Abstract

Proactive coping, directed at an upcoming as opposed to an ongoing stressor, is a new focus in positive psychology research. However, two differing conceptualizations of this construct create confusion. This study compared how each operationalization of proactive coping relates to well-being. Participants (N = 281) facing an upcoming college examination completed the Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI; consisting of two subscales that each assess one of the conceptualizations), the Proactive Competence Scale (PCS; that assesses the proactive coping process), and measures of well-being. The results demonstrated that conceptualizing proactive coping as a positively-focused striving for goals was predictive of well-being (the shared variance from affect, subjective well-being and physical symptoms), whereas conceptualizing proactive coping as focused on preventing a negative future was not. The first conceptualization of proactive coping’s unique association with well-being was explained by two of the proactive competencies, use of resources and realistic goal setting, and the remaining variance in well-being was explained by the first factor of optimism. These results demonstrated that aspiring for a positive future is distinctly predictive of well-being and that research should focus on accumulating resources and goal setting in designing interventions to promote proactive coping.

Keywords: Coping, optimism, positive psychology, well-being

Introduction

Proactive coping has emerged as a new focus of positive psychology research. It predicts outcomes such as functional independence, life satisfaction, and engagement (Gan, Yang, Zhou, & Zhang, 2007; Greenglass, Marques, de Ridder, & Behl, 2005; Uskul & Greenglass, 2005). However, the construct’s conceptualization has been guided by two similar, yet distinct, theoretical frameworks that use the same term, proactive coping (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997; Schwarzer & Taubert, 2002). Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) posit that proactive coping is a method of assessing future goals and setting the stage to achieve them successfully. Aspinwall and Taylor (1997) assert that proactive coping is a process through which one prepares for potential future stressors, possibly averting them altogether. Reconciling the inconsistent definitions of this important self-regulatory behavior would help to avoid confusion in its operationalization and would foster more fruitful future research.

One measure of proactive coping, the Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI; Greenglass, Schwarzer, Jakubiec, Fiksenbaum, & Taubert, 1999), includes both a subscale that captures proactive coping as defined by Schwarzer and Taubert (2002), labeled the proactive coping subscale, and a subscale that captures proactive coping as defined by Aspinwall and Taylor (1997), labeled the preventive coping subscale. Thus, the confusion surrounding the definition of proactive coping begins with the names of the subscales in this measure. Because this measure was developed by the same group of researchers that proposed the first conceptualization of proactive coping (Schwarzer & Taubert, 2002), the proactive coping subscale is consistent with their definition. Both the proactive coping subscale and the preventive coping subscale have been included in several studies (e.g., Gan et al., 2007; Greenglass et al., 2006; Greenglass, 2002; Greenglass et al., 2005; Ouwehand et al., 2006; Uskul & Greenglass, 2005).

A recent study included both the proactive coping subscale and the preventive coping subscale of the PCI (Gan et al., 2007). This large cross-sectional study of Chinese college students (N = 1,254) found that each translated subscale formed a distinct factor and the best fitting model included both subscales as related factors. A second study in another sample of Chinese college students (N = 171) examined the roles of both subscales in explaining the relationship between self-reported stress and student engagement; however, it evaluated them separately. The results indicated that only the proactive coping subscale fully mediated the relationship between stress and student engagement (Gan et al., 2007).

The two conceptualizations agree on the mechanisms through which proactive coping acts and the behaviors it manifests (Greenglass, 2002). The five stages of proactive coping as defined by Aspinwall and Taylor (1997) are: (1) resource accumulation; (2) recognition of potential stressors; (3) initial appraisal; (4) preliminary coping efforts; and (5) elicitation and use of feedback concerning initial efforts. A study based on this process model of proactive coping found that proactive coping (using the second conceptualization measured with the preventive coping subscale) correlated with three of four assessed proactive competencies at baseline (Bode, de Ridder, Kuijer, & Bensing, 2007). However, the study did not assess whether the proactive coping subscale predicted the proactive competencies, as well.

Optimism, defined as an overall expectancy that the future will work out favorably (Scheier & Carver, 1992), is considered influential in facilitating proactive coping (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997) and was found to be related to both the proactive coping and preventive coping subscales (Gan et al., 2007). In studies suggesting that proactive coping is associated with affect, satisfaction with life, and physical symptoms, optimism has also been related to these positive outcomes (Chang & Sanna, 2001; Uskul & Greenglass, 2005). Thus, it is important to establish if proactive coping uniquely predicts salutary outcomes above that which is predicted by the shared variance of optimism and proactive coping. Prior work found that proactive coping assessed with the proactive coping subscale remained significant in predicting lower depression and marginally significant in predicting life satisfaction after controlling for demographic variables and optimism (Uskul & Greenglass, 2005). Therefore, it would be useful to investigate this association with the preventive coping subscale, as well.

The Current Study

The current study aimed to clarify the conceptualization of the construct proactive coping and determine the process through which proactive coping results in positive outcomes. Therefore, the two definitions of proactive coping were examined simultaneously during the anticipatory stage of confronting an upcoming stressor, an exam in a psychology course. Studying this specific stressor is useful because it occurs in the future, participants have some degree of control over it, and it is the same for all participants (Bolger, 1990; Ouwehand et al., 2006). Also, exam scores represent an objective outcome measure.

As supported by the finding that proactive coping measured with the preventive coping subscale correlated with three of four proactive competencies, we hypothesized (1) that both the first and second conceptualizations of proactive coping would predict all four of the proposed proactive competencies. Additionally, given prior work showing that the proactive coping subscale remained a significant predictor of salutary outcomes after controlling for optimism, we further hypothesized (2) that the paths between both conceptualizations of proactive coping and the outcomes, well-being and exam grade, would be significant and explained by the proactive competencies.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Three hundred undergraduates 18 years of age and over and fluent in English participated in return for course credit. They provided informed consent and completed all questionnaires at a single point in the week before their second exam in a college course. Completing the questionnaire online through a secure survey program, PsychData, took less than one hour. A total of 281 participants completed all required measurements (age, M = 19.2, SD = 2.6; 59% female; 9.3% Hispanic vs. non Hispanic; 49.1% White, 29.5% Asian, 4.6% Black, 1.1% American Indian, 1.1% Pacific Islander, and 14.6% other). Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations of additional study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations, means and standard deviations of all study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Proactive Coping | -- | 0.60*** | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.46*** | 0.51*** | 0.72*** | 0.67*** | 0.06 | 0.55*** | −0.26*** | 0.43*** | −0.19** | 0.53*** | 0.50*** |

| 2. Preventive Coping | -- | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.32*** | 0.39*** | 0.48*** | 0.45*** | 0.12* | 0.33*** | −0.04 | 0.24*** | −0.04 | 0.18** | 0.20** | |

| 3. Age | -- | 0.16** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.07 | ||

| 4. Sex | -- | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.14* | 0.15* | −0.09 | 0.25*** | −0.16** | −0.02 | |||

| 5. Use of Resources | -- | 0.57*** | 0.62*** | 0.59*** | 0.00 | 0.47*** | −0.19** | 0.37*** | −0.10 | 0.40*** | 0.24*** | ||||

| 6. Future Appraisal | -- | 0.67*** | 0.65*** | 0.01 | 0.42*** | −0.18** | 0.33*** | −0.08 | 0.34*** | 0.24*** | |||||

| 7. Realistic Goal Setting | -- | 0.80*** | 0.07 | 0.58*** | −0.25*** | 0.51*** | −0.17** | 0.51*** | 0.43*** | ||||||

| 8. Use of Feedback | -- | 0.06 | 0.53*** | −0.26*** | 0.43*** | −0.23*** | 0.51*** | 0.35*** | |||||||

| 9. Exam Score | -- | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.11 | ||||||||

| 10. Positive Affect | -- | −0.14* | 0.49*** | −0.22*** | 0.48*** | 0.39*** | |||||||||

| 11. Negative Affect | -- | −0.37*** | 0.49*** | −0.41*** | −0.42*** | ||||||||||

| 12. Satisfaction With Life | -- | −0.28*** | 0.48*** | 0.44*** | |||||||||||

| 13. Physical Symptoms | -- | −0.33*** | −0.23*** | ||||||||||||

| 14. Optimism | -- | 0.54*** | |||||||||||||

| 15. Low Pessimism | -- | ||||||||||||||

| M | 42.45 | 26.63 | 19.22 | N/A | 12.24 | 9.24 | 25.76 | 18.87 | 34.86 | 30.10 | 23.63 | 21.77 | 110.87 | 11.14 | 6.34 |

| SD | 6.13 | 4.33 | 2.58 | N/A | 2.75 | 1.68 | 4.13 | 3.51 | 6.28 | 8.67 | 8.02 | 7.18 | 28.81 | 2.55 | 2.94 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Measures

Proactive coping

The proactive coping subscale of the Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI; Greenglass et al., 1999) was used to assess proactive coping according to the first definition (Proactive Coping 1; Schwarzer & Taubert, 2002) and the preventive coping subscale of the PCI was used to assess proactive coping according to the second definition (Proactive Coping 2; Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997). An example of an item from the proactive coping subscale is “I try to pinpoint what I need to succeed,” and an example of an item from the preventive coping subscale is “I plan for future eventualities.” Each item is assessed on a 4-point scale from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (completely true). It was anticipated that preventive coping item 7 would not apply to the current student sample and participants were instructed to leave it blank if it was not applicable. One hundred thirty-six participants did skip it and, therefore, it was omitted from the analyses. The final internal consistencies in the current sample were good for both the proactive coping subscale (α = .88) and the preventive coping subscale (α = .85).

Optimism

Dispositional optimism was measured with the Life Orientation Test – Revised (LOT-R; Scheier et al., 1994). It consists of 6 items and ratings are made on a 5-point scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Three of the items comprise the first factor (Optimism) and are worded in a positive direction (e.g., “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”), and three comprise the second factor (Low Pessimism) and are worded in a negative direction (e.g., “If something can go wrong for me, it will”). The internal consistency was adequate (Optimism, α = .61; Low Pessimism, α = .78; Total α = .80) in the current sample.

Proactive Competencies

The Proactive Competence Scale (PCS; Bode et al., 2007) is a 21-item measure designed to capture the five phases of proactive coping as conceptualized by Aspinwall and Taylor (1997). Ratings on items assessing participants’ reports of their abilities on items such as, “I am able to ask for support when things become difficult,” range from 1 (not at all able) to 4 (very able). Its four factors had adequately strong internal consistencies in the current sample: Use of resources (4 items, α = .81), future appraisal (3 items, α = .67), realistic goal setting (8 items, α = .88) and use of feedback (6 items, α = .85).

Well-Being

The latent variable Well-being was defined as the shared variance of affect, subjective well-being and physical symptoms.

Affect

Affect was assessed by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988). It asks participants how they felt “during the past week” by rating 20 adjectives such as “interested” or “distressed” on a scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). High internal consistency was found for both subscales in the current sample (positive affect, α = .92; negative affect, α = .88).

Subjective well-being

Subjective well-being was assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWL; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). It consists of five items rating statements such as, “In most ways my life is close to my ideal,” on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The internal consistency for this scale in the current sample was high (α = .90).

Physical symptoms

Physical symptoms were assessed by the Pennebaker Inventory of Limbic Languidness (PILL; Pennebaker, 1992). This 54-item measure assesses commonly-occurring physical symptoms (i.e., eyes watering, sneezing spells) on a scale of A (have never or almost never experienced the symptom) through E (more than once every week). The internal consistency for this scale in the current sample was high (α = .95).

Exam Score

The objective outcome, exam score, was evaluated by course instructors and converted to a Z-score based on the overall class performance.

Demographics

The demographic variables assessed were age, sex, ethnicity, race, Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT; a standardized test used for college admissions) score, and high school grade point average (GPA).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were evaluated using SPSS version 16.0 and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted with AMOS software (Arbuckle, 2007a). Only theoretically sound modification indices were incorporated and implemented incrementally with χ2 analyses indicating significant improvements at each step (Byrne, 2001). Additionally, non-significant paths were dropped with the goal of creating a parsimonious the model (Arbuckle, 2007b). Mediation analyses adapted to SEM (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Holmbeck, 1997; Kelloway, 1998) were used to determine if the paths from the predictors (Proactive Coping 1 and 2) to the outcomes (Well-being and exam score) were explained by the proposed mediating variables (proactive competencies). To establish mediation, there must be a direct effect of the predictor on the outcome, the model including the mediators must be a good fit to the data, all of the paths should be significant in the predicted direction, and two different versions of the model should be compared: (1) the fully mediated model (2) a model with a direct path allowed from predictor to outcome (Holmbeck, 1997; Kelloway, 1998). Additionally, the proportion of variance mediated was calculated by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect, (Shrout & Bolger, 2002), the bootstrap was set to 1,000 replications for the mediation analyses (Cheung & Lau, 2008; Shrout & Bolger, 2002) and the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals were reported as recommended (Cheung & Lau, 2008).

Results

Data Preparation

To prepare the data for the planned analyses, listwise deletion was used for 19 participants because of screening failures (n = 3), too many missing items (n = 2), and to reduce skewness and kurtosis (n = 14). This resulted in an N of 281. Values were imputed with linear interpolation in SPSS for participants missing fewer than 10% of their data.

Measurement Model

The measurement model that included the latent variables Proactive Coping 1 and 2, Optimism, Low Pessimism and Well-being was not a good fit to the data, χ2(94, N = 281) = 208.285, p < .001 (Bollen-Stine bootstrap, p = .007); CFI = .94; RMSEA = .07, p = .02; GFI = .91; TLI = .92. Two conceptually sound improvements (allowing the error terms from physical symptoms and negative affect and from positive affect and negative affect to covary) were made as suggested by the modification indices (see Bentler, 1990; Byrne, 2001). This resulted in a good fitting model, χ2(92, N = 281) = 135.736, p =.002 (Bollen-Stine bootstrap, p = .039); CFI = .98; RMSEA =.04, p = .84; GFI = .94; TLI = .97.

Overall Model

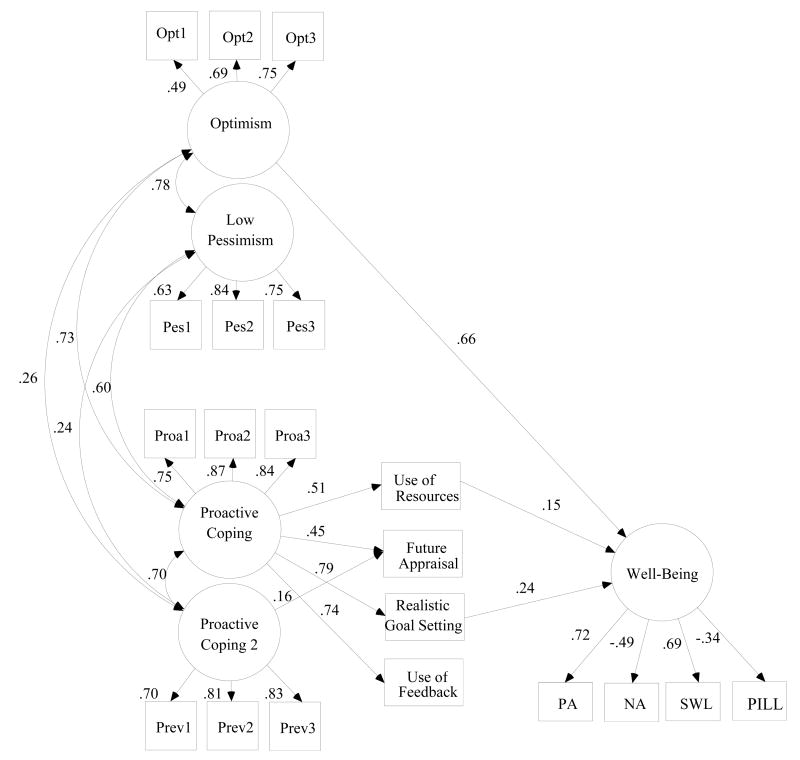

The proposed model included both Proactive Coping 1 and Proactive Coping 2 predicting all four measured variables of the proactive competencies, which in turn predicted both the latent variable, Well-being, and the measured variable, exam score. Optimism was also included in the model as two latent variables to control for its shared variance with Proactive Coping 1 and 2 and Well-being. This model was a poor fit to the data, χ2(166, N = 281) = 368.936, p < .001 (Bollen-Stine bootstrap, p = .001); RMSEA = .07, p = .002; CFI = .93; GFI = .88; TLI = .91. Therefore, exploratory post-hoc analyses were conducted. Modification indices suggested that the paths from the error terms of the factors from the PCS should be allowed to covary. This resulted in an improved model fit, χ2(160, N = 281) =247.562, p < .001 (Bollen-Stine bootstrap, p = .007); RMSEA = .4, p = .81; CFI = .97; GFI = .92; TLI = .96. However, there were still nonsignificant paths in the model, which were removed one at a time starting with the lowest regression weight. Since this resulted in a model where no paths to exam score remained, this variable was removed. These modifications resulted in a more parsimonious model that was a good fit to the data χ2(152, N = 281) = 224.871, p < .001 (Bollen-Stine bootstrap, p = .001); RMSEA = .04, p = .90 CFI = .97; GFI = .93; TLI = .97 (Figure 1). The final model was significantly kurtotic (Mardia’s coefficient = 26.64, critical ratio = 7.53), so the bootstrap bias-corrected values were checked and indicated that the parameters remained significant. The overall model accounted for 81.6% of the variance in Well-being.

Figure 1. Model of Proactive Coping 1 and Proactive Coping 2 predicting Well-being and exam grade and how these relationships are explained by the proactive competencies.

Note. PA = Positive Affect; NA = Negative Affect, SWL = Satisfaction With Life; PILL = Physical Symptoms. All path coefficients displayed are statistically significant (p < .05). For simplicity, error terms are not shown.

Hypothesis 2 proposed that the relationships between Proactive Coping 1 and Proactive Coping 2 to Well-being would be explained by the proactive competencies. The proactive competencies that remained as possible mediators were use of resources and realistic goal setting. The total effect of Proactive Coping 1 to Well-being was significant (β = .27 [.14, .38], p < .01), and the model including the mediated variables was already established to be a good fit to the data. Additionally, the paths from Proactive Coping 1 to the mediators (use of resources, β = .51, p < .01; realistic goal setting, β = .79, p < .01) and from the mediators to Well-being (use of resources, β = .15, p < .05; realistic goal setting, β = .24, p < .01) were significant in the predicted direction. Also, the fit of the fully mediated model was not significanlty different from the partially mediated model, χ2 diff (1, N = 281) = 0.246, p = ns. Lastly, the total effect of Proactive Coping 1 to Well-being was also completely reduced (β = .000 [.000, .000], p = ns), explained by the total indirect effects (β = .27, CI [.14, .38], p < .01). Therefore, 100% of the variance from Proactive Coping 1 that was not shared with Optimism appeared to be explained by use of resources and realistic goal setting.

Discussion

In summary, the action of the self-regulatory strategy proactive coping is most accurately described by the first conceptualization by Schwarzer and Taubert (2002), whereby Proactive Coping 1 was significantly associated with all of the mechanisms proposed in the theoretical framework (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997). Additionally, this conceptualization of proactive coping’s unique variance associated with Well-being was completely explained by accumulating resources and focusing on goal setting, whereas the remaining variance was accounted for by the first factor of optimism. Overall, this demonstrated that aspiring for a positive future rather than preventing a negative one is distinctly predictive of well-being and that this relationship is explained by two self-regulatory mechanisms.

Hypothesis 1, that both Proactive Coping 1 and Proactive Coping 2 would predict all of the proactive competencies, was partially confirmed; Proactive Coping 1 was associated with all of the proactive competencies, whereas Proactive Coping 2 was only associated with future appraisal. These results suggest that the proactive competencies proposed by Aspinwall and Taylor (1997) more accurately represent the aspects of self-regulation uniquely related to proactive coping as assessed by the proactive coping subscale than by the preventive coping subscale. In a previous study, the preventive coping subscale was positively related to all of the proactive competencies except for use of resources (Bode et al., 2007). Therefore, the prior association found between the preventive coping subscale and these proactive competencies may have been due to the variance that the preventive coping subscale shares with proactive coping subscale.

Hypothesis 2, that the paths between the proactive coping subscales and Well-being would be mediated by the proactive competencies, even when controlling for optimism, was also partially supported. The effect of Proactive Coping 1 on Well-being was fully mediated by use of resources and realistic goal setting, whereas the other proactive competencies (future appraisal, use of feedback) did not meet the requirements for mediation. Additionally, the path from Proactive Coping 2 to Well-being was not significant or explained by the included process variables.

The current study is the first to suggest that Proactive Coping 2’s proposed relationship with positive outcomes is at least partially due to its large proportion of shared variance with Proactive Coping 1. Although only a small amount of unique variance remained to be explained after accounting for this shared association, these variables still functioned differently in the model. The result that Proactive Coping 1 remained predictive of Well-being when accounting for optimism is consistent with a previous study (Uskul & Greenglass, 2005) and the use of a latent measure for optimism in the current study strengthens this notion. Notably, the finding that use of resources and realistic goal setting explained the relationship between Proactive Coping 1 and Well-being was also supported by previous research that showed associations between proactive coping with social support and goal orientation (Greenglass et al., 2006; Ouwehand, de Ridder, & Bensing, 2006). Also, the result that neither Proactive Coping 1 nor Proactive Coping 2 were related to exam score is consistent with a previous study that assessed this relationship (Diehl et al., 2006), but not with prior results whereby proactive personality predicted exam performance (Kirby et al., 2002).

Overall, the outcome that the positively-framed Proactive Coping was significantly associated with Well-being over and above the negatively-framed Preventive Coping is consistent with how the negativity bias and positivity offset are found to operate (Ito & Cacioppo, 2005). Individuals vary on their tendencies to use the negativity bias or positivity offset, which may explain why some people are more likely to proactively cope than others. Additionally, although the proactive coping is expected to remain stable across situations, it is possible that the proactive competencies that a participant draws upon may vary. These may act similarly to the coping strategies monitoring and blunting, whereby the adaptiveness of using these strategies was shown to be moderated by how much control the participant expected to have in the situation (Brown, & Bedi, 2001).

Limitations

The current study did not control for GPA as in previous studies (Bolger, 1990; Kirby et al., 2002) or SAT score because it was unclear if the students reported their GPA from high school or their university, and it was not possible to distinguish which students took the SAT before it was altered in 2005. Therefore, future research could consider these qualifications in order to partial out a degree of the possible noise in exam score that was not unique to achievement in the specific situation. In addition, the other included measures were self-report. This similar methodology may have contributed to the shared variance among the variables and thus other methods of assessment should be used. Also, these results from undergraduate participants may not apply to the general population due to the restricted age range and socioeconomic status inherent to this sample. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study was not ideal for testing mediation hypotheses. Therefore, future longitudinal research should be conducted to clearly establish the causal direction of these relationships.

Future Directions and Conclusions

The study suggests that the proactive coping subscale of the PCI, which assesses Schwarzer and Taubert’s (2002) definition of proactive coping, should represent the standard assessment of this construct. Additionally, the results partially support the theory explaining the mechanisms of proactive coping, as proposed by Aspinwall and Taylor (1997), suggesting that this framework be explored further in relationship to different outcomes to fully understand this process. Finally, these results imply that interventions aiming to strengthen the benefits of proactive coping should focus on promoting resources and realistic goal setting. Altering these competencies is more feasible than directly changing proactive coping, yet may eventually lead to this result. Effective interventions are already being developed and implemented to promote the proactive competencies in preparing for aging (Bode et al., 2007) and to promote proactive personality for academic achievement (Kirby et al., 2002). There are many other contexts to be explored, such as physical health or relationship success, that may benefit from interventions of this kind.

References

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 16.0) Chicago: SPSS, Inc; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 16.0 User’s Guide. Chicago: SPSS; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:417–436. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode C, de Ridder DTD, Kuijer RG, Bensing JM. Effects of an intervention promoting proactive coping competencies in middle and late adulthood. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:42–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger NB. Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:525–537. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Bedi G. The relationship between coping style and affect in recovering cardiac patients. Current Research in Social Psychology. 2001;6:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Sanna LJ. Optimism, pessimism, and positive and negative affectivity in middle-aged adults: A test of a cognitive-affective model of psychological adjustment. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:524–531. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and supression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:296–325. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Semegon AB, Schwarzer R. Assessing attention control in goal pursuit: A component of dispositional self-regulation. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2006;86:306–317. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8603_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Y, Yang M, Zhou Y, Zhang Y. The two-factor structure of future-oriented coping and its mediating role in student engagement. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:851–863. [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass E, Fiksenbaum L, Eaton J. The relationship between coping, social support, functional disability and depression in the elderly. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 2006;19:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass E, Schwarzer R, Jakubiec D, Fiksenbaum L, Taubert S. The Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI): a multidimensional research instrument; Paper presented at the 20th international conference of the stress and anxiety research society (STAR); Cracow, Poland. 1999. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass ER. Proactive Coping and Quality of Life Management. In: Fydenberg E, editor. Beyond Coping: Meeting Goals, Visions and Challenges. London: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass ER, Marques SM, de Ridder M, Behl S. Positive coping and mastery in a rehabilitation setting. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2005;28:331–339. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito TA, Cacioppo JT. Variations on a human universal: Individual differences in positivity offset and negativity bias. Cognition and Emotion. 2005;19:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling: A researcher’s guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby EG, Kirby SL, Lewis MA. A study of the effectiveness of training proactive thinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:1538–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Ouwehand C, de Ridder DTD, Bensing JM. Situational aspects are more important in shaping proactive coping behavior than individual characteristics: A vignette study among adults preparing for aging. Psychology and Health. 2006;21:809–825. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. The psychology of physical symptoms. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Taubert S. Tenacious goal pursuits and striving toward personal growth: Proactive coping. In: Fydenberg E, editor. Beyond Coping: Meeting Goals, Visions and Challenges. London: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskul AK, Greenglass ER. Psychological well-being in a Turkish-Canadian sample. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 2005;18:269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]