Abstract

The previously reported CXCR4 antagonist KRH-1636 was a potent and selective inhibitor of CXCR4-using (X4) human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) but could not be further developed as an anti-HIV-1 agent because of its poor oral bioavailability. Newly developed KRH-3955 is a KRH-1636 derivative that is bioavailable when administered orally with much more potent anti-HIV-1 activity than AMD3100 and KRH-1636. The compound very potently inhibits the replication of X4 HIV-1, including clinical isolates in activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from different donors. It is also active against recombinant X4 HIV-1 containing resistance mutations in reverse transcriptase and protease and envelope with enfuvirtide resistance mutations. KRH-3955 inhibits both SDF-1α binding to CXCR4 and Ca2+ signaling through the receptor. KRH-3955 inhibits the binding of anti-CXCR4 monoclonal antibodies that recognize the first, second, or third extracellular loop of CXCR4. The compound shows an oral bioavailability of 25.6% in rats, and its oral administration blocks X4 HIV-1 replication in the human peripheral blood lymphocyte-severe combined immunodeficiency mouse system. Thus, KRH-3955 is a new promising agent for HIV-1 infection and AIDS.

The chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 serve as major coreceptors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), along with CD4 as a primary receptor for virus entry (2, 15, 18, 19). SDF-1α, which is a ligand for CXCR4, blocks the infection of CXCR4-utilizing X4 HIV-1 strains (7, 34). On the other hand, ligands for CCR5 such as RANTES inhibit CCR5-utilizing R5 HIV-1 (10). These findings made chemokines, chemokine derivatives, or small-molecule inhibitors of chemokine receptors attractive candidates as a new class of anti-HIV-1 agents. Many CCR5 antagonists have been developed as anti-HIV-1 drugs. These include TAK-779 (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company) (5), TAK-652 (6), TAK-220 (45), SCH-C (Schering-Plough) (43), SCH-D (vicriviroc) (42), GW873140 (aplaviroc; Ono Pharmaceutical/Glaxo Smith Kline) (28), and UK-427,857 (maraviroc; Pfizer Inc.) (17). Of these, maraviroc was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2007 for the treatment of R5 HIV-1 in treatment-experienced adult patients, combined with other antiretroviral treatment. Several classes of CXCR4 antagonists have also been reported. The bicyclam AMD3100 showed antivirus activity against many X4 and some R5X4 HIV strains in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) but not against R5 strains (16, 40). The pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity of this compound were also evaluated in humans (21, 22). T22, [Tyr-5,12, Lys-7]polyphemusin II, which is an 18-mer peptide derived from horseshoe crab blood cells, was reported to specifically inhibit X4 HIV-1 strains (30). Studies on the pharmacophore of T140 (a derivative of T22) led to the identification of cyclic pentapeptides (46).

In 2003, we reported that KRH-1636 is a potent and selective CXCR4 antagonist and inhibitor of X4 HIV-1 (23). Although the compound was absorbed efficiently from the rat duodenum, it has poor oral bioavailability. Continuous efforts to find more potent CXCR4 antagonists that are bioavailable when administered orally allowed us to develop KRH-3955 by a combination of chemical modification of the lead compound and biological assays. In this report, we describe the results of a preclinical evaluation of KRH-3955, including its in vitro anti-HIV-1 activity, its in vivo efficacy in the human peripheral blood lymphocyte (hu-PBL)-severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model, and its pharmacokinetics in rats in comparison with those of AMD3100.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

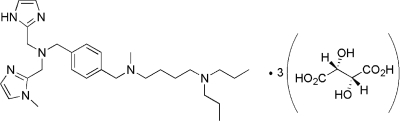

The synthesis and purification of KRH-3955, N,N-dipropyl-N′-[4-({[(1H-imidazol-2-yl)methyl][(1-methyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methyl]amino}methyl)benzyl] -N′-methylbutane-1,4-diamine tri-(2R,3R)-tartrate, were carried out by Kureha Corporation. The chemical structure of KRH-3955 is shown in Fig. 1. The CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 and zidovudine (AZT) were obtained from Sigma. Saquinavir was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, NIAID, Bethesda, MD. AMD070 and SCH-D were synthesized at Kureha Corporation.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of KRH-3955.

Cells.

Molt-4 no. 8 cells (24) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and antibiotics (50 ng/ml penicillin, 50 ng/ml streptomycin, and 100 ng/ml neomycin; Invitrogen), which is referred to as RPMI medium. Chemokine receptor-expressing human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells (ATCC CRL-1573) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (ATCC CCL-61) were maintained in minimal essential medium or F-12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (50 ng/ml penicillin, 50 ng/ml streptomycin, and 100 ng/ml neomycin). PBMCs from HIV-1-seronegative healthy donors were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient (Lymphosepal; IBL, Gunma, Japan) centrifugation (31) and grown in RPMI medium supplemented with recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) at 50 U/ml.

Viruses.

Viral stocks of HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-1JR-CSF, and HIV-189.6 were each produced in the 293T cell line by transfection with HIV-1 molecular clone plasmids pNL4-3 (1), pYK-JRCSF (25), and p89.6 (11), respectively, by the calcium phosphate method. The 50% tissue culture infective dose was determined by an end-point assay with PBMC cultures activated with immobilized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (33, 51). Subtype B HIV-1 primary isolates 92HT593, 92HT599 (N. Hasley), and 91US005 (B. Hahn) and AZT-resistant HIV-1 (A018) (D. D. Richman) (26) were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. These clinical isolates were propagated in the activated PBMCs prepared as described above.

Anti-HIV-1 assays.

Human PBMCs activated with immobilized anti-CD3 MAb (OKT-3; ATCC, Manassas, VA) in RPMI medium for 3 days were infected with various HIV-1 strains, including primary clinical isolates, at a multiplicity of infection of 0.001. After 3 h of adsorption, the cells were washed and cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with rhIL-2 (50 U/ml) in the presence or absence of the test compounds. Amounts of HIV-1 capsid (p24) antigen produced in the culture supernatants were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (ZeptoMetrix Corp., Buffalo, NY) 7 to 10 days after infection. The cytotoxicities of the compounds were tested on the basis of the viability and proliferation of the activated PBMCs, as determined with Cell Proliferation Kit II (XTT) from Roche (36).

Susceptibility of multidrug-resistant HIV-1 to CXCR4 antagonists was also measured by using recombinant viruses in a single replication cycle assay (9, 49). HIV-1 resistance test vectors (RTVs) contain the entire protease (PR) coding region and the reverse transcriptase (RT) coding region, from amino acid 1 to amino acid 305, amplified from patient plasma and a luciferase expression cassette inserted in the env region. The RTVs in this study contain patient-derived PR and RT sequences that possess mutations associated with resistance to PR, RT, or both PR and RT. Env-pseudotyped viruses were produced by cotransfecting 293 cells with RTV plasmids and expression vectors encoding the Env protein of well-characterized X4-tropic laboratory strain HXB2, NL4-3, or NL4-3 containing the Q40H enfuvirtide (T20) resistance mutation introduced by site-direct mutagenesis. The virus stocks were harvested 2 days after transfection and used to infect U87 CD4+ cells (kind gifted from N. Landau, NYU School of Medicine) expressing CXCR4 in 96-well plates, with serial dilutions of CXCR4 antagonists. Target cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured to assess virus replication in the presence and absence of inhibitors. Drug concentrations required to inhibit virus replication by 50% (IC50) were calculated.

Immunofluorescence.

Molt-4 cells or CXCR4-expressing HEK293 cells were treated with various concentrations of KRH-3955 or AMD3100 in RPMI medium or phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% NaN3 (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS] buffer). In washing experiments, cells were washed with RPMI medium or FACS buffer. The cells were Fc blocked with 2 mg/ml normal human immunoglobulin G (IgG) in FACS buffer and then stained directly with mouse MAbs 12G5-phycoerythrin (PE) and 44717-PE (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) or rat MAb A145-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and indirectly with MAb A80. The A145 and A80 MAbs were produced in ascitic fluid of BALB/c nude mice, and IgG fractions were obtained from ascitic fluid by gel filtration chromatography with Superdex G200 (Amersham Pharmacia). Goat anti-rat IgG (heavy and light chains) labeled with FITC was purchased from American Corlex (47). After washing, the cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) flow cytometer with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

DNA construction and transfection.

Chemokine receptor-expressing CHO cells were generated as reported previously (23). Human CXCR4 cDNA was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector. Mutations were introduced by using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing and transfected into 293 cells by using the Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) (48). Stable transfectants were selected in the presence of 400 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). The COOH-terminal intracellular domain of CXCR4 (residues 308 to 352) was deleted in all mutants and the wild type. This deletion has no influence on HIV-1 infection or on SDF-1α binding and signaling but abolishes ligand-induced endocytosis (3).

Ligand-binding assays.

Chemokine receptor-expressing CHO cells (5 ×106/0.2 ml per well) were cultured in a 24-well microtiter plate. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the culture medium was replaced with binding buffer (RPMI medium supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin). Binding reactions were performed on ice in the presence of 125I-labeled chemokines (final concentration of 100 pmol/liter; PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) and various concentrations of test compounds. After washing away of unbound ligand, cell-associated radioactivity was counted with a scintillation counter as described previously (23).

CXCR4-mediated Ca2+ signaling.

Fura2-acetoxymethyl ester (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan)-loaded CXCR4-expressing CHO cells were incubated in the absence or presence of various concentrations of KRH-3955 or AMD3100. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels in response to SDF-1α (1 μg/ml) were determined by using a fluorescence spectrophotometer as described previously (30).

Detection of KRH-3955 in blood after oral administration.

The plasma concentration-time profile of R-176211 (distilled water was used as a vehicle), the free form of KRH-3955, was examined after a single oral administration of KRH-3955 at a dose of 10 mg/kg or intravenous administration at a dose of 10 mg/kg to male Sprague-Dawley rats (CLEA, Kanagawa, Japan). R-176211 in plasma was measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by using WinNonlin Professional (ver. 3.1; Pharsight Co.).

Infection of hu-PBL-SCID mice.

Two groups of C.B-17 SCID mice (CLEA, Kanagawa, Japan) were administered a single dose of either KRH-3955 or tartrate (2% glucose solution was used as the vehicle) as a control orally (p.o.) and fed for 2 weeks. These mice were then engrafted with human PBMCs (1 × 107 cells/animal intraperitoneally [i.p.]) and after 1 day were infected i.p. with 1,000 infective units of X4 HIV-1NL4-3. IL-4 (2 μg per animal) was administrated i.p. on days 0 and 1 after PBMC engraftment to enhance X4 HIV-1 infection. After 7 days, human lymphocytes were collected from the peritoneal cavities and spleens of the infected mice and cultured in vitro for 4 days in RPMI medium supplemented with 20 U/ml rhIL-2. HIV-1 infection was monitored by measuring p24 levels in the culture supernatant. We used a selected donor whose PBMCs could be engrafted at an efficiency of >80% in C.B-17 SCID mice. Usually, 5 × 105 to 10 × 105 human CD4+ T cells can be recovered from each hu-PBL-SCID mouse. Mice with no or low recovery of human CD4+ T cells at the time of analysis were omitted. For ex vivo cultures, we used a quarter of the cells recovered from a mouse. The protocols for the care and use of the hu-PBL-SCID mice were approved by the Committee on Animal Research of the University of the Ryukyus before initiation of the present study.

RESULTS

Anti-HIV-1 activities of KRH-3955 in activated PBMCs.

The inhibitory activity of KRH-3955 against X4 HIV-1 (NL4-3), R5X4 HIV-1 (89.6), and R5 HIV-1 (JR-CSF) was examined in activated human PBMCs from two different donors. KRH-3955 inhibited the replication of both X4 and R5X4 HIV-1 in activated PBMCs with 50% effective concentrations (EC50) of 0.3 to 1.0 nM but did not affect R5 HIV-1 replication, even at concentration of up to 200 nM (Table 1). In contrast, the CCR5 antagonist SCH-D (vicriviroc) inhibited R5 HIV-1 replication but inhibited neither X4 nor R5X4 HIV-1 replication (Table 1). The anti-HIV activity of KRH-3955 against the 89.6 virus from donor B was not determined because the virus did not replicate enough for calculation of the anti-HIV activity of KRH-3955 and other drugs. Notably, the anti-HIV-1 activity of KRH-3955 was much higher than that of AMD3100, a well-known X4 HIV-1 inhibitor, or AMD070, the other X4 inhibitor that is bioavailable when administered orally. KRH-3955 also inhibited the replication of clinical isolates of X4 HIV-1 (92HT599) and R5X4 HIV-1 (92HT593) with EC50 ranging from 4.0 to 4.2 nM (data not shown). Although both KRH-3955 and AMD3100 were effective against at least some R5X4 HIV-1 strains in activated PBMCs, neither KRH-3955 nor AMD3100 inhibited the infection of CD4/CCR5 cells by R5 or R5X4 HIV-1, even at a concentration of 1,660 nM (data not shown). Importantly, the 50% cytotoxic concentration of KRH-3955 in activated PBMCs (donor A) was 57 μM, giving a high therapeutic index (51,818) in the case of NL4-3 infection, which was higher than that of AZT (8,000 in the case of donor A). These results indicate that the compound is a selective inhibitor of HIV-1 that can utilize CXCR4 as a coreceptor. Since a CXCR4 antagonist should be used in combination with a CCR5 antagonist in a clinical setting, we next examined whether the combined use of both antagonists efficiently blocks mixed infection with X4 and R5 HIV-1. Combination of KRH-3955 and SCH-D at 4 plus 4 nM and 20 plus 20 nM blocked the replication of 50:50 mixtures of NL4-3 and JR-CSF by 91 and 96%, respectively (data not shown). Thus, KRH-3955 is a highly potent and selective inhibitor of X4 HIV-1.

TABLE 1.

Anti-HIV-1 activity of KRH-3955 in activated PBMCsa

| Virus | Donor | EC50 (nM)b

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRH-3955 | AMD3100 | AMD070 | SCH-D | AZT | SQV | ||

| NL4-3 | A | 1.1 | 41 | 35 | >1,000 | 11 | 9.0 |

| X4 | B | 0.33 | 15 | 15 | >1,000 | 8.0 | 29 |

| 89.6 | A | 0.38 | 44 | 55 | >1,000 | 7.4 | 9.9 |

| R5X4 | B | NDc | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| JR-CSF | A | >200 | >200 | >200 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 2.6 |

| R5 | B | >200 | >200 | >200 | 1.2 | 6.2 | 8.0 |

| A018H (X4) (pre-AZT) | C | 1.4 | 38 | ND | ND | 1.9 | ND |

| A018G (X4) (post-AZT) | C | 1.3 | 32 | ND | ND | 87,000 | ND |

PBMCs from two different donors were used in each assay. Anti-HIV-1 activity was determined by measuring the p24 antigen level in culture supernatants.

Assays were carried out in triplicate wells. The average of two to four experiments is shown.

ND, not determined.

Anti-HIV-1 activities of KRH-3955 in activated PBMCs from different donors.

It has been observed that the anti-HIV-1 activity of compounds in PBMCs varies from donor to donor. Therefore, the anti-HIV-1 activity of KRH-3955 against X4 HIV-1 was examined in activated PBMCs from eight different donors. The levels of p24 antigen in NL4-3-infected cultures ranged from 17 to 120 ng/ml (Table 2). KRH-3955 inhibited the replication of NL4-3 with EC50 ranging from 0.23 to 1.3 nM and with EC90 ranging from 2.7 to 3.5 nM (Table 2), demonstrating that the anti-HIV-1 activity of KRH-3955 was independent of the PBMC donor.

TABLE 2.

Anti-HIV-1 activity of KRH-3955 against NL4-3 infection of PBMCs from eight different donors

| Donor | p24 level (ng/ml) | EC50 (nM) | EC90 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | 1.30 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 25 | 1.20 | 3.2 |

| 3 | 17 | 1.20 | 3.3 |

| 4 | 40 | 0.70 | 2.9 |

| 5 | 120 | 0.77 | 2.9 |

| 6 | 58 | 1.50 | 3.5 |

| 7 | 49 | 0.23 | 2.7 |

| 8 | 53 | 1.00 | 3.0 |

| Mean ± SD | 49 ± 32 | 0.99 ± 0.40 | 3.1 ± 0.30 |

Anti-HIV-1 activities of KRH-3955 against drug-resistant HIV-1 strains.

To further assess the efficacy of KRH-3955, we used a single-cycle assay to evaluate the activity of KRH-3955 against a panel of recombinant viruses that express an X4-tropic envelope protein (HXB2) but contain PR and RT sequences containing a wide variety of mutations associated with resistance to PR inhibitors (PIs), nucleoside RT inhibitors (NRTIs), and non-NRTIs (NNRTIs). This assessment was also performed with recombinant viruses that express an X4-tropic envelope protein (NL4-3) that contains the Q40H mutation and displays resistance to T20 (an entry inhibitor). The results of these experiments demonstrate that both KRH-3955 and AMD3100 inhibited the infection of CD4/CXCR4 cells by these recombinant drug-resistant viruses, including viruses resistant to PIs, NRTIs, or NNRTIs; multidrug-resistant viruses; and T20-resistant viruses (Table 3). We also observed that KRH-3955 inhibited the replication of A018G, a highly AZT-resistant strain, in activated PBMCs with an EC50 of 1.3 nM (Table 1).

TABLE 3.

KRH-3955 susceptibilities of drug-resistant virusesa

| Virusb | IC50 (nM)c

|

|

|---|---|---|

| KRH-3955 | AMD3100 | |

| NL4-3 | 0.50 | 4.6 |

| HXB2 | 0.60 | 6.2 |

| NRTI-Res (HXB2-env) | 0.60 | 9.0 |

| NNRTI-Res (HXB2-env) | 0.80 | 7.0 |

| PI-Res (HXB2-env) | 0.70 | 9.2 |

| MDR (HXB2-env) | 0.70 | 5.3 |

| T20-Res (NL4-3-env) | 0.40 | 2.3 |

Susceptibility of drug-resistant HIV-1 was measured by using a single-cycle recombinant virus assay (see Materials and Methods).

The pseudoviruses containing X4-tropic envelope (HXB2 or NL4-3) and patient-derived PR and RT sequences containing mutations associated with resistance to PR (PI-Res), RT (NRTI-Res or NNRTI-Res), or both (MDR) (the mutations are not shown). T20-Res contains a site-directed mutation (Q40H) in the NL4-3 envelope.

IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration of CXCR4 antagonists.

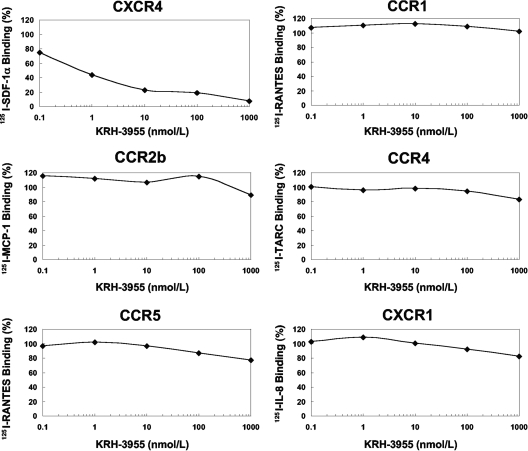

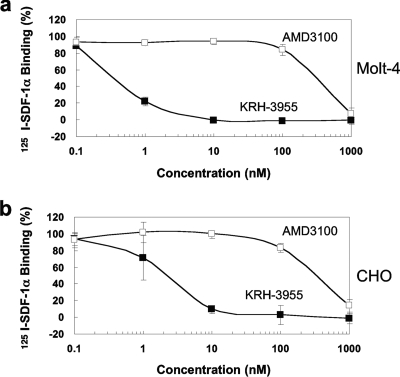

KRH-3955 selectively inhibits ligand binding to CXCR4.

To investigate whether KRH-3955 specifically blocks ligand binding to CXCR4, the inhibitory effect of the compound on chemokine binding to CHO cells expressing CXCR4, CXCR1, CCR2b, CCR3, CCR4, or CCR5 was determined. KRH-3955 efficiently inhibited SDF-1α binding to CXCR4 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2 and 3b), and the IC50 for SDF-1α binding was 0.61 nM, which is similar to its EC50 against HIV-1. Similar results were obtained when we used a Molt-4 T cell line as the CXCR4-expressing target cell (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, the inhibitory activity of AMD3100 against SDF-1α binding was much weaker than its anti-HIV-1 activity (Fig. 3), suggesting that the binding sites of these two compounds are different. In contrast, the compound did not affect the binding of 125I-labeled SDF-1α, 125I-labeled RANTES, 125I-labeled MCP-1, 125I-labeled TARC, 125I-labeled RANTES, or 125I-labeled IL-8 to CXCR4, CCR1, CCR2b, CCR4, CCR5, or CXCR1, respectively (Fig. 2). Thus, KRH-3955 selectively blocks the binding of SDF-1α to CXCR4.

FIG. 2.

Inhibitory effects of KRH-3955 on chemokine binding to CXCR4-, CCR1-, CCR2b-, CCR4-, CCR5-, or CXCR1-expressing CHO cells. Chemokine receptor-expressing CHO cells were incubated with various concentrations of KRH-3955 in binding buffer containing 125I-labeled chemokine. Binding reactions were performed on ice and were terminated by washing out the unbound ligand. Cell-associated radioactivity was measured with a scintillation counter. Percent binding was calculated as 100 × [(binding with inhibitor − nonspecific binding)/(binding without inhibitor − nonspecific binding)]. The data represent the means in duplicate wells in a single experiment.

FIG. 3.

Concentration-dependent inhibition by KRH-3955 of SDF-1α binding to (a) Molt-4 and (b) CXCR4-expressing CHO cells. CXCR4-expressing CHO cells were incubated with various concentrations of KRH-3955 (▪) or AMD3100 (□) in binding buffer containing 125I-labeled SDF-1α. Binding reactions were performed, and percent binding was calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The data represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

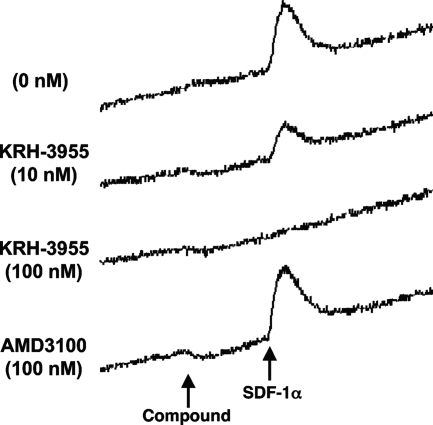

KRH-3955 exhibits inhibition of Ca2+ signaling through CXCR4.

We next examined whether KRH-3955 acts as an agonist or antagonist of CXCR4 by using CXCR4-expressing CHO cells. The addition of KRH-3955 inhibited the SDF-1α-induced increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration in a dose-dependent manner, whereas 100 nM AMD3100 did not affect Ca2+ mobilization (Fig. 4). KRH-3955 itself did not affect Ca2+ mobilization at up to 1 μM (data not shown). We performed the Ca2+ mobilization assay with human PBMCs but could not detect an SDF-1α-induced Ca2+ signal mainly due to low expression of CXCR4 (data not shown). Thus, KRH-3955 inhibits Ca2+ signaling through CXCR4.

FIG. 4.

Inhibitory effects of KRH-3955 on SDF-1α-induced Ca2+ mobilization in CXCR4-expressing CHO cells. Fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester-loaded CXCR4-expressing CHO cells were incubated in the presence or absence of various concentrations of KRH-3955 or AMD3100. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels in response to SDF-1α (1 μg/ml) were determined with a fluorescence spectrophotometer. The data show representative data for two independent experiments.

Effect of KRH-3955 on anti-CXCR4 antibody binding to CXCR4-expressing cells.

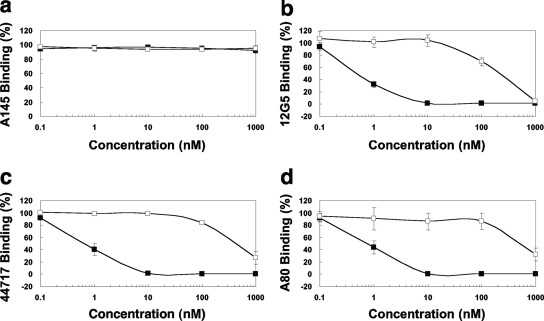

To localize the binding site(s) of KRH-3955, the effects of KRH-3955 and AMD3100 on the binding of four types of anti-CXCR4 MAbs were first examined. We used MAbs A145, 12G5, 44717, and A80, which are specific for the N terminus, extracellular loop 1 (ECL1) and ECL2, ECL2, and ECL3, respectively. Neither KRH-3955 nor AMD3100 inhibited A145 binding to CXCR4-expressing Molt-4 cells (Fig. 5). Both compounds inhibited the binding of MAbs 12G5, 44717, and A80 to Molt-4 cells in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibitory activity of KRH-3955 is similar to its anti-HIV-1 activity, whereas the inhibitory activity of AMD3100 is much weaker than its anti-HIV-1 activity. Similar data were obtained when activated human PBMCs were used as target cells (data not shown). KRH-3955 itself did not induce internalization of CXCR4 at concentrations of up to 1 μM (data not shown), as KRH-1636 did (23). These results suggest that the binding sites of KRH-3955 are located in a region composed of all three ECLs of CXCR4.

FIG. 5.

Effect of KRH-3955 on the binding of four different MAbs to the CXCR4 receptor. Molt-4 cells were incubated with various concentrations of KRH-3955 (▪) or AMD3100 (□). The cells were stained directly with MAbs 12G5 (recognizes ECL1 and ECL2 of CXCR4)-PE, 44717 (recognizes ECL2 of CXCR4)-PE, and A145 (recognizes the N terminus of CXCR4)-FITC or indirectly with MAb A80 (recognizes ECL3 of CXCR4). The mean fluorescence of the stained cells was analyzed with a FACScalibur flow cytometer. Percent binding was calculated with the equation described in the legend to Fig. 2. The data represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

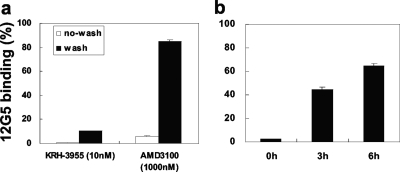

Long-lasting inhibitory effects of KRH-3955 on the binding of MAb 12G5.

The inhibitory effect of KRH-3955 on the binding of MAb 12G5 was examined with or without washing of the compound from the cells. Molt-4 cells were treated with 10 nM KRH-3955 or 1,000 nM AMD3100 for 15 min. With or without washing, the cells were stained with MAb 12G5-PE and the amount of bound antibody was analyzed by flow cytometry. KRH-3955 strongly inhibited MAb 12G5 binding to Molt-4 cells irrespectively of washing (Fig. 6a). In contrast, AMD3100 efficiently inhibited MAb 12G5 binding without washing away of the compound but lost its inhibitory activity after washing away of the compound (Fig. 6a). The long-lasting inhibitory effect of KRH-3955 on the binding of MAb 12G5 was further tested. Molt-4 cells were preincubated with or without KRH-3955 at 10 nM. The compound was washed away, and the cells were further incubated at 37°C in compound-free growth medium. At 0, 3, and 6 h after compound removal, the cells were stained with MAb 12G5-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry. Even at 6 h after washing away of the compound, KRH-3955 inhibited MAb 12G5 binding by approximately 40% (Fig. 6b). These results suggest that KRH-3955 has a strong binding affinity for CXCR4 and a slow dissociation rate, although competition assays with the two molecules (KRH-3955 versus MAb 12G5 with radioactive, nonradioactive, or different labeling) are necessary to provide definitive conclusions.

FIG. 6.

Long-lasting inhibitory effects of KRH-3955 on the binding of MAb 12G5. (a) Molt-4 cells were treated with 10 nM KRH-3955 or 1,000 nM AMD3100 for 15 min. With (▪) or without (□) washing, the cells were staining with MAb 12G5-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry. (b) Long-lasting inhibitory effect of KRH-3955 on the binding of MAb 12G5. Molt-4 cells were preincubated with or without KRH-3955 at 10 nM. The compound was washed away, and the cells were further incubated at 37°C in compound-free RPMI medium. At 0, 3, and 6 h after removal of the compound, the cells were staining with MAb 12G5-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry. The data represent the means of triplicate wells in a single experiment.

Inhibition of MAb 12G5 binding to CXCR4 mutants by KRH-3955.

The effects of different CXCR4 mutations on the inhibitory activity of KRH-3955 against MAb 12G5 binding to CXCR4 were examined. HEK293-CXCR4 transfectants were preincubated with various concentrations of KRH-3955 and AMD3100, after which the compound was washed away. The binding of PE-conjugated MAb 12G5 was measured by flow cytometry. As reported previously, AMD3100 substantially lost its blocking activity against MAb 12G5 binding for D171A (TM4), D262A (TM6), and E288A/L290A (TM7) mutants, as shown by previous reports (Table 4) (20, 37, 38). In contrast, the blocking activity of KRH-3955 against MAb 12G5 binding was not affected by the above mutations. In contrast, the H281A (ECL3) mutant displayed decreased inhibition of MAb 12G5 binding by KRH-3955 (Table 4). These data further support the hypothesis that the CXCR4 interaction sites of KRH-3955 are different from those of AMD3100.

TABLE 4.

Affinity of KRH-3955 and AMD3100 for wild-type CXCR4 and various mutant forms of CXCR4a

| CXCR4 (location) | KRH-3955

|

AMD3100

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | IC90 | IC50 | IC90 | |

| Wild type | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 289.1 ± 25.5 | 971.1 ± 31.2 |

| V99A (ECL1) | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 258.5 ± 25.9 | >1,000 |

| V112A (TM3) | 2.2 ± 0.2 | >10 | 196.6 ± 28.5 | 821.3 ± 15.4 |

| H113A (TM3) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 296.4 ± 112.2 | >1,000 |

| D171A (TM4) | 3.2 ± 0.1 | >10 | >1,000 | >1,000 |

| D181A (ECL2) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 143.7 ± 29.3 | 795.6 ± 79.9 |

| H203A (TM5) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 259.0 ± 11.5 | 860.6 ± 22.4 |

| D262A (TM6) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | >1,000 | >1,000 |

| E275A (ECL3) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 235.6 ± 30.2 | 930.2 ± 26.1 |

| E277A (ECL3) | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 0.1 | 469.5 ± 19.2 | >1,000 |

| V280A (ECL3) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 175.3 ± 10.3 | 821.2 ± 47.3 |

| H281A (ECL3) | 14.1 ± 5.2 | 248.3 ± 74.9 | 72.7 ± 42.9 | 572.2 ± 118.1 |

| W283A (ECL3) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.2 | 300.2 ± 10.5 | >1,000 |

| I284A (TM7) | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 0.5 | 265.8 ± 20.8 | >1,000 |

| E288A/L290A (TM7) | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | >1,000 | >1,000 |

The data shown, which represent means ± SDs (n = 3) of nanomolar concentrations, were obtained from competition binding on HEK293 cells expressing the wild-type or mutant CXCR4 receptors with MAb 12G5.

Pharmacokinetic studies of KRH-3955 in rats.

In pharmacokinetics studies, KRH-3955 was orally or intravenously administrated to Sprague-Dawley rats at a dose of 10 mg/kg. The plasma concentration of R-176211, the free form of KRH-3955, was monitored by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. In these studies, KRH-3955 was found to be well absorbed and the absolute oral bioavailability in rats was calculated to be 25.6% based on the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (Table 5). However, KRH-3955 also showed a long elimination half-life after single-dose administration to rats, suggesting long-term accumulation of the compound in tissues (Table 5). KRH-3955 was found to be stable in human hepatic microsomes, and no significant inhibition of CYP450 liver enzymes by this compound was observed (data not shown). Thus, orally administered KRH-3955 is bioavailable in rats.

TABLE 5.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of KRH-3955 after single oral administration in ratsa

| Parameter | Value when given i.v. or p.o. at 10 mg/kg |

|---|---|

| Bioavailability (%)b | 25.6 |

| I.v. half-life (h) | 99.0 ± 13.1 |

| I.v. CL (liters/h/kg)c | 3.9 ± 0.07 |

| V1 (ss) (liters/kg)d | 374.0 ± 14 |

| P.o. Cmax (ng/ml)e | 86.3 ± 23.6 |

| Tmax (h)f | 2.3 ± 1.53 |

| P.o. AUC0-336 (ng · h/ml)g | 325.0 ± 38 |

The data shown are means ± SDs (n = 3).

Bioavailability = (AUCoral/AUCi.v.) × (dosei.v./doseoral) × 100.

CL, clearance.

V1 (ss), volume of distribution in central compartment at steady state.

Cmax, maximum concentration of drug in serum.

Tmax, time to maximum concentration of drug in serum.

AUC0-336, area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to 336 h.

KRH-3955 efficiently suppresses X4 HIV-1 infection in hu-PBL-SCID mice.

We then examined whether KRH-3955 can interfere with X4 HIV-1 infection in vivo by using hu-PBL-SCID mice. Mice were administrated a single dose (10 mg/kg) of either KRH-3955 or tartrate (as a control) p.o. and fed for 2 weeks. These mice were then engrafted with human PBMCs, and after 1 day, these “humanized” mice were infected with infectious X4 HIV-1 (NL4-3). After 7 days, human lymphocytes harvested from the peritoneal cavities and spleens of the infected mice were cultured for 4 days in vitro in the presence of rhIL-2 in order to determine the level of HIV-1 infection by the p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The maximum concentration of KRH-3955 in blood after p.o. administration was estimated to be 100 nM (data now shown). Under these conditions, four of five mock-treated mice were infected whereas only one of five mice treated with KRH-3955 was infected (Table 6). The one infected mouse in the KRH-3955-treated group (no. 5) showed low levels of p24 production. These results indicate that single-dose p.o. administration of KRH-3955 was very effective in protecting against X4 HIV-1 infection in an in vivo mouse model.

TABLE 6.

Inhibition of infection of hu-PBL-SCID mice with X4 HIV-1 by KRH-3955a

| Group and mouse no. | p24 produced (pg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Control | |

| 1 | 747 |

| 2 | 10,263 |

| 3 | <5 |

| 4 | 5,821 |

| 5 | 1,902 |

| KRH-3955 | |

| 6 | <5 |

| 7 | <5 |

| 8 | <5 |

| 9 | <5 |

| 10 | 36 |

Two groups of C.B-17 SCID mice (n = 5) were administrated a single dose of either KRH-3955 or tartrate (as a control) p.o. and fed for 2 weeks. These mice were then engrafted with human PBMCs (1 × 107 per animal i.p.), and after 1 day, these “humanized” mice were infected with 1,000 infective units of X4 HIV-1NL4-3. IL-4 (2 mg per animal) was administrated i.p. on days 0 and 1 after PBMC engraftment to enhance X4 HIV-1 infection. After 7 days, human lymphocytes were harvested from the infected mice and cultured in vitro for 4 days in medium containing 20 U/ml IL-2. HIV-1 infection was monitored by measuring p24 levels. Means from duplicate determinations are shown. <5, below detection level.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we clearly demonstrate that KRH-3955, a KRH-1636 derivative that is bioavailable when administered orally, is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 infection both in vitro and in vivo. KRH-3955 selectively inhibited X4 HIV-1 strains, including clinical isolates, as we have previously shown with KRH-1636. Furthermore, KRH-3955 is approximately 40 times more potent than KRH-1636 in its anti-HIV-1 activity in activated PBMCs (Table 1). The anti-HIV-1 activity of KRH-3955 was independent of the PBMC donor (Table 2). KRH-3955 also inhibited the infectivity of recombinant viruses resistant to NRTIs, NNRTIs, PIs, and T20 (Table 3). Pharmacokinetic studies of KRH-3955 indicated that the compound is bioavailable in rats when administered orally (Table 5). In addition, oral administration of the compound efficiently inhibited the replication of X4 HIV-1 in the hu-PBL-SCID mouse model (Table 6). Although we could show that KRH-3955 is a potent inhibitor of subtype B HIV-1 isolates, we need to examine the efficacy of this compound against non-subtype B HIV-1 isolates because of the global nature of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the regional diversity of HIV-1 subtypes.

R5 HIV-1 is isolated predominantly during the acute and asymptomatic stage (12) and is also believed to be important for virus transmission between individuals. In contrast, X4 HIV-1 strains emerge in approximately 50% of infected individuals and their emergence is associated with a rapid CD4+ T-cell decline and disease progression (35, 50). One recent report also indicated that detection of X4 HIV-1 at baseline independently predicted disease progression (13), although it is still not known whether the emergence of X4 HIV-1 is a cause or outcome of disease progression. These findings strongly support the need for highly potent CXCR4 inhibitors that are bioavailable when administered orally such as KRH-3955.

Inhibition of ligand binding to chemokine receptors by KRH-3955 was specific for CXCR4 (Fig. 2), as we observed previously for KRH-1636. This specific inhibition of SDF-1α binding to CXCR4 by KRH-3955 is absolutely necessary for developing an anti-HIV agent to avoid immune dysregulation by nonspecific inhibition of binding by other chemokines. It is of note that the inhibitory activity of the compound against SDF-1α binding is similar to that against HIV-1 infection, which is different from that of control compound AMD3100. Where on the CXCR4 molecule is the binding site(s) of KRH-3955? Experiments to examine the effect of KRH-3955 on the binding of several anti-CXCR4 MAbs suggest that the binding sites of KRH-3955 are located in all three ECLs of CXCR4 (Fig. 5). To further define the binding site(s) of KRH-3955, we examined the effects of CXCR4 point mutations on the inhibitory activity of KRH-3955 against MAb 12G5 binding to the receptor. AMD3100 was used as a control. The inhibitory activity of AMD3100 against MAb 12G5 binding to the receptor was greatly reduced by the mutations D171A (TM4), D262A (TM6), and E288A/L290A (TM7), as reported previously (Table 4) (20, 37, 38). Of note, these mutations also affect SDF-1α binding and/or CXCR4 coreceptor activity (8). Unexpectedly, none of these three mutations affected the inhibition of MAb 12G5 binding by KRH-3955 (Table 4). Only the H281A (ECL3) mutant showed decreased inhibition of MAb 12G5 binding by KRH-3955 (Table 4). Interestingly, the same mutant modestly increased the blocking activity of AMD3100 against MAb 12G5 binding. In addition, the H281A mutation markedly impaired inhibition of MAb 12G5 binding by AMD3465, one of the prototype monocyclams (37). Further experiments with different CXCR4 mutants are necessary to identify the exact site(s) on CXCR4 targeted by this compound.

Pharmacological tests of KRH-3955 were performed with rats, and the compound was found to be bioavailable when administered orally (Table 5), which is favorable for anti-HIV drugs. However, the compound also indicated a long half-life after single-dose administration to rats, suggesting long-term accumulation of the compound in tissues, which can be either advantageous in terms of inhibiting HIV-1 infection in hu-PBL-SCID mice (Table 6) or disadvantageous in terms of toxicity. Further studies are ongoing to determine the safety and pharmacokinetics of the compound in other animals such as dogs and monkeys. To evaluate the in vivo efficacy of KRH-3955, we used the hu-PBL-SCID mouse model and showed that oral administration of the compound strongly protected against X4 HIV-1 infection in this model system (Table 6). To achieve substantial replication of X4 HIV-1 in this system, recombinant IL-4 was added after human PBMC engraftment as described previously (23). Notably, KRH-3955 was administered only once 2 weeks before PBMC engraftment and was effective enough to block X4 HIV-1 infection, suggesting that the compound can be used as a preexposure prophylaxis agent to prevent HIV infection. This long-lasting antiviral effect of KRH-3955 can be partly explained by the strong affinity of the compound for CXCR4 (Fig. 6) and long-term accumulation of the compound in tissues.

In terms of safety of anti-HIV drugs, CCR5 antagonists are considered to be relatively safe because of the lack of obvious health problems in individuals homozygous for the CCR5 delta32 allele (27, 39). Indeed, maraviroc, a CCR5 antagonist, was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2007. In contrast, CXCR4 antagonists, which inhibit SDF-1α-CXCR4 interactions, may cause severe adverse effects because knocking out either the SDF-1α or the CXCR4 gene in mice causes marked defects such as abnormal hematopoiesis and cardiogenesis, in addition to vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract (32, 44, 52). However, no severe side effects have been reported for either AMD3100, a well-characterized CXCR4 antagonist, or AMD070, an oral CXCR4 antagonist, in human volunteers and/or HIV-infected patients. Milder side effects, including gastrointestinal symptoms and paresthesias, were common at higher doses of AMD3100. These results indicate the feasibility of using CXCR4 antagonists as anti-HIV-1 drugs in a clinical setting (21, 22, 41).

Besides the physiological roles mentioned above, the CXCR4-SDF-1 axis is also involved in various diseases such as cancer metastasis, leukemia cell progression, rheumatoid arthritis, and pulmonary fibrosis. CXCR4 antagonists such as AMD3100 and T140 have demonstrated activity in treating such CXCR4-mediated diseases (14, 46). In addition, AMD3100 is considered to be a stem cell mobilizer for transplantation in patients with cancers such as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Recently, AMD3100 has been shown to increase T-cell trafficking in the central nervous system, leading to significant improvement in the survival of West Nile virus encephalitis (29). Given its highly potent and selective inhibition of SDF-1-CXCR4 interaction and its bioavailability when administered orally, it is important to address whether KRH-3955 can also be used for such clinical applications.

One important issue to be addressed is whether HIV-1 strains resistant to other CXCR4 antagonists show cross-resistance to KRH-3955. In our preliminary studies, AMD3100-resistant HIV-1 (kindly provided by M. Baba, Kagoshima University) (4) showed ∼19-fold resistance to KRH-3955 compared with parental NL4-3, whereas the resistant virus showed ∼40-fold resistance to both AMD3100 and AMD070 in MT-4 cells (data not shown). Interestingly, the AMD3100-resistant HIV-1 strain was relatively sensitive to T22, another prototype CXCR4 antagonist. Thus, KRH-3955 target sites on CXCR4 seem to partially overlap those of AMD3100, although experiments with CXCR4 mutants do not support this idea. It is important to establish KRH-3955-resistant mutants and investigate whether they also show cross-resistance to other CXCR4 antagonists. Long-term culture experiments with PM1/CCR5 cells that express both CXCR4 and CCR5 infected with X4 HIV-1 in the presence of KRH-3955 are in progress.

In conclusion, KRH-3955 is a small-molecule antagonist of the CXCR4 receptor that is bioavailable when administered orally. The compound potently and selectively inhibits X4 HIV-1 infection both in vitro and in vivo. Thus, KRH-3955 is a promising antiviral agent for HIV-1 infection and should be evaluated for its clinical efficacy and safety in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Freed for his critical review of the manuscript. We thank Y. Koyanagi, and R. Collman for generously providing plasmids and thank M. Baba for AMD3100-resistant HIV-1.

The following reagents were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program: saquinavir, subtype B HIV-1 primary isolates 92HT593, 92HT599 (N. Hasley), and 91US005 (B. Hahn) and AZT-resistant HIV-1 A018 (D. Richman). This work was supported in part by a grant for Research on HIV/AIDS from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhatib, G., C. Combadiere, C. C. Broder, Y. Feng, P. E. Kennedy, P. M. Murphy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 272:1955-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amara, A., S. L. Gall, O. Schwartz, J. Salamero, M. Montes, P. Loetscher, M. Baggiolini, J. L. Virelizier, and F. Arenzana-Seisdedos. 1997. HIV coreceptor downregulation as antiviral principle: SDF-1α-dependent internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 contributes to inhibition of HIV replication. J. Exp. Med. 186:139-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arakaki, R., H. Tamamura, M. Premanathan, K. Kanbara, S. Ramanan, K. Mochizuki, M. Baba, N. Fujii, and H. Nakashima. 1999. T134, a small-molecule CXCR4 inhibitor, has no cross-drug resistance with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist with a different structure. J. Virol. 73:1719-1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba, M., O. Nishimura, N. Kanzaki, M. Okamoto, H. Sawada, Y. Iizawa, M. Shiraishi, Y. Aramaki, K. Okonogi, Y. Ogawa, K. Meguro, and M. Fujino. 1999. A small-molecule, nonpeptide CCR5 antagonist with highly potent and selective anti-HIV-1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5698-5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baba, M., K. Takashima, H. Miyake, N. Kanzaki, K. Teshima, X. Wang, M. Shiraishi, and Y. Iizawa. 2005. TAK-652 inhibits CCR5-mediated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in vitro and has favorable pharmacokinetics in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4584-4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleul, C. C., M. Farzan, H. Choe, C. Parolin, I. Clark-Lewis, J. Sodroski, and T. A. Springer. 1996. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature 382:829-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brelot, A., N. Heveker, M. Montes, and M. Alizon. 2000. Identification of residues of CXCR4 critical for human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor and chemokine receptor activities. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23736-23744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coakley, E., C. J. Petropoulos, and J. M. Whitcomb. 2005. Assessing chemokine co-receptor usage in HIV. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocchi, F., A. L. DeVico, D. A. Garzino, S. K. Arya, R. C. Gallo, and P. Lusso. 1995. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science 270:1811-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collman, R., J. W. Balliet, S. A. Gregory, H. Friedman, D. L. Kolson, N. Nathanson, and A. Srinivasan. 1992. An infectious molecular clone of an unusual macrophage-tropic and highly cytopathic strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 66:7517-7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor, R. I., K. E. Sheridan, D. Ceradini, S. Choe, and N. R. Landau. 1997. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Exp. Med. 185:621-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daar, E. S., K. L. Kesler, C. J. Petropoulos, W. Huang, M. Bates, A. E. Lail, E. P. Coakley, E. D. Gomperts, and S. M. Donfield. 2007. Baseline HIV type 1 coreceptor tropism predicts disease progression. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Clercq, E. 2005. Potential clinical applications of the CXCR4 antagonist bicyclam AMD3100. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 5:805-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, M. P. Di, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donzella, G. A., D. Schols, S. W. Lin, J. A. Este, K. A. Nagashima, P. J. Maddon, G. P. Allaway, T. P. Sakmar, G. Henson, E. De Clercq, and J. P. Moore. 1998. AMD3100, a small molecule inhibitor of HIV-1 entry via the CXCR4 co-receptor. Nat. Med. 4:72-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorr, P., M. Westby, S. Dobbs, P. Griffin, B. Irvine, M. Macartney, J. Mori, G. Rickett, C. Smith-Burchnell, C. Napier, R. Webster, D. Armour, D. Price, B. Stammen, A. Wood, and M. Perros. 2005. Maraviroc (UK-427,857), a potent, orally bioavailable, and selective small-molecule inhibitor of chemokine receptor CCR5 with broad-spectrum anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4721-4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dragic, T., V. Litwin, G. P. Allaway, S. R. Martin, Y. Huang, K. A. Nagashima, C. Cayanan, P. J. Maddon, R. A. Koup, J. P. Moore, and W. A. Paxton. 1996. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature 381:667-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng, Y., C. C. Broder, P. E. Kennedy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272:872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerlach, L. O., R. T. Skerlj, G. J. Bridger, and T. W. Schwartz. 2001. Molecular interactions of cyclam and bicyclam non-peptide antagonists with the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276:14153-14160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrix, C. W., A. C. Collier, M. M. Lederman, D. Schols, R. B. Pollard, S. Brown, J. B. Jackson, R. W. Coombs, M. J. Glesby, C. W. Flexner, G. J. Bridger, K. Badel, R. T. MacFarland, G. W. Henson, and G. Calandra. 2004. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of AMD3100, a selective CXCR4 receptor inhibitor, in HIV-1 infection. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 37:1253-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendrix, C. W., C. Flexner, R. T. MacFarland, C. Giandomenico, E. J. Fuchs, E. Redpath, G. Bridger, and G. W. Henson. 2000. Pharmacokinetics and safety of AMD-3100, a novel antagonist of the CXCR-4 chemokine receptor, in human volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1667-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichiyama, K., S. Yokoyama-Kumakura, Y. Tanaka, R. Tanaka, K. Hirose, K. Bannai, T. Edamatsu, M. Yanaka, Y. Niitani, N. Miyano-Kurosaki, H. Takaku, Y. Koyanagi, and N. Yamamoto. 2003. A duodenally absorbable CXC chemokine receptor 4 antagonist, KRH-1636, exhibits a potent and selective anti-HIV-1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4185-4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kikukawa, R., Y. Koyanagi, S. Harada, N. Kobayashi, M. Hatanaka, and N. Yamamoto. 1986. Differential susceptibility to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome retrovirus in cloned cells of human leukemic T-cell line Molt-4. J. Virol. 57:1159-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koyanagi, Y., S. Miles, R. T. Mitsuyasu, J. E. Merrill, H. V. Vinters, and I. S. Chen. 1987. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science 236:819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larder, B. A., G. Darby, and D. D. Richman. 1989. HIV with reduced sensitivity to zidovudine (AZT) isolated during prolonged therapy. Science 243:1731-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, R., W. A. Paxton, S. Choe, D. Ceradini, S. R. Martin, R. Horuk, M. E. MacDonald, H. Stuhlmann, R. A. Koup, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell 86:367-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda, K., H. Nakata, Y. Koh, T. Miyakawa, H. Ogata, Y. Takaoka, S. Shibayama, K. Sagawa, D. Fukushima, J. Moravek, Y. Koyanagi, and H. Mitsuya. 2004. Spirodiketopiperazine-based CCR5 inhibitor which preserves CC-chemokine/CCR5 interactions and exerts potent activity against R5 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vitro. J. Virol. 78:8654-8662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCandless, E. E., B. Zhang, M. S. Diamond, and R. S. Klein. 2008. CXCR4 antagonism increases T cell trafficking in the central nervous system and improves survival from West Nile virus encephalitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:11270-11275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami, T., T. Nakajima, Y. Koyanagi, K. Tachibana, N. Fujii, H. Tamamura, N. Yoshida, M. Waki, A. Matsumoto, O. Yoshie, T. Kishimoto, N. Yamamoto, and T. Nagasawa. 1997. A small molecule CXCR4 inhibitor that blocks T cell line-tropic HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 186:1389-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murakami, T., T. Y. Zhang, Y. Koyanagi, Y. Tanaka, J. Kim, Y. Suzuki, S. Minoguchi, H. Tamamura, M. Waki, A. Matsumoto, N. Fujii, H. Shida, J. A. Hoxie, S. C. Peiper, and N. Yamamoto. 1999. Inhibitory mechanism of the CXCR4 antagonist T22 against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 73:7489-7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagasawa, T., S. Hirota, K. Tachibana, N. Takakura, S. Nishikawa, Y. Kitamura, N. Yoshida, H. Kikutani, and T. Kishimoto. 1996. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature 382:635-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakashima, H., M. Masuda, T. Murakami, Y. Koyanagi, A. Matsumoto, N. Fujii, and N. Yamamoto. 1992. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of a novel synthetic peptide, T22 ([Tyr-5,12, Lys-7]polyphemusin II): a possible inhibitor of virus-cell fusion. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1249-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oberlin, E., A. Amara, F. Bachelerie, C. Bessia, J. L. Virelizier, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, O. Schwartz, J. M. Heard, I. Clark-Lewis, D. F. Legler, M. Loetscher, M. Baggiolini, and B. Moser. 1996. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTR/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature 382:833-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richman, D. D., and S. A. Bozzette. 1994. The impact of the syncytium-inducing phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus on disease progression. J. Infect. Dis. 169:968-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roehm, N. W., G. H. Rodgers, S. M. Hatfield, and A. L. Glasebrook. 1991. An improved colorimetric assay for cell proliferation and viability utilizing the tetrazolium salt XTT. J. Immunol. Methods 142:257-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenkilde, M. M., L. O. Gerlach, S. Hatse, R. T. Skerlj, D. Schols, G. J. Bridger, and T. W. Schwartz. 2007. Molecular mechanism of action of monocyclam versus bicyclam non-peptide antagonists in the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 282:27354-27365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenkilde, M. M., L. O. Gerlach, J. S. Jakobsen, R. T. Skerlj, G. J. Bridger, and T. W. Schwartz. 2004. Molecular mechanism of AMD3100 antagonism in the CXCR4 receptor: transfer of binding site to the CXCR3 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279:3033-3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samson, M., F. Libert, B. J. Doranz, J. Rucker, C. Liesnard, C. M. Farber, S. Saragosti, C. Lapoumeroulie, J. Cognaux, C. Forceille, G. Muyldermans, C. Verhofstede, G. Burtonboy, M. Georges, T. Imai, S. Rana, Y. Yi, R. J. Smyth, R. G. Collman, R. W. Doms, G. Vassart, and M. Parmentier. 1996. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature 382:722-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schols, D., S. Struyf, J. Van Damme, J. A. Este, G. Henson, and E. De Clercq. 1997. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Exp. Med. 186:1383-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone, N. D., S. B. Dunaway, C. Flexner, C. Tierney, G. B. Calandra, S. Becker, Y. J. Cao, I. P. Wiggins, J. Conley, R. T. MacFarland, J. G. Park, C. Lalama, S. Snyder, B. Kallungal, K. L. Klingman, and C. W. Hendrix. 2007. Multiple-dose escalation study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and biologic activity of oral AMD070, a selective CXCR4 receptor inhibitor, in human subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2351-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strizki, J. M., C. Tremblay, S. Xu, L. Wojcik, N. Wagner, W. Gonsiorek, R. W. Hipkin, C. C. Chou, C. Pugliese-Sivo, Y. Xiao, J. R. Tagat, K. Cox, T. Priestley, S. Sorota, W. Huang, M. Hirsch, G. R. Reyes, and B. M. Baroudy. 2005. Discovery and characterization of vicriviroc (SCH 417690), a CCR5 antagonist with potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4911-4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strizki, J. M., S. Xu, N. E. Wagner, L. Wojcik, J. Liu, Y. Hou, M. Endres, A. Palani, S. Shapiro, J. W. Clader, W. J. Greenlee, J. R. Tagat, S. McCombie, K. Cox, A. B. Fawzi, C. C. Chou, C. Pugliese-Sivo, L. Davies, M. E. Moreno, D. D. Ho, A. Trkola, C. A. Stoddart, J. P. Moore, G. R. Reyes, and B. M. Baroudy. 2001. SCH-C (SCH 351125), an orally bioavailable, small molecule antagonist of the chemokine receptor CCR5, is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 infection in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:12718-12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tachibana, K., S. Hirota, H. Iizasa, H. Yoshida, K. Kawabata, Y. Kataoka, Y. Kitamura, K. Matsushima, N. Yoshida, S. Nishikawa, T. Kishimoto, and T. Nagasawa. 1998. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature 393:591-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takashima, K., H. Miyake, N. Kanzaki, Y. Tagawa, X. Wang, Y. Sugihara, Y. Iizawa, and M. Baba. 2005. Highly potent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by TAK-220, an orally bioavailable small-molecule CCR5 antagonist. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3474-3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamamura, H., H. Tsutsumi, H. Masuno, and N. Fujii. 2007. Development of low molecular weight CXCR4 antagonists by exploratory structural tuning of cyclic tetra- and pentapeptide-scaffolds towards the treatment of HIV infection, cancer metastasis and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Med. Chem. 14:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka, R., A. Yoshida, T. Murakami, E. Baba, J. Lichtenfeld, T. Omori, T. Kimura, N. Tsurutani, N. Fujii, Z. X. Wang, S. C. Peiper, N. Yamamoto, and Y. Tanaka. 2001. Unique monoclonal antibody recognizing the third extracellular loop of CXCR4 induces lymphocyte agglutination and enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1-mediated syncytium formation and productive infection. J. Virol. 75:11534-11543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Urano, E., T. Aoki, Y. Futahashi, T. Murakami, Y. Morikawa, N. Yamamoto, and J. Komano. 2008. Substitution of the myristoylation signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55Gag with the phospholipase C-δ1 pleckstrin homology domain results in infectious pseudovirion production. J. Gen. Virol. 89:3144-3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westby, M., M. Lewis, J. Whitcomb, M. Youle, A. L. Pozniak, I. T. James, T. M. Jenkins, M. Perros, and E. van der Ryst. 2006. Emergence of CXCR4-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) variants in a minority of HIV-1-infected patients following treatment with the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc is from a pretreatment CXCR4-using virus reservoir. J. Virol. 80:4909-4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao, L., D. L. Rudolph, S. M. Owen, T. J. Spira, and R. B. Lal. 1998. Adaptation to promiscuous usage of CC and CXC-chemokine coreceptors in vivo correlates with HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS 12:F137-F143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshida, A., R. Tanaka, T. Murakami, Y. Takahashi, Y. Koyanagi, M. Nakamura, M. Ito, N. Yamamoto, and Y. Tanaka. 2003. Induction of protective immune responses against R5 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in hu-PBL-SCID mice by intrasplenic immunization with HIV-1-pulsed dendritic cells: possible involvement of a novel factor of human CD4+ T-cell origin. J. Virol. 77:8719-8728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zou, Y. R., A. H. Kottmann, M. Kuroda, I. Taniuchi, and D. R. Littman. 1998. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature 393:595-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]