Abstract

Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) causes hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). The rates of STEC infection and complications, including death, are highest among young children and elderly individuals. There are no causal therapies. Because Stx is the primary pathological agent leading to organ injury in patients with STEC disease, therapeutic antibodies are being developed to neutralize systemically absorbed toxin during the early phase of the infection. Two phase I, single-dose, open-label, nonrandomized studies were conducted to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of the chimeric monoclonal antibodies (antitoxins) against Stx 1 and 2 (cαStx1 and cαStx2, respectively). In the first study, 16 volunteers received 1 or 3 mg/kg of body weight of cαStx1 or cαStx2 as a single, short (1-h) intravenous infusion (n = 4 per group). In a second study, 10 volunteers received a 1-h infusion of cαStx1 and cαStx2 combined at 1 or 3 mg/kg (n = 5 per group). Treatment-emergent adverse events were mild, resolved spontaneously, and were generally unrelated to the antibody infusion. No serious adverse events were observed. Human antichimeric antibodies were detected in a single blood sample collected on day 57. Antibody clearance was slightly greater for cαStx1 (0.38 ± 0.16 ml/h/kg [mean ± standard deviation]) than for cαStx2 (0.20 ± 0.07 ml/h/kg) (P = 0.0013, t test). The low clearance is consistent with the long elimination half-lives of cαStx1 (190.4 ± 140.2 h) and cαStx2 (260.6 ± 112.4 h; P = 0.151). The small volume of distribution (0.08 ± 0.05 liter/kg, combined data) indicates that the antibodies are retained within the circulation. The conclusion is that cαStx1 and cαStx2, given as individual or combined short intravenous infusions, are well tolerated. These results form the basis for future safety and efficacy trials with patients with STEC infections to ameliorate or prevent HUS and other complications.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing E. coli serotypes are important food-borne pathogens (9, 11, 20, 25). Their clinical significance is tightly linked to their recent, evolutionary acquisition of Stx-encoding phages and other genetic material that contributes to their infectivity and pathogenicity in humans (15). Patients with Stx-producing E. coli (STEC) infections present with abdominal cramps and acute diarrhea, ranging from mild watery diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis. Grossly bloody diarrhea is noted in 30 to 70% of cases (4, 13, 25), and up to one-third of STEC-infected patients are hospitalized (1, 25). While most patients recover spontaneously, 5 to 15% of affected children develop hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) about 7 days after the onset of diarrhea (25). HUS manifests acutely with the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and kidney injury (22, 25). It is a major cause of acute renal failure in children (22), and ∼40% require acute dialysis (26); occasionally, it leads to end-stage kidney disease and the need for chronic renal replacement therapy and kidney transplantation. In elderly individuals, STEC infection is associated with substantial mortality, with and without HUS (3, 4, 5, 7).

Current evidence suggests that Stx(s) constitutes the major pathogenic factor implicated in the pathogenesis of HUS (15, 25). Stx comprises a group of highly related, soluble, bipartite protein toxins consisting of a pentameric, cell membrane-binding B subunit and a noncovalently linked, enzymatically (intracellularly) active A subunit (16). A limited number of serologically and molecularly distinguishable Stxs have been linked to severe disease in humans, notably, Stx1, Stx2, Stx2c, and Stx2dactivatable. STEC isolates from patients with hemorrhagic colitis or HUS may express one or more Stxs in various combinations (2, 4, 10, 12, 14, 17, 20), but the contribution of each toxin in vivo to the severity of STEC disease is not known.

At present, there is no specific, proven treatment for STEC disease or the prevention of its complications (18, 26, 27), nor are there early, reliable predictors of the severity of the disease. The rapid diagnosis of STEC infection and early intervention before the onset of systemic diseases are therefore desirable to prevent or ameliorate toxin-related complications, including HUS. Therapeutic chimeric monoclonal antibodies against Stx 1 and 2 (cαStx1 and cαStx2, respectively) that neutralize Stx in vivo and protect mice from lethal STEC infection or toxemia have been developed (8, 21).

The safety and pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles of cαStx2 but not those of cαStx1 have previously been formally evaluated and published in an NIAID, NIH-sponsored phase I study (6). The aims of the current study were to determine the tolerability and the PK profile of cαStx1 in comparison to those of cαStx2 and to evaluate the safety of the combined infusion of both antitoxins in healthy human volunteers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development of cαStx1 and cαStx2.

cαStx1 is a hybrid (chimeric) antibody in which the variable regions of the murine Stx1-neutralizing monoclonal antibody 13C4 (24) are genetically fused to a human kappa light chain constant-domain sequence and a human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) heavy chain constant-domain sequence (8). cαStx1 is directed against the B subunit of Stx1 (23), which mediates binding of the holotoxin to the globotriaosylceramide cell surface receptor (16). cαStx2 is a chimeric antibody in which the variable regions of Stx2-neutralizing murine monoclonal antibody 11E10 (19) are genetically fused to a human kappa light chain constant-domain sequence and a human IgG1 heavy chain constant-domain sequence (8). cαStx2 recognizes the enzymatic A subunit of Stx2 (19), which is responsible for the primary biological action of the toxin in the host cell (16). The final chimeric antibodies were produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells. The percentage of the antibody sequences that are human based for cαStx1 and cαStx2 are 84% and 86.3%, respectively. The chimeric antibodies were manufactured under current good manufacturing practice regulations by Goodwin Biotechnology Inc. under contract to Thallion Pharmaceuticals Inc. They were supplied in 2-ml vials containing 2 ml of 10 ± 0.5 mg/ml product in an acetate-buffered saline solution and kept at 2 to 8°C until use.

In an in vitro Vero cell assay, 1 pg of purified Stx1 was neutralized by 26 ng of cαStx1, where 1 pg of toxin corresponds to a 50% cytotoxic dose (CD50). The neutralization titer was defined as the dilution of the antibody that neutralized 50% of the cytotoxic effect on Vero cells. Under similar conditions, 82.8 ng of cαStx2 neutralized 1 pg (1 CD50) of purified Stx2 (8).

Clinical studies.

Two phase I studies were conducted. One was conducted in the United States (SFBC Fort Myers, Fort Myers, FL) and one was conducted in Canada (Algorithme Pharma, Montréal, Québec, Canada). The research complied with all relevant governmental regulations and guidelines and was approved by the pertinent ethical review committees for human subjects (IntegReview, Inc, Austin, TX; Ethicom, Université de Montréal, Québec, Canada). Written informed consent was obtained from each participating subject. Both studies were designed as single-center, open-label, nonrandomized, dose-escalation studies. The primary objective of the two clinical phase I studies, conducted with healthy male and female adult volunteers, was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of the cαStx1 and cαStx2 antibodies, administered as single (cαStx1, cαStx2) or dual (cαStx1 and cαStx2) intravenous infusions. The secondary objectives of the studies were to (i) evaluate the PKs of cαStx1 and cαStx2 and (ii) assess the development of human antichimeric antibodies (HACAs), including HACA Ig subclass typing. The antibodies administered, the dosages, and the cohorts are listed in Table 1. The study drug (one antitoxin or both antitoxins combined) was diluted in 100 ml of isotonic saline and infused over 1 h at a rate of 100 ml/h through a dedicated peripheral intravenous line. A second peripheral venous access on the contralateral arm was used to withdraw blood for the initial PK studies.

TABLE 1.

Study population and treatment

| No. of participants | Dose received (mg/kg)

|

Subject nos. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| cαStx1 | cαStx2 | ||

| 4 | 1 | 1-4 | |

| 4 | 3 | 5-8 | |

| 4 | 1 | 9-12 | |

| 4 | 3 | 13-16 | |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 17-21a |

| 5 | 3 | 3 | 22-26 |

One of the subjects (subject 19) was lost to follow-up 3 days after the infusion of the antibodies.

The subjects were evaluated on days −1 (screening); 1 (antibody infusion); and 2, 4, 8, 15, 29, 43, and 57. The evaluations included subject reporting of adverse events (AE) and serious AEs, a review of laboratory test results (biochemistry, hematology, and urinalysis, except on days 1 and 43), determination of vital signs and body weight (days −1, 8, and 57), review of electrocardiography (ECG) tracings (days −1, 1, 2, 8, 15, and 57), performance of a physical examination, and determination of whether the subject concomitantly used other medications. The medical safety committee reviewed the laboratory test results, the ECG tracings, the vital signs, and the reported AEs at predetermined times during the conduct of each study. Analyses were based on the safety population, which comprised all enrolled participants who received any amount of study medication. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were recorded and analyzed by system organ class at the preferred term level by using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 9.0.

PKs.

Blood samples for PK analysis were collected before and 0.25, 0.5, and 1 h (end of study medication infusion); 1.25, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 12, and 24 h (day 2); and 3, 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56 days after the start of the infusion. Serum samples were stored at −70°C and were tested for cαStx1 and cαStx2 levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), under contract with Altor BioScience Corporation, FL.

Serum anti-Stx1 and anti-Stx2 concentrations were measured by the use of an ELISA plate format developed at Sunol Molecular Corporation, a sister company of Altor BioScience. The assay was performed essentially as described previously (6), with several modifications. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (MaxiSorp 8-well strip modules; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 100 μl per well of 1 μg/ml purified Stx1 or Stx2 (provided by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2). The coated wells were blocked with 150 μl of PBS containing 1% gelatin (Norland Products, Cranbury, NJ), 0.5% Tween 20 (Mallinckrodt, Baker, Paris, KY), and 5% normal goat serum (Equitech Bio, Kerrville, TX) for 45 min at 37°C. Standards, controls, and samples were diluted 1:300 in the same blocking buffer. Samples whose anti-Stx1 or anti-Stx2 concentration exceeded the highest standard (50 ng/ml after dilution) were serially diluted to bring the assayed concentrations within the range of the standard curve. The diluted samples were transferred to the respective wells in triplicate, the plates were incubated and washed, and then 100 μl of 1:40,000 goat anti-human IgG (heavy and light chains)-peroxidase conjugate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in blocking buffer was added. The assays were developed with 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (BioFX, Owings Mills, MD). The reaction was stopped with 100 μl of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and the plates were read at 405 nm in a spectrophotometer. The results were calculated from a four-parameter logistic curve-fit equation. Predose values were subtracted from all postdose values due to the observation during assay development that a percentage of the population has circulating preformed antibodies to Stx1. Only one subject (subject 7) in the single-antibody study (cαStx1 at 3 mg/kg of body weight) was noted to have an elevated predose value.

Noncompartmental analyses of the plasma αStx1 and cαStx2 concentrations were accomplished with WinNonlin Professional (version 3.1) software (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA). PK parameter estimates were obtained for the maximum concentration in plasma (Cmax), exponential volume of distribution (Vz), clearance (CL), elimination rate constant (kel), elimination half-life (t1/2), time to Cmax (Tmax), the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) from time zero to the last sampling time (AUCt), and the AUC extrapolated to infinity (AUC∞).

Assessment of HACAs.

HACA levels were measured before and 28, 42, and 56 days after the cαStx infusion(s) at MPI Research Inc. (Mattawan, MI) by a validated ELISA developed at MPI Research. Briefly, 96-well plates (96-well, MaxiSorp or equivalent; Nunc) were coated overnight at 2 to 8°C with 100 μl cαStx1 or cαStx2 in 1× PBS (Fischer Biotech, Waltham, MA) at a final concentration of 500 ng/ml (50 ng/well). Between each step, the wells were rinsed four times with 1× PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) washing buffer (PBS-T) and tapped on paper towels to remove the residual liquid. The wells were blocked with 200 μl of 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in PBS-T at room temperature (RT) for 2 h, washed, and used immediately or stored at 2 to 8°C for up to 11 days.

Diluted serum samples, standards, and quality control samples (100 μl/well) were added to duplicate or triplicate wells, and the plates were incubated at RT for about 2 h. The plates were washed, and detection antibody solution (100 μl) containing biotinylated cαStx1 or biotinylated cαStx2 (MPI Research) in assay diluent (0.5 g bovine serum albumin in 500 ml of 1× PBS-T) was added to each well. The plates were incubated at RT for 1 h and washed. Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) solution (100 μl) was added to each well and the plates were incubated at RT for 0.5 h. The plates were washed, and 100 μl of Ultra-TMB substrate solution (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was added to each well. The reaction was stopped after 10 to 29 min at RT with 50 μl of 2 M sulfuric acid (Sigma).

The optical density at 450 nm was determined with a microplate reader by using SoftMax Pro software (Molecular Diagnostics, Sunnyvale, CA). A standard curve was created and used to generate a four-parameter logistic curve fit. The concentrations of the unknowns were determined with SoftMax Pro software.

To determine the HACA Ig isotype(s), microtiter plates were coated with cαStx1 or cαStx2, as described above. The wells were loaded with 100 μl of a 1:100 dilution of the subjects’ serum samples, incubated at RT for about 2 h, and washed as described above. A second binding step was completed by adding 100 μl of diluted biotinylated goat/mouse anti-human Ig isotype antibody(goat anti-human IgA and IgM [MPI Research], mouse anti-human IgG subclasses [Sigma]) to each well in the corresponding column on the ELISA plate in duplicate for each sample tested. The plates were incubated at RT for 1 h and washed. One hundred microliters of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase solution was added and the plates were incubated for ∼1 h at RT. The plates were washed, Ultra-TMB substrate solution (100 μl) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at RT for 5 min. The reactions were stopped with 50 μl 2 M sulfuric acid, and the optical density at 450 nm was determined as described above.

RESULTS

Safety in volunteers.

Twenty-six healthy volunteers between the ages of 19 and 53 years were enrolled between 7 February and 24 July 2006 (Table 1). Seventeen subjects were female (65%), and 23 (88%) were Caucasian. Twenty-five subjects completed the study. One participant (subject 19) in the group receiving the combination of 1 mg/kg cαStx1 and 1 mg/kg cαStx2 was lost to follow-up after the day 2 visit. No serious AEs were observed or reported by the subjects, and no deaths occurred. None of the volunteers withdrew from trial participation due to an AE. Eighteen volunteers (69%) reported at least one (mild or moderate) TEAE up to 14 days after the infusion of the investigational product. No clinically relevant changes in body weight, vital signs (oral temperature, respiratory rate, blood pressure, pulse), physical examination or ECG findings were noted.

The types and frequencies of TEAEs and the product dosages are summarized in Table 2. The most frequently reported events were headache and somnolence (19% each), upper respiratory tract infection or influenza (15%), gastrointestinal complaints (abdominal distention, 12%; abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, 8% each), and fever (8%). Irritation and erythema at the intravenous catheter site for the antibody infusion were noted in 8% of the subjects. Laboratory abnormalities included pyuria (n = 12%) and mild hypocalcemia, microhematuria, neutrophilia, and thrombocytosis (4% each). Overall, there was no association between the occurrence of AEs and the cαStx dose or between the administration of single or dual antibodies. Apparent exceptions were headache, somnolence, and abdominal distention (skewed toward the occurrence in subjects undergoing dual antibody administration) and influenza-like symptoms (skewed toward occurring in probands receiving a single antibody) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

TEAEs associated with the single or dual infusion of anti-Stx antibody

| Signs and symptomsa | No. (%) of subjects in the following treatment group

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cαStx1 (1 mg/kg, n = 4) | cαStx1 (3 mg/kg, n = 4) | cαStx2 (1 mg/kg, n = 4) | cαStx2 (3 mg/kg, n = 4) | cαStx1/cαStx2 (1 mg/kg, n = 5) | cαStx1/cαStx2 (3 mg/kg, n = 5) | Total (n = 26) | |

| Headache | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 (19) |

| Somnolence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 (19) |

| Influenza, URTI,b pharyngitis | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (15) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (12) |

| Muscle, skeletal, or joint pain | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (12) |

| Pyuria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 (12) |

| Dysuria, urinary tract infection | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (8) |

| Nausea, vomiting | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 (8) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 (8) |

| Fever | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Irritation at intravenous catheter infusion site | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (8) |

| Irritation at intravenous catheter blood draw site | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Skin irritation, other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| Aphonia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Breast pain | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Hyperactivity | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Hypocalcemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Microhematuria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Neutrophilia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| Numbness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (4) |

| Thrombocytosis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

Signs and symptoms reported up to 14 days following the antibody infusion. Most adverse events were considered by the investigators and the Medical Safety Committee to be not related or only remotely related to the treatment (see text).

URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

A detailed analysis of the AEs relative to the time of product infusion is shown in Table 3. Somnolence was reported before treatment began in three of five probands (subjects 19, 20, and 23), as was headache in two of three instances (subjects 18 and 23). Both occurrences of intravenous infusion site irritation were detected prior to drug administration (subjects 20 and 24). Pharyngitis, fever, muscle or joint pain, and headache, with or without gastrointestinal symptoms, clustered in a few patients with influenza-like illness with onset 10 to 14 days after the antibody infusion (subjects 3, 4, 5, and 12). None of the volunteers demonstrated an immediate (30 min to 2 h) or delayed infusion reaction (during the following 24 h). However, four subjects (15%) complained of somnolence (subjects 17 to 19 and 23), headache (subjects 17, 18, and 23), or nausea (subject 23). Somnolence and headache were noted prior to the antibody infusion in one individual (subject 23), who also experienced nausea, as were somnolence (subjects 19 and 20) and headache alone (subject 18) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Detailed analysis of TEAEs associated with anti-Stx antibody infusiona

| Treatment | TEAE | No. of volunteers with symptoms | Subject no. | Onset (time after infusionc) | Severityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cαStx1 (1 mg/kg) | Thrombocytosis | 1 | 3 | 7 days | Mild |

| Influenza (URTI,d pharyngitis, cough) | 1 | 3 | 10 days | Mild | |

| Back pain | 1 | 3 | 11 days | Mild | |

| Headache, chills | 1 | 3 | 13 days | Mild | |

| Fever | 1 | 3 | 14 days | Moderate | |

| Breast pain | 1 | 4 | 6 days | Moderate | |

| Headache | 1 | 4 | 11 days | Moderate | |

| URTI (sore throat) | 1 | 4 | 12 days | Mild | |

| cαStx1 (3 mg/kg) | Influenza (fever, dizziness, muscle or joint pain, conjunctivitis) | 1 | 5 | 10 days | Mild/moderate |

| Nausea, vomiting | 1 | 5 | 10 days | Moderate/mild | |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 5 | 11 days | Moderate | |

| Hyperactivity | 1 | 8 | 4 days | Mild | |

| cαStx2 (1 mg/kg) | Urinary tract infection (twice) | 1 | 9 | 3 days, 14 days | Mild |

| Aphonia | 1 | 12 | 3 days | Moderate | |

| Influenza (pharyngitis, arthralgia) | 1 | 12 | 13 days | Mild | |

| cαStx2 (3 mg/kg) | Microhematuria | 1 | 13 | 3 days | Mild |

| Pyuria | 1 | 15 | 3 days | Mild | |

| cαStx1 and cαStx2 (1 mg/kg each) | Somnolence | 4 | 17 | 70 min | Moderate |

| 18 | 60 min | Mild | |||

| 19 | −100 min, 72 min | Mild/moderate | |||

| 20 | −44 min | Moderate | |||

| Headache | 2 | 17 | 5 h | Mild | |

| 18 | −1 h | Mild | |||

| Irritation IV catheter blood draw site | 2 | 19 | 21 h | Mild | |

| 20 | −2 h | Mild | |||

| Irritation at intravenous catheter infusion site | 1 | 20 | −2 h | Mild | |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 20 | 6 h | Moderate | |

| Lymphadenopathy (inguinal) | 1 | 18 | 12 days | Mild | |

| Dysuria | 1 | 21 | 3 days | Mild | |

| cαStx1 and cαStx2 (3 mg/kg each) | Abdominal distention | 1 | 22 | 5 h | Moderate |

| Abdominal distention | 1 | 25 | 6.5 h | Mild | |

| Abdominal distention | 1 | 26 | 11 h | Mild | |

| Diarrhea, abdominal pain | 1 | 22 | 5 h | Mild | |

| Nausea | 1 | 23 | 2.5 h | Mild | |

| Headache | 1 | 23 | −19 min, 3 h | Mild/moderate | |

| Somnolence | 1 | 23 | −19 min, 45 min | Mild/moderate | |

| Irritation at intravenous catheter (infusion site) | 1 | 24 | −80 min | Mild | |

| Skin irritation (other) | 1 | 26 | 4.5 days | Mild | |

| Numbness (occipital) | 1 | 25 | During infusion | Mild | |

| Pyuria | 2 | 25 | 22 h | Moderate | |

| 26 | 14 days | Mild | |||

| Neutrophilia | 1 | 25 | 3 days | Mild | |

| Hypocalcemia | 1 | 25 | 7 days | Mild |

Most signs and symptoms were considered not related or only remotely related to the antibody infusion.

All signs and symptoms resolved without complications or specific therapy.

Negative values denote events reported prior to the begin of the infusion of the investigational product.

URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

PKs.

For the primary analysis, the PK parameters from the two studies were combined, because the number of subjects was small. The resultant descriptive statistics are presented in Table 4. The cαStx1 Cmax, AUCt, and AUC∞ values directly correlated with the infused antibody dose and were proportionally greater in individuals who received 3 mg/kg antibody than in those who received 1 mg/kg antibody. The Tmaxs of cαStx1 were calculated to be 3.44 and 3.97 h for the 1- and 3-mg/kg doses, respectively. As expected, CL remained fairly constant between the two dose levels (0.34 and 0.41 ml/h/kg). Vz varied between the two doses (0.06 to 0.11 liter/kg); however, this was related to the high coefficient of variation (CV) for the recipients of the 3-mg/kg dose. Differences in the t1/2s between the 1- and 3-mg/kg doses, i.e., 157.2 and 215.3 h, respectively, are likely due to large variations and the small sample size.

TABLE 4.

Summary of pharmacokinetic parameters obtained with single dose intravenous cαSx1 and cαStx2 administered individually or concomitantlya

| Antibody (dose) | Parameter | Cmax (mg/liter) | Tmax (h) | AUC∞b (mg · h/ml) | t1/2b (hours) | CLb (ml/h/kg) | Vzb (liters/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cαStx1 (1.0 mg/kg) | Mean | 24.934 | 3.44 | 3,788.946 | 157.21 | 0.34 | 0.06 |

| SD | 3.565 | 2.64 | 2,461.255 | 83.44 | 0.15 | 0.01 | |

| CV (%) | 14.3 | 76.5 | 65.0 | 53.1 | 44.9 | 14.2 | |

| No. of subjects | 9 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| cαStx1 (3.0 mg/kg) | Mean | 73.209 | 3.97 | 8,683.858 | 215.32 | 0.41 | 0.11 |

| SD | 21.821 | 3.55 | 4,305.828 | 172.85 | 0.17 | 0.8 | |

| CV (%) | 29.8 | 89.4 | 49.6 | 80.3 | 40.7 | 71.9 | |

| No. of subjects | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| cαStx2 (1.0 mg/kg) | Mean | 25.302 | 3.53 | 5,470.119 | 315.96 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

| SD | 4.849 | 2.94 | 1,894.649 | 165.35 | 0.10 | 0.03 | |

| CV (%) | 19.2 | 83.1 | 34.6 | 52.3 | 48.8 | 38.9 | |

| No. of subjects | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| cαStx2 (3.0 mg/kg) | Mean | 88.125 | 3.11 | 15,520.314 | 223.68 | 0.20 | 0.06 |

| SD | 17.323 | 2.00 | 3,825.125 | 34.51 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| CV (%) | 19.7 | 64.2 | 24.6 | 15.4 | 23.4 | 23.7 | |

| No. of subjects | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

Data were analyzed by noncompartmental PK methods.

Due to the lack of a log-linear decay, the slope of the terminal log-linear phase (λz) and parameters dependent on λz, AUC∞, t1/2, CL, and Vz, could not be estimated for all subjects.

Similar to cαStx1, the Cmax, AUCt, and AUC∞ values for cαStx2 were directly proportional to the dose levels (1 and 3 mg/kg). The Tmaxs of cαStx2 were estimated to be 3.11 and 3.53 h for the two doses, respectively. As expected, CL (0.20 and 0.21 ml/h/kg, respectively) and Vz (0.06 and 0.08 liter/kg, respectively) remained constant between the two dose levels.

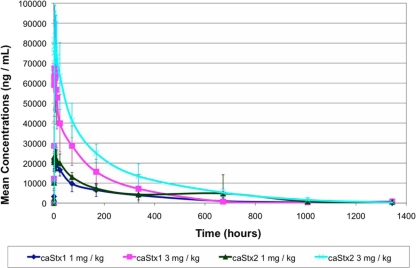

Despite the small size of the trial, a subanalysis was performed to detect possible differences between the PK parameters of the two antibodies. A difference was noted between the CLs of cαStx1 (0.38 ± 0.16 ml/h/kg) and cαStx2 (0.20 ± 0.07 ml/h/kg), when the data for both dose levels were combined, that was statistically significant (P = 0.0013, t test). The difference between the inversely related t1/2s of cαStx1 (190.4 ± 140.2 h) and cαStx2 (260.6 ± 112.4 h), however, did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.151). When the results for the single and the combined antibody infusions were compared, the CLs and t1/2s were similar (P = 0.36 to 0.96). The mean measured plasma concentrations of cαStx1 and cαStx2 following the infusion are depicted in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Profile of the mean serum concentrations of cαStx1 and cαStx2 for each dose level on a linear scale. Error bars denote ± 1 standard deviation. No data were available for the last time point from the subjects receiving cαStx1 at 1 mg/kg.

HACAs.

HACAs were detected in one subject, who received 3 mg/kg cαStx2, in a single blood sample from day 57. The antichimeric antibody was characterized as IgG1. None of the subjects who received cαStx1 alone or concomitantly with cαStx2 demonstrated HACAs toward cαStx1.

DISCUSSION

The present report comprises the descriptions of two phase I studies evaluating the safety and tolerability of intravenous infusions of the chimeric anti-Stx antibodies cαStx1 and cαStx2. At the chosen doses of 1 and 3 mg/kg, both antibodies were well tolerated individually as well as in combination. Furthermore, the doses tested achieved concentrations that exceeded those found to protect mice from lethal STEC infection or toxemia (21). Our results confirm and extend the safety and PK data previously accrued in an NIAID, NIH-sponsored phase I trial in which 17 healthy adult volunteers had been given cαStx2 over a 3-log dose range (0.1 to 10 mg/kg) (6).

cαStx1 and cαStx2 were equally well tolerated and demonstrated similar PK profiles. Importantly, the concomitant infusion of the two antibodies did not appear to alter their PK profiles. The mean elimination t1/2 of 9 days suggests that a single dose of the antitoxin(s) is sufficient to bridge the period between the onset of (or presentation with) diarrhea and the development of HUS and other toxin-induced sequelae. It should be emphasized that cαStx2 neutralizes not only Stx2 derived from the prototypic enterohemorrhagic E. coli strain EDL933 but also Stx2c and Stx2dactivatable (8), which have been etiologically linked with HUS (2, 14).

No severe AEs were observed. The mild and moderate TEAEs were neither antitoxin specific nor dose dependent. Clinical AEs judged to be possibly related to the product were abdominal pain and distension, somnolence, and headache (Table 2). The abdominal symptoms observed on the day of the antibody infusion were generally mild, occurred between 5 and 11 h after the infusion, and resolved spontaneously. This effect has not been noted in any of the 16 recipients of a single dose of cαStx1 or αStx2 or in the previously reported study, in which cαStx2 was administered up to a dose of 10 mg/kg (6). Its clinical significance is unclear and needs to be reassessed in a controlled trial. Somnolence was documented in 5 of 10 volunteers receiving a dual infusion of cαStx1 and αStx2. Three subjects became somnolent prior to the antibody administration and two became somnolent about an hour after the antibody administration (Table 3). A simple, plausible explanation is that the volunteers were tired because they had been awakened for the antibody infusion as early as 5 a.m. Other TEAEs that were observed during the 14 days following the antibody infusion, such as pharyngitis, influenza-like illnesses, and dysuria or urinary tract infections (Table 3), did not appear to be related to the administration of the investigative product. Importantly, the volunteers did not experience significant infusion reactions.

The risk of sensitization to the chimeric antibodies appears to be low: in the current study, only one individual (3.8%) mounted a reproducible and specific immune response to cαStx2. In the phase I study reported by Dowling et al., four individuals (23.5%) developed HACAs (6). The apparent difference in the rate of HACA formation between the current and previous studies is unclear but may be related to methodological differences (the use of different assay formats). Antichimeric antibodies developed late: all HACA-positive samples in the current and the previous studies (6) were detected after day 42. Therefore, HACA formation is not expected to interfere with the antitoxin's postulated therapeutic action during an acute STEC infection.

The clinically important question, whether the infusion of Stx-neutralizing antibodies in patients with STEC infection can reduce the incidence of HUS or other clinically relevant outcomes, remains to be answered in a controlled treatment trial. In order to exploit the (hypothetical) therapeutic window and intervene with an effective, neutralizing antibody or antibody cocktail, enrollment early in the course of the illness will be critical (3).

In conclusion, the chimeric monoclonal antibodies cαStx1 and cαStx2 were safe and well tolerated when they were administered individually or concomitantly to healthy male and female adults at doses of up to 3 mg/kg each. Current and previously published data provide the basis for treatment trials for assessment of the safety, PKs, and efficacy of the concomitantly administered antitoxins in the target patient population. Monoclonal antibodies represent an interesting avenue for the protection of humans from the severe, Stx-mediated consequences of STEC infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the volunteers from the Montreal and Miami, Florida, areas who participated in these research trials. Likewise, we thank Altor BioScience, which conducted the PK assays; the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, which provided the toxin reagents; and Eric Soliman and Eric Thibaudeau, who provided technical oversight and reviewed the paper. We also thank Allison D. O'Brien and Angela Melton-Celsa for valuable discussions and advice.

M.B. served as clinical consultant for Thallion Pharmaceuticals Inc. At the time of the study, R.P., M.M., C.T.-R., and M.R. were employees of Thallion Pharmaceuticals Inc. (formerly Caprion Pharmaceuticals Inc.); and E.S. was an employee of Algorithme Pharma Inc.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell, B. P., P. M. Griffin, P. Lozano, D. L. Christie, J. M. Kobayashi, and P. I. Tarr. 1997. Predictors of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children during a large outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. Pediatrics 100:E12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bielaszewska, M., A. W. Friedrich, T. Aldick, R. Schurk-Bulgrin, and H. Karch. 2006. Shiga toxin activatable by intestinal mucus in Escherichia coli isolated from humans: predictor for a severe clinical outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:1160-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bitzan, M. 2009. Treatment options for HUS secondary to Escherichia coli O157:H7. Kidney Int. 75(Suppl. 112):S62-S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco, J. E., M. Blanco, M. P. Alonso, A. Mora, G. Dahbi, M. A. Coira, and J. Blanco. 2004. Serotypes, virulence genes, and intimin types of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from human patients: prevalence in Lugo, Spain, from 1992 through 1999. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:311-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter, A. O., A. A. Borczyk, J. A. Carlson, B. Harvey, J. C. Hockin, M. A. Karmali, C. Krishnan, D. A. Korn, and H. Lior. 1987. A severe outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated hemorrhagic colitis in a nursing home. N. Engl. J. Med. 317:1496-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowling, T. C., P. A. Chavaillaz, D. G. Young, A. Melton-Celsa, A. O'Brien, C. Thuning-Roberson, R. Edelman, and C. O. Tacket. 2005. Phase 1 safety and pharmacokinetic study of chimeric murine-human monoclonal antibody c alpha Stx2 administered intravenously to healthy adult volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1808-1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dundas, S., W. T. Todd, A. I. Stewart, P. S. Murdoch, A. K. Chaudhuri, and S. J. Hutchinson. 2001. The central Scotland Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak: risk factors for the hemolytic uremic syndrome and death among hospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:923-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards, A. C., A. R. Melton-Celsa, K. Arbuthnott, J. R. Stinson, C. K. Schmitt, H. C. Wong, and A. D. O'Brien. 1998. Vero cell neutralization and mouse protective efficacy of humanized monoclonal antibodies against Escherichia coli toxins Stx1 and Stx2, p. 388-392. In J. B. Kaper and A. D. O'Brien (ed.), Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 9.Elliott, E. J., R. M. Robins-Browne, E. V. O'Loughlin, V. Bennett-Wood, J. Bourke, P. Henning, G. G. Hogg, J. Knight, H. Powell, and D. Redmond. 2001. Nationwide study of haemolytic uraemic syndrome: clinical, microbiological, and epidemiological features. Arch. Dis. Child. 85:125-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedrich, A. W., M. Bielaszewska, W. L. Zhang, M. Pulz, T. Kuczius, A. Ammon, and H. Karch. 2002. Escherichia coli harboring Shiga toxin 2 gene variants: frequency and association with clinical symptoms. J. Infect. Dis. 185:74-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karch, H., M. Bielaszewska, M. Bitzan, and H. Schmidt. 1999. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34:229-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawano, K., M. Okada, T. Haga, K. Maeda, and Y. Goto. 2008. Relationship between pathogenicity for humans and stx genotype in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serotype O157. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein, E. J., J. R. Stapp, C. R. Clausen, D. R. Boster, J. G. Wells, X. Qin, D. L. Swerdlow, and P. I. Tarr. 2002. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in children with diarrhea: a prospective point-of-care study. J. Pediatr. 141:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leotta, G. A., E. S. Miliwebsky, I. Chinen, E. M. Espinosa, K. Azzopardi, S. M. Tennant, R. M. Robins-Browne, and M. Rivas. 2008. Characterisation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 strains isolated from humans in Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. BMC Microbiol. 8:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning, S. D., A. S. Motiwala, A. C. Springman, W. Qi, D. W. Lacher, L. M. Ouellette, J. M. Mladonicky, P. Somsel, J. T. Rudrik, S. E. Dietrich, W. Zhang, B. Swaminathan, D. Alland, and T. S. Whittam. 2008. Variation in virulence among clades of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with disease outbreaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:4868-4873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Brien, A. D., V. L. Tesh, A. Donohue-Rolfe, M. P. Jackson, S. Olsnes, K. Sandvig, A. A. Lindberg, and G. T. Keusch. 1992. Shiga toxin: biochemistry, genetics, mode of action, and role in pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 180:65-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochoa, T. J., and T. G. Cleary. 2003. Epidemiology and spectrum of disease of Escherichia coli O157. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 16:259-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orth, D., K. Grif, L. B. Zimmerhackl, and R. Würzner. 2008. Prevention and treatment of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infections in humans. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 6:101-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perera, L. P., L. R. Marques, and A. D. O'Brien. 1988. Isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to Shiga-like toxin II of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli and use of the monoclonal antibodies in a colony enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2127-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivas, M., E. Miliwebsky, I. Chinen, C. D. Roldan, L. Balbi, B. Garcia, G. Fiorilli, S. Sosa-Estani, J. Kincaid, J. Rangel, and P. M. Griffin. 2006. Characterization and epidemiologic subtyping of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from hemolytic uremic syndrome and diarrhea cases in Argentina. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:88-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauter, K. A., A. R. Melton-Celsa, K. Larkin, M. L. Troxell, A. D. O'Brien, and B. E. Magun. 2008. Mouse model of hemolytic-uremic syndrome caused by endotoxin-free Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2) and protection from lethal outcome by anti-Stx2 antibody. Infect. Immun. 76:4469-4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegler, R., and R. Oakes. 2005. Hemolytic uremic syndrome; pathogenesis, treatment, and outcome. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 17:200-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith, M. J., H. M. Carvalho, A. R. Melton-Celsa, and A. D. O'Brien. 2006. The 13C4 monoclonal antibody that neutralizes Shiga toxin type 1 (Stx1) recognizes three regions on the Stx1 B subunit and prevents Stx1 from binding to its eukaryotic receptor globotriaosylceramide. Infect. Immun. 74:6992-6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strockbine, N. A., L. R. Marques, R. K. Holmes, and A. D. O'Brien. 1985. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against Shiga-like toxin from Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 50:695-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarr, P. I., C. A. Gordon, and W. L. Chandler. 2005. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 365:1073-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trachtman, H., A. Cnaan, E. Christen, K. Gibbs, S. Zhao, D. W. Acheson, R. Weiss, F. J. Kaskel, A. Spitzer, and G. H. Hirschman. 2003. Effect of an oral Shiga toxin-binding agent on diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:1337-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzipori, S., A. Sheoran, D. Akiyoshi, A. Donohue-Rolfe, and H. Trachtman. 2004. Antibody therapy in the management of Shiga toxin-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:926-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]