Abstract

Despite increasing rates of HIV infection among heterosexual women in Peru, married women remain virtually invisible as a group at risk of HIV or requiring treatment. This study analyzed the intersections of HIV with machismo and marianismo, the dominant discourses in Latin America that prescribe gender roles for men and women. Data sources include recent literature on machismo and marianismo and interviews conducted with 14 HIV-positive women in Lima, Peru. Findings indicate how the stigma associated with HIV constructs a discourse that restricts the identities of HIV-positive women to those of ‘fallen women’ whether or not they adhere to social codes that shape and inform their identities as faithful wives and devoted mothers. Lack of public discourse concerning HIV-positive marianas silences women as wives and disenfranchises them as mothers, leaving them little room to negotiate identities that allow them to maintain their respected social positions. Efforts must be aimed at expanding the discourse of acceptable gender roles and behaviour for both men and women within the context of machismo and marianismo so that there can be better recognition of all persons at risk of, and living with, HIV infection.

Keywords: Gender roles, marianismo, Peru, HIV-positive women, discourse analysis

Nearly half of the approximately 40 million people living with HIV worldwide are women (WHO 2006). In Peru, published reports of available data suggest that HIV incidence among women is rising rapidly, as would be expected in a country where 97% of HIV transmission occurs via sexual contact. Indeed, between 1990 and 2000 the ratio of infection between men and women in Peru dropped from 15:1 to 2.7:1 (Ministerio de Salud 2005), indicating the need to respond to women's increasing vulnerability. Currently, Peruvian women account for one third of the known 82,000 cases of HIV infection in the country (Ministerio de Salud 2005); those who are in the reproductive years (between the ages of 20 to 39 years) being at highest risk (USAID 2005). Estimates of HIV infection in Peru are undoubtedly low: the U.S. Agency for International Development estimates the under-reporting of HIV in Peru to be as high as 35% (USAID 2005).

For Peruvian women, as for women in most of the world, heterosexual transmission is the primary risk factor for contracting HIV (US AID 2005; CDC 2007). Many HIV-positive women have had few lifetime sexual partners and few personal sexual risk factors (Johnson et al. 2003; Marin 2003); however, having few sex partners does not obviate the risk of acquiring HIV (Marin et al. 1993; Marks et al. 1998). Women are often unaware of their primary risk factor: their male partner's sexual behaviour, often resulting from extramarital affairs (Alarcon et al. 2003; Johnson et al. 2003). The majority of HIV infections in Peru occur among men: US AID (2005) reported that of those infected, 40% are heterosexual and 42% are men who regularly or occasionally have sex with men (MSM). The similar proportions of HIV among heterosexual men and MSM highlight the increasing risk of HIV infection for heterosexual women. Despite these findings, Peru's HIV prevention and treatment efforts continue mainly to target men. Married women remain virtually invisible as a group at risk of HIV infection or requiring treatment. The lack of attention given to married HIV-positive women may derive from the gender bias, strict gender roles, and women's subordination within patriarchal structures in Latino cultures.

Gender is a basic organizing principle in society and is one of the most important human divisions (Baca Zinn 1995; Baker-Miller 1986). Around the globe, there are variations in gender norms, cultural expectations, and the extent of gender bias in social systems and public institutions, yet one consistent theme across cultures is the different gender roles for men and women (Amaro and Raj 2000; Jackson 2007; Rao Gupta 2000). Women's risk for HIV infection is embedded within a gender-based context (Amaro and Raj 2000; Amaro et al. 2001) in which she is situated in a system of social inequalities and differential access to power from birth (Baker-Miller 1986; Few 1997; Jackson 2007).

In Latin cultures, machismo and marianismo are the dominant cultural values that prescribe the social roles and sexual behaviours of men and women. Marianismo constructs social roles in which women are lauded for being faithful wives and devoted mothers. Women are recognized as good marianas when they remain sexually naïve and passive in their relationships with their male partners and do not question their partners when they suspect infidelities. These norms of behavior increase women's susceptibility to HIV infection, yet the link between marianismo and HIV risk has not been fully explored.

In this study, we used discourse analysis to examine how discourses of HIV infection and marianismo interact to disrupt the identities and opportunities for married women who were once recognized as marianas and whose status rapidly changed with a diagnosis of HIV. We approached the analysis from a social constructionist view in which we look at how master discourses shape what language is used (or not used) to describe and accomplish personal, social, and political plans and actions (Starks and Trinidad 2007). Social constructionists argue that we create and understand social and personal identities, roles, and meaning through discursive interaction (Phillips and Hardy 2002; Savage 2000). Language serves as the primary means through which individuals enact their identities (Gee 2005; Lyons 1971). Careful analysis of language can shed light on the creation and maintenance of social norms, the construction of personal and group identities, and the negotiation of social and political interaction. Data for this study are drawn from literature on the gender roles and expectations established by machismo and marianismo in Latin America and transcripts from 14 semi-structured interviews conducted with HIV-positive women in Lima, Peru.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the consequences for women who are trying to forge a new identity as HIV-positive marianas in the absence of a recognizable place in the discourse of marianismo, and to discuss the implications of this for HIV prevention and treatment efforts designed for married Latin women. We argue that although HIV infection occurs across a continuum of gender identities (for both men and women), stereotypes and stigmatizing discourses associate HIV infection with marginalized and socially deviant behaviours and identities, leaving women who do not engage in these behaviours no place to create or maintain a socially sanctioned identity with its incumbent social power and rewards.

Our analysis begins with a discussion of the history and situated meanings of machismo and marianismo. We then describe how the major themes of marianismo relate to the interview narratives about HIV infection and how this challenges the ability of these women to sustain their traditional role identities as good wives and mothers (and thus maintain their social positions and receive social support). We discuss how gender expectations created by marianismo render married women invisible to HIV prevention and treatment efforts, in spite of their heightened risk for infection.

Machismo and Marianismo: Gender Role Ideals

We use the term machismo to refer to the gendered roles of Latino men, while recognizing that these macho or masculine behaviours are not unique to Latino men (Gilmore 1991). Nonetheless, machismo is a dominant discourse for communicating traditional gender roles and masculine ideals in Latino cultures. It sets the standards for the roles and characteristics ascribed to men: as providers, protectors, strong, virile, and courageous. They also are dominant, assertive, and expect female submissiveness and passivity (Mirande 1988). Macho men enacting these roles may believe that they have social and sexual freedoms denied to women. They may consider extramarital affairs a way to demonstrate their machismo, as proof of their virility (Paternostro 1998). Machismo plays a significant role in HIV transmission, because of the way it shapes and sanctions the range of recognizable and acceptable expressions of male sexuality.

Machismo, in the context of the homophobic climate found in many Latin American countries, also acts to silence non-heterosexual identities and practices. The pejorative term, maricón, is used to denigrate men who identify as or who are perceived to be gay or to belittle the masculinity of effeminate heterosexual men (Carillo 2002). The term maricón derives from Mary or Maria, the Catholic name for the iconic mother of God. Unlike maricónes, macho men would never acknowledge engaging in behaviours such as receptive anal intercourse that suggest a sexual passivity mainly associated with women (Paternostro 1998). Men can maintain their identity as macho even when they have sex with other men, as long as they enact assertive and dominant positions in these encounters. In this regard, macho men have a wide range of behaviours that are accepted by society; they can be family men or even married men who have sex with men and still be recognized as machos.

Given the harsh negative stereotypes associated with being labeled a maricón, many men who engage in sex with other men do not identify as gay (Caceres 2002; Johnson et al. 2003) and a significant number of men who have sex with men also have sex with women (Tabet et al. 2002). Indeed, in one study of 4,000 Peruvian men who have sex with men, nearly half (47%) reported having sex with a woman within the prior year, frequently without a condom; many of these men reported being married (Tabet et al. 2002). Therefore, HIV prevention interventions directed at gay-identified men often fail to reach the intended target population. In addition, this silencing of certain sexual behaviours not only increases HIV risk among men who have sex with other men, but also puts their female partners at risk (Caceres 2002; Johnson et al. 2003; Ministerio de Salud 2005).

Machismo grants men sexual freedom to engage in behaviours that women are forced to accept; at the same time, homophobia in Latin America blinds women to men's sexual relations with other men or to the open acknowledgement of such arrangements even when they are apparent (Paternostro 1998). This situation leads women to believe infidelities on the part of their male partners involve only women. The notion of machismo and resulting beliefs about male sexuality partly explain why Latin women perceive themselves at little or no risk for HIV infection. Marianismo further explains this perception.

Marianismo is regarded as the female counterpart to machismo and refers to female gender roles. The term marianismo originates from the Virgin Mary (Maria or Madonna) and refers to an exaggerated and idealized persona of women and girls in Latino culture. The term marianismo can be traced to the Roman Catholic Church referring to the religious practice in which followers idolize the icon of the Virgin Mary (Stevens 1973). It connotes the ideal of true femininity to which women are expected to aspire: being modest, virtuous, and sexually naïve and abstinent until marriage (Arredondo 2002; Peragallo 1996). Marianismo and a traditional lack of economic alternatives for women maintain women in the home as homemakers and define their identities primarily as faithful wives and devoted mothers. Marianismo also is associated with a number of positive aspects, in which a woman's self-esteem is manifested in her ability to be a giving and generous mother. Her self-esteem is further manifested through her ability to uphold and promote cultural ideals such as familismo (familism), personalismo (personalism), respeto (respect), and sympatia (ability to create friendly and smooth relationships that avoid conflict) (Comas-Diaz 1989; Falicov 1998).

Women who embody marianismo fulfill family obligations by maintaining strong familial bonds and familial harmony through the avoidance of conflict (Comas-Diaz 1989). They achieve this by fulfilling the social expectation of renouncing their personal interests in favour of those of their husbands and children. As wives, women are expected to be sexually inexperienced, monogamous, loyal, subordinate to their husbands, and unaware or unsuspecting of their partner's extramarital sexual behaviours. They also have little say over what their husbands do; most become infected with HIV by the man who has been their sole sex partner for their entire lives (Arguelles and Rivero 1988). In a traditionally machista society, women do not talk with men about sex as this may be viewed as distasteful or suggestive of sexual promiscuity (Marín and Gómez 1994; Moreno 2007). Women who appear to have knowledge about sex or openly express their sexuality may be derogatorily labeled as putas (whores) as a way to silence them.

Marianismo and machismo work together to ensure that women remain naïve about sex, sexually transmitted diseases, and negotiating safe sexual practices. Paradoxically, enacting the role of the good mariana may place married women at higher risk for HIV infection than other women such as sex workers (Paternostro 1998; Miller et al. 2004). Because they have abandoned their primary identity as a mariana and resist the discourse of that role, sex workers are able to enact another identity that allows them a degree of sexual freedom, the power to negotiate sex with men, and ultimately protect themselves against HIV infection. To illustrate this reality, in Peru, HIV infection among female sex workers remains low and condom use with clients remains high (Miller et al. 2004).

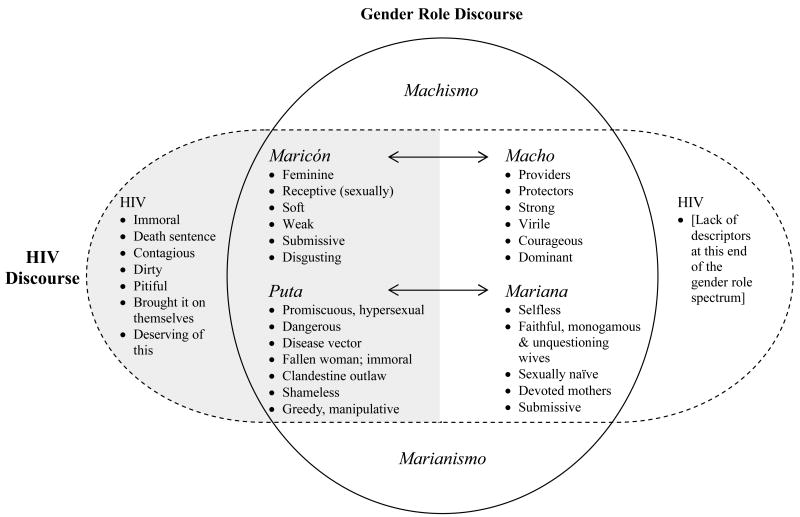

For men and women alike, enacting (or being perceived as enacting) the roles of macho and mariana can garner respect and social reward. In this regard, gender identities are constructed along a continuum (Figure 1) where enacting (or being accused of enacting) the gender roles of maricón or puta (on extreme ends of the spectrum for men and women, respectively) are socially sanctioned to invite disrespect and its associated stigma and discrimination.

Figure 1.

Overlap of discourses of Machismo and Marianismo and HIV

There exists a tendency to associate heterosexuality with masculinity and homosexuality with femininity and passivity. However, recent studies have demonstrated that behaviours identified as masculine or feminine are independent of sexual orientation (see Guttman 2003). People often have multiple identities and can take on male or female gender roles at various points in time and in different venues, private and public. However, the typical public identities are those that are likely to maintain or increase access to socially desirable goods. Because of this, many individuals perceive no alternative but to hide the identities that will result in stigma or social ostracism. Thus, it is easier for them to maintain their public identities at the desirable and respectable ‘right’ end of the spectrum.

Figure 1 also depicts the overlap of discourses between gender roles (vertical oval) and HIV (horizontal oval). The gender role discourse is shown by the continuum of idealized gender identities that are recognized under machismo and marianismo. The HIV discourse represented here shows that while HIV affects persons across the entire gender identity spectrum, it is primarily associated with the disenfranchised gender identities on the left side of the figure. The descriptors used in the figure were compiled from the existing literature (Lawless et al. 1996; Paternostro 1998; Nencel 2001); there was a notable absence of HIV descriptors associated with the gender roles for machos and marianas.

HIV infection transforms the social identities of women from that of an idealized mariana to that of a promiscuous woman, at worst a puta. Regardless of a woman's purity or her actual behavior, HIV imposes an identity at the opposite end of the social spectrum from where she wants to believe herself to be. In general, this association preserves the social standing of machos and marianas, but for marianas who become infected with HIV, this discursive vacuum leaves them little place to reconcile their reality.

Research Participants and Interviews

For the present study, we recruited 14 HIV-positive women who resided in and around Lima, Peru who were participating in a larger cross-sectional study at the Asociación Civil Impacta de Salud y Educación (Impacta), a sexually transmitted disease research clinic located in Lima. Eligibility criteria for the cross-sectional study were being female and HIV-positive, not known to be pregnant at the time of enrollment, and age 18 years or older. A purposive sample of women was chosen from the cross-sectional study based on age (mean = 33 years, range= 20 – 47 years); economic situation; relationship status (e.g., married, single, cohabitating); and stage of HIV disease and treatment (e.g., women on or off highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART]) and invited to participate in a face-to-face interview by a female clinic counsellor. All women identified as heterosexual and all had at least one child (range 1-5). One investigator trained in interview methodology discussed the study with eligible participants and enrolled women after obtaining written informed consent. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Review Boards at the University of Washington and Impacta.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted at the clinic in Spanish by the first author, a bilingual, bicultural Mexican American woman. The interviews were audio-recorded and ranged from 30 to 120 minutes in duration. They were guided by a set of questions about participants' social roles and support, the process of acquiring HIV, their perceptions and experiences of HIV-related stigma, and disclosure of HIV status. The interview guide, originally in English, was translated and back-translated to ensure linguistic and cultural equivalency (Marín and Marín 1991). Participants were given S/.15 soles (approximately US $5) for travel expenses and their time.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim in Spanish and coded for gender roles, stigma, and social support. The transcripts in their entirety and the narratives assigned to these codes were reviewed for evidence of how women enacted their roles and identities after HIV infection. Quotes were selected that demonstrate the main themes for this analysis. The analyses were carried out in Spanish; the selected quotes were translated for this paper. We assigned pseudonyms to the respondents to preserve anonymity.

In our analysis of the 14 interviews, we found clear examples of how the overlapping discourses of HIV and marianismo shaped the identity options for these women. We present an overview of the four main themes that describe the relationship between these two discourses: (1) the initial fall from grace (that occurs with the HIV diagnosis); (2) the silenced wife; (3) the disenfranchised mother; and (4) the effort to reclaim social rights and position. We include examples from the transcripts to illustrate how these themes were experienced by the women.

The Initial Fall from Grace

For women in Peru, HIV infection implies a failure to have upheld traditional gender roles (Lawless et al. 1996), the prevailing belief being that good marianas do not associate with persons with HIV because infection is equated with promiscuity or homosexuality. Since good marianas are not promiscuous, there is no reason for them to learn much about this disease, how to prevent it, or to be tested. Accordingly, most of the participants interviewed for this study did not know anyone with HIV and had little knowledge of the disease prior to learning their status. Thus, a typical first reaction to the diagnosis of HIV was of surprise and disbelief.

I didn't know anything [about HIV], I was not aware of anything, if at some point I ever noticed this disease I didn't know what it was, I knew what Hepatitis was, but not AIDS. When they told me [about my status] I went into counseling, it is as if they suddenly opened my eyes. I honestly thought that this disease had a cure, but they tell me that it doesn't. (Lucia, 31 year-old, laundry worker)

‘They told me that AIDS was something only for maricones [gay men]… then, I would say ‘but how could this have happened to me?’ How did this happen?’ (Ana, 32 year-old, homemaker)

Ana was not alone in her ignorance of HIV disease or the fact that she could be infected by her husband. Most participants learned about HIV after their diagnosis, which typically occurred during pregnancy or when their partner was dying or had died of AIDS. Many of the women shared the common belief that HIV occurred amongst marginalized individuals, not women like themselves. Ignorance of HIV highlights the fact that woman were adhering to the prescribed gender roles by not knowing too much about sex or knowledge of things (e.g., diseases) that happen to “bad women.”

HIV infection among married women represented a fall from grace in the eyes of those around them. Regardless of their behaviour, it was frequently assumed that married women were the source of infection for their husbands and children. One of the participants described how she defended herself against being treated like one of ‘those tainted women’. She resided in the wealthiest area of Lima, had a college education, and had had a successful career as a model. As a side effect of being on HAART, she had developed severe lipoatrophy of her face and could no longer disguise her changed appearance. She spoke of how HIV had radically changed her work life and how others feel free to invade her privacy about her sex life.

There was a time when I would work at all the social events at the L Club. They always contracted me to work and I would be in charge of hosting all the major [social] events. I had everything, the clothes that I wanted, the hairstyles, they gave me everything. Then everything changed. (Marisol, 44 year-old, arts saleswoman)

She was isolated at work and stopped getting contracts, until eventually she was unemployable. This woman of high society fell from grace on the basis of her HIV status. At the end of the study interview, Marisol mentioned that what she appreciated most about the conversation was that she was not asked any detailed questions about her sexual behaviour. She stated,

One thing that I have enjoyed most about this conversation is that you have respected my personal sex life …this is one thing that I don't like, and this is the first time that this has happened. …[T]here is a lot of obsession regarding that topic [sexual behaviour] and I don't like it one bit because regardless if someone has HIV one has secrets or simply it is your own private life and you don't talk about your private [sex] life.

One consequence of her HIV infection was that people who would never otherwise have asked her such intimate and personal questions now felt at liberty to inquire about her sexual practices.

The Silenced Wife

For many women, this fall from grace brought certain penalties, such as the loss of social benefits that were accorded to highly regarded wives and mothers. These losses were most acutely felt within families and especially within households. Similar to other Latin American countries, in Peru it is customary for married women to live with their in-laws after marriage and in widowhood, and therefore rely on their in-laws through their husband's illness and death. Women cannot afford to tarnish their reputation in the family by disclosing their HIV status or openly blame their husband for their HIV-infection, as they risk losing social and financial support if they are rejected or abandoned. For example, one woman spoke of the need to lie about the cause of her husband's death, to preserve both of their reputations in the community:

My friend approached me and told me that people were saying that my husband died of that [AIDS]. “Who said that?” I asked her. That is what people are saying [she replied]. I try to deny it, people are like that, I tell them that he died of a heart attack, I tell them that he was ill, that he had tuberculosis, convulsions, so therefore he died of cardiac arrest. (Rosario, 36 year-old, homemaker)

In Latin culture, what others say about you is held in high regard; often times when something happens to someone or in a family, a common reaction is to wonder “que dira la gente” (what will people say?). Here, Rosario is preserving her husband's reputation and by default her own. She offers a “valid” explanation so that others will not think or talk badly about her or her husband. By resisting acknowledgement of the disease, she also assures herself and others that her identity remains unchanged. Women living with HIV cannot enact the identity of being a good mariana because there is no language for this mixed identity, thereby causing women to feel silenced about their disease and fearful of others knowing their status (Lawless et al. 1996).

Another aspect of marianismo endorses behavior in which women abnegate their own needs to serve the interests of their husbands and children. This, in combination with fatalism (fatalismo), a term commonly attributed to the belief system in which events occur based on fate or predetermination, was evident in some of the women's stories. Similar to the fate of the Virgin Mary who was chosen to be the mother of God, so too must women quietly accept their fate. Previous studies have found that Latino men and women endorse having little control over avoiding HIV (Marin et al. 1993; Diaz and Ayala, 1999). Abnegation and fatalism were reflected in the women's narratives by the absence of any mention of being angry or mad at their husbands for infecting them. This may be explained in part by their acceptance of their role as marianas who do not question their husbands or their fate as wives, and in part by their need for family and economic support. One woman spoke of how she had defended her husband from her family's criticisms, in spite of the fact that he had infected her.

I am scared that that they will attack my husband. …Because in reality he is the person who infected me. …I also don't want to point fingers, you know, because now, like they say I have to keep moving forward, if it was my destiny to live like this, what can I do? (Lucia, 31 year-old, laundry worker)

Lucia also spoke of how she initially sought help from a female psychologist to problem-solve about ending her marriage after she was infected by her husband. The psychologist's response however, was to remind her of her duties as wife and mother. She talked her into staying in the marriage, reinforcing her gender role as caretaker and suggesting that her suffering would be greater for leaving than for staying with him.

I didn't want to talk to him, I was resentful… I wanted to separate. I told him I would prefer to live alone. At that time, the psychologist told us that it would be worse because I would worry that he will get sick and then I would also get ill and what would become of my children. [She told me], “It is better if you do this together.” …Then she would arrange our appointments together and I understood [I had no choice] and so I just continued like this by his side, together.

This example shows how norms of marianismo and wifely duties override women's personal wishes and plans. Regardless of the fact that she had been infected by her husband, Lucia—and many others in the study—was not allowed to express anger, hatred, or resentment towards him. Instead, she was expected to accept her fate and make the best of it.

The Disenfranchised Mother

For many women, bearing children and becoming a mother is a sign of social prestige. In the Latin context, which is influenced by Catholicism, motherhood reflects the highest virtues of the Virgin Mary. HIV infection changes this for women by deeming childbearing an immoral act. Most of the study participants stated that they would have liked to have more children but either would not or could not because of their HIV status. The following quote is from a woman who found out that she was HIV-positive when she was pregnant. She wept deeply as she spoke about how HIV denied her the chance to have additional children, a role which she perceived to have lost because of HIV:

When I gave birth to my child, I knew that I was HIV positive, I was about 20 years old, and I couldn't have children being HIV positive … the doctor told me that I could not have children, that it was for my own good and at the moment they made me sign some papers authorizing a tubal ligation. I became very depressed, I signed the papers. But now that you ask me if I would like to have more children, I think it is something that any mother wants, what mother doesn't want to have more children? (Ana, 32 year-old, homemaker)

Another participant described how she felt when she saw HIV-infected pregnant women.

For me to see a pregnant [HIV-infected] women, which I do see many, is something that I cannot admire. I don't feel admiration, I feel sad for them, because if this has happened to us why would we purposefully keep reproducing? Am I being judgmental? (Marisol, 44 year-old, arts saleswoman)

These quotes reflect the social views that construct HIV-infected women as incapable of having children and of being immoral or selfish if they do. Not only does HIV change the expectations of women with respect to future children, but it also gives people a reason to deny women their rights to mother the children they have. The following participant tells us the story of the custody battle over her daughter and the way in which she was devalued because of her HIV status.

One day [my husband came] to visit my daughter and I let my guard down for a second and he took her and I did not see her for five months. … They [government agency] did not value my rights as a mother nor did they value the rights of my daughter. …They didn't want to give me custody of my daughter … because I had HIV … they said I was dying, that I was not doing well. The idea was that it would be best [for her] to be with her father to reduce the risk of infection. I told them if I didn't infect her in my belly, how will I infect her now, now that she is outside of my belly? (Gloria, 35 year-old, medical laboratory technician)

Gloria was receiving antiretroviral medication and was not ill when this custody battle occurred. Her quote illustrates how her HIV status transformed her identity from a once loving, caring and capable mother to a woman who was viewed as incapable, dying, and diseased.

The Effort to Reclaim Social Rights and Position

Of the 14 cases, two women told stories of how they challenged others who tried to silence them and separate them from their children. One was Gloria, who not only went to court to regain custody of her child, but also chose to break the silence about her HIV status as a way to resist the claims on her identity as a person whose life was over and who was no longer worthy of motherhood. She went on television to share her story with thousands of people. She spoke of the difficulty people had with seeing her as both an HIV-positive woman and a good mother.

They would show reports [on TV] with people with HIV/AIDS who were on their death beds. …I spoke with the [programme producer] and I told her “I do not want to appear on TV to ask for food, to ask for money, nor do I want to appear like I am sick. I do not want to beg for anything. I want them to see me for who I am, that I am well and that I am claiming my rights [as a mother].” … People now see me as a strong person, one who fights for her rights … but you know I am not always like that … at times I cry but I do not cry in front of people … at times I have felt as low as you can feel, I feel bad but I cry alone, and never in front of others.

The other person was Marisol, who challenged the stigma and discrimination from her family. She spoke of how after her HIV medications changed her appearance and she could no longer hide her HIV status, her family had distanced themselves from her and she became increasingly isolated. She described her response to family members at a party when she noticed that everyone was avoiding her and no one wanted to touch her. She shared the following story about the reaction of one of her uncles:

I greeted him, “Hello uncle,” and I gave him a kiss and he wiped his face. …I was furious … I thought to myself that all of them were hypocrites. I told them, “Take one step forward whoever doesn't think I am disgusting, and take one step back if you do think that I am disgusting.” Nobody took one step forward nor one step back; they stood there in shock. …I then purposely ran up to my room and slammed the door, then I thought to myself “Let's see who comes up.” [No one did.] My condition is obvious [speaking of her facial appearance] …it hurt me very much that [my uncle] had done this to me, that he wiped his face, damn it if you spit up at the sky, you don't know what will come down. [Questioning herself she asked] “Was I ever a prostitute? Was I a promiscuous woman for this to happen to me?”

These two women spoke out about their HIV serostatus only after they realized they had nothing left to lose. Their efforts exemplify the need to create a discourse that recognizes not only the possibility, but the reality of being an HIV-positive mariana. However, at least in this group of HIV-positive women, their efforts were exceptional in the struggle to regain their social rights and position. Most of the participants did not speak of resistance to the discourse that classified them as fallen women.

Discussion

Discourses of machismo and marianismo construct people's identities as if they were bounded at one end or the other of the identity spectrum: one is either a macho/mariana or a maricón/puta. People are then left to work within these false dichotomies to align themselves with the bounded identities that best serve them. Few of the women in this study were ‘pure’ marianas: some had had multiple partners, others had engaged in premarital sex or cohabitated with a male partner prior to marriage. However, within the context of these relationships, they followed the general rules of marianismo by being faithful and serially monogamous and, when they had children, performing their expected duties as devoted mothers. While deviating from the strict set of prescribed behaviours, these women were still seen by others as good marianas and received the social benefits accorded to women who ascribe to the general social codes.

In spite of these other deviations from the norm, it was HIV infection acquired by fulfilling their role as mariana that forced them to confront a change in their identities. For these women, HIV infection initiated the move along the identity spectrum, tainting the women's identity in the minds of others in such a way that they could not defend themselves, nor retain the prestige, rights, and social status of wife and mother. Women felt trapped by this shift in identity, especially since it was imposed on them through no fault of their own. They were innocent of the promiscuous behaviours of which they were accused, but were powerless to counter the accusations. In essence, HIV changed the rules of the identity game without giving them the instructions of how to play.

What a woman may know about HIV keeps her in fear of talking to others because of the stigma the disease holds in society, especially among women. Often, other marianas are the first to denigrate women with HIV, in part because their ignorance about sex and sexually transmitted diseases restricts their understanding of HIV, and in part because of the need to distance themselves from anyone who represents a threat to their own social position. If they are not visibly ill, HIV-positive women can deny the illness and work to preserve their identity in the realm of the mariana. However, untreated HIV does not allow one to remain silent for long. In Peru, there is no language or discourse to allow someone to live with HIV without some repercussions: all associations and assumptions are that if a woman has HIV then she must have done something “wrong.”

Machismo and marianismo set high standards for men and women as a guide and code for their behaviour; ultimately these codes of behaviour have the capacity to serve as either protective or risk factors for HIV transmission (Wood and Price 1997). Because monogamy is the norm for married women in Peru, the HIV epidemic ‘stops in them [women] and doesn't spread’ (p. 490; Cohen 2006). At-risk married women will remain invisible and silent because machismo and marianismo expect and require it. In Peru, as in other parts of the world, prevention campaigns primarily target men, as evidenced by the new prevention programs initiated in the Amazon region where programs are geared solely for men (Cohen 2006). When women are included, the focus is often on female sex workers or HIV-positive pregnant women. Yet the woman valued most in Latin societies – la mariana – remains outside prevention efforts.

Current proposals for prevention interventions from other parts of the world ask women to engage in what would be considered under marianismo as culturally radical behaviour, such as having women engage in sexual communication and asking their sex partners (husbands) to use condoms. Programmes and interventions for HIV-positive women, regardless of geographical location, need to engage with contextual realities such as poverty and economic dependence, class oppression, gender roles and power inequality in sexual relationships (Amaro and Raj 2000; Amaro et al. 2001; Rao Gupta 2000). Interventions for heterosexual women should acknowledge women's communication styles with partners and tailor programmes accordingly (Choi et al. 2004). Men's gender roles, their sexual risk-taking behaviour, and their specific prevention needs should be addressed given that men play a significant role in the context of HIV risk.

Expanding the discourse of acceptable gender roles and behaviour for both men and women under machismo and marianismo may be the answer to decreasing HIV infections. All cultures and their discourses are fluid, as is reflected in changes about machismo that show a multitude of possible macho identities, including the “brutish, gallant, or cowardly” (p. 3; Guttman 1996). For men, HIV prevention efforts could highlight the aspects of machismo that focus on being a protector, particularly their role in safeguarding their wives' esteemed role as the good mariana. Prevention messages focused on keeping the family safe would acknowledge the reality of men's greater sexual freedoms under machismo yet still support safer sexual practices by promoting condom use during relations with extramarital partners. For women, the definition of who is eligible for recognition and respect must be expanded to include HIV-positive marianas. These changes in social attitudes must be promulgated at multiple levels throughout Latino society and must involve both men and women. Interventions for both prevention and treatment need to be sensitive to and mindful of not further marginalizing and stigmatizing people infected with HIV. Given that HIV is a highly stigmatized disease, we cannot ask women to speak out about HIV until it is safe to do so, nor can we expect cultural and attitudinal changes to happen in isolation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the International AIDS Research and Training Program at the University of Washington, the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. MH-58986, J. Simoni, PI; NRSA Grant No. MH-078318, D. Valencia-Garcia, PI). We would like to thank the fourteen women who shared their stories with us, Jorge Sanchez, Aldo Lucchetti and the staff at the Impacta Clinic in Lince, Peru, and to acknowledge Karin Bleeg, Wendy Radillo, Natividad Chavez, and Maria Acosta for their transcription assistance.

References

- Alarcon JO, Johnson KM, Courtois B, Rodriguez C, Sanchez J, Watts DM, Holmes KK. Determinants and prevalence of HIV infection in pregnant Peruvian women. AIDS. 2003;17:613–618. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Raj A. On the margin: power and women's HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42:723–749. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Vega R, Valencia-Garcia D. Gender, context, and HIV prevention among Latinos. In: Aguirre-Molina M, Molina C, Zambrana R, editors. Health Issues in the Latino Community. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2001. pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Arguelles L, Rivero AM. HIV infection/AIDS and Latinas in the Los Angeles county: considerations for prevention treatment and research practice. California Sociologist. 1988;11:69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo P. Mujeres Latinas: santas y marquesas. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8:308–319. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M. In: Understanding Latino families: scholarship, policy, and practice in social science theorizing for Latino families in the age of diversity. Zambrana RE, editor. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Miller J. Toward a new psychology of women. Boston: Beacon Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Caceres CF. HIV among gay and other men who have sex with men in Latin America and the Caribbean: a hidden epidemic? AIDS. 2002;16:S23–33. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200212003-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo H. The night is young: sexuality in Mexico in the time of AIDS. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. CDC HIV/AIDS fact sheet: HIV/AIDS among Women, 2005. Atlanta: U.S.A.: Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Wojcicki J, Valencia-Garcia D. Introducing and negotiating the use of female condoms in sexual relationships: qualitative interviews with women attending a family planning clinic. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8:251–261. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000044073.74932.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Peru: A new nexus for HIV/AIDS research & Peru: universal access: more goal than reality. Science. 2006;313:488–490. doi: 10.1126/science.313.5786.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Diaz L. Culturally relevant issues and treatment implications for Hispanics. In: Koslow DR, Salett E, editors. Crossing cultures in mental health. Washington, DC: Society for International Education Training and Research; 1989. pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G. Love, passion and rebellion: ideologies of HIV risk among Latino gay men in the USA. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 1999;1:277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Latino families in therapy: a guide to multicultural practice. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Few C. The politics of sex research and constructions of female sexuality: what relevance to sexual health work with young women? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25:615–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-1-1997025615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee JP. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. London: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore DD. Manhood in the making: cultural concepts of masculinity. New York: Vail-Ballou Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman MC. The meanings of macho: Being a man in Mexico City. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of Carolina Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S. Gender, sexuality and heterosexuality. London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Alarcon J, Watts DM, Rodriguez C, Velasquez C, Sanchez J, Lockhart D, Stoner BP, Holmes KK. Sexual networks of pregnant women with and without HIV infection. AIDS. 2003;17:605–612. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless S, Kippax S, Crawford J. Dirty, diseased and undeserving: the positioning of HIV positive women. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43:1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: sex, culture, and empowerment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14:186–192. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín BV, Gómez CA. Latinos, HIV disease & culture: strategies for AIDS prevention. In: Cohen PT, Sande MA, Volberding PA, editors. The AIDS Knowledge Base. Second. Boston: Little Brown & Co.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marín BV, Tschann JM, Gómez CA, Kegeles SM. Acculturation and gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: Hispanic vs Non-Hispanic white unmarried adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:1759–1761. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.12.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Marín BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Cantero PJ, Simoni JM. Is acculturation associated with sexual risk behaviors? An investigation of HIV-positive Latino men and women. AIDS Care. 1998;10:283–295. doi: 10.1080/713612418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Mendoza W, Krone MR, Meza R, Caceres CF, Coates TJ, Klausner JD. Clients of female sex workers in Lima, Peru: a bridge population for sexually transmitted disease/HIV transmission? Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:337–342. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud. [November, 2006];2005 http://minsa.gob.pe.

- Mirande A. Chicano fathers: traditional perceptions and current realities. In: Bronstein P, Cowan CP, editors. Fatherhood today: men's changing role in the family. Oxford England: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno CL. The relationship between culture, gender, structural factors, abuse, trauma, and HIV/AIDS for Latinas. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:340–352. doi: 10.1177/1049732306297387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nencel L. Ethnography and Prostitution in Peru. Pluto Press; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Paternostro S. In the land of God and man: confronting our sexual culture. New York: Dutton; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Peragallo N. Latino women and AIDS risk. Public Health Nursing. 1996;13:217–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N, Hardy C. Sage University Paper Series on Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. Discourse analysis: investigating processes of social construction. [Google Scholar]

- Rao Gupta G. Gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: the what, the why, and the how. Plenary Address, XIII International AIDS Conference.2000. [Google Scholar]

- Savage J. One voice, different tunes: issues raised by dual analysis of a segment of qualitative data. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;31:1493–1500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:1372–1380. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens EP. Marianismo: The other face of machismo in Latin America. In: Pescatelo A, editor. Female and Male in Latin America. University of Pittsburg Press; 1973. pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tabet SJ, Sanchez J, Lama P, Goicochea P, Campos M, Rouillon JL, Cairo L, Ueda D, Watts C, Celum C, Holmes KK. HIV, syphilis and heterosexual bridging among Peruvian men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2002;16:1271–1277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200206140-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US AID. [November, 2006];2005 http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/aids/Countries/lac/peru.html.

- World Health Organization. [November, 2006];2006 http://www.who.int/tb/hiv/en/

- Wood ML, Price P. Machismo and marianismo: implications for HIV/AIDS risk reduction education. American Journal of Health Studies. 1997;13:44–52. [Google Scholar]