Abstract

Elevated ambient levels of particulate matter air pollution are associated with excess daily mortality, largely attributable to increased rates of cardiovascular events. We have previously reported that particulate matter induces p53-dependent apoptosis in primary human alveolar epithelial cells. Activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by p53 often requires the transcription of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins Noxa, Puma, or both. In this study, we exposed alveolar epithelial cells in culture and mice to fine particulate matter <2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5) collected from the ambient air in Washington, D. C. Exposure to PM2.5 induced apoptosis in primary alveolar epithelial cells from wild-type but not Noxa−/− mice. Twenty-four hours after the intratracheal instillation of PM2.5, wild-type mice showed increased apoptosis in the lung and increased levels of mRNA encoding Noxa but not Puma. These changes were associated with increased permeability of the alveolar-capillary membrane and inflammation. All of these findings were absent or attenuated in Noxa−/− animals. We conclude that PM2.5-induced cell death requires Noxa both in vitro and in vivo and that Noxa-dependent cell death might contribute to PM-induced alveolar epithelial dysfunction and the resulting inflammatory response.—Urich, D., Soberanes, S., Burgess, Z., Chiarella, S. E., Ghio, A. J., Ridge, K. M., Kamp, D. W., Chandel, N. S., Mutlu, G. M., Budinger, G. R. S. Proapoptotic Noxa is required for particulate matter-induced cell death and lung inflammation.

Keywords: apoptosis, oxidant, bax, air pollution

The acute exposure of populations to ambient particulate matter air pollution <2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5) has been associated with increases in daily mortality, primarily attributable to an increase in fatal cardiovascular events (1,2,3). Exposures to higher levels of PM2.5 have been associated with increased hospitalizations for myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure, and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma (4,5,6,7). Longer-term exposure to PM2.5 has been associated with an increase in atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, increased rates of lung cancer and impaired lung development in children (8, 9).

Ambient urban particulate matter is composed of a core of ash or carbon, the surface of which is coated with organic molecules and transition metals (10, 11). Inhaled particles are thought to gain access to cells within the lung and perhaps other tissues, where they interact with membrane-bound or intracellular proteins to generate superoxide anion and other reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are required for the biological response to the particles (12, 13). We have previously reported that exposure of cultured alveolar epithelial cells from rats and humans to PM <10 μm in diameter (PM10) caused p53-dependent activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway through a mechanism that requires the generation of ROS from the mitochondria (14).

The induction of apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway requires activation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins Bax or Bak, which is, in turn, regulated by one or more of a group of proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins that contain only a single BH domain (BH3 domain-only proteins) (15). Apoptosis induced by p53 has been shown to be regulated by the BH3 domain-only proteins Noxa and Puma (16). Consistent with these observations, we found that PM2.5-induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells requires the p53-dependent activation of Noxa. The function of Noxa appears to be restricted to its role in the activation of apoptosis but is dispensable for normal development. We therefore reasoned that Noxa−/− mice could be used to examine the importance of apoptosis in the acute response to PM2.5 exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PM2.5

The PM2.5 was obtained from the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (Gaithersburg, MD, USA; NIST SRM 1649: Filter-Based Fine Particulate Material). The characteristics of the PM2.5 have been previously described (17). Titanium dioxide (TiO2) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Antibodies and reagents

The following antibodies were used: cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) (catalog 9661; Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA), Mcl-1 (catalog 4572; Cell Signaling). Cell culture reagents were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc./Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Animals and intratracheal administration of particulate matter

The protocol for the use of mice was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Northwestern University. Six- to 8-wk-old (weighing 20–25 g), male, C57BL/6 mice (wild-type mice) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Mice with targeted deletion of Noxa (Noxa−/−) or Puma (Puma−/−) were backcrossed for more than 12 generations onto the C57BL/6 background and were a kind gift of Dr. Andreas Strasser (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Australia) (18). Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg i.p.) and intubated orally with a 20-gauge angiocath (19). We instilled either PM2.5 or TiO2 suspended in 50 μl of sterile PBS or 50 μl of sterile PBS (control) in 2 equal aliquots, 3 min apart. The particulate matter and TiO2 stocks were vortexed prior to instillation. After each aliquot the mice were placed in the right and then the left lateral decubitus position for 10–15 s.

Histology

A 20-gauge angiocath was sutured into the trachea, the lungs and heart were removed en bloc, and the lungs were inflated to 15 cm of H2O with 4% paraformaldehyde. The heart and lungs were fixed in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (13).

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) analysis

A BAL was performed through a 20-gauge angiocath ligated into the trachea. A 0.8-ml aliquot of PBS was instilled into the lungs and then carefully aspirated 3 times. A 200-μl aliquot of the BAL fluid was placed in a cytospin and centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min. The glass slides were Wright stained and subjected to a masked manual cell count and differential. The remaining BAL fluid was centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was used for the measurement of BAL protein (Bradford) and cytokine analysis (13).

Isolation and culture of alveolar epithelial cells

Alveolar type II cells were isolated from wild-type and Noxa−/− mice. Briefly, the lungs were perfused via the pulmonary artery, lavaged, and digested with elastase (1 mg/ml, Worthington). The cells were purified by negative immunoselection by using magnetic beads, followed by differential adherence to CD90 pretreated dishes. Cell viability was assessed by Trypan blue exclusion (>95%). Cells were cultured at an air–liquid interface on 0.4-μm transwell membranes inserted into 6-well culture dishes to eliminate fibroblast contamination. Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C and used within 4 d of isolation (20). Alveolar type II cells were also isolated from rats, as described previously (13) and used 2 d after isolation. A549 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. All cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were exposed to anoxia in an Invivo2 400 CMV400 hypoxia workstation (Biotrace International, St. Paul, MN, USA) maintained at 0% O2, as described previously (21).

Assessment of lung permeability was performed using a modification of a previously described technique (20). Twenty-four hours after treatment with either PM2.5 at varying doses or PBS, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and 125 μl of fluorescein isothiocynate-dextran (MW 4000 or 40,000) 0.05 g/ml (Sigma-Aldrich) was delivered into the retro-orbital plexus. The mice were kept sedated for 30 min, after which a 20-gauge angiocath was sutured into the trachea for the collection of BAL fluid. Immediately following the BAL, 400 μl of blood was collected from the right ventricle into a syringe containing 50 μl of sodium citrate (3.2%). Relative lung permeability was estimated from the difference in the fluorescence of the plasma, and the BAL fluid was measured by using a microplate reader (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 530 nm). BAL fluid protein levels were measured on freshly obtained unspun samples using a DC protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

DNA fragmentation

DNA fragmentation was assessed using a commercially available photometric immunoassay that detects histone-associated DNA fragments (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), according to the manufacturer’s directions, as we have previously described (14).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining in alveolar epithelial cells

Staining for TUNEL using the ApopTag Plus Fluorescein in situ Apoptosis Detection kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s directions. Briefly, cells were washed twice with PBS and detached with Trypsin-EDTA (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA, USA). Cells collected with the PBS were combined with cells detached from the transwell, centrifuged (5 min, 600 g), and resuspended in PBS (1×107 cells/ml). Twenty-five microliters of that solution was placed on 75- × 25-mm glass slides (VWR, West Chester, PA, USA) and air-dried for 25 min at room temperature. Cells were then fixed 1 h with freshly prepared paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS, pH 7.4), washed with PBS, and permeabilized with ice-cold 0.1% Triton X–100 in 0.1% sodium citrate solution for 2 min on ice, washed again with PBS, and labeled with fluorescein-FragEL terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TDT) labeling mix with TDT for 1 h in high humidity and in the dark. Slides were washed twice with 0.05% Tween and twice with PBS before mounting with gelvatol using DAPI as counterstain. Approximately 10 high-power fields (×400) were randomly selected per slide and photographed using an Eclipse TE-2000 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). Positive nuclei and DAPI-positive nuclei were counted using ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Annexin V staining

Cells were dispersed by trypsin:EDTA (Mediatech, Inc.) 24 h posttreatment and washed in PBS (Invitrogen). Annexin V staining was then determined using the ApoAlert Annexin V kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA), as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, the cells were washed in 1× binding buffer by centrifugation and then resuspended in 200 μl of 1× binding buffer containing Annexin V (0.1 μg/ml) and PI (0.5 μg/ml). After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a DakoCytomation CyAn high-speed multilaser droplet cell sorter (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 535 nm; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) (22).

Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR measurement of RNA

Wild-type mice were treated with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal) or PBS and 12 h later the lungs were harvested for isolation of total RNA using a commercially available system (TRIzol, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting mRNA was reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and random decamers using a commercially available system, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Ambion, Austin TX, USA). QRT-PCR reactions were performed using IQ SYBR Green-superscript (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with the primers listed below and analyzed on an IQ5 Real-Time PCR Detection System. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were normalized to Ct values for ribosomal protein 18s, and data were analyzed using the Pfaffl method (23). The primer sequences used were Noxa (18): forward: GTCGGAACGCGCCAGTGAACCC, reverse: TCCTTCCTGGGAGGTCCCTTCTTGC; Slug (24): forward: GATGTGCCCTCAGGTTTGAT, reverse: ACACATTGCCTTGTGTCTGC; and 18s: forward: TGG CTC ATT AAA TCA GTT ATG GT, reverse: GTC GGC ATG TAT TAG CTC TAG.

Immunoblotting

Protein immunoblotting was performed as described previously (20). Cell lysates were mixed with sample loading buffer (125 mM Tris base (pH 6.8), 4% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 200 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.02% (w/v) bromphenol blue). After heating, the protein was resolved on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-15% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in TBS-T (100 mM Tris base (pH 7.5), 0.9% (w/v) NaCl, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20) for 2 h at room temperature and subsequently incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed with TBS-T three times and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The membrane was washed three times with TBS-T and analyzed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) (25).

TUNEL staining of lung sections

End labeling of exposed 3′-OH ends of DNA fragments in paraffin-embedded tissue was done utilizing the TUNEL AP In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics), according to manufacturer’s directions. After staining, 20 fields of alveoli (×400) were randomly chosen, and TUNEL-positive nuclei were counted using ImageJ software (20).

Measurement of cytokines in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

A cytometric bead array (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used to measure the levels of cytokines/chemokines in the BAL fluid. Samples were analyzed in triplicate using the Mouse Inflammation Kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

Differences between groups were explored using analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the ANOVA indicated a significant difference, individual differences were explored using t tests with a Dunnett or Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego CA, USA). Data are shown as means ± se.

RESULTS

Exposure to PM2.5 induces the expression of Noxa but not Puma in vitro and in vivo

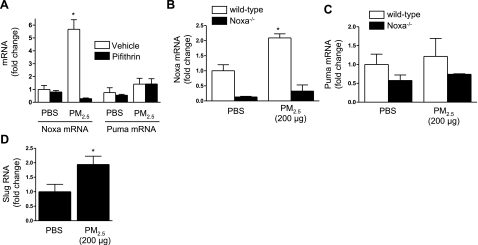

Apoptotic stimuli that activate the intrinsic pathway through p53 have been shown to induce the activation of the proapoptotic BH3 domain proteins Noxa, Puma, or both, which are upstream of the activation of Bax or Bak (18). Noxa sequesters proapoptotic or inhibits antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins to activate Bax or Bak and induce cell death, while Puma directly activates Bax or Bak (26). To examine the role of Noxa and Puma in PM2.5-induced cell death, we treated A549 cells with PM2.5 or PBS in the absence or presence of pifithrin (50 μM), an inhibitor of p53-mediated transcription (14). After 6 h, we harvested RNA from these cells and measured the levels of Noxa and Puma using real-time RT-PCR. Treatment with PM2.5 led to a significant increase in the level of Noxa but not Puma mRNA in untreated, but not pifithrin-treated cells (Fig. 1A). We then treated wild-type, Noxa−/−, and Puma−/− animals with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal) and 24 h later harvested the lungs for the isolation of total RNA. Compared with PBS-treated animals, PM2.5 treatment resulted in significantly higher levels of mRNA for Noxa in wild-type but not Noxa−/− animals (Fig. 1B). By contrast, PM2.5 failed to induce an increase in the abundance of mRNA for Puma in either wild-type or Noxa−/− animals (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Intratracheal instillation of PM2.5 induces the p53-dependent transcription of Noxa but not Puma. A) A549 cells were treated with PM2.5 (50 μg/cm2) in the presence or absence of the p53 inhibitor pifithrin (50 μM); 6 h later, abundance of mRNA encoding Noxa and Puma was measured using real-time RT-PCR. B, C) Wild-type and Noxa−/− mice were treated with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal); 24 h later, RNA was isolated from whole lung homogenates and analyzed for mRNA encoding Noxa (B) and Puma (C) using real-time RT-PCR. D) Wild-type animals were treated with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal); 24 h later, total RNA was isolated from lung homogenates for measurement of mRNA encoding Slug using real-time RT-PCR. n ≥ 4 for all conditions. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS-treated controls.

The activation of p53 in response to DNA damage can result in cell cycle arrest and DNA repair or the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. A transcriptional target of p53, Slug, has been shown to inhibit the transcription of Puma in response to the activation of p53 (27). In keratinocytes, Strasser and colleagues (16) reported that the activation of Slug by p53 accounted for the requirement for Noxa rather than Puma in the cell death induced by ionizing radiation. We sought to determine whether activation of Slug might account for our failure to observe increased Puma transcription in isolated cells or whole lungs following the instillation of PM2.5. We treated wild-type mice with PBS or PM2.5 and 24 h later harvested their lungs, isolated total RNA, and measured the levels of Slug mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Compared with PBS-treated mice, PM2.5-treated mice showed a significant increase in the levels of Slug mRNA in the lung (Fig. 1D).

Noxa is required for particulate matter-induced cell death in alveolar epithelial cells

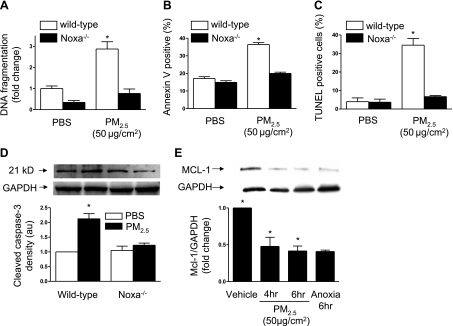

To determine whether Noxa is required for PM2.5-induced cell death, we isolated primary alveolar epithelial cells from wild-type and Noxa−/− animals and grew them on air-liquid interfaces. Two days after isolation, when the cells had formed a confluent monolayer, they were exposed to PM2.5 (50 μg/cm2) or PBS, and 24 h later cell death was measured. In alveolar epithelial cells from wild-type mice, treatment with PM2.5 caused cell death as assessed using DNA fragmentation (Fig. 2A), annexin V staining (Fig. 2B), TUNEL staining (Fig. 2C), and the cleavage of caspase-3 (Fig. 2D). In cells from Noxa−/− animals, cell death was similar in control and PM2.5-treated cells (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Noxa is required for PM2.5-induced cell death in alveolar epithelial cells. A–D) Primary alveolar type II cells were isolated from wild-type and Noxa−/− mice and grown on air liquid interfaces. On d 3, cells were treated with PM2.5 (50 μg/cm2) or vehicle; after 24 h, cell death was measured by DNA fragmentation (A), Annexin V staining (B), TUNEL staining (C), and caspase-3 cleavage (D). E) Primary rat alveolar type II cells were treated with vehicle or PM2.5 (50 μg/cm2) or treated with anoxia (0% O2), and cell lysates were immunoblotted using an antibody against Mcl-1; n = 3 for all measures. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated wild-type cells.

Exposure to PM2.5 is associated with the degradation of Mcl-1 in alveolar epithelial cells

One mechanism by which Noxa has been shown to induce apoptosis is through sequestration or degradation of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein Mcl-1 (26). We sought to determine whether the increase in Noxa that we observed in response to PM2.5 exposure was associated with a reduction in the levels of Mcl-1 in alveolar epithelial cells. We isolated primary alveolar epithelial cells from rats and exposed them to PM2.5 (50 μg/cm2). At 4 and 6 h after treatment with PM2.5, the cells were lysed, and the levels of Mcl-1 were assessed by immunoblotting. Treatment with PM2.5 resulted in a fall in the levels of Mcl-1 protein in alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. 2E). Exposure to anoxia (0% oxygen) was used as a positive control (21).

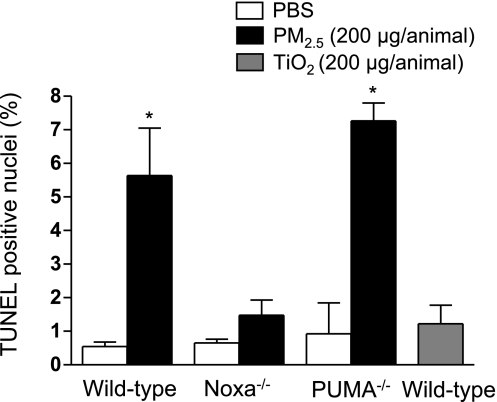

Exposure to PM2.5 induces Noxa-dependent apoptosis in the lung

We have reported that exposure to PM10 results in dose-dependent apoptosis in lung cells that is evident at doses greater than 10 μg/animal (14). To determine whether Noxa was required for PM2.5-induced cell death in the lung, we treated wild-type, Noxa−/−, and Puma−/− mice with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal) or PBS and 24 h later harvested the lungs. We then examined fixed lung sections from these animals for TUNEL-positive nuclei. Treatment with PM2.5 resulted in an increase in TUNEL-positive nuclei in wild-type and Puma−/− but not Noxa−/− animals, suggesting that Noxa is specifically required for PM2.5-induced apoptosis in the lung. Administration of a control particle, TiO2 (200 μg/animal), was not associated with a significant increase in the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Intratracheal instillation of PM2.5 results in Noxa- but not Puma-dependent apoptosis in the lungs of mice. Wild-type, Noxa−/−, and Puma−/− mice were treated with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal) intratracheally; 24 h later, lungs were harvested and fixed, and sections were examined for TUNEL-positive nuclei (×200). Average number of TUNEL-positive nuclei per high-power field in 10 fields. n ≥ 4 for wild-type and Noxa−/− animals; n = 3 for Puma−/− animals. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS-treated controls.

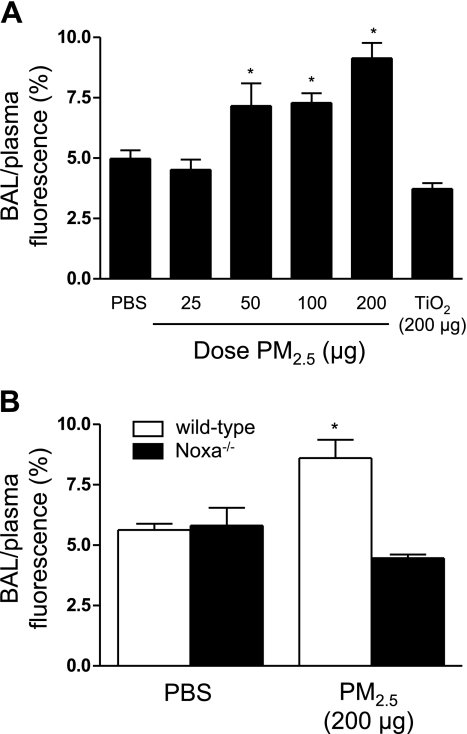

Noxa is required for the PM2.5-induced increase in the permeability of the alveolar-capillary barrier

To determine whether exposure to PM2.5 was associated with functional changes in the alveolar-capillary barrier, we treated wild-type animals with increasing doses of PM2.5 and measured the permeability of the alveolar-capillary membrane to small solutes using FITC-labeled dextran (4 kDa). Significant increases in permeability were observed in wild-type animals 24 h after the instillation of 100 or 200 μg of PM2.5 (Fig. 4A). Administration of a control particle (TiO2; 200 μg/animal) failed to increase the alveolar-capillary permeability beyond that observed in saline-treated animals (Fig. 4A). To determine whether Noxa-mediated cell death was required for the increase in permeability, we measured alveolar-capillary permeability in wild-type and Noxa−/− animals 24 h after treatment with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal). In contrast to wild-type animals, treatment with PM2.5 did not cause an increase in the alveolar-capillary permeability in Noxa−/− mice (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Exposure to PM2.5 increases permeability of the alveolar-capillary membrane. A) Wild-type mice were treated with PBS or PM2.5 or a control particle (TiO2) at doses indicated; 24 h later, alveolar-capillary permeability to a 4-kDa FITC-labeled dextran was measured. B) Wild-type and Noxa−/− mice were treated with PBS or PM2.5 (200 μg/animal); 24 h later, the same measurement was made. n ≥ 6 for all conditions. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS-treated wild-type animals.

PM2.5-induced lung inflammation is attenuated in Noxa−/− animals

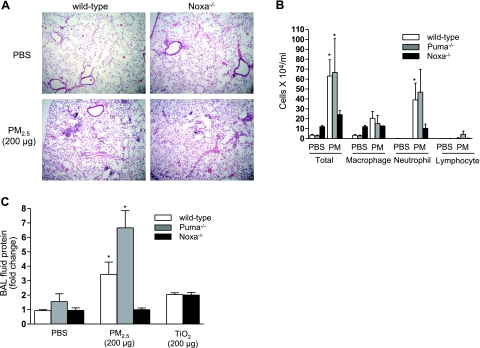

We and others have reported that treatment with PM2.5 induces a mild form of lung injury characterized by a mononuclear and neutrophilic inflammation (28, 29). To determine the contribution of Noxa-dependent apoptosis to the inflammatory response in the lung, we treated wild-type and Noxa−/− animals with PM2.5 (200 μg/animal), and 24 h later, we examined hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections for evidence of lung injury. The particulate matter and surrounding inflammatory cells were visible in the small airways of the wild-type and Noxa−/− animals (Fig. 5A). To determine whether the loss of Noxa or Puma prevented lung inflammation in response to PM2.5, we measured the cell count and differential in the BAL fluid from wild-type, Noxa−/−, and Puma−/− animals 24 h after treatment with PM2.5 or PBS. Compared with wild-type and Puma−/− animals, the PM2.5-induced increase in the BAL fluid cell count was attenuated in Noxa−/− mice. In all three groups, the increase in cells was attributable to an increase in both macrophages and neutrophils (Fig. 5B). The administration of a control particle, TiO2 (200 μg/animal), resulted in small increases in the BAL cell count in both wild-type and Noxa−/−animals (not shown). These results suggest that the loss of Noxa specifically attenuates the lung inflammation induced by particulate matter.

Figure 5.

Inflammatory response to PM2.5 is attenuated in Noxa−/− mice. A) Wild-type and Noxa−/− mice were treated with PM2.5; 24 h later, lung sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (×100). B, C) In a separate group of wild-type, Noxa−/−, and Puma−/− mice, BAL fluid was obtained and examined for cell count and differential and total BAL fluid protein 24 h after instillation of PM2.5. n ≥ 6 for all conditions for wild-type and Noxa−/− animals; n = 3 for Puma−/− animals. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS-treated wild-type animals.

To further assess the effects of Noxa-mediated cell death on the function of the alveolar-capillary barrier and lung inflammation, we measured the levels of protein in unspun BAL fluid collected from wild-type, Puma−/−, and Noxa−/− animals 24 h after exposure to PM2.5. The administration of PM2.5 (200 μg) to wild-type and Puma−/− mice resulted in an increase in the BAL fluid protein concentration; however, BAL protein levels did not increase in mice lacking Noxa (Fig. 5C). The administration of a control particle, TiO2 (200 μg), was associated with a small increase in BAL protein concentration in both wild-type and Noxa−/− mice (Fig. 5C).

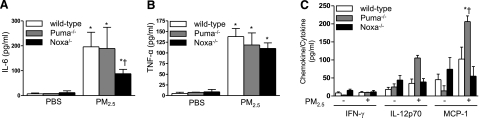

Noxa is required for the increase in IL-6 induced by PM2.5 exposure

We have reported that inflammatory cells within the lung, particularly alveolar macrophages release IL-6 and other proinflammatory cytokines that are detectable in the BAL fluid 24 h after the PM2.5 exposure (29). To determine the contribution of Noxa-dependent cell death to this response, we measured a panel of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the BAL fluid from wild-type, Puma−/−, and Noxa−/− mice 24 h after treatment with either PBS or PM2.5. Compared with PBS-treated mice, treatment of wild-type and Puma−/− mice with PM2.5 caused a significant increase in the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in the BAL fluid (Fig. 6A, B, respectively). Compared with wild-type and Puma−/− animals, the PM2.5-induced increase in the level of IL-6 in the BAL fluid was significantly lower in mice lacking Noxa (Fig. 6A). The levels of IL-12p70, IL-10, and MCP-1 were not significantly changed by treatment with PM2.5 in wild-type or Noxa−/− mice, but the levels of MCP-1 were significantly higher in the Puma−/− compared with the wild-type or Noxa−/− mice (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

PM2.5-induced lung cytokine release is reduced in Noxa−/− animals. Wild-type, Noxa−/−, and Puma−/− mice were treated with PM2.5; 24 h later, levels of proinflammatory cytokines were measured in BAL fluid: IL-6 (A); TNF-α (B); and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-12 p70 (IL-12), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) (C). n ≥ 6 for all conditions for wild-type and Noxa−/− animals, n = 3 for Puma−/− animals. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS-treated control animals; †P < 0.05 vs. wild-type and Noxa−/− animals.

DISCUSSION

Exposure to particulate matter is associated with increased short and long-term morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular diseases (1,2,3,4,5,6, 9). In addition, PM2.5 exposure has been associated with increased hospitalizations for stroke, exacerbation of congestive heart failure, and an increased incidence of lung cancer (30,31,32). We and others have reported that exposure of cells to high doses of PM2.5 is associated with apoptosis of lung epithelial cells; PM2.5 induces the mitochondrial generation of ROS, resulting in DNA damage and a p53-dependent activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (14, 33, 34). In this study, we found that transcription of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 protein Noxa was induced in alveolar epithelial cells and in the lungs of mice following exposure to PM2.5. PM2.5-induced apoptosis was attenuated in primary alveolar epithelial cells isolated from mice lacking Noxa. The instillation of PM2.5 induced modest levels of lung injury and pulmonary inflammation characterized by increases in the number of apoptotic cells in the lung, the permeability of the alveolar capillary to a labeled 4-kDa dextran, the number of inflammatory cells in the BAL fluid, the level of protein in the BAL fluid, and the concentration of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in the BAL fluid. All of these findings were absent or attenuated in mice lacking Noxa. By contrast, the number of apoptotic cells and the severity of PM2.5-induced inflammation was similar in wild-type and Puma−/− animals. These results suggest that Noxa-dependent apoptosis contributes to the inflammatory response to PM2.5.

Stimuli that result in DNA damage activate the tumor suppressor p53 (reviewed in ref. 35). The activation of p53 results in cell cycle arrest and the induction of DNA repair enzymes or activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Apoptosis mediated by p53 is largely the result of the transcriptional activation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, with an additional contribution from nontranscriptional mechanisms. The major transcriptional targets of p53 are the proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins Noxa and Puma (16, 36). Puma can directly activate Bcl-2 proteins capable of permeabilizing the outer mitochondrial membrane (Bax, Bak, or Bik). Noxa specifically antagonizes the activity of an antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein, Mcl-1, to release activator proteins that activate Bax or Bak (21, 26). Our findings suggest that PM2.5-induced activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway occurs primarily through the p53-mediated activation of Noxa, which results in the degradation of Mcl-1 and subsequent cell death.

Our findings parallel those reported by Strasser and colleagues (16), who examined the role of Noxa, Puma, and Bim in the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by ionizing radiation. Similar to our findings, they observed that mice lacking Noxa showed almost complete inhibition of apoptosis in skin exposed to ionizing radiation. Exposure of cells from wild-type and knockout animals to IR demonstrated a consistent increase in the abundance of Noxa following radiation, while an increase in Puma was observed only in some cells. The variability in the induction of Puma was inversely correlated with the activation of Slug. Slug is a zinc-finger protein that is both a transcriptional target of p53 and acts as a direct repressor of Puma transcription (27). As such, Slug is capable of modulating the p53 response to DNA damage by inhibiting Puma-mediated apoptosis, perhaps allowing for DNA repair. We observed that exposure to PM2.5 increased the transcription of Slug in mice.

Death of both alveolar epithelial and endothelial cells has long been recognized in the lungs of animals with lung injury (reviewed in ref. 37). Matute-Bello et al. (38) showed that direct activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway in the lung through the intratracheal administration of FasL was sufficient to induce lung injury. In an LPS model of lung injury, the same group of investigators reported that inhibition of Fas-mediated apoptosis attenuated the injury (39). We reported that activation of the intrinsic pathway through the proapoptotic protein Bid was required for the development of apoptosis and the lung injury observed after the intraperitoneal administration of LPS (40). In this study, we report that apoptosis induced by exposure to PM2.5 is required for the subsequent increase in alveolar-capillary permeability. Even more interesting, the prevention of apoptosis ameliorated the PM2.5-induced inflammatory response, suggesting that apoptosis induced by extrinsic stimuli might contribute to the development of inflammation. It is unlikely that the loss of Noxa in inflammatory cells explains our findings as the loss of other BH3 domain only proteins has been shown to enhance the inflammatory response in other forms of lung injury (20).

We have previously reported that the intratracheal instillation of PM induces dose-dependent increases in inflammation, alveolar epithelial dysfunction, and apoptosis in the lung and that these effects are evident even at doses to which a normal mouse would be exposed breathing air in a typical city in the United States (13). In this study, we observed small but significant increases in the permeability of the alveolar-capillary barrier to a small dextran molecule and an increase in the BAL fluid protein level at moderate doses of PM2.5. While the doses employed in this study are higher than those that would typically be experienced in the developed world, anatomic factors and regional heterogeneity of ventilation might result in the exposure of some regions of the epithelium to relatively high doses of PM (41, 42). This inequality of distribution is likely to be more pronounced in individuals with obstructive lung disease that exhibit regional heterogeneity of ventilation (12). Our results suggest that apoptosis occurring in lung regions exposed to relatively high concentrations of PM2.5 may contribute to lung inflammation, alveolar-capillary dysfunction and the adverse clinical outcomes associated with PM2.5 exposure.

Similar to other investigators, we observed an increase in the total number of inflammatory cells in the BAL fluid obtained from wild-type mice 24 h after exposure to PM2.5 compared with PBS. This increase in cells was attributable to an increase in the number of both macrophages and neutrophils. These findings were attenuated in Noxa−/− mice and were supported by analysis of total protein levels in unspun BAL fluid. The increase in inflammatory cells in the BAL fluid was reflected by an increase in the BAL levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α; however, there were minimal changes in the levels of other proinflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ, IL-12p70, and MCP-1. The increase in IL-6, but not TNF-α was attenuated in mice lacking Noxa. By contrast, mice lacking Puma had increased numbers of inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils and equal or higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines when compared with wild-type animals. We and others have reported that the administration of PM2.5 is associated with a disproportionate increase in IL-6 relative to other cytokines and that depletion of alveolar macrophages selectively attenuates this response (29, 43). Our results suggest that the prevention Noxa-dependent apoptosis might modulate the release of IL-6 by alveolar macrophages; however, the precise mechanisms by which this occurs are not clear.

Because we used mice globally deficient in Noxa, we are unable to conclude whether the alveolar epithelium is the only cell that undergoes apoptosis in response to PM2.5. It is possible that other lung cells (e.g., endothelial cells or inflammatory cells) undergo Noxa-dependent apoptosis, which might contribute to the physiological changes induced by the particles. Cell type-specific knockdown of Noxa in different cell types could be used to address these questions.

We previously reported that primary alveolar epithelial cells isolated from human lungs immediately postmortem and from rats underwent p53-dependent cell death in response to PM10 (14). We also reported that treatment with PM10 resulted in an increase in the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei in mouse lungs harvested 24 h after exposure and that some of these cells stain positively for the alveolar epithelial Type I cell marker T1α. The majority of our in vitro experiments were performed using primary alveolar Type II cells from mice and rats. When maintained in culture, these cells show a progressive loss of Type II cell markers and gain in Type I cell markers (44). Because of these limitations, it is not possible for us to conclude whether Type I or Type II alveolar epithelial cells are more susceptible to PM2.5 induced apoptosis.

In conclusion, the intratracheal administration of PM2.5 into the lungs of mice results in apoptosis that requires the proapoptotic Bcl-2 protein Noxa. Mice lacking Noxa failed to demonstrate apoptosis in the lung after the instillation of PM2.5 and were resistant to the PM2.5-induced increase in alveolar-capillary permeability and lung inflammation. Our results provide a novel link between the apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells and the inflammatory response elicited by acute exposure to PM2.5.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jacob Sznajder and Dr. David Green for their advice during the performance of these experiments and preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants HL071643, GM060472, HL067835, ES015024, and ES013995, and by The American Lung Association.

References

- Dominici F, McDermott A, Zeger S L, Samet J M. National maps of the effects of particulate matter on mortality: exploring geographical variation. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:39–44. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Samoli E, Gryparis A, Le Tertre A, Monopolis Y, Rossi G, Zmirou D, Ballester F, Boumghar A, Anderson H R, Wojtyniak B, Paldy A, Braunstein R, Pekkanen J, Schindler C, Schwartz J. Confounding and effect modification in the short-term effects of ambient particles on total mortality: results from 29 European cities within the APHEA2 project. Epidemiology. 2001;12:521–531. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet J M, Dominici F, Curriero F C, Coursac I, Zeger S L. Fine particulate air pollution and mortality in 20 U.S. cities, 1987–1994. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1742–1749. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery D W, Pope C A, 3rd, Xu X, Spengler J D, Ware J H, Fay M E, Ferris B G, Jr, Speizer F E. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C A, III, Burnett R T, Thurston G D, Thun M J, Calle E E, Krewski D, Godleski J J. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation. 2004;109:71–77. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey D E, Mills P K, Petersen F F, Beeson W L. Long-term ambient concentrations of total suspended particulates and oxidants as related to incidence of chronic disease in California Seventh-Day Adventists. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;94:43–50. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94-1567944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreanor J, Cullinan P, Nieuwenhuijsen M J, Stewart-Evans J, Malliarou E, Jarup L, Harrington R, Svartengren M, Han I K, Ohman-Strickland P, Chung K F, Zhang J. Respiratory effects of exposure to diesel traffic in persons with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2348–2358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs S H, Schindler C, Liu L J, Keidel D, Bayer-Oglesby L, Brutsche M H, Gerbase M W, Keller R, Kunzli N, Leuenberger P, Probst-Hensch N M, Tschopp J M, Zellweger J P, Rochat T, Schwartz J, Ackermann-Liebrich U. Reduced exposure to PM10 and attenuated age-related decline in lung function. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2338–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K A, Siscovick D S, Sheppard L, Shepherd K, Sullivan J H, Anderson G L, Kaufman J D. Long-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:447–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook R D, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith S C, Jr, Tager I. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunekreef B, Holgate S T. Air pollution and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Hao M, Phalen R F, Hinds W C, Nel A E. Particulate air pollutants and asthma. A paradigm for the role of oxidative stress in PM-induced adverse health effects. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:250–265. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu G M, Snyder C, Bellmeyer A, Wang H, Hawkins K, Soberanes S, Welch L C, Ghio A J, Chandel N S, Kamp D W, Sznajder J I, Budinger G R. Airborne particulate matter inhibits alveolar fluid reabsorption in mice via oxidant generation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:670–676. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0329OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soberanes S, Panduri V, Mutlu G M, Ghio A, Budinger G R, Kamp D W. p53 mediates particulate matter-induced alveolar epithelial cell mitochondria-regulated apoptosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1229–1238. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-203OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng E H, Wei M C, Weiler S, Flavell R A, Mak T W, Lindsten T, Korsmeyer S J. Bcl-2, bcl-x(l) sequester bh3 domain-only molecules preventing bax- and bak-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2001;8:705–711. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik E, Michalak E M, Villunger A, Adams J M, Strasser A. Ultraviolet radiation triggers apoptosis of fibroblasts and skin keratinocytes mainly via the BH3-only protein Noxa. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:415–424. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins F E, Huffman G P, Robertson J D. Speciation of elements in NIST particulate matter SRMs 1648 and 1650. J Hazard Mat. 2000;74:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(99)00195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villunger A, Michalak E M, Coultas L, Mullauer F, Bock G, Ausserlechner M J, Adams J M, Strasser A. p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins Puma and Noxa. Science. 2003;302:1036–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1090072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu G M, Dumasius V, Burhop J, McShane P J, Meng F J, Welch L, Dumasius A, Mohebahmadi N, Thakuria G, Hardiman K, Matalon S, Hollenberg S, Factor P. Upregulation of alveolar epithelial active Na+ transport is dependent on beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling. Circ Res. 2004;94:1091–1100. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125623.56442.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinger G R, Mutlu G M, Eisenbart J, Fuller A C, Bellmeyer A A, Baker C M, Wilson M, Ridge K, Barrett T A, Lee V Y, Chandel N S. Proapoptotic Bid is required for pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4604–4609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507604103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle J K, Shroff E H, Perlman H, Strasser A, Moraes C T, Flavell R A, Danial N N, Keith B, Thompson C B, Chandel N S. Loss of Mcl-1 protein and inhibition of electron transport chain together induce anoxic cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1222–1235. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01535-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Gurtu V, Kain S R, Yan G. Early detection of apoptosis using a fluorescent conjugate of annexin V. BioTechniques. 1997;23:525–531. doi: 10.2144/97233pf01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. [Online] Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson L G, Choi C, Newkirk K M, Parkhani J, Cooper K L, Lu P, Kusewitt D F. Ultraviolet radiation stimulates expression of Snail family transcription factors in keratinocytes. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:257–268. doi: 10.1002/mc.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinger G R, Tso M, McClintock D S, Dean D A, Sznajder J I, Chandel N S. Hyperoxia-induced apoptosis does not require mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and is regulated by Bcl-2 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15654–15660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Rafiuddin-Shah M, Tu H C, Jeffers J R, Zambetti G P, Hsieh J J, Cheng E H. Hierarchical regulation of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis by BCL-2 subfamilies. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1348–1358. doi: 10.1038/ncb1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W-S, Heinrichs S, Xu D, Garrison S P, Zambetti G P, Adams J M, Look A T. Slug antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors by repressing Puma. Cell. 2005;123:641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmar A, Nemery B, Hoet P H, Vermylen J, Hoylaerts M F. Pulmonary inflammation and thrombogenicity caused by diesel particles in hamsters: role of histamine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1366–1372. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-801OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu G M, Green D, Bellmeyer A, Baker C M, Burgess Z, Rajamannan N, Christman J W, Foiles N, Kamp D W, Ghio A J, Chandel N S, Dean D A, Sznajder J I, Budinger G R S. Ambient particulate matter accelerates coagulation via an IL-6 dependent pathway. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2952–2961. doi: 10.1172/JCI30639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C A, 3rd, Burnett R T, Thun M J, Calle E E, Krewski D, Ito K, Thurston G D. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellenius G A, Bateson T F, Mittleman M A, Schwartz J. Particulate air pollution and the rate of hospitalization for congestive heart failure among medicare beneficiaries in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:1030–1036. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellenius G A, Schwartz J, Mittleman M A. Air pollution and hospital admissions for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke among Medicare beneficiaries. Stroke. 2005;36:2549–2553. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189687.78760.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiura T S, Li N, Kaplan R, Horwitz M, Seagrave J C, Nel A E. The role of a mitochondrial pathway in the induction of apoptosis by chemicals extracted from diesel exhaust particles. J Immunol. 2000;165:2703–2711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay D, Panduri V, Ghio A, Kamp D W. Particulate matter induces alveolar epithelial cell DNA damage and apoptosis: role of free radicals and the mitochondria. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:180–187. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0269OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden K H, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell’s response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers J R, Parganas E, Lee Y, Yang C, Wang J, Brennan J, MacLean K H, Han J, Chittenden T, Ihle J N, McKinnon P J, Cleveland J L, Zambetti G P. Puma is an essential mediator of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Martin T R, Liles W C, Steinberg K P, Kiener P A, Mongovin S, Chi E Y, Jonas M. Science review: apoptosis in acute lung injury. Soluble Fas ligand induces epithelial cell apoptosis in humans with acute lung injury (ARDS) Crit Care. 2003;7:355–358. [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Liles W C, Frevert C W, Nakamura M, Ballman K, Vathanaprida C, Kiener P A, Martin T R. Recombinant human Fas ligand induces alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis and lung injury in rabbits. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L328–L335. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Winn R K, Martin T R, Liles W C. Sustained lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation in mice is attenuated by functional deficiency of the Fas/Fas ligand system. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:358–361. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.358-361.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H L, Akinci I O, Baker C M, Urich D, Bellmeyer A, Jain M, Chandel N S, Mutlu G M, Budinger G R. The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is required for lipopolysaccharide-induced lung endothelial cell death. J Immunol. 2007;179:1834–1841. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton K E, Plopper C G, Mercer R R, Roggli V L, Patra A L, Brody A R, Crapo J D. Airway branching patterns influence asbestos fiber location and the extent of tissue injury in the pulmonary parenchyma. Lab Invest. 1986;55:688–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churg A, Brauer M. Ambient atmospheric particles in the airways of human lungs. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2000;24:353–361. doi: 10.1080/019131200750060014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Usatyuk P V, Gorshkova I A, He D, Wang T, Moreno-Vinasco L, Geyh A S, Breysse P N, Samet J M, Spannhake E W, Garcia J G, Natarajan V. Regulation of COX-2 expression and IL-6 release by particulate matter in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:19–30. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0105OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge K M, Rutschman D H, Factor P, Katz A I, Bertorello A M, Sznajder J L. Differential expression of Na-K-ATPase isoforms in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1997;273:L246–L255. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]