Abstract

Simple polyglutamine (polyQ) peptides aggregate in vitro via a nucleated growth pathway directly yielding amyloid-like aggregates. We show here that the 17 amino acid flanking sequence (httNT) N-terminal to the polyQ in the toxic huntingtin exon1 fragment imparts onto this peptide a complex alternative aggregation mechanism. In isolation the httNT peptide is a compact coil that resists aggregation. When polyQ is fused to this sequence, it induces in httNT, in a repeat-length dependent fashion, a more extended conformation that greatly enhances its aggregation into globular oligomers with httNT cores and exposed polyQ. In a second step, a new, amyloid-like aggregate is formed with a core composed of both httNT and polyQ. The results indicate unprecedented complexity in how primary sequence controls aggregation within a substantially disordered peptide, and have implications for the molecular mechanism of Huntington's disease.

There are nine known expanded CAG repeat diseases, in which expansion of a disease protein's polyglutamine (polyQ) sequence beyond a threshold repeat length causes progressive neurodegeneration through a predominantly gain-of-function mechanism 1. In Huntington's disease (HD) the repeat length threshold is about 37 glutamines 2. A major challenge to understanding disease mechanisms has been to discover physical properties of polyQ proteins that exhibit repeat length dependence in this threshold regime, and that therefore might serve as a link in the progression from genetics to disease. PolyQ-containing aggregates are ubiquitously observed in these diseases 1, and aggregation rates of polyQ sequences increase as repeat length increases 3, mirroring correlations between repeat length and disease risk and age of onset 1. These observations led to the hypothesis that repeat-length dependent aggregation of polyQ is the triggering event in the mechanism of expanded CAG repeat diseases.

Not all data support this hypothesis, however. In particular, in cell and animal models disease progression is not always correlated with aggregate burden as measured by inclusions revealed by light microscopy 4. There are also inconsistent reports of the nature of polyQ aggregates. Thus, while simple polyQ peptides follow a nucleated growth polymerization mechanism with direct formation of amyloid-like aggregates 3,5-8, aggregation products of the polyQ-containing disease protein huntingtin (htt) exon1 include, in addition to amyloid fibrils 9, oligomeric and protofibrillar structures 10,11 that many feel are more relevant to disease pathology 12.

Although the human huntingtin (htt) gene encodes a protein of over 3,500 amino acids, expression of the first exon of the gene in cell and animal models is sufficient to replicate much of HD pathology 1, and there is growing evidence that proteolytic release of a fragment containing exon1 is required for toxicity 13. The amino acid sequence of the translation product of human htt exon1, which includes the polyQ sequence, is shown in Table 1. Since polyQ repeats are the only apparent common feature of the nine expanded polyQ repeat disease proteins 1, we have extensively studied a series of simple polyQ peptides that contain flanking Lys residues added for solubility 5-8,14. We found that these peptides aggregate via a nucleated growth polymerization mechanism in which the critical nucleus is a rarely populated form of the monomer 5-8. In these peptides, increases in aggregation rates for longer polyQ repeat length peptides are associated with more favorable equilibrium constants for nucleus formation 5. We also showed previously that the proline-rich flanking sequence on the C-terminal side of the polyQ in exon1 reduces aggregation kinetics and aggregate stability, but does not fundamentally change the aggregation mechanism 14. Its effect is also directional; oligoPro added to the N-terminus of polyQ has no impact on aggregation 14.

Table 1.

Amino acid sequences of exon1 related peptides.

| Name or identifier | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Human htt exon 1 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- PPPPPPPPPP-Htt-Ca |

| Q15 | KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- ---------- ---------- KK |

| Q20 | KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- KK |

| Q29 | KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQ- ---------- KK |

| Q30 | KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- KK |

| Q35 | KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- KK |

| Q35P10 | KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTQ35 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- KK |

| Q35httNT | KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF |

| httNT | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF-amide |

| httNTQ3(F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQ |

| FRET-httNTQ3 | ¥ATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQ |

| httNTQ15(F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- ---------- ---------- KK |

| httNTQ25(F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQ----- ---------- KK |

| httNTQ30P6 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- PPPPPP---- KK |

| httNTQ30P6(F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- PPPPPP---- KK |

| httNTQ20P10 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTQ20P10(F->A) | MATLEKLMKA AESLKSA--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTQ20P10(M->O) | OATLEKLOKA FESLKSF--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTQ20P10(F->A/M->O) | OATLEKLOKA AESLKSA--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTQ20P10(F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTQ20P10(F11W) | MATLEKLMKA WESLKSF--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| FRET-httNTQ20P10 | ¥ATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ ---------- ---------- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTQ37P10(F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQ--- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| FRET-httNTQ37P10 | ¥ATLEKLMKA FESLKSW--- QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQ--- PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| httNTK2Q36 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF-KK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQ---- KK |

| Biotinyl-Q29 | BKK QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQ- ---------- KK |

Htt-C = PQLPQPPPQA QPLLPQPQPP PPPPPPPPGP AVAEEPPLHR P; ¥ = nitroTyr; O = methionine sulfoxide; B = biotin

Intrigued by these oligoproline effects, we turned our attention to the 17 amino acid sequence at the N-terminus of the huntingtin protein, just upstream from the polyQ segment. In this paper, we describe detailed analysis of the in vitro aggregation mechanism of chemically synthesized peptide models for human huntingtin exon1 that include this 17 amino acid sequence (httNT). We show that addition of httNT to polyQ causes dramatic changes in the aggregation mechanism, intermediates and products. We also show that this behavior is grounded in a kind of reciprocal crosstalk between the polyQ and httNT segments, both of which are intrinsically unfolded protein sequences 15. This work reveals a complex pathway featuring a variety of aggregate structures, and suggests an unanticipated degree of conformational communication between adjacent disordered elements in intrinsically unfolded protein sequences. This data is consistent with previous reports showing modulation of polyQ aggregation by flanking sequences in general 16-21 and the huntingtin N-terminus in particular 22,23.

RESULTS

The role of the htt N-terminus in exon1 aggregation

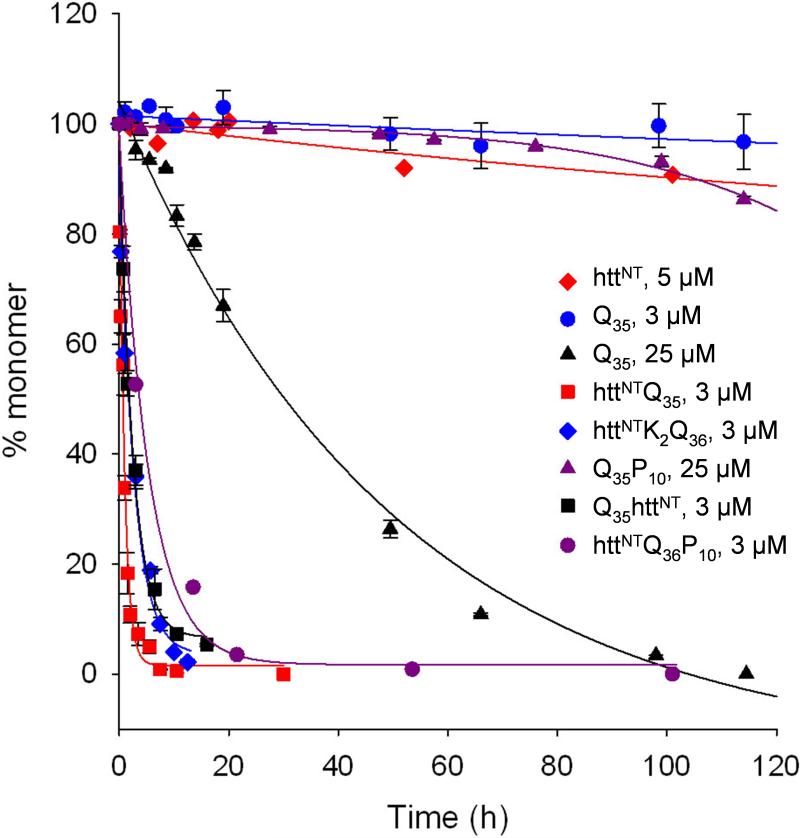

To explore possible effects of the htt exon1 N-terminal 17 amino acids on polyQ aggregation, we generated the peptide httNTQ35 (Table 1), subjected it to a disaggregation procedure required to ensure the absence of preexisting aggregates 24, and studied its aggregation in PBS buffer at 37 °C. We found that 3 μM httNTQ35 undergoes aggregation significantly (p < 0.001 at t = 10.5 h) more rapidly than 3 μM Q35 (Fig. 1A). In addition, the peptide httNTQ36P10 aggregates somewhat less rapidly than httNTQ35 but much more rapidly than Q35 (Fig. 1A); this shows that while the aggregation suppressing ability of oligoPro also operates within the exon1 context, the enhancing effect of httNT is dominant over the suppressing effect of oligoPro. As discussed above, oligoPro placed C-terminal to polyQ diminishes aggregation rate compared with polyQ (compare 25 μM Q35P10 with 25 μM Q35 in Fig. 1A), but placed N-terminal to polyQ has no effect (not shown) 14. In contrast, the httNT effect does not appear to depend on where the httNT is placed. Thus, Q35httNT exhibits an aggregation rate that is much faster than that of Q35 and not significantly (p > 0.01 at 0.75 h) different to that of httNTQ35 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Aggregation kinetics of huntingtin exon1 mimic peptides exploring a variety of polyQ repeat lengths. (A) Basic httNT effect: HPLC sedimentation assay following aggregation of httNT (5 μM, R2=0.746, S.D.= ± 2.3), httNTQ35 (3 μM, R2=0.986, S.D.= ± 4.6), Q35 (25 μM, R2=0.993, S.D.= ± 3.8; 3 μM, R2=0.688, S.D.= ± 1.8), Q35httNT (3 μM, R2=0.996, S.D.= ± 3.0), httNTQ36P10 (3 μM, R2=0.992, S.D.= ± 4.3), Q35P10 (25 μM, R2=0.973, S.D.= ± 0.8), httNTK2Q36 (3 μM, R2=0.981, S.D.= ± 1.0); (B) Role of polyQ repeat length on 5 μM peptides. HPLC sedimentation assay following aggregation of httNT (R2=0.746, S.D.= ±2.3), httNTQ3 (F17W) (R2=0.966, S.D.= ±2.1), httNTQ15 (F17W) (R2=0.971, S.D.= ± 3.2), httNTQ25 (F17W) (R2=0.992, S.D.= ± 3.3), httNTQ35 (R2=0.993, S.D.= ± 4.3); (C) Role of httNT mutations in a httNTQ20P10 peptides (see Table 1) incubated at ∼ 6 μM: wild type httNT (R2=0.992, S.D.= ±3.1); F17W (R2=0.997, S.D.= ±2.1); F11W (R2=0.991, S.D.= ±3.7); F11A / F17A (R2=0.987, S.D.= ±2.5); M1X / M8X (R2=0.998, S.D.= ±1.4); M1X / M8X / F11A / F17A (R2=0.628, S.D.= ±3.5); (D) Role of httNT sequence in nucleation of aggregation: concentration dependence of early aggregation rates for Q30 (slope = 2.57, R2=0.9987, S.D. = ±0.026) and httNTQ30P6 (slope = 1.20, R2=0.9445, S.D. = ±0.150). All reactions were conducted in PBS at 37 °C. X = methionine sulfoxide.

In spite of the apparent dominant effect by the httNT sequence, the kinetics of a series of httNTQN peptides continues to exhibit a strong polyQ repeat length dependence, as shown previously for both simple polyQ peptides 25 and for recombinantly produced exon1 peptides 9. Thus, while httNT, httNTQ3, and httNTQ15 all aggregate sluggishly, httNTQ25 aggregates over a period of 1−2 days and, as discussed above, httNTQ35 aggregates within a few hours (Fig. 1B). Although some of these peptides examined in Figure 1B contain a Phe17->Trp mutation to allow certain fluorescence experiments (described below), this mutation does not appreciably affect aggregation properties. Control experiments in an httNTQ20P10 background show that replacement of either Phe11 or Phe17 with Trp in the httNT segment yields aggregation kinetics very similar to those of the corresponding wild type peptide (Fig. 1C).

Previously, we found that early stages of the aggregation of simple polyQ peptides exhibit a modest concentration dependence consistent with a nucleated growth polymerization mechanism and a critical nucleus of one 5, as shown for Q30 in Figure 1D. In contrast, the initial stages of aggregation of the exon1 related sequence httNTQ30P6 (previously we found no appreciable difference between a Pro6 and a Pro10 sequence 14) yields a log-log plot of initial kinetics vs. concentration (Fig. 1D) 5 with a slope of approximately 1, corresponding to a calculated critical nucleus (n*) of about −1. The n* = −1 value indicates a rate - concentration relationship for the early aggregation kinetics of httNTQ30P6 that is consistent with a nonnucleated, “downhill” aggregation mechanism 26 for oligomer formation, without a kinetic barrier to spontaneous aggregation. This analysis suggests that polyQ peptides containing the httNT sequence spontaneously aggregate by an entirely different mechanism than simple polyQ peptides, a conclusion that is further supported by additional data presented below.

Previously, we found that when simple polyQ monomers undergo spontaneous aggregation in aqueous solution, the earliest observable aggregates have fibril-associated properties similar to those of the final product 5. In contrast, electron micrographs show that the initial products in the aggregation of httNTQ30P6 are oligomeric and protofibrillar (Fig. 2). Later in the time course, various other aggregated structures appear that are more fibril-like (Fig. 2). A relationship between the formation of such oligomeric products and non-nucleated, downhill aggregation kinetics (Fig. 1D) fitting a classical colloidal coagulation model has been suggested previously for other protein aggregation reactions 27,28.

Figure 2.

Electron micrographs of various httNT-related aggregates. httNTQ30P6 was incubated in PBS at 37 °C and sampled at 0 hrs (A), 15 mins (B), 2.5 hrs (C, D, E), 5.5 hrs (F, G), 24 hrs (H, I), 48 hrs (J) and 100 hrs (K). httNTQ3 (F17W) was incubated in PBS at 37 °C for 800 hrs (L). All samples were transferred directly from reaction mixture to freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated grids and stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Scale bar = 50 nm.

HttNT conformation and exon1 aggregation kinetics

There are a number of possible explanations for the aggregation-enhancing ability of the httNT sequence. (I.) Since addition of lysine residues to a sequence sometimes discourage aggregation 29, httNT might enhance exon1 aggregation compared to our simple polyQ peptides because it replaces the Lys-Lys pair at the N-terminus of the model polyQ peptides (see introduction and Table 1). However, the aggregation kinetics of 3 μM httNTK2Q35, an exon1 analog containing a Lys-Lys pair inserted between httNT and Q35, are not significantly (p > 0.01 at 0.3 h) different from the kinetics of 3 μM httNTQ35 while at the same time are significantly (p < 0.001 at t = 10.5 h) faster than the kinetics of 3 μM Q35 (Fig. 1A). In addition, mutations that reduce hydrophobic character of httNT without altering charged residues abrogate the rapid aggregation kinetics in an exon1 peptide (Fig. 1C), confirming that the httNT segment provides some positive, sequence-specific contribution to aggregation, rather than simply replacing a Lys-Lys aggregation suppressor. (II.) An obvious alternative possibility is that httNT itself might be highly aggregation-prone. Surprisingly, however, we found that a peptide consisting solely of the httNT sequence aggregates sluggishly under our standard conditions (Figs. 1A, 1B). (III.) Another possible explanation is that the combination of all or part of httNT with the first portion of the polyQ sequence might create a new aggregation sequence motif with much more robust aggregation kinetics than either polyQ or httNT alone. However, httNT peptides containing short to intermediate lengths of polyQ also aggregate very slowly (Fig. 1B), and robust aggregation kinetics ensue for longer polyQ constructs even when httNT is attached to polyQ C-terminus (Fig. 1A), which creates an entirely different sequence at the Qn-httNT junction; these data suggest that polyQ abutted to httNT does not simply create a powerful, novel, linear aggregation motif. The httNTK2Q35 data (Fig. 1A) also argues against a novel aggregation motif, since if there were such a motif, at the junction of the httNT and polyQ sequences, the highly charged Lys-Lys insertion would be expected to disrupt it. (IV.) It is also possible that the httNT sequence might normally exist as a well-behaved oligomeric species, such as a dimer or trimer, which could accelerate aggregation by concentrating and/or orientating the polyQ elements. However, size exclusion chromatography (SEC) mobility shows that the httNT peptide migrates as a monomer (Fig. 3), while SEC elution profiles (not shown) show no evidence of higher assembly states. Likewise, circular dichroism (CD) spectra of httNT do not change with respect to concentration (Fig. 4A), consistent with a non-associating system. (V.) Another possibility is that, in analogy to a recent report of the ability of expanded polyQ to destabilize a folded protein domain 20, the httNT segment may exist in a folded and/or compact state that resists aggregation, but unfolds or extends when attached to expanded polyQ, enhancing its aggregation; disruption of the folded state is a common trigger for globular protein aggregation 30. This last hypothesis was explored in detail, as described next.

Figure 3.

State of expansion of the httNT peptide in solution. (A) Fractional migration (Kav) versus log MW of various peptides in size exclusion chromatography. The straight line is fitted to the Kav values for the simple polyQ peptides Q15, Q20, Q29, and Q35. α-helix-rich peptide Bal 31 and the polyproline type II rich peptide Pro14 are extended. Insulin (“Ins”), aprotinin (“Apr”), and httNT are relatively compact. (B) Average httNT end-to-end separation calculated from FRET measurements for mutants FRET-httNTQ3, FRET-httNTQ20P10, and FRET-httNTQ37P10, compared with their F17W analogs. Also included is the value for FRET-httNTQ3 studied in 6M urea in PBS. The dotted line shows the average end-to-end distance (34.5 ± 4 Å) between residues 1 and 17 calculated from polymer theory for a peptide in statistical coil. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of each measurement with respect to that for httNTQ3 in PBS (*, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Concentration dependent circular dichroism spectra of httNT. (A) httNT in aqueous buffer (see Methods) at 35 °C in concentrations of 3.8 μM (———),7.5 μM (······), and 18.9 μM (------). ContinLL 58 predicts significant secondary structure: 12% unordered, 4% β-strand, 20% turn, 8% polyproline type II helix, and 55% α-helix. (B) httNT in the presence of 10% trifluoroethanol (TFE) at 37 °C in concentrations of 7.5 μM (———), 18.9 μM (······), 94 μM (------). In the presence of this relatively low TFE concentration, the httNT adopts an α-helical structure, as evidenced by the negative bands at 208 and 222nm. The development of structure is protein concentration dependent, suggesting an oligomeric state under these conditions.

Arguing against this postulated polyQ-induced unfolding mechanism for the httNT effect is the fact that most peptides the size of httNT do not fold into stable, globular structures, but rather are disordered. Interestingly, however, analytical SEC suggests that the httNT sequence is actually relatively compact in solution. A series of simple polyQ peptides yield migration rates in SEC that fit a straight line (Fig. 3A). As expected, peptides that are predicted to be extended and thus have larger hydrodynamic radii, such as an Ala-rich peptide strongly favoring α-helix 31, and a Pro14 peptide favoring polyproline type II helix 32, migrate faster than equivalent length polyQ peptides. Insulin and aprotinin, which exhibit smaller hydrodynamic radii caused by their compact structures, migrate – as expected - more slowly than the equivalent length polyQ peptides. Within this dataset, the httNT peptide also migrates significantly more slowly for a peptide of its molecular weight, suggesting that– like insulin and aprotinin – httNT has a relatively small hydrodynamic radius.

To confirm the compactness of the httNT peptide, we conducted a fluorescence-based resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiment in which we replaced Met1 of httNT with the resonance energy acceptor, nitro-Tyr, and Phe17 with the resonance energy donor Trp 33, in the context of an httNTQ3 sequence (“FRET-httNTQ3”). Compared with httNTQ3 containing only the F17W replacement, the Trp fluorescence of the FRET-httNTQ3 peptide decreases by about 50% (data not shown), corresponding to a calculated average separation between donor and acceptor groups of 24 ± 0.5 Å (Fig. 3B). This is significantly shorter than the average end-to-end distance of 34.5 ± 4 Å calculated 34 for a 17-residue peptide in an extended statistical coil conformation. This theoretical value is supported by a FRET analysis of the httNTQ3 peptide in 6 M urea, which yields a separation of 33.9 ± 0.5 Å (Fig. 3B). Thus, in agreement with the SEC data, httNT in the httNTQ3 context in native buffer appears to be significantly collapsed.

Given this evidence for a collapsed structure in an isolated httNT peptide, we investigated whether it was possible for expanded polyQ sequences to disrupt that collapsed state in peptides dissolved in PBS. We found that for the FRET-exon1 mimic peptide containing a Q20 repeat, the average separation between nitro-Tyr and Trp in the httNT sequence does not significantly change (p > 0.01). However, the corresponding separation for the Q37 repeat peptide expands to 32 ± 1 Å (p < 0.01), a value approaching the 34 Å range obtained both by measurement of httNTQ3 in urea and by calculation based on an assumed statistical coil configuration (Fig. 3B). The data is thus consistent with a mechanism in which the httNT segment of exon1 is normally in a collapsed state that is resistant to aggregation, but that when connected to an expanded polyQ sequence becomes extended and labile to aggregation - an effect analogous to what has previously been observed for a globular protein 20.

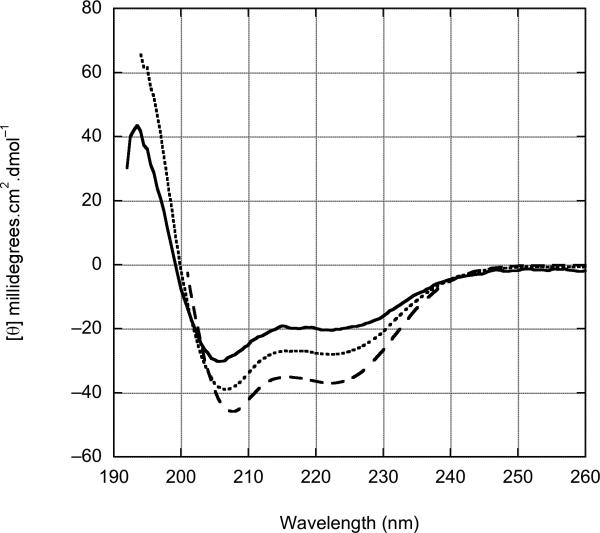

HttNT has no stable secondary structure

Although several features of the above results are consistent with httNT (in the absence of a connected expanded polyQ) being a compact domain, the short length of httNT makes it unlikely (but not impossible) that it possesses a unique, folded structure. To probe httNT secondary and tertiary structure, we applied two solution methods. The first, CD spectral analysis, proved equivocal. The CD spectrum of httNT at 35 °C (Fig. 4A) and the 35 °C – 5 °C difference spectrum (not shown) lack strong secondary structure features, suggesting the absence of a stable structure. At the same time, deconvolution analysis of the 35 °C spectrum predicts significant α-helix (see legend, Fig. 4), consistent with projections based on amino acid sequence 23,35. This interpretation of the CD spectrum is problematic, however, since the protein datasets used in programs like ContinLL are thought to be not suitable for deconvoluting CD spectra of short peptides 36.

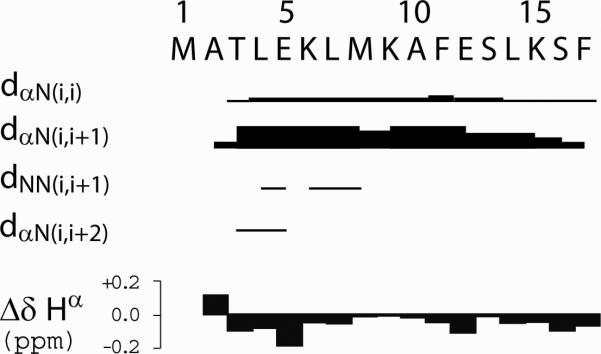

The CD dichotomy was clarified by high resolution NMR analysis (Fig. 5), which strongly suggests the absence of stably folded structure. Two-dimensional proton TOCSY and NOESY NMR analyses show that httNT adopts predominantly unfolded, random-coil conformations, characterized by small spectral dispersion, small secondary chemical shifts, and strong sequential Hα(i)-HN(i+1) NOEs with few sequential HN(i)-HN(i+1) or medium-range NOEs. A single, very weak, medium-range NOE cross-peak is observed connecting the Thr3 Hα and Glu5 HN protons (Fig. 5B). The region around these residues shows the largest negative Hα secondary chemical shifts and exhibits the most HN(i)-HN(i+1) NOE cross-peaks (Fig. 5A), which indicates transient existence of a few residues in the α-helix quadrant of Φ,Ψ space. Despite this slight propensity, there is clearly no stable α-helix in this peptide in solution under physiological conditions.

Figure 5.

Proton NMR analysis of httNT. (A) Summary of NOE and secondary 1H chemical shift (Δδ Hα) data observed for httNT at 800 MHz, 5 °C in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2. The relative intensities of the inter-proton NOEs dαN(i,i), dαN(i,i+1), dNN(i,i+1), dNN(i,i) and dαN(i,i+2) are depicted by the thickness of the lines. The Hα secondary chemical shift values of httNT (Δδ Hα) were calculated by subtracting random coil values 54 from the Hα chemical shifts of httNT; (B) 2D proton TOCSY and NOESY NMR spectra. Superposition of the Hα-HN (top) and HN-HN (bottom) regions of the TOCSY (black) and NOESY (red) spectra illustrate sequential dαN(i,i+1) and dNN(i,i+1) connectivities. The intra-residue Hα(i)-HN(i) cross-peaks are labeled with residue name and number and sequential Hα(i)-HN(i+1) and HN(i)-HN(i+1) NOE cross-peaks are connected for consecutive residues. The only observed, very small non-sequential Hα(i)-HN(i+2) NOE cross-peak connecting Thr3 Hα and Glu5 HN protons is marked with a red circle and labeled in red in the top panel.

Thus, in the absence of an expanded polyQ, httNT adopts a conformation lacking significant secondary and tertiary structural features, while at the same time being in a collapsed state. Results from the sequence analysis algorithm PONDR are consistent with this, predicting (Fig. 6) the httNT sequence to be a molecular recognition feature (MoRF) 37 capable of engaging in coupled folding and binding interactions 15. Such sequences tend to be collapsed coils in native buffer 15, often taking up α-helical conformations when complexed with their binding partners. Consistent with this, httNT has essentially no α-helix in isolation (see above) but takes on significant α-helix in the presence of low concentrations of trifluoroethanol as revealed by CD (Fig. 4B).

Figure 6.

PONDR analysis of the first 600 amino acids of the human huntingtin sequence. Segments with low PONDR scores are predicted to be stably folded, and high scores (near 1) disordered. Short segments spiking below a PONDR score of 0.5 are predicted to be MoRFs (see text). Calculated using the VX-LT version of PONDR. Access to PONDR® was provided by Molecular Kinetics (6201 La Pas Trail - Ste 160, Indianapolis, IN 46268; 317−280−8737; E-mail: main@molecularkinetics.com ). VL-XT is copyright©1999 by the WSU Research Foundation, all rights reserved. PONDR® is copyright©2004 by Molecular Kinetics, all rights reserved.

A multi-step aggregation mechanism

When the assembly of simple polyQ peptides into amyloid-like aggregates is monitored by multiple analytical techniques, the data from all measures track closely, suggesting the absence of reaction intermediates 5. In contrast, httNT-containing exon1 peptides exhibits different aggregation curves depending on the analytical method (Figs. 7 and 8). In particular, thioflavin T binding (Δ), commonly used for measuring amyloid-like structure 38, generates reaction curves that are delayed compared to the curves from the HPLC sedimentation (◆) and light scattering (○) assays (Fig. 7B, 8C). Thus, for the httNTQ30P6 peptide (Fig. 7) at 6.25 hrs, the difference between the ThT value (Δ) and the HPLC value (◆) is statistically significant (p < 0.01); at later time points (19 hrs, 120 hrs) the difference is insignificant (p > 0.01). The ThT lag followed by a burst suggests that the initial aggregates are not amyloid-like, while later aggregates are. FTIR analysis also suggests that the initial aggregation product is qualitatively different - exhibiting more coil and less β-structure - compared to aggregates isolated later in the time course (Fig. 8E). This is also consistent with the EM data (Fig. 2).

Figure 7.

Time course of aggregation of httNTQ30P6 (F17W) by multiple analyses. (A) Fluorescence emission maximum of Trp residue at position 17 in resuspended aggregates isolated from reaction of httNTQ30P6 (F17W) (■) or httNTQ3 (F17W) (Δ). The emission maximum of monomeric peptide (•) is plotted as being equivalent to that of initial aggregates, since this is the result obtained for the F17W mutant of the shorter, less rapidly aggregating httNTQ20P10. The httNT aggregation reaction was carried out to 800 hrs, at which time W17 remained completely solvent exposed (not shown). (B) Time course monitored by HPLC sedimentation assay (——◆——), R2=0.983, S.E.= ±6.0), thioflavin T fluorescence (——Δ——, R2=0.994, S.D.= ±3.9) and right angle light scattering (---○---, R2=0.983, S.D.= ±6.0). Inset, first 10 hrs. (C) Dot blots of httNTQ30P6 (F17W) time points using the antibody MW1. Top row: unfractionated aliquots of the reaction mixture (time in hrs; M = non-incubated monomer). Bottom row: equivalent masses of isolated aggregates (no material in the “M” column in this row).

Figure 8.

Time course of aggregation of httNTQ20P10 by multiple analyses. (A) Trypsin sensitivity of either monomer (t = 0) or aggregates isolated by centrifugation at either 42 or 700 hours (see Methods). (B) Properties of isolated aggregates: fluorescence emission maxima of Trp residues in the mutant peptides F11W (——•——, R2=0.994, S.D.= ±0.5) and F17W (····▲····, R2=0.916, S.D.= ±1.2); elongation rate constants for biotinyl-Q29 for isolated aggregates adherent to microtiter plate wells (---□---, R2=0.748, S.D.= ±0.19). (C) Overall aggregation kinetics of WT peptide monitored by the HPLC sedimentation assay (---◆---, R2=0.992, S.D.= ±3.1) and by ThT fluorescence (——Δ——, R2=0.974, S.D.= ±6.0). (D) Dot blot of non-incubated monomer (M) and isolated aggregates developed with to the anti-polyQ MW1 antibody. (E) Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of aggregates. Monomeric Q15 (a); aggregates of httNTQ20P10 (F17W) isolated at 45 hrs (b), 120 hrs (c), and 120 days (d); aggregates of httNTQ36P10 isolated at 7 days (e); aggregates of Q30 isolated at 30 days (f). Amide I frequency values normally assigned to secondary structural features 59 and Gln side chains 60 are shown with bars at the top of the panel.

Details of the structures of these intermediates are revealed by further analysis of httNTQ30P6 (Fig. 7) and httNTQ20P10 (Fig. 8) aggregates isolated from ongoing reactions. In particular, dot blot analysis of these aggregates show that polyQ in the initial aggregates is readily accessible to an antibody against a linear polyQ epitope, but is masked in the later aggregates (Figs. 7C, 8D). In addition, the initially formed aggregates are poor templates for recruiting polyQ-containing peptides, while the later, fibrillar aggregates are capable of seeding polyQ elongation (Fig. 8B). Seeding activity is a feature particularly associated with amyloid-like aggregates 39. Furthermore, while a Trp residue inserted for Phe at position 11 or 17 is solvent exposed both in the monomeric peptide and in the initial aggregates, it becomes less solvent accessible (based on its fluorescence maximum) as the aggregation reaction proceeds, with a time course that parallels the disappearance of polyQ antibody binding epitopes (Figs. 7A (■); 8B (•,▲)). In contrast, when the isolated httNT peptide itself slowly aggregates, the Trp residue of the F17W mutant remains fully solvent exposed in the aggregate fraction even after 800 hrs (Fig. 7A (Δ)); this is consistent with the apparently inability of aggregates of httNT lacking a long polyQ track to progress beyond the oligomer stage, in agreement with EM analysis (Fig. 2L). While the initial aggregates of httNTQN peptides appear to be less tightly packed than the later aggregates, they are sufficiently structured that they are protected from proteolyis by trypsin, in contrast to soluble, monomeric httNT (Fig. 8A).

Thus, the initial aggregates in this httNT mediated mechanism are non-fibrillar oligomers with their httNT segments composing the core, but their polyQ segments remaining unstructured and available for antibody binding. Subsequently, the polyQ elements also become integrated into the aggregate core structure, which takes on a more fibrillar character both in the polyQ and httNT elements. Growth into larger fibrillar assemblies, as seen in EM, take place at later incubation times. FTIR analysis (Fig. 8E) shows that the initial aggregates (before burial of Trp17) contain a significant amount of coil and turn conformations in addition to β-structure. Interestingly, FTIR spectra of all aggregates isolated after Trp17 burial feature a single β-sheet band at ∼1,626 cm−1 and are indistinguishable from each other and from aggregates of simple polyQ (Fig. 8E).

Critically, at a time when the major changes in aggregate structure are occurring, as evidenced by ThT binding, Trp fluorescence shift, FTIR, EM, and polyQ antibody binding, the vast bulk of the exon1 peptide (>80%) does not pellet after centrifugation (Figs. 7 and 8) and migrates as a single, monomeric (Fig. 3A) species in size exclusion chromatography (M. Jayaraman and R. Wetzel, unpublished data). Coincident with the timing of the changes in aggregate structure, there is a dramatic increase in the rate of monomer loss, suggesting that a nucleation event has occurred.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here are consistent with the model shown in Figure 9. In this model, the httNT peptide has an intrinsic tendency to collapse into an aggregation resistant compact coil state, but an attached, expanded polyQ sequence induces in this segment a more extended state. When the httNT sequence is extended, it become susceptible to formation of a metastable, micelle-like aggregate with the httNT segment making up the loosely packed core and the flanking polyQ sequence excluded from the core. While this initial aggregation reaction is non-nucleated, some of these loosely packed oligomers appear to give birth, through a stochastic process, to amyloid nuclei. With the emergence of amyloid fibril structure, the remaining monomeric fraction – which represents the vast majority of the exon1 molecules at the time when these postulated nucleation events are taking place – fuels the ongoing fibril elongation reaction. While many details of this proposed mechanism remain to be worked out, it appears that longer polyQ sequences favor aggregation in two ways: first, by disrupting the httNT compact coil and thereby facilitating initial httNT aggregation, and, second, by improving the efficiency of the nucleation events proposed to occur within this oligomer population.

Figure 9.

Mechanism of httNT mediated exon1 aggregation. The httNT domain (green) unfolds in a polyQ repeat length dependent fashion and, once unfolded, self-aggregates without a nucleation barrier to form oligomers with cores comprised of httNT and not polyQ (red). The next identified aggregates involve both httNT and polyQ in amyloid-like structure, while oligo Pro (black) is not incorporated into the core. This drawing is schematic and is not meant to imply any details of aggregate structure, except that final aggregates are rich in β-sheet, are fibrillar, and involve both httNT and polyQ. Although the initial formation of oligomers exhibits non-nucleated, downhill kinetics, it is likely that a nucleation event takes place stochastically within the oligomer population – as shown in brackets - to trigger rapid amyloid growth.

In many respects, the mechanism shown in Figure 9 resembles the “conformational conversion” model for spontaneous amyloid growth proposed for yeast prion amyloid formation 40. In that model, relatively loosely structured spherical oligomers form first, then convert into a more structured oligomer that can grow by recruiting other oligomers or monomers. In Figure 9, we envision that the nucleation process for exon1 aggregation consists of the stochastic rearrangement of some oligomers into amyloid-like structures capable of rapidly propagating via monomer addition. That is, although oligomers can readily dissociate back to monomers (M. Jayaraman and R. Wetzel, unpublished observations), the subpopulation of oligomers that successfully undergo the nucleation process appear to be required intermediates, under these experimental conditions, and therefore to be on-pathway 41 to amyloid formation. The kinetics of the only known alternative route to amyloid formation – the previously described 5 nucleated growth mechanism - are too slow to provide the observed rapid fibril formation (A. Thakur and R. Wetzel, Univ. Pittsburgh, unpublished data). This also is most consistent with oligomer formation being on-pathway. Providing further support for the scheme shown in Figure 9, and extracting details on the mechanism and kinetics of nucleation process as well as other assembly steps, are the focus of current work.

Amino acid sequence has been viewed as playing two major roles in influencing protein aggregation and amyloid formation 30. First, globular proteins become more amyloidogenic when their folded structures are destabilized, for example by point mutations. Second, amyloidogenic proteins possess specific primary sequence elements that constitute the core regions of the amyloid structure, and mutations within these regions can abrogate or enhance amyloid formation. Our studies on huntingtin exon1 aggregation, however, are revealing additional means by which sequence can influence aggregation rate. Recently we reported that an oligoproline sequence on the C-terminal side of a polyQ tends to decrease aggregation rate and aggregate stability, apparently by favoring more aggregation-resistant conformations 14. Here, we show that adjacent elements of intrinsically unfolded polypeptides can engage in an “aggregation two-step” in which one element supplies rapid initial aggregation kinetics (but is insufficient to form amyloid or provide stability) while a second, connected element (which in isolation aggregates relatively slowly) provides the means to a highly stable amyloid structure. In a further twist, we show that a degree of compactness in the unstructured httNT sequence provides protection against aggregation, and that the previously described destabilizing ability of a connected polyQ 20,42 disrupts this protective structure and opens the door to robust aggregation. Together, these results suggest that the rules by which primary sequences inform the direction and kinetics of protein aggregation may be much more complex than previously believed 29.

Perhaps 25% of the proteome consists of sequences that do not exist as ordered globular or fibrous structures, but rather are intrinsically unfolded 43. The results in this paper, together with our previous studies on the Pro-rich sequence of htt exon1 14, illustrate the dramatic effects on peptide conformation and aggregation imparted through subtle sequence effects within a single disordered polypeptide. In particular, the ability of disordered polyQ sequences to influence the folding stability of adjacent domains 20,42 is an unprecedented phenomenon in protein science whose limits, and still obscure mechanism, are yet to be elucidated. What is particularly surprising about our data on the effect of expanded polyQ on httNT is the implied ability of the compact coil state of httNT to resist aggregation; classically, compact but disordered “molten globule” states of globular proteins have been considered to be aggregation-prone 44. PolyQ destabilization of adjacent domains may account for the observation that longer polyQ tracts are often associated with reductions in protein activity 7, a trend suggesting the possibility that some loss-of-function 45 might accompany the toxic gain-of-function that is generally thought to dominate polyQ diseases.

We believe httNT derives its unusual impact on aggregation mechanism and rate due to its resemblance to MoRF sequences 37, which exist as condensed coils poised at the cusp of foldedness, designed by nature for coupled folding and binding processes in the cell 15. Although this designation for httNT is based solely on PONDR analysis (Fig. 6), the biophysical properties of httNT are entirely consistent with this notion, and htt is well known to possess many interaction partners 46.

Our results add to a growing literature on interactions between polyQ and its flanking sequences in aggregation reactions. After initial reports on the ability of flanking sequences to modulate aggregation of polyQ disease proteins in cells 47, a number of papers 16-19,21 appeared describing aggregation by a flanking sequence that facilitates aggregation of the polyQ portion, sometimes as a clearly defined initial step 19,21 and sometimes initiated by the destabilizing influence of an adjacent expanded polyQ 20.

Our results put into a molecular biophysics context several recent cell-based studies of the role of the httNT sequence in exon1 aggregation and toxicity. Using models in which exon1 fragments are expressed in mammalian or yeast cells, several groups have shown that the presence or absence of httNT, as well as mutations within or adjacent to httNT, introduce complex alterations in sub-cellular localization, aggregate formation, and/or cytotoxicity or growth retardation 22,23,35,48. Studies showing that binding of httNT by a specific immunoglobulin fragment inhibits exon1 aggregation and toxicity in several cell models 49 are consistent with our data showing that httNT aggregation is the first step in exon1 aggregation, and that this depends on destabilization of a compact state in httNT. Despite its lack of α-helical structure, the α-helix propensity of httNT (Fig. 4B) is consistent both with suggestions that httNT may mediate exon1 targeting to membrane fractions 23,35 and with our hypothesis that httNT is a MoRF sequence that mediates coupled folding and binding to protein targets. The ability of httNT to dramatically alter the polyQ aggregation mechanism, and the ability of httNT mutations (see Fig. 1C) and binding factors 49 to abrogate or modulate this effect, likely contribute to some observed cellular effects. In fact, our recognition that polyQ sequences may aggregate by entirely different mechanisms, depending on flanking sequences, suggests that at least some of the diversity of aggregate morphologies observed in exon1 cell and animal models 11,50 may ultimately be explained by the biophysical character of the exon1 sequence itself.

METHODS

Materials

All huntingtin-related peptides, as well the Pro14 and Ala-rich peptide “Bal” 31, were obtained in non-purified form from the small-scale custom peptide synthesis facility of the Keck Biotechnology Center at Yale University (http://keck.med.yale.edu/ssps/). Peptides were purified by reverse phase HPLC and structures confirmed by mass spectroscopy on an Agilent 1100 electrospray MSD 24. Purified peptides were routinely freshly disaggregated before use, as described 24. Porcine insulin and aprotinin were from Sigma-Aldrich. Acetonitrile, hexafluoroisopropanol (99.5% (v/v), spectrophotometric grade), and formic acid were from Acros Organics, trifluoroacetic acid (99.5% (v/v), Sequanal Grade) was from Pierce, and trifluoroethanol was from Sigma-Aldrich.

General methods

The sedimentation assay 24, the ThT and 90° light scattering assays 51, and the nucleation kinetics analysis 5,24, have been described. The isolation of aggregates for analysis was conducted by centrifuging a reaction aliquot at 20,817 × g in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 4 ° C for 30 mins, washing the pellet 2−3 times with PBS, resuspending in buffer, and determining the aggregate concentration by an HPLC analysis of a dissolved aliquot, as described 24.

Electron microscopy

Aliquots of whole aggregation reaction mixture were taken at different time points and visualized by electron microscopy. 3 μl of sample were placed on a freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated grid, adsorbed for 2 minutes, washed with deionized water before staining with 2μl of 1% uranyl acetate and blotting. Grids were imaged on a Tecnai T12 microscope (FEI Co., Hillsboro, Oregon) operating at 120kV and 30,000× magnification, and equipped with an UltraScan 1000 CCD camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, California) with post-column magnification of 1.4×.

Circular dichroism

CD spectra were collected using a Jasco J-810 spectrapolarimeter with a 1 mm pathlength quartz cuvette. HttNT samples were collected in 20 mM Tris-TFA pH 7.2 at concentrations of 20 − 500 μM. The spectra were collected immediately after thawing (from −80 °C) the disaggregated peptide samples. Scans were made at 20 nm per min with steps of 0.5 nm and an averaging time of 8s. The reported spectra are averages taken over 4 scans.

Proton NMR

The httNT sample for NMR experiments contained 40 μM peptide in 20mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 0.02 % sodium azide, 6% 2H2O. NMR experiments were carried out on a Bruker Avance 800 MHz NMR spectrometer, equipped with a 5 mm z-axis gradient cryoprobe. The water solvent peak was suppressed using the WATERGATE W5 pulse sequence 52. Two dimensional (2D) homonuclear NOESY and TOCSY 53 data were acquired at 5 °C, using a 1.5 s recycle delay and mixing times of 200 ms and 60 ms. Complete backbone and side-chain proton assignments of httNT were obtained. Hα secondary chemical shifts (Δδ Hα) were calculated by subtracting sequence-corrected random coil values 54.

Analytical size exclusion chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography experiments were conducted with a Superdex peptide HR10/30 (Pharmacia Biotech) column on a Bio-Rad (Biologic Duo flow) chromatograph using 1ml min−1 flow rate and detection at 215 nm at ambient temperature. Peptides were suspended in PBS (polyQ peptides and httNT after disaggregation) at 20−100 μM and 100 μL injected. The Kav values and the plot between Kav vs. logMW were calculated as described in the GE Healthcare handbook Gel Filtration: Principles and Methods available on the GE Healthcare web site.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

FRET peptides (Table 1) were purified and disaggregated. The peptide solution in TFA/water, pH 3.0 obtained after the ultracentrifugation step of the disaggregation procedure was immediately adjusted to 5 μM concentration in 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4 and its fluorescence determined. Peptide solutions were confirmed to be aggregate-free at the end of the FRET measurements by electron microscopy, HPLC, ThT, and 90° light scattering measurements. Fluorescence spectra were recorded at room temperature with excitation and emission slit widths at 5 nm. Raw data obtained were buffer subtracted and energy transfer efficiencies (E) were calculated from fluorescence intensities at 353.5 nm from the emission spectra of the F17W and doubly labeled FRET peptide. The D-A distance (r) for each peptide was determined from the E value and the Ro value (26 Å) for the nitrotyrosine / tryptophan FRET pair 33,55. The measurements were carried out in triplicate and the mean value (r) is reported with standard deviation.

Peptide concentrations underpinning the FRET determination were made in two different ways, which gave very similar results. In one method, we used amino acid composition analysis (Keck Biotechnology Center, Yale University) to calibrate a stock solution of the peptide which was then used as an HPLC standard for future determinations 24. In the second method, the UV absorption peaks at 280 nm of Trp and 381 nm of nitro tyrosine were used to normalize concentrations of F17W and doubly labeled FRET peptides using the extinction coefficients of Trp ε280 nm = 5,600 M−1 cm−1 and nitro tyrosine ε381 nm = 2,200 M−1 cm−1 , respectively 56.

Dot blots

Dot blots were performed as described 21. Aggregate samples were harvested, resuspended, and quantified as described in General Methods, and aliquots containing 400 ng of aggregates were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. In parallel, a portion of the unfractionated aggregation reaction mixture was transferred in to nitrocellulose membrane at various time intervals. Blots were incubated with Tris-buffered saline (TBST) containing 5% BSA overnight, washed three times with TBST, and incubated with a 10 nM solution of purified MW1 antibody 57 (a gift from Jan Ko and Paul Patterson) for 2 h. After washing with TBST to remove unbound material, blots were incubated 2 hrs with a 1:15,000 dilution of a peroxidase conjugate of anti-mouse IgG (whole molecule) (Sigma, A4416), then washed four times with TBST. Blots were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence solution (Pierce #A4416) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Tryptophan fluorescence emission of aggregates

Aggregates were isolated at different times as described in General Methods, then resuspended in 300 μL 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.4 and analyzed on a Perkin Elmer luminescence LS50B spectrometer. The samples were excited at 280 nm and emission was scanned between 290 and 550 nm. The wavelength at the emission intensity maximum was recorded.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of various samples was performed using MB series spectrophotometer with PROTA software (ABB Bomem). Protein aggregates were harvested by centrifugation at 20,817 × g and the pellet was washed 3 times with PBS. Spectra of re-suspended aggregates were recorded at 4 cm−1 resolution (400 scans at room temperature). Spectra were corrected for the residual buffer absorption by subtracting the buffer alone spectrum interactively until a flat baseline was obtained between 1,700−1,800 cm−1. Second-derivative spectra for the Amide I region were calculated from the primary spectrum by using PROTA software.

For the Q15 monomer sample, the peptide was purified by reverse phase HPLC with an aqueous acetonitrile gradient in 5 mM HCl to avoid exposure of the peptide to TFA, which gives a large peak in FTIR. Peak fractions were pooled and lyophilized, and the powder dissolved in 50 μl of 1 mM HCl , then centrifuged 1 hr at 435,680 × g. A 25 μl aliquot was carefully removed and mixed with 25 μL of a 2X PBS buffer, centrifuged for 30 mins at 435,680 × g, and the supernatant subjected to analysis. This material appears to contain about 20% by mass of amyloid-like polyQ aggregates, based on ThT analysis, presumably because of its very high concentration (2.4 mM) and the abbreviated and modified disaggregation protocol necessitated by the demands of the experiment.

Trypsin sensitivity of aggregates

For the monomer control, httNT was disaggregated and dissolved in pH 3 TFA in water, then added to a solution of trypsin (SEQUENZ-Trypsin, Worthington Biochemical Corporation) in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0 to yield a 1:10 ratio of trypsin to peptide in 50 mM Tris. This solution was incubated at room temperature and monitored by injection of aliquots onto a RP-HPLC-MS system (Agilent 1100), which indicated efficient cleavage after the httNT Lys residues (data not shown). Aggregates were harvested and quantified as described in General Methods, then incubated with trypsin at 1:10 w/w (trypsin: peptide) in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0 at room temperature. LC-MS of digest centrifugation supernatants yielded no material. All the material was found in pellet fractions and was undigested (data not shown).

Microplate elongation assay

The elongation of biotinylated Q29 (B-Q29) on httNTQ20P10 aggregates harvested at different times was done as described 6.

Data analysis

For all reaction profiles, datasets were fit in Sigma Plot to either 3-parameter equations (exponential decay, exponential rise to maximum, or sigmoidal) or linear regression. Reported R2 values and standard deviations (“S.D.”) are from the Sigma Plot fits. Many data sets were obtained in duplicate, and those that were not are representative of multiple experiments. The tight error bars for the HPLC sedimentation assay data obtained in duplicate (Fig. 1A, all datasets but for httNT and httNTQ36P10), along with the excellent curve fits throughout Figure 1, give us confidence in the datasets where only single replicates were taken (Figs. 1B and 1C). Duplicate data points in Figure 7 were derived from two experiments run at different times, and some points (0.6 hrs, 4 hrs: ThT, LS; 28 hrs, 69 hrs: HPLC, ThT, LS) are represented by only one replicate. The larger error bars for ThT and LS readings at the later time points are typical for late-stage amyloid formation reactions as fibrils grow larger. P-values were calculated using the two-tailed Student's t-test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Jan Ko and Paul Patterson (California Institute of Technology) for a gift of MW1 antibody, and Tim Fullam (Allegheny College) for providing a set of aggregation kinetics data. We also acknowledge the following funding sources that contributed to the work described here: NIH R01 AG019322 (RW); Huntington's Disease Society of America postdoctoral fellowship (VMC); NSF MCB-0444049 (TPC); Petroleum Research Fund / American Chemical Society 43138-AC4 (TPC).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bates GP, Benn C. The polyglutamine diseases. In: Bates GP, Harper PS, Jones L, editors. Huntington's Disease. Oxford University Press; Oxford, U.K.: 2002. pp. 429–472. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates GP, Harper PS, Jones L, editors. Huntington's Disease. Oxford University Press; Oxford, U.K.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wetzel R. Misfolding and aggregation in Huntington's disease and other expanded polyglutamine repeat diseases. In: Dobson CM, Kelly JW, Ramirez-Alvarado M, editors. Protein Misfolding Diseases: Current and Emerging Principles and Therapies. Wiley; New York: 2009. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–10. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Ferrone F, Wetzel R. Huntington's Disease age-of-onset linked to polyglutamine aggregation nucleation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11884–11889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182276099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya AM, Thakur AK, Wetzel R. polyglutamine aggregation nucleation: thermodynamics of a highly unfavorable protein folding reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15400–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wetzel R. Chemical and physical properties of polyglutamine repeat sequences. In: Wells RD, Ashizawa T, editors. Genetic instabilities and neurological diseases. Elsevier; San Diego: 2006. pp. 517–534. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slepko N, et al. Normal-repeat-length polyglutamine peptides accelerate aggregation nucleation and cytotoxicity of expanded polyglutamine proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14367–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherzinger E, et al. Huntingtin-encoded polyglutamine expansions form amyloid-like protein aggregates in vitro and in vivo. Cell. 1997;90:549–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poirier MA, et al. Huntingtin spheroids and protofibrils as precursors in polyglutamine fibrilization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41032–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wacker JL, Zareie MH, Fong H, Sarikaya M, Muchowski PJ. Hsp70 and Hsp40 attenuate formation of spherical and annular polyglutamine oligomers by partitioning monomer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1215–22. doi: 10.1038/nsmb860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caughey B, Lansbury PT. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:267–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham RK, et al. Cleavage at the caspase-6 site is required for neuronal dysfunction and degeneration due to mutant huntingtin. Cell. 2006;125:1179–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharyya A, et al. Oligoproline effects on polyglutamine conformation and aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masino L, et al. Characterization of the structure and the amyloidogenic properties of the Josephin domain of the polyglutamine-containing protein ataxin-3. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:1021–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Chiara C, Menon RP, Dal Piaz F, Calder L, Pastore A. Polyglutamine is not all: the functional role of the AXH domain in the ataxin-1 protein. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:883–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulone D, Masino L, Thomas DJ, San Biagio PL, Pastore A. The Interplay between PolyQ and Protein Context Delays Aggregation by Forming a Reservoir of Protofibrils. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellisdon AM, Thomas B, Bottomley SP. The two-stage pathway of ataxin-3 fibrillogenesis involves a polyglutamine-independent step. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16888–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ignatova Z, Gierasch LM. Extended polyglutamine tracts cause aggregation and structural perturbation of an adjacent beta barrel protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12959–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ignatova Z, Thakur AK, Wetzel R, Gierasch LM. In-cell aggregation of a polyglutamine-containing chimera is a multistep process initiated by the flanking sequence. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36736–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duennwald ML, Jagadish S, Muchowski PJ, Lindquist S. Flanking sequences profoundly alter polyglutamine toxicity in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11045–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604547103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rockabrand E, et al. The first 17 amino acids of Huntingtin modulate its sub-cellular localization, aggregation and effects on calcium homeostasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:61–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Nuallain B, et al. Kinetics and thermodynamics of amyloid assembly using a high-performance liquid chromatography-based sedimentation assay. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:34–74. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen S, Berthelier V, Yang W, Wetzel R. Polyglutamine aggregation behavior in vitro supports a recruitment mechanism of cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:173–182. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrone F. Analysis of protein aggregation kinetics. Meths. Enzymol. 1999;309:256–274. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modler AJ, et al. Polymerization of proteins into amyloid protofibrils shares common critical oligomeric states but differs in the mechanisms of their formation. Amyloid. 2004;11:215–31. doi: 10.1080/13506120400014831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bieschke J, et al. Small molecule oxidation products trigger disease-associated protein misfolding. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:611–9. doi: 10.1021/ar0500766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Serrano L. Protein aggregation and amyloidosis: confusion of the kinds? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wetzel R. Mutations and off-pathway aggregation. Trends in Biotechnology. 1994;12:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marqusee S, Robbins VH, Baldwin RL. Unusually stable helix formation in short alanine-based peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5286–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuler B, Lipman EA, Eaton WA. Probing the free-energy surface for protein folding with single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy. Nature. 2002;419:743–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu P, Brand L. Resonance energy transfer: methods and applications. Anal Biochem. 1994;218:1–13. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzkee NC, Rose GD. Reassessing random-coil statistics in unfolded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12497–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atwal RS, et al. Huntingtin has a membrane association signal that can modulate huntingtin aggregation, nuclear entry and toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2600–15. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitmore L, Wallace BA. DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W668–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohan A, et al. Analysis of molecular recognition features (MoRFs). J Mol Biol. 2006;362:1043–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LeVine H. Quantification of β-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Meth Enzymol. 1999;309:274–84. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Nuallain B, Williams AD, Westermark P, Wetzel R. Seeding specificity in amyloid growth induced by heterologous fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17490–17499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serio TR, et al. Nucleated conformational conversion and the replication of conformational information by a prion determinant. Science. 2000;289:1317–21. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kodali R, Wetzel R. Polymorphism in the intermediates and products of amyloid assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bevivino AE, Loll PJ. An expanded glutamine repeat destabilizes native ataxin-3 structure and mediates formation of parallel beta -fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11955–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211305198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bracken C, Iakoucheva LM, Romero PR, Dunker AK. Combining prediction, computation and experiment for the characterization of protein disorder. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:570–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammarstrom P, et al. Structural mapping of an aggregation nucleation site in a molten globule intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32897–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cattaneo E, et al. Loss of normal huntingtin function: new developments in Huntington's disease research. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:182–8. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01721-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaltenbach LS, et al. Huntingtin interacting proteins are genetic modifiers of neurodegeneration. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e82. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nozaki K, Onodera O, Takano H, Tsuji S. Amino acid sequences flanking polyglutamine stretches influence their potential for aggregate formation. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3357–64. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steffan JS, et al. SUMO modification of Huntingtin and Huntington's disease pathology. Science. 2004;304:100–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1092194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colby DW, et al. Potent inhibition of huntingtin aggregation and cytotoxicity by a disulfide bond-free single-domain intracellular antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408134101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wanderer J, Morton AJ. Differential morphology and composition of inclusions in the R6/2 mouse and PC12 cell models of Huntington's disease. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;127:473–84. doi: 10.1007/s00418-007-0272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen S, Berthelier V, Hamilton JB, O'Nuallain B, Wetzel R. Amyloid-like features of polyglutamine aggregates and their assembly kinetics. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7391–9. doi: 10.1021/bi011772q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu M, et al. Improved WATERGATE pulse sequences for solvent suppression in NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Resonance. 1998;132:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bax A, Davis DG. MLEV-17-based two-dimensional homonuclear magnetization transfer spectroscopy. J. Magn. Resonance. 1985;65:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwarzinger S, et al. Sequence-dependent correction of random coil NMR chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2970–8. doi: 10.1021/ja003760i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluoresence Spectroscopy. Vol. 954. Kluwer; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tcherkasskaya O, Ptitsyn OB. Direct energy transfer to study the 3D structure of non-native proteins: AGH complex in molten globule state of apomyoglobin. Protein Eng. 1999;12:485–90. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.6.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ko J, Ou S, Patterson PH. New anti-huntingtin monoclonal antibodies: implications for huntingtin conformation and its binding proteins. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56:319–29. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal Biochem. 2000;287:252–60. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jackson M, Mantsch HH. The use and misuse of FTIR spectroscopy in the determination of protein structure. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30:95–120. doi: 10.3109/10409239509085140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Venyaminov S, Kalnin NN. Quantitative IR spectrophotometry of peptide compounds in water (H2O) solutions. I. Spectral parameters of amino acid residue absorption bands. Biopolymers. 1990;30:1243–57. doi: 10.1002/bip.360301309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]