Abstract

Bacillus subtilis F29-3 produces an antifungal peptidic antibiotic that is synthesized nonribosomally by fengycin synthetases. Our previous work established that the promoter of the fengycin synthetase operon is located 86 nucleotides upstream of the translational initiation codon of fenC. This investigation involved transcriptional fusions with a DNA fragment that contains the region between positions −105 and +80 and determined that deleting the region between positions −55 and −42 reduces the promoter activity by 64.5%. Transcriptional fusions in the B. subtilis DB2 chromosome also indicated that mutating the sequence markedly reduces the promoter activity. An in vitro transcription analysis confirmed that the transcription is inefficient when the sequence in this region is mutated. Electrophoretic mobility shift and footprinting analyses demonstrated that the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit binds to the region between positions −55 and −39. These results indicated that the sequence is an UP element. Finally, this UP element is critical for the production of fengycin, since mutating the UP sequence in the chromosome of B. subtilis F29-3 reduces the transcription of the fen operon by 85% and prevents the cells from producing enough fengycin to suppress the germination of Paecilomyces variotii spores on agar plates.

Bacillus subtilis F29-3 produces an antifungal antibiotic, fengycin, which is a cyclic lipopeptide that contains 10 amino acids with a 14- to 18-carbon fatty acyl residue that is attached to the N terminus of the peptide (47). Previous studies have demonstrated that fengycin is synthesized nonribosomally by an enzyme complex that is formed by five fengycin synthetases, FenC, FenD, FenE, FenA, and FenB (8). These enzymes interlock to form a chain in the order FenC-FenD-FenE-FenA-FenB in interactions between the C-terminal region of an upstream enzyme and the N-terminal region of its downstream partner enzyme (48). These enzymes contain at least one module, and each module activates an amino acid that is incorporated into fengycin (28, 30, 41), allowing the activated amino acids to form a peptide on the enzyme chain (13). The modules typically contain an adenylation domain consisting of about 550 amino acids (10), which recognizes and adenylates an amino acid (13, 42, 44, 51). Following adenylation, the adenylated amino acid is covalently linked through a thioester bond to the cofactor 4′-phosphopantetheine, which is bound to the thiolation domain (27, 40, 43, 45, 46). Meanwhile, in the C-terminal region, every fengycin synthetase except FenB contains an epimerase domain that converts an l-amino acid to a d-amino acid (9, 31). During fengycin synthesis, l-Glu, which is activated by the initiating module FenC1, covalently links to l-Orn, which is activated by the adjacent downstream module FenC2 to form a peptide. The epimerase domain that is located in the C-terminal region of FenC2 then converts l-Orn to d-Orn before the peptide is translocated to FenD to generate a peptide with l-Tyr that is activated by the FenD1 module (31). This process continues from one module to the next and from one fengycin synthetase to the next in the fengycin synthetase complex until the peptide reaches FenB, where the peptide is circularized and cleaved by the thioesterase domain of the enzyme (24, 26). Lin et al. (29) showed that the genes in the fengycin synthetase operon (fen operon) encode the five fengycin synthetases. These genes are positioned colinearly with the enzymes in the fengycin synthetase chain and the amino acids in fengycin (48). Lin et al. (29) also established that the promoter (fenp) which transcribes the operon is located 86 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the translation initiation codon of fenC.

It is generally known that the efficient binding of an RNA polymerase holoenzyme to a promoter is crucial for transcription. For instance, the lac promoter in Escherichia coli has two sites in the region between positions −50 and −38 for binding of a cyclic AMP-catabolite activator protein complex (36). The catabolite activator protein is known to interact with the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit (αCTD) to anchor RNA polymerase to the promoter (36). This interaction is required for efficient transcription of the lac operon when glucose is not present in the culture medium. Rather than interacting with a protein, αCTD also binds to a stretch of the 17-bp A- and T-rich sequence called the UP element that is located upstream of the −35 region to facilitate efficient binding of RNA polymerase to a promoter (18). In fact, each of the two αCTDs in RNA polymerase binds to two subsites, which are centered at positions −42 and −52 in the UP element (12). The binding of αCTD to an UP element may enhance the transcription activity by a factor of up to 340 (12). A genetic study revealed that seven amino acid residues, L262, R265, N268, C269, G296, K298, and S299, in αCTD are critical for the binding to the rrnB P1 UP element in E. coli (17). The C265 residue in the Bacillus αCTD was also critical for binding (53). This work shows that fenp contains an UP element. Efficient transcription of the fengycin synthetase operon and production of fengycin depend on this sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture media.

B. subtilis F29-3 is a wild-type strain that produces fengycin (47). A transcriptional fusion was generated in the B. subtilis DB2 (6) chromosome to analyze fenp activity. B. subtilis F29-3 mutants FK920 and FK921 were used to study the function of the UP element in fenp. E. coli EPI300 was used as a host for gene cloning (Epicentre, Madison, WI). E. coli BL21(DE3) was used for protein expression (37). nHA medium (47), which was used for production of fengycin by B. subtilis F29-3, contained 0.5% yeast extract, 2% malt extract broth, 1% glucose, and 0.4% sodium chloride. B. subtilis was cultured in nHA medium. LB medium (33) was used to culture both E. coli and B. subtilis.

Plasmids.

Plasmid pGHL6 (29) was utilized to generate a transcriptional fusion between fenp and luxAB. Plasmid pWRK100, which expresses histidine-tagged αCTD (His-αCTD) from amino acid 229 to amino acid 314 (53), was constructed by inserting a PCR-amplified DNA fragment that encodes αCTD into the EcoRI and XhoI sites in pET-32a(+) (Novagen, San Diego, CA). Plasmid pWRK200 encodes His-αCTD with a C265A mutation and was constructed by a site-directed mutagenesis method described elsewhere (34). A DNA fragment that encodes the N-terminal region of the RNA polymerase α subunit (αNTD) from amino acid 1 to amino acid 228 was amplified by PCR and was inserted into the EcoRI and XhoI sites in pET-32a(+) to construct pWRK300. Plasmid pDH32 (23) was employed to construct transcriptional fusions in amyE in the chromosome of B. subtilis DB2. A temperature-sensitive plasmid, pGEC8 (7), was used to create mutations by homologous recombination in the B. subtilis F29-3 chromosome. A 186-bp fragment that contains the region between positions −105 and +80 in the fen operon was amplified by PCR with primers P105 (5′-GCGCGAGCTCTCAATCAAGAAAAAATAAATTAATT) and P+80 (5′-GCGCGGTACCCCCTCCAATTCTAATTTATAAGAGG) using chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis F29-3 (47) as the template. After digestion with SacI and KpnI, the DNA fragment was inserted into the SacI-KpnI sites in pGHL6 (29) to obtain pDFen105 (Fig. 1B). Plasmids pDFen197, pDFen75, pDFen60, pDFen55, pDFen42, and pDFen20 (Fig. 1B), which contain fenp regions from position −197 to position +80, from position −75 to position +80, from position −60 to position +80, from position −55 to position +80, from position −42 to position +80, and from position −20 to position +80, respectively, were constructed using pGHL6 and the same strategy. Plasmids pDFen35 and pDFen10 contained −35 and −10 sequences that were mutated from 5′-TTGTAC and 5′-TATAAT to 5′-GGTGCA and 5′-GCGCCG, respectively. A 60-bp double-stranded synthetic oligonucleotide that contained the region from position −60 to position −1 and had a SacI site at the −60 end and a KpnI site at the −1 end was synthesized by Bio Basic Inc. (Ontario, Canada). This fragment was inserted into the SacI-KpnI sites in pGHL6 to obtain pDFen601 (Fig. 1B). Six pDFen601 mutant derivatives, pDFen601-M1 to pDFen601-M6 (Fig. 1B), which had mutations in the region from position −55 to position −39 (sequence change from 5′-AAAAATTTTATATTTTT to 5′-CCCCCGGGGCGCGGGGG), from position −52 to position −50 (5′-AAT to 5′-CCG), from position −49 to position −47 (5′-TTT to 5′-GGG), from position −42 to position −40 (5′-TTT to 5′-GGG), from position −36 to position −31 (5′-TTGTAC to 5-GGTGCA), and from position −11 to position −6 (5′-TATAAT to 5′-GCGCCG), were formed by inserting synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides into pGHL6.

FIG. 1.

Sequence of the region upstream of fenC and plasmids that were used in this study. (A) −35 and −10 indicate the −35 and −10 boxes in the fengycin synthetase promoter. +1 indicates the transcription start site; RBS indicates the ribosomal binding site. The translation initiation site is located at position +87 and is underlined. UP indicates the UP element. (B) Transcriptional fusions were formed in pGHL6 with DNA fragments that contained the sequence upstream of fenC. The numbers indicate positions relative to the transcription start site. In pDFen601-M1, pDFen601-M2, pDFen601-M3, and pDFen601-M4, the sequences in the UP region from position −55 to position −39, from position −52 to position −50, from position −49 to position −47, and from position −42 to position −40, respectively, were mutated. Plasmids pDFen601-M5 and pDFen601-M6 contained mutations in the −35 and −10 boxes, respectively.

Generating transcriptional fusions in the B. subtilis DB2 chromosome.

DNA fragments that contained the fenp sequence and luxAB were amplified by PCR and then inserted into the BamHI-SacI sites in pDH32. The plasmids were linearized by PstI digestion and then inserted into amyE in the B. subtilis DB2 chromosome by homologous recombination using a method described elsewhere (6).

Mutation of the UP element in fenp in the B. subtilis F29-3 chromosome.

A 1-kb fragment that covers the region between positions +86 and +1085 in the fen operon was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-CGCGGGTACCTTGAAAGAAAATACTTATGG and 5′-CGCGGAGCTCCACCAGCAAATTATAAGGAA. This fragment was digested by KpnI and SacI before it was inserted into the KpnI-SacI sites in pGEC8 to obtain pGEC910. A 277-bp fenp fragment that covered the region between positions −197 and +80 was amplified with primers 5′-CGCGGGATCCTATGAAATTAAATAATTGAA and 5′-CGCGGGTACCCCCTCCAATTCTAATTTATA using pDFen197-M1, which contains a mutated UP element that is in pDFen601-M1, as the template. This fragment was digested with BamHI and KpnI and inserted into the BamHI-KpnI sites in pGEC910 to generate pGEC921. The sequence of pGEC920 was identical to that of pGEC921 except that the former plasmid contained a wild-type fenp sequence, which was amplified using pDFen197 as the template. Plasmids pGEC920 and pGEC921 were transformed individually into B. subtilis F29-3. Cells were cultured at 30°C in LB broth that contained 5 μg/ml of chloramphenicol to the mid-log phase and then subcultured using a 1% inoculum in LB broth at 50°C for 5 h to cure the plasmids. The cells were serially diluted with phosphate-buffered saline, plated on LB agar that contained 5 μg/ml of chloramphenicol, and cultured overnight at 50°C to generate strains FK920 and FK921. Insertion of the pGEC920 and pGEC921 plasmids into fenp was confirmed by PCR using primers 5′-TAATGTGGTCTTTATTCTTC and 5′-GCAGCTTAAACGGAATTCTGGCTTG, which amplified a DNA fragment from a region that is upstream of the chloramphenicol resistance gene in pGEC8 to position +1113 in the fen operon. The mutation of the UP sequence in pGEC921 was verified by sequencing a PCR-amplified DNA fragment that contains the UP region.

Luciferase assay.

nHA broth that contained 5 μg/ml of chloramphenicol (nHA-Cm) was inoculated with an overnight culture using a 1% inoculum. Following inoculation, the culture was aliquoted into test tubes (2 by 15 cm), and the cells in the tubes were cultured at 37°C with constant shaking. At each sampling time, three tubes were removed from the shaker, and the luciferase activity of the cells was monitored using a luminometer (model LB953; Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany) (29). The A600 of a culture was measured using a spectrophotometer after dilution. The cultures in the test tubes were discarded after monitoring.

Purification of His-αCTD, His-αNTD, and His-αCTD(C265A).

E. coli BL21(pWRK100), E. coli BL21(pWRK200), or E. coli BL21(pWRK300) was cultured in 100 ml of LB medium to the mid-log phase. Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM to induce the expression of His-αCTD, His-αNTD, and His-αCTD(C265A). After they had been cultured for an additional 3 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in 4 ml lysis buffer that contained 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cells were homogenized using a French press (Thermo Spectronic, Madison, WI) at 1,000 lb/in2. The lysate was centrifuged at 17,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. Proteins were purified from the lysate using a column packed with 400 μl Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at 4°C by a method described elsewhere (29).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

DNA probes were labeled at the 3′ terminus using a biotin 3′-end DNA labeling kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Each reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 0.5 nM biotinylated probe and 4 μM His-αCTD in buffer that contained 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 75 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 1 μg poly(dI-dC). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min and analyzed using a 5% polyacrylamide gel according to a method described elsewhere (3). After electrophoresis, DNA was transferred to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, Hong Kong). Biotinylated DNA was detected by using a chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module (Pierce). Probe WT-45 contained the sequence between positions −65 and −26 in fenp (5′-AAACTGTTATAAAAATTTTATATTTTTTATTGTAC); M-45 contained the sequence 5′-AAACTGTTATCCCCCGGGGCGCGGGGGTATTGTAC.

In vitro transcription.

In vitro transcription was performed using a 40-μl reaction mixture and a method described elsewhere (21). The core RNA polymerase and σA that were used in the reaction were purified from B. subtilis using methods described previously (21). The DNA templates used in the reactions contained the sequence from position −197 to position +80 in fenp and sequences that contained a mutated UP element and the −35 and −10 regions, which were amplified from pDFen197, pDFen197-M1, pDFen35, and pDFen10, respectively. A 57-nt RNA marker was transcribed in vitro from the tms promoter (C. I. Yen and B. Y. Chang, unpublished). Next, a 140-nt RNA marker was transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase from a DNA fragment that contained the T7 promoter and its downstream sequence in pGEM-7Zf(+). This DNA fragment was amplified using primers T7-F (5′-CAGTGAATTGTAATACGACT) and T7-R (5′-ATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAA) and pGEM-7Zf(+) as the template. The DNA fragment was also cut by BamHI and used to transcribe an 83-nt transcript. DNA templates for in vitro transcription were purified from a 2% agarose gel using a DNA clean extraction kit (GeneMark, Taiwan). The concentrations of the templates were determined spectrophotometrically at A260 using a spectrophotometer (model Libra S12; Biochrom, United Kingdom).

DNase I footprinting.

A DNA probe that contained the region from position −147 to position +50 was amplified by PCR using primers P-147 (5′-AATCGATACTTTCATAACTT) and P+50 (5′-AAACTGAAATAATTACAATA) that had been labeled at the 5′ end with 32P using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Purified His-αCTD, His-αNTD, or His-αCTD(C265A) was incubated with 0.5 nM probe in 40 μl of DNA binding buffer that contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.02 mM EDTA, 30 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, and 12% glycerol for 30 min at 25°C. Subsequently, 0.175 U of DNase I (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was added to the reaction mixture to cleave the DNA for 30 s. DNase I footprinting was performed by using a procedure described elsewhere (53). DNA sequencing was performed using a PCR product sequencing kit (version 2.0; USB, Cleveland, OH).

Bioassay of fengycin activity.

The antifungal activity of fengycin was assayed with spore plates that had been prepared with Paecilomyces variotii Tü137 spores using a method described by Zähner and Maas (52).

Quantification of fen mRNA by real-time PCR.

Total RNA was prepared from cells using the acid-phenol extraction method of Aiba et al. (1). cDNA was synthesized with 2 μg of RNA using 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) in 25 μl of reaction buffer supplied by the manufacturer. Real-time PCR was performed using a reaction mixture that contained 2 μl of cDNA, 0.2 μM forward primer 5′-GCCCAAAGGAGAGTTTGGTTTACTG, and 0.2 μM reverse primer 5′-GCAGCTTAAACGGAATTCTGGCTTG, which amplified the region in the fen operon from position +807 to position +1113, using a SYBR Advantage quantitative PCR premix kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). DNA was amplified with a Bio-Rad iCycleriQ thermocycler (Hercules, CA). Annealing and elongation were performed for 45 s at 60°C; denaturation was performed for 45 s at 94°C. A segment of rpoA between nt 685 and 933 was amplified with primers 5′-GACGAAGCTCAACATGCTGAAATCA and 5′-GCGAAGTCCGAGTCCAAGTTCTTCT and used as an internal control. The mean difference in the cycle threshold (ΔCT) value obtained from amplification of FK920 and FK921 fen mRNA in three independent experiments was normalized with the ΔCT value for the internal control. The relative amounts of mRNA were determined by a method described elsewhere (14).

RESULTS

Transcription from fenp.

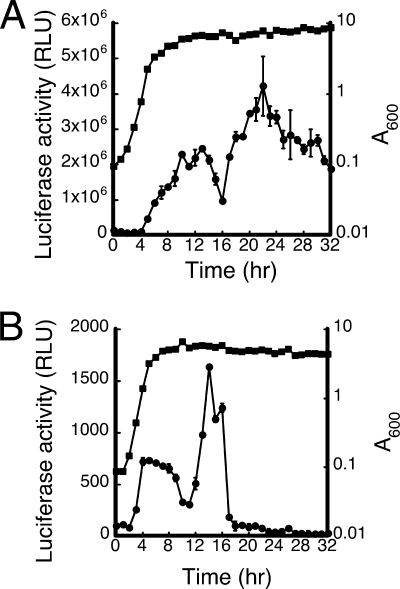

Previous work revealed that transcription of the fen operon starts at nt 86 upstream of the initiation codon of fenC (29). Accordingly, this study used a DNA fragment that covered the region between positions −105 and +80 in fenp to generate a transcriptional fusion with luxAB in pGHL6 to investigate the regulation of fenp (Fig. 1). nHA-Cm broth was inoculated with B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen105), and the luciferase activity of the cells was monitored over a 32-h period. In our first experiment, luciferase activity was monitored at each sampling time with the cells that were taken from a single flask. B. subtilis may undergo autolysis during the stationary phase when cells experience a drastic temperature shift (49). Hence, repeated sampling of a culture at room temperature using a single flask removed from a 37°C shaker may have influenced cell viability, explaining why the experimental results obtained were frequently erratic and irreproducible, especially after the cells had entered the stationary phase. To overcome this problem, the culture was aliquoted into test tubes following inoculation. At each time point, three tubes were taken from the shaker to determine the luciferase activity, and they were then discarded after analysis. Under these culture conditions, cells were found to reach the early stationary phase 8 to 9 h after inoculation. The luciferase activity of the cells increased throughout the log phase and after the cells entered the early stationary phase (Fig. 2A). However, the activity decreased rapidly between 13 and 16 h (Fig. 2A). The activity increased again after 16 h, reaching a peak at 22 h (Fig. 2A). The drop in activity was probably not caused by the marked instability of luciferase during the period between 13 and 16 h, since many promoters associated with fengycin production, including that of fenF (GenBank accession number L42526), were actively transcribed at high levels during this period (data not shown). A similar transcriptional fusion was generated in the B. subtilis DB2 chromosome. The fusion was generated in this strain because integrating a fusion construct into amyE in B. subtilis F29-3 by recombination using pDH32 was found to be difficult. Our analysis showed that B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen105) grew faster than B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen105) and entered the early stationary phase 2 to 3 h sooner (Fig. 2A and Fig. 2B). The pattern of luciferase activity exhibited by this strain differed from that exhibited by B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen105). The luciferase activity of B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen105) increased during the log phase and reached a plateau during the late log phase (Fig. 2B). The activity then declined gradually during the early stationary phase, reaching a low point 10 h after inoculation (Fig. 2B). The activity increased again after 12 h, reaching a second peak 14 h following inoculation (Fig. 2B). The activity then decreased after 14 h. After 17 h of culturing, only basal levels of activity were observed (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Activity of fenp. nHA-Cm broth was inoculated with B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen105) (A) and B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen105) (B). Cells were cultured at 37°C, and the luciferase activity (filled circles) of the cells was monitored every hour for 32 h. The culture was aliquoted into test tubes following inoculation. The luciferase activity exhibited by the cells in three tubes at each sampling point was monitored using a luminometer. The relative light unit (RLU) values were averaged. The error bars indicate standard deviations. Cell growth (filled squares), expressed as A600, was monitored using a spectrophotometer.

Deletion analysis of fenp.

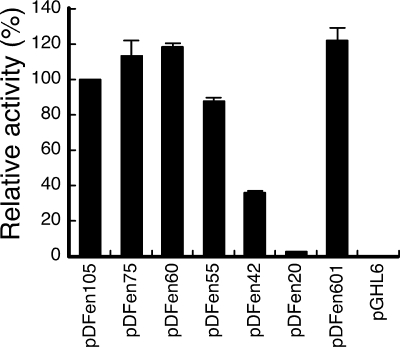

Plasmid pDFen105 was deleted to identify the region in fenp that was critical for transcription. Deleting the regions from position −105 to position −76 (pDFen75) and from position −105 to position −61 (pDFen60) did not substantially influence the promoter activity; 12 h following inoculation, the luciferase activities of B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen105), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen75), and B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen60) were approximately equal (Fig. 3). Deleting the promoter to position −56 (pDFen55) (Fig. 1) reduced the activity by 12.8% (Fig. 3). However, extending the deletion to position −43 (pDFen42) reduced the fenp activity by 64.5% (Fig. 1B and Fig. 3), indicating that the region between positions −55 and −43 is critical for fenp activity. Further deletion of the promoter to position −21 (pDFen20) (Fig. 1B) reduced the activity by 97.6% (Fig. 3), revealing that the region from position −42 to position −21, which includes the −35 box, is important for fenp activity. Additionally, deletion of the region between positions +1 and +80 from pDFen60 (pDFen601) did not affect the transcription (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Deletion analysis of fenp. nHA-Cm medium was inoculated with B. subtilis F92-3(pDFen105), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen75), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen60), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen55), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen42), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen20), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601), and B. subtilis F29-3(pGHL6). The cells were cultured at 37°C for 12 h. The luciferase activity values for the bacteria in three experiments were averaged, and levels of activity relative to that of B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen105) were calculated. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The relative light unit value for 100% activity was 2.1 × 106.

Mutations in fenp and promoter activity.

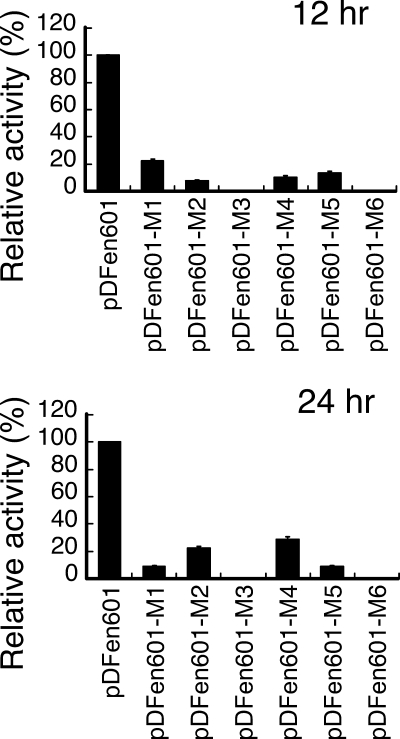

In this study, the regions from position −36 to position −31 and from position −11 to position −6 in pDFen601 were mutated to generate pDFen601-M5 and pDFen601-M6, respectively. At 12 and 24 h after inoculation, the luciferase activity of pDFen601-M5 was 85.4% and 94% lower than that of pDFen601 (Fig. 4), suggesting the importance of this segment of DNA in fenp transcription and confirming that this region contains the −35 box of fenp (29). The activity of pDFen601-M6 at 12 and 24 h following inoculation was reduced by 99.7% and 99.9%, respectively, confirming that the region from position −11 to position −6 contains the −10 box of fenp (29). Meanwhile, mutating the sequence between positions −55 and −39 (pDFen601-M1) reduced the transcription activity by 82.6% and 92.2% at 12 and 24 h (Fig. 4) after inoculation, respectively. In this study, mutations in this region from position −52 to position −50 (pDFen601-M2), from position −49 to position −47 (pDFen601-M3), and from position −42 to position −40 (pDFen601-M4) (Fig. 1B) were generated. The luciferase activities of the resulting plasmids 12 h after inoculation were reduced by 92.2%, 99.7%, and 89.7%, respectively, and the activities after 24 h were reduced by 77.8%, 99.7%, and 71.1%, respectively (Fig. 4). These results show the importance of the region between positions −55 and −39 for fenp transcription.

FIG. 4.

Mutations in the −35, −10, and UP element regions and transcription of fenp. nHA-Cm broth was inoculated with B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601-M1), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601-M2), B. subtilis F29-31(pDFen601-M3), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601-M4), B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601-M5), and B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601-M6). Luciferase activity was measured at 12 and 24 h after inoculation. The luciferase activity values for three experiments were averaged, and levels of activity relative that of B. subtilis F29-3(pDFen601) were calculated. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The relative light unit values for 100% activity at 12 and 24 h were 1.86 × 106 and 2.22 × 106, respectively.

Transcription of fenp from the chromosome of B. subtilis DB2.

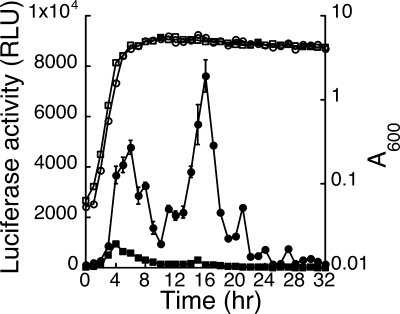

A fusion construct whose sequence was identical to that in pDFen601 was integrated into amyE in the B. subtilis DB2 chromosome. The resulting strain, B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601), exhibited an expression pattern (Fig. 5) similar to that of B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen105) (Fig. 2B). The luciferase activity of a mutant amyE::Pfen601-M1 construct, which contains a mutated sequence in the region between positions −55 and −39, was significantly lower than the activity exhibited by the amyE::Pfen601 fusion (Fig. 5), indicating the importance of the region between positions −55 and −39 for the transcription from fenp. At 6 and 16 h after inoculation, the luciferase activity of the amyE::Pfen601-M1 construct was 85.3% and 97.4% lower than that of the amyE::Pfen601 construct, respectively (Fig. 5). Despite the fact that the mutation substantially reduced the promoter activity, the expression pattern was similar to that exhibited by B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601) (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Transcription of fenp from fusion constructs in the chromosome of B. subtilis DB2. nHA-Cm broth was inoculated with B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601) (open circles) and B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601-M1) (open squares). Cells were cultured at 37°C. Cell growth, expressed as A600, was monitored using a spectrophotometer. The luciferase activities of B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601) (filled circles) and B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601-M1) (filled squares) were monitored every hour following inoculation. RLU, relative light units. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

In vitro transcription from fenp.

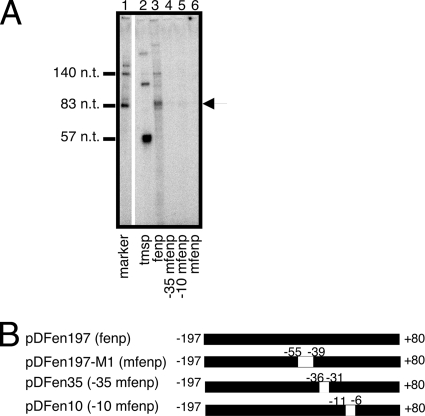

To investigate how the region between positions −55 and −39 regulates the transcription of fenp, in vitro transcription was performed using a DNA template that covered the sequence between positions −197 and +80 (Fig. 6B). Additionally, the reverse primer that was used to amplify the DNA fragment contained a KpnI site and a GGCC sequence at the 5′ terminus. Hence, a 90-nt RNA should be transcribed from fenp. In this study, transcripts transcribed from the tms (20) and T7 promoters were used as size markers (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 and 2). The results showed that a 90-nt transcript was transcribed from a DNA template that contained the wild-type fenp sequence. The transcription of this 90-nt transcript was significantly reduced after the region between positions −55 and −39 was mutated (Fig. 6A, lane 6). As expected, mutations in the −35 and −10 regions also markedly reduced the transcription (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 and 5).

FIG. 6.

In vitro transcription. (A) A DNA fragment that contained the region from position −197 to position +80 was used for in vitro transcription. The transcript from fenp was 90 nt long (arrowhead). In vitro transcription was also performed using DNA fragments that covered the same region but with a mutation at position −35 (−35 mfenp) (lane 4) or −10 (−10 mfenp) (lane 5) or in the region between positions −55 and −39 (mfenp) (lane 6). The DNA fragments were amplified using pDFen35, pDFen10, and pDFen197-M1 as templates, respectively. The tmsp transcript was 57 nt long and was used as a control. mfenp is a mutant template that is similar to fenp but in which the UP sequence is mutated. The 140-nt and 83-nt transcripts were transcribed from a T7 promoter. (B) Maps of fenp, mfenp, −35 mfenp, and −10 mfenp.

Binding of αCTD to the region between positions −55 and −39.

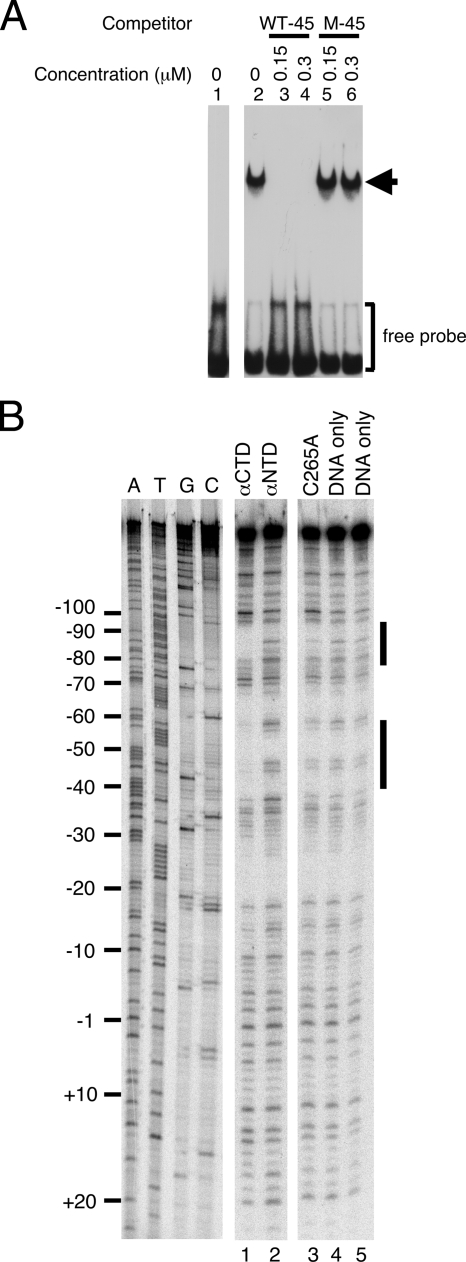

The region from position −55 to position −39 in fenp is A and T rich and therefore partially homologous to the corresponding region of the UP element in the rrnB P1 promoter (16, 38). Since αCTD binds to the UP element in the rrnB P1 promoter, EMSA was employed here to confirm the binding of His-αCTD to the region upstream of the −35 box in fenp. EMSA revealed that 4 μM His-αCTD shifted a 40-bp biotin-labeled probe, WT-45, which contains the sequence between positions −39 and −55, in a gel (Fig. 7A, lanes 1 and 2). However, the protein no longer shifted the DNA when 0.15 or 0.3 μM non-biotin-labeled probe WT-45 was added as a competitor (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 and 4). Meanwhile, adding a G-and C-rich probe, M-45, did not influence the binding of the protein to the WT-45 probe (Fig. 7A, lanes 5 and 6).

FIG. 7.

Binding of His-αCTD to fenp. (A) EMSA was performed using His-αCTD and biotin-labeled probes that contained the sequence between positions −65 and −26 in fenp (WT-45). Probe M-45, with a G- and C-rich sequence, was used as a nonspecific competitor. (B) DNase I footprinting was performed using a 32P-labeled DNA probe that contained the sequence from position −147 to position +50. His-αCTD (lane 1), His-αNTD (lane 2), and His-αCTD(C265A) (lane 3) were incubated with the probe. After the DNA was digested with DNase I, DNA was analyzed using a sequencing gel. Lanes A, T, G, and C contained the dideoxynucleotides that were used in sequencing reactions. A reaction mixture without His-αCTD, His-αNTD, or His-αCTD(C265A) added (lanes 4 and 5) was cleaved by DNase I and used as a control.

Analysis of binding of αCTD to fenp by DNase I footprinting analysis.

A DNase I footprinting study revealed that His-αCTD protected the regions from position −97 to position −81 and from position −60 to position −39 (Fig. 7B, lane 1). However, these two regions were not protected by His-αNTD (Fig. 7B, lane 2) or by an αCTD mutant, His-αCTD(C265A), which was demonstrated to be unable to bind to the UP element (Fig. 7B, lane 3) (17). These results demonstrated that the region between positions −55 and −39 may contain an UP element. Additionally, the presence of two αCTD-binding sites is not unique to fenp; the presence of two protected regions in several promoters was also revealed by DNase I footprinting analysis (2, 18, 25, 35). Although the site close to the −35 box has the strongest effect on transcription, the function of the distal binding site remains unclear (25, 35).

Effect of mutation in the UP element on transcription of the fen operon and the synthesis of fengycin by B. subtilis F29-3.

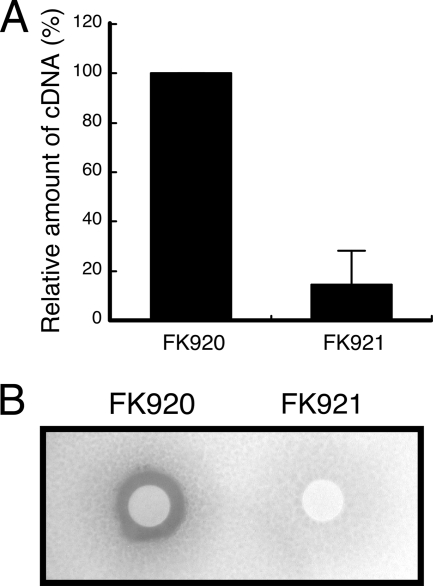

A mutant B. subtilis F29-3 strain, FK921, which contains a chloramphenicol resistance gene inserted at position −197 and a mutated UP element, and another mutant, FK920, which contains the chloramphenicol resistance gene inserted at position −197 in the wild-type promoter, were tested to determine their capacity to transcribe the fen operon and produce fengycin. The cells were cultured in nHA-Cm broth to the mid-log phase. The fen mRNA in the cells was determined by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR using primers that amplified the region between positions +807 and +1113 in the fen operon. A segment of rpoA was also amplified and used as an internal control. The mean ΔCT value obtained from amplification of FK920 and FK921 fen mRNA in three independent experiments was normalized with the ΔCT value of the internal control. The results indicated that the amount of fen mRNA that was transcribed by FK921 was 85.4% or about seven times lower than the amount transcribed by FK920 (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, FK920 produced fengycin in the medium after 24 h of culturing. The amount of fengycin produced by this strain suppressed the germination of fungal spores (Fig. 8B). However, mutant strain FK921 did not produce sufficient fengycin to inhibit spore germination (Fig. 8B), indicating that the UP element in fenp is critical for the synthesis of fengycin. The experiments described here were conducted using mutants that had been generated in three independent mutagenesis experiments, indicating that the lack of fengycin production by FK921 is not associated with possible mutations in any sequence that is not related to the UP element.

FIG. 8.

Effect of mutation in the UP element in fenp in the B. subtilis F29-3 chromosome on the transcription of the fen operon and the production of fengycin. Two mutants of B. subtilis F29-3, FK920 and FK921, were cultured in nHA broth to the mid-log phase. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR was used to determine the CT values for amplification of a segment of fenC mRNA. A segment of rpoA was amplified as the internal control. The percentages of the amount of cDNA were calculated from the CT values (A). The cells were also cultured for 24 h in nHA broth. The culture medium was spotted on a filter paper disk on a spore plate to assay the fengycin produced by the two mutant strains. The background shows the growth of fungal mycelium; the halo around the paper disk where mycelium is not present indicates inhibition of spore germination by fengycin (B).

DISCUSSION

Fengycin is synthesized nonribosomally by five fengycin synthetases that are encoded by the fen operon (29, 48). Efficient and correct timing of fengycin expression are, therefore, critical for the survival of B. subtilis F29-3 in an ecosystem. The aim of this work was to elucidate the regulation of the transcription of the fen operon. A previous study found that the transcription start site of the fen operon is located 86 nt upstream of the translation initiation codon of the first gene in the operon, fenC (29). That study also determined that the −35 and −10 boxes are located at position −36 to position −31 and at position −11 to position −6, respectively. Accordingly, in this study, a transcriptional fusion with DNA fragments in the promoter region was constructed to investigate the manner in which the transcription of fenp is regulated. Analysis of the luciferase activity of B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen105) and B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601) revealed identical expression patterns; transcription by either strain peaks in the late log phase and 14 to 16 h following inoculation in the stationary phase (Fig. 2B and Fig. 5). However, the luciferase activity exhibited by B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601) (Fig. 5) is about five to seven times higher than that exhibited by B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen105) (Fig. 2B) during the first 20 h of culturing. Since the amyE::Pfen601 construct lacks the regions from position −105 to position −61 and from position +1 to position +80, the increased luciferase activity of B. subtilis DB2(amyE::Pfen601) suggests that a negative element may be present in one of these two regions. However, the repression was less obvious when the fusions were in a reporter plasmid than when they were in the chromosome (Fig. 2B). Since pDFen601 has a pC194 ori and a copy number of about 30 (50), B. subtilis F29-3 may not yield enough of the repressor to suppress the transcription from the plasmids. The function of the negative element is now under investigation.

The UP element, which is a 17-bp A- and T-rich sequence located upstream of the −35 box in a promoter (11, 16, 17, 38), is a docking site for αCTD in RNA polymerase (22). This sequence enhanced transcription of the E. coli rrnB P1 promoter (38, 39) and various B. subtilis genes, including spoVG (4), the autolysin gene, cwlB (32), the flagellin gene, hag (5), and genes in Bacillus phage φ29 (32). Additionally, enhancement by the UP element is not limited to the promoters of the σA type but extends to the promoters that are recognized by σD and σH (15, 19). Although the sequence upstream of the −35 region in σA-type promoters is generally enriched for short A and T tracts, only a few promoters contain an UP element (5). This study shows that an UP element between positions −55 and −39 strongly activates the transcription of fenp since mutating this sequence markedly reduces the transcription from fenp in a plasmid and in the chromosome (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, and Fig. 8A). This sequence is likely to be an UP element since EMSA and DNase I footprinting revealed binding of αCTD to this segment of DNA (Fig. 7). Moreover, fenp in the B. subtilis DB2 chromosome is transcribed at two distinct stages of cell growth, the log phase and the stationary phase (Fig. 2B and Fig. 5). The transcription in both of these phases is reduced markedly when the UP element is mutated (Fig. 5), indicating the importance of the UP element in transcription. Our results also showed that mutations in different regions in the UP element, between positions −52 and −50 (pDFen601-M2), positions −49 and −47 (pDFen601-M3), and positions −42 and −40 (pDFen601-M4), substantially reduce the promoter activity (Fig. 4), indicating that binding of two αCTDs to the proximal and distal parts of the UP element simultaneously is critical for activation (12, 18).

This study demonstrates that the fengycin synthetase operon is transcribed during the log phase and peaks when the cells reach the late log phase (Fig. 5). After the activity decreases, the transcriptional activity increases again and reaches a second peak at 14 to 16 h (Fig. 5). The transcription in these two stages of cell growth is probably driven by the same promoter since the transcription throughout culturing decreased substantially after mutation of the −35 and −10 boxes, implying that the sequences that are required for transcription during both the log phase and the stationary phase are common. Additionally, functioning of an UP element depends on the proper distance from the −35 box (11). The fact that mutation of the UP element reduces the transcription during both the log and stationary phases (Fig. 4) also strongly suggests that a common −35 sequence is involved in transcription in these two phases. If this is true, factors must repress the transcription in the early stationary phase and after 16 h of culturing (Fig. 5). This study also found that pDFen105 in a spo0A mutant has a transcriptional pattern that is similar to that of B. subtilis 168(pDFen105) (data not shown), indicating that the sporulation genes probably do not regulate the transcription of the fen operon.

According to our results, the UP element between positions −55 and −39 in fenp is critical for fengycin synthesis since a B. subtilis F29-3 mutant with a mutated UP element in fenp cannot transcribe the fen operon efficiently or produce sufficient fengycin to inhibit the germination of fungal spores (Fig. 8). Since factors other than the UP element may regulate the transcription of the fengycin synthetase operon, further work must be performed to elucidate fully how these factors affect the synthesis of fengycin.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Hoch for transforming pDFen105 into a spo0A mutant strain.

This work was supported by grants from Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital (grant CMRPD170251), Chang-Gung Research Center of Bacterial Pathogenesis, and the National Science Council of the Republic of China (grant NSC 90-2320-B-182-063).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., S. Adhya, and B. de Crombrugghe. 1981. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 25611905-11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiyar, S. E., R. L. Gourse, and W. Ross. 1998. Upstream A-tracts increase bacterial promoter activity through interactions with the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9514652-14657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asanuma, K., N. Tsuji, T. Endoh, A. Yagihashi, and N. Watanabe. 2004. Survivin enhances Fas ligand expression via up-regulation of specificity protein 1-mediated gene transcription in colon cancer cells. J. Immunol. 1723922-3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banner, C. D., C. P. Moran, Jr., and R. Losick. 1983. Deletion analysis of a complex promoter for a developmentally regulated gene from Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 168351-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caramori, T., and A. Galizzi. 1998. The UP element of the promoter for the flagellin gene, hag, stimulates transcription from both SigD- and SigA-dependent promoters in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 258385-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, B. Y., K. Y. Chen, Y. D. Wen, and C. T. Liao. 1994. The response of a Bacillus subtilis temperature-sensitive sigA mutant to heat stress. J. Bacteriol. 1763102-3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, L. K., C. L. Chen, Y. S. Chang, J. S. Tschen, Y. M. Chen, and S. T. Liu. 1994. Construction of Tn917ac1, a transposon useful for mutagenesis and cloning of Bacillus subtilis genes. Gene 150129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, C. L., L. K. Chang, Y. S. Chang, S. T. Liu, and J. S. Tschen. 1995. Transposon mutagenesis and cloning of the genes encoding the enzymes of fengycin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clugston, S. L., S. A. Sieber, M. A. Marahiel, and C. T. Walsh. 2003. Chirality of peptide bond-forming condensation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases: the C5 domain of tyrocidine synthetase is a (D)C(L) catalyst. Biochemistry 4212095-12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conti, E., T. Stachelhaus, M. A. Marahiel, and P. Brick. 1997. Structural basis for the activation of phenylalanine in the non-ribosomal biosynthesis of gramicidin S. EMBO J. 164174-4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estrem, S. T., T. Gaal, W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 1998. Identification of an UP element consensus sequence for bacterial promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 959761-9766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estrem, S. T., W. Ross, T. Gaal, Z. W. Chen, W. Niu, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1999. Bacterial promoter architecture: subsite structure of UP elements and interactions with the carboxy-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Genes Dev. 132134-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finking, R., and M. A. Marahiel. 2004. Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58453-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleige, S., V. Walf, S. Huch, C. Prgomet, J. Sehm, and M. W. Pfaffl. 2006. Comparison of relative mRNA quantification models and the impact of RNA integrity in quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Biotechnol. Lett. 281601-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fredrick, K., T. Caramori, Y. F. Chen, A. Galizzi, and J. D. Helmann. 1995. Promoter architecture in the flagellar regulon of Bacillus subtilis: high-level expression of flagellin by the sigma D RNA polymerase requires an upstream promoter element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 922582-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaal, T., L. Rao, S. T. Estrem, J. Yang, R. M. Wartell, and R. L. Gourse. 1994. Localization of the intrinsically bent DNA region upstream of the E. coli rrnB P1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 222344-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaal, T., W. Ross, E. E. Blatter, H. Tang, X. Jia, V. V. Krishnan, N. Assa-Munt, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1996. DNA-binding determinants of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase: novel DNA-binding domain architecture. Genes Dev. 1016-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gourse, R. L., W. Ross, and T. Gaal. 2000. UPs and downs in bacterial transcription initiation: the role of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase in promoter recognition. Mol. Microbiol. 37687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmann, J. D. 1995. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma A-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 232351-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilden, I., B. N. Krath, and B. Hove-Jensen. 1995. Tricistronic operon expression of the genes gcaD (tms), which encodes N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate uridyltransferase, prs, which encodes phosphoribosyl diphosphate synthetase, and ctc in vegetative cells of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1777280-7284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu, H. H., W. C. Huang, J. P. Chen, L. Y. Huang, C. F. Wu, and B. Y. Chang. 2004. Properties of Bacillus subtilis sigma A factors with region 1.1 and the conserved Arg-103 at the N terminus of region 1.2 deleted. J. Bacteriol. 1862366-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeon, Y. H., T. Negishi, M. Shirakawa, T. Yamazaki, N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and Y. Kyogoku. 1995. Solution structure of the activator contact domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Science 2701495-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, S. I., Y. S. Nam, and S. Y. Lee. 1997. Improvement of the production of foreign proteins using a heterologous secretion vector system in Bacillus subtilis: effects of resistance to glucose-mediated catabolite repression. Mol. Cells 7788-794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koglin, A., F. Lohr, F. Bernhard, V. V. Rogov, D. P. Frueh, E. R. Strieter, M. R. Mofid, P. Guntert, G. Wagner, C. T. Walsh, M. A. Marahiel, and V. Dotsch. 2008. Structural basis for the selectivity of the external thioesterase of the surfactin synthetase. Nature 454907-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolb, A., K. Igarashi, A. Ishihama, M. Lavigne, M. Buckle, and H. Buc. 1993. E. coli RNA polymerase, deleted in the C-terminal part of its alpha-subunit, interacts differently with the cAMP-CRP complex at the lacP1 and at the galP1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 21319-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopp, F., U. Linne, M. Oberthur, and M. A. Marahiel. 2008. Harnessing the chemical activation inherent to carrier protein-bound thioesters for the characterization of lipopeptide fatty acid tailoring enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1302656-2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambalot, R. H., A. M. Gehring, R. S. Flugel, P. Zuber, M. LaCelle, M. A. Marahiel, R. Reid, C. Khosla, and C. T. Walsh. 1996. A new enzyme superfamily—the phosphopantetheinyl transferases. Chem. Biol. 3923-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin, G. H., C. L. Chen, J. S. Tschen, S. S. Tsay, Y. S. Chang, and S. T. Liu. 1998. Molecular cloning and characterization of fengycin synthetase gene fenB from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1801338-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, T. P., C. L. Chen, L. K. Chang, J. S. Tschen, and S. T. Liu. 1999. Functional and transcriptional analyses of a fengycin synthetase gene, fenC, from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1815060-5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, T. P., C. L. Chen, H. C. Fu, C. Y. Wu, G. H. Lin, S. H. Huang, L. K. Chang, and S. T. Liu. 2005. Functional analysis of fengycin synthetase FenD. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1730159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo, L., R. M. Kohli, M. Onishi, U. Linne, M. A. Marahiel, and C. T. Walsh. 2002. Timing of epimerization and condensation reactions in nonribosomal peptide assembly lines: kinetic analysis of phenylalanine activating elongation modules of tyrocidine synthetase B. Biochemistry 419184-9196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meijer, W. J., and M. Salas. 2004. Relevance of UP elements for three strong Bacillus subtilis phage phi29 promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 321166-1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 34.Nelson, R. M., and G. L. Long. 1989. A general method of site-specific mutagenesis using a modification of the Thermus aquaticus polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 180147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newlands, J. T., C. A. Josaitis, W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 1992. Both fis-dependent and factor-independent upstream activation of the rrnB P1 promoter are face of the helix dependent. Nucleic Acids Res. 20719-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noel, R. J., Jr., and W. S. Reznikoff. 1998. CAP, the −45 region, and RNA polymerase: three partners in transcription initiation at lacP1 in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 282495-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan, S. H., and B. A. Malcolm. 2000. Reduced background expression and improved plasmid stability with pET vectors in BL21(DE3). BioTechniques 291234-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao, L., W. Ross, J. A. Appleman, T. Gaal, S. Leirmo, P. J. Schlax, M. T. Record, Jr., and R. L. Gourse. 1994. Factor independent activation of rrnB P1. An “extended” promoter with an upstream element that dramatically increases promoter strength. J. Mol. Biol. 2351421-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross, W., K. K. Gosink, J. Salomon, K. Igarashi, C. Zou, A. Ishihama, K. Severinov, and R. L. Gourse. 1993. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 2621407-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlumbohm, W., T. Stein, C. Ullrich, J. Vater, M. Krause, M. A. Marahiel, V. Kruft, and B. Wittmann-Liebold. 1991. An active serine is involved in covalent substrate amino acid binding at each reaction center of gramicidin S synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 26623135-23141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shu, H. Y., G. H. Lin, Y. C. Wu, J. S. Tschen, and S. T. Liu. 2002. Amino acids activated by fengycin synthetase FenE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292789-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sieber, S. A., and M. A. Marahiel. 2003. Learning from nature's drug factories: nonribosomal synthesis of macrocyclic peptides. J. Bacteriol. 1857036-7043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stachelhaus, T., A. Huser, and M. A. Marahiel. 1996. Biochemical characterization of peptidyl carrier protein (PCP), the thiolation domain of multifunctional peptide synthetases. Chem. Biol. 3913-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stachelhaus, T., and M. A. Marahiel. 1995. Modular structure of genes encoding multifunctional peptide synthetases required for non-ribosomal peptide synthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1253-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein, T., J. Vater, V. Kruft, A. Otto, B. Wittmann-Liebold, P. Franke, M. Panico, R. McDowell, and H. R. Morris. 1996. The multiple carrier model of nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis at modular multienzymatic templates. J. Biol. Chem. 27115428-15435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanovic, A., S. A. Samel, L. O. Essen, and M. A. Marahiel. 2008. Crystal structure of the termination module of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Science 321659-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanittanakom, N., W. Loeffler, U. Koch, and G. Jung. 1986. Fengycin—a novel antifungal lipopeptide antibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis F-29-3. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 39888-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu, C. Y., C. L. Chen, Y. H. Lee, Y. C. Cheng, Y. C. Wu, H. Y. Shu, F. Gotz, and S. T. Liu. 2007. Nonribosomal synthesis of fengycin on an enzyme complex formed by fengycin synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 2825608-5616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamanaka, K., J. Araki, M. Takano, and J. Sekiguchi. 1997. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis mutants resistant to cold shock-induced autolysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 150269-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yokoyama, E., Y. Matsuzaki, K. Doi, and S. Ogata. 1998. Gene encoding a replication initiator protein and replication origin of conjugative plasmid pSA1.1 of Streptomyces cyaneus ATCC 14921. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 169103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yonus, H., P. Neumann, S. Zimmermann, J. J. May, M. A. Marahiel, and M. T. Stubbs. 2008. Crystal structure of DltA: implications for the reaction mechanism of non-ribosomal peptide synthetase adenylation domains. J. Biol. Chem. 4732484-32491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zähner, H., and W. K. Maas. 1972. Biology of antibiotics. Springer, New York, NY.

- 53.Zhang, Y., S. Nakano, S. Y. Choi, and P. Zuber. 2006. Mutational analysis of the Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase alpha C-terminal domain supports the interference model of Spx-dependent repression. J. Bacteriol. 1884300-4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]