Tuberculosis (TB) is a very old disease, and tuberculosis bacilli have co-existed with humans as far back as 5000 BC, according to studies of the spine TB lesions (Pott’s disease) from Egyptian mummies.1 TB continues to be a frequent cause of mortality and morbidity, with an incidence rate of 150 cases per 100,000 people in 2005. Currently, one person becomes newly infected every second worldwide.2

TB mostly affects the lungs as it is an airborne infectious disease, but any organ can be affected as a result of hematogenous spread. It has been suggested that some organs and tissues like the mammary gland tissue and spleen offer resistance to the survival and multiplication of tuberculosis bacillus.3 Hence, tuberculosis of the breast is an uncommon disease, with an incidence between 0.1%– 3% of all breast diseases treated surgically.4 Its incidence is likely to be higher in undeveloped countries as a result of the high TB incidence, but with an increasing spread of HIV in developed countries, this pattern of incidence may change. TB is a very rare disease, so a high level of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis. Breast TB can mimic breast carcinoma or breast abscess, clinically and radiologically. Concomitant axillary lymph nodes were found in one-third of the patients with breast TB.5 This paper presents three cases to argue that breast TB should be included in the differential diagnosis of breast lesions, like breast carcinoma, persistent breast abscess and infectious patterns with fistulizations, especially for patients from high risk populations and endemic regions.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case-1

A 26-year-old female patient presented with painful swelling, with multiple discharging sinuses of the right breast and a palpable lump in her right breast. According to the patient, the lump had been present for the past six to seven months, and the sinuses had developed recently (Fig-1). On physical examination, the right breast was very tender, and a diffuse, irregular mass was felt, mainly involving the lower quadrants. There overlying skin was discolored, with multiple sinuses discharging a dirty yellow fluid. The patient was treated with several nonspecific antibiotics by her family physician, but her breast symptoms remained the same. With these signs and symptoms, she was admitted to our general surgery department. The patient’s laboratory data was 11.600 leukocytes/mm3 and an ESR of 70 mm/hr.

Figure 1 -.

There was discoloration of the overlying skin with multiple sinuses discharging fluid

Case-2

A 30-year-old female patient presented with a 2-month history of a painful erythematous left breast lump, with an associated sinus tract. She had received several empiric antibiotics and had previously undergone drainage of the breast lesion on several occasions, but her symptoms persisted. She had delivered her third baby 13 months earlier. On breast examination, a large tender mass was felt in the inner half of the left breast. A sinus tract was felt near the nipple and it was freely mobile, with no axillary nodes (Fig-2).

Figure 2 -.

A large tender mass was felt in the inner half of the left breast, and a sinus tract was present near the nipple

Case-3

A 43-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with complaints of swelling, breast lump and erythema of the skin in her right breast, which appeared 45 days earlier. On physical examination, a 6- to 7-cm, firm and mobile mass was observed, which caused erythema and edema of the skin in the inner lower quadrant of the left breast. There was no fistulization. Ultrasonography examination revealed a hypoechoic mass with significant ductal dilatation without collection and lymphadenopathy, which suggested mastitis.

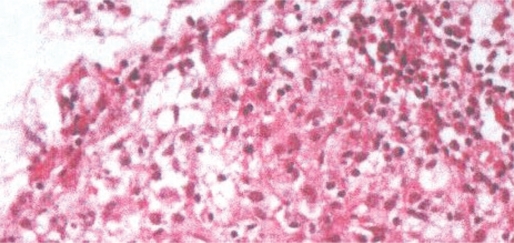

All three patients denied smoking, having risk factors for HIV or a recent exposure to tuberculosis. They had no past history of tuberculosis, and they had no family history of breast cancer. Tuberculin skin test results (Mantoux) were 16, 13 and 14 mm for cases 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Their routine hematologic and biochemical parameters were in the normal range, including negative testing for HIV. Their erythrocyte sedimentation rates were also normal. Their sputum smears and discharge materials from the breast were found to be negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), both in culture and by PCR. All of their chest X-rays were normal. Both trucut and fine needle biopsy were applied to their breast lesions. Their pathological examinations showed chronic granulomatous inflammation with areas of central necrosis, epithelioid granulomas with Langhans giant cells and lymphohistocytic aggregates suggestive of tuberculosis (Fig-3). The patients were all diagnosed as breast tuberculosis according to pathological examinations. The intensive therapy with anti-tuberculosis drugs (isoniazid 300 mg, rifampicin 600 mg, pyrazinamide 1500 mg and ethambutol 1000 mg per day) was initiated for 2 months and continued with the addition of rifampicin and isoniazid therapy for an additional four months. With treatment, their breast lesions and tenderness steadily improved. Cures were obtained for all patients at the end of the sixth month period.

Figure 3 -.

Tissue biopsy demonstrating the formation of epithelioid granulomas with Langerhans giant cells and lymphohistocytic aggregates, HE400x

DISCUSSION

In 1829, Sir Astley Cooper defined breast tuberculosis as the ‘scrofulous swelling of the bosom’.6 The lump is the most common presentation in breast tuberculosis.7 These breast lumps are mostly misdiagnosed as fibroadenoma, fibroadenosis, malignancy or breast abscess. The three main features of breast TB are nodular, disseminated and sclerosing, and these features result in multiple discharging sinuses, lumps, ulcers and recurring abscesses of the breast are observed. Tubercular lumps are mostly irregular, ill-defined and mostly more painful than that seen in carcinoma. Pain is usually dull and constant in breast TB. In Puneet’s series,7 12 patients were clinically misdiagnosed as fibroadenoma, 17 as fibroadenosis and 8 as carcinoma.

Breast tuberculosis commonly affects young multiparous, lactating women. Although cases have been reported from age 6 months to 73 years, most were between 20 to 40 years old.8,9 All of these cases were multiparous, and their mean age was 33 years. According to Wilson,10 the right and left sides of the breast were involved equally often. In contrast, Pal11 reported that there is a slight tendency for the right breast to be more frequently affected as it was in our patient series. Sharma12 found that the duration of symptoms ranged from 6 months to 2 years, and in the case series of Khanna,13 the mean duration of symptoms was 8.5 months.

Breast TB may be considered primary when no other demonstrable focus exists, and may be considered secondary when a preexisting lesion is located elsewhere. M. tuberculosis can spread to the breast by the lymphatic and hematogenous routes or directly, and it can persist for long periods within the body. It is generally thought that the breast gets involved in tuberculosis by retrograde lymphatic extension from the mediastinal, axilla and cervical region,13 but in the cases reported here, there was no associated lympadenopathy as confirmed by physical exam and ultrasonography and no other foci of tuberculosis infection, and all chest x-rays were normal. Direct infection of the breast may occur through skin abrasions or through the milk duct openings. All three patients were in their reproductive ages with multiple children, all of whom were breastfed for at least 6 months. Lactation is known to increase the susceptibility of the breast to tuberculosis since during lactation, the increased vascularity of the breast may facilitate infection and dissemination of the bacilli. Shinde5 found that 7% of their patients were lactating at the time of presentation, while Banerjee3 reported that 33% of their patients were lactating. Two of these patients had recent lactation history.

Although it is very specific and acts as the gold standard for the diagnosis, M. tuberculosis stain, culture or PCR is not very sensitive, and this may cause some additional delays for diagnosis and under-diagnosis.14 Bacteriological examination of discharge from the sinus was negative for M. tuberculosis on staining as well as culture in most cases.15 However, all of these cases had breast TB, as they responded to antituberculosis treatment. The bacteriological results were negative for staining, culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tuberculosis tests. Environmental conditions can alter the physiology and virulence of M. Tuberculosis, since it requires oxygen for its growth and survival. As the mammary gland tissue may convey some resistance to the survival and multiplication of the tuberculosis bacillus, we expected that the number of M. tuberculosis bacilli in the tissue would be small, making it difficult to prove their existence. On the other hand, an AFB-positive smear can be seen from other mycobacteria species, so it is not a definitive mycobacterial diagnosis for TB. Most of the time, pathological examinations are more valuable than bacteriological examinations and are preferred for the accurate diagnosis of breast TB. Khanna13 found that in 52 patients with breast TB, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was 100% reliable in diagnosing breast TB. A newly developed T-cell–based, whole-blood enzyme-linked immunosorbent interferon release assay detects interferon. Interferon is secreted by T cells in response to antigens encoded in the region of difference 1 of M. tuberculosis, a genomic segment absent from Calmette–Guerin bacilli and most environmental mycobacteria. Thus, the test confers a higher specificity than the tuberculin skin test.16 Moreover, results are available in 24 hours. Unfortunately, we could not perform these tests in our hospital.

Histopathological confirmation of breast TB requires cytological evidence of caseous necrosis epitheloid granulomas and Langhans giant cells with lymphohistocytic aggregates. The differential diagnosis of breast TB includes other granulomatous inflammatory diseases, such as idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (GM), sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis and giant cell arteritis, as well as other infections like actinomycosis and fat necrosis. In idiopathic GM, the granulomatous inflammatory reaction, consisting of epitheloid and giant cells, is confined to the breast lobules in which there is also leukocyte infiltration and abscesses but no caseation.17 In breast TB, the distribution of granulomas is diffuse and is not limited to the lobules, and they are accompanied by caseation necrosis. This necrosis results in the characteristic fistulization of skin lesions. In plasma cell mastitis, there is inflammation in the breast tissue in response to the irritating quality of fatty material accumulated in dilated ducts. The granulomatous reaction in traumatic fat necrosis is confined to the broken down fat globules. Fat necrosis can also be eliminated as a diagnosis by the absence of fat globules. With appropriate serological investigation, arteritis, the absence of sulfur granules in the discharge of the sinus of the suppurating lesions and actinomycosis can all be eliminated from the differential diagnosis.18

Radiological imaging modalities like mammography or ultrasonography are unreliable in distinguishing tuberculosis mastitis from carcinoma because of its nonspecific features.19 Similarly computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are not diagnostic without histological confirmation.

Immunosuppressive conditions, like organ transplantations and HIV infections, advanced age, and chronic diseases, increase the chance that tuberculosis presents atypically with extrapulmonary manifestations that can result in delays in diagnosis and treatment. A high degree of clinical suspicion and familiarity with physical examination findings are necessary to enable an early diagnosis. This requirement for familiarity motivated us to present our experience with breast TB to increase the awareness of other doctors of this condition, and to enable the prevention of delays in the diagnosis of breast TB and of unnecessary interventions and surgical procedures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tan SY, Berman E. Robert Koch (1843–1910): father of microbiology and Nobel laureate. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:854–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/index.html

- 3.Banerjee SN, Ananthakrishnan N, Mehta RB, Parkash S. Tuberculous mastitis: a continuing problem. World J Surg. 1987;11:105–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01658471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalali U, Rasul S, Khan A, Baig N, Khan A, Akhter R. Tuberculous mastitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:234–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinde SR, Chandawarkar RY, Deshmukh SP. Tuberculosis of the breast masquerading as carcinoma: a study of 100 patients. World J Surg. 1995;19:379–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00299163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper A.Illustrations of the Diseases of the Breast, Part1 London, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.1829. p. 73.

- 7.Puneet, Satyendra K, Tiwary, Ragini Ritu, Singh Sanjay, Gupta SK, et al. Breast Tuberculosis: Still Common In India The Internet Journal of Tropical Medicine 2005. 2:2. (http://www.ispub.com/ostia/index.php?xmlFilePath=journals/ijtm/vol2n2/breast.xml)

- 8.Kedar GP, Bophate SK, Kherdekar M. Tuberculosis of breast. Ind J Tub. 1985;32:146. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsiddig KE, Khalil EA, Elhag IA, Elsafi ME, Suleiman GM, Elkhidir IM, et al. Granulomatous mammary disease: ten years’ experience with fine needle aspiration cytology. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:365–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson TS, Macgregor JW. The diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the breast. Can Med Assoc J. 1963;89:1118–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal KD. Tuberculosis of breast- a retrospective review of cases. Ind J Tub. 1998;45:35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma PK, Babel AL, Yadav SS. Tuberculosis of breast (study of 7 cases) J Postgrad Med. 1991;37:24–6. 26A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna R, Prasanna GV, Gupta P, Kumar M, Khanna S, Khanna AK, et al. Mammary tuberculosis: report on 52 cases. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:422–4. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.921.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozol D. Bacteriology or Pathology for tuberculous mastitis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, Mazahreh TS. Tuberculous mastitis: a disease not to be forgotten. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:920–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dosanjh DP, Hinks TS, Innes JA, Deeks JJ, Pasvol G, Hackforth S, et al. Improved diagnostic evaluation of suspected tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:325–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goksoy E, Duren M, Durgun V, Uygun N. Tuberculosis of the Breast. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:471–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozol D, Bozer M, Bayrak R. Breast tuberculosis. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1066–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Marri MR, Aref E, Omar AJ. Mammography features of isolated tuberculous mastitis. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:646–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]