Abstract

p63, a member of the p53 tumor suppressor family, is essential for the development of epidermis as well as other stratified epithelia. Collective evidence indicates that ΔNp63 proteins, the N-terminally deleted versions of p63, are essential for the proliferation and survival of stratified epithelial cells and squamous cell carcinoma cells. But in response to DNA damage, ΔNp63 proteins are quickly downregulated in part through protein degradation. To elucidate the mechanisms by which ΔNp63 proteins are maintained at relatively high levels in proliferating cells but destabilized in response to stress, we sought to identify p63 interactive proteins that regulate p63 stability. We found that Stxbp4 and RACK1, two scaffold proteins, play central roles in balancing ΔNp63 protein levels. While Stxbp4 functions to stabilize ΔNp63 proteins, RACK1 targets ΔNp63 for degradation. Under normal growth conditions, Stxbp4 is indispensable for maintaining high basal levels of ΔNp63 and preventing RACK1-mediated p63 degradation. Upon genotoxic stress, however, Stxbp4 itself is downregulated, correlating with ΔNp63 destabilization mediated in part by RACK1. Taken together, we have delineated key mechanisms that regulate ΔNp63 protein stability in vivo.

p63, together with p73, is a member of the p53 tumor suppressor family whose members share structural similarities in key regions, such as the DNA-binding and oligomerization domains (61). While the central role of p53 in preventing tumorigenesis has been well established, whether p63 or p73 functions as a tumor suppressor in vivo is still under active investigation (14, 23, 44). Such complexity could be attributed to the fact that p63 (and p73) can be expressed as multiple isoforms that possess different functions (36). Alternative splicing of p63 RNA produces three different C termini: α, β, or γ, the in vivo functions of which have not been well explored. Moreover, p63 can be transcribed from two distinct promoters to generate N-terminal isoforms that either contain (TA) or lack (ΔN) a full transactivation domain.

In general, TAp63 proteins can exert p53-like activities with their abilities to activate a number of common p53-responsive genes involved in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (16, 17, 40, 59, 62). The physiological roles of TAp63 proteins in vivo are supported by two mouse studies. One study uncovered an important role for TAp63 in neuronal death during development and in tissue culture upon withdrawal of survival factors (22). In another report, Suh et al. showed that TAp63 is constitutively expressed in mouse female germ cells and is essential for DNA damage-induced oocyte apoptosis (51).

ΔNp63 proteins, on the contrary, can have functions opposite to those of p53, TAp63, and TAp73. The ΔN isoforms lack the transactivating regions of the TA isoforms, although they may have some transactivation ability (18, 60). ΔNp63 could, nevertheless, work in part by competing with the TA versions of p53 family members for common target genes (2, 45, 57). ΔNp63 may also use its oligomerization domain to bind TAp63 and TAp73, rendering them inactive (7, 10, 45). Additionally, ΔNp63 can activate cell survival genes, such as those involved in cell-matrix adhesion (6). Therefore, ΔNp63 proteins can play prosurvival roles in cells and may be oncogenic if overexpressed in certain cellular contexts.

In development, ΔNp63 isoforms are generally believed to maintain the proliferative potential of basal regenerative cells (containing stem cells) in stratified epithelium, including skin, thymus, breast, prostate, and urothelia (3, 35). In support of this notion, mice lacking all of the ΔNp63 isoforms do not have stratified epithelia (37, 51, 63). Conversely, transgenic mice expressing ΔNp63, but not TAp63, are able to partially rescue the epidermal defects seen in p63-null mice (5). Furthermore, ablation of all p63 isoforms, but not TAp63 isoforms alone, reduces the survival of basal mammary epithelium cells (6). In addition to its role in normal epithelium cells, ΔNp63 is commonly overexpressed in squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) (19). Studies of head and neck SCC cells demonstrated that ΔNp63 promotes cell survival by inhibiting the TAp73-dependent apoptotic pathway (45).

While promoting cell proliferation and survival under normal conditions, ΔNp63 is downregulated upon DNA damage at the levels of both transcription and protein stability (15, 30, 32, 56). Such downregulation may allow cells to better respond to genotoxic stress since ΔNp63 overexpression or ablation renders cells resistant or sensitive to apoptosis, respectively (2, 27, 30).

In order to investigate how ΔNp63 stability is regulated in both normal and stress situations, we searched for p63-interactive partners in a human keratinocyte cDNA library using yeast two-hybrid screening. We found that Stxbp4 and RACK1, two p63-binding proteins, are critical to the control of the ΔNp63 protein level and work in opposite fashions. We demonstrate that ΔNp63 degradation is mediated at least in part by RACK1. Under normal growth conditions, Stxbp4 plays a critical role in stabilizing ΔNp63 proteins by inhibiting RACK1-mediated p63 degradation. Upon genotoxic assaults, Stxbp4 is downregulated, correlating with ΔNp63 destabilization. Therefore, we have identified key mechanisms by which ΔNp63 protein stability is regulated in cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and drugs.

Cell lines used in this study were 293 human embryonic kidney cells, H1299 human lung carcinoma cells, U2OS human osteosarcoma cells, HaCaT human keratinocytes, and Scaber human bladder cancer cells. These cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C with 5% CO2. The H1299 stable cell line that expresses ΔNp63α under a tetracycline-regulated promoter was generously provided by Xinbin Chen (UC Davis) and was cultured as described previously (12). The DNA-damaging drugs used were etoposide (Sigma) and camptothecin (CalBiochem) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The proteasome inhibitor MG132 (CalBiochem) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (Sigma) was dissolved in H2O.

Mammalian expression plasmids and transfection.

cDNAs encoding various full-length human p63 isoforms (TAp63α, TAp63β, TAp63γ, ΔNp63α, ΔNp63β, and DNp63γ) were amplified by PCR using high-fidelity PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) from either a commercial keratinocyte cDNA library (Clontech, as described for yeast two-hybrid screening) or the cDNAs of 293 cells prepared as a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay, described below. Plasmids expressing three-Flag-tagged or Myc-tagged p63 proteins were constructed by cloning these p63 cDNAs into the p3XFLAG-CMV-7.1 vector (Sigma) or into the pCMV-Myc vector kindly provided by R. Prywes (Columbia University, New York, NY). The Y449F ΔNp63 mutant was generated by site-directed mutagenesis according to the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene). A construct expressing pFlag-Stxbp4 was made by PCR amplification of the Stxbp4 open reading frame using pGAD-Stxbp4 (as described below for yeast two-hybrid screening) as a template and was then subcloned into the p3XFLAG-CMV-7.1 vector. The pFlag-Stxbp4ΔWW plasmid was made by PCR amplification of the Stxbp4 region lacking the C-terminal WW domain using pFlag-Stxbp4 as a template and subcloned into the p3XFLAG-CMV-7.1 vector. All the constructs were sequenced for verification. pcDNA3-T7-RACK1 was kindly provided by Edward Ratovitski (John Hopkins University School of Medicine) (15). The Myc-Itch plasmid was a kind gift from Tony Pawson (Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute) (58). Transient cell transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Baculovirus protein expression and purification.

Baculovirus donor plasmids expressing six-His-tagged p63 proteins were constructed by cloning cDNAs encoding the p63 variants into the pFastBac HTa vector (Gibcol BRL). Recombinant p63 baculoviruses were prepared and amplified as indicated in the Bac-to-Bac system (Gibcol BRL). To express and purify p63 proteins, Sf9 cells freshly seeded in 15-cm plates were infected for 1 h with p63 viruses. After 48 h, cells were collected and washed twice with PBS (1 mM Na2HPO4, 10.5 mM KH2PO4, 140 mM NaCl, 14 mM KCl [pH 6.2]). The following steps were all performed at 4°C with ice-cold buffers. Briefly, cells were lysed for 1 h in Bac lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 5 mM imidazole, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 5 μg/ml aprotinin). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min and then incubated with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen) for 3 h at 4°C. After washing the resin twice with Bac wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.2% NP-40, 15 mM imidazole, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM PMSF), twice with Bac wash buffer without NP-40, and then once with Bac wash buffer containing 30 mM imidazole but without NP-40, proteins on the resin were eluted with Bac elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 250 mM imidazole, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM PMSF) in consecutive fractions. Pooled fractions containing the highest concentration of p63 proteins were dialyzed and stored at minus 80°C.

Bacterial protein expression and purification.

The cDNAs encoding both the full-length (553 amino acids [aa]) and N-terminal portion (aa 1 to 207) of Stxbp4 were cloned into the pRP259 vector (8) to express glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused Stxbp4 proteins. The same Stxbp4 N terminus was also cloned into the pTrcHisB vector (Invitrogen) to express six-His-tagged Stxbp4 proteins. These constructs were transformed into the Escherichia coli DH5α strain for protein expression. The GST-Stxbp4 (1-207) fusion protein was purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol, with slight modification. Briefly, cells were lysed by sonication in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% NP-40 and 1 mM PMSF on ice-bath. Cleared supernatant after centrifugation was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads for 4 h at 4°C. After washing proteins four times with PBS containing 0.5% NP-40 and three times with PBS, they were eluted with elution buffer (20 mM reduced glutathione, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0]). The six-His-tagged Stxbp4 (1-207) protein was purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin, as previously described for purifying His-tagged p53 (65).

Yeast two-hybrid screening.

The yeast two-hybrid system used was LexA-based, and the reporter strain was L40 (55). The “bait” plasmids were constructed by cloning the C-terminal fragment of TAp63α (aa 392 to 641) or TAp63β (aa 392 to 516) into the pVJL11 vector (8). The “prey” library used was derived from human keratinocytes (Matchmaker cDNA library; Clontech). A total of approximately 1 to 2 × 108 transformants were screened in each case, as described previously (55). Candidate yeast plasmids from the primary screening were recovered in the E. coli HB101 strain by nutritional selection on minimal medium according to Clontech's recommendation. They were then cotransformed with the bait plasmid back to the reporter yeast strain for a secondary interaction screening. Plasmids encoding Stxbp4 (pGAD-Stxbp4) and RACK1 (pGAD-RACK1) were among the positive p63-interactive candidates.

Antibodies.

Peptides specific for TAp63 (5′-DLNFVDEPSEDGATNK-3′) and ΔNp63 (5′-MLYLENNAQTQFSEP-3′) were used to raise TA or ΔNp63 polyclonal antibodies (Covance). The Stxbp4 polyclonal antibody was also raised commercially (Proteintech Group) against purified GST-Stxbp4 (1-207). Anti-ΔNp63 and anti-Stxbp4 crude sera were affinity purified against the baculovirally expressed ΔNp63β or the bacterially expressed His-tagged Stxbp4 (1-207) protein, respectively, as described previously (53). The pan-p63 monoclonal antibody (4A4), p63α-specific polyclonal antibody (H-129), and RACK1 monoclonal antibody (B-3) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Itch monoclonal antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences. Tag-specific antibodies include anti-Flag (M2; Sigma), antihemagglutinin (HA1.1; Covance), anti-His (Santa Cruz), anti-T7 (Novagen), and anti-Myc (collected as ascites using the 9E10 hybridoma cell line). Antiactin antibody was from Sigma.

RNA interference.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes were synthesized by either Qiagen or Invitrogen. The sequences for Stxbp4-1 were 5′-(CCUGGAGGAGACUGUUAUA)dTdT-3′ (sense) and 5′-(UAUAACAGUCUCCUCCAGG) dAdA-3′ (antisense). The sequences for Stxbp4-2 were 5′-(GGACCUCAAGCCUCAACAU)dTdT-3′ (sense) and 5′-(AUGUUGAGGCUUGAGGUCC)dAdT (antisense). The siRNA sequences for p63-2 were 5′-(CGACAGUCUUGUACAAUUU)dTdT (sense) and (AAAUUGUACAAGACUGUCG)dTdG (antisense). Sequences for p63-1 (2), RACK1-KD1 (26), Itch (47), and Luc (13) have been described previously. For siRNA transfections, cells were usually transfected with 50 nM siRNA using DharmaFECT 1 siRNA transfection reagent (Dharmacon) unless otherwise indicated.

Immunoprecipitation, Western blotting, and far-Western analysis.

For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in IP buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 420 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (0.5 mM PMSF, 1 μM benzamidine, 3 μg/ml leupeptine, 0.1 μg/ml bacitracin, and 1 μg/ml α-macroglobulin) and a mixture of phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). Cleared lysate after centrifugation was incubated with the indicated antibodies for at least 2 h at 4°C by rocking. The immunocomplexes were captured on protein G beads (GE Healthcare) by incubating for at least 1 h at 4°C. The beads were then washed five times with IP buffer and finally resuspended in Laemmli protein sample buffer.

General procedures for Western blotting are as described previously (53). Detection was usually performed with the chemiluminescent reagent from GE Healthcare and sometimes with a more sensitive chemiluminescent substrate from Millipore to enhance the weak signals. To detect the endogenous Stxbp4 protein, blots were usually incubated with anti-Stxbp4 antibody overnight at 4°C.

For the far-Western assay, proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for standard immunoblotting. The membrane was then incubated in denaturation buffer (6 M guanidine hydrochloride in PBS) twice for 5 min each at 4°C and then successively incubated in 3, 1.5, 0.75, 0.375, 0.188, and 0.094 M guanidine hydrochloride in PBS containing 1 mM dithiothreitol for 10 min each at 4°C. After washing twice with PBS, the blot was blocked with 3% nonfat milk in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 for 45 min at room temperature. After blocking, the blot was rinsed twice with PBS-0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with 0.4 μg/ml purified 6× His-tagged p63 proteins in PBS containing 1 mM dithiothreitol and 0.5 mM PMSF overnight at 4°C. Then the blot was washed five times with PBS-0.1% Tween 20, probed with anti-His antibody for 3 h at room temperature, and processed for immunoblotting analysis as described previously (53).

RT-PCR.

RNA was prepared using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed (2 μg RNA as template) using the ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen). PCRs were then performed using 1 μl cDNA as template with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). ΔNp63-specific primers amplify a 260-bp region: 5′-TTGTACCTGGAAAACAATGCCCAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTGGAAGGACACGTCGAAACTGTG-3′ (antisense). Stxbp4-specific primers amplify a 260-bp region: 5′-ACCACTGGGAAGGAATGGACGTAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACTTTTCTGGTTGGGGAGTTCTC-3′ (antisense). β-Actin-specific primers amplify a 630-bp region: 5′-GGCATCGTGATGGACTCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCTGGAAGGTGGACAGCG-3′ (antisense).

Cell cycle profile and senescence analyses.

Cells were processed for analysis by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) as described previously (53). The percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase was quantified using the ModFit program. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (β-Gal) staining was done according to instructions from Cell Signaling, which produced the reagents.

RESULTS

Downregulation of ΔNp63 in keratinocytes inhibits cell proliferation and leads to senescence.

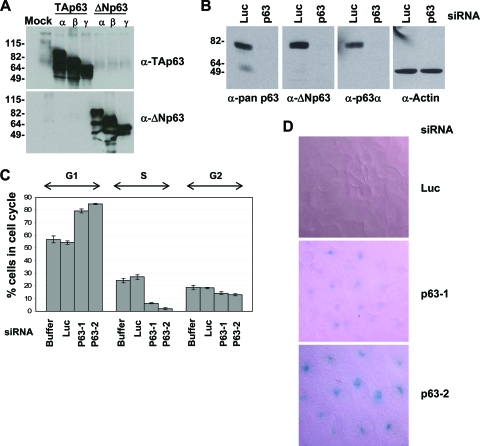

To study the function of different p63 isoforms in cells, we raised polyclonal antibodies that can specifically recognize either TA- or ΔNp63 proteins (Fig. 1A). After affinity purification using baculovirus-derived purified ΔNp63 protein, our ΔNp63 antibody revealed a predominant p63 isoform in HaCaT cells, a human nontransformed keratinocyte line (4). This polypeptide was also detected by two antibodies, one which recognizes all p63 isoforms (4A4) and another α-isoform-specific antibody. This indicated that ΔNp63α is the dominant p63 version in human keratinocytes (Fig. 1B) and in a number of bladder cancer cell lines (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Downregulation of ΔNp63 in keratinocytes causes cell cycle arrest and eventually leads to senescence. (A) Extracts of sf9 cells infected with baculoviruses expressing various p63 isoforms were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with p63 polyclonal antibodies that were raised against either TA or ΔN isoforms. The sizes of the molecular weight markers (in thousands) are indicated on the left. (B) Lysates of HaCaT cells transfected with control (Luc) or p63-specific (p63-1) siRNA were immunoblotted with pan-p63 (4A4), ΔNp63-specific, or p63α-specific antibodies as described. Actin serves as a loading control. Molecular weights (in thousands) are indicated on the left. (C) HaCaT cells were transfected with control (Luc) or p63-specific (p63-1 or p63-2) siRNAs. Cells were collected 3 days later and processed for FACS analysis. (D) HaCaT cells were stained for senescence-associated β-Gal activity 6 days after siRNA transfection.

When we inhibited the expression of p63 in HaCaT cells via siRNAs, we observed a dramatic decrease of cells in the S phase and a significant G1-phase cell cycle arrest (Fig. 1C and see Fig. 3). Moreover, in a subset of cells, staining by a senescence-associated β-Gal marker was detected, indicative of their undergoing senescence (Fig. 1D). In contrast, knocking down TAp63 expression via TA-specific siRNAs had no discernible impact on overall p63 protein expression or cell proliferation (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that ΔNp63α is the p63 isoform that mediates HaCaT cell proliferation. Of note, the phenotypes with HaCaT cells following p63 knockdown are highly reminiscent of those in primary human and mouse keratinocytes (11, 24, 56), validating the utility of the HaCaT cell line as a model system to study the function of ΔNp63 in keratinocytes.

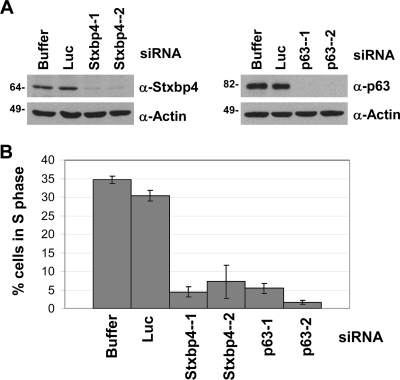

FIG. 3.

Stxbp4, like ΔNp63, is essential for keratinocyte proliferation. HaCaT human keratinocytes were transfected with control luciferase (Luc), two Stxbp4, or two p63 siRNAs, as indicated. Cells were collected 72 h later and processed for immunoblotting (A) or FACS analysis (B). The population of cells in the S phase is shown as an index of cell proliferation. Molecular weights (in thousands) are indicated on the left in panel A.

Identification of Stxbp4 as a novel p63-binding protein.

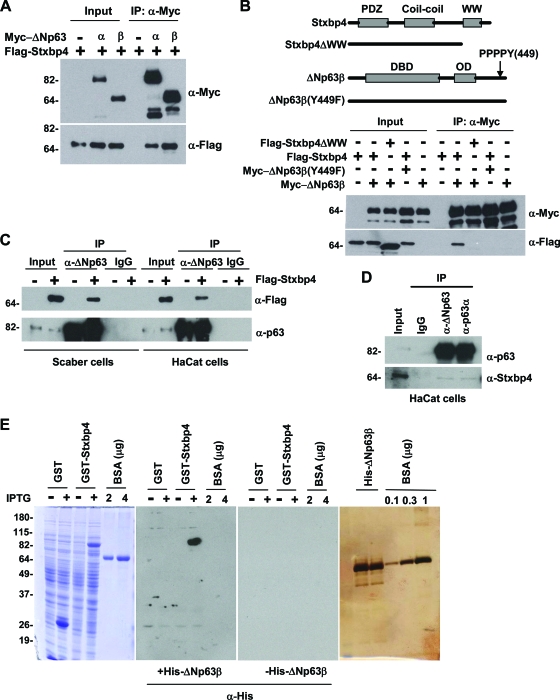

To investigate the mechanisms by which p63 function is regulated in the cell, we sought to identify p63-interacting proteins. Since p63 has a pivotal role in epithelial biology, we used the yeast two-hybrid system to screen a human keratinocyte cDNA library. Our screen was validated by the successful isolation of a number of proteins that are known to interact with p63 or p73, including YAP (50), RACK1 (15, 41), SUMO-1, and UBC9 (20). One of the novel p63-binding candidates that we identified was Stxbp4 (syntaxin binding protein 4), an adapter-like protein containing an N-terminal PDZ domain, a central coil-coiled domain, and a C-terminal WW motif (Fig. 2B). Synip, the mouse homolog of Stxbp4 that shares 77% identity with Stxbp4 at the amino acid level, has been shown to play a role in negatively regulating glucose transporter 4 translocation in the insulin-signaling pathway (38). While such a function for human Stxbp4 waits to be verified, it is tempting to speculate that it may have other important activities, since it can bind p63.

FIG. 2.

The physical interaction between p63 and Stxbp4. (A) Exogenously expressed p63 and Stxbp4 interact with each other. H1299 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding Flag-tagged Stxbp4 and Myc-tagged ΔNp63α or ΔNp63β. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc antibody and immunoblotted with anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies, respectively. A total of 15% of the lysate was used in the input sample. (B) The WW domain of Stxbp4 and the PPPPY motif of ΔNp63 are required for Stxbp4 interaction with p63. Shown on top is a schematic illustration of the modular structure of Stxbp4 and ΔNp63β and corresponding deletion or point mutation constructs. H1299 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and processed for immunoblotting as shown in panel A. A total of 10% of the lysate was used in the input sample. (C) Endogenous p63 proteins interact with exogenous Stxbp4. A Flag-tagged Stxbp4 construct was transfected into Scaber and HaCaT cells and after 24 h, cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-ΔNp63 antibody or control rabbit IgG, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-p63 (4A4) antibodies, respectively. A total of 2% of the lysate was used in the input sample. (D) Endogenous Stxbp4 and p63 interact. Lysates of HaCaT cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-ΔNp63, anti-p63α, or control rabbit IgG, followed by immunoblotting with anti-p63 (4A4) and anti-Stxbp4 antibodies, respectively. A total of 1% of the lysate was used as the input sample. (E) Stxbp4 can directly bind p63 in vitro as indicated by far-Western analysis. His-tagged p63 proteins were purified from baculovirus-infected sf9 cells, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and then visualized by silver staining (right panel). GST or GST-Stxbp4 proteins were expressed in DH5α cells by IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction, then separated by SDS-PAGE, and stained by Coomassie blue (left panel). The same lysate was resolved on two parallel gels, which were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, denatured by 6 M guanidinium HCl, and renatured by serial dilutions of guanidinium HCl as described in Materials and Methods. The membrane was then incubated with or without 0.5 mg/ml purified His-tagged p63 (the middle two panels) and immunoblotted with anti-His antibody. Molecular weights (in thousands) are indicated on the left.

To confirm that the observed Stxbp4-p63 interaction in yeast occurs in mammalian cells, we performed a series of coimmunoprecipitation analyses. First, we transfected Myc-tagged p63 and Flag-tagged Stxbp4 into H1299 cells to test whether they can interact when both are ectopically expressed. Myc-ΔNp63α and Myc-ΔNp63β proteins from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody, and the presence of Flag-Stxbp4 was detected by anti-Flag antibody. As shown in Fig. 2A, Stxbp4 can associate with both p63 proteins. As a control, there was no detectable Stxbp4 in the immunoprecipitate in the absence of p63. Furthermore, we determined that the interaction is dependent on the WW domain of Stxbp4 and the PPPPY449 motif of p63. As seen in Fig. 2B, a deletion of the WW domain of Stxbp4 or a single amino acid substitution of Y449 with F449 in the C-terminal PPPPY motif of p63 is sufficient to inhibit the interaction between Stxbp4 and p63.

We also introduced Flag-Stxbp4 into HaCaT cells and Scaber human bladder cancer cells (54) to determine whether endogenous ΔNp63 proteins can bind exogenous Stxbp4. Here we found ectopically expressed Stxbp4 in the anti-ΔNp63 but not the anti-control immunoglobulin G (IgG) immunoprecipitates (Fig. 2C). Finally, we examined the ability of the endogenous proteins to interact (Fig. 2D). To this end, we raised Stxbp4 polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 3A) and detected a specific Stxbp4-p63 complex in HaCaT cell lysates when the endogenous p63 proteins were immunoprecipitated with two different p63 antibodies (anti-ΔNp63 and anti-p63α). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Stxbp4 and ΔNp63 are able to bind each other in mammalian cells.

To determine whether the interaction between Stxbp4 and p63 is direct, we used far-Western blot analysis. In brief, full-length Stxbp4 fused to GST or GST alone was expressed in E. coli, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immobilized onto nitrocellulose. Following denaturation and renaturation, proteins on the membrane were incubated with baculovirus-purified ΔNp63 proteins, and bound p63 was detected by immunoblotting analysis. As shown in Fig. 2E, Stxbp4 directly binds to p63 in vitro. As negative controls, GST alone, bovine serum albumin, and the vast majority of the bacterial proteins do not interact with p63. Therefore, we conclude that Stxbp4 is a bona fide interactive partner for p63.

Stxbp4, like p63, is essential for keratinocyte proliferation.

Having confirmed the physical interaction between Stxbp4 and p63, we next wanted to address the functional significance of their association. To this end, we designed siRNAs to efficiently knock down the expression of Stxbp4 and examined their impact on cell proliferation (Fig. 3A). As seen in Fig. 3B, Stxbp4 ablation by two independent siRNAs significantly decreased the percentage of cells in S phase, as measured by flow cytometry, similar to that caused by p63 knockdown. Therefore, like ΔNp63, Stxbp4 is crucial for keratinocyte proliferation, suggesting that they may function in the same pathway.

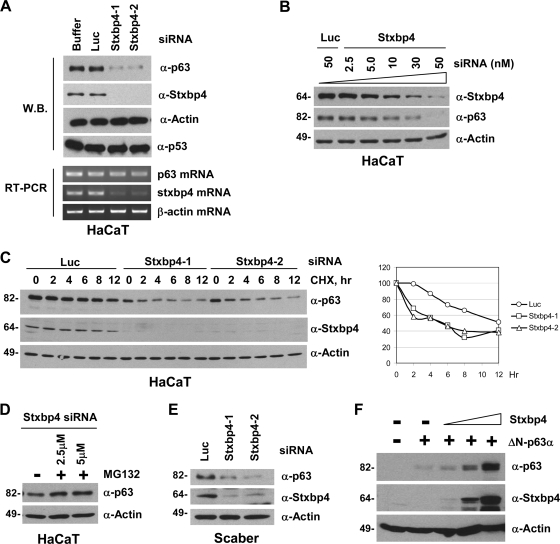

Stxbp4 is a positive regulator of ΔNp63 stability.

The same reduction in cell proliferation seen upon silencing of Stxbp4 or p63 led us to speculate that ΔNp63 might not be functional without Stxbp4. Interestingly, we found that downregulation of endogenous Stxbp4 in HaCaT keratinocytes significantly reduced the levels of the endogenous ΔNp63 protein without affecting ΔNp63 mRNA levels and had no impact on the level of mutant p53 (Fig. 4A). The requirement for Stxbp4 to maintain p63 levels was also confirmed with Scaber bladder cancer cells (Fig. 4E). In addition, the degree of ΔNp63 downregulation correlated with the extent of Stxbp4 knockdown in a siRNA dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). The decrease in p63 levels upon knockdown of Stxbp4 was due to the destabilization of p63, as shown by the decrease in the p63 half-life (Fig. 4C) and by the ability of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 to prevent this downregulation (Fig. 4D). Conversely, we found that ectopic Stxbp4 expression increased the steady-state levels of cotransfected ΔNp63 proteins in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4F). Taken together, these data indicate that Stxbp4 is an important positive regulator of ΔNp63 stability in cells.

FIG. 4.

Stxbp4 regulates ΔNp63 protein stability. (A) HaCaT cells were transfected with siRNAs as described in the legend for Fig. 3. At 72 h, cells were collected and processed for immunoblotting (W.B.) to detect p63, Stxbp4, p53, and actin (top four panels). The RNA transcript levels of p63, stxbp4, and actin were analyzed by RT-PCR (bottom three panels). (B) The dose-dependent p63 destabilization by Stxbp4 siRNA is shown, using Stxbp4-2 siRNA as an example. (C) At 62 h after siRNA transfection, HaCaT cells were treated with 20 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHC) and collected at the indicated time points to detect p63, Stxbp4, and actin by Western blotting. The results after densitometric analysis and normalization based on actin levels were graphed (right). (D) At 42 h after siRNA transfection, HaCaT cells were treated with or without MG132 for 8 h and were subjected to immunoblotting. (E) Scaber cells were transfected with control luciferase (Luc) or two Stxbp4 siRNAs for 72 h and analyzed by immunoblotting. (F) U2OS cells were transfected with Flag-tagged ΔNp63α alone or together with an increasing amount of Flag-tagged Stxbp4. Cells were collected 44 h later and were processed for immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Molecular weights (in thousands) are indicated on the left of panels B, C, D, E, and F.

Itch-mediated ΔNp63 degradation is inhibited by Stxbp4, but endogenous Itch is unlikely to be the sole E3 ligase for ΔNp63.

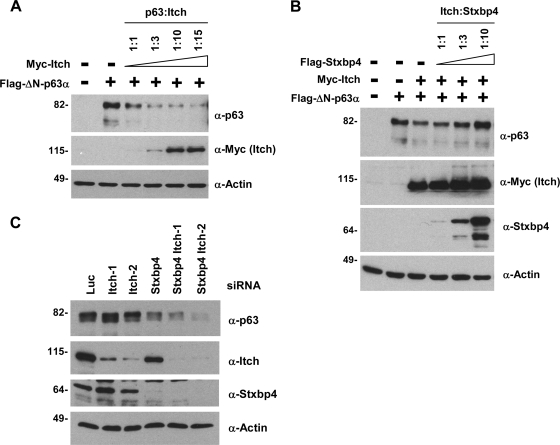

To further investigate the mechanism by which Stxbp4 regulates p63 stability, we determined whether Stxbp4 interferes with p63 degradation through Itch, a recently hypothesized E3 ligase for p63 (46, 48). Consistent with previous reports, we found that Itch overexpression led to ΔNp63 degradation (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, Itch-induced ΔNp63 degradation was readily inhibited by Stxbp4 coexpression (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that Stxbp4 stabilizes p63 by preventing its degradation, in agreement with our data described above.

FIG. 5.

Itch-mediated ΔNp63 degradation is inhibited by Stxbp4, but endogenous Itch is unlikely to be involved in ΔNp63 degradation. (A) 293 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged ΔNp63α (0.1 μg) and Myc-tagged Itch at the indicated ratios (0.1 μg, 0.3 μg, 1 μg, and 1.5 μg). (B) 293 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged ΔNp63α (0.1 μg) and Myc-tagged Itch (0.3 μg), together with different amounts of Flag-tagged Stxbp4 plasmid (0.3 μg, 1 μg or 3 μg). At 48 h after transfection, cells shown in panels A and B were processed for immunoblotting to detect p63, Itch, Stxbp4, and actin, as indicated. (C) HaCaT cells were transfected with control (luciferase [Luc]), Stxbp4 (Stxbp4-1), or Itch (Itch-1 and Itch-2) siRNAs. Cells were collected 72 h later and processed for immunoblotting. Molecular weights (in thousands) are indicated on the left.

Next, we assessed whether endogenous Itch mediates the degradation of endogenous ΔNp63. To this end, we asked whether Itch ablation could prevent ΔNp63 destabilization caused by Stxbp4 downregulation. Unexpectedly, even though Itch expression was efficiently knocked down using two different siRNAs, ΔNp63 was still destabilized in the absence of Stxbp4 (Fig. 5C). Although we cannot exclude that the residual Itch remaining after siRNA knockdown is sufficient to mediate ΔNp63 turnover, our data indicate that Itch is not the major E3 ligase that controls basal ΔNp63 turnover in keratinocytes.

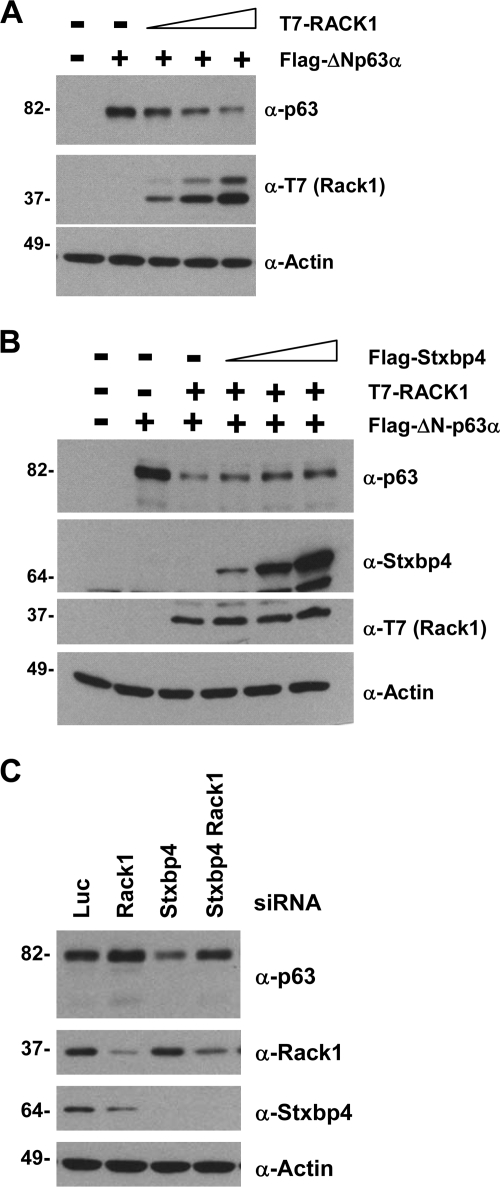

Stxbp4 stabilizes ΔNp63 by preventing its degradation through RACK1.

RACK1, a p63-interacting protein identified from yeast two-hybrid screening in both our and others' studies, has been shown to target ΔNp63 for proteasomal degradation upon DNA damage (15). Therefore, we next wanted to determine whether Stxbp4 interferes with p63 degradation through RACK1. We first confirmed that RACK1 could efficiently degrade ΔNp63 (Fig. 6A). Upon coexpression of Stxbp4, however, RACK1-mediated ΔNp63 degradation was inhibited (Fig. 6B). More importantly, knocking down the expression of endogenous RACK1 via siRNA rescued p63 degradation caused by Stxbp4 ablation (Fig. 6C). Note that there was a modest decrease in the Stxbp4 protein when RACK1 alone was silenced (Fig. 6C, lane 2). This Stxbp4 reduction, however, did not override the stabilization of ΔNp63 caused by RACK1 ablation. Therefore, our data suggest that Stxbp4 maintains high basal levels of ΔNp63 in cells by suppressing ΔNp63 degradation by RACK1.

FIG. 6.

ΔNp63 destabilization in the absence of Stxbp4 is dependent on RACK1 pathway. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with 0.1 μg plasmid expressing Flag-tagged ΔNp63α alone and with increasing amounts of plasmid expressing T7-tagged RACK1 (0.3 μg, 1 μg, or 3 μg). Cells were collected 24 h later and processed for immunoblotting. (B) U2OS cells were transfected with Flag-tagged ΔNp63α (0.1 μg) and T7-tagged RACK1 (2 μg), together with increasing amounts of Flag-tagged Stxbp4 (0.5 μg, 1 μg, or 2 μg). At 40 h after transfection, cells were processed for immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (C) HaCaT cells were transfected with control (luciferase [Luc]), Stxbp4 (Stxbp4-1), RACK1 (Rack1-KD1) siRNAs, or siRNAs against both Stxbp4 and RACK1. Cells were processed for immunoblotting 72 h after transfection. Molecular weights (in thousands) are indicated on the left.

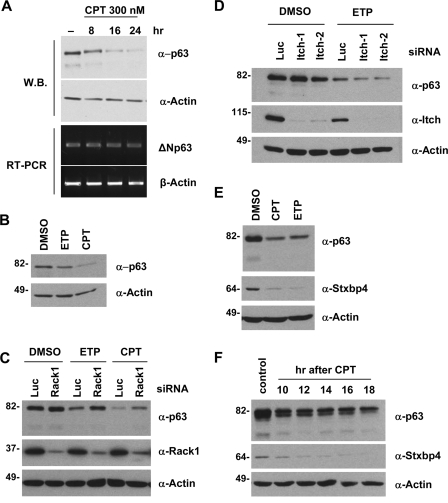

ΔNp63 degradation in response to DNA damage is Itch independent but partially RACK1 dependent and correlates with Stxbp4 downregulation.

Although ΔNp63 is essential for cell proliferation, it is quickly downregulated upon DNA damage. In HaCaT cells at early time points, ΔNp63 downregulation occurs mainly at the posttranscriptional level (Fig. 7A). ΔNp63α is also downregulated upon DNA damage in a stable cell line expressing ΔNp63α from a tetracycline-regulated promoter (Fig. 7B). These data support others' findings that ΔNp63 downregulation upon DNA damage occurs at least in part at the level of protein stability (15, 56). To determine whether Itch or RACK1 is involved in ΔNp63 destabilization upon DNA damage, we reduced RACK1 or Itch expression via siRNAs and analyzed ΔNp63 levels following treatment with etoposide or camptothecin. Compared to cells transfected with the control oligo, we found that the degradation of ΔNp63 was indeed partially suppressed after RACK1 expression was downregulated (Fig. 7C), confirming a previous report (15). In contrast, Itch downregulation could not suppress ΔNp63 destabilization under the same conditions (Fig. 7D). These results indicate that DNA damage-induced ΔNp63 turnover also requires RACK1 but not Itch.

FIG. 7.

ΔNp63 and Stxbp4 are downregulated upon DNA damage. (A) HaCaT cells were treated with 300 nM camptothecin (CPT) for the indicated time points. Cells were collected for both immunoblotting (W.B.) (top two panels) and RT-PCR with primers specific for ΔNp63 or β-actin mRNAs (bottom two panels). (B) An H1299 Tet-off cell line was cultured in medium without tetracycline to induce ΔNp63α expression for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 300 nM CPT and 30 μΜ etoposide (ETP) for 21 h and processed for immunoblotting. (C and D) HaCaT cells were transfected with siRNAs for RACK1, Itch, or control (luciferase [Luc]). At 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with either 30 μΜ ETP or 300 nM CPT for 24 h and processed for immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. HaCaT cells were treated with either 30 μΜ ETP or 300 nM CPT for 24 h (E) or with 300 nM CPT for the indicated time points (F). Cells were processed for immunoblotting to detect Stxbp4, p63, and actin. Molecular weights (in thousands) are indicated on the left.

Since Stxbp4 is critical for stabilizing basal ΔNp63 levels, we went on to determine whether Stxbp4 is also modulated after DNA damage. Interestingly, following treatment with etoposide and camptothecin, the level of endogenous Stxbp4 was downregulated (Fig. 7E). Stxbp4 levels decreased in a time-dependent manner, paralleled by the downregulation of p63 proteins (Fig. 7F). Thus, downregulating Stxbp4 in response to genotoxic stress may be part of the mechanism that allows cells to quickly destabilize ΔNp63 through RACK1.

DISCUSSION

ΔNp63 is the predominant p63 isoform expressed in the basal layer of stem cells containing stratified epithelia (35). Although its expression is not restricted to stem cells, p63 is indeed essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia (43, 49). In addition, ΔNp63 protein is overexpressed in squamous epithelium cancers, and its oncogenic potential has been highlighted by a number of reports (19, 42, 45). In our study, we used a human keratinocyte model cell line to investigate the function and regulation of ΔNp63. We found that inhibition of endogenous ΔNp63 blocks cell cycle progression and promotes senescence. This is in agreement with results obtained from both human primary keratinocytes and mouse models (11, 24, 52).

Given its essential role in both normal and cancerous epithelium cells, it is critical to elucidate how ΔNp63 expression is regulated. At the transcriptional level, ΔNp63 mRNA can be upregulated by the epidermal growth factor receptor but down-modulated by the Notch signaling pathway (1, 33, 39). In addition, the p63 gene is frequently amplified in SCC, which correlates with increased p63 mRNA levels (19). Here we found that ΔNp63 protein stability can also be tightly regulated by two of its interacting partners, Stxbp4 and RACK1, and showed that they work in opposite fashions.

Stxbp4 is a WW domain-containing protein (21), and its function in human cells has not been documented. While its mouse homolog Synip can inhibit glucose transporter 4 translocation (38), our data suggest that Stxbp4 can also directly bind p63 and is indispensable for stabilizing ΔNp63 under normal conditions. Notably, YAP, another WW domain protein, can stabilize TAp73 by preventing Itch-induced degradation (9, 28), highlighting the importance of WW domain proteins in regulating the protein stability of p53 family members. In fact, while Itch regulates TAp73 levels, it is not required for DNA damage-induced destabilization of ΔNp73 (46). Likewise, we also found that Stxbp4 can inhibit ΔNp63 degradation mediated by overexpressed Itch. However, our results indicate that endogenous Itch is not the key E3 ligase that is counteracted by Stxbp4, although Itch was suggested to play a role in downregulating ΔNp63 during keratinocyte differentiation (46). Our search for the endogenous ΔNp63 degradation pathway led us to discover RACK1 as the major player in degrading ΔNp63.

RACK1 is another kind of scaffold protein containing seven WD-40 repeats that form a seven-bladed β propeller structure and mediate multiprotein interactions (34). Interestingly, WD-40 repeats are commonly used by proteins that target substrates for degradation through multisubunit E3 ligases, such as Cdh1 and Cdc20, two activators of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (25, 64). Now we and others have shown that RACK1 can bind ΔNp63 and efficiently trigger ΔNp63 degradation (15; this study). The detailed mechanism by which RACK1 degrades ΔNp63 awaits further investigation. Liu et al. showed that RACK1 can recruit a Cullin2-based multisubunit E3 ligase to degrade HIF-1α (31). RACK1 uses its last three WD40 repeats to bind both HIF-1α and Elongin-C, a component of the Cullin2 E3 ligase complex. Interestingly, the last three WD40 repeats of RACK1 also interact with the C-terminal portion of p63α in our yeast two-hybrid screen. Perhaps this provides a molecular basis for ΔNp63, like HIF-1α, to be targeted for degradation by RACK1. Further studies are required to investigate whether, similar to HIF-1α, RACK1 requires the Cullin2 E3 ligase complex to degrade ΔNp63. More recently, the E3 ubiquitin ligase WWP1 was shown to bind, ubiquitinate, and degrade p63α proteins (29). Like Stxbp4, WWP1 is a WW-domain protein, and both proteins bind to the same PPPY motif on p63. It would be interesting to determine whether WWP1 is the E3 ligase that is part of the RACK1 complex that degrades ΔNp63.

The stabilizing effect of Stxbp4 on ΔNp63 is reminiscent of the role of HSP90 in protecting HIF-1α from RACK1-mediated degradation (31). How Stxbp4 counteracts RACK1 activity over ΔNp63 warrants further investigation. One possible model is that Stxbp4 competes with a component of the RACK1-E3 ligase complex for binding to p63 in the cell. Another possibility is that RACK1-E3 ligase complex activity might be directly inhibited by Stxbp4.

Although ΔNp63's levels are kept relatively high in unstressed conditions to promote cell growth and/or survival, they are quickly reduced upon DNA damage. Conceivably, downregulating the ΔN proproliferative variants of the p53 family may be required for the cellular response to genotoxic stress. For example, clearance of ΔNp63 could free p53 target genes to be activated by TA isoforms of the p53 family (2, 45). We and others have found that the downregulation of ΔNp63 upon DNA damage occurs in part through protein degradation (Fig. 7) (15, 56). Even though Itch may modulate p63 stability under certain conditions, reducing endogenous Itch via siRNAs does not prevent ΔNp63 degradation in response to DNA damage (Fig. 7D). This is in line with the fact that Itch does not degrade ΔNp73 upon DNA damage, although it does regulate TAp73 (47). Itch is thus unlikely to be the key E3 ligase controlling ΔNp63 stability under the same conditions. Rather, we and others suggest that the RACK1 pathway is involved in degrading ΔNp63 upon DNA damage (Fig. 7C) (15). Then how is RACK1, normally suppressed by Stxbp4, activated to degrade ΔNp63 under such conditions? Here we provide a possible explanation by showing that Stxbp4 itself is downregulated upon genotoxic stress. Given its key role in stabilizing ΔNp63 in unstressed conditions, Stxbp4 downregulation upon DNA damage might serve as part of the mechanisms that activate RACK1 for ΔNp63 destabilization.

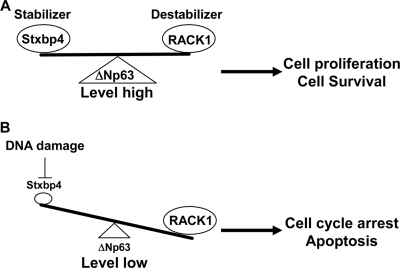

In conclusion, we have provided major and important insights into how ΔNp63 levels are balanced by two of its binding proteins, Stxbp4 and RACK1. Our data support the model that RACK1 degrades ΔNp63 protein under both normal and DNA-damaging conditions. In unstressed situations, ΔNp63 proteins are kept stable by Stxbp4, which in turn suppresses RACK1 activity (Fig. 8A). Upon DNA damage, Stxbp4 itself is downregulated, allowing ΔNp63 to be rapidly destabilized (Fig. 8B). Given the critical role of ΔNp63 in epithelium stem cells and SCC, a detailed mechanistic study about the regulation of p63 protein stability is a very intriguing subject. Our findings also imply that manipulating the protein-protein interaction between Stxbp4 and ΔNp63 might be of some therapeutic value to treat cancers that overexpress ΔNp63. For example, since knockdown of ΔNp63 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma can induce p73-dependent apoptosis (45), efforts aimed at disrupting the interaction between Stxbp4 and p63 using peptidomimetics or small molecules might be able to destabilize ΔNp63 in those cells and therefore be potentially useful in killing those cancers.

FIG. 8.

Models for the regulation of ΔNp63 stability under normal growth conditions and in response to DNA damage. (A) In resting conditions, ΔNp63 is expressed at a relatively high level to promote cell proliferation and/or survival. Its basal level is maintained by Stxbp4, which suppresses RACK1-mediated degradation. (B) Following DNA damage, Stxbp4 itself is downregulated, allowing RACK1 to target ΔNp63 for degradation, which eventually leads to cell cycle arrest or cell death.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank previous and current Prives lab members for their support during this project, with special thanks to Charles J. Di Como for his initial efforts in generating p63 polyclonal antibodies, Christopher Nuesch for his involvement in studying the p63 DNA damage response, and Ella Freulich for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by a C. J. Martin fellowship from the NHMRC of Australia to M.J.P. and by NIH grant CA87497.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbieri, C. E., C. E. Barton, and J. A. Pietenpol. 2003. ΔNp63α expression is regulated by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 27851408-51414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbieri, C. E., C. A. Perez, K. N. Johnson, K. A. Ely, D. Billheimer, and J. A. Pietenpol. 2005. IGFBP-3 is a direct target of transcriptional regulation by ΔNp63α in squamous epithelium. Cancer Res. 652314-2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanpain, C., and E. Fuchs. 2007. p63: revving up epithelial stem-cell potential. Nat. Cell Biol. 9731-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boukamp, P., R. T. Petrussevska, D. Breitkreutz, J. Hornung, A. Markham, and N. E. Fusenig. 1988. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 106761-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candi, E., A. Rufini, A. Terrinoni, D. Dinsdale, M. Ranalli, A. Paradisi, V. De Laurenzi, L. G. Spagnoli, M. V. Catani, S. Ramadan, R. A. Knight, and G. Melino. 2006. Differential roles of p63 isoforms in epidermal development: selective genetic complementation in p63 null mice. Cell Death Differ. 131037-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll, D. K., J. S. Carroll, C. O. Leong, F. Cheng, M. Brown, A. A. Mills, J. S. Brugge, and L. W. Ellisen. 2006. p63 regulates an adhesion programme and cell survival in epithelial cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 8551-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, W. M., W. Y. Siu, A. Lau, and R. Y. Poon. 2004. How many mutant p53 molecules are needed to inactivate a tetramer? Mol. Cell. Biol. 243536-3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, E. C., M. Barr, Y. Wang, V. Jung, H. P. Xu, and M. H. Wigler. 1994. Cooperative interaction of S. pombe proteins required for mating and morphogenesis. Cell 79131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danovi, S. A., M. Rossi, K. Gudmundsdottir, M. Yuan, G. Melino, and S. Basu. 2007. Yes-associated protein (YAP) is a critical mediator of c-Jun-dependent apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 151752-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davison, T. S., C. Vagner, M. Kaghad, A. Ayed, D. Caput, and C. H. Arrowsmith. 1999. p73 and p63 are homotetramers capable of weak heterotypic interactions with each other but not with p53. J. Biol. Chem. 27418709-18714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deyoung, M. P., C. M. Johannessen, C. O. Leong, W. Faquin, J. W. Rocco, and L. W. Ellisen. 2006. Tumor-specific p73 up-regulation mediates p63 dependence in squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 669362-9368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohn, M., S. Zhang, and X. Chen. 2001. p63α and ΔNp63α can induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and differentially regulate p53 target genes. Oncogene 203193-3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elbashir, S. M., J. Harborth, W. Lendeckel, A. Yalcin, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. 2001. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 411494-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flores, E. R., S. Sengupta, J. B. Miller, J. J. Newman, R. Bronson, D. Crowley, A. Yang, F. McKeon, and T. Jacks. 2005. Tumor predisposition in mice mutant for p63 and p73: evidence for broader tumor suppressor functions for the p53 family. Cancer Cell 7363-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fomenkov, A., R. Zangen, Y. P. Huang, M. Osada, Z. Guo, T. Fomenkov, B. Trink, D. Sidransky, and E. A. Ratovitski. 2004. RACK1 and stratifin target ΔNp63α for a proteasome degradation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells upon DNA damage. Cell Cycle 31285-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghioni, P., F. Bolognese, P. H. Duijf, H. Van Bokhoven, R. Mantovani, and L. Guerrini. 2002. Complex transcriptional effects of p63 isoforms: identification of novel activation and repression domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 228659-8668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gressner, O., T. Schilling, K. Lorenz, E. Schulze Schleithoff, A. Koch, H. Schulze-Bergkamen, A. Maria Lena, E. Candi, A. Terrinoni, M. Valeria Catani, M. Oren, G. Melino, P. H. Krammer, W. Stremmel, and M. Muller. 2005. TAp63α induces apoptosis by activating signaling via death receptors and mitochondria. EMBO J. 242458-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helton, E. S., J. Zhu, and X. Chen. 2006. The unique NH2-terminally deleted (DeltaN) residues, the PXXP motif, and the PPXY motif are required for the transcriptional activity of the DeltaN variant of p63. J. Biol. Chem. 2812533-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hibi, K., B. Trink, M. Patturajan, W. H. Westra, O. L. Caballero, D. E. Hill, E. A. Ratovitski, J. Jen, and D. Sidransky. 2000. AIS is an oncogene amplified in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 975462-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, Y. P., G. Wu, Z. Guo, M. Osada, T. Fomenkov, H. L. Park, B. Trink, D. Sidransky, A. Fomenkov, and E. A. Ratovitski. 2004. Altered sumoylation of p63α contributes to the split-hand/foot malformation phenotype. Cell Cycle 31587-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingham, R. J., K. Colwill, C. Howard, S. Dettwiler, C. S. Lim, J. Yu, K. Hersi, J. Raaijmakers, G. Gish, G. Mbamalu, L. Taylor, B. Yeung, G. Vassilovski, M. Amin, F. Chen, L. Matskova, G. Winberg, I. Ernberg, R. Linding, P. O'Donnell, A. Starostine, W. Keller, P. Metalnikov, C. Stark, and T. Pawson. 2005. WW domains provide a platform for the assembly of multiprotein networks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 257092-7106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs, W. B., G. Govoni, D. Ho, J. K. Atwal, F. Barnabe-Heider, W. M. Keyes, A. A. Mills, F. D. Miller, and D. R. Kaplan. 2005. p63 is an essential proapoptotic protein during neural development. Neuron 48743-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keyes, W. M., H. Vogel, M. I. Koster, X. Guo, Y. Qi, K. M. Petherbridge, D. R. Roop, A. Bradley, and A. A. Mills. 2006. p63 heterozygous mutant mice are not prone to spontaneous or chemically induced tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1038435-8440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keyes, W. M., Y. Wu, H. Vogel, X. Guo, S. W. Lowe, and A. A. Mills. 2005. p63 deficiency activates a program of cellular senescence and leads to accelerated aging. Genes Dev. 191986-1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraft, C., H. C. Vodermaier, S. Maurer-Stroh, F. Eisenhaber, and J. M. Peters. 2005. The WD40 propeller domain of Cdh1 functions as a destruction box receptor for APC/C substrates. Mol. Cell 18543-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraus, S., D. Gioeli, T. Vomastek, V. Gordon, and M. J. Weber. 2006. Receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) and Src regulate the tyrosine phosphorylation and function of the androgen receptor. Cancer Res. 6611047-11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, H. O., J. H. Lee, E. Choi, J. Y. Seol, Y. Yun, and H. Lee. 2006. A dominant negative form of p63 inhibits apoptosis in a p53-independent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 344166-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy, D., Y. Adamovich, N. Reuven, and Y. Shaul. 2007. The Yes-associated protein 1 stabilizes p73 by preventing Itch-mediated ubiquitination of p73. Cell Death Differ. 14743-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, Y., Z. Zhou, and C. Chen. 2008. WW domain-containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 targets p63 transcription factor for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation and regulates apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 151941-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liefer, K. M., M. I. Koster, X. J. Wang, A. Yang, F. McKeon, and D. R. Roop. 2000. Down-regulation of p63 is required for epidermal UV-B-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 604016-4020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, Y. V., J. H. Baek, H. Zhang, R. Diez, R. N. Cole, and G. L. Semenza. 2007. RACK1 competes with HSP90 for binding to HIF-1α and is required for O(2)-independent and HSP90 inhibitor-induced degradation of HIF-1α. Mol. Cell 25207-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchbank, A., L. J. Su, P. Walsh, J. DeGregori, K. Penheiter, T. B. Grayson, R. P. Dellavalle, and L. A. Lee. 2003. The CUSP ΔNp63α isoform of human p63 is downregulated by solar-simulated ultraviolet radiation. J. Dermatol. Sci. 3271-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matheny, K. E., C. E. Barbieri, J. C. Sniezek, C. L. Arteaga, and J. A. Pietenpol. 2003. Inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling decreases p63 expression in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Laryngoscope 113936-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCahill, A., J. Warwicker, G. B. Bolger, M. D. Houslay, and S. J. Yarwood. 2002. The RACK1 scaffold protein: a dynamic cog in cell response mechanisms. Mol. Pharmacol. 621261-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKeon, F. 2004. p63 and the epithelial stem cell: more than status quo? Genes Dev. 18465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mills, A. A. 2006. p63: oncogene or tumor suppressor? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1638-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills, A. A., B. Zheng, X. J. Wang, H. Vogel, D. R. Roop, and A. Bradley. 1999. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398708-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Min, J., S. Okada, M. Kanzaki, J. S. Elmendorf, K. J. Coker, B. P. Ceresa, L. J. Syu, Y. Noda, A. R. Saltiel, and J. E. Pessin. 1999. Synip: a novel insulin-regulated syntaxin 4-binding protein mediating GLUT4 translocation in adipocytes. Mol. Cell 3751-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen, B. C., K. Lefort, A. Mandinova, D. Antonini, V. Devgan, G. Della Gatta, M. I. Koster, Z. Zhang, J. Wang, A. Tommasi di Vignano, J. Kitajewski, G. Chiorino, D. R. Roop, C. Missero, and G. P. Dotto. 2006. Cross-regulation between Notch and p63 in keratinocyte commitment to differentiation. Genes Dev. 201028-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osada, M., M. Ohba, C. Kawahara, C. Ishioka, R. Kanamaru, I. Katoh, Y. Ikawa, Y. Nimura, A. Nakagawara, M. Obinata, and S. Ikawa. 1998. Cloning and functional analysis of human p51, which structurally and functionally resembles p53. Nat. Med. 4839-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozaki, T., K. Watanabe, T. Nakagawa, K. Miyazaki, M. Takahashi, and A. Nakagawara. 2003. Function of p73, not of p53, is inhibited by the physical interaction with RACK1 and its inhibitory effect is counteracted by pRB. Oncogene 223231-3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patturajan, M., S. Nomoto, M. Sommer, A. Fomenkov, K. Hibi, R. Zangen, N. Poliak, J. Califano, B. Trink, E. Ratovitski, and D. Sidransky. 2002. ΔNp63 induces beta-catenin nuclear accumulation and signaling. Cancer Cell 1369-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pellegrini, G., E. Dellambra, O. Golisano, E. Martinelli, I. Fantozzi, S. Bondanza, D. Ponzin, F. McKeon, and M. De Luca. 2001. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 983156-3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez-Losada, J., D. Wu, R. DelRosario, A. Balmain, and J. H. Mao. 2005. p63 and p73 do not contribute to p53-mediated lymphoma suppressor activity in vivo. Oncogene 245521-5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocco, J. W., C. O. Leong, N. Kuperwasser, M. P. DeYoung, and L. W. Ellisen. 2006. p63 mediates survival in squamous cell carcinoma by suppression of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell 945-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rossi, M., R. I. Aqeilan, M. Neale, E. Candi, P. Salomoni, R. A. Knight, C. M. Croce, and G. Melino. 2006. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch controls the protein stability of p63. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10312753-12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossi, M., V. De Laurenzi, E. Munarriz, D. R. Green, Y. C. Liu, K. H. Vousden, G. Cesareni, and G. Melino. 2005. The ubiquitin-protein ligase Itch regulates p73 stability. EMBO J. 24836-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossi, M., M. De Simone, A. Pollice, R. Santoro, G. La Mantia, L. Guerrini, and V. Calabro. 2006. Itch/AIP4 associates with and promotes p63 protein degradation. Cell Cycle 51816-1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senoo, M., F. Pinto, C. P. Crum, and F. McKeon. 2007. p63 is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia. Cell 129523-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strano, S., E. Munarriz, M. Rossi, L. Castagnoli, Y. Shaul, A. Sacchi, M. Oren, M. Sudol, G. Cesareni, and G. Blandino. 2001. Physical interaction with Yes-associated protein enhances p73 transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 27615164-15173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suh, E. K., A. Yang, A. Kettenbach, C. Bamberger, A. H. Michaelis, Z. Zhu, J. A. Elvin, R. T. Bronson, C. P. Crum, and F. McKeon. 2006. p63 protects the female germ line during meiotic arrest. Nature 444624-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Truong, A. B., M. Kretz, T. W. Ridky, R. Kimmel, and P. A. Khavari. 2006. p63 regulates proliferation and differentiation of developmentally mature keratinocytes. Genes Dev. 203185-3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urist, M., T. Tanaka, M. V. Poyurovsky, and C. Prives. 2004. p73 induction after DNA damage is regulated by checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2. Genes Dev. 183041-3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Urist, M. J., C. J. Di Como, M. L. Lu, E. Charytonowicz, D. Verbel, C. P. Crum, T. A. Ince, F. D. McKeon, and C. Cordon-Cardo. 2002. Loss of p63 expression is associated with tumor progression in bladder cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 1611199-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vojtek, A. B., S. M. Hollenberg, and J. A. Cooper. 1993. Mammalian Ras interacts directly with the serine/threonine kinase Raf. Cell 74205-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Westfall, M. D., A. S. Joyner, C. E. Barbieri, M. Livingstone, and J. A. Pietenpol. 2005. Ultraviolet radiation induces phosphorylation and ubiquitin-mediated degradation of ΔNp63α. Cell Cycle 4710-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westfall, M. D., D. J. Mays, J. C. Sniezek, and J. A. Pietenpol. 2003. The ΔNp63α phosphoprotein binds the p21 and 14-3-3σ promoters in vivo and has transcriptional repressor activity that is reduced by Hay-Wells syndrome-derived mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 232264-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winberg, G., L. Matskova, F. Chen, P. Plant, D. Rotin, G. Gish, R. Ingham, I. Ernberg, and T. Pawson. 2000. Latent membrane protein 2A of Epstein-Barr virus binds WW domain E3 protein-ubiquitin ligases that ubiquitinate B-cell tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 208526-8535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu, G., S. Nomoto, M. O. Hoque, T. Dracheva, M. Osada, C. C. Lee, S. M. Dong, Z. Guo, N. Benoit, Y. Cohen, P. Rechthand, J. Califano, C. S. Moon, E. Ratovitski, J. Jen, D. Sidransky, and B. Trink. 2003. ΔNp63α and TAp63α regulate transcription of genes with distinct biological functions in cancer and development. Cancer Res. 632351-2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu, G., M. Osada, Z. Guo, A. Fomenkov, S. Begum, M. Zhao, S. Upadhyay, M. Xing, F. Wu, C. Moon, W. H. Westra, W. M. Koch, R. Mantovani, J. A. Califano, E. Ratovitski, D. Sidransky, and B. Trink. 2005. ΔNp63α up-regulates the Hsp70 gene in human cancer. Cancer Res. 65758-766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang, A., M. Kaghad, D. Caput, and F. McKeon. 2002. On the shoulders of giants: p63, p73 and the rise of p53. Trends Genet. 1890-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang, A., M. Kaghad, Y. Wang, E. Gillett, M. D. Fleming, V. Dotsch, N. C. Andrews, D. Caput, and F. McKeon. 1998. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol. Cell 2305-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang, A., R. Schweitzer, D. Sun, M. Kaghad, N. Walker, R. T. Bronson, C. Tabin, A. Sharpe, D. Caput, C. Crum, and F. McKeon. 1999. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398714-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu, H. 2007. Cdc20: a WD40 activator for a cell cycle degradation machine. Mol. Cell 273-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zupnick, A., and C. Prives. 2006. Mutational analysis of the p53 core domain L1 loop. J. Biol. Chem. 28120464-20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]