Abstract

The C/D box small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) represent an essential class of small nucleolar RNAs that guide 2′-O-Rib methylation of ribosomal RNAs and other RNAs in eukaryotes. In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), >100 C/D snoRNAs have been identified, most of them encoded by polycistronic gene clusters, but little is known on the factors controlling their biogenesis. Here, we focus on the identification of factors controlling the processing of tRNA-snoRNA dicistronic precursors (pre-tsnoRNA) synthesized by RNA polymerase III and producing tRNAGly and C/D snoR43. We produced radiolabeled RNA probes corresponding to different pre-tsnoRNA mutants to test their impact on processing in vitro by a recombinant tRNAse Z, the Arabidopsis endonuclease that processes the 3′end of tRNAs, and by nuclear extracts from cauliflower (Brassica oleracea) inflorescences that accurately process the pre-tsnoRNA. This was coupled to an in vivo analysis of the processing of tagged pre-tsnoRNA mutants expressed in Arabidopsis. Our results strongly implicate tRNase Z in endonucleolytic cleavage of the pre-tsnoRNA. In addition, they reveal an alternate pathway that could depend on a tRNA decay surveillance mechanism. Finally, we provide arguments showing that processing of pre-tsnoRNA, both in planta and by nuclear extracts, is coupled to the assembly of snoRNA with core proteins forming the functional snoRNP (for small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein complex).

The small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) represent a major class of RNA that guide modifications of >100 nucleotides on the 18S, 5.8S, and 25S ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs). They are distributed into two major families: the C/D box snoRNAs that guide 2′-O-Rib methylation and the H/ACA box snoRNAs that guide pseudouridylation. In addition, some snoRNAs and the related scaRNAs that are localized in Cajal bodies direct modification of other substrates like the U snRNAs controlling splicing in animals. Finally, some C/D snoRNAs, such as the conserved U3 snoRNA have RNA chaperone activity and control specific cleavages of the primary precursor encoding the 18S, 5.8S, and 25S rRNAs (for review, see Filipowicz and Pogacic, 2002; Matera et al., 2007).

The methylation guide C/D box snoRNAs are characterized by two conserved boxes, C (RUGAUGA) and D (CUGA), flanked by 5′- and 3′-terminal inverted repeats, respectively. The guide element of 10 to 20 nucleotides complementary to the 2′-O-Rib methylation site on the target RNA is adjacent to a D or D′ internal box. In vivo, the C/D snoRNAs form a functional snoRNP (for small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein complex) with four highly conserved nucleolar proteins: fibrillarin (Nop1p in yeast), which is the RNA methylase; the 15,5 K protein (Snu13p in yeast); and the Nop56 and Nop58 proteins. Assembly of this C/D snoRNP is initiated by the 15,5 K protein that binds to a kink-turn RNA fold formed by the C/D boxes and then recruits fibrillarin, Nop56, and Nop58 (Watkins et al., 2002). Association with these core proteins is essential for the stability and accumulation of the C/D snoRNA as well as its nucleolar localization (Filipowicz and Pogacic, 2002; Matera et al., 2007).

A remarkable feature of snoRNAs is their diverse mode of expression depending on the biological systems. In animals, most are intronic, i.e. encoded within introns of protein coding genes. In yeast, most snoRNAs are encoded as independent genes transcribed by RNA polymerase II, but a few snoRNAs are also found in introns and in polycistronic clusters. In plants, although independent and intronic snoRNA genes also occur, most are encoded by polycistronic clusters (Brown et al., 2003). These clusters are either transcribed from their own promoter or are nested within introns of protein-coding genes. In addition, plants have a unique mode of snoRNA expression corresponding to dicistronic tRNA-C/D snoRNA genes, hereafter called tsnoRNA, transcribed by RNA polymerase III (Kruszka et al., 2003).

In any case, transcription of snoRNA genes by RNA polymerase II or III always produces a larger precursor that has to be processed to give the mature snoRNA. The diversity in the structure of these precursors implicates different processing steps. The processing of intronic, polycistronic, or monocistronic snoRNA precursors requires diverse initial steps to create entry sites for further processing by exonucleolytic trimming to create the mature snoRNA ends. In animals, in vitro processing with acellular extracts indicates that the major pathway for intronic snoRNAs is splicing of the host mRNA, debranching of the lariat intron, and final 5′ and 3′ exonucleolytic trimming to produce the mature snoRNA ends (Kiss and Filipowicz, 1995). In the case of monocistronic and polycistronic snoRNAs, genetic analysis in yeast has shown the primary precursor is first cleaved by Rnt1p, an ortholog of the prokaryotic RNase III endonuclease. This creates entry sites for trimming by Rat1p and Xrn1p 5′-3′ exonucleases and the 3′-5′ exonucleolytic exosome complex producing the mature snoRNAs (Petfalski et al., 1998; Allmang et al., 1999).

In plants, little is known about the factors controlling processing of snoRNA precursors and assembly of the snoRNP. Polycistronic snoRNAs precursors, which represent most genes in plants, are probably processed by a pathway similar to that in yeast, implicating an Rnt1p plant homolog (Comella et al., 2008) to create entry sites for subsequent exonucleolytic trimming. This is supported by a recent study in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) for genome-wide analysis of transcripts affected by mutation of exosome subunits (Chekanova et al., 2007). This analysis revealed that polycistronic snoRNA precursors require this activity for normal processing, suggesting that the last steps of snoRNA processing probably occur as in other systems (Chekanova et al., 2007).

In contrast to the previous cases, the dicistronic tRNA-snoRNA precursors encoded by tsnoRNA genes are unique to plants. The tsnoRNA gene family in Arabidopsis includes 12 members (named tsnoR43.1 to tsnoR43.12) (Kruszka et al., 2003). They are transcribed using the tRNA promoter by RNA polymerase III and produce a primary tRNAGly-snoR43 precursor with a typical tRNA 5′ leader and 3′ U-stretch terminal extensions. Using the tagged version of the tsnoR43.1 gene expressed in Arabidopsis, it was shown that the dicistronic precursor is processed to liberate both the tRNAGly and the C/D snoR43.1 (Kruszka et al., 2003). This mode of expression has no equivalent in yeast or animals and raises questions on the processing of this pre-tsnoRNA. Based on the structure of the precursor and characterization of intermediate precursors produced in vivo, a two-step processing pathway was proposed: first, 5′ and 3′ extension are eliminated, producing a shorter precursor that can be visualized in vivo, followed by a second endonucleolytic cut that cleaves this precursor to produce both the tRNA and the snoRNA (Fig. 1). We further proposed that the plant tRNase Z endonuclease that processes the 3′end of the tRNAs is implicated in endonucleolytic cleavage of tRNA-snoRNA precursors to liberate both the tRNAGly and the snoR43. This hypothesis was strongly supported by the confirmation that purified recombinant tRNase Z from Arabidopsis accurately cleaved the intermediate precursor to liberate both the tRNAGly and the C/D snoR43.

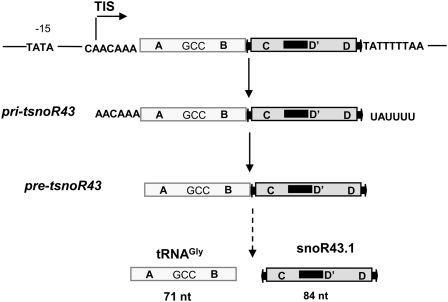

Figure 1.

Structure of the tsnoR43.1 gene and its transcript products identified in Arabidopsis. The figure recapitulates previous data (Kruszka et al., 2003). tRNAGly and snoR43.1 mature sequence are schematized by large boxes. Pri-tsnoR43 and pre-tsnoR43 refer to primary and intermediate precursors, respectively, identified by primer extension and RNase mapping. A and B boxes represent conserved promoter elements in the tRNA. The arrow on the CAA element indicates the previously mapped TIS. The TATA element is required for RNA polymerase III initiation, and the T stretch is the RNA polymerase III termination element (Yukawa et al., 2000). GCC in the tRNA sequence indicates the anticodon. The C and D boxes are shown flanked by arrows representing the inverted repeats at the 5′ and 3′ends of snoRNA. The black bar adjacent to the D' box represents the antisense element targeting an 18S rRNA residue (Kruszka et al., 2003).

To confirm the implication of tRNAse Z and identify factors controlling processing of tsnoR43 precursors, we developed complementary approaches combining reverse genetics to express tsnoR43 mutants in planta with a biochemical approach using recombinant tRNAse Z activities and nuclear extracts that accurately process the tsnoRNA precursor. Our results strongly confirm the implication of tRNase Z and also suggest the occurrence of an alternative pathway independent of this activity to process the dicistronic precursor. In addition, our analysis strongly supports a tight association of processing of the precursor with assembly of the C/D snoRNP, both in vivo and in vitro.

RESULTS

Characterization of T-DNA Mutant Line on AthTrzL1 and AthTrzS1

Previous studies had shown that purified recombinant tRNA Z from Arabidopsis (renamed AthTrzS1 according to new nomenclature; Canino et al., 2009) accurately cleaves the intermediate precursor pre-tsnoR43 in vitro (Kruszka et al., 2003). In Arabidopsis, there are four gene homologs encoding two long and two short forms of tRNase Z, named AthTrzL1 /2 and AthTrzS1/ 2, respectively (Schiffer et al., 2002; Spath et al., 2007; Canino et al., 2009). The subcellular localization of GFP fusions indicated that only one is nuclear, corresponding to AthTrzL1, which has a dual localization as it is also found in mitochondria. The AthTrzS1–GFP fusion was localized in the cytoplasm, but we cannot exclude a transient localization or low levels of AthTrzS1 in the nucleus. The two other tRNA Z-GFP fusions were addressed to the chloroplast and mitochondria, respectively (Canino et al., 2009). Thus, because processing of snoRNAs occurs in the nucleus, AthTrzL1 is the candidate for processing the pre-tsnoR43.

To confirm the implication of AthTrzL1 in pre-tsnoRNA processing in vivo, but also eventually of AthTrzS1, we isolated and characterized T-DNA insertional mutant lines in both genes. Nevertheless, although expression of AthTrzL1 or AthTrzS1 in these mutant lines was completely abolished, no phenotypic alteration was observed in these plants. In addition, we did not detect any defect in accumulation of mature snoR43.1 or production and processing of the tRNA-snoR43.1 precursor. This result could be explained by gene redundancy as low levels or a transient nuclear localization of AthTrzS1 could complement AthTrzL1. This is supported by the fact we were unable to produce AthTrzS1 × AthTrzL1 double mutants, which strongly suggests that these are not viable. An alternate explanation is the implication of another tRNAse Z independent pathway in processing of tsnoR43 precursors.

Processing of tRNAGly-snoR43.1 Mutants by Recombinant AthTrzL1 and AthTrzS1

To investigate the specificity of purified rAthTrzL1 and rAthTrzS1, we analyzed their capacity to process different mutants of the tsnoRNA precursors.

We produced a series of mutants of either the single tagged gene, tsnoR43tag1, with a 16-mer replacing the rRNA antisense element, or the double tagged gene, tsnoR43tag12, which has an additional tag in the tRNA (Fig. 2). The tagged constructs were used here because they are essential for analysis of their processing in transgenic lines. Tag 1 and tag 2 have no effect on the expression of this gene or the stability of the tRNA or snoRNA in vivo (Kruszka et al., 2003).

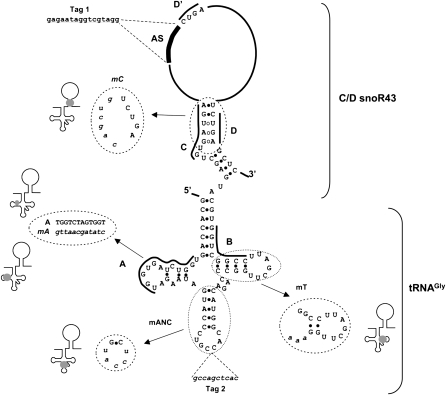

Figure 2.

Predicted secondary structure of pri-tsnoR43 and mutants. The secondary structure was drawn according to tRNAGly and C/D snoR43 (Watkins et al., 2002). Black lines alongside sequences indicate the conserved A, B, C, D, and D' boxes. Black circles indicate canonical nucleotide pairing. White circles indicate noncanonical pairing on C and D boxes forming the k-turn motif on the C/D snoRNAs. AS indicates the rRNA antisense element associated with the D' box. Tag 1, replacing the AS element and tag 2, inserted in the anticodon, are shown. All mutant sequences are indicated in lowercase in dotted circles showing the predicted effect on secondary structure.

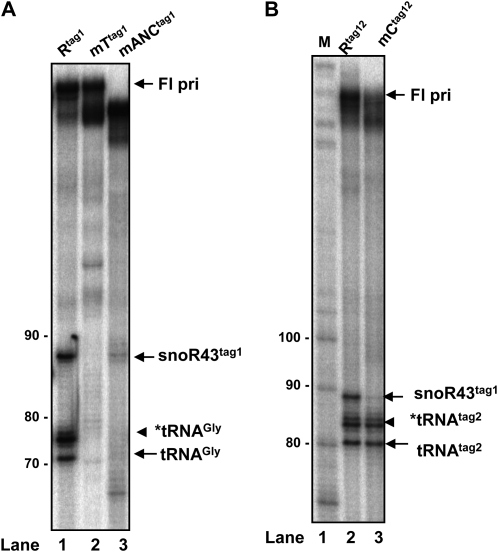

It was previously reported that rAthTrzS1 processes the intermediate pre-tsnoR43.1, which lacks the 5′- and 3′-terminal extensions (Fig. 1) but cannot cleave the primary pri-tsnoR43 precursor (Kruszka et al., 2003). Therefore, tagged pre-tsnoR43 substrates were synthesized in vitro and tested for cleavage by rAthTrzS1 and rAthTrzL1. We observed that the wild-type single tagged pre-tsnoR43tag1 is accurately processed by both rAthTrztag1 and rAthTrzL1, with comparable efficiency, producing equal amounts of the mature tRNAGly and snoR43tag1 (Fig. 3). These 5′end termini of the in vitro-processed snoRNA had been previously mapped by primer extension, confirming its accurate processing (Kruszka et al., 2003). The two bands detected for the snoR43tag1 reflect the same situation occurring in vivo, in which termini of C/D snoRNAs are heterogeneous and differ by one or two nucleotides produced by unequal exonucleolytic trimming (Barneche et al., 2001; Kruszka et al., 2003).

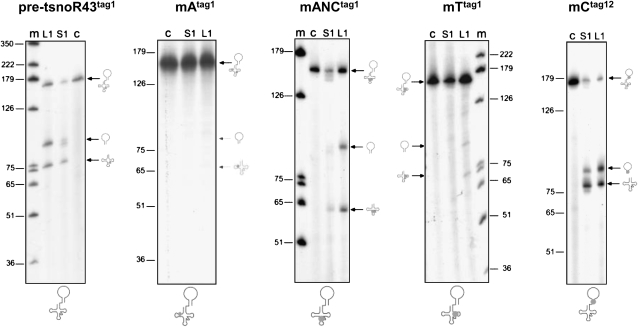

Figure 3.

Processing of pre-tsnoR43 by recombinant AthTrzS1 and AthTrzL1. Tagged intermediate pre-tsnoR43 substrates lacking 5′- and 3′-terminal extensions (Fig. 1) were synthesized in vitro and incubated with purified recombinant rAthTrzS1 and rAthTrzL1 (see “Materials and Methods”). Substrates used in the reactions are indicated above the gels: pre-tsnoR43tag1 refers to wild-type substrate. mAtag1, mANCtag1, mTtag1, and mCtag12 refer to single tagged (tag 1) and double tagged (tag 12) mutant substrates (Fig. 2). The secondary structure of the mutants with mutation indicated by the gray circle is schematically shown below the gels. Lane m: marker size. Lane C: control reaction without addition of proteins. Lanes S1 and L1: incubation with rAthTrzS1 and rAthZL1, respectively.

Subsequently, we generated different variants of the dicistronic precursor that should affect tRNA 3′end processing by rAthTrzS1 (Schiffer et al., 2001). The first mutant is a substitution of 12 nucleotides of the A box of the tRNA (Fig. 2). This totally inhibited cleavage of the pre-tsnoRNA substrate by both rAthTrzL1 and rAthTrzS1 (Fig. 3). We also analyzed two other mutants corresponding to mANCtag1, with a short deletion in the anticodon region, and mTtag1 with a three nucleotide substitution in the T arm where two Cs and one G were changed into As (Fig. 2). Cleavage of mANCtag1 by rAthTrztag1 was reduced compared to that of the wild-type substrate, but it was still specific, as revealed by the expected size of the products (Fig. 3). A more drastic effect was observed on cleavage of mTtag1 by rAthTrzL1 and rAthTrzS1, as only a minor fraction of the substrate was cleaved in both cases (Fig. 3). This effect was more drastic with rAthTrzS1 than with rAthTrzL1 (Fig. 3).

Finally, we tested the double tagged mutant, mCtag12, in which the C box is mutated to disrupt the kink-turn fold of the C/D snoRNA (Fig. 2). This is essential for correct folding and stability of the C/D snoRNA in vivo. Clearly, mutating the C box has little effect on the efficiency or accuracy of processing of the pre-tsnoR43tag1 substrate by rAthTrzL1 or rAthTrzS1 to produce the mature tagged tRNAtag2 and mC.snoR43tag1 (Fig. 3). The slightly different proportions of mature mC.snoR43tag1 and tRNAtag2 observed with rAthTrzS1 probably result from a greater sensitivity of mC.snoR43tag1 to degradation (see below).

Altogether, these results are in agreement with the reported specificity of rAthTrzS1 in processing the 3′ends of tRNAs (Schiffer et al., 2001). They strongly support specific cleavage of the tsnoRNA precursor by AthTrzL1 in vivo. In addition, these results also show that AthTrzS1 has similar specificity and could replace rAthTrzL1 for processing of pre-tsnoRNA.

Development of a Nuclear Extract That Accurately Processes the tsnoR43 Precursors

We developed a nuclear extract that could accurately process the precursors of tsnoR43 using cauliflower inflorescences, a tissue highly enriched in meristematic cells that allow extraction of large amounts of nuclear proteins.

This was achieved by adapting the protocol used to extract the plant RNA polymerase I holoenzyme (Saez-Vasquez and Pikaard, 1997; see “Materials and Methods”).

The [32P]-radiolabeled substrates corresponding to pri-tsnoR43 and pre-tsnoR43 precursors were synthesized by T7 RNA polymerase transcription of PCR amplified templates containing the nontagged tsnoR43.1 gene (Fig. 4A). The labeled substrates were incubated with fresh nuclear extracts and the cleavage products separated by electrophoresis in sequencing gels.

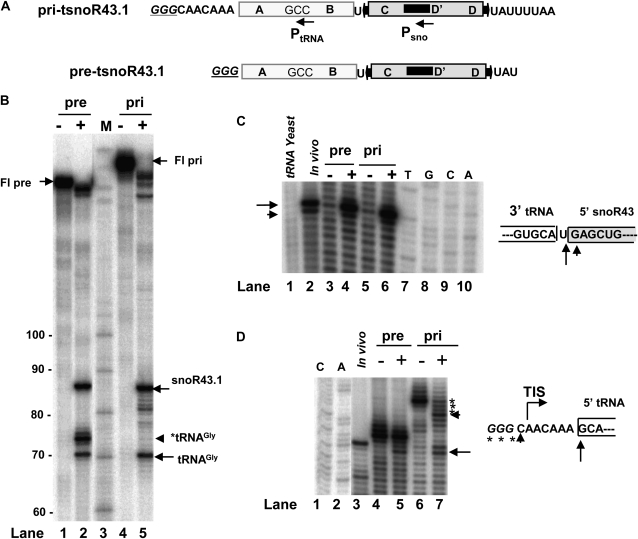

Figure 4.

Processing of tsnoR43 precursors by nuclear extracts. A, RNA substrates synthesized in vitro (see “Materials and Methods”). Underlined capitals in italic indicate additional nucleotides at the 5′end of substrates compared with precursors synthesized in vivo. PtRNA and Psno indicate primers specific to tRNA and the snoR43.1. B, Processing of pre-tsnoR43.1 and pri-tsnoR43.1 substrates by nuclear extracts. + and − indicate presence or absence, respectively, of nuclear extract in the cleavage assay. After incubation, samples were extracted and analyzed on a sequencing gel. M indicates Mr markers. Fl-pre and Fl-pri indicate full-length substrate. Position of mature snoR43.1 and tRNAGly are indicated. *tRNAGly indicates tRNAGly with the nonprocessed GGG extension. C, Mapping of cleavage site by primer extension using primer Psno. Pre-tsnoR43.1 and pri-tsnoR43.1 were synthesized in vitro and assayed for cleavage by nuclear extracts. + and − indicate presence or absence, respectively, of nuclear extract in the cleavage assay. After cleavage reaction, RNA samples were extracted and submitted to primer extension analysis using the primer Psno. Arrows indicate cleavage sites. TCGA indicates sequence ladder. Boxes indicate the 3′end of the tRNA and the 5′end of the snoR43.1, respectively. D, Mapping of cleavage site by primer extension using a PtRNA primer. Primer extension analysis as in C but using the primer PtRNA. Arrows indicate cleavage sites. Box indicates the 5′end of the tRNA.

In most active extracts, nearly all of the pri-tsnoR43 full-length substrate was rapidly processed into the snoR43.1 and tRNAGly (Fig. 4B, lane 5). Nuclear extracts were also efficient in processing the pre-tsnoR43, corresponding to the intermediate precursor lacking the 5′- and 3′-terminal extensions (Fig. 4B, lane 2). In this case, an additional product of 74 nucleotides accumulates (*tRNAGly). This corresponds to mature tRNAGly plus three additional G nucleotides on the 5′end, introduced by T7 RNA polymerase, which initiates transcription upstream from the normal CAA transcription initiation site of tRNAs (see below). Considering the stoichiometry of cleavage, one should expect equal amounts of tRNAGly and snoR43.1, which is roughly the case with pri-tsnoR43 substrate. Overall, these results were reproducible, but there was considerable variability in the efficiency and stability of the different extract preparations.

To confirm accurate cleavage of both substrates, we mapped the 5′ extremities of the cleaved products by primer extension using unlabeled pri-tsnoR43 or pre-tsnoR43 templates. After incubation with nuclear extracts, the RNA products were extracted and analyzed by primer extension using labeled primers Psno and PtRNA complementary to the snoR43.1 or the tRNAGly, respectively (Fig. 4A). Mapping of the 5′end of the snoR43.1 with primer Psno detected a major and a minor signal, clearly above background after treatment with the nuclear extracts (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 3 and 4 and lanes 5 and 6). These correspond to the two 5′end signals produced by the mature snoR43.1 isolated from plants (lane 2) and are absent in a control reaction using yeast tRNA as substrate (lane 1).

Mapping of the 5′ tRNA termini with primer PtRNA revealed that both substrates have two or three additional nucleotides incorporated by T7 RNA polymerase upstream from the 5′ends, corresponding to in vivo precursor ends. In the case of pre-tsnoR43, the 5′end extends beyond the GCA 5′end of tRNAGly mapped in vivo (Fig. 4D, compare lanes 3 and 4). We observed that nuclear extracts are not efficient to eliminate these additional nucleotides (compare lanes 4 and 5). This explains the strong *tRNA signal observed using the pre-tsnoR43 substrate (Fig. 4B, lane 2).

In the case of the pri-tsnoR43 substrate, additional nucleotides extend beyond the normal CAA element where transcription initiates in vivo (Fig. 4D, lane 6). Treatment of pri-tsnoR43 with nuclear extracts gives an enhanced signal at the normal transcription initiation site (TIS), probably due to trimming of the additional nucleotides by 5′-3′ exonucleases in the extracts (lane 7). More importantly, we also observed an increase in the signal mapping at the 5′end of the mature tRNAGly (lane 7), which corresponds to the 5′end signal mapped for tRNAGly in vivo (lane 3). This indicates that nuclear extracts accurately process the pri-tsnoR43 producing the 5′end of the mature tRNAGly.

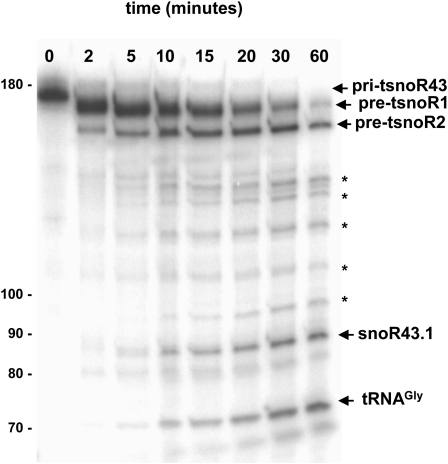

Kinetic analysis of the nuclear extract processing of pri-tsnoR43 shows progressive cleavage of the full-length substrate with rapid appearance of pre-tsnoR1 (Fig. 5). Subsequently, the pre-tsnoR1 progressively diminishes, while pre-tsnoR2, a smaller intermediate species, accumulates. These two intermediates have not been characterized in detail, but we have indirect evidences indicating that they would be generated by sequential removal first of the 5′ extension of the pri-tsnoR43 and than of the 3′end U stretch (Kruszka et al., 2003; data not shown). This is correlated with the progressive appearance of two major signals of 84 and 71 nucleotides that correspond to the mature snoR43.1 and tRNAGly respectively. Other signals were also detected using these extracts but were not identified. In most active extracts, these additional fragments are not observed, and their presence reflects the variability between different preparations.

Figure 5.

Kinetics analysis for pri-tsnoR43 cleavage by nuclear extracts. The pri-tsnoR43 substrate was incubated with nuclear extracts for the indicated times. After incubation, RNA samples were extracted and analyzed on a sequencing gel. Pre-tsnoR1 and pre-tsnoR2 indicate intermediate processed products. Asterisks indicate unidentified signals. Numbers at the left side of the gel indicate nucleotides size markers.

Altogether, the kinetic analysis shows that the nuclear extract processing of pri-tsnoR43 produces an intermediate precursor that is subsequently processed into mature tRNAGly and snoR43.1.

Processing of tsnoR43 Precursor Mutants in Nuclear Extracts

We tested the capacity of nuclear extracts to process the tsnoR43 mutants that affect processing by rAthTrzS1 and rAthTrzL1. To compare this with processing by rAthTrzS1, which can only process the pre-tsnoR43 (Kruszka et al., 2003), we used the single tagged pre-tsnoR43tag1 mutants. Nuclear extracts efficiently processed the pre-tsnoR43tag1 substrate producing the 87-nucleotide signal, corresponding to the tagged snoR43tag1, and the 71- and 74-nucleotide signals of the *tRNAGly and tRNAGly (Fig. 6A, lane 1). Nevertheless, the nuclear extracts were extremely inefficient in processing mutants mANCtag1 and mTtag1, with nearly undetectable amounts of cleaved products (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 3). This is in agreement with the results obtained on processing of these mutants by rAthTrzS1 and rAthTrzL1 (Fig. 3).

Figure 6.

Cleavage of tagged tsnoR43 mutants by nuclear extracts. A, Nuclear extract cleavage of single tagged pri-tsnoR43tag1 wild type (Rtag1) and mutants mTtag1 and mANCtag1. Numbers at the left side of the gel indicate nucleotide size markers. B, Nuclear extract cleavage of double tagged pri-tsnoR43 (Rtag12) and mutant mCtag12. M lane corresponds to size markers.

A different situation was observed with the double tagged mutant probe mCtag12 (Fig. 2). The wild-type pre-tsnoR43tag12 is correctly processed by the nuclear extracts, producing both the expected tRNA and snoRNA signals (Fig. 6B, lane 2). Remarkably, mutation of the C box drastically affects accumulation of the mature mC.snoR43tag1 but does not affect accurate processing of the tRNAtag2 (lane 3). Considering that the C box is required to assemble a functional snoRNP and therefore stabilize the snoRNA, this indicates that the mCtag12 is correctly processed, producing the mC.snoR43tag1, but is subsequently degraded (see “Discussion”). This is supported by the observation that processing of the mCtag12 substrate by purified rAthTrzS1 and rAthTrzL1 produces both the tRNA and the snoRNA, which both accumulated (Fig. 3).

Processing of tsnoR43 Precursor-Tagged Mutants in Planta

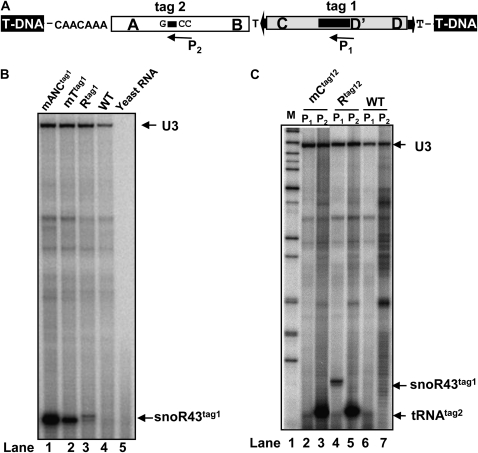

Processing of the tsnoR43 mutants in planta was analyzed by expressing the tagged tsnoR43 genes in Arabidopsis (Kruszka et al., 2003). We previously showed that a tsnoR43tag12 gene tagged both on the snoRNA (tag 1) and the tRNA (tag 2) can be expressed from their own tRNA promoter in stably transformed Arabidopsis lines, producing both the tagged snoR43tag1 and tRNAtag2 (Fig. 7A). Expression of the tagged mature and precursor transcripts could be specifically distinguished from the endogenous tsnoR43 transcripts by either reverse transcription-PCR or primer extension using primers complementary to the tags (Kruszka et al., 2003). Here, we adapted this assay to analyze expression of different tsnoR43 mutants tested previously in vitro. A double tagged gene (Fig. 2) was used to express snoRNA mutant mCtag12 to allow detection of both the tRNAtag2 and mC.snoR43tag1. Single tagged tsnoR43tag1 genes (Fig. 2) were expressed for tRNA mutants mANCtag1 and mTtag1, as the mutated tRNA could be directly tested with primers specific to it.

Figure 7.

Expression and analysis of tagged pri-tsnoR43 mutants processing in planta. A, Schematic representation of the tsnoR43 gene cloned into the T-DNA cassette used to create transgenic plants. P1 and P2 are primers used for mapping the tagged snoR43tag1 and tRNAtag2, respectively. B, In planta analysis of processing of pri-tsnoR43tag1 and mutants on the tRNA structure. Total RNA from the transgenic lines expressing pri-tsnoR43tag1 (Rtag1), mANCtag1, and mTtag1 was used for primer extension using primer P1 to detect the snoR43tag1. For comparative analysis, primer extensions were done in the presence of a primer specific to endogenous U3. WT indicates primer extension with primer P1 on total RNA from nontransgenic Arabidopsis. Yeast tRNA is a control for the substrate specificity of primer extension. C, In planta analysis of processing pri-tsnoR43tag12 and mutant mCtag12. Total RNA from transgenic lines expressing the double tagged tsnoR43tag12 (Rtag12) or mCtag12 was used for primer extension with primers P1 to detect the snoR43tag1 or P2 to detect the tRNAtag2, as indicated. Yeast tRNA is a control for primer extension assay.

We applied this assay to test the expression and processing of the different mutants previously assayed with purified rAthTrz and the nuclear extracts. Expression was tested by primer extension using primer P1 to detect the snoR43tag1 (Fig. 7A) on total RNA extracted from transgenic seedlings. As control for RNA substrate calibration, we included a primer to simultaneously detect the endogenous U3 snoRNA, which can easily be distinguished from snoR43tag1 by its size. Analysis of single tagged tsnoR43tag1 expressed in the transgenic plants shows major and minor signals at 62 and 61 nucleotides, respectively (Fig. 7B, lane 3), corresponding to the 5′end of snoR43 mapped in vivo (Fig. 4C, lane 2). These signals are specific and are not detected in control lanes with tRNA substrates (Fig. 7B, lane 5) or when using RNA samples from nontransgenic Arabidopsis (lane 4). Surprisingly, the mTtag1 mutant showed much higher expression of the snoR43tag1, which was correctly processed to its 5′end (lane 2). An even greater expression of snoR43tag1 was detected in the mANCtag1 mutant, again showing correct maturation of the 5′end (lane 1). These results are in contradiction with the effect of these mutations observed in vitro, both with rAthTrzS1 and rAthTrzL1 (Fig. 3), or the nuclear extracts (Fig. 6A), in which production of snoR43 was drastically affected. We were unable to detect accumulation of processed mutant tRNAs in these transgenic lines, suggesting rapid degradation of the mutated tRNAs in the plant (data not shown). We interpret these results as evidence for an alternate pathway for tsnoR43 processing independent of endonucleolytic cut by AthTrz (see “Discussion”).

Finally, we analyzed the processing of double tagged mCtag12. In transgenic plants expressing wild-type tagged tsnoR43tag12, we observe production of both the tRNAtag2 (Fig. 7C, lane 5) and snoR43tag1 (Fig. 7C, lane 4), which are specifically detected with primers P2 and P1, respectively (Fig. 7A). These primers are specific for the transgene products and do not detect the endogenous snoR43.1 (Fig. 7B, lane 4, and Fig. 7C, lane 6) or tRNAGly (Fig. 7C, lane 7). Nevertheless, a considerable difference in the level of detection of the tRNAtag2 and snoR43tag1 was observed, compared with equal loading evaluated by primer extension of endogenous U3. This could reflect either differential stability of both the snoR43tag1 and the tRNAtag2 or different efficiency of the primer extension reaction on the two templates. In any case, mCtag12 analysis in planta showed that this mutation drastically reduces accumulation of snoR43tag1 (Fig. 7C, lane 2) but does not affect accumulation of the tRNAtag2 (Fig. 7C, lane 3). This result is in perfect agreement with that obtained for processing of this mutant in vitro by the nuclear extracts (Fig. 6B). It indicates that the mCtag12 precursor is correctly transcribed and processed, but the snoR43tag1 does not accumulate because it is rapidly degraded. Thus, mC.snoR43tag1 is sensitive to exonucleases in the nuclear extracts and in vivo but is more stable after treatment with purified rAthTrzS1 or rAthTrzL1 (see “Discussion”).

DISCUSSION

We previously proposed that processing the dicistronic tsnoRNA precursor to liberate the C/D snoRNA involves tRNA processing activities, including AthTrzS1 (Kruszka et al., 2003). Comparative analysis of processing of tsnoR43 mutants by recombinant tRNase Z enzymes and nuclear extracts from cauliflower (Brassica oleracea), coupled with expression of the tagged mutants in transgenic Arabidopsis lines, supports our model and further implicates tRNase Z in pre-tsnoR43 endonucleolytic cleavage to separate the tRNA from the snoRNA. It also reveals additional activities that can compensate for tRNase Z, supporting the existence of an alternative pathways for tsnoR43 processing. Finally, the data reported here strongly support tight coupling of processing of pri-tsnoR43 and assembly of the C/D snoRNP in vitro, as it occurs in vivo (see below).

Nuclear AthTrzS1 and AthTrzL1 Process pre-tsnoR43 Accurately

The effect of distinct tsnoRNA mutations on the processing of pre-tsnoR43 by rAthTrzL1 or rAthTrzS1 clearly shows that these activities can specifically cleave the intermediate precursor in vitro. Inhibitory mutations correspond to those on the tRNA (mT and mANC), whereas disrupting the snoRNA structure (mC) had no effect (Fig. 3). This perfectly corresponds to the reported specificity for tRNase Z, which is directed only by the tRNA structure (Schiffer et al., 2001).

The implication of AthTrzL1 and/or rAthTrzS1 in pre-tsnoR43 cleavage is further supported by processing of pri-tsnoR43 and pre-tsnoR43 by nuclear extracts. Processing of both precursors with nuclear extracts was totally inhibited by mutations in the tRNA, similar to the response of rAthTrzL1 and rAthTrzS1. Unfortunately, we were unable to confirm this by depleting tRNase Z activity in the nuclear extracts from B. oleracea because the antibodies prepared against the Arabidopsis proteins do not recognize the predicted BoTrzS1 or BoTrzL1 homologs (data not shown).

Altogether, these results strongly support a role for the nuclear/mitochondrial AthTrzL1 in tsnoR43 processing in the nucleus (Kiss, 2004; Matera et al., 2007). However, we cannot exclude a role for AthTrzS1. Although AthTrzS1:GFP fusion is mainly localized in the cytoplasm, we do suspect low levels or a transient localization in the nucleus. Neither AthTrzL1 nor AthZS1 T-DNA insertional mutants have any phenotypic alteration (data not shown; Canino et al., 2009). The fact that AthTrzS1 can also cleave the tsnoR43 precursor in vitro suggests that it can compensate for AthTrzL1 depletion. Indeed, the fact that we were unable to produce the double AthTrzS1 × AthTrzL1 mutants is likely because these are not viable. This strongly suggests that at some point both activities accomplish a similar or redundant essential activity.

Nuclear Extracts Have Additional Activities Processing tsnoR43 Precursor in Vitro

The comparative analysis of processing of pri-tsnoR43 using recombinant tRNase Z enzymes and nuclear extracts from cauliflower also indicates an important difference, as nuclear extracts can also accurately and efficiently process the primary precursor pri-tsnoR43. This is not the case for rAthTrzS1 and AthTrzL1 that can only process the pre-tsnoR43 but not the pri-tsnoR43 (Kruszka et al., 2003; data not shown). The kinetics of pri-tsnoR43 processing by the nuclear extract shows stepwise processing starting by rapid elimination of the 5′end leader and the appearance of an intermediate species corresponding to pre-tsnoR43 mapped in vivo. This would indicate that the first processing event on the tsnoR43 is cleavage of the 5′ tRNA leader, probably by the plant ortholog of RNAse P (Franklin et al., 1995; Arends and Schon, 1997). Eukaryotic RNase P is a conserved endonuclease producing 5′ends of tRNAs, which is the first event in processing of tRNA precursors (O'Connor and Peebles, 1991; Wolin and Matera, 1999).

Alternative Pathways for tsnoRNA Processing Initial Steps

Based on the data reported here, we propose the occurrence of alternative processing pathways for the tsnoR43 primary transcript produced by RNA polymerase III (Fig. 8). One pathway would depend on tRNase Z proteins and the tRNA processing activities. The first processing event is 5′end leader cleavage by RNase P, closely followed by processing of the 3′end U-rich extension, which characterizes all RNA polymerase III transcripts. This produces the intermediate pre-tsnoR43 that can be detected in vivo (Kruszka et al., 2003). The pre-tsnoRNA can now be the substrate of AthTrzL1 or AthTrzS1, producing both the tRNAGly and snoR43. This model is in agreement with the kinetics of processing of pri-snoR43 by nuclear extracts (Fig. 5) and the observation that AthTrzL1 or AthTrzS1 accurately cleaves the intermediate pre-tsnoR43 (Fig. 3) or pre-tsnoR43 with 3′ U-rich extension but cannot cleave the pri-tsnoR43 (Kruszka et al., 2003; data not shown). In addition, it is also in agreement with kinetics reported for processing of tRNA precursors in other eukaryotes, in which 5′ leader cleavage by RNase P is the first event and precedes 3′end processing (O'Connor and Peebles, 1991; Wolin and Matera, 1999). Processing of tsnoRNA 3′ends probably implicates the recently identified Arabidopsis La protein, which was found associated with the 3′end of the tsnoR43 precursor (Fleurdepine et al., 2007). The La protein, Lhp1p in yeast, is a conserved protein in eukaryotes that binds to the U extension and is required for processing of the 3′ends of RNA polymerase III transcripts. We propose that exonucleolytic trimming to the mature 3′end of the C/D snoRNP, controlled by La binding, produces the mature 3′snoRNA end. Indeed, this is a normal pathway for maturation of U3 snoRNA in yeast that implicates both the Lhp1p protein and exosome activities (Kufel et al., 2000). In Arabidopsis, analysis of RNA substrates affected by mutation of essential exosome subunits has confirmed its implication in processing of the plant snoRNAs (Chekanova et al., 2007).

Figure 8.

Model for processing of tsnoR43 in vivo. tsnoR43 gene transcription by RNA polymerase III produces a primary transcripts with 5′ and 3′extensions. La protein binds to 3′-terminal U stretch, and the core nucleolar proteins assemble on the precursor forming the C/D snoRNP. Two pathways can occur. Pathway 1 implicates RNAse P and tRNAse Z endonucleolytic cleavages producing the 5′ and 3′ tRNA mature ends. This liberates the snoRNA with a mature 5′end and a 3′extension that is eliminated by exonucleolytic trimming and dissociation of the La protein. The mature snoRNA ends are protected from overtrimming by C/D snoRNP proteins. Pathway 2 implicates degradation of “aberrant” tRNA by an unknown system followed by 5′ and 3′end trimming by exonucleases until mature snoRNA termini protected by C/D snoRNP proteins.

In addition, a second pathway is suggested by the dramatic accumulation of mature snoR43tag1 in mTtag1 and mANCtag1 expressed in vivo (Fig. 7B). This would be due to a distinct RNase activity that has not yet been identified directing degradation of the aberrant tRNA. One possibility is that this could be related to the rapid tRNA decay (RTD) systems. In eukaryotes, there are at least three different RTD systems that eliminate aberrant or unmodified tRNAs that can be deleterious to cell survival (Kadaba et al., 2004; Alexandrov et al., 2006; Chernyakov et al., 2008). One of them depends on the 5′-3′ exonucleases Rat1p and Xrn1p that rapidly degrade the hypomodified tRNAs from their 5′ends (Chernyakov et al., 2008). Interestingly, the yeast protein Lhp1p that binds to U-rich pre-tRNA 3′ends has recently been shown to have an important role in preventing tRNA entering the RTD pathway (Copela et al., 2008).

The RTD mechanism acting on the tsnoR43 precursor could be activated on the aberrant tRNAs associated with snoR43. In Arabidopsis, there are 12 tsnoR43 genes that are all expressed in vivo (Kruszka et al., 2003; data not shown). These genes are very similar but show sequence differences in both the tRNA and snoR43 regions. In particular, some genes, like tsnoR43.9, tsnoR43.10, or tsnoR43.11 isoforms, display tRNA sequence divergence that, while preserving the A and B promoter boxes, involve conserved nucleotides required to produce a functional tRNA structure (Kruszka et al., 2003). We have evidence that these three genes are expressed and produce their three C/D snoRNAs, which could be detected by primer extension (data not shown). Therefore, expression of these genes produces a discistronic precursor in which the C/D snoR43 is functional but the associated tRNA is aberrant and could be a primary target of the RTD pathway.

A second possibility to activate the RTD mechanism acting on tsnoR43 precursor is a distinct subnuclear localization of single tRNAs and tsnoRNAs. In yeast, and probably in animal cells, pre-tRNAs are processed in the nucleolus, while snoRNAs are processed and assembled in Cajal bodies in animals (Boulon et al., 2004) or nuclear bodies in yeast (Verheggen et al., 2002) prior to their import as mature snoRNPs into the nucleolus (Kiss, 2004; Matera et al., 2007). Thus, normal processing and modification of tRNAs could not occur in “mislocalized” pre-tRNAs associated with C/D snoR43s, therefore activating the RTD machinery. In plants, little is known on snoRNA and tRNA processing compartmentalization. Nevertheless, a study using in situ hybridization in maize (Zea mays) cells has reported the localization of polycistronic snoRNA precursor in Cajal bodies but also in the nucleolus (Shaw et al., 1998). The precise location of tRNA and snoRNA precursor processing is a major issue that we should address in the future.

The occurrence of two distinct pathways for processing the tsnoR43 precursor is not unusual. Parallel pathways for processing of small RNAs are a common theme in eukaryotes. In yeast, the processing of tRNA precursors implicates a major pathway involving the Lhp1p protein and occurring in the nucleolus and a minor pathway, which occurs in the absence of Lhp1p (Wolin and Matera, 1999).

A similar situation has been described for U3 snoRNA in which 3′end processing implicates both Lhp1p and the exosome, but in the absence of Lhp1p, 3′end processing of U3 still occurs, revealing an alternate unidentified pathway (Kufel et al., 2000).

Yet another example is the processing of intronic snoRNAs in eukaryotes that are processed by a major splicing-dependent pathway depending on debranching of the intron after pre-mRNA splicing (Kiss and Filipowicz, 1995) and a minor splicing-independent pathway that implicates direct cleavage of the pre-mRNA by endonuclease Rnt1p to create an entry site for exonucleases (Villa et al., 2000; Giorgi et al., 2001). Most interestingly, recent data show that RNase P, the tRNA processing enzyme, could be involved in processing of intronic C/D snoRNAs (Coughlin et al., 2008). Moreover, recently it was shown that RNAse P producing tRNA 5′end is recruited to transcription by RNA polymerase III in vivo, arguing for a tight link of transcription and processing of tRNA (Reiner et al., 2006). This raises the possibility of the coupling or processing of tsnoRNA and assembly of the C/D snoRNP to transcription by RNA polymerase III.

Final Steps for Processing of tsnoR43 and Assembly of the snoRNP

Whatever the diversity of primary precursors, polycistronic, monocistronic, or intronic, it has been shown that the last processing steps for all of them is trimming to both snoRNA mature ends by exonucleolytic activities. This trimming process is controlled by assembly of the four core proteins forming the C/D snoRNP on the nascent precursor that protects the snoRNA from complete degradation. Assembly of the C/D snoRNP is essential for C/D snoRNA stability in vivo, as this prevents exonuclease trimming beyond the 5′ and 3′ mature ends of the snoRNA. Recent studies in animals using acellular extracts have revealed that the C/D snoRNP assembly of intronic snoRNAs occurs on the pre-mRNA in coordination with the splicing process. A key factor in this process is a helicase-like protein that binds to the C1 splicing complex stage to direct assembly of the C/D snoRNP (Hirose et al., 2006).

Two arguments indicate that a similar system probably operates in the final steps of processing to produce the mature C/D snoR43 in plants. First, it has recently been reported that in Arabidopsis exosome mutant lines, accumulation of snoRNAs is affected (Chekanova et al., 2007). Second, we provide evidence here that processing of snoR43 is coupled to assembly of the snoRNP both in vivo and in vitro. In animals and yeast, it has been shown that assembly of the four core proteins on the C/D snoRNA initiated by the 15,5 K/Snu13p interaction with C/D kink-turn structure is essential for stability of the snoRNA in vivo, preventing exonuclease trimming beyond the 5′ and 3′ mature ends (Caffarelli et al., 1996; Samarsky et al., 1998; Watkins et al., 2002). In agreement with this model, processing of mC.tsnoR43 mutant in nuclear extracts and in planta does not affect tRNAGly processing but drastically affects accumulation of the processed mC.snoR43. Thus, box C mutation does not affect processing but interferes with assembly of the snoRNP on the mC.snoR43tag1, rendering it sensitive to exonucleolytic degradation. This is supported by the fact that purified rAthTrzL1 and AthTrzS1 correctly processed the mC.tsnoR43 mutant and accumulated both the tRNAGly and mC.snoR43tag1 to comparable levels (Fig. 3). Altogether, these data strongly suggest that in the nuclear extracts and in planta, processing of the tsnoR43 is coupled to assembly of the C/D snoRNP.

Finally, it would be interesting to investigate whether tsnoR43 processing and snoRNP assembly is also coupled to transcription of the tsnoR43 gene by RNA polymerase III.

Future Directions

Our proposal for two parallel pathways processing the tsnoR43 precursor and its coupling to assembly of the C/D snoRNP is appealing but has to be tested. Three questions are to us most important. In plants, little is known on small RNA biogenesis and nuclear compartmentalization. A first answer to our question will come from precise localization of tRNA and snoRNA by in situ hybridization. The second interesting question is the existence of an alternate pathway degrading the defective tRNAs. It would be appealing, using the tsnoRNA transgenic Arabidopsis expressing the mT or mANC mutants that highlight this second pathway, to apply a screening to identify factors controlling this pathway. The third point is to determine how assembly of C/D snoRNP occurs and how it is coupled to snoRNA precursor and transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Columbia-0) seedlings were cultivated in a growth chamber under normal daylight conditions. Cauliflowers (Brassica oleracea) were purchased at a local supermarket.

Tagged tsnoR43 Genes and Mutants

The tsnoR43.1 gene sequence extending from −85 to + 212 relative to the TIS, cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), served as template for insertion of the S and T tags and the production of different mutant constructs using the ExSite PCR-based site-directed kit (Stratagene). The double tagged tsnoR43tag12 gene has been previously reported (Kruszka et al., 2003). Tag 1 corresponds to a 16-nucleotide sequence replacing the 15 nucleotides from the antisense element of tsnoR43.1. Tag 2 corresponds to a 10-nucleotide insertion in the tRNAGly anticodon region (Kruszka et al., 2003). All mutants were produced from these tagged constructs.

Creation of Transgenic Lines, Expression-Tagged tsnoR43 Genes, and Mutants

Arabidopsis lines expressing double tagged tsnoR43tag12 have been previously described (Kruszka et al., 2003). Additional transgenic lines expressing the single tagged tsnoR43tag1 gene and the different mutants were produced by PCR-based cloning into the binary vector pBIN19 conferring resistance to kanamycin. Arabidopsis plants were transformed by Agrobacterium tumefaciens by vacuum infiltration (Bechtold and Pelletier, 1998).

RNA Extraction and Analysis

Total RNA from 10-d-old wild-type or transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings was extracted using Trizol reagents (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. All samples were subsequently subjected to DNase treatment using RQ1-DNase (Promega), followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. RNAs were resuspended in water. The RNA samples were used either for reverse transcription-PCR or primer extension as described (Barneche et al., 2000).

Primers used for detection are Psno, 5′-GAGAATGCATTGGACCCAACCAATAC-3′; PtRNA, 5′-CAGCCGGGAATCGAACCCGGGTCTG-3′; PU3, 5′-CTGTCAGACCGCCGTGCT-3′; P1, 5′-TGATATTCAGCCTCGACCTATTCTC-3′, and P2, 5′-CTGTACCGTGGTGAGCTGGCG-3′.

Preparation of Templates and Synthesis of Riboprobes

Substrates were prepared by T7 RNA polymerase transcription of PCR-amplified templates containing a T7 promoter just upstream of tsnoR43 sequences. The templates were produced by PCR amplification of the cloned tsnoR43 tagged genes and mutants using specific forward and reverse primers. The forward primer contained the T7 promoter sequence. The templates were transcribed using T7 RNA polymerase according to the manufacturer (Promega) in the presence of [α32 P]CTP or [α32P]UTP. All substrates were subsequently purified by electrophoresis on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel. The substrates were identified by autoradiography, cut out from the gel, and eluted overnight.

Preparation of Nuclear Extract from Cauliflower Meristems

This protocol was adapted from protocol for purification of RNA polymerase I holoenzyme from cauliflowers (Saez-Vasquez and Pikaard, 1997). All steps were performed at 4°C. Eighty grams of inflorescences without stalks were homogenized in 200 mL of ice-cold buffer I (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.44 m Suc, 1.25% Ficoll, 2.5% Dextran T-40, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.5 mm dithiothreitol [DTT]) supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 μg/mL of bestatin, 1 μg/mL of leupeptin, 1 μg/mL of pepstatin A, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The tissue was homogenized at maximum speed in a Waring blender using five pulses of 5 s each. The homogenate was filtered through Miracloth (Calbiochem) and centrifuged 30 min at 7,500 rpm in a JA14 rotor (Beckman). The pellet was resuspended in 20 mL of ice-cold buffer II (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 6 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 15% glycerol, and antiproteases). NaCl (1.16 g) was added, and the suspension was stirred for 10 min. Then, 400 μL of polyethylene glycol 8000 were added and stirred for an additional 20 min. Then, the suspension was centrifuged twice for 30 min at 12,000 rpm in a JA20 rotor (Beckman). The supernatant was recovered, adjusted to 100 mL with ice-cold buffer II, and precipitated for 1 h with (NH4)2SO4 at a final concentration of 0.33 g/mL final concentration. Precipitated proteins were pelleted at 12,000 rpm in a JA20 rotor, resuspended in 3 to 8 mL of buffer II, and dialyzed against 500 mL of buffer II. After dialysis, extracts were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Processing of tsnoR43 Precursors by Nuclear Extract

Substrates (25,000 cpm) or cold probes (200 ng) were incubated in 25 μL final volume, with 10 μL of nuclear extract in maturation buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 6 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 15% glycerol, and 1 mm DTT). Incubation was done at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction were stopped by addition of 275 μL of STOP solution (0.15 m NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 250 mm NaAcetate, pH 5.1, 6 mm EDTA, 0.5% SDS, and 0.1 mg/mL yeast tRNA [Invitrogen]). RNA products were extracted by phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated for analysis by electrophoresis on denaturing polyacrylamide gels.

Expression of Arabidopsis tRNAse Z Proteins in Escherichia coli

Cloning and purification of recombinant AthTrzS1 was carried out as previously described (Schiffer et al., 2002; Spath et al., 2005). The cDNA for AthTrzL1 was amplified without the first 153 nucleotides from cDNA clone RAFL07-09-G16 (RIKEN Bioresource Center) and cloned into the expression vector pET29 (Novagen). Recombinant AthTrzL1 was expressed in BL21-AI cells and purified via S-Tag according to the manufacturer's instructions (Novagen). The concentration of the recombinant proteins was determined using a Qubit fluorimeter (Invitrogen).

In Vitro Processing Assay with Recombinant tRNase Z Enzymes

Processing reactions were essentially carried out as described (Spath et al., 2005) with the following modifications. All reactions were carried in Cyto buffer (40 mm Tris, pH 8.4, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm KCl, and 2 mm DTT) in a total volume of 100 μL at 37°C for 30 min. For each reaction, 200 ng of recombinant protein were added. The reaction was stopped by phenol/chloroform extraction, and the products were separated on denaturant 8% polyacrylamide gel. Gels were exposed overnight on an x-ray film (Amersham).

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers AJ506163, At1g74700, and At1g52160.

This work was supported by the Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche et de la Technologie France (Fellowship MENRT to N.B.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Manuel Echeverría (manuel.echeverria@univ-perp.fr).

References

- Alexandrov A, Chernyakov I, Gu W, Hiley SL, Hughes TR, Grayhack EJ, Phizicky EM (2006) Rapid tRNA decay can result from lack of nonessential modifications. Mol Cell 21 87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmang C, Kufel J, Chanfreau G, Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Tollervey D (1999) Functions of the exosome in rRNA, snoRNA and snRNA synthesis. EMBO J 18 5399–5410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends S, Schon A (1997) Partial purification and characterization of nuclear ribonuclease P from wheat. Eur J Biochem 244 635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barneche F, Gaspin C, Guyot R, Echeverría M (2001) Identification of 66 box C/D snoRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana: Extensive gene duplications generated multiple isoforms predicting new ribosomal RNA 2′-O-methylation sites. J Mol Biol 311 57–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barneche F, Steinmetz F, Echeverría M (2000) Fibrillarin genes encode both a conserved nucleolar protein and a novel small nucleolar RNA involved in ribosomal RNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 275 27212–27220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Pelletier G (1998) In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol Biol 82 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulon S, Verheggen C, Jady BE, Girard C, Pescia C, Paul C, Ospina JK, Kiss T, Matera AG, Bordonne R, et al (2004) PHAX and CRM1 are required sequentially to transport U3 snoRNA to nucleoli. Mol Cell 16 777–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Echeverría M, Qu LH (2003) Plant snoRNAs: functional evolution and new modes of gene expression. Trends Plant Sci 8 42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffarelli E, Fatica A, Prislei S, De Gregorio E, Fragapane P, Bozzoni I (1996) Processing of the intron-encoded U16 and U18 snoRNAs: The conserved C and D boxes control both the processing reaction and the stability of the mature snoRNA. EMBO J 15 1121–1131 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bocian E, Barbezier N, Echeverría M, Forner J, Binder S, Marchfelder A (2009) Arabidopsis encodes four tRNase Z enzymes. Plant Physiol 150 1494–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekanova JA, Gregory BD, Reverdatto SV, Chen H, Kumar R, Hooker T, Yazaki J, Li P, Skiba N, Peng Q, et al (2007) Genome-wide high-resolution mapping of exosome substrates reveals hidden features in the Arabidopsis transcriptome. Cell 131 1340–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyakov I, Whipple JM, Kotelawala L, Grayhack EJ, Phizicky EM (2008) Degradation of several hypomodified mature tRNA species in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated by Met22 and the 5′-3′ exonucleases Rat1 and Xrn1. Genes Dev 22 1369–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comella P, Pontvianne F, Lahmy S, Vignols F, Barbezier N, Debures A, Jobet E, Brugidou E, Echeverría M, Saez-Vasquez J (2008) Characterization of a ribonuclease III-like protein required for cleavage of the pre-rRNA in the 3′ETS in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res 36 1163–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copela LA, Fernandez CF, Sherrer RL, Wolin SL (2008) Competition between the Rex1 exonuclease and the La protein affects both Trf4p-mediated RNA quality control and pre-tRNA maturation. RNA 14 1214–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin DJ, Pleiss JA, Walker SC, Whitworth GB, Engelke DR (2008) Genome-wide search for yeast RNase P substrates reveals role in maturation of intron-encoded box C/D small nucleolar RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105 12218–12223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W, Pogacic V (2002) Biogenesis of small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 14 319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleurdepine S, Deragon JM, Devic M, Guilleminot J, Bousquet-Antonelli C (2007) A bona fide La protein is required for embryogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res 35 3306–3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin SE, Zwick MG, Johnson JD (1995) Characterization and partial purification of two pre-tRNA 5′-processing activities from Daucus carrota (carrot) suspension cells. Plant J 7 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi C, Fatica A, Nagel R, Bozzoni I (2001) Release of U18 snoRNA from its host intron requires interaction of Nop1p with the Rnt1p endonuclease. EMBO J 20 6856–6865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T, Ideue T, Nagai M, Hagiwara M, Shu MD, Steitz JA (2006) A spliceosomal intron binding protein, IBP160, links position-dependent assembly of intron-encoded box C/D snoRNP to pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell 23 673–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaba S, Krueger A, Trice T, Krecic AM, Hinnebusch AG, Anderson J (2004) Nuclear surveillance and degradation of hypomodified initiator tRNAMet in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev 18 1227–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss T (2004) Biogenesis of small nuclear RNPs. J Cell Sci 117 5949–5951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss T, Filipowicz W (1995) Exonucleolytic processing of small nucleolar RNAs from pre-mRNA introns. Genes Dev 9 1411–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszka K, Barneche F, Guyot R, Ailhas J, Meneau I, Schiffer S, Marchfelder A, Echeverría M (2003) Plant dicistronic tRNA-snoRNA genes: a new mode of expression of the small nucleolar RNAs processed by RNase Z. EMBO J 22 621–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufel J, Allmang C, Chanfreau G, Petfalski E, Lafontaine DL, Tollervey D (2000) Precursors to the U3 small nucleolar RNA lack small nucleolar RNP proteins but are stabilized by La binding. Mol Cell Biol 20 5415–5424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera AG, Terns RM, Terns MP (2007) Non-coding RNAs: lessons from the small nuclear and small nucleolar RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor JP, Peebles CL (1991) In vivo pre-tRNA processing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 11 425–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petfalski E, Dandekar T, Henry Y, Tollervey D (1998) Processing of the precursors to small nucleolar RNAs and rRNAs requires common components. Mol Cell Biol 18 1181–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner R, Ben-Asouli Y, Krilovetzky I, Jarrous N (2006) A role for the catalytic ribonucleoprotein RNase P in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev 20 1621–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez-Vasquez J, Pikaard CS (1997) Extensive purification of a putative RNA polymerase I holoenzyme from plants that accurately initiates rRNA gene transcription in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94 11869–11874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarsky DA, Fournier MJ, Singer RH, Bertrand E (1998) The snoRNA box C/D motif directs nucleolar targeting and also couples snoRNA synthesis and localization. EMBO J 17 3747–3757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer S, Helm M, Theobald-Dietrich A, Giege R, Marchfelder A (2001) The plant tRNA 3′ processing enzyme has a broad substrate spectrum. Biochemistry 40 8264–8272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer S, Rosch S, Marchfelder A (2002) Assigning a function to a conserved group of proteins: the tRNA 3′-processing enzymes. EMBO J 21 2769–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Beven AF, Leader DJ, Brown JW (1998) Localisation and processing from polycistronic precursor of novel snoRNAs in maize. J Cell Sci 111 2121–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spath B, Canino G, Marchfelder A (2007) tRNase Z: The end is not in sight. Cell Mol Life Sci 64 2404–2412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spath B, Kirchner S, Vogel A, Schubert S, Meinlschmidt P, Aymanns S, Nezzar J, Marchfelder A (2005) Analysis of the functional modules of the tRNA 3′ endonuclease (tRNase Z). J Biol Chem 280 35440–35447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheggen C, Lafontaine DL, Samarsky D, Mouaikel J, Blanchard JM, Bordonne R, Bertrand E (2002) Mammalian and yeast U3 snoRNPs are matured in specific and related nuclear compartments. EMBO J 21 2736–2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa T, Ceradini F, Bozzoni I (2000) Identification of a novel element required for processing of intron-encoded box C/D small nucleolar RNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 20 1311–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins NJ, Dickmanns A, Luhrmann R (2002) Conserved stem II of the box C/D motif is essential for nucleolar localization and is required, along with the 15.5K protein, for the hierarchical assembly of the box C/D snoRNP. Mol Cell Biol 22 8342–8352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SL, Matera AG (1999) The trials and travels of tRNA. Genes Dev 13 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukawa Y, Sugita M, Choisne N, Small I, Sugiura M (2000) The TATA motif, the CAA motif and the poly(T) transcription termination motif are all important for transcription re-initiation on plant tRNA genes. Plant J 22 439–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]