Abstract

In gram-positive bacteria, oligopeptide transport systems, called Opp or Ami, play a role in nutrition but are also involved in the internalization of signaling peptides that take part in the functioning of quorum-sensing pathways. Our objective was to reveal functions that are controlled by Ami via quorum-sensing mechanisms in Streptococcus thermophilus, a nonpathogenic bacterium widely used in dairy technology in association with other bacteria. Using a label-free proteomic approach combining one-dimensional electrophoresis with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis, we compared the proteome of the S. thermophilus LMD-9 to that of a mutant deleted for the subunits C, D, and E of the ami operon. Both strains were grown in a chemically defined medium (CDM) without peptides. We focused our attention on proteins that were no more detected in the ami deletion mutant. In addition to the three subunits of the Ami transporter, 17 proteins fulfilled this criterion and, among them, 7 were similar to proteins that have been identified as essential for transformation in S. pneumoniae. These results led us to find a condition of growth, the early exponential state in CDM, that allows natural transformation in S. thermophilus LMD-9 to turn on spontaneously. Cells were not competent in M17 rich medium. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the Ami transporter controls the triggering of the competence state through the control of the transcription of comX, itself controlling the transcription of late competence genes. We also showed that one of the two oligopeptide-binding proteins of strain LMD-9 plays the predominant role in the control of competence.

Many species of bacteria control gene expression on a community-wide scale by producing, secreting, detecting, and responding to extracellular signaling molecules (sometimes called “autoinducers” or “pheromones”) that accumulate in the environment. This phenomenon is termed “quorum sensing” (QS) as gene expression is triggered by the “sensing” of the pheromone when its concentration has reached a “quorum.” In gram-positive bacteria, the signaling molecules are mainly short peptides acting either from the outside part of bacteria or from the inside, after internalization via oligopeptide transport systems called Opp or Ami (40, 41).

Several bacterial functions such as the virulence in Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis, the competence in Bacillus subtilis or the production of bacteriocin in Lactococcus lactis are controlled by peptides acting at the surface of bacteria and detected by histidine kinases of two-component systems (TCSs) (32, 38).

Concerning signaling peptides that are active after internalization by an oligopeptide transporter, three groups have been described in detail: (i) Phr peptides in B. subtilis involved in the control of sporulation, competence, conjugation, and production of degradative enzymes and antibiotics (1, 35); (ii) PapR peptides involved in the control of virulence of bacteria belonging to the Bacillus cereus group (37); and (iii) peptides involved in the control of plasmid transfer in E. faecalis (24). All of these extracellular short peptides interact with either Rap proteins (in B. subtilis) or transcriptional regulators (PlcR in B. cereus or PrgX in E. faecalis) to elicit a physiological response.

Oligopeptide transport systems involved in these signaling pathways belong to the superfamily of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. They are composed of five subunits: an extracellular oligopeptide-binding protein, OppA, that specifically captures the substrates; two transmembrane proteins, OppB and OppC, that form the pore; and two membrane-bound cytoplasmic ATP-binding proteins, OppD and OppF, that provide the energy for peptide translocation. Several copies of the opp operon and/or of the genes encoding the oligopeptide-binding proteins can be present in a single genome (30). The genome of Streptococcus thermophilus encodes one oligopeptide transport system and depending on the strain, two (strain LMD-9 and CNRZ1066) or three (strain LMG18311) oligopeptide-binding proteins. The presence of several copies of oligopeptide-binding proteins is frequent in bacteria, but the reason for this redundancy is not yet understood (30). In gram-positive bacteria, two main functions have been attributed to the Opp transporters: nutrition and sensing. The nutritional role has been well studied in lactic acid bacteria such as L. lactis or S. thermophilus. During growth in milk, the Opp transporters supply these auxotrophic bacteria with peptides that serve as amino acid sources (7, 16, 34). Overlapping specificities for milk peptide binding was demonstrated for three homologous AmiAs in another S. thermophilus strain (16). The sensing function is more complex and is poorly documented, particularly in nonpathogenic bacteria.

S. thermophilus is of major importance for the food industry since it is massively used for the manufacture of yogurt and Swiss or Italian-type cheeses. Only one QS system, involving a pheromone detected by a TCS, has been described in this bacterium where it controls the production of a bacteriocin (15). The sequencing of the genome of three strains of S. thermophilus—CNRZ1066, LMG18311, and LMD-9—has revealed the presence of late competence genes encoding 14 proteins with strong similarities to the 14 proteins known to be required for competence in S. pneumoniae (5, 19) and of comX encoding a competence-specific σ factor that controls their expression. Except comX, no orthologs of the early competence genes of S. pneumoniae involved in the QS mechanism that controls the expression of this σ factor have been detected in the genome of S. thermophilus. Moreover, it has been shown that overexpression of comX induces the competent state in S. thermophilus LMG18311 (4). Still, how transformation is turned on in this strain and what regulatory pathway controls the expression of comX have not previously been explained.

We have recently discovered a new QS system in S. thermophilus LMD-9 involving a transcriptional regulator of the Rgg family, Rgg1358, and a pheromone corresponding to a small hydrophobic peptide (SHP) imported by the oligopeptide Ami transport system. The target of this QS mechanism is a small gene whose transcription is drastically decreased in mutants deleted for shp, rgg1358, or amiCDE (20). Furthermore, the genes shp and rgg1358 are genetically linked, and we have found seven other copies of shp-rgg pairs in S. thermophilus genomes. (20, 21). These results led us to propose that Ami could be involved in the import of several pheromones in S. thermophilus. In order to identify functions that are controlled by Ami via QS mechanisms, we compared the proteome of S. thermophilus LMD-9 to that of a mutant with the ami operon deleted (ΔamiCDE) in a peptide-free medium. Most of the proteins that were not detected in the ΔamiCDE mutant were linked to competence. Our proteomic approach led us to discover that the Ami transporter controls the transcription of the genes encoding these proteins via the control of the transcription of comX. Moreover, we demonstrated that S. thermophilus LMD-9 spontaneously turns on natural competence in a chemically defined medium (CDM).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. S. thermophilus strains were grown at 28 or 42°C in M17 medium (Difco) supplemented with 10 g of lactose (M17lac) liter−1 or in a CDM, containing only amino acids as nitrogen source, as described by Letort and Juillard (26). E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth with shaking (36). Agar (1.5%) was added to the media when needed. When required, antibiotics were added to the media at the following final concentrations: erythromycin at 250 μg ml−1 for E. coli or 5 μg ml−1 for S. thermophilus and kanamycin at 1 mg ml−1 for S. thermophilus. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the cultures was measured by using a spectrophotometer Uvikon 931 (Kontron).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant property | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. thermophilus | ||

| LMD-9 | Wild type | 28 |

| CNRZ1066 | Wild type | 5 |

| LMG18311 | Wild type | 5 |

| TIL883 | LMD-9 ΔamiCDE | 20 |

| TIL1192 | LMD-9 feoB::erm | This study |

| TIL1193 | LMD-9 feoB::aphA3 | This study |

| TIL1195 | LMD-9 comEC::erm | This study |

| TIL1196 | LMD-9 comX::erm | This study |

| TIL1197 | LMD-9 amiA3::erm | This study |

| TIL1198 | LMD-9 ΔamiA1 | This study |

| TIL1199 | LMD-9 ΔamiA1 amiA3::erm | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| TG1 repA+ | TG1 derivative with repA gene integrated into the chromosome | 17; P. Renaulta |

| Plasmid | ||

| pG+host9 | Thermosensitive plasmid, Eryr | 3 |

INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France.

Preparation of extracts enriched in cell envelope proteins.

Proteins were prepared from 250 ml of cells grown in CDM and harvested at an OD600 of 0.7 in two independent cultures for each strain. Bacteria resuspended in 4 ml of a phosphate buffer were mechanically disrupted as previously described (18), and the supernatants were ultracentrifuged at 220,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to enrich the “cell envelope pellets” in cell envelope proteins. This fraction also contained cytoplasmic proteins, especially those associated in complexes. Finally, the pellet were resuspended in 200 μl of a disruption buffer and sonicated for 15 min at 4°C in an ultrasonic bath.

Separation and identification of proteins by 1D sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis coupled to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

Proteins of the cell envelope pellet fractions (10 μg) were separated by one-dimensional (1D) electrophoresis as previously described (21). Each 1D electrophoresis lane was cut into 26 pieces of gel (2 mm in width). In-gel digestion of the proteins was performed with the Progest system (Genomic Solution) according to the following protocol. Gel pieces were washed first, in two successive baths of (i) 10% acetic acid-40% ethanol and (ii) 100% acetonitrile (ACN) and, second, in two successive baths of (i) 25 mM NH4CO3 and (ii) 100% ACN. A total of 40 μl was used for each bath. Gel pieces were further incubated in 40 μl of 10 mM dithiothreitol in 25 mM NH4CO3 for 30 min at 55°C and in 30 μl of 50 mM iodoacetamide in 25 mM NH4CO3 for 45 min at room temperature for cysteine reduction and alkylation, respectively. Digestion was subsequently performed for 6 h at 37°C with 20 μl of 125 ng of modified trypsin (Promega) dissolved in 20% methanol and 20 mM NH4CO3 per gel piece. The peptides were extracted successively with (i) 20 μl of 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid-50% ACN and (ii) with 20 μl of 100% ACN. The resulting peptide extracts were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and suspended in 25 μl of 0.08% trifluoroacetic acid and 2% ACN prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on Ultimate 3000 LC system (Dionex, Voisins le Bretonneux, France) connected to LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) by nanoelectrospray ion source. Tryptic peptide mixtures (4 μl) were loaded at flow rate 20 μl min−1 onto precolumn Pepmap C18 (0.3 by 5 mm, 100 Å, 5 μm; Dionex). After 4 min, the precolumn was connected with the separating nanocolumn Pepmap C18 (0.075 by 15 cm, 100Å, 3 μm), and the linear gradient was started from 2 to 36% of buffer B (0.1% formic acid, 80% ACN) in buffer A (0.1% formic acid, 2% ACN) at 300 nl min−1 over 50 min. Ionization was performed on liquid junction with a spray voltage of 1.3 kV applied to an uncoated capillary probe (PicoTip EMITER 10-μm tip inner diameter; New Objective). Peptides ions were automatically analyzed by the data-dependent method as follows: full MS scan (m/z 300 to 1,600) on Orbitrap analyzer and MS/MS on the four most abundant precursor on the LTQ linear ion trap. In the present study only +2 and +3 charged peptides were subjected to MS/MS experiments with an exclusion window of 1.5 min, with classical peptide fragmentation parameters as follows: Qz = 0.22, activation time = 50 ms, and collision energy = 35%.

The raw data produced on LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer were first converted in mzXML file with ReADW (http://sashimi.sourceforge.net) and, in a second step, protein identification was performed with X!Tandem software (X!Tandem tornado 2008.02.01.3 [http://www.thegpm.org]) against a protein database of S. thermophilus LMD-9 (GenBank no. CP000419.1), associated to a proteomic contaminant database. The X!Tandem search parameters were as follows: trypsin specificity with one missed cleavage, fixed alkylation of cysteine, and variable oxidation of methionine. The mass tolerance was fixed to 10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.5 Da for fragment ions. For all proteins identified with a protein E-value of <0.01 in the first step, we searched for additional peptides to reinforce identification using similar parameters except that semitryptic peptides and protein N-terminal acetylations were accepted. All peptides identified with an E-value of <0.1 were conserved. All results for each piece of gel were merged with a homemade program written in java by Benoit Valot (PAPPSO platform, INRA [http://moulon.inra.fr/PAPPSO]). The final search results were filtered by using a multiple threshold filter applied at the protein level and consisting of a protein E-value of <10−8 identified with a minimum of two different peptides sequences, detected in at least one piece of gel, with a peptide E-value of <0.05.

Relative quantification of proteins.

For relative quantification of proteins, we used the number of spectra obtained during protein identification by MS. The number of spectra was already shown to be proportional to the abundance of a given protein (42). For each protein detected, we calculated an abundance factor derived from the protein abundance index (PAI) developed in Mathias Mann's group (22). The calculation consists in normalizing, for each protein, the observed spectra number by the theoretical number of peptides released after trypsin hydrolysis and detectable by MS, i.e., having a mass ranging between 800 and 2,500 Da. Therefore, the abundance factor represents the relative abundance of a given protein taking into account its mass.

Proteins that were detected in the two repetitions performed for strain LMD-9 and not detected in any of the two repetitions performed for strain TIL883 (abundance factor = 0) were taken into account.

Natural transformation of S. thermophilus LMD-9.

S. thermophilus LMD-9 cells were grown overnight at 42°C in CDM. The culture was then diluted in CDM at an OD600 0.05. 2 ml of this diluted culture were distributed in 2-ml tubes and incubated in a water bath at 42°C. At different times depending on the kinetics, a sample was used to measure the OD600, and 100 μl was mixed with 1 μg of DNA, followed by incubation for 2 h at 28°C when mixed with a thermosensitive replicative plasmid DNA or at 42°C when mixed with chromosomal DNA or PCR fragments, before being serially diluted and spread on M17lac plates with the appropriate antibiotic. To assess the transformation rate or to construct mutants, only one sample of the diluted culture in CDM incubated 1 h at 42°C was used. To calculate the transformation rate, i.e., the number of antibiotic-resistant transformants per ml divided by the number of viable CFU per ml, cells were also spread on M17lac plates. All of these experiments were repeated at least three times. After transformation experiments, the presence of the plasmid pG+host9 in bacteria was checked on several colonies by PCR. At the optimum of competence, no erythromycin- or kanamycin-resistant clones were observed during transformation experiments with the wild-type strain when water was used as a control.

DNA manipulations.

Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs), and Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The oligonucleotides were purchased from Eurogentec. PCR amplifications were carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 2720 (Applied Biosystems) using the oligonucleotides presented in Table 2. All amplified fragments were purified either with a QIAquick PCR purification kit or from 0.7% agarose gel with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Plasmids were extracted by QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen). DNA sequences were determined on an ABI Prism 310 automated DNA sequencer using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Preparation of electrocompetent cells of S. thermophilus LMD-9 was performed as previously described (20). Chromosomal DNA was purified as follows. Briefly, cells from 10 ml of overnight culture were suspended in 2.5 ml of lysis solution (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 25% sucrose, 10 mg of lysozyme/ml [freshly added]) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Then, 250 μ1 of 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 70 μ1 of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) were added prior to 2 h of incubation at 55°C. Cell wall debris, denatured proteins, and polysaccharides were precipitated by adding 225 μ1 of 5 M sodium chloride. The mixture was then chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extracted once, and DNA was precipitated by adding a 0.6 volume of isopropanol and gently inverting the tube. The DNA pellet recovered by brief centrifugation was washed in 70% ethanol, dried, suspended in 300 μ1 of 10 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5)-RNase (100 μg/ml), and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Finally, DNA was dialyzed against water overnight.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|

| Mutant constructions | |

| ermF | GGGACCTCTTTAGCTCCTTGG |

| ermR | GGAGATAAGACGGTTCGTGTTCG |

| aphA3F | CCAGCGAACCATTTGAG |

| aphA3R | GTTGCGGATGTACTTCAG |

| feo-1 | GTAGGTCAAGAAAGATG |

| feo-2 | CTACTGACAGCTTCCAAGGAGCTAAAGAGGTCCCCGCAGACCTTTGTGGCA |

| feo-3 | GCAAGTCAGCACGAACACGAACCGTCTTATCTCCATGAAAGGGATCGTCGG |

| feo-4 | CGGGCAAGAGCACTCAC |

| feo-5 | TATTACGGAAAAGATGG |

| feo-6 | GACATCTAATCTTTTCTGAAGTACATCCGCAACCGCAGACCTTTGTGGCA |

| feo-7 | ATAATCTTACCTATCACCTCAAATGGTTCGCTGGATGAAAGGGATCGTCGG |

| comX-1 | GACGTAGTAGAGTTGGCGTTCC |

| comX-2 | CTACTGACAGCTTCCAAGGAGCTAAAGAGGTCCCCTTCTTGTTCCATTGAACCTCC |

| comX-3 | GCAAGTCAGCACGAACACGAACCGTCTTATCTCCCCATGTAATGAAGAAGACTGAG |

| comX-4 | GGTTTGTGGCTGTGTTTTCAAATG |

| comX-5 | TTACACTGGAAACGACG |

| comEC-1 | GCTCCAATCAATCTTTTTTCCC |

| comEC-2 | CTACTGACAGCTTCCAAGGAGCTAAAGAGGTCCCCACAACAAGAAGGCATAAG |

| comEC-3 | GCAAGTCAGCACGAACACGAACCGTCTTATCTCCCCTAGCTTGTTTCAGTTTGTC |

| comEC-4 | GGACAGTTTCACTTGATAG |

| comEC-5 | TTCAGTCCGTAGATGAC |

| amiA3-1 | AGGTCATGTCTCCCAGCCATAC |

| amiA3-2 | CTACTGACAGCTTCCAAGGAGCTAAAGAGGTCCCGCATAAATAATCAAGCAGTCTAGC |

| amiA3-3 | GCAAGTCAGCACGAACACGAACCGTCTTATCTCCTTAACTTTGCCATTGACCG |

| amiA3-4 | CTACAGTTGACAAAGAGCCA |

| amiA3-5 | TGCCTTCTTTGGTAGGG |

| amiA1-XhoI | CCGCTCGAGGTCCCTGAACCAACAAC |

| amiA1-SpeIA | TGATGACATGAATAATGTGAC |

| amiA1-SpeIB | AGTCGTTCCACTAGTAC |

| amiA1-PstI | CCTGCTGCAGCTCCAGACATATCCATCG |

| Quantitative RT-PCR | |

| F-comX | TCAAGCTGACATGGAGCAAGAG |

| R-comX | GCCGCCTCACTTCATCATTAAG |

| F-recA | TTGGATATTGCTCTTGGTGCG |

| R-recA | TTTTGAGTCTGAGCAACTGCATG |

| F-dprA | CCATTGCAGTTATCGGGACTG |

| R-dprA | CTGTTCACCCGGTCCGTATTC |

| F-comGA | GAGCTTTATATGCGAGTCGGGC |

| R-comGA | TTCTCACCCACCATCATTCCC |

| F-ldhL | TAAAGCTATCCTTGACGATGAA |

| R-ldhL | ACAATAGCAGGTTGACCGATAA |

For four primers, the restriction enzyme recognition sequences (entire or fragment) are underlined.

Plasmid and strain constructions.

Strain TIL1192 (LMD-9 feo::erm) was constructed as follows. The erm cassette was PCR amplified using the Phusion DNA polymerase, the oligonucleotides ermF and ermR (Table 2), and the plasmid pG+host9 (Table 1) as a template. The 1-kb DNA fragments flanking the feoB gene were PCR amplified using the Phusion DNA polymerase, the LMD-9 chromosome as a template, and oligonucleotides feo-1 and feo-2 for the upstream fragment and oligonucleotides feo-3 and feo-4 for the downstream fragment. The 3′ end of feo1-2 fragment and the 5′ end of the feo3-4 fragment contained a sequence complementary to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the erm cassette, respectively, allowing the joining of these three fragments in a subsequent PCR. This PCR was carried out using the three PCR fragments mixed in equal amounts, the Phusion DNA polymerase, and oligonucleotides feo-1 and feo-4. The resulting 3-kb fragment (feo1-2/erm/feo3-4) was further used to transform LMD-9 natural competent cells as described above. Transformants were selected on M17lac plates with erythromycin and checked by PCR using oligonucleotides feo-5 (located upstream of fragment feo1-2) and ermR. Similarly, we constructed strain TIL1193 (LMD-9 feo::aphA3) as a chromosomal DNA source with a different antibiotic resistance than erythromycin. In this case, the aphA3 cassette (39) was amplified with the oligonucleotides aphA3F and aphA3R. Oligonucleotides feo-1 with feo-6 and feo-7 with feo-4 were used to amplify the upstream and downstream fragments, respectively, of gene feoB. We checked that natural transformation of strain LMD-9 with chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1193 gave a similar transformation rate as with chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1192 (data not shown). A similar procedure was used to construct strain TIL1195 (LMD-9 comEC::erm) with oligonucleotides comEC-1 to comEC-5, strain TIL1196 (LMD-9 comX::erm) with oligonucleotides comX-1 to comX-5, and strain TIL1197 (LMD-9 amiA3::erm) with oligonucleotides amiA3-1 to amiA3-5. When relevant, the flanking regions were sequenced from the chromosomal DNA of the mutant in order to check that the PCR steps introduced no point mutations.

Strain TIL1198 (LMD-9 ΔamiA1) was constructed by deleting an internal fragment of the gene by double-crossover events using pG+host9 as previously described (20). Briefly, oligonucleotides amiA1-XhoI with amiA1-SpeIA and amiA1-SpeIB with amiA1-PstI were used to amplify upstream and downstream fragments of the amiA1 gene from the chromosomal DNA of strain LMD-9. These two fragments were double digested by XhoI with SpeI and SpeI with PstI restriction enzymes, respectively, and cloned between the XhoI and PstI restriction sites of pG+host9 in E. coli TG1 repA+. The fragments of the recombinant plasmid were sequenced, and the plasmid was used to transform electrocompetent cells of S. thermophilus LMD-9. Integration and excision of the plasmid led to deletion of the amiA1 gene. In order to check that this deletion had no polar effect on the downstream genes (amiCDEF), we tested the sensitivity of strain TIL1198 toward aminopterin, a toxic peptide, as previously described (16). Strain TIL1198 was sensitive, indicating that the Ami transporter is still functional in this strain. Strain TIL1198 was further naturally transformed with chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1197 in order to construct strain TIL1199 (LMD-9 ΔamiA1 amiA3::erm).

Real-time reverse transcription-PCR.

To compare the expression of comX, dprA, comGA, and recA genes in the wild-type LMD-9 strain and different mutants grown in CDM or in strain LMD-9 grown in CDM and M17lac, RNA were extracted from cells harvested at an OD600 of 0.2 using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) as previously described (21). Three extractions were performed independently for each condition. RNA were further treated with DNase I (Ambion) as recommended by the manufacturer, and total RNA concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm using a spectrophotometer Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). RNA integrity was checked with an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. cDNA synthesis was generated from 500 ng of RNA by using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers were designed by using PrimerExpress (version 2.0; Applied Biosystems) (Table 2). The real-time PCR was carried out using SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) as recommended by the manufacturer. PCRs were performed at least in duplicate and run on a Mastercycler EP Realplex detector (Eppendorf). The data were computed by using the comparative critical threshold method (2−ΔΔCT) (27). In this case, the ldhL gene (encoding lactate dehydrogenase), expressed at a constant level in our conditions, was used to normalize data. For each gene, an analysis of variance was performed on the threshold cycle (CT) corrected by the CT of the ldhL in order to determine whether the relative expression level between two conditions was significant (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

The Ami transporter controls the synthesis of several proteins essential for natural transformation in streptococci.

In order to find physiological functions controlled by signaling peptides that are internalized by the Ami transporter, we compared the proteome of the wild-type LMD-9 strain and its isogenic mutant with the ami operon deleted, LMD-9 ΔamiCDE (TIL883). In order to bypass the nutritional function of the Ami transporter (16, 20), cells were gown in CDM, a peptide-free medium. Fractions enriched in cell envelope proteins were analyzed by a label-free comparative proteomic approach combining 1D electrophoresis with LC-MS/MS analysis.

We identified 840 different proteins in our extracts (data not shown). They were, in a very large majority, present in both extracts from the wild type and the amiCDE mutant. We focused our attention only on the 20 proteins that were detected in the extracts from strain LMD-9 and no more in the extracts from strain TIL883. In addition to the subunits C, D, and E of the Ami transporter, which were, as expected, not detected in the mutant, 17 proteins fulfilled this criterion (Table 3). Eight were encoded by genes whose orthologs were identified as late competence genes in S. pneumoniae. Among them, six have also been identified as essential for natural transformation (33). The ComX protein involved in the regulation of the competence state was also detected in strain LMD-9 but not in strain TIL883.

TABLE 3.

Proteins identified by LC-MS/MS in strain LMD-9 and that were not detected in strain TIL883 (ΔamiCDE)

| Protein category and GenBank no.a | Mol wt | Protein identification | Abundance factorb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMD-9 | TIL883 | |||

| Proteins essential for natural transformation* | ||||

| STER0189 | 20,100 | ComX | 0.57-0.14 | 0-0 |

| STER0922† | 31,100 | Predicted Rossmann fold nucleotide-binding protein involved in DNA uptake, DprA | 1.12-1.12 | 0-0 |

| STER1521† | 24,400 | DNA uptake protein or related DNA-binding protein, ComEA | 0.63-0.50 | 0-0 |

| STER1821† | 14,700 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein, SsbB | 0.50-0.83 | 0-0 |

| STER1840† | 11,800 | Competence protein ComGC | 1-1.75 | 0-0 |

| STER1841† | 33,800 | Type II secretory pathway/competence component, ComGB | 0.64-0.82 | 0-0 |

| STER1842† | 35,300 | Type II secretory pathway/competence component, ATPase, ComGA | 0.95-0.79 | 0-0 |

| Proteins induced by the competence state but not essential for transformation* | ||||

| STER0057† | 30,100 | Surface antigen, CbpD | 0.75-0.75 | 0-0 |

| STER1430† | 25,700 | RadC | 0.25-0.33 | 0-0 |

| Subunits of the Ami oligopeptide transport system | ||||

| STER_1406 | 39,800 | ABC-type dipeptide/oligopeptide/nickel transport system, ATPase component, AmiE | 1.28-1 | 0-0 |

| STER_1407 | 34,600 | ABC-type dipeptide/oligopeptide/nickel transport system, permease component, AmiD | 2.17-2.33 | 0-0 |

| STER_1408 | 55,500 | ABC-type dipeptide/oligopeptide/nickel transport system, permease component, AmiC | 1.41-1.12 | 0-0 |

| Other proteins | ||||

| STER_0123 | 18,500 | Predicted RNA-binding protein containing a PIN domain | 0.60-0.40 | 0-0 |

| STER_0329 | 32,200 | Urease accessory protein UreH | 0.57-0.57 | 0-0 |

| STER_0331 | 29,100 | ABC-type cobalt transport system, permease component CbiQ or related transporter | 0.23-0.46 | 0-0 |

| STER_1296 | 45,700 | Permease of the major facilitator superfamily | 0.57-0.29 | 0-0 |

| STER_1356 | 50,500 | Radical SAM superfamily enzyme | 1.55-1.65 | 0-0 |

| STER_1652 | 50,300 | lactococcin A ABC transporter permease protein, PcsB | 0.60-1.00 | 0-0 |

| STER_1779 | 12,200 | Thioredoxin domain containing protein | 0.33-0.33 | 0-0 |

| STER_1834 | 43,200 | Acetate kinase | 0.26-0.32 | 0-0 |

*, Categories of proteins defined from the results obtained with the orthologues in S. pneumoniae (33). †, Proteins encoded by genes whose orthologues were identified as late CSP-induced genes in S. pneumoniae (33).

The abundance factor is the ratio between the total number of spectra obtained during the protein identification process on the theoretical number of peptides ranging between 800 and 2,500 Da and detectable by MS for a given protein. Two repetitions were performed for each strain leading to two values.

These results suggest that the Ami transporter is involved in the regulatory pathway that controls the induction of the competence state in S. thermophilus and also that natural transformation can be turned on in CDM during the exponential growth phase.

The S. thermophilus LMD-9 is naturally transformable in CDM.

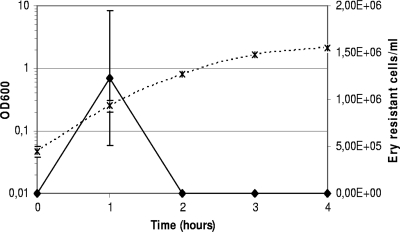

To check the hypothesis formulated on the basis of our proteomic results, we first tested the natural transformability of S. thermophilus using the pG+host9 plasmid. An overnight culture of strain LMD-9 grown in CDM at 42°C was diluted in CDM to an OD600 of 0.05. Samples of this diluted culture were incubated at 42°C. Once each hour for 4 h, a sample was used to measure the OD600, and 100 μl was mixed with 1 μg of plasmid DNA. Cells with DNA were incubated for 2 h at 28°C before being plated on M17lac with erythromycin. We obtained erythromycin-resistant cells (transformants) but only in samples harvested 1 h after dilution (Fig. 1). We observed a mean of 1.2 × 106 transformants per ml (standard error, ±7.2 × 105 transformants/ml; n = 3). This result indicates that bacteria were able to take up the plasmid but only at a specific growth stage corresponding to the beginning of the exponential phase (OD600 0.2-0.3).

FIG. 1.

Development of competence during growth of strain LMD-9 in CDM using pG+host9 plasmid as transformant DNA. The OD600 (×, dashed line) was used to measure cell numbers and count of cells resistant to erythromycin (Ery-resistant cells) (⧫, plain line) was used to assess competence. Then, 1 μg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 100 μl of cells. The means of three independent experiments are presented, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

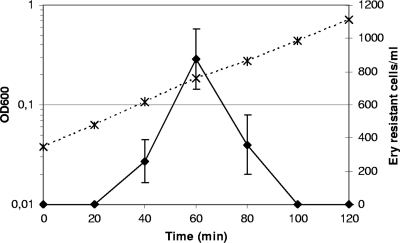

To confirm the transformability of S. thermophilus, to demonstrate its ability to take up linear DNA (PCR fragment or chromosomal DNA), and to incorporate it by homologous recombination in its chromosome and also to assess the kinetics of the transformation rate more precisely, we used, as donor DNA, chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1192, an isogenic strain containing erm in the feo locus. The shape of the kinetics curve of transformation of strain LMD9 (Fig. 2) was similar to that with plasmid DNA (Fig. 1). However, at the optimum, i.e., 1 h after dilution, we observed only a mean of 875 transformants per ml (standard error, ±180 transformants/ml; n = 4) corresponding to a transformation rate of 3.8 × 10−6 (standard error, ±4.6 × 10−7). We also tested the transformability of strain TIL883 (ΔamiCDE) with chromosomal DNA of TIL1192 under the same conditions. No transformant was obtained during the growth of this strain in CDM.

FIG. 2.

Development of competence during growth of strain LMD-9 in CDM using chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1192 as transformant DNA. The OD600 (×, dashed line) was used to measure cell number and count of cells resistant to erythromycin (Ery-resistant cells) (⧫, plain line) was used to assess competence. Then, 1 μg of chromosomal DNA was mixed with 100 μl of cells. The means of four independent experiments are presented, and error bars indicate the standard deviations.

In order to confirm that antibiotic resistant clones obtained from the previous experiments were the result of a natural transformation involving ComEC and most probably a transformasome complex similar to the one described in S. pneumoniae, we constructed strain TIL1195 (LMD-9 comEC::erm). ComEC is one of the proteins of the DNA uptake machinery essential for natural transformation in S. pneumoniae and B. subtilis (12, 33). We tried to naturally transform strain TIL1195 with chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1193 (LMD9 feo::aphA3). Samples of cells of TIL1195 grown in CDM were harvested every 30 min for 2 h and tested for transformation. We obtained no kanamycin-resistant clones.

In order to confirm that ComX is essential for natural transformation in S. thermophilus, we constructed strain TIL1196 (LMD-9 comX::erm). Samples of strain TIL1196 cells grown in CDM were harvested every 30 min for 2 h and tested for transformation with chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1193. As expected, we obtained no kanamycin-resistant clones during this time.

The Ami transporter controls the transcription of genes necessary for the development of competence in streptococci.

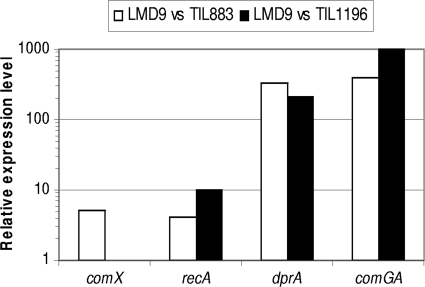

Among the proteins detected in strain LMD-9 and not in strain TIL883, three were chosen for a transcriptional study of the corresponding genes. These proteins were ComGA that plays a role in the assembly of the pseudopilus which is needed for DNA binding (2, 8), DprA, a recombination mediator protein that conveys incoming single-stranded DNA to the recombinase RecA (31) and the sigma factor ComX (25). Although the abundance factor of RecA did not reach zero in strain TIL883, we followed its encoding gene because RecA is essential for transformation in many gram-positive transformable species (13). As shown in Fig. 3, the level of expression of comGA and dprA of strain LMD-9 was higher than that of strain TIL883. To a lesser extent but with significant values (P < 0.05), we obtained similar results with comX and recA that were five- and fourfold, respectively, more highly expressed in strain LMD-9.

FIG. 3.

Relative expression levels of comX, recA, dpr, and comGA between S. thermophilus LMD-9 and strain TIL883 (LMD9 ΔamiCDE) or strain TIL1196 (LMD-9 comX::erm). Relative expression levels were computed by using the comparative critical threshold method (2−ΔΔCT) as described by Livak and Schmittgen (27). The data are expressed as means from three independent experiments and were significant according to an analysis of variance (P < 0.05).

To confirm that the transcription of genes dprA, comGA, and recA is under the control of ComX, we compared the expression of these genes in strain LMD-9 and strain TIL1196 (LMD9 comX::erm). As expected, the transcription of the three genes was significantly higher in strain LMD-9 than in strain TIL1196 (Fig. 3), confirming that their transcription is positively controlled by ComX.

The oligopeptide-binding protein AmiA3 plays the major role in the control of competence.

The genome of strain LMD-9 displays only two genes encoding oligopeptide-binding proteins, amiA1 (ster_1409), the first gene of the ami operon and amiA3 (ster_1411). We constructed two simple mutants and one double mutant with the amiA gene deleted. The transformability of the three mutants was tested using chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1193 and compared to that of strain LMD-9 at its optimum of competence, i.e., 1 h after the dilution of the cells in CDM. As expected, no kanamycin-resistant cells were obtained after transformation of strain TIL1199 (ΔamiA1 amiA3::erm). However, the percentages of the competence rate of strains TIL1197 (amiA3::erm) and TIL1198 (ΔamiA1) compared to that of strain LMD-9 were 1% (standard error, ±2) and 48% (standard error, ±4), respectively. This result suggests that AmiA3 is more important in the triggering of the competence than AmiA1 but that neither is essential.

The growth medium composition influences the competence state of S. thermophilus.

The competence rate kinetics were determined with LMD-9 cells grown in M17lac and with pG+host9 plasmid DNA or chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1192. With both types of donor DNA, no erythromycin-resistant transformants were obtained with cells harvested every 30 min for 2 h.

We then compared the expression of comGA, dprA, recA, and comX from RNA extracted from LMD-9 cells grown in CDM and M17lac medium and harvested at an OD600 of 0.2. We observed that these genes were, respectively, 1,492-, 2,246-, 24-, and 236-fold more highly expressed in CDM than in M17lac, a finding which was consistent with the absence of transformants during growth in M17lac.

Strains CNRZ1066 and LMG18311 are not efficiently transformable in CDM.

We tested natural transformability of the two other S. thermophilus strains, CNRZ1066 and LMG18311. For this purpose, we used the plasmid pG+host9 as donor DNA, and cells were harvested every 30 min for 2 h. We obtained no erythromycin-resistant clones with strain CNRZ1066 and a few erythromycin-resistant clones with strain LMG18311 at 1 h after dilution. However, we obtained 2 × 104 fewer transformants with strain LMG18311 than with strain LMD-9. We also used chromosomal DNA of strain TIL1195 (LMD-9 comEC::erm) as donor DNA because surrounding regions of gene comEC are highly conserved between strains LMD-9, CNRZ1066, and LMG18311 (more than 98% identity over 5 kb upstream and downstream comEC). Under this condition, we obtained no erythromycin-resistant clones with both strains.

DISCUSSION

We have found a natural condition of growth that turns on the transformability of strain LMD-9. Using plasmid or chromosomal DNA as donor DNA, we showed that cells were transformable in CDM, during a narrow window, the optimum being 1 h after the dilution of an overnight culture in CDM. The rates obtained made it possible to easily construct deletion mutants using PCR fragments. We noticed that 1.4 × 104 more transformants were obtained with plasmid DNA than with chromosomal DNA. However, the efficiency of transformation per mole of DNA was only threefold higher with plasmid DNA than with chromosomal DNA. This difference, if significant, could be due to mechanistic differences between intermolecular recombination (linear DNA integration) versus intramolecular recombination (plasmid recircularization).

The competence has been extensively studied in S. pneumoniae. In this bacterium, it develops at the onset of the exponential phase and is inhibited by the stationary phase. A signaling peptide, called CSP (for competence stimulating peptide) and encoded by the gene comC, is secreted and matured by an ABC transporter, ComAB. The detection of the extracellular CSP at the surface of the bacterium is achieved by a TCS. First, the membrane embedded histidine kinase, ComD, autophosphorylates in response to CSP and further phosphorylates its cognate response regulator, ComE, which activates transcription of a few genes, the early CSP-induced genes, including comCDE, comAB, and comX. ComX is an alternative competence specific sigma factor required for expression of late CSP-induced genes, which comprise genes encoding the DNA uptake machinery (11, 23). The role of oligopeptide-binding proteins in the development of competence has also been investigated in S. pneumoniae and is complex. Depending on the strain, the oligopeptide-binding protein, or the type of mutation, the transformability of the strains with mutation in the genes encoding oligopeptide-binding protein is either abolished or the cell-density-dependent control of competence development is derepressed (9). These results led Claverys et al. to propose that oligopeptide-binding proteins play a role in sensing environmental conditions through the transport of nonspecific peptides supplied by the rich medium. These peptides could be further digested by peptidases and the resulting amino acid pool could be sensed by regulatory proteins having a role in different physiological functions, including competence.

We have found similarities in the development of competence between S. thermophilus and S. pneumoniae. The kinetics of the triggering of the competence state are identical: in both cases, the window of competence is narrow and occurs at the early exponential phase of growth. comX and all late CSP-induced genes identified in S. pneumoniae as essential for transformation are present in S. thermophilus. A com-box or cin-box, the recognition site for ComX, identical to that identified in S. pneumoniae (TNCGAATA) (6) is present in front of each transcriptional unit encoding these genes in S. thermophilus (data not shown). Moreover, Håvarstein and coworkers (4) recently showed that the artificial overexpression of comX induced the competent state in S. thermophilus LMG18311 in Todd-Hewitt broth but, surprisingly, not in strain LMD-9. These researchers showed that ComEC and ComX were required for transformation and that ComX controlled the transcription of comEC in strain LMG18311. All of these results indicate that the mechanism of transformation and its regulation are most probably similar in S. thermophilus and S. pneumoniae from the involvement of ComX in the regulatory cascade. We confirmed these results in our natural condition of transformation with strain LMD-9: mutants with comEC or comX deleted were no longer transformable. We showed that ComX positively controls the transcription of at least three late CSP-induced genes that are essential for the transformation of S. pneumoniae: dprA, comGA, and recA. Finally, it is also highly probable that cell lysis occurs in S. thermophilus during the induction of competence because CbpD (a protein with a CHAP domain involved in autolysis in S. pneumoniae) seems to be under the control of ComX as attested by the presence of a com-box in front of cbpD, as well as by our proteomic results.

However, we also observed significant differences between the two streptococci species. First of all, early CSP-induced genes except comX are absent from the genome of S. thermophilus. Second, in contrast to S. pneumoniae but also in contrast to other streptococci such as S. mutans or S. gordonii, in which competence can develop when cells are grown in a rich medium, the competence in S. thermophilus was detected in cells grown in a peptide-free CDM. Strain LMD9 was not transformable in a rich medium (M17lac), and this result was confirmed by a strong decrease in the expression of comX, dprA, and comGA in cells grown in M17lac compared to the levels in CDM. This result highlights the importance of the composition of the medium for this natural condition of transformation. Certain components, which remain to be discovered, either induce the competence state in CDM or repress it in M17lac or both. Surprisingly, strains LMG18311 and CNRZ1066 were not efficiently transformable in CDM under our conditions. Either the conditions are not appropriate to triggering the competence state in these strains or the mechanism controlling the transcription of comX is no longer functional or slightly different in these strains. Finally, the proteomic approach revealed that ComX is synthesized in strain LMD-9 but not at a detectable level in its isogenic derivative deleted for the entire ami locus (TIL883), leading to a complete loss of transformability. This result was confirmed at the transcriptional level. Thus, the absence of detection in strain TIL883 of the eight proteins linked to the competence state that was confirmed at the transcriptional level for three of them is most probably the consequence of the decrease in the transcription of comX in this strain. We also compared the transformation rate of two mutants inactivated for the oligopeptide-binding proteins AmiA1 or AmiA3. The AmiA1 deletion mutant lost 50% of transformability, whereas the AmiA3 deletion mutant lost almost all of its ability to transform, indicating that the two oligopeptide-binding proteins do not have the same importance in the control of competence. Since transformation was observed in CDM, a medium without peptides, and was not efficient in a rich medium (M17lac), we think that the role of Ami in the development of competence in S. thermophilus is not equivalent to that of Opp in S. pneumoniae. We hypothesize that in S. thermophilus, the Ami3 oligopeptide-binding protein imports a specific peptide synthesized by the bacteria and involved with a transcriptional regulator in the control of the expression of comX. This peptide could be a peptide resulting from the degradation of secreted proteins or proteins released after lysis of bacteria or most probably a specific pheromone. We previously identified a cyclic secreted peptide of unknown function and whose production is controlled by a QS mechanism involving the import of a pheromone by the Opp transport system (20). However, a mutant in which the gene encoding this peptide is deleted is not affected in its competence state (data not shown). In contrast to strains CNRZ1066 and LMG18311, strain LMD-9 has a surface protease (14). It could be interesting to study the role of this protease in the development of competence and, more precisely, its involvement in the release of signaling peptides in the extracellular medium.

In conclusion, many “nontransformable” streptococcal and lactococcal species carry an apparently complete set of late competence genes encoding the DNA uptake machinery, as well as the alternative sigma factor that controls their expression, but lack the corresponding QS regulators circuit that controls this sigma in the “transformable” species (10, 29). S. thermophilus belongs to this group of streptococci that lacks early competence genes, but its transformability has been clearly demonstrated here. We propose that the mechanism that controls the transcription of comX in this bacterium differs from those of the model transformable organisms, i.e., does not involved a TCS activated by an extracellular CSP peptide. We hypothesize that in S. thermophilus a peptide is also involved but is detected intracellularly after binding by the oligopeptide-binding protein AmiA3 and internalization by the Ami transporter. We think that this detection is efficient only in a peptide-free medium such as CDM, in which there is no competition for peptide transport, whereas in a rich peptide medium such as M17lac, the nutritional peptides are in large excess compared to pheromones always present in small amounts in the extracellular media. Once inside the cell, this peptide could interact with a transcriptional regulator that would control the transcription of comX and which still need to be discovered. Taking into account data from the genome and our results, the last step of the regulatory cascade in S. thermophilus is most probably identical to what is known from other streptococci, i.e., the expression of comX probably allows the expression of genes that encode the machinery for DNA uptake and processing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Benoit Valot from the PAPPSO platform for writing the script used for the proteomic data analysis; Françoise Rul and Vincent Juillard for critical reading of the manuscript; and Philippe Gaudu, Etienne Dervyn, Pascale Serror, Christine Delorme, and Rozenn Dervyn for advice concerning antibiotic resistance cassettes. We also thank the Plateau d'Instrumentation et de Compétences en Transcriptomique (INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France) for analysis of the RNAs with the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. In addition, we thank the anonymous referees who, by their helpful suggestions, improved the quality of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auchtung, J. M., C. A. Lee, R. E. Monson, A. P. Lehman, and A. D. Grossman. 2005. Regulation of a Bacillus subtilis mobile genetic element by intercellular signaling and the global DNA damage response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10212554-12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergé, M., M. Moscoso, M. Prudhomme, B. Martin, and J. P. Claverys. 2002. Uptake of transforming DNA in gram-positive bacteria: a view from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 45411-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas, I., A. Gruss, S. D. Ehrlich, and E. Maguin. 1993. High-efficiency gene inactivation and replacement system for gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1753628-3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomqvist, T., H. Steinmoen, and L. S. Håvarstein. 2006. Natural genetic transformation: a novel tool for efficient genetic engineering of the dairy bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 726751-6756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolotin, A., B. Quinquis, P. Renault, A. Sorokin, S. D. Ehrlich, S. Kulakauskas, A. Lapidus, E. Goltsman, M. Mazur, G. D. Pusch, M. Fonstein, R. Overbeek, N. Kyprides, B. Purnelle, D. Prozzi, K. Ngui, D. Masuy, F. Hancy, S. Burteau, M. Boutry, J. Delcour, A. Goffeau, and P. Hols. 2004. Complete sequence and comparative genome analysis of the dairy bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus. Nat. Biotechnol. 221554-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, E. A., S. Y. Choi, and H. R. Masure. 1998. A competence regulon in Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed by genomic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 27929-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charbonnel, P., M. Lamarque, J. C. Piard, C. Gilbert, V. Juillard, and D. Atlan. 2003. Diversity of oligopeptide transport specificity in Lactococcus lactis species. J. Biol. Chem. 27814832-14840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung, Y. S., and D. Dubnau. 1998. All seven comG open reading frames are required for DNA binding during transformation of competent Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 18041-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claverys, J. P., B. Grossiord, and G. Alloing. 2000. Is the Ami-AliA/B oligopeptide permease of Streptococcus pneumoniae involved in sensing environmental conditions? Res. Microbiol. 151457-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claverys, J. P., and B. Martin. 2003. Bacterial ‘competence’ genes: signatures of active transformation, or only remnants? Trends Microbiol. 11161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claverys, J. P., M. Prudhomme, and B. Martin. 2006. Induction of competence regulons as a general response to stress in gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60451-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Draskovic, I., and D. Dubnau. 2005. Biogenesis of a putative channel protein, ComEC, required for DNA uptake: membrane topology, oligomerization and formation of disulfide bonds. Mol. Microbiol. 55881-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubnau, D., and C. M. J. Lovett. 2002. Transformation and recombination, p. 453-470. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 14.Fernandez-Espla, M. D., P. Garault, V. Monnet, and F. Rul. 2000. Streptococcus thermophilus cell wall-anchored proteinase: release, purification, and biochemical and genetic characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 664772-4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontaine, L., C. Boutry, E. Guédon, A. Guillot, M. Ibrahim, B. Grossiord, and P. Hols. 2007. Quorum-sensing regulation of the production of Blp bacteriocins in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 1897195-7205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garault, P., D. Le Bars, C. Besset, and V. Monnet. 2002. Three oligopeptide-binding proteins are involved in the oligopeptide transport of Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 27732-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson, T. J. 1984. Studies on the Epstein-Barr virus genome. Ph.D. thesis. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 18.Gitton, C., M. Meyrand, J. Wang, C. Caron, A. Trubuil, A. Guillot, and M. Y. Mistou. 2005. Proteomic signature of Lactococcus lactis NCDO763 cultivated in milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 717152-7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hols, P., F. Hancy, L. Fontaine, B. Grossiord, D. Prozzi, N. Leblond-Bourget, B. Decaris, A. Bolotin, C. Delorme, S. Dusko Ehrlich, E. Guédon, V. Monnet, P. Renault, and M. Kleerebezem. 2005. New insights in the molecular biology and physiology of Streptococcus thermophilus revealed by comparative genomics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29435-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim, M., A. Guillot, F. Wessner, F. Algaron, C. Besset, P. Courtin, R. Gardan, and V. Monnet. 2007. Control of the transcription of a short gene encoding a cyclic peptide in Streptococcus thermophilus: a new quorum-sensing system? J. Bacteriol. 1898844-8854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim, M., P. Nicolas, P. Bessières, A. Bolotin, V. Monnet, and R. Gardan. 2007. A genome-wide survey of short coding sequences in streptococci. Microbiology 1533631-3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishihama, Y., Y. Oda, T. Tabata, T. Sato, T. Nagasu, J. Rappsilber, and M. Mann. 2005. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol. Cell Proteomics 41265-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnsborg, O., V. Eldholm, and L. S. Håvarstein. 2007. Natural genetic transformation: prevalence, mechanisms, and function. Res. Microbiol. 158767-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozlowicz, B. K., M. Dworkin, and G. M. Dunny. 2006. Pheromone-inducible conjugation in Enterococcus faecalis: a model for the evolution of biological complexity? Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296141-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, M. S., and D. A. Morrison. 1999. Identification of a new regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae linking quorum sensing to competence for genetic transformation. J. Bacteriol. 1815004-5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Letort, C., and V. Juillard. 2001. Development of a minimal chemically defined medium for the exponential growth of Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 911023-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makarova, K., A. Slesarev, Y. Wolf, A. Sorokin, B. Mirkin, E. Koonin, A. Pavlov, N. Pavlova, V. Karamychev, N. Polouchine, V. Shakhova, I. Grigoriev, Y. Lou, D. Rohksar, S. Lucas, K. Huang, D. M. Goodstein, T. Hawkins, V. Plengvidhya, D. Welker, J. Hughes, Y. Goh, A. Benson, K. Baldwin, J. H. Lee, I. Diaz-Muniz, B. Dosti, V. Smeianov, W. Wechter, R. Barabote, G. Lorca, E. Altermann, R. Barrangou, B. Ganesan, Y. Xie, H. Rawsthorne, D. Tamir, C. Parker, F. Breidt, J. Broadbent, R. Hutkins, D. O'Sullivan, J. Steele, G. Unlu, M. Saier, T. Klaenhammer, P. Richardson, S. Kozyavkin, B. Weimer, and D. Mills. 2006. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10315611-15616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin, B., Y. Quentin, G. Fichant, and J. P. Claverys. 2006. Independent evolution of competence regulatory cascades in streptococci? Trends Microbiol. 14339-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monnet, V. 2003. Bacterial oligopeptide-binding proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 602100-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mortier-Barrière, I., M. Velten, P. Dupaigne, N. Mirouze, O. Pietrement, S. McGovern, G. Fichant, B. Martin, P. Noirot, E. Le Cam, P. Polard, and J. P. Claverys. 2007. A key presynaptic role in transformation for a widespread bacterial protein: DprA conveys incoming ssDNA to RecA. Cell 130824-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novick, R. P., and E. Geisinger. 2008. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42541-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson, S. N., C. K. Sung, R. Cline, B. V. Desai, E. C. Snesrud, P. Luo, J. Walling, H. Li, M. Mintz, G. Tsegaye, P. C. Burr, Y. Do, S. Ahn, J. Gilbert, R. D. Fleischmann, and D. A. Morrison. 2004. Identification of competence pheromone responsive genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae by use of DNA microarrays. Mol. Microbiol. 511051-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picon, A., E. R. Kunji, F. C. Lanfermeijer, W. N. Konings, and B. Poolman. 2000. Specificity mutants of the binding protein of the oligopeptide transport system of Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 1821600-1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pottathil, M., and B. A. Lazazzera. 2003. The extracellular Phr peptide-Rap phosphatase signaling circuit of Bacillus subtilis. Front. Biosci. 832-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 37.Slamti, L., and D. Lereclus. 2002. A cell-cell signaling peptide activates the PlcR virulence regulon in bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group. EMBO J. 214550-4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sturme, M. H., M. Kleerebezem, J. Nakayama, A. D. Akkermans, E. E. Vaugha, and W. M. de Vos. 2002. Cell to cell communication by autoinducing peptides in gram-positive bacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 81233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trieu-Cuot, P., and P. Courvalin. 1983. Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus faecalis plasmid gene encoding the 3′5"-aminoglycoside phosphotransferase type III. Gene 23331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waters, C. M., and B. L. Bassler. 2005. Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21319-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams, P., K. Winzer, W. C. Chan, and M. Cámara. 2007. Look who's talking: communication and quorum sensing in the bacterial world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 3621119-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia, Q., E. L. Hendrickson, T. Wang, R. J. Lamont, J. A. Leigh, and M. Hackett. 2007. Protein abundance ratios for global studies of prokaryotes. Proteomics 72904-2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]