Abstract

Nevirapine (single dose), commonly used to prevent the mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in developing countries, frequently induces viral resistance. Even mutations which occur only in a minor population of the HIV quasispecies (<20%) are associated with subsequent treatment failure but cannot be detected by population-based sequencing. We developed sensitive allele-specific real-time PCR (ASPCR) assays for two key resistance mutations of nevirapine. The assays were specifically designed to analyze HIV-1 subtype A and D isolates accounting for the majority of HIV infections in Uganda. Assays were evaluated using DNA standards and clinical samples of Ugandan women having preventively taken single-dose nevirapine. Lower detection limits of drug-resistant HIV type 1 (HIV-1) variants carrying reverse transcriptase mutations were 0.019% (K103N [AAC]), 0.013% (K103N [AAT]), and 0.29% (Y181C [TGT]), respectively. Accuracy and precision were high, with coefficients of variation (the standard ratio divided by the mean) of 0.02 to 0.15 for intra-assay variability and those of 0.07 to 0.15 (K103N) and 0.28 to 0.52 (Y181C) for inter-assay variability. ASPCR assays enabled the additional identification of 12 (20%) minor drug-resistant HIV variants in the 20 clinical Ugandan samples (3 mutation analyses per patient; 60 analyses in total) which were not detectable by population-based sequencing. The individual patient cutoff derived from the clinical baseline sample was more appropriate than the standard-based cutoff from cloned DNA. The latter is a suitable alternative since the presence/absence of drug-resistant HIV-1 strains was concordantly identified in 92% (55/60) of the analyses. These assays are useful to monitor the emergence and persistence of drug-resistant HIV-1 variants in subjects infected with HIV-1 subtypes A and D.

Thirty-three million adults and children are living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) worldwide, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa (36). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV as well as antiretroviral long-term treatment (ART) are used to reduce the burden of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (7). The nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) nevirapine (NVP) is widely applied as an antiretroviral prophylaxis for the prevention of vertical transmission of HIV and as a backbone of ART in many developing countries (16, 35). However, the low genetic barrier of NVP leading to resistance by a single nucleotide mutation (25) predisposes for the emergence of drug-resistant HIV variants. Even a single dose of NVP is associated with the frequent selection of NVP/NNRTI-resistant HIV strains (2, 10-14, 18, 29). Accordingly, the response to an NVP-containing ART was shown to be compromised in women following single-dose prophylaxis with NVP (21, 23). Most drug-resistant HIV populations are present only at low levels which cannot be detected by standard population-based sequencing with a detection limit of ≥20%. However, minor drug-resistant variants can become the dominant population, thereby leading to treatment failure (4, 20, 22, 27, 34). Allele-specific real-time PCR (ASPCR) assays were shown to detect drug-resistant populations at levels of <1% (17) and have previously been developed for the detection of NNRTI-associated resistance mutations in the pol gene of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) subtypes B and C (6, 18-19, 24, 26, 28, 31, 33). ASPCR assays in general are highly susceptible to the impaired binding of primers due to polymorphisms in the primer-binding regions (30). Due to the high variability of HIV-1 sequences, subtype-generic ASPCR assays are hardly available. So far, no ASPCR assay has been established for the analysis of the most frequent NVP-associated drug-resistant mutations in HIV-1 subtype A and D strains. These subtypes are common in East African and Central African countries and account for more than 95% of all Ugandan HIV infections (15, 32).

We developed and evaluated highly sensitive ASPCR assays enabling the detection and quantification of the two most common NVP-associated resistance mutations, K103N and Y181C, in the pol open reading frame of subtypes A and D. In addition, we tested the blood specimens of 20 HIV-infected pregnant Ugandan women who had preventively been treated with single-dose NVP to evaluate the ASPCR assays by using clinical samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of standards.

The detection limit of HIV RNA in plasma samples was determined by using serial dilutions of HIV-negative human plasma spiked with a defined amount of HIV-1 NL4.3 virus (1).

To quantify drug-resistant HIV-1 variants carrying the Y181C mutation in the reverse transcriptase (RT), DNA standards were generated by cloning amplified pol fragments (nucleotides [nt] 2001 to 3454 of HXB2; accession no. K03455) (37) from patients with mutant and wild-type RT into the plasmid pBluescript II SK(+) (pBSSK+, pBlueskript; Stratagene GMBH, Heidelberg, Germany). K103N DNA standard mixtures were obtained by assembling clonal plasmid DNA carrying either the mutant codon AAC or AAT at position 103 of the RT with pNL4.3 carrying the wild-type sequence (AAA). Standard curves were established with defined ratios of wild type (pNL4.3) and mutant plasmid controls (0%, 0.01%, 0.1%, 1%, 10%, and 100% of the proportion of mutant variants) to quantify the amount of drug-resistant variants. The total amount of input DNA was the same for all standard mixtures used (107 copies/ml). All standards were handled the same way as the samples of patients and thus were also subjected to the outer PCR analysis.

Clinical samples.

Two samples each were collected from 20 Ugandan women who had participated in a PMTCT of HIV program in western Uganda; ethical approval by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology was granted. The drug-naïve women ingested a single dose of 200 mg of NVP, and none of the women received ART during the observation period. The first blood sample was collected directly after the intake of NVP and was thus supposed to contain only wild-type HIV-1 (5). The second blood sample was taken 1 to 6 weeks after the NVP intake.

Primers.

Primers (Table 1) were designed to be subtype A and D specific using the reference alignment of the Ugandan HIV-1 M group sequences accessible via the Los Alamos HIV sequence database available at http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/components/hiv-db/combined_search_s_tree/search.html. The primer-binding sites of the standards including the wild-type control HIV-1 NL4.3 virus (subtype B) (1) were 100% complementary to the primers used in the outer RT-PCR and the inner ASPCR assays.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences of outer RT-PCR analysis, ASPCR assays, and allele-specific PCR primers

| Assay and primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Nucleotide position (HXB2) |

|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | ||

| OUT FOR1 | AAACAATGGCCRTTGACAGAAGA | 2613-2635 |

| OUT REV1 | GGATGGAGTTCATAHCCCATCCA | 3234-3256 |

| K103N ASPCR | ||

| Forward primer FOR2 | GGCCTGAAAATCCATAYAATACTCC | 2701-2725 |

| Generic DNA reverse primer REV4 | CCCACATCYAGTACTGTTACTGATTT | 2859-2884 |

| AAC-specific reverse primer REV6 | CCCACATCYAGTACTGTTACTGATTGG | 2858-2884 |

| AAT-specific reverse primer REV7 | CCCACATCYAGTACTGTTACTGATTCA | 2858-2884 |

| Y181C ASPCR | ||

| Forward primer FOR3 | AAATCAGTAACAGTACTRGATGTGGG | 2859-2884 |

| Generic DNA reverse primer REV9 | ATCCTACATACAARTCATCCATGTATTGA | 3092-3120 |

| TGT-specific reverse primer REV11 | ATCCTACATACAARTCATCCATGTATTGCC | 3091-3120 |

The mutant-specific primers exhibited an additional mismatch on the penultimate (second to the terminal) base of the antisense primer to diminish unspecific priming and to increase the specificity for the target mutation (8).

RT-PCR and outer real-time PCR.

Virus was pelleted from 450 μl of plasma by centrifugation for 90 min at 14,000 rpm and 4°C. RNA was extracted using the QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and eluted in 60 μl of buffer provided with the kit. Aliquots of 10 μl were stored at −70°C.

A total of 9 μl of RNA (68-μl plasma equivalents) was reverse transcribed; after denaturation of the RNA at 65°C for 5 min, the RT mix with 100 U SuperScript II RT, 1× RT buffer, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 500 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (all reagents from Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), 40 U RNasin (Promega, Mannheim, Germany), and 60 μM of random hexamers (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was added to a final volume of 20 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated for 1 h at 42°C and stopped by heating for 5 min at 95°C.

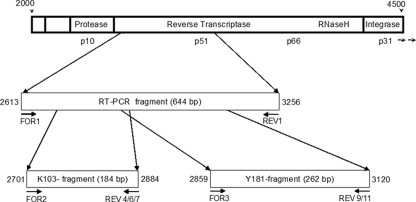

The outer real-time PCR was performed with the LightCycler 480 system and the 480 SYBR green I master kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The PCR amplifies a 644-bp pol fragment comprising codons 103 and 181 of the RT (nt 2613 to 3256 on HXB2; accession no. K03455) (Fig. 1). The 20-μl reaction mixture contained 4 μl of cDNA and 0.6 μM each of forward primer OUT FOR1 and reverse primer OUT REV1 (Table 1). PCR amplifications were started with a 10-min denaturation step at 94°C, followed by 50 amplification cycles (15 s at 94°C, 20 s at 62°C, and 1 min at 72°C) and a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. Melting point analysis of the PCR products from 60°C to 95°C was carried out to ensure the specificity of the amplified products, and only those samples melting at the expected temperature of 78°C were further analyzed by ASPCR.

FIG. 1.

HIV-1 pol gene and amplified PCR fragments of RT-PCR and ASPCR assays. Nucleotide positions correspond to the nucleotide sequence of HXB2; accession no. K03455.

Quantification of mutant populations by using ASPCR.

The outer RT-PCR was diluted 1:1,000 in 5 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8. Approximately 108 to 109 copies/reaction (quantitated by real-time PCR using the outer PCR) were used as the cDNA input for the ASPCR. For detection and quantification of mutant populations, two separate ASPCR reactions per mutation were performed, one to quantify generically all viral molecules and one to quantify specifically the mutant molecules only.

The K103N assay was composed of three separate reactions per sample, resulting in a 184-bp fragment (nt 2701 to 2884 on HXB2; accession no. K03455) (Fig. 1). The forward primer FOR2 (Table 1) was combined either with the reverse primer REV4 (amplification of the wild-type and mutant sequences), REV6 (mutant-specific sequence AAC), or REV7 (mutant-specific sequence AAT). The forward primer FOR3 (Table 1) was combined with the generic reverse primer REV9 to amplify all viral copies or with the mutant-specific primer REV11 (262-bp fragment; nt 2859 to 3120 on HXB2; accession no. K03455) (Fig. 1) to detect the Y181C mutant (codon TGT).

Generic and mutant-specific amplifications were performed in parallel under identical conditions: 2 μl of the outer PCR product (diluted 1:1,000) and primers (each at 0.5 mM), using the 480 SYBR green I master kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions in a 20-μl final volume. All ASPCR reactions were started with an initial denaturation step (95°C for 5 min). The ASPCR for K103N was followed by 45 cycles (95°C for 10 s, 62°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 10 s). For the Y181C ASPCR, 45 amplification cycles at 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 10 s were performed. Amplification specificities of PCR products were checked by thermal denaturation analysis. All ASPCR assays were run in duplicate, and the arithmetic mean was used for further analysis. Each run was performed with a complete set of mutant and wild-type DNA controls (see “Construction of standards”).

Establishment of cutoff for the detection of mutant variants.

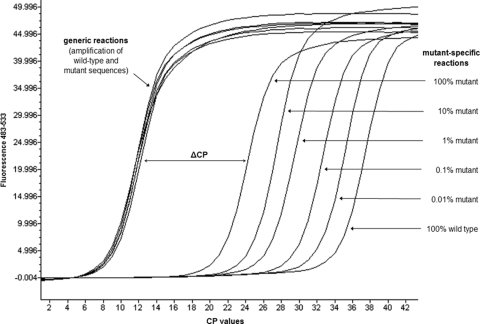

The threshold cycle/crossing point (CP) of real-time PCR analysis indicates the cycle number at which the fluorescence emission exceeds the background fluorescence. In the generic reaction, all viral templates were amplified. Therefore, the CP of the generic reaction is always the same, regardless of the presence of mutant template (Fig. 2). However, the higher the amount of mutant template in a given sample, the lower the CP of the mutant-specific reaction (Fig. 2). Thus, the higher the proportion of a mutant population in a given sample, the lower the difference between the CP of the mutant-specific reaction and that of the generic reaction (ΔCP) (Fig. 2). The cutoff indicating the presence of mutant populations was defined as the mean ΔCP (eight independent runs) of the 100% wild-type control minus three standard deviations (SD). For each sample, the ΔCP was calculated, and any ΔCP below the cutoff indicated the presence of a mutant population. The term “standard-related cutoff” is used throughout the text if this definition was applied.

FIG. 2.

Example of amplification curves of cloned DNA standards with different frequencies of mutant alleles in the real-time ASPCR assay.

An additional cutoff calculation was used for the clinical samples of Ugandan women. Since the baseline samples were obtained from women within a few hours after the intake of NVP prophylaxis, these samples were supposed to contain wild-type HIV-1 variants only. This assumption is reasonable as K103N-containing minor HIV variants were found in only 2% of drug-naïve Ugandan women (5). Therefore, we used the mean ΔCP (minus 3 SD) of the baseline sample of each woman as an individual cutoff. Furthermore, the presence of a mutant HIV-1 population was considered only if the ΔCP value of the follow-up sample was at least two cycles lower than the ΔCP value of the baseline sample. For this definition, the term “patient-specific cutoff” is used throughout the text.

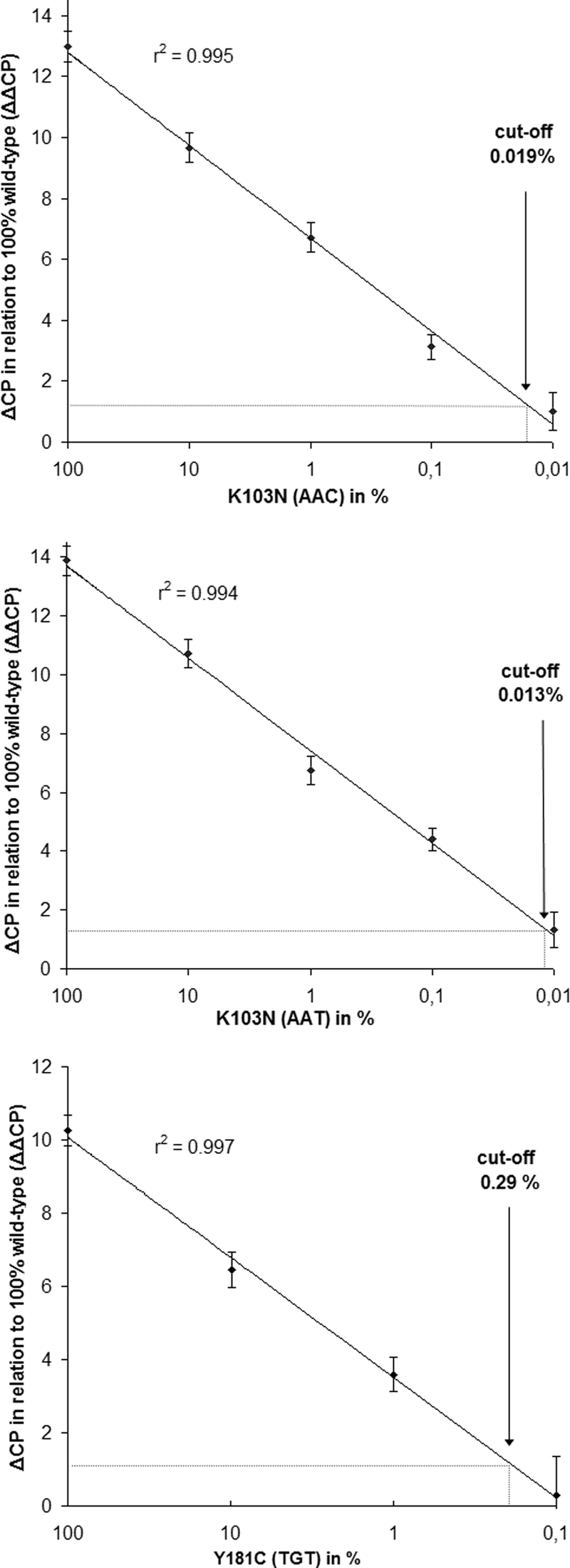

Quantification of mutant variants.

Standard curves were calculated by the defined mixtures of wild-type and mutant DNA controls. The ΔCP of mutant DNA controls was compared to the ΔCP of the 100% wild-type DNA control (ΔΔCP equals the ΔCP of 100% wild type minus the ΔCP of the sample). A standard curve of the ΔΔCP values of the defined mixtures of wild-type and mutant DNA controls was established for each of the three mutations (K103N [AAC], K103N [AAT], Y181C [TGT]) and was used to quantify the proportions of mutant HIV-1 populations in samples from the mothers treated with NVP.

Evaluation of the precision of the ASPCR.

The precision and accuracy of the assays were evaluated by testing the DNA controls with a nominal proportion of mutant allele ranging from 0.01% to 100% four times in the same run (intra-assay variability) and in eight independently performed runs (interassay variability). The SD and coefficient of variation (the SD divided by the mean) as a relative measure of data dispersion were calculated to determine precision and variability. Accuracy was evaluated by comparing the nominal input of the mutant allele with the calculated amount.

Population-based sequencing.

Population-based sequencing was performed using the Viroseq HIV-1 genotyping system version 2.0 (Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) and the 3130xl Genetic Analyzer automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany).

Determination of HIV-1 subtypes.

HIV-1 subtyping of the pol sequence was performed using the Rega subtyping tool, which determines the HIV-1 subtype of a query sequence using phylogenetic analysis and bootscanning methods (http://dbpartners.stanford.edu/RegaSubtyping/) (9). Only subtype classification based on bootstrap values of >70% in the tree topology were taken into account.

RESULTS

RT-PCR.

The minimum input of HIV RNA required to amplify reproducibly was 1,000 copies per RT-PCR. All 20 clinical samples were successfully amplified and quantified in the outer RT-PCR (median viral load, 12,935 copies/ml; interquartile range, 5,219 to 49,287 copies/ml; range, 1,700 to 1,000,000 copies/ml).

Cutoff for the detection of mutant HIV variants using cloned DNA standards.

The standard curves calculated by the ΔΔCP values of the DNA plasmid control mixtures with different mutant allele frequencies are shown in Fig. 3. The lower limit of detection of minor drug-resistant variants was 0.019% for K103N (AAC), 0.013% for K103N (AAT), and 0.29% for Y181C. The 100% HIV wild-type controls were correctly identified in all runs (100% specificity). The sensitivity for 0.1% to 100% mutant controls (K103N) and 1% to 100% mutant controls (Y181C) was 100%. The ΔΔCP values were highly correlated (r > 0.99) to the proportion of mutant DNA (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Sensitivity of the K103N (AAC), K103N (AAT), and the Y181C (TGT) ASPCR assays. Data points represent the mean of eight independent experiments, and error bars indicate the SD.

Precision and accuracy of the ASPCR using cloned DNA standards.

Intra-assay and interassay variability is shown in Table 2. The coefficients of variation (CVs) of intra-assay variability were 0.02 to 0.15 for all samples with proportions of mutant DNA ranging from 0.1 to 100%. The CVs of inter-assay variability for samples with proportions of mutant DNA ranging from 0.1 to 100% were 0.07 to 0.15 (codon 103) and 0.28 to 0.52 (codon 181). The lower the input of mutant DNA, the higher the CV, and controls harboring 0.01% mutant allele resulted in interassay CVs of 0.3 to 0.74.

TABLE 2.

Intra-assay and interassay variability of ASPCR assays to detect NVP-resistant HIV-1 variantsa

| % Nominal mutant allele | Intra-assay variability (mean % mutant allele ± SD)

|

Interassay variability (mean % mutant allele ± SD)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAC (K103N) | AAT (K103N) | TGT (Y181C) | AAC (K103N) | AAT (K103N) | TGT (Y181C) | |

| 100 | 118.6 ± 2.4 | 97.6 ± 4.8 | 100.2 ± 6.6 | 116.4 ± 12.8 | 114.0 ± 14.4 | 135.5 ± 37.5 |

| 10 | 10.3 ± 0.41 | 11.1 ± 0.94 | 7.5 ± 0.48 | 9.4 ± 0.81 | 11.4 ± 1.28 | 9.7 ± 3.11 |

| 1 | 1.09 ± 0.05 | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.11 | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 0.62 ± 0.07 | 1.23 ± 0.37 |

| 0.1 | 0.097 ± 0.01 | 0.076 ± 0.01 | 0.135 ± 0.02 | 0.068 ± 0.01 | 0.105 ± 0.02 | 0.182 ± 0.09 |

| 0.01 | 0.019 ± 0.005 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.091 ± 0.011 | 0.014 ± 0.004 | 0.013 ± 0.009 | 0.131 ± 0.053 |

| 0 | 0.009 ± 0.003 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.059 ± 0.003 | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 0.091 ± 0.035 |

Means were calculated from four replicates measured in one run (intra-assay variability) and from eight independent experiments (interassay variability).

All calculated values for mutant populations represented 50% to 180% of the nominal input in the range of 0.1% to 100% mutant frequency.

Analysis of clinical samples.

The first sample of the 20 Ugandan women was taken within a few hours (median, 6 h; interquartile range, 4 to 8 h; range, 2 to 25 h) after the intake of 200 mg NVP. All but one (subtype K) of the HIV subtypes were subtype A1 (n = 10), D (n = 7), or A1D (n = 2) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Results of ASPCR assays of baseline samples of 20 HIV-infected Ugandan womena

| Patient no. | Subtype | % K103N (AAC) | % K103N (AAT) | % Y181C (TGT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A1 | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 2 | A1 | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 3 | D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 4 | A1 | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 5 | D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 6 | A1/D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 7 | A1 | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 8 | D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 9 | A1/D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 10 | A1 | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 11 | A1 | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 12 | D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 13 | A1 | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 14 | D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 15 | D | No mut | No mut | No mut |

| 16 | A1 | 0.3 | 6.2 | No mut |

| 17 | A1 | 1.6 | 1.1 | No mut |

| 18 | K | No mut | No mut | 1.2 |

| 19 | A1 | No mut | No mut | 0.6 |

| 20 | D | No mut | No mut | 0.3 |

No mut, no drug-resistant HIV-1 population detected.

Eighteen samples (90%) in the AAC-K103N assay, 18 samples (90%) in the AAT-K103N assay, and 17 samples (85%) in the Y181C assay were identified to contain 100% wild-type virus (Table 3). For these samples, the median CP value of the generic reactions was 9 (range, 7 to 11). Seven drug-resistant HIV populations were identified in clinical samples of five women (patient no. 16 to 20) (Table 3). K103 mutants with 0.3% AAC plus 6.2% AAT and 1.6% AAC plus 1.1% AAT mutant frequencies and Y181C mutants with frequencies of 0.3%, 0.6%, and 1.2%, respectively, were detected. In three of these five women, an additional single nucleotide polymorphism close to the 3′ end of the reverse primer-binding site (patient no. 16, 17, and 18) (Table 3) was identified in the RT sequence. The CP values of the generic reaction were high for these three samples (17-20). No primer mismatch was revealed in the two other samples carrying the HIV Y181C mutation at a frequency of 0.6% and 0.3% (patient no. 19 and 20) (Table 3). Based on population-based sequencing in all samples, only wild-type sequences at both codons 103 and 181 of the RT could be identified.

The follow-up samples were collected 1 to 6 weeks after the intake of NVP single-dose prophylaxis. The 60 ASPCR results of the 20 samples (three mutation analyses per sample) applying the patient-specific cutoff and the standard-related cutoff as well as the results of population-based sequencing were compared (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Results of the ASPCR assays and the population-based sequencing of plasma samples collected from 20 HIV-infected Ugandan women 1 to 6 weeks after the intake of single-dose NVPa

| Group | K103N (AAC)

|

K103N (AAT)

|

Y181C (TGT)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | ASPCR assay result

|

Population-based sequencing result | Patient no. | ASPCR assay result

|

Population-based sequencing result | Patient no. | ASPCR assay result

|

Population-based sequencing result | ||||

| Patient-specific cutoff | Standard-related cutoff | Patient-specific cutoff | Standard-related cutoff | Patient-specific cutoff | Standard-related cutoff | |||||||

| A | 1 | wt | wt | wt | 1 | wt | wt | wt | 1 | wt | wt | wt |

| 3 | wt | wt | wt | 3 | wt | wt | wt | 3 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 4 | wt | wt | wt | 4 | wt | wt | wt | 4 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 6 | wt | wt | wt | 6 | wt | wt | wt | 6 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 8 | wt | wt | wt | 7 | wt | wt | wt | 8 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 10 | wt | wt | wt | 8 | wt | wt | wt | 10 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 11 | wt | wt | wt | 10 | wt | wt | wt | 12 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 12 | wt | wt | wt | 11 | wt | wt | wt | 13 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 13 | wt | wt | wt | 12 | wt | wt | wt | 15 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 15 | wt | wt | wt | 15 | wt | wt | wt | 16 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 19 | wt | wt | wt | 16 | wt | wt | wt | 17 | wt | wt | wt | |

| 19 | wt | wt | wt | 20 | wt | wt | wt | |||||

| B | 2 | Mixture (28) | Mixture (20) | Mixture | 9 | Mixture (35) | Mixture (15) | Mixture | 5 | Mixture (11) | Mixture (38) | Mixture |

| 7 | Mixture (21) | Mixture (6.2) | Mixture | 9 | Mut (>100) | Mixture (25) | Mixture | |||||

| 9 | Mixture (26) | Mixture (5.9) | Mixture | 14 | Mixture (30) | Mixture (1.3) | Mixture | |||||

| 14 | Mixture (44) | Mixture (60) | Mixture | |||||||||

| C | 5 | Mixture (11) | Mixture (4.1) | wt | 2 | Mixture (1.9) | Mixture (2.2) | wt | 2 | Mixture (15) | Mixture (9.5) | wt |

| 16 | Mixture (0.05) | Mixture (2.4) | wt | 5 | Mixture (13) | Mixture (3.3) | wt | 18 | Mixture (1.1) | Mixture (15) | wt | |

| 17 | Mixture (3.3) | Mut (>100) | wt | 13 | Mixture (0.03) | Mixture (0.03) | wt | |||||

| 18 | Mixture (1.6) | Mixture (0.9) | wt | 18 | Mixture (0.6) | Mixture (0.4) | wt | |||||

| 20 | Mixture (0.2) | Mixture (0.06) | wt | 20 | Mixture (0.3) | Mixture (0.03) | wt | |||||

| D | 14 | wt | Mixture (0.04) | wt | 7 | Mixture (0.4) | wt | wt | ||||

| 17 | wt | Mixture (0.9) | wt | 11 | Mixture (1.1) | wt | wt | |||||

| 19 | wt | Mixture (0.4) | wt | |||||||||

For ASPCR assays, the results for both cutoff methods (patient-specific and standard-related) are shown and quantifiable drug-resistant HIV populations are indicated in percentages. According to the results of the ASPCR assays and the population-based sequencing four groups were defined as follows: A, concordant detection of wild-type HIV by all assays; B, concordant detection of mutant populations by all assays; C, detection of mutant populations by ASPCR assays with both cutoff methods but not by population-based sequencing; and D, divergent results of the ASPCR assays between the two cutoff methods. wt, detection of wild-type HIV only; Mut, detection of mutant HIV only; Mixture, detection of wild-type and mutant HIV (percent mutant HIV).

Whenever both the patient-specific cutoff method and the standard-related cutoff method of the ASPCR assays indicated 100% wild-type HIV-1, the population-based sequencing concordantly showed only wild-type virus (n = 35; group A) (Table 4).

The presence of the K103N or Y181C mutation as identified by population-based sequencing was always confirmed in the ASPCR assays (n = 8; group B) (Table 4).

Both cutoffs, the standard-related cutoff as well as the patient-specific cutoff of the ASPCR assays, provided evidence for the presence of low-level minority mutations in 20% of the analyses (n = 12) which were not detectable by population-based sequencing (group C) (Table 4).

In 5 out of the 60 (8.3%) analyses, the qualitative results differed depending on the patient-specific and standard-related cutoff applied (group D) (Table 4). All drug-resistant variants were present at levels ≤1.1% in these five patients; population-based sequencing detected wild-type HIV only and a mismatch in each of the primer-binding sites of the reverse primer in all five patients.

Quantification results of standard-related and patient-specific cutoff differed more than 10-fold in four samples. In one sample, application of the standard-related cutoff yielded a much lower proportion of the HIV variant with the Y181C mutation (1.3% versus 30%; patient no. 14; group B) (Table 4), while population sequencing detected the mutant variant in the presence of the wild type. In contrast, the standard-related cutoff method resulted in much higher proportions of mutant populations in three samples (patient no. 16, K103N [AAC], 2.4% versus 0.05%; patient no. 17, K103N [AAC], >100% versus 3.3% K103N; and patient no. 18, Y181C, 15% versus 1.1%) which were all identified as 100% wild-type HIV-1 by population-based sequencing. Polymorphisms in the primer-binding region of the reverse primer were detected in the HIV genome of the four patients; three out of the four samples exhibited extremely high CP values (14-20) in the generic reactions.

DISCUSSION

Due to its low genetic barrier, NVP selects rapidly for resistance. Minor drug-resistant variants are of special interest since they may pave the way for treatment failure (4, 20, 22, 27, 34). Here, three ASPCR assays to detect minor HIV-1 variants exhibiting K103N and Y181C resistance mutations in subtype A and D isolates were successfully developed and evaluated.

Performance of ASPCR assays using cloned DNA standards.

K103N and Y181C variants were detected at very low levels as follows: 0.019% (K103N [AAC]), 0.013% (K103N [AAT]), and 0.29% (Y181C). For K103N, the precision achieved was high with low mean interassay CVs (<0.15) across a broad range of 0.1% to 100% mutant frequency. Mean interassay CVs were higher (>0.28) for the Y181C mutation, thus not matching the typical criteria for quantitative assays. In this context, it is important to note that the main aim of resistance testing is the qualitative assessment of drug-resistant variants. As for the determination of HIV viral load, we suggest that a true increase/decrease of drug-resistant variants should be considered only at a change of at least 0.5 to 1 log. The accuracy of the three ASPCR assays was high. The assays overestimated slightly the actual proportion at very high frequencies of mutant alleles (100%).

Application to clinical samples.

Potential polymorphisms in primer-binding sites of clinical samples compared to cloned DNA standards with primer-binding sites that are 100% complementary to the primer sequence necessitate the evaluation of clinical samples. We therefore analyzed clinical samples of 20 women who participated in a PMTCT program in Uganda.

The first blood samples were taken within a few hours after the intake of single-dose NVP from previously antiretroviral drug-naïve women. As expected, most samples harbored wild-type HIV only (Table 3), while minor drug-resistant HIV populations (0.3% to 6.2%) were identified in 7/60 (12%) analyses and in 5/20 (25%) women, respectively. Population-based sequencing revealed no NVP-associated mutations but an additional polymorphism within the last four nucleotides of the reverse primer-binding site in the ASPCR assay in three of these five women although not in two of the women (Y181C, 0.3% and 0.6%). This mismatch on the 3′ end of the primer-binding site had much more of an impact on the binding specificity of the generic primer compared to that of the mutant-specific primer (designed with a mismatch already at the penultimate position). Therefore, the presence of natural polymorphisms resulted in a much higher CP of the generic primer. Consequently, the difference between the CP values of generic and mutant-specific primers (ΔCP) became lower, thus simulating the presence of mutant populations. However, this misinterpretation can simply be avoided by checking the CP values of the different PCRs; if the CP value using the generic primer is much higher than usual but the CP value with the mutant-specific primer is within the usual range, there is much evidence for the presence of polymorphisms. We therefore assume that at least the three of the five analyses exhibiting high CP values in the generic reaction most likely represent false positive results. However, it cannot be excluded that low-level mutant populations were indeed present in these samples from drug-naïve mothers. Primary drug resistance mutations in the HIV genome were shown to occur in some Ugandan women without any previous drug intake (5).

Altogether, these results reflect the higher variability of clinical samples compared to cloned DNA standards. To overcome this problem and to avoid false positive results, the increase of the cutoff for detection of the mutant population up to 1% could be a rational alternative for the analysis of clinical samples. In addition, samples exhibiting an abnormally high CP value in the ASPCR with the generic primer should be excluded from analysis since they cannot be reliably analyzed.

The 60 ASPCR results from follow-up samples matched strongly with the results obtained by population-based sequencing (Table 4). However, the ASPCR assays were able to detect low-level drug-resistant HIV populations in 20% of the analyses. The quantification results of these additionally detected drug-resistant variants were 0.03% to 15% (patient-specific cutoff) and thus below the detection limit of the population-based sequencing.

To compensate for individual sequence variability in the primer-binding site, it is advantageous to have an individual reference sample prior to the intake of antiretroviral drugs. This baseline sample can be used for the determination of a patient-specific cutoff. However, most often such a sample is not available. In this case, a standard cutoff derived from cloned DNA standards has to be applied to all patient samples. To investigate the usefulness of a standard cutoff, we compared the qualitative and quantitative results of the patient-specific cutoff with the standard-related cutoff. The qualitative results of the 60 analyses were highly concordant: the presence (20 analyses) or absence (35 analyses) of drug-resistant HIV populations was indicated by both cutoffs in 92% of the analyses (55 analyses), while the presence of drug-resistant HIV populations was indicated in 8% of the analyses (5 analyses) by one cutoff only (Table 4). Assuming that the results obtained by applying the patient-specific cutoff are true, the standard-related cutoff falsely indicated the presence of low-level mutant populations in three patients and failed to detect it in two patients. However, in all five patients, the detected proportions of mutant populations were very low (0.04% to 1.1%).

The quantification results of the 20 analyses indicating the presence of drug-resistant HIV variants differed by more than 10-fold between the two cutoff methods in only four (20%) analyses. In three of them, the standard-related cutoff seemed to overestimate the frequency of mutant populations (2.4% versus 0.05%, 15% versus 1.1%, and >100% versus 3.3%) since population-based sequencing revealed exclusively wild-type HIV in all three patients. All three samples exhibited a mismatch located within the last three bases of the 3′ end of the generic primer, indicated by an elevated CP value of the generic primer. As already discussed, elevated CP values may not only simulate the presence of mutant HIV variants but can also lead to an overestimation of mutant proportions.

Despite these limitations, we consider the use of a standard-based cutoff in the absence of a baseline sample to be a very suitable alternative for generating reliable results in most cases.

Conclusions.

Polymorphisms in the primer-binding site are a general problem for ASPCR assays and can be the reason for underestimation or overestimation of mutant populations by using these techniques (6, 30). Indeed, we found that polymorphisms within the primer-binding site affected the efficiency of amplification of wild-type and mutant alleles.

There are four options to handle these difficulties. First, patient-specific primers designed according to the results of population-based sequencing could be used. However, this option is not suitable for routine use. Second, if a baseline sample prior to antiretroviral drug intake (assumed to be 100% wild type) was stored, a patient-specific cutoff could be determined. Third, special attention has to be paid to samples exhibiting a high CP value in the PCR with the generic primer. We have shown here that abnormally high CPs tend to overestimate or even falsely indicate the presence of mutant populations. Such samples should be omitted from ASPCR analysis. Fourth, increasing the cutoff indicating the presence of mutant populations up to 1% could increase the specificity of the assays but would also lower the sensitivity for low-level mutant populations. In this context, the choice between a falsely detected minor drug-resistant population and the failure to detect existing minor drug-resistant populations has to be made. So far, the clinical implications of low-level mutant populations at a <1% frequency are not really understood. Recently, it was shown (3) that K103N and Y181C mutants below 41% or 33%, respectively, were not detected by a phenotypic assay. This seems to be reassuring, but the main risk of minor drug-resistant HIV variants is their archiving with possible outgrowth under future drug pressure (4, 20, 22, 27, 34). However, an exact threshold for minor drug-resistant variants at which treatment regimens should be changed is not established so far. Since at present no clinician would change a successful ART due to the presence of drug-resistant variants at very low levels only, we believe that it is acceptable to increase the cutoff of ASPCR assays in routine use up to a detection level of 1%.

We have shown that our developed ASPCR assays reliably detected NVP-associated drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 subtype A and D genomes with much higher sensitivity than population-based sequencing. For analysis of subtypes other than A and D, primers and PCR conditions have to be designed very carefully due to the inherent vulnerability of ASPCR assays to polymorphisms. These sensitive methods can be used to detect and quantify NNRTI-resistant minor variants in samples of mothers and children after NVP prophylaxis within a PMTCT intervention. However, the assays can also be applied to samples from patients under long-term ART to monitor the emergence of HIV with NNRTI-associated resistance mutations. Resistance formation is also important from a public health perspective. The transmission of drug-resistant virus should be monitored in each and every country. In resource-limited settings, this is often not feasible. ASPCR assays are cheaper and the performance less time consuming than population-based sequencing. The assays developed here focus on the key NNRTI-associated resistance mutations and could be used to analyze blood and other secretions (e.g., vaginal secretions and semen) to monitor the spread of resistant virus in populations infected with HIV-1 subtypes A and D.

Acknowledgments

We thank all women who participated in this study with their children and the staff of Fort Portal Hospital, Uganda, involved in the sample collection and sample processing procedures. We acknowledge the support of Julia Tesch and Angelina Kus with the sequencing service unit of the RKI (population sequencing). We are grateful for the valuable comments of the reviewers.

The work was supported by the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development through project PN 01.2029.5 (Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV) and by a grant from H. W. & J. Hector Stiftung, Germany.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrivé, E., M. L. Newell, D. K. Ekouevi, M. L. Chaix, R. Thiebaut, B. Masquelier, V. Leroy, P. V. Perre, C. Rouzioux, F. Dabis, and the Ghent Group on HIV in Women and Children. 2007. Prevalence of resistance to nevirapine in mothers and children after single-dose exposure to prevent vertical transmission of HIV-1: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 36:1009-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basson, A. E., M. Ntsala, N. Martinson, E. Tlale, G. E. Corrigan, X. Shao, G. Gray, J. McIntyre, A. Puren, and L. Morris. 2008. Development of phenotypic HIV-1 drug resistance after exposure to single-dose nevirapine. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 49:538-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charpentier, C., D. E. Dwyer, F. Mammano, D. Lecossier, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2004. Role of minority populations of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the evolution of viral resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Virol. 78:4234-4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Church, J. D., S. E. Hudelson, L. A. Guay, S. Chen, D. R. Hoover, N. Parkin, S. A. Fiscus, F. Mmiro, P. Musoke, N. Kumwenda, J. B. Jackson, T. E. Taha, and S. H. Eshleman. 2007. HIV type 1 variants with nevirapine resistance mutations are rarely detected in antiretroviral drug-naive African women with subtypes A, C, and D. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 23:764-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Church, J. D., W. I. Towler, D. R. Hoover, S. E. Hudelson, N. Kumwenda, T. E. Taha, J. R. Eshleman, and S. H. Eshleman. 2008. Comparison of LigAmp and an ASPCR assay for detection and quantification of K103N-containing HIV variants. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 24:595-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dao, H., L. M. Mofenson, R. Ekpini, C. F. Gilks, M. Barnhart, O. Bolu, and N. Shaffer. 2007. International recommendations on antiretroviral drugs for treatment of HIV-infected women and prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197:S42-S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DelRio-LaFreniere, S. A., and R. C. McGlennen. 2001. Simultaneous allele-specific amplification: a strategy using modified primer-template mismatches for SNP detection-application to prothrombin 20210A (factor II) and factor V Leiden (1691A) gene mutations. Mol. Diagn. 6:201-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Oliveira, T., K. Deforche, S. Cassol, M. Salminen, D. Paraskevis, C. Seebregts, J. Snoeck, E. J. van Rensburg, A. M. Wensing, D. A. van de Vijver, C. A. Boucher, R. Camacho, and A. M. Vandamme. 2005. An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics 2:3797-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eshleman, S. H., M. Mracna, L. A. Guay, M. Deseyve, S. Cunningham, M. Mirochnick, P. Musoke, T. Fleming, M. Glenn Fowler, L. M. Mofenson, F. Mmiro, and J. B. Jackson. 2001. Selection and fading of resistance mutations in women and infants receiving nevirapine to prevent HIV-1 vertical transmission (HIVNET 012). AIDS 15:1951-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eshleman, S. H., L. A. Guay, A. Mwatha, S. P. Cunningham, E. R. Brown, P. Musoke, F. Mmiro, and J. B. Jackson. 2004. Comparison of nevirapine (NVP) resistance in Ugandan women 7 days vs. 6-8 weeks after single-dose nvp prophylaxis: HIVNET 012. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 20:595-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eshleman, S. H., D. R. Hoover, S. Chen, S. E. Hudelson, L. A. Guay, A. Mwatha, S. A. Fiscus, F. Mmiro, P. Musoke, J. B. Jackson, N. Kumwenda, and T. Taha. 2005. Resistance after single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis emerges in a high proportion of Malawian newborns. AIDS 19:2167-2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flys, T. S., S. Chen, D. C. Jones, D. R. Hoover, J. D. Church, S. A. Fiscus, A. Mwatha, L. A. Guay, F. Mmiro, P. Musoke, N. Kumwenda, T. E. Taha, J. B. Jackson, and S. H. Eshleman. 2006. Quantitative analysis of HIV-1 variants with the K103N resistance mutation after single-dose nevirapine in women with HIV-1 subtypes A, C, and D. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 42:610-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flys, T. S., D. Donnell, A. Mwatha, C. Nakabiito, P. Musoke, F Mmiro, J. B. Jackson, L. A. Guay, and S. H. Eshleman. 2007. Persistence of K103N-containing HIV-1 variants after single-dose nevirapine for prevention of HIV-1 mother-to-child transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 195:711-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gale, C. V., D. L. Yirrell, E. Campbell, L. Van der Paal, H. Grosskurth, and P. Kaleebu. 2006. Genotypic variation in the pol gene of HIV type 1 in an antiretroviral treatment-naive population in rural southwestern Uganda. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 22:985-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guay, L. A., P. Musoke, T. Fleming, D. Bagenda, M. Allen, C. Nakabiito, J. Sherman, P. Bakaki, C. Ducar, M. Deseyve, L. Emel, M. Mirochnick, M. G. Fowler, L. Mofenson, P. Miotti, K. Dransfield, D. Bray, F. Mmiro, and J. B. Jackson. 1999. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet 354:795-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halvas, E. K., G. M. Aldrovandi, P. Balfe, I. A. Beck, V. F. Boltz, J. M. Coffin, L. M. Frenkel, J. D. Hazelwood, V. A. Johnson, M. Kearney, A. Kovacs, D. R. Kuritzkes, K. J. Metzner, D. V. Nissley, M. Nowicki, S. Palmer, R. Ziermann, R. Y. Zhao, C. L. Jennings, J. Bremer, D. Brambilla, and J. W. Mellors. 2006. Blinded multicenter comparison of methods to detect a drug-resistant mutant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 at low frequency. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2612-2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, J. A., J. F. Li, L. Morris, N. Martinson, G. Gray, J. McIntyre, and W. Heneine. 2005. Emergence of drug-resistant HIV-1 after intrapartum administration of single-dose nevirapine is substantially underestimated. J. Infect. Dis. 192:16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, J. A., J. F. Li, X. Wei, J. Lipscomb, D. Bennett, A. Brant, M. E. Cong, T. Spira, R. W. Shafer, and W. Heneine. 2007. Simple PCR assays improve the sensitivity of HIV-1 subtype B drug resistance testing and allow linking of resistance mutations. PLoS ONE 2:e638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, J. A., J. F. Li, X. Wei, J. Lipscomb, D. Irlbeck, C. Craig, A. Smith, D. E. Bennett, M. Monsour, P. Sandstrom, E. R. Lanier, and W. Heneine. 2008. Minority HIV-1 drug resistance mutations are present in antiretroviral treatment-naïve populations and associate with reduced treatment efficacy. PLoS Med. 5:e158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jourdain, G., N. Ngo-Giang-Huong, S. Le Coeur, C. Bowonwatanuwong, P. Kantipong, P. Leechanachai, S. Ariyadej, P. Leenasirimakul, S. Hammer, M. Lallemant, and the Perinatal HIV Prevention Trial Group. 2004. Intrapartum exposure to nevirapine and subsequent maternal responses to nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:229-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lecossier, D., N. S. Shulman, L. Morand-Joubert, R. W. Shafer, V. Joly, A. R. Zolopa, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2005. Detection of minority populations of HIV-1 expressing the K103N resistance mutation in patients failing nevirapine. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 38:37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockman, S., R. L. Shapiro, L. M. Smeaton, C. Wester, I. Thior, L. Stevens, F. Chand, J. Makhema, C. Moffat, A. Asmelash, P. Ndase, P. Arimi, E. van Widenfelt, L. Mazhani, V. Novitsky, S. Lagakos, and M. Essex. 2007. Response to antiretroviral therapy after a single, peripartum dose of nevirapine. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:135-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loubser, S., P. Balfe, G. Sherman, S. Hammer, L. Kuhn, and L. Morris. 2006. Decay of K103N mutants in cellular DNA and plasma RNA after single-dose nevirapine to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission. AIDS 20:995-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maga, G., M. Amacker, N. Ruel, U. Hübscher, and S. Spadari. 1997. Resistance to nevirapine of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutants: loss of stabilizing interactions and thermodynamic or steric barriers are induced by different single amino acid substitutions. J. Mol. Biol. 274:738-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzner, K. J., P. Rauch, H. Walter, C. Boesecke, B. Zöllner, H. Jessen, K. Schewe, S. Fenske, H. Gellermann, and H. J. Stellbrink. 2005. Detection of minor populations of drug-resistant HIV-1 in acute seroconverters. AIDS 19:1819-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzner, K. J., S. G. Giulieri, S. A. Knoepfel, P. Rauch, P. Burgisser, S. Yerly, H. F. Günthard, and M. Cavassini. 2009. Minority quasispecies of drug-resistant HIV-1 that lead to early therapy failure in treatment-naive and -adherent patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer, S., V. Boltz, F. Maldarelli, M. Kearney, E. K. Halvas, D. Rock, J. Falloon, R. T. Davey, Jr., R. L. Dewar, J. A. Metcalf, J. W. Mellors, and J. M. Coffin. 2006. Selection and persistence of non-nucleosid reverse transcriptase inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 in patients starting and stopping non-nucleoside therapy. AIDS 20:701-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer, S., V. Boltz, N. Martinson, F. Maldarelli, G. Gray, J. McIntyre, J. Mellors, L. Morris, and J. Coffin. 2006. Persistence of nevirapine-resistant HIV-1 in women after single-dose nevirapine therapy for prevention of maternal-to-fetal HIV-1 transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:7094-7099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paredes, R., V. C. Marconi, T. B. Campbell, and D. R. Kuritzkes. 2007. Systematic evaluation of allele-specific real-time PCR for the detection of minor HIV-1 variants with pol and env resistance mutations. J. Virol. Methods 146:136-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pillay, V., J. Ledwaba, G. Hunt, M. Rakgotho, B. Singh, L. Makubalo, D. E. Bennett, A. Puren, and L. Morris. 2008. Antiretroviral drug resistance surveillance among drug-naive HIV-1-infected individuals in Gauteng Province, South Africa in 2002 and 2004. Antivir. Ther. 13(Suppl. 2):101-107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayfield, M. A., R. G. Downing, J. Baggs, D. J. Hu, D. Pieniazek, C. C. Luo, B. Biryahwaho, R. A. Otten, S. D. Sempala, and T. J. Dondero. 1998. A molecular epidemiologic survey of HIV in Uganda. AIDS 12:521-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowley, C. F., C. L. Boutwell, S. Lockman, and M. Essex. 2008. Improvement in allele-specific PCR assay with the use of polymorphism-specific primers for the analysis of minor variant drug resistance in HIV-1 subtype C. J. Virol. Methods 149:69-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simen, B. B., J. F. Simons, K. H. Hullsiek, R. M. Novak, R. D. Macarthur, J. D. Baxter, C. Huang, C. Lubeski, G. S. Turenchalk, M. S. Braverman, B. Desany, J. M. Rothberg, M. Egholm, M. J. Kozal, and the Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. 2009. Low-abundance drug-resistant viral variants in chronically HIV-infected, antiretroviral treatment-naive patients significantly impact treatment outcomes. J. Infect. Dis. 199:693-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stringer, J. S., M. Sinkala, V. Chapman, E. P. Acosta, G. M. Aldrovandi, V. Mudenda, J. P. Stout, R. L. Goldenberg, R. Kumwenda, and S. H. Vermund. 2003. Timing of the maternal drug dose and risk of perinatal HIV transmission in the setting of intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine. AIDS 17:659-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.UNAIDS/W.H.O. 2007. AIDS epidemic update: December 2007. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 37.Walter, H., B. Schmidt, K. Korn, A. M. Vandamme, T. Harrer, and K. Uberla. 1999. Rapid, phenotypic HIV-1 drug sensitivity assay for protease and reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J. Clin. Virol. 13:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]