Abstract

Thermococcus species are widely distributed in terrestrial and marine hydrothermal areas, as well as in deep subsurface oil reservoirs. Thermococcus sibiricus is a hyperthermophilic anaerobic archaeon isolated from a well of the never flooded oil-bearing Jurassic horizon of a high-temperature oil reservoir. To obtain insight into the genome of an archaeon inhabiting the oil reservoir, we have determined and annotated the complete 1,845,800-base genome of T. sibiricus. A total of 2,061 protein-coding genes have been identified, 387 of which are absent in other members of the order Thermococcales. Physiological features and genomic data reveal numerous hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., cellulolytic enzymes, agarase, laminarinase, and lipases) and metabolic pathways, support the proposal of the indigenous origin of T. sibiricus in the oil reservoir, and explain its survival over geologic time and its proliferation in this habitat. Indeed, in addition to proteinaceous compounds known previously to be present in oil reservoirs at limiting concentrations, its growth was stimulated by cellulose, agarose, and triacylglycerides, as well as by alkanes. Two polysaccharide degradation loci were probably acquired by T. sibiricus from thermophilic bacteria following lateral gene transfer events. The first, a “saccharolytic gene island” absent in the genomes of other members of the order Thermococcales, contains the complete set of genes responsible for the hydrolysis of cellulose and β-linked polysaccharides. The second harbors genes for maltose and trehalose degradation. Considering that agarose and laminarin are components of algae, the encoded enzymes and the substrate spectrum of T. sibiricus indicate the ability to metabolize the buried organic matter from the original oceanic sediment.

Thermococcus sibiricus is a hyperthermophilic anaerobic archaeon isolated from a well of the never flooded oil-bearing Jurassic horizon of the high-temperature Samotlor oil reservoir (Western Siberia) (32). The sampling site had a temperature of 84°C and was located at a depth of 2,350 m. Thermococcus species are widely distributed in terrestrial and marine hydrothermal areas (4), as well as in deep subsurface oil reservoirs (38, 53). Close relatives of T. sibiricus with a 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity of >99% were identified in high-temperature oil wells of Japan (54) and China (36). Together with the genera Pyrococcus and Palaeococcus, Thermococcus spp. form the euryarchaeal order Thermococcales (4). Most of these hyperthermophilic archaea are organoheterotrophs that utilize proteins, starch, and maltose with elemental sulfur (S°) or protons as electron acceptors (4, 47). Two exceptions are Thermococcus strain AM4 (51) and Thermococcus onnurineus (23), which are also capable of lithotrophic CO-dependent hydrogenogenic growth (52).

Genomic sequences of T. onnurineus (23), Thermococcus kodakaraensis (11), Pyrococcus horikoshii (18), Pyrococcus furiosus (44), and Pyrococcus abyssi (7) provided information on the genetic and metabolic machinery of these closely related organisms. However, none of them originated from deep subsurface oil reservoirs. These habitats contain low levels of dissolved organic carbon and trace amounts of free amino acids (53) but harbor high numbers of anaerobic organisms, reaching 1.4 × 106 cells ml−1 (38). T. sibiricus was originally reported to grow exclusively on peptides (32). The organism was obtained from a sample of an oil-bearing Jurassic horizon that had never been flooded. The temperature, pH, and salinity characteristics for growth correlated with the natural conditions at the sampling site. Therefore, an indigenous origin was suggested for T. sibiricus, which might have survived over geologic time by metabolizing buried organic matter from the original oceanic sediment (32).

Here we present the genome of T. sibiricus and show that it encodes numerous hydrolytic enzymes and metabolic pathways which may allow the utilization of diverse organic polymers from the original oceanic sediment. Our experiments provide evidence for these new physiological features and support the suggestion of the indigenous origin of T. sibiricus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation of T. sibiricus.

T. sibiricus MM 739 (DSM 12597) (32) was obtained from the culture collection of the Laboratory of Hyperthermophilic Microbial Communities, Winogradsky Institute of Microbiology of the Russian Academy of Sciences. For the isolation of DNA, T. sibiricus was grown anaerobically at 78°C in an atmosphere of 80% N2 and 20% CO2 in basal mineral medium supplemented with peptone (5 g liter−1), yeast extract (0.1 g liter−1), and S° (10 g liter−1) as described previously (32). Cells were harvested in the early exponential growth phase, and genomic DNA was isolated according to the Marmur procedure (30).

Potential growth-supporting substrates were identified by the cultivation of T. sibiricus under strictly anaerobic conditions at 78°C in basal medium (32) supplemented with yeast extract (0.06 g liter−1) and S° (10 g liter−1). The following substrates were tested: peptone, starch, maltose, dextran, amorphous cellulose, carboxymethyl cellulose, microcrystalline cellulose, agarose, chitin, xylan, pectin (all at 2 g liter−1), maltose (10 mM), cellobiose (10 mM), phenol (0.5 mM), toluene (0.5 mM), hexadecane, acetone, sodium linoleate, sodium palmitate (all at 1 mM), olive oil (1 ml liter−1), glycerol (1 ml liter−1), and CO (100% in the gas phase). The ability to grow on peptone, maltose, and CO was analyzed in the absence of S° as well. Growth was determined by direct cell counting with a phase-contrast microscope.

Genome sequencing.

The T. sibiricus genome was sequenced on a Roche GS FLX genome sequencer by the standard protocol for a shotgun genome library. The GS FLX run resulted in the generation of about 70 Mb of sequences with an average read length of 230 bp. The GS FLX reads were assembled into four large contigs by GS De Novo Assembler. The 454 contigs were oriented into scaffolds, and the complete genome sequence was obtained upon the generation and sequencing of appropriate PCR fragments. The assembly of the genome at sites with IS elements was verified by PCR amplification and sequencing of these regions.

Genome annotation and analysis.

The rRNA genes were identified by searching against the Rfam database (12). tRNA genes were located with tRNAscan-SE (27). Protein-coding genes were identified with the GLIMMER gene finder (8). Whole-genome annotation and analysis were performed with the AutoFACT annotation tool (21). Clusters of regularly interspaced repeats (CRISPR) were identified with CRISPR Finder (13); putative transposon-related proteins were found by searching against the IS database (http://www-is.biotoul.fr/is.html). Signal peptides were predicted with SignalP v. 3.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) by using the HMM algorithm.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The annotated genome sequence has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. CP001463.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General features.

T. sibiricus has a single circular chromosome of 1,845,800 bp with no extrachromosomal elements (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). There are a single copy of a 16S-23S rRNA operon and two distantly located 5S rRNA genes. A total of 46 tRNA genes carrying 44 different anticodons coding for all 20 amino acids are scattered over the genome.

By a combination of coding potential prediction and similarity search, 2,061 potential protein-coding genes were identified with an average length of 815 bp, covering 91% of the genome. These values are in good accordance with the general correlation between the microbial genome size and the predicted gene numbers. Through similarity and domain searches of the predicted protein products, the functions of 69% of the genes (1,413 genes) may be predicted with different degrees of confidence and generalization. The functions of the remaining 648 genes (31%) cannot be predicted from the deduced amino acid sequences; 181 of them are unique to T. sibiricus, with no significant similarity to any known sequences.

About 70% of the T. sibiricus proteins showed similarity to those of T. kodakaraensis and T. onnurineus (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and 1,024 of them are also present in all three Pyrococcus species. This shared set of genes might belong to the common ancestor of members of the order Thermococcales. About 387 of the T. sibiricus proteins are not present in other members of the order Thermococcales, and although many of them encode proteins with unknown function, there are several intriguing genes that might be responsible for the specific traits of T. sibiricus, as discussed below.

Pairwise comparison by all-vs-all BLASTP of the genomes of T. sibiricus and other Thermococcus spp. confirmed the high frequency of shuffling-driven genome rearrangements (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast to the well-conserved gene context among Pyrococcus genomes, the genomes of thermococci are more rearranged and the synteny is conserved only for short chromosomal segments.

Mobile genetic elements.

Analysis of the repeated sequences and a search against the IS database revealed seven copies of putative transposons of three types. We found two almost identical complete copies of an IS605 family transposon, which was named ISTSi1. This 1,856-bp-long IS element contains two genes, orfA and orfB, that encode homologs of the resolvase (COG2452) and transposase (COG0675) of IS605. The almost identical sequences of two copies of ISTsi1 suggest that this IS element invaded the T. sibiricus genome recently on the evolutionary time scale and may remain functional. ISTsi1-like sequences are also present in the genomes of other Thermococcus species.

Another IS element of the IS605 family, ISTsi2, is present in two almost identical copies. This 1,398-bp-long IS element contains a pseudogene of an IS605 family transposase (orfB, COG0675) carrying three frameshift mutations. In addition, a shortened copy of this IS element (1,359 bp), also carrying a transposase pseudogene, was found. Perhaps the propagation of this already nonfunctional IS element depends on another active transposon. The only archaeal homologue of the “restored” transposase of ISTsi2 is the PF1609 protein of P. furiosus; many others are encoded in the genomes of thermophilic bacteria (Caldicellulosiruptor, Anaerocellum, Geobacillus, etc.), suggesting ancient invasion of the genome of the common ancestor of members of the order Thermococcales by this IS element.

The third IS element, ISTsi3, belongs to the IS200/IS600 family and is present in one full-size copy (1,884 bp) and two shortened copies (1,630 bp and 1,626 bp). The full-size copy contains two genes (COG1943 and COG0675), while the shorter copies harbor only the longer gene, orfB (COG0675). Note that proteins similar to OrfB are encoded in the genomes of other Thermococcus species but OrfA-like proteins are present only in crenarchaeal and bacterial genomes.

In the crenarchaeal genus Sulfolobus, site-specific integration of viruses occurs at tRNA genes by the integrase-mediated mechanism (39). Such regions bordered by a partitioned integrase gene have been found in other members of the order Thermococcales, P. horikoshii, and T. kodakaraensis (11). In particular, the T. kodakaraensis genome contains four such regions comprising 18 to 28 kb each and encoding several genes, including genes related to DNA replication (11). The search for similar integrated viruses in the T. sibiricus genome revealed only one such region, bordered by a partitioned integrase homologues to the integrase from the SSV1 virus for Sulfolobus shibatae. This region is much shorter (2.7 kb) than virus-related regions present in the T. kodakaraensis genome and contains only a single gene (Tsib_0741), thus probably representing the late stage of elimination of the integrated virus-related element from the genome.

The T. sibiricus genome contains a single CRISPR containing 24 repeat spacer units. The spacer regions are supposed to be derived from extrachromosomal elements like viruses (33), and the spacer transcripts may inactivate mobile-element propagation by a mechanism somewhat similar to eukaryotic RNA interference (2, 26). We found no matches between the spacer sequences and any known archaeal extrachromosomal genetic elements, and no CRISPR spacer matched the sequences of the IS elements present in the T. sibiricus genome. Other representatives of the order Thermococcales generally harbor multiple CRISPR loci (11) carrying more repeat spacer units. This difference may reflect the constant and relatively noncompetitive natural environment of T. sibiricus, which is rarely invaded by viruses and other mobile elements.

DNA replication.

The archaeal chromosomal replication initiation site (oriC) was first identified in P. abyssi within the noncoding region located upstream of a gene that encodes a homolog of the eukaryotic Orc1/Cdc6 cell division control protein (35). Members of the order Thermococcales contain a single replication initiation site, while some other archaea, for example, Sulfolobus species, carry multiple chromosomal replication origins, and multiple cdc6 genes were found to be located close to them (31, 45). In three Pyrococcus species, ori regions contain a pair of conserved origin recognition box (ORB) sequences, the Orc1/Cdc6 protein binding sites, separated by an ∼250-bp spacer region (45). Likewise, the ori site of T. kodakaraensis is located in an AT-rich region located upstream of a gene for the Orc1/Cdc6 homolog (11). Usually, the ori sites are also linked to a “replication island,” a variety of replication- and recombination-associated genes (e.g., polymerase, rfc, radA, helicase, etc.).

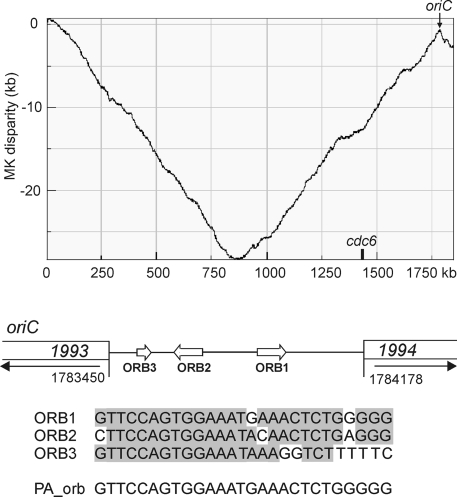

Nucleotide composition disparity analysis (Z-curve analysis) (57) of the T. sibiricus genome showed one major peak at around 1.78 Mb where nucleotide compositional deviation change occurred (Fig. 1). This peak was found for the MK disparity component of the Z curve, as observed for the Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (5) and Pyrobaculum aerophilum (57) chromosomal ori sites. The search for ORB sequences (45, 46) revealed that the noncoding region located between the Tsib_1993 and Tsib_1994 genes (functions unknown) contains two ORB sequences, as well as an additional partial copy of this motif (Fig. 1). As in pyrococci, two full copies of the ORB sequence are oriented in opposite directions and separated by a 250-bp spacer. The position of this region coincides with the location of the MK disparity peak (Fig. 1), further supporting the hypothesis that the ori site is located at this point.

FIG. 1.

Z-curve analysis of the T. sibiricus genome (the MK disparity component is presented) showing the major peaks where nucleotide compositional deviations occur. On the genome map, the cdc6 gene is shown. At the bottom, the structure of the predicted oriC region is shown. Open arrows indicate the position and direction of ORB elements. The nucleotide sequences of ORB1, ORB2, and ORB3, as well as ORB of P. abyssi (PA_orb) are presented. Open rectangles show the open reading frames flanking the ori site, and arrows indicate the direction of transcription. Nucleotides conserved in at least two ORB sequences are shaded.

The orc1/cdc6 homologue is present in the T. sibiricus genome (Tsib_1590), but unlike in other members of the order Thermococcales, it is located distantly from the potential oriC site and no ORB-like sequences were found around this gene. The replication island near oriC is most complete in P. abyssi and P. horikoshii, while in T. kodakaraensis it is separated into two regions, where genes for the Orc1/Cdc6 homolog and DNA polymerase are 290 kb away from the genes for the RadB and RF-C subunits (11). The genome of T. sibiricus is more rearranged; only the radA gene (Tsib_1992) remains to be associated with oriC. Two other regions are located distantly from this site—the cdc6 gene (Tsib_1590) linked to DNA polymerase II subunits (Tsib_1588 and Tsib_1589) and the third region comprising the rfc (Tsib_0101 and Tsib_0102) and radB (Tsib_0108) genes. It is possible that the more condensed replication island structure in Pyrococcus species reflects specific adaptation of their DNA replication machinery to extreme thermophily (98 to 103°C) relative to thermococci growing at considerably lower temperatures (80 to 90°C).

Growth of T. sibiricus on different substrates.

T. sibiricus was originally reported to grow on proteinaceous substrates, peptone, yeast extract, beef extract, and soya bean extract, but not on starch, pyruvate, glucose, acetate, methanol, ethanol, lactate, or H2/CO2 (32). S° as an electron acceptor was not obligately required but stimulated growth.

Analysis of the T. sibiricus genome revealed the presence of genes required for protein export systems, and the SignalP algorithm predicted a total of 281 proteins carrying N-terminal signal sequences. Most of them have been annotated as transporters, proteases, glycoside hydrolases, lipases/esterases, and hypothetical proteins. The encoded proteins suggested the ability of T. sibiricus to utilize additional substrates. Therefore, in this work we attempted to adapt the organism to growth on some substrates whose utilization could be expected from the genomic data (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We performed cultivation experiments and, after sequential transfers, identified maltose, dextran, amorphous cellulose, carboxymethyl cellulose, cellobiose, agarose, hexadecane, acetone, olive oil, and glycerol as new substrates for T. sibiricus. Starch, microcrystalline cellulose, chitin, xylan, pectin, phenol, toluene, long-chain fatty acids, and CO did not support its growth (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Metabolism of proteins.

Growth of T. sibiricus on proteins and peptides as the sole source of energy and carbon is enabled by the functioning of two signal peptide-containing extracellular proteases, a pyrolysin-like serine protease (Tsib_0267) and an archaeal subtilisin-like serine protease (Tsib_1234). The cell can import peptides by ABC-type dipeptide/oligopeptide transport system, dipeptide ABC-transporters, and the OPT family oligopeptide transporter. The imported peptides can be cleaved by more than 20 encoded peptidases, including aminopeptidases, carboxypeptidases, and dipeptidases. The amino acids can then be deaminated by a number of aminotransferases (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) in a glutamate dehydrogenase (Tsib_1110)-coupled manner, followed by oxidation to generate the corresponding coenzyme A (CoA) derivatives, as proposed for P. furiosus (1). The oxidation step involves at least four types of ferredoxin-dependent oxidoreductases with distinct substrate specificities (1): pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, 2-ketoisovalerate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, indolepyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, 2-ketoglutarate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, and the second 2-ketoglutarate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). An additional heterodimeric 2-oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, the substrate specificity of which cannot be identified by sequence comparison, may be involved in the oxidation of the acyl-CoA derivates.

The acyl-CoA derivatives in T. sibiricus are converted to the corresponding acids by the two acetyl-CoA synthetases (ACS I and II) and a succinyl-CoA synthetase (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) with concomitant substrate level phosphorylation to generate ATP, as shown in P. furiosus (29) and T. kodakaraensis (49). The pathway involving a two-step transformation of acetyl-CoA to acetate with phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase, which is common in anaerobic bacteria, presumably does not operate in T. sibiricus because homologs of the currently known genes for phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase are absent.

As an alternative assimilation pathway for amino acids, 2-keto acids derived from amino acids can be decarboxylated, depending on the redox balance of the cell, to corresponding aldehydes by ferredoxin-independent reactions of the ferredoxin-dependent oxidoreductases (28) and then oxidized to form carboxylic acids by the function of five aldehyde:ferredoxin oxidoreductases (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs) might be responsible for the reduction of aldehydes to alcohols in the absence of sufficient amounts of the terminal electron acceptor, S°, in the reaction coupled to the oxidation of NADPH to NADP+, which would dispose of excess reductant (28). In the T. sibiricus genome, there are three genes for short-chain ADHs and one gene for Fe-dependent ADH (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Metabolism of carbohydrates.

The genome encodes numerous enzymes for the metabolism of polymeric carbohydrates and oligosaccharides, which correlates with the growth of T. sibiricus on maltose, dextran, amorphous cellulose, carboxymethyl cellulose, cellobiose, and agarose observed in this work. T. sibiricus cannot grow on chitin, xylan, or pectin, which is consistent with the absence of genes that encode chitinases, xylanases, and pectinases in its genome.

The inability of T. sibiricus to grow on starch correlated with the genomic data. Contrary to several Thermococcus and Pyrococcus species, no genes for extracellular amylolytic enzymes were found on the T. sibiricus genome. A single identified α-amylase (Tsib_1115) lacks a signal peptide and is intracellular. T. sibiricus was found to be able to grow on maltose. Extracellular maltose and maltooligasaccharides could be transported into the cell and then hydrolyzed to glucose. The production of glucose could be accomplished by several intracellular enzymes: α-amylase, glycogen-debranching enzyme (Tsib_0365), two α-glucosidases (Tsib_1113 and Tsib_0873), and a 4-α-glucanotransferase (Tsib_0455).

In contrast to starch, T. sibiricus grew quite well on dextran, which is an α-1,6-linked d-glucose polymer branched at α-1,4 linkages. However, no extracellular enzymes for the degradation of dextran could be identified in the genome.

The genome predicts the ability of T. sibiricus to metabolize cellulose, which is in agreement with its observed growth on amorphous cellulose. The T. sibiricus genome encodes a number of β-specific glycoside hydrolases, which form a complete system for cellulose degradation. The Tsib_0320-to-Tsib_0334 gene cluster includes three putative endo-β1,4-glucanases (extracellular Tsib_0326 and Tsib_0328, as well as intracellular Tsib_0327). Both extracellular enzymes are homologous to endo-β-1,4-glucanases CelA (TM1524) and CelB (TM1525) from Thermotoga maritima, which was found to be active against soluble substrates (25), as well as to P. furiosus endo-β-1,4-glucanase EglA (PF0854), which shows maximum activity on C4-to-C6 cellobiose oligosaccharides (3). Like the T. maritima and P. furiosus enzymes, both extracellular endo-β-1,4-glucanases from T. sibiricus do not contain a cellulose-binding domain (58) required to bind to and efficiently hydrolyze crystalline cellulose. This correlates with the inability of T. sibiricus to grow on crystalline cellulose and explains its growth on amorphous cellulose, carboxymethyl cellulose, and cellobiose. The imported cellooligomers are further degraded to smaller oligosaccharides by intracellular endo-β-1,4-glucanases, as suggested for T. maritima (6). At least three such enzymes are encoded by T. sibiricus (Tsib_0327, Tsib_0137, and Tsib_1215).

Like T. neapolitana and T. maritima, T. sibiricus and other archaea do not contain genes for cellobiohydrolase, a key enzyme in classical cellulolytic systems. However, despite the absence of this enzyme, the genome of T. sibiricus encodes an intracellular β-glucan glucohydrolase (Tsib_0580) that displays high homology with functionally characterized intracellular β-glucan glucohydrolase GdhA from Thermotoga neapolitana (56), which has been suggested as a substitute for cellobiohydrolase. The soluble products of the initial hydrolysis of cellulose by endo-β-1,4-glucanases in Thermotoga are then hydrolyzed by intracellular GghA, which preferentially attacks the longer cellooligomers cellotriose to cellohexaose, releasing glucose from the nonreducing end and producing cellobiose (56). Cellobiose can also be hydrolyzed by a β-glucosidase (Tsib_0334) most closely related to functionally characterized P. furiosus β-glucosidase CelA (PF0073) (55). An additional gene product involved in cellulose degradation is Tsib_0320, which encodes a putative intracellular cellobiose phosphorylase. Tsib_0320 is related to functionally characterized intracellular cellobiose phosphorylases CbpA from T. neapolitana (56) and CepA from T. maritima. In Thermotoga sp., cellobiose phosphorylase attacks cellulose-derived cellobiose, producing the activated molecule glucose-1-phosphate and glucose.

The genome encodes an extracellular laminarinase (endo-β-1,3-glucanase, Tsib_0321) highly homologous to functionally characterized laminarinase LamB (PF0076) from P. furiosus and to many bacterial laminarinases. This enzyme acts best on the β-1,3-glucose polymer laminarin, hydrolyzing it into smaller laminari-oligomers; displays some hydrolytic activity with the β-1,3-1,4 glucose polymers lichenan and barley β-glucan; and is not active with the β-1,4 glucose polymer cellulose (15). The source of laminarin in nature is brown algae. Endo-β-1,4-glucanase (cellulase), laminarinase, and β-glucosidase, encoded by the gene cluster Tsib_0320 to Tsib_0334, could perform synergistic activity during the hydrolysis of complex carbohydrates, as demonstrated earlier for barley β-glucan and laminarin (10).

The genome predicts the ability of T. sibiricus to metabolize agarose, which is confirmed by the observed growth on this substrate. Utilization of agarose is apparently enabled due to the function of an extracellular β-agarase (Tsib_0325). Agar, a cell wall constituent of many red algae, exists in nature as a mixture of unsubstituted and substituted agarose polymers and can constitute up to 70% of the algal cell wall. Agarase hydrolyzes agar and agarose, generating oligosaccharides. β-Agarase Tsib_0325 displays high similarity to the putative β-agarases of Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 and many different bacteria, including Victivallis vadensis and Pseudomonas putida. No homologs of Tsib_0325 or agarases are present in the genomes of any other archaea. A gene attached to the Tsib_0325 gene encodes a β-galactosidase (Tsib_0324) which would detach galactose residues from the oligosaccharides produced by β-agarase.

The lower-molecular-weight oligosaccharides resulting from the hydrolysis of polymers can be imported into the cell via binding protein-dependent ABC-type transport systems. The gene cluster Tsib_0320 to Tsib_0334 includes genes that encode an ABC transport system (Tsib_0329 to Tsib_0333) for β-glucosides. This system is homologous to the cellobiose/β-glucoside ABC transport system of P. furiosus (20).

The above data show that one particular region of the T. sibiricus genome (bp 308742 to 328657, corresponding to genes Tsib_0320 to Tsib_0334) carries a set of genes responsible for the utilization of cellulose, laminarin, agar, and other β-linked polysaccharides. This region contains genes for the extracellular cleavage of these substrates, transport of oligosaccharides into cells, and their subsequent intracellular cleavage to monomers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The closest homologs of all enzymes (except β-agarase) were found in Thermotoga and Pyrococcus species; however, this region is absent in T. kodakaraensis and T. onnurineus. In T. sibiricus, this gene island is embedded in a cluster of ribosomal protein genes with a one-to-one correlation to highly conserved corresponding genes in T. kodakaraensis and T. onnurineus (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). All of the above observations suggest that the “saccharolytic gene island” was horizontally transferred to the T. sibiricus genome from unknown thermophilic bacteria probably related to Thermotoga sp. The possible archaeal origin of this gene island also cannot be excluded, since extensive lateral gene transfer from archaea was suggested for T. maritima, in whose genome about 24% of the genes were found to bear the most similarity to archaeal genes (37). Homologs of some of the genes in the T. sibiricus saccharolytic gene island are also present in P. furiosus, but they are distributed in the genome and not located in a particular gene island.

Another supposed case of lateral transfer of saccharolytic genes in members of the order Thermococcales is the 16-kb maltose and trehalose degradation locus found in the P. furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis genomes (9). A similar gene island is present in the T. sibiricus genome (bp 340628 to 356664, corresponding to genes Tsib_0356 to Tsib_0369) with a one-to-one correlation to P. furiosus genes PF1737 to PF1751 (see Fig.S3 in the supplemental material). This gene cluster, which encodes a trehalose synthase (Tsib_0361), a glycogen-debranching enzyme (Tsib_0365), and a glycosidase (Tsib_0366), also harbors genes of two ABC transport systems for α-glucosides. The first (Tsib_0358 to Tsib_0360 and Tsib_0363) and the second (Tsib_0367 to Tsib_0369) transporters are related to the CUT1 (carbohydrate uptake) family Mal-I transporter of P. furiosus, which recognizes and transports maltose and trehalose, as well as to the Mal-II transporter of P. furiosus, which is specific for maltooligosaccharides (24). In addition, the second transporter contains a permease component (Tsib_0367) whose halves are highly homologous to the transmembrane ABC transporter permeases PF1748 and PF1749 that are upregulated in maltose- and starch-grown P. furiosus and have been suggested to function in maltose and starch assimilation (24). Tsib_0362 encodes TrmB, a maltose-specific transcriptional repressor of the Mal-I and Mal-II gene clusters in P. furiosus. This maltose and trehalose degradation gene island is present in the genomes of T. sibiricus, T. litoralis, and P. furiosus but is absent in closely related species (T. kodakaraensis, T. onnurineus, P. abyssi, and P. horikoshii), further supporting the hypothesis of its lateral transmission among members of the order Thermococcales.

Carbohydrate central metabolism.

The genome of T. sibiricus contains genes that encode enzymes of the modified Embden-Meyerhof (EM) pathway of glucose metabolism (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) of members of the order Thermococcales (50): ADP-dependent glucokinase, phosphoglucose isomerase (glucose-6-phosphate isomerase), ADP-dependent phosphofructokinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, triosephosphate isomerase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, nonphosphorylating glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate mutase, enolase, and pyruvate kinase. The pyruvate formed is further converted to acetyl-CoA and CO2 by pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase.

Generation of different sugars as precursors for anabolic pathways, especially during growth on proteins and for the synthesis of glucose polymers (glycogen) as storage material, proceeds in the gluconeogenic pathway, which shares many enzymes with the EM pathway, and is therefore partly reversible to the EM pathway (50). The T. sibiricus genome encodes the following enzymes to reverse the irreversible reactions of the EM pathway: phosphoenolpyruvate synthase, 3-phosphoglycerate kinase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Growth on hydrocarbons.

Attempts to grow T. sibiricus on medium with phenol and toluene as substrates did not result in growth, suggesting that it is unable to utilize aromatic components of crude oil. Correspondingly, in its genome, the genes that encode the key enzymes for anaerobic degradation of aromatics—benzoyl-CoA reductase, 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA reductase, benzylsuccinate synthase, and 6-oxocyclohex-1-ene-1-carbonyl-CoA hydrolase (16, 22, 41)—were absent.

In contrast to aromatic compounds, sequential transfers of T. sibiricus on medium with hexadecane as the substrate revealed reproducible growth, suggesting a potential of the organism to metabolize n-alkanes—the main constituents of petroleum and its refined products. Anaerobic bacteria with the capacity for alkane degradation have been isolated relatively recently, and the enzymes responsible have not been purified and characterized yet (14, 19). One mechanism of activation under anoxic conditions is carboxylation of the third carbon atom in an alkane (16, 34), which has been proposed for the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfococcus oleovorans Hxd3, which utilizes long-chain C12 to C20 alkanes. A more widespread activation mechanism is the addition of fumarate at the subterminal carbon atom, which yields a substituted succinate [(1-methylalkyl)succinate], using a glycyl radical as an initiator (34, 42). The gene that encodes the candidate enzyme (1-methylalkyl)succinate synthase (Mas) has been identified recently in alkane-utilizing denitrifying bacterial strain HxN1 (14). The tentative Mas protein is presumably a heterotrimer (MasCDE) that contains a motif (in MasD) characteristic of glycyl radical-bearing sites. The large subunit MasD is encoded by the T. sibiricus genome as Tsib_0631 and annotated as pyruvate:formate lyase. Close homologs of the subunits MasE and MasC are absent. MasG, the activase of MasCDE, is highly homologous to Tsib_0629, which is annotated as pyruvate-formate lyase-activating protein. It is impossible to conclude whether Tsib_0631 and Tsib_0629 encode the n-alkane-activating enzyme Mas and its activator or pyruvate:formate lyase and its activator. In T. kodakaraensis, similar open reading frames were described as pyruvate-formate lyase, and a role for this enzyme in pyruvate metabolism was proposed. Therefore, although T. sibiricus apparently grows on hexadecane, the lack of enzymatic data on anaerobic alkane activation does not allow the derivation of insight into the mechanism of hexadecane activation from the genome.

In alkane-utilizing bacteria, fatty acid chains formed from alkanes as acyl-CoA thioester can be further degraded via conventional β-oxidation with the production of acetyl-CoA and its subsequent mineralization to CO2 (41). However, a β-oxidation pathway is not present in T. sibiricus since homologs of the currently known genes of its key enzymes—fatty acid CoA ligase, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, and enoyl-CoA hydratase/isomerase—are not encoded in its genome.

The degradation of propionate (e.g., in “Aromatoleum aromaticum” EbN1) follows the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway, which is probably also involved in the degradation of odd-chained fatty acids, yielding propionyl-CoA as an intermediate (41). The key enzymes of the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway are propionyl-CoA carboxylase (PccAB and AccBC) and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (SbmAB). The genome of T. sibiricus encodes PccAB and AccBC (Tsib_1534 to Tsib_1536), as well as SbmAB (Tsib_0812). Therefore, both key enzymes of the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway are present. However, propionyl-CoA synthase (PrpE) is not encoded, suggesting that T. sibiricus is unable to activate and utilize propionate. Considering the stimulatory effect of hexadecane on growth and the absence of conventional β-oxidation, as well as propionate-activating propionyl-CoA synthase, an unknown pathway for the metabolism of this substrate could be involved in T. sibiricus.

Genome analysis predicts the growth of T. sibiricus on acetone, which was confirmed by growth experiments. In “A. aromaticum” EbN1, degradation of acetone and 2-butanone involves the functions of acetone carboxylase (AcxABC) and succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid-CoA ligase (KctAB) (22). In T. sibiricus, AcxA (Tsib_0819) and AcxB (Tsib_0820) are present. KctA and KctB are highly homologous to the N- and C-terminal halves of Tsib_0955, respectively. Degradation of acetone would result in acetyl-CoA, and degradation of 2-butanone would yield propionyl-CoA, which is further metabolized to pyruvate in the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway identified in T. sibiricus.

Growth on lipids.

The genome of T. sibiricus contains 15 genes that encode lipases/esterases. Four of these putative enzymes found in T. sibiricus contain signal peptides (Tsib_0218, Tsib_0981, Tsib_1042, and Tsib_1454), suggesting that they operate extracellularly. In accordance with the genomic data, T. sibiricus was found to grow on olive oil, whose major constituent is triolein. The lipolytic growth of T. sibiricus appears to be unique in the order Thermococcales and confirms the presence and functionality in this organism of extracellular true lipases that hydrolyze ester bonds in triacylglycerides of long-chain fatty acids. In addition, T. sibiricus was found to grow on glycerol but not on long-chain fatty acids. These findings agree with the absence of a β-oxidation pathway of fatty acid degradation. Therefore, growth on olive oil results from the utilization of glycerol liberated after hydrolysis of triglycerides by an extracellular lipase(s). Glycerol could be transported into the cell by Tsib_1774, which is partially related to glycerol uptake facilitator GlpF from Archaeoglobus fulgidus, and phosphorylated by glycerol kinase (Tsib_0768) and enter the modified EM pathway.

Conservation of energy.

T. sibiricus conserves energy by substrate level phosphorylation, as well as by oxidative phosphorylation (anaerobic respiration) linked to proton or sulfur reduction and proton translocation by membrane-bound complex I-related complexes MBH 1, MBH 2, and MBX (see below). Metabolism of sugars in the modified EM pathway and further oxidation of pyruvate result in the formation of two ATP molecules per molecule of glucose oxidized to acetate. Metabolism of proteins yields one molecule of ATP by substrate level phosphorylation per amino acid molecule oxidized.

The main mechanism of energy conservation in T. sibiricus appears to be proton translocation by three NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (complex I)-related systems: two membrane-bound proton-reducing H2-evolving hydrogenase complexes, MBH 1 and MBH 2 (energy-converting hydrogenases, Ech) (47), and one membrane-bound NADP+-reducing complex (MBX) eventually linked to the reduction of S° (48). The electron donor for these complexes is likely reduced ferredoxin, which is formed in ferredoxin-dependent reactions in the pathways of carbohydrate and protein oxidation. The function of H2-evolving hydrogenase complexes is supported by the observed evolution of H2 during the growth of T. sibiricus in the absence of S° as an electron acceptor (e.g., on peptone).

The genome of T. sibiricus contains two similar 14-gene operons that encode MBH 1 and MBH 2 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) and are related to the MBH operon of P. furiosus, which has the same gene order and encodes a six-subunit proton-translocating NiFe hydrogenase and multisubunit Na+/H+ transporters (17, 48). It should be noted that two MBH operons are present in D. kamchatkensis (43), whereas single MBH operons were found in P. furiosus and T. kodakaraensis. A 13-gene operon, MBX (Tsib_1905-Tsib_1917), is related to the MBX operon of P. furiosus and has the same gene order (48).

In the absence of S°, T. sibiricus presumably conserves energy by the function of MBH 1 and MBH 2 with reduced ferredoxin as an electron donor and protons as an electron acceptor. Thereby, protons are reduced to H2 and a transmembrane proton gradient is established.

The growth of T. sibiricus is inhibited by high H2 concentrations and stimulated by the presence of S° as an electron acceptor. In the presence of S°, T. sibiricus conserves energy by the function of MBX, as proposed for P. furiosus (48). MBX oxidizes reduced ferredoxin, translocates protons, and reduces NADP+. NADPH is reoxidized by NADPH:S° oxidoreductase (Tsib_0263), which transfers electrons to S° to produce H2S.

The proton gradient established by the functions of MBH 1, MBH 2, and MBX is used by ATP synthase for the synthesis of ATP. The genome of T. sibiricus encodes a single Na+-ATP synthase encoded by the genes atpHIKECFABD (Tsib_1798 to Tsib_1790). Assuming that the Ech hydrogenases and MBX complex translocate protons, the presence of Na+/H+ transporters in the gene clusters of MBH 1, MBH 2, and MBX can be explained by the requirement to convert the proton gradient into a Na+ ion gradient used for ATP synthesis by the Na+-ATP synthase of T. sibiricus. Note that relatively high salinity (optimal growth at 20 g liter−1 NaCl) is required for growth of T. sibiricus (32).

In addition to S°, some archaea can respire with sulfate, thiosulfate, or nitrate. However, genome analysis suggests that these compounds cannot be employed as electron acceptors by T. sibiricus because homologs of the currently known enzymes of the dissimilatory sulfate and thiosulfate reduction pathway (sulfate adenylyltransferase, adenylylsulfate reductase, sulfite reductase, and thiosulfate reductase), as well as the dissimilatory nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase, are not encoded.

Conclusions.

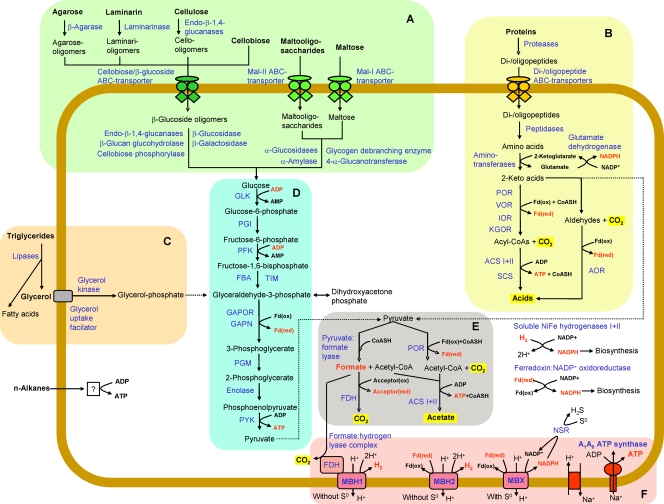

The metabolic pathways of substrate utilization and energy generation identified in the genome of T. sibiricus are presented in Fig. 2. The genomic sequence provided a basis for the discovery of many new physiological features of this organism, which was initially described as a specialized utilizer of proteinaceous substrates. In addition to the expected protein degradation and metabolism machinery, the genome encodes numerous extracellular and intracellular enzymes for carbohydrate degradation and sugar transport systems. In agreement with the genes identified, we have found T. sibiricus to be capable of growing on oligomeric and polymeric α-linked (maltose and dextran) and β-linked (cellobiose, cellulose, laminarin, and agarose) carbohydrates. The ability to grow on agarose was previously found in Desulfurococcus fermentans (40) but was never shown for representatives of the order Thermococcales or other hyperthermophilic Euryarchaeota. In the case of T. sibiricus, this capacity is supported by genome analysis, which revealed the presence of a β-agarase gene. The complete set of genes responsible for the hydrolysis of β-linked polysaccharides, their transport into the cell, and intracellular hydrolysis of oligomers to monosaccharides is located on a saccharolytic gene island, which is absent in the genomes of other members of the order Thermococcales and was probably acquired by T. sibiricus by lateral gene transfer. The second laterally acquired gene island contains genes for maltose and trehalose degradation.

FIG. 2.

Overview of catabolic pathways encoded by the T. sibiricus genome. Substrates utilized are in bold, enzymes and proteins identified on the genome are in blue, and energy-rich intermediate compounds are in red. Panels: A, utilization of carbohydrates; B, utilization of proteins; C, utilization of lipids; D, glycolysis (modified EM pathway); E, pyruvate degradation; F, formation of proton motive force coupled with ATP generation. Abbreviations: POR, pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase; VOR, 2-ketoisovalerate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase; IOR, indolepyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase; KGOR, 2-ketoglutarate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase; SCS, succinyl-CoA synthetase; ACS, acetyl-CoA synthetase; AOR, aldehyde:ferredoxin oxidoreductases; GLK, ADP-dependent glucokinase; PGI, phosphoglucose isomerase; GPI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; PFK, ADP-dependent phosphofructokinase; FBA, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase; TIM, triosephosphate isomerase; GAPOR, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase; GAPN, nonphosphorylating glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PGM, phosphoglycerate mutase; PYK, pyruvate kinase; PGK, 3-phosphoglycerate kinase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; FBP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase; FDH, formate dehydrogenase; Fd(ox), oxidized ferredoxin; Fd(red), reduced ferredoxin; NSR, NADPH:S° oxidoreductase; CoASH, coenzyme A.

Moreover, T. sibiricus probably possesses a new mechanism of n-alkane degradation, since its growth is stimulated by hexadecane and no enzymes of currently known pathways are encoded. Not reported so far for hyperthermophilic archaea is the lipolytic growth of T. sibiricus on triacylglycerides. This growth is apparently enabled by the function of an extracellular true lipase(s) encoded by the genome.

The new physiological features of T. sibiricus are consistent with the proposal of the indigenous origin of the organism in the never flooded oil-bearing Jurassic horizon of the Samotlor oil reservoir, where it was found (32) and explain its survival over geologic time, as well as its proliferation in this habitat. Indeed, in addition to amino acids present in oil reservoirs at limiting concentrations (53), its growth could be supported by cellulose, agarose, laminarin, and triglycerides from oceanic sediments, as well as alkanes from crude oil. Considering that agarose and laminarin are components of algae, the substrate spectrum of T. sibiricus and the enzymes it encodes indicate the ability to metabolize buried organic matter from the original oceanic sediment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexander Lebedinsky for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Federal Agency for Science and Innovations of Russia (contract 02.512.11.2201). The work of M.L.M. and E.A.B.-O. on the analysis of the growth characteristics of T. sibiricus was supported by the Program Molecular and Cellular Biology of RAS.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 May 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. W., J. F. Holden, A. L. Menon, G. J. Schut, A. M. Grunden, C. Hou, A. M. Hutchins, F. E. Jenney, Jr., C. Kim, K. Ma, G. Pan, R. Roy, R. Sapra, S. V. Story, and M. F. Verhagen. 2001. Key role for sulfur in peptide metabolism and in regulation of three hydrogenases in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 183:716-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrangou, R., C. Fremaux, H. Deveau, M. Richards, P. Boyaval, S. Moineau, D. A. Romero, and P. Horvath. 2007. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315:1709-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, M. W., L. E. Driskill, W. Callen, M. A. Snead, E. J. Mathur, and R. M. Kelly. 1999. An endoglucanase, EglA, from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus hydrolyzes β-1,4 bonds in mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucans and cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 181:284-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertoldo, C., and G. Antranikian. 2006. The order Thermococcales, p. 69-81. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K.-H. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd, ed., vol. 3. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, L., K. Brügger, M. Skovgaard, P. Redder, Q. She, E. Torarinsson, B. Greve, M. Awayez, A. Zibat, H.-P. Klenk, and R. A. Garrett. 2005. The genome of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, a model organism of the Crenarchaeota. J. Bacteriol. 187:4992-4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chhabra, S. R., K. R. Shockley, D. E. Ward, and R. M. Kelly. 2002. Regulation of endo-acting glycosyl hydrolases in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima grown on glucan- and mannan-based polysaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:545-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen, G. N., V. Barbe, D. Flament, M. Galperin, R. Heilig, O. Lecompte, O. Poch, D. Prieur, J. Quérellou, R. Ripp, J. C. Thierry, J. Van der Oost, J. Weissenbach, Y. Zivanovic, and P. Forterre. 2003. An integrated analysis of the genome of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus abyssi. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1495-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delcher, A. L., D. Harmon, S. Kasif, O. White, and S. L. Salzberg. 1999. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:4636-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiRuggiero, J., D. Dunn, D. L. Maeder, R. Holley-Shanks, J. Chatard, R. Horlacher, F. T. Robb, W. Boos, and R. B. Weiss. 2000. Evidence of recent lateral gene transfer among hyperthermophilic archaea. Mol. Microbiol. 38:684-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driskill, L. E., M. W. Bauer, and R. M. Kelly. 1999. Synergistic interactions among β-laminarinase, β-1,4-glucanase, and β-glucosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus during hydrolysis of β-1,4-, β-1,3-, and mixed-linked polysaccharides. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 66:51-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukui, T., H. Atomi, T. Kanai, R. Matsumi, S. Fujiwara, and T. Imanaka. 2005. Complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 and comparison with Pyrococcus genomes. Genome Res. 15:352-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths-Jones, S., A. Bateman, M. Marshall, A. Khanna, and S. Eddy. 2003. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:439-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grissa, I., G. Vergnaud, and C. Pourcel. 2007. CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 35(Web Server Issue):W52-W57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundmann, O., A. Behrends, R. Rabus, J. Amann, T. Halder, J. Heider, and F. Widdel. 2008. Genes encoding the candidate enzyme for anaerobic activation of n-alkanes in the denitrifying bacterium, strain HxN1. Environ. Microbiol. 10:376-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gueguen, Y., W. G. Voorhorst, J. van der Oost, and W. M. de Vos. 1997. Molecular and biochemical characterization of an endo-β-1,3-glucanase of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31258-31264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heider, J. 2007. Adding handles to unhandy substrates: anaerobic hydrocarbon activation mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11:188-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenney, F. E., Jr., and M. W. Adams. 2008. Hydrogenases of the model hyperthermophiles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1125:252-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawarabayasi, Y., M. Sawada, H. Horikawa, Y. Haikawa, Y. Hino, S. Yamamoto, M. Sekine, S. Baba, H. Kosugi, A. Hosoyama, Y. Nagai, M. Sakai, K. Ogura, R. Otsuka, H. Nakazawa, M. Takamiya, Y. Ohfuku, T. Funahashi, T. Tanaka, Y. Kudoh, J. Yamazaki, N. Kushida, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, and H. Kikuchi. 1998. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyper-thermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. DNA Res. 5:55-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kniemeyer, O., F. Musat, S. M. Sievert, K. Knittel, H. Wilkes, M. Blumenberg, W. Michaelis, A. Classen, C. Bolm, S. B. Joye, and F. Widdel. 2007. Anaerobic oxidation of short-chain hydrocarbons by marine sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nature 449:898-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koning, S. M., M. G. Elferink, W. N. Konings, and A. J. Driessen. 2001. Cellobiose uptake in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus is mediated by an inducible, high-affinity ABC transporter. J. Bacteriol. 183:4979-4984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koski, L. B., M. W. Gray, B. F. Langi, and G. Burger. 2005. AutoFACT: an automatic functional annotation and classification tool. BMC Bioinformatics 6:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuntze, K., Y. Shinoda, H. Moutakki, M. J. McInerney, C. Vogt, H. H. Richnow, and M. Boll. 2008. 6-Oxocyclohex-1-ene-1-carbonyl-coenzyme A hydrolases from obligately anaerobic bacteria: characterization and identification of its gene as a functional marker for aromatic compounds degrading anaerobes. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1547-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, H. S., S. G. Kang, S. S. Bae, J. K. Lim, Y. Cho, Y. J. Kim, J. H. Jeon, S.-S. Cha, K. K. Kwon, H.-T. Kim, C.-J. Park, H.-W. Lee, S. I. Kim, J. Chun, R. R. Colwell, S.-J. Kim, and J.-H. Lee. 2008. The complete genome sequence of Thermococcus onnurineus NA1 reveals a mixed heterotrophic and carboxydotrophic metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 190:7491-7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, H. S., K. R. Shockley, G. J. Schut, S. B. Conners, C. I. Montero, M. R. Johnson, C. J. Chou, S. L. Bridger, N. Wigner, S. D. Brehm, F. E. Jenney, Jr., D. A. Comfort, R. M. Kelly, and M. W. Adams. 2006. Transcriptional and biochemical analysis of starch metabolism in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 188:2115-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liebl, W., P. Ruile, K. Bronnenmeier, K. Riedel, F. Lottspeich, and I. Greif. 1996. Analysis of a Thermotoga maritima DNA fragment encoding two similar thermostable cellulases, CelA and CelB, and characterization of the recombinant enzymes. Microbiology 142:2533-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lillestøl, R. K., P. Redder, R. A. Garrett, and K. Brügger. 2006. A putative viral defence mechanism in archaeal cells. Archaea 2:59-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowe, T., and S. R. Eddy. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma, K., A. Hutchins, S. J. Sung, and M. W. Adams. 1997. Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus, functions as a CoA-dependent pyruvate decarboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9608-9613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mai, X., and M. W. Adams. 1996. Purification and characterization of two reversible and ADP-dependent acetyl coenzyme A synthetases from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 178:5897-5903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marmur, J. 1961. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J. Mol. Biol. 3:208-218. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsunaga, F., P. Forterre, Y. Ishino, and H. Myllykallio. 2001. Interactions of archaeal Cdc6/Orc1 and minichromosome maintenance proteins with the replication origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:11152-11157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miroshnichenko, M. L., H. Hippe, E. Stackebrandt, N. A. Kostrikina, N. A. Chernyh, C. Jeanthon, T. N. Nazina, S. S. Belyaev, and E. A. Bonch-Osmolovskaya. 2001. Isolation and characterization of Thermococcus sibiricus sp. nov. from a Western Siberia high-temperature oil reservoir. Extremophiles 5:85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mojica, F. J., C. Diez-Villasenor, J. Garcia-Martinez, and E. Soria. 2005. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J. Mol. Evol. 60:174-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muyzer, G., and G. M. van der Kraan. 2008. Bacteria from hydrocarbon seep areas growing on short-chain alkanes. Trends Microbiol. 16:138-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myllykallio, H., P. Lopez, P. Lopez-Garcia, R. Heilig, W. Saurin, Y. Zivanovic, H. Philippe, and P. Forterre. 2000. Bacterial mode of replication with eukaryotic-like machinery in a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Science 288:2212-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nazina, T. N., N. M. Shestakova, A. A. Grigoryan, E. M. Mikhailova, T. P. Tourova, A. B. Poltaraus, Q. Feng, F. Ni, and S. S. Belyaev. 2006. Phylogenetic diversity and activity of anaerobic microorganisms of high-temperature horizons of the Dagang oilfield (China). Mikrobiologiya 75:70-81. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson, K. E., R. A. Clayton, S. R. Gill, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, W. C. Nelson, K. A. Ketchum, L. McDonald, T. R. Utterback, J. A. Malek, K. D. Linher, M. M. Garrett, A. M. Stewart, M. D. Cotton, M. S. Pratt, C. A. Phillips, D. Richardson, J. Heidelberg, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, J. A. Eisen, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 1999. Evidence for lateral gene transfer between archaea and bacteria from genome sequence of Thermotoga maritima. Nature 399:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orphan, V. J., L. T. Taylor, D. Hafenbradl, and E. F. Delong. 2000. Culture-dependent and culture-independent characterization of microbial assemblages associated with high-temperature petroleum reservoirs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:700-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng, X., I. Holz, W. Zillig, R. A. Garrett, and Q. She. 2000. Evolution of the family of pRN plasmids and their integrase-mediated insertion into the chromosome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Mol. Biol. 303:449-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perevalova, A. A., V. A. Svetlichny, I. V. Kublanov, N. A. Chernyh, N. A. Kostrikina, T. P. Tourova, B. B. Kuznetsov, and E. A. Bonch-Osmolovskaya. 2005. Desulfurococcus fermentans sp. nov., a novel hyperthermophilic archaeon from a Kamchatka hot spring, and emended description of the genus Desulfurococcus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:995-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabus, R., M. Kube, J. Heider, A. Beck, K. Heitmann, F. Widdel, and R. Reinhardt. 2005. The genome sequence of an anaerobic aromatic-degrading denitrifying bacterium, strain EbN1. Arch. Microbiol. 183:27-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabus, R., H. Wilkes, A. Behrends, A. Armstroff, T. Fischer, A. J. Pierik, and F. Widdel. 2001. Anaerobic initial reaction of n-alkanes in a denitrifying bacterium: evidence for (1-methylpentyl)succinate as initial product and for involvement of an organic radical in n-hexane metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 183:1707-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravin, N. V., A. V. Mardanov, A. V. Beletsky, I. V. Kublanov, T. V. Kolganova, A. V. Lebedinsky, N. A. Chernyh, E. A. Bonch-Osmolovskaya, and K. G. Skryabin. 2009. Complete genome sequence of the anaerobic, peptide-fermenting hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Desulfurococcus kamchatkensis. J. Bacteriol. 191:2371-2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robb, F. T., D. L. Maeder, J. R. Brown, J. DiRuggiero, M. D. Stump, R. K. Yeh, R. B. Weiss, and D. M. Dunn. 2001. Genomic sequence of hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus furiosus: implications for physiology and enzymology. Methods Enzymol. 330:134-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson, N. P., I. Dionne, M. Lundgren, V. L. Marsh, R. Bernander, and S. D. Bell. 2004. Identification of two origins of replication in the single chromosome of the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Cell 116:25-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson, N. P., and S. D. Bell. 2007. Extrachromosomal element capture and the evolution of multiple replication origins in archaeal chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:5806-5811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sapra, R., K. Bagramyan, and M. W. Adams. 2003. A simple energy-conserving system: proton reduction coupled to proton translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7545-7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schut, G. J., S. L. Bridger, and M. W. Adams. 2007. Insights into the metabolism of elemental sulfur by the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: characterization of a coenzyme A-dependent NAD(P)H sulfur oxidoreductase. J. Bacteriol. 189:4431-4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shikata, K., T. Fukui, H. Atomi, and T. Imanaka. 2007. A novel ADP-forming succinyl-CoA synthetase in Thermococcus kodakaraensis structurally related to the archaeal nucleoside diphosphate-forming acetyl-CoA synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 282:26963-26970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siebers, B., and P. Schönheit. 2005. Unusual pathways and enzymes of central carbohydrate metabolism in Archaea. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:695-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sokolova, T. G., C. Jeanthon, N. A. Kostrikina, N. A. Chernyh, A. V. Lebedinsky, E. Stackebrandt, and E. A. Bonch-Osmolovskaya. 2004. The first evidence of anaerobic CO oxidation coupled with H2 production by a hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Extremophiles 8:317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svetlitchnyi, V., C. Peschel, G. Acker, and O. Meyer. 2001. Two membrane-associated NiFeS-carbon monoxide dehydrogenases from the anaerobic carbon-monoxide-utilizing eubacterium Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans. J. Bacteriol. 183:5134-5144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahata, Y., T. Hoaki, and T. Maruyama. 2001. Starvation survivability of Thermococcus strains isolated from Japanese oil reservoirs. Arch. Microbiol. 176:264-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahata, Y., M. Nishijima, T. Hoaki, and T. Maruyama. 2000. Distribution and physiological characteristics of hyperthermophiles in the Kubiki oil reservoir in Niigata, Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:73-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voorhorst, W. G., R. I. Eggen, E. J. Luesink, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Characterization of the celB gene coding for β-glucosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus and its expression and site-directed mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:7105-7111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yernool, D. A., J. K. McCarthy, D. E. Eveleigh, and J. D. Bok. 2000. Cloning and characterization of the glucooligosaccharide catabolic pathway β-glucan glucohydrolase and cellobiose phosphorylase in the marine hyperthermophile Thermotoga neapolitana. J. Bacteriol. 182:5172-5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang, R., and C. Zhang. 2005. Identification and replication origins in archaeal genomes based on the Z-curve method. Archaea 1:335-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zverlov, V., S. Mahr, K. Riedel, and K. Bronnenmeier. 1998. Properties and gene structure of a bifunctional cellulolytic enzyme (CelA) from the extreme thermophile ‘Anaerocellum thermophilum’ with separate glycosyl hydrolase family 9 and 48 catalytic domains. Microbiology 144:457-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.