Abstract

Sonic hedgehog (Shh) is a secreted morphogen necessary for the production of sidedness in the developing embryo. In this study, we describe the morphology of the atrial chambers and atrioventricular junctions of the Shh null mouse heart. We demonstrate that the essential phenotypic feature is isomerism of the left atrial appendages, in combination with an atrioventricular septal defect and a common atrioventricular junction. These malformations are known to be frequent in humans with left isomerism. To confirm the presence of left isomerism, we show that Pitx2c, a recognized determinant of morphological leftness, is expressed in the Shhnull mutants on both the right and left sides of the inflow region, and on both sides of the solitary arterial trunk exiting from the heart. It has been established that derivatives of the second heart field expressing Isl1 are asymmetrically distributed in the developing normal heart. We now show that this population is reduced in the hearts from the Shh null mutants, likely contributing to the defects. To distinguish the consequences of reduced contributions from the second heart field from those of left–right patterning disturbance, we disrupted the movement of second heart field cells into the heart by expressing dominant-negative Rho kinase in the population of cells expressing Isl1. This resulted in absence of the vestibular spine, and presence of atrioventricular septal defects closely resembling those seen in the hearts from the Shh null mutants. The primary atrial septum, however, was well formed, and there was no evidence of isomerism of the atrial appendages, suggesting that these features do not relate to disruption of the contributions made by the second heart field. We demonstrate, therefore, that the Shh null mouse is a model of isomerism of the left atrial appendages, and show that the recognized associated malformations found at the venous pole of the heart in the setting of left isomerism are likely to arise from the loss of the effects of Shhin the establishment of laterality, combined with a reduced contribution made by cells derived from the second heart field.

Keywords: atrioventricular septal defects, heart, isomerism, second heart field, Sonic hedgehog, visceral heterotaxy

Introduction

Formation of the abdominal and thoracic organs in a symmetrical pattern, rather than in their usual lateralized arrangement, is often described as visceral heterotaxy. In humans, it is the most complex combination of congenital cardiac malformations that are found in this setting (Van Mierop & Gessner 1972). It is now recognized that the syndrome of visceral heterotaxy can be divided into the subsets of right and left isomerism (Uemura et al. 1995). Right isomerism is associated with the presence of two morphologically right atrial appendages that are mirror-images of each other, multiple anomalies of the systemic and pulmonary venous connections, formation of a common atrioventricular junction rather than separate right and left atrioventricular junctions, and abnormal ventriculo-arterial connections. There is usually pulmonary stenosis or atresia. Left isomerism, characterized by paired morphologically left atrial appendages, in contrast, tends to be associated with less severe abnormalities, usually with concordant ventriculo-arterial connections, although a common atrioventricular junction is frequently observed (Smith et al. 2006). Answering the question of why such malformations are associated with symmetrical rather than lateralized arrangement of the organs will cast light on the ontogeny of these defects not only in the setting of heterotaxy, but also in congenitally malformed hearts in general. Mice with unequivocal right isomerism have now been produced by knock-out of genes that determine leftness, such as Pitx2 and Cited2 (Bamforth et al. 2004; Gage et al. 1999). To the best of our knowledge, however, only lefty-1 null embryos (Meno et al. 1998), and the Shh null embryos that we describe here, reproducibly and consistently model left isomerism within the heart.

Sonic hedgehog (Shh), a secreted signalling molecule, acts to maintain the left-sided expression of the genes responsible for producing morphological left-sidedness during establishment of the body plan and patterning of the organs in early development. It is expressed in several embryonic organizing centres, including the ventral neural tube, the notochord and the limbs, and also within the endodermal tissues of the branchial arches and foregut, which lie in close proximity to the developing heart (Marti et al. 1995). Loss of Shh signalling activity in the mouse is also known to disrupt normal left–right patterning, so that left-sided genes, such asNodal, Lefty2 and Pitx2, are ectopically expressed on the right side (Tsukui et al. 1999). Shh null mice develop a number of severe defects during embryonic development, including holoprosencephaly, cyclopia, absence of distal limb structures and absence of the spinal column and much of the ribs. These defects are first apparent from E9.5, although many survive to the latter stages of gestation (Chiang et al. 1996). Previous analyses of the cardiovascular phenotype in Shh null mutants have shown a shortened and unseptated ouflow vessel, abnormal cardiac looping, and disturbance of the pharyngeal arch arteries (Washington Smoak et al. 2005). In addition, atrioventricular septal defects with common atrioventricular junction have been observed (Goddeeris et al. 2008). These malformations have been related to disruption of migration of cells from the neural crest, and perturbations of the con- tribution made to the forming heart by the second cardiac linage, also known as the second, or anterior, heart field (Goddeeris et al., 2007, 2008; Washington Smoak et al. 2005).

As Shh plays a key role in determining the left–right patterning of the developing embryo, and malformations seen in the forming atrioventricular region (Tsukui et al. 1999) are similar to those in humans with left isomerism, we have investigated whether the Shhnull mutant exhibits left isomerism. In their analysis of the Mef2C-AHFcre;Smoflox/– mice, Goddeeris et al. (2008) were able to show that specific loss of Shh signalling in cells that had expressed this Cre-linked promoter were sufficient to produce atrioventricular septal defects. This was attributed by them to a failure in expansion of the dorsal mesenchymal projection, also known as the vestibular spine. Our studies, which were carried out entirely within the Shh null mutants, have confirmed these findings, but have also extended them by providing a full characterization of the morphological abnormalities found at the venous pole of the heart. Our findings reveal that the Shh null mice represent a fully penetrant model of isomerism of the left atrial appendages. We also show that reduced contributions from the second heart field contribute to the common atrioventricular junction, which is also part of the cardiac phenotype. We show, therefore, that the cardiac malformations seen in Shh null mice result from a combination of disturbances of laterality and disruption of the contribution from the second cardiac lineage.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Shh−/−embryos used in this study were obtained by inter-crossing Shh+/– animals from the Shhneoline (Chiang et al. 1996), in which exon 2 and a proportion of the flanking introns of the Shh gene are replaced by a neo cassette to produce a non-signalling protein. No developmental defects were found in over 100 Shh+/– embryos, and these were used interchangeably with Shh+/+ as controls. ROCK CAT-DN mice (Kobayashi et al. 2004) in which a dominant-negative ROCK construct is expressed in the presence of Cre, were obtained from the RIKEN Biological Resource Centre, Japan. These mice were inter-crossed with Isl1-cre (Yang et al. 2006) and the ROSA 26R reporter line (Soriano, 1999) to generate embryos in which both ROCK1 and ROCK2 are knocked down in theIsl1-expressing cells derived from the second heart field, and in which lineage tracing can be performed. Genotyping was carried out as described (Chiang et al. 1996; Kobayashi et al. 2004).

Beta-galactosidase detection, immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Embryos were processed for X-gal staining (Loughna & Henderson, 2007) and immunohistochemistry was performed using an anti-Isl1 antibody (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) as described previously (Phillips et al. 2005). Wholemount and slide in situ hybridization (Phillips et al. 2005) was carried out using a Pitx2c probe (Campione et al. 1999). Experiments were repeated a minimum of three times on an average of six embryos per genotype, with appropriate stage-matched controls.

Optical projection tomography

Embryos were prepared, fluorescently scanned and reconstructed according to previously described protocols (Lindsay et al. 2005). Optical sections were painted using the MAPaint programme. UBYTE data were fed into the programme, then specific structures were manually painted on each optical section of the reconstruction. Once painted, colour domains were loaded into the programme mavxp to create three-dimensional models of the painted structures.

Results

Shh null mutants have incomplete looping and persistent dorsal mesocardial connection

The early heart tube forms on the surface of the embryonic mesoderm. Its mesentery, the dorsal mesocardium, participates in the formation of the atrial septal complex, giving rise to the mediastinal myocardium and the vestibular spine (Moorman et al. 2007). During development, the larger part of the dorsal mesocardium breaks down, such that the heart tube remains tethered to the pharyngeal mesenchyme only at the venous and arterial poles (Webb et al. 1998b). This is an essential element in normal looping, permitting the heart to bend and rotate, and bringing the developing outflow tract into alignment with the midpoint of the developing atrioventricular canal.

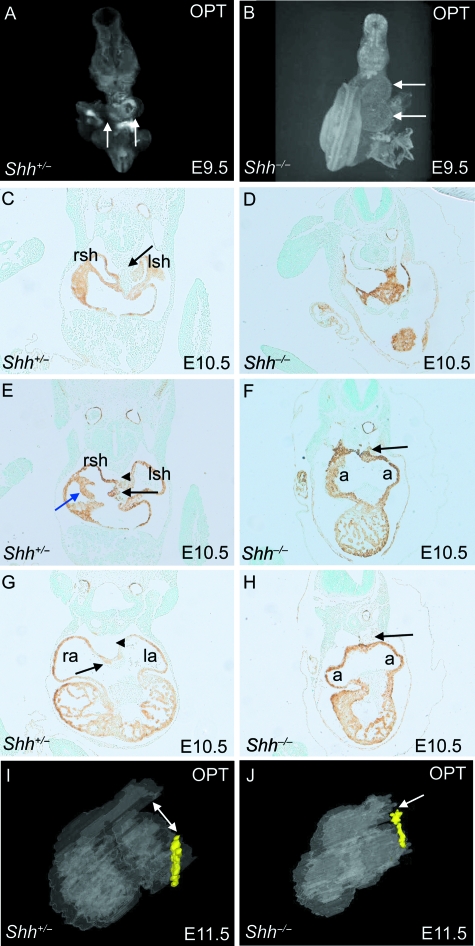

In Shh−/− embryos, there is incomplete, or ventral, looping of the heart (Fig. 1A,B). Sectioning of these embryos showed that whereas the dorsal mesocardium had broken down throughout the length of the heart tube, except at the systemic venous sinus and the outflow region in all control embryos at E10.5, there was an abnormal persistence of the dorsal mesocardium in all 13 stage-matched mutants examined (Fig. 1F,H). In nine of these 13 embryos, there was evidence of a small breakage in the dorsal mesocardium near the outflow tract. This persistence of the dorsal mesocardium was also seen in 20 of 22 embryos studied from days E11.5 through E15.5 (Fig. 1J, compare to Fig. 1I), indicating that the separation of the heart from the mesocardium is not simply delayed. This failure of the breakdown of the dorsal mesocardium is likely to contribute to the disruption of cardiac looping in Shh−/− null embryos.

Fig. 1.

Persistence of the dorsal mesocardial connection in Shh null embryos. (A,B,I,J) optical projection tomography (OPT)-derived images. (C–H) Sectioned embryos were immuno-labelled using an anti-αSMA antibody (brown). (A,B) OPT images of whole embryos at E10.5 show that the heart is abnormally looped in the Shh−/− embryos. White arrows denote the apex of the ventricles, with ventral looping apparent in the Shh−/− embryo. In addition, the heart is displaced to the left in the Shh−/− embryo. (C,E,G) Control embryo at E10.5 showing normal formation of the venous pole. At this stage, the dorsal mesocardium can be seen at the posterior pole of the heart (black arrow in C). In addition, the vestibular spine and the venous valves can also be seen (black and blue arrows, respectively, in E). In a four-chambered view of the wild-type heart, the dorsal mesocardium has broken down (arrowhead in G) and the primary atrial septum is beginning to form (arrow in G). (D,F,H) The dorsal mesocardium persists along the full length of the heart tube in Shh−/− embryos at E10.5 (arrows in F and H). In addition, the atria are small and abnormally shaped and the venous valves are absent. (I,J) At E11.5, OPT reconstructions of the heart (shown from the left side) show that the dorsal mesocardium (yellow) is persistent in the Shh−/− embryos except for a small region close to the outflow tract (arrow in I), but has broken down in the wild-type embryos (double-headed arrow). a, indeterminate atrial chamber; la, left-sided atrium; lsh, left sinus horn; ra, right-sided atrium; rsh, right sinus horn. that the dorsal mesocardium (yellow) is persistent in the Shh−/− embryos except for a small region close to the outflow tract (arrow in I), but has broken down in the wild-type embryos (double-headed arrow). a, indeterminate atrial chamber; la, left-sided atrium; lsh, left sinus horn; ra, right-sided atrium; rsh, right sinus horn.

Shh−/− embryos have isomeric left atrial appendages

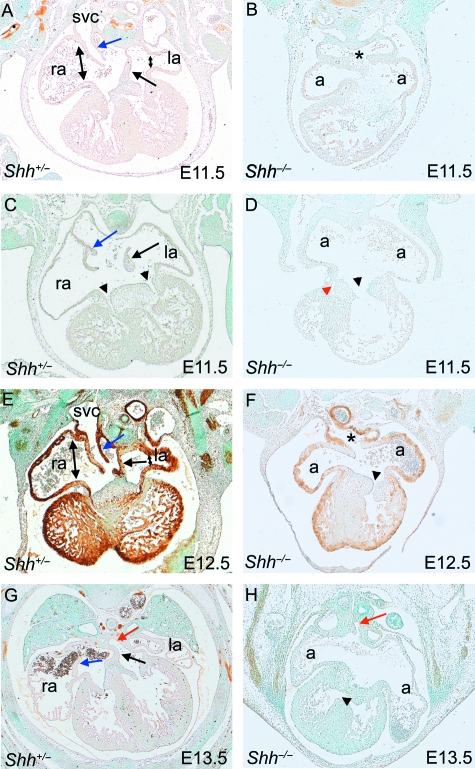

At the earliest stages of development, systemic blood returns to the heart through the right and left horns of the systemic venous sinus, which at E10.5 flank the normally persisting dorsal mesocardium (arrow in Fig. 1C). By E11.5, the ingrowth of the septal components, including the vestibular spine and primary atrial septum (Fig. 2A, black arrow), in conjunction with ballooning of the atrial appendages, have begun to produce the characteristic features of morphologically right and left atrial chambers. In the mouse, as in the normal human heart, the systemic venous sinus drains exclusively to the morphologically right atrium, and there are well-formed valves at its junction with the remainder of the right atrium (Fig. 2A,C,E,G, blue arrows). The pulmonary vein is committed to the developing morphologically left atrium by fusion of the primary atrial septum and the vestibular spine with the atrioventricular cushions (red arrow in Fig. 2G). Importantly, the right and left atrial appendages are distinctly different by E11.5. The right atrial appendage has a broad connection to the body of the atrium (large double-headed arrows in Fig. 2A,E). In contrast, the left atrial appendage is tubular, with a small orifice connecting to the body of the atrium (small double-headed arrow in Fig. 2A,E).

Fig. 2.

Venous connections in Shhembryos. (A–F) The systemic venous tributaries feed into a pouch-like confluence dorsal to the atrial chambers in Shh−/− embryos at E11.5 and E12.5 (asterisk in B,F) and the venous valves are absent. In contrast, the superior vena cava feed into the right atrium in wild-type embryos (A,E) with valve structures clearly seen (blue arrows in C,E). Although an intact primary atrial septum is seen in the wild-type embryos (black arrows in A,E), this is absent in the Shh−/− embryos (B,D,F). Whereas right and left atrioventricular connections can be seen in control embryos (arrowheads in C), a common atrioventricular canal is found in Shh−/− embryos (black arrowhead in D), in continuity with the left ventricle. Although in some cases a slit can be seen at the right side of the atrioventricular junction, this is blocked by muscle from the underlying ventricular septum (red arrowhead in D). Double-headed arrows in A and E show the broad right atrial chamber and the tubular right atrial chamber. (G,H) At E11.5, the pulmonary vein enters into an approximately midline position in the unseptated Shh−/− atrial chambers, but into the left ventricle in wild-type embryos (red arrows). A ventricular septal defect can be seen in the Shh−/− embryo. a, indeterminate atrial chamber; la, left atrium; ra, right atrium; svc, superior vena cava.

With these features in mind we analysed the atrial morphology of the Shh null embryos at E11.5–E13.5. In Shh−/− embryos, rather than draining exclusively to the right atrium, we observed bilateral systemic venous tributaries in the Shh−/− hearts, draining to a pouch-like confluence at the position in the normal heart occupied by the horns of the systemic venous sinus (Fig. 2B,F, asterisks). None of the 38 Shh null embryos examined showed any evidence of formation of venous valves. From the pouch-like confluence, the systemic venous blood drained centrally into a common atrial chamber (Fig. 2B), rather than draining to the left atrium. Thus, as suggested by Tsukui et al. (1999), the atrium is completely unseptated in Shh−/− embryos, lacking both the primary atrial septum and the vestibular spine. The pulmonary vein remains a midline structure (Fig. 2H, red arrow, compare to Fig. 2G). This arrangement was seen in all embryos examined at E11.5, with this pattern remaining unchanged at later stages of development (Table 1). When compared with stage-matched controls, the atrial appendages in the mutant hearts were mirror-images of each other, although their morphology was indeterminate, resembling neither the right or left atrium of wild-type embryos closely (Fig. 1F,H, compare with Fig. 1E,G). Thus, Shh−/− embryos, whilst showing indeterminate atrial appendage morphology, have lost the defining feature of the right atrium, specifically the draining caval veins and their associated venous valves.

Table 1.

Cardiac defects in Shh−/−embryos and fetuses

| Number with phenotype/Shh−/− fetuses |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | E10.5 | E11.5 | E12.5 | E13.5 | E14.5 | E15.5 | Total |

| Looping | |||||||

| Right-sided and ventrally looped | 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) |

| Dorsal mesocardium | |||||||

| Completely persisting | 4 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 18/35 (52%) |

| Partially persisting* | 9 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15/35 (43%) |

| Not persisting† | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/35 (5.7%) |

| Inflow tract | |||||||

| Abnormal inflow tract | 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) |

| Central systemic inflow | 10 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) |

| 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) | |

| Absence of true venous valves in right atrium | |||||||

| Atria | |||||||

| ASD‡ | 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) |

| Symmetrical appearance | 13 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 37/38 (98%) |

| Rounded, abnormal appearence | 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) |

| Atrioventricular (AV) canal | |||||||

| Large, left-sided AV channel connecting left ventricle | 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) |

| Small, secondary channel unconnected to the right ventricle | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 25/25 (100%) |

| Ventricles | |||||||

| VSD§ | – | – | – | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8/8 (100%) |

| Outflow tract | |||||||

| Unseptated/Shortened¶ | 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 38/38 (100%) |

Each Shh−/− embryo analysed at a given stage was compared to a wild-type littermate to assess morphological differences. Wild-type embryos display right-sided looping, breakdown of the dorsal mesocardium, right-sided systemic inflow into the right atrium through visible venous valves, atria that are asymmetrical in appearance and that are divided by the atrial septum, two atrioventricular channels connecting to the left and right ventricles, closure of the ventricular foramen by E13.5, complete septation of the outflow tract by E12.5, and equal-sized dorsal aortae leading to a left-sided aortic arch at later embryonic stages. Where the total number of animals analysed is less than 38, hearts were omitted from the study as they were damaged or otherwise unsuitable for analysis of the given phenotype.

Partially persisting beyond the level seen in control embryos.

Dorsal mesocardium persists in a similar pattern to controls.

Embryos at E11.5 and under (stages where atrial septation is normally incomplete) were assessed for absence or abnormal development of the atrial septal components.

Presence of a VSD was assessed at E13.5 and over.

Embryos at E10.5 were assessed for an absence of the AP septum in the aortic sac.

We also searched for evidence of the sinus node, known to be a component of the morphologically right atrium (Smith et al. 2006). In the wild-type embryos, analysis of histological sections revealed the sinus node at its expected location at the entrance of the superior caval vein to the right atrium. In contrast, we were unable to find any sinus nodal tissue in any of the Shh null embryos at any stage examined (data not shown). Such absence, or gross hypoplasia, of sinus nodal tissue is the rule in humans with isomerism of the left atrial appendages (Smith et al. 2006). Absence of the sinus node, therefore, supports our conclusion that, in the Shh−/− embryos, both atrial appendages have morphologically left identity.

Shh−/− embryos have double inlet left ventricle through a common atrioventricular valve

In the developing heart, the atrioventricular canal is the junction between the atrial and ventricular chambers. Remodelling of the atrioventricular cushions provides the basis for formation of the tricuspid and mitral valves, and physically separates the flow of blood into the right and left ventricles. This atrioventricular septation is initiated at E9.5 by formation of endocardial cushions superiorly and inferiorly within the canal. It is completed by E13.5, when these atrioventricular cushions fuse with each other, and also with the atrial and ventricular septal structures, forming the central mesenchymal mass (Webb et al. 1998a). In keeping with the study of Goddeeris et al. (2008), we found the atrioventricular canal to be abnormal in all 38 Shh−/− embryos examined from E10.5 onwards. The atrioventricular channel was wider than expected in the null embryos at E11.5. Rather than dividing so that each atrial chamber was joined separately to its respective ventricle, as in the stage-matched controls, the canal persisted as a single channel (Fig. 2D,F). Our detailed analysis of this region indicated further abnormalities. The flow from the unseptated atrial chamber was directed exclusively into the developing left ventricle (Fig. 2D, arrowhead). We found no direct communication between the atrial chamber and the developing right ventricle in any of the Shh−/− hearts, although a fissure on the right side of the atrioventricular cushions, at the site of anticipated formation of the tricuspid valve, was observed in all of the mutant hearts analysed beyond stage E11.5 (Fig. 2D, red arrowhead and Table 1). The potential channel from the fissure to the developing right ventricle was blocked by the developing muscular ventricular septum (Fig. 2D). At embryonic day E12.5 and beyond, when the common atrioventricular junction continued to drain to the morphologically left ventricle (Fig. 2F, arrowhead), the inter-ventricular foramen was maintained in all the Shh null embryos (Fig. 2H, arrowhead) as the only route for blood to gain access to the incomplete morphologically right ventricle in this setting of univentricular connection to a dominant left ventricle. With this spectrum of defects in mind, we set out to look at the earlier stages of development to identify the cause of these defects.

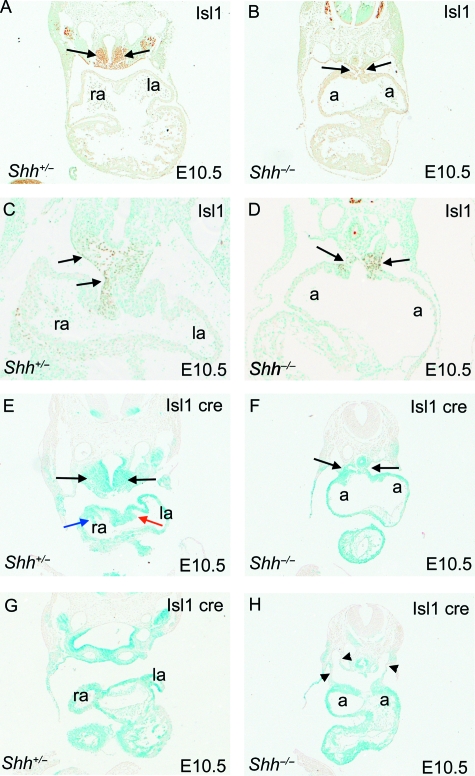

Reduction in Isl1-positive second heart field cells in Shh null embryos

We identified cells derived from the second cardiac lineage with immunohistochemistry, using an antibody raised against Isl1 (Dutton et al. 1999). In wild-type controls, Isl1-positive cells were seen to form a column that began in the pharyngeal mesoderm, passed behind the heart, and entered the developing atrium through the dorsal mesocardium (Fig. 3A,C, black arrows, and data not shown) (Snarr et al. 2007). Notably, more staining was observed on the right side of the dorsal mesocardium at this stage of development. Little Isl1 immunostaining was seen within the atrial chamber itself, except in the developing venous valves (data not shown). In stage-matched Shh−/− embryos, the domain of expression was markedly reduced (Fig. 3B,D, black arrows). Isl1-positive cells were also present in the dorsal mesocardium of Shh null embryos, including the persisting region (Fig. 3D, black arrows), although there was no evidence of asymmetrical distribution of this population.

Fig. 3.

Expression of Isl1 in Shh embryos. Isl1 immunostaining (brown) and β-gal staining of Isl1-cre;ROSA 26R embryos (blue). (A–D) Isl1-stained cells dorsal to the dorsal mesocardium are markedly reduced in Shh−/− embryos (black arrows, A–D) compared to stage-matched controls. Isl1 protein is expressed on both sides of the abnormally persisting region of the dorsal mesocardium in Shh−/− embryos (black arrow in D), but is asymmetrically localized in stage-matched controls. (E–H) β-gal staining of Isl1-cre;ROSA 26R embryos confirms the Isl1 immunostaining, showing thatIsl1-positive SHF cells dorsal to the heart are markedly reduced in Shh−/− embryos (black arrows in E,F). Note that the vestibular spine is also stained blue in control embryos, showing that it is derived from Isl1-positive derivatives (red arrow in E), as are the venous valves (blue arrows in E). In contrast, the abnormal pouch-like confluence into which the systemic venous tributaries feed in Shh−/− embryos, is not derived from Isl1-expressing cells (arrowheads in H), except at its junction with the atrial chambers. a, indeterminate atrial chamber; la, left atrium; ra, right atrium.

To fate map the Isl1-expressing cells within the heart, we inter-crossed Shh mice with the Isl1-Cre and ROSA 26R mouse lines (Soriano, 1999; Yang et al. 2006). The Isl1-Cre/+;R26R/+ (control) embryos examined at E10.5 demonstrated similar distributions of β-gal-positive cells as seen with the Isl1 antibody (Fig. 3E,G). The mesoderm ventral to the foregut (Fig. 3E, black arrows), dorsal mesocardium, and the vestibular spine (Fig. 3E, red arrow), as well as the venous valves (Fig. 3E, blue arrow), all had abundant β-gal-positive cells, indicating they were derived from the Isl1-expressing lineage. There was no evidence of asymmetry within the staining pattern, suggesting that the asymmetry seen in Isl1 antibody staining was temporally regulated. β-Gal staining was also found more broadly in the atria than was detected by Isl1 antibody labelling, representing cells that had expressed Isl1at earlier stages or by their precursors, but had down-regulated its expression by E10.5. Examination of the Isl1-positive lineage within the heart of Shhnull embryos showed there were fewer cells than in stage-matched controls at E10.5, particularly in the region ventral to the foregut (Fig. 3F). The atrial walls were β-gal-positive as in wild-type embryos, although, as in previous analyses, there was no evidence of the vestibular spine or venous valves. Notably, the pouch-like confluence into which the bilateral systemic tributaries drain before entering the common atrial chamber was not β-gal-positive (Fig. 3H, arrowheads), indicating that malformations are seen in structures that are not derived from theIsl1-expressing lineage.

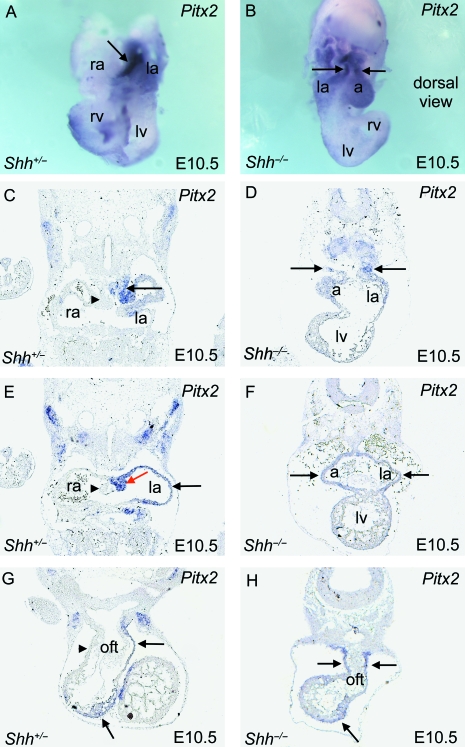

The heart in Shh null embryos has isomeric left identity defined by Pitx2 expression

Shh is produced by the notochord and the floor plate in the early embryo, and is thought to influence embryonic laterality by blocking the expression of left-sided genes across the midline of the embryo. Loss of Shh expression, therefore, is associated with the expression of left-sided genes on both sides of the embryo, and with the loss of right-sided genes from the right side of the embryo (Izraeli et al. 1999; Meyers & Martin, 1999; Tsukui et al. 1999). We carried out in situ hybridization, using the marker Pitx2, which labels cells in the left atrial appendage, the left atrial roof, and the midline of the atrial chambers, to establish a definition of molecular leftness in the forming heart. As only the Pitx2c isoform is asymmetrically expressed in the heart, it is this isoform that is detected in the in situ hybridization experiments. In wild-type embryos at E10.5, Pitx2c was expressed throughout the left atrium and the midline of the atrial chambers, and to the left of the midline in tissues dorsal to the heart (Fig. 4A). Expression was observed on the left side of the dorsal mesocardium (Fig. 4C, arrow), within the wall of the left atrial appendage (Fig. 4E, black arrow), and on the left side of the vestibular spine (Fig. 4E, red arrow), as well as the myocardium underlying the developing primary atrial septum (data not shown). There was no expression on the right side of these structures. In Shh null hearts, however, both sides of the symmetrical atrial chamber expressed Pitx2c, with positive staining present in both of the atrial appendages (Fig. 4B,D,F, arrows). At the arterial pole, the Pitx2c domain extended along the entire left wall of the outflow tract in wild-type embryos, from the aortic sac to the developing right ventricle (Fig. 4G, arrows). In Shh−/− embryos, in contrast, Pitx2c transcripts were present on both the right and left sides of the outflow tract from the aortic sac to the right ventricle (Fig. 4H). The right and left sides of the arterial and venous poles of the Shh null heart, therefore, have molecularly conferred left-sided identity. As a result, there is no morphologically right identity within the venous and arterial poles of the heart.

Fig. 4.

Pitx2c expression in the atrial chambers and outflow tract in Shh embryos. (A,B) Wholemount staining of isolated hearts shows that whereas only the left atrium expresses Pitx2c (purple) in the wild-type embryo, both atrial chambers express Pitx2c in the Shh−/− embryo. The distal outflow tract has been removed from the wild-type heart, and the Shh−/− heart is viewed from the back to show the atrial cavity more clearly. (C–H) Slide in situ hybridization shows that in wild-type embryos, Pitx2cexpression (purple) is seen on the left side of the dorsal mesocardium (arrow in C), on the left side of the vestibular spine corresponding to the primary atrial septum, in the wall of the left atrial appendage (red and black arrows, respectively, in E), and in the left walls of the outflow tract (arrows in G). In Shh−/− embryos, Pitx2c expression is found in both atrial chambers and on both sides of the outflow tract (arrows in D,F,H). a, indeterminate atrial chamber; la, left atrium; lv, left ventricle; oft, outflow tract; ra, right atrium; rv, right ventricle.

Isl1-expressing cells are required for atrioventricular septation

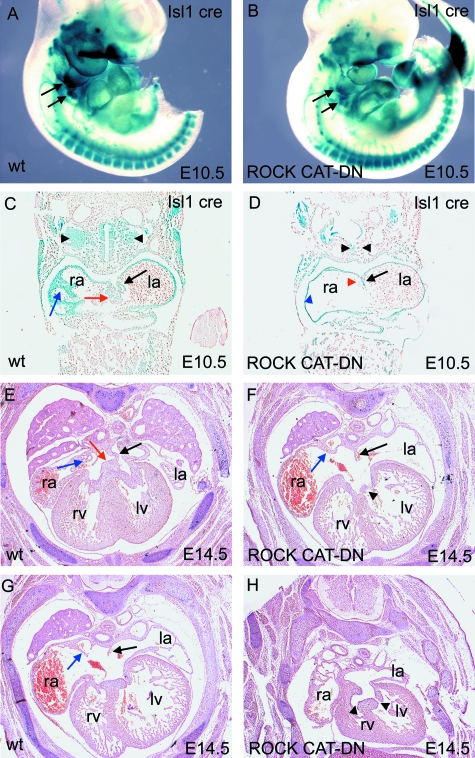

The studies described so far suggest Shh is required for correct left–right patterning of the atrial chambers, and for normal addition of second heart field cells to the venous pole of the heart, but do not distinguish between the relative importance of each for atrial and atrioventricular septation. To elucidate the extent to which disruption of the contribution of cells of the second heart field to the venous pole might be a cause of the defects of the atrial chambers observed in the Shh null embryos, and to distinguish this from the effects of the disturbance of laterality, we set out to disrupt the movement of the cells from the second field into the venous pole of the heart. To do this, we utilized a mouse model with which we have considerable experience in our laboratory (Phillips et al. 2008), namely ROCK CAT-DN (Kobayashi et al. 2004). Rho kinases (ROCKs) are key effectors of RhoA signalling, and are important regulators of the cytoskeleton, playing important roles in movement of cells and development of their polarity (Raftopoulou & Hall, 2004). We predicted, therefore, that blocking ROCK function in cells that express Isl1 would prevent normal movement of cells derived from the second heart field, and allow us to determine which of the effects within the inflow region, seen in the Shh null embryos, are likely due to lack of second heart field cells. We inter-crossed ROCK CAT-DN mice (Kobayashi et al. 2004), which express a dominant-negative ROCK construct in the presence of Cre protein, with Isl1-cre mice and analysed the resulting embryos for structural cardiac malformations.

At E10.5, the overall patterns of β-gal staining were similar in Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN;ROSA26R embryos and their control littermates, suggesting that the inhibition of ROCK function does not have a major effect on the specification ofIsl1-expressing neural progenitors (Fig. 5A,B). In Shh null embryos, nonetheless, we noted a reduction in β-gal staining in the pharyngeal region, including that dorsal to the developing heart, corresponding to the region of the second heart field (Fig. 5A,B, arrows). Sectioning of these embryos showed that there was little or no evidence of formation of either the vestibular spine or the venous valves in Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN;ROSA26R embryos (Fig. 5C,D, red and blue arrows and arrowheads). In contrast, the atrial chambers were well formed, although somewhat dilated, and it was possible to identify the primary atrial septum in all three embryos examined (Fig. 5D, black arrow). Examination of Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN fetuses at E14.5, at the completion of septation, showed that all control embryos had structurally normal hearts, with normal venous and arterial connections. The vestibular spine, however, was absent in three of five Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN hearts, these embryos having a common atrioventricular junction closely resembling those seen in Shh null hearts (Fig. 5F–H). In these hearts, the primary atrial septum had failed to fuse with the superior atrioventricular cushion, although in each case it was possible to identify a rudimentary septum (black arrow in Fig. 5F,G, compare to Fig. 5E). In all five Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN hearts examined, we found totally anomalous pulmonary venous connection, with the pulmonary veins draining into the morphologically right atrium in three hearts (data not shown). In each case, the venous valves were present but hypoplastic, and there was no evidence of the septum spurium (blue arrows in Fig. 5F,G, compare to Fig. 5E). There was no morphological evidence of isomerism of the atrial appendages. In addition to these malformations at the venous pole of the heart, all fetuses had ventricular septal defects and abnormalities in septation of the outflow tract, as might be expected as a consequence of the reduced contribution from the second lineage to the arterial pole of the heart (data not shown; Rhee HJ, Phillips HM, Chaudhry B & Henderson DJ; personal communication). These data suggest that the common atrioventricular junctions observed in the Shh null fetuses are likely to result from the reduced contribution from the second heart field to the vestibular spine. The absence of the primary atrial septum, and the presence of isomeric left atrial appendages in Shh−/− embryos, in contrast, cannot be attributed to this deficiency. These features are likely to have resulted from abnormal left–right specification in the absence of Shh signalling.

Fig. 5.

Isl1-expressing cells are required for atrioventricular septation. (A–D) Wholemount β-gal staining of Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos at E10.5 shows that although β-gal staining is similar to controls throughout most of the embryo, it is reduced in the second heart field, dorsal to the heart tube (arrows in A,B). Sectioning of these embryos shows that the vestibular spine seen in wild-type hearts (red arrow in C), is absent in the hearts of Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos (red arrowhead in D), although the primary atrial septum is present (black arrows in C,D). There is no evidence of venous valves in the Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos (blue arrowhead in D), in contrast to the matched controls (blue arrow in C). The β-gal-expressing second heart field cells dorsal to the heart are reduced in Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos (black arrowheads in C,D). (E–H) Atrioventricular septal defects are seen in Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos at E14.5 (F–H). The vestibular spine (red arrow in E in wild type) is completely absent in Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos; however, a primary atrial septum can be seen, although in some cases this does not fuse with the atrioventricular cushions (black arrows in E–G). Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos also have hypoplastic venous valves, compared to matched controls (blue arrows in E–G). la, left atrium; lv, left ventricle; ra, right-sided atrium; rv, right ventricle.

Discussion

Complete reversal of body plan has no clinical implications. In contrast, visceral heterotaxy, characterized by isomeric rather than lateralized organs, is associated with some of the most complex combinations of cardiac malformations, and with poor clinical outcomes (Jacobs et al. 2007). We have now shown that loss of Shh signalling produces mouse embryos with cardiovascular morphology in keeping with the human condition best described in terms of isomerism of the left atrial appendages, although also known as polysplenia. We have also shown that a common atrioventricular junction connecting exclusively to the left ventricle, along with persistence of the dorsal mesocardial connection, is a feature of the ventrally looped Shh null heart. At the molecular level, we have demonstrated that loss of Shh signalling leads to a phenotype of left isomerism, with bilateral expression of the definitive left-sided marker Pitx2c.

The studies described here have clearly demonstrated a persistence of the dorsal mesocardium and incomplete cardiac looping in the Shh null mutants. In avian development, proliferation of the left portion of the dorsal mesocardium, in association with asymmetric expression of flectin, is associated with normal rightward looping (Tsuda et al. 1996; Linask et al. 2005). Although there have been no reports for a direct role for non muscle myosin IIB (recently identified as flectin; Lu et al. 2008) in cardiac looping in mice, differential proliferation in explants from left and right parts of the second heart field have been shown (Galli et al. 2008). Proliferation and asymmetry could not adequately be assessed in the Shh−/− embryos in this study because of the paucity of cells in this area. The persisting dorsal mesocardium, nonetheless, is seen to tether the outflow tract and left atrium to the remainder of the heart, impeding normal looping. This defect is likely exacerbated by the deficiencies in addition of cells of second heart field origin to the poles of the heart (see below).

As well as revealing abnormalities in left–right specification, our data suggest that Shh null embryos also have reduced numbers of cells originating in the second heart field. This could be due either to a direct requirement for Shh signalling in specification or determination within the second heart field, or an indirect effect as a consequence of the embryonic midline not being correctly specified. The role of Shhsignalling in the specification of the second heart field has been elegantly established by Goddeeris et al. (2007, 2008) using the Mef2C-AHFcre;smoflox/– mouse line. Our own analyses, carried out within the Shh null mouse, endorse their conclusions. Goddeeris and colleagues (2007, 2008), however, did not comment on the role of Shh in establishing morphological leftness in the developing embryo, nor did they discuss the presence of left isomerism as a phenotypic feature of the Shh null embryos, persistence of the dorsal mesocardium, or the finding of univentricular atrioventricular connection to a dominant left ventricle. In our study we have begun to dissect the contribution to this extended cardiac phenotype, which requires left–right identity, as opposed to that which requires contribution from the second heart field. Rho kinase plays essential roles in the cytoskeletal reorganizations that are essential for movement of cells and development of cellular polarity. Blocking its function in Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos prevented the formation of the vestibular spine, also known as the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion, and resulted in atrioventricular septal defects that resembled those seen in Shh null embryos. Thus, the presence of atrioventricular septal defects with common atrioventricular junction in Shh null embryos can be explained as a consequence of lack of contribution from cells normally derived from the second heart field. This again endorses the findings of Goddeeris et al. (2008), who also observed a primary atrial septum in their Mef2c-AHF-cre;Smoflox/– embryos. Analysis of the Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos also revealed that, although connections with the systemic venous tributaries were established, the venous valves were markedly hypoplastic, suggesting that the second heart field also contributes to these structures. This is supported by our lineage tracing of Isl1. It is interesting to note the appearance of a common atrioventricular junction committed exclusively to the left ventricle in the Shh mutants. The area in which the valve should expand and communicate with the right ventricle is clearly seen, but is filled with myocardium. It is unclear whether the valve is specified in the correct area but is obliterated by myocardium, or whether the valve is entirely absent due to lack of second heart field cells. If the second hypothesis is correct, then the lesion would appropriately be described as tricuspid atresia, but in the setting of an ‘ostium primum’ interatrial communication.

The formation of the primary atrial septum in Shh null embryos, where only a remnant of interatrial ridge is seen, suggests that formation of the primary septum is dependent on midline interaction between morphologically right- and left-sided tissues. Abnormalities in the developing midline of the embryo have been emphasized previously as a feature of Shh null mutants, and are suggestive of a role in specification of midline cell types rather than a selective loss of midline tissue (Chiang et al. 1996). Mutant embryos frequently develop with a single midline eye, and a single, fused telencephalic vesicle. Moreover, they fail to establish the fates of cells and patterns of gene expression characteristic of the ventral midline of the neural tube. At a molecular level, the primary atrial septum is a structure that normally expresses Pitx2c, the marker of morphological left-sidedness, and so might be expected to develop relatively normally in the Shh null mutants. Our data show, however, that both the primary atrial septum and the vestibular spine, the latter also known as the dorsal mesenchymal projection, are deficient inShh null embryos and fetuses, resulting in complete failure of formation of the atrial septum. This is in keeping with the occurrence of inter-atrial communications in humans with isomerism of either the right or left atrial appendages (Jacobs et al. 2007), and with the finding of atrioventricular septal defects in lefty-1 null embryos, which also have left isomerism (Meno et al. 1998). Whilst formation of the vestibular spine has been shown to be dependent on the presence of cells from the second heart field (Snarr et al. 2007; Goddeeris et al. 2008), analysis of our Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos suggests that the second heart field is unlikely to make a major contribution to the formation of the primary atrial septum, as this structure was well formed in all the Isl1-cre;ROCK CAT-DN embryos examined. Thus, the atrial septal defects seen in Shh−/− fetuses are likely to be a primary consequence of the left isomerism, whereas the atrioventricular septal defects may be a primary consequence of left isomerism or may be secondary to disruption of the second heart field contributions to the venous pole in these fetuses, or a combination of the two.

The formation and separation of the arterial trunks requires interaction between the arteries arising from the aortic sac, the outflow cushions or ridges, and the second heart field. The single arterial trunk seen in the Shh null mutants terminates in the systemic arteries supplying the upper body. Its development from an outflow vessel that is Pitx2c-positive throughout provides molecular confirmation of its morphologically leftness, supporting the suggestion that the pulmonary trunk, a morphologically right structure, is absent in Shh null embryos (Washington Smoak et al. 2005). Pulmonary atresia has also been created by selective ablation of the right side of the second heart field in the developing chicken embryo (Ward et al. 2005). It has recently been suggested that the expression of Pitx2 only on the left side of the developing outflow vessel may be important for establishing normal positioning of the cushions or ridges that septate the developing outflow tract, and for asymmetrical remodelling of the arteries within the pharyngeal arches (Yashiro et al. 2007).

For those diagnosing congenital cardiac malformations, establishing the arrangement of the atrial chambers is now recognized as the crucial initial step in analysis (Jacobs et al. 2007). Establishing the morphology of the atrial chambers, based on the structure of the appendages, is equally important for those studying cardiac development. In reality, as we have shown, the roles of Sonic hedgehog in determining laterality, in defining midline structures, and in influencing the specification of the second heart field are closely related. If left isomerism, occurring as a result of disrupted Shh signalling or some other pathway, results in the misspecification of the cells derived from the second heart field cells in the midline of the embryo, then this might result in abnormal contributions from this population to the inflow of the heart, ultimately producing atrioventricular septal defects with common atrioventricular junction as is commonly seem in the clinical setting of patients with isomeric atrial appendages. The relative importance of the contributions of the second heart field, as distinct from disturbances of laterality, will be the subject of our continued research.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in its entirety by the British Heart Foundation (RG/02/004 and RG/07/086).

References

- Bamforth SD, Braganca J, Farthing CR, et al. Cited2 controls left-right patterning and heart development through a Nodal-Pitx2c pathway. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1189–1196. doi: 10.1038/ng1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campione M, Steinbeisser H, Schweickert A, et al. The homeobox gene Pitx2: mediator of asymmetric left-right signaling in vertebrate heart and gut looping. Development. 1999;126:1225–1234. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, et al. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383:407–413. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton R, Yamada T, Turnley A, Bartlett PF, Murphy M. Sonic hedgehog promotes neuronal differentiation of murine spinal cord precursors and collaborates with neurotrophin 3 to induce Islet-1. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2601–2608. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02601.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage PJ, Suh H, Camper SA. Dosage requirement of Pitx2 for development of multiple organs. Development. 1999;126:4643–4651. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli D, Domínguez JN, Zaffran S, Munk A, Brown NA, Buckingham ME. Atrial myocardium derives from the posterior region of the second heart field, which acquires left-right identity as Pitx2c is expressed. Development. 2008;135:1157–1167. doi: 10.1242/dev.014563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddeeris MM, Schwartz R, Klingensmith J, Meyers EN. Independent requirements for Hedgehog signaling by both the anterior heart field and neural crest cells for outflow tract development. Development. 2007;134:1593–1604. doi: 10.1242/dev.02824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddeeris MM, Rho S, Petiet A, et al. Intracardiac septation requires hedgehog-dependent cellular contributions from outside the heart. Development. 2008;135:1887–1895. doi: 10.1242/dev.016147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izraeli S, Lowe LA, Bertness VL, et al. The SIL gene is required for mouse embryonic axial development and left-right specification. Nature. 1999;399:691–694. doi: 10.1038/21429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JP, Anderson RH, Weinberg PM, et al. The nomenclature, definition and classification of cardiac structures in the setting of heterotaxy. Cardiol Young. 2007;17(Suppl. 2):1–28. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107001138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Takahashi M, Matsushita N, et al. Survival of developing motor neurons mediated by Rho GTPase signaling pathway through Rho-kinase. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3480–3488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0295-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linask KK, Han M, Cai DH, Brauer PR, Maisastry SM. Cardiac morphogenesis: matrix metalloproteinase coordination of cellular mechanisms underlying heart tube formation and directionality of looping. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:739–753. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S, Sarma S, Martinez-de-la-Torre M, et al. Anatomical and gene expression mapping of the ventral pallium in a three-dimensional model of developing human brain. Neuroscience. 2005;136:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughna S, Henderson D. Methodologies for staining and visualisation of beta-galactosidase in mouse embryos and tissues. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;411:1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-549-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Seeholzer SH, Han M, et al. Cellular nonmuscle myosins NMHC-IIA and NMHC-IIB and vertebrate heart looping. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3577–3590. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti E, Takada R, Bumcrot DA, Sasaki H, McMahon AP. Distribution of Sonic hedgehog peptides in the developing chick and mouse embryo. Development. 1995;121:2537–2547. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meno C, Shimono A, Saijoh Y, et al. lefty-1 is required for left-right determination as a regulator of lefty-2 and nodal. Cell. 1998;94:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers EN, Martin GR. Differences in left-right axis pathways in mouse and chick: functions of FGF8 and SHH. Science. 1999;285:403–406. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman AF, Christoffels VM, Anderson RH, van den Hoff MJ. The heart-forming fields: one or multiple? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362:1257–1265. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips HM, Murdoch JN, Chaudhry B, Copp AJ, Henderson DJ. Vangl2 acts via RhoA signaling to regulate polarized cell movements during development of the proximal outflow tract. Circ Res. 2005;96:292–299. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000154912.08695.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips HM, Hildreth V, Peat JD, et al. Non-cell-autonomous roles for the planar cell polarity gene Vangl2 in development of the coronary circulation. Circ Res. 2008;102:615–623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol. 2004;265:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Ho SY, Anderson RH, et al. The diverse cardiac morphology seen in hearts with isomerism of the atrial appendages with reference to the disposition of the specialised conduction system. Cardiol Young. 2006;16:437–454. doi: 10.1017/S1047951106000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snarr BS, O’Neal JL, Chintalapudi MR, et al. Isl1 expression at the venous pole identifies a novel role for the second heart field in cardiac development. Circ Res. 2007;101:971–974. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda T, Philp N, Zile MH, Linask KK. Left-right asymmetric localization of flectin in the extracellular matrix during heart looping. Dev Biol. 1996;173:39–50. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukui T, Capdevila J, Tamura K, et al. Multiple left-right asymmetry defects in Shh(–/–) mutant mice unveil a convergence of the shh and retinoic acid pathways in the control of Lefty-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11376–11381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura H, Ho SY, Devine WA, Kilpatrick LL, Anderson RH. Atrial appendages and venoatrial connections in hearts from patients with visceral heterotaxy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:561–569. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00538-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mierop LH, Gessner IH. Pathogenetic mechanisms in congenital cardiovascular malformations. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1972;15:67–85. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(72)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Stadt H, Hutson M, Kirby ML. Ablation of the secondary heart field leads to tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary atresia. Dev Biol. 2005;284:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington Smoak I, Byrd NA, Abu-Issa R, et al. Sonic hedgehog is required for cardiac outflow tract and neural crest cell development. Dev Biol. 2005;283:357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Brown NA, Anderson RH. Formation of the atrioventricular septal structures in the normal mouse. Circ Res. 1998a;82:645–656. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Brown NA, Wessels A, Anderson RH. Development of the murine pulmonary vein and its relationship to the embryonic venous sinus. Anat Rec. 1998b;250:325–334. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199803)250:3<325::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Cai CL, Lin L, et al. Isl1Cre reveals a common Bmp pathway in heart and limb development. Development. 2006;133:1575–1585. doi: 10.1242/dev.02322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro K, Shiratori H, Hamada H. Haemodynamics determined by a genetic programme govern asymmetric development of the aortic arch. Nature. 2007;450:285–288. doi: 10.1038/nature06254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]