Summary

The MHC class I molecules present thousands of peptides (pMHC I) on the cell surface for immune surveillance by CD8 T cells. The pMHC I repertoire normally contains peptides of perfect length and sequences suitable for binding each MHC I. The peptides are made by first fragmenting cytoplasmic proteins. The fragments are then transported into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where they are trimmed to appropriate length by the ER aminopeptidase associated with antigen processing (ERAAP) to generate the final pMHC I. Here we review studies on the role of ERAAP in generating pMHC I from endogenous or viral proteins and their ability to elicit CD8 T cell responses. The absence of ERAAP profoundly disrupts the pMHC I repertoire which can have major consequences on the immune responses to endogenous and viral antigens.

Introduction

The cytotoxic or CD8 T lymphocyte repertoire is important for adaptive immune responses towards intracellular pathogens and cancer. To warn the CD8 T cells, normal cells constitutively display their protein content on the surface in the form of peptides bound to major histocompatibility complex class I molecules (pMHC I). When proteins are mutated in cancer, or when viral or bacterial proteins are expressed in infected cells, the pMHC I repertoire includes new peptides from these proteins. The presence of these foreign pMHC I allows the CD8 T cells to specifically recognize and to eventually eliminate the infected or cancer cells. Thus, effective immune surveillance depends upon the cells’ ability to generate a diverse pMHC I repertoire via the antigen processing pathway [1].

The diversity of peptides presented by MHC I is further amplified by multiple loci encoding the MHC I molecules as well as sequence polymorphisms among different individuals of the species. In humans, more than 2000 different alleles are currently known for MHC I (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/imgt/hla/stats.html). Each of these MHC I molecules presents thousands of different peptides. For every MHC I, the set of 8–10 amino acid peptides shares a consensus motif defined by two or three conserved residues [2]. The conserved residues keep the peptide firmly anchored to corresponding pockets in the peptide-binding groove of the MHC I molecule [3]. Yet, the amino acid variations at the non-conserved positions ensure that the overall diversity of peptides presented by MHC I can theoretically reach billions of sequences.

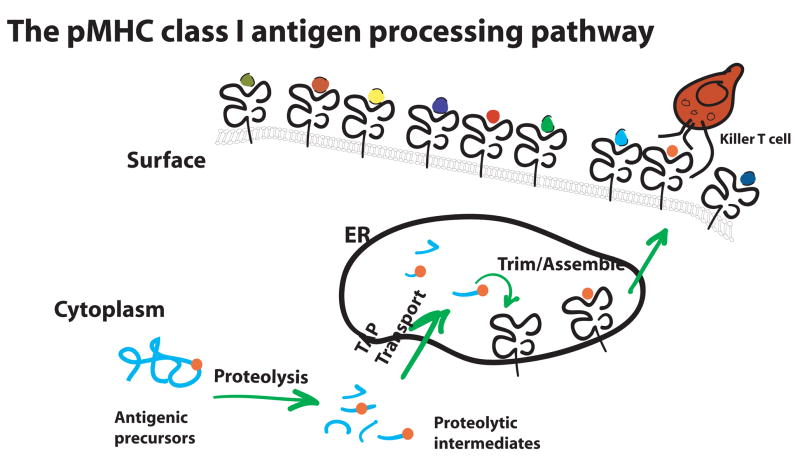

The antigen processing pathway that generates the peptide cargo for MHC I begins in the cytoplasm (Fig 1). The multi-catalytic proteasome, with the assistance of other proteases and chaperones, fragments proteins into smaller polypeptides [4,1]. These proteolytic intermediates are then transported into the ER by TAP, the transporter associated with antigen processing. Analysis of proteolysis of model antigens in vitro and in vivo suggests that the pool of proteolytic intermediates entering the ER possess the proper C-terminal anchor residue required to bind MHC I molecules but contain extra N-terminal residues [5–7].

Figure 1.

An overview of the MHC class I antigen processing pathway. Cytosolic proteases digest antigenic proteins into fragments that predominantly contain the correct C-terminus of the final peptide and a variable number of N-terminal flanking residues. These fragments are proteolytic intermediates which are transported into the ER where they are trimmed and assembled into the final pMHC I. The pMHC I exit the ER and are expressed on the cell surface as potential ligands for the antigen receptor of a CD8 T cell.

The extra N-terminal residues are trimmed in the ER to generate the final pMHC I. The protease for this function is called ERAAP, the ER aminopeptidase associated with antigen processing in the mouse [8], or ERAP1 in the human [9]. For clarity, we refer to this enzyme as mouse or human ERAAP. The two enzymes share 86% identity, reside in the ER and are up-regulated by IFN-γ. Four groups independently generated ERAAP-deficient mice and confirmed that trimming of antigenic peptides by ERAAP in the ER is essential for generating a normal pMHC I repertoire [10–13]. In the absence of ERAAP, the overall expression of cell surface classical and non-classical MHC I molecules is reduced. Remarkably, individual peptides in the pMHC I repertoire are not uniformly affected. Many pMHC I are either completely lost or are dramatically increased while some pMHC I remain unchanged. Consequently the specificity and magnitude of CD8 T cell responses are profoundly altered.

Here we review the physiological consequences of ERAAP deficiency on the pMHC I repertoire. We begin with ERAAP’s essential role in generating a special sub-set of pMHC I followed by discussions of the mechanism of ERAAP function and its influence on the pMHC I repertoire in normal as well as virus infected cells.

Resolution of the “X-P” conundrum

In retrospect, the clearest indication that an ER protease(s) existed in the antigen processing pathway had come from the unusual properties of a set of “X-P” peptides presented by MHC I (X-P represents the first two amino acids of the MHC consensus motif; X=any amino acid, P=proline). Assessment of the preferred sequences for TAP binding and transport revealed a deleterious effect of a proline residue in the first (p1), second (p2) or third (p3) position of the peptide sequence [14,15]. Yet the database for peptides presented by MHC I shows that proline is the third most frequent p2 residue [16]. Indeed, approximately 20% of human MHC class I molecules present X-P peptides [17]. To explain this paradox, Van Endert and Neefjes groups hypothesized that instead of the final X-P peptides, the ER may actually be supplied with N-terminally extended peptides with the general structure Xn-P (n=2 or more residues), thereby relegating the inhibitory proline to a more distal position [14,15]. This reasoning predicted the existence of an ER protease for trimming the Xn-P precursors to the final X-P peptides.

These hypotheses were validated by the eventual identification of mouse as well as human ERAAP, which hydrolyzed the amino termini of all except X-P peptides [9,8,18]. It is likely that MHC class I molecules that present peptides with proline at p2 position co-evolved with ERAAP to take advantage of its ability to generate a unique pool of X-P peptides [19]. Given the inability of TAP to transport X-P peptides, the X-P motif could not exist without ER-trimming of Xn-P precursors by ERAAP.

The importance of trimming peptide precursors in the ER can now explain the striking effect of ERAAP deficiency on the mouse Ld MHC I [10]. The consensus sequence for Ld contains the X-P motif and compared to wild-type mice, the levels of Ld are dramatically reduced in ERAAP-deficient splenocytes. The impact of proline residues on ER trimming is also emphasized by the observation that a mutation that inserted a proline residue in the flanking region of a peptide presented by HLA-B57 is correlated with high viremia in human immunodeficiency virus infections [20]. The presence of the proline residue likely allowed the virus to escape detection by CD8 T cells because the pMHC I derived from the original virus was no longer presented.

ERAAP & family, the human case

How many aminopeptidases does it take to trim peptide precursors in the ER? In mice, ERAAP is the only known aminopeptidase that generates pMHC I and its absence cannot be compensated by other enzymes [10]. However, another ER aminopeptidase (termed L-RAP or ERAP2) with 51% identity with ERAAP was found in humans [21]. In vitro peptide trimming assays with recombinant ERAP2 showed that it had a substrate specificity distinct from ERAAP [22,23]. While human ERAAP preferred amino termini preceding large aliphatic residues such as leucine, ERAP2 showed a preference for basic residues such as arginine or lysine. This implies that both enzymes, either in tandem or as heterodimers, could trim the peptide precursors down to the final peptides [23]. Furthermore, the activity of human ERAAP in vitro was affected not only by the N- but also by the C-terminus of the substrate [22]. Accordingly, the Goldberg group proposed a “molecular ruler” mechanism by which ERAAP could trim its substrates down to a length of 8–9 residues which would be ideal cargo for loading MHC I. Why this stringent length selectivity is not observed with ERAP2 remains mysterious [22].

Remarkably, in our hands, mouse ERAAP did not follow the “molecular ruler” mechanism in vivo although it is almost identical to human ERAAP [24]. The ERAAP generated the final peptide in presence of the appropriate MHC I, but degraded the precursors in absence of MHC I. Furthermore, when ERAAP was inhibited, an extended precursor bound to mouse Ld MHC was detected as a potential reaction intermediate in cells. Thus, it is possible that ERAAP trims the antigenic precursors to the final peptide in the presence of MHC I molecules as a “template”. In this view, the MHC I molecules themselves serve as the “molecular ruler” rather than depend on the intrinsic property of ERAAP. Indeed, such a mechanism was originally proposed by Rammensee and colleagues in 1990 [25].

Comparable and compelling evidence for a significant role for ERAP2 in generating pMHC I is not yet available. For example, while the tissue distribution of ERAAP correlates with MHC I [8], that of ERAP2, at least at the level of mRNA transcripts, does not match MHC I [21], posing a potential problem for generating a diverse pMHC I repertoire in all cells. Likewise, in a screen of a large panel of tumor cells, surface MHC I expression correlated well with ERAAP, but not with ERAP2 activity, suggesting that most pMHC I required trimming primarily by ERAAP alone [26]. Yet another interesting correlation between polymorphisms in the human ERAAP gene and the autoimmune disorder, ankylosing spondylitis, has been recently discovered, although its underlying mechanisms are not yet known [27].

Downsizing peptides in the ER

Antigen processing begins in the cytoplasm where protein precursors are fragmented into proteolytic intermediates. The multicatalytic proteasome is the principal protease that carries out this initial step [4]. The extent to which other proteases are involved in cytosolic processing is less clear. For example, leucine aminopeptidase and bleomycin hydrolase were implicated in processing antigenic precursors in the cytoplasm [28,29]. However, mice lacking either the leucine aminopeptidase or bleomycin hydrolase do not appear to be deficient in pMHC I presentation [30,31] Likewise, the extent to which tripeptidyl peptidase II contributes to pMHC I remains unresolved [32–36].

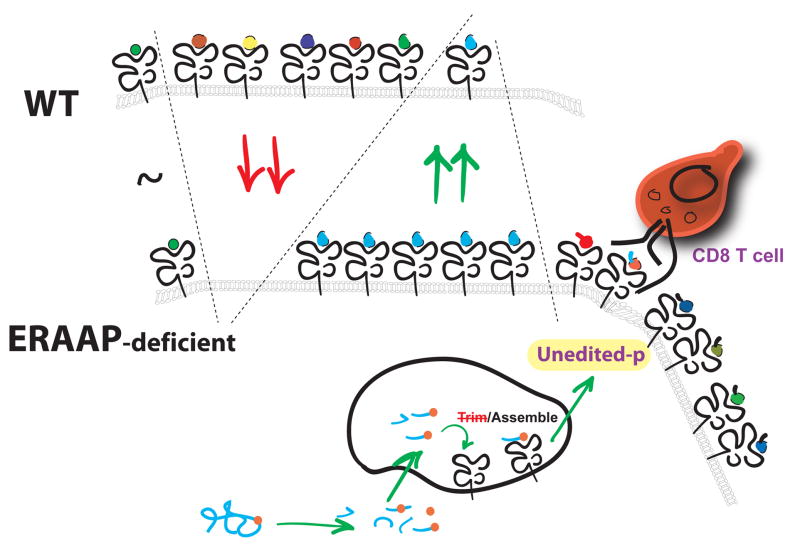

Regardless of the proteolytic mechanisms that fragment proteins in the cytoplasm, large numbers of N-terminally extended intermediates enter the ER and are further trimmed in this compartment. However, in the absence of ERAAP trimming, various pMHC I were differentially regulated [10,11]. Presentation of some endogenous peptides was undetectable, while others were increased dramatically (Fig 2). For example, the Y chromosome-encoded Uty peptide was not detected either on the cell surface or in HPLC fractionated cell extracts. On the other hand, the peptide encoded in the H13 minor histocompatibility gene was presented at a hundred fold higher level because ERAAP normally limits its generation. Curiously, a third set of pMHC I did not change in ERAAP-deficient cells, suggesting that some peptides do not require ER-trimming at all. Presumably these peptides were generated as such in the cytoplasm and transported into the ER without any extra N-terminal flanking residues.

Figure 2.

Schematic depiction of how the normally diverse pMHC I repertoire on the surface of cells from wild-type (WT) mice is profoundly disrupted in ERAAP-deficient mice. Some pMHC I are unchanged (~) compared to WT mice. Large number of other pMHC I are missing (↓) and expression of other pMHC I is dramatically enhanced (↑). In addition to these quantitative changes in the conventional pMHC I repertoire, ERAAP-deficient cells also express a significant number of “unedited” pMHC I. These novel pMHC I are not expressed in WT cells. The WT mice are thus not tolerant to these pMHC I and elicit a potent CD8 T cell response. The unedited pMHC I are likely to result from the lack of trimming in the ER where normal antigenic precursors arrive from the cytoplasm. Under normal conditions in WT mice, these precursors are trimmed and assembled with MHC I to yield pMHC I which exit the ER and reach the cell surface. In the absence of ERAAP-trimming (Trim), the MHC I may assemble only with the untrimmed precursors.

The ERAAP-dependent changes in pMHC I expression also influence CD8 T cell responses to endogenous antigens. In agreement with the requirement for ERAAP for presentation of the Uty and Smcy peptides, CD8 T cell responses to these pMHC I are impaired in ERAAP−/− animals [10,13]. Whether CD8 T cell responses are altered to the pMHC I which are enhanced in absence of ERAAP is not yet known. Furthermore, because changes in endogenous pMHC I expression are also expected to impact CD8 T cell repertoire selection in the thymus as well as its maintenance in the periphery [37,38], the causes for differences in the CD8 T cell responses remain to be explored.

Is “perfection” needed against viruses ?

The extent to which ERAAP trimming influences pMHC I and its effect on CD8 T cell responses has been examined in various murine viruses (Table 1). Mice were immunized with influenza, Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV) or Vaccinia Virus (VV) and their CD8 T cell responses were measured to immunodominant as well as subdominant pMHC I [11–13]. Compared to wild-type mice, the absence of ERAAP caused variable effects on the frequency of CD8 T cells detected by tetramer binding or production of IFN-γ. The CD8 T cell responses to certain virus-derived pMHC I were either reduced, enhanced or remained unchanged, similar to endogenous pMHC I discussed above. Although it is not yet clear to what extent differences in genetic backgrounds of the mice or in experimental parameters affect pMHC I presentation or the CD8 T cell responses, it is apparent that ERAAP deficiency does alter the epitope hierarchy.

Table 1.

Presentation of virus-derived pMHC I in the absence of ERAAP

| Virus | Precursor protein | Peptide/MHC I | Peptide sequence | pMHC I in absence of ERAAP | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCMV | Glycoprotein | GP 33–41/Db | KAVYNFATC | ~ | [13] |

| ↑ | [11] | ||||

| ~ | [12] | ||||

| GP 276–286/Db | SGVENPGGYCL | ~ | [13] | ||

| ↑* | [12] | ||||

| GP 34–41/Kb | AVYNFATC | ↓* | [12] | ||

| GP 118–125/Kb | ISHNFCNL | ↓* | [12] | ||

| Nucleoprotein | NP 396–404/Db | FQPQNGQFI | ↓ | [13] | |

| ↓* | [12] | ||||

| NP 205–212/Kb | YTVKYPNL | ↓* | [12] | ||

| Vaccinia-OVA | Ovalbumin | SL8/Kb | SIINFEKL | ~ | [13] |

| ~ | [12] | ||||

| Protein A47 | A47L138–146/Kb | AAFEFINSL | ↓ | [13] | |

| ↓ | [12] | ||||

| Protein K3 | K3L 6–15/Db | YSLPNAGDVI | ~ | [13] | |

| Profilin | A42R 88–96/Db | YAPVSPIVI | ~ | [13] | |

| Protein A19 | A19L 47–55/Kb | VSLDYINTM | ~ | [13] | |

| Protein B8 precursor | B8R 20–27/Kb | TSYKFESV | ~ | [13] | |

| ↑* | [12] | ||||

| Influenza A | Nucleoprotein | NP 366–374/Db | ASNENMETM | ~ | [13] |

| ↓ | [11] | ||||

| Polymerase acidic protein | PA 224–233/Db | SSLENFRAYV | ↑ | [13] | |

| ↓ | [11] | ||||

| Nuclear export protein | NS2 114–121/Kb | RTFSFQLI | ~ | [11] | |

| PB1-F2 protein | PB1F2 62–70/Db | LSLRNPILV | ~ | [11] | |

| Polymerase basic protein 2 | PB2 198–206/Kb | ISPLMVAYM | ↓ | [11] |

Presentation of indicated pMHC I is either reduced (↓), increased (↑) or remains unchanged (~).

= The authors considered the differences statistically significant.

Whether the observed changes in CD8 T cell responses in ERAAP-deficient mice reflect quantitative or qualitative changes in pMHC I expression is intriguing. In this context, it is remarkable that in addition to the quantitative changes in the conventional pMHC I repertoire, the ERAAP-deficient cells were found to express a qualitatively distinct set of “unedited” pMHC I [39] (Fig 2). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice elicited a vigorous CD8 T cell and an antibody response to novel pMHC I expressed by ERAAP−/− cells. These novel pMHC I arise only in the strict absence of ERAAP and are thus a unique manifestation of ERAAP-deficiency.

Is it possible that CD8 T cell responses to foreign pMHC I in ERAAP-deficient mice may be specific for unedited pMHC I? Because the assays used to assess CD8 T cell responses (target cell lysis, tetramer or intra-cellular IFN-γ staining) optimally detect known final pMHC I, CD8 T cells specific for longer unedited peptides may have been overlooked. For example, the frequency of CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ in response to the peptide NP396–404/Db complex in LCMV-infected mice is apparently reduced, but it is possible that N-terminally extended versions of this peptide might reveal other NP/Db specific CD8 T cells. The potential existence of such unedited pMHC I-specific CD8 T cells could explain the apparent paradox that despite profound loss of most conventional LCMV-specific CD8 T cells (Table 1), control of LCMV replication in ERAAP-deficient mice was comparable to wild-type mice [13]. We predict that CD8 T cell responses can be elicited towards unedited pMHC I derived from viral genes. However, the molecular characteristics of these unedited pMHC I and the physiological roles of CD8 T cells responses they elicit remain to be established.

Does size really matter ?

The presentation of long unedited pMHC I postulated to occur in absence of ERAAP can also occur in some normal circumstances. At least 5% of self peptides eluted from HLA-B1801 are over 10 residues in length [40], and peptides up to 14 or 15 amino acids are presented by HLA-B3501 [41] and mouse Ld [42]. Crystal structures of these unusually long peptides have shown that they reside in the peptide groove of the MHC I with either a protruding C-terminus [43], or by bulging in the middle [41]. Remarkably CTL can also recognize these unusual pMHC I structures, and responses to these can sometimes dominate the response to canonical versions of the same peptide [44]. To sense bulky peptides bound to MHC I, TCRs use distinct recognition strategies, such as “swiveling” on top of a rigid bulge, or “bull-dozing” the bulging residues [45,46].

Why do MHC I present unusually long peptides? Apparently the ER quality-control mechanisms are not perfect and allow some of these pMHC I to exit the ER and reach the cell surface. In ERAAP−/− cells, the MHC I have no choice but to cope with the extended precursors of the final peptides. Alternatively, in normal cells, long peptides may result from the inability of ERAAP to cleave X-P bonds on a subset of normal peptide precursors. Intriguingly, most of these long peptides contain the X-P motif which is indigestible by ERAAP [47]. Yet another possibility for all peptides, including those without the X-P motif, is that a high affinity for the MHC I molecule may protect the N-terminus from trimming by ERAAP [42]. The rules that govern presentation of these unedited peptides need to be defined.

Conclusions and perspectives

The pMHC I repertoire is clearly shaped by peptide-trimming in the ER. The ERAAP trims antigenic precursors to generate the normally perfect length of peptides required for presentation by MHC I. The loss of ERAAP-trimming changes not only the diversity and relative amounts of specific pMHC I, but also yields a novel set of unedited pMHC I, which likely represents the precursors of the final peptides available in the ER. The CD8 T cells in the normal repertoire can recognize and respond to these unedited pMHC I because these pMHC I are structurally distinct and thus foreign.

In the future we can expect to learn more on the mechanism of ERAAP function and the structural features of these unedited pMHC I. We also expect to gain a deeper understanding of how these unique pMHC I are recognized by CD8 TCRs and what their significance is in responses to microbial pathogens, tumors and even self-tissues in autoimmunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Nagarajan and T. Kanaseki for their critical reading and comments. NB is supported by an International Human Frontier Science Program fellowship. This research is supported by grants to NS from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Shastri N, Cardinaud S, Schwab SR, Serwold T, Kunisawa J. All the peptides that fit: the beginning, the middle, and the end of the MHC class I antigen-processing pathway. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:31–41. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falk K, Rotzschke O, Stevanovic S, Jung G, Rammensee H-G. Allele-specific motifs revealed by sequencing of self-peptides eluted from MHC molecules. Nature. 1991;351:290–296. doi: 10.1038/351290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madden DR. The three-dimensional structure of peptide-MHC complexes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:587–622. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Degradation of cell proteins and the generation of MHC class I-presented peptides. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:739–779. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cascio P, Hilton C, Kisselev AF, Rock KL, Goldberg AL. 26S proteasomes and immunoproteasomes produce mainly N-extended versions of an antigenic peptide. Embo Journal. 2001;V20:2357–2366. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunisawa J, Shastri N. The group II chaperonin TRiC protects proteolytic intermediates from degradation in the MHC class I antigen processing pathway. Mol Cell. 2003;12:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunisawa J, Shastri N. Hsp90alpha chaperones large proteolytic intermediates in the MHC class I antigen processing pathway. Immunity. 2006;24:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serwold T, Gonzalez F, Kim J, Jacob R, Shastri N. ERAAP customizes peptides for MHC class I molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature. 2002;419:480–483. doi: 10.1038/nature01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saric T, Chang SC, Hattori A, York IA, Markant S, Rock KL, Tsujimoto M, Goldberg AL. An IFN-g-induced aminopeptidase in the ER, ERAP1, trims precursors to MHC class I-presented peptides. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1169–1176. doi: 10.1038/ni859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••10.Hammer GE, Gonzalez F, Champsaur M, Cado D, Shastri N. The aminopeptidase ERAAP shapes the peptide repertoire displayed by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:103–112. doi: 10.1038/ni1286. Using ERAAP-deficient mice, this study demonstrates that loss of ERAAP alters the stability of pMHC I at the cell surface and globally disrupts the pMHC I repertoire. The authors carried out functional and biochemical assays that revealed the loss of ERAAP-dependent and the dramatic enhancement of other peptides normally destroyed by ERAAP. This study also provided compelling evidence that ERAAP functions in the ER compartment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••11.Yan J, Parekh VV, Mendez-Fernandez Y, Olivares-Villagomez D, Dragovic S, Hill T, Roopenian DC, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. In vivo role of ER-associated peptidase activity in tailoring peptides for presentation by MHC class Ia and class Ib molecules. J Exp Med. 2006;203:647–659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052271. The authors show that ERAAP deficiency in mice reduces expression of classical and nonclassical MHC class Ib molecules on the cell surface. They also noted the ERAAP-dependent changes in pMHC I expression. However, ERAAP-deficiency did not affect the positive selection of CD8 T cells in a TCR transgenic model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••12.York IA, Brehm MA, Zendzian S, Towne CF, Rock KL. Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1) trims MHC class I-presented peptides in vivo and plays an important role in immunodominance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9202–9207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603095103. Using models of virus infection in ERAAP-deficient mice, this study demonstrates that the immunodominance hierarchy among viral epitopes is perturbed in the absence of ERAAP. Furthermore the authors show that these differences do not merely result from an altered CD8 T cell repertoire. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••13.Firat E, Saveanu L, Aichele P, Staeheli P, Huai J, Gaedicke S, Nil A, Besin G, Kanzler B, van Endert P, et al. The role of endoplasmic reticulum-associated aminopeptidase 1 in immunity to infection and in cross-presentation. J Immunol. 2007;178:2241–2248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2241. Using ERAAP-deficient mice, the authors study various models of virus infection and cross-presentation. This study includes the striking finding that, although CD8 T cell responses towards LCMV epitopes were reduced, ERAAP−/− mice did not become more susceptible to LCMV infection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neisig A, Roelse J, Sijts AJAM, Ossendorp F, Feltkamp MCW, Kast WM, Melief CJM, Neefjes JJ. Major differences in transporter associated with antigen presentation (TAP)-dependent translocation of MHC class I-presentable peptides and the effect of flanking sequences. J Immunol. 1995;154:1273–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Endert PM, Riganelli D, Greco G, Fleischhauer K, Sidney J, Sette A, Bach JF. The peptide-binding motif for the human transporter associated with antigen processing. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1883–1895. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters B, Sidney J, Bourne P, Bui HH, Buus S, Doh G, Fleri W, Kronenberg M, Kubo R, Lund O, et al. The immune epitope database and analysis resource: from vision to blueprint. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, Bachor OA, Stevanovic S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.York IA, Chang SC, Saric T, Keys JA, Favreau JM, Goldberg AL, Rock KL. The ER aminopeptidase ERAP1 enhances or limits antigen presentation by trimming epitopes to 8–9 residues. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1177–1184. doi: 10.1038/ni860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serwold T, Gaw S, Shastri N. ER aminopeptidases generate a unique pool of peptides for MHC class I molecules. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:644–651. doi: 10.1038/89800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draenert R, Le Gall S, Pfafferott KJ, Leslie AJ, Chetty P, Brander C, Holmes EC, Chang SC, Feeney ME, Addo MM, et al. Immune selection for altered antigen processing leads to cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape in chronic HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2004;199:905–915. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanioka T, Hattori A, Masuda S, Nomura Y, Nakayama H, Mizutani S, Tsujimoto M. Human leukocyte-derived arginine aminopeptidase. The third member of the oxytocinase subfamily of aminopeptidases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32275–32283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •22.Chang SC, Momburg F, Bhutani N, Goldberg AL. The ER aminopeptidase, ERAP1, trims precursors to lengths of MHC class I peptides by a “molecular ruler” mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17107–17112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500721102. A large panel of synthetic peptides was used to decipher the substrate specificity of human ERAAP in vitro. The authors proposed the “molecular ruler” mechanism for explaining ERAAP function in antigen processing pathway. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saveanu L, Carroll O, Lindo V, Del Val M, Lopez D, Lepelletier Y, Greer F, Schomburg L, Fruci D, Niedermann G, et al. Concerted peptide trimming by human ERAP1 and ERAP2 aminopeptidase complexes in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:689–697. doi: 10.1038/ni1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •24.Kanaseki T, Blanchard N, Hammer GE, Gonzalez F, Shastri N. ERAAP synergizes with MHC I to make the final cut in the antigenic peptide precursors in the endoplasmic reticulum. Immunity. 2006;25:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.012. The fate of antigenic precusors and the final antigenic peptides was biochemically analyzed in vivo. The authors found a strong influence of the MHC I molecules in allowing ERAAP to generate the final pMHC I. The antigenic precursors were degraded by ERAAP in the absence of MHC I. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falk K, Rötzschke O, Rammensee HG. Cellular peptide composition governed by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 1990;348:248–251. doi: 10.1038/348248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fruci D, Ferracuti S, Limongi MZ, Cunsolo V, Giorda E, Fraioli R, Sibilio L, Carroll O, Hattori A, van Endert PM, et al. Expression of endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidases in EBV-B cell lines from healthy donors and in leukemia/lymphoma, carcinoma, and melanoma cell lines. J Immunol. 2006;176:4869–4879. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, Craddock N, Deloukas P, Duncanson A, Kwiatkowski DP, McCarthy MI, Ouwehand WH, Samani NJ, et al. Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beninga J, Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Interferon-gamma can stimulate post-proteasomal trimming of the N terminus of an antigenic peptide by inducing leucine aminopeptidase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18734–18742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoltze L, Schirle M, Schwarz G, Schroeter C, Thompson MW, Hersh LB, Kalbacher H, Stevanovic S, Rammensee H-G, Schild H. Two new proteases in the MHC class I processing pathway. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:413–418. doi: 10.1038/80852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Towne CF, York IA, Neijssen J, Karow ML, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Neefjes JJ, Rock KL. Leucine aminopeptidase is not essential for trimming peptides in the cytosol or generating epitopes for MHC class I antigen presentation. J Immunol. 2005;175:6605–6614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Towne CF, York IA, Watkin LB, Lazo JS, Rock KL. Analysis of the role of bleomycin hydrolase in antigen presentation and the generation of CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol. 2007;178:6923–6930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geier E, Pfeifer G, Wilm M, Lucchiari-Hartz M, Baumeister W, Eichmann K, Niedermann G. A giant protease with potential to substitute for some functions of the proteasome. Science. 1999;283:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seifert U, Maranon C, Shmueli A, Desoutter JF, Wesoloski L, Janek K, Henklein P, Diescher S, Andrieu M, de la Salle H, et al. An essential role for tripeptidyl peptidase in the generation of an MHC class I epitope. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:375–379. doi: 10.1038/ni905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reits E, Neijssen J, Herberts C, Benckhuijsen W, Janssen L, Drijfhout JW, Neefjes J. A major role for TPPII in trimming proteasomal degradation products for MHC class I antigen presentation. Immunity. 2004;20:495–506. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guil S, Rodriguez-Castro M, Aguilar F, Villasevil EM, Anton LC, Del Val M. Need for tripeptidyl-peptidase II in major histocompatibility complex class I viral antigen processing when proteasomes are detrimental. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39925–39934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.York IA, Bhutani N, Zendzian S, Goldberg AL, Rock KL. Tripeptidyl peptidase II is the major peptidase needed to trim long antigenic precursors, but is not required for most MHC class I antigen presentation. J Immunol. 2006;177:1434–1443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldrath AW, Bevan MJ. Selecting and maintaining a diverse T-cell repertoire. Nature. 1999;402:255–262. doi: 10.1038/46218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams MA, Bevan MJ. Effector and memory CTL differentiation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:171–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••39.Hammer GE, Gonzalez F, James E, Nolla H, Shastri N. In the absence of ERAAP the MHC class I molecules present many unstable and highly immunogenic peptides. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ni1409. Using reciprocal-immunizations of wild-type and ERAAP-deficient mice, the authors demonstrate that ERAAP-deficient cells present many unstable and structurally unique pMHC I complexes, which elicit potent CD8 T cell and B cell responses. The data strongly suggest that these unedited novel peptides are in fact N-terminally extended peptides. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hickman HD, Luis AD, Buchli R, Few SR, Sathiamurthy M, VanGundy RS, Giberson CF, Hildebrand WH. Toward a definition of self: proteomic evaluation of the class I peptide repertoire. J Immunol. 2004;172:2944–2952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Probst-Kepper M, Hecht HJ, Herrmann H, Janke V, Ocklenburg F, Klempnauer J, van den Eynde BJ, Weiss S. Conformational restraints and flexibility of 14-meric peptides in complex with HLA-B*3501. J Immunol. 2004;173:5610–5616. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •42.Samino Y, Lopez D, Guil S, Saveanu L, van Endert PM, Del Val M. A long N-terminal-extended nested set of abundant and antigenic major histocompatibility complex class I natural ligands from HIV envelope protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6358–6365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512263200. This paper focuses on peptides naturally processed from the HIV gp160 protein which are presented by mouse Ld MHC. The MHC I processing pathway gives rise to three major peptides (9, 10 and 15 residues) which are all presented by Ld at the surface and recognized by CD8 T cells. Surprisingly, the longer peptides seemed to be resistant to trimming by ERAAP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins EJ, Garboczi DN, Wiley DC. Three-dimensional structure of a peptide extending from one end of a class I MHC binding site. Nature. 1994;371:626–629. doi: 10.1038/371626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green KJ, Miles JJ, Tellam J, van Zuylen WJ, Connolly G, Burrows SR. Potent T cell response to a class I-binding 13-mer viral epitope and the influence of HLA micropolymorphism in controlling epitope length. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2510–2519. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tynan FE, Burrows SR, Buckle AM, Clements CS, Borg NA, Miles JJ, Beddoe T, Whisstock JC, Wilce MC, Silins SL, et al. T cell receptor recognition of a ‘super-bulged’ major histocompatibility complex class I-bound peptide. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1114–1122. doi: 10.1038/ni1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •46.Tynan FE, Reid HH, Kjer-Nielsen L, Miles JJ, Wilce MC, Kostenko L, Borg NA, Williamson NA, Beddoe T, Purcell AW, et al. A T cell receptor flattens a bulged antigenic peptide presented by a major histocompatibility complex class I molecule. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:268–276. doi: 10.1038/ni1432. This study shows how the TCR can recognize an unusually long peptide presented by MHC I. The TCR-MHC contacts essential for HLA-B3501 recognition, are maximized by “bull-dozing” the bulging residues in the MHC I bound peptide. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burrows SR, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. Have we cut ourselves too short in mapping CTL epitopes? Trends Immunol. 2006;27:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]