Abstract

Gene transfer to salivary glands leads to abundant secretion of transgenic protein into either saliva or the bloodstream. This indicates significant clinical potential, depending on the route of sorting. The aim of this study was to probe the sorting characteristics of human parathyroid hormone (hPTH) in two animal models for salivary gland gene transfer. PTH is a key hormone regulating calcium levels in the blood. A recombinant serotype 5 adenoviral vector carrying the hPTH cDNA was administered to the submandibular glands of mice and rats. Two days after delivery, high levels of hPTH were found in the serum of mice, leading to elevated serum calcium levels. Only low amounts of hPTH were found in the saliva. Two days after vector infusion into rats, a massive secretion of hPTH was measured in saliva, with little secretion into serum. Confocal microscopy showed hPTH in the glands, localized basolaterally in mice and apically in rats. Submandibular gland transduction was effective and the produced hPTH was biologically active in vivo. Whereas hPTH sorted toward the basolateral side in mice, in rats hPTH was secreted mainly at the apical side. These results indicate that the interaction between hPTH and the cell sorting machinery is different between mouse and rat salivary glands. Detailed studies in these two species should result in a better understanding of cellular control of transgenic secretory protein sorting in this tissue.

Introduction

The homeostasis of free calcium in the blood is critically important for normal physiological functions throughout the body. Calcium serves as a structural element in bone, but is also an important cellular ionic messenger with many functions involving blood clotting, muscle contraction, and transmission of nerve impulses.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is an essential hormone for the regulation of serum calcium levels. PTH is secreted by the parathyroid glands as a polypeptide containing 84 amino acids in response to low serum calcium levels (Poole and Reeve, 2005). It acts to increase the concentration of calcium in the blood, primarily by mobilizing calcium from bone (Potts, 2005). To do this, PTH binds to its receptor on osteoblasts, which in turn upregulates RANKL (receptor activator for nuclear factor κB ligand). RANKL binds to RANK on the surface of precursor osteoclasts, leading to their maturation and enabling the breakdown of bone and subsequent release of free calcium (Blair and Zaidi, 2006). PTH also enhances active calcium reabsorption in the kidney and, by converting vitamin D3 to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, in the intestine. When serum calcium levels are high, negative feedback inhibits PTH secretion by the parathyroid glands (Jurutka et al., 2007). In addition, calcitonin produced by the parafollicular cells (C cells) of the thyroid gland can decrease calcium concentration (Pondel, 2000).

Considering the tight regulation of serum calcium levels, hypoparathyroidism is a serious metabolic disorder. Untreated, hypoparathyroidism causes seizures, tetany, and death (Maeda et al., 2006). Common causes of hypoparathyroidism are injury to the gland during thyroid or parathyroid surgery (Thomusch et al., 2003) or autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (Alimohammadi et al., 2008). Conventional therapy involves vitamin D analogs and calcium supplementation. This costly treatment is not only inconvenient due to extensive monitoring, but these patients do not regain the calcium-retaining action in the kidney, resulting in hypercalciuria despite normal calcium levels. PTH replacement therapy has been shown to be clinically superior to conventional therapy (Winer et al., 1996). However, two daily injections of PTH are required for effective treatment (Winer et al., 1998). This regimen is expensive and is not physiologically ideal, providing a strong rationale for a more effective delivery system.

We propose to take advantage of the efficient protein-producing capacity of the salivary glands (Castle and Castle, 1998). Salivary glands are an attractive target tissue for gene transfer (Baum et al., 2004). They are readily accessible by ductal cannulation and the vector does not need to be introduced systemically to achieve high levels of transgenic protein. This approach shows great potential for treating single-protein deficiencies and certain conditions of the upper gastrointestinal tract, depending on the route of sorting.

Salivary glands are polarized epithelia having as a primary role the exocrine production of saliva. However, salivary glands can secrete exocrine and endocrine proteins to either the apical pole or the basolateral pole of the cells (Lawrence et al., 1977; Leonora et al., 1987; Baum et al., 1999; Isenman et al., 1999). Unfortunately, the direction of this secretion is not readily predictable for all transgenic proteins. In polarized epithelium, it is generally accepted that endogenous proteins have specific sorting signals that are recognized by the cell machinery directing the protein to the apical or basolateral cell surface. The endogenous sorting of membrane proteins and a few soluble proteins have been studied in polarized cell cultures, but the mechanisms described are complex and do not seem to involve universal signals that are similar for proteins or cell types (Arvan and Halban, 2004; Rodriguez-Boulan et al., 2005). Several factors are known to affect the polarity of secretion of a transgenic protein in salivary glands cells, such as the pH of the secretory pathway (Venkatesh and Gorr, 2002; Venkatesh et al., 2007), the composition of cargo proteins (Fasciotto et al., 2008), and glycosylation (Potter et al., 2006).

Before proposing a clinical gene transfer application for human PTH (hPTH), it is essential to study its sorting in vivo, in order to predict the secretion pathways followed in human salivary glands. In this study, for the first time, we examine the potential of hPTH gene transfer to the salivary glands. Specifically, we have studied hPTH secretion in mice and rats after transduction of salivary glands with a serotype 5 adenovirus (Ad5).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Both BALB/c mice (male and female, n = 6 per treatment group) and male Wistar rats (n = 5 per treatment group) were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Walkersville, MD) at 6 weeks of age. They were acclimated for 1 week before the start of experiments, and water and food were provided ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and by the Biosafety Committee of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD).

Recombinant adenovirus construction

The hPTH carrier plasmid (GeneCopoeia, Germantown, MD) was digested with XmnI and XhoI and the obtained hPTH cDNA was directionally cloned into the adenoviral expression shuttle plasmid pACCMV-pLpA containing a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and a simian virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation signal. The resulting plasmid, pACCMV-hPTH, was confirmed by sequencing and hPTH expression was tested in vitro with 293 cells.

An E1-deleted recombinant Ad5 vector was generated as previously described (He et al., 1998a). Briefly, pACCMV-hPTH and pJM17 were cotransfected into C7 cells by calcium phosphate precipitation. The generated Ad.hPTH was amplified in 293 cells and the crude viral lysate was purified by two rounds of CsCl gradient centrifugation as previously reported (Delporte et al., 1996). The control vector used in this study was an Ad5 expressing human erythropoietin (hEPO) driven by a CMV promoter (Ad.hEPO) (Voutetakis et al., 2005), which was amplified and purified in parallel.

Determination of vector titer

Physical viral particle titer (VP) was measured by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) against a standard curve. SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used in an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems). The conditions were as follows: 95°C for 2 min, 95°C for 8 min, 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1 min for 40 cycles. The primers were designed to amplify part of the CMV promoter region: forward, 5′-CAT-CTA-CGT-ATT-AGT-CAT-CGC-TAT-TAC-3′; reverse, 5′-TGG-AAA-TCC-CCG-TGA-GTC-A-3′. Q-PCR assays were performed in duplicate, with all samples and standards in triplicate.

In vitro cell transductions

In vitro studies were done with the SMIE cell line (He et al., 1998b) and the A5 cell line (Brown et al., 1989); both are rat submandibular cell lines. Cells were seeded at 80% confluence in 12-well plates in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)–10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and transduced with Ad.hPTH at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) ranging from 102 to 2 × 104. Medium was harvested 48 hr later and stored at −80°C until assayed. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

In vivo gene transfer to submandibular glands

Animals were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of a mixture of ketamine chloride (60 mg/kg; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine (6 mg/kg; Phoenix Scientific, St. Joseph, MO) before cannulation of both submandibular glands with modified PE-10 polyethylene tubing (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) as previously reported (Wang et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2008). Atropine was delivered intramuscularly (0.5 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 10 min before vector infusion to decease salivary flow.

Vectors were suspended in 50 μl (mice) or 200 μl (rats) of saline and delivered to both submandibular ducts by retrograde instillation at doses of 109 and 1010 VP/gland (mice) or 5 × 109 and 5 × 1010 VP/gland (rats). After infusion, syringes were left in place for 10 min to prevent backflow of fluid.

Forty-eight hours later, animals were reanesthetized as described above with ketamine–xylazine and thereafter administered a subcutaneous injection of pilocarpine (0.5 mg/kg) to stimulate salivary flow. Saliva was collected as described (Wang et al., 2006) and snap frozen immediately. Animals were killed in a CO2 chamber and, after death was confirmed by bilateral thoracotomy, blood was collected via the vena cava and serum was separated and stored at −80°C. Submandibular glands were removed and cleaned, and each gland was cut in half longitudinally. One part was snap frozen and the other part was fixed in buffered 4% formaldehyde solution for 24 hr at 4°C, and then stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C until paraffin embedding.

Analytical determinations

For Western blot detection, 30 μl samples of medium were mixed with loading buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and heated at 96°C for 4 min before electrophoresis in a 4–15% gradient Tris-HCl precast polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The proteins were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk, and incubated with rabbit anti-hPTH (diluted 1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 1 hr at room temperature. Membranes were placed in a 1:5500 dilution of anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody solution (Amersham Health, Arlington Heights, IL) for 1 hr. Finally, membranes were incubated for 3 min in chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and exposed to Kodak BioMax MR film (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY).

Human PTH was measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit from ALPCO Diagnostics (Salem, NH) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Before samples were measured, a spike assay was done to reveal which dilutions showed no inhibition with saliva or serum. Each sample was measured in duplicate and compared with a simultaneously performed standard curve. The serum-to-saliva distribution ratio for hPTH was calculated as described previously (Baum et al., 1999; Hoque et al., 2001).

Calcium was determined by indirect potentiometry, using a calcium ion-selective electrode in conjunction with a sodium reference electrode. ISE electrolyte buffer reagent and ISE electrolyte reference reagent (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions and samples were processed on a Synchron LX-20 (Beckman Coulter).

Inorganic phosphorus was measured in a time-rated reaction with ammonium molybdate in an acidic solution to form a colored phosphomolybdate complex. The change in absorbance of this yellow complex was measured at 365 nm.

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

Paraffin-embedded sections (thickness, 5 μm) were dewaxed and rehydrated in a gradient of alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed thereafter by heating the sections for 10 min at 121°C in 0.1 M citric acid, pH 6.0. After incubation with a blocking solution containing 10% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min, slides were incubated with rabbit anti-hPTH (AnaSpec, San Jose, CA) at 20 μg/ml in 0.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature, washed with PBS, and incubated with the secondary antibody (diluted 1:200, Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) together with phalloidin (diluted 1:200; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hr at room temperature. After extensive washing, sections were mounted in VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were collected with a Leica confocal microscope and MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). As an internal control, an irrelevant rabbit IgG was used as primary antibody.

Statistics

Differences in means between groups were determined by the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by a Mann–Whitney U rank-sum test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were done with SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Results

In vitro production of hPTH

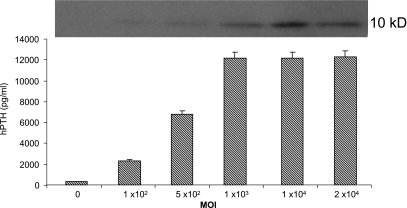

After transduction of SMIE cells with Ad.hPTH, secretion of hPTH was considerable and vector dose dependent. This was evident by both Western blotting (Fig. 1, top) and ELISA (Fig. 1, bottom). With an MOI of 1000, the production of hPTH was ~12 ng/ml. Similar results were obtained with A5 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Secretion of hPTH from SMIE cells after transduction in vitro with Ad.hPTH. SMIE cells were incubated with the indicated MOIs of Ad.hPTH. After 48 hr, medium was harvested and assayed for hPTH by Western blot (top) and ELISA (bottom). The data shown are representative of two experiments performed in duplicate and are displayed as means ± SEM.

hPTH production after administration of Ad.hPTH to mouse salivary glands in vivo

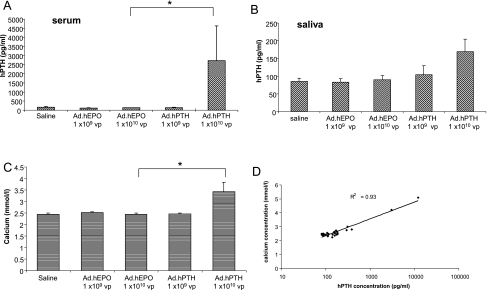

We administered 109 or 1010 VP of Ad.hPTH to the submandibular glands of male and female mice by retrograde ductal infusion. In addition to treating mice with saline, dose-matched Ad.hEPO was used as vector control. Forty-eight hours after administering the vector, we measured the secretion of hPTH in serum and saliva. hPTH levels were unchanged in mice infused with 109 VP compared with controls (Fig. 2A). However, delivery of 1010 VP of Ad.hPTH led to significant (p = 0.004) production of hPTH detected in the serum of these mice. In contrast, only a slight increase (p = 0.07) above background in hPTH concentration was found in the saliva of mice receiving 1010 VP of Ad.hPTH (Fig. 2B). No differences between male and female mice were observed (data not shown) and their values are combined here.

FIG. 2.

Distribution and biological effect of hPTH in mice after administration of Ad.hPTH to both submandibular glands by retrograde ductal instillation. Two doses were given: 1 × 109 or 1 × 1010 VP/gland. Saline and an irrelevant vector, Ad.hEPO, were used as controls. Human PTH was measured by ELISA in serum (A, p = 0.004) and saliva (B) 2 days after vector infusion. The free calcium concentration in serum was determined by indirect potentiometry (C, p = 0.002) and thereafter was plotted against hPTH levels in serum to reveal a high correlation (D). Data are shown as means ± SEM (A–C) and as individual data points (D).

Biological activity of hPTH after gene transfer to mouse salivary glands

We next assayed free calcium levels in the serum of Ad.hPTH-treated mice. PTH is known to increase serum calcium levels by mobilizing calcium from bone and enhancing the absorption of calcium in kidney and intestine. Indeed, a significant (41% on average; p = 0.002) elevation of free calcium in the sera of mice treated with the highest dose of vector was observed (Fig. 2C). The concentrations of hPTH and calcium in the serum of individual mice were highly correlated (R2 = 0.93), providing strong evidence of the biological activity of vector-mediated hPTH secreted from salivary glands (Fig. 2D). We observed no differences in phosphorus levels in serum; however, increased urinary phosphorus was found in treated animals (data not shown).

Vector-derived hPTH production after salivary gland transduction in rats

Similar to our experiments in mice, we delivered two doses (5 × 109 and 5 × 1010 VP/gland) to the submandibular glands of rats. Given that administration of Ad.hEPO was without effect on hPTH or calcium levels in mice, that is, similar to saline-treated mice, the rat treatment groups were compared with saline-infused animals only. Two days after vector delivery, serum and saliva were collected and assayed for hPTH.

On average, a small, statistically insignificant increase was seen in serum hPTH levels in the highest dose group (Fig. 3A; p = 0.15). Despite this lack of statistical significance, there was a highly significant correlation between serum hPTH and calcium levels (R2 = 0.97). Conversely, in saliva an enormous secretion of hPTH (up to ~15 ng/ml) was detected at both vector doses (p = 0.016 and p = 0.008, respectively). This hPTH production was dose dependent (Fig. 3B). As an additional test to determine whether vector-encoded hPTH mediated biological activity in rats, four rats were injected systemically (intravenously, same dose as delivered to the glands: 5 × 1010 VP) with Ad.hPTH. After 2 days, the animals showed significant hPTH levels in serum and, consequently, elevated calcium levels compared with saline-treated controls (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Production of hPTH in rats after transduction of both submandibular glands with Ad.hPTH. Ad.hPTH at either 5 × 109 or 5 × 1010 VP/gland was introduced into glands by cannulating the ducts. Saline was used as a control. Two days after vector delivery, serum (A) and saliva (B, p = 0.016 for 5 × 109 VP and p = 0.008 for 5 × 1010 VP, compared with control) were assayed for hPTH by ELISA.

Species-specific hPTH sorting difference in salivary glands

The contrast in hPTH sorting and secretion between rats and mice is striking. Table 1 shows the serum-to-saliva ratio of total hPTH secreted. These ratios clearly demonstrate this dramatic difference in sorting of the same protein expressed from the same vector in these two commonly studied rodent species. Whereas after transduction of salivary glands in mice hPTH is secreted primarily at the basolateral side into the bloodstream, in rats hPTH was secreted predominantly at the apical side into saliva. In mice, the lower vector dose used was apparently too low to result in significant production of hPTH. In rats, however, the lower dose resulted primarily in hPTH secretion into saliva.

Table 1.

Distribution Ratio of Human Parathyroid Hormone after Transduction of Mouse and Rat Submandibular Glandsa

| Mouse | Rat | |

|---|---|---|

| High dose | 613 ± 527 | 0.93 ± 0.47 |

| Low dose | ND | <0.01 |

Ratios are shown as total production in serum:total production in saliva ± SEM. High dose represents 1 × 1010 VP/gland in mice and 5 × 1010 VP/gland in rats. Low doses are 1 log lower in both species.

ND, none detected.

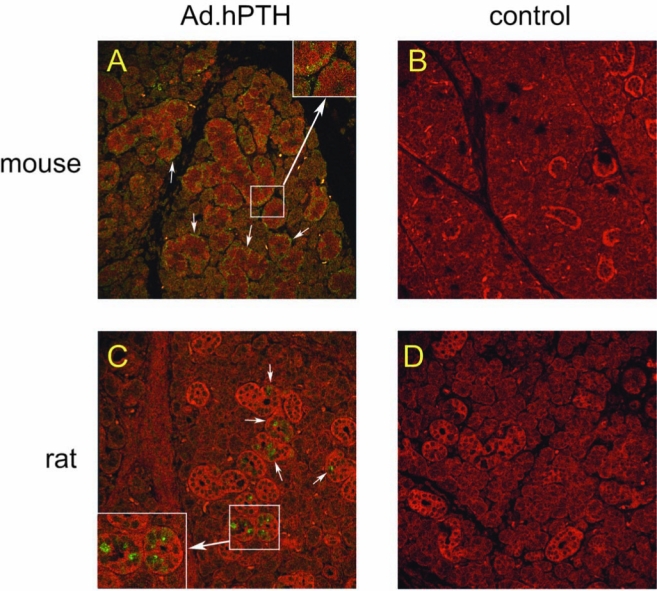

Cellular localization of hPTH in transduced salivary glands by immunofluorescence

Two days after vector infusion, salivary glands were excised and fixed in formaldehyde. After being embedded in paraffin, glands were sectioned and fluorescently labeled with an antibody directed against hPTH, using phalloidin to visualize cell morphology.

Even after stimulation with pilocarpine, hPTH was clearly visible in all treated glands, albeit more abundant in mouse glands (Fig. 4A and C). The cellular localization of hPTH was different between species (Fig. 4A and C, arrows). Whereas in mice hPTH was found mainly on the basolateral side of the cells, in rats hPTH was located preferentially on the apical side. Neither control mice (Fig. 4B) nor control rats (Fig. 4D) demonstrated a significant positive signal after staining with the anti-hPTH antibody. The irrelevant IgG control also did not exhibit staining (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Detection and localization of hPTH in transduced salivary glands. Two days after vector infusion, submandibular glands were removed, fixed in formaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Subsequent to sectioning, slides were immunofluorescently stained for hPTH (green), and phalloidin was used to visualize gland morphology (red). A transduced mouse gland is shown in (A) and a control mouse gland is shown for comparison (B). A rat gland after transduction is displayed in (C), and a control rat gland is shown for comparison (D). Arrows indicate the cellular localization of hPTH. Original magnification: 100×. Insets in (A) and (C): Enlargements of boxed areas.

Discussion

Herein, we tested the hypothesis that biologically active hPTH can be produced by salivary glands in vivo after gene transfer. Previously, we demonstrated that salivary gland cells can distinguish and sort transgenic proteins to distinct extracellular locales in vivo (Baum et al., 1999). Thus, understanding the sorting of hPTH in salivary glands is essential for any eventual clinical application with these tissues. Protein sorting can differ between cells growing in vitro and in an in vivo, native situation. For example, secretion of human growth hormone is nonpolarized in cultured MDCK cells (Gottlieb et al., 1986), basolateral in cultured colon epithelial cells (Rindler and Traber, 1988), and apical in salivary glands in vivo (Baum et al., 1999). PTH, under normal physiological conditions, is stored in secretory granules and secreted in a regulated manner by the parathyroid gland into the bloodstream.

In mice, we found that after salivary gland transduction the levels of hPTH in serum were quite significant. Conversely, only a modest amount of hPTH was found in the saliva of these mice, that is, hPTH secretion was primarily in an endocrine direction in mouse salivary glands. Although less commonly considered, secretion into the bloodstream from the salivary glands is well described and occurs via ill-defined basolateral secretory pathways (Kagami et al., 1996; Baum et al., 1999; Isenman et al., 1999; Gorr et al., 2005). The immunofluorescent staining of transduced mouse glands revealed a significant accumulation of hPTH on the basolateral side of parenchymal cells, consistent with the hypothesis that hPTH was sorted to the basolateral pole after entry to the trans-Golgi network.

Once in the bloodstream, transgenic hPTH was biologically active, and we showed that hPTH clearly elevated serum calcium levels in mice. Indeed, there was a strong correlation between hPTH and calcium levels in serum, and the observed increase was considerable in view of the strong feedback regulation by both hPTH itself and by calcitonin in these physiologically intact mice.

After infusion of Ad.hPTH into rat salivary glands, there was minimal secretion of hPTH into serum, and only at the highest vector dose. However, there was still a highly significant correlation between serum hPTH and calcium levels in these animals (R2 = 0.97). In contrast, saliva contained extremely high amounts of hPTH. The difference between mice and rats was striking, both in absolute levels and in the serum-to-saliva ratio of total hPTH secreted. Clearly, in rats hPTH sorted primarily toward the apical membrane and on immunofluorescent staining hPTH was found in the apical region of salivary epithelial cells. The exact pathways used to achieve this apical secretion of hPTH remain to be elucidated, and could involve the major regulated secretory pathway (dense-core granules) (Castle and Castle, 1998), as well as the minor regulated and constitutive-like secretory pathways, both of which originate in immature secretory granules (Castle and Castle, 1996). Given the amount of hPTH produced by the transduced rat submandibular glands, the hPTH secretion found in serum may in part result from a spillover effect due to saturation of the apical pathway (Marmorstein et al., 2000).

Although the specific mechanism(s) responsible for the species differences in hPTH sorting are still unclear, there are several possible reasons that can be experimentally tested. For example, it is possible that a specific amino acid sequence found in hPTH can facilitate its secretion to an exocrine pathway in rats, but is not recognized by the sorting machinery in mouse salivary cells. Indeed, in the biologically active part of the hPTH molecule, there are five amino acids that differ between human and mouse or rat PTH (Potts, 2005). Also, it is possible that hPTH propeptide processing is different in mouse and rat salivary glands, which could impair entry or storage of hPTH protein in murine secretory granules, resulting in its secretion into the constitutive pathway (bloodstream). It is widely recognized that the intracellular pathways followed by secretory proteins in epithelial cells are directed by a large repertoire of carefully regulated molecules (Rodriguez-Boulan et al., 2005). Thus, there are numerous intracellular steps wherein a genetic or metabolic change could lead to a difference in the final destination of the transgenic protein (Folsch et al., 1999; Cosen-Binker et al., 2007, 2008).

Extrapolating our results to eventual hPTH gene transfer to human salivary glands remains difficult. If hPTH gene transfer to human glands were to lead primarily to exocrine secretion of the transgene product, as it does in rats, secretion into the bloodstream would need to be increased for a clinical application. This might be achieved, for example, by concurrent administration of a weak base such as hydroxychloroquine (Hoque et al., 2001). Regardless, longer lasting hPTH expression than seen with an Ad5 vector also needs to be achieved. Serotype 2 adeno-associated viral (AAV2) vectors lead to long-term stable transgene expression in salivary glands (Voutetakis et al., 2004), and seem well suited to addressing this need.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that biologically active hPTH is readily produced after transduction of salivary glands. Theoretically, our findings suggest the potential for hPTH gene therapy for the treatment of hypothyroidism. However, the differential sorting of hPTH after transduction of mouse and rat salivary glands indicates that the interaction between hPTH and the cell sorting machinery in different salivary glands needs to be clarified. Comprehensive studies in these species should result in a better understanding of cellular sorting mechanisms operative in salivary glands and could eventually lead to an innovative therapy for patients with hypoparathyroidism and other systemic disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health. The authors thank A. Voutetakis for help with the initiation of this study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Alimohammadi M. Bjorklund P. Hallgren A. Pontynen N. Szinnai G. Shikama N. Keller M.P. Ekwall O. Kinkel S.A. Husebye E.S. Gustafsson J. Rorsman F. Peltonen L. Betterle C. Perheentupa J. Akerstrom G. Westin G. Scott H.S. Hollander G.A. Kampe O. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 and NALP5, parathyroid autoantigen. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1018–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvan P. Halban P.A. Sorting ourselves out: Seeking consensus on trafficking in the beta-cell. Traffic. 2004;5:53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum B.J. Berkman M.E. Marmary Y. Goldsmith C.M. Baccaglini L. Wang S.L. Wellner R.B. Hoque A.T.M.S. Atkinson J.C. Yamagishi H. Kagami H. Parlow A.F. Chao J.L. Polarized secretion of transgene products from salivary glands in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999;10:2789–2797. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum B.J. Voutetakis A. Wang J.H. Salivary glands: Novel target sites for gene therapeutics. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10:585–590. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair H.C. Zaidi M. Osteoclastic differentiation and function regulated by old and new pathways. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2006;7:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A.M. Rusnock E.J. Sciubba J.J. Baum B.J. Establishment and characterization of an epithelial-cell line from the rat submandibular-gland. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1989;18:206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle D. Castle A. Intracellular transport and secretion of salivary proteins. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1998;9:4–22. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle J.D. Castle A.M. Two regulated secretory pathways for newly synthesized parotid salivary proteins are distinguished by doses of secretagogues. J. Cell Sci. 1996;109:2591–2599. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.10.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosen-Binker L.I. Lam P.P.L. Binker M.G. Reeve J. Pandol S. Gaisano H.Y. Alcohol/cholecystokinin-evoked pancreatic acinar basolateral exocytosis is mediated by protein kinase Cα phosphorylation of Munc18c. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:13047–13058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosen-Binker L.I. Binker M.G. Wang C.C. Hong W. Gaisano H.Y. VAMP8 is the v-SNARE that mediates basolateral exocytosis in a mouse model of alcoholic pancreatitis. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2535–2551. doi: 10.1172/JCI34672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delporte C. O'Connell B.C. He X.J. Ambudkar I.S. Agre P. Baum B.J. Adenovirus-mediated expression of aquaporin-5 in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22070–22075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasciotto B.H. Kuehn U. Cohn D.V. Gorr S.U. Secretory cargo composition affects polarized secretion in MDCK epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2008;310:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9666-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch H. Ohno H. Bonifacino J.S. Mellman I. A novel clathrin adaptor complex mediates basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells. Cell. 1999;99:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorr S.U. Venkatesh S.G. Darling D.S. Parotid secretory granules: Crossroads of secretory pathways and protein storage. J. Dental Res. 2005;84:500–509. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb T.A. Beaudry G. Rizzolo L. Colman A. Rindler M. Adesnik M. Sabatini D.D. Secretion of endogenous and exogenous proteins from polarized MDCK cell monolayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986;83:2100–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.7.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. Goldsmith C.M. Marmary Y. Wellner R.B. Parlow A.F. Nieman L.K. Baum B.J. Systemic action of human growth hormone following adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to rat submandibular glands. Gene Ther. 1998a;5:537–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. Kuijpers G.A.J. Goping G. Kulakusky J.A. Zheng C.Y. Delporte C. Tse C.M. Redman R.S. Donowitz M. Pollard H.B. Baum B.J. A polarized salivary cell monolayer useful for studying transepithelial fluid movement in vitro. Pflugers Arch. 1998b;435:375–381. doi: 10.1007/s004240050526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque A.T.M.S. Baccaglini L. Baum B.J. Hydroxychloroquine enhances the endocrine secretion of adenovirus-directed growth hormone from rat submandibular glands in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001;12:1333–1341. doi: 10.1089/104303401750270986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenman L. Liebow C. Rothman S. The endocrine secretion of mammalian digestive enzymes by exocrine glands. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:E223–E232. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.2.E223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurutka P.W. Bartik L. Whitfield G.K. Mathern D.R. Barthel T.K. Gurevich M. Hsieh J.C. Kaczmarska M. Haussler C.A. Haussler M.R. Vitamin D receptor: Key roles in bone mineral pathophysiology, molecular mechanism of action, and novel nutritional ligands. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22:V2–V10. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.07s216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagami H. O'Connell B.C. Baum B.J. Evidence for the systemic delivery of a transgene product from salivary glands. Hum. Gene Ther. 1996;7:2177–2184. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.17-2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence A.M. Tan S. Hojvat S. Kirsteins L. Salivary gland hyperglycemic factor: An extrapancreatic source of glucagon-like material. Science. 1977;195:70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.63992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonora J. Tieche J.M. Celestin J. Physiological factors affecting secretion of parotid hormone. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;252:E477–E484. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.252.4.E477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S.S. Fortes E.M. Oliveira U.M. Borba V.C. Lazaretti-Castro M. Hypoparathyroidism and pseudo-hypoparathyroidism. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;50:664–673. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302006000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein A.D. Csaky K.G. Baffi J. Lam L. Rahaal F. Rodriguez-Boulan E. Saturation of, and competition for entry into, the apical secretory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:3248–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070049497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondel M. Calcitonin and calcitonin receptors: Bone and beyond. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2000;81:405–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2000.00176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K.E.S. Reeve J. Parathyroid hormone: A bone anabolic and catabolic agent. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2005;5:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter B.A. Hughey R.P. Weisz O.A. Role of N- and O-glycans in polarized biosynthetic sorting. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2006;290:C1–C10. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00333.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts J.T. Parathyroid hormone: Past and present. J. Endocrinol. 2005;187:311–325. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindler M.J. Traber M.G. A specific sorting signal is not required for the polarized secretion of newly synthesized proteins from cultured intestinal epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:471–479. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Boulan E. Geri K. Musch A. Organization of vesicular trafficking in epithelia. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrm1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomusch O. Machens A. Sekulla C. Ukkat J. Brauckhoff M. Dralle H. The impact of surgical technique on postoperative hypoparathyroidism in bilateral thyroid surgery: A multivariate analysis of 5846 consecutive patients. Surgery. 2003;133:180–185. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh S.G. Gorr S.U. A sulfated proteoglycan is necessary for storage of exocrine secretory proteins in the rat parotid gland. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C438–C445. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00552.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh S.G. Tan J. Gorr S.U. Darling D.S. Isoproterenol increases sorting of parotid gland cargo proteins to the basolateral pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C558–C565. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00081.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutetakis A. Kok M.R. Zheng C.Y. Bossis I. Wang J.H. Cotrim A.P. Marracino N. Goldsmith C.M. Chiorini J.A. Loh Y.P. Nieman L.K. Baum B.J. Reengineered salivary glands are stable endogenous bioreactors for systemic gene therapeutics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:3053–3058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400136101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutetakis A. Bossis I. Kok M.R. Zhang W.T. Wang J.H. Cotrim A.P. Zheng C.Y. Chiorini J.A. Nieman L.K. Baum B.J. Salivary glands as a potential gene transfer target for gene therapeutics of some monogenetic endocrine disorders. J. Endocrinol. 2005;185:363–372. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.H. Voutetakis A. Mineshiba F. Illei G.G. Dang H.W. Yeh C.K. Baum B.J. Effect of serotype 5 adenoviral and serotype 2 adeno-associated viral vector-mediated gene transfer to salivary glands on the composition of saliva. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17:455–463. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer K.K. Yanovski J.A. Cutler G.B. Synthetic human parathyroid hormone 1–34 vs calcitriol and calcium in the treatment of hypoparathyroidism: Results of a short-term randomized crossover trial. JAMA. 1996;276:631–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer K.K. Yanovski J.A. Sarani B. Cutler G.B. A randomized, cross-over trial of once-daily versus twice-daily parathyroid hormone 1–34 in treatment of hypoparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:3480–3486. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C. Vitolo J.M. Zhang W. Mineshiba F. Chiorini J.A. Baum B.J. Extended transgene expression from a nonintegrating adenoviral vector containing retroviral elements. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1089–1097. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]