Abstract

This study evaluated the extent to which counselors initiated informal discussions (i.e., general discussions and self-disclosures about matters unrelated to treatment) with their clients during treatment sessions within two National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trial Network protocols involving adaptations of motivational interviewing (MI). Sixty counselors across the two protocols had 736 sessions independently rated for counselor treatment fidelity and the occurrence of informal discussions. The results showed that 88% of the counselors initiated informal discussions in their sessions and that the majority of these discussions involved counselors sharing personal information or experiences they had in common with their clients. The major finding was that counselor training in MI was associated with significantly less informal discussion across sessions. A higher frequency of informal discussion was related to less counselor MI proficiency and less in-session change in client motivation, though unrelated to client program retention and substance use outcomes. The findings suggest that while some informal discussion may help build an alliance between counselors and clients, too much of it may hinder counselors' proficient implementation of MI treatment strategies and the clients' motivational enhancement process.

Keywords: self-disclosure, therapeutic alliance, motivational interviewing, treatment integrity, adherence and competence, substance abuse treatment

1. Introduction

Training counselors to adequately implement empirically supported substance abuse treatments has become a high priority within the addictions treatment field (Carroll & Rounsaville, 2007; Fixsen et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2006). The central aim of this training is to promote counselors' skilled use of therapeutic strategies and techniques consistent with the targeted treatment and to minimize or eliminate interventions that would undermine its implementation (Waltz et al., 1993). By achieving adequate proficiency, counselors presumably would be more likely to obtain the positive treatment outcomes found in the initial efficacy trials that established the treatment as evidence based. However, counselors may talk with clients about matters that are not related to the use of specific strategies consistent with a therapeutic approach or even relevant to the clients' treatment needs. These discussions may involve discussions about relatively neutral issues (e.g., the weather or current events) or counselor self-disclosures of personal information or experiences (e.g., health issues, vacation plans). We evaluated how often these informal discussions occur in substance abuse treatment sessions, how counselor training and characteristics influence the frequency in which counselors talk informally with their clients, and how informal discussions relate to treatment processes and outcomes.

Our interest in counselor-initiated informal discussions originated when we began to examine counselors' treatment adherence (i.e., the extent to which they deliver an intervention) and competence (i.e., the skill with which they implemented it) in two National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trial Network substance abuse outpatient treatment effectiveness protocols (Ball et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2006). One protocol incorporated a Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002) assessment into a standard one-session intake process within four community programs (Carroll et al., 2006). The other protocol examined the effectiveness of a three-session adaptation of the Motivational Enhancement Therapy manual used in Project MATCH (MET; Miller et al., 1992) in the first month of outpatient treatment within five community programs (Ball et al., 2007). Both protocols involved careful independent evaluation of the counselors' implementation of MI or counseling-as-usual (CAU) practices (Martino et al., 2008). Pilot testing of the 30 items detailing MI consistent, MI inconsistent, and general drug counseling strategies revealed that counselors sometimes made informal comments that were unrelated to their clients' substance abuse treatment and did not meet scoring criteria for any of the 30 items (we referred to these interactions as ‘chat’). We elected to add the independent assessment of informal discussion frequency across treatment conditions to our counselor fidelity rating system to better understand what actually occurs within drug treatment sessions (Miller, 2007). For example, recent analysis of CAU practices (Santa Ana et al., in press) has suggested that counselors talk informally in early treatment sessions more often than they use several standard drug counseling strategies (relapse prevention skill building, risk behavior reduction, treatment planning, case management).

The therapeutic value of informal discussion within sessions has been long debated as it has applied to counselor self-disclosures (Stricker, 2003). Linehan (1993) distinguishes between “self-involving” self-disclosures, in which counselors reveal their immediate personal reactions or related experiences to their clients, and “personal” self-disclosures, in which counselors give information about themselves to clients that may not necessarily relate to their treatment. The former type of self-disclosure is seen as potentially beneficial in that it helps counselors convey genuineness, authentic concern and share information with clients that may help them (Khantzian, Halliday, & McAuliffe, 1990). For example, Goldfried and colleagues (2003) note how counselors might tell clients what impact the clients make on them personally as a way to help the clients develop their interpersonal skills. In other circumstances, counselors might share with clients how they have encountered similar problems as a way to strengthen the therapeutic bond with clients, a key aspect of therapeutic alliance (Cecero et al., 2001). On the other hand, personal self-disclosures that are not immediately related to the clients' treatment are seen as potentially disruptive to treatment because they may not keep the therapeutic work focused on the clients' issues, appear insensitive or irrelevant, thereby undermining the therapeutic alliance, and poorly utilize the limited time most counselors have to work with clients (McDaniel et al., 2007).

Substance abuse treatment sessions may provide a particularly useful context for examining informal discussions between counselors and clients. Mallow (1998) notes how substance abuse treatment traditionally has been modeled on tenets from the Alcoholics Anonymous self-help movement in which individuals self-disclose their addiction, recovery, and related life experiences. This fellowship community holds that the sharing of personal experiences among people who have in common addiction problems creates a bond and sense of equality that enables members of AA to learn from each other and seek ongoing support to not drink or use drugs. Informal discussion as a means of affiliating and helping others, thus, is an essential part of the recovery process in self-help programs. This tradition has contributed to the common substance abuse treatment practice of counselors disclosing some aspects of their alcohol or drug use history to clients (Mallow, 1998), and it likely supports additional informal discussions in areas that are not necessarily directly related to the clients' treatment, though potentially relationship-building.

To date, the extent and nature of counselors' informal discussions with clients during substance abuse treatment sessions, factors related to its frequency, and the relationship of informal discussion to treatment processes and outcomes have not been examined. For example, the impact that training counselors in empirically supported treatments might have on the frequency in which counselors talk informally with clients is unclear and may vary among different approaches. MI hinges on the counselors' capacity to carefully attend to how clients talk about behavior change and to implement motivational enhancement interventions according to the relative balance of the clients' statements that support change or sustain current behavioral patterns (Miller & Moyers, 2007). While a little informal discussion might support a collaborative exchange between counselors and clients, too much of it might distract counselors from empathically grasping the clients' motivations and knowing how to proceed strategically in the session. Thus, counselors learning MI would be supervised to maximize opportunities wherein they elicit client statements that support change and skillfully handle change-sustaining ones, as well as reduce informal discussions that serve no motivational enhancement purposes. Alternatively, counselors oriented to use 12-Step interventions or those who are in recovery from alcohol or drug problems may be more likely to make self-disclosures than other counselors given the self-help traditions noted above.

To address these issues, we examine the extent to which community program counselors talked informally with their clients within the NIDA Clinical Trial Network MI protocols (Ball et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2006). First, we examine how often and what kinds of informal discussions occurred in the sessions. Second, we analyze how counselor training in MI differentially impacted the amount of informal discussion in sessions. We predict counselors who received MI training and supervision will have fewer informal discussions with clients than those who were not trained to deliver MI and continued to deliver CAU. Third, we examine counselor characteristics that might be associated with informal discussion. We hypothesize that counselors with either a 12-Step orientation or who are in recovery will have a higher frequency of informal discussions in their sessions than counselors who were not predominantly oriented in these ways. Finally, we examine the relationship between counselor-initiated informal discussion and therapeutic alliance, change in client motivation, and treatment outcomes. We hypothesize the associations between informal discussions and these variables will be negative.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview of the one- and three-session protocols

The one-session MI assessment intake and three-session MET protocols were implemented within nine outpatient community treatment programs that served diverse samples of substance users. Programs were located in California, Connecticut, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, and in rural, suburban, and urban settings. The protocols' client inclusion and exclusion criteria and description of client demographic and baseline substance use have been detailed in prior reports (Ball et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2006). The one-session protocol (Carroll et al., 2006) was designed for sites that typically offered a single assessment appointment followed by assignment to group counseling. Participants seeking outpatient substance abuse treatment at one of four study sites were randomized to either the initial intake/assessment session as typically conducted or a parallel single session in which MI techniques had been integrated. Sessions were 90 – 120 minutes in length. Following the single protocol session, participants then received standard treatment as practiced at that site. In the three-session protocol, participants seeking outpatient substance abuse treatment at one of five study sites were randomized to receive either three individual MET or CAU sessions, each 50-minute long and delivered during the first four weeks of treatment (Ball et al., 2007). Counselor training, inclusion/exclusion criteria and assessments were parallel in both protocols. In terms of outcomes, the one-session protocol resulted in significantly better 4-week client retention and reduced days of primary substance use in participants whose primary substance was alcohol rather than drugs (Carroll et al., 2006). The three-session MET and CAU conditions both reduced substance use at the end of the 4-week treatment phase. However, during the 12-week follow-up period, participants assigned to MET sustained reduced primary substance use, whereas those in CAU had significant increased use over this same phase (Ball et al., 2007).

2.2. Participants

A total of 76 counselors participated in the protocols. Forty-one counselors across four programs implemented the one-session protocol, and 35 counselors from the other five programs implemented the three-session protocol. In both protocols, counselors were randomized to deliver either the adapted MI interventions or CAU. Random assignment of counselors to intervention conditions was done to balance level of counselor skill, experience, and treatment allegiance across conditions. Counselors provided either written permission or informed consent for participation depending on local Institutional Review Board requirements.

2.3. Counselor Training

All counselors who delivered the MI interventions received a two-day, MI expert-led intensive workshop training followed by individually supervised practice cases until minimal protocol certification standards had been achieved in three sessions using a training version of an MI adherence and competence rating scale described below (i.e., at least half of the MI items rated average or above in terms of adherence and competence). After counselors were certified, they began to see randomized clients in the protocol and receive biweekly supervision from program-based supervisors similarly trained in MI and in how to supervise clinicians using methods commonly incorporated into clinical trials (Baer et al., 2007). CAU counselors did not receive any additional training or supervision beyond that which was already in place at each program (see Carroll et al., 2002) and the protocols did not assess the extent or nature of these CAU supervision encounters.

2.4. Assessments

2.4.1. Independent Tape Rating

Fifteen independent tape raters were trained to assess counselor adherence and competence using the Independent Tape Rater Scale (Martino et al., 2008). The scale included 30 items that address specific therapeutic strategies involving MI consistent interventions (e.g., reflective statements), MI inconsistent interventions (e.g., direct confrontation), and general substance abuse counseling interventions (e.g., assessing substance use) and one item that captured instances in which counselors spoke with clients about topics that were not related to the problems for which the client entered treatment or made self-disclosures unrelated to the counselors' personal recovery history (i.e., indicator of informal discussion). We excluded counselors' disclosures about their recovery history from this item because these disclosures typically are considered appropriate in general drug counseling (Mallow, 1998). The scale also included general ratings of the counselor (overall therapeutic skillfulness and ability to maintain a consistent structure/therapeutic approach) and assessment of the client's level of motivation at the beginning (first 5 minutes) and end of the session (last 5 minutes). Independent raters reviewed all available and audible one-session protocol tapes (n = 315) and a substantial subset (n = 425, 59%) of the three-session protocol tapes across conditions. Item definitions and rating decision guidelines were specified in a detailed rating manual (Ball et al., 2000b). For the 30 therapeutic strategy items, raters evaluated the counselors on two dimensions using a 7-point Likert scale. First, they rated the extent to which the counselor delivered the intervention (adherence; 1 = not at all, to 7 = extensively). Second, they rated the skill with which the counselor delivered the intervention (competence; 1 = very poor, to 7 = excellent). For example, a counselor may accurately reflect the implicit meaning of a client's statement (higher competency) or reflect with hesitation and tentativeness (lower competency). As another example, a counselor may directly confront a client in a clear, specific, and firm manner (higher competency) instead of being vague about what the client presumably should recognize (lower competency). The informal discussion item, general counselor, and client motivation items also were rated using 7-point Likert scales (low to high). Thus, informal discussion was measured only by the frequency of its use (adherence), not the competence in which it was rendered.

A random subset of 15 tapes was rated by all the independent raters to assess reliability. Intraclass correlation coefficient reliability estimates (ICC; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) indicated that 28 of 30 adherence items showed good to excellent reliability (ICCs ranged from .66 to .99) with only two items (skills training and psychodynamic interventions) having fair reliability (ICCs .55 and .57, respectively), most likely reflecting their relative infrequency across sessions. The ICC estimate for the informal discussion item was excellent (adherence = .95, competence = .95). Similarly, ICC estimates for the general ratings of the counselors and client motivation were good (all above .71). Furthermore, a confirmatory factor analysis supported a two-factor model for the MI consistent items (Martino et al., 2008): five items included fundamental MI skills that underpin the empathic and collaborative stance of MI such as use of open-ended questions, reflective statements, and MI style or spirit. The other five MI consistent items involved advanced MI skills for evoking client motivation and commitment to behavior change, such as heightening discrepancies and change planning.

Both MI inconsistent and general counseling interventions seldom occurred in sessions, though a few items in both categories occurred with sufficient frequency (i.e., on average at least once per session) across counselors to permit their use in statistical analyses, namely: MI inconsistent (3 items: unsolicited advice or direction giving, promotion of self-help group involvement, use of therapeutic authority) and general counseling (2 items: assessment of substance use, psychosocial assessment). Of these two sets of items, only the MI inconsistent items showed adequate internal consistency reliability (Chronbach's alpha = .84). Thus, the general drug counseling items were excluded from further analyses. We used the mean rating of MI consistent factors and of the three most frequently occurring MI inconsistent items, respectively, as an indicator of counselors' performance in these areas. A detailed description of the rater training process, psychometric analysis of the rating instrument, and treatment discrimination is provided in another report (Martino et al., 2008).

2.4.2. Assessment of Therapeutic Alliance

Therapeutic alliance was measured using the Penn Helping Alliance Rating Scale (Luborsky et al., 1983), a 10-item scale that assesses the extent to which the client experiences the counselor as warm, supportive, and helpful in working toward treatment goals. Both clients and counselors completed the scale after the first session in the one-session protocol and after the second session in the three-session protocol. The scale has good reliability and construct validity when used with substance abusing individuals (Cecero et al., 2001).

2.4.3. Assessment of Client Motivation, Retention, and Substance Use Outcomes

Change in client motivation was measured by subtracting motivation at the beginning of the session from motivation at the end session to obtain a change in motivation score (range = -6 to 6). Research assistants collected client retention data (days of program enrollment) based on self-reports and confirmed with client records. Detailed self-reports of drinking and drug use were collected via a Timeline Follow-back method (Fals-Stewart et al., 2000; Sobell and Sobell, 1992). Self-report accuracy was checked by comparing reports with contiguously collected urine and breath screens; these comparisons indicated high correspondence in both protocols (see Ball et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2006).

2.4.4. Counselor Treatment Orientation and Recovery Status

Counselors completed the Clinician and Supervisor Survey (Ball et al., 2002a) which evaluated a broad array of counselor characteristics (e.g., demographic, educational and professional experiences). Within this survey, counselors were asked to indicate the extent to which they adhered to different therapeutic orientations (12-step/disease model, cognitive-behavioral, motivational interviewing, and psychodynamic) along 5-point Likert scales (1 = no adherence, to 5 = strong adherence). Counselors were categorized as oriented toward these approaches if they rated their adherence at a 4 or 5 level. Counselors also indicated (yes, no) if they had a history of recovery from alcohol or drug problems.

2.5. Data Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and percentages were calculated to describe the frequency of informal discussions occurring within sessions. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine the association between informal discussion frequency and continuous measures of counselor characteristics (overall skillfulness, maintain therapeutic structure) and treatment process (therapeutic alliance, in-session change in client motivation) and outcomes (program retention, primary drug abstinence). ANOVAs were conducted to test for the hypothesized treatment group, orientation, and recovery status differences in informal discussion frequency.

3. Results

3.1. Counselor characteristics

A total of 736 sessions were recorded and rated (one-session protocol = 315; three-session protocol = 421).1 Sixty (79%; one session = 30, three-session = 30) of the 76 protocol counselors had rated sessions (several counselors had only one or two protocol cases). On average, each counselor had 12 rated sessions (sd = 9 in the sample; range = 1 - 36). Inaudible recordings, equipment failure, and non-submission of tapes accounted for the absence of rated sessions for every counselor. No significant counselor characteristic differences existed between counselors with and without rated sessions. Characteristics of the 60 counselors are presented in Table 1. They were predominantly female, Caucasian, and were on average about 40 years old. They had been employed at their agencies on average between 3-4 years and had similar mean years of substance abuse counseling experience, mean years of education completed, and proportion of master's degrees. Most degrees were in counseling professions (general or alcohol/drug), social work, or psychology. Approximately half the counselors reported being in personal recovery from prior substance abuse problems. Most counselors had no prior MI training exposure, and none had been trainers or therapists in research studies involving MI (Ball et al., 2002a).

Table 1.

Characteristics of counselors who initiated informal discussions in sessions by protocol

| One-session protocol N (%) | Three-session protocol N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, N (%) female | 18 (64.3) | 14 (60.9) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 23 (82.1) | 18 (78.3) |

| African American | 0 | 3 (13.0) |

| Hispanic | 3 (10.7) | 1 (4.3) |

| Native American | 1 (3.6) | 0 |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (3.6) | 1 (4.3) |

| Primary Treatment Orientation | ||

| 12-Step/disease model | 2 (7.1)) | 0 |

| Cognitive Behavioral | 1 (3.6) | 2 (8.7) |

| Motivational Interview | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| Psychodynamic | 0 | 0 |

| Mix of All Orientations | 10 (35.7) | 11 (47.8) |

| Highest Degree Completed | ||

| High School/associates | 4 (14.3) | 3 (13.0) |

| Associates | 6 (21.4) | 1 (4.3) |

| Bachelors | 5 (17.9) | 8 (34.8) |

| Masters | 13 (46.4) | 11 (47.8) |

| Hold drug and alcohol counselor license/certification | 21 (75.0) | 10 (43.5) |

| Self-report in recovery (n=42) | 14 (56.0) | 9 (52.9) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.36 (9.51) | 41.14 (11.93) |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 14.96 (5.24) | 15.0 (5.03) |

| Years employed at agency, mean (SD) | 3.61 (3.30) | 3.91 (4.49) |

| Years counseling experience, mean (SD) | 6.54 (4.23) | 8.78 (6.61) |

| Years held highest degree, mean (SD) | 8.27 (8.68) | 10.09 (8.95) |

Note: Nine counselors did not complete the Clinician and Supervisor Survey, reducing the sample for describing their characteristics to 51.

3.2. How often did informal discussions occur?

Informal discussions occurred in 42% of all sessions (i.e., a rating of 2 or more on the scale). Eighty-eight percent (n = 53) of the counselors talked informally with clients at least once in a session. On average these discussions occurred roughly once or twice per session (i.e., a mean ITRS scale score of 2.12, sd = 1.67). Sixty-eight percent (n = 41) of the counselors had informal discussions 3 or more times in at least one of their recorded sessions. Twelve counselors (20%) made informal comments in 75% or more of their sessions. Counselors in the one-session protocol, in comparison to those in the three-session, had informal discussions in a significantly higher proportion of sessions (51% vs. 35%; X2 = 18.84, p < .001) and with greater mean frequency per session (2.44 vs. 1.87; F(1, 734) = 21.55, p < .001), most likely due to the longer one-session protocol length. To put this in context, in both conditions in both protocols the interventions that occurred more often than informal discussion included several MI consistent techniques (open-ended questions, reflections) and assessment of substance use and psychosocial functioning. The interventions that occurred less frequently than informal discussion included several MI inconsistent strategies (emphasis on total abstinence or powerlessness over addiction, direct confrontation) or strategies involving treatment approaches from theoretical orientations other than MI (skills training, reality therapy, psychodynamic) (Martino et al., 2008).

To estimate what counselors informally talked about with clients, we randomly selected one tape in which informal discussions occurred from each of the 53 counselors who talked to clients in this manner. One hundred and sixty-one informal discussions were transcribed from these tapes and then categorized by the primary author (SM) and a research assistant until they reached agreement on all transcriptions. Table 2 presents the results of this assessment. Informal discussions were relatively brief and typically involved a momentary digression from the immediate assessment/treatment-related topic (see Table 3 for examples). Forty-nine percent of these instances involved counselors' self-disclosures of experiences they shared in common with clients. Most of them involved disclosures of personal information (28%) such as common interests (e.g., pets, vacation preferences), activities (e.g., exercise, shopping), background (e.g., ethnicity, past residences) or affiliations (e.g., religion, experiences with family and friends). Counselors also spoke about experiences in which family members, friends, or acquaintances had addiction problems (8%), or disclosed their own prior history of health problems (7%) or psychological and interpersonal difficulties (6%). In addition, counselors offered their unsolicited opinion (22%) about many different topics (e.g., the quality of restaurants, judgments about treatment providers). Counselors also informally discussed current events or news (9%). At other times, they disclosed their personal feelings toward their clients (7%), work-related problems or stressors (6%), or something about their professional background or history (3%). Some discussions (5%) were very idiosyncratic to counselors and defied categorization.

Table 2.

Categories of informal discussions in sessions

| Categories | Overall Occurrence N (%) | Counselors Involved N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Shared Experiences | ||

| Personal Information | 45 (28%) | 30 (50%) |

| Addiction Problems of Significant Others | 13 (8%) | 8 (13%) |

| Health Problems | 11 (7%) | 11 (18%) |

| Psychological/Interpersonal Problems | 10 (6%) | 6 (10%) |

| Opinions Not Related to Client's Treatment | 35 (22%) | 22 (37%) |

| Current Events or News | 14 (9%) | 14 (23%) |

| Personal Feelings about Client | 11 (7%) | 9 (15%) |

| Work-related Problems | 10 (6%) | 10 (17%) |

| Professional Background | 5 (3%) | 5 (8%) |

| Other | 8 (5%) | 5 (8%) |

Note: Categories were derived from a content assessment of the recorded counselor informal discussions transcribed from one session from each of the 53 counselors randomly selected from all of their respective sessions in which informal discourse occurred. The percentages represent the proportion of informal discussion that falls into each category (Overall Occurrence) relative to all informal discussions across counselors in the sample (n=161), as well as the proportion of total counselors who made informal discussions consistent with each category.

Table 3.

Informal discussion examples

| Categories | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Information | Client: I used to work in shipping and receiving operating a fork lift. | |

| Counselor: Really? My husband used to do the same kind of work. | ||

| Client: Yeah? | ||

| Counselor: He stopped working because of a back injury. He couldn't take the lifting and moving around and had to find different work. | ||

| Client. I'd like to find other work too. | ||

| Counselor: What would you like to do? | ||

| Addiction Problems of Significant Others | Counselor: Do you use methamphetamine? | |

| Client: No. I won't go near it. | ||

| Counselor: Good thing. I knew this guy who started using meth. Man, did his life go to hell quickly. He lost everything. I mean his wife, his house, his job. You wouldn't even recognize him today if you'd known him. Meth has become a huge problem. I've seen so many people taken down by it. | ||

| Client: Me too. | ||

| Counselor: How about marijuana? Do you smoke it? | ||

| Psychological/Interpersonal Problems | Client: [talks about his treatment history for Bipolar Disorder] | |

| Counselor: My experiences are with depression. At first I thought I was just tired, maybe working too much. But we all go through periods of feeling down. I tried to shrug it off, but couldn't. I realized I needed to talk to someone and get help. | ||

| Client: Well, I've been seeing my psychiatrist for several years and take medication. | ||

| Counselor: What are you taking? | ||

| Health Problems | Client: How much longer will this meeting be? | |

| Counselor: About 30 more minutes. | ||

| Client: Good, cause I have another appointment. | ||

| Counselor: I realize the paperwork takes a lot of time. The arthritis in my hands doesn't help things either. It makes it hard to write faster, so bear with me. We'll finish up as quickly as we can. | ||

| Client: Okay. | ||

| Opinions Not Related to Client's Treatment | Counselor: Do you have any children? | |

| Client: No. | ||

| Counselor: That's good. I've seen too many 18 year olds who have kids too early in their lives, before they are ready for the responsibility and when they still have a lot of problems they have to work out. | ||

| Client: Well, kids are not my problem. | ||

| Counselor: What do you think your main problems are right now? | ||

| Current Events or News | Client: I live over by Brookhaven Avenue. | |

| Counselor: Hey, isn't that near where that fire was at that factory last week? | ||

| Client: Mhm. It was about a mile away. | ||

| Counselor: I saw it in the paper. They think it was arson. That was a huge fire. Lucky no-one was killed. | ||

| Client: Yeah, you could see and smell it from where I lived. | ||

| Counselor: I know someone who is out of work because of the fire… a lot of people in fact. [after some silence] Are you currently living with anyone who drinks or uses drugs? | ||

| Personal Feelings about Client | Counselor: How old are you? | |

| Client: 42 years old. | ||

| Counselor: Oh, you look much younger than that. | ||

| Client: I guess the drugs have kept me younger. | ||

| Counselor: Well you must have really good genes. You're quite lucky. | ||

| Client: Thanks. [chuckles appreciatively] I think I'll keep coming here. | ||

| Work-related Problems | Client: Did you have a chance to send that form to my employer? | |

| Counselor: No, I haven't. I've been way behind with my paperwork and haven't been able to get to it yet. Sometimes I feel as if I spend more time completing paperwork than counseling people. I promise you I'll get to it by the end of the week. | ||

| Client: Alright. It's just that I can't return to work until you send in that form. | ||

| Counselor: I know. Why don't you tell that to my boss? I'll move it up on my list. | ||

| Professional Background | Client: I used to be a member of the Coast Guard. | |

| Counselor: Really? I was in the Navy for 10 years. I went right out of high school. It was a pretty good experience. | ||

| Client: Well I had a mixed experience. | ||

| Counselor: What I liked most about it was traveling all over the world. It opened my eyes to the way other people live. | ||

| Client: The Coast Guard wasn't like that. | ||

| Counselor: What was it like? | ||

Note: These examples are not verbatim transcriptions from the actual sessions. The information in them has been altered to broadly represent the informal discussion category and to protect the anonymity of the counselors and clients.

3.3. Did training in MI affect how often informal discussions occurred?

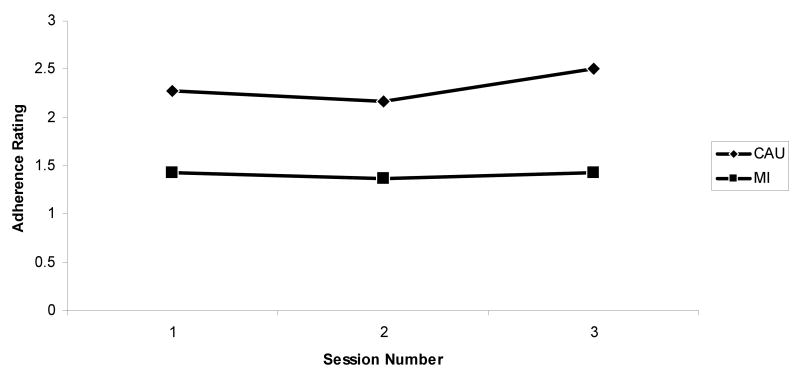

In both protocols, counselors trained in MI talked informally in significantly fewer sessions than counselor who delivered CAU without MI training (one-session = 42% vs. 60%, X2 = 10.28, p = .00; three-session = 22% vs. 48%; X2 = 31.25, p < .001). Similarly, in both protocols, MI-trained counselors talked informally significantly less often within sessions than counselors who implemented CAU without MI training (one-session = 2.08 vs. 2.79, F(1,313) = 12.27, p < .001; three-session = 1.41 vs. 2.31, F(1,419) = 41.37, p < .001). As shown in Figure 1, informal discussion was markedly lower in MI sessions and did not vary significantly by session number in the three-session protocol in either condition.

Figure 1.

Informal discussion item mean adherence ratings per session for CAU and MI counselors in the three-session protocol.

Examination of the correlation between the frequency of informal discussion and indices of the counselors' treatment integrity across conditions revealed that in both protocols informal discussion was negatively associated with adherence and competence to fundamental (one session protocol: r = -.20, p < .001, n = 315 for adherence and r = -.17, p < .001, n = 315 for competence; three-session protocol: r = -.18, p < .001, n = 419 for adherence and r = -.17, p < .001, n = 421 for competence) and advanced MI strategies (one session protocol: r = -.18, p < .001, n = 315 for adherence and r = -.18, p < .001, n = 315 for competence; three-session protocol: r = -.18, p < .001, n = 419 for adherence and r = -.18, p < .001, n = 421 for competence), positively associated with adherence to MI inconsistent strategies (one session protocol: r = .46, p < .001, n = 315; three-session protocol: r = .32, p < .001, n = 420), with no significant relationship to the competence with which counselors implemented MI inconsistent strategies.

3.4. Is counselor treatment orientation, recovery status, or overall therapeutic skillfulness associated with how often they have informal discussions?

Because of differences in informal discussion frequency secondary to MI training status, we used two-way ANOVAs with counselor treatment orientation (stated prior to training) and recovery status, respectively, study treatment condition, and their interaction as factors in these analyses. Counselor self-reported stronger orientation toward a 12-step/disease model, cognitive-behavioral therapy, MI, or psychodynamic treatments each did not differentially affect informal discussion frequency, nor did their recovery status make a significant difference in how much counselors talked in this way. No interactions between these variables and treatment condition were significant. In each ANOVA, only treatment condition significantly distinguished the counselors' informal discussion frequency, with less informal discussion occurring among counselors formally trained in MI (all ps ≤ .01). In contrast, in both protocols informal discussion frequency was negatively associated with the counselors overall therapeutic skillfulness (one session protocol: r = -.30, p < .001, n = 315; three-session protocol: r = -.25, p < .001, n = 421) and ability to maintain a consistent therapeutic structure during the session (one session protocol: r = -.30, p < .001, n = 315; three-session protocol: r = -.29, p < .001, n = 421). Exploratory analyses with the other counselor characteristic listed in Table 1 revealed no other significant main effects, interactions, or associations with the extent of informal discussion.

3.5. What is the relationship between informal discussion and therapeutic alliance, client motivation, and treatment outcomes?

The frequency of informal discussion was modestly but positively related to both counselor (r = .12, p = .02, n = 411) and client (r = .21, p < .001, n = 409) therapeutic alliance ratings in the three-session protocol. No significant associations with alliance occurred in the one-session protocol. Informal discussion frequency was negatively associated with in-session change in client motivation to reduce or stop using drugs and alcohol in both protocols (one-session protocol: r = -.17, p < .001, n = 315; three-session protocol: r = -.16, p < .001, n = 420). Informal discussion had no significant association with any of the protocols' primary outcome variables (days clients enrolled in treatment and percent days abstinent at both 4-week and 12-week follow-up points).

4. Discussion

Initial examination of counselor treatment fidelity in two large multisite trials comparing adaptations of MI to CAU revealed occasional discussions initiated by counselors that were unrelated to the clients' problems and treatment. To fully cover the range of counselors' behavior in sessions, we developed an item to tap this informal discussion and analyzed the extent to which it occurred, factors that influenced its expression, and its relationship to treatment process and outcomes. We found: 1) across study protocols and treatment conditions, the majority of counselors had informal discussions in one or more of their treatment sessions; 2) counselors who were trained in MI had significantly less informal discussions within and across sessions; 3) higher frequency of informal discussion was associated with less use of fundamental and advanced MI strategies and more use of strategies inconsistent with MI; 4) higher informal discussion frequency was associated with less counselor fundamental and advanced MI skill competence, global therapeutic skillfulness and ability to maintain session structure; 5) counselor treatment orientation, recovery status, or other counselor characteristics examined in this study were not associated with the frequency with which counselors talked informally with clients; and 6) informal discussion frequency was not significantly related to client treatment retention and substance use outcomes, however, it was positively associated with therapeutic alliance in the three-session protocol and, in both protocols, negatively associated with change in client motivation.

Informal discussions, as defined in this study, excluded counselors' self-disclosures of their past drug and alcohol use or recovery history. Thus, our finding that 88% of the counselors talked informally about subjects not related to the clients' treatment across 42% of the sessions was somewhat surprising. On the other hand, they only had informal discussions on average once or twice per session and, with few exceptions, these instances were relatively brief. Examination of the discussion content revealed that most of it involved counselors' self-disclosures of topics linked to the clients' experiences, perhaps as an attempt to develop a therapeutic bond with their clients during the early phase of substance abuse treatment. In fact, a higher frequency of informal discussion was associated with a stronger therapeutic alliance in the three-session protocol, but not the one-session protocol where it occurred in a higher proportion of sessions and with greater in-session frequency. It may be that a little informal discussion over a few sessions may develop the client's perception of the counselor as warm, genuine, and helpful, but that too much of it too soon in treatment (e.g., during the intake) may undermine this process and impede the counselors' motivational enhancement efforts.

The data offers some support for this notion. Informal discussion was more likely to occur when counselors were implementing MI strategies less often and with less skill and when they were using other strategies inconsistent with MI (unsolicited advice, therapeutic authority). Counselors rated as demonstrating less overall therapeutic skillfulness and maintenance of session structure also were rated as more likely to talk informally in sessions. Finally, increased levels of informal discussion were associated with smaller increases in client motivation to change substance use.

This study also suggests that training counselors in MI using workshops and follow-up clinical supervision may reduce how often counselors talk informally with their clients. Counselors in our protocols were randomly assigned to receive or not receive MI training and implement it with clients in the protocol. Across conditions, they had similar demographic, educational, professional characteristics, and treatment orientation allegiances at baseline, though pre-trial assessment of the counselors' informal discussions was not conducted and the structure and attention provided by workshop training and supervision was not controlled between conditions. Nevertheless, the significantly lower proportion of sessions (30% less in one-session protocol and 54% less in three-session protocol) in which informal discussions occurred among counselors trained in MI, in contrast to those who delivered CAU, indicate that carefully conducted training in MI may increase the counselors' focus on issues directly related to the clients' treatment and reduce the likelihood they will talk informally with clients in excess of what might be therapeutically beneficial to their clients. It is not clear, however, if counselor-initiated informal discussion would have the same relationship to the adherence and competence in which counselors implement other substance abuse treatments that may be less reliant on nuances in client language to mediate change as in MI. For example, approaches that focus on developing copings skills (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy) or building self-help recovery supports (e.g., twelve-step facilitation) may be less sensitive to the effect of informal discussion in that this type of discourse may not significantly impact the main mechanisms by which these approaches are presumed to work. It is equally unclear if simply having a coherent therapeutic framework that guides treatment implementation, regardless of approach, accounts for the counselors' less frequent informal discussions. Enhanced training and supervision in empirically supported treatments other than MI might similarly reduce counselor-initiated informal discussions in sessions.

This study failed to show a relationship between how much counselors' talked informally with clients and their self-reported primary adoption of a 12-step/disease model treatment approach. Similarly, the recovery status did not distinguish the amount of informal conversations occurring in sessions, nor did other counselor characteristics examined in this study. One explanation may be that the clinical demands early in treatment (agency intake, assessment and diagnostic formulation, and treatment planning) may have suppressed the counselors' inclination to initiate informal discussions differentially based on their characteristics. Counselors, regardless of their characteristics, had a lot to accomplish in the first few sessions, and informal discussions beyond the modest levels demonstrated in this study might have gotten in the way of treatment task completion. It is also possible that those oriented toward a 12-step approach or those in recovery were more likely to talk about their history of substance use than other counselors; however, these disclosures were excluded from our rating item. The extent to which counselor characteristics might distinguish the amount and type of informal discussion over a longer course of treatment requires future study.

The study also did not show a relationship between the frequency of informal discussion and the protocols' primary client treatment outcomes. Several reasons are possible. First, the amount of informal discussion in the sessions may have been insufficient to directly affect the clients' program attendance and substance use patterns or to influence with adequate strength important mediators such as motivation for change in MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) that might impact treatment outcomes. Second, different types of informal discussion may have occurred in the same session that impacted the therapeutic relationship and outcomes in opposite ways, thereby counteracting each other. In some cases, informal discussions seemed potentially useful in that it might have fostered a bond between the counselor and client (e.g., expressing positive opinions or compliments toward clients, sharing related experiences). In other cases, these discussions seemed distracting or unhelpful (e.g., discussing current events at length, discussing work-related problems with clients). Different types of informal discussion may have different impact on the clients' experience of treatment (Linehan, 1993). The independent raters in this study did not code the occurrences into subcategories that might have permitted a more detailed analysis of how informal discussion influences treatment process and outcomes. Finally, clients across conditions and protocols achieved high rates of retention and reduced primary substance use (Ball et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2006). This restricted range in the primary client outcomes likely limited the extent to which significant relationships between informal discussion and client outcomes could be found.

This study has additional limitations. The findings are limited to early treatment sessions and to community treatment programs and counselors who volunteered to participate in the CTN protocols. The generalizability of the findings to counselor behaviors in longer substance abuse treatments and in non-CTN treatment programs needs to be established. Also, the study did not include independent rating of baseline levels of counselor-initiated informal discussion or categories of it in the sessions. Moreover, the categories proposed in this study require further validation using more systematic qualitative research procedures. In addition, while the findings noted significant associations between informal discussion frequency and several treatment processes (treatment integrity measures, therapeutic alliance, client motivation), many correlations were small and may have reached statistical significance because of the large sample of tapes rated. The clinical significance of these findings requires further examination. Finally, the study did not include behavioral ratings of client statements during the sessions. Thus, this study did not determine how clients experienced instances when counselors talked informally with them or in what way clients may have prompted these in-session discussions.

Nonetheless, this study underscores how counselors occasionally make statements that are unrelated to their clients' immediate treatment needs and that sometimes these comments are of questionable therapeutic effect. Training and supervising counselors in empirically supported treatments such as MI based on direct observation of their work may help reduce the occurrence of informal discussion and improve the type and timing of such comments so that they facilitate rather than hinder the change process in substance abuse treatment.

Acknowledgments

National Institute on Drug Abuse grants (U10 DA13038, DA1025273, and K05-DA00457) supported this study. The authors are grateful to the individuals who helped develop the rating manual (Joanne Corvino, MSW, Jon Morgenstern, Ph.D.), the MI expert trainers and supervisors (Ken Bachrach, Ph.D., Jacqueline DeCarlo, Chris Farentinos, M.D., Melodie Keen, M.A., L.M.F.T., Tina Klem, LCSW, Terence McSherry, M.S.P.A., Jeanne Obert, M.S., Doug Polcin, Ed.D., Ned Snead, M.S., Richard Sockriter, M.S., M.B.A., Deborah Van Horn, Ph.D., Paulen Wrigley, R.N., M.S., Lucy Zammarelli, M.A, and Charlotte Chapman, Ph.D.), the independent tape raters (Luis Anez Nava, Psy.D., Theresa Babuscio, B.A., Declan Barry, Ph.D., Natalie Dumont, MSW, Lynn Ferrucci, M.A., Francis Giannini, LCSW, Rachel Hart, M.A., Karen Hunkele, B.A., Susan Kasserman, RN, M.Div., Brian Kiluk, B.A., Demetrios Kostas, LCSW, MBA, Mark Lawless, LCSW, Manuel Paris, Psy.D., Jane Stanton, LCSW, and Mary Ann Vail, LCSW), Julie Matthews, B.A., Brandi Buchas, B.A., and Monica Canning-Ball, MFA who administratively managed the tape rating project and transcribed chat occurrences, and to the counselors and clients who participated in both protocols. The rating scales described in this study are available from Dr. Martino.

Footnotes

Four three-session protocol sessions had missing values for the informal discussion item in the original full tape rating sample of 425 sessions, reducing the sample size to 421 in this report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baer JS, Ball SA, Campbell BK, Miele GM, Schoener EP, Tracy K. Training and fidelity monitoring of behavioral interventions in multi-site addictions research: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Bachrach K, DeCarlo J, Farentinos C, Keen M, McSherry T, Polcin D, Snead N, Sockriter R, Wrigley P, Zammarelli MA, Carroll KM. Characteristics, beliefs, and practices of community counselors trained to provide manual-guided therapy for substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002a;23:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Martino S, Corvino J, Morganstern J, Carroll KM. Independent tape rater guide. 2002b. Unpublished psychotherapy tape rating manual. [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Van Horn D, Crits-Christoph P, Woody GE, Obert JL, Farentinos C, Carroll KM. Site matters: Motivational enhancement therapy in community drug abuse clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:556–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, Kunkel L, Mikulich-Gilbertson S, Morgenstern J, Obert JL, Polcin D, Snead N, Woody GE. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Farentinos C, Ball SA, Crits-Christoph P, Libby B, Morgenstern J, Olbert JL, Polcin D, Woody GE, Clinical Trials Network MET meets the real world: design issues and clinical strategies in the Clinical Trials Network. Journal of Substance Abuse Research. 2002;23:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00255-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry R, Frankforter T, Nuro KF, Ball SA, Fenton LR, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating counselor adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57:225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. A vision of the next generation of behavioral therapies research in the addictions. Addiction. 2007;102:850–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecero JJ, Fenton LR, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. Focus on therapeutic alliance: The psychometric properties of six measures across three treatments. Psychotherapy. 2001;38:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI Publication #231) Tampa, FL: University of South Florida Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfried MR, Burckell LA, Eubanks-Carter C. Therapist self-disclosure in cognitive-behavior therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology/In Session. 2003;59:529–539. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ, Halliday KS, McAuliffe WE. Addiction and the vulnerable self: Modified dynamic group therapy for substance abusers. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L, Crits-Christoph P, Alexander L, Margolis M, Cohen M. Two helping alliance methods for predicting outcomes of psychotherapy: A counting signs vs. a global rating method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1983;171:480–492. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallow AJ. Reconciling psychoanalytic psychotherapy and alcoholics anonymous philosophy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:493–498. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TF, Carroll KM. Community program counselor adherence and competence in motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SH, Beckman HB, Morse DS, Silberman J, Seaburn DB, Epstein RM. Physician self-disclosure in primary care visits: Enough about you, what about me? Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1321–1326. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Bring addiction treatment out of the closet. Addiction. 2007;102:863. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Moyers T. Eight stages in learning motivational interviewing. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions. 2007;5:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sorensen JL, Selzer JA, Bringham GS. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: A review with suggestions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Motivational Enhancement Therapy manual: A clinical research guide for counselors treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence.(Volume 2, Project MATCH Monograph Series) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana EJ, Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. What is usual about ‘treatment-as-usual’? Data from two multisite effectiveness trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.01.003. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–429. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Humana Press; New Jersey: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stricker G. The many faces of self-disclosure. Journal of Clinical Psychology/In Session. 2003;59:623–630. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Addis ME, Koerner K, Jacobson NS. Testing the integrity of a psychotherapy protocol: assessment of adherence and competence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:620–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]