Abstract

Opisthorchiasis caused by Opisthorchis viverrini (O. viverrini) remains a major public health problem in many parts of Southeast Asia including Thailand, Lao PDR, Vietnam and Cambodia. The infection is associated with a number of hepatobiliary diseases, including cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, hepatomegaly, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis and cholangiocarcinoma. The liver fluke infection was induced by eating raw or uncooked fish products that is the tradition and popular in the northeastern and northern region, particularly in rural areas of Thailand. Health education programs to prevent and control opisthorchiasis are still required in high-risk areas.

Keywords: Opisthorchis viverrini, Opisthorchiasis, Status, Thailand

INTRODUCTION

Liver flukes are platyhelminth parasites of the class trematoda, and Opisthorchis viverrini is a member of the family Opisthorchiidae. Opisthorchis spp. is a prevalent human parasite particularly in the Far East and South East Asia. O. viverrini is highly prevalent in Thailand and Laos while C. sinensis is endemic in south China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan, O. felineus is the prominent fluke in Eastern Europe[1]. In Thailand O. viverrini is the only parasite of opisthorchiasis, the first case of opisthorchiasis was reported in 1911 by Leiper from the autopsy of a corpse in Chiang Mai. Later on Sadun in 1953, Harinasuta and Vajjarasthira in 1961, and Wykoff in 1965 had demonstrated a complete life cycle of O. viverrini [2–4]. O. viverrini has a complicated life cycle with 2 intermediate hosts, a freshwater snail (Bithynia goniompharus, B. funiculata and B. siamensis) is the first intermediate host[4,5], and a freshwater fish (Cyclocheilichthys spp., Puntius spp., Hampala dispa) is the second intermediate host where the metacercariae habitat in the muscles or under the scales. Cats, dogs, and various fish-eating mammals including humans are the definitive host[6]. More than 7 million were infected by O. viverrini that were recorded by various investigators. Humans have become infected by ingesting undercooked fish containing infective metacercariae, this figure shows the tradition of eating raw or uncooked fish products as the main reason that liver flukes are a problem in Thailand. This is very popular in the northeastern and northern region particularly in rural areas. This infection is associated with a number of benign hepatobiliary diseases, including cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, hepatomegaly, cholecystitis and biliary lithiasis[7]. Both experimental and epidemiological evidence implicate liver fluke infestation in the etiology of bile duct cancer, i.e. cholangiocarcinoma[1,8]. In Thailand, opisthorchiasis is still a serious problem, especially in the northeast and north region. Therefore, this article investigates the distribution of the disease of the people with an emphasis on the north, north-east, central and south regions of Thailand.

HISTORY OF OPISTHORCHIASIS IN THAILAND

Fish-borne trematode in Thailand, O. viverrini was first described in the post-mortem examination of two prisoners from a jail in Chiengmai, northern Thailand, in 1911 by Leiper who obtained specimens from Kerr. Kerr reported that 17% of 230 adult male prisoners examined in a prison in Chiengmai were infected with O. felineus[9]. In 1927, Prommas identified the worms found at an autopsy of a 17-year-old Thai male residing in Roi-et, northeast Thailand, as O. felineus[10]. The liver fluke infection in Thailand was caused by O. viverrini, not by O. felineus[2], and Wykoff et al confirmed this later in 1965[4]. Since then, cases of opisthorchiasis were reported each year. O. viverrini is still prevalent and a serious health problem in some parts of Thailand, therefore, the health education promotion is still required.

SOURCE OF THAI HUMAN INFECTION

Three types of preparations contain uncooked, small and medium-sized, fish: (1) Koi pla, eaten soon after preparation; (2) Moderately fermented pla som; stored for a few days to weeks; and, (3) Pla ra extensively fermented, highly salted fish, stored for at least 2-3 mo[2,11]. The consumption frequencies of koi pla in some communities every week was approximately 80%[12]. In the northeasterners who have eaten koi pla, studies found the highest prevalence of liver fluke infection[13,14]. The frequencies of koi pla consumption have declined and are generally confined to special social occasions, while other under-cooked fish preparations like pla som and other moderately preserved fish are generally eaten several times a week[11]. Pla ra and jaewbhong, fully preserved fish, is an important staple and consumed daily by 60%-98% of northeasterners and lowland Laotians[12,15]. At present, the patients still show that Koi pla is probably the most infective, followed by fish preserved for < 7 d, then pla ra and jaewbhong, in which viable metacercaria are rare [11].

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF OPISTHORCHIASIS IN THAILAND

The Helminthiasis control program started in 1950 included opisthorchiasis control in some high risk areas[16]. The main liver fluke control strategies comprise of three interrelated approaches, namely stool examinations and treatment of positive cases with praziquantel for eliminating human host reservoir; health education for a promotion of cooked fish consumption to prevent infection, and the improvement of hygienic defecation for the interruption of disease transmission[16]. In Thailand, more than 7 million people were infected with O. viverrini, estimated by various investigators[2,4,17,18]. Prevalence rates of O. viverrini in the northeast and the north were, 29.8% and 10.3% respectively[19]. A health survey was carried out among residents of 33 villages under the Phitsanulok Irrigation Project Area, Nan River Basin, and northern Thailand. The prevalence of O. viverrini was 20%, the significant endemic diseases as potential health problems in this water resources development[20]. A study of the prevalence and intensity of O. viverrini in relation to morbidity as determined by standard medical examination was carried out in Nong Ranya, a small village containing 309 people in northeastern Thailand. O. viverrini infection was determined with an overall prevalence of 94%, and reaching 100% prevalence in most age groups above the age of 10 years. Peak intensity in both males and females occurred at age 40 and above[21].

In 1980-1981 the prevalence in the north, northeast, centre and south of Thailand was 5.59, 34.60, 6.34, and 0.01%, respectively, with an overall prevalence of 14% or 7 million people[22]. Incidence, measured as the proportion of persons whose stools become positive within one year, was studied in endemic O. viverrini, in a northeastern Thai village over a two-year period. Incidence was higher in males than in females, especially in children under five years of age. It was at least 47% overall in the first year of the study, but declined to below 20% per year in the second[23]. The prevalence and intensity of O. viverrini infection were investigated among 559 patients who were born in, and had lived all their lives in, either the rural or urban northeastern Thailand. 344 (79.4%) of 433 rural dwellers were infected compared with only 69 (54.8%) of 126 urban dwellers. Infection due to O. viverrini appears to be mainly a rural problem strongly associated with the habit and frequency of eating koi-pla[24]. Tesana et al reported the prevalence of O. viverrini infection in the villages on the banks of rivers and those far from the rivers in Loei and Nong Khai Provinces, northeast Thailand. Most of the people examined in the present study were agriculturalists. The overall prevalence of O. viverrini infection was 41.3%. The prevalence of infection in males and in females in the villages far from the rivers were 52.6% and 51.7%, respectively, while the percent of people in the villages on the banks with infection were 27.9% and 21.7%, respectively. Prevalence of infection among the people residing far from the rivers was higher than those residing on the banks. This was observed despite the higher recording of raw fish consumption in villages on the banks. Infection level increased sharply in the age-group 6-10 years among people residing far from the rivers. High prevalence of infection was observed in age groups from 11 to 50 years[25].

The patterns of infection with O. viverrini within a human community assessed by egg count were observed. A striking 81.5% of the total Opisthorchis population and 74% of the total egg output were expelled by the most heavily infected 10% of the humans sampled[26]. Meanwhile, Sithithaworn et al[27] investigated O. viverrini infection in 181 accident subjects in northeast Thailand. The prevalence increased rapidly with age and reached a plateau at 70%-80% in adults. The overall prevalence estimated by faecal examination was 69.2%, while that measured by worm recovery was 79.2%. In 1991, the survey of O. viverrini in 14 villages in Nakhon-Phanom province, Northeast, Thailand was conducted. Overall prevalence of O. viverrini infection was 66.4% in a total population of 2412 individuals. The prevalence was 18.5% in children under 5 years, 38.9% in those aged 5-9 years, and ranged from 64.9% to 82.2% in the age group above 10 years. The intensity of O. viverrini infection increased with age. The mean faecal egg output was highest in the 30-34 years age group and remained relatively constant in the older aged group. In all age groups the prevalence and intensity of infection in both men and women were similar. The population was divided according to the presence and intensity of infection as follows, 33% were uninfected, 59% had light infections (less than 1000 eggs per g of faeces; EPG), 7% had moderate infections (1000-10 000 EPG), and 1% had heavy (greater than 10 000 EPG)[28]. Therafter, Peng et al[29] have been reported that all 1364 Thai labourers in Taiwan were examined for stool samples and 18.0% were found to be infected, with O. viverrini at 7.0%. The prevalence was highest among the 21-25 age group (24.8%). The finding that parasitic infections are prevalent among Thai labourers demonstrates the need for control measures in foreign labourers in Taiwan. Meanwhile, stool samples from 93 Thais working in Israel were examined for the presence of parasites. The overall prevalence of infection by 1 or more species was 74%. O. viverrini and hookworm were the most prevalent parasites (51.6% and 44.1%, respectively)[30]. In 1994, Radomyos et al[31] examined O. viverrini infection in 681 residents from 16 provinces in northeast Thailand. The prevalence of O. viverrini in this group was 92.4%. In the same period, region wide assessments in 1994 were conducted. The prevalence of opisthorchiasis was 18.5% with a large variation in infection rate[32].

In 1998, 431 residents from 16 provinces in northern Thailand who had previously been found positive for O. viverrini or O. viverrini-like eggs were given praziquantel 40 mg/kg. The stool was collected for 4 to 6 times and examined for adult worms. The prevalence of O. viverrini in this group was 11.6%[33]. Waree et al[34] survey the parasitic infection from 584 stool specimens in Noen Maprang, Phitsanulok Province during October 1999 to March 2000. It was found that the prevalence of O. viverrini infection was 10.78%. During October to November 2000, faecal samples were collected from study participants from 332 rural northeast Thais, O. viverrini was 14.2% and ranging from 8.6-19.4[11]. While Wiwanikit et al[35] reported the prevalence of O. viverrini was 8.7% (16 from 183 cases) in Sawasdee Village in the Nam Som District, Udonthani Province in northeastern Thailand in 2001. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections at 8 schools in Bo Klau district and 4 schools in Chalerm Prakiet district, Nan Province, in January and February, 2001. A total of 1010 fecal samples were examined and found O. viverrini was 1.7%[36]. Of 2213 Thai workers who visited the Out-patients Department of the King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital between September 2000 and January 2001 the prevalence of O. viverrini was 28.9%[37]. Rhongbutsri et al reported the liver fluke infections, O. viverrini (11.1% from 395 samples), the most common in the old age group (51 years and up) in Ban Khok Yai Village, Khon Kaen Province, northeast Thailand[38]. The nationwide survey was reported in 2001 by Jongsuksantigul and Imsomboon, the prevalence of opisthorchiasis in the north, northeast, central and south, 19.3%, 15.7%, 3.8% and 0% respectively[16]. A small scale survey in Aranyaprathet District, Sa Kaeo Province, eastern Thailand, was conducted in January 2004. Of the 545 stool samples collected and examined, 261 (47.9%) contained small-sized eggsresembling O. viverrini eggs[39]. Of 24 723 participants in Khon Kaen Provine of northeast Thailand, 18 393 aged 35-69 years were tested for O. viverrini infection, by examining stools for the presence of eggs. The average crude prevalence of O. viverrini infection in the sample subjects was 24.5%, ranging from 2.1% to 70.8%[40]. Recently, a total of 479 stool specimens were collected from rural communities of Ubon Ratchathani Province, Thailand. The prevalence of O. viverrini was 14.8%, while the same research group reported an epidemiological survey was conducted in Khon Kaen Province involving 1124 stool samples using the modified Kato technique. The greatest frequency was O. viverrini at 32.0% while the second highest was Sarcocystis spp at 8.0% [41].

Report cases of opisthorchiasis per 100 000 populations by year, Thailand

The mortality rate was reported by the Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand during 2001-2006. Morbidity rate of opisthorchiasis cases decreased from 1.74 in 2001 to 0.79 in 2002. In 2003, the morbidity rate increased to 1.58, but then, the ratio slightly decreased from 1.33 in 2004 to 0.64 in 2005. In 2006, the morbidity rate slightly increased to 0.73 per 100 000 populations (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Reported cases of opisthorchiasis in Thailand[43]. A: Reported cases of opisthorchiasis per 100 000 populations, 2001-2006; B: Reported cases of opisthorchiasis by month, 2002-2006; C: Reported cases of opisthorchiasis per 100 000 populations by age group, 2003-2006; D: Reported cases of opisthorchiasis by sex, 2003-2006; E: Reported cases of opisthorchiasis by occupation, 2003-2006; F: Reported cases of opisthorchiasis by region, 2003-2006.

Report cases of opisthorchiasis by month

During 2002-2006, the reported cases of opisthorchiasis by month were presented by the Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. In 2002, the highest number of cases was in January, and the second was in March. Other months were a few cases of opisthorchiasis during the year. In 2003, the highest number of cases was reported, more than the other years from 2002 to 2006. The pattern of reported cases at each month, February was the highest and second was September. February in 2004 was the highest of reported cases followed by September and July. Meanwhile, in 2005 was found the highest opisthorchiasis cases in September, however, the second was February. Recently, in the reported cases February was higher than other months in 2006 (Figure 1B).

Report cases of opisthorchiasis by age-group, sex and occupation

Infection with O. viverrini begins at a very early age (0-4 age group, 0.64 per 100 000 population); the prevalence of infection rises rapidly with age up to adult hood and remains relatively high, thereafter, the relationship of prevalence to age being a function of “Koi pla” consumption. The intensity of infection (faecal egg output) in both males and females rises steadily in early life, reaches highest in the 55-64 years age group (2.21 per populations), the reported cases were found common in 35-44, 45-54, 55-64 and 65+, 1.48, 2.06, 2.21 and 1.43 per population, respectively (Figure 1C). This figure showed similarity with a previous study, however, Upatham et al reported the highest in the 35-44 years age[14,21]. Loaharanu and Sornmani estimated the total direct cost of the infected work force (between the age of 15 and 60-year-old) in northeast Thailand to be Baht 2115 million per annum (wage loss = Baht 1620 million; direct cost of medical care = Baht 495 million)[42]. Meanwhile, the more frequently reported cases were in males more than females, in a ratio of 1:1.11 (Figure 1D). The opisthorchiasis cases reported by occupation found that agriculture was the most highest of cases than other. It is very surprising that the student group was the third of reported cases during 2003-2006 (Figure 1E). This is a very serious public health problem, health education should be conducted through communication and education.

Report cases of opisthorchiasis by region

Nationwide survey was reported by[16]. The prevalence of O. viverrini infection in the north (19.3%), the northeast (15.7%), central (3.8%) and the south (0%) was recently reported. However, from 2003-2006, the reported cases of opisthorchiasis by region were presented by the Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand found that the northeast region was the highest of frequency than other regions. The second was the north, while the central region has shown a few opisthorchiasis cases. In the southern region, no cases were reported during 2003 to 2006 (Figure 1F). Although, the reported cases of opisthorchiasis in the northern region were less than the northeast region in 2005-2006, the morbidity rate was higher than other regions. In 2006, the morbidity rate of opisthorchiasis cases in Thailand was 0.73 per population and in the north, northeast, central and south region was 1.45, 1.34, 0.00 and 0.00 respectively.

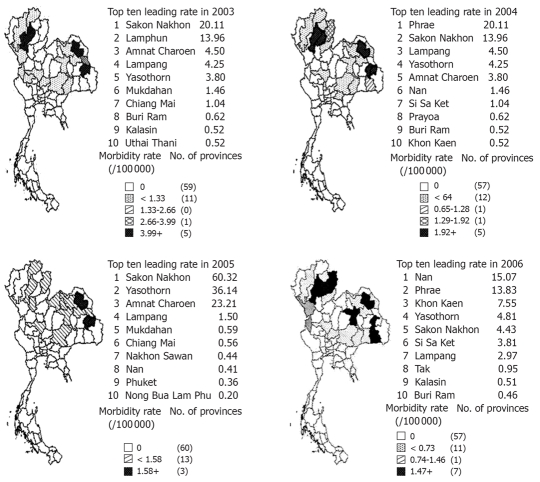

Report of cases of opisthorchiasis by province

It has also been shown that the prevalence and intensity of infection are greater among rural dwellers than their urban counterparts, an observation strongly associated with the habit and frequency of eating “Koi pla”[24]. This tradition is commonly found in the northeast and north region of Thailand, therefore, provinces located in 2 regions are also frequently reported with opisthorchiasis cases. The morbidity rate was identified into top ten leading rates during 2003-2006, Sakon Nakhon, Yasothon, Lamphun, Amnat Charoen, Lampang, Mukdahan, Chiang Mai, Buri Ram, Kalasin, Uthai Thani, Phrae, Nan, Si Sa Ket, Phayao, Khon Kaen, Chiang Rai, Nakhon Sawan, Phuket, Nong Bua Lam Phu, Phrae and Tak. From 2003-2006, Sakon Nakhon and Yasothon were the provinces that found the opisthorchiasis cases every year (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reported cases of opisthorchiasis per 100 000 populations by province in Thailand, 2003-2006[43].

CONCLUSION

O. viverrini is a medically important food borne trematode in Thailand including some parts of Southeast Asia countries. The opisthorchiasis have been studied for more than 50 years; the infection is associated with cholangiocarcinoma and other hepatobiliary diseases. This review article emphasizes the passive surveillance data that was reviewed by the Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. The epidemiology is found in some rural areas that the tradition of eating raw or uncooked fish products was the main reason for infection. The northeastern and northern regions of Thailand are still a major public problem in the high-risk areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Lisa Vandemark for assistance with English-language presentation of the manuscript. Special thanks Professor Reinhard Buettner for a valuable suggestion and comments on the manuscript.

Peer reviewer: Reinhard Buettner, Professor, Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Bonn, Sigmund-Freud-Str. 25, D-53127 Bonn, Germany

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Liu Y

References

- 1.IARC. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7-14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.SaduN EH. Studies on Opisthorchis viverrini in Thailand. Am J Hyg. 1955;62:81–115. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harinasuta C, Vajrasthira S. Opisthorchiasis in Thailand. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1960;54:100–105. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1960.11685962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wykoff DE, Harinasuta C, Juttijudata P, Winn MM. Opisthorchis viverrini in THAILAND--The life cycle and comparison with O. felineus. J Parasitol. 1965;51:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt RAM. The non-marine aquatic mollusca of Thailand. Arch Moll. 1974;51:105; 1–423. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaewkes S. Taxonomy and biology of liver flukes. Acta Trop. 2003;88:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harinasuta T, Riganti M, Bunnag D. Opisthorchis viverrini infection: pathogenesis and clinical features. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:1167–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vatanasapt V, Sriamporn S, Kamsa-ard S, Suwanrungruang K, Pengsaa P, Charoensiri DJ, Chaiyakum J, Pesee M. Cancer survival in Khon Kaen, Thailand. IARC Sci Publ. 1998:123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr AFG. Intestinal parasites in northern Siam. Trans Soc Trop Med. 1916;9:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prommas C. Report of case of Opisthorchis felineus in Siam. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1927;21:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sithithaworn P, Haswell-Elkins M. Epidemiology of Opisthorchis viverrini. Acta Trop. 2003;88:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Migasena S, Egoramaiphol S, Tungtrongchitr R, Migasena P. Study on serum bile acids in opisthorchiasis in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 1983;66:464–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurathong S, Lerdverasirikul P, Wongpaitoon V, Pramool-sinsap C, Kanjanapitak A, Varavithya W, Phuapradit P, Bunyaratvej S, Upatham ES, Brockelman WY. Opisthorchis viverrini infection and cholangiocarcinoma. A prospective, case-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:151–156. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upatham ES, Viyanant V, Kurathong S, Rojborwonwitaya J, Brockelman WY, Ardsungnoen S, Lee P, Vajrasthira S. Relationship between prevalence and intensity of Opisthorchis viverrini infection, and clinical symptoms and signs in a rural community in north-east Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 1984;62:451–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Changbumrung S, Migasena P, Supawan V, Juttijudata P, Buavatana T. Serum protease inhibitors in opisthorchiasis, hepatoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and other liver diseases. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1988;19:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jongsuksuntigul P, Imsomboon T. Opisthorchiasis control in Thailand. Acta Trop. 2003;88:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harinasuta C, Vajrasthira S. Study on opisthorchiasis in Thailand: survey of the incidence of opisthorchiasis in patients of fifteen hospitals in the northeast. In: Proceeding of the 9th Pacific Science Congress; Bangkok; 1962. pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preuksaraj S, Jeeradit C, Satilthai A, Sidofrusmi T, Kijwanee S. reuksaraj. Prevalence and intensity of intestinal helminthiasis in rural Thailand 1980–1981. Con Dis J. 1982;8:221–269. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vajrasthira S, Harinasuta C. Study on helminthic infections in Thailand. Incidence, distribution and epidemiology of seven common intestinal helminths. J Med Assoc Thai. 1957;40:309–340. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunnag T, Sornmani S, Impand P, Harinasuta C. Potential health hazards of the water resources development: a health survey in the Phitsanulok Irrigation Project, Nan River Basin, Northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1980;11:559–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upatham ES, Viyanant V, Kurathong S, Brockelman WY, Menaruchi A, Saowakontha S, Intarakhao C, Vajrasthira S, Warren KS. Morbidity in relation to intensity of infection in Opisthorchiasis viverrini: study of a community in Khon Kaen, Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:1156–1163. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harinasuta C, Harinasuta T. Opisthorchis viverrini: life cycle, intermediate hosts, transmission to man and geographical distribution in Thailand. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:1164–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Upatham ES, Brockelman WY, Viyanant V, Lee P, Kaengraeng R, Prayoonwiwat B. Incidence of endemic Opisthorchis viverrini infection in a village in northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985;34:903–906. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurathong S, Lerdverasirikul P, Wongpaitoon V, Pramool-sinsap C, Upatham ES. Opisthorchis viverrini infection in rural and urban communities in northeast Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:411–414. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tesana S, Sithithaworn P, Prasongwatana J, Kaewkes S, Pipitgool V, Pientong C. Influence of water current on the distribution of Opisthorchis viverrini infection in northeastern villages of Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991;22:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haswell-Elkins MR, Sithithaworn P, Mairiang E, Elkins DB, Wongratanacheewin S, Kaewkes S, Mairiang P. Immune responsiveness and parasite-specific antibody levels in human hepatobiliary disease associated with Opisthorchis viverrini infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb08151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sithithaworn P, Tesana S, Pipitgool V, Kaewkes S, Pairojkul C, Sripa B, Paupairoj A, Thaiklar K. Relationship between faecal egg count and worm burden of Opisthorchis viverrini in human autopsy cases. Parasitology. 1991;102:277–281. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000062594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maleewong W, Intapan P, Wongwajana S, Sitthithaworn P, Pipitgool V, Wongkham C, Daenseegaew W. Prevalence and intensity of Opisthorchis viverrini in rural community near the Mekong River on the Thai-Laos border in northeast Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 1992;75:231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng HW, Chao HL, Fan PC. Imported Opisthorchis viverrini and parasite infections from Thai labourers in Taiwan. J Helminthol. 1993;67:102–106. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00012967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg Z, Giladi L, Bashary A, Zahavi H. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among Thais in Israel. Harefuah. 1994;126:507–509, 563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radomyos P, Radomyos B, Tungtrongchitr A. Multi-infection with helminths in adults from northeast Thailand as determined by post-treatment fecal examination of adult worms. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:133–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jongsuksuntigul P, Imsomboon T. The impact of a decade long opisthorchiasis control program in northeastern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28:551–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radomyos B, Wongsaroj T, Wilairatana P, Radomyos P, Praevanich R, Meesomboon V, Jongsuksuntikul P. Opisthorchiasis and intestinal fluke infections in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waree P, Polseela P, Pannarunothai S, Pipitgool V. The present situation of paragonimiasis in endemic area in Phitsanulok Province. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32 Suppl 2:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiwanitkit V, Suwansaksri J, Chaiyakhun Y. High prevalence of Fasciolopsis buski in an endemic area of liver fluke infection in Thailand. MedGenMed. 2002;4:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waikagul J, Dekumyoy P, Chaichana K, Thairungroje Anantapruti M, Komalamisra C, Kitikoon V. Serodiagnosis of human opisthorchiasis using cocktail and electroeluted Bithynia snail antigens. Parasitol Int. 2002;51:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(02)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saksirisampant W, Wiwanitkit V, Akrabovorn P, Nuchprayoon S. Parasitic infections in Thai workers that pursue overseas employment: the need for a screening program. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33 Suppl 3:110–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhongbutsri P, Kitvatanachai S. Survey of the Fluke Infection Rate in Ban Khok Yai Village, Khon Kaen, Thailand. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;25:76–78. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muennoo C, Waikagul J, Maipanich W, Watthanakulpanich D, Sanguankiat S, Pubampen S, Nuamtanong S, Yoonuan T. Liver Fluke and Minute Intestinal Fluke Infection in Sa Kaeo and Nan Provinces, Thailand. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;28:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sriamporn S, Pisani P, Pipitgool V, Suwanrungruang K, Kamsa-ard S, Parkin DM. Prevalence of Opisthorchis viverrini infection and incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in Khon Kaen, Northeast Thailand. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:588–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tungtrongchitr A, Chiworaporn C, Praewanich R, Radomyos P, Boitano JJ. The potential usefulness of the modified Kato thick smear technique in the detection of intestinal sarcocystosis during field surveys. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38:232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loaharanu P, Sornmani S. Preliminary estimates of economic impact of liver fluke infection in Thailand and the feasibility of irradiation as a control measure. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991;22 Suppl:384–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Diseas Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. Reported the surveillance of liver fluke. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance (Report 506) 2001-2006. Available from: URL: http://203.157.15.4/surdata/ [Google Scholar]