Abstract

This paper describes the development of a unique prison participatory research project, in which incarcerated women formed a research team, the research activities and the lessons learned. The participatory action research project was conducted in the main short sentence minimum/medium security women's prison located in a Western Canadian province. An ethnographic multi-method approach was used for data collection and analysis. Quantitative data was collected by surveys and analysed using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data was collected from orientation package entries, audio recordings, and written archives of research team discussions, forums and debriefings, and presentations. These data and ethnographic observations were transcribed and analysed using iterative and interpretative qualitative methods and NVivo 7 software. Up to 15 women worked each day as prison research team members; a total of 190 women participated at some time in the project between November 2005 and August 2007. Incarcerated women peer researchers developed the research processes including opportunities for them to develop leadership and technical skills. Through these processes, including data collection and analysis, nine health goals emerged. Lessons learned from the research processes were confirmed by the common themes that emerged from thematic analysis of the research activity data. Incarceration provides a unique opportunity for engagement of women as expert partners alongside academic researchers and primary care workers in participatory research processes to improve their health.

Keywords: Health, incarceration, participatory, prison, research, women

Introduction

The majority of women with short prison sentences in Canada are imprisoned due to illegal activities stemming from drug and alcohol use (Jurgens, 1997/8; Anderson, Rosay, & Saum, 2002) Women in prison typically have poorer health, with a higher prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C, cervical dysplasia, and psychiatric illness than the general population.(Martin, Gold, Murphy, Remple, Berkowitz, & Money, 2005; Lewis, 2006; Mooney, Minor, Wells, Leukefeld, Oser, & Tindall, 2007) Many women in the provincial correctional system revolve in and out of prison with recidivism rates such as 70% in 2 years.(Corrections Branch Public Safety, 2004). Incarceration often fails to prepare women for (re)integration into society. Following release, many of these women remain marginalized by society with [0]chronic socio-economic health issues (Association AC, 1990; Brooke, Taylor, Gunn, & Maden, 1998; Browne, Miller, & Maguin, 1999).

Participatory health research offers a means to empower those who engage in the process (Macauly, Gibson, Freeman, Commanda, McCabe, Robbins, et al., 1999). The result is an improved self-esteem and facilitated voice, which collectively contribute to changed health behaviour and education, and improved long-term health outcomes (Romero, Lucero, Fredline, Keefe, & O'Connell, 2006; Tsey, Wilson, Haswell-Elkins, Whiteside, McCalman, Cadet-James, et al., 2007; Brown, Hernandez, Saint-Jean, Evans, Tafari, Brewster, et al., 2008). Similarly, empowerment models of health promotion seek to engage citizens in processes of increased self-determination and community empowerment (Frankish & Green, 1994). Prisons may be described as potential organic settings for health promotion (St Leger, 1997; Whitelaw, Baxendale, Bryce, MacHardy, Young, & Witney, 2001) because empowering prisoners to improve their own health also impacts the health of prison staff and prison inter-professional staff. The extent to which prisons adopt health promotion programs varies both within and between countries (UK Department of Health, 2002; Statistics Canada, 2006; WHO, 2008).

We found no reports of participatory research inside prison in which incarcerated individuals choose the health topics they wish to research. We found one published description of a prison in which the warden invited inmates to assist in the process of improving the education and health of all those inside prison (Bedi, 2006). The few published reports of prison participatory health research are limited to tightly defined health education topics that were predetermined by the academic research team (Paredes & Colomer Revueltab, 2001; Townsend, 2001).

We previously reported an initial study which described the feasibility of engaging women inside prison with participatory research, the health concerns of incarcerated women, prison staff, and academic researchers, and their suggested research interventions (Martin, Murphy, Chan, Ramsden, Granger-Brown, Macaulay, et al., in press). This paper describes the participatory research processes that centred around incarcerated women forming a research team, the research activities and the lessons learned.

Methods

The participatory action research project was conducted in the main short sentence (2 years or less) minimum/medium security women's prison located in a western Canadian province. At the time of the project, this facility housed up to 140 women in five cottage-style living units with an average stay of 3 months for provincially sentenced women. In addition, some women are remanded to custody while awaiting trial. Approximately 1600 women revolved through this provincial correctional centre each year, with a disproportionately high number of Aboriginal women (30% compared with 3.8% in the general Canadian female population; WHO, 2008). The participatory research project began following a face-to-face meeting that was held in October 2005 (Martin et al., in press). Incarcerated women were invited to form a research team following the face-to-face meeting. Participation on the research team continued to be inclusive of any woman who wanted to join and their activities continued to grow and shape as more women became involved as peer researchers1 on the team. The women of the prison research team began to collect self-data in an ethnographic manner in February 2006. This paper reports on project data collected from February 2006 until July 2007. Because participatory action research is a collaborative and progressive endeavour, the development of the activities and research processes are described as part of the results from this study.

Quantitative data collection and analysis

Quantitative data from demographic and ‘drug of choice’ surveys responses were entered into an Excel spreadsheet by incarcerated women peer researchers and a summer research assistant. Demographic information was collected on age, ethnicity, education, total time incarcerated, family disease history, drug of choice, and whether drug use lead to incarceration. The ‘drug of choice’ survey included questions such as, ‘What is your drug of choice?’, ‘What age did you start using?’, ‘Are you incarcerated due to drug use?’, and ‘What are some of your triggers inside and outside of jail?’ Quantitative data was analysed using descriptive statistics to provide frequencies and distributions.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Women of the prison research team collected observational data in order to record the research events as they evolved inside the prison. Qualitative data for this project included orientation package entries, which were written by incarcerated women who joined the research team; audio-taping of research team discussions, forums, and debriefings; archives of documents including attendance lists, written descriptions of the forums (face-to-face meetings), women's presentations, their proposals and letters. Forums and discussion groups were audio-recorded. Recordings were transcribed verbatim by trained incarcerated peer researchers, summer research students, and women released from prison who are engaged as community-based peer researchers. Personal identifiers were removed from the resulting transcriptions, which were then returned to participants, whenever possible, in order to verify accuracy. Transcripts of the qualitative data were analysed using standard iterative and interpretative qualitative methods; members of the academic research team and peer-researchers inside and outside of prison reviewed the transcripts and independently identified themes. Transcripts and field notes were reviewed in an iterative manner to ensure all emergent themes were captured. Representative quotes were selected from the transcripts to illustrate the main themes identified. Thematic analysis of transcripts was also conducted, by a research student, using NVivo, a qualitative software program that assisted in managing the data.

The findings were member-checked with the peer researchers. Three of these are coauthors: KM and DH were members of the prison research team; JM joined the project following release from prison. Based on the analysis, findings were compiled in an iterative manner, which resulted in the main lessons learned about the prison participatory research processes (Thorne, Kirkham, & MacDonald-Emes, 1997; Sandelowski, 1998).

Ethics

A Certificate of Approval was obtained from the local university Behavioral Research Ethics Board prior to proceeding with this research. All participants were provided with information about the research project and indicated their willingness to participate by signing the Consent Form. Everyone who worked with data signed a confidentiality agreement. Author REM, on behalf of the academic research team, signed a 5-year Research Agreement with the Assistant Deputy Minister, Ministry of Public Safety Solicitor General, Corrections Branch. REM also consulted and collaborated with the prison warden, management team and correctional staff about the implementation of the participatory research processes.

Results

Development of participatory research processes

Following an initial face-to-face prison meeting in October 2005, the incarcerated women who had assisted in writing the funding application asked the warden if ‘participatory health research team’ could become a prison work placement, because the work was so meaningful to them. The five shared values that had been expressed during the face-to-face meeting became guiding principles for the developing research processes (Martin et al., in press). From November 2005 to December 2006, all incarcerated women who wished to join the health research team were invited to become prison peer researchers. From January 2007 to August 2007, a programme officer screened and selected women who requested to work on the research team. Up to 15 women worked each day as members of the prison research team, with a total of 190 women (November 2005-August 2007). Incarcerated women peer researchers worked in collaboration with 10 academic research members from several universities, including University of British Columbia, University of Saskatchewan and McGill University.

Incarcerated women peer researchers developed an orientation package, which new members joining the research team were invited to complete. The orientation package was revised with minor iterations over several months as new women joined and shaped the group's processes. The final orientation package2 included:

a ‘welcome to the women's health research team’ work placement questionnaire including questions about a member's computer skills and skills they wish to acquire;

a ‘new member questionnaire’ including a demographic self-survey and health-related questions;

a ‘paragraph of passion’ exercise, which asked women to write a response to ‘what area do you want to learn more about in order to improve your health and the health of others?’;

a drug of choice paragraph and survey, which asked peer researchers to describe their illicit drug use;

an optional life story exercise in which women were invited to write about meaningful life events;

a peer researcher confidentiality agreement and consent form.

The prison peer research team developed a daily routine for themselves that included ‘angel words’ (each person in turn randomly selected an angel card3 from a closed bag and shared with the group what the word meant to them that day) and a reading from a spiritual reflection book. These routines often led to discussions, related to their spiritual and emotional healing, which fostered an atmosphere of peer support within the research team. In addition, the prison peer research team developed organizational processes that provided opportunities for them to develop leadership within the group (e.g. administrative and organizational skills, public speaking, liaising with correctional staff, and peer mentoring in computer, language, and writing skills).

Research activity findings

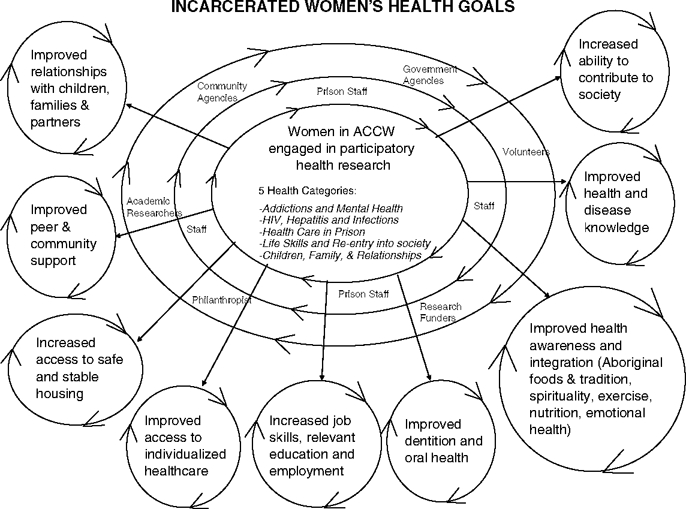

Through these processes, nine health goals emerged. These health goals grew out of the five health concerns (categories) that had been identified during the exploratory phase of the project (Martin et al., in press). The prison peer researchers, in collaboration with author REM, conceptualized their nine health goals as a diagram, which they posted on the wall of the prison dining room in order to seek verbal and written feedback from the broader prison community. Feedback was incorporated into a finalized, ‘Bubble Diagram’ (see Figure 1). The nine health goals reflect the incarcerated women's desire for health not only inside prison, but also in the community after their release from prison. The arrows around the edge of each bubble represent iterative cyclical processes necessary for planning, conducting and evaluation of interventions to attain each health goal.

Figure 1.

‘The bubble diagram’ describing the nine health goals as they emerged from 5 health categories.

One-hundred-and-two incarcerated women from the prison research team completed the demographic survey and the results are shown in Table 1. The demographics show that 61% were aged 30 or older and 31% were Aboriginal. The strong representation of Aboriginal women in the prison research team influenced the peer research team processes, so that they included Aboriginal methods of dialogue and models of holistic health and healing. For example, the peer research team often discussed topics in a talking circle, practicing a circular and equitable method of discussion. An object that represented a talking stick was often passed around the circle, inviting everyone in turn to add their voice to the discussion without interruption. In addition, the four quadrants of the medicine wheel (physical, emotional, mental and spiritual health) were explored by the research team members, highlighting their holistic approach to health.

Table 1.

Demographic self-survey and drug of choice survey of incarcerated women who joined the prison participatory health research team between February 2006-July 2007 (n = 102).

| Factor | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–29 | 39 | 39 |

| 30–39 | 40 | 40 |

| 40 + | 21 | 21 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 62 | 61 |

| Aboriginal | 31 | 31 |

| Asian | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 5 | 5 |

| Education (grade) | ||

| <10 | 17 | 17 |

| 11 | 37 | 37 |

| ≥12 | 46 | 46 |

| Total time incarcerated (years) | ||

| <1 year | 50 | 51 |

| 1–2 years | 12 | 12 |

| >2 years | 37 | 37 |

| *Family history of disease | ||

| Cancer | 58 | 58 |

| Diabetes | 39 | 39 |

| **Drug(s) of choice (n = 107) | ||

| Cocaine/crack | 57 | 56 |

| Heroin | 35 | 34 |

| Crystal meth | 17 | 17 |

| Marijuana | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 9 | 9 |

| No drug addiction | 10 | 10 |

| Reported that drug use led to incarceration (n = 107) Yes | 74 | 73 |

Missing values: Age = 2, Ethnicity = 1, Education = 2, Total time incarcerated = 3, Family history of disease = 2. *Not mutually exclusive, **Denominator is total number of women who use the drug.

In addition, 117 incarcerated women completed the ‘drug of choice’ survey and the results are also shown in Table 1. Seventy-nine women (74%) reported that drug use led to their incarceration. Of the 57 women who reported past use of cocaine/crack, 51 women (89%) reported that this use led to their incarceration; of the 35 women who reported past use of heroin, 33 (94%) reported that this use led to their incarceration; of the 17 women who reported past use of crystal meth, 13 (76%) reported that this use led to their incarceration. Nine women reported that ‘other’ drugs had been their drug of choice, including prescription drugs, morphine, opiates (oxycontin, etc.), tobacco, and gamma hydroxybutyric acid (GHB, the date rape drug). Thirteen women (12%) did not list heroin, cocaine/crack or crystal meth as drug of choice; of these women, 4/13 stated that the misuse of alcohol led to their incarceration.

Table 2 provides a summary of prison health and education activities (grouped according to health goal) that incarcerated women peer researchers and prison staff engaged in. For a full account, please see the project webpage.4 Activities included:

Table 2.

Activities of the prison participatory research team (November 2005-July 2007).

| Health goal identified by the prison participatory research processes | Education presentations§ created and given by incarcerated women peer researchers (number) | Surveys§ designed by incarcerated women peer researchers | Interventions created by incarcerated women peer researchers | Initiatives introduced by prison warden and/or prison staff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved health and disease knowledge | Addictions (10) Mental health (6) Diseases of interest (6) | Smoking Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Shop lifting | Created smoking cessation aids and resources for peers Proposal to create health self-learning modules | Prison staff retrieved Internet health education for incarcerated women peer researchers |

| Improved awareness and integration of health | Aboriginal culture (8) Spirituality and therapy (6) Physical health (5) | Sleep issues Health status and resources Physical fitness Gathered health info for Webpage§ | Wrote proposals to the warden for healthy food on canteen and sunglasses for outside work Developed and implemented a 6-week pilot nutrition and exercise programme Wrote letters to assist women upon release (requesting 1-year pass for community centres and library cards) Running group Purchase of cardio gym equipment Horticulture programme, to learn to grow food | Yoga classes Herbal teas to improve sleep Oatmeal on units as a healthy snack |

| Increased access to stable and safe housing | Homelessness and housing (2) | Homelessness and housing | Designed a housing proposal for women upon release Wrote letters (newspapers, philanthropists, policy makers, funders) Collaborated in writing a housing funding application+ | Hosted a prison university-community forum to brain-storm ideas about housing for incarcerated women |

| Improved dentition and oral health | Oral and dental care | Dental | Wrote letter (to university dentistry faculty) | Contacted dental hygienist school |

| Improved relationships with children, family and partners | Parenting skills (4) Interpersonal family relationships (6) | Prison mothers and their children Art therapy evaluation | Researched therapeutic options for healing of abuse and trauma Requested art therapy sessions | Parenting courses, and mothers and babies prison programme Collaborated with public health unit & resources¥ |

| Improved access to individualized health care | Requested meeting with prison health care staff to discuss concerns | Prison health care staff provided regular walk-about rounds of all living units, downloaded Internet health information for women ‘hygiene and hand washing’ tutorial and ‘health orientation’ for women upon arrival | ||

| Increased job skills, relevant education and employment | Employment readiness (4) Literacy (1) | Weekly skills acquisition Computer use | Mentored each other in computer skills Invited/hosted university researchers to facilitate research skill workshops Webpage§ design Gathered employment info. for Webpage§ | Aboriginal Studies# Collaborated with Employment Agency |

| Increased ability to contribute to society | Requested that ‘research team work’ become a prison work placement Hosted/organized prison health research forums Created Webpage§ Visited Gr 11 students Authored publications, presented at conferences, taught HIV course (see§) Gathered community volunteer info- Webpage§ | |||

| Improved peer and community support | Inter-personal support and mentoring among women of the research team Leaving prison transitions (2) Support inside prison (4) Peer support (2) | Appropriate behaviour Prison new research team member demographics Developed Webpage§ = resource upon release Gathered community resource info - Webpage§ | Inter-personal support and mentoring among women of the research team Invited Head of BC Parole Board to dialogues at prison research forum Proposal for clothing upon release |

§ For mote information, see Webpage created by incarcerated women = http://www.womenin2healing/org.

# Aboriginal Studies is a for credit course offered to all women in the prison. It is taught by co-author LLC of Nicola Valley Institute of Technology.

+ A local Employment Agency attended several prison health research forums and facilitated women to create their curriculum vitae and to find employment upon release.

¥ A local family resources centre facilitated parenting courses for women in prison+The director of a BC branch of the Elizabeth Fry society attended several prison health research forums and compiled women's voices and opinions into their funding application for supported female housing units.

education presentations created and given by incarcerated women peer researchers (including hosting prison health research forums with academic researchers, community agencies, funders, and policy makers; developing a library of PowerPoint health education presentations; visiting a local high school to inform and share their stories about the harms of drug and alcohol use);

surveys created and conducted by incarcerated women peer researchers;

interventions initiated by incarcerated women peer researchers (including hosting participatory qualitative analysis workshops, writing workshops, and research discussions with academic researchers);

creating a webpage to communicate project findings and community resource information for women leaving prison) and interventions initiated by prison staff.

Table 3 provides a summary of the lessons learned by academic researchers and prison peer researchers through the research processes. The lessons learned were confirmed (triangulated) by a thematic analysis of the qualitative data collected during the process of this participatory health research project; in this paper, commonly identified themes are reported.

Table 3.

Lessons learned from prison participatory research processes.

| What academic researchers learned | Women are the experts in their health and we should listen to them Women in prison have time on their hands and are keen to be part of the solution |

| Some prison staff or prison structures didn't buy into the participatory processes, but the research project was able to proceed based on common values | |

| Research project grew out of working relationships between warden, recreational therapist and prison physician | |

| We learned about participatory research from doing it, trusting the process and following the guiding principles (= shared values) | |

| Incarcerated women's view of health has a larger scope than ours Incarcerated women's health and education are interconnected The research processes changed our world view | |

| What incarcerated women peer researchers learned | We began to believe that change is possible The research project showed us a new way of living; it gave us a change of perspective and new hope |

| We learnt how to ask for, and to advocate for, things in prison that are healthy | |

| We learnt technical skills by doing (e.g. writing, computer programs) We began to communicate more effectively and confidently We developed a passion for our work and we had renewed purpose Our self-respect and self-esteem improved |

The research process provided a change of perspective and new hope for many of the incarcerated women involved in the project. They reported increased hope and confidence that they could initiate changes to improve their health:

Being a part of this research team has changed my perspective on life and what is more relevant. Because, [it's] given me a deeper sense of learning to accomplish something with my life … It was good. I learned a lot. It was a different experience to me, you know, something you don't expect happening in jail.

This theme of a change of perspective and hope was echoed in the observations from the prison staff:

I was really impressed with the way the girls put together such an informative program … maybe this research project has given them hope.

Prison staff also emphasized the importance of the development of skills for the women peer researchers:

I saw a side of the girls that was hidden before. It was so well put together that you didn't realize that you have these skills before.

The peer researchers asserted the development of skills as an important aspect of their growth within the research team:

And I'm just thrilled, the stimulation, the mind, the skills that I can use. I can just keep using the skills from the outside. So when I get back out there I'm still gonna be fresh, I'm still gonna be ready to go. I'm not losing, I'm not getting rusty, you know forgetting things … But I mean it's better than sitting around shoveling snow and learning nothing when you have the opportunity to learn what you are interested in.

Incarcerated women who were involved in this project reported encouragement from a newfound self-respect and self-esteem. As a result, they reported that they felt motivation to continue down the road to recovery:

I let go of all the expectations and I have learned to love myself regardless to what I have done … And I'm gonna do it. I'm gonna make it.

Another key theme that emerged from the women was the benefit of learning how to communicate effectively and confidently. The women on the research team learned to share their story and present it in an impacting way:

By presenting my life story, I've been reading it, rereading it and reading it aloud in research and everything and it got to the point where I felt that it was mundane and when I presented it, it felt like it was the first time I actually heard my own words and I looked up and saw those kids. They were listening, they were actually listening and hanging onto my every word and I felt that was great … I know my word had an effect. I honestly believed that so I am proud of it.

When I was talking to the students at the school I got children at that same age and I wished my son or daughter was in there to hear what I had to say because being a crack head or used-to-be-crack head for years, I didn't know how to approach my kids or how to talk to them about drugs and being a hypocritical person, but now with the dry run and seeing their expressions, they were in awe of all the information we were giving them … You said I just learned something now I know and it's going to be much easier to talk to my kids about drugs and everything.

By watching the process of the research project and the women that were involved, the prison staff observed the positive effects of allowing incarcerated women to be a part of something new and the theme of independence emerged. Prison staff reported that the independence the incarcerated women were given through this project contributed to the positive experience for most of the women involved.

I think they liked it because they had a lot of control over it as well; they take control of it themselves so it is not one of us standing up and teaching them a program and it is not us directing them how to do their workload … they are doing it on their own.

As a result of this project, the incarcerated women who became involved repeatedly expressed their passion for their work on the project and their sense of a renewed purpose:

…it's being busy like this and doing research and doing the typing and seeing everybody's story, reading everybody's story, it's just kind of made me feel like I'm not as depressed as I was here before. Because it has sparked such an interest in me and I feel like I'm useful and doing something to help us while we're here, but also to help the other women that come to the prison in the future. And it just makes me excited that we can actually look forward and hopefully this all does go through to help people, especially the women in prison.

The passion and purpose that the incarcerated women articulated was mirrored in the observations of the research academic team:

Because I see all of you engaged in doing something worth while and meaningful.

Discussion

For the academic research team, the biggest challenge was letting go of our preconceived notions of the focus for this health research project. As the academic researchers let go of a reductionist medical model of health, with its focus on research of diseases such as HIV, cancer, addiction, hepatitis C, they came to learn that the incarcerated woman's view of health and healing is larger and more complex. The health goals of women in prison are consistent with those described as the social determinants of health and determinants of health promotion. As we listened to the women's voices we learned the reality that their health goals are inter-related and inter-dependent, as well as consistent with Maslow's hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943) and an ecological model of health (Hancock, 1993). We came to appreciate that participatory research processes embrace interdisciplinary, intersectoral, and complexity theory principles, which underpin the work in this project (McCall, 2005).

A limitation of the project was that the work occurred in only one woman's prison in Canada and may not be applicable to other prison settings. However, we feel that these participatory health research processes and principles could apply to any prison and other institutional settings, although they are dependent upon the support of the warden and management staff. The challenges of the project included the lack of funding and high-turnover of women with short sentences. Therefore, it was not always possible to return transcripts to discussion participants to check accuracy. Continuity of research work was difficult after a woman's release from prison and continuity of focus within the research team was sometimes difficult to sustain. After we received funding, a summer research assistant (co-author GE), facilitated the continuity of focus and vision during the months of her tenure.

The strength of the project was its uniqueness: women in prison were engaged as equal partners in participatory health research to design and guide the aims and methods of the health research processes. The research activities of the women in the participatory health research team complemented those of the warden and prison staff, so that changes occurred in the prison setting that could transform the health and social well-being of women inside prison. In addition, this project illustrated the unique position of primary health care practitioners to initiate patient-centred health research projects.

Incarceration provides unique opportunities for engagement of women as expert partners in participatory research processes to improve their health. It also provides a unique opportunity for engagement of women's voices in health promotion and health research. However, in order for women's health goals to be attained, transformation must occur outside prison and also during the transitioning from prison to the outside, so that women can access support and resources upon their release. Future publications will discuss the details of the next steps in this prison participatory health research project as it moves towards attaining the nine health goals.

Acknowledgments

This health research project was supported by an operating grant from the BC Medical Services Foundation of the Vancouver Foundation. In addition, author Ruth Elwood Martin's time to facilitate writing this paper was supported through a BC Medical Services Foundation grant to the Community Based Clinical Investigator (CBCI) Salary Award Program at the University of British Columbia, Department of Family Practice; collaborative funding support was provided by Fraser Health Authority, Women's Health Research Institute and BC Women's Hospital. All authors declare that there are no potential, perceived, or real conflicts of interest for this paper, and declare independence from said funding organization.

The authors would like to thank Benjamin Martin, Anna Chan, and Megan Smith for, respectively, their research assistance work, qualitative analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Notes

Peer researcher: we define this as a woman who was/is incarcerated who was/is engaged in the participatory research project by learning and doing the following: (1) researcher activities, (2) peer support activities, and (3) self-development activities.

Orientation package: the complete orientation package is available at <www.womenin2healing.org>

‘Angel Words’ are a package of individual cards of descriptive words and nouns. A single descriptor or noun is found per card. (For example, ‘passion’ or ‘joy’).

References

- Anderson T.L., Rosay A.B., Saum C. The impact of drug use and crime involvement on health problems among female drug offenders. Prison Journal. 2002;82:50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Association AC. The female offender: What does the future hold? Washington DC: St. Mary's Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi K., editor. It's always possible. 2nd edn. Honesdale: Himalayan Institute Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke D., Taylor C., Gunn J., Maden A. Substance misusers remanded to prison-a treatment opportunity? Addiction. 1998;93:1851–1856. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9312185110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.R., Hernandez A., Saint-Jean G., Evans S., Tafari I., Brewster L.G., et al. A participatory action research pilot study of urban health disparities using rapid assessment response and evaluation. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:28–38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A., Miller B., Maguin E. Prevalence and severity of lifetime physical and sexual victimization among incarcerated women. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 1999;22:301–322. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(99)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrections Branch Public Safety. 2004. Female and male community risk needs assessment: Data from offenders assessed in 1998.

- Frankish C.J., Green L.W. Organizational and community change as the social scientific basis for disease prevention and health promotion. In: Albrecht G.L., editor. Advances in medical sociology. Greenwich: 1994. pp. 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock T. Health, human development and the community ecosystem: Three ecological models. Health Promotion International. 1993;8:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens R. 1997/8. Methadone, but no needle exchange pilot in federal prisons. Report No.: 3/4.

- Lewis C. Treating incarcerated women: Gender matters. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2006;29:773–789. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay A.C., Gibson N.J., Freeman W., Commanda L., McCabe M., Robbins C., et al. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. British Medical Journal. 1999;319((7212)):774–778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.E., Gold F., Murphy W., Remple V., Berkowitz J., Money D. Drug use and risk of bloodborne infections: A survey of female prisoners in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96((2)):97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF03403669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.E., Murphy K., Chan R., Ramsden V.R., Granger-Brown A., Macaulay A.C., et al. Participatory health research in a Canadian women's prison: How it all began. Global Health Promotion; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50:370–396. [Google Scholar]

- McCall L. The complexity of intersectionality. Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2005;30:1771–1800. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney J.L., Minor K.I., Wells J.B., Leukefeld C., Oser C.B., Tindall M.S. The relationship of stress, impulsivity, and beliefs to drug use severity in a sample of women prison inmates. International Journal of Offender Therapy Comp Criminol. 2007 doi: 10.1177/0306624X07309754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes I.C.J., Colomer Revueltab C. HIV/AIDS prevention in prison: Experience of participatory planning. Gac Sanit. 2001;15:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0213-9111(01)71516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L.W.N., Lucero J., Fredline H.G, Keefe J., O'Connell J. Woman to woman: Coming together for positive change - using empowerment and popular education to prevent HIV in women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18((5)):390–405. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Writing a good read: Strategies for re-presenting qualitative data. Research in Nursing Health. 1998;21:375–382. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199808)21:4<375::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2006. Census of population, Report No.: 97-558-XCB2006022. Statistics Canada.

- St Leger L. Editorial. health promoting settings: From Ottawa to Jakarta. Health Promotion International. 1997;12((2)):99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Kirkham S.R., MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing Health. 1997;20:169–177. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199704)20:2<169::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend D. Prisoners with HIV/AIDS: A participatory learning and action initiative in Malaysia. Tropical Doctor. 2001;31:8–10. doi: 10.1177/004947550103100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsey K., Wilson A., Haswell-Elkins M., Whiteside M., McCalman J., Cadet-James Y., et al. Empowerment-based research methods: A 10-year approach to enhancing indigenous social and emotional wellbeing. Australasian Psychiatry. 2007;15:S34–S38. doi: 10.1080/10398560701701163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UK Department of Health. Health promoting prisons: A shared approach. London: HMSO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw S., Baxendale A., Bryce C., MacHardy L., Young I., Witney E. Settings' based health promotion: A review. Health Promotion International. 2001;16:339–353. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2008 Health in Prisons Project. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/prisons (accessed 9 March 2009)