Abstract

We investigated the activity of telavancin, a novel lipoglycopeptide, alone and combined with gentamicin or rifampin (rifampicin) against strains of Staphylococcus aureus with various vancomycin susceptibilities. Strains tested included methicillin (meticillin)-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) 494, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) 1199, heteroresistant glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (hGISA) 1629, which was confirmed by a population analysis profile, and glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (GISA) NJ 992. Regimens of 10 mg/kg telavancin daily and 1 g vancomycin every 12 h were investigated alone and combined with 5 mg/kg gentamicin daily or 300 mg rifampin every 8 h in an in vitro model with simulated endocardial vegetations over 96 h. Telavancin demonstrated significantly greater killing than did vancomycin (P < 0.01) for all isolates except MRSA 494 (P = 0.07). Telavancin absolute reductions, in log10 CFU/g, at 96 h were 2.8 ± 0.5 for MRSA 494, 2.8 ± 0.3 for MSSA 1199, 4.2 ± 0.2 for hGISA 1629, and 4.1 ± 0.3 for GISA NJ 992. Combinations of telavancin with gentamicin significantly enhanced killing compared to telavancin alone against all isolates (P < 0.001) except MRSA 494 (P = 0.176). This enhancement was most evident against hGISA 1629, where killing to the level of detection (2 log10 CFU/g) was achieved at 48 h (P < 0.001). The addition of rifampin to telavancin resulted in significant (P < 0.001) enhancement of killing against only MSSA 1199. No changes in telavancin susceptibilities were observed. These results suggest that telavancin may have therapeutic potential, especially against strains with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Combination therapy, particularly with gentamicin, may improve bacterial killing against certain strains.

The worldwide dissemination and poor treatment outcomes of methicillin (meticillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) present therapeutic difficulties for clinicians. Vancomycin has historically been the mainstay of therapy for serious infections caused by MRSA, but decades of selective pressure have led to evolutionary changes in S. aureus that diminish the utility of this agent (5, 17, 18, 34). Of note is the emergence of S. aureus with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides, including glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (GISA) and heteroresistant GISA (hGISA) strains (16, 33). hGISA is of particular concern, because this organism is not detected by traditional MIC testing or automated methods used in clinical microbiology laboratories (17, 25). Due to these difficulties in detection, the true prevalence of hGISA is difficult to estimate but ranges from ∼2% to ∼11% for isolates from a variety of clinical sources (5, 13, 25, 28, 33). Our own study of hGISA at the Detroit Medical Center demonstrated 8.3% hGISA isolates from the time period 2003 to 2007 and also demonstrated that the number of MRSA strains displaying this phenotype may be increasing (33). This is problematic, as preliminary studies have found an association between infection with hGISA and poor treatment outcomes, including prolonged fever and bacteremia, increased length of hospital stay, and vancomycin treatment failure (5, 17, 18).

Telavancin is a novel lipoglycopeptide antimicrobial with antibacterial activity against a broad range of gram-positive pathogens (7, 8, 14, 19, 20, 22, 23). It is structurally derived from vancomycin by the addition of a hydrophobic decylaminoethyl side chain on the vancosamine sugar and a hydrophilic phosphonomethylaminomethyl group on the 4′ position of amino acid 7 (21). This modification has resulted in a molecule with two mechanisms of action. Similar to vancomycin, telavancin inhibits late-stage peptidoglycan synthesis and cross-linking, but additionally, it targets the bacterial membrane causing disruption of membrane potential and increased permeability (15). The multifunctional mechanism of action of telavancin accounts for its activity against strains of S. aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin, such as GISA and hGISA strains (2, 12, 23, 27).

Telavancin has been studied in a variety of in vitro and in vivo models. In two separate rabbit models of endocarditis, telavancin was found to be effective against both MRSA and GISA strains, though statistically significant differences between telavancin and vancomycin were only observed against GISA strains (27, 29). Clinically, telavancin has been found to be noninferior to vancomycin for the treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections caused by gram-positive pathogens in a large prospective, double-blind, randomized evaluation of patients, including a large number infected with MRSA (MRSA isolated at baseline from 579 clinically evaluable patients) (35). The objective of this investigation was to evaluate the activity of telavancin versus that of vancomycin, both alone and combined with gentamicin or rifampin (rifampicin) against S. aureus strains harboring a spectrum of vancomycin susceptibilities in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model with simulated endocardial vegetations (SEVs). (A portion of this work was presented at the 48th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy [ICAAC]/46th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America [IDSA], Washington, DC, 2008.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Four clinical isolates of S. aureus were evaluated. Three of these isolates were obtained from patients at the Detroit Medical Center: MRSA 494, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) 1199, and hGISA 1629, which was positively confirmed by a population analysis profile and evaluation of the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) ratio, with Mu3 as a positive control, as previously described (33). The fourth isolate tested was GISA NJ 992 (also known as HIP5836) (27, 36).

Antimicrobial agents.

Telavancin (Theravance, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) was provided by the manufacturer. Vancomycin, gentamicin, and rifampin were purchased from a commercial source (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO).

Media.

Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 25 μg/ml of calcium and 12.5 μg/ml magnesium (SMHB) was used for all PK/PD models and microdilution susceptibility testing. SMHB for all models was supplemented with albumin to physiologic conditions (3.5 to 4 g/dl) to account for protein binding. Colony counts were determined using tryptic soy agar (TSA; Difco, Detroit, MI). Etests were performed on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) plates.

Susceptibility testing.

MICs of study antimicrobial agents were determined by broth microdilution at ∼5.5 log10 CFU/ml according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (6). The MICs of vancomycin, gentamicin, and rifampin for samples obtained from the model were determined by Etest and broth microdilution, and the MICs of telavancin were determined only by broth microdilution.

SEVs.

MRSA 494, MSSA 1199, and hGISA 1629 were prepared by spreading the isolates onto six TSA plates and incubating them overnight. The NJ 992 isolate was grown on brain heart infusion agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) containing 2 μg/ml vancomycin. The resultant growth was collected from the plates into 9 ml SMHB. SEVs were prepared as previously described to achieve a final inoculum of ∼9 log10 CFU/g and inserted into the central compartment of the model (1, 31).

In vitro PK/PD model.

An in vitro PK/PD model consisting of a 250-ml glass apparatus with ports to suspend the SEVs was utilized as previously described for all simulations (1, 31). The apparatus was prefilled with media, and the antimicrobials were administered as boluses into the central compartment through an injection port over 96 h. Regimens included 10 mg/kg telavancin daily (target peak, 87.5 μg/ml; target half-life, 8 h), 1 g vancomycin every 12 h (target trough, 10 μg/ml; target half-life, 6 h), 5 mg/kg gentamicin every 24 h (target peak, 15 μg/ml; target half-life, 3 h), and 300 mg rifampin every 8 h (target peak, 4 μg/ml; target half-life, 3 h). All models were performed in duplicate to ensure reproducibility.

PD analysis.

Two SEVs (total of four) were removed from each model at 0, 4, 8, 24, 32, 48, 56, 72, and 96 h. The SEVs were weighed, homogenized, serially diluted in 0.9 ml saline, and plated onto TSA plates. Plates were then incubated at 35°C for 18 to 24 h, at which time colony counts were performed. The total reduction in colony count (log10 CFU/g) was determined by plotting time-kill curves over the 96-hour period with a lower limit of detection of 2 log10 CFU/g. Antibiotic carryover was accounted for by serial dilution or by vacuum filtration (by passing the sample through filter paper, allowing the drug to pass through but retaining the bacterial cells) if the sample drug concentration was close to the MIC of the tested organism. Bactericidal activity was defined at a ≥3 log10 CFU/g (99.9%) reduction in colony count from the initial inoculum. Time to achieve bactericidal activity was determined by linear regression or visual inspection (if r2 ≤ 0.95).

PK analysis.

Samples were obtained through the injection port of each model over the course of the 96-h simulation at 1, 4, 8, 24, 32, 48, 72, and 96 h for verification of target antibiotic concentrations. Concentrations of telavancin were measured by bioassay utilizing Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341 and antibiotic medium 11 (3). The plate was preswabbed with a 0.5 McFarland standard of the test organism, and wells were punched in the agar, filled with standards or samples, and then allowed to dry. Plates were then incubated for 18 to 24 h at 35°C, at which time the zone sizes were measured. This assay had between-day coefficients of variation of 1.5%, 3%, and 4.3% for high, medium, and low (100, 50, and 10 μg/ml) standards, respectively. Vancomycin and gentamicin concentrations were measured by fluorescence polarization immunoassay (TDx; Abbott Diagnostics). This assay has a lower limit of detection of 2 μg/ml for vancomycin and 0.27 μg/ml for gentamicin. For vancomycin, the between-day coefficients of variation were 3.1%, 0.3%, and 0.9% for high, medium, and low standards (75, 35, and 7 μg/ml), respectively, and for gentamicin were 1.3%, 4.8%, and 4.9% for high, medium, and low standards (8, 4, and 1 μg/ml), respectively. Rifampin concentrations were measured by bioassay utilizing Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341. This assay had between-day coefficients of variation of 1.1%, 1.8%, and 5.3% for high, medium, and low standards (5, 2.5, and 0.5 μg/ml), respectively. The elimination half-lives, AUCs, peaks, and troughs were determined by the trapezoidal method with PKAnalyst software (version 1.10; MicroMath Scientific Software, Salt Lake City, UT).

Resistance.

The development of resistance was evaluated at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. One-hundred-microliter samples (from homogenized SEVs) from each time point were plated onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing three times the MIC of either telavancin or vancomycin, depending on the primary drug in the tested regimen, to assess the development of resistance. Plates were examined for growth after 48 h of incubation at 35°C.

Statistical analysis.

Changes in log10 CFU/g at 96 h for each regimen were evaluated by analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (release 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

The test isolate susceptibilities are displayed in Table 1. GISA NJ 992 was resistant to rifampin, and therefore, combinations with rifampin were not run against this isolate. In the PK/PD model, neither gentamicin nor rifampin alone displayed any activity against any isolate and treatment resulted in resistance by 96 h to both drugs for all isolates. No changes in telavancin susceptibility were observed throughout the experiments. The use of vancomycin alone resulted in a small elevation in MIC against hGISA R1629 from 2 to 3 μg/ml. No other changes in MIC were observed.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility results for the four isolates used in the PK/PD model

| Isolate | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telavancin | Vancomycin | Gentamicin | Rifampin | |

| MRSA 494 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.004 |

| MSSA 1199 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.004 |

| hGISA 1629 | 0.125 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.004 |

| GISA NJ 992 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.5 | 2,048 |

PKs obtained in the experiments are displayed in Table 2. In the PK/PD model, telavancin alone demonstrated significantly greater killing than vancomycin alone against MSSA 1199, hGISA 1629, and GISA NJ 992 (P < 0.01), but the difference with MRSA 494 was not significant (P = 0.07). For telavancin, absolute reductions, in log10 CFU/g, at 96 h were 2.8 ± 0.5 for MRSA 494, 2.8 ± 0.3 for MSSA 1199, 4.2 ± 0.2 for hGISA R1629, and 4.1 ± 0.3 for GISA NJ 992. Telavancin alone was bactericidal against two of four isolates—at 64 h against hGISA 1629 and at 62 h against GISA NJ 992. Vancomycin alone was not bactericidal against any isolate over 96 h.

TABLE 2.

PKs of telavancin, vancomycin, gentamicin, and rifampin obtained in the PK/PD modela

| Antibiotic regimen | Cmax (μg/ml) | Cmin (μg/ml) | Half-life (h) | AUC0-24 (μg ml−1 h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telavancin, 10 mg/kg q24h | 88.1 ± 2 | 14.1 ± 2.4 | 9.1 ± 0.7 | 968.8 ± 73.3 |

| Vancomycin, 1 g q12h | 37 ± 0.8 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 391.3 ± 1.9 |

| Gentamicin, 5 mg/kg q24h | 15.8 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 63.1 ± 3.4 |

| Rifampin, 300 mg q8h | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 64.4 ± 3.8 |

Cmax, drug peak concentration; Cmin, drug trough concentration; AUC0-24, area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h; q24h, every 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

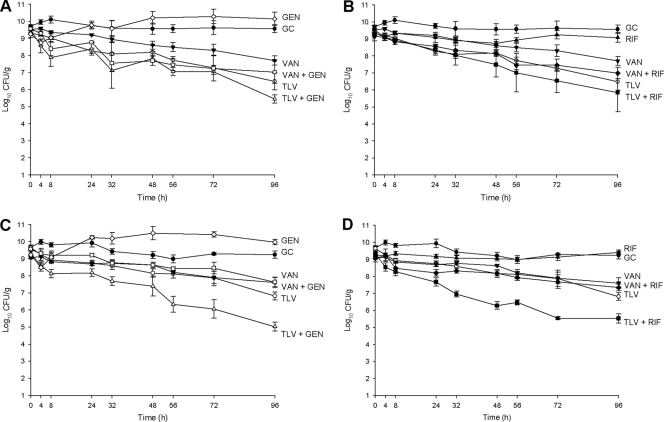

Combination with gentamicin or rifampin improved the activity, over that of telavancin alone, against MSSA 1199. Against MRSA 494, however, the improvement in killing of ∼1 log10 CFU/g at 96 h was not statistically significant (P = 0.176, for comparison with the combination of telavancin plus gentamicin, and P = 0.679, for comparison with the combination of telavancin plus rifampin). However, both of these combinations resulted in the achievement of bactericidal activity: at 73 h with the combination of telavancin and rifampin and at 66 h with the combination of telavancin and gentamicin. Significant (P < 0.001) improvements in activity of 1 to 2 log10 CFU/g were observed against MSSA 1199 when telavancin was combined with gentamicin or rifampin compared to when telavancin was used alone, and bactericidal activity was attained at 52 h when telavancin was combined with rifampin and at 56 h when it was combined with gentamicin. The addition of gentamicin or rifampin to vancomycin resulted in small or no improvements in activity compared to activity with vancomycin alone against MRSA 494 and MSSA 1199, which were not significant (P ≥ 0.561, for all comparisons). Results are displayed in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Activity of 10 mg/kg telavancin daily and 1 g vancomycin every 12 h alone and in combination with gentamicin and rifampin against MRSA and MSSA. (A) Gentamicin combinations for MRSA 494. (B) Rifampin combinations for MRSA 494. (C) Gentamicin combinations for MSSA 1199. (D) Rifampin combinations for MSSA 1199. TLV, telavancin; VAN, vancomycin; GC, growth control (organism growth with no drug added); GEN, gentamicin; RIF, rifampin. Closed circles, growth control; open circles, 10 mg/kg telavancin daily; closed inverted triangles, 1 g vancomycin every 12 h; open diamonds, 5 mg/kg gentamicin daily; closed triangles, 300 mg rifampin every 8 h; open triangles, telavancin plus gentamicin; closed squares, telavancin plus rifampin; open squares, vancomycin plus gentamicin; closed diamonds, vancomycin plus rifampin.

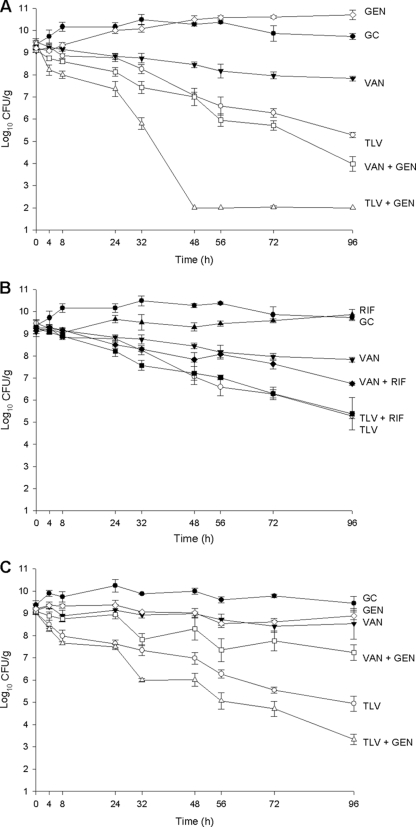

Combination of telavancin with gentamicin also improved killing against strains with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin (hGISA 1629 and GISA NJ 992). Against hGISA 1629, the combination of telavancin and gentamicin resulted in killing to the level of detection (2 log10 CFU/g) as early as 48 h and achieved bactericidal activity at 27 h. This isolate also displayed enhancement in killing, with the combination of vancomycin and gentamicin resulting in 5.1 ± 0.3 log10 CFU/g killing at 96 h and bactericidal activity at 58 h. However, combination of telavancin with rifampin did not demonstrate enhanced killing (P = 0.99), though the combination of vancomycin and rifampin resulted in an approximately 1 log10 CFU/g enhancement at 96 h which was significant (P = 0.001). Vancomycin plus rifampin against hGISA 1629 still did not achieve bactericidal activity at 96 h. The addition of gentamicin to telavancin resulted in a significant enhancement of killing of GISA NJ 992 (P < 0.001), with 5.7 ± 0.2 log10 CFU/g killing at 96 h and achievement of bactericidal activity at 40 h. The addition of gentamicin to vancomycin significantly improved killing of GISA NJ 992, compared to that using vancomycin alone, by ∼1 log10 CFU/g at 96 h (P = 0.004), though bactericidal activity was not achieved at 96 h. Results are displayed in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Activity of 10 mg/kg telavancin daily and 1 g vancomycin every 12 h alone and in combination with gentamicin and rifampin against hGISA and GISA. (A) Gentamicin combinations for hGISA 1629. (B) Rifampin combinations for hGISA 1629. (C) GISA NJ 992. TLV, telavancin; VAN, vancomycin; GC, growth control (organism growth with no drug added); GEN, gentamicin; RIF, rifampin. Closed circles, growth control; open circles, 10 mg/kg telavancin daily; closed inverted triangles, 1 g vancomycin every 12 h; open diamonds, 5 mg/kg gentamicin daily; closed triangles, 300 mg rifampin every 8 h; open triangles, telavancin plus gentamicin; closed squares, telavancin plus rifampin; open squares, vancomycin plus gentamicin; closed diamonds, vancomycin plus rifampin.

DISCUSSION

S. aureus is a leading cause of infective endocarditis, carrying a mortality rate of approximately 30% when acquired in the health care setting (11). Historically, the drug of choice for the treatment of infections caused by MRSA has been vancomycin; however, high rates of clinical failure and increasing reports of reduced susceptibility call into question the utility of this agent and raise the need for alternative therapies (5, 13, 17, 18, 24, 26, 33). Due to structural and mechanistic similarities between telavancin and vancomycin, we investigated the activity of telavancin against strains with various susceptibilities to vancomycin.

Consistent with previous investigations (2, 7, 8, 12, 23, 27, 29), we found telavancin to be active and, in most cases, superior to vancomycin against S. aureus, including hGISA and GISA. As expected, vancomycin was more active against MSSA and MRSA than against hGISA and GISA, and therefore, the difference between vancomycin and telavancin was not as large against MSSA and MRSA. Another possible contribution to the difference between telavancin and vancomycin activities being larger against hGISA and GISA was that the magnitude of telavancin's killing was greater against these isolates than against MSSA and MRSA isolates. Though perhaps counterintuitive, the extent of killing with telavancin against GISA being greater than that against MRSA has been previously documented (27). The reason behind this is not immediately clear, but it should be noted that the same strain of GISA (NJ 992; also known as HIP5836) was used in both investigations, and therefore, it may be a strain-specific event.

The effect of combination therapy for the treatment of S. aureus infections remains controversial. In vitro evaluations of rifampin combinations generally show improvement in killing or no change. However, clinical experience with vancomycin combined with rifampin in patients with endocarditis was in opposition to these results, showing a duration of bacteremia with the combination that is 2 days longer than that with vancomycin alone (7 days with vancomycin alone and 9 days with vancomycin plus rifampin) (24). In our investigation, we found that the combination of vancomycin and rifampin improved activity compared to that with vancomycin alone against one of three isolates (hGISA 1629) and that the addition of rifampin to telavancin improved killing against one of three isolates tested (MSSA 1199). These results indicate that enhancement in killing with rifampin is less predictable in vitro and may be a strain-specific event.

Combination therapy with an aminoglycoside for serious infections caused by S. aureus also remains controversial, though the practice is common, including its use as a comparator arm in a recent clinical trial (10). The theoretical benefit of combination with an aminoglycoside is early, rapid reduction in the organism burden, and therefore, it is done in spite of scant clinical evidence (4, 9). In our investigation, we found that the addition of gentamicin to telavancin significantly improved killing compared to that with telavancin alone (except with MRSA 494). This is an expected result, as in vitro enhancements of killing with the addition of gentamicin to both glycopeptide and lipopeptide agents have been previously documented (31, 37). It should be noted, however, that both telavancin and aminoglycosides have been associated with some degree of renal toxicity, and therefore, caution is warranted with the combination (30, 35). The use of once-daily aminoglycosides, as well as a shorter duration of aminoglycoside therapy, seems to ameliorate nephrotoxicity issues associated with these agents (32), though additive nephrotoxic effects when combined with telavancin, if any, have yet to be clinically evaluated.

A potential limitation of this study is that we only examined four isolates, one of each phenotype described. This is of particular importance when discussing hGISA and GISA, due to the heterogeneous nature of their susceptibilities to glycopeptide antibiotics and the wide variation observed between organisms sharing the phenotype (33). Therefore, caution is warranted for generalizing these results to all strains of S. aureus.

In summary, we found telavancin to be active against S. aureus in an in vitro model with simulated endocardial vegetations, especially against strains with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Combination therapy generally improved bacterial killing compared to that with telavancin alone, in particular the combination of telavancin and gentamicin. No changes in susceptibility to telavancin were noted in this study. Telavancin may have potential for the treatment of endocarditis caused by S. aureus, including hGISA and GISA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Astellas Pharma Inc.

M.J.R. has consulted or has obtained funding from Astellas, Cubist, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Targanta, and Forest Pharmaceuticals. S.N.L. and C.V. have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins, R. L., and M. J. Rybak. 2001. Bactericidal activities of two daptomycin regimens against clinical strains of glycopeptide intermediate-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model with simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:454-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barcia-Macay, M., S. Lemaire, M. P. Mingeot-Leclercq, P. M. Tulkens, and F. Van Bambeke. 2006. Evaluation of the extracellular and intracellular activities (human THP-1 macrophages) of telavancin versus vancomycin against methicillin-susceptible, methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1177-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barcia-Macay, M., F. Mouaden, M. P. Mingeot-Leclercq, P. M. Tulkens, and F. Van Bambeke. 2008. Cellular pharmacokinetics of telavancin, a novel lipoglycopeptide antibiotic, and analysis of lysosomal changes in cultured eukaryotic cells (J774 mouse macrophages and rat embryonic fibroblasts). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:1288-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers, H. F., R. T. Miller, and M. D. Newman. 1988. Right-sided Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in intravenous drug abusers: two-week combination therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 109:619-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charles, P. G., P. B. Ward, P. D. Johnson, B. P. Howden, and M. L. Grayson. 2004. Clinical features associated with bacteremia due to heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:448-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard, 7th ed. CLSI, Wayne, PA.

- 7.Draghi, D. C., B. M. Benton, K. M. Krause, C. Thornsberry, C. Pillar, and D. F. Sahm. 2008. Comparative surveillance study of telavancin activity against recently collected gram-positive clinical isolates from across the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2383-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Draghi, D. C., B. M. Benton, K. M. Krause, C. Thornsberry, C. Pillar, and D. F. Sahm. 2008. In vitro activity of telavancin against recent gram-positive clinical isolates: results of the 2004-05 Prospective European Surveillance Initiative. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:116-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortún, J., E. Navas, J. Martinez-Beltran, J. Perez-Molina, P. Martin-Davila, A. Guerrero, and S. Moreno. 2001. Short-course therapy for right-side endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus in drug abusers: cloxacillin versus glycopeptides in combination with gentamicin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:120-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler, V. G., Jr., H. W. Boucher, G. R. Corey, E. Abrutyn, A. W. Karchmer, M. E. Rupp, D. P. Levine, H. F. Chambers, F. P. Tally, G. A. Vigliani, C. H. Cabell, A. S. Link, I. DeMeyer, S. G. Filler, M. Zervos, P. Cook, J. Parsonnet, J. M. Bernstein, C. S. Price, G. N. Forrest, G. Fatkenheuer, M. Gareca, S. J. Rehm, H. R. Brodt, A. Tice, and S. E. Cosgrove. 2006. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:653-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler, V. G., Jr., J. M. Miro, B. Hoen, C. H. Cabell, E. Abrutyn, E. Rubinstein, G. R. Corey, D. Spelman, S. F. Bradley, B. Barsic, P. A. Pappas, K. J. Anstrom, D. Wray, C. Q. Fortes, I. Anguera, E. Athan, P. Jones, J. T. van der Meer, T. S. Elliott, D. P. Levine, and A. S. Bayer. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: a consequence of medical progress. JAMA 293:3012-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gander, S., A. Kinnaird, and R. Finch. 2005. Telavancin: in vitro activity against staphylococci in a biofilm model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:337-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garnier, F., D. Chainier, T. Walsh, A. Karlsson, A. Bolmstrom, C. Grelaud, M. Mounier, F. Denis, and M. C. Ploy. 2006. A 1 year surveillance study of glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strains in a French hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:146-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein, E. J., D. M. Citron, C. V. Merriam, Y. A. Warren, K. L. Tyrrell, and H. T. Fernandez. 2004. In vitro activities of the new semisynthetic glycopeptide telavancin (TD-6424), vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid, and four comparator agents against anaerobic gram-positive species and Corynebacterium spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2149-2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins, D. L., R. Chang, D. V. Debabov, J. Leung, T. Wu, K. M. Krause, E. Sandvik, J. M. Hubbard, K. Kaniga, D. E. Schmidt, Jr., Q. Gao, R. T. Cass, D. E. Karr, B. M. Benton, and P. P. Humphrey. 2005. Telavancin, a multifunctional lipoglycopeptide, disrupts both cell wall synthesis and cell membrane integrity in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1127-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiramatsu, K., N. Aritaka, H. Hanaki, S. Kawasaki, Y. Hosoda, S. Hori, Y. Fukuchi, and I. Kobayashi. 1997. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 350:1670-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howden, B. P., P. D. Johnson, P. B. Ward, T. P. Stinear, and J. K. Davies. 2006. Isolates with low-level vancomycin resistance associated with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3039-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howden, B. P., P. B. Ward, P. G. Charles, T. M. Korman, A. Fuller, P. du Cros, E. A. Grabsch, S. A. Roberts, J. Robson, K. Read, N. Bak, J. Hurley, P. D. Johnson, A. J. Morris, B. C. Mayall, and M. L. Grayson. 2004. Treatment outcomes for serious infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:521-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jansen, W. T., A. Verel, J. Verhoef, and D. Milatovic. 2007. In vitro activity of telavancin against gram-positive clinical isolates recently obtained in Europe. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3420-3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King, A., I. Phillips, and K. Kaniga. 2004. Comparative in vitro activity of telavancin (TD-6424), a rapidly bactericidal, concentration-dependent anti-infective with multiple mechanisms of action against gram-positive bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:797-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leadbetter, M. R., S. M. Adams, B. Bazzini, P. R. Fatheree, D. E. Karr, K. M. Krause, B. M. Lam, M. S. Linsell, M. B. Nodwell, J. L. Pace, K. Quast, J. P. Shaw, E. Soriano, S. G. Trapp, J. D. Villena, T. X. Wu, B. G. Christensen, and J. K. Judice. 2004. Hydrophobic vancomycin derivatives with improved ADME properties: discovery of telavancin (TD-6424). J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 57:326-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonard, S. N., and M. J. Rybak. 2008. Telavancin: an antimicrobial with a multifunctional mechanism of action for the treatment of serious gram-positive infections. Pharmacotherapy 28:458-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leuthner, K. D., C. M. Cheung, and M. J. Rybak. 2006. Comparative activity of the new lipoglycopeptide telavancin in the presence and absence of serum against 50 glycopeptide non-susceptible staphylococci and three vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:338-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine, D. P., B. S. Fromm, and B. R. Reddy. 1991. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifampin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann. Intern. Med. 115:674-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, C., and H. F. Chambers. 2003. Staphylococcus aureus with heterogeneous resistance to vancomycin: epidemiology, clinical significance, and critical assessment of diagnostic methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3040-3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lodise, T. P., J. Graves, A. Evans, E. Graffunder, M. Helmecke, B. M. Lomaestro, and K. Stellrecht. 2008. Relationship between vancomycin MIC and failure among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia treated with vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3315-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madrigal, A. G., L. Basuino, and H. F. Chambers. 2005. Efficacy of telavancin in a rabbit model of aortic valve endocarditis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3163-3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maor, Y., G. Rahav, N. Belausov, D. Ben-David, G. Smollan, and N. Keller. 2007. Prevalence and characteristics of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in a tertiary care center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1511-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miró, J. M., C. Garcia-de-la-Maria, Y. Armero, E. de-Lazzari, D. Soy, A. Moreno, A. del Rio, M. Almela, C. A. Mestres, J. M. Gatell, M. T. Jimenez-de-Anta, and F. Marco. 2007. Efficacy of telavancin in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2373-2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murry, K. R., P. S. McKinnon, B. Mitrzyk, and M. J. Rybak. 1999. Pharmacodynamic characterization of nephrotoxicity associated with once-daily aminoglycoside. Pharmacotherapy 19:1252-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose, W. E., S. N. Leonard, and M. J. Rybak. 2008. Evaluation of daptomycin pharmacodynamics and resistance at various dosage regimens against Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibilities to daptomycin in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model with simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3061-3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rybak, M. J., B. J. Abate, S. L. Kang, M. J. Ruffing, S. A. Lerner, and G. L. Drusano. 1999. Prospective evaluation of the effect of an aminoglycoside dosing regimen on rates of observed nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1549-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rybak, M. J., S. N. Leonard, K. L. Rossi, C. M. Cheung, H. S. Sadar, and R. N. Jones. 2008. Characterization of vancomycin heteroresistant Staphylococcus aureus from the metropolitan area of Detroit, Michigan, over a 22-year period (1986 to 2007). J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2950-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, V. G. Fowler, Jr., R. C. Moellering, Jr., R. P. Novick, N. Lucindo, M. R. Yeaman, and A. S. Bayer. 2005. Reduced susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to vancomycin and platelet microbicidal protein correlates with defective autolysis and loss of accessory gene regulator (agr) function. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2687-2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stryjewski, M. E., D. R. Graham, S. E. Wilson, W. O'Riordan, D. Young, A. Lentnek, D. P. Ross, V. G. Fowler, A. Hopkins, H. D. Friedland, S. L. Barriere, M. M. Kitt, and G. R. Corey. 2008. Telavancin versus vancomycin for the treatment of complicated skin and skin-structure infections caused by gram-positive organisms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1683-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tenover, F. C., M. V. Lancaster, B. C. Hill, C. D. Steward, S. A. Stocker, G. A. Hancock, C. M. O'Hara, S. K. McAllister, N. C. Clark, and K. Hiramatsu. 1998. Characterization of staphylococci with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin and other glycopeptides. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1020-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuji, B. T., and M. J. Rybak. 2005. Short-course gentamicin in combination with daptomycin or vancomycin against Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model with simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2735-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]