Abstract

Time-dependent phenotypic response of a model osteoblast cell line (hFOB 1.19, ATCC, CRL-11372) to substrata with varying surface chemistry and topography is reviewed within the context of extant cell-adhesion theory. Cell-attachment and proliferation kinetics are compared using morphology as a leading indicator of cell phenotype. Expression of (α2, α3, α4, α5, αv, β1 and β3) integrins, vinculin, as well as secretion of osteopontin and type I collagen supplement this visual assessment of hFOB growth. It is concluded that significant cell-adhesion events – contact, attachment, spreading, and proliferation – are similar on all surfaces, independent of substratum surface chemistry/energy. However, this sequence of events is significantly delayed and attenuated on hydrophobic (poorly water-wettable) surfaces exhibiting characteristically low-attachment efficiency and long induction periods before cells engage in an exponential-growth phase. Results suggest that a ‘time-cell-substratum compatibility-superposition-principle’ is at work wherein similar bioadhesive outcomes can be ultimately achieved on all surface types with varying hydrophilicity, but the time required to arrive at this outcome increases with decreasing cell-substratum compatibility. Genomic and proteomic tools offer unprecedented opportunity to directly measure changes in the cellular machinery that lead to observed cell responses to different materials. But for the purpose of measuring structure-property relationships that can guide biomaterial development, genomic/proteomic tools should be applied early in the adhesion/spreading process before cells have an opportunity to significantly remodel the cell-substratum interface, effectively erasing cause-and-effect relationships between cell cell-substratum compatibility and substratum properties.

Impact Statement

This review quantifies relationships among cell phenotype, substratum surface chemistry/energy, topography, and cell-substratum contact time for the model osteoblast cell line hFOB 1.19, revealing that genomic/proteomic tools are most useful in the pursuit of understanding cell adhesion if applied early in the adhesion/spreading process.

Keywords: Cell adhesion, surface chemistry, surface energy, cell-substratum compatibility, hFOB, osteoblast

1. Introduction

Adhesion and proliferation are fundamental eukaryotic (mammalian) cellular processes involved in embryogenesis, immune response, tissue maintenance, and would healing [1]. Cell contact, attachment, and subsequent adhesion of anchorage-dependent cells are among the first phases of cell-material interactions [2, 3] that profoundly influence integration with tissue and eventual success or failure of a broad range of implanted biomaterials. For these reasons, as well as a compelling need to understand prokaryotic adhesion and surface colonization, cell adhesion has been a focus of research for nearly 50 years. Cell adhesion research has involved a unique collaboration between biologists and chemists/physicists specializing in material and surface sciences. As a consequence, a vast literature has arisen over these decades that has been the subject of a number of very good reviews (see, for examples, refs. [2, 4–13]). This literature attempts to find relationships between material properties (surface chemistry, energy, and morphology) and bioadhesive outcomes by integrating physicochemical and biological approaches to the problem. The widespread use of many different kinds of materials in biomedical, biotechnical, and engineering applications where cell adhesion is important bears witness to the significant progress that has been made in controlling cell adhesion. However, at a fundamental level, cell adhesion remains poorly understood. Cellomic, proteomic, and genomic tools offer new insights into changes in the regulation of the cell machinery responsible for observed adhesive outcomes in contact with different materials. This information will revolutionize our understanding of cell adhesion at the intra-cellular level. How this information might help interpret cell-substratum compatibility (a.k.a. cytocompatibility) is a particular focus of this review.

As a means of making our objectives tractable, we focus on the specific case of osteoblast adhesion to different materials, which is of significance to the fast-growing fields of orthopedic biomaterials and musculoskeletal tissue engineering [14]. Rapid growth of these fields can be traced to the demographic facts that extended human-life span and higher-activity levels at older age have greatly increased need for orthopedic healthcare [15–18]. Improved hard-tissue repair, augmentation, or replacement has thus become a very significant challenge for orthopedic biomaterials and orthopedic surgery [19–21]. Meeting these challenges depends, in part, on establishing firm relationships between implant success and orthopedic biomaterial properties (so-called structure-property relationships) that can guide the design process. These structure-property relationships critically depend on a thorough understanding of the adhesion of hard-tissue cells (osteoblasts, osteoclasts, chondrocytes, etc.) to artificial materials.

Various model osteoblasts have been introduced and used to gain insight into the bone-cell response to candidate orthopedic biomaterials in vitro. The most widely used model cells are primary cultures derived from normal human and rodent bone fragments, or osteosarcoma cell lines generated from human-bone tumors. Each of these cell sources has strengths and limitations for studying the cell adhesion of osteoblasts in vitro [22–25]. For example, primary-human osteoblasts have a normal osteoblastic phenotype; but these cells are typically quite fastidious in vitro, grow very slowly, and have a limited life span when successfully brought into culture. Cultures derived from rodent generally circumvent these problems but may not be appropriate models for humans due to trans-species differences in phenotypic characteristics. Osteosarcoma cell lines derived from spontaneous tumors are readily grown in vitro, proliferate endlessly, but do not exhibit a normal phenotype. Worse perhaps, osteosarcoma cells respond abnormally to various hormones and cytokines compared to normal, differentiated human osteoblasts. In effort to overcome these limitations, Harris et al [24] established a conditionally-immortalized, human-fetal-osteoblast cell line, hFOB 1.19 that was stably transfected with a gene coding for a temperature-sensitive mutant (tsA58) of the SV40 large T antigen. Resultant hFOB cells express osteoblast-specific phenotypic markers and mineralize extracellular matrix. Later, Subramaniam et al [25] characterized hFOB 1.19 as an immortalized, but non-transformed, cell line with minimal chromosome abnormalities and normal spectrum of matrix proteins. Because of these inherent qualities, we have chosen to restrict this review to the behavior of hFOB 1.19 in contact with substrata with different surface-chemical and topological features. This restriction has the obvious benefit of sharply focusing scope of the review to only a few investigators, but is at the acknowledged expense of excluding a burgeoning literature describing the behavior of other osteoblast cell types; especially the popular murine calvaria cell line MC3T3-E1 (ATCC CRL-2593). We hope that these omissions do not seriously compromise utility of the work, which is as much aimed at finding new directions in cell adhesion as summarizing/condensing knowledge acquired over the last decade or so on osteoblast interactions with biomaterials.

We begin this review by broadly categorizing experimental and theoretical approaches to the cell adhesion problem that have been taken over the years, attempting to place how genomics and proteomics can best provide new information in the prospective design of orthopedic biomaterials. Specific studies of osteoblast interactions with materials are then summarized with the objective of extracting insights into the short- and long-term influence surface properties can have on model osteoblasts. A general conclusion drawn from data at hand is that gene regulation responsible for adhesion selectivity among surface chemistries/energies is incisive at early stages (< 3 days) of cell-surface interactions and will require focused experimental strategies to clearly observe.

2. A Reflection on Cell adhesion

2.1 Cell adhesion Theories

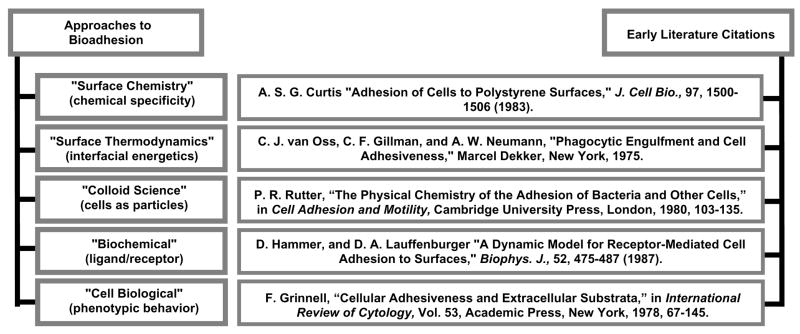

Fig. 1 coarsely categorizes different approaches that have been taken to the problem of cell adhesion, along with some early (but not necessarily first) literature citations that, in the authors’ view, are archetypes for work that was to follow along the same theme. In the early years, say 1960’s through mid 1980’s, there was enthusiasm that cell adhesion could be substantially understood using colloid science, surface chemical, and surface thermodynamic principles (the pioneering 1924 work of Mudd and Mudd [26, 27] in bacteria adhesion was possibly the first application of surface thermodynamics to cell adhesion). A number of imaginative physicochemical theories were developed to explain the cell adhesion process [4–8, 28–33] with the goal of establishing a predictive basis for optimizing biocompatibility – or at least a rational basis for explaining how substratum surface properties so profoundly affect cell-material interactions. Although some of these theories have been useful in separating and weighing the relative importance of various material properties (such as charge, wettability, surface density of cell-binding ligands, etc.), it seems clear now that cell-substratum interactions ranging from cell-surface contact through proliferation to chronic cell-material interaction are far too complex to be meaningfully embraced by relatively simple mathematical models.

Figure 1.

Different approaches to bioadhesion with some archetypical literature citations. Each of these approaches effectively probe different phases of bioadhesion and describe cell adhesion in different terms.

Also in these early years, experiment revealed a strong dependence of cell adhesion/proliferation on substratum surface chemistry, giving rise to the expectation that cell adhesion could be understood using surface-chemical principles. Rappaport’s early 1970’s work was among the earliest studying surface-chemical effects on mammalian cell adhesion [34]. Soon after, a variety of surface-synthesis strategies were explored, ranging from use of liquid-phase chemical oxidants [35, 36] to application of gas-discharge treatments [37] now commonly employed in the commercial production of disposable plastic tissue cultureware [38]. Evidence mounted supporting the idea that a particular surface functional group – hydroxyl or carboxyl for example – was particularly stimulatory to cell adhesion and proliferation [39–43] over other functional groups. However, it has proven difficult in subsequent research to clearly separate cause-and-effect in the cell adhesion/proliferation process, especially in the ubiquitous presence of proteins, and by doing so, unambiguously separate surface chemistry from all other influences (such as surface energy/water wettability) [44]. The most general rule connecting material properties with cell-substratum compatibility emerging from decades of focused research is that anchorage-dependent mammalian cells (those requiring substratum adhesion for proliferation) favor modestly water-wettable or hydrophilic surfaces exhibiting a water contact angle θ <60° [9, 10, 31, 33, 38, 45–47]. No doubt surface chemistry and wettability are inextricably convolved properties because it is the hydrogen bonding of water to surface functional groups that most profoundly influences wettability (see, as examples, refs. [38, 46, 48]).

Viewed from a purely biological perspective, cell adhesion is all about how cells respond to different surfaces as measured by various morphological and/or phenotypic markers. Grinnell’s 1978 classic published in International Review of Cytology [2] traced cell morphology and ultra-structure through different stages of adhesion and dependence on substratum properties. The role of various receptors and adsorbed ligands became evident in this era, ultimately identifying a pantheon of ‘adhesins’ that rather quickly dominated cell adhesion thought [49–51]. Interest in, or even remembrance of, physicochemical and surface-science theories faded very quickly; even though it is self-evident that biology, biochemistry, and physics are simultaneously operative at some level. Perhaps Hammer and Tirrell [11] captured it best with the words “…specific recognition between reactive biomolecules or receptors occurs against a backdrop of polymeric and long-range nonspecific forces.”

Different approaches to cell adhesion captured in Fig. 1 effectively study different facets of a multi-faceted cell adhesion problem that become more-or-less important at various stages of cell adhesion. For example, there can be little doubt that surface chemistry, colloid forces, and surface thermodynamics are more important earlier in the process than later. Thus, an unsolved problem in cell adhesion is to integrate these separated temporal views in a way that establishes how preceding stages of cell-surface interaction influence succeeding stages. Pursuing the example mentioned above a bit further to illustrate this latter point, it is evident that colloid science considers only forces between cell and surface that occur in close proximity – but not contact – whereas surface thermodynamics contemplates the energetics of interface formation and destruction commensurate with intimate cell-surface contact [38]. Thus, colloidal principles might speak volumes about the forces that bring cells to within a few tens-of-nanometers of a surface but colloid science is silent about the adhesion process itself. Conversely, surface thermodynamics might address cell-surface adhesivity but says nothing about getting the cell close enough to the surface to actually form a cell-surface interface. A connecting theory is required to bring these parts of the problem together and explain how the surface-contact step can influence final adhesion. Modified colloid and surface-thermodynamic theories might indeed build such a bridge [31, 33], but the span between the physics and biology appears much, much broader. Worse, it is not yet apparent what kind of information can fill this physics-biology gap or how closure can be accomplished in terms that relate materials properties to cell-substratum compatibility.

2.2 Cell Attachment and Proliferation Kinetics

Cell biologists view the adhesion of anchorage-dependent mammalian cells to a substratum surface as occurring in four major steps that precede proliferation: protein adsorption, cell-substratum contact, cell-substratum attachment, and cell adhesion/spreading [2, 9, 31, 33]. Protein adsorption is complex in its own right, involving molecular-scale interactions with a hydrated surface that no doubt transpire nearly instantaneously relative to the timeframe of cell adhesion (see, as examples drawn from many, refs. [52, 53]). Cell contact and attachment involves gravitation/sedimentation to within 50 nm or so of a surface whereupon physical and biochemical forces conspire to close the cell-surface distance gap. Initial cell contact with the substratum presumably occurs by extension of filopodia that penetrate an electrostatic barrier between cell-and-substratum surfaces that usually bear similar net-negative charges [2, 38]. Filopodia attach firmly to the substrate and play an important role in orienting cells on the surface and begin the process of customizing the substratum for improved cell adhesion (see refs. [2, 54] for reviews). Time required to complete contact-and-attachment steps in a simple, stagnant culture-dish arrangement is usually of the order of 30 min for typical soft-tissue cells [45] (see also Fig. 2), but clearly depends on a complex interplay between cell, surface, and suspending fluid-phase composition [38] in a manner that has been only partially described by aforementioned colloid and surface-thermodynamic theories. Adherent cells then slowly (typically within hours) spread over the surface, depending on compatibility with the surface, expressing a strong ‘biological component of adhesion’ [38] that includes secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM) and results in the flattening of cells on the substratum [2] (spread-cell length is about 3–10 times height [9]). Needless to say, (protein) composition of the fluid phase can greatly affect the entire cell adhesion process [31, 33, 55–59]. Thus, it is apparent that the short-term (<3 days) cell adhesion/proliferation process spans a broad range of time and length scales. As a consequence, the biophysics of cell adhesion is very complex and any successful model of cell adhesion must address this multi-scale aspect of the problem.

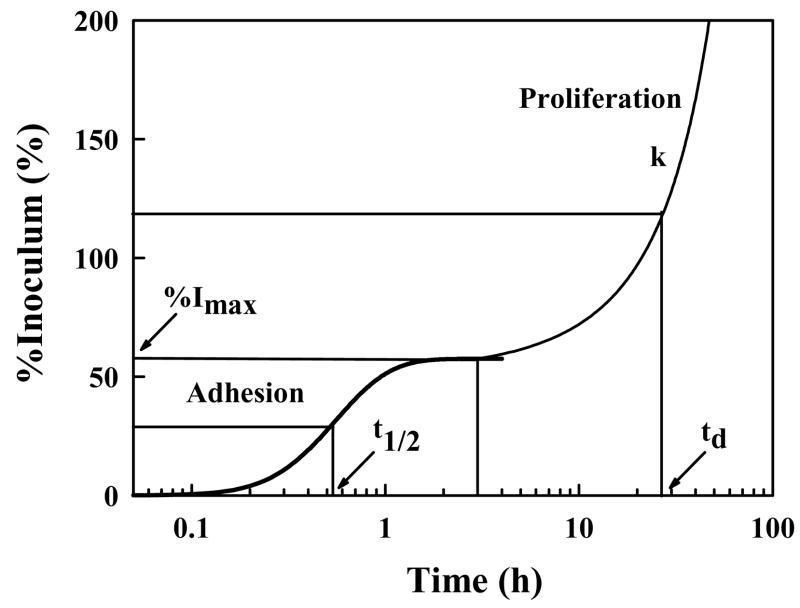

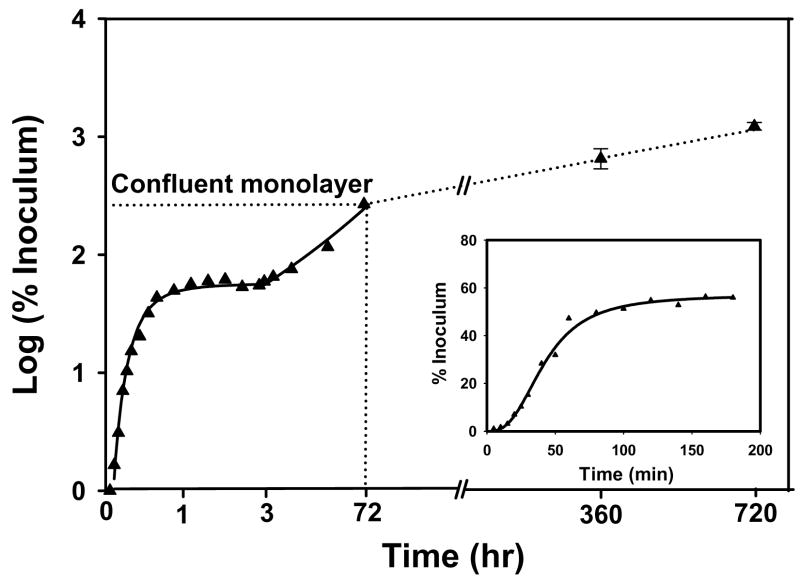

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of cell adhesion and proliferation kinetics identifying quantitative parameters that can be extracted from measurement of number of attached cells (expressed here as percentage of (viable) cell inoculum; %I) with time. %Imax is the maximum percentage of a cell inoculum that adheres to a surface from a sessile cell suspension and t1/2 measures half-time to %Imax. The proliferation rate (k) and cell-number doubling time (td) measure viability of attached cells (adapted from ref. [60]).

Fig. 2 sketches a generalized kinetic profile representing short-term cell adhesion/proliferation typically observed for the adhesion of mammalian cells to planar surfaces from a stagnant fluid phase (e.g. plating cells into petri dishes or tissue-culture flasks). Fig. 2 plots attached-cell-number (expressed as % of originating cell inoculum) as a function of time [14, 45, 46, 60, 61]. Annotations on Fig. 2 indicate a number of quantitative parameters than can be extracted from experimental data comprising such a kinetic analysis. These parameters include time-to-half-maximal attachment t1/2 and maximal attachment %Imax. %Imax is defined by a steady-state attachment plateau that has been interpreted as either a pseudo-equilibrium partitioning between attached and suspended cells [38, 45, 62] or a kinetic-saturation phenomenon [63–66]. This steady state precedes cell spreading and, after a dwell time (which can also be quantified), adherent cells replicate with proliferation rate k and a characteristic population doubling time td. As will be discussed subsequently, each of these attachment/proliferation parameters is quite sensitive to surface chemistry and protein/surfactant composition of the fluid phase [31, 33], as well as being diagnostic of cell-substratum compatibility [45, 46].

The whole kinetic process sketched in Fig. 2 is not frequently measured, especially the early attachment phase characterized by t1/2 and %Imax, because cell-enumeration protocols are quite labor intensive (there are a variety of cell-enumeration methods available including dye techniques [67–74], autoradiography [75], light and electron microscopy [76–78], Coulter counting [79], hemocytometry [80], spectrometry [81, 82], nuclei number [83], total DNA [84], total protein concentration [78, 85] that may or may not give similar results, depending on cell number and specific experimental conditions). Instead, a variety of experimental short-cuts are taken, such as measuring attached-cell-number after some arbitrary cell-surface contact time [86–89]. In many instances, the fluid-phase composition is changed mid-way through the cell-attachment assay, as by discarding unattached cells or changing protein composition, which can completely change the biophysics of the adhesion process. The wide variety of methods used makes it very difficult to compare results from different protocols or research groups. It is thus not always clear how measured cell-adhesion parameters correlate, or even if these different parameters are at all related. This complexity in the literature is exacerbated by the fact that there are a number of methods of assessing cell-surface interaction that do not fall in the category of cell-attachment kinetics. These include measurement of cell spreading [90–92], cell interfacial energy [93], forces required to dislodge adherent cells [94–96], and use of detachment indices [97].

2.3 The Cell Morphological Response to Materials

The most obvious and striking difference in cell behavior on different materials is cell shape (morphology). Variations in cell morphology can be observed by light and electron microscopy assisted with various cytoskeletal stains such as actin and vinculin stains [61, 77, 89, 98–102]. Morphological changes can be quantified by using image analysis that reports dimensional parameters such as cell area, perimeter, Feret’s diameter, circularity and coverage per unit surface area.

Anchorage-dependent cells attached to a surface that supports cell growth undergo a progressive process of flattening from a very-nearly spherical shape to discoid, as was well described in Grinnell’s 1978 review [2]. During this shape change, adhesion to the surface is mediated by formation of focal adhesions and plaques constructed from an assembly of transmembrane integrins that anchor the cytoskeleton to extracellular matrix (ECM) secreted by surface-bound cells. Related to Fig. 2, these events occur well after steady-state adhesion has been achieved but before the exponential-growth phase. Vogler has emphasized that this ‘biological component of the work of adhesion’ [38] expresses itself much later than the operative timeframe of physical forces that bring cells from suspension in media to the substratum surface. Using detergent solutions (Tween-80; polyoxyethylene sorbitan monooleate) to vary liquid-phase interfacial tension or to match that of serum-containing medium, it has been shown that all phases of cell contact through attachment observed in cell-culture medium could be observed in absence of proteins [31, 33]. Of course, attached cells ultimately die in the absence of serum (or defined-media) proteins, but cells attached from detergent solutions apparently grow quite normally if the detergent solution is replaced with serum-containing medium soon after cells reach the attachment steady-state (Vogler, unpublished work). All of this suggests that the early-attachment phase does not include significant ECM production but rather is dominated by physical forces.

Cell-attachment time is clearly an important variable in the correlation of cell morphology to substratum characteristics -- chemical or topological. Our experience with hFOB summarized in the next section suggests that the general sequence of events, from round cells to flat, is substantially independent of the overall cell-substratum compatibility. On surfaces exhibiting poor cell-substratum compatibility (typically hydrophobic, see Figs. 3,4,5), cells remain rounded for an extended period of time compared to more compatible surfaces (typically hydrophilic). But if cells on poorly compatible surfaces survive, even if just barely, flattening and eventual population of the surface occurs. Thus, expression of morphological traits may be viewed as delayed on poorly-compatible surfaces, a kind of time-cell-substratum compatibility-superposition-principle, that suggests cells are engaged in an extended process of secreting ECM to compatibilize the surface.

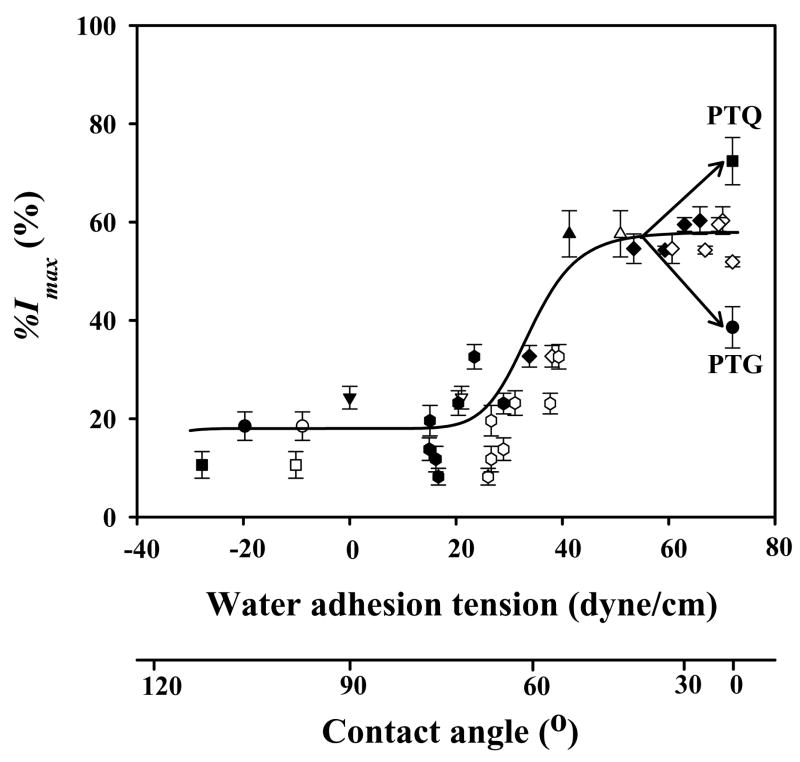

Figure 3.

Correlation of % I max (see Fig. 2) with substrata surface energy for hFOB. Surface energy is here measured by water adhesion tension , where at 20° C for pure water and θ is the angle subtended by a water droplet on the surface understudy (advancing θ = filled symbols, receding θ = open symbols; adapted from ref. [60]). Error bar represents standard deviation (N ≥3). Trend-line through advancing and receding data is guide to the eye; ▲= TCPS; ▼;= BGPS (bacteriological grade polystyrene); ● = glass; ■= quartz; ◆ = PTPS (plasma-treated polystyrene); ⬢ = biodegradable polymers of PLGA 5/5 (Mn = 80 k), PLGA 7/3 (Mn = 96 k), PLA (Mn = 160 k), PCL (Mn = 80 k), PLCL 7/3 (Mn = 82 k), PLGCL 2.5/2.5/5 (Mn = 60 k), PLGCL 3.5/3.5/3 (Mn = 54 k). Mn = number-average molecular weight by GPC. PLGA = poly(lactide-co-glycolide); PLCL = poly(lactide-co-caprolactone); PLGCL = poly(lactide-co-glycolide-co-caprolactone). See ref. [60] for details on materials preparation and characterization.

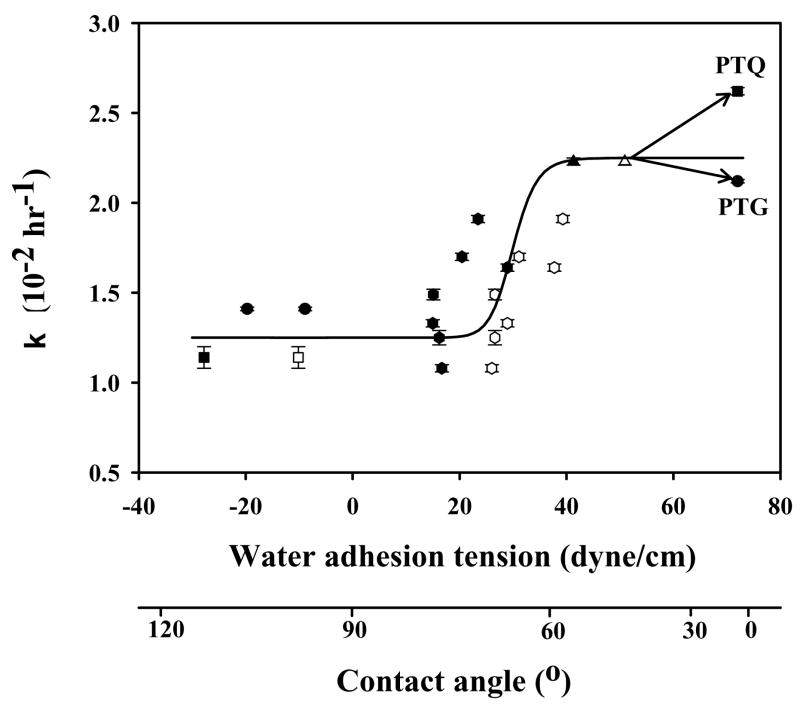

Figure 4.

Correlation of cell proliferation rate constant k with substratum surface energy for hFOB. Surface energy is here measured by water adhesion tension , where at 20° C for pure water and θ is the angle subtended by a water droplet on the surface understudy (advancing θ = filled symbols, receding θ = open symbols; adapted from ref. [60]). Error bars represent standard deviation of N ≥ 3. Trend-line through advancing and receding data is guide to the eye. Material identification is the same as in Fig. 3.

Figure 5.

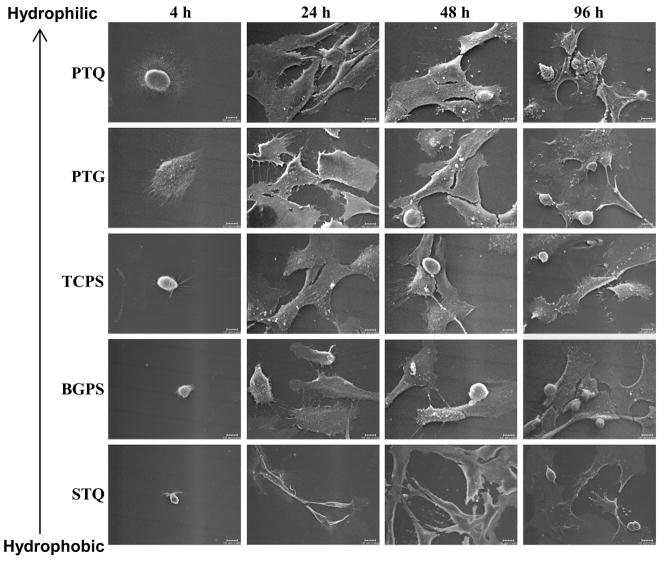

Variation in hFOB morphology on different surfaces after 4, 24, 48, and 96 hours of culture as assessed by SEM (hydrophilic surfaces: PTQ = plasma-treated quartz, PTG = plasma-treated glass, TCPS = tissue-culture grade polystyrene; hydrophobic surfaces: BGPS = bacteriological grade polystyrene, STQ = silane-treated quartz). Scale bar = 10 μm. Note that variation in cell morphology abates with time, especially for hydrophobic specimens.

2.4 Genomic and Proteomic Tools in the Study of Cell adhesion

Modern genomic and proteomic tools offer unprecedented opportunity to directly measure changes in the cellular machinery that lead to the observed cell response to different materials. Perhaps these powerful methods will provide new information that can fill the physics-biology gap mentioned above, or at least yield insights into how closure can be accomplished in terms that relate materials properties to cell-substratum compatibility. The objective here is to systematically relate material properties to the regulation of important genes that ultimately control cell vitality and evolution of phenotype. But before the genomic/proteomic revolution can transform our basic understanding of cell-substratum compatibility, especially as it relates to material properties, we need to know which of the plethora of genes and proteins should be monitored and over what time frame.

Time quite clearly plays an important role in cell adhesion of mammalian cells. It seems safe to guess that gene regulation during these different phases of adhesion would be likewise quite different, leading directly to the expectation that the outcome of genomic/proteomic analysis will strongly depend on when in the cell adhesion process these tools are used. For the purpose of illustrating this important point, it seems useful to speculate when genomic/proteomic studies might yield results that would correlate most strongly with substratum surface properties. According to the preceding discussion, biophysical chemistry dominates the initial phases of cell-surface contact and attachment, at least as it occurs in the highly simplified case of cell adhesion to a culture dish from a sessile fluid phase. Perhaps cell machinery is in idle during this phase awaiting the signal to manufacture ECM and integrins that will mediate/moderate adhesion in subsequent stages of cell adhesion. If this is the case, little-or-no useful information from genomic/proteomic tools would be anticipated at this very early stage of cell adhesion (to say nothing of the experimental difficulties associated with data acquisition). Later, say within the first 4 hours of attachment to a cell-compatible surface such as ordinary tissue-culture labware, strong up-regulation of genes responsible for production of ECM and various integrins would be anticipated. Perhaps the extent of up-regulation would correlate with substratum surface properties in a manner that might suggest cause-and-effect relationships that can serve as the basis of material design. Still later, say within 4 <t <72 hours when cells begin to proliferate and are consequently preoccupied with mitosis, substratum-specific gene regulation might be quite challenging to detect. But data summarized in section 3.1 shows there are significant differences in proliferation rates, at least for hFOB 1.19, suggesting that this phase of cell adhesion would nevertheless be a likely target for the application of genomic/proteomic tools. Finally, in the post-mitotic period (t > 72 hours) when adherent cells begin to express normal physiological processes (such as mineralization of the surrounding ECM) surface properties might only weakly correlate with substratum surface properties. Here too, the time-cell-substratum-compatibility-superposition-principle mentioned in preceding section should be borne in mind because timing of these phases of adhesion are accordingly shifted to longer times on poorly cytocompatible surfaces and so gene regulation would presumably be shifted in time as well. Of course, all of this discussion is highly speculative because focused studies have not yet been carried out with any particular material, let alone with materials bearing systematically varied surface properties. Studies reviewed in the next section just begin to provide some of this information.

3.0 Influence of Substratum Surface Chemistry/Energy and Topography on the Cell adhesion of Human Fetal Osteoblastic Cell Line hFOB 1.19

Time-dependent phenotypic response of hFOB 1.19 (ATCC, CRL-11372) to substrata with varying surface chemistry and topography is reviewed in this section in light of the cell adhesion theory outlined in the preceding section. Osteoblasts exhibit many, if not all, of the general bioadhesive characteristics of other mammalian (soft tissue) cells, plus some interesting peculiarities presumably specific to osteoblasts. As a consequence, an implicit assumption prevailing in the literature is that surface-engineering methods applied to improve soft-tissue-cell cell adhesion (modification of surface chemistry, surface energy/wettability) can be likewise used to improve osteoblast adhesion to, and proliferation on, orthopedic biomaterials in vivo. In addition to these standard surface-engineering methods, precision engineering of surface topography is an alternative receiving considerable interest in orthopedic biomaterials because of the contemporaneity among nanoengineering, nanomedicine [103–105], and the demand for improved orthopedic healthcare mentioned in the Introduction. In principle, surface topography and surface chemistry can be varied independently but, in practice, this is difficult to do and even more difficult to prove that chemistry and topography are actually independent parameters. This latter issue has been become a matter of academic interest in the emerging field of nanomedicine. Pragmatically, in may not be so important how cell-substratum compatibility is influenced as long as this surface engineering reproducibly leads to improved material characteristics. But for the purpose of prospective (rather than accidental) design of orthopedic biomaterials, it is critical to evaluate which of the aforementioned surface characteristics are most influential. Careful evaluation of cell adhesion kinetics, morphology, and application of genomic/proteomic tools outlined in the preceding section are key to understanding osteoblast response to orthopedic biomaterial characteristics.

3.1 Short-Term Adhesion and Proliferation of hFOB on Different Surfaces

Lim et al. [14, 60, 61] found that hFOB adhesion efficiency (%Imax indicated in Fig. 2) strongly correlated with substratum wettability, with high-rates-of-cell-attachment on relatively hydrophilic surfaces (τo > 30 dyne/cm or a nominal contact angle θ < 65°) and low-attachment rates on hydrophobic surfaces (τo < 30 dyne/cm or a nominal contact angle θ > 65°; where is the adhesion tension of pure water with interfacial tension subtending a contact angle θ on the substratum surface; see refs. [38, 48] for a discussion of biomaterial wetting properties and ref. [106] for use of hydrophilic/hydrophobic terminology applied to biomaterials). A variety of materials were examined, including silane-treated glass and quartz (STG, STQ), polylactide/glycolide-based biodegradable polymers, bacteriological-grade polystyrene cultureware (BGPS), and tissue-culture grade polystyrene cultureware (TCPS). Lim et al. made no overt attempt to control surface texture in these studies, or any particular effort to characterize adventitious surface rugosity. It is probably safe to assume that these materials were rough at the sub-micron level and surface texture was more-or-less random. Lim’s work has been confirmed by subsequent analysis that focused in the hydrophilic end of the wetting scale. Fig. 3 compiles unpublished results (Vogler) showing that incremental increase in PTPS wettability (by air-plasma-discharge treatment) over the range 42 < τo ≤ 72.8 dyne/cm range did not measurably increase hFOB attachment efficiency over TCPS (Corning TCPS control surfaces exhibited an advancing water contact angle θa=55° and receding contact angle θr=45°). In this regard, hFOB results mirror those obtained with epithelioid and fibroblastic soft-tissue cells [31, 33, 45]. However, a noticeable attachment preference of hFOB for fully-water-wettable quartz (air-plasma treated, PTQ) and discrimination against fully-water-wettable glass (air-plasma treated, PTG) relative to TCPS seems to be unique for hFOB compared with soft-tissue cells [60] and possibly generic to osteoblasts. This significant difference in hFOB attachment efficiency to surfaces exhibiting the same nominal surface wettability might be due to cytotoxicity of ordinary SiOx glass [107, 108] that inhibits early stages of cell adhesion. But the cause of the attachment preference for the quartz surface chemistry (> 99.99 % SiO2) remains unresolved. Nevertheless, this glass/quartz difference is an example where substratum chemistry apparently plays an important role in cell adhesion, quite independent of water wettability.

Interestingly, cell-proliferation rates also correlated with substratum surface wettability, as shown in Fig. 4. This correlation suggests that the cellular machinery responsible for replication is affected by surface chemistry/energy, well after the contact-and-attachment phase occuring within the 0 ≤t ≤2 hour timeframe (see also Fig. 2). No doubt gene regulation associated with proliferation is in high gear, leading to the speculation that many interesting differences in the cell-substratum compatibility of various materials could be detected using genomic/proteomic tools within this early phase of cell-surface interaction, as discussed in section 2.4. The word “speculation” is purposefully chosen here because, although it makes intuitive sense that gene regulation at this stage in cell-substratum interaction should be quite different from that observed in confluent cells, to our knowledge no such measurements have actually been made. The reward for such experimentally-challenging research should be observation of large differences among cells on different materials that is not observed at later times; even at the extremes of surface energy. That is to say, the opportunity to correlate material properties with expression of proteins important in the adhesion process may be in the exponential-growth phase that follows steady-state attachment (see Fig. 2).

Returning to Fig. 4, it is interesting to note that whereas the proliferation rate k on PTQ was measurably faster than TCPS, reflecting differences observed in attachment rate discussed above, proliferation on PTG was approximately the same as TCPS. Perhaps this suggests that attachment efficiency %Imax and proliferation rate k are independent parameters in certain circumstances measuring different aspects of cell-surface compatibility. Stepping back from these details momentarily, it is quite striking from Figs. 3 and 4 that hFOB response to surface energy pivots near τ0 ~ 30 dyne/cm (θ ~ 60°), as has been observed for a variety of soft-tissue cells (and some prokaryotes, see refs. [46, 47]). Vogler attributes this to the behavior of water at surfaces [47] that profoundly influences protein adsorption, among other important physicochemical phenomenon. Perhaps vicinal water is the medium through which cells sense physical properties of articifical surfaces in forced contact: surface chemistry/energy affects the aqueous pericellular milieu immediately contacting attached cells and cells respond accordingly (see ref. [47] for more disucssion). Clearly, this will remain only so much speculation until we can measure the intra-cellular response to different materials to see if there is any correlation with contacting surface energy and behavior of water at these surfaces [46, 47].

Hendrich et al [74] were among the first to measure osteoblast response to purposely-textured surfaces. They found measurably higher hFOB proliferation on a relatively smooth titanium surface and lower cell proliferation on relatively rough CoCrMo alloy surfaces. However, hFOB was found to proliferate at similar rates on CoCrMo and stainless steel surfaces, even though these two surfaces had significantly different roughness. Hao et al [109] studied hFOB proliferation on Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy surfaces with different rugosity, modified either mechanically or with a high-power diode laser. Cell growth increased considerably on the laser-treated titanium alloy surfaces and slightly on the mechanically roughed surface (compared to untreated surfaces). However, it was observed that contact angles decreased (water wettability increased) with either laser or mechanical treatment (presumably due to an increase in oxygen content on treated surfaces), indicating both topographic and surface-chemical modification. Lim et al [110, 111] recently reported studies of hFOB adhesion and proliferation on polymer systems with varying surface texture, chemical composition, and wettability. As surfaces varied from smooth-to-textured with different topographic feature scale, hFOB adhesion was observed to exhibit statistically-significant differences in cell-substratum compatibility; although the full range in adhesion efficiency varied only about 20% among surfaces studied. Authors noted that “…various biomaterial characteristics (topography, surface chemistry/energy) are intercorrelated”, emphasizing the point made early in this section that it is difficult to deconvolve impact of topography from surface chemistry/energy on cell adhesion/cell-substratum compatibility.

3.2 Morphological Response of hFOB to Different Surfaces

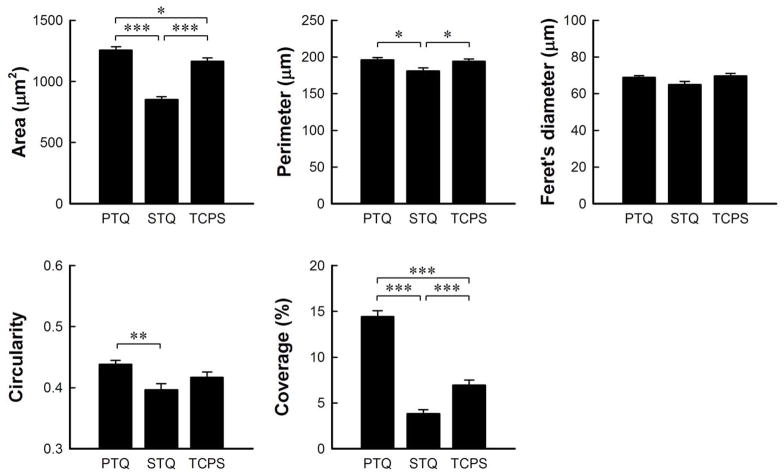

Lim et al. [61] examined differences in cytoskeletal features of hFOB cultured on surfaces with different surface energy at different culture intervals (3 hours, 1 day, 3 days) by actin/integrin immunofluorescence staining. This work demonstrated remarkable morphological difference between cells on hydrophilic and hydrophobic substratum at equivalent times. Cells cultured on plasma-treated quartz (PTQ, hydrophilic) displayed distinct, large plaques of integrins (αv and β3 subunits) co-localized with actin stress fibers whereas there was much less development of these adhesion structures on silane-treated quartz (STQ, hydrophobic). These observations motivated further examination of cell morphology on substrata with varying surface energy and as a function of time in an attempt separate surface energy and time-in-culture effects. Fig. 5 compares hFOB cultured on PTQ, PTG, TCPS (relatively hydrophilic), BGPS and STQ (relatively hydrophobic) for 4, 24, 48 and 96 hours (compare to cell attachment kinetics of Figs. 2,3). Initially-attached cells observed by light microscopy were distributed randomly on all surfaces (not shown). After 4 hours, hFOB reached maximal attachment on all surfaces and were found to be significantly more spread on PTQ and PTG than on TCPS, BGPS and STQ. Notice from Fig. 5 that attached-cell shape is dramatically affected by surface energy, increasing in size with hydrophilicity from a dimension similar to that of a cell in suspension (≤10μm) on STQ. Filopodia extend in all directions from hFOB on PTQ, PTG, and TCPS but there were relatively fewer filopodia extending from hFOB on hydrophobic BGPS and STQ that were more directionally oriented as if emanating from a single point of attachment. Examination of a large number of such micrographs revealed that hFOB morphology on PTG was more variable than on other surfaces, as illustrated in Fig. 6, possibly correlating with the observed cytotoxicity of glass mentioned in section 3.1. After 24 hours, hFOB on all surfaces became more elongated and flattened. Cells were fully spread and in close contact by extended filopodia on PTQ, PTG and TCPS, but some cells on BGPS remained rounded and not fully extended. Fig. 7 uses image analysis (ImageJ, National Institute of Health) of Coomassie-blue stained cells to quantify this visual assessment of hFOB morphology on PTQ and STQ and TCPS. In our hands, % coverage and occupied area were the two most sensitive parameters that seemed to correlate with SEM.

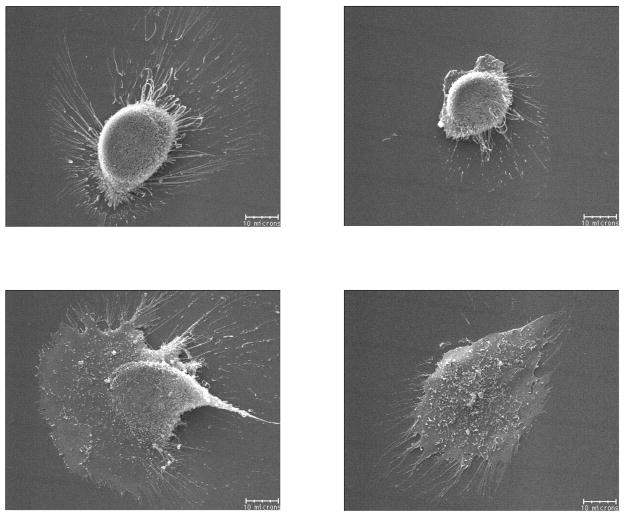

Figure 6.

Variation in hFOB shape on plasma-treated glass (PTG) after 4 hours culture as assessed by SEM showing widely-varying morphological response to apparently cytotoxic SiOx glass. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Figure 7.

Dimensional analysis by image analysis (Image J, NIH) of Coomassie-blue-stained hFOB cultured on hydrophilic surfaces (PTQ = plasma-treated quartz, TCPS = tissue-culture grade polystyrene) and hydrophobic surfaces (STQ = silane-treated quartz) for 24 hours. Statistical significance indicated by * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01) and *** (p < 0.001).

Cells on STQ were the most extended and longitudinally oriented of the group, and retained a spindle-like shape up to 48 hours. Within 48 hours, cell-rounding associated with cell division was observed on all surfaces except on STQ, indicating delayed cell proliferation on STQ consistent with the reduced hFOB doubling time on hydrophobic surfaces reported by Lim et al. [60]. Morphological differences among cells on the various surfaces all but disappear after 48 hours contact, except perhaps hFOB on STQ that retained a spindle-shaped morphology up to 96 hours. Nevertheless, it is clear that extremes in surface energy (that quite nearly lead to life-to-death differences in short-term viability) were substantially remediated after a relatively short culture period. In this regard, it is interesting to note that evolution of morphology on hydrophobic surfaces is slower, but otherwise not remarkably different, than that observed for hFOB on more hydrophilic surfaces - an example of the time-cell-substratum compatibility-superposition-principle mentioned previously. For example, images of hFOB on BGPS at 48 hours or on STQ at 96 hours might well be traded with that of hFOB on TCPS for 24 hours without significantly changing perception of trends.

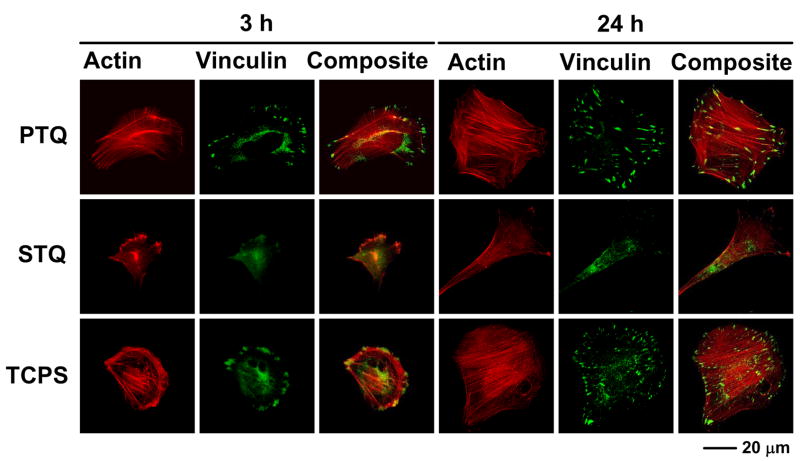

Fig. 8 expands on the work of Lim et al. [61] discussed above using actin and vinculin immunostaining to visualize evolution of cytoskeleton and focal adhesions of hFOB on TCPS, PTQ and STQ by comparing 3 and 24 hour culture intervals. hFOB on PTQ and TCPS displayed actin bundles at 3 hours, whereas actin was much more diffuse in hFOB on STQ. This is quite consistent with the gross morphology observed using SEM (Fig. 5) from which it appeared that hFOB on STQ was attached only at a single point. Vinculin plaques were also distinct at the leading edge of hFOB on PTQ and TCPS, which was not at all the case of STQ. At 24 hours of cell culture, differences among surfaces were even more evident. hFOB on PTQ and TCPS displayed a well-spread and interconnected morphology with well-developed actin stress fibers and vinculin plaques whereas cells on STQ became more spindle-like shape with less-developed actin and vinculin structures. Perhaps the most pronounced effect was co-localization of actin fiber ends and vinculin adhesion structures on TCPS and PTQ that were conspicuously absent in hFOB culture on STQ. In one sense, these results are not surprising because it is well known that cell adhesion and spreading is accomplished by significant changes in cytoskeleton and maturation of adhesion plaques. However, there are relatively few studies that compare gross morphology to cytoskeletal changes over time on substrata with varying surface energy. In fact, reports by Lim et al. are to our knowledge the only comprehensive studies for hFOB in the literature at this writing.

Figure 8.

Actin, vinculin, and composite immunofluorescent images (400X) of hFOB cultured for 3 and 24 hours on hydrophilic substratum (PTQ = plasma-treated quartz, TCPS = tissue-culture grade polystyrene) and hydrophobic surfaces (STQ = silane-treated quartz).

3.3 Integrin and Extracellular Matrix Protein Expression by hFOB on Different Surfaces

Lim et al. [61] compared integrin (α2, α3, α4, α5, αv, β1, β3, and vinculin) protein expression by hFOB cultured on hydrophilic (PTQ/STQ) and hydrophobic (PTG/STG) surfaces (hydrophilic/hydrophobic contrast) for 3 and 6 days. Steady-state levels of osteopontin (OP) and type I collagen (Col I) mRNA were also quantified, providing a sense of ECM protein production. In brief summary, Lim found that hFOB cultured on hydrophobic surfaces expressed significantly lower levels of αv and β3 subunits than on hydrophilic surfaces and that this difference decreased with time in culture. These results are generally consistent with expectations outlined in the previous section, including the proposed time-cell-substratum compatibility-superposition-principle.

To amplify on these trends relative to TCPS as reference surface, Lim’s quantitative data have been normalized to TCPS and reported in Table 1 in the form of a simple +/−/0 rating emphasizing significant trends ((+) = higher than TCPS, (−) = lower than TCPS, (0) = not different than TCPS). Inspection of Table 1 reveals that the most significant differences from hFOB behavior on TCPS occurred by day 3 (p < 0.01) at which time integrin αv expression on STG and STQ was significantly lower and OP mRNA levels on STQ were significantly higher. By day 6, however, integrin αv and OP expression was only slightly different on STQ (p < 0.05) and were not different on STG. β3 was slightly different on STQ than TCPS on both day 3 and 6 at the p < 0.05 level. Vinculin was down-regulated at STQ on day 3 but recovered by day 6. The other integrin subunits (α2, α3, α4, α5, β1) and Col I were not significantly different on glass or quartz relative to TCPS. Integrin and ECM protein expression data correlated with SEM and other morphological analyses presented in the preceding section, confirming that hFOB had substantially, but not fully, recovered from poorly-cytocompatible hydrophobic surface characteristics within 6 days. In particular, we note that a significant down-regulation of αv integrin (which was uncorrelated with β3) and up-regulation of osteopontin correlated with retention of spindle-shaped cell morphology on hydrophobic surfaces as compared to on hydrophilic counterparts.

Table 1.

Integrin, vinculin, osteopontin, and type I collagen expression in hFOB on different glass and quartz surfaces (relative to TCPS)

| PTG | PTQ | STG | STQ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | 3 days | 6 days | 3 days | 6 days | 3 days | 6 days | 3 days | 6 days |

| α2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| α3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| α4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| α5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| αv | − (*) | 0 | 0 | 0 | −− (**) | 0 | −− (**) | − (*) |

| β1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| β3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − (*) | 0 | 0 | − (*) | − (*) |

| Vin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − (*) | 0 |

| OP | − (*) | 0 | 0 | + (*) | 0 | 0 | ++ (**) | + (*) |

| Col I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Notes: Vin = vinculin; OP = osteopontin; Col I = type I collagen; (0) = not significantly different than TCPS; (−) = significantly lower than TCPS; (+) = significantly higher than TCPS; (−−) = much lower than TCPS; (++) = much higher than TCPS; 0/−, 0/+ = modestly lower or higher.

: p < 0.05;

: p < 0.01, respectively. Integrin and Vin was measured by immunoblotting. OP and Col I measured by RT PCR.

Stepping back from these details momentarily (which are already highly simplified relative to Lim’s quantitative analysis), Table 1 suggests that hFOB discrimination between hydrophobic (STG and STQ) and hydrophilic surfaces (PTG and PTQ) was substantially over within 3 days if TCPS is used as the standard of reference. Nearly all of the entries are null or only slightly different in a statistical sense. By day 3, and certainly by day 6, hFOB on both hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces were confluent with no difference in collagen I synthesis among surfaces. Based on the speculation of section 2.4, it is reasonable to suggest that analysis at earlier culture intervals would be required to sense differences in cell-substratum compatibility hFOB experienced on the surfaces, at least for the factors listed in Table 1. In other words, effects of the life-and-death struggle to populate poorly-compatible hydrophobic surfaces was all but erased within 3 days of cell-surface contact during which time hFOB substantially remodeled STG and STQ surfaces.

3.4 Long-term Viability of hFOB in Culture

The primary focus of this review has been the phenotypic progression of hFOB on different substrata over relatively short culture intervals. However, growth of isolated osteoblasts into a mature osteogenic-cell monolayer that significantly mineralizes the surrounding matrix is a slow process, at least for hFOB that generally requires a week or more of continuous culture to accrue significant production of mineral nodules. Also, for the purpose of complete cell-substratum compatibility testing of orthopedic biomaterials in vitro, it may be very desirable to culture osteoblasts in contact with candidate materials for extended periods measured in weeks or months, not days. Thus, it is of interest to end this review with a brief examination of the viability of hFOB in long-term culture.

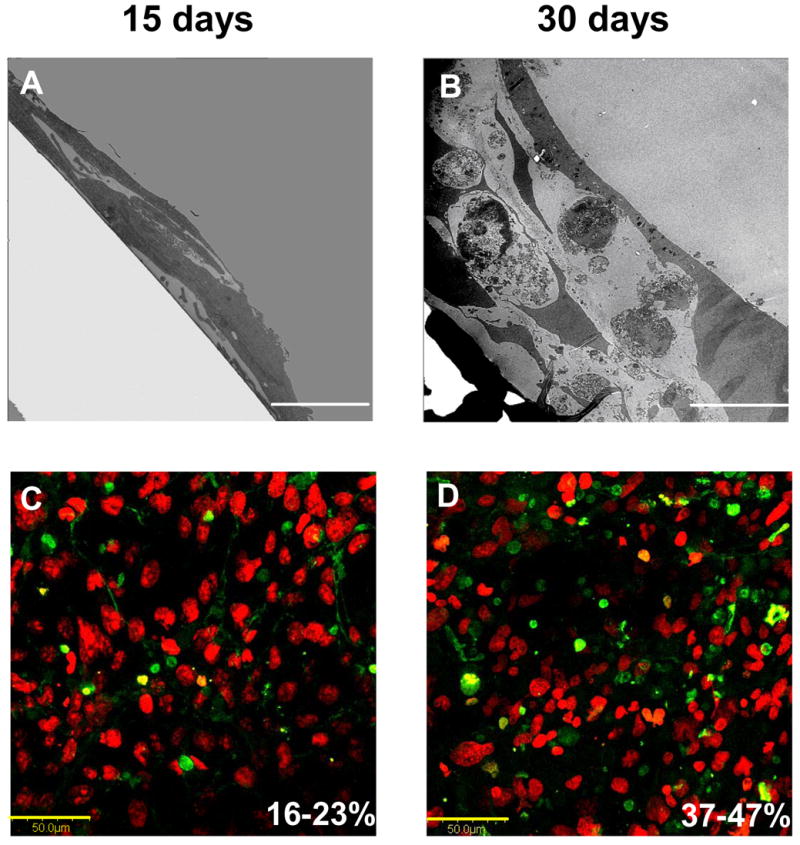

Dhurjati et al. recently compared hFOB culture in TCPS for up to 30 days to that obtained in a specialized bioreactor [112]. TCPS cultures were maintained with medium exchanges every 2 days but without subculture. The bioreactor design was based on the ‘simultaneous-growth-and-dialysis’ method pioneered by Rose in the early 1960’s [113, 114] and avoided both subculture and periodic media exchanges, so that the pericellular environment was extremely stable within the bioreactor. Fig. 9 quantifies cell attachment, proliferation, and post-confluent population expansion phases (inset expands time axis and expresses % inoculum on a linear axis; compare to Fig. 2). Table 2 compares 15 and 30 day culture characteristics, including alizarin red staining that suggests cultures were mineralizing (although no mineral nodules were evident by SEM and von Kossa staining was negative). Somewhat surprisingly, TCPS cultures remained robust in appearance until about 30 days when cell rounding and debris formation indicated viability issues. TEM and apoptosis assays (see Fig. 10) confirmed loss of culture integrity. Evidently hFOB cannot be maintained in standard TCPS without subculture for longer than about 30 days. By contrast, Dhurjati reports indefinite culture intervals longer than 4 months (10 months in unpublished work), suggesting that long-term maintenance of an osteogenic tissue is possible in a relatively-simple bioreactor setup.

Figure 9.

Short- and long-term growth dynamics of hFOB on tissue-culture grade polystyrene (TCPS) spanning 30 days in continuous culture without subculture. Inset expands short-term attachment rates using a linear ordinate.

Table 2.

Long-term hFOB Cell growth in Tissue-Culture Grade Polystyrene (TCPS)

| Culture time | 15 days | 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaline Phosphatase activity (nmol/mg pr./min) | 4.39 ± 0.26 | 4.47 ± 0.38 |

| Alizarin red (μmol) | 2.89 ± 0.04 | 3.03 ± 0.02 |

Figure 10.

Variation in long-term hFOB morphology on tissue-culture grade polystyrene (TCPS) assessed by cross-sectional TEM (Panels A: Scale bar = 5 μm; B: Scale bar = 10 μm) showing formation of multiple cell layers. Note that apoptotic bodies were clearly evident after 30 days of culture. Apoptotic cells (green) among normal cells (red, Sytox Orange) visualized using confocal microscopy confirms an increase in apoptosis with culture age (Panels C, D: Scale bar = 50 μm). Percent apoptotic bodies noted in lower right of Panels C,D were estimated by image analysis (see ref. [112] for experimental details).

4. Concluding Remarks

Time-dependent phenotypic response of a model osteoblast (hFOB 1.19, ATCC, CRL-11372) to substrata with varying surface chemistry and topography has been reviewed in the context of cell adhesion theory. The general sequence of events – contact, attachment, spreading, and proliferation – appears to be very similar among all surfaces, independent of surface chemistry. However, this sequence of events is delayed and attenuated on poorly-cytocompatible hydrophobic substrata. Poorly-cytocompatible surfaces exhibit characteristically-low attachment efficiency and long induction periods during which cells are apparently engaged in a life-or-death struggle to improve the pericellular environment by excretion of matrix proteins. A kind of time-cell-substratum compatibility-superposition-principle seems to be in play here in which similar bioadhesive outcomes can be ultimately achieved on all surfaces, but the time required to arrive at this outcome increases with decreasing cell-substratum compatibility.

Modern genomic and proteomic tools offer unprecedented opportunity to directly measure changes in the cellular machinery that lead to the observed cell response to different materials. This information is key to bridging the gap between a purely physical-chemical and a purely-biological understanding of cell adhesion in a way that promises to yield structure-property relationships so critical to the prospective engineering of biomaterials. For this purpose, timing is critical. Genomic/proteomic tools must be used during a stage of cell adhesion when cell-surface interactions most profoundly affect cell physiology. Applied too early, little information will be gained because cells have not yet sensed the interfacial environment in which they find themselves immersed. Applied too late, little information will be gained because cells have had time to remodel the pericellular environment. We intuit from the information reviewed in this paper that the most sensitive stage of cell adhesion for application of genomic/proteomic tools is within spreading and proliferation phases. Thus, the implication for cell adhesion research is that genomic and proteomic tools should be applied early in the adhesion/spreading process before cells have an opportunity to significantly remodel the cell-substratum interface, effectively erasing cause-and-effect relationships between cell-substratum compatibility and substratum properties.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. This work was also supported by The Pennsylvania State Tobacco Settlement Formula Fund, National Institutes of Health Grant AG13087-10, U. S. Army Medical Research and Materials Command Breast Cancer Research Program WX81XWH-06-10432, and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation BCTR 0601944. Authors appreciate additional support from the Huck Institutes of Life Sciences, Materials Research Institute, and Departments of Bioengineering and Materials Science and Engineering of the Pennsylvania State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Citations

- 1.Baxter LC, Frauchiger V, Textor M, Gwynn Ia, Richards RG. Fibroblast and osteoblast adhesion and morphology on calcium phosphate surfaces. European Cells and Materials. 2002;4:1–17. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v004a01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grinnell F. Cellular Adhesiveness and Extracellular Substrata. In: Bourne GH, Danielli JF, Jeon KW, editors. International Review of Cytology. New York: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 67–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altankov G, Grinnell F, Groth T. Studies on the Biocompatibility of Materials: Fibroblast Reorganization of Substratum-bound Fibronectin on Surfaces Varying in Wettability. J Biomed Mat Res. 1996;30:385–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199603)30:3<385::AID-JBM13>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pethica BA. The physical chemistry of cell adhesion. Experimental Cell Research Supplement. 1961;(8):123–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutter PR. The Physical Chemistry of the Adhesion of Bacteria and Other Cells. In: Curtis ASG, Pitts JD, editors. Cell Adhesion and Motility. London: Cambridge University Press; 1980. pp. 103–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bongrand P, Capo C, Depieds R. Physics of Cell Adhesion. Progress in Surface Science. 1982;12:217–235. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pethica BA. Microbial and Cell Adhesion. In: Berkeley RCW, Lynch JM, Melling J, Rutter PR, Vincent B, editors. Microbial Adhesion to Surfaces. London: Ellis Horwood Limited; 1983. pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell G, Dembo M, Bongrand P. Cell Adhesion: Competition Between Nonspecific Repulsion and Specific Bonding. Biophys J. 1984;45:1051–64. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barngrover D. Substrata for Anchorage-Dependent Cells. In: Thilly WG, editor. Mammalian Cell Technology. Boston: Butterworths; 1986. pp. 131–49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horbett TA, Klumb LA. Cell Culturing: Surface Aspects and Considerations. In: Brash JL, Wojciechowski PW, editors. Interfacial Phenomena and Bioproducts. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996. pp. 351–445. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammer DA, Tirrell M. Biological Adhesion at Interfaces. Annual Review Material Science. 1996;26:651–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adao MH, Fernandes AC, Saramago B, Cazabat AM. Influence of Preparation Method on the Surface Topography and Wetting Properties of Polystyrene Films. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 1998;132:181–92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillow AK, Tirrell M. Targeted cellular adhesion at biomaterial interfaces. Current Opinion in Solid State & Materials Science. 1998;3:252–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donahue HJ, Siedlecki CA, Vogler E. Osteoblastic and Osteocytic Biology and Bone Tissue Engineering. In: Hollinger JO, Einhorn TA, Doll B, Sfeir C, editors. Bone Tissue Engineering. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2004. pp. 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hench LL. Biomaterials: a forecast for the future. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1419–23. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delmas PD, Anderson M. Launch of the Bone and Joint Decade: 2000–2010. Osteoporosis Int. 2000;11:95–7. doi: 10.1007/PL00004181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Praemer A, Rice DF. Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States. American Acad of Orthopeadic Surgeons. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piehler HP. The future of medicine: biomaterials. MRS Bulletin. 2000 August;:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiberstis P, Smith O, Norman C. Bone Health in The Balance. Science. 2000 September 1;289(5484):1497. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodan GA, Martin TJ. Therapeutic Approaches to Bone Diseases. Science. 2000 September 1;289(5484):1508–14. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Service RF. Tissue Engineers Build New Bone. Science. 2000 September 1;289(5484):1498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keeting PE, Scott RE, Colvard DS, Anderson MA, Outsler MJ, Spelsberg TC, et al. Development and characterization of a rapidly proliferating, well-differentiated cell line derived from normal adult human osteoblast-like cells transfected with SV40 large T antigen. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1992;7(2):127–36. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clover J, Gowen M. Are MG63 and HOS TE85 human osteosarcoma cell lines representative models of the osteoblastic phenotype? Bone. 1994;15:585–91. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris SA, Enger RJ, Riggs BL, spelsberg TC. Development and Characterization of a Conditionally Immortalized Human Fetal Osteoblastic Cell Line. J Bone and Mineral Res. 1995;10:178–86. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subramaniam M, Jalal SM, Rickard DJ, Harris SA, Bolander ME, Spelsberg TC. Further characterization of human fetal osteoblastic hFOB 1.19 and hFOB/ERa cells: bone formation in vivo and karyotype analysis using multicolor fluorescent in situ hybridization. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2002;87:9–15. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mudd S, Mudd EBH. Certain Interfacial Tension Relations and the Behavior of Bacteria in Films. J Experimental Medicine. 1924;40:647–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.40.5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mudd S, Mudd E. The Penetration of Bacteria through Capillary Spaces: IV. A Kinetic Mechanism in Interfaces. J Expt Medicine. 1924;40:633–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.40.5.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerson DF. Interfacial Free Energies of Cells and Polymers in Aqueous Media. In: Mittal KL, editor. Int Symp on Physicochemical Aspects of Polymer Surfaces; 1981. New York: Plenum Press; 1981. pp. 229–40. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torney DC, Dembo M, Bell GI. Thermodynamics of Cell Adhesion II. Freely Mobile Repellers. Biophys J. 1986;49:501–7. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Facchini PJ, Neumann AW, DiCosmo F. Thermodynamic Aspects of Cell Adhesion to Polymer Surfaces. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1988;29:346–55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogler EA. Thermodynamics of Short-Term Cell Adhesion in Vitro. Biophysical J. 1988;53:759–69. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83156-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norde W, Lyklema J. Protein Adsorption and Bacterial Adhesion to Solid Surfaces: A Colloid-Chemical Approach. Colloids and Surfaces. 1989;38:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogler EA. A Thermodynamic Model of Short-Term Cell Adhesion In Vitro. Colloids and Surfaces. 1989;42:233–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rappaport C. Some aspects of the growth of mammalian cells on glass surfaces. In: Hair ML, editor. The chemistry of biosurfaces. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1972. pp. 449–87. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuda T, Litt MH. Modification and Characterization of Polystyrene Surfaces Used in Cell Culture. J Polymer Sci. 1974;12:489–97. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klemperer HG, Knox P. Attachment and Growth of BHK Cells and Liver Cells on Polystyrene: Effect of Surface Groups Introduced by Treatment With Chromic Acid. Lab Pract. 1977;26:179–80. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benedict RW, Williams MC. Bonding Erythrocytes to Plastic Substrates by Glow-Discharge Activation. Biomat, Med, Art Org. 1979;7(4):477–93. doi: 10.3109/10731197909118963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogler EA. Interfacial Chemistry in Biomaterials Science. In: Berg J, editor. Wettability. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. pp. 184–250. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curtis ASG. Adhesion of Cells to Polystyrene Surfaces. J Cell Bio. 1983;97:1500–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.5.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramsey WS, Hertl W, Nowlan ED, Binkowski NJ. Surface Treatments and Cell Attachment. In Vitro. 1984;20(10):802–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02618296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis A, Wilkinson C. Ambiguities in the Evidence About Cell Adhesion Problems with Activation Events and with the Structure of the Cell-contact. Studia Biophysica. 1988;127(1–3):75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owens NF, Gingell D, Trommler A. Cell Adhesion to Hydroxyl Groups of a Monolayer Film. J Cell Sci. 1988;91:269–79. doi: 10.1242/jcs.91.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Margel S, Vogler EA, Firment L, Watt T, Haynie S, Sogah DY. Peptide, Protein, and Cellular Interactions with Self-Assembled Monolayer Model Surfaces. J Biomed Mat Res. 1993;27:1463–76. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820271202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogler EA. On the Biomedical Relevance of Surface Spectroscopy. J Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomenon. 1996;81:237–47. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogler EA, Bussian RW. Short-Term Cell-Attachment Rates: A Surface Sensitive Test of Cell-Substrate Compatibility. J Biomed Mat Res. 1987;21:1197–211. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820211004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogler EA. Structure and Reactivity of Water at Biomaterial Surfaces. Adv Colloid and Interface Sci. 1998;74(1–3):69–117. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(97)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogler EA. Water and the Acute Biological Response to Surfaces. J Biomat Sci Polym Edn. 1999;10(10):1015–45. doi: 10.1163/156856299x00667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vogler EA. How Water Wets Biomaterials. In: Morra M, editor. Water in Biomaterials Surface Science. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2001. pp. 269–90. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duguid JP. Fimbriae and adhesive properties in Klebsiella strains. Journal of General Microbiology. 1959;21:271–86. doi: 10.1099/00221287-21-1-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duguid JP, Old DC. Adhesive properties of Enterobacteriaceae. In: Beachey EH, editor. Bacterial adherence. London: Chapman and Hall; 1980. pp. 185–217. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beachey EH. Bacterial adherence: Adhesin-receptor interactions mediating the attachment of bacteria to mucosal surfaces. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1981;143(3):325–45. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andrade JD. Principles of Protein Adsorption. In: Andrade JD, editor. Surface and Interfacial Aspects of Biomedical Polymers: Protein Adsorption. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramsden JJ. Puzzles and Paradoxes in Protein Adsorption. Chemical Society Reviews. 1995;24:73–8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss L. The adhesion of cells. In: Bourne GH, Danielli JF, editors. International Review of Cytology. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1960. pp. 187–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grinnell F. The serum dependence of baby hamster kidney cell attachment to a substratum. Experimental Cell Research. 1976;97:265–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90616-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamada KM, Kennedy DW. Dualistic Nature of Adhesive Protein Function: Fibronectin and its Biologically Active Peptide Fragments Can Autoinhibit Fibronectin Function. Cell Biology. 1984;99:29–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andrade JD, Hlady V. Protein Adsorption and Materials Biocompatibility: A Tutorial Review and Suggested Mechanisms. Adv Polym Sci. 1986;79:3–63. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JH, Khang G, Lee JW, Lee HB. Platelet Adhesion onto Chargeable Functional Group Gradient Surfaces. J Biomed Mat Res. 1998;40:180–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199805)40:2<180::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teare DOH, Emmison N, Ton-That C, Bradley RH. Effects of Serum on the Kinetics of CHO Attachment ot Ultravioliet-Ozone Modified Polystyrene Surfaces. J Colloid and Interface Sci. 2001;234:84–9. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim JY, Liu X, Vogler EA, Donahue HJ. Systematic variation in osteoblast adhesion and phenotype with substratum surface characteristics. J Biomed Mat Res. 2004;68A:504–12. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim JY, Taylor AF, Li Z, Vogler EA, Donahue HJ. Integrin expression and osteopontin regulation in human fetal osteoblastic cells mediated by substratum surface characteristics. Tissue Engineering. 2005;11(1–2):19–29. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marmur A, Gill WN, Ruckenstein E. Kinetics of Cell Deposition Under the Action of an External Field. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 1976;38:713–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02458645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruckenstein E, Marmur A, Gill WN. Coverage Dependent Rate of Cell Deposition. J Theor Biol. 1976;58:439–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(76)80130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruckenstein E, Marmur A, Radower SR. Sedimentation and Adhesion of Platelets onto a Horizontal Glass Surface. Thrombos Haemostas. 1976;36:334–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srinivasan R, Ruckenstein E. Kinetically Caused Saturation in the Deposition of Particles or Cells. J Colloid and Interface Sci. 1981;79(2):390–8. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruckenstein E, Srinivasan R. Comments on Cell Adhesion to Biomaterial Surfaces: The origin of Saturation in Platelet Deposition - Is it Kinetic or Thermodynamic. J Biomed Mat Res. 1982;16:169–72. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820160209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith U, Ryan JW. Electron microscopy of endothelial cells collected on cellulose acetate paper. Tissue & Cell. 1973;5(2):333–6. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(73)80027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manduca P, Sanguineti C, Pistone M, Boccignone E, Sanguineti F, Santolini F, et al. Differential expression of alkaline phosphatase in clones of human osteoblast-like cells. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1993;8(3):219–300. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morais S, Dias N, Sousa JP, Fernandes MH, Carvalho GS. In vitro osteoblastic differentiation of human bone marrow cells in the presence of metal ions. J Biomed Mat Res. 1999;44:176–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199902)44:2<176::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shah AK, Sinha RK, Hickok NJ, Tuan RS. High-resolution morphometric analysis of human osteoblastic cell adhesion on clinically relevant orthopedic alloys. Bone. 1999;24:499–506. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salih V, Georgiou G, Knowles JC, Olsen I. Glass reinforced hydroxyapatite for hard tissue surgery-Part II: in vitro evaluation of bone cell growth and function. Biomaterials. 2001;22:2817–24. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cerroni L, Filocamo R, Fabbri M, Piconi C, Caropreso S, Condo SG. Growth of osteoblast-like cells on porous hydroxyapatite ceramics: an in vitro study. Biomolecular Engineering. 2002;19:119–24. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0344(02)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dettin M, Conconi MT, Gambaretto R, Pasquato A, Folin M, Bello CD, et al. Novel osteoblast-adhesive peptides for dental/orthopedic biomaterials. J Biomed Mat Res. 2002;60:466–71. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hendrich C, Noth U, Stahl U, Merklein F, Rader CP, Schiitze N, et al. Testing of skeletal implant surfaces with human fetal osteoblasts. Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research. 2002;394:278–89. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200201000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharefkin JB, Lather C, Smith M, Rich NM. Endothelial cell labeling with indium-111-oxine as a marker of cell attachment to bioprosthetic surfaces. J Biomed Mat Res. 1983;17:345–57. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820170211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dee KC, Andersen TT, Bizios R. Design and function of novel osteoblast-adhesive peptide for chemical modification of biomaterials. J Biomed Mat Res. 1998;40:371–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980605)40:3<371::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dalby MJ, Kayser MV, Bonfield W, Silvio LD. Initial attachment of osteoblasts to an optimised HAPEX topography. Biomaterials. 2002;23:681–90. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salgado AJ, Figueiredo JE, Coutinho OP, Reis RL. Biological response to pre-mineralized starch based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2005;16:267–75. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-6689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ahmad M, Gawronski D, Blum J, Goldberg J, Gronowicz G. Differential response of human osteoblast-like cells to commercially pure (cp) titanium grades 1 and 4. J Biomed Mat Res. 1999;46:121–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199907)46:1<121::aid-jbm14>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wachem PBv, Beugeling T, Feijen J, Bantjes A, Detmers JP, Aken WGv. Interaction of Cultured Human Endothelial Cells with Polymeric Surfaces of Different Wettability. Biomaterials. 1985;6:403–8. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(85)90101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grinnell F. Concanavalin a increases the strength of baby hamster kidney cell attachment to substratum. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1973;58:602–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.58.3.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharefkin JB, Watkins MT. Methods for the measurement of cell attachment to bioprosthetic surfaces. In: Williams DF, editor. Techniques of Biocompatibility Testing. Boca Raton, FL; CRC Press, Inc: 1986. pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Webster TJ, Ergun C, Doremus RH, Siegel RW, Bizios R. Specific proteins mediate enhanced osteoblast adhesion on nanophase ceramics. J Biomed Mat Res. 2000;51:475–83. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<475::aid-jbm23>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hunter A, Archer CW, Walker PS, Blunn GW. Attachment and proliferation of osteoblasts and fibroblasts on biomaterials for orthopaedic use. Biomaterials. 1995;16:287–95. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)93256-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ruan J-M, Grant HM. Biocompatibility evaluation in vitro. Part I: morphology expression and proliferation of human and rat osteoblasts on the biomaterials. Journal of Central South University Technology. 2001;8(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Howlett CR, Evans MDM, Walsh WR, Johnson G, Steele JG. Mechanism of initial attachment of cells derived from human bone to commonly used prosthetic materials during cell culture. Biomaterials. 1994;15(3):213–22. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Krause A, Cowles EA, Gronowicz G. Integrin-mediated signaling in osteoblasts on titanium implant materials. J Biomed Mat Res. 2000;52:738–47. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20001215)52:4<738::aid-jbm19>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim H-K, Jang J-W. Surface modification of implant materials and its effect on attachment and proliferation of bone cells. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2004;15:825–30. doi: 10.1023/b:jmsm.0000032824.62866.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rea SM, Brooks RA, Schneider A, Best SM, Bonfield W. Osteoblast-like cell response to bioactive composites - Surface-topography and composition effects. J Biomed Mat Res. 2004;70B:250–61. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.van der Valk P, van Pelt AWJ, Busscher HJ, de Jong HP, Wildevuur CRH, Arends J. Interaction of fibroblasts and polymer surfaces: relationship between surface free energy and fibroblast spreading. J Biomed Mat Res. 1983;17:807–17. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820170508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lydon MJ, Minett TW, Tighe BJ. Cellular Interactions with Synthetic Polymer Surfaces in Culture. Biomaterials. 1985;396–402:396–402. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(85)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Takayama H, Tanigawa T, Takagi A, Hatada K. Polymers of Methacrylate Available for Obtaining Varieties of Cell-substratum Adhesivity. Biomedical Research. 1986;7(1):11–8. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gerson DF. Cell surface energy, contact angles and phase partition I. Lymphocytic cell lines in biphasic aqueous mixtures. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1980;602:269–80. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(80)90310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Corry WD, Defendi V. Centrifugal assessment of cell adhesion. Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods. 1981;4:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(81)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hertl W, Ramsey WS, Nowlan ED. Assessment of cell-substrate adhesion by a centrifugal method. In Vitro. 1984;20(10):796–801. doi: 10.1007/BF02618295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crouch CF, Fowler HW, Spier RE. The adhesion of animal cells to surfaces: the measurement of critical surface shear stress permitting attachment or causing detachment. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. 1985;35B:273–81. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lampin M, Warocquier-Clerout R, Legris C, Degrange M, Sigot-Luizard MF. Correlation between substratum roughness and wettability, cell adhesion and cell migration. J Biomed Mat Res. 1997;36:99–108. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199707)36:1<99::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Usson Y, Guignandon A, Laroche N, Lafage-Proust M-H, Vico L. Quantitation of cell-matrix adhesion using confocal image analysis of focal contact associated proteins and interference reflection microscopy. Cytometry. 1997;28:298–304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970801)28:4<298::aid-cyto4>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Kooten TG, Klein CL, Wagner M, Kirkpatrick CJ. Focal adhesion and assessment of cytotoxicity. J Biomed Mat Res. 1999;46:33–43. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199907)46:1<33::aid-jbm4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zamir E, Katz B-Z, Aota S-i, Yamada KM, Geiger B, Kam Z. Molecular diversity of cell-matrix adhesions. Journal of Cell Science. 1999;112:1655–69. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.11.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]