Abstract

Chemically inducible gene switches that regulate expression of endogenous genes have multiple applications for basic gene expression research and gene therapy. Single-chain zinc-finger transcription factors that utilize either estrogen receptor homodimers or retinoid X receptor-α/ecdysone receptor heterodimers are shown here to be effective regulators of ICAM-1 and erbB-2 transcription. Using activator (VP64) and repressor (KRAB) domains to impart regulatory directionality, ICAM-1 was activated by 6.1-fold and repressed by 83% with the estrogen receptor inducible transcription factors. ErbB-2 was activated by up to 3-fold and repressed by 84% with the retinoid X receptor-α/ecdysone receptor inducible transcription factors. The dynamic range of these proteins was similar to the constitutive system and showed negligible basal regulation when ligand was not present. We have also demonstrated that the regulation imposed by these inducible transcription factors is dose dependent, sustainable for at least 11 days, and reversible upon cessation of drug treatment. Importantly, these proteins can be used in conjunction with each other with no detectable overlap of activity enabling concurrent and temporal regulation of multiple genes within the same cell. Thus, the chemically inducible transcription factors presented here are valuable tools for spatio-temporal control of gene expression that should prove valuable for research and gene therapy applications.

Artificial zinc finger transcription factors (TFZFs) have been used to discover, regulate, and study genes in vitro and in vivo (1,2). Zinc finger (ZF) domains are modular and can be combined to create new proteins of desired DNA-binding specificity. By taking comprehensive approaches and using phage display selection strategies, we and others have successfully prepared zinc finger domains that target virtually all DNA triplets (3-7). Typically, designer TFZFs are composed of up to six zinc finger domains; a six-finger ZF binds to 18 base pairs of DNA; this allows recognition of a unique sequence within the human genome (8).

When combined with repressor or activator domains, ZF proteins can be used to regulate transcription of genes. For instance, to regulate the erbB-2/HER-2 gene, the E2C polydactyl ZF was designed to bind to a specific sequence within the promoter. This ZF domain has been fused to the herpes simplex VP16 transcriptional activation domain (VP64), transcriptional repression domains like the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) (9), mad mSIN3 interaction domain (SID) (10), and a nuclear localization signal (11,12). As an alternative to individual rational design of zinc finger proteins for each target sequence, high-throughput and genome-wide approaches have been developed to directly isolate functional TFZFs from large libraries of randomly shuffled ZF domains (13,14). Using this type of rapid selection in mammalian cells, a regulator of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), CD54−31-TFZF, was isolated. The TFZF binds with high affinity and specificity to a unique site of the ICAM-1 promoter (15). Most TFZFs have been constructed for constitutive regulation of natural promoters driving reporter genes (11,16,17). TFZFs have been expressed from constitutive promoters transiently, retrovirally, or by generating integrated stable cell lines (18-21) and have also been expressed in vivo (22).

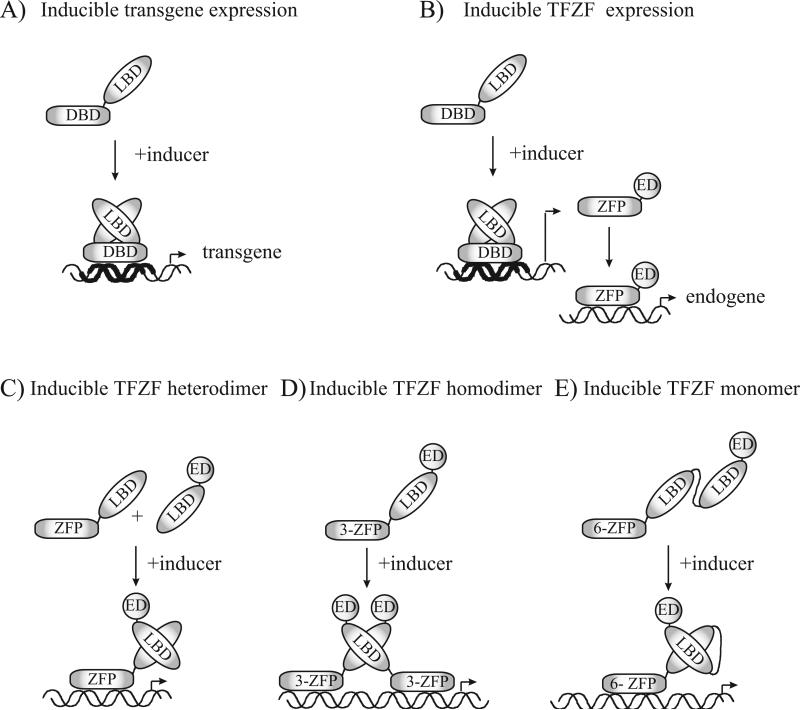

To effectively study gene function and develop gene therapies, tightly controlled and highly inducible regulation of the target gene is desirable through direct control of the TFZF with a cell-penetrating drug. Inducible transcription regulatory systems, or gene switches, are chimeric transregulators typically consisting of a DNA binding domain (DBD) fused to a transcription effector domain (ED) and a ligand binding domain (LBD). These chimeric transregulators dimerize upon drug addition and eventually undergo conformational changes that result in control of a target promoter (Fig. 1). As these systems have been based on naturally existing DNA binding domains (DBD) of definite DNA sequence specificity, use has been restricted to regulation of exogenously delivered transgenes or reporter genes (23) (Fig. 1A). Use of zinc finger-based domains as the DBD of the chimeric transregulator allows targeting of virtually any sequence in a promoter, minimizing endogenous cross-reactivity and potentially allowing regulation of any desired chromosomal promoter. The first zinc finger-based gene switches were under the control of a tetracycline- or ecdysone-inducible response element. However, this required co-expression of the LBD transregulators and imposed the use of pre-engineered host cells or the generation of stable cell lines for the regulation of endogenous genes (18,19,24) or transgenes (6,25) (Fig. 1B). An advance came with the development of systems that fused split TFZFs with LBDs or dimerizer domains. This is typically achieved by the drug-dependent reconstitution of functional transregulatory heterodimers that connect the DBD to the ED (12,26) (Fig. 1C). These systems did not require use of stable cell lines, but did, however, require the delivery and expression of the two separate components, ideally at equimolar concentrations. We previously reported inducible gene switches based on nuclear hormone receptor LBDs and E2C-TFZFs to demonstrate the up-regulation of the ErbB2 promoter by ligand-dependent transcription regulators in transient reporter luciferase assays (12). Homodimeric single-chain gene switches provide the advantage of requiring delivering of only one expression cassette, but require two identical target sequences at a certain distance and orientation to each other in the promoter (Fig. 1D). More sophisticated versions are monomeric proteins composed of a TFZF controlled by two linker-associated estrogen receptor LBDs (scER) or by the retinoid X receptor-α linked to the ecdysone receptor (RE) (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Evolution of inducible transcription regulatory systems, also called gene switches. A) Directly controlled inducible expression systems require a specific DNA element (indicated by thick DNA helix) located upstream of a transgene of interest and engineered cells lines that stably express a ligand-inducible regulatory protein, such as the tetracycline repressor. B) Engineered TFZFs placed under the regulation of an inducible DNA element offer the opportunity for control of endogenous genes. C) Heterodimeric inducible systems provide drug inducible regulation of the activity of split TFZFs fused to LBDs or dimerizer domains without the use of a stable cell line. D) Homodimeric iTFZFs gene switches, delivered by a single-chain protein, are useful when two contiguous target sites are available. E) Monomeric iTFZFs inducible systems conveniently associate the desired benefits of the other systems, including the inducible regulation of endogenous genes using single-chain 6-fingered iTFZFs gene switches with unique genome specificity and without cell-line restrictions.

In this study, we demonstrate endogenous gene regulation by monocistronically encoded single-chain gene switches that avoid the problems inherent to the co-expression of heterodimers or transgenes and alleviate the specific constraints that homodimers place on the nature of the target site. By combining constitutive retroviral expression in bulk cell populations and single-chain gene switches targeting 18 unique base pairs within DNA promoter sequences of endogenous genes, we demonstrated simultaneous positive and negative regulation of transcription. Regulation was dependent on the dose of hormone analog, was sustainable and reversible, and had a low basal and highly inducible activity. We propose that these inducible TFZFs (iTFZF) will be valuable for use in vivo as spatiotemporal endogenous gene regulation is key in treatment of human diseases such as metastasized cancer.

Experimental Procedures

Human cell lines

A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells and HeLa cervix carcinoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The 293-GagPol packaging cell line was obtained from I. Verma (Salk Institute, San Diego). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) medium supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics.

Construction of retroviral plasmids for the expression of iTFZFs

The expression cassettes of pcDNA E2C monomeric switch constructs, those with C-terminal effector domains used in the transient assays (12), were subcloned into the pMX-IRES-GFP retroviral vector (27) using the following restriction digest and ligation strategy. The single-chain estrogen receptor constructs pcDNA E2C ScER/30-VP64 and -KRAB (30 aa linker) were digested and ligated into pMX E2C-VP64 vector using BamH1-Pac1 restriction enzymes. The single-chain ecdysone/retinoic acid receptor constructs pcDNA E2C-RE-VP64 and KRAB (18 residue linker), and E2C-RLE-VP64 and -KRAB (30 residue linker) were digested with Fse1-Pac1 and assembled in a one step two-way ligation with a BamH1-Fse1 E2C fragment into the pMX E2C-VP64 vector previously digested with BamH1 and Pac1. The ICAM-1 gene switch constructs were created by replacing the E2C by the CD54−31 six finger coding DNA using the Sfi1 restriction enzyme.

Retroviral delivery and inducible iTFZFs assay

Retroviral transductions were performed using 293-GagPol packaging cells and VSV envelope pseudotyping to produce retrovirus as described previously (15) with the following modifications. With constitutive TFZFs, target gene expression was measured 72 hours after the retrovirus was applied to the cells. Unless otherwise stated in the figure legends, the host cells transduced with the inducible iTFZFs were split in two dishes 24 h after transduction, and while one half of the cells was kept uninduced to measure the basal activity of the iTFZFs, the other half was supplemented with 100 nM ponA (Invitrogen) or 5 μM 4-OHT (Sigma) for the induction of the iTFZFs based on the estrogen and retinoid X/ecdysone receptors, respectively. 48 hours later, the cells were harvested for analysis of the target gene expression by FACS or western blotting. Transduction efficiency and iTFZFs expression was verified by flow cytometry with the percentage of cells indicating GFP fluorescence, which is co-expressed on the same bicistronic transcript as the iTFZFs. Using these conditions, the bulk (>80%) of the A431 or HeLa cells were expressing GFP after 3 days transduction, which persisted up to 19 days (not shown). The pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen) was used as mock transduction control for the determination of the basal target gene expression. The addition of drug inducer to the negative control cell sample did not alter the cell-surface expression of the targets (data not shown).

Flow cytometric analysis of inducible target gene regulation

Three days after cell transduction, cell surface expression of the target genes was measured with anti-ICAM-1 (clone HA58, BD PharMingen) and anti-ErbB2 (clone FSP77, gift from Nancy E. Hynes, Friedrich Miescher Institute, Basel (28)) monoclonal antibodies at 5μg/ml and with a PE-labeled donkey anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Jackson Immunochemicals) using a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Comparative analysis of mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) was determined using CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson). MFI was corrected for background by subtraction of the autofluorescence of cells incubated with the secondary antibody only and normalized to the expression value of mock transduced cells.

Western blotting

For measuring protein expression by western blotting, whole cell extracts were prepared with cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X100) containing 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). For each sample, the total protein concentration was determined with a Bradford assay (Biorad). Equal amounts of protein were separated on reducing 4−12% bis-tris polyacrylamide gels with MES SDS buffer and transferred to a Hybond-P PVDF membrane (Amersham) according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). For normalization with a constitutive protein, membranes were treated in blocking buffer (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma) with 5% blocking agent (Amersham), incubated with anti-β-actin (clone AC-15, Sigma), washed in PBST and detected with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. For the detection of the target protein and TFZF, the membranes were stripped in 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 30 minutes at 65°C, washed in PBST, and treated with blocking buffer containing 10μg/ml extravidin and 1μg/ml α-biotin (both Sigma). ICAM-1 was immunostained with a biotinylated anti-ICAM-1 (BAF720, R&D Systems) and TFZF proteins with biotinylated anti-influenza hemagglutinin tag (clone 3F10, Roche), respectively. Membranes were then washed and incubated with streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) in PBST. Alternatively, for the western blots of the dose response experiments, the anti-ICAM-1 primary antibody was detected with a peroxidase coupled donkey anti-sheep secondary antibody (Jackson Immunochemicals). The blots were revealed with the ECL Plus kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Amersham) and exposed to an X-OMAT film (Kodak) or quantified using a Storm 860 phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics) using the blue chemifluorescence scanning mode. The intensity of the bands corresponding to the respective size of the proteins on reducing gel was quantified using the ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Constitutive ICAM-1 and ErbB2 endogenous gene regulation

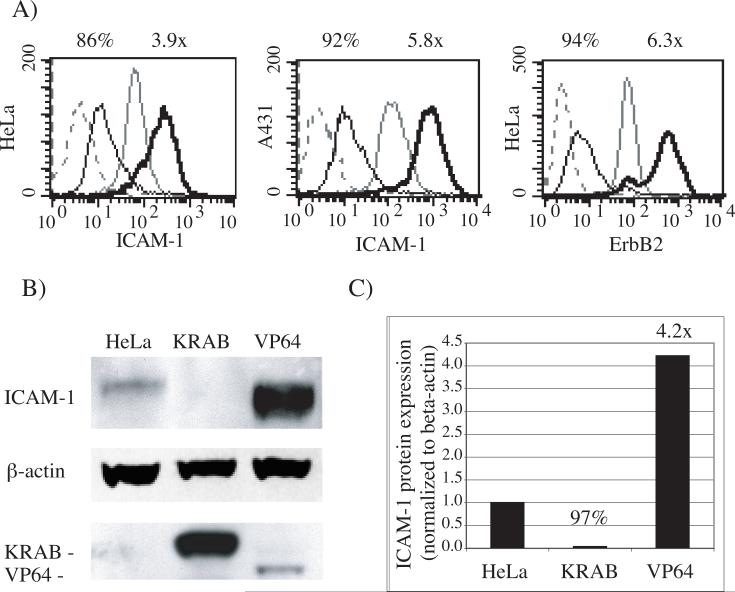

To establish a generic gene switch system for endogenous gene regulation, previously described designer six-zinc finger proteins were used as DBD models. When fused to VP64 activation or KRAB repression domains, CD54−31 and E2C regulate the promoters of the ICAM-1 (15) and ErbB2 (18) genes, respectively, with exquisite specificity. Constitutive expression of the TFZFs from the pMX retroviral vector in HeLa and A431 cells allowed for the almost complete knock-down and a 4−6 fold overexpression of each gene product in the whole-cell populations; results were quantified using specific anti-target antibodies with either flow cytometry or western blotting (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Positive and negative regulation of endogenous genes using constitutively expressed TFZFs. Endogenous protein expression levels were measured in cells that expressed 6-zinc finger proteins that bind to the promoters of ICAM-1 (CD54−31) or ErbB2 (E2C) fused to the KRAB repressor or the VP64 transactivator domains. A) FACS analysis of cell-surface expression of ICAM-1 (in HeLa and A431 cells) and ErbB2 (in HeLa cells). The percentage of repression (black overlay) and fold activation (thick black overlay) using TFZFs compared to mock transduced cells (grey overlay) is calculated from background-subtracted mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) (dashed grey overlay). B) Western analysis of ICAM-1 regulation in HeLa cells. Total protein extracts were separated on denaturing SDS-PAGE gel, blotted to a PVDF membrane, immunostained using specific antibodies and chemiluminescence detection. ICAM-1 expression in mock-transduced cells (Hela) is compared to CD54−31 repressor (KRAB) and activator (VP64) TFZF expressing cells, relative to constitutive protein β-actin) and retroviral TFZF expression. C) Relative quantification of ICAM-1 bands normalized to β-actin levels. Fold activation and percentage repression are indicated on top of overlays and bar graphs.

Inducible regulation of endogenous gene expression by single chain iTFZFs gene switches

Because the control of endogenous gene expression with cell permeable drugs is highly desirable, iTFZFs endogenous gene switches were generated by subcloning the TFZFs fused with single-chain hormone receptor LBDs into the pMX vector. The N-terminal zinc finger DBD and the C-terminal transcriptional effector domain were separated by dimeric hormone binding domains, consisting of two estrogen receptors LBDs joined by an 18 amino acid linker (scER) or of the retinoid X receptor-α linked to the ecdysone receptor with an 18 or a 30 residue long peptide (RE and RLE, respectively) (see Fig. 1E). By fusion of the hormone receptor into the TFZF, the activity of the artificial transcription factors and consequently, the regulated expression of the target genes, were rendered drug-inducible. When expressed transiently, the prototype ligand-dependent transcription factors E2C-scER-VP64, E2C-RE-VP64, and E2C-RLE-VP64 were previously described to up-regulate an ErbB2 promoter driving a luciferase reporter gene in presence of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) and ponasterone-A (ponA) (12). All combinations of CD54−31 and E2C six-zinc fingers, coupled with the scER, RE and RLE inducible domains to the VP64 and KRAB effector domains, were cloned into the retroviral pMX vector. The resulting constructs (pMX-CD54−31-scER-VP64, pMX-CD54−31-scER-KRAB, pMX-CD54−31-RE-VP64, pMX-CD54−31-RE-KRAB, pMX-CD54−31-RLE-VP64, pMX-CD54−31-RLE-KRAB, pMX-E2C-scER-VP64, pMX-E2C-scER-KRAB, pMX-E2C-RE-VP64, pMX-E2C-RE-KRAB, pMX-E2C-RLE-VP64, and pMX-E2C-RLE-KRAB) were transiently co-delivered into the 293-GagPol packaging cell line with a plasmid encoding the VSV pseudotyping viral envelope. The cell supernatants containing the viral particles were applied to HeLa or A431 cells for infection.

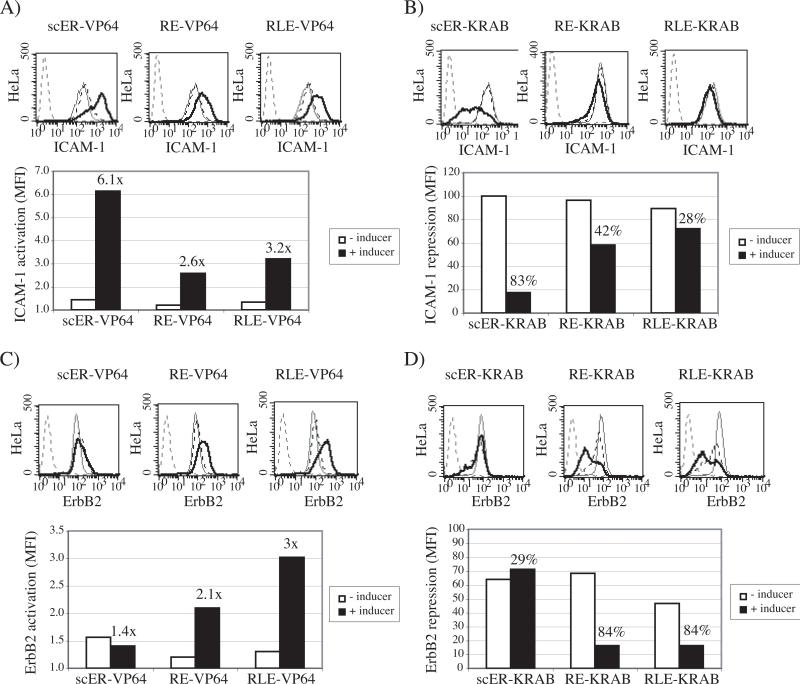

Whereas no induction was observed when the mock-transduced cells were treated with 4-OHT or ponA (not shown), retrovirally delivered iTFZFs efficiently up- and down-regulated the expression of the chromosomal ICAM-1 and the ErbB2 genes in presence of inducers (Fig. 3). Notably, the estrogen receptor-based CD54−31 scER iTFZFs controlled the ICAM-1 gene with virtually no alteration of expression in the absence of drug and with a 6.1-fold activation and a percentage repression equivalent to or better than the constitutive forms in the presence of drug (compare Figs. 3A and B with Fig. 2A). Although the retinoid X/ecdysone receptor gene switches regulated ICAM-1 in HeLa cells less efficiently than the scER iTFZFs, these iTFZFs increased ICAM-1 expression up to 6-fold in A431 cells in the presence of drug (data not shown). The E2C-RE and E2C-RLE endogenous gene switches controlled the ErbB2 target gene with low basal activity and good inducibility, whereas the E2C-scER switches were ineffective (Figs. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

Inducible up- and down-regulation of endogenous genes by single-chain iTFZFs gene switches containing VP64 transactivator or KRAB repressor domains. HeLa cells retrovirally expressing monomeric ICAM-1 and ErbB2 specific estrogen (scER) and retinoid X/ecdysone (RE and RLE) nuclear receptor-based TFZFs were treated with 4-OHT (5 μM) and ponA (100 nM), respectively. Cell-surface expression of target gene products without (dashed black overlay) or after drug induction (thick black overlay) were measured by flow cytometry using specific antibodies and compared to normal protein levels of mock transduced cells (grey overlay) and cell autofluorescence (dashed grey overlay). Bar graphs show the inducible up- and down-regulation of the target gene product by single-chain iTFZFs gene switches in absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of inducer. The calculated MFI is presented in comparison to normal expression levels of mock transduced cells, normalized to 1 in VP64-activator graphs (A and C) and to 100 in KRAB-repressor graphs (B and D). Inducible fold activation and percentage repression are indicated on top of bar graphs. A) Inducible ICAM-1 up-regulation with CD54−31 iTFZFs: scER-VP64, RE-VP64, and RLE-VP64. B) Inducible ICAM-1 down-regulation with CD54−31 iTFZFs: scER-KRAB, RE-KRAB, and RLE-KRAB. C) Inducible ErbB2 up-regulation with E2C iTFZF transactivators: scER-VP64, RE-VP64, and RLE-VP64. D) Inducible ErbB2 down-regulation with E2C iTFZF repressors: scER-KRAB, RE-KRAB, and RLE-KRAB.

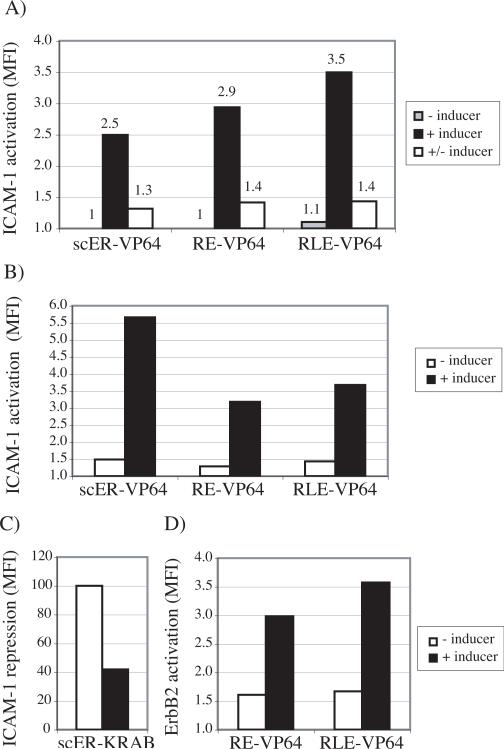

Reversible, sustainable, and latent iTFZFs activity

To investigate the robustness and the reversibility of the inducible activity, cell surface expression of ICAM-1 was determined in HeLa cells transduced with CD54−31-scER, -RE and -RLE iTFZFs fused with the VP64 transactivation domain (Fig. 4A). If no drug was applied, ICAM-1 expression was the same as in untransduced cells. When cells were treated with chemical inducer for 2 days and grown for 7 more days in the presence of drug treatment, expression was up-regulated. When cells were treated with chemical inducer for 2 days and grown for 7 more days in the absence of drug treatment, expression was initially up-regulated and then returned to basal levels. When transduced cells were grown for 11 days and then drug was added for 2 days, the iTFZF activity and ICAM-1 upregulation were similar to that observed when drug was added immediately upon infection (Fig. 4B, compare with Fig. 3A). Accordingly, the E2C-RE-VP64 and the E2C-RLE-VP64 iTFZFs demonstrated a similar robustness in latent inducible activity, regardless of the time of drug addition (i.e. after 1 or 11 days post-transduction) (Fig. 4D, compare to Fig. 3C). These experiments demonstrated that, when linked to the VP64 transactivation domain, the scER-, RE-, and RLE-based gene switches can be kept in inactive or active states or reversed simply by changing drug content in the cell culture media. ICAM-1 repression in cells expressing CD54−31-KRAB iTFZFs was almost fully reversible and showed similar repression after 9 days as after 2 days of drug stimulation (data not shown and Fig. 3B). A notable difference was that for the most potent ICAM-1 inducible repressor, CD54−31-scER-KRAB, only a portion (23%) of the bulk transduced cells were still expressing GFP and thus exhibiting complete ICAM-1 repression (data not shown). Despite the shortfall of cells expressing IRES-linked GFP over time, CD54−31-scER-KRAB expressing cells were not presenting any ICAM-1 repression after an 11 day period without drug, and after that, were still inducible to reach 60% ICAM-1 repression (Fig. 4C), with the most GFP positive cells displaying the most ICAM-1 repression (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Reversible, sustained, and latent induction of ICAM-1 and ErbB2 regulation by iTFZFs. (A) HeLa cells retrovirally expressing CD54−31-scER, -RE, and -RLE iTFZFs with VP64 transactivation domains were treated with inducer for 2 days, grown for 7 more days with drug treatment retained (+ inducer) or removed (+/− inducer), or were not treated at all for the equivalent period of time (− inducer). Cell-surface expression of ICAM-1 was measured by flow cytometry using an anti-ICAM-1 antibody and MFI was normalized to protein levels of mock transduced cells and cell autofluorescence. B-D) Latent induction of gene regulation using iTFZFs. ICAM-1 iTFZF were retrovirally expressed into HeLa cells for 11 days without drug (−), then drug was added (+) for two days. At day 13 post-infection, the cell-surface expression of the target gene products was monitored by FACS. B) ICAM-1 up-regulation with CD54−31-scER, -RE, and –RLE with VP64 transactivator domain. C) ICAM-1 repression with CD54−31-scER-KRAB and D) ErbB2 up-regulation with E2C-RE-VP64 and E2C-RLE-VP64. The calculated MFI is presented in comparison to normal expression levels of mock transduced cells, normalized to 1 in VP64-activator graphs and to 100 in KRAB-repressor graphs.

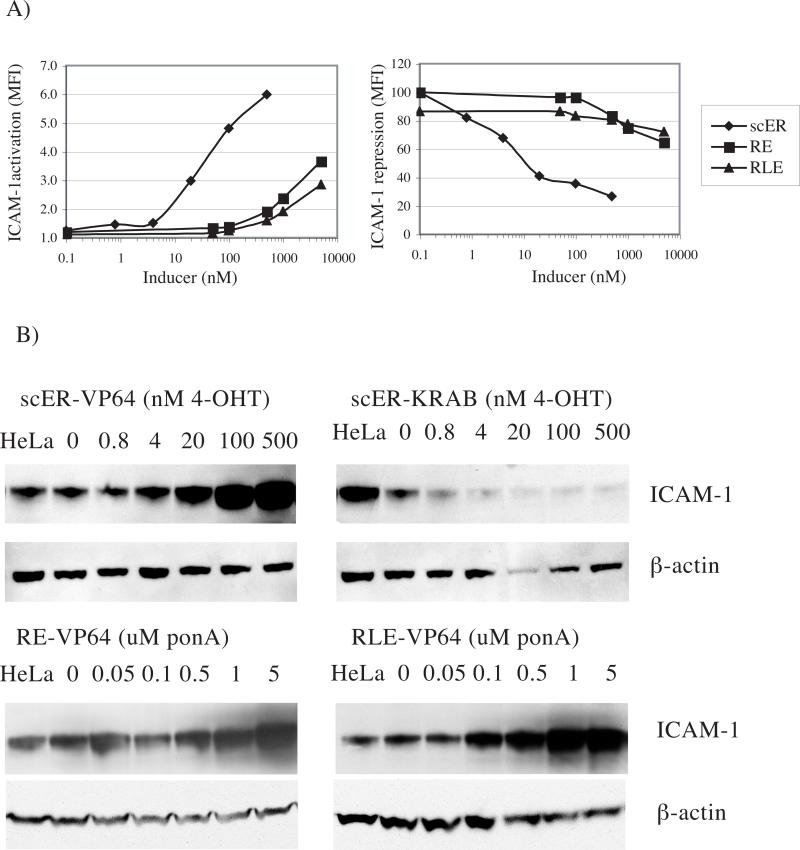

4-OHT and ponA dose-dependent endogenous gene regulation

It is important that the endogenous gene expression in a gene switch system depends on the drug dose. To test this, HeLa cells retrovirally transduced with iTFZF were treated with a range of concentrations of inducer drugs and levels of ICAM-1 protein expression were measured on the cell surface (by FACS) and in extracts (by western blotting) (Fig. 5). The level of ICAM-1 expression on cells that expressed CD54−31-scER-VP64 increased as the concentration of 4-OHT was increased from 4 nM to 500 nM to reach a maximal 6-fold induction. Down-regulation in cells that expressed CD54−31-scER-KRAB was barely measurable at 0.8 nM 4-OHT; at 500 nM 4-OHT, ICAM-1 expression was almost completely repressed. Although less potent, the retinoid X/ecdysone receptor based gene switches were also dose dependent within the range of 100 nM to 5 μM ponA.

Fig. 5.

Dose-dependent control of ICAM-1 expression. CD54−31-scER, –RE, and –RLE iTFZFs with either -VP64 and -KRAB domains were retrovirally expressed in HeLa cells for two days. 4-OHT was added at concentrations ranging from 0.8 to 500 nM or ponA was added at concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 5 μM. ICAM-1 expression was measured on the surface of cells by FACS or in cell extracts by western blot. A) MFI quantification of ICAM-1 activation (normalized to 1 for mock-transduced cells) and repression (normalized to 100 respectively) relative to drug dose. B) Equal total protein amounts of whole cell extracts were separated on denaturing SDS-PAGE with reducing conditions and immunoblotted on PVDF membranes for the detection of ICAM-1 regulation in comparison to constitutive β–actin expression using specific antibodies. Protein expression levels in cells expressing CD54−31 iTFZF (-scER-VP64, -scER-KRAB, –RE-VP64, and -RLE-VP64) treated with drug are compared to uninduced mock-transduced cells (HeLa).

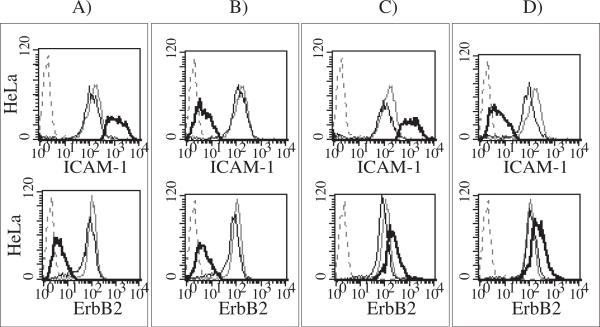

Simultaneous and independent inducible co-regulation of ICAM-1 and ErbB2

When the regulation of two endogenous genes is necessary to achieve a complete phenotypic or therapeutic effect, it would be valuable to combine two target-specific iTFZF with dependence on different drugs. This would allow for either activation or repression in a simultaneous or staggered fashion. To demonstrate these possibilities, HeLa cells were co-transduced with the CD54−31 scER iTFZF and either E2C-RE-KRAB or E2C-RLE-VP64 and then stimulated with 4-OHT and ponA simultaneously (Fig. 6). All combinations of ICAM-1 and ErbB2 co-regulations were achieved: Both genes could be chemically repressed or over-expressed, one gene could be down-regulated, whereas the other was up-regulated, and vice versa. When only one drug was used, only the expected gene was regulated (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Simultaneous, inducible positive and negative control of two genes within the same cells. HeLa cells co-transduced with different retroviral combinations of estrogen-receptor based CD54−31 and retinoid X/ecdysone receptor based E2C iTFZFs were induced with both drugs (thick black overlay) or with only the drug relevant to the iTFZF of the other target gene (black overlay), and protein expression levels were compared to cells not treated with either drug (grey overlay) and cell autofluorescence (dashed grey overlay). A) Up and down: CD54−31-scER-VP64 and E2C-RE-KRAB. B) Double-down: CD54−31-scER-KRAB and E2C-RE-KRAB. C) Double-up: CD54−31-scER-VP64 and E2C-RLE-VP64. D) Down and up: CD54−31-scER-KRAB and E2C-RLE-VP64.

DISCUSSION

In this era of genomics and proteomics, the ability to regulate gene expression with the flick of a switch would provide a valuable tool for discovering novel gene function and pathways. A toolbox of chemically inducible gene switches that provide tunable levels of gene expression, which is both sustainable and reversible, would ensure the necessary control needed for basic biological studies, as well as, for gene therapy applications. Previous studies demonstrated that chemically inducible zinc-finger transcription factors, prepared using single-chain estrogen receptor homodimers and retinoid X/ecdysone receptor heterodimers with engineered LBDs that are not sensitive to endogenous hormones, worked to regulate transcription of reporter genes in response to bioavailable ligand homologs that are considered safe (12). Dent and coworkers used the progesterone receptor in conjunction with a zinc-finger and the p65 activation domain to regulate endogenous VEGF-A (29). Here we have expanded the gene switch toolbox to show that iTFZFs prepared using engineered estrogen receptor and retinoid X/ecdysone receptors can both activate and repress the transcription of endogenous genes.

Key features for inducible gene switches include negligible basal regulation, a dynamic range of regulation that approaches the constitutive system, and especially for gene therapy applications, dose dependent levels of regulation. These features are necessary to ensure tight control of target gene transcription to more closely mimic natural transcriptional control. For ICAM-1 regulation, the scER iTFZF achieves these goals with 6.1-fold activation, 83% repression, and dose dependency over a 1000-fold range of ligand concentration for an overall ICAM-1 expression dynamic range of 35 fold from down to up-regulation (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). Although the results are not as dramatic for ErbB2 regulation, the RE and RLE receptors show up to 3-fold activation, 84% repression for a bidirectional induction ratio of 18 fold, and dose dependency over a 50-fold range of ligand concentration (Figs. 3, 4, and 5).

Sustainability and reversibility of gene regulation is also important for effective inducible gene switches. Stable, long-term expression of a therapeutic protein or repression of a faulty gene is essential for gene therapy applications and when studying the effects of gene expression in tissue culture or animal models. Consistent gene expression should be able to be maintained for the duration of the treatment, through multiple passages of tissue culture, or through the lifetime of the animal. Full and rapid reversibility and a fine tuning rheostat of gene regulation is an important safety feature in the event of adverse reactions in gene therapy. For animal models, reversibility would be advantageous for investigating the effects of activating or repressing a gene at a specific stage of development. All of the iTFZFs showed reversible and sustained activation of ICAM-1 and the RE and RLE iTFZFs also showed sustained activation for ErbB2. Sustained repression of ICAM-1 was also effective with repression after 9 days of drug stimulation similar to repression after 2 days and 60% drug-inducible repression obtainable after 11 days latency without drug. The observed loss of GFP expression could be caused by retroviral expression silencing or negative selection due to an anti-proliferative effect of ICAM-1 repression or iTFZF expression.

Additionally, we have shown that the scER and RE iTFZFs can work in conjunction with each other to independently control endogenous expression of two genes (Fig. 6). When both transcription factors and ligands are present, the levels of up- and down-regulation of the target genes are equivalent to regulation levels seen when they are used separately. When a single ligand is present, only the target iTFZF shows gene regulation. This exquisite control opens the possibility to regulate transcription of two or more genes simultaneously and independently, which could be useful when studying protein-protein interactions or biological pathways, as well as for experimental approaches in systems biology. When combined with large polydactyl-zinc finger libraries such as those used recently (13), iTFZF inducibility would be an important asset for in vivo screening of new gene modulators at a certain time in living organisms. It could also prove advantageous to treat diseases by repressing transcription of a detrimental protein and activating transcription of a therapeutic protein.

The modularity of the zinc-fingers, nuclear receptor ligand-binding domains, and effector domains lend themselves to a flexible system in which the parts can be interchanged. Our results show that the efficacy of iTFZFs varies depending on target promoter and cell line (Fig. 3). For example, the scER iTFZF works very well when targeting the ICAM-1 promoter for both activation and repression, however they were virtually ineffective at regulating ErbB2 expression, whereas the RE and RLE based iTFZF worked in the opposite manner. We also observed different levels of regulation in A431 cells than in HeLa cells (data not shown). Cell-type specific and TFZF dependent activity has also been seen with t constitutive regulators of this type (15). This variation of regulatory ability demonstrates the need for a variety of zinc-fingers, ligand inducible receptors, and effector domains that can be easily assembled in different combinations to optimize performance for the specific application.

Like the system developed by Dent and coworkers (29), the iTFZFs presented in this paper are expressed as a single fusion protein enabling simple gene delivery, which is ideal for gene therapy applications. In addition to allowing for inducible repression and using more specific 6-fingered DBDs, another advantage of our system is the formation of intra-molecular dimers, making dimerization with endogenous nuclear receptors unlikely, thereby reducing the possibility of side effects. The single-chain construction also eliminates the response element repeat requirement of natural nuclear receptors.

In conclusion, we have created inducible transcription factors that can activate and repress the expression of endogenous genes. Regulation was shown to be sustainable, reversible, dose dependent, have a dynamic range similar to constitutive regulators, have negligible basal regulation, and can be used in conjunction with each other. These iTFZFs are valuable tools for genomic and proteomic research and gene therapy applications, where spatiotemporal control of gene expression is essential.

Acknowledgments

*We thank Roger Beerli for providing monomeric ErbB2 gene switches. This study was supported in part by the National Institute of Health Grant CA086258 to C.F.B.. L.M. was the recipient of postdoctoral fellowships from the Swiss National Science Foundation. L.J.S. is supported by The American Cancer Society Illinois Division – Linda M. Campbell Postdoctoral Fellowship.

The abbreviations used are

- DBD

DNA binding domain

- ED

effector domain

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- iTFZF

drug-inducible, engineered zinc finger transcription factor

- ICAM-1

intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- 4-OHT

4-hydroxy tamoxifen

- TFZF

engineered zinc finger transcription factor

- ponA

ponasterone A

- ZFP

zinc finger protein

- 3-ZFP

three finger containing ZFP

- 6-ZFP

6-finger containing ZFP

REFERENCES

- 1.Beerli RR, Barbas CF., 3rd Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamieson AC, Miller JC, Pabo CO. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nrd1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segal DJ, Dreier B, Beerli RR, Barbas CF., III Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2758–2763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dreier B, Segal DJ, Barbas CF., 3rd J Mol Biol. 2000;303:489–502. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreier B, Beerli RR, Segal DJ, Flippin JD, Barbas CF., 3rd J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29466–29478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, Xia Z, Zhong X, Case CC. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3850–3856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreier B, Fuller RP, Segal DJ, Lund CV, Blancafort P, Huber A, Koksch B, Barbas CF., 3rd J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35588–35597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Q, Segal DJ, Ghiara JB, Barbas CF., 3rd Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5525–5530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margolin JF, Friedman JR, Meyer WK, Vissing H, Thiesen HJ, Rauscher FJ., 3rd Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4509–4513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayer DE, Laherty CD, Lawrence QA, Armstrong AP, Eisenman RN. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5772–5781. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beerli RR, Segal DJ, Dreier B, Barbas CF., III Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14628–14633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beerli RR, Schopfer U, Dreier B, Barbas CFI. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32617–32627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blancafort P, Magnenat L, Barbas CF. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:269–274. doi: 10.1038/nbt794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park KS, Lee DK, Lee H, Lee Y, Jang YS, Kim YH, Yang HY, Lee SI, Seol W, Kim JS. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1208–1214. doi: 10.1038/nbt868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnenat L, Blancafort P, Barbas CF., 3rd J Mol Biol. 2004;341:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartsevich VV, Juliano RL. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbi N, Libri V, Fanciulli M, Tinsley JM, Davies KE, Passananti C. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1076–1083. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beerli RR, Dreier B, Barbas CF., III Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1495–1500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040552697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Spratt SK, Liu Q, Johnstone B, Qi H, Raschke EE, Jamieson AC, Rebar EJ, Wolffe AP, Case CC. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33850–33860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu PQ, Rebar EJ, Zhang L, Liu Q, Jamieson AC, Liang Y, Qi H, Li PX, Chen B, Mendel MC, Zhong X, Lee YL, Eisenberg SP, Spratt SK, Case CC, Wolffe AP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11323–11334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren D, Collingwood TN, Rebar EJ, Wolffe AP, Camp HS. Genes Dev. 2002;16:27–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.953802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rebar EJ, Huang Y, Hickey R, Nath AK, Meoli D, Nath S, Chen B, Xu L, Liang Y, Jamieson AC, Zhang L, Spratt SK, Case CC, Wolffe A, Giordano FJ. Nat Med. 2002;8:1427–1432. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toniatti C, Bujard H, Cortese R, Ciliberto G. Gene Ther. 2004;11:649–657. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu D, Ye D, Fisher M, Juliano RL. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:963–971. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang JS, Kim JS. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8742–8748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollock R, Giel M, Linher K, Clackson T. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:729–733. doi: 10.1038/nbt0702-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Constantinescu SN, Sun Y, Bogan JS, Hirsch D, Weinberg RA, Lodish HF. Anal Biochem. 2000;280:20–28. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harwerth I-M, Wels W, Marte BM, Hynes NE. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:15160–15167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dent CL, Lau G, Drake EA, Yoon A, Case CC, Gregory PD. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1362–1369. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]