ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Various plaque morphologies thought responsible for the onset of symptomatic carotid disease have been identified. Since, overall lesion types in the carotid vasculature share common features of advanced atherosclerosis in coronaries, it seem appropriate that schemes developed to describe the evolution of coronary artery disease may be applied to the carotid, albeit with appropriate modifications. The American Heart Association (AHA) conventionally uses a numerical classification to stratify various coronary lesion types.9, 10 This scheme, however, implies an orderly linear pattern of lesion progression based on the assumption that all thrombosis occurs from plaque rupture, which latter became refuted by our laboratory and others.11–13

Our laboratory subsequently developed a modified classification scheme guided by AHA recommendations based on a culmination of pathologic findings in over 200 cases of sudden coronary death (Table 1).14 These defined morphologic criteria described for the coronary arteries can be equally applied to carotid plaques and may serve as a unifying paradigm to understand the evolution of all atherosclerotic lesions, independent of the vascular bed.

Table 1.

Various lesion morphologies in the carotid artery

| Early non-symptomatic carotid disease |

| Diffuse intimal thickening |

| Intimal xanthoma |

| Intermediate lesion |

| Pathologic intimal thickening |

| Progression of atherosclerosis leading to plaque enlargement |

| Plaque hemorrhage (± calcification) |

| Thin cap fibroatheroma (± calcification) |

| Lesions with thrombi |

| Plaque rupture with luminal thrombus |

| Plaque rupture with ulceration |

| Plaque rupture with organizing thrombus |

| Plaque erosion |

| Calcified nodule |

| Stable atherosclerotic plaque |

| Healed rupture/erosion |

| Fibrocalcific plaque |

| Total occlusion |

EARLY NON-SYMPTOMATIC DISEASE

Intimal thickening and intimal xanthoma

Pre-existing adaptive intimal thickening and the intimal xanthoma (“fatty streak”) are considered the earliest pre-lesional stage of the disease. While some human lesions may begin as intimal xanthomas, there is considerable evidence to suggest that the intimal thickening or mass lesion is most likely precursor leading to symptomatic coronary disease in humans since these lesions are found in children in similar locations as advanced plaques in adults, while fatty streaks are know to regress.15 Histologically intimal mass lesions consist mainly of smooth muscle cells and proteoglycan matrix with variable amount of lipid with little or no surrounding inflammation.

Pathologic intimal thickening

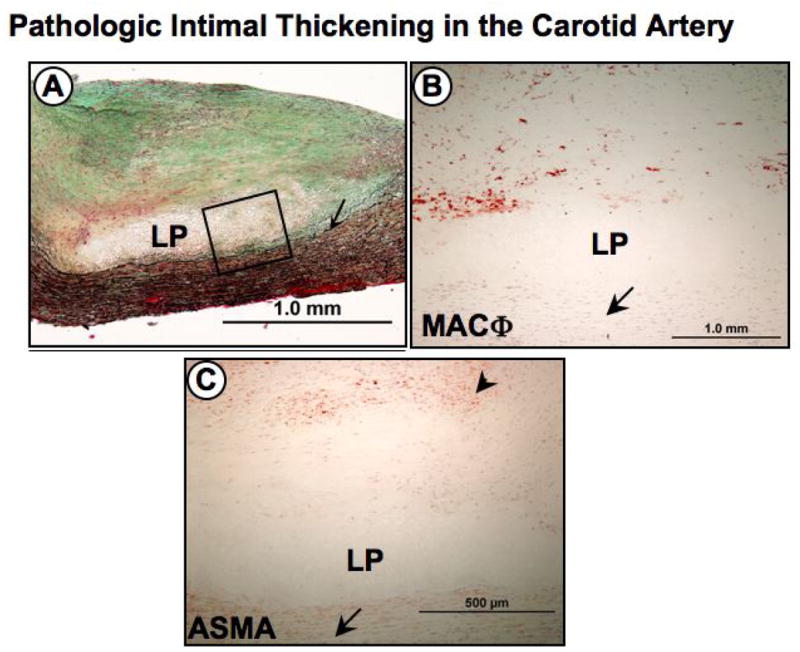

The transition from an early pre-atherosclerotic lesion to the more advanced fibroatheroma (defined by a true necrotic core) is marked by an intermediate morphology characterized by extracellular lipid pools within relatively acellular areas rich in proteoglycans.10, 14 The lipid pools tend to develop at sites of adaptive intimal thickening and are mostly located in the deeper intimal layers close to the medial wall while variable numbers of macrophages and T lymphocytes are seen outside the pool mostly confined to the inner intima (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pathologic intimal thickening (PIT) in the carotid artery.

PITs are considered progressive early lesions to the more advanced fibroatheroma, or plaques with true necrotic cores. Panel A, shows a low power image of an eccentric carotid plaque with a relatively acellular lipid pool (LP) near the medial wall (arrow). Note the absence of necrosis. Panel B, is a higher power image representing the region within the black box in A showing an absence of cells within a lipid pool with surrounding CD-68 positive macrophages (MACΦ) more towards the lumen (arrow indicates medial wall). Infiltration of superficial macrophage into the lipid pool may cause conversion to the more advanced fibroatheroma. Panel C, anti-α-smooth muscle cell actin (ASMA) immunostaining show a distribution of smooth muscle cells (arrowhead) more towards the lumen while the lipid pool (LP) is adjacent to the medial wall (arrow).

ADVANCED ATHEROSCLEROSIS

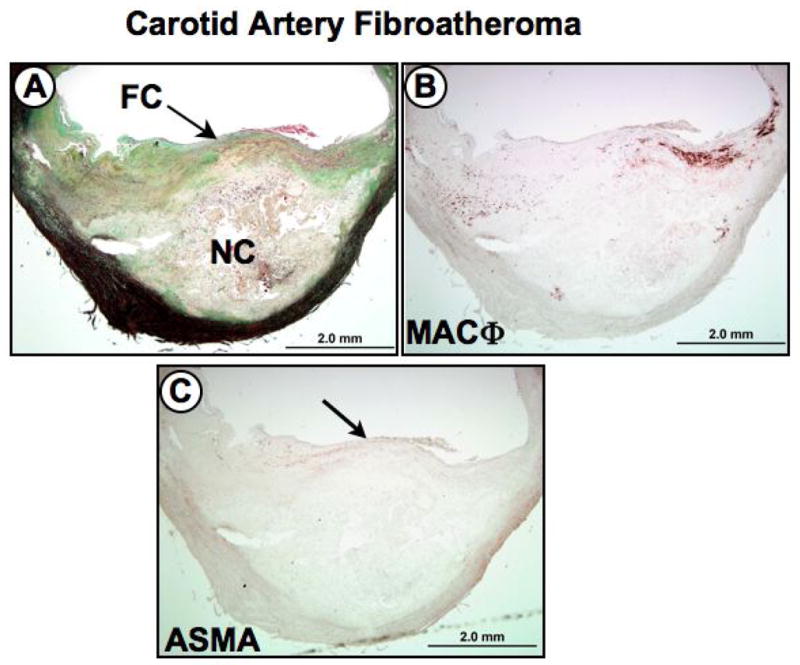

Fibrous cap atheroma

The first of the advanced coronary lesions in concordance with the AHA is the fibrous cap atheroma.9, 14 The defining feature of this lesion is a lipid rich necrotic core encapsulated by fibrous tissue (Figure 2). The fibrous cap atheroma may result in significant luminal narrowing and is also prone to complications of surface disruption, thrombosis, and calcification. The origin and development of the core is fundamental toward understanding progression of atherosclerotic disease and the question of how lesions convert from lipid-rich pools within pathologic intimal thickening to plaques with true necrosis (necrotic core) presents one of the most challenging issues in the field today.

Figure 2. Serial sections of a carotid artery fibroatheroma.

Panel A (Movat Pentachrome stain), shows an eccentric plaque with a relatively large necrotic core (NC) covered by a thick fibrous cap (FC). Panel B, shows a dense region of CD68-positive macrophages in the shoulder region of the plaque. Panel C, anti-α-smooth muscle cell actin (ASMA) immunostaining revealing a paucity of smooth muscle cells within the fibrous cap (arrow).

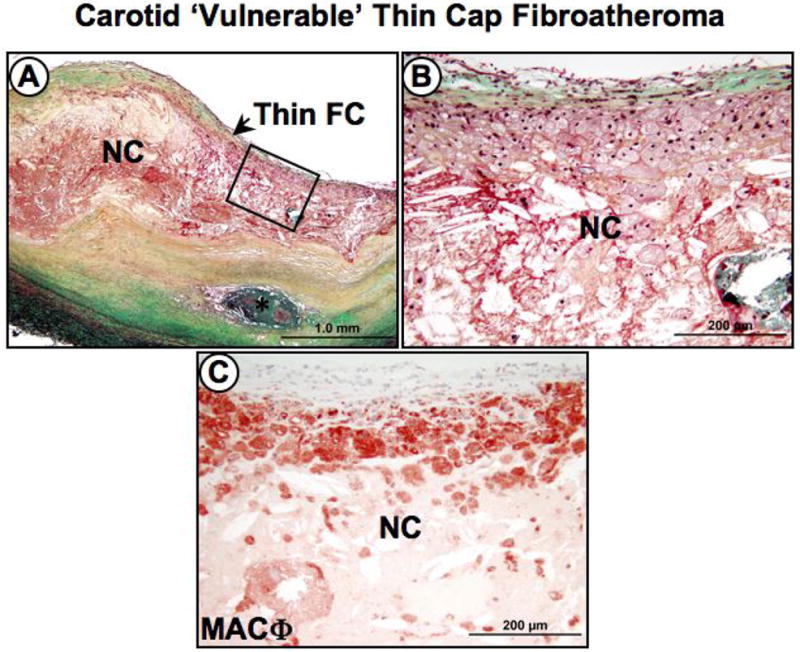

Thin fibrous cap atheroma (vulnerable plaque)

The thin cap fibroatheroma is characterized by a relatively large necrotic core representing ~ 25% of plaque area contained by a thin fibrous cap defined as <65 μm, heavily infiltrated by macrophages and some T-lymphocytes (Figure 3).16 This well-characterized ominous plaque is considered the prelude to rupture. The density of macrophages within the fibrous cap is generally very high, although in some cases macrophage infiltration may be less intense and occasionally absent. Since plaque rupture accounts for approximately 75% of thrombi in patients with sudden coronary death, early recognition of the thin cap fibroatheroma is paramount for the identification and treatment of potentially fatal lesions.17 The thinning or weakening of the fibrous cap leading to fissures and ruptures represents a common mechanism of fibrous cap disruption in both coronary and carotid arteries.18 An interrupted fibrous cap allows circulating cellular and non-cellular elements to come in direct contact with the highly thrombogenic components within the necrotic core and is responsible for luminal thrombosis.

Figure 3. Thin cap fiboratheroma ‘vulnerable’ plaque in a carotid endarterectomy specimen.

Panel A, low power image shows a carotid plaque with a relatively larger necrotic core (NC) covered by a thin fibrous cap (FC). An area of calcified necrotic core (*) is seen in the deeper intimal layers. Panel B, higher power image of an area represented by the black box in A showing the necrotic core and thin fibrous cap infiltrated by foam cells. Panel C, numerous CD-68 positive macrophages (MACΦ) are seen infiltrating the fibrous cap. Panels A and B show Movat Pentachrome staining.

FIBROUS CAP THICKNESS AND LESION INSTABILITY

It is becoming increasingly clear that fibrous cap thickness and plaque stress are predisposing elements to rupture. In a previous study of sudden coronary death victims, vulnerable plaque was defined histologically based on a fibrous cap thickness < 65 μm with regional infiltrates of macrophages (>25 per 0.3-mm-diameter field).16 The critical thickness of 65-μm that renders a coronary lesion “vulnerable” is derived from a series of measurements at rupture sites where fibrous caps measured 23±10 μm with 95% of caps 64 μm or less. A similar approach can be applied to carotid arteries with rupture. In a relatively large series of carotid plaques from our laboratory the mean fibrous cap thickness was 72±24 μm and vulnerable plaque thickness (95% of ruptured plaques) was identified at <120 μm (RV, unpublished data) (Figure 3). These values are remarkably within the range predicted by flow-plaque interactions models where a fibrous cap thickness of <0.1 mm, is predicted to induce a large plaque stress that could precipitate rupture, even with an underlying 10% luminal stenosis.19 In another larger series of over 412 symptomatic (major stroke or TIA) and asymptomatic patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy, vulnerable fibrous cap thickness (measured histologically) was defined at <165 microns based on a mean (± SD) cap thickness of 70±47 μm in ruptured plaques (Mauriello et al 2007 unpublished data)

It is our experience, approximately half of plaque ruptures occur towards the midportion of the cap rather than the shoulder region in autopsy plaques derived from sudden coronary deaths. Using a computational finite element (FEM) model, Cheng et al., calculated the stress distribution in specific coronary artery lesions that caused lethal myocardial infarction and found the average maximum circumferential stress in ruptured plaques was 545±160 kPa.20 Notably, not all plaque ruptures occurred at the region of highest stress as 10 of 12 lethal lesions, ruptured where calculated stress was not maximal but was 300 kPa. A more precise explanation of why this occurs comes from a more recent study suggesting that minute calcifications of 10-μm-diameter found at sites of relatively high circumferential stress (>300 kPa) in the fibrous cap can intensify the stress levels to nearly 600 kPa when the cap thickness in <65 μm.19 Thus, the site of rupture depends on the relative location concentrated circumferential stress and whether microscopic calcific inclusions perhaps derived from apoptotic macrophages or smooth muscle cells are present.21 Collectively, these studies highly suggest that fibrous cap rupture is very likely a multifactorial event, unpredicted by stress factors or cap thickness alone.

In coronary arteries of humans, plaque rupture generally occurs in lesions with less than 50% diameter stenosis. Our laboratory and others suggest that plaque rupture is not a rare event in the evolution of coronary atherosclerosis.22, 23 In this context, rupture of the lesion surface is followed by variable amounts of hemorrhage into the plaque and luminal thrombosis causing often clinically silent progression of the disease.

Carotid plaques follow a similar pattern of disruption with fibrous cap thinning and infiltration of macrophages. (Figure 3) In a recent study, 47% of carotid ruptured plaque occurred in arterial segments with less than 70% cross-sectional luminal narrowing. Furthermore, a high prevalence of vulnerable plaques occurred in segments not significantly narrowed (80% of cases) (Mauriello, unpublished data, 2007). These data suggest that culprit lesions and their precursors occur more frequently in less severely narrowed vessels and highlight the important tenet that plaques may progress to a substantial size through repeated ruptures before significant luminal stenosis occurs.

LESIONS WITH THROMBI

Plaque rupture with acute or early organizing luminal thrombi

Acute thrombosis is predominantly characterized by layered platelet aggregates with variable amounts of fibrin, red blood cells, and acute inflammatory cells. Over time, this provisional matrix heals by a concerted biological process involving the infiltration of smooth muscle cells, accumulated extracellular matrix proteins (ie., proteoglycans and collagen), neovascularzation, inflammation, and luminal surface re-endothelialization.

At least 75–80% of sudden coronary deaths show occlusive acute or organized thrombi, while death in the remaining cases is attributed to a “critical” ≥75% cross-sectional stenosis in a lesion generally referred to as stable plaque.24 While plaque rupture with luminal thrombosis is similarly considered to be the major etiology of carotid stroke, thrombi occupying large portions of the lumen in these cases are unusual.3 The embolic nature of rupture in the carotid is uncharacteristic of coronary plaques as thrombotically active plaques are found in 74% of patients with ipsilateral stroke.4

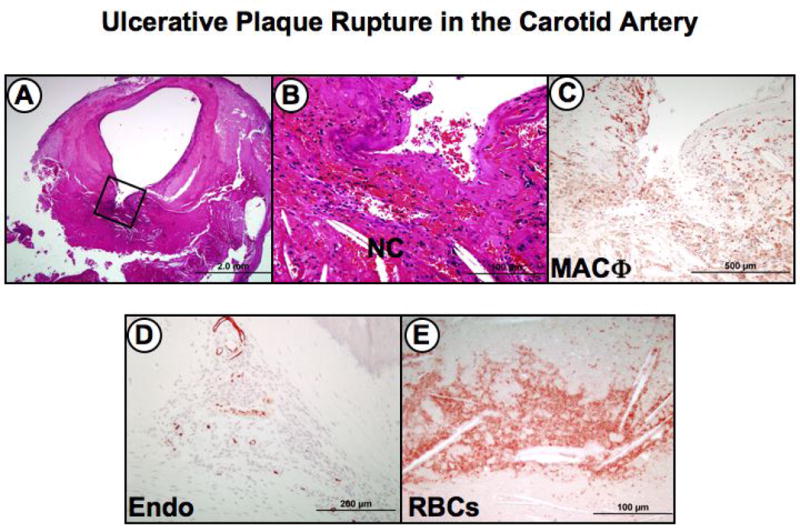

Carotid plaque rupture with ulceration

Most pathologists agree that plaque rupture with ulceration is the dominant mechanism that leads to thrombus formation in the carotid disease complicated by embolization and cerebral ischemic events.3, 25 Plaque ulceration, is defined as an excavated necrotic core underneath a ruptured fibrous cap often with large areas of intraplaque hemorrhage and little or no luminal thrombus (Figure 4). If present, the thrombus it is generally small and usually non-occlusive. In a recent large series of carotid endarterectomy specimens from symptomatic and asymptomatic patients collected in a study correlating risk factors to plaque morphology, ulcerated lesions were the most common finding, irrespective of clinical status. (Mauriello et al, unpublished data, 2007) The larger vessel caliber and flow velocity of the carotid may explain the embolic nature of these plaques where shear forces are greater compared to the coronary circulation.

Figure 4. Serial sections of plaque rupture with ulceration in a carotid endarterectomy specimen.

This lesion is the most frequent finding in patients with symptomatic carotid disease. Panel A, the low power image shows a disrupted fibrous cap with a relatively large excavated necrotic core (boxed area). Note the absence of a significant luminal thrombus. Panel B, higher power view of the area represented by the black box in A, showing the excavated necrotic core with recent hemorrhage and cholesterol clefts. Panel C, numerous CD-68 positive macrophages (MACΦ) are seen infiltrating the fibrous cap and surrounding necrotic core. Panel D, Immunostaining with the endothelial marker Ulex europaeus lectin showing intraplaque neovascularization in the plaque shoulder near the necrotic core. Panel E, old intraplaque hemorrhage in an deep area of the necrotic core rich in free cholesterol (clefts) as visualized by anti-glycophorin A immunostaining. Panels A and B, hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Plaque erosion with acute or early organizing luminal thrombi

Plaque erosion presents the second leading cause of acute coronary thrombosis in the coronary circulation. This lesion differs from that of rupture, since there is an absence of fibrous cap disruption highlighted by luminal surface rich in proteoglycans that lacks endothelium. The underlying lesion morphology also differs from rupture since it includes early lesions with pathologic intimal thickening or to a lesser extent, fibroatheromas without extensive necrotic cores. Erosion is defined as an acute thrombus in direct contact with an intimal surface that lacks endothelial cell coverage. The morphologic characteristics of plaque erosion include abundance of smooth muscle cells in a proteoglycan matrix and disruption of the surface endothelium without a prominent lipid core.12 There are usually few or absent macrophages and T-lymphocytes close to the lumen in plaque erosion. Erosions account for approximately 30% to 35 % of cases of thrombotic sudden coronary death and are more common in patients under the age of 50 years and represent the majority of acute coronary thrombi in premenopausal women.24

Plaque erosion is an infrequent cause of acute thrombosis in the carotid artery, irrespective of symptoms.3, 4 In the carotid vasculature, the incidence of erosion accounts for <10% of all luminal thrombi. It is suspected that the rarity of plaque erosions may be related to the higher flow rates, larger vessel caliber, or relative absence of vasospasm since erosion in the coronary artery is attributed to episodic arterial contraction and loss of endothelial cells.

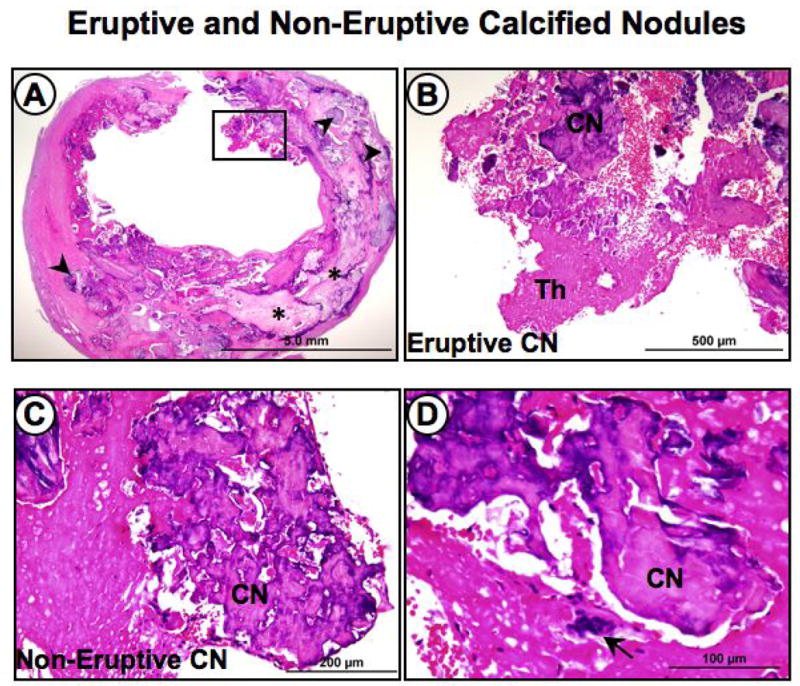

Nodular calcification

The “calcified nodule” represents the least frequent cause of luminal thrombus accounting for 2–5% of coronary thrombi.14 This term is reserved for fibrocalcific plaques with little or no underlying necrotic core with disruption at the luminal surface and thrombosis attributed to eruptive dense calcified nodules. These heavily calcified arteries often show large plates of calcified matrix with surrounding areas of fibrosis, inflammation, and neovascularization (Figure 5). Although the precise nature of this lesion remains incompletely understood, fragmentation of the calcified plates is believed to represent the etiology of the nodular calcification where even sometimes bone formation is seen with interspersed fibrin. Although nodular calcification in deeper regions of the plaque is quite common in the carotid its association with a luminal thrombus remains infrequent constituting only 6–7% of thrombi (RV, unpublished data).

Figure 5. Eruptive and non-eruptive nodular calcification in carotid atherosclerosis.

Panel A, the low power image of a carotid endarterectomy specimen shows extensive calcification represented by larger plates (*) and multiple smaller nodules (arrowheads). Panel B, higher power image of area represented by the black box in A, showing eruptive nodular calcification (CN) with a luminal thrombus (Th). Panel C, shows nodular calcification near the luminal surface without a luminal thrombus. Panel D, the higher power view shows an osteoclast-like cell, which is frequently associated with nodular calcification. Panels A to D hematoxylin and eosin stains.

STABLE ATHEROSCLEROTIC PLAQUE

Healed rupture/erosion

Healed lesions consisting of previous ruptures, erosions and total occlusions define a third category of atherosclerotic plaques. Healed plaque rupture in the coronary vasculature is identified based on a disrupted fibrous cap with a surrounding repair reaction.22 The matrix within the healed fibrous cap generally begins as an early proteglycan-rich mass, which eventually develops into a collagen-rich scar as the thrombus heals. Healed ruptures frequently exhibit multi-layers of necrotic cores with lipid in the deeper intima suggestive of previous thrombotic events contributing to lesion progression.22 This significant increase in plaque burden and luminal narrowing due to previous thrombosis may occur in the absence of cardiac symptoms. In our series of sudden coronary death patients who died with acute plaque rupture, those with healed myocardial infarction had the highest frequency of healed plaque ruptures.22

Multiple healed plaque ruptures are also found in the carotid artery as well and similarly, a layering of healed repair sites is an underlying cause of luminal narrowing, to some degree. A recent examination of over 400 carotid endarterectomy specimens shows previous ruptures in approximately 15% of patients. (Mauriello unpublished data, 2007) While repetitive thrombosis can lead to progressive narrowing in the coronary artery, in the carotid the thrombosis does not typically occupy a large portion of lumen and may explain why the prevalence of multiple healed ruptures are somewhat less frequent.

Fibrocalcific plaques

Fibrocalcific plaques are lesions recognized by a thick fibrous cap with an extensive accumulation of calcium typically in the deeper intimal layers.14, 26 These lesions are frequently found in patients with a history of stable angina. Although there is a high correlation of coronary calcification with plaque burden its causal relationship in plaque instability is less clear. Since the necrotic core size is usually minimal to absent, this lesion is not considered a true fibroatheroma. Severely narrowed fibrocalcific plaques most likely represent an end-stage or ‘burned-out’ process of rupture with healing marked by excessive calcification.

Several mechanisms are likely responsible for calcification of an atherosclerotic plaque some of which include cell death, expression of selective extracellular matrix proteins, and intraplaque hemorrhage.27, 28 It is unknown whether processes of calcification share similarities in carotid versus coronary lesions or other sites in the vasculature. In our experience the majority of lesions from asymptomatic patients with carotid disease represent fibrocalcific plaques. Notably, the frequency of calcification is similar in coronary and carotid arteries, with maximum calcification in carotids occurring in lesions with lumens narrowed greater than 70% in cross-sectional area.

Chronic total occlusion

Chronic total occlusions demonstrate varied pathology depending on the age of the thrombus.14 Earlier phases of organizing thrombi are characterized by fibrin, red blood cells, and granulation tissue. Older lesions demonstrate luminal obstruction composed of dense collagen and/or proteoglycan with interspersed capillaries, arterioles, smooth muscle cells, and inflammatory cells. Total occlusions often demonstrate shrinkage or negative remodeling of the artery likely resulting from contraction of the collagen-rich thrombus or extracellular matrix within the plaque. In sudden coronary death victims without a prior history of coronary artery disease, the incidence of total occlusion is 40% while in the carotid the frequency is much less since the higher flow rates cause the majority of thrombus to embolize.

THE CONTRIBUTION OF INTRAPLAQUE HEMORRHAGE TO LESION ENLARGEMENT INSTABILITY

Recently, our laboratory and others have reported on the significance of hemorrhage as a mechanism of necrotic core enlargement and macrophage infiltration in coronary plaques at autopsy and in the clinic, respectively.29–32 Red blood cell membranes are an important contributor of cholesterol monohydrate and lipid content in plaques and leaky vasa vasourm are the most likely source of hemorrhage.32 Immunostains for glycophorin-A (a protein exclusive to red blood cell membranes) are strongly positive in advanced coronary atheroma whereas early plaques generally show an absence or low expression of glycophorin-A. Further, leaky vasa vasorum promote the seepage of extravascular fibrinogen/fibrin, which is observed in 10 to 20% of severely narrowed coronary plaques (RV, unpublished data, 2007). The biological processes initiated by accumulated fibrinogen/fibrin within an atheroma may constitute an early step in the angiogenic response shared by tumors, wound healing, and inflammation.

Intraplaque hemorrhage is also recognized as an important pathologic process associated with carotid plaque progression and the development of neurologic symptoms suggesting that hemorrhage itself is related to plaque disruption or may lead to critical stenosis.25, 33, 34 The incidence of intraplaque hemorrhage in the carotid circulation is reported higher in symptomatic versus asymptomatic patients (84% vs 56%, respectively3) and plaque vascularity has been shown to correlate with intraplaque hemorrhage and the presence of symptomatic carotid disease.35 These new blood vessels could play an active role in the metabolic activity of the plaque and ultimately control the processes that govern plaque progression. In addition, fibrin is a common finding in mature atherosclerotic lesions and most likely represents chronic hemorrhage within the plaque.

The relationship of hemorrhage to necrotic core expansion was recently demonstrated in subjects with carotid atherosclerotic plaques by serial high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. In a prospective study, 154 consecutive asymptomatic patients with 50–79% carotid stenosis detected by ultrasound were evaluated by serial MRI every 18 months.31 In a mean follow-up period of 38.3 months, 12 carotid cerebrovascular events occurred which correlated with carotid MR characteristics of a thin or ruptured fibrous cap, intraplaque hemorrhage, larger intraplaque hemorrhage area, and large necrotic core and plaque dimensions. In another case control study of 29 asymptomatic carotid plaques followed over an18 month period, the identification of intraplaque hemorrhage at baseline was associated with an increased frequency of new hemorrhages and greater enlargement of necrotic core when compared to patients without plaque hemorrhage with comparably sized plaques at baseline.

Multiple pathways of entry leading to intraplaque hemorrhage include ruptures/fissures and leaky luminal or advential vasa vasorum. Careful study of coronary plaques at autopsy in our laboratory and others suggest that adventitial vasa vasorum are the dominant source of intraplaque neovascularization and hemorrhage.32 The distribution of adventitial vasa varorum depends on the vascular bed and studies have shown coronary arteries have the largest number of vasa vasorum followed by carotid, aorta, and renal arteries with the lowest frequency in femoral arteries.36 There is a suggestion that the extent of vasa vasorum correlates with the rapidity with which atherosclerosis develops in these arteries. This observation is further supported by the fact that vessels that inherently lack vasa vasorum such as the internal thoracic artery or distal cerebral arteries also are resistant to the development of atherosclerosis.

Comparative immunohistochemical studies of intracranial and systemic arteries show a relative lack of adventitial vasa vasorum within intracranial arteries in neonates, children, and adults, although their medial thickness is comparable to their systemic counterparts with vasa vasorum.37 The existence of vasa vasorum is more common in the proximal arteries (vertebral, internal carotid, and basilar arteries) than in the distal middle cerebral and anterior cerebral arteries.38 Moreover, vasa vasorum are found more frequently in aged patients with severe atherosclerosis and those with cerebrovascular diseases.

THE PATHOLOGY OF BARE METAL CORONARY STENT IMPLANTS

After Gruntzig et al originally described the first percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)39, balloon angioplasty had been widely performed for severely narrowed atherosclerotic coronary artery lesions. However, limitations such as high rates of restenosis with early plaque recoil and late arterial shrinkage,40, 41 hamper this technique. Compared to conventional balloon angioplasty, the advent of coronary artery stents offers much improved radial strength therefore, preventing both acute and chronic causes of narrowing resulting in reduced rates of acute arterial closure and late restenosis.42

The introduction of stenting however, was accompanied by a high frequency of acute stent thrombosis and despite later improvements in anti-platelet therapy and stent deployment techniques, minor non-occlusive adherent platelet/ fibrin thrombi around stent struts are common in early implants of < 3-days.43 At 1 month, platelets are no longer apparent, and fibrin usually becomes incorporated into the neointima. Acute inflammatory cells, mainly composed of neutrophils, are associated with stent struts and frequently present in early time periods, however, these cells are rarely observed beyond 1 month.44 In contrast, chronic inflammatory cells such as macrophages and/or giant cells are present at all time points 44 as a foreign body reaction to the stent itself since the exposure of stent struts is permanent.

From 2 weeks after stent implantation, the neointima consists primarily of smooth muscle cells and proteoglycans. Recognized pathological factors such as the degree of medial injury, inflammation, and strut penetration into the necrotic core are identified as predictors of restenosis resulting from excessive neointimal growth.45 Moreover, reendothelialization of the stented luminal surface is considered pivitol as a deterrent to stent thrombosis and complete endothelialization is typically confirmed by 3- to 4-months in bare metal stents.46, 47

THE PATHOLOGY OF CORONARY DRUG-ELUTING STENTS

Despite the implementation of stent technology over balloon angioplasty, restenosis was still considered a major limitation with a prevalence approaching 20–30%.48 Since the primary cause of restenosis is attributed to excessive smooth muscle cell proliferation, the development of new technologies mainly focused on cell specific targets aimed at preventing neointimal hyperplasia. The achievements of oral pharmacologic therapy in animal models of in-stent restenosis led to clinical trials in the early 1990’s, which for the most part produced disappointing results.49 Real clinical success, however, was reached, with the advent of localized therapy using stents as the drug delivery platform.50 This method of sustained drug delivery takes advantage of polymers to attach and promote controlled elution of drugs from the stent. It was a series of successful pre-clincial studies51–54 that paved the way for stent based local drug delivery in man. The first in man study 55 and the later larger multicenter RAVEL56 (randomized study with the sirolimus eluting Bx Velocity balloon expandable stent in the treatment of patients with de novo native coronary artery lesions) clinical trial produced an astonishing zero percent restenosis.

The local delivery of cytotoxic or cytostatic drugs using a stent based (DES) technology has markedly reduced restenosis after PCI.57, 58 Currently, polymer-based sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents are the only DES approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and widely used in the US. Despite the goal of preventing mitogen-induced smooth muscle cell proliferation, the early preclinical studies showed these drugs to markedly delay arterial healing characterized by persistent fibrin deposition and poor luminal surface endothelialization. Further it is evident from pre-clincal studies that with continued implant duration there is improved arterial healing with a return of neointimal growth and absence of long-term effects.51, 59

In the emergent age of DES, little was known of their pathologic consequences in humans. Our laboratory reported the first histologic findings of a Cypher (16 month) stent implanted for treatment of an 80% proximal LAD occlusion.60 The device was widely patent, with a minute thrombus at the ostium of a small side branch. There was mild neointimal thickening with near complete healing evidenced by only little accumulated fibrin near stent struts. Inflammation was rare and scanning electron microscopy of the luminal surface showed >80% endothelial coverage with poorly formed endothelial cell junctions and rare platelet aggregates localized to the area of the side branch.60 At the time, this single stent provided a brief glimpse into the reality of stenting in man and supported some of the results from earlier animal studies where similar morphologic changes occurred albeit with a markedly shortened interval of healing. In a later report from our laboratory, we describe a case of hypersensitivity in an 18-month Cypher stent implant, which implicates the polymer as the potential culprit for the reaction. In cannot be overemphasized that polymers are not all safe.61 Even in pre-clinical studies, eosinophilic granulomatous reactions are found around 50 to 70% of stent struts in 9-months Cypher stent implanted in swine coronary arteries (RV, unpublished data, 2007). In our experience, this type of inflammatory reaction has never been observed with bare stainless steel stents.

A more recent examination of a larger series of DES at autopsy in our laboratory shows early platelet and fibrin thrombi adherent to stent struts and infiltration of neutrophils, which is fundamentally similar to BMS.47 However, persistent fibrin deposition beyond 1 month was frequently observed in DES together with chronic inflammatory cells. Moreover, substantial delayed arterial healing with minimal neointimal growth and incomplete coverage of endothelial cells was consistently found in DES cases regardless of the duration after implantation.

In humans, re-endothelialization following BMS implantation in the coronary circulation is near complete by 3–4 months whereas for DES it is projected to take much longer. Moreover, other indications in ‘Real World’ stenting such as longer lesion lengths often require, overlapping DES, which may further impair re-endothelialization. As a proof-of-concept, we implanted overlapping pairs of Cypher or Taxus stents in rabbit iliofemoral arteries with subsequent en face examination by scanning electron microscopy. These studies demonstrated markedly delayed re-endothelialization at 28-days, in particular at sites of stent overlap, which was persistent up to 90-days implantation.62

Recent clinical reports of very late thrombosis occurring in drug-eluting stents beyond 1 year have alerted the medical community of the possible complications of this technology. In our laboratory, the pathologic outcomes of the two FDA approved Cypher and Taxus stents was recently examined in a relatively large series of post-mortem cases.47 Arterial healing, as evidenced by persistence of fibrin, poor neointimal thickening, and incomplete re-endothelialization, was markedly delayed in DES versus BMS with mean implant duration of 9 months (Figures 6 to 8). Moreover, late stent thrombosis of the target vessel as defined by >30 days was noted in 14 of 23 patients receiving DES with 13 patients dying of stent-related causes. Notably, DES with late thrombosis showed even a less matured neointima as compared to patients with DES without thrombotic occlusion. Additional procedural and pathologic risk factors for late stent thrombosis were identified as: local hypersensitivity reactions to the stent; ostial and/or bifurcation stenting; malapposition/incomplete apposition of struts; restenosis; and strut penetration into a necrotic core.47

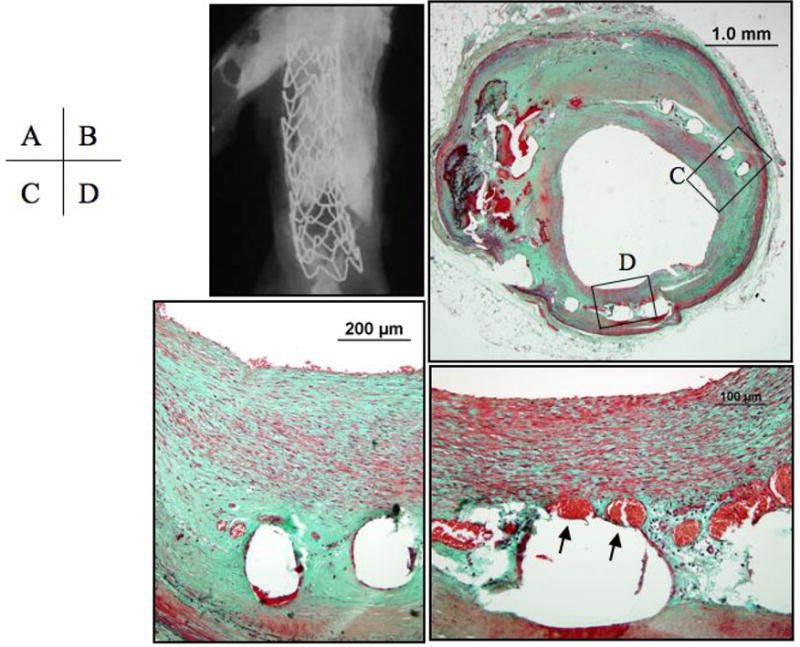

Figure 6. Bare metal stent in coronary artery at 7 months after implantation.

Panel A, the radiograph of the explanted stent shows severe calcification of the arterial segment evidenced by the hyper-dense areas. Panel B, a cross section of middle portion of the stent showing a widely patent lumen with all struts are covered by neointimal growth. Panels C and D, higher magnifications of the regions represented by the respective black boxes in B showing a neointima composed primarily of smooth muscle cells and proteoglycans (bluish-greeen on Movat pentachrome) with neoangiogenesis (arrows). Panels B to D, Movat Pentachrome staining.

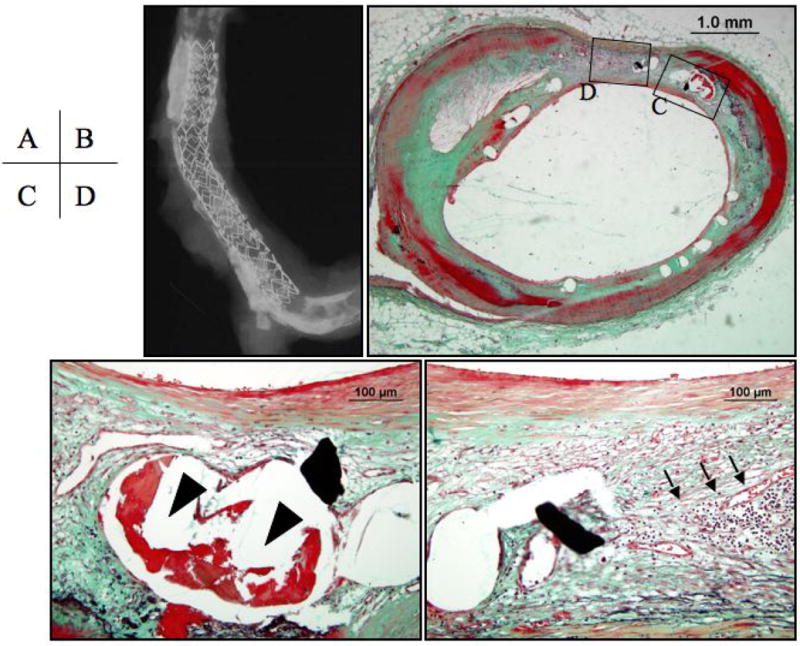

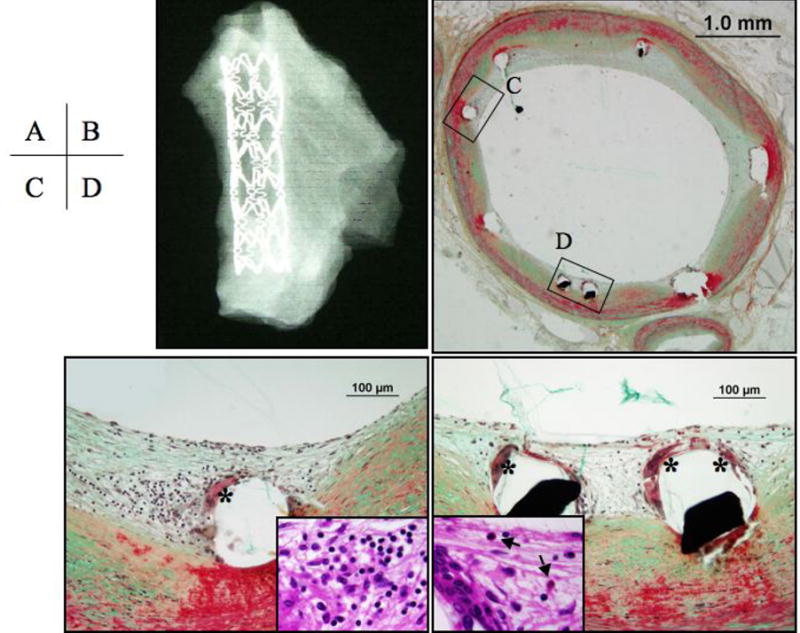

Figure 8. Drug-eluting coronary Taxus™stent at 7 months after implantation.

Panel A, the radiograph shows a Taxus™ stent in a tortuous and calcified vessel. Panel B, the cross sectional image shows minimal neointimal coverage over stent struts. Panels C and D, higher magnifications of the regions represented by the respective black boxes in B, note the persistent fibrin accumulated around stent struts (arrowheads) together with chronic inflammatory cells of mainly, lymphocytes (arrows).

In DES, re-endothelialization was further delayed compared to BMS (55.8±26.5% vs. 89.8±55.8%, p = 0.0001) regardless of implant duration. In fact, BMS had significantly greater endothelialization than DES at all time points studied. How long DES will remain incompletely endothelialized is still unclear. In the RAVEL trial the neointimal growth increased with every year up to the 5-year time point when data is available. As experience grows, our understanding of the pathophysiology of DES, in particular the behavior of endothelial cells will undoubtedly improve, in particular in devices with longer implant durations.

Recently, the feasibility of DES implantation for intracranial lesions has been reported.63, 64 Although DES showed effectiveness in terms of angiographic results, issues of safety, as noted in coronary arteries, should not be solely established by mid-term follow-up. Critical issues such as vessel tortuosity, calcified lesions, hypersensitivity, delayed endothelialization are still unresolved. Moreover, long-term studies are necessary to determine the restenosis rates of DES in cerebral vessels, in particular, in comparison to bare metal stents. Finally, the lessons learned from the clinical experience of DES implantation in coronary artery has identified the potential limitation of late stent thrombosis where the feasibility of a successful anti-platelet regimen should be carefully considered before using an intracranial DES.

THE PATHOLOGY OF CAROTID STENTING

The carotid artery is one of the more susceptible locations for atherosclerosis development since its anatomy presents a rather large bifurcation site with dramatic changes in regional blood flow and shear stresses. Reports of the advantages of carotid endarterectomy over conventional medical therapy led to even asymptomatic patients with severe carotid artery stenosis to be treated by this surgical approach.65–67 Many patients however, still remain “high risk” surgical candidates because of their co-morbidities and therefore, percutaneous intervention (stenting) for carotid artery stenosis is the current treatment of choice for this population. Recently, Yadav et al reported the favorable results of carotid stenting in high-risk patients with emboli-protection-devices compared to surgery.68

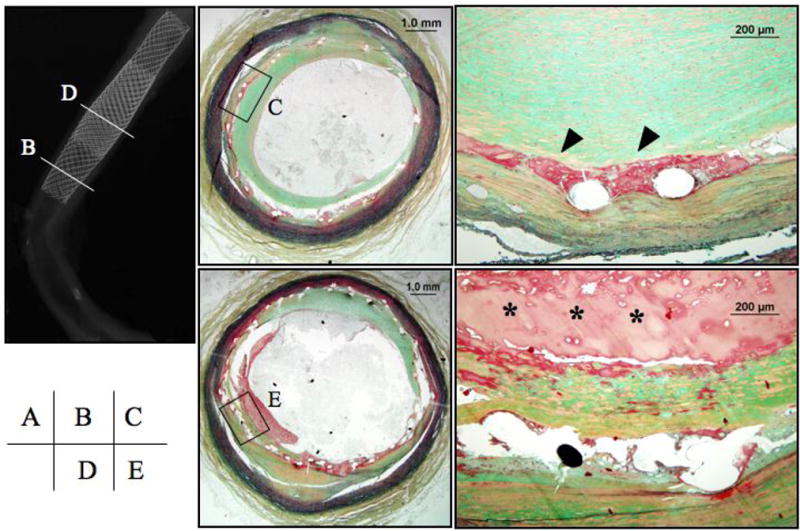

The pathology of carotid artery stents is not well characterized, since tissue availability for study is limited. Comparable lesion morphologies, however, in coronary and carotid arteries are expected to produce similar degrees of healing in response to stenting, although in-stent restenosis after carotid stenting is reported lower in the range of 4% to 16%69–71, which may reflect the larger vessel caliber of the carotid. From our small number of autopsy cases, restenosis was documented in those arteries with extensive inflammation. Therefore, persistent inflammation seems an important risk factor of restenosis, which is consistent with coronary stent implants. Anecdotal data suggest that the time course of arterial healing may vary in coronary versus carotid stents. In a recent study by Buhk et al, delayed late stent thrombosis (defined as > 1 week and < 3 months) occurred in three of 96 patients with carotid stenting.72 In all cases, the post-procedural antiplatelet regimen was discontinued to enable the treatment of a relevant co-morbidity. It is possible that re-endothelialization and arterial healing within carotid stents is delayed as a result of high flow rates and the shear forces caused by the bifurcation of carotid arteries. In fact, delayed arterial healing with uncovered struts and persistent fibrin was observed even at later time points among our autopsy cases (Figures 9 and 10). Further characterization of endothelialization and arterial healing in carotid stents is needed.

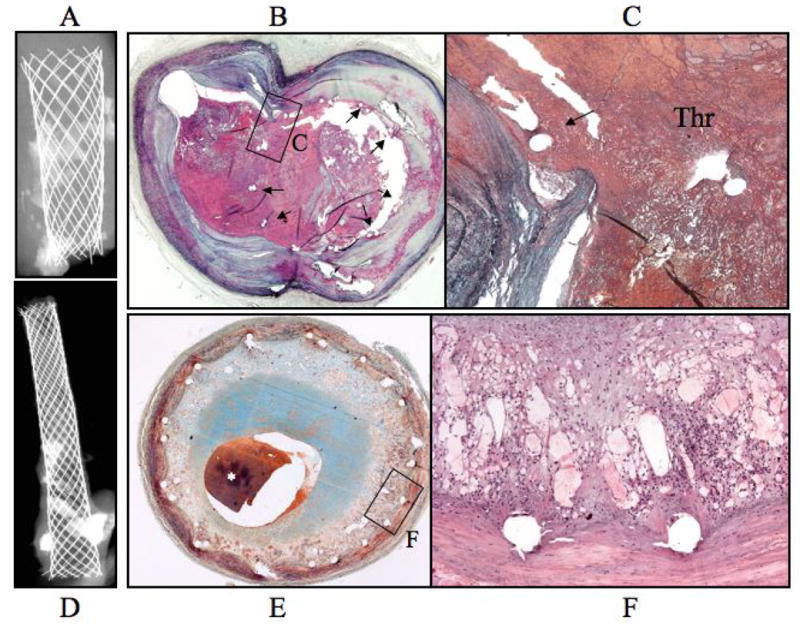

Figure 9. Carotid artery stent seven years after implantation.

Panel A, the radiograph shows a pair of similar overlapping stents with tranverse sections taken for histology from the proximal non-overlap (slice B) and middle overlaping (slice D) region. Panel B, a cross sectional image from proximal regions of the stents shows a widely patent lumen. Panel C, Higher magnification represented by the region within the black box in B showing accumulated fibrin around stent struts. Panels D and E, are low and higher power cross sectional images at a site of strut overlap. Several stent struts remain poorly covered by neointimal growth and are surrounded by a non-occlusive, non-flow limiting fibrin-rich thrombus (*).

Figure 10. Carotid artery stents eight- (panels A to C) and ten- (panels D to F) months after implantation.

Panel A, radiograph of an eight month stented carotid segment with focal calcification. Panel B, the cross sectional image at the carotid bifurcation shows an occlusive thrombus with stent struts remaining uncovered by neointimal growth (arrows). Panel C, the higher power image represented by the area within the black box in B shows a tear in the arterial wall at ostium of the side branch with a superimposed thrombus. Panel D, radiographic image of a 10-month carotid stent implant in an arterial segment with focal areas of dense calcification. Panel E, histologic image showing severe restenosis with approximately 80% cross-sectional luminal narrowing, a postmortem clot (asterisk) is seen in the lumen. Panel F, a higher power image within the black box in E showing chronic inflammation and angiogenesis around stent struts.

Figure 7. Drug-eluting coronary Cypher™ stent at 4 months after implantation.

Panel A, shows a radiograph of a well-expanded Cypher™ stent. Panel B, the cross sectional image shows minimal neointimal coverage over stent struts. Panels C and D, higher magnifications of the regions represented by the respective black boxes in B showing inflammatory cells around stent struts consisting of giant cells (*), lymphocytes (inset in panel C), and eosinophils (inset in panel D, arrows). Panels B to C are Movat Pentachrome stains, the insets are hematoxylin and eosin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators N. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, Zheng ZJ, Flegal K, O'Donnell C, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, Goff DC, Jr, Hong Y, Adams R, Friday G, Furie K, Gorelick P, Kissela B, Marler J, Meigs J, Roger V, Sidney S, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wilson M, Wolf P. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113:e85–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr S, Farb A, Pearce WH, Virmani R, Yao JS. Atherosclerotic plaque rupture in symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23:755–765. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)70237-9. discussion 765–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spagnoli LG, Mauriello A, Sangiorgi G, Fratoni S, Bonanno E, Schwartz RS, Piepgras DG, Pistolese R, Ippoliti A, Holmes DR., Jr Extracranial thrombotically active carotid plaque as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Jama. 2004;292:1845–1852. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gronholdt ML, Nordestgaard BG, Schroeder TV, Vorstrup S, Sillesen H. Ultrasonic echolucent carotid plaques predict future strokes. Circulation. 2001;104:68–73. doi: 10.1161/hc2601.091704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatsukami TS, Ross R, Polissar NL, Yuan C. Visualization of fibrous cap thickness and rupture in human atherosclerotic carotid plaque in vivo with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2000;102:959–964. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, van der Baan A, Grosveld F, Daemen MJ, Krams R, de Crom R. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation. 2006;113:2744–2753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glagov S, Zarins C, Giddens DP, Ku DN. Hemodynamics and atherosclerosis. Insights and perspectives gained from studies of human arteries. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988;112:1018–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, Fuster V, Glagov S, Insull W, Jr, Rosenfeld ME, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1995;92:1355–1374. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Glagov S, Guyton JR, Insull W, Jr, Rosenfeld ME, Schaffer SA, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of initial, fatty streak, and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1994;89:2462–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arbustini E, Grasso M, Diegoli M, Pucci A, Bramerio M, Ardissino D, Angoli L, de Servi S, Bramucci E, Mussini A, et al. Coronary atherosclerotic plaques with and without thrombus in ischemic heart syndromes: a morphologic, immunohistochemical, and biochemical study. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:36B–50B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90383-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farb A, Burke AP, Tang AL, Liang TY, Mannan P, Smialek J, Virmani R. Coronary plaque erosion without rupture into a lipid core. A frequent cause of coronary thrombosis in sudden coronary death. Circulation. 1996;93:1354–1363. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.7.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Wal AC, Becker AE, van der Loos CM, Das PK. Site of intimal rupture or erosion of thrombosed coronary atherosclerotic plaques is characterized by an inflammatory process irrespective of the dominant plaque morphology. Circulation. 1994;89:36–44. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Schwartz SM. Lessons from sudden coronary death: a comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1262–1275. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velican C. A dissecting view on the role of the fatty streak in the pathogenesis of human atherosclerosis: culprit or bystander? Med Interne. 1981;19:321–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang YH, Smialek J, Virmani R. Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1276–1282. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705013361802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies MJ, Thomas AC. Plaque fissuring--the cause of acute myocardial infarction, sudden ischaemic death, and crescendo angina. Br Heart J. 1985;53:363–373. doi: 10.1136/hrt.53.4.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falk E, Shah PK, Fuster V. Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 1995;92:657–671. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li ZY, Howarth SP, Tang T, Gillard JH. How critical is fibrous cap thickness to carotid plaque stability? A flow-plaque interaction model. Stroke. 2006;37:1195–1199. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217331.61083.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng GC, Loree HM, Kamm RD, Fishbein MC, Lee RT. Distribution of circumferential stress in ruptured and stable atherosclerotic lesions. A structural analysis with histopathological correlation. Circulation. 1993;87:1179–1187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vengrenyuk Y, Carlier S, Xanthos S, Cardoso L, Ganatos P, Virmani R, Einav S, Gilchrist L, Weinbaum S. A hypothesis for vulnerable plaque rupture due to stress-induced debonding around cellular microcalcifications in thin fibrous caps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14678–14683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606310103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Farb A, Weber DK, Malcom GT, Smialek J, Virmani R. Healed plaque ruptures and sudden coronary death: evidence that subclinical rupture has a role in plaque progression. Circulation. 2001;103:934–940. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann J, Davies MJ. Mechanisms of progression in native coronary artery disease: role of healed plaque disruption. Heart. 1999;82:265–268. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avril G, Batt M, Guidoin R, Marois M, Hassen-Khodja R, Daune B, Gagliardi JM, Le Bas P. Carotid endarterectomy plaques: correlations of clinical and anatomic findings. Ann Vasc Surg. 1991;5:50–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02021778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kragel AH, Reddy SG, Wittes JT, Roberts WC. Morphometric analysis of the composition of atherosclerotic plaques in the four major epicardial coronary arteries in acute myocardial infarction and in sudden coronary death. Circulation. 1989;80:1747–1756. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.6.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke AP, Taylor A, Farb A, Malcom GT, Virmani R. Coronary calcification: insights from sudden coronary death victims. Z Kardiol. 2000;89 (Suppl 2):49–53. doi: 10.1007/s003920070099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer JW, Steitz SA, Johnson PY, Burke A, Kolodgie F, Virmani R, Giachelli C, Wight TN. Decorin promotes aortic smooth muscle cell calcification and colocalizes to calcified regions in human atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2391–2396. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147029.63303.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu B, Kampschulte A, Ferguson MS, Kerwin WS, Yarnykh VL, O'Brien KD, Polissar NL, Hatsukami TS, Yuan C. Hemorrhage in the atherosclerotic carotid plaque: a high-resolution MRI study. Stroke. 2004;35:1079–1084. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125856.25309.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolodgie FD, Gold HK, Burke AP, Fowler DR, Kruth HS, Weber DK, Farb A, Guerrero LJ, Hayase M, Kutys R, Narula J, Finn AV, Virmani R. Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2316–2325. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu B, Saam T, Polissar NL, Jarvik GP, Isaac C, McDonough J, Natiello C, Small R, Ferguson MS, Hatsukami TS. Presence of intraplaque hemorrhage stimulates progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation. 2005;111:2768–2775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Finn AV, Gold HK, Tulenko TN, Wrenn SP, Narula J. Atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability to rupture: angiogenesis as a source of intraplaque hemorrhage. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2054–2061. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000178991.71605.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bornstein NM, Krajewski A, Lewis AJ, Norris JW. Clinical significance of carotid plaque hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:958–959. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530090028008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imparato AM. The carotid bifurcation plaque--a model for the study of atherosclerosis. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mofidi R, Crotty TB, McCarthy P, Sheehan SJ, Mehigan D, Keaveny TV. Association between plaque instability, angiogenesis and symptomatic carotid occlusive disease. Br J Surg. 2001;88:945–950. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galili O, Herrmann J, Woodrum J, Sattler KJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Adventitial vasa vasorum heterogeneity among different vascular beds. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aydin F. Do human intracranial arteries lack vasa vasorum? A comparative immunohistochemical study of intracranial and systemic arteries. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1998;96:22–28. doi: 10.1007/s004010050856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takaba M, Endo S, Kurimoto M, Kuwayama N, Nishijima M, Takaku A. Vasa vasorum of the intracranial arteries. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140:411–416. doi: 10.1007/s007010050118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gruntzig AR, Senning A, Siegenthaler WE. Nonoperative dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197907123010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Wong C, Hong MK, Kovach JA, Leon MB. Arterial remodeling after coronary angioplasty: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 1996;94:35–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan TJ, Bauman WB, Kennedy JW, Kereiakes DJ, King SB, 3rd, McCallister BD, Smith SC, Jr, Ullyot DJ. Guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. A report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Task Force on Assessment of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Cardiovascular Procedures (Committee on Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty) Circulation. 1993;88:2987–3007. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serruys PW, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F, Macaya C, Rutsch W, Heyndrickx G, Emanuelsson H, Marco J, Legrand V, Materne P, et al. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. Benestent Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:489–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Farb A, Lafont A. Drug eluting stents: are human and animal studies comparable? Heart. 2003;89:133–138. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farb A, Sangiorgi G, Carter AJ, Walley VM, Edwards WD, Schwartz RS, Virmani R. Pathology of acute and chronic coronary stenting in humans. Circulation. 1999;99:44–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farb A, Weber DK, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Virmani R. Morphological predictors of restenosis after coronary stenting in humans. Circulation. 2002;105:2974–2980. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000019071.72887.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson PG, Bajaj RK, Baxley WA, Roubin GS. Vascular pathology of balloon-expandable flexible coil stents in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:372–381. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, Mont EK, Kolodgie FD, Ladich E, Kutys R, Skorija K, Gold HK, Virmani R. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kastrati A, Schomig A, Elezi S, Schuhlen H, Dirschinger J, Hadamitzky M, Wehinger A, Hausleiter J, Walter H, Neumann FJ. Predictive factors of restenosis after coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1428–1436. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Popma JJ, Califf RM, Topol EJ. Clinical trials of restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Circulation. 1991;84:1426–1436. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.3.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lincoff AM, Furst JG, Ellis SG, Tuch RJ, Topol EJ. Sustained local delivery of dexamethasone by a novel intravascular eluting stent to prevent restenosis in the porcine coronary injury model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:808–816. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carter AJ, Aggarwal M, Kopia GA, Tio F, Tsao PS, Kolata R, Yeung AC, Llanos G, Dooley J, Falotico R. Long-term effects of polymer-based, slow-release, sirolimus-eluting stents in a porcine coronary model. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drachman DE, Edelman ER, Seifert P, Groothuis AR, Bornstein DA, Kamath KR, Palasis M, Yang D, Nott SH, Rogers C. Neointimal thickening after stent delivery of paclitaxel: change in composition and arrest of growth over six months. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2325–2332. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farb A, Heller PF, Shroff S, Cheng L, Kolodgie FD, Carter AJ, Scott DS, Froehlich J, Virmani R. Pathological analysis of local delivery of paclitaxel via a polymer-coated stent. Circulation. 2001;104:473–479. doi: 10.1161/hc3001.092037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rogers C, Karnovsky MJ, Edelman ER. Inhibition of experimental neointimal hyperplasia and thrombosis depends on the type of vascular injury and the site of drug administration. Circulation. 1993;88:1215–1221. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sousa JE, Costa MA, Abizaid A, Abizaid AS, Feres F, Pinto IM, Seixas AC, Staico R, Mattos LA, Sousa AG, Falotico R, Jaeger J, Popma JJ, Serruys PW. Lack of neointimal proliferation after implantation of sirolimus-coated stents in human coronary arteries: a quantitative coronary angiography and three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2001;103:192–195. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, Fajadet J, Ban Hayashi E, Perin M, Colombo A, Schuler G, Barragan P, Guagliumi G, Molnar F, Falotico R. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773–1780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O'Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, Hermiller J, O'Shaughnessy C, Mann JT, Turco M, Caputo R, Bergin P, Greenberg J, Popma JJ, Russell ME. A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:221–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki T, Kopia G, Hayashi S, Bailey LR, Llanos G, Wilensky R, Klugherz BD, Papandreou G, Narayan P, Leon MB, Yeung AC, Tio F, Tsao PS, Falotico R, Carter AJ. Stent-based delivery of sirolimus reduces neointimal formation in a porcine coronary model. Circulation. 2001;104:1188–1193. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.093987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guagliumi G, Farb A, Musumeci G, Valsecchi O, Tespili M, Motta T, Virmani R. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Sirolimus-eluting stent implanted in human coronary artery for 16 months: pathological findings. Circulation. 2003;107:1340–1341. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000062700.42060.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, Musumeci G, Grieco N, Motta T, Mihalcsik L, Tespili M, Valsecchi O, Kolodgie FD. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus-eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation. 2004;109:701–705. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116202.41966.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finn AV, Kolodgie FD, Harnek J, Guerrero LJ, Acampado E, Tefera K, Skorija K, Weber DK, Gold HK, Virmani R. Differential response of delayed healing and persistent inflammation at sites of overlapping sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation. 2005;112:270–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.508937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abou-Chebl A, Bashir Q, Yadav JS. Drug-eluting stents for the treatment of intracranial atherosclerosis: initial experience and midterm angiographic follow-up. Stroke. 2005;36:e165–168. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190893.74268.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gupta R, Al-Ali F, Thomas AJ, Horowitz MB, Barrow T, Vora NA, Uchino K, Hammer MD, Wechsler LR, Jovin TG. Safety, feasibility, and short-term follow-up of drug-eluting stent placement in the intracranial and extracranial circulation. Stroke. 2006;37:2562–2566. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000242481.38262.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carotid surgery versus medical therapy in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. The CASANOVA Study Group. Stroke. 1991;22:1229–1235. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carotid endarterectomy for patients with asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1995;129:76–77. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yadav JS. Carotid stenting in high-risk patients: design and rationale of the SAPPHIRE trial. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71 (Suppl 1):S45–46. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.suppl_1.s45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chakhtoura EY, Hobson RW, 2nd, Goldstein J, Simonian GT, Lal BK, Haser PB, Silva MB, Jr, Padberg FT, Jr, Pappas PJ, Jamil Z. In-stent restenosis after carotid angioplasty-stenting: incidence and management. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:220–225. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.111880. discussion 225–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lal BK, Hobson RW., 2nd Management of carotid restenosis. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2006;47:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wholey MH, Wholey M, Bergeron P, Diethrich EB, Henry M, Laborde JC, Mathias K, Myla S, Roubin GS, Shawl F, Theron JG, Yadav JS, Dorros G, Guimaraens J, Higashida R, Kumar V, Leon M, Lim M, Londero H, Mesa J, Ramee S, Rodriguez A, Rosenfield K, Teitelbaum G, Vozzi C. Current global status of carotid artery stent placement. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1998;44:1–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0304(199805)44:1<1::aid-ccd1>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buhk JH, Wellmer A, Knauth M. Late in-stent thrombosis following carotid angioplasty and stenting. Neurology. 2006;66:1594–1596. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216141.01262.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]