Abstract

Background

Parenting stress is associated with negative parenting practices, which have been linked to increased youth health risk behaviors. It is important, therefore, to understand the most salient contributors to parenting stress in families who live in communities considered at high risk of the development of youth problem behaviors.

Objective

On the basis of a model derived from the model of parenting stress of R. R. Abidin (1995), the contributions to parenting stress of child factors (age, social skills, and problem behaviors), parent factors (gender, health, and race or ethnicity), and contextual factors (family structure, conflict, social support, education, and income) were explored.

Methods

A secondary data analysis using bivariate correlations and multiple and hierarchical regression was conducted to identify the relative influence of these factors on parenting stress in a national sample of 824 parents (primarily mothers, those from racial or ethnic minorities, and those who have low income) of adolescents aged 10–18 years.

Results

Analyses indicated strong associations between child behavior and parenting stress (p < .001). There was a positive association between youth age and parenting stress. Single parents and parents in poor health reported significantly high levels of parenting stress; families with high levels of involvement and cohesion reported significantly less stress. The data support the multivariate model of parenting stress of R. R. Abidin (1995).

Discussion

Parents of adolescents experience a high level of parenting stress that can compromise their ability to parent effectively. Identification of child, parent, and contextual characteristics that are associated with parenting stress may facilitate our understanding of how healthcare, social service, and education providers can prepare and support parents to reduce the risk of problem behavior.

Keywords: adolescent, parenting, stress, psychological

Parents continue to be an important influence on the development of their adolescent children. However, parenting adolescents can be stressful, largely due to changes in the parent–child relationship as the child develops. Early adolescence (ages 10–15 years) is a particularly difficult period as closeness and time spent together decline (Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, & Duckett, 1996). Parents of adolescents experience higher levels of depression and anxiety, less satisfaction with parenting and life in general, lower self-esteem, and a lower belief in their own competence than do parents of younger children (Dekovic, 1999). These factors contribute to rising levels of parental stress. In addition, parents who live in high-risk communities face substantial challenges in raising their teenaged children. These parents, who are raising their adolescents within a context of poverty, experience compounded stress (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Henry, & Florsheim, 2000; Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, & Jones, 2001).

High levels of parenting stress are associated with negative parenting practices and insufficient monitoring and control (Crnic & Low, 2002), both of which are linked to increased risk of youth problem behaviors, such as substance abuse, violence, and sexual experimentation (Resnick et al., 1997). Identifying those child and parent characteristics or social contexts that are associated with the stress of parenting in high-risk environments would facilitate our understanding of how healthcare, social service, and education providers can prepare and support parents of adolescents to reduce the risk of deviant behavior.

Data were taken from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Mentoring and Family Strengthening Prevention Initiative (Bellamy, Springer, Sale, & Espiritu, 2004), a program that included a large and diverse national sample of families with adolescent children living in communities that were considered at high risk of development of youth problem behaviors because of high levels of crime and poverty. The aim of the SAMHSA study was to determine the efficacy of various family-focused model programs on improving family relationships and reducing youth problem behaviors. The programs were found to be effective in improving family functioning as measured by family resilience, family cohesion, family conflict, and family attachment (Matthew, Wang, Bellamy, & Copeland, 2005).

High levels of parenting stress are associated with negative parenting practices and insufficient monitoring and control (Crnic & Low, 2002)

The aims of this study were to (a) determine the correlates of parenting stress and how parenting stress varies across parent, child, and contextual domains and (b) determine the relationship of parental stress with single parenting; parental health status; and two indicators of family atmosphere, cohesion and involvement, by testing three hypotheses: Single parents experience greater parenting stress than do those who parent with a partner; parents with poor health report greater parenting stress than do those in better health; and parents who report a less cohesive family atmosphere and less involved parenting will have higher parenting stress than will those reporting a more cohesive atmosphere and more involved parenting.

Model

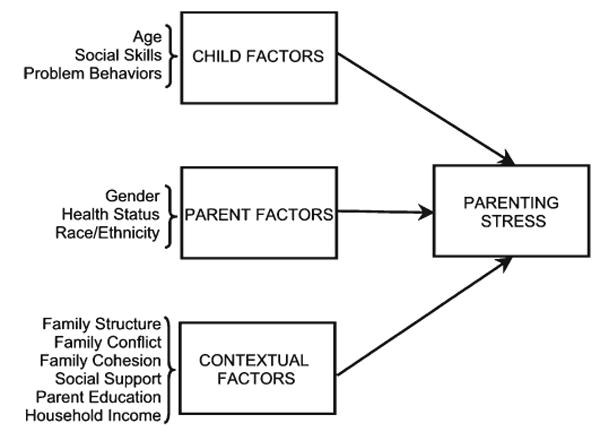

The model for this study, based on Abidin's (1995) Parenting Stress Index, is illustrated in Figure 1. The framework organizes multiple determinants of parenting stress into three domains. The first encompasses individual characteristics of the child, including age, social skills, and problem behaviors. The second domain focuses on parent characteristics, including gender, health status, and minority status. The third domain, contextual factors, includes internal family atmosphere factors of conflict, cohesion, involvement, and family structure and external social system factors of social support, parent education, and household income.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model of parenting stress (adapted from Abidin, 1995).

Child Factors

Age was included as a child characteristic variable in this study because parent–child conflict intensity and problem behavior trajectories have been reported to increase between early and middle adolescence (Ingoldsby et al., 2006). Child social skills and problem behavior variables were included because child behavior has been linked to parenting (Huh, Tristan, Wade, & Stice, 2006), harsh discipline (Pinderhughes, Dodge, Bates, Pettit, & Zelli, 2000), and living in poverty (Hoffman, 2006). Finally, the sample is drawn from communities considered to be at high risk of the development of youth problem behaviors.

Parent Factors

Parent health is included as a parent characteristic variable because it may be a critical component of parenting stress as stressful life events and physical health are correlated strongly (Tosevski & Milovancevic, 2006). There is some indication that poor physical health can lead to more family stress, which in turn may lead to less effective parenting (Steele, Forehand, & Armistead, 1997). Parent racial or ethnic status is an included variable because a parent's race or ethnicity has been found to be related to parenting practices and parental stress in African American families (Pinderhughes et al., 2000) and Latino families (Gorman-Smith et al., 2000). In addition, the effects of a disadvantaged environment on parenting and youth outcomes have been found to be influenced differentially by family race and ethnicity (Roche, Ensminger, & Cherlin, 2007). Cross-cultural studies have found differences in parenting practices between minority groups (Roche et al., 2007), which may affect parenting stress and youth outcomes.

Contextual Factors

Family structure is included as a contextual characteristic variable because it has been linked strongly to youth outcomes. Adolescents have been found to be more likely to engage in problem behaviors if they live in a single-parent family or with a mother and stepfather (Hoffman, 2006). Family structure has been linked also to higher levels of chronic maternal stress, although not specifically parenting stress (Cairney, Boyle, Offord, & Racine, 2003).

Family conflict is included as a contextual variable because higher levels of parent–child conflict typically are seen in early adolescence, and the conflict is associated with decreased parent well-being (Dekovic, 1999) and adolescent problem behavior (Buehler, 2006). Of greater concern, parenting stress, in a study based on the 2003 National Survey of Children's Health, was the factor most closely related to violent and heated disagreements in the home (Moore, Probst, Tompkins, Cuffe, & Martin, 2007).

Certain characteristics of family atmosphere are associated with better youth outcomes across ethnic and socioeconomic groups. These characteristics include emotional closeness, parental attachment, and a sense of support (Steinberg, 2001). Family cohesion (extent of emotional closeness and dependability, support, and clear communication among family members) and family involvement were used as indicators of family atmosphere. Cohesion has been related to positive youth adjustment (Magnus, Cowen, Wyman, Fagen, & Work, 1999). Adolescents with strong attachments to their families are less likely to use drugs and alcohol, attempt suicide, engage in violent behavior, or be sexually active at a young age (Resnick et al., 1997).

Social support is included as a contextual characteristic because it relates positively to parent functioning across income levels (Raikes & Thompson, 2005), predicts positive attitudes toward parenting (Suarez & Baker, 1997), improves parental mental health (Rodgers, 1998), and decreases stress (Pinderhughes et al., 2001). Importantly, social support for low-income parents, often in the form of extended family, may moderate the impact of poverty on parenting stress by improving parental psychological distress (Raikes & Thompson, 2005).

Socioeconomic status is an important determinant of parenting stress. Families in poverty are subjected to chronic levels of stress because of financial strain, which diminishes the resources they have to deal with the stresses of daily life. This chronic stress can diminish parent and adolescent psychological well-being (Taylor, Rodriguez, Seaton, & Dominguez, 2004) and may contribute to family conflict (Moore et al., 2007).

Methods

Sample and Design

A secondary analysis of cross-sectional questionnaire data was used for the exploratory analysis and hypothesis testing. Data were taken from seven sites across the United States associated with Cohort III of the Center for Substance Abuse and Prevention/SAMSHA Mentoring and Family Strengthening Prevention Initiative to reduce alcohol and other drug participation among youth through family strengthening techniques (Table 1; Bellamy et al., 2004). Each site was responsible for recruiting families at high risk of substance use, usually from communities considered at risk because of high levels of poverty, crime rates, or youth substance use. The sites also were required to include comparison groups of parents and youth similar with those receiving the family strengthening intervention. All of the participants were parent–child dyads. The parents were instructed to respond with answers specific to the child who was participating in the study with them. All participants were asked to complete a baseline survey 30 days before the intervention group participated in family strengthening programs. Data from the baseline survey of both intervention and control group parents were used in this study (total n = 824). Data were collected between 2002 and 2004 from 824 adult parents of youth with the ages of 10 to 18 years. Permission was received from the university health sciences institutional review board to use the existing anonymous SAMHSA data.

TABLE 1. Details of Sample Communities.

| Location | Recruitment | Risk factors | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Several Southwest U.S. border area states | Families voluntarily participating in a family strengthening program | High rates of violent crime, poverty, unemployment, and drugs | 172 |

| Large Eastern U.S. metropolitan area | African American families voluntarily participating in a kinship providers' support group | Poverty, low education levels, and families suffering from substance abuse and child abuse have led to kin, grandparents, and others providing care | 39 |

| A large urban area in a southwest state in the United States | Families voluntarily participating in a strengthening families program who have fled from war and civil and political persecution in the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia and Central and South America | An underserved “invisible” population at high risk of substance abuse and violence | 72 |

| Large Southeastern U.S. metropolitan area | Program for parents in substance abuse treatment and recovery and a strengthening families program to high-risk families in the Dependency Drug Court, also from a pediatrician's office and a local military base | Families at high risk because of substance abuse | 42 |

| Suburban and rural Midwestern area of the United States | Families participating in a family strengthening program as ordered by a truancy court and first offenders program | Youth participating in risk behaviors such as underage drinking, truancy, and curfew violations | 142 |

| Small city and surrounding rural area in a Northeastern U.S. state | Community-based families with youth in two middle schools (one rural and one urban) | Schools chosen because of poverty, population transience, and low-performing schools | 214 |

| Two Midwestern U.S. cities | Community-based sample | High levels of poverty | 143 |

Measures

All measures were part of a 321-item self-report questionnaire titled, “SAMHSA Adult Family Strengthening Baseline Survey” (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2002). Variables in the survey were chosen for this study based on their high reliability and theoretical relevance and represented three domains: child factors, parent factors, and contextual factors.

Domain 1: Child Factors

A single question to the parent determined the child's age. Using The Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliot, 1990), parents rated their child's behavior across three domains: social skills, problem behaviors, and academic competence. Data from the 71 items in the first two domains, social skills and problem behaviors, were used for this report. On a scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always, the social skills domain was used to assess cooperation (finishes assignments, attends to instructions, and follows directions), assertion (initiates conversations, introduces self, and invites others to play), responsibility (requests assistance, answers telephone, and reports accidents), empathy (feels sorry and understands feelings of others), and self-control (controls temper, compromises, and responds appropriately to teasing). Points were totaled in each subscale to produce a raw score.

Using the same 5-point scale, the problem behavior domain queried externalizing (fighting, threatening, bullying, and arguing) and internalizing (lonely, sad, depressed, and anxious) behaviors. Points were totaled in each subscale to produce a raw score and raw scores standardized. Reliability for the social skills domain ranges from .87 to .90 (Gresham & Elliot, 1990); reliability for the problem behaviors domain ranges from .73 to .87 (Gresham & Elliot, 1990).

Domain 2: Parent Factors

Parent gender was determined with a single question. Parents were asked to rate their overall health on a scale ranging from 1 = excellent to 4 = poor. Parents reported their racial or ethnic status using 24 racial and ethnic categories that were collapsed into four groups (African American or Black, Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic White, and some other race).

Domain 3: Contextual Factors

Family structure was determined by an item asking respondents to indicate from among four categories who was living with their child: both parents, one parent and one stepparent, single parent, or other (including adoptive families).

Family conflict was assessed with items from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Core Measures of prevention-related human behaviors (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). Parents were asked to respond to three statements on a scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always: “People in my family often insult or criticize each other,” “People in my family have terrible arguments,” and “We argue about the same thing in my family over and over.” The reliability of the Core Measures is .82 (Tolan et al., 1997).

Parent perception of family functioning was assessed using items from the Effective Black Parenting Module (EFP)—Family Strengthening Scale (Tolan et al., 1997); parents completed a 6-item scale for family cohesion and a 12-item scale for family involvement, both measured on a response scale of 1 = never to 5 = always. Scale reliability is reported at .80 for cohesion and .78 for involvement (Tolan et al., 1997). The scale was cross-validated by the developers with families across racial or ethnic and socioeconomic groups and found to be valid for use with diverse racial and ethnic samples (Tolan et al., 1997). In this sample, reliabilities were found to be adequate for both family cohesion and family involvement across racial or ethnic groups (cohesion reliabilities were African American = .79, Hispanic = .76, and White = .83; involvement reliabilities were African American =.85, Hispanic =.83, and White = .87).

Social support was assessed with the 15-item Family Support Scale (Dunst, Trivette, & Deal, 1988), which asks parents to report, on a scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always, how often they received help or support in raising their child from informal kinship (other parents), social organizations (friends), spouse or partner support (spouse's or partner's parents), formal kinship (own children), and professional services (family's or child's physician). Cronbach's coefficient alpha was reported to be .77 for the total score, split-half reliability was .75, and test–retest reliability ranged from .41 to .75 across subscales (Dunst et al., 1988). An 8-point ordinal scale covering years of school ranging from 0 to 16 years measured education. Income was measured by a 6-choice scale ranging from 1 = $5000 to 6 = over $50,000.

Dependent Variable

Parenting stress was assessed with the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995), wherein parents respond to 36 questions on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The PSI-SF provides a total stress score and three subscale scores: parent distress, parent–child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child. The total stress score, the sum of the three subscale scores, was used for this report. High stress is a score at or above the 85th percentile; scores at the 90th percentile or above are considered clinically significant levels of stress (Abidin, 1995). Alpha reliability for the total stress score is .91 (Abidin, 1995).

Procedures

Parents completed paper-and-pencil surveys at all seven sites except one, where a computer-assisted format was used. Surveys were administered individually and in groups. Written informed consent was obtained, and each study site provided the participants with a $20 gift certificate or cash for their participation. A design and analysis group was provided by SAMHSA to assure quality across all the sites (Bellamy et al., 2004).

Data Analyses

Preliminary analyses involved generating descriptive statistics for all of the variables and assessing bivariate correlations among the study variables. The analysis of Study Aim 1 to determine the central correlates of parenting stress, and how it varies across parent, child, and contextual domains, was exploratory and involved a series of multiple regression analyses. The analysis of Study Aim 2 to determine the relationship of parenting stress with single parenting; parental health status; and two indicators of family atmosphere, cohesion and involvement; involved a series of hypothesis-testing multiple regression analyses.

An initial examination of item frequencies revealed minimal missing data (less than 5% of the total expected data) on all variables except for community–family social support, which had 6.6% missing data (n = 54). A split-half approach was used to control Type I error inflation during the exploratory analyses related to the first aim. The sample was randomly split in two; the first group was used to identify a smaller set of predictors that were tested in the second half. The full sample was used for analyses of the second aim, and the Bonferroni method was used to control for Type I error.

Results

Description of the Sample

Participants in this study were 824 adult parents of youth aged 10 to 18 years (Table 2). The sample was diverse except for gender, with 91.1% female respondents. Most participants were minorities, with 20.6% African American or Black, 31.7% Hispanic or Latino, and 41.1% White. Most were poor; the average yearly income was $26,620, with 51% of the sample earning below the federal poverty level. Many (36.7%) were single parents.

TABLE 2. Sample Characteristics.

| Characteristics | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent gender | ||||

| Male | 73 | 8.9 | ||

| Female | 751 | 91.1 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Parent age (years) | 41.92 years | 45.47 years | ||

| 18–29 | 55 | 6.7 | ||

| 30–39 | 415 | 50.4 | ||

| 40–49 | 261 | 31.7 | ||

| Above 50 | 81 | 9.8 | ||

| Total | 812 | 98.5 | ||

| Missing | 12 | 1.5 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.00 | ||

| Youth age (years) | 12.08 years | 1.99 years | ||

| 10–14 | 705 | 85.6 | ||

| 15–18 | 119 | 14.4 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Parent health | 1.91 | .707 | ||

| 1 = excellent | 229 | 27.8 | ||

| 2 = good | 461 | 55.9 | ||

| 3 = fair | 113 | 13.7 | ||

| 4 = poor | 19 | 2.3 | ||

| Total | 822 | 99.8 | ||

| Missing | 2 | .2 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Parent race or ethnicity | ||||

| African American or Black | 170 | 20.6 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 261 | 31.7 | ||

| White | 339 | 41.1 | ||

| Other | 49 | 5.9 | ||

| Total | 819 | 99.4 | ||

| Missing | 5 | .6 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Parent education | 12.59 years | 2.84 years | ||

| None | 8 | 1.0 | ||

| Grade school | 67 | 8.1 | ||

| Some high school | 142 | 17.2 | ||

| High school | 215 | 26.1 | ||

| Some college | 177 | 21.5 | ||

| College | 89 | 10.8 | ||

| Trade or technical | 74 | 9.0 | ||

| Post college | 46 | 5.6 | ||

| Total | 818 | 99.3 | ||

| Missing | 6 | .7 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Household income ($) | $26,620 | $22,830 | ||

| 0–10,000 | 209 | 25.4 | ||

| 10,001–20,000 | 211 | 25.6 | ||

| 20,001–30,000 | 121 | 14.7 | ||

| 30,001–40,000 | 98 | 11.9 | ||

| 40,001–50,000 | 45 | 5.5 | ||

| Over 50,000 | 114 | 13.8 | ||

| Total | 798 | 96.8 | ||

| Missing | 26 | 3.2 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 | ||

| Family structure | ||||

| 1 = both biological parents | 301 | 36.5 | ||

| 2 = one parent and one stepparent | 104 | 12.6 | ||

| 3 = single parent | 302 | 36.7 | ||

| 4 = other | 108 | 13.1 | ||

| Total | 815 | 98.9 | ||

| Missing | 9 | 1.1 | ||

| Total | 824 | 100.0 |

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

Bivariate correlations between the study variables are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The means and standard deviations are listed for all study variables in Table 5. The largest correlation among predictor variables was between youth social skills and family involvement (r = .60, p < .01). Collinearity was assessed using an analysis of variance inflation factors. The variance inflation factor statistics ranged from 1.043 to 2.795, which suggests the absence of a collinearity problem. In addition, hierarchical regression was used to address multicollinearity for each test conducted when the size of the correlation was .60 and greater. The hierarchical regression analysis addressed the multicollinearity issue by creating a shared covariance, which summarizes the degree to which the measures jointly account for variance in the dependent variable. A negative shared covariance was not observed in any of the relationships examined.

TABLE 3. Pearson Product–Moment Correlations Among Interval Variables and Parenting Stress.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Youth age | – | ||||||||

| 2. Social skills | −.19** | – | |||||||

| 3. Problem behavior | .16* | −.59** | – | ||||||

| 4. Family conflict | .16* | −.35** | .37** | – | |||||

| 5. Family cohesion | −.17* | .43** | −.24** | −.23** | – | ||||

| 6. Family involvement | −.30** | .60** | −.31** | −.28** | .53** | – | |||

| 7. Social support | −.094 | .12 | −.001 | −.01 | .20** | .23** | – | ||

| 8. Household income | .02 | −.10 | −.03 | .06 | .07 | −.12 | −.003 | – | |

| 9. Parenting stress | .32** | −.57** | .57** | .39** | −.40** | −.55** | −.05 | −.09 | – |

Correlation is significant at the p < .05 level.

Correlation is significant at the p < .01 level (two-tailed significance levels were used).

TABLE 4. Spearman Correlations Among Ordinal Variables and Parenting Stress.

Correlation is significant at the p < .01 level (two-tailed significance levels were used).

TABLE 5. Distributions of the Study Variables.

| Variable | n | M | SD | Minimum to maximum | Cronbach's α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Missing | |||||

| Youth age | 824 | 0 | 12.08 | 1.99 | 10 to 18 | |

| Social skills | 824 | 0 | 137.60 | 23.61 | 55 to 200 | .97 |

| Problem behavior | 824 | 0 | 28.60 | 8.12 | 12 to 55 | .94 |

| Gender | 824 | 0 | ||||

| Parent health | 822 | 2 | 1.91 | 0.71 | 1 to 4 | |

| Race or ethnicity | 819 | 5 | ||||

| Family structure | 815 | 9 | ||||

| Family conflict | 824 | 0 | 2.24 | 0.94 | 1 to 5 | .82 |

| Family cohesion | 824 | 0 | 3.95 | 0.71 | 1 to 5 | .79 |

| Family involvement | 796 | 28 | 3.86 | 0.70 | 1 to 5 | .85 |

| Social support | 824 | 0 | 2.24 | 0.69 | 1 to 5 | .80 |

| Education (years) | 818 | 6 | 12.59 | 2.84 | 0 to 18 | |

| Income ($1,000) | 798 | 26 | 26.62 | 22.83 | 5 to >50 | |

| Parenting stress | 824 | 0 | 87.26 | 24.99 | 36 to 169 | .95 |

Multiple Regression Analysis

Child Factors

The analysis revealed that the regression model was significant (p < .001, Table 6), with a multiple correlation coefficient of .65. The adjusted R2 indicated that child factors explained 42% of the variability in parenting stress, with youth social skills and problem behavior explaining most of the variability in parenting stress and youth age contributing only a small portion.

TABLE 6. Multiple Regression Analysis of Child Factor Variables Regressed on Parenting Stressa.

| Variables | Parenting stress (dependent variable) | Youth age | Social skills | Problem behavior | B | β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 80.49* | ||||||

| Youth age | .23 | – | 2.06* | .17 | .03 | ||

| Social skills | −.57 | −.08 | – | −.36* | −.34 | .07 | |

| Problem behavior | .57 | .11 | −.62 | – | 1.06* | .34 | .07 |

| M | 86.02 | 12.00 | 138.20 | 28.26 | R2 = .43b, | adjusted R2 = .42, | R = .65* |

| SD | 24.57 | 2.00 | 23.58 | 7.83 |

Note. B = unstandardized regression coefficients; β = standardized regression coefficient; sr2 = semipartial correlations.

Correlations between variables; means; standard deviations; B; β; sr2; and R2, adjusted R2, and R are included.

Unique variability = .17; shared variability = .26.

Significant in both split-half groups at p < .001.

Parent Factors

A regression equation predicting parenting stress from parent gender, health status, and the dummy variables for race or ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and White) was significant (p < .001; Table 7), but parent factors explained only 9% of the variability in parenting stress. Health status was found to be a statistically significant predictor of parenting stress (p < .001), but none of the other parent factors contributed significantly.

TABLE 7. Multiple Regression Analysis of Parent Factor Variables on Parenting Stressa.

| Variables | Parenting stress (dependent variable) | Parent gender | Health status | African American or Black | Hispanic or Latino | White | B | β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 72.63* | ||||||||

| Parent gender | −.01 | – | −1.33 | −.02 | .0002 | ||||

| Health status | .30 | .02 | – | 10.26* | .30 | .09 | |||

| African American or Black | −.10 | −.02 | .004 | – | −8.20 | −.13 | .006 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | .04 | .09 | −.02 | −.33 | – | −4.58 | −.09 | .002 | |

| White | .10 | −.08 | .001 | −.43 | −.57 | – | −.68 | −.01 | .0000 |

| M | 85.99 | 1.9 | 1.87 | .20 | .30 | .43 | R2 = .10b, adjusted R2 = .09, R = .32* | ||

| SD | 24.59 | .30 | .71 | .40 | .46 | .49 | |||

Note. B = unstandardized regression coefficients; β = standardized regression coefficient; sr2 = semipartial correlations.

Correlations between variables; means; standard deviations; B; β; sr2; and R2, adjusted R2, and R are included.

Unique variability = .10; shared variability = 0.

Significant in both split-half groups at p < .001.

Contextual Factors

The independent variables in this analysis included the contextual factors of family structure, conflict, family cohesion, family involvement, social support, parent education, and household income (Table 8). The regression model predicting parenting stress from the contextual factors was significant (p < .001), with a multiple correlation coefficient of .64. The adjusted R2 indicated that contextual factors explained 39% of the variability in parenting stress. Three regression coefficients were significant: family conflict, family involvement, and parent education. The family structure, family cohesion, social support, and parent income variables did not have significant effects on parenting stress.

TABLE 8. Multiple Regression Analysis of Contextual Factor Variables on Parenting Stressa.

| Variables | Parenting stress (dependent variable) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | B | β | sr2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 169.25* | |||||||||||||

| 1. Both biological parents | −.11 | – | −3.13 | −.06 | .001 | |||||||||

| 2. One biological parent and one stepparent | .04 | −.29 | – | −2.24 | −.03 | .0004 | ||||||||

| 3. Single parent | .08 | −.60 | −.29 | – | −2.86 | −.06 | .001 | |||||||

| 4. Conflict | .40 | −.15 | .03 | .12 | – | 6.63* | .24 | .05 | ||||||

| 5. Cohesion | −.43 | .11 | −.04 | −.07 | −.31 | – | −3.71 | −.10 | .006 | |||||

| 6. Involvement | −.54 | .03 | −.07 | −.05 | −.30 | .56 | – | −15.97* | −.42 | .11 | ||||

| 7. Social suptport | −.10 | .11 | −.01 | −.17 | −.05 | .20 | .23 | – | .80 | .02 | .0004 | |||

| 8. Parent education | −.20 | .01 | −.02 | −.03 | −.07 | .07 | .04 | .02 | – | −1.98* | −.13 | .01 | ||

| 9. Parent income | −.13 | .33 | .03 | −.33 | .05 | .09 | −.07 | −.04 | .35 | – | −1.58 | −.11 | .009 | |

| M | 85.51 | .37 | .12 | .38 | 2.22 | 4.00 | 3.91 | 2.27 | 4.63 | 2.88 | R2 = .40b, adjusted R2 = .39, R = .64* | |||

| SD | 24.52 | .48 | .33 | .49 | .88 | .66 | .65 | .70 | 1.58 | 1.74 | ||||

Note. B = unstandardized regression coefficients; β = standardized regression coefficient; sr2 = semipartial correlations.

Correlations between variables; means; standard deviations; B; β; sr2; and R2, adjusted R2, and R are included.

Unique variability = .19; shared variability = .21.

Significant in both split-half groups at p < .001.

Child, Parent, and Contextual Factors

A regression equation predicting parenting stress from all factors simultaneously was significant (p < .001; Table 9).

TABLE 9. Multiple Regression Analysis of Significant Child, Parent, and Contextual Factor Variables on Parenting Stress (n = 400)a.

| Variables | Parenting stress (dependent variable) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | B | β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 107.08* | ||||||||||

| 1. Youth age | .24 | – | 1.34* | .11 | .007 | ||||||

| 2. Social skills | −.57 | −.08 | – | −.15* | −.14 | .006 | |||||

| 3. Problem behavior | .58 | .13 | −.63 | – | .89* | .28 | .056 | ||||

| 4. Parent health | .29 | .18 | −.19 | .22 | – | 3.87 | .11 | .005 | |||

| 5. Family conflict | .40 | .15 | −.34 | .42 | .16 | – | 3.11* | .11 | .008 | ||

| 6. Family involvement | −.54 | −.18 | .64 | −.38 | −.10 | −.31 | – | – | −10.41* | −.27 | .014 |

| 7. Parent education | −.21 | −.01 | .08 | −.19 | −.22 | −.08 | .054 | .03 | −1.53* | −.10 | .007 |

| M | 85.65 | 12.02 | 138.70 | 27.93 | 1.87 | 2.22 | 3.90 | 4.62 | R2 = .52b, adjusted R2, = .51, R = .72* | ||

| SD | 24.64 | 2.00 | 23.77 | 7.76 | .71 | .89 | .65 | 1.59 | |||

Note. B = unstandardized regression coefficients; β = standardized regression coefficient; sr2 = semipartial correlations.

Correlations between variables; means; standard deviations; B; β; sr2; and R2, adjusted R2, and R are included.

Unique variability = .13; shared variability = .39.

Significant in both split-half groups at p < .001.

Six regression coefficients, youth age, youth social skills, youth problem behavior, family conflict, family involvement, and parent education, differed significantly from 0. Altogether, 52% (51% adjusted) of the variability in parenting stress was predicted by knowing the scores for the child factors of youth age, social skills, and problem behavior; the parent factor of parent health status; and the contextual factors of family conflict, family involvement, and parent education. The hierarchical analysis indicated that child factors accounted for the greatest unique portion of the shared variance in parenting stress followed by contextual factors and then parent factors.

Testing Hypotheses

Single Parenthood

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was calculated for the effect of single parenthood on parenting stress. The Bonferroni method was used to control for Type I error in hypothesis testing. Each hypothesis was considered a family of multiple tests. The significance level for this hypothesis is α < .02. Single parents reported a mean parenting stress score of 90.88, whereas those with partners had a score of 85.17, F(1, 822) = 10.11, p = .002. About one third of families with both biological parents present had parenting stress levels in the high-risk range; nearly half of single parents reported high risk levels. Thus, the first hypothesis was supported.

Parent Health

A one-way ANOVA was calculated for the effect of parental health on parenting stress. The significance level for this hypothesis was α < .03. Parents reporting excellent health had lower mean stress scores on the PSI-SF, and parents in fair or poor health had clinically significant high mean scores, F(3, 818) = 21.86, p < .001. A cross-tabular analysis with parenting stress scores recoded as ≤90 versus >90 revealed that almost 25% of parents in excellent health, almost 50% in good health, and nearly 60% in fair or poor health reported high risk levels of parenting stress, thus supporting the second hypothesis that parents in poorer health report more stress.

Parent Perception of Family Functioning: Family Cohesion and Involvement

Both cohesion and involvement were correlated significantly and negatively with parenting stress (rcohesion = −.44 and rinvolvement = −.55). The significance level for this hypothesis was α ≤ .005. The multiple regression equation using family cohesion and involvement to predict parenting stress was significant (p < .001) and revealed a multiple R2 of .32. The hierarchical analysis showed that parent involvement accounted for the greatest unique portion of the shared variance in parenting stress followed by family cohesion. The third hypothesis, that parents who report a less cohesive family atmosphere and less involved parenting will have higher parenting stress, was supported.

Discussion

The study results provide information on the parenting stress experiences of traditionally underrepresented populations including parents of adolescents and those parenting in high-risk communities. The child factors of high levels of youth behavior problems and low levels of social skills were found to be related closely to increased parenting stress, a finding that has been seen previously (Morgan, Robinson, & Aldridge, 2002). However, because youth problem behavior and social skills were reported by the parent in this study, it may be a source of bias. Mulvaney, Mebert, and Flint (2007) found that parents rate their child as having more problem behavior when there is less marital satisfaction, greater parenting stress, less cohesive and involved family relationships, and more family conflict.

Youth age and social skills were found to be related negatively, an unexpected finding given the assumption that social skills would improve as young people mature. It is possible that the high-risk youth in this study were engaged in escalating problem behaviors during their teen years, and parents' ratings of their social skills reflected this escalation. Another explanation would be that as parenting stress increased, parents' perceptions of their youth's problem behavior and social skills were affected by the stress, and it influenced their reporting.

Of the three domains, parent factors explained the least amount of variance in parenting stress, with health status being the only significant factor. The relationship, although weak, is interesting because parents reporting fair or poor health had mean stress scores that were in the clinically significant range. This conflicts with the results of one of the few studies which examined the relationship between parent physical health and parenting stress (Rotheram-Borus, Robin, Reid, & Draimin, 1998). Their study of parents with AIDS found that parent–adolescent conflict and stressful parenting were not influenced by the parent's health status but by other factors such as the parent's substance abuse. The parent health status variable, which was found to be related significantly to parenting stress when ANOVA was conducted on only those two variables, became nonsignificant when all variables in the model were entered into the regression equation. It is possible that child problem behavior or family conflict will affect parenting stress levels regardless of parent health status.

Differences in parenting across racial and ethnic groups appear to be associated with the safety of the family's environment. Pinderhughes et al. (2001) found that the differences in family atmosphere and discipline disappeared when neighborhood influences were considered. In this study, however, no significant differences were found in family cohesion or family involvement by parental race or ethnicity, and levels of parenting stress were similar across racial and ethnic groups perhaps because all the communities from which the sample was drawn were considered of high risk, many because of poverty and crime.

Contextual factors also explained much of the variance in parenting stress. Consistent with previous reports (Cairney et al., 2003), single parents reported higher stress levels than did parents with partners. This was a relatively weak but potentially important effect because the mean stress score for single parents reached clinical significance. Families with both biological parents present in the home had the lowest levels of parenting stress. Single parents and stepparents reported similar mean scores, supporting previous findings that stepfamilies experience more parent–child conflict and adolescent problem behaviors than do families with two biological parents (Avenevoli, Sessa, & Steinberg, 1999). When all of the model variables were entered into a regression equation, however, family structure was no longer significant. It may be that in this high-risk sample, low levels of conflict and high family involvement may be better predictors of parenting stress than family structure.

Also consistent with previous research, this study found family conflict to be a significant predictor of parenting stress. However, because this and most prior research on parenting stress have been correlational, the causal path for the relationship between conflict and parenting stress is not known. A somewhat unexpected finding was the correlation between youth age and family conflict. Previous results suggest that conflict peaks in early adolescence (Larson et al., 1996). More recent studies debate this trajectory of increasing conflict from middle to late adolescence; their findings vary according to methodological issues such as the use of questions regarding the frequency versus intensity of conflict (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Other research suggests that it may not be the conflict per se that causes the poor outcomes but the failure to resolve and repair relationships after conflict has occurred (Wilson & Gottman, 2004).

Parents reporting greater family cohesion and involvement had less parenting stress than those with less cohesion and involvement, but involvement emerged as a more important predictor of parenting stress than cohesion. Conger, Patterson, and Ge (1995) noted that parents who report higher levels of stress related to parenting are more likely to feel less involved in their children's lives. Family involvement also was related to youth age. As age increased, family involvement decreased, a finding consistent with past research on U.S. samples (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). No differences were found in cohesion or involvement by economic status or by racial or ethnic group. This information, with the results from studies reporting that family cohesion is related to positive youth adjustment (Gorman-Smith et al., 2000), may indicate that family cohesion is a benefit across varying ethnic, racial, and economic groups.

In high-risk communities, the presence of social networks can provide an important source of support for parents by providing help to parents directly and by influencing their parenting skills and self-efficacy indirectly (Marshall, Noonan, McCartney, Marx, & Keefe, 2001). However, there is evidence that environments with high crime and poverty may result in social isolation that can lead to stressed parents and poor youth outcomes (Pinderhughes et al., 2001). Despite the evidence that social support facilitates coping and adaptation to stress, a lack of social support was not a significant predictor of parenting stress in this sample. The measure of social support in this study, while querying parents about social networks, asked only for the amount of support received. It may be equally important to assess the timing, quality, and helpfulness of the support (Marshall et al., 2001).

The cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to infer causality. The study also was limited to those variables in the model for which data were available. In addition, the single participant, self-report methodology, may make it impossible to rule out common source variance explanations for significant findings (Holmbeck, Li, Schurman, Friedman, & Coakley, 2002).

Nearly half of the parents in this sample experienced high levels of parenting stress, and more than a third reported clinically significant levels. Most of this stress was related to child behavior. The stress may compromise their ability to parent effectively (Crnic & Low, 2002), escalate youth problem behavior (Lin & Chung, 2002), and increase family conflict (Moore et al., 2007). This study revealed that those most at risk include parents with low education levels, single parents, parents in poor health, youth with existing internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors, and families with high levels of conflict. Identifying parents in high-risk environments who are most at risk of parenting stress may help healthcare, social service, and education providers support them and may reduce the risk of youth problem behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted for a doctoral dissertation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing and supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Nursing Research (F31NR009305-01A1).

Data analysis was supported by Grant UD1 SP09563 from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, part of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The author is supported currently by a National Institutes of Health Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award (University of Wisconsin-Madison, KL2, 1KL2RR025012-01).

The author acknowledges the contributions of her doctoral committee to this study: William Aquilino, associate dean and professor, School of Human Ecology; Daniel Bolt, associate professor, School of Education; Kristin Lutz, assistant professor, School of Nursing; Sandra Ward, Helen Denne Schulte professor of nursing; and Susan K. Riesch, professor, School of Nursing, all at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In addition, Patricia Becker, Helen Denne Schulte professor emeritus, and Linda Manwell, research program manager, School of Medicine and Public Health, both at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Contents of this article are the responsibility of the author and do not represent official views of the funding agencies.

References

- Abidin RR. Parenting stress index. 3rd. Odessa, FL: Psychology Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Sessa FM, Steinberg L. Family structure, parenting practices, and adolescent adjustment: An ecological examination. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with divorce, single parenting, and remarriage. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy ND, Springer UF, Sale EW, Espiritu RC. Structuring a multi-site evaluation for youth mentoring programs to prevent teen alcohol and drug abuse. Journal of Drug Education. 2004;34(2):197–212. doi: 10.2190/X4PA-BD0M-WACM-MWX9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C. Parents and peers in relation to early adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2006;68:109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J, Boyle M, Offord DR, Racine Y. Stress, social support and depression in single and married mothers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38(8):442–449. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0661-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Patterson GR, Ge X. It takes two to replicate: A mediational model for the impact of parents' stress on adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66(1):80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Low C. Everyday stresses and parenting. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol 5. Practical issues in parenting. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 243–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dekovic M. Parent–Adolescent conflict: Possible determinants and consequences. International Journal of Behavioural Development. 1999;23(4):977–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Deal AG. Enabling and empowering families: Principles and guidelines for practice. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Brookline Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB, Florsheim P. Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African American and Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(3):436–457. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. The social skills rating system. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JP. Family structure, community context, and adolescent problem behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN, Li ST, Schurman JV, Friedman D, Coakley RM. Collecting and managing multisource and multimethod data in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27(1):5–18. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Tristan J, Wade E, Stice E. Does problem behavior elicit poor parenting? A prospective study of adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21(2):185–204. doi: 10.1177/0743558405285462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS, Winslow E, Schonberg M, Gilliom M, Criss MM. Neighborhood disadvantage, parent–child conflict, neighborhood peer relationships, and early antisocial behavior problem trajectories. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(3):303–319. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards MH, Moneta G, Holmbeck G, Duckett E. Changes in adolescent's daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(4):744–754. [Google Scholar]

- Lin YF, Chung HH. Parenting stress and parents' willingness to accept treatment in relation to behavioral problems of children with attention-deficit hyperactive disorder. Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;10(1):43–56. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000347582.54962.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus KB, Cowen EL, Wyman PA, Fagen DB, Work WC. Parent–Child relationship qualities and child adjustment in highly stressed urban Black and White families. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(1):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall NL, Noonan AE, McCartney K, Marx F, Keefe N. It takes an urban village. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22(2):163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew RF, Wang MQ, Bellamy N, Copeland E. Test of efficacy of model family strengthening programs. American Journal of Health Studies. 2005;20(3):164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Moore CG, Probst JC, Tompkins M, Cuffe S, Martin AB. The prevalence of violent disagreement in US families: Effects of residence, race/ethnicity, and parental stress. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1):S68–S76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J, Robinson D, Aldridge J. Parenting stress and externalizing child behavior. Child and Family Social Work. 2002;7:219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney MK, Mebert CJ, Flint J. Parental affect and childrearing beliefs uniquely predict mothers' and fathers' ratings of children's behavior problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:445–457. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Zelli A. Discipline responses: Influences of parent's socioeconomic status, ethnicity, beliefs about parenting, stress, and cognitive–emotional processes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(3):380–400. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster AM, Jones D. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikes HA, Thompson RA. Efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26(3):177–190. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, Ensminger ME, Cherlin AJ. Variations in parenting and adolescent outcomes among African American and Latino families living in low-income, urban areas. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(7):882–909. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers A. Multiple sources of stress and parenting behavior. Children and Youth Services Review. 1998;20(6):525–546. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Robin L, Reid HM, Draimin BH. Parent–Adolescent conflict and stress when parents are living with AIDS. Family Process. 1998;37(1):83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1998.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RG, Forehand R, Armistead L. The role of family processes and coping strategies in the relationship between chronic illness and childhood internalizing problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25(2):83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1025771210350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–Adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Silk JS. Parenting adolescents. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol 1. Children and parenting. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez LM, Baker BL. Child externalizing behavior and parents' stress: The role of social support. Family Relations. 1997;47:373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RD, Rodriguez AU, Seaton EK, Dominguez A. Association of financial resources with parenting and adolescent adjustment in African American families. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(3):267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, Zelli A. Assessment of family relationship characteristics: A measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9(3):1040–3590. [Google Scholar]

- Tosevski DL, Milovancevic MP. Stressful life events and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19(2):184–189. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000214346.44625.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Mentoring family strengthening: Adult—family strengthening cross-site baseline instrument code book. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. The Program Coordinating Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BJ, Gottman JM. Marital conflict, repair, and parenting. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol 4. Social conditions and applied parenting. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 227–258. [Google Scholar]