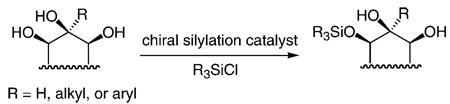

Catalysts that promote site-selective modification of poly-functional molecules can be of significant utility in selective chemical synthesis.[1] Of particular importance are chiral catalysts that initiate enantioselective functionalization of polyoxygenated molecules[2]—entities commonly found among biologically active agents. Herein, we present methods for the enantioselective silylations[3] of acyclic and cyclic 1,2,3-triols [Eq. (1)]; the transformations are promoted by a readily available small-molecule catalyst and afford silyl ethers that bear a neighboring diol moiety in up to > 99: < less than 1 e.r. (> 98% ee). Enantiomerically enriched silyl-protected triols obtained by the protocols described in this report cannot be selectively prepared by catalytic or stoichiometric dihydroxylations[4] (including the directed variants).[5] The utility of the new catalytic processes is demonstrated in the context of enantioselective total syntheses of cleroindicins D, F, and C, natural products isolated from Clerodendum indicum, a plant used in China to battle malaria and rheumatism.[6, 7]

|

(1) |

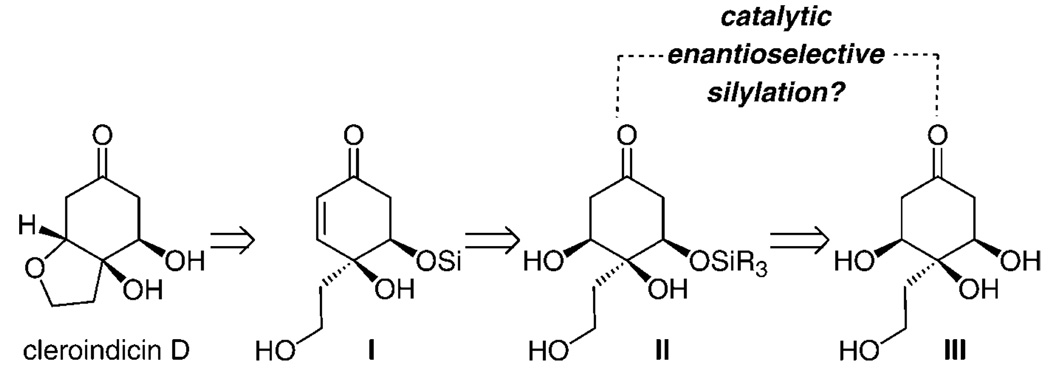

Our interest in developing methods for the enantioselective silylation of triols was inspired in part by a retrosynthesis of cleroindicin D, shown in Scheme 1. We envisioned that intramolecular conjugative cyclization of enone I (Scheme 1) would afford the target hydrobenzofuran. Enantiomerically enriched I would be prepared through a selective β-elimination by β-hydroxy enone II, which, in turn, could be accessed through site- and enantioselective silylation of tetraol III.

Scheme 1.

A retrosynthesis for cleroindicin D. Si=trialkylsilyl group.

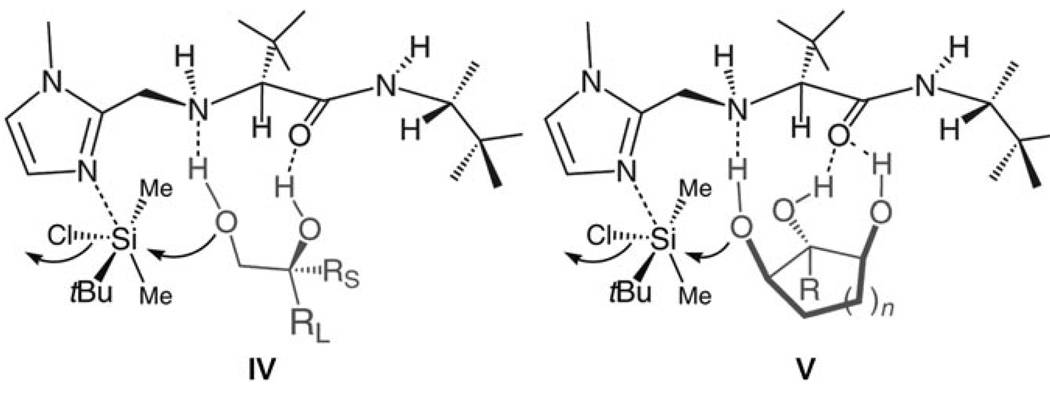

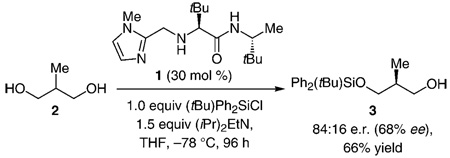

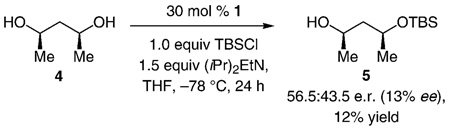

On the basis of the previously proposed mechanistic models,[3a] enantioselective conversion of III into II (Scheme 1) might involve the association of an amino-acid-based catalyst (e.g., 1) with either a 1,2-diol or 1,3-diol moiety through H bonding. Whereas silylations of cyclic as well as acyclic 1,2-diols have largely proven to be highly selective (> 90:10 e.r.), the related transformations of 1,3-diols can proceed with inferior selectivity; the two examples shown in Equation (2) and Equation (3) are illustrative. Thus, a complication regarding reactions of 1,2,3-triols is whether the 1,2-diol (high selectivity) or the 1,3-diol moiety (potentially inferior selectivity) more predominantly associate with the catalyst through H bonding.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

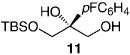

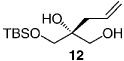

On the basis of the above considerations, we began our studies by investigating the reactions of meso acyclic 1,2,3-triols bearing a central tertiary alcohol. As illustrated in entries 1–3 of Table 1,[8] substrates containing large alkyl substituents are silylated with high enantioselectivity (96.5:3.5 to > 99: < 1 e.r.) to afford the desired monosilylated diols 6–8 in 78–85% yield after purification. The reactions of the corresponding aryl-substituted triols (entries 4–6, Table 1) are equally efficient and enantioselective. The silylation process shown in entry 7 of Table 1, involving a triol that bears a less sterically demanding allyl substituent, proceeds with equal efficiency but with a lower enantioselectivity (12 formed in 94.5:5.5 e.r.). Additional diminution of the selectivity in the silylation depicted in entry 8 of Table 1 (13 obtained in 75:25 e.r.) underlines the influence of the size of the central carbinol substituent on the degree of the enantiodifferentiation.[9] The reversal of the selectivity observed for diol product 13 (entry 8, Table 1) is likely because of the smaller size of the methyl substituent versus the hydroxy methylene unit (versus entries 1–7, Table 1 where alkyl and aryl substituents are larger than CH2OH; see Scheme 2 for mechanistic models). The findings shown in Table 1, in view of previous observations regarding reactions of l,2-[3] and 1,3-diols [see Eq. (1) and Eq. (2)], suggest that the silylation of triols proceed predominantly via complexes established through H bonding between the chiral catalyst and the two adjacent alcohols of the substrate.

Table 1.

Enantioselective silylation reactions of acyclic triols.[a]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Product | T [°C] | t [h] | Yield [%][b] | e.r.[c] | ee [%][c] |

| 1 | −30 | 96 | 78 | 96.5:3.5 | 93 | |

| 2 | −30 | 96 | 85 | 97:3 | 94 | |

| 3 | −30 | 96 | 81 | >99:<1 | >98 | |

| 4 | −50 | 120 | 70 | >99:<1 | >98 | |

| 5 |  |

−50 | 120 | 68 | 97.5:2.5 | 95 |

| 6 |  |

−50 | 120 | 75 | 98:2 | 96 |

| 7 |  |

−50 | 120 | 62 | 94.5:5.5 | 89 |

| 8 | −50 | 120 | 57 | 75:25 | 50 | |

Conditions: 1.0m in diol, 1.5 equiv DIPEA, 1.5 equiv TBSCl; > 98% primary silyl ether observed in all cases.

Yield of isolated product after purification.

Enantiomeric ratios and ee values determined by CLC or HPLC analysis (see the Supporting Information for details). TBS=tert-butylsilyl; DIPEA=N,N-diisopropylethylamine; Cy=cyclohexyl.

Scheme 2.

Proposed models for enantioselective silylations in Table 1 and Table 2.

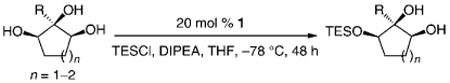

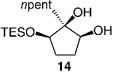

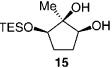

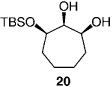

The less selective reactions of triols which contain a linear alkyl substituent at the central carbinol site (e.g., 12 in entry 7, Table 1), did not bode well for the projected plans for total syntheses of the cleroindicins (Scheme 1). Catalytic enantio-selective silylations of related cyclic triols, summarized in Table 2, however, demonstrate that the desired monosilylated cyclic diols 14−16 are isolated in 60–85% yield and with >99:< 1 e.r. (>98 %ee) regardless of the size of the central alkyl group.[10] Notably, the silylations in Table 2 are performed with TESCl (versus TBSCl); reactions of this set of relatively hindered carbinols must be performed with a less sterically demanding silylating agent to achieve maximum efficiency.

Table 2.

Enantioselective silylation reactions of cyclic triols.[a]

Conditions: 0.5m in diol, 1.5 equiv DIPEA, 1.25 equiv TESCl; >98% secondary silyl ether product obtained in all cases.

See Table 1. TES = triethylsilyl.

Two trends regarding enantioselective silylations of acyclic and cyclic triols shown in Table 1 and Table 2 are noteworthy: 1) Reactions of acyclic and cyclic substrates proceed with the opposite sense of asymmetric induction (e.g., 12 in Table 1 versus 14 in Table 2). Such findings can be rationalized by the modes of reaction involving complexes IV and V as illustrated in Scheme 2. The sense and level of enantiodifferentiation in the transformations of acyclic triols are likely controlled by the complexation of the catalyst and the substrate in a manner which leads to minimal unfavorable steric repulsion (large substituent, RL, positioned away from the amino-acid-based structure). The suggested scenario is consistent with the trend that higher selectivities require the presence of a more sizeable alkyl or aryl substituent (e.g., compare entries 1−3 to 7−8 in Table 1). In contrast, enantioselective silylations of cyclic triols in Table 2 might be largely governed by the exo mode of substrate–catalyst association, as depicted in V (Scheme 2). The relative insensitivity of the enantioselectivity to the size of the central carbinol substituent in the silylations shown in Table 2, versus the reactions in Table 1, supports the above proposal. 2) The exceptional enantiopurity with which the six-membered ring 16 (entry 3, Table 2) is obtained (> 99: < 1 e.r., > 98% ee) is in contrast to the inferior level of enantioslectivity with which the corresponding silylation of cyclohexane-l,3-diol proceeds (38% ee under with TBSCl).[11] Such findings underscore the higher efficiency with which 1,2-diols associate with the silylation catalyst as opposed to 1,3-diols. That is, although both modes of H bonding are illustrated in the proposed model (V in Scheme 2), it is likely that catalyst–substrate association involving H bonding with the central carbinol unit is more critical to the high selectivity.

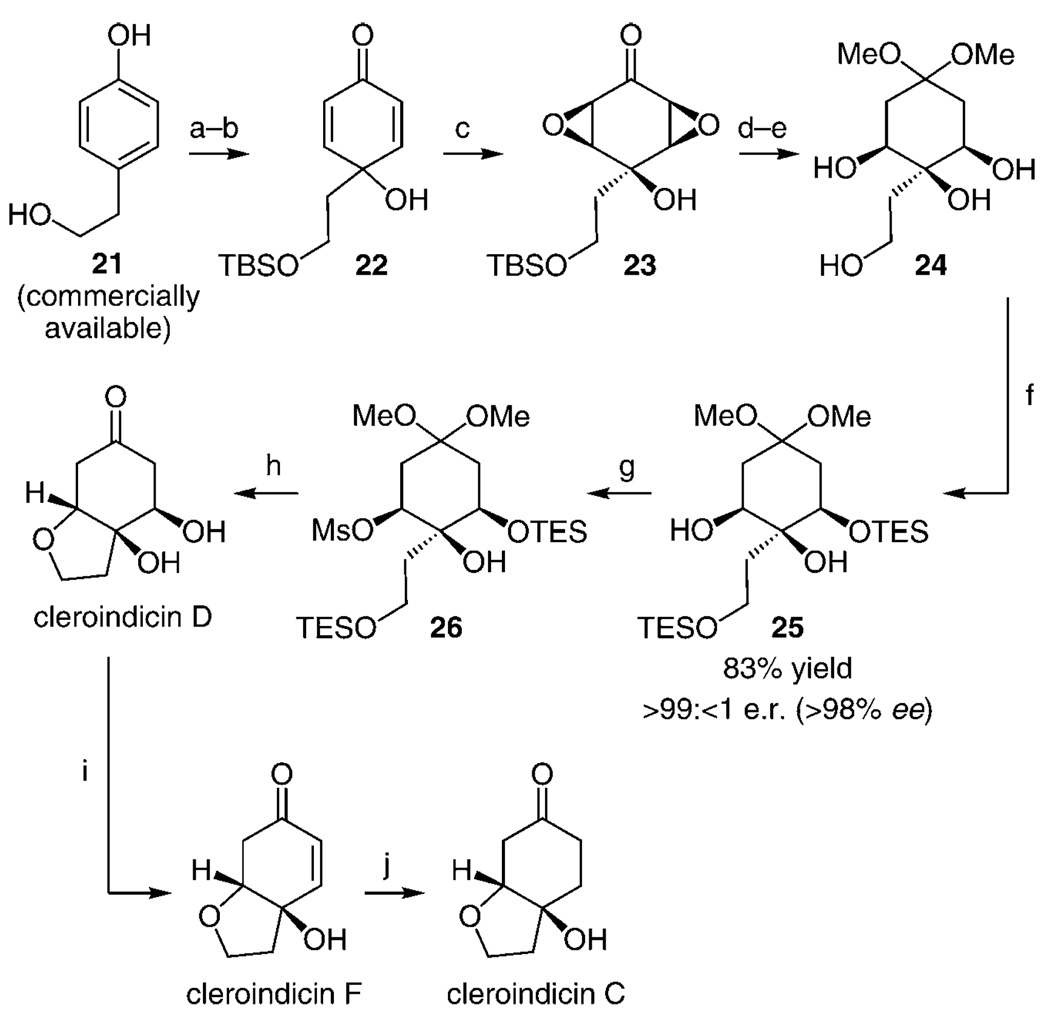

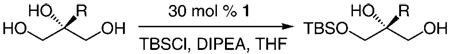

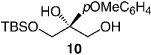

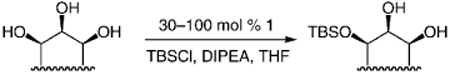

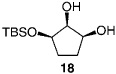

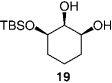

We next turned our attention to catalytic desymmetrizations of all-secondary l,2,3-triols.[12] Such transformations, which deliver products used in the enantioselective synthesis of natural products,[13] present an additional challenge, since the three carbinols units now reside in a less differentiable environment. Enantioselective silylations of all-secondary triols, summarized in Table 3, uniformly proceed with exceptional selectivity (from 98:2 to > 99: < 1 e.r.), regardless of the substrate ring size; the outcomes of these transformations are therefore consistent with the mechanistic proposals outlined above (Scheme 2). The transformation illustrated in entry 3 of Table 3 requires 100 mol% of the chiral catalyst and a relatively elevated temperature (0°C) because of the low solubility of the cyclohexyl triol.[14] Notably, processes shown in Table 3 proceed with exceptional site-selectivity: less than 2% of the product is derived from the silylation of the central secondary alcohol is observed.

Table 3.

Enantioselective silylation reactions of all-secondary triols.[a]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Product | Mol% of l | T [°C] | t[h] | Yield [%][b] | e.r.[c | ee[%][c] |

| 1 |  |

30 | −50 | 120 | 72 | >99:<1 | >98 |

| 2 |  |

30 | −30 | 96 | 70 | 98:2 | 96 |

| 3 |  |

100 | 0 | 24 | 51 | >99:<1 | >98 |

| 4 |  |

30 | −30 | 120 | 65 | >99:<1 | >98 |

See Table 1; <2% silylation of the central hydroxy group observed in all cases.

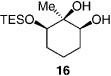

With the protocols for the enantioselective silylation of triols in hand, we turned our attention to the total syntheses of enantiomerically enriched cleroindicins D, F, and C (Scheme 3). We began by using a two-step sequence involving commercially available para-substituted phenol 21; protection of the primary alcohol and subsequent conversion into cyclic dienone 22 through oxidative dearomatization[15] proceeds in 69% overall yield. Directed epoxidation of the two electrophilic alkenes in 22 proceeded with exceptional diastereoselectivity,[16] affording bisepoxide 23 in 92% yield after silica gel chromatography. Site-selective reduction of the two electronically activated C–O bonds in 23[17] and conversion into the derived dimethylacetal, which proceeds with concomitant removal of the primary silyl ether, delivered tetraol 24. Enantioselective silylation of 24 in the presence of 20 mol% 1 and 2.25 equivalents of TESCl led to the formation of 25 in > 99: < 1 e.r. and 83% yield. Subsequent conversion into mesylate 26 was performed under standard conditions, affording the desired product in 92% yield. Treatment of silyl ether 26 with five equivalents of HCl in aqueous THF (0°C→22°C) for four hours led to the formation of enantiomerically pure cleroindicin D, which was isolated in 45% overall yield and > 99: < 1 d.r. Conversion of 26 into the target molecule under the aforementioned acidic conditions constitutes a five-step sequence involving removal of the two silyl groups, conversion of the acetal into the ketone, and β-elimination of the mesylate group to furnish the requisite enone, which undergoes intramolecular conjugate addition to afford the furan ring of the natural product. As also illustrated in Scheme 3, cleroindicin D can be easily and efficiently converted into cleroindicins F and C.

Scheme 3.

Enantioselective total syntheses of cleroindicins D, F, and C. a) 1.1 equiv of TBSCl, 1 equiv of imidazole, THF, 0°C, 1 h. b) 1.2 equiv of PhI (OAc)2, CH3CN/H2O (1:1), 0°C, 20 min; 69% overall yield for 2 steps, c) 10.0 equiv of H2O2, 8.0 equiv of K2CO3, 0°C, 6 h; 92% yield, d) 1 atm. H2, 4 wt% PtO2, 22°C, 12 h. e) 10 mol% ppTs, MeOH, THF, −78°C, 48 h; 83% yield, f) 20 mol% 1, 2.25 equiv of TESCl, 2.5 equiv of DIPEA, THF, −78°C, 48 h; 83% yield, g) 2.5 equiv of MsCl, 3.5 equiv DIPEA, CH2Cl2, 0°C→22°C; 92% yield, h) 5.0 equiv HCl, THF/H2O (1:1), 0°C→22°C, 4 h; 45% yield, i) 1.2 equivalents of MsCl, 2.2 equiv of DIPEA, CH2Cl2, 0°C, 16 h; 92% yield, j) 1 atmosphere H2, 50% wt Pd/C, MeOH, 12 h; > 98% yield. THF = tetrahydrofuran; ppTs = pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate; Ms = methanesulfonyl.

We thus demonstrate that the range of substrates that efficiently undergo catalytic enantioselective silylation extends beyond the previously reported 1,2-diols.[3] The processes detailed above deliver otherwise difficult-to-access polyoxygenated small molecules of exceptional enantiomeric purity, significantly expanding the utility of this practical class[3] of catalytic reactions. Development of new and more effective chiral silylation catalysts and additional methods for enantioselective silylations are subjects of ongoing studies.

Footnotes

Financial support was provided by the NIH (GM-57212) and Z.Y. acknowledges support as a LaMattina Graduate Fellow. We are grateful to Dr. Yu Zhao and Jason Rodrigo (Boston College) for experimental assistance and helpful discussions. Mass spectrometry facilities at Boston College are supported by the NSF (DBI-0619576).

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.200805338.

References

- 1.For an application of enantioselective catalysis to site- and enantioselective synthesis, see: Lewis CA, Miller SJ. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:5744–5747. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 5616–5619.

- 2.For copper-catalyzed enantioselective benzoylation reactions of 1,2,3-triols, see: Jung B, Hong MS, Kang SH. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:2670–2672. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2616–2618. Jung B, Kang SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1471–1475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607865104.

- 3.For previous reports regarding catalytic enantioselective silylation reactions, see: Zhao Y, Rodrigo J, Hoveyda AH, Snapper ML. Nature. 2006;443:67–70. doi: 10.1038/nature05102. Zhao Y, Mitra AW, Hoveyda AH, Snapper ML. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:8623–8626. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703650. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8471–8474.. For an overview of enantioselective silylation processes, see: Rendler S, Oestreich M. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:254–257. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 248–250.

- 4.Catalytic enantioselective dihydroxylations of cyclic allylic alcohols afford the derived anti diastereomers. See: Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483–2547.

- 5.Hydroxy-directed dihydroxylation reactions of cyclic allylic alcohols afford meso triols diastereoselectively. See: Donohoe TJ, Blades K, Moore PR, Waring MJ, Winter JJG, Helliwell M, Newcombe NJ, Stemp G. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:7946–7956. doi: 10.1021/jo026161y.

- 6.Tian J, Zhao Q-S, Zhang H-J, Lin Z-W, Sun H-D. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:766–769. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For a total synthesis of rac-cleroindicin D, culminating in a structural revision of the natural product, see: Barradas S, Carreño MC, González-López M, Latorre A, Urbano A. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5019–5022. doi: 10.1021/ol702236e.

- 8.For details regarding preparation of triol substrates, see the Supporting Information.

- 9.Varying amounts of bis-silylation products are formed in reactions involving substrates that bear a smaller substituent at the central carbinol unit. For example, 8%, 32%, and 36% bissilyl product is isolated from the transformations shown in entries 3, 7, and 8 of Table 1, respectively. Such bis-silylations increase the enantiomeric purity of the chiral monosilyl products.

- 10.For enantioselective syntheses of a related cyclohexane-based triols by enzymatic resolution of meso-2-(2-propynyl)cyclohexane-1,2,3-triol, see: Matsumoto T, Konegawa T, Yamaguchi H, Nakamura T, Sugai T, Suzuki K. Synlett. 2001:1650–1652.

- 11.It should be noted that 15% of bis-silylated product is also obtained in the enantioselective silylation of 1,2,3-triol 16; this byproduct is easily removed by using silica gel chromatography. Such a process serves as a “correcting” mechanism in the catalytic process to remove the minor product enantiomer.

- 12.For enantioselective syntheses of cyclohexane-1,2,3-triols through enzymatic kinetic resolution, see: Dumortier L, Van der Eycken J, Vandewalle M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:3201–3204.

- 13.For example, see: Deruytterre X, Dumortier L, Van der Eycken J, Vandewalle M. Synlett. 1992:51–52. Vadivel SK, Vardarajan S, Duclos RI, Jr, Wood JT, Guo J, Makriyannis A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:5959–5963. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.064.

- 14.In the presence of 30 mol% 1 (0°C) and after 72 h of reaction time, silyl ether 19 is isolated in 32% yield and 98.5:1.5 e.r. (97% ee).

- 15.Felpin F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:409–412. [Google Scholar]

- 16. McKillop A, Taylor RJK, Watson RJ, Lewis N. Synlett. 1992:1005–1006.. For a review of hydroxyl-directed epoxidations, see: Hoveyda AH, Evans DA, Fu GC. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1307–1370.

- 17.Lei X, Zaarur N, Sherman MY, Porco JA., Jr J Org. Chem. 2005;70:6474–6483. doi: 10.1021/jo050956y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]