Abstract

Leukocoria in infants is always a danger signal as retinoblastoma, a malignant retinal tumor, is responsible for half of the cases in this age group. More common signs should also be considered suspicious until proved otherwise, such as strabismus, the second most frequent sign of retinoblastoma. Less frequent manifestations are inflammatory conditions resistant to treatment, hypopyon, orbital cellulitis, hyphema or heterochromia. Other causal pathologies, including persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV), Coats’ disease, ocular toxocariasis or retinopathy of prematurity, may also manifest the same warning signs and require specialized differential diagnosis. Members of the immediate family circle are most likely to notice the first signs, the general practitioner, pediatrician or general ophthalmologist the first to be consulted. On their attitude will depend the final outcome of this vision and life-threatening disease. Early diagnosis is vital.

Keywords: leukocoria, strabismus, retinoblastoma, Coats’ disease, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV)

Introduction

Retinoblastoma represents the greatest challenge in the field of ophthalmology. Affecting very young infants, in most cases perfectly healthy in all other respects, this highly malignant cancer of the retina threatens those individuals with the longest potential lifespan. Survivors may be severely handicapped by lesions of the posterior pole affecting central visual function.

These children can be cured, however, at low cost and with minimal suffering, provided that treatment is given in the early stages of disease. At later stages treatment is costly, burdensome, and with no certain outcome.

Retinoblastoma is fortunately a rare disease, but other intraocular lesions may mimic the initial signs or clinical features and are sometimes called “pseudo-retinoblastomas” (Dollfus and Auvert 1953).

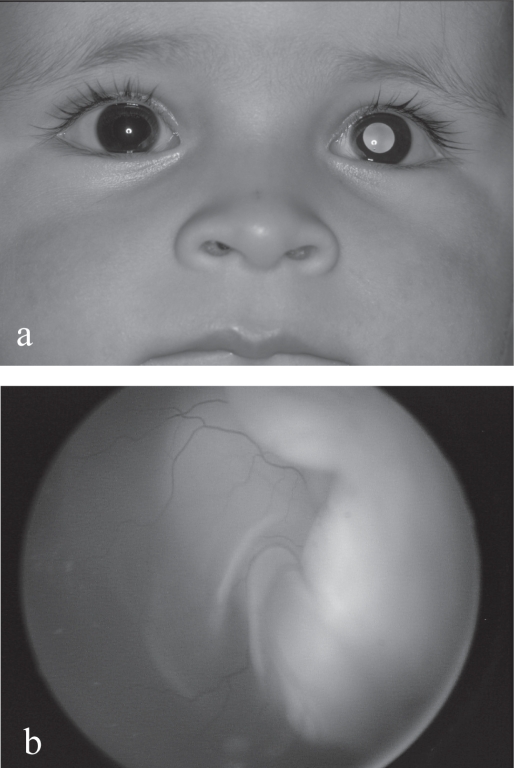

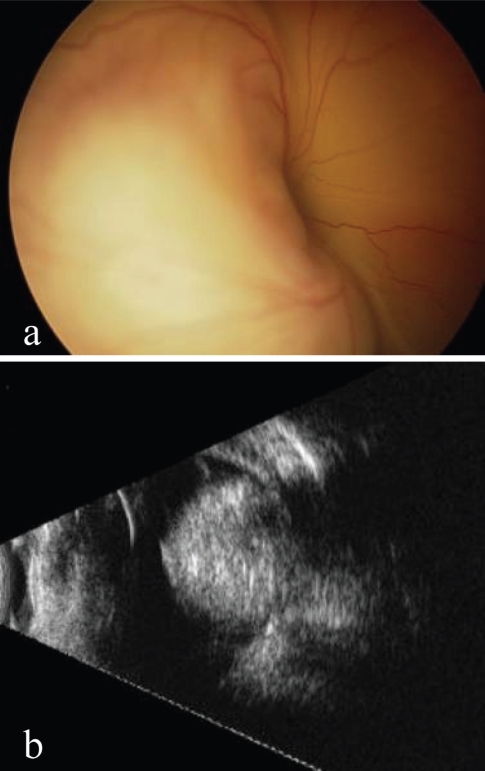

Retinoblastoma does, however, represent 80% of primary ocular tumors in children under 15 years of age (Mahoney et al 1990) 17% of all neonatal cancers (Halperin 2000) and 1% of all deaths due to cancer (Miller 1969). All ages considered, it is the third most frequent cancer of the eye and ocular adnexa (20%) and represents 3% of all pediatric cancers (Scat et al 1996). Thus the importance of keeping in mind the possibility of retinoblastoma when confronted with suspicious signs such as a white pupil or leukocoria (Figure1a), the most common first manifestation, strabismus or any other unexplained signs.

Figure 1.

(a) Left leukocoria in a 1 year-old boy with unilateral retinoblastoma. (b) Exophytic retinoblastoma with total retinal detachment.

In this article, other conditions to take into consideration in the differential diagnosis of leukocoria or other signs associated with retinoblastoma will be reviewed.

First signs

The primary sign is leukocoria. The term leukocoria, also known as “amaurotic cat’s eye”, literally means “white pupil” from the greek “leucos” (white) and “korê” (pupil) and is created by the reflection of incident light off the retinal lesion within the pupillary area when the fundus is directly illuminated (Figures 1a and 1b). Leukocoria is the most frequent sign (60%) and is associated with retinoblastoma in almost half of all infants presenting with a white pupil (Howard and Ellsworth 1965b). A white pupil is most often initially noticed by close family members (Abramson et al 2003) or on flash photography, this often the primary reason for consultation. It is, however, a late manifestation, the vital prognosis still good (88% at 5 years) but that for globe salvage uncertain. A number of other conditions, however, may also present with leukocoria as a first sign. These include persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV), Coats’ disease, ocular toxocariasis, retinopathy of prematurity, retinal hamartomas (Bourneville’s tuberous sclerosis, von Recklinhausen’s disease), congenital falciform fold or organized vitreous hemorrhage (Howard and Ellsworth 1965a; Shields, Shields et al 1991).

The second most frequent primary manifestation is strabismus (20%), an affection thus not to be taken lightly and requiring immediate ophthalmological examination comprising full fundus examination with a dilated pupil, under anesthesia if necessary. Strabismus is usually secondary to macular involvement and an invaluable early sign carrying an excellent life prognosis and every chance of preserving the globe.

Finally, in 20% of cases the first manifestation is atypical, often inflammatory or hypertensive, and common to both retinoblastoma and certain pseudo-retinoblastomas. Atypical signs can cause major problems in diagnosis (Binder 1974; Balmer et al 1994; de Leon et al 2005) and include red eye, uveitis, hypopyon, hyphema, heterochromia, rubeosis, glaucoma or phthisis bulbi, in particular as ultimate complications of unchecked disease. These are very late signs carrying a far more reserved vital and functional prognosis.

Differential diagnosis

Depending on the clarity of the media, first signs, stage of disease, frequency, the type and gravity of complications associated with spontaneous evolution, the approach to differential diagnosis will be made according to whether diagnosis is simple, difficult or concerns rare diseases.

Simple diagnosis

With clear media, diagnosis is generally simple and can be made at first glance, such as in most cases of retinoblastoma, choroidal or optic nerve coloboma, falciform retinal fold, myelinated fibers, “Morning Glory Syndrome”, cataract, congenital toxoplasmosis or retinal capillary hemangioma.

Asymmetrical pupillary reflexes, even leukocoria, may be associated with common strabismus or anisometropia. With strabismus, the reflex may be darker in the fixating eye due to a greater pigmentation of the macular area (Brückner’s phenomenon) (Brückner 1962). Other, more serious conditions, are also easily identifiable when of typical presentation, in particular Coats’ disease, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV), astrocytic hamartoma (Bourneville’s tuberous sclerosis) or retinopathy or prematurity.

Difficult diagnosis

Diagnosis of retinoblastoma or pseudo-retinoblastoma is much more difficult with opaque media or with atypical features.

Late stages of PHPV and Coats’ disease are the most common conditions to mimic retinoblastoma (Balmer et al 1988; Shields, Parsons, et al 1991). In the absence of the classical clinical triad or with atypical retinal lesions, diagnosis of retinal astrocytic hamartoma may also be problematic.

Inflammatory conditions, in particular ocular toxocariasis, can lead to complex clinical features requiring a whole battery of investigations, including serology, ultrasonography, and neuro-diagnostic tools.

Severe vitreous hemorrhage following trauma may transform into a massive retinal gliosis and even develop calcifications (Yanoff et al 1971). The history may be confused, the trauma unrecognized or prenatal or, conversely, be wrongly held responsible for the clinical situation. Primary or secondary retinal detachment may further complicate the assessment.

Rare diseases

Sheer rarity of a disease can make diagnosis more difficult, such as in medulloepithelioma, optic nerve glioma, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, X-linked retinoschisis, Norrie’s disease, or incontinentia pigmenti.

Table 1 gives a classification by system and by frequency of diseases involved in the differential diagnosis of retinoblastoma.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis in infantile leukocoria

1. Tumors

|

2. Phakomatoses

|

3. Congenital malformations

|

4. Vascular diseases

|

5. Inflammatory diseases

|

6. Trauma

|

7. Divers

|

Genetics

Retinoblastoma (Augsburger et al 1995; Abramson et al 1998; Balmer and Munier 2002a; Aerts et al 2006; Bornfeld et al 2006) is a malignant tumor of the retina resulting from a double oncogenic mutation between the beginning of the 3rd month of gestation and 4 years of age in an immature retinal cell, most likely a multipotent retinoblast (Munier 2002), precursor cone cell.

Onset of the disease may thus occur in utero (Maat-Kievit et al 1993) and up to 4 years of age, with a mean age of appearance of first signs of 7 months for bilateral cases, 24 months in unilateral disease (Balmer and Munier 2002a).

Retinoblastoma may be non hereditary (60%) or hereditary (40%), the hereditary form showing a classic autosomal dominance pattern with 90% penetration at birth.

The RB1 gene belongs to the group of anti-oncogenes, also called tumor-suppressor genes.

According to the literature, the mean frequency of retinoblastoma is one in 20,000 live births (Balmer and Munier 2002b) with no sex, race or geographic predilection and no known exogenous risk factors apart from the age of the parents, in particular that of the father (DerKinderen et al 1990; Matsunaga et al 1990).

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of retinoblastoma varies according to the type of growth of the tumor and duration, the degree of vascularization and presence of calcifications, vitreous seeding, retinal detachment or hemorrhage.

The initial tumoral cell divisions may occur in different internal retinal layers, a tumor developing on the surface of the retina and into the vitreous cavity being called an endophytic growth, while that developing from the external layers, invading the subretinal space and causing a retinal detachment an exophytic growth. A mixed growth involves the association of these two types. More rarely (2%), the tumor may develop in an insidious manner within the retinal layers and subretinal space, with no elevated mass and no calcifications, growing slowly along the retinal axis towards the anterior segment where late manifestations of the disease occur in the form of pseudo-inflammatory complications. This is the diffuse infiltrating, or plaque-like form of retinoblastoma (Morgan 1971).

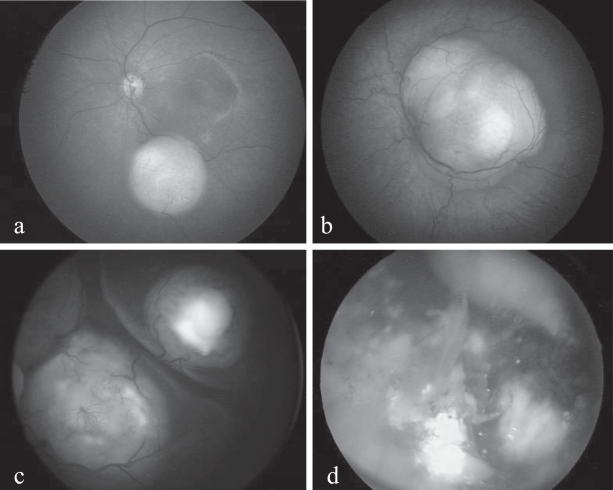

Endophytic retinoblastoma (Figures 2a and 2b) presents as one or more isolated or coalesced tumors of variable size, round or oval-shaped, yellowish-white (calcifications) or pinkish (vascularization) in color with its own, often turgescent and tortuous, vascular network. Endophytic retinoblastoma shows a marked tendency to invasion of the vitreous by seeding. Exophytic retinoblastoma (Figure 2c), developing outside the retina towards the choroid, causes a retinal detachment that masks to a greater or lesser degree the details of the underlying mass or masses. Seeding may occur in the subretinal fluid. Both endo- and exophytic forms are likely to develop calcifications, in the form of chalky white patches within the tumoral mass. Vitreous and subretinal seeding, along with calcifications, are the characteristics virtually pathognomonic of retinoblastoma (Figure 2d). The diffuse infiltrating form, however, presenting as a greyish retinal coating with no elevated mass and no calcifications, may finally manifest as a pseudo-hypopion (Morgan 1971; Girard et al 1989). Finally, in probably 2%–5% of cases (Balmer and Munier 2002a), retinoblastoma may present in an inactive form indicative of spontaneous remission, called retinoma or, to use the histopathological term, retinocytoma. This is characterized by homogenous, more or less translucent greyish masses, calcifications, with pigment migration and proliferation bordering the tumor (Gallie et al 1982). In all respects, retinoma resembles a retinoblastoma sterilized by radiotherapy, without ever having undergone any treatment whatsoever.

Figure 2.

(a) Small endophytic unifocal retinoblastoma. (b) Unifocal juxtapapillary lesion involving the macular, with xanthophile pigment visible superiorly. (c) Multifocal retinoblastoma with foci visible beneath the detached retina and superficial vascular anomalies. (d) Multifocal retinoblastoma with calcifications and massive vitreous seeding.

In the hereditary form of retinoblastoma there is also a risk of trilateral involvement, this the association of retinoblastoma, usually bilateral (90%) but not exclusively, with an intracranial neuroblastic tumor, commonly in the region of the pineal gland (pinealoblastoma), these cells being linked to the RB1 gene and of the same phylogenic origin as retinal tissues (De Potter et al 1994; Kivelä 1999). The vital prognosis for these cerebral tumors is very poor. Furthermore, children carrying the RB1 gene suffer life-long exposure to other non-ocular primary malignancies, in particular osteosarcoma of the orbit or elsewhere (Moll et al 1997, 2001; Abramson 1999; Abramson et al 2001). The risk is 1% per year of evolution and is particularly high in children having received radiotherapy before the age of one year (Abramson 1999).

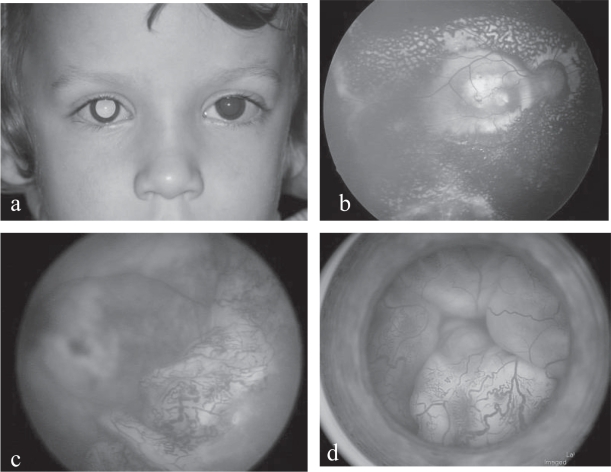

Coats’ disease (primary retinal telangiectasia)

Coats’ disease, or primary (congenital) retinal telangiectasia, is a rare exudative retinopathy (Coats 1908; Balmer 2005; Shields et al 2001) (Figure 3). Unilateral in 90% of cases, the disease habitually affects young males (80%) between 5 and 10 years old, although it can appear much earlier, before one year of age. It is non hereditary, probably congenital, with no known associated systemic diseases.

Figure 3.

(a) Coats’ disease: right leukocoria in a 2 year-old boy. (b) Coats’ disease: yellowish exudates covering the whole macular area. (c) Coats’ disease: extensive peripheral telangiectatic vessels and partial retinal detachment. (d) Coats’ disease: total bullous retinal detachment posterior to the clear lens and vascular telangiectasias.

Clinical characteristics include three major features: retinal telangiectasia in the form of strings of fusiform dilatations of the retinal vessels, usually peripheral; massive yellowish exudates within and underlying an edematous retina, sometimes giving a pseudo-tumoral appearance with a predilection for the macular area; exudative, sometimes total, retinal detachment (Figures 4b, 4c, and 4d). The exudates may be responsible for a luminous leukocoria (Figure 3a) but, in the presence of retinal detachment, this will take on a greyer hue.

Figure 4.

(a) Total retinal detachment in a 2 month-old boy. (b) Corresponding ultrasonography showing an intraocular mass with high reflectivity (calcifications) and marked attenuation (shadowing) characteristic for retinoblastoma.

The evolution of Coats’ disease is variable. It may stabilize, although often with loss of central vision due to macular lipid deposits, or deteriorate with total exudative retinal detachment (Figure 3d), iridis rubeosis, neovascular glaucoma, cataract, uveitis, phthisis bulbi and, ultimately, total and definitive loss of vision.

The primary lesion is most likely a localized, evolutive abnormality of the developing retinal vessels. The precise origin remains unknown, but Coats’ disease may be linked to a somatic mutation of the NDP gene (Norrie Disease Protein) leading to a deficiency of norrin in the developing retina (Black et al 1999).

Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV) or persistence of the fetal vasculature (PFV)

Coats’ disease and persistence of Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous are the most common benign lesions to mimic retinoblastoma (Reese 1955; Goldberg 1997). PHPV is a congenital malformation caused by the arrest of normal regression of the embryonic vascular connective tissue (hyaloid artery, vasa hyaloidea propria, tunica vasculosa lentis), regression that normally occurs after 4 months gestation. Almost always unilateral, this condition often presents with moderate microphthalmia and other associated malformations such as failure of cleavage of the anterior segment or uveal coloboma. PHPV is non hereditary.

The most common signs and symptoms are leukocoria, this caused by retrolental fibroplasia and/or cataract, microphthalmia and characteristic traction of the ciliary processes sometimes visible in the periphery of the dilated pupil.

Clinical manifestations of PHPV are varied and numerous, affecting the anterior and/or posterior segments, ranging from minimal isolated lesions to complex interactive secondary complications.

The natural course of the disease may result in early cataract and closed-angle glaucoma. In the long term, enucleation may be inevitable due to terminal glaucoma, intra-ocular hemorrhage, retinal detachment, uveitis or phthisis bulbi.

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)

Retinopathy of prematurity, known previously as retrolental fibroplasia, results from the abnormal proliferation of retinal vessels, for the most part in premature infants with a birthweight less than 1250 gm or of under 32 weeks gestation. These children have usually received oxygen therapy, and the first signs of retinopathy appear between 35 and 45 post-conceptional weeks. In the vast majority of cases spontaneous regression occurs over a period of 3 to 4 months. Only children of under 1000 gm birthweight are threatened with blindness.

The first and earliest clinical feature is a clear line of demarcation between the vascular and avascular retina (stage 1) (Anon 1987), indicating that angiogenesis is slowing down or even arrested. Angiogenesis starts around the 16th week of gestation and normally terminates at 36 weeks for the nasal retina, at term for the temporal retina. Capillary growth on the line of demarcation forms a prominent ridge (stage 2), a neoproliferation that may reach beyond the retina, infiltrating the internal limiting membrane and extending into the vitreous (stage 3). At this stage it forms a dense fibrovascular membrane reaching from front to back of the vitreous body and may cause retraction of arborized vessels to form a falciform fold, papillary dysversion and macular ectopia. Unchecked, traction from the proliferation will cause initially a partial retinal detachment (stage 4), ultimately a total detachment (stage 5), finally resulting in the cicatricial stage of retrolental fibroplasia. Leukocoria may be present from stage 3 onwards.

The retinopathy may arrest spontaneously at any point of the natural course of the disease, the critical period being the stage when neovascularization invades the vitreous, the retroequatorial zone and posterior pole. From this point, known as the “threshold disease”, the risk of blindness is 50% and cryotherapy is indicated (Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative 2001, 2003; Palmer et al 2005).

Medulloepithelioma

Medulloepithelioma is a non hereditary tumor, usually unilateral, deriving from the immature embryonic non-pigmented ciliary body (Andersen 1962; Broughton and Zimmerman 1978) or, more rarely, from the optic nerve or retina. First manifestations usually occur in early childhood, occasionally in the adult, with leukocoria, poor vision and typically a vascularized iris mass, this greyish or salmon-colored, in some cases pigmented. The tumor may be polycystic and cystic fragments may be found liberated into the aqueous humor or vitreous body. Tumor growth is slow, developing in the surrounding structures of the anterior segment or towards the optic nerve. It is difficult to assess the benign or malignant nature of the tumor, even on histopathological examination (Broughton and Zimmerman 1978).

Optic nerve glioma

Optic nerve glioma is the most frequent intrinsic tumor of the anterior portion of the optic nerve (65%), followed by meningioma (35%, Dutton, 1994). Preschool or school-age children are most often affected and the first manifestations are usually exophthalmia and loss of vision (Dutton, 1994, Hamelin et al 2000). The tumor is associated with neurofibromatosis in over 30% of cases. A true neoplasm, optic nerve glioma presents phases of rapid growth followed by stagnation, sometimes even spontaneous regression (Parsa et al 2001). The tumor may remain dormant for long periods of time then suddenly resume growth in a wholly unpredictable manner. Papillary and intraocular involvement is possible but very rare.

The mortality rate is low (5%) as long as the tumor is restricted to the optic nerve. However, invasion of surrounding tissues may lead to involvement of the chiasma and infiltration of adjacent cerebral structures. Involvement of the hypothalamus and third ventricule considerably increases the mortality rate, this reaching 50% after 15 years follow-up (Dutton 1994).

In the adult, optic nerve glioma is malignant and invariably fatal due to involvement of the chiasma and cerebral structures.

Methods of diagnosis

In difficult cases, where fundus examination alone does not enable diagnosis to be made with certainty (around 10% of cases), ultrasonography is the next method of choice, this being an inexpensive, inoffensive and highly specific means of detecting the calcifications distinctive of retinoblastoma (Figures 4a and 4b).

OCT (optical coherence tomography) is used more and more frequently to evaluate macular tumors or simulating lesions. Non invasive and well tolerated, it provides invaluable information on the presence of fibrosis, edema or subretinal fluid in the foveal area (Shields et al 2004).

A CT scan is useful in detecting calcifications that may have escaped ultrasonography but does involve X-rays and is thus potentially dangerous with cumulative examinations (Apushkin et al 2005).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is ideal for detecting any budding asymptomatic tumor of the pineal gland or optic chiasma in hereditary bilateral multifocal cases (trilateral retinoblastoma). It also enables differentiation between solid tumors (over 2 mm diameter) and lesions surrounded with subretinal fluid, as is the case with advanced Coats’ disease or PFV (Apushkin et al 2005).

The role of the primary care physician

Whether the family doctor or pediatrician, the primary care physician is usually the first to be confronted with the problem and thus plays an essential role, as the evolution and ultimate outcome of the disease will depend on the speed of reaction at this initial stage.

Any report of a white pupil, whatever the context, should be taken seriously and, until proved otherwise, considered to be at best the result of a benign malformation, at worst the first sign of cancer of the retina, retinoblastoma.

A full family anamnesis is essential, with particular attention to any history of enucleation in infancy. The age of the child should be taken into account and a full description of the anomaly noted. An assessment of the child’s vision (fixation and ability to follow objects), iris color and eye position (strabismus) will be recorded. Most importantly, any leukocoria must be sought out with the use of a pen torch under subdued lighting (McLaughlin and Levin 2006). All positions of gaze should be elicited, first of all in miosis then repeated with the pupil fully dilated, taking advantage of mydriasis to detect any anomaly of the macular or papillary region on ophthalmoscopy.

Whether the leukocoria or any retinal lesion be confirmed at this stage or not, there should be no delay in referring the child to a specialist. Depending on the outcome of this second examination, further investigations at a reference center may be required.

Conclusions

Many ocular conditions in childhood may mimic retinoblastoma, either by similar first signs, leukocoria in particular, similar clinical features, or by comparable evolutive complications. Correct diagnosis without delay is imperative as retinoblastoma puts a child’s vision, and indeed life, in danger (Goddard et al 1999; Wallach et al 2006). Early treatment is and will remain the best possible treatment for this highly malignant tumor. Keeping in mind a possible diagnosis of retinoblastoma is the first major step to a full recovery.

Early diagnosis concerns everybody in contact with the child, the parents, family/friends, nurses, the family doctor, often first to be confronted with the initial signs, also specialists and reference centers. Leukocoria, or any other unexplained ocular sign in an infant should always, until proved otherwise, invoke the possibility of a malignant tumor and put in motion all the necessary means for prompt diagnosis.

References

- Abramson DH. Second nonocular cancers in retinoblastoma: a unified hypothesis. The Franceschetti Lecture. Ophthalmic Genet. 1999;20:193–204. doi: 10.1076/opge.20.3.193.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson DH, Beaverson K, Sangani P, et al. Screening for retinoblastoma: presenting signs as prognosticators of patient and ocular survival. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1248–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson DH, Frank CM, Susman M, et al. Presenting signs of retinoblastoma. J Pediatr. 1998;132:505–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson DH, Melson MR, Dunkel IJ, et al. Third (fourth and fifth) nonocular tumors in survivors of retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1868–76. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aerts I, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Gauthier-Villars M, et al. Retinoblastoma. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SR. Medulloepithelioma of the retina. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1962;2:483–506. [Google Scholar]

- [Anon] An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. II. The classification of retinal detachment. The International Committee for the Classification of the Late Stages of Retinopathy of Prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:906–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apushkin MA, Shapiro MJ, Mafee MF. Retinoblastoma and simulating lesions: role of imaging. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2005;15:49–67. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augsburger JJ, Oehlschlager U, Manzitti JE. Multinational clinical and pathologic registry of retinoblastoma. Retinoblastoma International Collaborative Study report 2. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233:469–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00183426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer A, Gailloud C, Munier F, et al. [Unusual presentation of retinoblastoma] Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1994;204 doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1035546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer A, Gailloud C, Uffer S, et al. [Retinoblastoma and pseudoretinoblastoma: diagnostic study] Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1988;192 doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer A, Munier F. Rétinoblastome: diagnostic. In: Zografos L, editor. Tumeurs intraoculaires. Paris: Société Française d’Ophtalmologie et Masson; 2002a. pp. 485–533. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer A, Munier F. Rétinoblastome: Epidémiologie. In: Zografos L, editor. Tumeurs intraoculaires. Paris: Société Française d’Ophtalmologie et Masson; 2002b. pp. 481–5. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer A, Zografos L, Uffer S, et al. 2005Maladie de Coats et télangiectasies primaires et secondaires Médico-Chirurgicale E.Ophtalmologie Paris: Elsevier SAS; p 21–240–E–30. [Google Scholar]

- Binder PS. Unusual manifestations of retinoblastoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;77:674–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(74)90530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black GC, Perveen R, Bonshek R, et al. Coats’ disease of the retina (unilateral retinal telangiectasis) caused by somatic mutation in the NDP gene: a role for norrin in retinal angiogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2031–5. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornfeld N, Schuler A, Boloni R, et al. 2006[Retinoblastoma] Ophthalmologe 10359–76.quiz 77–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WL, Zimmerman LE. A clinicopathologic study of 56 cases of intraocular medulloepitheliomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85:407–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brückner R. Exakte Strabismusdiagnostik bei 1/2–3 jährigen Kindern mit einem einfachen Verfahren, dem “Durchleuchtungstest”. Ophthalmologica. 1962;149:184–98. [Google Scholar]

- Coats G. Forms of retinal diseases with massive exudation. Roy Lond Ophthalmol Hosp Rep. 1908;17:440–525. [Google Scholar]

- Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group Multicenter Trial of Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity: ophthalmological outcomes at 10 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1110–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.8.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon JM, Walton DS, Latina MA, et al. Glaucoma in retinoblastoma. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20:217–22. doi: 10.1080/08820530500353831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Potter P, Shields JA, Shields CL. Clinical variations of trilateral retinoblastoma: a report of 13 cases. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1994;31:26–31. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19940101-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerKinderen DJ, Koten JW, Tan KE, et al. Parental age in sporadic hereditary retinoblastoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110:605–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollfus M-A, Auvert B. Etude clinique, génétique et thérapeutique. Paris: Société française d’Ophtalmologie; 1953. Le gliome de la rétine (rétinoblastome) et les pseudogliomes. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton JJ. Gliomas of the anterior visual pathway. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;38:427–52. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(94)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early Treatment For Retinopathy Of Prematurity Cooperative Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1684–94. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie BL, Ellsworth RM, Abramson DH, et al. Retinoma: spontaneous regression of retinoblastoma or benign manifestation of the mutation? Br J Cancer. 1982;45:513–21. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard B, Le Hoang P, D’Hermies F, et al. Le rétinoblastoma infiltrant diffus. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1989;12:369–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard AG, Kingston JE, Hungerford JL. Delay in diagnosis of retinoblastoma: risk factors and treatment outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1320–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.12.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MF. Persistent fetal vasculature (PFV): an integrated interpretation of signs and symptoms associated with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV). LIV Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:587–626. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70899-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin EC. Neonatal neoplasms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:171–8. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin N, Becquet F, Dureau P, et al. Particularités cliniques des gliomes du chiasma. Etude rétrospective sur une série de 18 patients. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2000;23:694–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard GM, Ellsworth RM. Differential diagnosis of retinoblastoma. A statistical survey of 500 children. I. Relative frequency of the lesions which simulate retinoblastoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965a;60:610–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard GM, Ellsworth RM. Differential diagnosis of retinoblastoma. A statistical survey of 500 children. II. Factors relating to the diagnosis of retinoblastoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965b;60:618–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivelä T. Trilateral retinoblastoma: a meta-analysis of hereditary retinoblastoma associated with primary ectopic intracranial retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1829–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maat-Kievit JA, Oepkes D, Hartwig NG, et al. A large retinoblastoma detected in a fetus at 21 weeks of gestation. Prenat Diagn. 1993;13:377–84. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970130510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney MC, Burnett WS, Majerovics A, et al. The epidemiology of ophthalmic malignancies in New York State. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1143–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32445-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga E, Minoda K, Sasaki MS. Parental age and seasonal variation in the births of children with sporadic retinoblastoma: a mutation-epidemiologic study. Hum Genet. 1990;84:155–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00208931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin C, Levin AV. The red reflex. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:137–40. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000199567.87134.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RW. Fifty-two forms of childhood cancer: United States mortality experience, 1960–1966. J Pediatr. 1969;75:685–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(69)80466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll AC, Imhof SM, Bouter LM, et al. Second primary tumors in patients with retinoblastoma. A review of the literature. Ophthalmic Genet. 1997;18:27–34. doi: 10.3109/13816819709057880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll AC, Imhof SM, Schouten-Van Meeteren AY, et al. Second primary tumors in hereditary retinoblastoma: a register-based study, 1945–1997: is there an age effect on radiation-related risk? Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1109–14. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan G. Diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1971;55:600. doi: 10.1136/bjo.55.9.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munier F, Balmer A. Rétinoblastome: génétique. In: Zografos L, editor. Tumeurs intraoculaires. Paris: Société Française d’Ophtalmologie et Masson; 2002. pp. 467–80. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer EA, Hardy RJ, Dobson V, et al. 15-year outcomes following threshold retinopathy of prematurity: final results from the multicenter trial of cryotherapy for retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:311–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa CF, Hoyt CS, Lesser RL, et al. Spontaneous regression of optic gliomas: thirteen cases documented by serial neuroimaging. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:516–29. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese AB. Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. The Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1955;40:317–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(55)91866-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scat Y, Liotet S, Carre F. Etude épidémiologique de 1705 tumeurs malignes de l’oeil et de ses annexes. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1996;19:83–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Luo CK, et al. Optical coherence tomography in children: analysis of 44 eyes with intraocular tumors and simulating conditions. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2004;41:338–44. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20041101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JA, Parsons HM, Shields CL, et al. Lesions simulating retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1991;28:338–40. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19911101-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JA, Shields CL, Honavar SG, et al. Clinical variations and complications of Coats disease in 150 cases: the 2000 Sanford Gifford Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:561–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JA, Shields CL, Parsons HM. Differential diagnosis of retinoblastoma. Retina. 1991;11:232–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach M, Balmer A, Munier F, et al. Shorter time to diagnosis and improved stage at presentation in Swiss patients with retinoblastoma treated from 1963 to 2004. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1493–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanoff M, Zimmerman LE, Davis RL. Massive gliosis of the retina. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1971;11:211–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]