Abstract

SNAP-25 is plasma membrane protein which, together with syntaxin and the synaptic vesicle protein VAMP/synaptobrevin, forms the SNARE docking complex for regulated exocytosis. SNAP-25 also modulates different voltage-gated calcium channels, representing therefore a multifunctional protein that plays essential roles in neurotransmitter release at different steps. Recent genetic studies of human populations and of some mouse models implicate that alterations in SNAP-25 gene structure, expression and/or function may contribute directly to these distinct neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders.

Keywords: SNAP-25, schizophrenia, epilepsy, ADHD, calcium channels

SNAP-25: A MULTIFUNCTIONAL PROTEIN REGULATING SYNAPTIC TRANSMISSION

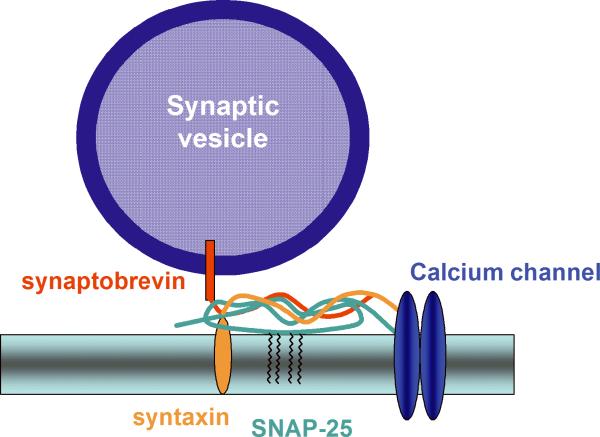

SNAP-25 (synaptosomal-associated protein of 25 kDa) is a SNARE protein that participates in the regulation of synaptic vesicle exocytosis. It is a membrane bound protein anchored to the membranes of neurons via palmitoyl side chains located in the central region of the molecule, and together with syntaxin and the synaptic vesicle protein VAMP/synaptobrevin constitutes the initial SNARE docking complex for regulated exocytosis. Clostridial toxins, which specifically cleave SNAP-25 have unequivocally demonstrated the requirement of the protein for vesicle exocytosis.1-3 Furthermore generation of SNAP-25 null mutant mice revealed that SNAP-25 is essential for evoked synaptic transmission, although it is not required for stimulus-independent neurotransmitter release.4 Besides its well characterized role in regulating exocytosis, there is increasing evidence that SNAP-25 also modulates various voltage gated ion channels.5,6 In particular, SNAP-25 interacts with different types of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs), including N type,7 P/Q type,8,9 and L type,10 through a channel region known as the synaptic protein interaction (synprint) site. In line with these data, SNAP-25 negatively controls neuronal calcium responsiveness to depolarization11 by specifically inhibiting, upon phosphorylation of Ser 187, neuronal VGCCs.12 SNAP-25 therefore represents a multifunctional synaptic protein that plays an essential role in synaptic vesicle fusion and modulates calcium dynamics in response to depolarization (fig. 1). Recently, evidence has accumulated that suggests that SNAP-25 is involved in different neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. The present review summarizes this recent literature which indicates that the altered expression of the protein may produce abnormal behavioral phenotypes, including schizophrenia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy.

Figure 1.

ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, MIM- Mendelian Inheritance in Man-143465) is one of the most prominent childhood neuropsychiatric disorders. It affects roughly 1 in 20 school-aged children in the U.S.,13 although a recent analysis reveals an even higher worldwide prevalence of 8-12%,14 with boys affected three or four times as frequently as girls.15 The major symptoms are persistent age-inappropriate behaviours of inattention and/or impulsivity and hyperactivity. As many as two thirds of children with ADHD have co-morbid disorders including language and communication deficits, disruption of learning and memory, anxiety and mood disorders and Tourette's syndrome.16 In about half of affected individuals, ADHD persists through adolescence into adulthood with deleterious effects on educational, social and occupational outcomes and a higher risk of developing substance abuse.14,17 One of the more striking aspects of ADHD is its clear inheritance, reflected by a 2-8 fold increased risk for either parents or siblings of ADHD-diagnosed individuals, and an estimate of 76% heritability based on twin studies.18 Several candidate genes have been implied and confirmed by linkage analysis. The multiplicity of these genes supports the idea that the biological heterogeneity may be a central factor to the clinical variability of the disorder. A number of studies have also implicated the role of environmental factors, which have been estimated to account for the additional variability in penetrance reported in twin studies.17-19 These environmental stressors have been shown to include maternal exposure to alcohol and smoking during pregnancy, head injury, obstetric complications and possibly lead exposure.15

The majority of genes evaluated for ADHD are involved in neurotransmission mediated by biogenic amines -dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin.18 The rational for focusing on these genes is drawn largely from the well-documented therapeutic benefit of psychostimulant medication (e.g., methylphenidate and amphetamine) in ameliorating the behavioral impairments associated with ADHD.20 Meta-analysis of linkage studies in case-controlled and family-based studies provide consistent evidence for the involvement of the dopamine D4 and D5 receptors, dopamine transporter, the synthetic enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase, the serotonin transporter and HTR1B receptor.18 Among these genes, only those encoding for D4 receptor21,22 and the dopamine transporter23 have been tested in mouse genetic models. These studies found significant neurochemical and behavioural effects only in homozygous null mutants.

SNAP-25 IN ADHD

Besides the biogenic amine candidate genes, the gene encoding SNAP-25 has been identified as responsible for hyperkinetic behaviour based on analysis of the coloboma mutant mouse. This mutant mouse is heterozygous for a neutron irradiation induced, semi-dominant deletion mutation spanning 4.6 Mb on mouse chromosome 2 that encompasses 10-12 genes, including Snap25.24 In coloboma mutant mice (Cm/+), deletion of the Snap25 gene results in 50% lower amounts of the SNAP-25 mRNA and protein expression compared to wild-type mice. Interestingly, coloboma mutant mice possess several phenotypic characteristics that parallel ADHD symptoms. Coloboma mice exhibit normal circadian rhythm and, as children with ADHD, they are hyperactive during their active (nocturnal) phase, with locomotor activity averaging three fold the activity of control littermates.25 Two key observations have led to the proposal that this mutant with reduced level of SNAP-25 expression represents a model for at least the hyperkinetic component of ADHD: 1) the hyperactivity was ameliorated by a low dose (4mg/kg, i.p.) of the psychostimulant amphetamine (AMPH), and 2) genetic rescue of the hyperactivity (but not the eye defect, or head bobbing) was obtained by crossing the mutant with SNAP-25 overexpressing transgenic mice.24 Interestingly, transgenic rescue of SNAP-25 function also restores normal dopaminergic transmission.26 Based on this first observation and supported by further behavioural and neurochemical analyses in the coloboma mutant mouse,27-32 polymorphisms at the SNAP25 gene locus in humans have been examined and association of SNAP-25 with ADHD has been determined in a number of linkage studies,33-39 a finding that has been further confirmed by meta-analysis.18

SCHIZOPHRENIA

Schizophrenia (MIM 181500) is a common mental disorder with a prevalence of approximately 0.5-1%13 and significant heritability estimated about 85%.40 The clinical symptoms can be classified into two main categories: psychotic or `positive' symptoms, including hallucinations, altered emotional activity, and disorganized behaviour, and `negative' symptoms, such as delusions, reduced interest and motivation and cognitive impairment. The disorder usually has its onset in early adulthood, although often cognitive and behavioural signs are present from childhood. Despite pharmacological treatments, outcomes are variable and approximately two-thirds of affected individuals have persistent symptoms with only partial remission.13 Schizophrenia is thought to be a neurodevelopmental disease characterized by defective connectivity in various brain regions during early life.41-43 The neuropathophysiology of schizophrenia remains unclear, although alterations in dopaminergic and serotoninergic circuitry (as in the case of ADHD), as well as in glutamatergic transmission have been strongly implicated. Numerous genetic linkage and association studies have identified regions of the genome that may harbor schizophrenia risk genes, but the complex genetics and symptomatology of the disease have limited progress in achieving a clear identification of the specific genetic determinants responsible for neurophysiological deficits that underpin the disorder.44 Candidate genes that have been shown to be potentially associated with the disease include neuregulin, a protein belonging to the EGF family; dysbindin, a protein constituent of the dystrophin-associated protein complex; Catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT), one of several enzymes that degrade catecholamines; the DISC1 (Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1) encoding a brain protein likely to play a role in cytoskeletal scaffolding; RGS4 (Regulator of G-protein Signaling 4) that modulates the GTPase activity of heteromeric G-proteins; GRM3, a metabotropic glutamate receptor; and the gene G72, which encodes a protein in brain thought to modulate NMDA glutamate receptor function.45 All these findings have led to the view of schizophrenia as a disorder of connectivity and synaptic signalling.44

SNAP-25 IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

A recent meta-analysis of 20 separate genome-wide linkage scans for schizophrenia-susceptibility genes reported significant linkage to the chromosomal region 20p12.3-11, which contains SNAP25, and suggested 20p12.3-11 as a strong candidate region for the disease.46 Evidence from several immunohistochemical and Western blot studies in postmortem brains implicated reductions in SNAP-25 expression in the etiology of schizophrenia. Decreased levels of SNAP-25 were found in the hippocampus47,48 and in the frontal lobe Broadman's area 10 of patients with schizophrenia in comparison with controls.49 In contrast, elevated levels of SNAP-25 were found in prefrontal lobe Broadman's area 949 and cingulate cortex.50 It has been suggested that these discrepancies in altered expression between different brain regions may not only reflect the depressed functionality of certain neural circuits, but also the hyperactivity of other pathways that may possibly result from compensatory mechanisms elicited through the neuropathophysiology of this disorder.48

The analysis of two genetic models has recently supported the involvement of SNAP-25 in the neuropsychopathology of schizophrenia. First, the mutant hDISC1 transgenic mouse, which has been proposed as an animal model of schizophrenia characterized by spontaneous locomotor activity, impaired spatial reference memory evaluated in the Morris water maze and abnormal social interaction, as shown by the decreased social non-aggressive activity, has been recently shown to lead to a significant reduction of SNAP-25 expression.51 Second, a chemical mutagen induced dominant mutation (I67T missense) in a highly conserved domain of Snap25 of the blind-drunk mutant mouse, appears to give rise to a schizophrenic phenotype that includes impaired sensorimotor gating, an important component of the schizophrenia phenotype related to altered sensory processing, anxiety and apathetic behaviors - phenotypic elements which appear to replicate aspects of the negative symptomatology of the disease.52

EPILEPSY

Epilepsy is a group of heterogeneous neurologic disorders affecting almost 1% of the population. It is characterized by recurrent, unprovoked episodes of seizures, due to abnormal synchronous firing of groups of neurons, arising from periodic neuronal hyperexcitability. Clinical manifestations of epilepsy are varied and despite availability of a number of antiepileptic drugs, about one-third of epileptic patients are resistant to treatment. Several changes can occur in the brain undergoing pathological hyperactivity, at the level of both single cells and anatomically defined neuronal networks. Based on electroencephalographic recordings, seizures can be classified in focal (originating in a single area of the brain) or generalized (involving both brain hemispheres). Generalized epileptic syndromes can be classified as symptomatic (caused by identifiable factors) or idiopathic (without a clear ethiology and partially caused by genetic defects).53 Generalized idiopathic epilepsies include childhood absence epilepsy and juvenile absence epilepsy. These are characterized by a short, sudden impairment in consciousness and behavioral arrest, possibly accompanied by facial clonus. The electroencephalographic hallmark of absence epilepsy are spike-wave discharges (SWDs) that occur in the thalamo-cortical circuitry. Mutations in different genes, including genes codifying for GABA receptors, Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels, have been associated to the familial forms of generalized idiopathic epilepsy with a Mendelian inheritance.54-56 Analysis of absence epilepsy mouse models tottering/tg, lethargic/lh and stargazer/stg, bearing mutations in α1A, β4, γ2 Ca2+ channel subunits respectively, revealed altered high voltage activated (HVA) channels current density in tg and stg thalamic neurons, and increased low voltage activated (LVA) channels peak current and a depolarized shift of the stady-state inactivation curves in tg, lh and stg thalamic neurons.57 Furthermore, the association of mutations in human α1A (P/Q type) channels with absence epilepsy has been reported.58

SNAP-25 IN EPILEPSY

Interestingly, the mutant mouse coloboma (Cm/+), which has been implicated as a model of ADHD (see above), has also provided evidence for the involvement of SNAP-25 in epilepsy. In addition to their hyperkinetic activity, Cm/+ mice display frequent spontaneous bursts of bilateral cortical SWDs that are accompanied by behavioral arrest, which is typical of absence epilepsy. These seizures could be completely blocked by intraperitoneal injection of the antiepileptic drug ethosuximide.59 Analysis of calcium current amplitude in thalamocortical neurons of this mutant, moreover, revealed an increase in the peak current density of LVA currents in Cm/+ cells compared to wild type mice. It is important that this calcium increase is not itself seizure-induced, as it precedes the developmental onset of SWDs,59 suggesting that the seizures may arise from abnormalities in calcium transients caused by a SNAP-25 deficiency in modulating presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels.12

CONCLUSIONS

SNAP-25 is a multifunctional synaptic protein that plays an essential role in neurotransmitter release via the formation of the SNARE complex4 and modulates calcium dynamics in response to depolarization.11,12 While recent genetic studies of human populations, and of some mouse models do implicate that alterations in SNAP-25 gene structure, expression and/or function may contribute directly to these distinct neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders, in other cases changes in SNAP-25 may represent a consequence of the neuropathologies of disease. Under this circumstance, effects on SNAP-25 expression could be downstream and secondary to maintaining synaptic homeostasis, resulting from altered neural circuits or network function, or from more general perturbations to brain development. Moreover, genetic studies have also revealed that candidate genes associated with neuropsychiatric disorders, including SNAP25, appear to contribute only a small effect towards the overall phenotype of disability (as reviewed in ref. 18 for ADHD). Consequently, these genetic components are likely to reflect susceptibility genes that act together and in concert with environmental factors to affect the broad spectrum of deficits associated with mental health disorders. Further studies are required, therefore, to delineate the potential mechanisms through which alterations in SNAP-25 may play a direct role in the etiology as well as contribute to the pathology of ADHD, schizophrenia, epilepsy and possibly other neuropsychiatric disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by EUSynapse Integrated Project, Telethon GP04196, Cariplo 2006.0779/10.9251, Compagnia di S.Paolo (Prog. 2005.1964) (M.M), and by National Institutes of Health Grant MH48989 (M.C.W.)

REFERENCES

- 1.Schiavo G, Matteoli M, Montecucco C. Neurotoxins affecting neuroexocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:717–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jahn R, Lang T, Südhof TC. Membrane fusion. Cell. 2003;112:519–533. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs-engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Washbourne P, Thompson PM, Carta M, et al. Genetic ablation of the t-SNARE SNAP-25 distinguishes mechanisms of neuroexocytosis. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:19–26. doi: 10.1038/nn783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catterall WA. Interactions of presynaptic Ca2+ channels and snare proteins in neurotransmitter release. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;868:144–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamponi GW. Regulation of presynaptic calcium channels by synaptic proteins. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;92:79–83. doi: 10.1254/jphs.92.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheng ZH, Rettig J, Cook T, et al. Calcium-dependent interaction of N-type calcium channels with the synaptic core complex. Nature. 1996;379:451–454. doi: 10.1038/379451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rettig J, Sheng ZH, Kim DK, et al. Isoform-specific interaction of the alpha1A subunits of brain Ca2+ channels with the presynaptic proteins syntaxin and SNAP-25. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;9:7363–7368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-Moutot N, Charvin N, Leveque C, et al. Interaction of SNARE complexes with P/Q-type calcium channels in rat cerebellar synaptosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;22:6567–6570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiser O, Trus M, Hernandez A, et al. The voltage sensitive Lc-type Ca2+ channel is functionally coupled to the exocytotic machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;5:248–253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verderio C, Pozzi D, Pravettoni E, et al. SNAP-25 modulation of calcium dynamics underlies differences in GABAergic and glutamatergic responsiveness to depolarization. Neuron. 2004;41:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pozzi D, Condliffe SB, Bozzi Y, et al. Activity-dependent phosphorylation of Ser187 is required for SNAP-25-negative modulation of neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:323–328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706211105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World Psychiatry. 2003;2:104–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366:237–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66915-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantwell DP. Attention deficit disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1996;35:978–987. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199608000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007;32:631–642. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, et al. Molecular genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thapar A, O'Donovan M, Owen MJ. The genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:R275–282. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castellanos FX. Toward a pathophysiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila) 1997;36:381–393. doi: 10.1177/000992289703600702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falzone TL, Gelman DM, Young JI, et al. Absence of dopamine D4 receptors results in enhanced reactivity to unconditioned, but not conditioned, fear. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;15:158–164. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avale ME, Falzone TL, Gelman DM, et al. The dopamine D4 receptor is essential for hyperactivity and impaired behavioral inhibition in a mouse model of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:718–726. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gainetdinov RR, Jones SR, Caron MG. Functional hyperdopaminergia in dopamine transporter knock-out mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess EJ, Collins KA, Wilson MC. Mouse model of hyperkinesis implicates SNAP-25 in behavioral regulation. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3104–3111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-03104.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess EJ, et al. Spontaneous locomotor hyperactivity in a mouse mutant with a deletion including the Snap gene on chromosome 2. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:2865–2874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02865.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steffensen SC, Henriksen SJ, Wilson MC. Transgenic rescue of SNAP-25 restores dopamine-modulated synaptic transmission in the coloboma mutant. Brain Res. 1999;847:186–195. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heyser CJ, Wilson MC, Gold LH. Coloboma hyperactive mutant exhibits delayed neurobehavioral developmental milestones. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1995;89:264–269. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raber J, Mehta PP, Kreifeldt M, et al. Coloboma hyperactive mutant mice exhibit regional and transmitter-specific deficits in neurotransmission. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:176–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68010176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones MD, Williams ME, Hess EJ. Abnormal presynaptic catecholamine regulation in a hyperactive SNAP-25-deficient mouse mutant. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2001;68:669–676. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones MD, Hess EJ. Norepinephrine regulates locomotor hyperactivity in the mouse mutant coloboma. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003;75:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruno KJ, Freet CS, Twining RC, et al. Abnormal latent inhibition and impulsivity in coloboma mice, a model of ADHD. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;25:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan X, Hess EJ. D2-like dopamine receptors mediate the response to amphetamine in a mouse model of ADHD. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;26:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barr CL, Feng Y, Wigg K, et al. Identification of DNA variants in the SNAP-25 gene and linkage study of these polymorphisms and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2000;5:405–409. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brophy K, Hawi Z, Kirley A, et al. Synaptosomal associated protein 25 (SNAP-25) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): evidence of linkage and association in the Irish population. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7:913–917. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mill J, Curran S, Kent L, et al. Association study of a SNAP-25 microsatellite and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002;114:269–271. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kustanovich V, Merriman B, McGough J, et al. Biased paternal transmission of SNAP-25 risk alleles in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:309–315. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mill J, Richards S, Knight J, et al. Haplotype analysis of SNAP-25 suggests a role in the aetiology of ADHD. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9:801–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng Y, Crosbie J, Wigg K, et al. The SNAP25 gene as a susceptibility gene contributing to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:998–1005. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi TK, Lee HS, Kim JW, et al. Support for the MnlI polymorphism of SNAP25; a Korean ADHD case-control study. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12:224–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cardno AG, Gottesman II. Twin studies of schizophrenia: from bow-and-arrow concordances to star war Mx and functional genomics. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;97:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rehn AE, Rees SM. Investigating the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2005;32:687–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lang UE, Puls I, Muller DJ, et al. Molecular mechanisms of schizophrenia. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2007;20:687–702. doi: 10.1159/000110430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh T, McClellan JM, McCarthy SE, et al. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:40–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirov G, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ. Finding schizophrenia genes. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1440–1448. doi: 10.1172/JCI24759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis CM, Levinson DF, Wise LH, et al. Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part II: Schizophrenia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:34–48. doi: 10.1086/376549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young CE, Arima K, Xie J, et al. SNAP-25 deficit and hippocampal connectivity in schizophrenia. Cereb. Cortex. 1998;8:261–268. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson PM, Egbufoama S, Vawter MP. SNAP-25 reduction in the hippocampus of patients with schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;27:411–417. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson PM, Sower AC, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Altered levels of the synaptosomal associated protein SNAP-25 in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;43:239–243. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabriel SM, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, et al. Increased concentrations of presynaptic proteins in the cingulate cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:559–566. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830180077010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pletnikov MV, Ayhan Y, Nikolskaia O, et al. Inducible expression of mutant human DISC1 in mice is associated with brain and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:173–186. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeans AF, Oliver PL, Johnson L, et al. A dominant mutation in Snap25 causes impaired vesicle trafficking, sensorimotor gating, and ataxia in the blind-drunk mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:2431–2436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610222104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher R, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) Epilepsia. 2005;46:470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mulley JC, Scheffer IE, Petrou S, et al. Channelopathies as a genetic cause of epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2003;16:171–176. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000063767.15877.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khosravani H, Zamponi GW. Voltage-gated calcium channels and idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:941–966. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Helbig I, Scheffer IE, Mulley JC, et al. Navigating the channels and beyond: unravelling the genetics of the epilepsies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:231–245. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Mori M, Burgess DL, et al. Mutations in high-voltage-activated calcium channel genes stimulate low-voltage-activated currents in mouse thalamic relay neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:6362–6371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06362.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jouvenceau A, Eunson LH, Spauschus A, et al. Human epilepsy associated with dysfunction of the brain P/Q-type calcium channel. Lancet. 2001;358:801–807. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05971-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Vilaythong AP, Yoshor D, et al. Elevated thalamic low-voltage-activated currents precede the onset of absence epilepsy in the SNAP25-deficient mouse mutant coloboma. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5239–5248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0992-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]