Abstract

Introduction

Although myelin autoimmunity is known to be a major factor in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS), the role of nonmyelin antigens is less clear. Given the complexity of this disease, it is possible that autoimmunity against nonmyelin antigens also has a pathogenic role. Autoantibodies against enolase and arrestin have previously been reported in MS patients. The T-cell response to these antigens, however, has not been established.

Methods

Thirty-five patients with MS were recruited, along with thirty-five healthy controls. T-cell proliferative responses against non-neuronal enolase, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), retinal arrestin, β-arrestin, and myelin basic protein were determined.

Results

MS patients had a greater prevalence of positive T-cell proliferative responses to NSE, retinal arrestin, and β-arrestin than healthy controls (p < 0.0001). The proliferative response against NSE, retinal arrestin, and β-arrestin correlated with the response against myelin basic protein (p ≤ 0.004). Furthermore, the proliferative response against retinal arrestin was correlated to β-arrestin (p < 0.0001), whereas there was no such correlation between non-neuronal enolase and NSE (p = 0.23).

Discussion

There is accumulating evidence to suggest that the pathogenesis of MS involves more than just myelin autoimmunity/destruction. Autoimmunity against nonmyelin antigens may be a component of this myriad of immunopathological events. NSE, retinal arrestin, and β-arrestin are novel nonmyelin autoantigens that deserve further investigation in this respect. Autoimmunity against these antigens may be linked to neurodegeneration, defective remyelination, and predisposition to uveitis in multiple sclerosis. Further investigation of the role of these antigens in MS is warranted.

Keywords: Enolase, arrestin, multiple sclerosis (MS), T lymphocytes, autoimmunity

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has long been regarded as an autoimmune demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) mediated by T-cells reactive for myelin proteins. Recently, the pathogenic role of myelin autoantibodies has been appreciated as well (1). Several lines of evidence highlight the importance of myelin autoimmunity and T-cells in the pathogenesis of MS. Studies using the well-accepted model of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), which can be actively induced by immunization with myelin components, have shown that EAE can be passively transferred by activated myelin-specific T-cells (2). Furthermore, T-cell reactivity against various myelin antigens (myelin basic protein, proteolipid protein, and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) has been demonstrated in MS patients (3). While the role of myelin autoantigens in the pathogenesis of MS is well researched and well established, the potential role of nonmyelin CNS antigens is less researched and less understood.

Transaldolase (TAL) is a key enzyme in the pentose phosphate pathway. High-affinity autoantibodies to recombinant TAL have been detected in serum (25/87) and cerebrospinal fluid (15/20) of patients with MS, while TAL antibodies were absent in 145 normal individuals and patients with other autoimmune and neurological diseases (4). Increased proliferative T-cell responses to recombinant TAL has been reported in MS patients, and this response has been shown to be more pronounced than that obtained by stimulation with MBP (4, 5). Enolase is another metabolic enzyme which is potentially interesting in the context of MS. Antibodies against non-neuronal enolase (NNE) have been described in various autoimmune diseases, where they are believed to have a pathological role (6, 7). Autoantibodies against NNE have also been implicated as a cause of autoimmune retinopathy (8–10). We, and others have reported the presence of anti-NNE antibodies in association with retinopathy in MS patients (11, 12). Furthermore, we have reported an increased prevalence of enolase autoantibodies in MS patients compared to healthy controls (13). Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) is the enolase isoform found in the CNS. Although cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of NSE in MS patients have been investigated as a potential biomarker in MS, no clear difference in the level of this protein has been observed in MS patients compared to healthy controls (14, 15). To date, the T-cell response to NNE/NSE in MS patients has not been investigated.

S100β is a calcium-binding protein that is expressed predominantly in astrocytes, but can additionally be found in other cells such as Muller cells of the retina (16–18). This protein has been found in CSF of 13 out of 18 patients with MS, whereas it was undetectable in any of the 11 control patients (19). CSF studies have also found that there is a significant trend for increasing S100β levels from primary progressive (PP) to secondary progressive (SP) to relapsing remitting (RR) MS, and that S100β was significantly higher in RR MS than in control patients, demonstrating that S100β is a good marker for the relapsing phase of the disease (20). S100β immunization and S100β-specific T-cell adoptive transfer can induce EAE and uveoretinitis in the Lewis rat, demonstrating that nonmyelin antigens can have an immunopathogenic role in inflammatory CNS disease (21, 22). Analogous to S100β, arrestin is also a calcium-binding protein that is found in the brain (β-arrestin) and retina (23–25). It is well known that MS is associated with intermediate uveitis (26–28) and arrestin can be used to induce experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis (EAU) (29–31). Autoantibodies to both brain and retina arrestin have been reported in MS patients (11, 32, 33), although the T-cell proliferative response to this antigen has not been reported.

The purpose of this study was to further explore T-cell autoreactivity against nonmyelin CNS antigens in MS. Based on the reasoning above, we chose to study both enolase and arrestin in this context. T-cell proliferation against different isoforms of these proteins was determined and compared to myelin basic protein (MBP), which is the most extensively studied candidate autoantigen in MS (3).

Methods

Patients and Controls

Approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Board, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Canada. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls. Thirty-five patients with clinically definite MS (CDMS) were recruited from the ambulatory MS clinic. All patients were newly diagnosed and were not taking any immunomodulatory therapy. For controls, we recruited 35 healthy age- and sex-matched volunteers. Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores and classification of MS (RR, SP, or PP) was performed by a neurologist specializing in MS (POC). A summary of the patient and control characteristics is displayed in Table I. All of the MS patients had EDSS scores less than 4.

Table I.

Characteristics of Patients and Controls

| Mean age | Sex ratio (F:M) | MS type (RR, SP, PP) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 42 ± 10 | 1.7:1 | (77%, 20%, 3%) |

| Controls | 39 ± 13 | 2.2:1 | – |

Note. Age is represented as ±SD.

Antigens/Reagents

NNE purified from human brain was commercially purchased (HyTest, Turku, Finland). Human recombinant NSE was a gift from Dr. P. Farrell (Nanogen, Toronto, Canada). Human recombinant retinal arrestin was prepared as previously described (34). β-arrestin purified from bovine brain was a gift from Dr. J. Benovic (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA). MBP purified from human brain was a gift from Dr. M. Moscarello (Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was commercially purchased (Calbiochem, San Diego, USA).

T-cell Proliferation Assays

The T cell assays used in this study have been extensively used and validated in previous studies (35–37). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients and controls were purified on Ficoll-Paque™ PLUS gradients (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and cultured in 96-well flat-bottom MICROTEST™ plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, USA) at a density of 105 cells/well (after trypan blue exclusion) in the presence of various amounts of test antigen (0.01–5 μg). The medium used was Serum-free and Protein-free Hybridoma Medium (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) supplemented with human recombinant IL-2 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, USA). Cells were grown in an incubator (37°C/5% CO2) for 6 days, after which 1 μCi3H-thymidine (6.7 Ci/mmol) was added. Following an overnight incubation, cells were harvested and counted using a Beckman Coulter™ LS 6500 scintillation counter. Data are represented as stimulation index (SI), which is defined as the counts per minute (cpm) obtained from PBMCs incubated with test antigen divided by the cpm of PBMCs alone. All experiments were done in duplicate, and personnel performing the experiments were blind to the identity of the samples.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Antigen dose-response curves were produced by log transforming the antigen dose (x-axis) and normalizing the SI values (y-axis) to define 0% and 100% as the smallest and highest values, respectively. Fischer's exact test was used to compare SI's between patients and controls, with SI's ≥1.5 representing a positive response and SI's < 1.5 representing a negative response. Because of multiple comparisons, statistical significance was set at 1%. Linear regression was used to compare the SI's of various test antigens with each other.

Results

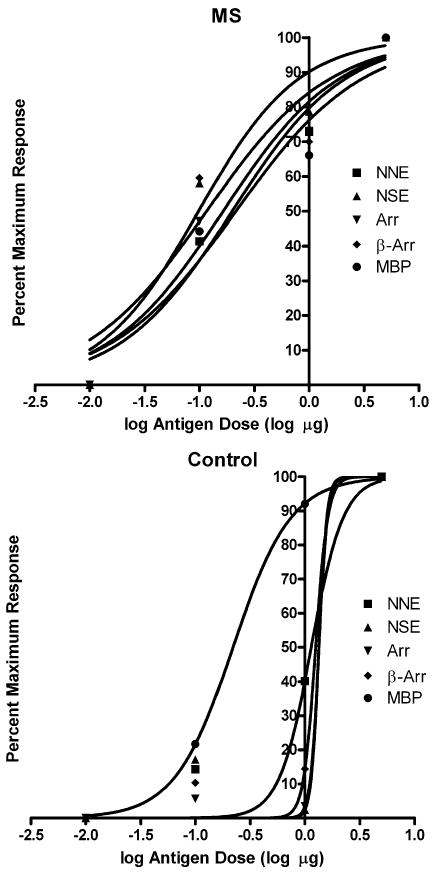

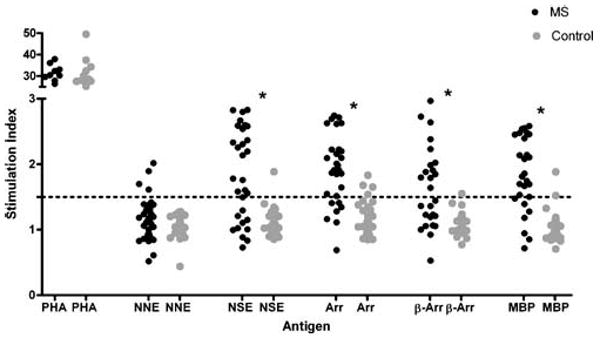

Dose-response curves (Fig. 1) of tested antigens at various doses demonstrated that at doses including and exceeding 1 μg, lymphocytes from healthy controls began showing proliferative responses. Based on the dose-response curve, we chose 0.1 μg as our antigen dose for further analysis in order to minimize the effects of nonspecific interactions and/or endotoxin in the preparations. The results of our T-cell proliferation assays are summarized in Fig. 2. T-cell proliferative responses to the mitogen PHA in patients and controls were similar, indicating a similar proliferative capacity in both samples. The prevalence of positive responses against MBP, NSE, retinal arrestin, and β-arrestin was significantly higher (p < 0.0001) in MS patients and controls. The prevalence of positive responses against NNE, however, did not differ significantly between MS patients and controls (p = 0.11).

Fig. 1.

Dose-response curves of various antigens in MS patients and controls. At doses including and exceeding the third data point (1 μg), lymphocytes from healthy controls began showing proliferative responses. Based on the dose-response curve, we chose the second dose point (0.1 μg) as our antigen dose for further analysis. NNE = non-neuronal enolase, NSE = neuron-specific enolase, Arr = retinal arrestin, β-Arr = β-arrestin, and MBP = myelin basic protein.

Fig. 2.

T-cell proliferative responses to various test antigens. Results are expressed as SI. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) response was determined at 5 μg, and all antigens were tested at 0.1 μg. Horizontal dashed line represents SI ≥ 1.5, the cutoff for a positive response. NNE = non-neuronal enolase, NSE = neuron-specific enolase; Arr = retinal arrestin, β-Arr = β-arrestin, and MBP = myelin basic protein; * =p < 0.0001.

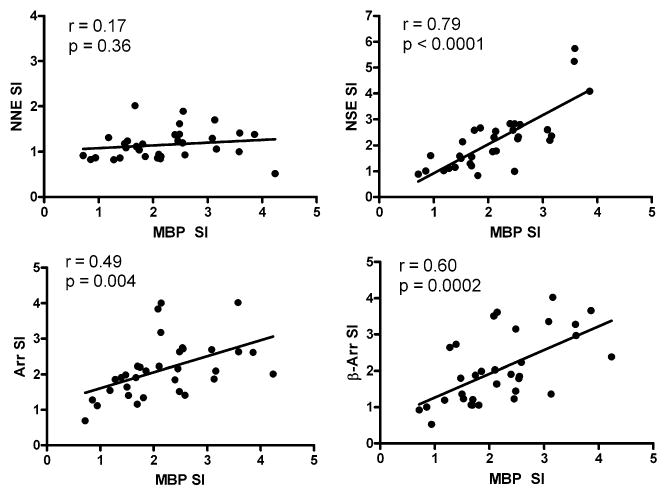

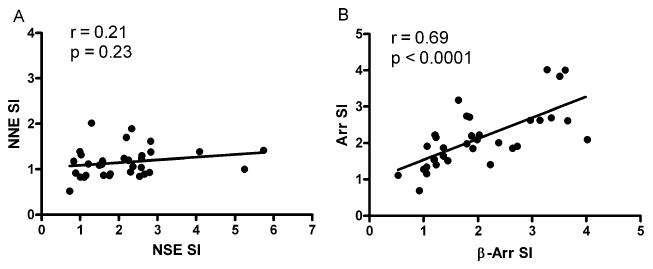

When T-cell proliferative responses of nonmyelin antigens were compared against those of MBP, we found that the response to NSE, retinal arrestin, and β-arrestin correlated positively with that of MBP (p ≤ 0.004, Fig. 3). We did not find a correlation between the proliferative response against NNE when compared to MBP (p = 0.36). There was a strong correlation between T-cell proliferative responses of retinal arrestin and β-arrestin (p < 0.0001, Fig. 4), whereas there was no such correlation between non-neuronal enolase and neuron-specific enolase (p = 0.23).

Fig. 3.

Correlation of T-cell proliferative responses to various test antigens (0.1 μg). Stimulation indexes (SI) for non-neuronal enolase (NNE), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), retinal arrestin (Arr), and β-arrestin (β-Arr) were compared to myelin basic protein (MBP). Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is shown, along with its p value.

Fig. 4.

Correlation of T-cell proliferative responses to various test antigens (0.1 μg). (A) Stimulation indexes (SI) for non-neuronal enolase (NNE) were compared against neuron-specific enolase (NSE). (B) Stimulation indexes (SI) for retinal arrestin (Arr) were correlated with β-arrestin (β-Arr). Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is shown, along with its p value.

Discussion

We have reported increased prevalence of positive proliferative responses of T-cells from MS patients compared to controls in response to three novel nonmyelin antigens: NSE, retinal arrestin, and β-arrestin. Although there was a higher prevalence of positive proliferative responses against NSE in MS patients compared to that in controls, we did not find any difference in proliferative responses against NNE. Enolase is a glycolytic enzyme (2-phospho-D-glycerate hydrolase), which exists in three isoforms: α-enolase or NNE, which is ubiquitous, β-enolase, which is predominant in muscle, and γ-enolase of NSE, which is found in neurons, paraneuronal cells, and neuroendocrine cells (38, 39). Recently, the important contribution of neurodegeneration to the pathogenesis of MS has been appreciated (40, 41). It is apparent that inflammatory and neurodegenerative factors are both involved in the pathology of MS (42). Patients with various systemic autoimmune diseases have been reported to have autoantibodies against α-enolase, but cross-reactivity with NSE in these diseases is rare (6). Neurons and glial cells (including oligodendrocytes) are known to express NSE (43, 44); so, it is not surprising to see higher autoreactivity against NSE compared to NNE in an autoimmune disease such as MS, which primarily affects the CNS.

Autoimmunity against NSE may be linked to the neurodegenerative component of MS. Examination of NSE levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients has not been promising in the search for a relevant biomarker of axonal degeneration (14, 15). A recent study examined serum levels of S100β and NSE in MS patients over a five-year period in order to find a marker for disease progression. Interestingly, although no correlation was found for serum S100β levels, a strong inverse relationship was found between serum NSE levels and disease progression (45). One explanation for this observation is that the lower serum NSE levels in MS patients with a progressive disease course and more severe disability reflect reduced metabolic activity secondary to axonal loss. Our patient cohort contained all newly diagnosed patients, therefore, we can assume that the mean level of disability in our cohort was less than that in the above-mentioned study. If serum NSE levels are a marker of axonal loss, then it is interesting to speculate the significance of T-cell reactivity against NSE. Perhaps NSE autoreactivity is high early in the disease (as we observed) because axonal/glial load is still high, but then the autoreactivity drops off as neuronal and glial mass decreases. A longitudinal study measuring NSE autoreactivity in MS patients is required, and warranted, to test this hypothesis.

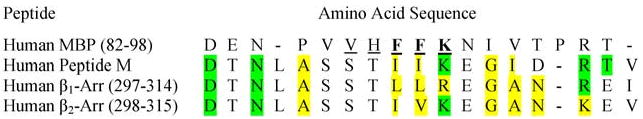

T-cell reactivity against arrestin may explain why MS patients are susceptible to intermediate uveitis. We observed similar T-cell responses to arrestins and MBP in MS patients. Both antigens had a higher prevalence of positive responses in MS patients compared to controls, and the reactivity against these antigens was correlated. MS is associated with uveitis (26–28), and arrestin is a principal autoantigen in uveitis (46, 47). The majority of HLA population studies in MS have focused on Caucasians of Northern European descent, where the predisposition to disease has been consistently associated with the HLA-DR15 haplotype (a subtype of HLA-DR2) (48). Intermediate uveitis has also been associated with the HLA-DR15 haplotype (49, 50). T-cell responses to the immunodominant epitope of retinal arrestin, peptide M, have been documented in several populations of uveitis patients (51–53). The immunodominant T-cell epitope of MBP has been localized to residues 82–98; this MBP peptide binds with high affinity to the disease-associated HLA-DR2 molecule, and is recognized by HLA-DR2-restricted T-cell clones from MS patients (54). Based on competitive binding studies, it has been demonstrated that important antibody epitopes, MHC and T-cell receptor (TCR) contact residues lie in this region (55). F89, F90, and K91 were key residues for autoantibody binding, while H88, F89, and K91 were primary contact residues for MBP-specific TCRs, and V87 and F90 were MHC anchor residues. When the amino acid sequence of MBP 82–98 is aligned with that of peptide M (Fig. 5), many important similarities are seen. The key residues for antibody, TCR and MHC binding (F89, F90, and K91), are either conserved or replaced with homologous amino acids between these residues. Furthermore, several other amino acids in the flanking regions are conserved or replaced by homologous residues. This similarity in immunodominant peptide sequences is likely one explanation for the observed association between MS and intermediate uveitis.

Fig. 5.

Amino acid sequences of immunodominant peptides in MBP and arrestins. The sequence of MBP 82–98 has been aligned with similar sequences in human arrestins (including peptide M of retinal arrestin). Identical amino acids are highlighted green, whereas homologous amino acids are highlighted in yellow. A dashed line indicates an empty space (no amino acid). Amino acids in bold are key residues for autoantibody binding, while underlined amino acids are important for binding to T-cell receptors and MHC molecules.

Autoreactivity against β-arrestin may partly explain the impaired remyelination and delayed oligodendrocyte development observed in MS. β-arrestin is a protein that is vital for signal transduction (56). It has been demonstrated that sonic hedgehog, a protein vital for oligodendrocyte development, is decreased in white matter of MS patients (57). Although the exact molecular mechanism is yet to be determined, it has been suggested that sonic hedgehog signaling may have a role in facilitating remyelination (58). Moreover, dysfunction of the Notch signaling pathway has been implicated in the limited remyelination in MS lesions (59, 60). In this context, it is interesting to note that β-arrestin is involved in both Notch and sonic hedgehog signaling (61–63). Alignment of the amino acids residues of the β-arrestins (25, 64) reveals a sequence that is homologous to the immunodominant epitopes of MBP and retinal arrestin (Fig. 5), suggesting that common epitopes may explain the similar T-cell responses to these antigens.

The T-cell response to NNE was not significantly different between patients and controls. In contrast, positive T-cell proliferative responses to NSE were more prevalent in MS patients and were highly correlated with MBP, suggesting that homologous epitopes are present in these molecules. Immunogenic epitopes within human NSE have not been characterized, making the search for a common epitope difficult. The α-subunit of NNE is 336 amino acids residues in length (65), whereas the γ-subunit of NSE is 434 amino acids long (66). The polypeptide sequences of these subunits align together with the first 98 residues of NSE being unique to that molecule. Our observations of contrasting antigenicity between NSE and NNE suggest that the immunodominant epitope of NSE lies within the first 98 amino acid residues of this molecule.

One plausible explanation for the evolution of antigenic diversity in MS may be epitope spreading, whereby the target of an immune response extends from the intended antigen to other epitopes present on the cell involved in the primary response. Epitope spreading, both within the same myelin molecule (intramolecular spread) as well as to different myelin molecules (intermolecular spread), has been documented well in several EAE models (67–71). Furthermore, spreading of immunodominant determinants has been reported in patients with uveitis (72). In patients with isolated monosymptomatic demyelinating syndromes (IMDS), a group of distinct clinical disorders with variable rates of progression to MS, differential autoreactive patterns to myelin peptides with epitope spreading have been demonstrated within patient subpopulations (73). The role of epitope spreading in CDMS, however, has not been established. Furthermore, epitope spreading between myelin and nonmyelin antigens has not been documented in EAE or MS. Based on our observations, we feel that epitope spreading between myelin and nonmyelin antigens in MS deserves further investigation.

Although once thought of almost exclusively as an autoimmune inflammatory disease against myelin antigens, it is becoming increasingly apparent that the pathogenesis of MS is far more complex. Recent evidence has shown that early axonal degeneration, oligodendrocyte apoptosis, impairment of remyelination, vascular changes, and instability of myelin proteins are all involved in the disease process (14, 42, 74, 75). Given this high degree of complexity, it is plausible that antigens other than those derived from myelin are involved in the immunopathology of MS. Autoimmunity against membrane-bound receptors and/or intracellular proteins involved in metabolism and signal transduction may be involved in a myriad of events which occur in the evolution of this disease. We have identified two novel antigens, enolase and arrestin, which are recognized as autoantigens by T-cells in MS patients. The T-lymphocyte proliferation against these nonmyelin antigens correlated with the response against MBP, a myelin protein that has a clear and established role in the pathogenesis of MS. Based on our observations and evidence in the literature, we believe that these novel nonmyelin antigens may indeed be contributing to the pathogenesis of MS and deserve further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the MS Scientific Foundation of Canada to FF and POC, a grant form the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to HMD, and grants from the National Eye Institute and the Karl Kirchgessner Foundation to WCS.

References

- 1.Ponomarenko NA, Durova OM, Vorobiev II, Belogurov AA, Telegin GB, Suchkov SV, et al. Catalytic activity of autoantibodies toward myelin basic protein correlates with the scores on the multiple sclerosis expanded disability status scale. Immunol Lett. 2006;103(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis: A pivotal role for the T cell in lesion development. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1991;17(4):265–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1991.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt S. Candidate autoantigens in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1999;5(3):147–160. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banki K, Colombo E, Sia F, Halladay D, Mattson DH, Tatum AH, et al. Oligodendrocyte-specific expression and autoantigenicity of transaldolase in multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 1994;180(5):1649–1663. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombo E, Banki K, Tatum AH, Daucher J, Ferrante P, Murray RS, et al. Comparative analysis of antibody and cell-mediated autoimmunity to transaldolase and myelin basic protein in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(6):1238–1250. doi: 10.1172/JCI119281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratesi F, Moscato S, Sabbatini A, Chimenti D, Bombardieri S, Migliorini P. Autoantibodies specific for alpha-enolase in systemic autoimmune disorders. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(1):109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gitlits VM, Toh BH, Sentry JW. Disease association, origin, and clinical relevance of autoantibodies to the glycolytic enzyme enolase. J Invest Med. 2001;49(2):138–145. doi: 10.2310/6650.2001.34040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamus G, Amundson D, Seigel GM, Machnicki M. Anti-enolase-alpha autoantibodies in cancer-associated retinopathy: Epitope mapping and cytotoxicity on retinal cells. J Autoimmun. 1998;11(6):671–677. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamus G, Aptsiauri N, Guy J, Heckenlively J, Flannery J, Hargrave PA. The occurrence of serum autoantibodies against enolase in cancer-associated retinopathy. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;78(2):120–129. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weleber RG, Watzke RC, Shults WT, Trzupek KM, Heckenlively JR, Egan RA, et al. Clinical and electrophysiologic characterization of paraneoplastic and autoimmune retinopathies associated with antienolase antibodies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(5):780–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorczyca WA, Ejma M, Witkowska D, Misiuk-Hojlo M, Kuropatwa M, Mulak M, et al. Retinal antigens are recognized by antibodies present in sera of patients with multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmic Res. 2004;36(2):120–123. doi: 10.1159/000076892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forooghian F, Kertes PJ, Aptsiauri N. Probable autoimmune retinopathy in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2003;38(7):593–597. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(03)80114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forooghian F, Adamus G, Sproule M, Westall C, O'Connor P. Enolase autoantibodies and retinal function in multiple sclerosis patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teunissen CE, Dijkstra C, Polman C. Biological markers in CSF and blood for axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(1):32–41. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00964-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaffaroni M. Biological indicators of the neurodegenerative phase of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(Suppl 5):S279–S282. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmer DB, Cornwall EH, Landar A, Song W. The S100 protein family: History, function, and expression. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37(4):417–429. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondo H, Iwanaga T, Nakajima T. An immunocytochemical study on the localization of S-100 protein in the retina of rats. Cell Tissue Res. 1983;231(3):527–532. doi: 10.1007/BF00218111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondo H, Takahashi H, Takahashi Y. Immunohistochemical study of S-100 protein in the postnatal development of Muller cells and astrocytes in the rat retina. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;238(3):503–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00219865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michetti F, Massaro A, Murazio M. The nervous system-specific S-100 antigen in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients. Neurosci Lett. 1979;11(2):171–175. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(79)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petzold A, Eikelenboom MJ, Gveric D, Keir G, Chapman M, Lazeron RH, et al. Markers for different glial cell responses in multiple sclerosis: Clinical and pathological correlations. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 7):1462–1473. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojima K, Berger T, Lassmann H, Hinze-Selch D, Zhang Y, Gehrmann J, et al. Experimental autoimmune panencephalitis and uveoretinitis transferred to the Lewis rat by T lymphocytes specific for the S100 beta molecule, a calcium binding protein of astroglia. J Exp Med. 1994;180(3):817–829. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kojima K, Wekerle H, Lassmann H, Berger T, Linington C. Induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by CD4+ T cells specific for an astrocyte protein, S100 beta. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1997;49:43–51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6844-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broekhuyse RM, Leunissen JL, Verkley AJ. Ultrastructural localization of S-antigen in retinal structures. Curr Eye Res. 1985;4(1):73–77. doi: 10.3109/02713688508999970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKechnie NM, Al-Mahdawi S, Dutton G, Forrester JV. Ultrastructural localization of retinal S antigen in the human retina. Exp Eye Res. 1986;42(5):479–487. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(86)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attramadal H, Arriza JL, Aoki C, Dawson TM, Codina J, Kwatra MM, et al. Beta-arrestin2, a novel member of the arrestin/beta-arrestin gene family. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(25):17882–17890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biousse V, Trichet C, Bloch-Michel E, Roullet E. Multiple sclerosis associated with uveitis in two large clinic-based series. Neurology. 1999;52(1):179–181. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham EM, Francis DA, Sanders MD, Rudge P. Ocular inflammatory changes in established multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52(12):1360–1363. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.12.1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagemans MA, Breebaart AC. Association between intermediate uveitis and multiple sclerosis. Dev Ophthalmol. 1992;23:99–105. doi: 10.1159/000429635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wacker WB, Donoso LA, Kalsow CM, Yankeelov JA, Jr, Organisciak DT. Experimental allergic uveitis. Isolation, characterization, and localization of a soluble uveitopathogenic antigen from bovine retina. J Immunol. 1977;119(6):1949–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nussenblatt RB, Kuwabara T, de Monasterio FM, Wacker WB. S-antigen uveitis in primates. A new model for human disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(6):1090–1092. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930011090021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Kozak Y, Sakai J, Thillaye B, Faure JP. S antigen-induced experimental autoimmune uveo-retinitis in rats. Curr Eye Res. 1981;1(6):327–337. doi: 10.3109/02713688108998359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sudo A, Endo M, Saitoh S. Serum anti-arrestin antibody and disease activity of multiple sclerosis—a case report of 4-year-old child. No To Hattatsu. 2000;32(5):415–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohguro H, Chiba S, Igarashi Y, Matsumoto H, Akino T, Palczewski K. Beta-arrestin and arrestin are recognized by autoantibodies in sera from multiple sclerosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(8):3241–3245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDowell JH, Smith WC, Miller RL, Popp MP, Arendt A, Abdulaeva G, et al. Sulfhydryl reactivity demonstrates different conformational states for arrestin, arrestin activated by a synthetic phosphopeptide, and constitutively active arrestin. Biochemistry. 1999;38(19):6119–6125. doi: 10.1021/bi990175p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winer S, Tsui H, Lau A, Song A, Li X, Cheung RK, et al. Autoimmune islet destruction in spontaneous type 1 diabetes is not beta-cell exclusive. Nat Med. 2003;9(2):198–205. doi: 10.1038/nm818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winer S, Astsaturov I, Cheung RK, Schrade K, Gunaratnam L, Wood DD, et al. T cells of multiple sclerosis patients target a common environmental peptide that causes encephalitis in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166(7):4751–4756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dosch H, Cheung RK, Karges W, Pietropaolo M, Becker DJ. Persistent T cell anergy in human type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 1999;163(12):6933–6940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McAleese SM, Dunbar B, Fothergill JE, Hinks LJ, Day IN. Complete amino acid sequence of the neurone-specific gamma isozyme of enolase (NSE) from human brain and comparison with the non-neuronal alpha form (NNE) Eur J Biochem. 1988;178(2):413–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser E, Kuzmits R, Pregant P, Burghuber O, Worofka W. Clinical biochemistry of neuron specific enolase. Clin Chim Acta. 1989;183(1):13–31. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(89)90268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grigoriadis N, Ben-Hur T, Karussis D, Milonas I. Axonal damage in multiple sclerosis: A complex issue in a complex disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2004;106(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chitnis T, Imitola J, Khoury SJ. Therapeutic strategies to prevent neurodegeneration and promote regeneration in multiple sclerosis. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2005;5(1):11–26. doi: 10.2174/1568008053174804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owens T. The enigma of multiple sclerosis: inflammation and neurodegeneration cause heterogeneous dysfunction and damage. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16(3):259–265. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000073925.19076.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deloulme JC, Helies A, Ledig M, Lucas M, Sensenbrenner M. A comparative study of the distribution of alpha- and gamma-enolase subunits in cultured rat neural cells and fibroblasts. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1997;15(2):183–194. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(96)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sensenbrenner M, Lucas M, Deloulme JC. Expression of two neuronal markers, growth-associated protein 43 and neuron-specific enolase, in rat glial cells. J Mol Med. 1997;75(9):653–663. doi: 10.1007/s001090050149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D, Teelken A, De Keyser J. Plasma S100beta and NSE levels and progression in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252(2):154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adamus G, Chan CC. Experimental autoimmune uveitides: multiple antigens, diverse diseases. Int Rev Immunol. 2002;21(2–3):209–229. doi: 10.1080/08830180212068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Smet MD, Chan CC. Regulation of ocular inflammation–what experimental and human studies have taught us. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20(6):761–797. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giordano M, D'Alfonso S, Momigliano-Richiardi P. Genetics of multiple sclerosis: linkage and association studies. Amer J Pharma-cogenomics. 2002;2(1):37–58. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200202010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raja SC, Jabs DA, Dunn JP, Fekrat S, Machan CH, Marsh MJ, et al. Pars planitis: Clinical features and class II HLA associations. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(3):594–599. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang WM, Pulido JS, Eckels DD, Han DP, Mieler WF, Pierce K. The association of HLA-DR15 and intermediate uveitis. Amer J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70994-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirose S, Singh VK, Donoso LA, Shinohara T, Kotake S, Tanaka T, et al. An 18-mer peptide derived from the retinal S antigen induces uveitis and pinealitis in primates. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;77(1):106–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Smet MD, Yamamoto JH, Mochizuki M, Gery I, Singh VK, Shinohara T, et al. Cellular immune responses of patients with uveitis to retinal antigens and their fragments. Amer J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(2):135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76981-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nityanand S, Singh VK, Shinohara T, Paul AK, Singh V, Agarwal PK, et al. Cellular immune response of patients with uveitis to peptide M, a retinal S-antigen fragment. J Clin Immunol. 1993;13(5):352–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00920244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pette M, Fujita K, Wilkinson D, Altmann DM, Trowsdale J, Giegerich G, et al. Myelin autoreactivity in multiple sclerosis: recognition of myelin basic protein in the context of HLA-DR2 products by T lymphocytes of multiple-sclerosis patients and healthy donors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(20):7968–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wucherpfennig KW, Catz I, Hausmann S, Strominger JL, Steinman L, Warren KG. Recognition of the immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide by autoantibodies and HLA-DR2-restricted T cell clones from multiple sclerosis patients. Identity of key contact residues in the B-cell and T-cell epitopes. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(5):1114–1122. doi: 10.1172/JCI119622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins. Science. 2005;308(5721):512–517. doi: 10.1126/science.1109237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mastronardi FG, daCruz LA, Wang H, Boggs J, Moscarello MA. The amount of sonic hedgehog in multiple sclerosis white matter is decreased and cleavage to the signaling peptide is deficient. Mult Scler. 2003;9(4):362–371. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms924oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seifert T, Bauer J, Weissert R, Fazekas F, Storch MK. Differential expression of sonic hedgehog immunoreactivity during lesion evolution in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(5):404–411. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.5.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.John GR, Shankar SL, Shafit-Zagardo B, Massimi A, Lee SC, Raine CS, et al. Multiple sclerosis: re-expression of a developmental pathway that restricts oligodendrocyte maturation. Nat Med. 2002;8(10):1115–1521. doi: 10.1038/nm781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jurynczyk M, Jurewicz A, Bielecki B, Raine CS, Selmaj K. Inhibition of Notch signaling enhances tissue repair in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;170(1–2):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mukherjee A, Veraksa A, Bauer A, Rosse C, Camonis J, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Regulation of Notch signalling by non-visual beta-arrestin. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1191–1201. doi: 10.1038/ncb1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalderon D. Hedgehog signaling: An Arrestin connection? Curr Biol. 2005;15(5):R175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Receptor regulation: beta-arrestin moves up a notch. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1159–1161. doi: 10.1038/ncb1205-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parruti G, Peracchia F, Sallese M, Ambrosini G, Masini M, Rotilio D, et al. Molecular analysis of human beta-arrestin-1: Cloning, tissue distribution, and regulation of expression. Identification of two isoforms generated by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(13):9753–9761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giallongo A, Oliva D, Cali L, Barba G, Barbieri G, Feo S. Structure of the human gene for alpha-enolase. Eur J Biochem. 1990;190(3):567–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oliva D, Cali L, Feo S, Giallongo A. Complete structure of the human gene encoding neuron-specific enolase. Genomics. 1991;10(1):157–165. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McMahon EJ, Bailey SL, Castenada CV, Waldner H, Miller SD. Epitope spreading initiates in the CNS in two mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2005;11(3):335–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klehmet J, Shive C, Guardia-Wolff R, Petersen I, Spack EG, Boehm BO, et al. T cell epitope spreading to myelin oligodendro-cyte glycoprotein in HLA-DR4 transgenic mice during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin Immunol. 2004;111(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lehmann PV, Forsthuber T, Miller A, Sercarz EE. Spreading of T-cell autoimmunity to cryptic determinants of an autoantigen. Nature. 1992;358(6382):155–157. doi: 10.1038/358155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McRae BL, Vanderlugt CL, Dal Canto MC, Miller SD. Functional evidence for epitope spreading in the relapsing pathology of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1995;182(1):75–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu M, Johnson JM, Tuohy VK. A predictable sequential determinant spreading cascade invariably accompanies progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: A basis for peptide-specific therapy after onset of clinical disease. J Exp Med. 1996;183(4):1777–1788. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Smet MD, Bitar G, Mainigi S, Nussenblatt RB. Human S-antigen determinant recognition in uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(13):3233–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tuohy VK, Yu M, Weinstock-Guttman B, Kinkel RP. Diversity and plasticity of self recognition during the development of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(7):1682–1690. doi: 10.1172/JCI119331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mastronardi FG, Moscarello MA. Molecules affecting myelin stability: A novel hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80(3):301–308. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Minagar A, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Alexander JS. Multiple sclerosis as a vascular disease. Neurol Res. 2006;28(3):230–235. doi: 10.1179/016164106X98080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]