Abstract

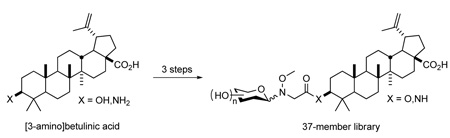

Using neoglycosylation, the impact of differential glycosylation upon the divergent anticancer and anti-HIV properties of the triterpenoid betulinic acid (BA) was examined. Each member from a library of 37 differentially glycosylated BA variants was tested for anticancer and anti-HIV activities. Enhanced analogs for both desired activities were discovered with the corresponding antitumor or antiviral enhancements diverging, based upon the appended sugar, into two distinct compound subsets.

The sugars attached to pharmaceutically important natural products often dictate key pharmacological properties and/or molecular mechanism of action.1 While there is also precedent for improving non-glycosylated natural product-based therapeutics via glycoconjugation, including colchicine,2 mitomycin,3 podophyllotoxin,4 rapamycin,5 or taxol,6 studies designed to systematically understand and/or exploit the role of carbohydrates in drug discovery are often limited by the availability of practical synthetic and/or biosynthetic tools.7 Neoglycosylation takes advantage of a chemoselective reaction between free reducing sugars and N-methoxyamino-substituted acceptors.8 This reaction has enabled the process of ‘neoglycorandomization’ wherein alkoxyamine-appended natural product-based drugs are differentially glycosylated with a wide array of natural and unnatural reducing sugars.2,9 Neoglycorandomization has led to increases in anticancer efficacy of the cardenolide digitoxin, 9a,9c mechanistic alteration and improvements in the synergistic effects of the non-glycosylated alkaloid colchicine,2 and enhancements in the potency of the glycopeptide vancomycin against antibiotic resistant organisms.9b

Many natural products are known to exhibit multiple, diverse biological activities.10 To assess the impact of differential glycosylation upon a natural product with known multiple activities, we selected the lupane-type triterpernoid betulinic acid (BA, 1) as a model. BA, and its reduced form (betulin, 2), exhibit a wide variety of biological functions, the most prevalent of which are anticancer and anti-HIV activities.11 In cancer cells, BA induces apoptosis through multiple mechanisms, including disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential and suppression of vascular endothelial growth factor and survivin proteins.12 Although the exact mechanism of BA anti-HIV activity has yet to be elucidated, many BA analogs disrupt viral fusion to host cells through interference with the gp41 viral glycoprotein or function as inhibitors of the late stage of capsid protein maturation.13

While BA derivatization (primarily at C3 and/or C28) has yielded anti-HIV or antitumor enhancements,11,14 few glycosylated BAs have been pursued or studied. Studies by Pichette and coworkers revealed that the attachment of saccharides at C3 moderately improved the antiproliferative activity (up to 4-fold) and selectivity of BA in a sugar-dependent manner.15 However, only d-Ara, d-Gal, d-Glc, d-Man, l-Rha, and d-Xyl were employed in this initial study and antiviral activity was not assessed. To more systematically assess the impact of BA glycosylation upon both anticancer activity/selectivity and antiviral activity in parallel, herein we report the synthesis and anticancer/antiviral activities of a 37-member library of BA C3-neoglycosides. Our findings indicate that groups of BA derivatives with improved antitumor or antiviral properties are divergent and sugar-dependent.

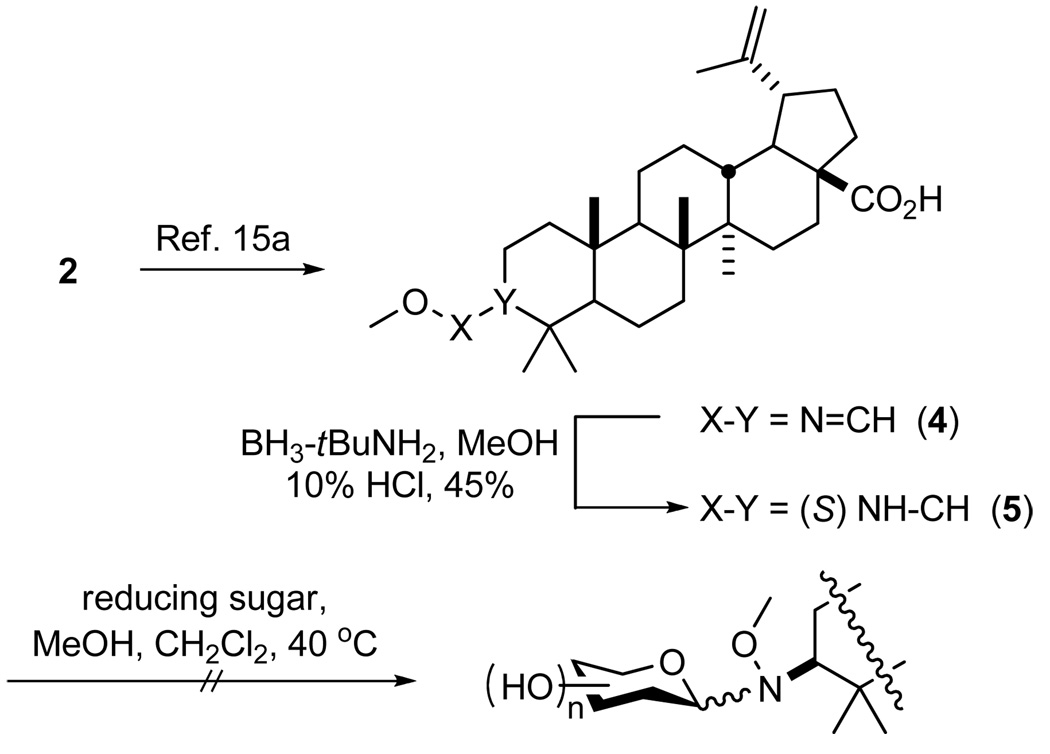

The initial strategy for methoxyamine handle installation at C3 involved reduction of imine 4 (created from 2)15a using BH3•t-BuNH2 to give a 3:1 ratio of desired (5) to undesired diastereomers (see Scheme 1). However, neoglycosylation of 5 failed possibly due to the hindered adjacent C4 dimethyl substitution. Consistent with this, aglycon 5 was also resistant to acetylation conditions (i.e., Ac2O, DMAP, refluxing pyridine).

Scheme 1.

Attempted Direct Neoglycosylation of Betulinic Acid

Previously, colchicine neoglycosylation was enabled by replacing the natural colchicine N-acetyl group with N-(N’-methoxyglycine).2 While not a direct neoglycosylation of BA, we postulated that a similar methoxyglycine handle would distance the hindered BA C4 quaternary center from the requisite neoglycosylation alkoxyamine. Toward this goal, 1 (prepared in three steps from 2)16 was esterified at the C3 hydroxyl group using chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of DMAP. Under Finklestein conditions, the chloride (6) was exchanged with iodide to facilitate the SN2 displacement by methoxyamine in the same reaction vessel (see Scheme 2). This three step procedure provided aglycon 7 in good yield (58%), a marked improvement over the previous colchicine N’-methoxyglycine incorporation strategy (eight steps, 40% yield).2

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Betulinic Acid Neoglycosides

Optimal neoglycosylation conditions of 7 were identified using l-ribose (see Table S1, Supporting Information), validating, for the first time, an ester-linked neoglycosylation handle. In contrast to the typical DMF:acetic acid (3:1) neoglycosylation solvent system,2,8,9 we found 6:1 MeOH:CH2Cl2 to be optimal. Notably distinct from prior neoglycosylation applications,2,8,9 an external proton source was also unnecessary, likely due to the intrinsic carboxylic acid of 7. Production of the corresponding neoglycoside library (BA1-32, see Figure S1) employed similar conditions (90 µM aglycon, 3 eq. sugar, 40 °C, 48 hr), with an average isolated yield of 33%. Unlike previously reported libraries that revealed a predominance of β-anomers,8,9 the anomeric bias in the context of BA neoglycosylation was not as strong (see Table S2).

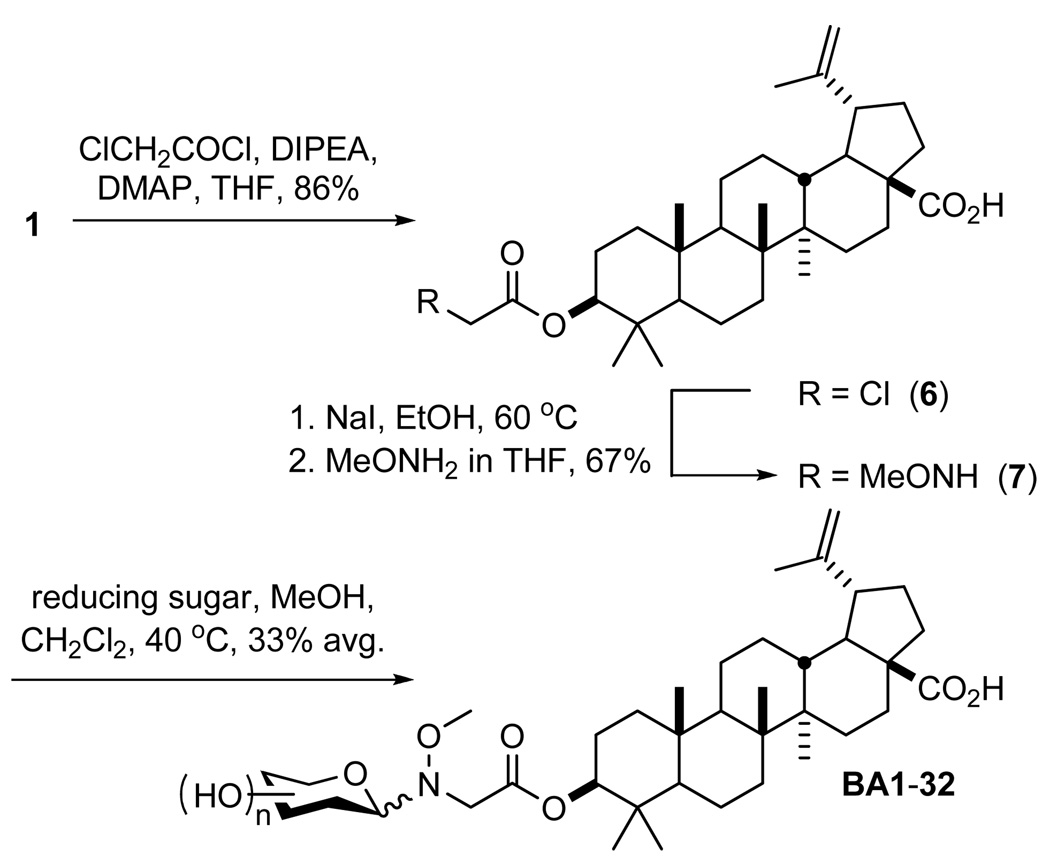

The cytoxicity of the library members was assessed in seven human cancer cell lines representing a broad range of carcinomas including breast, colorectal, CNS, lung and prostate. Two standards, 1 (the parent natural product) and 2 (betulin) were also examined. Eleven library members displayed IC50 values below a threshold of 25 µM (~ 2–3-fold the activity of 1) in at least one cell line, four of which (d-alloside BA1, d-altroside BA3, l-fucoside BA9, and Lxyloside BA32) were equipotent to the parent in one or more cell lines (see Figure 2 and Table S3).

Figure 2.

a) Divergent activity of betulinic acid neoglycosides against HIV-1-infected CEM-SS cells and A549 cancer cells compared to parent 1. b) Structures of most-active neoglycosides and their anomeric ratios (α:β).

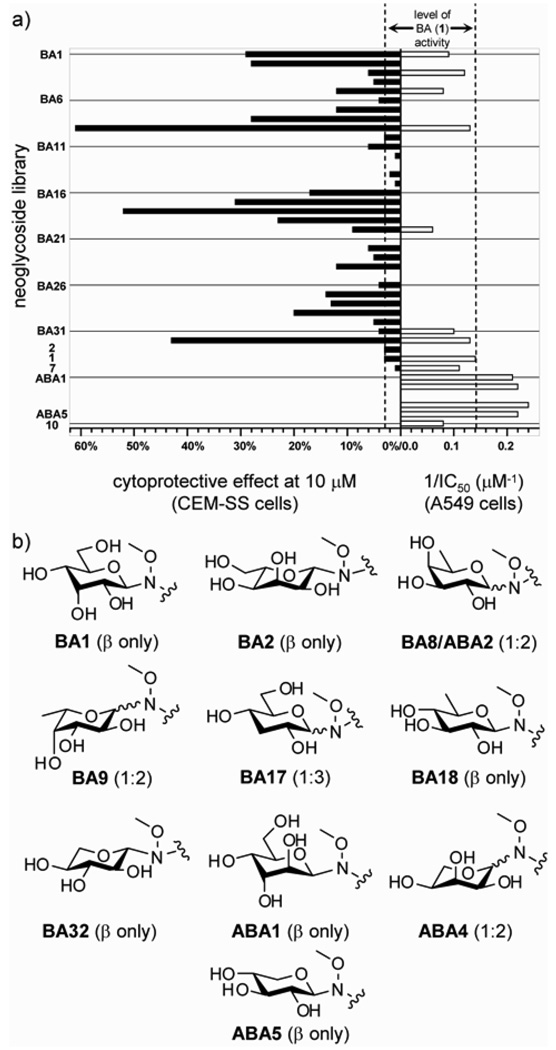

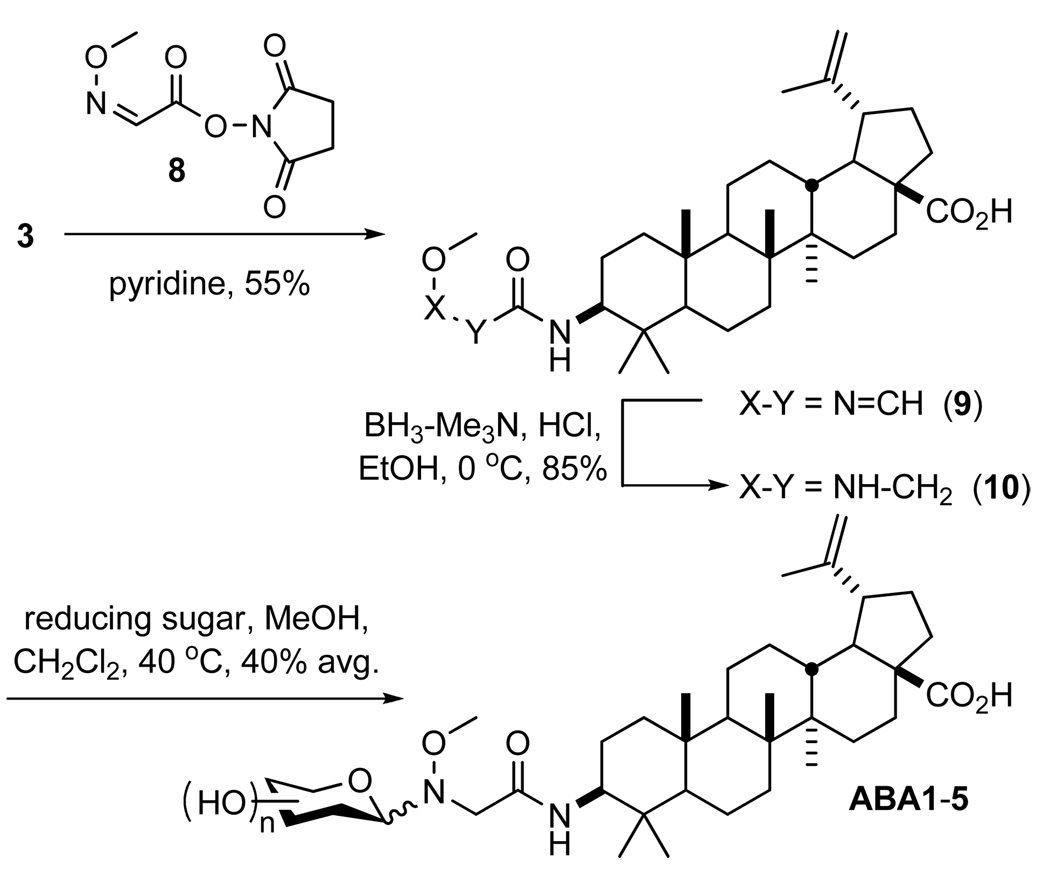

To assess the impact of the ester linker on this activity, a subset of representative amide-linked neoglycosides was subsequently synthesized. This group was designed to represent diverse sugar structures and a range of potencies (as defined by the ester-linked series) – specifically, one equipotent hexose (d-altrose), a ‘lower threshold’ (IC50 ~10–20 µM) pentose (d-xylose), an ‘upper threshold’ (IC50 ~15–25 µM) hexosuronic acid (d-glucuronate), and a representative threshold (IC50 ≥25 µM) pentose (l-ribose) and deoxyhexose (d-fucose). To circumvent the need for BA C28 acid protection during C3 acylation,17 N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester 8 was reacted with 3 in pyridine (see Scheme 3) and the resulting imine (9) reduced with BH3•Et3N complex in the presence of ethanolic HCl to provide aglycon 10 in good yield (85%). Neoglycosylation of 10 was performed as described above for ester 7, employing identical conditions to produce ABA1-5 (see Figure S1) with an average isolated yield of 40%. These five compounds had a notably decreased bias toward the β-anomer and expectantly displayed the same anomeric ratios as their ester analogs (see Table S2).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 3-Aminobetulinic Acid Neoglycosides

The cytoxicity of ABA1-5 was evaluated in five human cell lines of breast, colorectal, lung and prostate carcinomas. Interestingly, although aglycons 7 and 10 displayed relatively similar potencies to parent 1, the activities of four (d-altroside ABA1, d-fucoside ABA2, l-riboside ABA4, and d-xyloside ABA5) of the five glycosylated ABA subset were slightly improved over the parent natural product (~2-fold). A comparison of the ester-linked and amide-linked series also revealed clear improvements (2- to ≥5-fold) with these same four sugars in the ABA group (see Figure 2 and Table S3). While it is tempting to attribute this amide-versus-ester trend simply to the potential stability differences of the neoglycosylation linkers, the differences in magnitude of potency improvement (e.g., ≤2-fold for d-xylosides BA31 versus ABA5 compared to ≥6-fold for l-ribosides BA29 versus ABA4) or cell line selectivity (e.g., a reversal in potency trend between amide series ABA1/ABA3/ABA5 and ester series BA3/BA20/BA31 in HT-29) may contradict this straightforward explanation. It is also important to note that there appears to be no correlation between the current study and the previous Pichette O-glycoside study. For example, the best sugar in the context of direct C3-O-glycosylation, l-rhamnose,15 was inactive in the context of an ester-linked neoglycoside (BA27, ≥25 µM). In a similar manner, one of the best sugars in the context of either neoglycosylation approach, d-xylose (BA31 and ABA5), led to a slight decrease in potency as the C3-O-glycoside.15

To assess the corresponding impact of differential glycosylation upon antiviral activity, the entire set of compounds was subsequently tested in a single dose (10 µM) anti-HIV-1 assay against CEM-SS cells (i.e., CD4+ T lymphocytes) infected with the IIIB strain of HIV-1.18 Compound efficacy was determined by the percent increase of cytoprotective effect (CPE), which is prevention of intercellular virus replication, over untreated HIV-1-infected cells. Under these conditions, 19 of 32 ester-linked compounds displayed at least a 2-fold improvement over parent 1 with seven (d-alloside BA1, l-alloside BA2, d-fucoside BA8, l-fucoside BA9, 3- BA17 and 6-deoxy-d-glucoside BA18, and l-xyloside BA32) displaying ≥10-fold enhancements (the most active being ~20-fold better than parent 1, see Figure 2 and Table S4). It is important to note that at 10 µM, host cell cytotoxicity of the ester series was not a contributing factor as only 4 of the 32 esters led to ≥10% reduction of host cell viability. In contrast, antiviral activity could not be achieved without significant host cell cytotoxicity with amides ABA1-5 or aglycon 10. Dilution of the amide series to 1 µM abated host cell cytotoxicity, yet only d-glucuronide ABA3 demonstrated any significant CPE (32% increase in CPE), while 10 had no noticeable activity at 1 µM (see Table S4).

In summary, neoglycosylation has enabled the study of the influence of glycodiversification upon the divergent activities of BA. This study revealed distinct sets of sugars to discretely augment either the anticancer or anti-HIV activity of BA, the more dramatic of the two being the latter. While the anticancer or anti-HIV activites of BA neoglycosides were predominately dictated by the appended sugar, the nature of the alkoxyamine handle connection to the scaffold (i.e., ester versus amide) also appeared to contribute to the divergence of the mode of action. As a first application of neoglycosylation toward a triterpenoid and the first installation of the methoxyamine handle via a linker strategy, this study also significantly extends the utility of neoglycosylation as a tool for natural product glycodiversification.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures, figures and characterization of BA1-32 and ABA1-5, comprehensive assay data, and NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

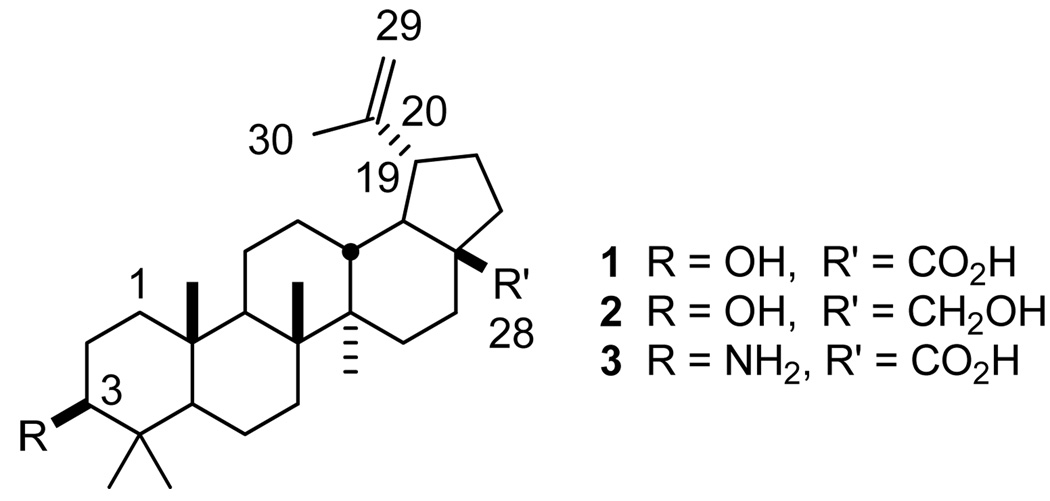

Figure 1.

Structures of betulinic acid (1), betulin (2), and 3-aminobetulinic acid (3).

Acknowledgment

We thank the School of Pharmacy Analytical Instrumentation Center for analytical support and the Keck UWCCC Small Molecule Screening Facility for cancer cell line cytotoxicity screening. This work was supported by the NIH (U19 CA113297 and AI52218).

References

- 1.(a) Kren V, Řezanka T. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:858–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thorson JS, Hosted TJ, Jr, Jiang J, Biggins JB, Ahlert J. Curr. Org. Chem. 2001;5:139–167. [Google Scholar]; (c) Weymouth-Wilson AC. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997;14:99–110. doi: 10.1039/np9971400099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed A, Peters NR, Fitzgerald MK, Watson JA, Jr, Hoffmann FM, Thorson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14224–14225. doi: 10.1021/ja064686s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghiorghis A, Talebian A, Clarke R. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1992;29:290–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00685947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imbert TF. Biochimie. 1998;80:207–222. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(98)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abel M, Szweda R, Trepanier D, Yatscoff RW, Foster RT. U.S. Patent 7,160,867. Rapamycin Carbohydrate Derivatives. 2007 January 9;

- 6.Liu D, Sinchaikeul S, Reddy PVG, Chang M, Chen S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:617–620. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Salas JA, Méndez C. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:119–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thibodeaux CJ, Melançon CE, Liu H. Nature. 2007;446:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/nature05814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Blanchard S, Thorson JS. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Griffith BR, Langenhan JM, Thorson JS. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2005;16:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Langenhan JM, Griffith BR, Thorson JS. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1696–1711. doi: 10.1021/np0502084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Peri F, Dumy P, Mutter M. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:12269–12278. [Google Scholar]; (b) Peri F, Deutman A, La Ferla B, Nicotra F. Chem. Commun. 2002:1504–1505. doi: 10.1039/b203605c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Carrasco MR, Nguyen MJ, Burnell DR, MacLaren MD, Hengel SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:5727–5729. [Google Scholar]; (d) Carrasco MR, Brown RT. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:8853–8858. doi: 10.1021/jo034984x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Carrasco MR, Brown RT, Serafimova IM, Silva O. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:195–197. doi: 10.1021/jo026641p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Peri F. Minirev. Med. Chem. 2003;3:658–665. [Google Scholar]; (g) Peri F, Jiménez-Barbero J, García-Aparicio V, Tvaroška I, Nicotra F. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:1433–1444. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Peri F, Nicotra F. Chem. Commun. 2004:623–627. doi: 10.1039/b308907j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Langenhan JM, Thorson JS. Curr. Org. Syn. 2005;2:59–81. [Google Scholar]; (j) Carrasco MR, Brown RT, Doan VH, Kandel SM, Lee FC. Biopolymers. 2006;84:414–420. doi: 10.1002/bip.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Nicotra F, Cipolla L, Peri F, La Ferla B, Redaelli C. Adv. Carb. Chem. Biochem. 2008;61:363–410. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(07)61007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Langenhan JM, Peters NR, Guzei IA, Hoffman MA, Thorson JS. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:12305–12310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503270102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Griffith BR, Krepel C, Fu X, Blanchard S, Ahmed A, Edmiston CE, Thorson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8150–8155. doi: 10.1021/ja068602r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Langenhan JM, Engle JM, Slevin LK, Fay LR, Lucker RW, Smith KR, Endo MM. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:670–673. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Deorukhkar A, Krishnan S, Sethi G, Aggarwal BB. Exp. Opin. Inv. Drugs. 2007;16:1753–1773. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.11.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Butler MS. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008;25:475–516. doi: 10.1039/b514294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Udenigwe CC, Ramprasath VR, Aluko RE, Jones PJH. Nutr. Rev. 2008;8:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Saladino R, Gualandi G, Farina A, Crestini C, Nencioni L, Palamara AT. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:1500–1519. doi: 10.2174/092986708784638889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For reviews see: Cichewicz RH, Kouzi SA. Med. Res. Rev. 2004;24:90–114. doi: 10.1002/med.10053. Yogeeswari P, Sriram D. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:657–666. doi: 10.2174/0929867053202214. Sami A, Taru M, Salme K, Jari Y-K.Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 2006291–13.16716572 Fulda S. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008;9:1096–1107. doi: 10.3390/ijms9061096.

- 12.(a) Schmidt ML, Kuzmanoff KL, Ling-Indeck L, Pezzuto JM. Eur. J. Cancer. 1997;33:2007–2010. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fulda S, Jeremias I, Steiner HH, Pietsch T, Debatin K-M. Int. J. Cancer. 1999;82:435–441. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990730)82:3<435::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Ramaiah SK, Safe S. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2816–2823. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Li F, Goila-Gaur R, Salzwedel K, Kilgore NR, Reddick M, Matallana C, Castillo A, Zoumplis D, Martin DE, Orenstein JM, Allaway GP, Freed EO, Wild CT. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:13555–13560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234683100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aiken C, Chen CH. Trends Mol. Med. 2005;11:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Kim DSHL, Pezzuto JM, Pisha E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:1707–1712. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kashiwada Y, Chiyo J, Ikeshiro Y, Nagao T, Okabe H, Cosentino LM, Fowke K, Lee KH. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:183–185. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Gauthier C, Legault J, Lebrun M, Dufour P, Pichette A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:6713–6725. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thibeault D, Gauthier C, Legault J, Bouchard J, Dufour P, Pichette A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:6144–6157. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DSHL, Chen Z, Nguyen VT, Pezzuto JM, Qiu S, Lu Z-Z. Synth. Commun. 1997;27:1607–1612. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashiwada Y, Chiyo J, Ikeshiro Y, Nagao T, Okabe H, Cosentino LM, Fowke K, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee K-H. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000;48:1387–1390. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures, figures and characterization of BA1-32 and ABA1-5, comprehensive assay data, and NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.