Abstract

AIM: To analyze the efficacy of routine intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) as a guide for understanding biliary tract anatomy, to avoid bile duct injury (BDI) after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), as well as any burden during the learning period.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis was performed using 644 consecutive patients who underwent LC from 1991 to 2006. An educational program with the use of IOUS as an operative guide has been used in 276 cases since 1998.

RESULTS: IOUS was highly feasible even in patients with high-grade cholecystitis. No BDI was observed after the introduction of the educational program, despite 72% of operations being performed by inexperienced surgeons. Incidences of other morbidity, mortality, and late complications were comparable before and after the introduction of routine IOUS. However, the operation time was significantly extended after the educational program began (P < 0.001), and the grade of laparoscopic cholecystitis (P = 0.002), use of IOUS (P = 0.01), and the experience of the surgeons (P = 0.05) were significant factors for extending the length of operation.

CONCLUSION: IOUS during LC was found to be a highly feasible modality, which provided accurate, real-time information about the biliary structures. The educational program using IOUS is expected to minimize the incidence of BDI following LC, especially when performed by less-skilled surgeons.

Keywords: Intraoperative ultrasound, Cholecystolithiasis, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Bile duct injury, Education program

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is widely accepted as a standard treatment for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. However, the incidence of complications in the form of bile duct injury (BDI) is high, and it has been reported to be as high as twice the normal rate[1,2]. Once such BDI occurs, it increases postoperative morbidity[3] and mortality[4,5], and decreases long-term quality of life[6], which consequently results in a high number of lawsuits[7]; therefore, it should be prevented if at all possible[1,8]. It is necessary to have a sufficient understanding of the biliary anatomy to prevent BDI[1], yet the damage is often caused by misidentification of the bile duct and other normal structures[9–11]. Therefore, the inappropriateness of a procedure is often not discovered until the bile duct has already been injured.

To prevent BDI, intraoperative guidance by intraoperative cholangiography and intraoperative ultrasonography (IOUS) has been suggested. Although cholangiography is effective in diagnosing biliary tract injury, it remains controversial as to whether the routine implementation of cholangiography will prevent BDI[2,12–15]. Moreover, intraoperative cholangiography requires a significant amount of hospital treatment to prevent BDI[16]. On the other hand, IOUS requires a shorter examination time[17–19], is safe without incurring radiation exposure, and is minimally invasive[18,20]. It has been reported that IOUS allows for visualization equal to or better than that of cholangiography[17,20–23] in the case of biliary anatomy and diagnosis of bile duct stones. However, there have been few studies that have investigated whether the routine implementation of IOUS decreases BDI during LC[24]. Moreover, a sufficient learning period is considered necessary for IOUS[25,26]. However, there have been very few studies on visualization of biliary anatomy, diagnostic performance, or changes in decision-making during the learning period in less-skilled surgeons, or on the extension of operation time caused by the introduction of IOUS.

Therefore, in this study, IOUS was routinely introduced to an educational program for laparoscopic biliary surgery, to analyze its efficacy in helping surgeons avoid biliary tract injury and other complications, and to analyze the extension of operation time during the learning curve.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Among 664 patients who underwent laparoscopic biliary surgery at the Hirosaki University Hospital from March 1991 to December 2006, 644 were targeted after excluding 20 in whom surgery other than biliary tract surgery was performed. Senior surgeons with experience in laparoscopic surgery in at least 100 cases were in charge from 1991 to 1997 as a rule, but the educational program for laparoscopic biliary surgery began in 1998 to teach young surgeons with experience of less than 30 LCs. Furthermore, IOUS using a linear probe was introduced in October 1992 for the purpose of making an intraoperative diagnosis and as a guide for surgical procedures at the start of a cholecystectomy. IOUS was used on a sporadic basis at first, but it became routine at the start of the educational program in 1998.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed preoperatively on selective cases with icterus or a high level of serum transaminases. Moreover, intraoperative cholangiography was selectively adopted in the earlier period when bile duct stones were suspected by preoperative examination, and was selectively performed in the later period when bile duct stones or variations in biliary distribution were suspected via IOUS.

We included 368 cases before the introduction of the educational program and 276 cases after its introduction (Table 1). There was no gender difference. Although the age was significantly higher in the latter term, all cases underwent elective surgery after sufficient assessment of their general health status. There was no significant difference in the indicated disorders for surgery, and cholecystolithiasis accounted for at least 80% of the cases. The rate of coexisting biliary infection and the diameter of the bile duct measured in the preoperative examination were comparable between the two periods.

Table 1.

Patient demographic data

| Before routine IOUS (1991-1997) | Routine IOUS (1998-2006) | P | |

| Patient number (n) | 368 | 276 | |

| Male/Female | 140/228 | 107/169 | 0.85 |

| Age (yr) | 53.3 ± 13.9 | 57.1 ± 13.6 | 0.004 |

| Operative indications, n (%) | 0.73 | ||

| Cholecystolithiasis | 296 (80.4) | 228 (82.6) | |

| Cholecystocholedocholithiasis | 39 (10.6) | 23 (10.5) | |

| Choledocholithiasis | 7 (1.9) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Gallbladder polyp | 22 (6.0) | 11 (4.0) | |

| Others1 | 4 (1.1) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Symptomatic gallstones, n (%) | 284 (77.2) | 220 (79.7) | 0.44 |

| Acute cholecystitis/cholangitis, n (%) | 42 (11.4) | 32 (11.6) | 0.94 |

| Bile duct diameter2 (mm) | 8.9 ± 4.2 | 8.4 ± 3.6 | 0.12 |

Other benign processes including chronic cholecystitis and adenomyomatosis, which need whole biopsy of the gallbladder for suspected malignancy.

Maximal dimension of the extrahepatic bile duct was measured by drip infusion cholangiography (51%), endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (35%), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (4%), magnetic resonance cholangiography (2%), and/or extracorporeal ultrasonography (8%).

These cases were retrospectively assessed for postoperative morbidity and mortality, operation time, and length of hospital stay, as well as late outcomes before and after the introduction of the educational program that adopted IOUS as a routine operative guide.

For statistical analysis, Student’s t test, χ2 test, and analysis of covariance were used appropriately, and the SPSS 11.0 for Windows was used for the analysis. Statistically, it was determined that P < 0.1 indicated a tendency and P < 0.05 indicated a significant difference.

Procedure of IOUS

A deflectable sonographic probe with a linear head of 7-7.5 MHz LAP-703LA (Toshiba-Mochida, Tokyo, Japan), PEF-704LA (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) and MH-300 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used. After pneumoperitoneum, a probe was inserted from a port on the left upper abdomen, and the entire extrahepatic biliary tract from the hepatic hilum to the biliary terminal was scanned, before initiating an exfoliating procedure around the gallbladder. The presence or absence of visualization of the right and left hepatic duct, the common hepatic duct, the common bile duct, the intrapancreatic bile duct, the gallbladder, the cystic duct, and the right hepatic artery were recorded as video recordings and photographs. Next, an intraoperative diagnosis for surgery was made by creating both transverse and longitudinal ultrasonographic images of the gallbladder and the bile duct. When the anatomy at the confluence of the extrahepatic bile duct and the cystic duct could not be sufficiently confirmed due to either acute cholecystitis or adhesion, IOUS was performed during and after the exfoliating procedure and before clipping to avoid duct injury.

In the earlier period, senior surgeons performed IOUS. In the later period, when a senior surgeon performed the operation, a demonstration of the IOUS procedure was given to a junior surgeon. On the other hand, when a junior surgeon performed the operation, they were required to perform IOUS on their own, to understand the biliary anatomy and to make a correct diagnosis. The senior surgeon gave appropriate suggestions or aids, if necessary, according to the junior surgeon’s skill.

Laparoscopic cholecystitis grading

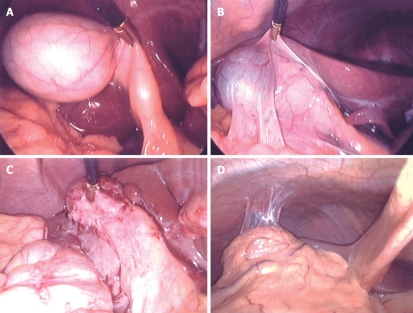

Inflammation around the gallbladder affects the visual field in laparoscopic surgery, as well as the level of difficulty of a surgical procedure. Moreover, it may affect diagnostic ability of IOUS. Therefore, laparoscopic cholecystitis grading (LCG) was suggested, based on macroscopic findings at the start of the laparoscopic surgery. The severity of cholecystitis was classified into four grades: G0, normal; G1, no acute inflammation with old fibrous adhesion; G2, marked inflammatory wall thickening with light adhesion; and G3, unidentifiable gallbladder due to dense inflammatory adhesion of the surrounding tissues (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Laparoscopic cholecystitis grading. A: Normal (G0); B: No inflammation with light adhesion (G1); C: Marked wall thickening with light adhesion (G2); D: Marked inflammation with dense adhesion (G3). Classification of severity of cholecystitis was based on laparoscopic findings to assess the effect of the presence of cholecystitis on intraoperative diagnostic performance and operative performance.

RESULTS

In the earlier period, senior surgeons performed surgery in 93% of cases, while junior surgeons performed 72%. The average number of operations per surgeon was 5.1 in the later period. IOUS was performed in 19% of cases in the earlier period, but after introduction of the educational program, it was performed in 84% of cases. There was no significant difference in the frequency of anatomical variations of the biliary tree between the two groups (2.7 vs 4.3%, P = 0.26). According to the cholecystitis grade as determined under laparoscopic view, the degree of cholecysitis was different between the two periods (P = 0.03); the percentage with G2 disease was higher in the earlier period, while G3 was higher in the later period. The number of conversions to open surgery due to cholecystitis or adhesion significantly increased in the later period (P = 0.007). In the earlier period, there were two cases of BDI treated with hepaticojejunostomy, while in the later period, no patients underwent laparotomy for BDI.

After the educational program began, the operation time increased by an average of 23 min in patients that were treated laparoscopically. There was no difference in surgery for bile duct stones, but in the later period, there was a significant extension of operation time in patients who underwent cholecystectomy (P < 0.0001). On the other hand, there was no significant difference in the amount of blood loss between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Various operations before and after routine IOUS

| Before routine IOUS (n = 368) | Routine IOUS (n = 276) | P | |

| Surgeon, n (%) | |||

| Senior (≥ 100 cases) | 341 (92.7) | 77 (27.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Junior (< 30 cases) | 27 (7.3) | 199 (72.1) | |

| Intraoperative image studies, n (%) | |||

| Ultrasound | 68 (18.5) | 231 (83.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Cholangiography | 45 (12.7) | 25 (9.1) | 0.14 |

| Anatomical variations of the bile ducts, n (%) | 10 (2.7) | 12 (4.2) | 0.26 |

| Laparoscopic cholecystitis grading, n (%) | |||

| G0 | 203 (55.2) | 166 (60.1) | 0.03 |

| G1 | 59 (16.0) | 40 (14.5) | |

| G2 | 72 (19.6) | 33 (12.0) | |

| G3 | 34 (9.2) | 37 (13.4) | |

| Conversion to open surgery, n (%) | 6 (1.6) | 15 (5.4) | 0.007 |

| BDI | 2 | 0 | 0.27 |

| Severe cholecystitis | 2 | 4 | |

| Cholecystoduodenal fistula | 0 | 1 | |

| Access failure due to dense adhesion | 1 | 5 | |

| Cancer suspected | 1 | 1 | |

| Systemic co-morbidity | 0 | 3 | |

| Total laparoscopic procedures, n (%) | 362 (98.4) | 261 (94.6) | 0.007 |

| Cholecystectomy | 317 (87.6) | 235 (90.0) | 0.34 |

| Cholecystectomy and choledocholithotripsy | 45 (12.4) | 26 (10.0) | |

| Operative time1 (min) | 93.7 ± 53.1 | 116.7 ± 49.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Cholecystectomy | 80.6 ± 36.2 | 109.4 ± 42.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Cholecystectomy and choledocholithotripsy | 185.4 ± 62.0 | 187.6 ± 61.2 | 0.88 |

| Blood loss1 (g) | 16.9 ± 75.5 | 14.1 ± 53.2 | 0.6 |

| Cholecystectomy | 10.1 ± 42.8 | 15.1 ± 55.4 | 0.23 |

| Cholecystectomy and choledocholithotripsy | 65.1 ± 175.4 | 4.2 ± 20.4 | 0.1 |

In cases treated with total laparoscopic procedures.

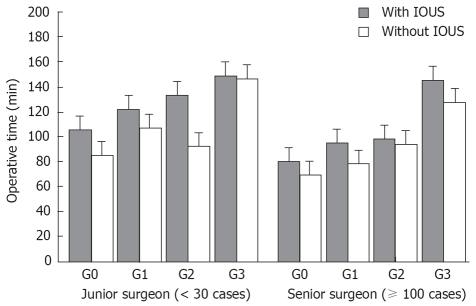

An analysis of covariance conducted on the prescribed factors of operative time showed that the degree of LCG (P = 0.002), presence or absence of implementation of IOUS (P = 0.01), and experience of the surgeon (P = 0.05) were significant factors for an extension of operation time after introduction of the educational program. No confounding effect was observed for these three factors (Table 3). The relationship between these three factors and the operation time is shown diagrammatically in Figure 2. The operation time was extended as LCG became more severe, and junior surgeons required more time for IOUS for all LCG compared with senior surgeons. The extension of operation time caused by implementation of IOUS for senior surgeons in the earlier period was 12.7 min (78.2 ± 37.8 min with IOUS vs 90.9 ± 32.4 min without IOUS, P = 0.02), while the average extension due to the use of IOUS for junior surgeons was 20.9 min (94.3 ± 43.6 min vs 115.2 ± 40.2 min, P = 0.003).

Table 3.

Factors determining operation time of LC

| Factors | F value | P value |

| Use of IOUS | 6.524 | 0.011 |

| Operative indication | 1.071 | 0.370 |

| Presence of cholecystitis symptom | 2.381 | 0.123 |

| Surgeon (senior/junior) | 3.778 | 0.053 |

| Intraoperative cholangiography | 1.685 | 0.195 |

| LCG: G0/G1/G2/G3 | 5.148 | 0.002 |

| IOUS × Surgeon | 0.208 | 0.648 |

| IOUS × LCG | 0.359 | 0.782 |

| Surgeon × LCG | 0.424 | 0.736 |

Figure 2.

Operative time for LC. In an analysis of covariance, LCG, as well as presence and absence of implementation of IOUS, were significant factors that affected operation time. Operation time when IOUS was implemented significantly increased for junior surgeons (all, P < 0.01), regardless of LCG, thus requiring approximately double the time in comparison to that of senior surgeons.

Regarding the frequency of early intraoperative and postoperative complications, the number that required re-operation, and mortality, there was no significant difference between the two periods, despite the fact junior surgeons performed many operations in the later period. Moreover, there were no cases of BDI after introduction of IOUS, and a decreasing tendency was observed (P = 0.08). The length of hospital stay was shortened in the later period, but it was assumed that a major reason for this included changes in the clinical pathway applied. There was no late bile duct stenosis in the later period (Table 4).

Table 4.

Early and late results

| Outcome | Before routine use (n = 368) | Routine use (n = 276) | P |

| Early complication, n (%) | |||

| BDI | 4 (1.1) | 0 | 0.08 |

| Arterial bleeding requiring clips | 9 (2.4) | 5 (1.8) | 0.59 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0.74 |

| Surgical site infection | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0.84 |

| Re-operation | 11 (0.3) | 12 (0.4) | 0.84 |

| Hospital death | 13 (0.3) | 0 | 0.39 |

| Postoperative treatment for duct stone | 74 | 25 | 0.19 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 5.4 ± 5.7 | 4.4 ± 2.6 | 0.006 |

| Late complication (> 1 yr), n (%) | |||

| Bile duct recurrence | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | 0.39 |

| Bile duct stricture | 0 | 0 | - |

Open hemostasis of postoperative bleeding from the liver bed;

Laparoscopic hemostasis of a small arterial bleeding at the port site;

Brain stem infarct on POD 4;

All treated with percutaneous cholangiofiberscopic lithotripsy through preoperatively-established sinus tracts;

Both treated with endoscopic sphincterotomy.

The BDI that occurred in the earlier period included three cases of complete disjunction of the bile duct. All cases were identified for the first time after the bile duct was damaged. In Case 1, the bile duct was severed due to misidentification of the cystic duct, but it was caused by a variant distribution of the cystic duct and the extrahepatic bile duct. In Case 2, because tenting occurred in the common bile duct due to pulling of the gallbladder, the bile duct was misidentified as the cystic duct. Case 3 was caused by variation in the distribution of the biliary tract where the cystic duct joined the accessory hepatic duct. In the remaining case, a small fissure occurred in the hepatic duct during an exfoliating procedure of the severely inflamed gallbladder, and was treated with simple suturing. Furthermore, hepatocholangiojejunostomy was performed during laparotomy in two cases (Table 5).

Table 5.

BDI during LC

| Age (yr)/gender | Indication | Anatomical variation | LCG | Type of injury | Repair | |

| 1 | 58/female | Cholecystolithiaisis | +1 | 2 | Cutting of the common hepatic duct | Hepaticojejunostomy (Roux-en-Y) |

| 2 | 43/female | Cholecystolithiaisis | - | 0 | Cutting of the common hepatic duct | Hepaticojejunostomy (Roux-en-Y) |

| 3 | 86/female | Chronic cholecystitis (cancer suspected) | +2 | 0 | Cutting of the posterior branch of the right hepatic duct | Duct-to-duct anastomosis using an internal stent |

| 4 | 63/female | cholecystocholedocholithiais | - | 3 | A small tear of the common hepatic duct at the dense adhesion to the neck of the gallbladder | Simple suture |

The cystic duct ran behind the common hepatic duct and connected with it at the left lateral wall near the pancreas;

The cystic duct joined the posterior branch of the right hepatic duct.

Regarding the 299 cases in which IOUS was performed, anatomical visualization of IOUS was 100% for the gallbladder, 97.3% for the extrahepatic bile duct, 96.3% for the pancreatic bile duct, 98.5% for the gallbladder duct, and 98.4% for the right hepatic artery. The diagnostic performance of IOUS regarding the indicated disorders was equal to preoperative diagnostic imaging, but 10 cases determined to have no bile duct stones via preoperative diagnostic imaging were diagnosed to have complications of choledocholithiais via IOUS, which turned out to be useful for making changes in the operation policy (Table 6). Biliary tract anatomy was visualized in almost all patients with G0-G2 laparoscopic cholecystitis, whereas visualization remained at 88% for G3 disease (Table 7).

Table 6.

Diagnostic accuracy of IOUS (%)

|

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

PPV |

NPV |

Overall accuracy |

||||||

| Pre-op | IOUS | Pre-op | IOUS | Pre-op | IOUS | Pre-op | IOUS | Pre-op | IOUS | |

| Anatomical variation | 25 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 100 | 96 | 100 |

| Cholecystolithiasis | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 87 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| Bile duct stone | 76 | 76 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 93 | 95 | 95 | 96 | 95 |

| Polyps | 77 | 82 | 98 | 98 | 77 | 75 | 98 | 99 | 97 | 97 |

| Others | 50 | 81 | 93 | 95 | 70 | 82 | 86 | 94 | 83 | 92 |

PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; Pre-op: Preoperative image studies; Anatomical variation: Anatomical variation of the extrahepatic bile duct. Preoperative image studies included extracorporeal ultrasonography (100%), computed tomography (73%), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancratography (51%), drip infusion cholangiography (42%), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (20%), and/or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (5%).

Table 7.

Ultrasonographic visualization of the biliary and arterial structures according to the laparoscopic cholecystitis grading (%)

| G0 | G1 | G2 | G3 | P value | |

| Gallbladder | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| Cystic duct | 100 | 95.6 | 100 | 91.4 | 0.001 |

| Bifurcation | 97.1 | 95.6 | 93.3 | 88.6 | 0.15 |

| Common hepatic duct | 99.4 | 95.6 | 97.8 | 88.6 | 0.003 |

| Intrapancreatic bile duct | 98.3 | 97.5 | 93.3 | 88.6 | 0.03 |

| Right hepatic artery | 100 | 97.5 | 100 | 89.3 | 0.0004 |

DISCUSSION

In the educational program for laparoscopic biliary surgery with IOUS as a guide, no cases of BDI were observed, despite the fact that less-skilled surgeons performed the operation in 72% of patients.

BDI is mostly caused by anatomical misidentification of the bile duct[9–11]. In addition, it is frequently caused by less-skilled surgeons[27,28]. The reasons for this misidentification are that laparoscopic surgery is performed in a two-dimensional world without any touch sensation, and that young surgeons have fewer opportunities to understand the anatomy of the biliary tract in abdominal surgery. Therefore, auxiliary means to improve understanding of the biliary tract anatomy is necessary to avoid BDI.

Cholangiography is an effective method for understanding biliary tract pathology[2,5,14]. However, its preventive effect against BDI is controversial[12,13,15], because a randomized control trial has not yet been conducted. Moreover, cholangiography has an unavoidable risk that examination can cause ductal injury during cannulation. Furthermore, there is the problem that BDI cannot be prevented in patients in whom the cystic duct merges into the accessory bile duct, as in our Case 3.

IOUS, on the other hand, is a less-invasive procedure than cholangiography. It can be performed in most cases more quickly and repeatedly, without any damage to the biliary tree[17–20]. Moreover, it does not require new X-ray apparatus, radiologists, or laboratory technicians. Many studies, including two randomized control trials, have reported that visualization of the biliary tract anatomy and diagnostic performance of IOUS for bile duct stones are as high, or better, than those for cholangiography[17,21–23]. It has also been reported that IOUS decreases the necessity to perform cholangiography[29,30].

However, it is necessary to learn properly and fully the technique of implementing IOUS[25]. Falcone et al[26] have reported it is necessary to learn the procedure from at least 10 cases. While there are many reports on the efficacy of IOUS, there has been no analysis on the clinical outcome and the time burden in these learning curve periods needed for IOUS.

Therefore, we introduced routine IOUS to laparoscopic surgery for the purpose of educating less-skilled surgeons regarding the anatomy of the biliary tract and avoidance of BDI. IOUS was able to be implemented in all cases, and the visualization ability for the extrahepatic bile duct was almost 100%. The diagnostic sensitivity for abnormal distribution of the biliary tract also significantly improved to 100% through the concomitant use of IOUS, from 25% by preoperative examinations only. Consequently, an abnormal distribution or tenting of the biliary tract was identified in all of our patients before the exfoliating procedure and other invasive procedures such as clipping of the cystic duct, so BDI was avoided. Moreover, the incidence rate of postoperative morbidity and mortality in the latter stages did not increase, despite operations being performed by less-skilled surgeons.

While IOUS has high feasibility, there is a concern that inflammatory processes around the gallbladder may reduce visualization of the biliary anatomy. Therefore, an LCG system was suggested to study the visualization rate of the biliary structures according to the degree of cholecystitis. In G0-G2, the confluence of the cystic and bile ducts was confirmed within the hepatoduodenal ligament in almost all cases. Biliary tract injury due to misidentification occurs frequently in cases without or with mild-to-moderate cholecystitis, therefore, IOUS is expected to have an effect in preventing biliary tract injury. On the other hand, for severe cholecystitis (G3), the gallbladder was identified in all cases, but the visualization rate of the extrahepatic bile duct and cystic duct decreased to 88%. In patients in whom the bile duct was visualized via IOUS, laparoscopic surgery was performed safely, but in cases in which the bile duct could not be identified, insufficient identification of the bile duct was determined to be the reason for conversion to laparotomy. Therefore, the number of cases converting to a laparotomy increased in the later period, which had a higher percentage of G3 disease.

After the introduction of the educational program for laparoscopic biliary surgery, the operative time became significantly extended. Higher LCG, implementation of IOUS, and performance by an inexperienced surgeon were independent factors that significantly extended the operation time. The operation time with a junior surgeon was extended by an average 20.9 min, after implementation of IOUS, which was approximately double the time in a previous study of 10 min[17]. In addition to the technical demonstration of IOUS by senior surgeons, junior surgeons were required to perform IOUS again and record all the biliary structures on a check list. Moreover, the extended time required for IOUS implementation was calculated by measuring the total operation time, which included the time required for preparation and recording of IOUS, unlike in previous studies in which only the time of implementing IOUS was recorded[17,19,22]. Consequently, a longer period of time was recorded in this study, especially when junior surgeons operated.

In any educational programs, the burden on the patient must be within acceptable limits. The extended time required for IOUS is believed acceptable compared with the time required for cholangiography[17–20], along with the advantage of increasing the possibility of avoiding biliary tract injury. Of course, it is necessary to analyze the economic efficiency of the introduction of IOUS. The system of paying medical expenses in Japan has largely changed during the past 10 years, therefore, it is difficult to directly compare expenses. However, after the introduction of this educational program, the frequency of complications did not increase, and the frequency of BDI tended to decrease. Therefore, an extension of operation time was the only economic disadvantage, and the increase in expenses was moderate. Furthermore, the amount invested in probes for IOUS is small, and cost effectiveness is higher than that of cholangiography.

This study had prospective data collection but it did not constitute a randomized control trial. Moreover, because the decrease in frequency of BDI remained at P = 0.08, the benefit of the education program for using IOUS cannot be concluded. Furthermore, to confirm the educational outcomes, it is necessary to conduct a follow-up review on the performance of subsequent laparoscopic biliary tract surgery performed by a physician who has completed the educational program. It will therefore be necessary to assess the benefits of this educational program for laparoscopic biliary surgery using IOUS after more extensive randomized control trials.

COMMENTS

Background

Bile duct injury (BDI) following laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) occurs at a rate twice that observed after open surgery, and misidentification of the biliary tract structures is the major cause of BDI. Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) is less invasive and reportedly has an equal or higher visualization ability of the biliary tract anatomy in comparison to cholangiography.

Research frontiers

In this study, the authors developed a new educational program for laparoscopic biliary surgery by introducing IOUS routinely as a guide for anatomical understanding, and analyzed its efficacy in enabling surgeons to avoid BDI and other complications, as well as any burden during the learning period.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Under the IOUS-guided educational program, no case of BDI was observed, despite the fact that less-skilled surgeons performed the operation in 72% of patients. Excess operation time was minimal. IOUS was feasible even in the presence of severe cholecystitis.

Applications

The educational program using IOUS is expected to minimize the incidence of BDI following LC, especially when performed by less-skilled surgeons, by giving them accurate, real-time information about the biliary tract structures.

Peer review

This study is very interesting, as it appeared to explore a good alternative to intraoperative cholangiography. In general, this clinical research was well performed and the results were convincing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Masaaki Endoh, previous chair of the hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgery division, for his contribution to the introduction of an IOUS-guided educational program for laparoscopic biliary surgery at our institute.

Peer reviewer: Peter Draganov, University of Florida, 1600 SW Archer Rd., Gainesville, FL 32610, United States

S- Editor Sun YL L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lu W

References

- 1.Connor S, Garden OJ. Bile duct injury in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:158–168. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher DR, Hobbs MS, Tan P, Valinsky LJ, Hockey RL, Pikora TJ, Knuiman MW, Sheiner HJ, Edis A. Complications of cholecystectomy: risks of the laparoscopic approach and protective effects of operative cholangiography: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 1999;229:449–457. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savader SJ, Lillemoe KD, Prescott CA, Winick AB, Venbrux AC, Lund GB, Mitchell SE, Cameron JL, Osterman FA Jr. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related bile duct injuries: a health and financial disaster. Ann Surg. 1997;225:268–273. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199703000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Santibanes E, Palavecino M, Ardiles V, Pekolj J. Bile duct injuries: management of late complications. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1648–1653. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, Dellinger EP, Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168–2173. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, Bergman JJ, Obertop H, Huibregtse K, Gouma DJ. Impaired quality of life 5 years after bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective analysis. Ann Surg. 2001;234:750–757. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200112000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Reuver PR, Rauws EA, Bruno MJ, Lameris JS, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Survival in bile duct injury patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a multidisciplinary approach of gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons. Surgery. 2007;142:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troidl H. Disasters of endoscopic surgery and how to avoid them: error analysis. World J Surg. 1999;23:846–855. doi: 10.1007/s002689900588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hugh TB. New strategies to prevent laparoscopic bile duct injury--surgeons can learn from pilots. Surgery. 2002;132:826–835. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen D. Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:133–138. doi: 10.1007/s004649900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu JS, Peng C, Mao XH, Lv P. Bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy: sixteen-year experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2374–2378. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i16.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amott D, Webb A, Tulloh B. Prospective comparison of routine and selective operative cholangiography. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:378–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepner U, Grunthal V. Intraoperative cholangiography can be safely omitted during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective study of 413 consecutive patients. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:197–200. doi: 10.1177/145749690509400304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waage A, Nilsson M. Iatrogenic bile duct injury: a population-based study of 152 776 cholecystectomies in the Swedish Inpatient Registry. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1207–1213. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.12.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright KD, Wellwood JM. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy without operative cholangiography. Br J Surg. 1998;85:191–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livingston EH, Miller JA, Coan B, Rege RV. Costs and utilization of intraoperative cholangiography. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1162–1167. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catheline JM, Turner R, Paries J. Laparoscopic ultrasonography is a complement to cholangiography for the detection of choledocholithiasis at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1235–1239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halpin VJ, Dunnegan D, Soper NJ. Laparoscopic intra-corporeal ultrasound versus fluoroscopic intraoperative cholangiography: after the learning curve. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:336–341. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machi J, Tateishi T, Oishi AJ, Furumoto NL, Oishi RH, Uchida S, Sigel B. Laparoscopic ultrasonography versus operative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: review of the literature and a comparison with open intraoperative ultrasonography. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:360–367. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu JS, Dunnegan DL, Soper NJ. The utility of intracorporeal ultrasonography for screening of the bile duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:50–60. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birth M, Ehlers KU, Delinikolas K, Weiser HF. Prospective randomized comparison of laparoscopic ultrasonography using a flexible-tip ultrasound probe and intraoperative dynamic cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:30–36. doi: 10.1007/s004649900587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson DM, Arregui ME, Tetik C, Madden MT, Wegener M. A comparison of laparoscopic ultrasound with digital fluorocholangiography for detecting choledocholithiasis during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:929–932. doi: 10.1007/s004649900749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tranter SE, Thompson MH. A prospective single-blinded controlled study comparing laparoscopic ultrasound of the common bile duct with operative cholangiography. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:216–219. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biffl WL, Moore EE, Offner PJ, Franciose RJ, Burch JM. Routine intraoperative laparoscopic ultrasonography with selective cholangiography reduces bile duct complications during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:272–280. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catheline JM, Turner R, Rizk N, Barrat C, Buenos P, Champault G. Evaluation of the biliary tree during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: laparoscopic ultrasound versus intraoperative cholangiography: a prospective study of 150 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falcone RA Jr, Fegelman EJ, Nussbaum MS, Brown DL, Bebbe TM, Merhar GL, Johannigman JA, Luchette FA, Davis K Jr, Hurst JM. A prospective comparison of laparoscopic ultrasound vs intraoperative cholangiogram during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:784–788. doi: 10.1007/s004649901099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Archer SB, Brown DW, Smith CD, Branum GD, Hunter JG. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a national survey. Ann Surg. 2001;234:549–558; discussion 558-559. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francoeur JR, Wiseman K, Buczkowski AK, Chung SW, Scudamore CH. Surgeons' anonymous response after bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2003;185:468–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machi J, Oishi AJ, Tajiri T, Murayama KM, Furumoto NL, Oishi RH. Routine laparoscopic ultrasound can significantly reduce the need for selective intraoperative cholangiography during cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:270–274. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0817-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onders RP, Hallowell PT. The era of ultrasonography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2005;189:348–351. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]