Synopsis

Many conditions presenting with clinical hard skin and tissue fibrosis can be confused with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). These disorders have very diverse etiologies and often an unclear pathogenetic mechanism. Distinct clinical characteristics, skin histology and disease associations may allow to distinguish these conditions from scleroderma and from each other. A prompt diagnosis is important to spare the patients from ineffective treatments and inadequate management. In this review, we highlighted nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy), eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman’s syndrome), scleromyxedema and scleredema. These are often detected in the primary care setting and referred to rheumatologists for further evaluation. Rheumatologists must be able to promptly recognize them to provide valuable prognostic information and appropriate treatment options for affected patients.

Keywords: scleroderma, eosinophilic fasciitis, nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, scleromyxedema, scleredema

Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis or SSc) is a relatively rare connective tissue disorder characterized by skin fibrosis, obliterative vasculopathy and distinct autoimmune abnormalities. The word scleroderma derives from Greek (skleros = hard and derma = skin), highlighting the most apparent feature of this disease, which is excessive cutaneous collagen deposition and fibrosis. Many other clinical conditions present with substantial skin fibrosis and may potentially be confused with SSc, sometimes leading to a wrong diagnosis. As summarized in Table 1, the list of SSc-like disorders is quite extensive, including other immune mediated diseases (eosinophilic fasciitis, graft-versus-host disease), deposition disorders (scleromyxedema, scleredema, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis/nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, systemic amyloidosis), toxic exposures including occupational and iatrogenic (aniline-denaturated rapeseed oil, L-tryptophan, polivinyl chloride, bleomycin, carbidopa) and genetic syndromes (progeroid disorders, stiff skin syndrome). In most cases, even when the etiology is known or suspected, the precise pathogenetic mechanisms leading to skin and tissue fibrosis remain elusive. Importantly, an attentive and meticulous clinical assessment may allow distinguishing these conditions from SSc and from each other. The distribution and the quality of skin involvement, the presence of Raynaud’s or nailfold capillary microscopy, and the association with particular concurrent diseases or specific laboratory parameters can be of substantial help in refining the diagnosis. In most cases a deep, full-thickness skin-to-muscle biopsy is necessary to confirm the clinical suspicion. Effective therapies are available for some of these conditions. For this reason, a prompt diagnosis is important to spare the patients from ineffective treatments and inadequate management.

Table 1.

Spectrum of scleroderma-like fibrosing skin disorders

| Immune-mediated/inflammatory | Metabolic |

| Eosinophilic fasciitis | Phenylketonuria |

| Graft Versus Host Disease | Porphyria cutanea tarda |

| Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus | Hypothyroidism (myxedema) |

| POEMS syndrme | |

| Overlap (SLE, dermatomyositis) | |

|

| |

| Deposition | Occupational |

| Scleromyxedema | Polyvinyl chloride |

| Systemic amyloidosis | Organic solvents |

| Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy) |

Silica |

| Epoxy resins | |

| Scleredema adultorum | |

| Lipodermatosclerosis | |

|

| |

| Genetic | Toxic or iatrogenic |

| Progeroid disorders (progeria, acrogeria, Werner’s syndrome) |

Bleomycin |

| Stiff skin syndrome (or congenital facial dystrophy) |

Pentazocine |

| Carbidopa | |

| Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (L-tryptophan) |

|

| Toxic-oil syndrome (aniline-denaturated rapeseed oil) |

|

| Post-radiation fibrosis | |

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; POEMS: Polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes

Some SSc-like diseases are obsolete and mostly of historical interest (i.e. toxic oil syndrome, L-tryptophan eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome), others are extremely rare (i.e. genetic disorders). In the present report, we reviewed the most common diseases mimicking SSc, such as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, eosinophilic fasciitis, scleromyxedema, scleredema. The onset and initial progression of these conditions is often detected by general practitioners. A prompt referral to specialized centers is extremely important to refine or confirm the diagnosis and to initiate the appropriate treatment.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy)

Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD) or nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) was unknown prior to 1997 when the first few cases were observed in California and subsequently reported in 2000 (1). These patients were presenting with a rapid confluent fibrotic skin induration associated with lumpy-nodular plaques, pigmentary changes and flexion contractures of the extremities. The lesions were histologically characterized by fibroblast proliferation, thickened collagen bundles and mucin deposition, similar to those observed in scleromyxedema. The common denominator for these patients was a history of renal failure and hemodialysis treatment. Their renal disease was secondary to multiple etiologies and in some cases previous (failing) renal transplantation was present. Despite the initial geographical clustering, patients with similar presentation have been reported worldwide without any ethnic background predilection. Both genders are equally affected (female to male ratio 1:1), with a broad age range (8–87 years), including several pediatric cases (2). In the United States, a NSF registry has been established with more then 200 cases collected to date (3). However, it is likely that the real incidence is much higher and that many existing cases have not been diagnosed or reported.

The disorder was initially called “nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy,” indicating the association with renal disease and the apparent involvement of the skin (4). However, subsequent evidence indicated that the fibrosing process was present within muscles, myocardium, lungs, kidneys, and testes (5). Thus, the term “nephrogenic systemic fibrosis” is now preferred to recognize the potential systemic nature of this disorder.

Renal disease is invariably present in NSF, but neither the underlying cause nor its duration seems to be relevant. In general, at the time of diagnosis, 90% of patients have been already on hemo- or peritoneal dialysis for a variable period, following acute or chronic renal failure. No other specific clinical conditions have been temporally associated with NSF, with the exception, in different case series, of previous renal transplantation (often malfunctioning), hypercoagulable states, thrombo-embolic manifestations and vascular surgery or procedures (3). Some authors have speculated about of the almost concurrent emergence of NSF with new dialysis components (e.g dialysate fluids or membranes) or treatments for patients with renal failure (e.g. erythropoietin and ACE inhibitors), without convincing correlation (6,7). However, it was also noted that gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI or MRA) started to be commonly employed in the clinical setting and in particular in renal patients during the early-mid 90’s right before NSF identification. Over the past two years, evidence for an association between use of gadolinium and subsequent development of NSF has been growing.

Etiopathogenesis

A strong association between exposure to gadolinium-containing contrast agents and the development of NSF in patients with renal failure (HD or GFR< 15 ml/min) has been initially reported by two retrospective European studies in 2006, and subsequently confirmed by other authors (8–10). Recently, deposits of gadolinium and other metals have been shown within NSF skin lesions, strengthening the relevance of the epidemiological observations (11). Gadolinium (Gd) is normally complexed into chelates (e.g. Gadodiamide or Gd-DTPA-BMA or Omniscan®) which are soluble and thus suitable for clinical use. In patients with renal failure Gd half life is substantially increased (from 1.3 h up to 120 h) and Gd-chelate complexes tend to be displaced by excess of certain metal ions such as iron, copper or zinc (transmetallation) (12). This dissociation may be further enhanced by a persistent underlying metabolic acidosis. Free Gd ions are less soluble and have a propensity to precipitate into different tissues through direct interaction with cation-binding sites on cellular membranes and extra cellular matrix (ECM), or through microembolization in aggregate form (13). This would explain the presence of Gd deposits in the skin and soft tissues of patients with prior exposure to this contrast material. A direct pathogenetic role of Gd in NSF has yet to be proven. Nevertheless, the Food and Drug Administration has issued, in December 2006, a public health advisory recommending avoidance of gadolinium-based contrast agents in patients with moderate to end-stage kidney disease (14).

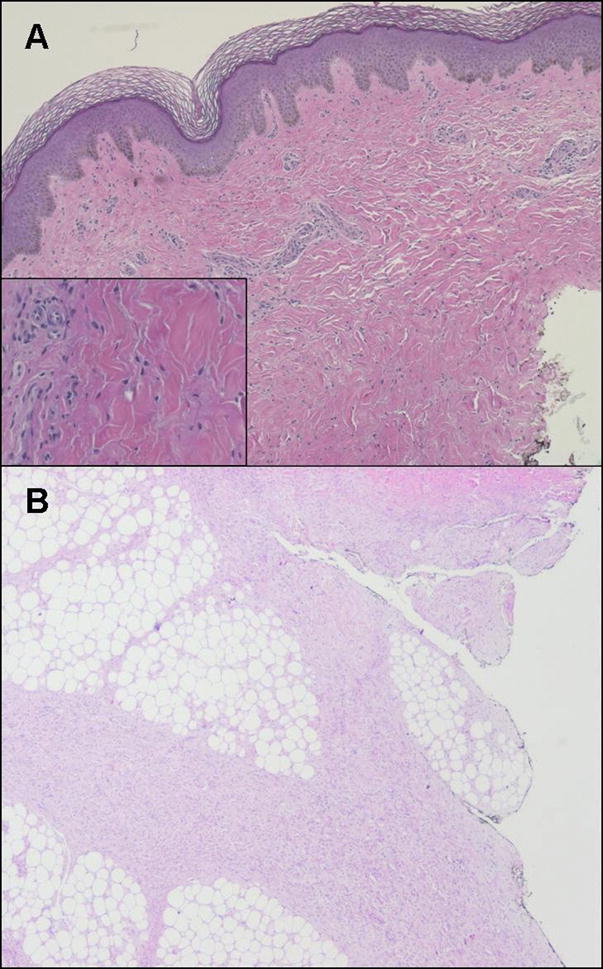

The typical histology of NSF skin lesions is characterized by thickened disorganized collagen bundles separated by large clefts and surrounded by dominant fibroblast-like epitheliod or stellate cells (spindle cells), with positive staining for procollagen-I and CD34+ and abundant mucin deposition (Fig. 1A). Inflammatory infiltrates are usually absent, but dendritic and multinucleated giant cells are sometimes present. The infiltrative process usually extends into subcutaneous structures such as adipose interlobular septa, fascial planes (fasciitis) and even deeper into muscle layers, where fibrosis and atrophy can be detected (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, CD34 is a specific marker for adult hematopoietic stem cells, suggesting that these spindle fibroblast-like cells (called fibrocytes) may be circulating and derive from the bone marrow (15). The mechanisms of fibrocyte recruitment into affected tissues are unknown and may result from active (chemotaxis) or passive transmigration. The association with high doses of erythropoietin use in patients with NSF has been reported (7). Despite the fact that this hormone has the ability to mobilize hematopoietic progenitors from the bone marrow, including mesenchymal precursors, and contribute to fibrin-induced wound healing, its role in the pathogenesis of NSF has yet to be elucidated (16).

Figure 1.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. (A) Dense dermal fibrosis is present under a normal epidermis. Disorganized collagen bundles are separated by large clefts and surrounded by numerous fibroblast-like (spindle) cells. Minimal perivascular inflammatory infiltrate is present. (B) The infiltrative process is deep, extending into subcutaneous adipose interlobular septa.

Clinical Features

The cutaneous lesions of NSF usually develop over a short period of time (days to weeks), and subsequently assume a chronic, unremitting course. The distribution is often symmetrical, commonly involving the lower extremities up to the knees and the upper extremities up to the elbows. More proximal spread as well as extension to the trunk is possible. The face is usually spared. The skin is characterized by a lumpy-nodular thickening with a tendency to form indurated irregular plaques. During early stages these areas may appear slightly edematous with “peau d’orange” and erythematous surface features, and can be easily confounded with cellulitis, lymphangitis or chronic (lymph) edema, not unusual in nephropathic patients. Over time, the skin tends to become bowed-down, with “cobblestone” appearance and brawny hyperpigmentation. Objectively, the affected areas and subcutaneous tissues are extremely hard, “woody,” and can be slightly warm to touch. The joints underlying NSF lesions are usually involved by a deep fibrotic process causing severe flexion contractures (particularly hands, wrists, ankles and knees) with substantial loss of range of motion and significant disability. Even ambulation can become severely compromised, and patients can be confined to a wheelchair.

The symptoms in NSF are usually dramatic. The skin and the joints involved by the tight fibrotic process are extremely tender. Pruritus and a burning sensation are very common over affected areas. Nerve conduction studies seem to confirm the presence of a true peripheral neuropathy, further complicating the management of the underlying pain syndrome, which is usually very difficult to control.

Even if no specific diagnostic test is available, the detection in the right clinical context (renal failure) of the characteristic skin changes with unremarkable laboratory findings is adequate to prompt a reasonable suspicion for NSF. In most cases, the distinctive histopathology is confirmatory. Imaging and in particular MRI (without contrast) can be very helpful to define the extension of the deep fibrosing process as well as the presence of calcifications. An increased T1 signal is often present within the muscles underlying affected surfaces suggesting presence atrophy and fat degeneration. In addition, fat suppression protocols (e.g. fat-suppressed fast T2-weighted sequences) can reveal presence of fascial and muscular edema, particularly during early phases of the disease.

Differently from SSc, in NSF serological markers for autoimmunity are absent and nailfold capillary microscopy examination is normal (see Table 2). The body distribution can be similar to SSc (i.e. hands can be fully involved), but the face is usually spared. The cobblestone appearance, brawny hyperpigmentation tend to differ from typical SSc skin lesions. Raynaud’s phenomenon is usually not present.

Table 2.

Differentiating features between scleroderma and scleroderma-like fibrosing disorders.

| Scleroderma | Scleromyxedema | Scleredema | Eosinophilic Fasciitis | Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Skin findings | |||||

| Quality | Indurated, thick | Papular, waxy | Indurated, doughy | Woody induration | Cobblestone, nodular, indurated plaques |

| Distribution | Fingers, hands, extremities, face, chest. Back spared | Face, neck, extremities, fingers | Neck, back, face | Extremities, trunk. Hands and feet spared | Extremities, trunk, hand, feet. Face spared |

|

| |||||

| Systemic Disease | |||||

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Almost universal | Not common | No | Unusual | Unusual |

| Nailfold capillaries | Universally abnormal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Antinuclear Antibody | Positive 95–100% | Uncommon | Negative | Uncommon | Negative |

| Neurologic Disease | Rare | Seizures, dementia, coma | None | Carpal tunnel syndrome | Peripheral Neuropathy |

|

| |||||

| Histological Changes | |||||

| Mucin on biopsy | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Fibrosis | Dermal, epidermal | Dermal | Dermal | Dermal, hypodermal | Dermal, epidermal |

| Fibrocytes | No (possible) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Inflammation | Perivascular | Perivascular | No | Yes, with/without eosinophils | No |

|

| |||||

| Clinical Associations | Monoclonal gammopathy | Infection, monoclonal gammopathy, diabetes | Morphea, immune-mediated cytopenias, hematologic and solid malignancies | Acute or chronic renal failure, renal transplant, exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents | |

Treatment and prognosis

No effective treatment is currently available for patients with NSF. In some cases the normalization of kidney function has been associated with arrest of disease progression and partial reversal of skin lesions, but this is not the rule. Numerous publications have been suggesting favorable therapeutic strategies (17). However, these were most exclusively anecdotal reports or very small patient series. The reported responses were invariably modest and incomplete. Often, important details about concurrent changes of the underlying kidney function were missing. Most importantly, the results obtained have not been consistently replicated by different centers.

Immunosuppression (i.e. cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, mycofenolate mofetil) does not seem to introduce any substantial advantage, even during early stages, when the lesions tend to evolve more rapidly. Interestingly, patients with renal transplantation experience development or progression of NSF despite being on potent anti-rejection immunosuppressive medications (i.e prednisone, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or rapamycin). Topical preparations, including corticosteroids creams, are of limited help.

Extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) has been reported as effective by different groups, but usually requires long periods (months) of administration and achieves mild results (18,19). Plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) and ultraviolet (UV-A1) phototherapy have also been proposed (20–22). In our experience, these treatment strategies have been overall disappointing. A recent report indicates that intravenous sodium thiosulfate is beneficial (23). This is of interest since dystrophic dermal calcifications similar to those seen in calciphylaxis are observed in NSF patients.

Aggressive physical therapy remains the most important recommendation and plays a fundamental role in preventing progression of flexion contractures, muscular atrophy and overall disability. Pain management is extremely challenging, often requiring a combination of agents targeting musculoskeletal as well as neuropathic pain. Narcotics are often used at high doses, but their efficacy is never satisfactory and decreases over time. Newer drugs with direct anti-fibrotic effects are being considered in NSF treatment. Substantial skin improvement has been reported with the use of imatinib mesylate (108).

Eosinophilic Fasciitis

In 1974 Schulman reported two patients presenting with scleroderma-like skin changes and painful induration of subcutaneous tissues involving the extremities associated with hypergammaglobulinemia, striking peripheral eosinophilia and histological evidence of diffuse fasciitis (24). This syndrome was later named “eosinophilic fasciitis” (EF) by Rodnan et al. (25). Other names used to designate this clinical entity are “Schulman’s syndrome” or “diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia”. Since the very first description, there have been more then 250 cases reported in literature; however the true incidence remains unknown. The only substantial case series (52 patients) was from the Mayo Clinic, published in 1988 (26). EF tends to be more frequent in males (2:1 ratio), affecting adults in their second to sixth decade of life. More than 30 pediatric cases have been reported with clinical characteristics similar to those of the adult occurrence, except with higher prevalence in females (27). EF is largely more prevalent in Caucasians, but sporadically it has been observed in Asian, African and African American patients. Epidemics of two clinical entities similar to EF and resulting from the ingestion of toxic contaminants such as aniline-denaturated rapeseed oil and L-tryptophan have been identified in the past (28,29). Specifically, the toxic oil syndrome (Spain, 1981) and the eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (US, 1989) were characterized by eosinophilia, skin fibrosis and pathologic evidence of fasciitis. Differently from EF, these cases presented a more acute course, with fever, severe multisystem involvement and a high mortality rate. No new cases have been reported over the past decade and these conditions are now mostly of historical significance.

Etiopathogenesis

The fibrotic changes of EF develop rapidly in the context of an exaggerated immune response and pro-inflammatory environment. Peripheral blood and tissue eosinophilia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and elevated inflammatory markers are dominant features and correlate with disease activity as well as with response to treatment (26).

The classic histopathologic changes in EF are dermal-hypodermic sclerosis associated with fibrotic thickening of the subcutaneous adipose lobular septa, superficial fascia and perimysium. The epidermis is usually spared. The adjacent muscles can present mild inflammation without evidence of necrosis. The fibroblastic proliferation is associated with an inflammatory infiltrate, characterized predominantly by macrophages and CD8+ T cells exhibiting an activated cytotoxic phenotype (30). Eosinophils can be enriched within affected tissues, but they may not be present when biopsies are obtained after institution of corticosteroid therapy. Elevated serum levels of type two cytokines such as IL-5 and other pro-fibrotic molecules (TGF-β) have been reported in patients with active disease (31,32). IL-5 plays an important role in the chemotaxis, activation and regulation of eosinophil effector function (33). Tissue infiltrating eosinophils can generate important local fibrogenic stimuli by increasing their expression of TGF-β and by releasing toxic cationic proteins upon degranulation. In-vitro studies have shown the ability of eosinophils to stimulate matrix production in dermal fibroblasts (34). An activated phenotype, along with increased collagen expression, has been shown in fascial fibroblasts isolated from EF lesions (35).

Different potential triggers have been considered for EF. An antecedent history of vigorous exercise or trauma is present in about 50% of the cases (26). A positive serology for B. burgdorferi has been reported and spirochetal organisms have been identified in some EF lesions (36,37). However, these findings have not been consistently reproduced (38). Toxic exposures other than aniline-denaturated rapeseed oil and L-tryptophan have not been proven. The association between EF and other autoimmune manifestations such as immune-mediated cytopenias and localized scleroderma has been observed. Morphea in particular is often reported in conjunction with EF (39,40). Commonly, it presents in the generalized form or with discrete areas of deeper fibrosis sparing the superficial skin layers (morphea profunda). EF and morphea can have an asynchronous clinical course. In up to 10–15% of EF patients, underlying hematological disorders or malignancies have been found (26). A causal relationship between EF and these potential triggers or associated conditions remains unclear and, to date, unproven.

Clinical Features

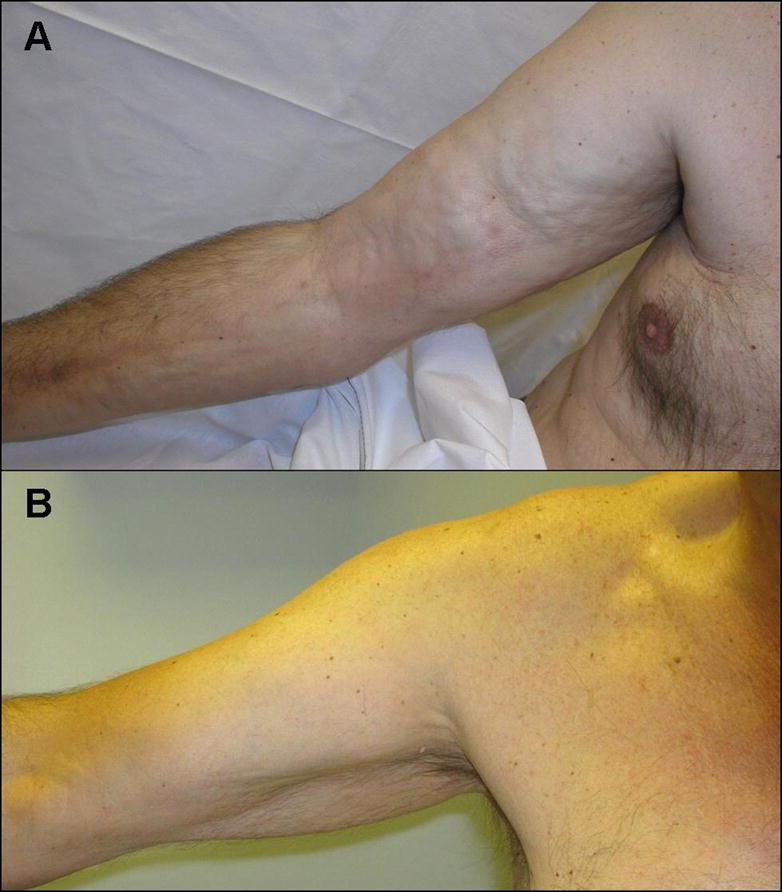

The classic onset of EF is usually acute with rapid and symmetric spreading of skin changes over the extremities within a short period of time (days to weeks), in particular over forearms and calves. Less frequently, the disease process can be confined exclusively to the legs or the arms, or affect an individual limb. The trunk and the neck can also be involved. The hands and face are generally spared, except for some isolated reports (26). During the early inflammatory phase, the skin is edematous, with dimpling and “peau d’orange” appearance. This is followed by a progressive induration of subcutaneous tissues, which can acquire a “marble-like” consistency. Tethering of the dermis to the fascial and muscular layers causes skin puckering and venous furrowing (Fig. 2A). These are very typical in EF and particularly visible over the medial aspect of arms and thighs. Importantly, the more superficial layers of the skin are not affected by the fibrotic process, and wrinkling of the epidermis can still be elicited by gentle pinching. Hair loss is common in affected areas.

Figure 2.

Eosinophilic fasciitis. (A) Patient presenting bilateral involvement of upper extremities with typical “woody” induration of the skin and “puckering”. (B) The same patient after 12 months of corticosteroids treatment.

Deeper involvement and fibrosis of periarticular structures can prompt severe flexion contractures as well as disturbances secondary to peripheral nerve compression, such as carpal tunnel syndrome. Raynaud’s phenomenon can be present, but the nailfold capillary microscopy examination is normal. True joint inflammation has been reported, presenting as a symmetric polyarthritis of the small joints (hands) or as oligo-monoarthritis (knees) (26). Constitutional symptoms such as profound fatigue and weight loss can be observed in patients with aggressive disease presentation. EF does not usually manifest with visceral involvement. However, extensive trunk fibrosis or neck/laryngeal scarring can be associated with significant breathing or swallowing difficulties.

Peripheral eosinophilia is commonly present in up to 80% of cases but is not a prerequisite for diagnosis. Other relevant laboratory findings include polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, increased inflammatory markers (i.e erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein) and, occasionally, elevated muscular enzymes (aldolase and creatine phosphokinase) suggesting the presence of underlying muscular involvement. Antinuclear antibodies are rarely positive and SSc-specific autoantibodies are usually absent. Presence of cytopenias isolated or in combination always warrants further investigation, since they may be secondary to underlying hematological disorders, including immune-mediated anemia or thrombocytopenia, pure red cell aplasia, aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and lymphoprolipherative processes (T or B cell lymphoma, multiple myeloma) (41–45). To obtain a definitive diagnosis, an incisional full-thickness biopsy should be pursued. MRI can be very useful to confirm the diagnosis of EF, to monitor the response to therapy or to evaluate patients when disease relapse is suspected (46). Appropriate MRI image sequences (i.e. fluid-sensitive) can show in great detail the presence of fascial thickening and edema, as well as the involvement of muscular structures.

Compared to SSc, the epidermis in EF is spared by the fibrotic process. Raynaud’s phenomenon and visceral involvement are uncommon (see Table 2). Nailfold capillary microscopy is normal. Autoimmune serology is negative. Corticosteroids are rapidly effective.

Treatment and Prognosis

There is substantial agreement among published cases or case-series that corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for EF and usually effective in more then 70% of the patients (Fig. 2B) (26,47). Other therapies including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antihistamines (cimetidine), D-penicillamine or antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine) have been reported, but their efficacy has not been confirmed (26). Spontaneous resolution has also been observed in some cases.

The ultimate goal in treating EF patients is a complete resolution of the fibrotic manifestations and this is predicated on an early initiation of the treatment followed by slow tapering. Prednisone (or equivalent corticosteroid) is usually initiated at doses ranging from 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily. This is maintained until the clinical response is evident, in general within few weeks. Subsequent tapering is slow, particularly with doses below 20 mg daily, and it may take up to 12–18 months to achieve a satisfactory or full response. In patients with aggressive presentation such as extensive body surface involvement, significant weight loss, or when trunk or neck are affected, we usually start corticosteroids at the highest doses, often in combination with a second immunosuppressive drug such as methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil. This strategy allows faster control of the disease and, in the long run, avoidance of excessive cumulative steroid load. A second agent is also useful to achieve further benefit in refractory (unusual) or relapsing cases. In a recent review of 88 published EF cases, clinical variables associated with poor outcome (defined as refractory disease or residual skin fibrosis despite prolonged treatment) were young (pediatric) age of onset, presence of morphea lesions and trunk involvement (39). Importantly, the absence of a response should always prompt further investigation to rule out presence of an underlying malignancy. Physical therapy plays an important role throughout the disease course to limit the long term consequences of flexion contractures and disability. Overall, the prognosis of EF is good. Even if prolonged treatment is necessary, the vast majority of patients usually achieves full disease remission and cure.

Scleromyxedema

Scleromyxedema (papular mucinosis) is a condition of mucinous deposition in the skin associated with a presence of a monoclonal gammopathy characterized by a flesh-colored, papular skin eruption. The exact prevalence of scleromyxedema is unknown as no formal epidemiologic studies have ever been performed. However, it is thought to be quite rare, with approximately 150 cases described in the English medical literature. Even this number is difficult to interpret, given that the terminology for this condition has varied with time and many cases may have been misclassified. For example, early cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may have been misdiagnosed as scleromyxedema before the condition was defined. New terminology proposed by Rongioletti in 2001 defines lichen myxedematosus as a broader term under which both scleromyxedema (diffuse, systemic form) and papular mucinosis (focal form) fall (48). The largest series of scleromyxedema cases to date was published from the Mayo clinic in 1995, where 26 patients evaluated at their institution from 1966–1990 were reviewed. This series found that the average age of onset was 55 years and there was a roughly equal distribution of gender. In our center, where we have evaluated 12 patients, we found that the average age of onset is 51 ± 12 years (range 35–74) and the female to male ratio is 3:1. This illness has not been reported in children.

Etiopathogenesis

Histological findings reveal three key features: extensive interstitial mucin deposition throughout the dermis with thickened collagen bundles and wide intercollagenous spaces, an increased number of fibroblast-like cells (fibrocytes) and an enhanced inflammatory infiltrate (49). The etiology of scleromyxedema is unknown. In almost every reported case, there has been demonstration of a monoclonal protein in the peripheral blood. In one scleromyxedema patient with absent circulating paraprotein, evidence of a monoclonal protein was found in the affected skin lesions (50). Not surprisingly, given the striking association with circulating paraproteins, several groups have investigated the possible direct pathogenic role these proteins may play. Ferrarini demonstrated stimulation of fibroblast cells by serum from one scleromyxedema patient (51). Another study found that serum from scleromyxedema patients can stimulate in vitro fibroblast proliferation (52). However, these results could not be replicated using purified immunoglobulin from patient’s sera. These conflicting data would perhaps suggest that the measurable paraprotein does not have a direct role in the pathogenesis of scleromyxedema through direct tissue fibroblast stimulation. A study of 5 patients who underwent peripheral blood stem cell transplant (PBSCT) showed that only 2 patients had an eradication of their monoclonal protein and that there was no relationship between clinical improvement and monoclonal band disappearance (53). Additionally, as we and others have observed, the level of paraprotein does not decrease even after effective treatment, and there seems to be no dose-dependant relationship between paraprotein quantity and clinical effects. Ferrarini suggested an intrinsic abnormality of the scleromyxedema fibroblasts, since they were exhibiting an increased glycosaminoglycan (GAG) synthesis at baseline compared to controls, but this was not increased with addition of serum (51). Taken together, these data suggest that in scleromyxedema there may be an intrinsic fibroblast defect or possibly other (unknown) circulating factor(s) that can activate fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Clinical Features

The cutaneous findings in scleromyxedema are fairly uniform in appearance and location among different patients. The skin is indurated and papular in quality with a cobblestone feel, and its involvement occurs in a characteristic distribution with the glabellum, posterior auricular area and neck being most commonly affected (Fig. 3). Other areas include the back and extremities and may be similar in distribution to scleroderma. One important difference, however, is that the mid portion of the back, commonly affected in scleromyxedema, is almost never involved in scleroderma patients. Sclerodactyly can be present, although papular in quality. In addition to skin findings, patients may have organ involvement that seems to mimic the pattern of scleroderma. Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility and myopathy have been reported (54). Less common but potentially life threatening complications may involve the neurological system in the form of encephalopathy, seizures, coma and psychosis (55–59). Additionally, pulmonary hypertension has been described in patients with scleromyxedema as well. The texture of the skin and the histological findings (deep-incisional biopsy) remain the most important features distinguishing these two conditions (see Table 2).

Figure 3.

Scleromyxedema. Patient with classic papular-waxy skin eruption of the face

Treatment and Prognosis

The natural history of this disease has not been well defined, but fatal cases have been reported, most commonly due to neurologic complications (54,58,60). Various therapies have been employed to treat the symptoms of scleromyxedema with variable success. Historically, melphalan therapy has been the treatment of choice for this condition with multiple reports of benefit, but significant toxicity appears frequent (61–64). Case reports cite variable improvement with other immunosuppressants including cyclophosphamide and cyclosporine (65–68). There are multiple cases describing some benefit using thalidomide, although there remains a legitimate concern for the development of disabling peripheral neuropathy (68–72). More recent data note benefit of autologous stem cell transplantation in recalcitrant cases (53, 73–75).

Multiple groups have reported clinical improvement in scleromyxedema patients following therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (55,60,76–79). The first case report by Lister et al. summarizes two patients who were treated with 2 g/kg of IVIG monthly, with responses noted within 2–3 treatments and maintained by repeated infusions spaced at 10 week intervals (76). IVIG has also shown benefit in those patients with complicated neurologic manifestations such as dementia (55). None of the case reports document any significant long-lasting adverse effects following IVIG therapy. Although long-term follow-up (>3 years) is lacking, these published cases suggest that IVIG is not only an effective treatment for scleromyxedema but safe as well. In our center, we have treated 9 patients with IVIG reporting universal success, although we also noted that maintenance therapy is necessary.

Scleredema

Scleredema is also associated with deposition of collagen and mucin in the dermis and seems to occur in the setting of 3 conditions: poorly controlled diabetes, monoclonal gammopathies and after certain infections, particularly streptococcal pharyngitis. This condition causes scleroderma-like skin changes but in a distribution that is quite different than scleroderma. Scleredema is a rare condition. Although the exact prevalence is unknown, there are approximately 175 cases in the English medical literature from 1966 to present. The nomenclature is variable with “scleredema adultorum” and “scleredema of Buschke” often being used interchangeably to reflect presence of scleredema of any cause. “Scleredema diabeticorum” refers to scleredema related to diabetes only. The initial description by Buschke was a post-infectious case and some authors limit the eponym to this subset. There are also some references subtyping scleredema into 3 categories according to the three clearly defined disease associations: type 1 in those patients where a preceding febrile illness is identified; type 2 including those patients with an identified circulating paraprotein; type 3 in patients with diabetes. There is no clear gender difference and the disease has been reported in the US, Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia. Despite the name “adultorum”, there are many cases of post-infectious scleredema described in children (80).

It has been estimated that as many as 2.5–14% of diabetics have scleredema in some cross-sectional studies, so it is thought that this subset may be underreported (81–83). Diabetic patients can be either Type 1 or Type 2, but commonly tend to be poorly controlled, insulin-requiring and have evidence of diabetic complications such as microangiopathy and retinopathy. In one review of 7 cases of diabetes-associated scleredema, the ratio of M:F was 4:3, the mean age at onset was 54 years, the mean duration of diabetes was 13 years and they were noted to have a high frequency of diabetic complications (84).

Etiopathogenesis

The majority of literature reports find this disease to be associated with either febrile illness, monoclonal gammopathies or diabetes. However, some cases do not fit into one of these three diagnostic categories, and other atypical causal relationships have been considered such as mechanical stress and use of certain medications (infliximab)(85,86). In patients with type 2 disease, multiple types of monoclonal gammopathies have been described including multiple myeloma (IgG and IgA), monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia and generalized hypergammaglobulinemia (87–89). Poor diabetic control and presence of microvascular complications (retinopathy, neuropathy) seems to be the key risk factor among diabetic patients.

The pathology of scleredema is notable for marked thickening of the upper and lower dermis, mucin deposition between thickened collagen bundles. There are no clear hisopathological differences between the different subtypes of scleredema. In diabetes, it is thought that the abnormal metabolic state in the tissues leads to fibroblast activation and increased collagen synthesis. Like in scleromyxedema, the monoclonal proteins found in some patients with type 2 scleredema, do not have a clear pathogenic role. Multiple infectious agents have been associated with type 1 disease including streptococcus, influenza, varicella, measles and mumps. Other series only describe preceding febrile illness by history. No one has determined any clear direct relationship between these pathogens and the development of scleredema, but no thorough investigation has ever been conducted.

Clinical Features

Scleredema causes a non-pitting, doughy or woody induration of the skin that typically involves the neck, back, interscapular region, face and chest (Fig. 4). In one case series from China of 12 patients, 75% had neck involvement, 42% had back involvement and 17% with shoulder involvement (90). In this series 83% of patients were diabetic, none had previous infection and none had an identified paraprotein. Typically the extremities and in particular the distal portion are spared, but some cases of widespread involvement have been reported. In contrast with scleroderma, the mid back is commonly involved while the hands and fingers are not (see Table 2). Some cases have demonstrated marked involvement of the face causing ocular muscle palsy, diminished oral aperture and periorbital edema (91,92). Systemic involvement has been only infrequently reported, but some case reports highlight involvement of the tongue, pharynx and upper esophagus (92,93). Others have reported cardiac dysfunction with myocarditis (94,95).

Figure 4.

Scleredema. Patient with diabetes mellitus type 2 and skin induration of the neck and upper back

Treatment and prognosis

The natural progression of scleredema depends on the underlying associated condition. Patients with infection-related disease are noted to have a rapid onset of symptoms days to months after the infection, with a course that typically resolves in several months to two years. Patients with type 2 disease tend to have a very insidious onset with gradual progression of symptoms over many years. Also in diabetes-associated scleredema the onset is typically slow, but some improvement may occur as control of diabetes is established (96).

Since most cases of type 1, infection-associated scleredema, resolve spontaneously but there is little information regarding treatment. Some recommend the use of penicillin in cases where recent streptococcal infection is demonstrated. In diabetic patients there are data suggesting that improvement of glycemic control can impact the course of scleredema and reverse skin changes, but this is definitely not a universal phenomenon (97). Various immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids and methotrexate have been tried without clear benefit (97,98). Ultraviolet light therapy, in several forms, has been reported to be beneficial, including UVA-1 treatment, PUVA therapy (bath, cream, oral) and photophoresis (99–104). Several authors also reported some benefit with various types of radiation therapy (105–107).

Summary

There are many conditions that can mimic the appearance of scleroderma. In this review, we highlighted four scleroderma-like conditions that are often detected in the primary care setting and referred to rheumatologists for further evaluation. Rheumatologists must be able to promptly recognize these distinct entities in order to provide valuable prognostic information and treatment options for affected patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Scleroderma Research Foundation (Francesco Boin) and by the NIH 5K23AR52742-3 (Laura Hummers) awards.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Francesco Boin, Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Laura K. Hummers, Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

References

- 1.Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, et al. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):1000–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jan F, Segal JM, Dyer J, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: two pediatric cases. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5):678–81. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowper SE. [Accessed 11/05/2007];Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy NFD/NSF Website. 2001–2007 doi: 10.1097/00000372-200110000-00001. Available at http://www.icnfdr.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23(5):383–93. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(7):903–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazeli A, Lio PA, Liu V. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: are ACE inhibitors the missing link? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(11):1401. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.11.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swaminathan S, Ahmed I, McCarthy JT, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and high-dose erythropoietin therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(3):234–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-3-200608010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(9):2359–62. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobner T. Gadolinium--a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(4):1104–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khurana A, Runge VM, Narayanan M, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a review of 6 cases temporally related to gadodiamide injection (omniscan) Invest Radiol. 2007;42(2):139–45. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000253505.88945.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.High WA, Ayers RA, Chandler J, et al. Gadolinium is detectable within the tissue of patients with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grobner T, Prischl FC. Gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2007;72(3):260–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnhart JL, Kuhnert N, Bakan DA, et al. Biodistribution of GdCl3 and Gd-DTPA and their influence on proton magnetic relaxation in rat tissues. Magn Reson Imaging. 1987;5(3):221–31. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(87)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food and Drug Administration. Public Health Advisory: Gadolinium-containing Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) 2006 Http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/gadolinium_agents_20061222.htm.

- 15.Quan TE, Cowper S, Wu SP, et al. Circulating fibrocytes: collagen-secreting cells of the peripheral blood. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(4):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haroon ZA, Amin K, Jiang X, et al. A novel role for erythropoietin during fibrin-induced wound-healing response. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(3):993–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63459-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galan A, Cowper SE, Bucala R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy) Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18(6):614–7. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000245725.94887.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richmond H, Zwerner J, Kim Y, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: relationship to gadolinium and response to photopheresis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(8):1025–30. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilliet M, Cozzio A, Burg G, et al. Successful treatment of three cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with extracorporeal photopheresis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(3):531–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron PW, Cantos K, Hillebrand DJ, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy after liver transplantation successfully treated with plasmapheresis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25(3):204–9. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung HJ, Chung KY. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: response to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(3):596–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kafi R, Fisher GJ, Quan T, et al. UV-A1 phototherapy improves nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(11):1322–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.11.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yerram P, Saab G, Karuparthi PR, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a mysterious disease in patients with renal failure--role of gadolinium-based contrast media in causation and the beneficial effect of intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):258–63. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03250906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman LE. Diffuse fasciitis with hypergamaglobulinemia and eosinophilia: a new syndrome? J Rheumatol. 1974;1(suppl 1):46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodnan GP, DiBartolomeo AG, Medsger TA, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: report of seven cases of a newly recognized scleroderma-like syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1975;18(422):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988;17(4):221–31. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(88)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grisanti MW, Moore TL, Osborn TG, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis in children. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1989;19(3):151–7. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(89)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabuenca JM. Toxic-allergic syndrome caused by ingestion of rapeseed oil denatured with aniline. Lancet. 1981;2(8246):567–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90949-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slutsker L, Hoesly FC, Miller L, et al. Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome associated with exposure to tryptophan from a single manufacturer. JAMA. 264(2):213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toquet C, Hamidou MA, Renaudin K, et al. In situ immunophenotype of the inflammatory infiltrate in eosinophilic fasciitis. J Rheumatol. 30(8):1811–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viallard JF, Taupin JL, Ranchin V, et al. Analysis of leukemia inhibitory factor, type 1 and type 2 cytokine production in patients with eosinophilic fasciitis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dziadzio L, Kelly EA, Panzer SE, et al. Cytokine abnormalities in a patient with eosinophilic fasciitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(4):452–5. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kariyawasam HH, Robinson DS. The eosinophil: the cell and its weapons, the cytokines, its locations. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27(2):117–27. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birkland TP, Cheavens MD, Pincus SH. Human eosinophils stimulate DNA synthesis and matrix production in dermal fibroblasts. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286(6):312–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00402221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahari VM, Heino J, Niskanen L, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis. Increased collagen production and type I procollagen messenger RNA levels in fibroblasts cultured from involved skin. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126(5):613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granter SR, Barnhill RL, Hewins ME, et al. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi in diffuse fasciitis with peripheral eosinophilia: borrelial fasciitis. JAMA. 1994;272(16):1283–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashimoto Y, Takahashi H, Matsuo S, et al. Polymerase chain reaction of Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin gene in Shulman syndrome. Dermatology. 192(2):136–9. doi: 10.1159/000246339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anton E. Failure to demonstrate Borrelia burgdorferi-specific DNA in lesions of eosinophilic fasciitis. Histopathology. 2006;49(1):88–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endo Y, Tamura A, Matsushima Y, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: report of two cases and a systematic review of the literature dealing with clinical variables that predict outcome. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(9):1445–51. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bielsa I, Ariza A. Deep morphea. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26(2):90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia VP, de Quiros JF, Caminal L. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with eosinophilic fasciitis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(9):1864–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachmeyer C, Monge M, Dhote R, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis following idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune hemolytic anemia and Hashimoto’s disease. Dermatology. 199(3):282. doi: 10.1159/000018271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Junca J, Cuxart A, Tural C, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 1994;52(5):304–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1994.tb00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eklund KK, Anttila P, Leirisalo-Repo M. Eosinophilic fasciitis, myositis and arthritis as early manifestations of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32(6):376–7. doi: 10.1080/03009740410005061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khanna D, Verity A, Grossman JM. Eosinophilic fasciitis with multiple myeloma: a new haematological association. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(12):1111–2. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.12.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moulton SJ, Kransdorf MJ, Ginsburg WW, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: spectrum of MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(3):975–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.3.01840975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antic M, Lautenschlager S, Itin PH. Eosinophilic fasciitis 30 years after - what do we really know? Report of 11 patients and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2006;213(2):93–101. doi: 10.1159/000093847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(2):273–81. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.111630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pomann JJ, Rudner EJ. Scleromyxedema revisited. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(1):31–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark BJ, Mowat A, Fallowfield ME, et al. Papular mucinosis: is the inflammatory cell infiltrate neoplastic? The presence of a monotypic plasma cell population demonstrated by in situ hybridization. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(3):467–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrarini M, Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, et al. Scleromyxedema serum increases proliferation but not the glycosaminoglycan synthesis of dermal fibroblasts. J Rheumatol. 1989;16(6):837–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harper RA, Rispler J. Lichen myxedematosus serum stimulates human skin fibroblast proliferation. Science. 1978;199(4328):545–7. doi: 10.1126/science.622555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacy MQ, Hogan WJ, Gertz MA, et al. Successful treatment of scleromyxedema with autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(10):1277–82. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.10.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shergill B, Orteu CH, McBride SR, et al. Dementia associated with scleromyxoedema reversed by high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(3):650–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berger JR, Dobbs MR, Terhune MH, et al. The neurologic complications of scleromyxedema. Medicine (Baltimore ) 2001;80(5):313–9. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nieves DS, Bondi EE, Wallmark J, et al. Scleromyxedema: Successful treatment of cutaneous and neurologic symptoms. Cutis. 2000;65(2):89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Godby A, Bergstresser PR, Chaker B, et al. Fatal scleromyxedema: report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2):289–94. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70567-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Webster GF, Matsuoka LY, et al. The association of potentially lethal neurologic syndromes with scleromyxedema (papular mucinosis) J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(1):105–8. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70021-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Majeski C, Taher M, Grewal P, et al. Combination oral prednisone and intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of scleromyxedema. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005;9(3):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s10227-005-0137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feldman P, Shapiro L, Pick AI, et al. Scleromyxedema. A dramatic response to melphalan. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99(1):51–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.99.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris RB, Perry HO, Kyle RA, et al. Treatment of scleromyxedema with melphalan. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115(3):295–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Helm F, Helm TN. Iatrogenic myelomonocytic leukemia following melphalan treatment of scleromyxedema. Cutis. 1987;39(3):219–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gabriel SE, Perry HO, Oleson GB, et al. Scleromyxedema: a scleroderma-like disorder with systemic manifestations. Medicine (Baltimore ) 1988;67(1):58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuldeep CM, Mittal AK, Gupta LK, et al. Successful treatment of scleromyxedema with dexamethasone cyclophosphamide pulse therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71(1):44–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.13787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rongioletti F, Hazini A, Rebora A. Coma associated with scleromyxoedema and interferon alfa therapy. Full recovery after steroids and cyclophosphamide combined with plasmapheresis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(6):1283–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saigoh S, Tashiro A, Fujita S, et al. Successful treatment of intractable scleromyxedema with cyclosporin A. Dermatology. 2003;207(4):410–1. doi: 10.1159/000074127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sansbury JC, Cocuroccia B, Jorizzo JL, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant scleromyxedema with thalidomide in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(1):126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Caradonna S, Jacobe H. Thalidomide as a potential treatment for scleromyxedema. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(3):277–80. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, Menne T. Successful treatment of scleromyxedema using thalidomide. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(10):1396–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacob SE, Fien S, Kerdel FA. Scleromyxedema, a positive effect with thalidomide. Dermatology. 2006;213(2):150–2. doi: 10.1159/000093856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amini-Adle M, Thieulent N, Dalle S, et al. Scleromyxedema: successful treatment with thalidomide in two patients. Dermatology. 2007;214(1):58–60. doi: 10.1159/000096914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iranzo P, Lopez-Lerma I, et al. Scleromyxoedema treated with autologous stem cell transplantation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(1):129–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Donato ML, Feasel AM, Weber DM, et al. Scleromyxedema: role of high-dose melphalan with autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;107(2):463–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Illa I, de la Torre C, Rojas-Garcia R, et al. Steady remission of scleromyxedema 3 years after autologous stem cell transplantation: an in vivo and in vitro study. Blood. 2006;108(2):773–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lister RK, Jolles S, Whittaker S, et al. Scleromyxedema: response to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (hdIVIg) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2):403–8. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.104001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Righi A, Schiavon F, Jablonska S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins control scleromyxoedema. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(1):59–61. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kulczycki A, Nelson M, Eisen A, et al. Scleromyxoedema: treatment of cutaneous and systemic manifestations with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Br J Dermatol. 2003 Dec;149(6):1276–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wojas-Pelc A, Blaszczyk M, Glinska M, et al. Tumorous variant of scleromyxedema. Successful therapy with intravenous immunoglobulins. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(4):462–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greenberg LM, Geppert C, Worthen HG, et al. Scleredema “adultorum” in children. Report of three cases with histochemical study and review of world literature. Pediatrics. 1963;32:1044–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sattar MA, Diab S, Sugathan TN, et al. Scleroedema diabeticorum: a minor but often unrecognized complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1988;5(5):465–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1988.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vijayasingam SM, Thai AC, Chan HL. Non-infective skin associations of diabetes mellitus. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1988;17(4):526–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6(2):189–92. doi: 10.2337/diacare.6.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tate BJ, Kelly JW, Rotstein H. Scleredema of Buschke: a report of seven cases. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37(3):139–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1996.tb01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Fujita H, et al. Square-shaped scleredema in the back: probably induced by mechanical stress. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(9):769–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ranganathan P. Infliximab-induced scleredema in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11(6):319–22. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000191162.66288.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35(6):355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kovary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. Observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117(9):536–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1981.01650090018016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ratip S, Akin H, Ozdemirli M, et al. Scleredema of Buschke associated with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(2):450–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leung CS, Chong LY. Scleredema in chinese patients: a local retrospective study and general review. Hong Kong Med J. 1998;4(1):31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ioannidou DI, Krasagakis K, Stefanidou MP, et al. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke presenting as periorbital edema: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2 Suppl 1):41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ulmer A, Schaumburg-Lever G, et al. Scleredema adultorum Buschke. Case report and review of the literature. Hautarzt. 1998;49(1):48–54. doi: 10.1007/s001050050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wright RA, Bernie H. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke with upper esophageal involvement. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77(1):9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paz RA, Badra RE, Marti HM, et al. Systemic Buschke’s scleredema with cardiomyopathy, monoclonal IgG kappa gammopathy and amyloidosis. Case report with autopsy. Medicina (B Aires) 1998;58(5 Pt 1):501–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Livieri C, Monafo V, Bozzola M, et al. Buschke’s scleredema and carditis: a clinical case. Pediatr Med Chir. 1982;4(6):695–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rho YW, Suhr KB, Lee JH, et al. A clinical observation of scleredema adultorum and its relationship to diabetes. J Dermatol. 1998;25(2):103–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Venencie PY, Powell FC, Su WP, et al. Scleredema: a review of thirty-three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(1):128–34. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Harati A, et al. Failure of low-dose methotrexate in the treatment of scleredema diabeticorum in seven cases. Dermatology. 2005;211(3):299–301. doi: 10.1159/000087031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nakajima K, Iwagaki M, Ikeda M, et al. Two cases of diabetic scleredema that responded to PUVA therapy. J Dermatol. 2006;33(11):820–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tuchinda C, Kerr HA, Taylor CR, et al. UVA1 phototherapy for cutaneous diseases: an experience of 92 cases in the United States. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22(5):247–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2006.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eberlein-Konig B, Vogel M, Katzer K, et al. Successful UVA1 phototherapy in a patient with scleredema adultorum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(2):203–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Grundmann-Kollmann M, Ochsendorf F, Zollner TM, et al. Cream PUVA therapy for scleredema adultorum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(5):1058–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hager CM, Sobhi HA, Hunzelmann N, et al. Bath-PUVA therapy in three patients with scleredema adultorum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 1):240–2. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stables GI, Taylor PC, Highet AS. Scleredema associated with paraproteinaemia treated by extracorporeal photopheresis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(4):781–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Konemann S, Hesselmann S, Bolling T, et al. Radiotherapy of benign diseases-scleredema adultorum Buschke. Strahlenther Onkol. 2004;180(12):811–4. doi: 10.1007/s00066-004-1286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bowen AR, Smith L, Zone JJ. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke treated with radiation. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(6):780–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.6.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tobler M, Leavitt DD, Gibbs FA., Jr Dosimetric evaluation of a specialized radiotherapy treatment technique for scleredema. Med Dosim. 2000;25(4):215–8. doi: 10.1016/s0958-3947(00)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kay J. Imatinib mesylate treatment improves skin changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):S64. doi: 10.1002/art.23696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]