Abstract

We have investigated the effects of phosphorylation at Ser-617 and Ser-635 within an autoinhibitory domain (residues 595–639) in bovine endothelial nitric oxide synthase on enzyme activity and the Ca2+ dependencies for calmodulin binding and enzyme activation. A phosphomimetic S617D substitution doubles the maximum calmodulin-dependent enzyme activity and decreases the EC50(Ca2+) values for calmodulin binding and enzyme activation from the wild-type values of 180 ± 2 and 397 ± 23 nM to values of 109 ± 2 and 258 ± 11 nM, respectively. Deletion of the autoinhibitory domain also doubles the maximum calmodulin-dependent enzyme activity and decreases the EC50(Ca2+) values for calmodulin binding and calmodulin-dependent enzyme activation to 65 ± 4 and 118 ± 4 nM, respectively. An S635D substitution has little or no effect on enzyme activity or EC50(Ca2+) values, either alone or when combined with the S617D substitution. These results suggest that phosphorylation at Ser-617 partially reverses suppression by the autoinhibitory domain. Associated effects on the EC50(Ca2+) values and maximum calmodulin-dependent enzyme activity are predicted to contribute equally to phosphorylation-dependent enhancement of NO production during a typical agonist-evoked Ca2+ transient, while the reduction in EC50(Ca2+) values is predicted to be the major contributor to enhancement at resting free Ca2+ concentrations.

The nitric oxide synthases catalyze formation of NO and L-citrulline from L-arginine and oxygen, with NADPH as the electron donor (1). The importance of NO generated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)1 in the regulation of smooth muscle contractility is particularly well established and initially led to the discovery of its role in cell signaling (2). All of the synthase isozymes are functional homodimers of 130–160 kDa monomers that each contain a reductase and oxygenase domain (1). A significant difference between P450 reductase and the homologous reductase domains in eNOS and nNOS is the presence of autoinhibitory inserts in the latter (3, 4). A CaM-binding domain is located in the linker that connects the reductase and oxygenase domains, and the endothelial and neuronal synthases require Ca2+ and exogenous calmodulin (CaM) for activity (5, 6).

Bovine eNOS can be phosphorylated in endothelial cells at Ser-116, Thr-497, Ser-617, Ser-635, and Ser-1179 (7–9). There are corresponding phosphorylation sites in human eNOS (7–9). Phosphorylation of the enzyme within the CaM-binding domain at Thr-497 blocks CaM binding and associated enzyme activation (8, 10–12). Phosphorylation at Ser-116 occurs in cells under basal conditions (7, 8, 11, 13), and dephosphorylation of this site has been correlated with an increased level of NO production (11, 13). However, a phosphomimetic substitution at this amino acid position has been reported to have no effect on the activity of the expressed mutant protein (11). Phosphorylation at Ser-617 and/or Ser-635 has been reported to correlate with increased levels of basal and agonist-stimulated NO production in cells (7, 8, 14, 15). Expressed mutant synthase containing a phosphomimetic S635D substitution exhibits elevated activity in cells under resting and stimulated conditions (11, 16–18), and the maximum activity of the isolated mutant enzyme has been reported to be elevated ~2-fold (19). However, there have also been reports that phosphorylation at Ser-635 has no significant effect on synthase activity (8, 20, 21). Improved NO production has been observed in cells expressing mutant eNOS containing an S617D substitution (11, 19), but the isolated mutant protein has been reported to have the same maximum activity as the wild-type enzyme (19). Phosphorylation at Ser-1179 has been demonstrated to occur in endothelial cells in response to a variety of stimuli and is correlated with enhanced NO production (7, 8). This effect is mimicked in cells expressing mutant eNOS containing an S1179D substitution and blocked when an S1179A mutant enzyme is expressed instead (19). Isolated eNOS containing an S1179D substitution exhibits elevated enzyme activity (22). It has been reported that the EC50(Ca2+) value for CaM-dependent enzyme activation is not affected by this phosphomimetic mutation, although reversal of CaM-dependent enzyme activation after addition of a Ca2+ chelator was found to be a slower process with the mutant protein than with the wild-type enzyme (22). Although it is evident that phosphorylation at one or more sites in eNOS has functional consequences, interpretation of correlations between phosphorylation and changes in NO production in the cell is complicated by the presence of additional regulatory factors such as HSP90, NOSIP, and caveolin, and by the fact that physiological changes in the phosphorylation status of eNOS always appear to involve more than one site in the enzyme (7–9).

To improve our understanding of how phosphorylation modulates NO production in cells, we have begun to investigate the effects of single and combined phosphorylations at known sites in eNOS on the properties of the enzyme that are most relevant to NO production in nonexcitable cells, namely, maximum CaM-dependent catalytic activity and the relationships among fractional CaM binding, fractional activity, and the free Ca2+ concentration. In this paper, we describe the effects on these properties of phosphomimetic Asp substitutions in the bovine enzyme at Ser-617 and Ser-635. The S617D substitution doubles the maximum CaM-dependent synthase activity and produces an ~35% reduction in the EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation. The S635D substitution has little or no effect by itself and does not influence the effects of the S617D substitution when combined with it. Deleting an autoinhibitory domain (residues 595–639) that contains Ser-617 and Ser-635 doubles the maximum CaM-dependent synthase activity and produces an ~70% reduction in the EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation. These results suggest that phosphorylation at Ser-617 partially reverses suppression by the autoinhibitory domain. Associated effects on EC50(Ca2+) values and maximum calmodulin-dependent enzyme activity are predicted to contribute equally to phosphorylation-dependent enhancement of NO production during a typical agonist-evoked Ca2+ transient, while the reduction in EC50(Ca2+) values is predicted to be the major contributor to enhancement at resting free Ca2+ concentrations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vectors for Expression of Six-His-Tagged Wild-Type and Mutant eNOS

A pCWori vector (23, 24) for expression of wild-type bovine eNOS that was constructed using a cDNA clone isolated by Sessa et al. (25) was kindly provided by L. J. Roman and B. S. S. Masters. A six-His tag was added to the N-terminus of eNOS using the following strategy. An NcoI restriction site containing the start codon for the eNOS cDNA was introduced by performing primer extension mutagenesis. Cleavage at this site and another NcoI site present in the initial pCWori construct was performed, and the resulting fragment was ligated in its sense orientation into a pET30a expression vector (Novagen, Inc.) opened at the NcoI site in the multiple cloning region, thereby fusing the eNOS cDNA in frame with the upstream portion of the vector encoding a six-His/S-tag. An NdeI–KpnI fragment encoding most of the fusion protein was excised from this intermediate pET30a construct and ligated into the initial pCWori expression vector opened with these restriction enzymes, to produce the final pCWori construct for bacterial expression of six-His-tagged wild-type eNOS. Mutagenesis of the cDNA sequence in this vector to introduce S617D and S635D phosphomimetic substitutions was performed using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Stratagene, Inc.). The following oligonucleotides were used as primers: S617D sense, GATCCGCTTCAACGACGTCTCCTGCTC; S617D antisense, GAGCAGGAGACGTCGTTGAAGCGGATC; S635D sense, GAAGAGAAAGGAGGACAGCAACACAGAC; and S635D antisense, GTCTGTGTTGCTGTCCTCCTTTCTCTTC. Deletion of cDNA encoding an autoinhibitory domain (residues 595–639) was accomplished by performing overlap extension mutagenesis with the following primer sets: 5′ sense primer, GCTGGGGAGCATCACCTACG; 5′ antisense, CAGGGCCCCCGCACTCTCCATCAGGGCAGC; 3′ sense, AGTGCGGGGGCCCTGG; and 3′ antisense, GTGCTCAGCCGGTACCTC. The protein-encoding regions of all the pCWori constructs used were verified in their entireties by performing dye terminator DNA sequencing. The approach of mimicking phosphorylation with Asp or Glu substitutions has been successfully used to investigate phosphorylation-dependent regulation in a number of different systems (26–35). Furthermore, several laboratories have employed phosphomimetic mutations to investigate the effects of eNOS phosphorylation in cells and in vitro, and these appear to have recapitulated the effects of bona fide phosphorylation (9).

Expression and Purification of Proteins

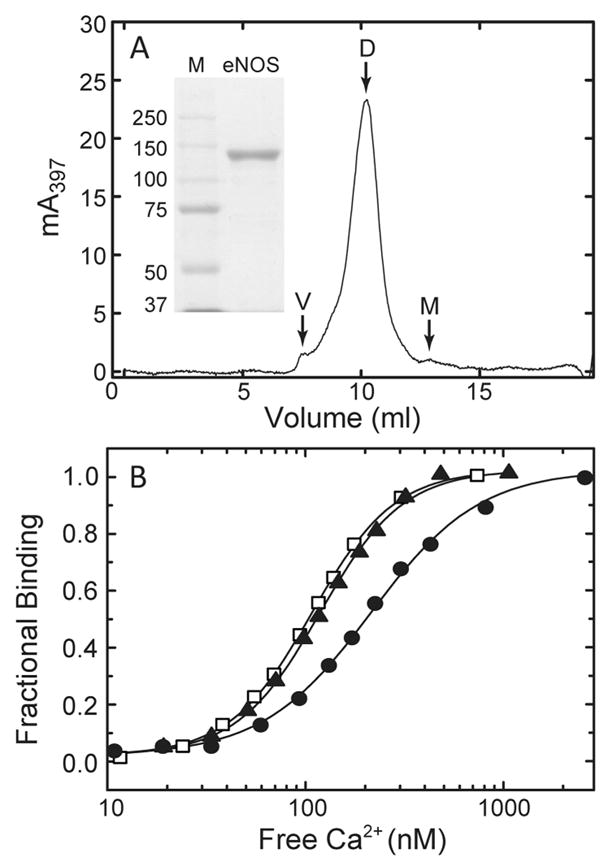

Expression and purification of wild-type and mutant eNOS was performed, with modifications, according to the method of Hühmer et al. (36). Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells freshly transformed with the desired pCWori expression vector were seeded into 50 mL of Terrific Broth [composition per liter, 12 g of tryptone, 24 g of yeast extract, 12.5 g of K2HPO4, 2.3 g of KH2PO4, and 4 mL of glycerol (pH 7.4)] containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and shaken overnight (~16 h) at 250 rpm at 37 °C. This culture was then used to inoculate 1 L of Terrific Broth, which was then incubated at room temperature in 2.5 L Fernbach flasks shaken at 250 rpm until the OD660 of the culture reached a value of 0.8–1.0. Protein expression was then induced by adding 1 mM isopropyl β-D-galactoside, and culture flasks were immediately moved to a 22 °C incubator and incubated with shaking at 250 rpm for a further 48 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000g at 4 °C. Cell pellets were frozen at −85 °C and stored for 1–10 days prior to use. Frozen pellets were thawed and suspended by agitating them at 200 rpm in buffer A [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, FAD and FMN (2 μM each), 1 μg/mL antipain, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin A, 0.1 mM PMSF, and 200 mM NaCl]. Fully suspended cells were passed twice through a microfluidizer, and the resulting lysate was subjected to centrifugation at 100000g for 35 min at 4 °C. After addition of 10 mM imidazole, the supernatant fraction was loaded onto 25 mL of Ni-NTA Sepharose (Qiagen, Inc.) resin at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. The resin was washed with 10 volumes of buffer B [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, FAD and FMN (2 μM each), 1 μg/mL antipain, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin A, 0.1 mM PMSF, and 500 mM NaCl], and bound proteins were eluted in buffer B with 100 mM imidazole. The eluate was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C versus 1 L of buffer C [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, FAD and FMN (2 μM each), 1 μg/mL antipain, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin A, 0.1 mM PMSF, and 100 mM NaCl] and loaded onto 10 mL of 2′–5′ ADP Sepharose resin equilibrated with buffer D [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, FAD and FMN (2 μM each), 0.1 mM PMSF, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 100 mM NaCl]. The resin was washed with 10 volumes of buffer E [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 300 mM NaCl], and bound proteins were eluted in buffer E with 20 mM 2′,3′-AMP (mixed isomers) and 200 mM NaCl (final concentration of 500 mM). Eluted fractions were pooled, and 10 μM BH4, 0.1 mM DTT, and 5 mM L-arginine were added. This solution was concentrated and buffer-exchanged by ultrafiltration at 4 °C in a Centriprep-50 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore Corp., New Bedford, MA) to produce a solution of purified eNOS in buffer containing 10% (v/v) glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM L-arginine, 0.2 μM BH4, 20 μM DTT, 1 mM 2′,3′-AMP (mixed isomers), and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4). Final concentrations of purified enzyme are typically ~40 μM, based on an ε397 of 100 mM−1 (37). The yield is typically ~5 mg of eNOS per liter of bacterial culture. Purified enzyme is usually used within 3 days of preparation but in our hands can be stored at −85 °C for up to 1 month with no detectable loss of catalytic activity. Representative SDS gel electrophoretic and size-exclusion chromatographic analyses are presented in Figure 1A. Wild-type CaM was purified as described in detail elsewhere (38).

Figure 1.

(A) Analysis of purified eNOS by SDS gel electrophoresis (inset) and size-exclusion chromatography. A total of 100 μL of a 24 μM solution of purified eNOS was loaded onto a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (~20 mL inclusion volume). The column was developed at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6) and 100 mM KCl. The void volume (V), eNOS dimer (D), and eNOS monomer (M) fractions are labeled. The shoulder apparent between the void volume and dimer peaks varies with the concentration of eNOS loaded onto the column and the flow rate (data not shown) and probably represents a weakly associated tetrameric form of the enzyme. (Inset) SDS gel electrophoresis of 10 μg of purified eNOS was performed in an 8% polyacrylamide slab gel. Protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue. The lane marked M contains mobility standards with the indicated molecular weights. (B) Effect of different total eNOS and CaM concentrations on the relationship between fractional CaM binding to eNOS and [Ca2+]free. Purified eNOS and CaM concentrations were 0.2 and 0.15 μM (●), 0.7 and 0.5 μM (▲), and 3.5 and 2.5 μM (□), respectively, with a fixed eNOS:CaM molar ratio of 1.4:1.

Determination of Enzyme Activities in the Presence and Absence of CaM

NO synthase rates were determined by measuring conversion of [3H]-L-arginine to [3H]-L-citrulline, which is a byproduct of NO synthesis. Reaction mixtures (50 μL) contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 μM BH4, 100 μM DTT, 50 μM NADPH, 51 μM [3H]-L-arginine, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 250 μM CaCl2, and 125 nM eNOS, with or without 1.3 μM CaM. Mixtures for reactions initiated by adding L-arginine and NADPH were incubated for 3 min at 25 °C. Reactions were terminated, and the amount of [3H]-L-citrulline produced was quantitated as described in detail elsewhere (39). The specific activity of wild-type eNOS under these conditions is 82.4 ± 3.3 nmol min−1 mg−1. NADPH oxidation rates were determined by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm due to conversion of NADPH to NADP+, using an extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1 cm−1 (40); 100 μL reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 10 μM BH4, 100 μM DTT, 50 μM NADPH, 250 μM CaCl2, and 125 nM eNOS, with or without 1.3 μM CaM and/or 50 μM L-arginine. Rates were derived from linear fits to reaction time courses measured after addition of substrate(s). Cytochrome c reductase activities were determined by measuring the increase in the absorbance at 550 nm due to reduction of cytochrome c, using an extinction coefficient of 21 mM−1 cm−1 (41); 100 μL reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 50 μM NADPH, 100 μM cytochrome c, 250 μM CaCl2, and 125 nM enzyme, with or without 1.3 μM CaM. Rates were derived from linear fits to reaction time courses measured after addition of NADPH and cytochrome c. Enzyme-catalyzed reaction rates given in this paper have all been corrected for nonspecific background activity.

Determination of Relationships between CaM Binding and [Ca2+]free

Observed Ca2+ dependencies for CaM binding are the result of dependencies on the concentrations of Ca2+, CaM, and enzyme. For comparative purposes, it is necessary to determine intrinsic Ca2+ dependencies, which are the observed Ca2+ dependencies at a saturating CaM plus enzyme concentration, with enzyme in sufficient molar excess over CaM to preclude formation of significant concentrations of free Ca2+-bound CaM. For these experiments, a 1.4-fold molar excess of eNOS was used, and a saturating CaM plus enzyme concentration was established empirically (Figure 1B). Since eNOS binds CaM with a KD value of ≤150 pM in the presence of Ca2+ (42), negligible concentrations of free Ca2+-bound CaM are produced under these experimental conditions. Binding of CaM to eNOS was assessed on the basis of the reduction in the amount of Ca2+-free CaM bound to a fluorescent protein biosensor (BSCaMA) that we have characterized in detail elsewhere (43). Free Ca2+ concentrations were determined concurrently using indo-1. At the CaM and BSCaMA concentrations used for these experiments, BSCaMA (KD ~ 2.5 μM) is less than 50% saturated with CaM, so there is an approximately linear relationship between the fractional increase in the amount of CaM bound to eNOS and the fractional decrease in the amount bound to the biosensor. Fractional binding to eNOS (FB) can therefore be related to the BSCaMA fluorescence emission ratio (R = 525 nm/480 nm) according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where Rmax and Rmin are the emission ratios for CaM-free and CaM-saturated BSCaMA, respectively, and C = Sb/Sf, where Sf and Sb are the fluorescence emission intensities at 480 nm for CaM-free and CaM-saturated BSCaMA, respectively. Free Ca2+ concentrations were derived from indo-1 emission ratios (R = 405 nm/485 nm) according to the standard relationship:

| (2) |

where Sf and Sb are the fluorescence emission intensities for Ca2+-free and Ca2+-saturated indo-1 at 485 nm, respectively, and Rmin and Rmax are the corresponding emission ratios. Measurements of BSCaMA and indo-1 fluoresence were performed using a PTI (New Brunswick, NJ) QM-1 fluorometer, with respective excitation wavelengths of 430 and 330 nm. Emission and excitation bandwidths of 2.5 nm were used. Reaction mixtures (1.5 mL) contained 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 3 μM indo-1, 5 μM BSCaMA, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 1.25 mM BAPTA, 3.5 μM eNOS, and 2.5 μM CaM were incubated at 22 °C in a stirred 2 mL quartz cuvette. Measurements of BSCaMA and indo-1 fluorescence were made at a series of free Ca2+ concentrations produced by incremental addition of CaCl2. The total change in volume produced by these additions was <2%.

Determination of Relationships between Enzyme Activity and [Ca2+]free

The Ca2+ dependencies for enzyme activation were determined under conditions comparable to those used for analyses of CaM binding. Enzyme activities were derived from linear least-squares fits to time courses for the decrease in NADPH fluorescence emission at 460 nm (340 nm excitation) due to its conversion to NADP+. Free Ca2+ concentrations were derived from measurements of calcium orange fluorescence emission at 570 nm (550 nm excitation). Reaction mixtures (1.5 mL) containing 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 40 μM NADPH, 10 μM tetrahydrobiopterin, 50 μM L-arginine, 0.4 μM calcium orange, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 1.25 mM BAPTA, 0.7 μM eNOS, and 0.5 μM CaM were incubated at 22 °C in a stirred 2 mL quartz cuvette. In a typical experiment, enzyme activity under nominally Ca2+-free conditions was established, an aliquot of a CaCl2 stock solution was added, and the changes in calcium orange fluorescence and the rate of NADPH oxidation were measured. These measurements were then repeated after addition of another aliquot of CaCl2. Since substrate is rapidly consumed under these conditions, only one or two sets of measurements can be made, after which 1.5 mM CaCl2 was added and maximum CaM-dependent activity was measured. Enzyme activities from each set of measurements are expressed as a fraction of the maximum CaM-dependent activity determined for that set. Fractional activities derived from measurements at several different intermediate free Ca2+ concentrations were combined to produce a complete Ca2+ titration curve. NADPH, tetrahydrobiopterin, and L-arginine at the concentrations used for these experiments do not affect the Ca2+ dependencies for CaM binding (data not shown).

Free Ca2+ concentrations were calculated from measurements of Ca2+ orange fluorescence emission according to the relationship:

| (3) |

where F is the emission intensity measured at 570 nm and Fmin and Fmax are the emission intensities measured under nominallyCa2+-freeandCa2+-saturating conditions, respectively.

Analysis of Ca2+ Dependencies for CaM Binding and Enzyme Activation

Relative KD values of 230 and 200 nM were derived for indo-1 and calcium orange by calibrating their responses against those of a fluorescent protein Ca2+ indicator that binds Ca2+ via an EF hand pair (44) (data not shown). Calibration of the indicators in this manner allows us to directly compare the relationships between CaM binding or enzyme activation and the free Ca2+ concentration, in spite of the fact that different Ca2+ indicators were used to determine these relationships.

Plots of fractional CaM binding (FB) or enzyme activation (FA) versus the free Ca2+ concentration were analyzed by nonlinear least-squares fitting to a Hill-type equation:

| (4) |

where n is the Hill coefficient.

The dependencies of FA and FB on the free Ca2+ concentration were also analyzed according to an explicit sequential model:

where E is eNOS and an asterisk denotes the CaM-activated form of the enzyme. Since Ca2+ binding to each EF hand pair in CaM is highly cooperative (38), it is treated as a concerted process. The first step in this mechanism accounts for fractional CaM binding (FB) according to the following equation:

| (5) |

where K1K2 is the product of the Ca2+ binding constants for one of the EF hand pairs in CaM. Fractional CaM-dependent enzyme activation (FA), which in this model requires Ca2+ binding to both EF hand pairs in CaM, is defined according to the relation:

| (6) |

where K3K4 is the product of the Ca2+ binding constants for the second pair of sites. Data for fractional CaM binding and CaM-dependent enzyme activity were simultaneously fitted to eqs 5 and 6 to derive K1K2 and K3K4 values (Table 2). Although a more complex model that includes the individual Ca2+ binding constants could in principle be used, given the high degree of cooperativity between the sites in each EF hand pair, equilibrium Ca2+ binding to a CaM–target complex is in general adequately defined by the products of the constants (38, 45).

Table 2.

| eNOS | K1K2 (nM2) | K3K4 (nM2) |

|---|---|---|

| wild-type and S635D | 28712 ± 2810 | 142582 ± 12330 |

| S617D and S617/635D | 11832 ± 1165 | 54196 ± 4742 |

| ΔAI | 4680 ± 373 | 9702 ± 592 |

Fits of pooled data for wild-type and S635D eNOS (Figure 5A) or S617D and S617/635D eNOS (Figure 5B) and of data for ΔAI eNOS (Figure 5C) to the two equations were performed. K1K2 and K3K4 are the products of the dissociation constants for the two EF hand pairs in CaM. Standard errors were derived from the variance–covariance matrices for the fits.

Mammalian Cell Culture

Bovine aortic endothelial cells were cultured as described previously (46). Estimation of the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration in these cells after addition of 10 nM bradykinin was performed using indo-1 as described previously (46).

RESULTS

NO Synthase and NADPH Oxidation Rates

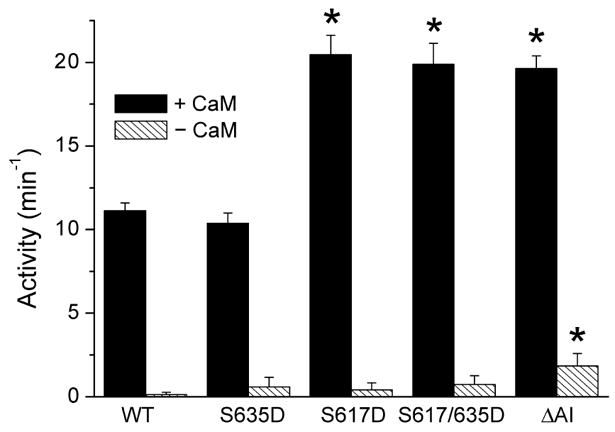

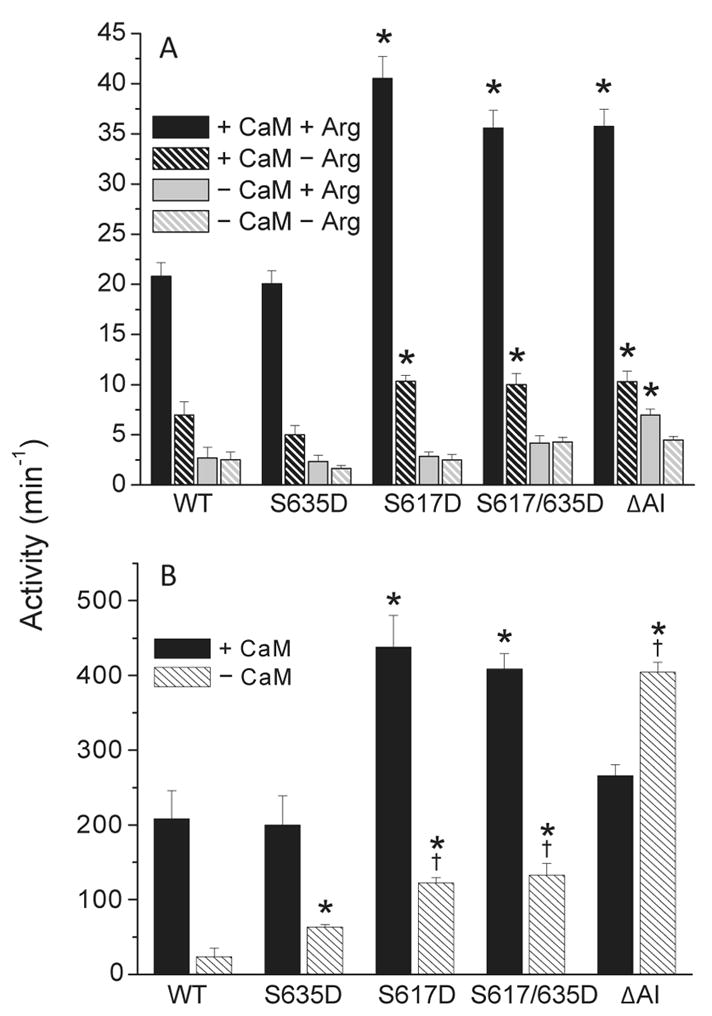

The maximum CaM-dependent synthase activities of S617D and S617/635D eNOS are ~2-fold higher than the wild-type activity (Figure 2). This increase is in both cases due to the S617D substitution, since the S635D substitution by itself has no effect on maximum CaM-dependent synthase activity (Figure 2). The maximum CaM-dependent synthase activity of ΔAI eNOS, which lacks an autoinhibitory domain (bovine residues 595–639), is also ~2-fold higher than the wild-type activity. In the absence of CaM, synthase rates for the wild-type and mutant enzymes are ≤15% of their maximum CaM-dependent rates. The synthase activity of ΔAI eNOS in the absence of CaM is slightly higher than the wild-type activity, but the activities of the proteins containing phosphomimetic substitutions are not significantly different from the wild-type activity (Figure 2). Maximum CaM-dependent NADPH oxidase activities determined for S617D, S617/635D, and ΔAI eNOS in the presence of L-arginine are ~2-fold higher than the wild-type activity (Figure 3A). The CaM-dependent NADPH oxidase activities determined for these proteins in the absence of L-arginine are also ~2-fold higher than the wild-type activity. In the absence of CaM, the oxidase activities of wild-type eNOS and the enzymes containing phosphomimetic substitutions are ≤15% of the maximum rates determined in the presence of CaM and L-arginine (Figure 3A). The NADPH oxidase activity of ΔAI eNOS determined in the absence of CaM is slightly higher than the wild-type activity determined under the same conditions, which is consistent with the slightly elevated CaM-independent synthase activity exhibited by this protein (Figure 2). All of the effects of phosphomimetic substitutions on NADPH oxidase rates are due to the S617D substitution, since the S635D substitution by itself has no significant effect on NADPH oxidase activity (Figure 3A). The results presented in Figures 2 and 3A indicate an NADPH:NO ratio of 2, slightly higher than the value of 1.5 expected on the basis of the catalytic mechanism. Similar discrepancies have been noted by others (47), although the degree to which they represent uncoupled reductase activity and direct oxidation of NADPH by reactive oxygen/nitrogen species remains to be established. Key observations are as follows. (1) The S617D substitution or deletion of the autoinhibitory domain increases maximum CaM-dependent NO synthase and NAD-PH oxidase activities ~2-fold. (2) CaM-independent synthase and oxidase activities are slightly elevated by the deletion. (3) The S635D substitution has no effect by itself, and it does not alter the effects of the S617D substitution when combined with it.

Figure 2.

Nitric oxide synthase activities of wild-type (WT) eNOS and the indicated mutants determined in the presence and absence of a saturating Ca2+-bound CaM concentration. Error bars are standard deviations for the mean of six independent determinations made using a minimum of two different enzyme preparations. Nitric oxide production was monitored by measuring the associated conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline as described in Materials and Methods. The specific activity for wild-type eNOS determined under these conditions is 82.4 ± 3.3 nmol min−1 mg−1. Values denoted with asterisks were determined in unpaired t tests to be significantly higher (p < 0.005) than the control value derived for wild-type eNOS. Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 μM BH4, 100 μM DTT, 50 μM NADPH, 51 μM [3H]-L-arginine, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 250 μM CaCl2, and 125 nM eNOS, with or without 1.3 μM CaM.

Figure 3.

(A) NADPH oxidase activities of wild-type and mutant eNOS measured in the presence and absence of saturating Ca2+-bound CaM and/or L-arginine concentrations. Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 10 μM BH4, 100 μM DTT, 50 μM NADPH, 250 μM CaCl2, and 125 nM eNOS, with or without 1.3 μM CaM and/or 50 μM L-arginine. (B) Cytochrome c reductase activities of wild-type and mutant eNOS measured in the presence and absence of CaM. Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 50 μM NADPH, 100 μM cytochrome c, 250 μM CaCl2, and 125 nM enzyme, with or without 1.3 μM CaM. Error bars in both panels are standard deviations for the mean of six independent determinations made using a minimum of two different enzyme preparations. Values denoted with asterisks were found in unpaired t tests to be significantly higher (p < 0.005) than the control value derived for wild-type eNOS. Values denoted with daggers were similarly found to be significantly higher than the value derived for S635D eNOS.

Cytochrome c Reductase Rates

To further probe the effects of phosphomimetic substitutions on eNOS activity, assays of cytochrome c reductase activity were performed (Figure 3B). Since cytochrome c can accept electrons directly from the reductase domain, this approach in principle allows the electron transfer reactions occurring within this domain to be assessed in a manner independent of overall synthase activity. As seen with synthase and oxidase activities, maximum CaM-dependent reductase activity is increased ~2-fold by the S617D and S617/635D substitutions. Since the S635D substitution by itself has no significant effect, this increase can be attributed to the S617D substitution. The reductase activities of the S617D and S617/635D mutants measured in the absence of CaM are ~5-fold higher than the wild-type CaM-independent activity. Deletion of the autoinhibitory domain increases reductase activity in the absence of CaM to a value ~2-fold higher than the maximum CaM-dependent wild-type activity and 20-fold higher than the wild-type activity in the absence of CaM, but this activity is significantly inhibited by CaM (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the S635D substitution appears to slightly increase reductase activity in the absence of CaM. This is the only significant effect of the S635D substitution that we have observed in the course of these investigations. The S635D mutation does not alter the effect of the S617D mutation when combined with it. Key observations are as follows. (1) The S617D substitution increases the maximum CaM-dependent reductase activity ~2-fold, and (2) CaM-independent reductase activity is increased 5-fold by the S617D substitution and 20-fold by deletion of the autoinhibitory domain.

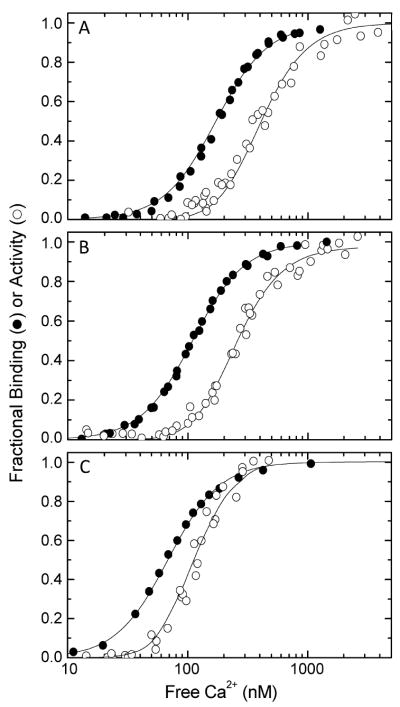

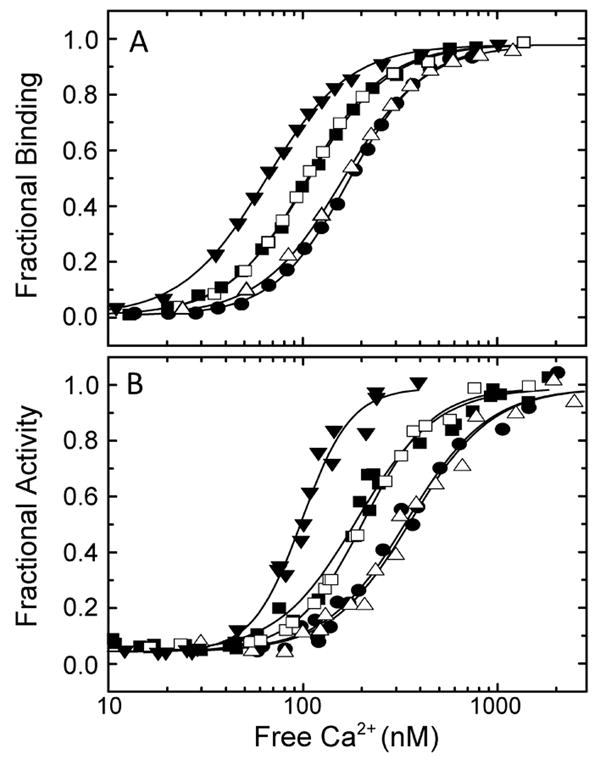

Relationships among CaM Binding, Enzyme Activation, and [Ca2+]free

Under the experimental conditions, we have used the observed Ca2+ dependencies for CaM binding and enzyme activation determined solely by the Ca2+ binding properties of the CaM–eNOS complex, and they are therefore considered to be “intrinsic” Ca2+ dependencies. Intrinsic values are required for direct comparison of the observed Ca2+ dependencies of different CaM–eNOS complexes. Otherwise, the effects of second-order dependencies on the concentrations of CaM and eNOS will complicate the comparison. Fits of data for CaM binding and the free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]free) to eq 4 are presented in Figure 4A; EC50(Ca2+) values and Hill coefficients (a measure of the steepness of the Ca2+ dependence) derived from these fits are listed in Table 1. The EC50(Ca2+) value derived for wild-type eNOS is 180 ± 2 nM; the values derived for S617D and S617/635D eNOS are 109 ± 2 and 106 ± 3 nM, respectively, 35% smaller than the wild-type value. Deletion of the autoinhibitory domain reduces the EC50(Ca2+) value for CaM binding to 65 ± 4 nM, 70% smaller than the wild-type value. The Ca2+ dependencies for activation of synthase activity were determined under conditions similar to those used for binding, except for the presence of 10 μM BH4, 40 μM NADPH, and 50 μM L-arginine. None of these additions was found to significantly affect the Ca2+ dependencies for CaM binding (data not shown). In order to avoid nonlinear rates in activity assays, eNOS and CaM concentrations in these assays were 5-fold lower than in binding assays. This reduction does not significantly affect the EC50(Ca2+) values for binding (Fig. 1B), so for our purposes data obtained under the two sets of conditions can be considered equivalent. To eliminate a low level of fluorescence spillover between NADPH and indo-1, calcium orange was used instead of indo-1 to determine [Ca2+]free values in these experiments. Fits of data for CaM-dependent enzyme activity and [Ca2+]free to eq 4 are presented in Figure 4B; EC50(Ca2+) values and Hill coefficients derived from these fits are listed in Table 1. The EC50(Ca2+) value derived for wild-type eNOS is 397 ± 23 nM; the values derived for the S617D and S617/635D mutants are 258 ± 11 and 261 ± 6 nM, respectively, 35% smaller than the wild-type value. Deletion of the autoinhibitory domain reduces the EC50(Ca2+) for CaM binding to a value of 118 ± 4 nM, 70% smaller than the wild-type value. The EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation derived for S635D eNOS are not significantly different from the wild-type values (Table 1). Key observations are as follows. (1) The S617D substitution reduces the EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation by 35%, approximately half as much as they are reduced by deletion of the autoinhibitory domain. (2) The S635D substitution has no significant effect on EC50(Ca2+) values and does not alter the effect of the S617D substitution when combined with it. (3) EC50(Ca2+) values for enzyme activation are consistently ~2-fold higher than values for CaM binding.

Figure 4.

(A) Relationships between [Ca2+]free and fractional CaM binding to wild-type (●), S617D (■), S635D (△), S617/635D (□), and ΔAI (▼;) eNOS. Reaction mixtures contained 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 3 μM indo-1, 5 μM BSCaMA, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 1.25 mM BAPTA, 3.5 μM eNOS, and 2.5 μM CaM. (B) Relationships between [Ca2+]free and fractional activation of wild-type (●), S617D (■), S635D (△), S617/635D (□), and ΔAI (▼;) eNOS NADPH oxidase activities. Reaction mixtures contained 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 40 μM NADPH, 10 μM tetrahydrobiopterin, 50 μM L-arginine, 0.4 μM calcium orange, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 1.25 mM BAPTA, 0.7 μM eNOS, and 0.5 μM CaM. The curves in panels A and B correspond to nonlinear least-squares fits to eq 4. These data are representative of experiments performed with a minimum of two different preparations of wild-type or mutant eNOS.

Table 1.

| eNOS | EC50(Ca2+)B (nM) | EC50(Ca2+)A (nM) | nB | nA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type | 180 ± 2 | 397 ± 23 | 2.24 ± 0.06 | 1.93 ± 0.21 |

| S635D | 168 ± 2 | 392 ± 25 | 2.1 ± 0.07 | 2.11 ± 0.27 |

| S617D | 109 ± 2b | 258 ± 11b | 2.06 ± 0.05 | 2.39 ± 0.27 |

| S617/635D | 106 ± 3b | 261 ± 6b | 2.14 ± 0.07 | 2.48 ± 0.11 |

| ΔAI | 65 ± 4b | 118 ± 4b | 2.07 ± 0.05 | 3.38 ± 0.42 |

Values for EC50(Ca2+) and n derived from CaM binding and enzyme activation data are identified with B and A subscripts. Standard errors were derived from the variance–covariance matrices for the fits.

Value determined in an f test to be significantly smaller (p < 0.001) than the corresponding control value derived for wild-type eNOS.

The differences between the EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation that we have observed indicate that the two processes are sequential, as depicted in Scheme 1. In this scheme, Ca2+ binding to one of the two EF hand pairs in CaM controls formation of the CaM–eNOS complex, and subsequent binding to the other pair of sites controls enzyme activation. Corresponding data for the Ca2+ dependencies of CaM binding and enzyme activation were therefore fit simultaneously to eqs 5 and 6, which were derived on the basis of Scheme 1. Data for wild-type and S635D eNOS were pooled for this analysis, as were data for S617D and S617/635D eNOS, because in both cases the two sets of data appear to be indistinguishable (see Figure 4). The fitted curves thus obtained are presented in Figure 5, and the derived parameters are listed in Table 2. As seen in Figure 5, the data are fit quite well by the model equations. In particular, fractional enzyme activation exhibits a steeper dependence on [Ca2+]free than fractional CaM binding. This is expected because according to Scheme 1, CaM binding depends on the square of [Ca2+]free (eq 5), while enzyme activation has a more complex dependence on both the square and fourth power of [Ca2+]free (eq 6). On the basis of the properties of neuronal NOS and the generally higher affinity of the C-terminal EF hand pair for Ca2+, the Ca2+ binding sites controlling binding of CaM to eNOS probably correspond with the C-terminal EF hand pair, with enzyme activation dependent upon the additional occupancy of the N-terminal pair of sites (39). An interesting implication of the differences in the EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation is that at resting free Ca2+ concentrations Ser-617 phosphorylation could promote significant prebinding of CaM, i.e., binding that does not produce enzyme activation.

Scheme 1.

Figure 5.

Data for fractional CaM binding (●) and fractional enzyme activation (○) fitted to the model presented in Scheme 1. (A) Pooled data for wild-type and S635D eNOS. (B) Pooled data for S617D and S617/635D eNOS. (C) Data for ΔAI eNOS. Data sets were pooled as indicated for this analysis because there is no significant difference between them (see Table 1). The two curves presented in each panel were generated by simultaneous least-squares fitting of fractional binding and enzyme activation data to eqs 5 and 6 using the Excel solver add-in. One pair of K1K2 and K3K4 values applies to the data presented in each panel (see Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that phosphorylation at Ser-617 partially reverses suppression by the autoinhibitory domain, thereby increasing maximum CaM-dependent activity ~2-fold and decreasing the EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation by 35%. Variable effects of phosphorylations or, more often, phosphomimetic substitutions at Ser-617 and Ser-635 on the maximum enzyme activity have been reported in the literature. Our results are in agreement with reports that phosphorylation or a phosphomimetic substitution at Ser-617 increases the maximum CaM-dependent synthase activity in cells or cell extracts (11,19) but are in disagreement with reports that the same alterations at Ser-635 have a similar effect (11, 16–18). The possible reason for this discrepancy is that in eukaryotic cells phosphorylation or a phosphomimetic substitution at Ser-635 alters phosphorylation at other sites in the enzyme (11). In this regard, bacterial expression has the distinct advantage that the kinases responsible for eNOS phosphorylation are not present. The basis for the observed ~2-fold increase in the maximum CaM-dependent activity produced by the deletion or the S617D substitution is unclear. Although the efficiency of electron transfer to the oxygenase domain is much lower than to cytochrome c, the apparent correlation between increases in CaM-dependent reductase and synthase activities suggests that an S617D substitution or deletion of the autoinhibitory domain shifts the equilibrium between active and repressed forms of the reductase domain in the direction of the active form (Figures 2 and 3). Increases in CaM-independent reductase activity associated with the S617D substitution or deletion of the autoinhibitory domain indicate a shift towards the active form of the reductase domain even in the absence of CaM (Figure 3). Indeed, deletion of the autoinhibitory insert appears to completely derepress reductase activity in the absence of CaM (Figure 3B). Increases in maximum CaM-dependent synthase and reductase activities, as well as CaM-independent reductase activity, appear to be limited by a ceiling equivalent to approximately twice the maximum CaM-dependent activities of the wild-type enzyme. This suggests that a significant fraction of the reductase domain in unphosphorylated eNOS remains in its inactive form even when the enzyme is replete with CaM.

Since the Ca2+-bound form of CaM is required for enzyme activation, Ca2+ binding to CaM in its complex with the synthase must be coupled energetically to the activation process, which includes derepression of reductase activity. It follows from this that removing the autoinhibitory insert, which results in complete derepression of reductase activity, should decrease the intrinsic EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and activation, which is exactly what we have observed (Table 1). It also follows that the S617D mutation, which partially derepresses reductase activity, should, as observed, produce a smaller decrease in these values (Table 1). From an energetic standpoint

| (7) |

where ΔΔGP is the phosphorylation-dependent change in the ΔG for CaM-dependent enzyme activation, assuming no change in the energetics for CaM binding in the absence of Ca2+, and (K1K2K3K4)P and (K1K2K3K4)U are the products of the Ca2+ dissociation constants for CaM bound to phosphorylated and unphosphorylated eNOS, respectively. A ΔΔGP value of −1.1 kcal/mol can be calculated from the values for wild-type and S617D eNOS listed in Table 2. The ΔΔG value associated with deletion of the entire autoinhibitory domain can be shown through a similar calculation to be −1.6 kcal/mol. If we consider the ΔΔGP value to apply directly to the equilibrium between active and inactive forms of the reductase, the following relation applies:

| (8) |

where KA/I is the constant for the equilibrium between active (A) and inactive (I) forms of the reductase in the presence of CaM. Thus, the observed ΔΔGP value corresponds to an ~7-fold increase in the value for KA/I, while the ΔΔG value associated with deletion of the autoinhibitory region corresponds to an ~15-fold increase in KA/I. If we assume that the KA/I value for unphosphorylated eNOS is 1, i.e., that 50% of the reductase domains are in their active conformation in the presence of CaM, then 7- and 15-fold increases in KA/I would result in 88 and 94% of reductase domains, respectively, being in their active conformation. These percentages would not be readily distinguishable in activity assays, which could explain why the S617D substitution and deletion of the autoinhibitory domain can be distinguished on the basis of their effects on EC50(Ca2+) values, but not on the basis of their effects on the maximum CaM-dependent enzyme activity.

Physiological Implications

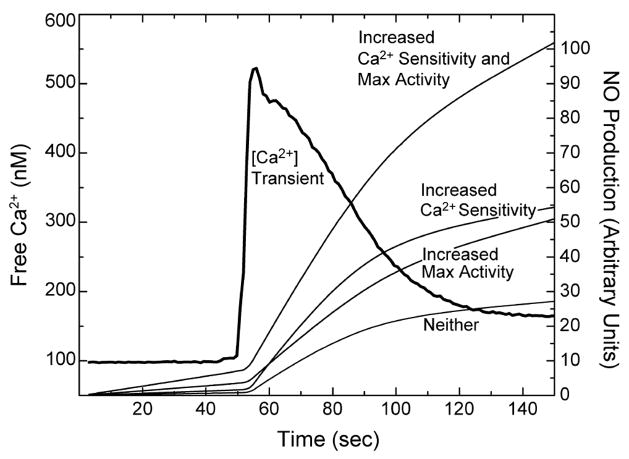

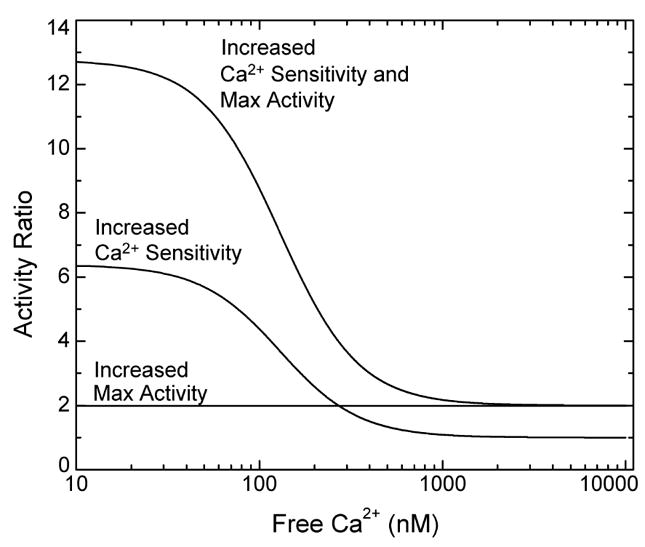

Phosphorylation at Ser-617 has the potential to increase the level of NO production in cells through its effects on the maximum CaM-dependent synthase activity and the Ca2+ dependencies for CaM binding and enzyme activation. To determine the intrinsic Ca2+ dependencies presented in this paper, a molar excess of eNOS over CaM was used, along with total concentrations of CaM and eNOS in the low micromolar range. These conditions are comparable to those in an endothelial cell, where the CaM concentration appears to be limiting and the total eNOS concentration is at ~5 μM (46). Fundamental questions relating to the potential physiological significance of our results are as follows. (1) How much is Ser-617 phosphorylation likely to affect NO production in a cell? (2) How much are phosphorylation-dependent effects on the maximum CaM-dependent enzyme activity and the EC50(Ca2+) values for CaM binding and enzyme activation likely to contribute? One way to address these questions is to calculate the ratio of the synthase activities of the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated enzymes as a function of [Ca2+]free. The three curves presented in Figure 6 were calculated on the basis of the combined effects of the S617D substitution on the maximum activity and the EC50(Ca2+) value for activation and on the basis of only one effect or the other. The effect on the maximum CaM dependent activity was accounted for a factor of 2 and is by definition Ca2+-independent. Thus, the curve calculated on the basis of only this effect is a flat line with a fixed activity ratio of 2 (Figure 6). The decrease in the EC50(Ca2+) value for enzyme activation causes the activity ratio to vary with the Ca2+ concentration. The curve calculated on the basis of only this effect increases from an activity ratio of 1 at [Ca2+]free values of ≥1 μM to a ratio of ~6 at a [Ca2+]free value of 10 nM (Figure 6). The curve calculated on the basis of both effects of the S617D substitution has the same shape, but all of the activity ratios are 2-fold higher. Thus, the activity ratio increases from a value of 2 at [Ca2+]free values of ≥1 μM to a value of ~12 at a [Ca2+]free of 10 nM (Figure 6). According to these calculations, when [Ca2+]free is 100 nM, our estimate of the resting value in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells (Figure 7), the decrease in the EC50(Ca2+) value is the major contributor to an activity ratio of ~8, while at a [Ca2+]free value of ~300 nM, our estimate of the peak value during an agonist-evoked Ca2+ transient (Figure 7), the decrease in the EC50(Ca2+) value and the increase in the maximum CaM-dependent activity contribute equally to an activity ratio of ~4 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Predicted ratios for the activities of Ser-617 phosphorylated and unphosphorylated eNOS plotted vs [Ca2+]free. Calculations were performed using eq 6 and the K1K2 and K3K4 values for S617D and wild-type eNOS listed in Table 2, with the effect of phosphorylation on the maximum CaM-dependent activity included as a factor of 2. Curves were calculated on the basis of the individual and combined effects of the S617D substitution on the Ca2+ sensitivity and maximum enzyme activity, as indicated in the figure.

Figure 7.

Predicted effects of sustained quantitative Ser-617 phosphorylation on NO production in cells. Calculated time courses for NO production before and after addition of 10 nM bradykinin were derived from the Ca2+ transient. The [Ca2+]free time course was calculated from measurements of indo-1 fluorescence in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells made with a time resolution of 0.6 s (46). NO production was calculated at each [Ca2+]free time point using the K1K2 and K3K4 values derived for S617D or wild-type eNOS listed in Table 2, with the effect of the phosphomimetic substitution on the maximal CaM-dependent enzyme activity included as a factor of 2. Time courses were calculated on the basis of the individual and combined effects of the S617D substitution on Ca2+ sensitivity, i.e., K1K2 and K3K4 values, and maximum enzyme activity, as indicated in the figure.

We can also calculate how fixed stoichiometric phosphorylation at Ser-617 is likely to affect the time course of NO production during an agonist-evoked Ca2+ transient. It should be emphasized, however, that in the cell phosphorylation at Ser-617, as well as at other sites in the enzyme, occurs transiently on a time scale of several minutes in response to agonists, so this calculation serves to illustrate only the potential physiological significance of Ser-617 phosphorylation (19). Addition of 10 nM bradykinin to cultured bovine endothelial cells produced the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transient seen in Figure 7. Time courses for NO production were calculated for unphosphorylated eNOS and the S617D enzyme, with the effects of the substitution on the maximum CaM-dependent enzyme activity and the EC50(Ca2+) value for enzyme activation considered separately and together (Figure 7). As seen in Figure 7, the two effects contribute equally to a 4-fold increase in the amount of NO produced.

In vivo measurements suggest that nanomolar concentrations of NO are released from endothelial cells (48), and that increases in dissolved NO in the 10–30 nM concentration range are directly proportional to decreases in vascular smooth muscle tension (49). Our results suggest that Ser-617 phosphorylation has the potential to increase NO production enough to produce significant physiological effects. It is also evident that the apparent effects of phosphorylation on the maximum CaM-dependent enzyme activity and the EC50(Ca2+) value for enzyme activation are both likely to be important physiologically. The apparent effect of Ser-617 phosphorylation on the EC50(Ca2+) value for CaM binding could also play a role by promoting binding of CaM at free Ca2+ concentrations that do not produce significant enzyme activation. This could enhance the activity response to rapid, localized Ca2+ transients by reducing lags associated with diffusional recruitment of CaM by eNOS. Unfortunately, it is difficult even to qualitatively evaluate the relationship between Ser-617 phosphorylation and NO production in an endothelial cell, not only because of the likely involvement of regulatory factors besides Ca2+, CaM, and phosphorylation but also because agonist-evoked changes in eNOS phosphorylation appear to involve temporally complex fractional changes at more than one site, including Thr-497, which must be dephosphorylated for CaM to bind and activate the enzyme (7–9). On the other hand, it is evident that this complex situation will never be fully understood without precisely defining the effects of individual and combined phosphorylations on the activity and Ca2+ dependencies of the CaM–eNOS complex.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; AI, auto-inhibitory domain (bovine residues 595–639) in eNOS; S617D, substitution of an Asp for Ser-617; S635D, substitution of an Asp for Ser-635; S617/635D, substitution of Asp residues for Ser-617 and Ser-635; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; CaM, calmodulin; BSCaMA, fluorescent biosensor containing a CaM-binding sequence based on the IQ domain in neuromodulin; BAPTA, 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin.

References

- 1.Masters BSS, McMillan K, Sheta EA, Nishimura JS, Roman LJ, Martasek P. Cytochromes p450 3. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase, a modular enzyme formed by convergent evolution: Structure studies of a cysteine thiolate-liganded heme protein that hydroxylates L-arginine to produce NO as a cellular signal. FASEB J. 1996;10:552–558. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.5.8621055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moncada S, Palmer RMJ, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: Physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daff S. Calmodulin-dependent regulation of mammalian nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:502–505. doi: 10.1042/bst0310502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishida CR, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Autoinhibition of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. Identification of an electron transfer control element. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14692–14698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venema RC, Sayegh HS, Kent JD, Harrison DG. Identification, characterization, and comparison of the calmodulin-binding domains of the endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6435–6440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M, Vogel HJ. Characterization of the calmodulin-binding domain or rat cerebellar nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:981–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boo YC, Jo H. Flow-dependent regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: Role of protein kinases. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:C499–C508. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00122.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming I, Busse R. Molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:R1–R12. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00323.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mount PF, Kemp BE, Power DA. Regulation of endothelial and myocardial NO synthesis by multi-site eNOS phosphorylation Review. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoyagi M, Arvai AS, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED. Structural basis for endothelial nitric oxide synthase binding to calmodulin. EMBO J. 2003;22:766–775. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer PM, Fulton D, Boo YC, Sorescu GP, Kemp BE, Jo H, Sessa WC. Compensatory phosphorylation and protein-protein interactions revealed by loss of function and gain of function mutants of multiple serine phosphorylation sites in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14841–14849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsubara M, Hayashi N, Jing T, Titani K. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by protein kinase C. J Biochem. 2003;133:773–781. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kou RQ, Greif D, Michel T. Dephosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by vascular endothelial growth factor: Implications for the vascular responses to cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29669–29673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204519200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi Y, Nishio M, Naito Y, Yokokura H, Nimura Y, Hidaka H, Watanabe Y. Regulation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by calmodulin kinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20597–20602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michell BJ, Chen ZP, Tiganis T, Stapleton D, Katsis F, Power DA, Sim AT, Kemp BE. Coordinated control of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation by protein kinase C and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17625–17628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boo YC, Kim HJ, Song H, Fulton D, Sessa W, Jo H. Coordinated regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by phosphorylation and subcellular localization. Free Radical Biol Med. 2006;41:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boo YC, Sorescu GP, Bauer PM, Fulton D, Kemp BE, Harrison DG, Sessa WC, Jo H. Endothelial NO synthase phosphorylated at SER635 produces NO without requiring intracellular calcium increase. Free Radical Biol Med. 2003;35:729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butt E, Bernhardt M, Smolenski A, Kotsonis P, Frohlich LG, Sickmann A, Meyer HE, Lohmann SM, Schmidt HH. Endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (type III) is activated and becomes calcium independent upon phosphorylation by cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5179–5187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.5179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michell BJ, Harris MB, Chen ZP, Ju H, Venema VJ, Blackstone MA, Huang W, Venema RC, Kemp BE. Identification of regulatory sites of phosphorylation of the bovine endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at serine 617 and serine 635. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42344–42351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCabe TJ, Fulton D, Roman LJ, Sessa WC. Enhanced electron flux and reduced calmodulin dissociation may explain “calcium-independent” eNOS activation by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6123–6128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMillan K, Masters BS. Prokaryotic expression of the heme- and flavin-binding domains of rat neuronal nitric oxide synthase as distinct polypeptides: Identification of the heme-binding proximal thiolate ligand as cysteine-415. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3686–3693. doi: 10.1021/bi00011a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roman LJ, Sheta EA, Martasek P, Gross SS, Liu Q, Masters BS. High-level expression of functional rat neuronal nitric oxide synthase in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8428–8432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sessa WC, Harrison JK, Barber CM, Zeng D, Durieux ME, D’Angelo DD, Lynch KR, Peach MJ. Molecular cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15274–15276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finley NL, Rosevear PR. Introduction of negative charge mimicking protein kinase C phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I. Effects on cardiac troponin C. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54833–54840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner LE, II, Li WH, Joseph SK, Yule DI. Functional consequences of phosphomimetic mutations at key cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation sites in the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46242–46252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo H, Gao C, Mi Z, Wai PY, Kuo PC. Phosphorylation of Ser158 regulates inflammatory redox-dependent hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α transcriptional activity. Biochem J. 2006;394:379–387. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Hou Z, He L, Qi RZ. Regulation of s6 kinase 1 activation by phosphorylation at ser-411. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6922–6928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi S, Lee SH, Meng XW, Mott JL, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Craig RW, Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ. Serine 64 phosphorylation enhances the antiapoptotic function of Mcl-1. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610010200. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nusser N, Gosmanova E, Makarova N, Fujiwara Y, Yang L, Guo F, Luo Y, Zheng Y, Tigyi G. Serine phosphorylation differentially affects RhoA binding to effectors: Implications to NGF-induced neurite outgrowth. Cell Signalling. 2006;18:704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolli-Derkinderen M, Sauzeau V, Boyer L, Lemichez E, Baron C, Henrion D, Loirand G, Pacaud P. Phosphorylation of serine 188 protects RhoA from ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2005;96:1152–1160. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000170084.88780.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahin B, Shu H, Fernandez J, El-Armouche A, Molkentin JD, Nairn AC, Bibb JA. Phosphorylation of protein phosphatase inhibitor-1 by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24322–24335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603282200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song Y, Benison G, Nyarko A, Hays TS, Barbar E. Potential role for phosphorylation in differential regulation of the assembly of dynein light chains. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610445200. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Craig TJ, Chen X, Ciufo LF, Takahashi M, Morgan A, Gillis KD. Phosphomimetic mutation of Ser-187 of SNAP-25 increases both syntaxin binding and highly Ca2+-sensitive exocytosis. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:233–244. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huhmer AF, Nishida CR, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Schoneich C. Inactivation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase by peroxynitrite. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:618–626. doi: 10.1021/tx960188t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishida CR, de Montellano PR. Control of electron transfer in nitric-oxide synthases. Swapping of autoinhibitory elements among nitric-oxide synthase isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20116–20124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Black DJ, Leonard J, Persechini A. Biphasic Ca2+-dependent switching in a calmodulin-IQ domain complex. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6987–6995. doi: 10.1021/bi052533w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Persechini A, McMillan K, Leakey P. Activation of myosin light chain kinase and nitric oxide synthase activities by calmodulin fragments. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16148–16154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adak S, Ghosh S, Abu-Soud HM, Stuehr DJ. Role of reductase domain cluster 1 acidic residues in neuronal nitric-oxide synthase. Characterization of the FMN-free enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22313–22320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martasek P, Miller RT, Roman LJ, Shea T, Masters BS. Assay of isoforms of Escherichia coli: Expressed nitric oxide synthase. Methods Enzymol. 1999;301:70–78. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)01070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tran QK, Black DJ, Persechini A. Dominant affectors in the calmodulin network shape the time courses of target responses in the cell. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Black DJ, Tran QK, Persechini A. Monitoring the total available calmodulin concentration in intact cells over the physiological range in free Ca2+ Cell Calcium. 2004;35:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Persechini A, Lynch JA, Romoser VA. Novel fluorescent indicator proteins for monitoring free intracellular Ca2+ Cell Calcium. 1997;22:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Black DJ, Selfridge JE, Persechini A. The kinetics of Ca2+-dependent switching in a calmodulin-IQ domain complex. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13415–13424. doi: 10.1021/bi700774s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tran QK, Black DJ, Persechini A. Intracellular coupling via limiting calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24247–24250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao YT, Panda SP, Roman LJ, Martasek P, Ishimura Y, Masters BSS. Oxygen metabolism by neuronal nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7921–7929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ignarro LJ, Byrns RE, Buga GM, Wood KS, Chaudhuri G. Pharmacological evidence that endothelium-derived relaxing factor is nitric oxide: Use of pyrogallol and superoxide dismutase to study endothelium-dependent and nitric oxide-elicited vascular smooth muscle relaxation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]