Abstract

Peripheral neuropathy is an important complication of antiretroviral therapy. Nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI)-associated mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation and nutritional factors are implicated in its pathogenesis. Pharmacogenetic and genomic studies investigating NRTI neurotoxicity have only recently become possible via the linkage of HIV clinical studies to large DNA repositories. Preliminary case–control studies using these resources suggest that host mitochondrial DNA haplogroup polymorphisms in the hemochromatosis gene and proinflammatory cytokine genes may influence the risk of peripheral neuropathy during antiretroviral therapy. These putative risk factors await confirmation in other HIV-infected populations but they have strong biological plausibility. Work to identify underlying mechanisms for these associations is ongoing. Large-scale studies incorporating clearly defined and validated methods of neuropathy assessment and the use of novel laboratory models of NRTI-associated neuropathy to clarify its pathophysiology are now needed. Such investigations may facilitate the development of more effective strategies to predict, prevent and ameliorate this debilitating treatment toxicity in diverse clinical settings.

Keywords: genetic polymorphism, haplogroup, hemochromatosis, HIV/AIDS, iron metabolism, mitochondrial, nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor, peripheral neuropathy, pharmacogenomics

Changing epidemiology of antiretroviral drug regimens & their complications

The introduction of highly active, combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), including nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and HIV-1 protease inhibitors, has led to dramatic improvements in the clinical outcomes of individuals with HIV infection in countries where these drugs are readily available [1]. However, commonly occurring ART-associated toxicities can significantly impact the quality of life in HIV-infected individuals [2-6]. Peripheral neuro pathy is a particularly painful and debilitating complication associated with NRTI therapy, particularly the dideoxy-NRTIs (dNRTIs) zalcitabine (ddC) and didanosine (ddI), as well as the thymidine-analog NRTI stavudine (d4T), and it may hinder adherence to otherwise life-saving treatment [6,7].

Initial treatment regimens for HIV infection currently include two NRTIs plus either an HIV-protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). Owing to the extremely high incidence of neuropathy and other toxicities associated with ddC, that drug was banned worldwide. The drugs, ddI and d4T, are also associated with a high incidence of peripheral neuropathy and are therefore only occasionally used among treatment-experienced patients in developed countries [201,8,9]. Although the incidence of other neurological complications of HIV infection has declined [10], peripheral neuropathy is increasingly prevalent, particularly in resource-poor areas of the world where the use of the more neurotoxic antiretroviral drugs, such as ddI and d4T, remains a practical necessity due to their low cost and availability in generic fixed-dose combinations [11-16].

Approaches to the identification of genetic susceptibility factors in ART toxicities

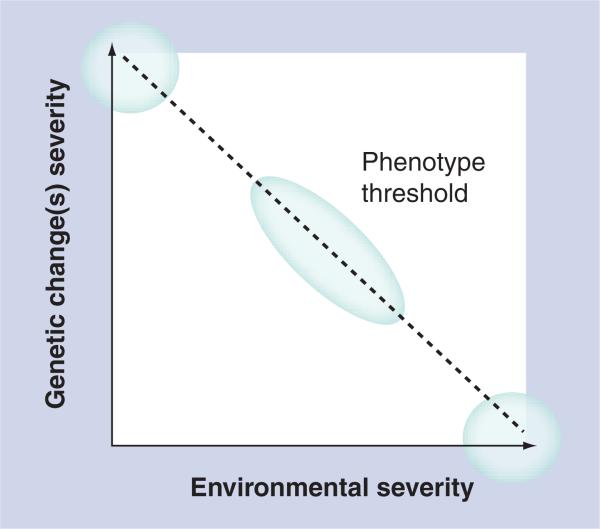

Owing to their well-documented potential for inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, NRTI therapy may be considered a significant environmental challenge, which when superimposed with genetic susceptibility, leads to a toxicity phenotype [17,18]. The environmentally determined genetic expression (EDGE) concept provides a framework for considering the combinations of exposures, genetic and environmental, that define the thresholds for expression of specific phenotypes in an individual (Figure 1) [19]. This concept holds that:

■ Genetic variation in expressed proteins have different effects in different environmental contexts;

■ Disease or toxicity phenotype is determined by both the functional magnitude of the genetic change and the severity of the environmental exposure;

■ Rare genetic diseases (e.g., inborn errors of metabolism or mitochondrial diseases) represent one extreme with little contribution from the environment, while large environmental insults result in phenotypes regardless of genetic variation;

■ Most phenotypes fall between these two extremes.

Figure 1. Concept of environmentally determined genetic expression.

Extreme genetic or extreme environmental changes can each lead to a phenotype when present alone, but most exposures lie between these two extremes: the effects of normally silent genetic variants (e.g., mitochondrial DNA or HFE polymorphisms) may be unmasked only in the presence of significant environmental insults (HIV infection and/or treatment with mitochondrial-toxic drugs).

Reproduced with permission from [19].

Exposure to mitochondrial-toxic NRTIs or other antiretroviral drug regimens may, therefore, unmask the effects of normally subtle or silent genetic variants.

Large-scale pharmacogenetic and genomic studies in the area of HIV therapeutics have only recently been made feasible by DNA banks linked to prospective HIV clinical trials [20] and cohort studies [21]. Pharmacogenetic studies of antiretroviral-drug hypersensitivity, ART resistance, long-term ART response, ART-induced liver abnormalities and lipoatrophy have been reviewed elsewhere [22-24]. The following review will focus specifically on the smaller number of published studies that have attempted to identify host pharmacogenetic risk factors for NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy, their contribution to understanding potential mechanisms underlying this complication and future directions of studies in this area.

NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy: risk factors, diagnosis & management

Peripheral neuropathy associated with NRTIs is typically a symmetric, distal sensory polyneuropathy characterized by painful dysesthesia and/or sensory loss, but it may also present with atypical manifestations [25-27]. Importantly, NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy is clinically and histologically similar to the peripheral neuropathy associated with HIV infection prior to the era of highly active ART and that may still complicate HIV infection in some individuals, except that it may start more abruptly and be more painful [28-30]. In many cases, the only distinguishing feature of NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy is the temporal association between the onset or worsening of neuropathic symptoms and the initiation of treatment that includes known offending NRTIs [26]. A length-dependent, Wallerian-type degeneration (‘dying back’) of predominantly small peripheral sensory nerve axons and apoptotic loss of dorsal root ganglia are characteristic of this complication [29,31,32]. Routine use of invasive testing such as nerve conduction velocity/electromyography (NCV/EMG) for objective diagnosis and confirmation by a neurologist are not feasible in many practice settings, nor are the results of these tests necessarily predictive of clinical signs and symptoms [33-36]. Unfortunately, clinical diagnoses made by non-neurologists have frequently been based on variable clinical criteria, as no gold standard exists [37]. Accurate estimates of the incidence of symptomatic peripheral neuropathy associated with NRTI use are therefore limited, but they have ranged from 10 to 25% after 1 year of ART and to over 50% after 2 years of exposure to the more neurotoxic dNRTI drugs [10,38-40]. Typical clinicopathologic features and diagnostic findings in NRTI- and HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of peripheral neuropathy in HIV infection.

| Feature | HIV associated and/or pre-HAART era | NRTI associated (post-HAART era) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic criteria/symptoms |

Aching or burning, pain, pins and needles, and/or numbness plus absent ankle reflex, reduced vibratory sensation in the great toe or both |

Same but temporally related to initiation of dNRTIs (usually within 6 months) |

| Onset and course |

More gradual and less painful, often irreversible |

Usually abrupt, may be more painful, may decrease or partially reverse with removal of offending drugs |

| Axons involved |

Small (sensory) fibers predominate |

Same |

| Pathology | Wallerian-type, length-dependent degeneration, with apoptosis of DRG and infiltration by activated macrophages | Same (?)* |

Treatment for NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy is largely symptomatic and often ineffective, although a large number of clinical interventions have been studied [41-50]. Stopping offending antiretroviral agents, switching therapy to a low-risk NRTI and dose reduction of agents such as d4T can slow progression but these interventions frequently do not reverse symptoms [15,41,42,51]. Accurate risk stratification of patients with HIV infection and avoidance of the antiretroviral drugs most likely to induce adverse effects, particularly in high-risk groups, is therefore an appealing strategy for improving adherence and minimizing the complications of long-term therapy. Clarifying the risk factors for NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy has been particularly challenging, however. Most of the adequately powered studies assessing risk factors have been limited by retrospective data collection and/or nonstandardized methods of ascertaining neuropathy [52]. In addition to exposure to specific NRTIs (e.g., ddI and d4T), host factors most consistently associated with an increased risk of NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy have included older age, lower CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and higher plasma HIV RNA levels at the time of initiation of ART (representing more advanced HIV disease) [31,53]. Other suggested risk factors for NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy for which supporting data are limited or less consistent are white race, diabetes mellitus, female sex, height, decreased creatinine clearance and concomitant use of hydroxyurea, interferon-α or the protease inhibitor indinavir (Table 2) [10,28-30,53-56]. Hydroxyurea may alter the metabolism of NRTIs when used in combination, and IFN-α may aggravate inflammatory nerve damage. Although protease inhibitors are not generally considered neurotoxic drugs, they may have direct neurotoxic effects or may act synergistically with dNRTIs [10,57,58].

Table 2.

Clinical risk factors associated with peripheral neuropathy during nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy.

| Factor | Level of evidence |

|---|---|

| dNRTI use (ddC>d4T>ddI; ddI plus d4T>d4T) |

1 |

| Older age |

1 |

| Increased HIV RNA load |

1 |

| Concomitant protease inhibitor (indinavir) |

2 |

| Overall poor nutrition |

2−3 |

| Underlying neuropathy of any cause |

2 |

| White race |

2 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

2 |

| Female sex |

1−2 |

| Height |

1−2 |

| Creatinine clearance |

2 |

| Hydroxyurea (with ddI/d4T) |

2 |

| IFN-α (with ddC/AZT) | 2 |

Level 1: at least one randomized clinical trial; Level 2: Nonrandomized controlled studies, cohort or case–control studies, time series with or without intervention, or strong effects in uncontrolled studies; Level 3: Opinion of expert committees, respected individuals, empiric observations, or data from purely descriptive studies [10,28-30,53-58,134].

AZT: Zidovudine; d4T: Stavudine; ddC: Zalcitabine; ddI: Didanosine; dNRTI: Dideoxynucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

Candidate pathways & processes for genetic modulation of NRTI neurotoxicity

Substantial variability in the onset, symptoms and severity of peripheral neuropathy among similarly treated HIV-infected individuals argues in favor of a role for host genomic variation in this complication of NRTI therapy. Recent data from prospective studies of peripheral neuropathy in parts of the world where neurotoxic NRTIs are still widely used also suggest that individual susceptibility may be a more important determinant of peripheral neuropathy during treatment than cumulative drug exposure [39].

Owing in part to difficulties in measuring NRTI metabolite concentrations (NRTI exposure) and challenges in the consistent diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy outcomes, relatively few pharmacogenetic studies of NRTI toxicities have been published to date [18,24,52,59]. One notable exception is the linkage of abacavir hypersensitivity, a condition easily confirmed by immunologic studies and skin testing, to HLA-B*5701. Large-scale prospective studies have confirmed the benefit of genomic screening for HLA-B*5701 among patients with HIV/AIDS who are considered for abacavir treatment [60-62]. This screening test is now recommended for routine clinical use and represents a success story for pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine [201,9,63]. Few such studies have identified genetic risk factors for NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy. Cellular pathways or processes in which genetic variation may impact the development of this complication are discussed below.

Drug metabolism: cellular pharmacology of NRTIs

Orally bioavailable, prodrug NRTIs undergo triphosphorylation to active compounds by intracellular kinases [59]. Exceptions include ddI and abacavir, which also require deamination, and the nucleotide analog tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, which is active as a diphosphate [53,59]. Active tri- (or di-) phosphorylated NRTIs competitively inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase, causing termination of viral DNA chain elongation due to the absence of the 3′-hydroxyl group required for phosphodiester bond formation [64]. Intracellular NRTI triphosphate concentrations are challenging to measure as noted above, but are likely to be an important factor in both the antiretroviral efficacy and the toxicity of these agents. Host differences with respect to intracellular phosphorylation and drug–drug or drug–nutrient interactions may be expected to alter NRTI dose and concentration, and in turn, susceptibility to toxicities. Examples of such factors that influence the risk of clinical NRTI-associated neuropathy include concomitant use of hydroxyurea (a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor that may increase generation of NRTI triphosphates by a number of mechanisms) [65,66], and increased phosphorylation of NRTIs in vitro with ribavirin (a component of antihepatitis C viral regimens) [67,68]. Higher intracellular NRTI triphosphate concentrations have been reported in women in several studies, consistent with epidemiological studies showing significantly higher rates of mitochondrial NRTI toxicities such as lipoatrophy, lactic acidosis and pancreatitis in women than in men [53,56]. Intramitochondrial concentrations of active NRTI moieties, which may be more relevant to mitochondrial toxicity, may also be modulated by variation in intramitochondrial kinases capable of phosphorylating NRTIs, and in deoxynucleotide carrier proteins [69,70] that shuttle NRTI phosphates into the mitochondria [53]. However, there remains controversy regarding the primary mitochondrial NRTI transport protein [71], and relatively little is known in regards to polymorphic variation of these genes in humans [72,73].

Disruption of mitochondrial function & oxidative stress

While relatively specific for viral reverse transcriptase, NRTIs also have varying affinities for human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) polymerase-γ (POLG), the primary enzyme responsible for mtDNA replication [74]. The mtDNA POLG hypothesis holds that inhibition of mtDNA POLG by NRTIs disrupts normal mitochondrial replication [75,76], leading to a cascade of events that culminates in impaired oxidative phosphorylation due to mitochondrial dysfunction, increased production of free radicals and oxidative stress, and ultimately tissue injury and symptomatic toxicity [70,75]. Details of this cascade have not been fully characterized, but the recent report of a novel, functional mtDNA POLG mutation being associated with NRTI-associated lactic acidosis [77] lends weight to the POLG inhibition hypothesis [78].

Several lines of evidence implicate mitochondrial injury in NRTI toxicities, including peripheral neuropathy [53,59,79,80]. Studies in cell lines [59,81], animal models [82-84] and in humans [85-87] have shown morphologic, quantitative and functional changes of mitochondria following NRTI exposure. In vivo studies have also demonstrated effects on mitochondrial function and mtDNA content in specific tissues that are targets for NRTI-associated toxicity [88-92]. Moreover, specific NRTIs are more neurotoxic than others, with ddC being considerably more toxic than ddI or d4T and the ddI/d4T combination being more toxic than d4T alone [53,93]. The differential neurotoxicity of NRTIs may relate to their different affinities for specific thymidine kinase isoforms or azidothymine (AZT), for example, has little toxicity to axons and Schwann cells, affecting primarily skeletal muscle mitochondria [28].

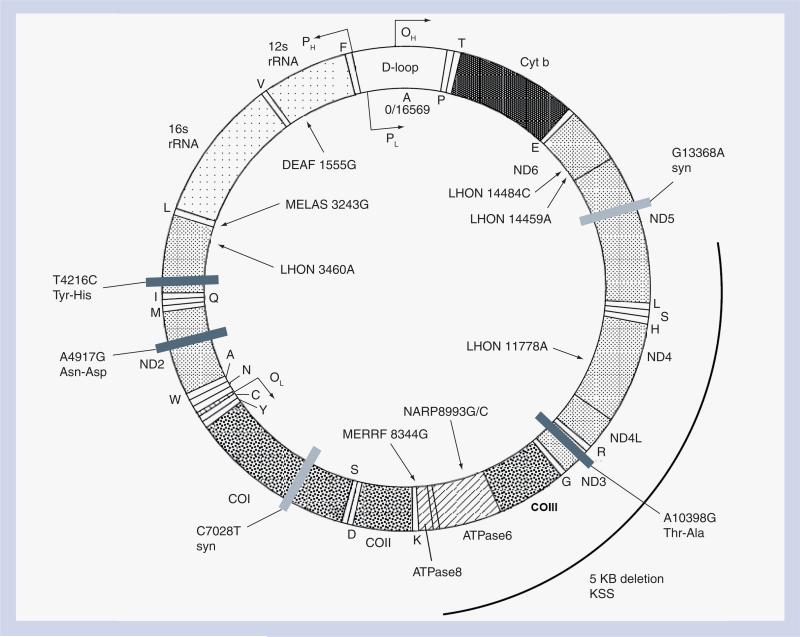

The 16,569 bp human mitochondrial genome, inherited exclusively through the maternal line, encodes ribosomal RNA, transfer RNA and 13 polypeptides that are required for oxidative phosphorylation [94,95]. mtDNA from different individuals can be classified according to specific haplogroups, or distinct patterns of heritable polymorphisms that have arisen during prehistoric human migrations [96]. The relevance of potential functional differences between mitochondrial haplogroups to complex disease pheno types has only recently gained recognition through studies of longevity and neurodegenerative diseases [97]. Although the germline mtDNA variants that define mitochondrial haplogroups are homoplasmic (uniformly distributed among mitochondria and among different tissues) and their effects are likely to be subtle, they may modify the impact of drugs, toxic environmental exposures, or other genetic factors. Owing to the high metabolic requirements of neurons, such mitochondrial variants may significantly alter the degree of peripheral nerve toxicity due to NRTIs [98]. Axoplasmic transport of mitochondria, an energy-requiring process, is also implicated in NRTI peripheral nerve toxicity; neurons with the longest axons and the smallest caliber may be most vulnerable to challenges to mitochondrial transport, consistent with the Wallerian-type degeneration observed with NRTI therapy. This may explain the sensitivity of the optic nerve to genetic, nutritional and toxic causes of mitochondrial dysfunction [99]. Indeed, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), a rare cause of inherited blindness due to inherited mitochondrial mutations, has been precipitated in some HIV-infected individuals upon starting NRTI therapy [100-102]. A schematic representation of the mitochondrial genome is shown in Figure 2. Inherited mutations in mtDNA have been associated with a variety of mitochondrial syndromes that include metabolic and/or neurological manifestations.

Figure 2. The human mitochondrial DNA genome showing the location of known mitochondrial disease-causing variants and variants associated with increased or decreased risk of peripheral neuropathy on nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy.

Synonymous polymorphisms are designated by light gray bars and nonsynonymous polymorphisms are represented by dark gray bars with amino acid changes indicated.

cyt b: Cytochrome b; DEAF: Mitochondrial deafness; LHON: Leber hereditary optic neuropathy; KSS: Kearns–Sayre Syndrome; MELAS: Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke; MERRF: Myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers; NARP: Neuropathy, ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa.

Illustration copied and adapted from [202] under licensing terms outlined at [203].

Oxidative stress, defined by the increased production of free radicals and other reactive oxygen/nitrogen species that damage cellular constituents, is clearly related to mitochondrial function and efficiency. Whether NRTI therapy, owing to its mitochondrial toxicity, induces oxidative stress in vivo, requires further study [103].

Inflammatory responses

Despite well-documented mitochondrial DNA POLG inhibition by NRTIs, studies have not consistently demonstrated a correlation between NRTI toxicity and changes in cellular mtDNA content, suggesting that other host factors also influence susceptibility. The difficulty of replicating NRTI-induced peripheral neuropathy in animal models and the association of advanced HIV disease status (e.g., low CD4 cell count) with this toxicity also raises the possibility that pre-existing HIV infection is a prerequisite for this toxicity [31,104,105]. Underlying asymptomatic nerve inflammation may also set the stage for neurotoxicity that becomes symptomatic or progresses once NRTI therapy is started [106]. Variations in the inflammatory response and nerve injury repair mechanisms may influence the neurotoxicity of NRTIs. An important histological feature of HIV-associated sensory neuropathies is varying degrees of infiltration of peripheral nerve axons and dorsal root ganglia by activated macrophages, and it has been suggested that neuronal drop-out may occur in response to the release of HIV-induced neurotoxic proteins like gp120 [29-31,106-109]. Proinflammatory cytokines and other mediators released during local inflammation may also be associated with dying-back of nerve fibers [29-30,106]. Cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage, which play a role in nerve injury and repair, may also be involved in other diseases in which Wallerian or Wallerian-type neuronal drop-out occurs, although the connection between inflammation, apoptosis and neuronal death in these conditions is unclear [50,99,104,110]. In addition, several of the clinical risk factors for NRTI-related neuro toxicity previously mentioned (e.g., increased age, low CD4 cell count and female sex) have been associated with increased concentrations of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and/or independently with increased intracellular NRTI phosphate concentrations, favoring a role for inflammation and variability in drug metabolism and transport [30,53,57]. In addition, animal studies suggest that NRTIs may upregulate chemokine receptors in dorsal root ganglia neurons, contributing to the unmasking of painful neuropathy in HIV infection [111].

Iron & other nutritional factors

Pre-existing neuropathy of any cause, and general poor nutritional status have also been reported to increase the risk of NRTI-induced peripheral neuropathy, although these factors are not well characterized [31,112]. Severe deficiencies of thiamine, riboflavin, nicotinic acid and iron have been associated with peripheral neuropathy and with small-fiber neuropathy in particular; B12 deficiency causes a predominantly large-fiber neuropathy. Several of these nutrients, integral components of mitochondrial flavoproteins and cytochromes, are required for normal mitochondrial function and nerve function; underlying deficiencies may predispose to mitochondrial NRTI toxicity and peripheral neuropathy. Host genetic variation in nutrient metabolism and transport may therefore impact these toxicities, particularly in view of the fact that metabolism of vitamin B12 and iron are abnormal in chronic HIV infection, and the prevalence of clinical deficiencies may be higher in HIV-infected individuals [28,32,113].

Lessons from studies of other types of drug-induced neuropathy

Studies aimed at understanding the pathogenesis of peripheral neuropathy associated with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and cancer chemotherapeutic drugs such as platinum-based agents have suggested roles for the following processes and/or pathways in NRTI neurotoxicity: axoplasmic transport of mitochondria, apoptosis, drug efflux and synthesis of antioxidant proteins [28,32]. The neuropathies caused by these drugs are also predominantly sensory but may have some motor nerve involvement. Specific nuclear and mitochondrial genes involved in apoptosis, axonal regeneration or repair, and antioxidant defense, have been implicated in these toxin-induced neuropathies; these genes have not been studied in relation to neuropathy occurring during NRTI therapy [114-118].

Pharmacogenetic studies of NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy

Variation in the nuclear-encoded DNA POLG gene, which is the major component of the mtDNA replication enzyme complex, has been suggested to modulate the risk of NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy. In a recent report, specific sequence variants of the POLG gene were characterized in 14 treated patients with peripheral neuropathy or lactic acidosis and compared with sequences from 45 patients without these NRTI toxicities. No significant correlations were found between the number of CAG repeats and either toxicity, although the study was underpowered, and no coding-region mutations were found in the three patients with lactic acidosis [119].

Multicenter studies conducted by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) have provided an extremely valuable resource for pharmacogenomic investigations of NRTI-related toxicities. The ACTG study 384 was a randomized, multicenter trial designed to evaluate initial HIV treatment strategies in adults. Patients were randomized to receive three- or four-drug therapy with either AZT plus lamivudine (3TC) or ddI plus d4T in combination with either efavirenz, nelfinavir or both. Details of the study protocol and neuropathy case ascertainment have been presented elsewhere [120,121]. Patients were followed for up to three years from this study, and peripheral neuropathy was assessed by systematic review of signs and symptoms at each study visit, using a consistent clinical definition. Objective tests such as NCV/EMG were not routinely performed in ACTG 384.

An important finding of the ACTG 384 study was that patients randomized to the didanosine/stavudine arm were much more likely to develop symptomatic peripheral neuropathy than those who received AZT/3TC. Since mitochondrial toxicity induced by NRTIs is at least partially responsible for this complication, our group examined mitochondrial DNA variants as potential predictors of neuropathy. Participants who also contributed DNA under ACTG protocol A5128 were included in all case–control genetic analyses; individuals who did and did not contribute DNA were similar with regard to the distribution of known risk factors for this toxicity [122]. Among 509 parent study participants with available DNA, 147 participants developed peripheral neuro pathy, 73% of whom had been randomized to receive ddI plus d4T. Among 137 self-identified non-Hispanic whites randomized to receive ddI/d4T, mitochondrial haplogroup T, a common European mitochondrial haplogroup, independently predicted neuropathy during study treatment (odds ratio [OR]: 5.4; 95% CI: 1.4−25.1; p < 0.01, adjusted for other risk factors). Further exploration of the effect of nonsynonymous mtDNA polymorphisms that underlie haplogroup-T revealed that the variant 4917G (adjusted OR: 5.5; 95% CI: 1.6−18.7; p < 0.01) was significantly associated with peripheral neuropathy in whites [122,123]. Interestingly, this mutation has been associated with other neurodegenerative phenotypes, including LHON and diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy and deafness (DIDMOAD), a rare syndrome of diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy and deafness [124-126]. Hearing loss has also been reported in association with NRTIs and may be related to mitochondrial toxicity, although whether ototoxicity really occurs with these drugs remains controversial [127,128]. The locations of the mitochondrial genomic variants studied to date are shown in Figure 2. The effects of these polymorphisms on mitochondrial function remain to be fully characterized.

In another study using data from ACTG study 384, our group showed an association between two common polymorphisms in the hemochromatosis (HFE) gene, 845G>A and 187C>G, with a reduced risk of neuropathy in participants who received ddI plus d4T at some point during the study [104]. In multivariate analysis, 845G>A heterozygotes in this sample were relatively protected from peripheral neuropathy (OR: 0.17; 95% CI: 0.03−0.83; p < 0.05). The HFE 187C>G polymorphism also conferred a reduced risk of neuropathy in univariate analysis but lost statistical significance after adjustment for other risk factors (OR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.23−21.1; p = 0.08). Hemochromatosis is a genetic iron overload disorder caused in the majority of cases by the 845G>A variant, which dysregulates iron absorption in the duodenum and increases the release of iron from macrophages to metabolically active cells [104,129,130]. Iron is essential for mitochondrial function, and either increased or decreased mitochondrial iron supply generates oxidative stress via mitochondrial dysfunction [131]. If the observed association between HFE 845G>A genotype and peripheral neuropathy in this cohort is valid, potential mechanisms for the association include an increased supply of iron to neuronal mitochondria or reduced inflammatory nerve injury that may in turn ameliorate NRTI-related mitochondrial toxicities [104,132,133]. However, HFE is linked to the HLA-A3 allele of the MHC-I locus, and linkage disequilibrium with other HLA-A3-bearing haplotypes may be responsible for these observed associations. Studies are currently underway to replicate these associations and to determine the relative importance of inflammation and iron stores in the development of NRTI-associated neuropathy.

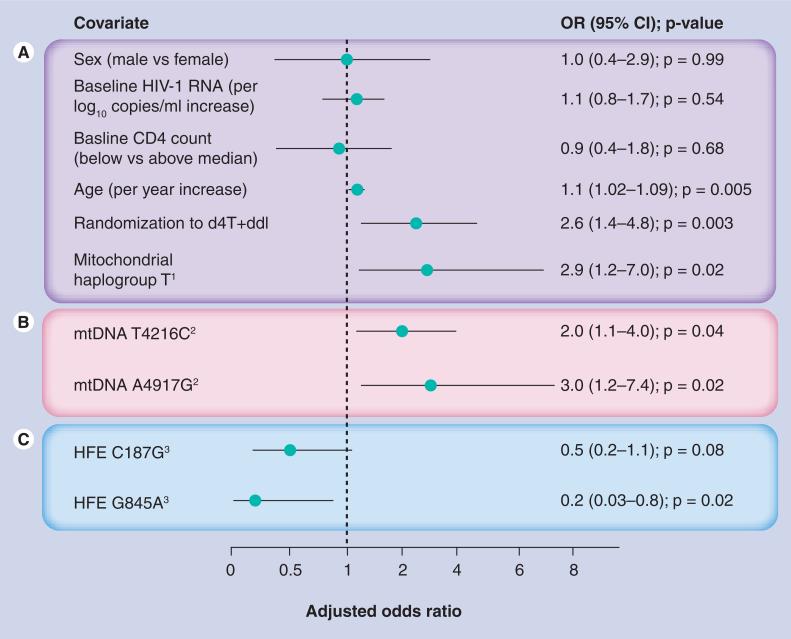

A summary of the observed multivariable ORs from pharmacogenomic studies of peripheral neuropathy in the ACTG study 384 is shown in Figure 3. It is important to note, however, that due to the slightly different statistical approaches used (predictive model vs hypothesis test), the sample size and models were not identical in these studies [104,122,123]. Age, baseline CD4 count, baseline HIV RNA concentration, randomization to (ddI plus d4T) treatment and concomitant antiretroviral drugs (blinded efavirenz, nelfinavir or both) were included as covariates. Mitochondrial analyses were also adjusted for sex.

Figure 3. Estimated effects of mitochondrial DNA and HFE gene variants in different pharmacogenomic studies of peripheral neuropathy based on the ACTG study 384 data, shown as multivariate-adjusted odds ratios.

The estimated effects were observed in separate analyses using slightly different statistical approaches, designated by shaded blocks [104,122,123]. (A) ORs adjusted for other listed potential confounders shown and in the case of nongenetic factors, for mitochondrial haplogroup T. This model was also adjusted for randomization to blinded non-NRTI study arms containing nelfinavir and/or efavirenz; these factors were not statistically associated with peripheral neuropathy (data not shown). (B) ORs from separate models adjusted for age, sex, baseline CD4 count and HIV RNA concentration, randomization to (ddI plus d4T) treatment and concomitant antiretroviral drugs. (C) ORs from separate models adjusted for age, baseline CD4 count and HIV RNA concentration, randomization to (ddI plus d4T) treatment, and concomitant antiretroviral drugs. d4T: Stavudine; ddI: Didanosine; HFE: Hemochromatosis; mtDNA: Mitochondrial DNA; NRTI: Nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors; OR: Odds ratio.

Finally, an association was also reported recently between the TNF-α 1031*2 polymorphism and sensory neuropathy that developed within 6 months of starting dNRTI-based therapy among a predominantly white Australian population with HIV infection [30]. In that study, neuropathy was also assessed using physical examination criteria and self-report of neuropathic symptoms. The association of alleles upstream of TNF-α and TNF-α 1031 with HIV RNA load and other mitochondrial toxicities lends biologic plausibility to these findings. TNF-α 308*2 and the closely linked BAT1(intron 10)*2 polymorphism, markers of the 8,1 haplotype (HLA-A1, B8, DR3) also predicted this complication in multivariate analysis [30]. In this study, the IL12B (3′-UTR)*2 genotype was more common in patients resistant to peripheral neuropathy, and a model including height and cytokine genotypes was able to predict this complication in the same population (p < 0.0001; R2 = 0.54). Individuals resistant to NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy and those who developed neuropathy more than 6 months after starting NRTIs were not significantly different. A more recent study in the Indonesian population by Affandi et al. recently replicated the TNF-α 1031*2 variant as a risk factor for NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy and found that a model including patient age, height and TNF-α genotype could predict the risk of symptomatic peripheral neuropathy prior to initiating therapy with d4T [134].

The genetic associations reported in the studies mentioned above require replication in independent cohorts of HIV-infected persons. One group has attempted to replicate the HFE associations with peripheral neuropathy in a case–control study conducted in 57 HIV-positive individuals in Italy who were matched on age, sex, history of heavy alcohol use, hepatitis B and C infection, and diabetes mellitus [135]. No significant differences in the distribution of HFE 845G>A and 187C>G polymorphisms were seen among neuropathy cases, confirmed by electromyography, and neuropathy-free controls from the same clinic. Only intravenous drug-use and a high HIV RNA levels were associated with peripheral neuropathy in multivariate analysis. This study was underpowered; a replication study should be at least as large as and ideally two- to three-times larger than the original study, since point estimates for the effect of specific genetic factors found in smaller studies are generally greater than the true effect in the population [136,137]. Secondly, although 35 (61%) and 28 (49%) cases were exposed to d4T and ddI, respectively, these NRTIs known for their neurotoxic effects showed no association with neuropathy risk in this study. The previously reported association of HFE poly morphisms with neuropathy in the ACTG study 384 was statistically significant only among patients exposed to ddI plus d4T. Interestingly, a nonsignificant but reduced risk of neuropathy was observed in the Italian study even with exposure to the highly neurotoxic drug ddC, documented in 14% of cases and 19% of controls. A high prevalence of intravenous drug-use, alcohol abuse and diabetes mellitus, as well as the exclusion of an undisclosed number of individuals with other risk factors for peripheral neuropathy may also have contributed to misclassification of true NRTI-associated neuropathy and selection bias in that study. These observations suggest that important differences existed between this HIV-infected population and the ACTG 384 study population in which associations with HFE polymorphisms were identified.

Some pathways and genes that may play a role in NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Candidate pathways and genes in which variation may influence susceptibility to peripheral neuropathy.

| Process | Examples of specific pathways and genes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidative | Antioxidant defense genes (e.g., GSH and GST) | [103,104,131] |

| Mitochondrial DNA synthesis and oxidative phosphorylation |

[18,23,46,50,63-68,76,84,93,97,107,108,111-114] |

|

| Inflammation and immune modulation |

Proinflammatory cytokine/adipokine genes (e.g., MHC-I-linked genes such as TNF-α), NF-κB activation pathways, macrophage chemotactic and inhibitory peptides |

[41,42,48,96,97,120,121,128] |

| Apoptosis |

EPO, EPO-R, BCL-2/BCL-XL and WLDs |

[42,86-88,104,105,131] |

| Nutrient metabolism and mitochondrial energy production |

Nuclear and mitochondrial metal ion transport (e.g., HFE, acetyl l-carnitine) |

[28,29,39,42,46,96] |

| Nerve injury/repair |

Ion channels, axoplasmic transport mechanisms, apoptosis and NGF |

[29,38,42,86,96] |

| Drug metabolism, activation and transport | Cytochrome P450 isoforms (e.g., CYP3A, CYP2B6), MDR1; intracellular NRTI phosphorylation | [17,18,45,57,58] |

References listed are those that favor involvement of the proposed pathways or genes.

BCL-2/BCL-XL: B-cell lymphoma pro- and anti-apoptotic gene family; CYP: Cytochrome P450; EPO: Erythropoietin; EPO-R: Erythropoietin receptor; GSH: Glutathione; GST: Glutathione-S-transferase; HFE: Hemochromatosis; MDR: Multidrug-resistance gene/P-glycoprotein; NGF: Nerve growth factor; NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; WLDs: Slow Wallerian degeneration protein.

Future perspective: implications for management of NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy

Genetic modifiers of complex phenotypes, particularly those associated with sporadic exposures such as NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy, may be identified using case–control association studies of candidate genes or pathways or increasingly, through microarray-based, genome-wide association study approaches. Candidate gene approaches make use of existing hypotheses or knowledge regarding the biology of disease but are prone to false discovery and non generalizability due to population selection bias, epistatic factors and racial/ethnic stratification that influence the genetic background on which modifier genes act [19,138,139]. The increasingly popular genome-wide association study approach has the obvious advantage of being time-efficient, less biased and capable of novel gene discovery in the absence of a priori hypotheses about disease pathogenesis. The major challenge for genome-wide association studies continues to be the sheer volume of statistical tests of association that are performed, increasing the false-discovery rate, and the paucity of biological data to guide the interpretation of results. Follow-up studies in separate populations are therefore essential to replicate or refute positive associations found using either of these approaches, and both methods may be useful in elucidating mechanisms of disease. Observed genetic associations should also be interpreted with caution, because they may differ significantly between populations. For example, despite enrollment of African–American individuals in some of the studies discussed in this review, the observed associations may not hold among individuals enrolled in antiretroviral treatment programs in different African countries. The relative impact of malaria, other potentially neurotoxic drugs such as isoniazid, nutritional deficiencies, and genetic diversity among HIV-infected populations require careful consideration prior to any intervention to reduce the risk of NRTI-related complications.

Clearly, much work remains to be done in advancing the understanding of NRTI-related peripheral neuropathy. Key areas in which further research is needed include:

■ Clinical and translational studies to better elucidate relationships between mitochondrial function and inflammatory responses in HIV-infected individuals;

■ The impact of cytokines and inflammation on toxicity of specific NRTI drugs and drug combinations;

■ The role of specific nutrients, including iron.

Recently, in vitro and animal models have been developed in which the effects of antiretroviral drugs on peripheral nerve axons can be investigated in more detail [140-143]. The concomitant use of mitochondrial cybrids, mtDNA-depleted cells in which mtDNA with specific variants of interest can be introduced, may also prove useful for studying the functional effects of these variants [144]. Finally, cohort studies in HIV-infected individuals and studies of NRTI toxicity in the future need to incorporate standardized and validated methods of phenotyping peripheral neuropathy. Ascertainment of NRTI-associated neurotoxicity in prospective pharmacogenetic and pharmacogenomic studies may include some combination of standardized clinical criteria such as the total neuropathy score, which has proved to be reliable and well-correlated to objective findings [37,145]. The appropriate role of supplementary objective testing, such as epidermal nerve-fiber density measurements on skin biopsy specimens or quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing [28,53,146-149] in the assessment of peripheral neuropathy during HIV treatment remains to be clarified.

Executive summary.

Definition of nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI)-associated peripheral neuropathy

■ NRTI therapy in HIV-infected individuals is commonly associated with development of a symmetric, small-fiber sensory polyneuropathy that is characterized by painful dysesthesias and sensory loss.

■ This toxic neuropathy is currently indistinguishable from the distal sensory neuropathy that may occur in HIV infection even in the absence of NRTI therapy.

Pathophysiology of NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy

■ There is strong evidence that NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy is due at least in part to drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction.

■ Inflammatory damage to peripheral nerve axons and dorsal root ganglia by infiltrating activated macrophages also plays a role.

Candidate pathways & processes in which genetic variation may modulate the risk of neuropathy during NRTI therapy

■ Host genetic variation in antioxidant genes, apoptosis, mitochondrial function, cellular NRTI metabolism, inflammatory responses and nutrient metabolism may impact the risk of NRTI neurotoxicity.

Pharmacogenetics & NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy

■ Biologically plausible associations of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms with NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy in large case–control studies include: mtDNA haplogroup T and mtDNA 4917G (increased risk), HFE G845A and IL-12B (3′-UTR*2) (decreased risk), and TNF-α variants 1031*2 and 308*2 (increased risk).

■ Only the TNF-α 1031*2 variant has been studied and confirmed as a risk factor in more than one study population.

■ If these associations are consistently replicated in other HIV cohorts, screening for these polymorphisms may improve clinical strategies for predicting and preventing NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group Investigators and the many HIV-infected individuals whose participation was critical to the studies reviewed here.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The studies conducted by the authors at Vanderbilt were supported by the following NIH grants: a Vanderbilt CFAR Interdisciplinary Development Award and NIH 5R21HL087726-02 (to AK) and K23 AT002508-02 and R21 NS059330-02 (to TH). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the NIH. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript

Footnotes

■ Websites

201 Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. Accessed March 17 (2008) http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf

202 MITOMAP: A human mitochondrial genome database (2008) www.mitomap.org

203 Creative commons http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

- 1.The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative ana lysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2■.Arnaudo E, Dalakas M, Shanske S, Moraes CT, DiMauro S, Schon EA. Depletion of muscle mitochondrial DNA in AIDS patients with zidovudine-induced myopathy. Lancet. 1991;337(8740):508–510. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91294-5. [■ of interestAlong with [3], early clinical, histological and biochemical descriptions of zidovudine myopathy identifying mitochondria (and mitochondrial DNA [mtDNA]) as a locus of toxicity.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3■.Dalakas MC, Illa I, Pezeshkpour GH, Laukaitis JP, Cohen B, Griffin JL. Mitochondrial myopathy caused by long-term zidovudine therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;322(16):1098–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004193221602. [■ of interestAlong with [2], early clinical, histological and biochemical descriptions of zidovudine myopathy identifying mitochondria (and mitochondrial DNA) as a locus of toxicity.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan D, Mallal S. Complications associated with NRTI therapy: update on clinical features and possible pathogenic mechanisms. Antivir. Ther. 2004;9(6):849–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandya R, Krentz HB, Gill MJ, Power C. HIV-related neurological syndromes reduce health-related quality of life. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005;32(2):201–204. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100003978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yarchoan R, Pluda JM, Perno CF, et al. Initial clinical experience with dideoxynucleosides as single agents and in combination therapy. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1990;616:328–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb17853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherry CL, Skolasky RL, Lal L, et al. Antiretroviral use and other risks for HIV-associated neuropathies in an international cohort. Neurology. 2006;66(6):867–873. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203336.12114.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammer SM, Eron JJ, Jr, Reiss P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2008 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2008;300(5):555–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clumeck N, Pozniak A, Raffi F. European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) guidelines for the clinical management and treatment of HIV-infected adults. HIV Med. 2008;9(2):65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10■.Smyth K, Affandi JS, McArthur JC, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for HIV-associated neuropathy in Melbourne, Australia 1993−2006. HIV Med. 2007;8(6):367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00478.x. [■ of interestCross-sectional study of the prevalence of HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy among adults attending a tertiary referral clinic in 2006 (dideoxy-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors [dNRTI]-sparing highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART] era), compared with data from the same clinic in 1993 (pre-HAART) and 2001 (frequent use of dNRTIs).] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forma F, Liechty CA, Solberg P, et al. Clinical toxicity of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a home-based AIDS care program in rural Uganda. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2007;44(4):456–462. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318033ffa1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12■.Murphy RA, Sunpath H, Kuritzkes DR, Venter F, Gandhi RT. Antiretroviral therapy-associated toxicities in the resource-poor world: the challenge of a limited formulary. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S449–S456. doi: 10.1086/521112. [■ of interestReview of the challenges and practical considerations involved in treating HIV-infected individuals in developing countries with reference to complications associated with specific drug combinations and exogenous factors.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins C, Achenbach C, Fryda W, Ngare D, Murphy R. Antiretroviral durability and tolerability in HIV-infected adults living in urban Kenya. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2007;45(3):304–310. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d66c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renaud-Thery F, Nguimfack BD, Vitoria M, et al. Use of antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited countries in 2006: distribution and uptake of first- and second-line regimens. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 4):S89–S95. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000279711.54922.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurent C, Bourgeois A, Mpoudi-Ngolé E, et al. Tolerability and effectiveness of first-line regimens combining nevirapine and lamivudine plus zidovudine or stavudine in Cameroon. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2008;24(3):393–399. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makinson A, Moing VL, Kouanfack C, Laurent C, Delaporte E. Safety of stavudine in the treatment of HIV infection with a special focus on resource-limited settings. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2008;7(3):283–293. doi: 10.1517/14740338.7.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas DW. Will pharmacogenomic discoveries improve HIV therapeutics? Top. HIV Med. 2005;13(3):90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Novoa S, Barreiro P, Jimenez-Nacher I, Soriano V. Overview of the pharmacogenetics of HIV therapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6(4):234–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Summar ML, Hall L, Christman B, et al. Environmentally determined genetic expression: clinical correlates with molecular variants of carbamyl phosphate synthetase 1. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;81(Suppl 1):S12–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas DW, Wilkinson GR, Kuritzkes DR, et al. A multi-investigator/institutional DNA bank for AIDS-related human genetic studies: AACTG Protocol A5128. HIV Clin. Trials. 2003;4(5):287–300. doi: 10.1310/MUQC-QXBC-8118-BPM5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Telenti A. The genetic cohorts: facing the new challenges in infectious diseases. The HIV model. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2004;22(6):337–341. doi: 10.1016/s0213-005x(04)73106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips EJ, Mallal SA. Pharmacogenetics and the potential for the individualization of antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2008;21(1):16–24. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f42224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telenti A, Zanger UM. Pharmacogenetics of anti-HIV drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008;48:227–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tozzi V, Libertone R, Liuzzi G. HIV pharmacogenetics in clinical practice: recent achievements and future challenges. Curr. HIV Res. 2008;6(6):544–564. doi: 10.2174/157016208786501535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Duarte A, Robinson-Papp J, Simpson DM. Diagnosis and management of HIV-associated neuropathy. Neurol. Clin. 2008;26(3):821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherry CL, McArthur JC, Hoy JF, Wesselingh SL. Nucleoside analogues and neuropathy in the era of HAART. J. Clin. Virol. 2003;26(2):195–207. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson DM. Selected peripheral neuropathies associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection and antiretroviral therapy. J. Neurovirol. 2002;8(Suppl 2):33–41. doi: 10.1080/13550280290167939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peltier AC, Russell JW. Advances in understanding drug-induced neuropathies. Drug Saf. 2006;29:23–30. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pardo CA, McArthur JC, Griffin JW. HIV neuropathy: insights in the pathology of HIV peripheral nerve disease. J. Periph. Nerv. Syst. 2001;6(1):21–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2001.006001021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30■.Cherry CL, Rosenow A, Affandi JS, McArthur JC, Wesselingh SL, Price P. Cytokine genotype suggests a role for inflammation in nucleoside analog-associated sensory neuropathy (NRTI-SN) and predicts an individual's NRTI-SN risk. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2008;24(2):117–123. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0168. [■ of interestFirst study of known cytokine polymorphisms in association with nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI)-associated peripheral neuropathy. This study also suggests that patients who develop neuropathy after more than 6 months on dNRTI therapy are genetically similar to neuropathy-resistant patients.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31■.Keswani SC, Pardo CA, Cherry CL, Höke A, McArthur JC. HIV-associated sensory neuropathies. AIDS. 2002;16:2105–2117. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211080-00002. [■ of interestExcellent review of NRTI- and HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy, highlighting key pathological findings.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Sheklee A, Chelimsky TC, Preston DC. Review: small-fiber neuropathy. Neurologist. 2002;8:237–253. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouhassira D, Attal N, Willer J-C, Brasseur L. Painful and painless peripheral sensory neuropathies due to HIV infection: a comparison using quantitative sensory evaluation. Pain. 1999;80:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huengsberg M, Winer J, Ross J, Shahmanesh M. Thermosensory threshold: a sensitive test of HIV associated peripheral neuropathy? J. Neurovirol. 1998;4:433–437. doi: 10.3109/13550289809114542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tagliati M, Grinnell J, Godbold J, Simpson DM. Peripheral nerve function in HIV infection. Clinical, electrophysiologic, and laboratory findings. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:84–89. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polydefkis M, Yiannoutsos C, Cohen B, et al. Reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Neurology. 2002;58(1):115–119. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37■.Simpson DM, Kitch D, Evans SR, et al. HIV neuropathy natural history cohort study: assessment measures and risk factors. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1679–1687. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218303.48113.5d. [■ of interestDiscusses the challenges associated with ascertainment of HIV- and NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schifitto G, McDermott MP, McArthur JC, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2002;58(12):1764–1768. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arenas-Pinto A, Bhaskaran K, Dunn D, Weller IV. The risk of developing peripheral neuropathy induced by nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors decreases over time: evidence from the Delta trial. Antivir. Ther. 2008;13(2):289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sacktor N. The epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurological disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Neurovirol. 2002;8(Suppl 2):115–121. doi: 10.1080/13550280290101094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornblath DR, Höke A. Recent advances in HIV neuropathy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2006;19(5):446–450. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000245366.59446.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moyle G. Clinical manifestations and management of antiretroviral nucleoside analog-related mitochondrial toxicity. Clin. Ther. 2000;22(8):911–936. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80064-8. discussion 898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hahn K, Arendt G, Braun JS, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of gabapentin for painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathies. J. Neurol. 2004;251(10):1260–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson DM, McArthur JC, Olney R, et al. Lamotrigine for HIV-associated painful sensory neuropathies: a placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60(9):1508–1514. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063304.88470.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simpson DM, Olney R, McArthur JC, Khan A, Godbold J, Ebel-Frommer K. A placebo-controlled trial of lamotrigine for painful HIV-associated neuropathy. Neurology. 2000;54(11):2115–2119. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.11.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McArthur JC, Yiannoutsos C, Simpson DM, et al. A Phase II trial of nerve growth factor for sensory neuropathy associated with HIV infection. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Team 291. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1080–1088. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Youle M, Osio M. A double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre study of acetyl l-carnitine in the symptomatic treatment of antiretroviral toxic neuropathy in patients with HIV-1 infection. HIV Med. 2007;8(4):241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simpson DM, Brown S, Tobias J. Controlled trial of high-concentration capsaicin patch for treatment of painful HIV neuropathy. Neurology. 2008;70(24):2305–2313. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000314647.35825.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keswani SC, Chander B, Hasan C, Griffin JW, McArthur JC, Höke A. FK56 is neuroprotective in a model of antiretroviral toxic neuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 2003;53(1):57–64. doi: 10.1002/ana.10401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50■.Toth C, Martinez JA, Liu WQ, et al. Local erythropoietin signaling enhances regeneration in peripheral axons. Neuroscience. 2008;154:767–783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.052. [■ of interestIncludes a detailed discussion of potential interactions between apoptotic and NF-κB signaling pathways in the context of erythropoietin effects in the peripheral nervous system.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill A, Ruxrungtham K, Hanvanich M, et al. Systematic review of clinical trials evaluating low doses of stavudine as part of antiretroviral treatment. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007;8(5):679–688. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hulgan T, Haas DW. Toward a pharmacogenetic understanding of nucleotide and nucleoside analogue toxicity. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194(11):1471–1474. doi: 10.1086/508550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53■.Anderson PL, Kakuda TN, Lichtenstein KA. The cellular pharmacology of nucleosideand nucleotide-analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitors and its relationship to clinical toxicities. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38(5):743–753. doi: 10.1086/381678. [■ of interestComprehensive discussion of how the pharmacology of NRTIs may relate to potential mechanisms underlying clinical risk factors for NRTI-associated peripheral neuropathy.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ellis RJ, Marquie-Beck J, Delaney P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors and risk for peripheral neuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64(5):566–572. doi: 10.1002/ana.21484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dragovic G, Jevtovic D. Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor usage and the incidence of peripheral neuropathy in HIV/AIDS patients. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2003;14(5):281–284. doi: 10.1177/095632020301400507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Currier JS, Spino C, Grimes J, et al. Differences between women and men in adverse events and CD4+ responses to nucleoside analogue therapy for HIV infection. The AIDS Clinical Trials Group 175 Team. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2000;24:316–324. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Baron A, et al. Modification of the incidence of drug-associated symmetrical peripheral neuropathy by host and disease factors in the HIV outpatient study cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40(1):148–157. doi: 10.1086/426076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rutschmann OT, Vernazza PL, Bucher HC, et al. Long-term hydroxyurea in combination with didanosine and stavudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. AIDS. 2000;14(14):2145–2151. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009290-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59■.Kakuda TN. Pharmacology of nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Clin. Ther. 2000;22(6):685–708. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)90004-3. [■ of interestThorough and accessible review of NRTI pharmacology and metabolism; includes a helpful table of associations between clinical risk factors for toxicity and biomarkers of cellular activation and intracellular NRTI triphosphate levels.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60■.Rauch A, Nolan D, Martin A, McKinnon E, Almeida C, Mallal S. Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43(1):99–102. doi: 10.1086/504874. [■ of interestProspective study confirming a reduction in abacavir hypersensitivity reactions with pretreatment HLA screening in the Western Australian population.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hughes DA, Vilar FJ, Ward CC, Alfirevic A, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. Cost–effectiveness ana lysis of HLA B*5701 genotyping in preventing abacavir hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14(6):335–342. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62■.Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, et al. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(6):568–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706135. [■ of interestSummarizes data associating abacavir hypersensitivity reactions with HLA‑B*5701 and discusses results of a large, placebo-controlled, randomized study of pharmacogenetic screening to reduce the risk of this complication.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ingelman-Sundberg M. Pharmacogenomic biomarkers for prediction of severe adverse drug reactions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(6):637–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0708842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Furman PA, Fyfe JA, St Clair MH, et al. Phosphorylation of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine and selective interaction of the 5′-triphosphate with human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83(21):8333–8337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cepeda JA, Wilks D. Excess peripheral neuropathy in patients treated with hydroxyurea plus didanosine and stavudine for HIV infection. AIDS. 2000;14(3):332–333. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lisziewicz J, Foli A, Wainberg M, Lori F. Hydroxyurea in the treatment of HIV infection: clinical efficacy and safety concerns. Drug Saf. 2003;26(9):605–624. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moreno A, Quereda C, Moreno L, et al. High rate of didanosine-related mitochondrial toxicity in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients receiving ribavirin. Antivir. Ther. 2004;9(1):133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fleischer R, Boxwell D, Sherman KE. Nucleoside analogues and mitochondrial toxicity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38(8):E79–E80. doi: 10.1086/383151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dolce V, Fiermonte G, Runswick MJ, Palmieri F, Walker JE. The human mitochondrial deoxynucleotide carrier and its role in the toxicity of nucleoside antivirals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(5):2284–2288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031430998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lewis W, Kohler JJ, Hosseini SH, et al. Antiretroviral nucleosides, deoxynucleotide carrier and mitochondrial DNA: evidence supporting the DNA pol γ hypothesis. AIDS. 2006;20(5):675–684. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216367.23325.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang J, Samuels DC. The evidence that the DNC (SLC25A19) is not the mitochondrial deoxyribonucleotide carrier. Mitochondrion. 2008;8(2):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Myers SN, Goyal RK, Roy JD, Fairfull LD, Wilson JW, Ferrell RE. Functional single nucleotide polymorphism haplotypes in the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2006;16(5):315–320. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000189804.41962.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Owen RP, Lagpacan LL, Taylor TR, et al. Functional characterization and haplotype ana lysis of polymorphisms in the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter, ENT2. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006;34(1):12–15. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee H, Hanes J, Johnson KA. Toxicity of nucleoside analogues used to treat AIDS and the selectivity of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 2003;42(50):14711–14719. doi: 10.1021/bi035596s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lewis W, Copeland WC, Day BJ. Mitochondrial DNA depletion, oxidative stress, and mutation: mechanisms of dysfunction from nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Lab. Invest. 2001;81(6):777–790. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76■.Lewis W, Dalakas MC. Mitochondrial toxicity of antiviral drugs. Nat. Med. 1995;1(5):417–422. doi: 10.1038/nm0595-417. [■ of interestEarly integrated review outlining the mtDNA polymerase γ (POLG) gene hypothesis.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamanaka H, Gatanaga H, Kosalaraksa P, et al. Novel mutation of human DNA polymerase γ associated with mitochondrial toxicity induced by anti-HIV treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195(10):1419–1425. doi: 10.1086/513872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lewis W. Pharmacogenomics, toxicogenomics, and DNA polymerase γ. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195(10):1399–1401. doi: 10.1086/513879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moyle G. Mechanisms of HIV and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor injury to mitochondria. Antivir. Ther. 2005;10(Suppl 2):M47–M52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80■.Lewis W, Day BJ, Copeland WC. Mitochondrial toxicity of NRTI antiviral drugs: an integrated cellular perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2(10):812–822. doi: 10.1038/nrd1201. [■ of interestExcellent recent review that includes discussion of mtDNA POLG polymorphisms.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81■.Hoschele D. Cell culture models for the investigation of NRTI-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Relevance for the prediction of clinical toxicity. Toxicol. In vitro. 2006;20(5):535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.11.007. [■ of interestExhaustive review of in vitro models of NRTI toxicity; exceptionally thorough tables.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dagan T, Sable C, Bray J, Gerschenson M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and antiretroviral nucleoside analog toxicities: what is the evidence? Mitochondrion. 2002;1(5):397–412. doi: 10.1016/s1567-7249(02)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lewis W, Gonzalez B, Chomyn A, Papoian T. Zidovudine induces molecular, biochemical, and ultrastructural changes in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89(4):1354–1360. doi: 10.1172/JCI115722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lewis W, Haase CP, Raidel SM, et al. Combined antiretroviral therapy causes cardiomyopathy and elevates plasma lactate in transgenic AIDS mice. Lab. Invest. 2001;81(11):1527–1536. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brinkman K, ter Hofstede HJ, Burger DM, Smeitink JA, Koopmans PP. Adverse effects of reverse transcriptase inhibitors: mitochondrial toxicity as common pathway. AIDS. 1998;12(14):1735–1744. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carr A, Cooper DA. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1423–1430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Walker UA, Bickel M, Lutke Volksbeck SI, et al. Evidence of nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor – associated genetic and structural defects of mitochondria in adipose tissue of HIV-infected patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2002;29(2):117–121. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200202010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cote HC, Yip B, Asselin JJ, et al. Mitochondrial:nuclear DNA ratios in peripheral blood cells from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients who received selected HIV antiretroviral drug regimens. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(12):1972–1976. doi: 10.1086/375353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McComsey GA, Paulsen DM, Lonergan JT, et al. Improvements in lipoatrophy, mitochondrial DNA levels and fat apoptosis after replacing stavudine with abacavir or zidovudine. AIDS. 2005;19(1):15–23. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nolan D, Hammond E, Martin A, et al. Mitochondrial DNA depletion and morphologic changes in adipocytes associated with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy. AIDS. 2003;17(9):1329–1338. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200306130-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Walker UA, Bauerle J, Laguno M, et al. Depletion of mitochondrial DNA in liver under antiretroviral therapy with didanosine, stavudine, or zalcitabine. Hepatology. 2004;39(2):311–317. doi: 10.1002/hep.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pace CS, Martin AM, Hammond EL, Mamotte CD, Nolan DA, Mallal SA. Mitochondrial proliferation, DNA depletion and adipocyte differentiation in subcutaneous adipose tissue of HIV-positive HAART recipients. Antivir. Ther. 2003;8(4):323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Moore RD, Wong WM, Keruly JC, et al. Incidence of neuropathy in HIV-infected patients on monotherapy versus those on combination therapy with didanosine, stavudine and hydroxyurea. AIDS. 2000;14(3):273–278. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290(5806):457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Michelakis ED. Mitochondrial medicine. A new era in medicine opens new windows and brings new challenges. Circulation. 2008;117:2431–2434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.775163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wallace DC, Brown MD, Lott MT. Mitochondrial DNA variation in human evolution and disease. Gene. 1999;238(1):211–230. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reeve AK, Krishnan KJ, Turnbull DM. Age related mitochondrial degenerative disorders in humans. Biotechnol. J. 2008;3(6):750–756. doi: 10.1002/biot.200800066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98■.Sadun A. Acquired mitochondrial impairment as a cause of optic nerve disease. Tr. Am. Ophth. Soc. 1998;96:881–923. [■ of interestExtensive review of potential mechanisms by which mitochondrial dysfunction may lead to neuronal damage in optic nerve diseases, including Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy.] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carelli V, Ross-Cisneros FN, Sadun AA. Optic nerve degeneration and mitochondrial dysfunction: genetic and acquired optic neuropathies. Neurochem. Internat. 2002;40:573–584. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shaikh S, Ta C, Basham AA, Mansour S. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy associated with antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001;131(1):143–145. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00716-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mackey DA, Fingert JH, Luzhansky JZ, et al. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy triggered by antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus. Eye. 2003;17(3):312–317. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Warner JE, Ries KM. Optic neuropathy in a patient with AIDS. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2001;21(2):92–94. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hulgan T, Hughes M, Sun X, et al. Oxidant stress and peripheral neuropathy during antiretroviral therapy: an AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006;42(4):450–454. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000226792.16216.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kallianpur AR, Hulgan T, Canter JA, et al. Hemochromatosis (HFE) gene mutations and peripheral neuropathy during antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006;20(11):1503–1513. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000237366.56864.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Morgello S, Estanislao L, Simpson D, et al. HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61(4):546–551. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dalakas MC. Peripheral neuropathy and antiretroviral drugs. J. Periph. Nerv. Syst. 2001;6:14–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2001.006001014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hahn K, Robinson B, Anderson C, et al. Differential effects of HIV infected macrophages on dorsal root ganglia neurons and axons. Exp. Neurol. 2008;210(1):30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Keswani SC, Polley M, Pardo CA, Griffin JW, McArthur JC, Höke A. Schwann cell chemokine receptors mediate HIV-1 gp-120 toxicity to sensory neurons. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54(3):287–296. doi: 10.1002/ana.10645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Melli G, Keswani SC, Fischer A, Chen W, Höke A. Spatially distinct and functionally independent mechanisms of axonal degeneration in a model of HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 5):1330–1338. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen L, Yang P, Kijlstra A. Distribution, markers, and functions of retinal microglia. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2002;10(1):27–39. doi: 10.1076/ocii.10.1.27.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bhangoo SK, Ren D, Miller RJ, et al. CXCR4 chemokine receptor signaling mediates pain hypersensitivity in association with antiretroviral toxic neuropathy. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007;21(5):581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tagliati M, Grinnell J, Godbold J, Simpson DM. Peripheral nerve function in HIV infection: clinical, electrophysiologic, and laboratory findings. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56(1):84–89. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kieburtz KD, Giang DW, Schiffer RB, Vakil N. Abnormal vitamin B12 metabolism in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Association with neurological dysfunction. Arch. Neurol. 1991;48(3):312–314. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530150082023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lecomte T, Landi B, Beaune P, Laurent-Puig P, Loriot M-A. Glutathione S-transferase P1 polymorphism (Ile105Val) predicts cumulative neuropathy in patients receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2006;12(10):3050–3056. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Conforti L, Fang G, Wang MS, et al. NAD+ and axon degeneration revisited: Nmnat1 cannot substitute for WldS to delay Wallerian degeneration. Cell Death Differentiation. 2007;14:116–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shukla SJ, Duan S, Badner JA, Wu X, Dolan ME. Susceptibility loci involved in cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2008;18:253–262. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f5e605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kweekel DM, Gelderblom H, Guchelaar HJ. Pharmacology of oxaliplatin and the use of pharmacogenomics to individualize therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2005;31(2):90–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Peters U, Preisler-Adams S, Lanvers-Kaminsky C, Jurgens H, Lamprecht-Dinnesen A. Sequence variation of mitochondrial DNA and individual sensitivity to the ototoxic effect of cisplatin. Anticancer Res. 2003;23(2B):1249–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chen X, Goudsmit J, van der Kuyl AC. Lack of correlation between length variation in the DNA polymerase γ gene CAG repeat and lactic acidosis or neuropathy during antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2002;18(8):531–534. doi: 10.1089/088922202753747879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Robbins GK, De Gruttola V, Shafer RW, et al. Comparison of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349(24):2293–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shafer RW, Smeaton LM, Robbins GK, et al. Comparison of four-drug regimens and pairs of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349(24):2304–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hulgan T, Haas DW, Haines JL, et al. Mitochondrial haplogroups and peripheral neuropathy during antiretroviral therapy: an adult AIDS clinical trials group study. AIDS. 2005;19(13):1341–1349. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180786.02930.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Canter JA, Haas DW, Kallianpur AR, et al. The mitochondrial pharmacogenomics of haplogroup T: MTND2*LHON4917G and antiretroviral therapy-associated peripheral neuropathy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8(1):71–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hofmann S, Bezold R, Jaksch M, et al. Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome and Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) are associated with distinct mitochondrial DNA haplotypes. Genomics. 1997;39(1):8–18. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Torroni A, Petrozzi M, D'Urbano L, et al. Haplotype and phylogenetic analyses suggest that one European-specific mtDNA background plays a role in the expression of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy by increasing the penetrance of the primary mutations 11778 and 14484. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;60(5):1107–1121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hofmann S, Bezold R, Jaksch M, Kaufhold P, Obermaier-Kusser B, Gerbitz KD. Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA from patients with Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1997;174(1−2):209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Simdon J, Watters D, Bartlett S, Connick E. Ototoxicity associated with use of nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors: a report of 3 possible cases and review of the literatures. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;32:1623–1627. doi: 10.1086/320522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schouten JT, Lockhart DW, Rees TS, Collier AC, Marra CM. A prospective study of hearing changes after beginning zidovudine or didanosine in HIV-1 treament-naive people. BMC Infect. Dis. 2006;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pietrangelo A. Hereditary hemochromatosis – a new look at an old disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350(23):2383–2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]