Abstract

Passive immunization strategies are under widespread investigation as potential disease-modifying therapies for AD. The development of and interest in passive immunization strategies for AD stemmed from a search for safer methods of delivering immunotherapy following the initial results of active vaccination with AN-1792, which led to the development of meningoencephalitis in 6% of vaccinated subjects in this trial. Current approaches based on promising data demonstrating behavioral improvement and reduced pathology in transgenic animal models of AD have focused exclusively on the immune targeting of β-amyloid. Preliminary results from three phase II trials of passive immunization were recently reported at the 2008 International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease suggest both promise and the need to exercise caution with this “safer” method of immunotherapy for AD. The antibody strategies used in each of these trials were distinct, using monoclonal N-terminal, central epitope, and polyclonal strategies in an effort to maximize the efficacy and safety of each approach. The tested compounds are all moving into phase III human trials of mild to moderate AD currently. We anxiously await the exciting discoveries that may come from the currently active phase III studies that may help yield the first disease modifying therapy for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, passive immunization, amyloid

1.0 Introduction

Passive immunization strategies have been widely pursued as a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease (AD).[1–16]Spurred by a quest for disease modifying therapies as an alternative to symptomatic treatments, vaccination has been an attractive candidate approach for use in AD.[1, 3, 6, 11, 12, 14–19] Yet, recent data call into question the utility of immunotherapy, highlights our limited understanding of how such immunological strategies may affect AD, and present us all with a dilemma in interpreting the risk-benefit ratio of such approaches.[1, 3, 6, 7, 14–30]

Immunization strategies for AD to present have been based largely on targeting β-amyloid (Aβ), however such approaches may prove beneficial targeting other molecules involved in the pathogenesis of AD.[12, 31]The focus on Aβ has been largely influenced by the “amyloid cascade hypothesis” and by the ready availability of transgenic mouse models of Aβ deposition.[1–4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 14–17, 32, 33]The disappointing results of recent treatment trials have called into question the presumed centrality of Aβ in the development of AD and its potential as a therapeutic target.[34, 35] Many have touted the “death” of the “amyloid hypothesis” on the basis of these recent clinical trial data. The amyloid hypothesis is clearly not “dead and buried”, but rather remains one of the most active areas of AD research today.[33, 36–38]

2.0 Active Immunization in Human AD

Early studies demonstrating decreased Aβ burden and improved behavioral outcomes in transgenic animals actively immunized with Aβ led to the first human clinical trial of active immunization for AD.[22, 39–41]Early phase I results with the Elan AN-1792 vaccine led to a larger-scale phase II trial.[22]The development of aseptic meningoencephalitis in 6% of immunized subjects led to a cessation of the clinical trial and a reassessment of the risk/benefit profile of such interventions.[20, 22, 28, 29]These results were instrumental in the development and implementation of passive immunization protocols in AD research today. The full details of the AN-1792trials are published elsewhere, but the findings of relevance to the topic of passive immunization are as follows.[20–23, 26, 28, 29, 42]

Significant antibody responses were seen in only 19.7% of the immunized subjects, with a predominant immune response against N-terminal epitopes of Aβ.[22, 24]While definitive evidence of primary clinical efficacy was lacking, secondary clinical efficacy was evident on several measures.[22] CSF analyses in a subset of subjects showed a significant decrease in total tau measures but no effect on CSF Aβ42 levels.[22]Structural MRI studies revealed significant decreases in total brain volume in the treated subjects over controls that were not expected and remain to be explained.[21]

Neuropathological evaluation in a subset of cases that developed meningoencephalitis demonstrated perivascular T-cell and mononuclear cell infiltrates.[20, 28, 29]Irrespective of meningoencephalitis, the autopsied cases demonstrated significantly less Aβ deposition compared to control AD cases.[23, 26, 28]Despite a decreased Aβ load in these subjects, the majority (7/8) subjects in a recent series developed end stage clinical disease in a similar time frame expected for untreated AD cases.[23]

While many of these findings remain poorly understood, the active immunization strategy clearly influenced the disease state pathologically. While the debate over whether the achieved biological alterations represented an overall worsening or improvement in the disease state (outside the cases exhibiting meningoencephalitis), the AN-1792 trial was the first to demonstrate clearly that disease modification is possible.[1, 6, 11, 14, 16, 17, 21–23, 26, 43]The excitement and enthusiasm of such a breakthrough propelled the search for safer strategies forward, leading to our present discoveries in the area of passive immunization for AD.

3.0 Passive Immunization in Animal Models of AD

Passive immunization targeting Aβ results in improved performance on behavioral measures and reduced plaque pathology in transgenic animal models of AD.[3, 6, 27, 40, 43–51]These effects are universally seen across studies using a variety of antibodies that differ significantly in terms of antigenic binding sites and the ability to recognize different forms of Aβ.[3, 6, 27, 40, 43–51]The effects are more rapid (within one day of injection) than one would expect if the mechanism of action was simple removal of existing plaques.[6]This finding suggests that immunization strategies may work through mechanisms of Aβ binding not clearly related to overt plaque removal. The existence and importance of early soluble or prefibrillar Aβ has emerged as a dominant hypothesis for neuronal dysfunction in the pathogenesis of AD, partly on the basis of these observations.[33, 52–54]Such forms of Aβ have recently been demonstrated to play a potential role in synaptic dysfunction and disruption of long term potentiation involved in the production of short term memories.[52–54] It is hypothesized, but not yet proven that such early soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ may precede overt neuronal death and the development of AD.[52–54]If true, than removal of such species of Aβ would be important for modification of the biological disease process leading to AD.

Studies of passive immunization in transgenic AD mice argue against significant CNS penetration (only 0.02–1.5% total antibody is distributed in the CNS), and the net effect of passive immunization is expected to clear only 3–4% of the Aβ produced daily.[6, 25, 55]Such calculations imply that the efficacy of passive immunization strategies in AD may involve more complex mechanisms of biological action than can be accounted for by direct removal of Aβ from the CNS.

Passive immunization appears remarkably safe using these animal model systems. Preliminary reports of meningoencephalitis are absent in the majority of these studies. [3, 6, 27, 40, 43–51]The occurrence of menigoencephalitis in animal models of AD treated with passive immunization strategies has been described, occurring at low frequency (only 1/21 animals in the initial report).[56] The inflammatory response was both similar and dissimilar to that seen in the AN-1792 trial subjects. Inflammatory infiltrates were seen in the meninges and perivascular regions in areas of active Aβ deposition that were devoid of polymorphonuclear cells indicating a chronic rather than acute process similar to the findings inAN-1792 subjects.[56] A more detailed analysis of the lymphocytic infiltrates indicated a predominant B-cell mediated response rather than the T-cell response in human AN-1792 subjects.[56]The authors speculated that the T-cell response was delayed, related to the presence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), or that local disruption of the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) may have led to a localized humoral response.[56]

Several studies have also reported intracerebral microbleeds using passive immunization strategies in animal models of AD.[57–62]These findings have been proposed to result from either inflammatory disruption of the cerebral vasculature, perturbation of preexisting amyloid angiopathy, or the effects of newly deposited amyloid in the vasculature as a result of increased intracerebral antibody-mediated clearance mechanisms.[57–62]Adverse events such as these will clearly have to be monitored for in all ongoing and future human clinical trials of passive immunization in AD.

4.0 How do Passive Immunization Strategies Work in AD?

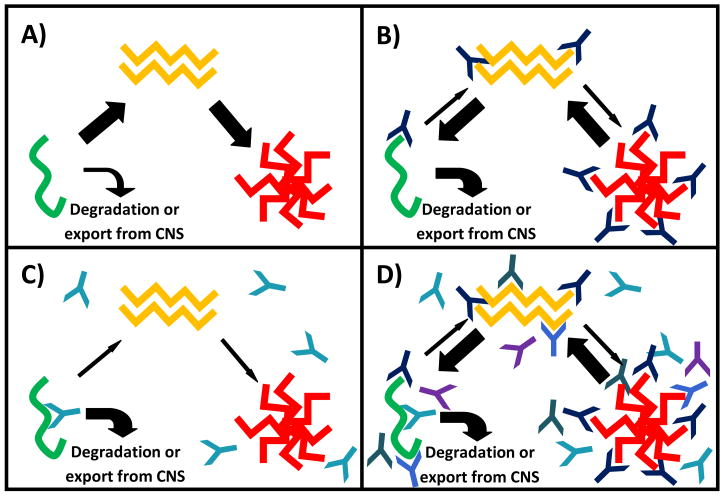

The mechanisms whereby passive immunization with antibodies that bind Aβ may influence AD remain speculative at present, but are based on our understanding of the varied molecular and macromolecular forms of Aβ that may serve as targets for immunotherapy in AD.[1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 15, 16, 36, 54] Cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein by β-and γ-secretase releases a monomeric form of Aβ that can aggregate to form soluble oligomeric Aβ (Figure 1a) which has been shown to negatively influence synaptic function in vitro and in animal models of AD.[10, 33, 36,52, 54]Further aggregation of oligomeric Aβ involves the adoption of a β-pleated sheet structure, insolubility, and parenchymal deposition resulting in the formation of extracellular parenchymal Aβ plaque deposition (Figure 1a).[10, 33, 36, 54] Aβ plaques may affect neuronal viability and function through direct toxic effects on neurons, initiation or augmentation of the molecular processes involved in neurofibrillary tangle formation, and or triggering and perpetuation of central nervous system inflammation in AD.[10, 33, 36, 54] The molecular transitions from soluble monomeric, to oligomeric, to insoluble deposited Aβ involve secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structural changes that can either mask epitopes or create new antigenic targets at each step of this process.[10, 33, 36, 54]As such the dynamic nature of Aβ immunogenicity provides a wealth of targets at each step of this process that may influence neuronal survival and function through specific perturbation of the amyloid cascade.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the a) molecular and macromolecular transitional states of Aβ and b–d) how they may be influenced by specific passive immunization strategies: a) monomeric Aβ (green) may be either degraded or aggregate to form soluble oligomeric Aβ species (yellow). Soluble oligomeric Aβ aggregates further leading to the deposition of insoluble parenchymal Aβ plaques in the brains of persons with Alzheimer’s disease; b) Antibodies recognizing N-terminal epitopes on Aβ bind to soluble monomeric, oligomeric and insoluble deposited Aβ species presumably shifting the equilibrium from plaque formation to degradation or export from the CNS; c) Antibodies recognizing central epitopes on Aβ recognize soluble monomeric Aβ, but as aggregation occurs, the epitope is hidden preventing binding to soluble oligomeric and insoluble deposited Aβ, enhancing the degradation or removal of monomeric Aβ from the CNS and decreasing the formation of both soluble oligomeric and insoluble deposited Aβ; d) Polyclonal antibody preparations bind multiple antigenic targets on all three transitional forms of Aβ, shifting the equilibrium from plaque formation to degradation or export from the CNS.

The present review focuses on three distinct Aβ targeting mechanisms that are currently being evaluated in phase III trials of passive immunization in AD: 1) antibodies targeting N-terminal epitopes present in all molecular and macromolecular forms of Aβ, 2) antibodies recognizing central primary sequence epitopes, masked by the transition to oligomeric or aggregated forms of Aβ, and 3) polyclonal antibodies recognizing a potential wealth of epitopes across the many diverse species and transitional forms of Aβ characterizing AD (Figure 1). The data derived from the use of these overlapping, yet distinct, passive immunization strategies in human AD may yield valuable insights into the pathogenesis of AD above and beyond their elucidation as possible therapeutic agents in this devastating disease.

4.1 “Peripheral Sink” Hypothesis

Several disparate hypotheses exist regarding the mechanism of action for passive immunization in AD as described above. The lack of significant antibody penetrance into the CNS suggests mediation through peripheral rather than central mechanisms.[6, 46, 55, 63]This has led to the hypothesis of the “peripheral sink” which proposes that the presence of circulating immunoglobulin in the periphery draws Aβ species out of the CNS, allowing degradation and elimination, which in turn abrogates the disease process in the CNS(Figure 1c).[46]This mechanism of action is postulated for all three antibody strategies discussed in this review, however, the therapeutic efficacy of m266 (Eli Lilly & Co.) which recognizes a central primary sequence epitope on Aβ, masked by the formation of oligomeric and insoluble aggregated forms of Aβ may provide the best information on the efficacy of such a strategy for treatment of AD. m266 (Eli Lilly & Co.) is currently entering phase III clinical testing in AD and may serve as the ultimate test for the “peripheral sink” hypothesis as it is devoid of reactivity for both soluble oligomeric and deposited insoluble Aβ plaques.[64]

4.2 N-terminal Aβ antibodies

Still others argue that direct binding and antibody-mediated dissolution of Aβ plaques and CAA may be most helpful. This is best accomplished by antibodies targeting the N-terminus of Aβ that most avidly recognize these pathological features of the disease process. The most dramatic results in animal models to date have utilized this approach and further investigations are clearly warranted. N-terminal reactive antibodies are not selective for deposited Aβ plaques, but also react with soluble oligomeric and monomeric forms of Aβ (Figure 1b). As such, they may influence the disease state through either inactivation of the harmful properties of soluble oligomeric Aβ or through the peripheral sink mechanism described above. Bapineuzimab (Elan/Wyeth) is the prototypic antibody of this class, and has been moved into phase III clinical trial status.[65]

4.3 Polyclonal strategies

Other strategies have been developed based on the concept of the multivalent or polyclonal approach to passive immunization. Such antibody preparations include antigenic targets that may span the Aβ molecule and all its transitional and aggregated forms(Figure 1d). As such, the molecular mechanisms of action include dissolution of Aβ plaques, inactivation of soluble oligomeric Aβ, and removal of Aβ through a peripheral sink. The collaborative Baxter Inc. and Alzheimer Cooperative Study Group initiative to bring human-derived, pooled immunoglobulin (IGIV) into phase II human clinical trials rests on the discovery of naturally occurring Aβ antibodies in these preparations. The polyclonal composition and naturally-derived epitope selection in IVIg are argued to be the key strengths of this approach.[13, 66, 67]

5.0 Passive Immunization in Human AD

Preliminary reports from phase I and II human clinical trials using passive immunization strategies have been reported by Eli Lilly & Co., Elan-Wyeth, and Baxter Inc.[64, 65, 67, 68]The agents in these trials share in common the passive immunization strategy, yet they differ in many ways. An understanding of the clinical trial data, including an analysis of comparative efficacy and safety profiles, may provide valuable clues leading to the development of an optimal passive and potentially active immunization strategy for AD. The International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease (ICAD) 2008 served as a forum for the dissemination on the latest clinical trial data from each of these studies.

5.1 LY2062430 and the “Peripheral Sink” Hypothesis Tested

The human phase II trial by Eli Lilly investigated m266, recognizing a central epitope on Aβ (LY2062430), in a small group of just 52 patients over a 12 week study period.[64]The trial focused on safety and biomarker outcomes needed to guide phase III studies. Four treatment groups received doses of LY2062430that varied based on dose (100 vs. 400 mg) and frequency of administration (weekly vs. every 4 weeks) and a fifth group served as the control.[64]No adverse events attributed to the treatment were seen in any of the subjects over the short course of the trial and a more extended 1 year followup period.[64]Plasma elevations of Aβ increased dramatically post injection, reinforcing the presumed role of LY2062430 as a peripheral sink.[64]Significant increases in CSF Aβ42 (200 pg/ml) and decreases in Aβ40 (3,000 pg/ml) were seen as well, suggesting a central mechanism of action in addition to or as a result of the peripheral effects of LY2062430 although this remains to be proven.[64]Further biochemical characterization revealed that truncated Aβ fragments (Aβ3-42 and an unidentified species, fragment 2) were the predominant central target of LY2062430.[64]These species are hypothesized to be early aggregating forms of Aβ, suggesting that LY2062430 altered the equilibrium between certain peripheral and central Aβ species that may influence the disease process. Little clinical data was provided, although with such a small sample size and short study period the data would have been most likely unrevealing.

5.2 Bapineuzimab Results

The phase II trial of Elan/Wyeth Bapineuzimab was conducted on 234 subjects that received injections every 13 weeks for a total trial period of 78 weeks.[65]Safety data revealed that 12 of the treated subjects developed vasogenic edema during the protocol.[65]Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele frequency (83%) was higher in this group than in the general study population (66%).[65] The potential influence of ApoE genotype on the occurrence of SAEs in this study has led to modification of the dosing parameters in the ongoing phase III trial of this agent.[65]

Primary clinical outcomes showed trends towards efficacy evaluated by the ADAS-Cognitive component(Cog)(p=0.078) and neuropsychological test battery (NTB) (p=0.068) but failed to meet statistical significance.[65]Post-hoc analyses that drew attention included both a “completers” analysis of 78 subjects who received all injections and showed significant improvement on the ADAS-Cog (p=0.003), and a between group analysis of ApoE ε4 carriers and non carriers which suggested that the benefits of bapineuzimab might be limited to the non-carriers alone(ADAS-Cog p=0.026 and NTB, p=0.006).[65]Importantly, the post-hoc analyses were neither planned nor powered to assess efficacy in the current trial, therefore the results are open to question. Biomarker analyses revealed a trend towards lowered CSF tau (a marker of neuronal loss) in the treated vs. placebo group in a subset of patients (n=35, p=0.056).[65]Volumetric MRI analyses showed conflicting results based on ApoE carrier status. ApoE ε4 carriers showed evidence of increased ventricular volume (surrogate for decreased cerebral volume), while non-carriers showed a trend for decreased brain atrophy.[65]While definitive primary clinical and biomarker efficacy was not proved by this trial, favorable trends across measures supported the decision to move ahead with the planned phase III studies.

5.3 IVIg in AD

Phase I data on the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) has been reported for the 8 mild AD patients enrolled in this study.[67]This approach used pooled human immunoglobulin preparations that contain anti-Aβ activity.[9, 13, 66] This preparation is polyclonal, although an argument has been made for selective recognition of soluble oligomeric Aβ.[9, 13, 66]This study was originally designed as an open-label(subjects and study personnel were aware that all were receiving the active agent), 6 month treatment followed by a 3 month washout period.[67]The strong efficacy signal detected in the original treatment period led to modification of the trial design to include an additional 9 month treatment period. IVIg infusion was shown to increase serum anti-Aβ titers in all subjects.[67]The study also demonstrated a dose response relationship between increasing study drug and increased serum Aβ levels.[67]CSF Aβ levels showed an inverse relationship with study drug, dropping significantly from baseline values during the active treatment periods.[67]Folstein Minimental State examination (MMSE) scores increased in 6 subjects over the initial 6 month infusion period while two subjects remained stable.[67]At the end of the full 18 month trial period, 5 subjects had MMSE scores above baseline values,1 remained stable, and 2 subjects showed evidence for decline despite active treatment with IVIg.[67]No serious adverse events including meningoencephalitis or intracerebral hemorrhage were seen.[67]

Dr. Relkin’s phase II trial of the Baxter product Gammaguard also made headlines at ICAD 2008.[68]Only 24 subjects were enrolled in the phase II study. Sixteen subjects received active treatment(four dosing groups) and eight received placebo. The trial involved a 24-week study period followed by a crossover of placebo subjects to active treatment. Nine month interim data showed statistical improvement on primary outcome measures including ADAS-Cog and ADAS-Clinical global impression of change.[68]Secondary outcome measures included ADAS-Activities of daily living scales, global cognitive measures, CSF analyses, FDG-PET, PIB-PET, and PK11195-PET to assess microglial activation.[68]The results of these secondary analyses have not been reported. The phase III trial is starting currently.

6.0 Expert opinion

6.1 Novel Approaches for Passive Immunization

Passive immunization technologies are currently being developed to overcome many of the issues raised by the AN-1792 trialand early work in the area of passive immunization.[6, 7, 20, 21, 23, 28, 29, 56, 61, 69]The development of multivalent vaccines targeting multiple epitopes on the same molecule, or perhaps even multiple components of a disease pathway (i.e. β-amyloid and tau in combination?) may allow both a stronger, more complete immune response.[1, 4, 6, 14–16, 18, 19, 31, 70]Technology allowing the production of antibody fragments with biological activity have also been developed that may help to enhance CNS penetration and limit the possibility of polyeffector immune-mediated responses such as cytokine and complement cascade induction as well as T-cell responses that may not be desired in a particular immunization strategy.[6, 63, 71, 72] Such strategies for the development of new passive immunization protocols for AD clearly have scientific plausibility, and are currently in development, although human clinical trials using such agents have not been reported in the literature or posted on clinical trials websites to date.

6.2 Mechanisms of Vasogenic Edema

The development of vasogenic edema in 5% of the Bapineuzimab study group is worrisome, paralleling the incidence of menigoencephalitis at 6% in the AN-1792 trial.[22, 65]While aberrant activation of a T-cell response was largely presumed to be responsible for the occurrence of meningoencephalitis in the original AN-1792 trial, this is an unlikely explanation for the results of the current passive immunization trial.[6, 20, 22, 28, 29]The existing animal data in passive immunization paradigms demonstrating a largely posterior distribution of these findings that coincide with the distribution of CAA in human AD, instead suggests that interactions between antibody and CAA may be responsible for the presence of edema seen on MRI in these regions.[6, 20, 22, 28, 29, 61, 73–75]The underlying pathology may well represent an active menigoencephalitis or may simply reflect reversible vasogenic edema. While there is no current evidence supporting a pathological diagnosis of meningoencephalitis in human subjects receiving passive vaccination, such findings have been reported in animal studies. [56, 57]In addition, the imaging studies presented from the phase II studies of Bapineuzimab at ICAD 2008 bear a striking resemblance to the scans derived from subjects enrolled in the AN-1792 trial that developed pathologically-proven meningoencephalitis. Alternatively, the edema seen may be nonspecific. Several reports in the literature have demonstrated the presence of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy in subjects receiving immunotherapy for a variety of conditions.[76–80]

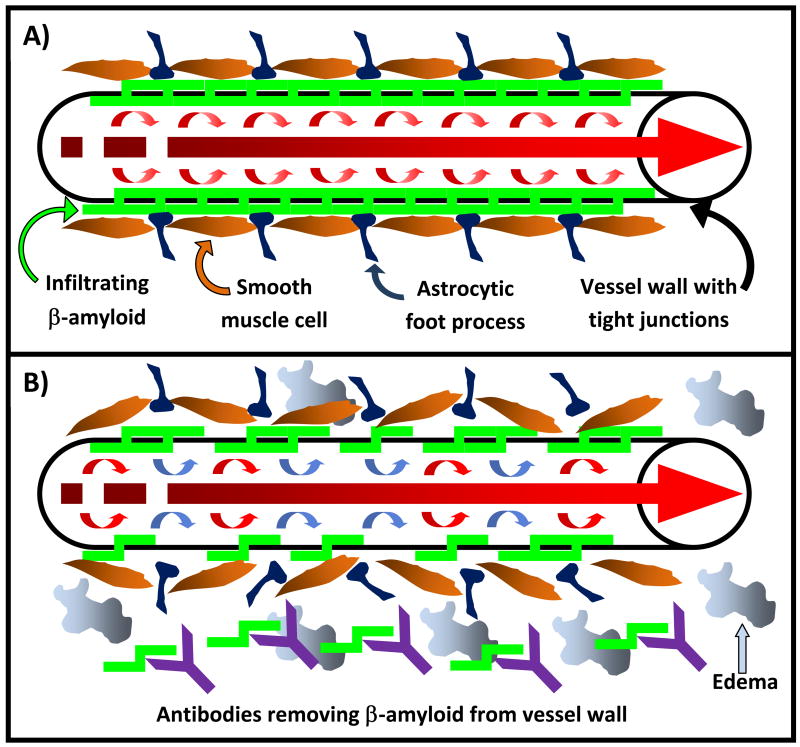

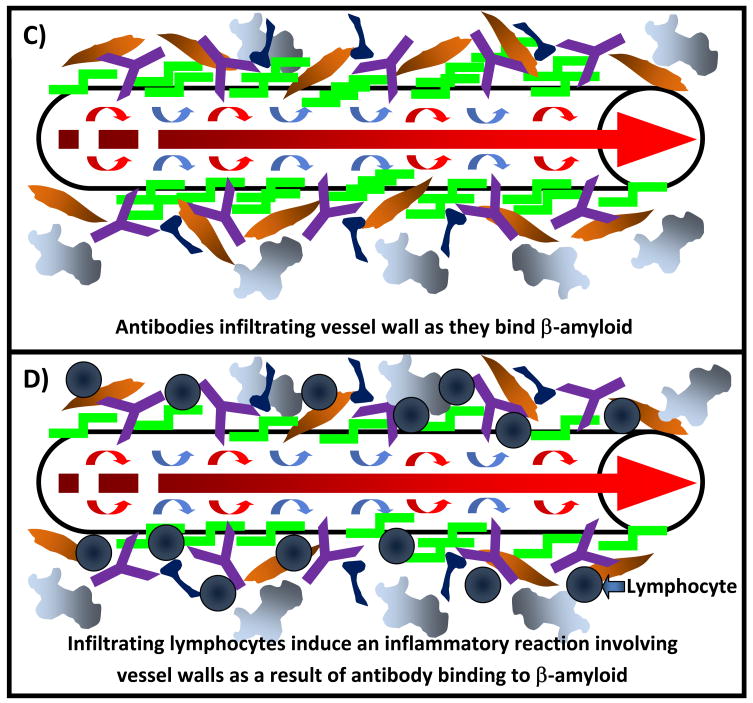

Mechanisms of vasogenic edema could include disruption of vascular integrity through antibody-mediated removal of Aβ in vessel walls, antibody or antibody-Aβ infiltration of vessel walls as a result of enhanced antibody clearance or an activated peripheral sink mechanism, or the initiation of vascular inflammatory cascades through vessel-bound antibody mediated stimulation of the central immune response (Figure 2).[6, 56, 57, 59, 62, 74]The precise mechanism whereby this occurs is unknown. Data from studies investigating passive immunotherapy in a variety of non-AD conditions suggest that the occurrence of vasogenic edema is non-specific, may not be directly related to specific immune targeting of Aβ, and may be important for safety monitoring of any passive immunization strategy in AD irrespective of the antibody used.[76–81]Pathological examination of such cases through biopsy or autopsy will be needed to definitively identify the cause for such occurrences in human AD and answer this important question.

Figure 2.

Possible mechanisms of cerebral edema or vascular hemorrhage as a result of passive immunization strategies against Aβ: a) Schematic representation of an Aβ-laden arteriole in Alzheimer’s disease. Edema and or vascular hemorrhage may be caused by disruption of vascular integrity through b) the removal of deposited Aβ, c) infiltration of antibody as it binds Aβ in the vessel wall, d) an inflammatory reaction mediated by antibody binding to vascular Aβ and subsequent infiltration of inflammatory cells and other mediators of inflammation, or may involve a combination of any of the above postulated mechanisms.

6.3 Other Safety Concerns and Adverse Events

Other risks inherent in any antibody infusion protocol, including ischemic stroke, anaphylaxis, aseptic meningitis, intracerebral hemorrhage, posterior reversible encephalopathy, myocardial infarction, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, exacerbation of congestive heart failure, and acute renal failure are important considerations in evaluating the risk-benefit profile of passive immunization strategies.[76–90]Such adverse events are not uncommon irrespective of use in a wide variety of disease states. Many of these risks, including the risks of stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and myocardial infarction among others are increased in individuals with risk factors for underlying cardiovascular disease that are common comorbidities in the aged population with AD.[83, 86, 90]These risks cannot be ignored and clearly may influence the rational use of such agents in the general population irrespective of efficacy considerations derived from future clinical trial data. Such concerns are also important for research subjects that are currently being engaged world-wide for potential participation in clinical trials investigating passive immunization AD. Full disclosure of the risks of such protocols and avoidance of recruitment or enrollment of subjects predisposed to such adverse events is critical. Irrespective of the efficacy outcomes of the ongoing and future clinical trials of passive immunization strategies in AD, safety concerns will remain a significant focus of concern, and rightly so.

6.4 Unifying Themes and Distinct Therapeutic Approaches

The reasons for the variability in serious adverse events (SAEs), especially the occurrence of meningoencephalitis and intracerebral hemorrhage, seen between studies remains indeterminate in humans. It is possible that the relative lack of significant SAEs in the Lilly and Baxter trials may be due to the small number of highly selected subjects enrolled.[64, 68]The larger Elan/Wyeth study may provide more accurate assessment of the possible risks of passive immunization strategies in the population as a whole.[65]The clear demonstration across all three studies of a biological effect of these agents is extremely encouraging. Alterations in serum, CSF, and imaging biomarkers were clearly demonstrated in each of these studies, with the directionality of such trends consistent irrespective of the agent studied.[64, 65, 68]The results to date justify moving forward into phase III trials in an attempt to definitively examine the clinical efficacy of such agents in the treatment of AD.

6.5 Is Earlier Intervention Necessary for Efficacy?

Many in the field believe that the efficacy of such agents may be critically dependent on the disease state at the time the therapy is implemented.[38, 91–95]Intervention in the disease state prior to overt neuronal degeneration and the appearance of pathological features of the disease in widespread cortical regions may be necessary for maximal efficacy of such therapeutic strategies. Animal studies support such contentions.[96–98]Irrespective of the results in the ongoing phase III trials in mild to moderate AD, therapeutic trials in mild cognitive impairment may be important to pursue.[99–104]Secondary post-hoc analyses of the data obtained from the current and planned phase III trials in patient groups representing the mild vs. the more moderate subjects may shed light on such concerns and should be pursued. Certainly approaches such as the Eli Lilly Inc. LY2062430m266 antibody may have little utility in influencing the disease state once oligimeric Aβ and deposited Aβ plaques appear as these entities are not substrates for the therapeutic antibody. Similar considerations hold true for the N-terminal Bapineuzimab (Elan/Wyeth) and polyclonal (Baxter/ADCS) agents that may also show efficacy in the earliest stages of disease, but could prove ineffective once the disease has ravaged the CNS.

7.0 Conclusions

Those of us who research in the area of AD, treat or care for persons with AD, and those who suffer from this devastating disease all await the exciting discoveries that may come from the currently active phase III studies and further translational discoveries in the area of passive immunization that may help yield the first disease modifying therapy for AD. Caution is clearly warranted, given the results of the active AN-1792 trial and the preliminary results from the phase II studies of these agents.[22, 64, 65, 68]It should be noted that passive immunization is a strategy for intervention in AD not a discrete treatment paradigm. The multitude of varied approaches, using this therapeutic strategy, need to be interpreted individually. The potential failure of one agent does not in anyway, imply or suggest that all agents employing a passive immunization strategy should be abandoned. The success or failure of each approach may be distinct to the agent used. Investigation into the science and clinical utility of passive immunization strategies is one of the most active fields of research in AD today, and it is clear that we have much to learn from this endeavor.[1–13]Far from “dead and buried”, passive immunization remains “alive and well” as a therapeutic strategy that may eventually lead to the first approved disease-modifying therapy for AD.

Acknowledgments

I would like to first acknowledge the many subjects, caregivers, friends and families of persons with AD that have engaged in clinical research activities that have allowed such discoveries to be made. Without your selfless engagement, such advances would not be possible. Secondly I would like to acknowledge the many researchers and clinicians in the field that I have not cited in this manuscript. Your contributions have been critical in leading us to our current investigations and search for disease modifying therapies for AD. Dr. Jicha is supported by funding from the NIH/NIA 1 P30 AG028383& 2R01AG019241-06A2, NIH LRP 1 L30 AG032934-01, Alzheimer’s Association NIRG-07-59967, and the Sanders-Brown Foundation. Dr Jicha has also received research support for clinical trial activities from NIH/NIA ADCS U01AG010483, Pfizer Inc., Elan Pharmaceuticals, and Baxter Inc.

References

- 1.Brody DL, Holtzman DM. Active and passive immunotherapy for neurodegenerative disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:175–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardberg AS, et al. Molecular basis for passive immunotherapy of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(40):15659–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705888104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geylis V, Steinitz M. Immunotherapy of Alzheimer’s disease (AD): from murine models to anti-amyloid beta (Abeta) human monoclonal antibodies. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5(1):33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkes CA, McLaurin J. Immunotherapy as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(11):1535–48. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.11.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hock C, et al. Antibodies against beta-amyloid slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2003;38(4):547–54. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtlen P, Mohajeri MH. Antibody-based approaches in Alzheimer’s research: safety, pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and analytical tools. J Neurochem. 2008;104(4):859–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattson MP, Chan SL. Good and bad amyloid antibodies. Science. 2003;301(5641):1847–9. doi: 10.1126/science.301.5641.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan D, Gitter BD. Evidence supporting a role for anti-Abeta antibodies in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(5):605–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neff F, et al. Immunotherapy and naturally occurring autoantibodies in neurodegenerative disorders. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7(6):501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer disease: mechanistic understanding predicts novel therapies. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(8):627–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon B. Beta-amyloidbased immunotherapy as a treatment of Alzheimers disease. Drugs Today (Barc) 2007;43(5):333–42. doi: 10.1358/dot.2007.43.5.1062670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon B. Clinical immunologic approaches for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16(6):819–28. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon B. Intravenous immunoglobulin and Alzheimer’s disease immunotherapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007;9(1):79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster JK, et al. Immunization in Alzheimer’s disease: naive hope or realistic clinical potential? Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinitz M. Developing injectable immunoglobulins to treat cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8(5):633–42. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisniewski T, Konietzko U. Amyloid-beta immunisation for Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(9):805–11. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasilva KA, Aubert I, McLaurin J. Vaccine development for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(33):4283–93. doi: 10.2174/138161206778793001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemere CA, et al. Novel Abeta immunogens: is shorter better? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(4):427–36. doi: 10.2174/156720507781788800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier M, Seabrook TJ, Lemere CA. Developing novel immunogens for an effective, safe Alzheimer’s disease vaccine. Neurodegener Dis. 2005;2(5):267–72. doi: 10.1159/000090367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrer I, et al. Neuropathology and pathogenesis of encephalitis following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(1):11–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox NC, et al. Effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) on MRI measures of cerebral volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64(9):1563–72. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159743.08996.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilman S, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology. 2005;64(9):1553–62. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159740.16984.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes C, et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9634):216–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M, et al. Abeta42 immunization in Alzheimer’s disease generates Abeta N-terminal antibodies. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(3):430–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levites Y, et al. Insights into the mechanisms of action of anti-Abeta antibodies in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Faseb J. 2006;20(14):2576–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6463fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masliah E, et al. Abeta vaccination effects on plaque pathology in the absence of encephalitis in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64(1):129–31. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000148590.39911.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan D. Mechanisms of A beta plaque clearance following passive A beta immunization. Neurodegener Dis. 2005;2(5):261–6. doi: 10.1159/000090366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicoll JA, et al. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-beta peptide: a case report. Nat Med. 2003;9(4):448–52. doi: 10.1038/nm840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orgogozo JM, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology. 2003;61(1):46–54. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073623.84147.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patton RL, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide remnants in AN-1792-immunized Alzheimer’s disease patients: a biochemical analysis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(3):1048–63. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin-Jones Z, Lasagna-Reeves C. Which is a better target for AD immunotherapy, A beta or tau? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(2):111–2. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181641355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotz J, et al. Transgenic animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: histopathology, behavior and therapy. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(7):664–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardy J. Has the amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease been proved? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3(1):71–3. doi: 10.2174/156720506775697098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aisen PS, et al. Alzhemed: a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(4):473–8. doi: 10.2174/156720507781788882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green RC, et al. Safety and efficacy of Tarenflurbil in subjects with mild Alzheimer’s disease: results from an 18-month multi-center phase III trial. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(4 suppl 2):T165. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiang PK, Lam MA, Luo Y. The many faces of amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8(6):580–4. doi: 10.2174/156652408785747951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gongadze N, et al. The mechanisms of neurodegenerative processes and current pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer’s disease. Georgian Med News. 2008;(155):44–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salloway S, et al. Disease-modifying therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(2):65–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Games D, et al. Prevention and reduction of AD-type pathology in PDAPP mice immunized with A beta 1–42. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:274–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janus C, et al. A beta peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):979–82. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schenk D, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400(6740):173–7. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bombois S, et al. Absence of beta-amyloid deposits after immunization in Alzheimer disease with Lewy body dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(4):583–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dodart JC, et al. Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain Abeta burden in Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(5):452–7. doi: 10.1038/nn842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asami-Odaka A, et al. Passive immunization of the Abeta42(43) C-terminal-specific antibody BC05 in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2005;2(1):36–43. doi: 10.1159/000086429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bard F, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):916–9. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeMattos RB, et al. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8850–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151261398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gray AJ, et al. Antibody against C-terminal Abeta selectively elevates plasma Abeta. Neuroreport. 2007;18(3):293–6. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280148e76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kotilinek LA, et al. Reversible memory loss in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6331–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06331.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lombardo JA, et al. Amyloid-beta antibody treatment leads to rapid normalization of plaque-induced neuritic alterations. J Neurosci. 2003;23(34):10879–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10879.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohajeri MH, et al. Passive immunization against beta-amyloid peptide protects central nervous system (CNS) neurons from increased vulnerability associated with an Alzheimer’s disease-causing mutation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):33012–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilcock DM, et al. Passive immunotherapy against Abeta in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cleary JP, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(1):79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee EB, et al. Targeting amyloid-beta peptide (Abeta) oligomers by passive immunization with a conformation-selective monoclonal antibody improves learning and memory in Abeta precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(7):4292–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Oligomers on the brain: the emerging role of soluble protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. Protein Pept Lett. 2004;11(3):213–28. doi: 10.2174/0929866043407174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bacher M, et al. Peripheral and central biodistribution of 111In-labelled anti-beta-amyloid anitbodies in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee EB, et al. Meningoencephalitis associated with passive immunization of a transgenic murine model of Alzheimer’s amyloidosis. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(12):2564–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burbach GJ, et al. Vessel ultrastructure in APP23 transgenic mice after passive anti-Abeta immunotherapy and subsequent intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28(2):202–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chauhan NB, Siegel GJ. Intracerebroventricular passive immunization in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3(6):717–25. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gandy S, Walker L. Toward modeling hemorrhagic and encephalitic complications of Alzheimer amyloid-beta vaccination in nonhuman primates. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(5):607–15. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pfeifer M, et al. Cerebral hemorrhage after passive anti-Abeta immunotherapy. Science. 2002;298(5597):1379. doi: 10.1126/science.1078259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Racke MM, et al. Exacerbation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy-associated microhemorrhage in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice by immunotherapy is dependent on antibody recognition of deposited forms of amyloid beta. J Neurosci. 2005;25(3):629–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4337-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilcock DM, et al. Amyloid-beta vaccination, but not nitro-nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment, increases vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage while both reduce parenchymal amyloid. Neuroscience. 2007;144(3):950–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levites Y, et al. Anti-Abeta42-and anti-Abeta40-specific mAbs attenuate amyloid deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(1):193–201. doi: 10.1172/JCI25410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siemers E, et al. Safety, tolerability and biomarker effects of an Abeta monoclonal antibody administered to patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(4 suppl 2):T774. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grundman M, Black R. Clinical trials of Bapineuzamab, a beta-amyloid-targeted immunotherapy in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(4 suppl 2):T166. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dodel RC, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins containing antibodies against beta-amyloid for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(10):1472–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.033399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Relkin NR, et al. 18-Month study of intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of mild Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsakanaikas D, et al. Effects of uninterrupted intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of Alzheimer’s disease for nine months. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(4 suppl 2):T776. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tucker SM, Borchelt DR, Troncoso JC. Limited clearance of pre-existing amyloid plaques after intracerebral injection of Abeta antibodies in two mouse models of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(1):30–40. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815f38d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rakover I, Arbel M, Solomon B. Immunotherapy against APP beta-secretase cleavage site improves cognitive function and reduces neuroinflammation in Tg2576 mice without a significant effect on brain abeta levels. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4(5):392–402. doi: 10.1159/000103250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu R, et al. Single chain variable fragments against beta-amyloid (Abeta) can inhibit Abeta aggregation and prevent abeta-induced neurotoxicity. Biochemistry. 2004;43(22):6959–67. doi: 10.1021/bi049933o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poduslo JF, et al. In vivo targeting of antibody fragments to the nervous system for Alzheimer’s disease immunotherapy and molecular imaging of amyloid plaques. J Neurochem. 2007;102(2):420–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Castellani RJ, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: major contributor or decorative response to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(5):599–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.019. discussion 603–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prada CM, et al. Antibody-mediated clearance of amyloid-beta peptide from cerebral amyloid angiopathy revealed by quantitative in vivo imaging. J Neurosci. 2007;27(8):1973–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5426-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schroeter S, et al. Immunotherapy reduces vascular amyloid-beta in PDAPP mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28(27):6787–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2377-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Belmouaz S, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy induced by intravenous immunoglobulin. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(1):417–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koichihara R, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome associated with IVIG in a patient with Guillain-Barre syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;39(2):123–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mathy I, et al. Neurological complications of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy: an illustrative case of acute encephalopathy following IVIg therapy and a review of the literature. Acta Neurol Belg. 1998;98(4):347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakajima M. Posterior reversible encephalopathy complicating intravenous immunoglobulins in a patient with miller-fisher syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2005;54(1):58–60. doi: 10.1159/000087720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van Diest D, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy and Guillain-Barre syndrome in a single patient: coincidence or causative relation? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Railey MD, Adair MA, Burks AW. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ahsan N. Intravenous immunoglobulin induced-nephropathy: a complication of IVIG therapy. J Nephrol. 1998;11(3):157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eibl MM. Intravenous immunoglobulins in neurological disorders: safety issues. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(Suppl 4):S222–6. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gupta N, et al. Intravenous gammglobulin-associated acute renal failure. Am J Hematol. 2001;66(2):151–2. doi: 10.1002/1096-8652(200102)66:2<151::AID-AJH1035>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haskin JA, Warner DJ, Blank DU. Acute renal failure after large doses of intravenous immune globulin. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(7–8):800–3. doi: 10.1345/aph.18305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hefer D, Jaloudi M. Thromboembolic events as an emerging adverse effect during high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in elderly patients: a case report and discussion of the relevant literature. Ann Hematol. 2004;83(10):661–5. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0895-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215–26. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nettis E, et al. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2003;3(2):143–9. doi: 10.2174/1568008033340243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Orbach H, Tishler M, Shoenfeld Y. Intravenous immunoglobulin and the kidney--a two-edged sword. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34(3):593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zaidan R, et al. Thrombosis complicating high dose intravenous immunoglobulin: report of three cases and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(4):367–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cummings JL, Doody R, Clark C. Disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer disease: challenges to early intervention. Neurology. 2007;69(16):1622–34. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000295996.54210.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Galasko D. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease--clinical needs and application. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8(4):339–46. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kidd PM. Alzheimer’s disease, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and age-associated memory impairment: current understanding and progress toward integrative prevention. Altern Med Rev. 2008;13(2):85–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Solomon PR, Murphy CA. Early diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(5):769–80. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.5.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sramek JJ, Veroff AE, Cutler NR. Mild cognitive impairment: emerging therapeutics. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(10):1179–88. doi: 10.1345/aph.19394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bartus RT, Dean RL., 3rd Pharmaceutical treatment for cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative conditions: exploring new territory using traditional tools and established maps. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202(1–3):15–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oddo S, et al. Abeta immunotherapy leads to clearance of early, but not late, hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates via the proteasome. Neuron. 2004;43(3):321–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang DS, et al. Assembly of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta fibrils and approaches for therapeutic intervention. Amyloid. 2001;8(Suppl 1):10–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Doody RS, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with MCI. A 48-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2009 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd6c25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gauthier SG. Alzheimer’s disease: the benefits of early treatment. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(Suppl 3):11–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jelic V, Kivipelto M, Winblad B. Clinical trials in mild cognitive impairment: lessons for the future. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(4):429–38. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kirshner HS. Mild cognitive impairment: to treat or not to treat. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005;5(6):455–7. doi: 10.1007/s11910-005-0033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Levey A, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: an opportunity to identify patients at high risk for progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Ther. 2006;28(7):991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Raschetti R, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(11):e338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]